Submitted:

05 May 2025

Posted:

06 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Retrograde menstruation

- Lymphatic and Hematogenous Spread

- Stem cell theory

- Coelomic metaplasia

- Embryonic rest theory

- Iatrogenic dissemination

- Genetic and epigenetic factors

2. Psychological Aspects of Pain Management in Endometriosis

3. Diagnosis and Biomarkers

3.1. Protein Markers of Endometriosis

3.2. Other Markers

4. Treatment of Endometriosis

4.1. Classical Treatment Methods

4.2. Surgery

4.3. Sclerotherapy of Endometrial Cysts and Other Methods

4.4. Natural Substances Used in the Treatment

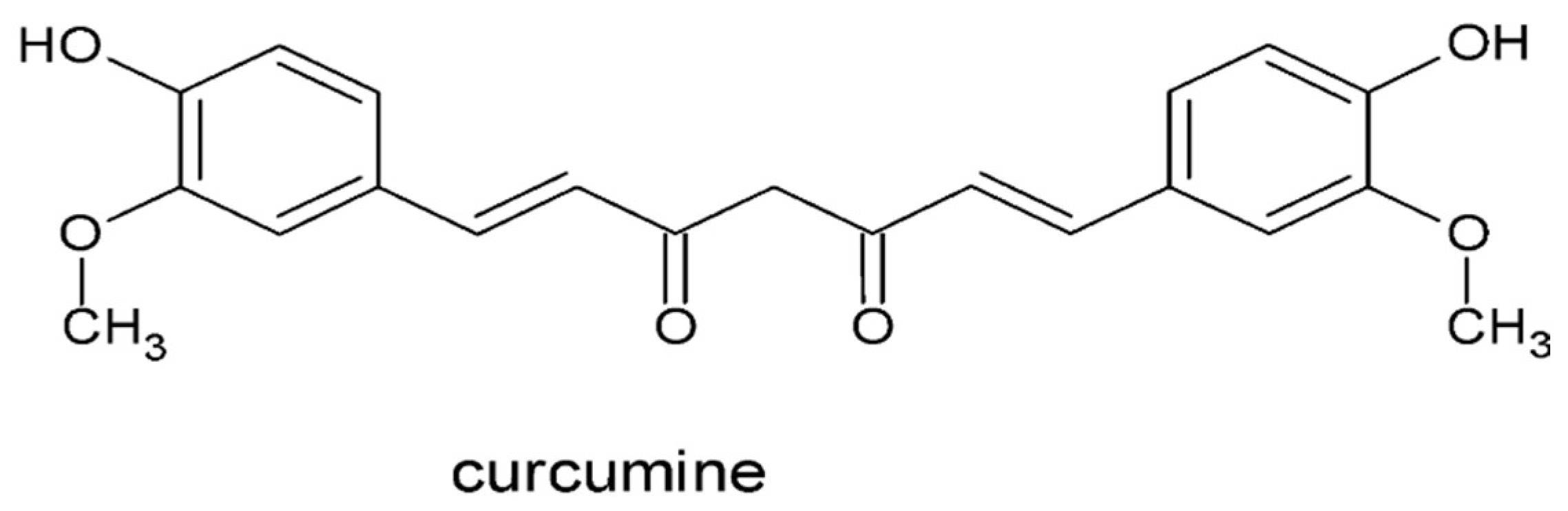

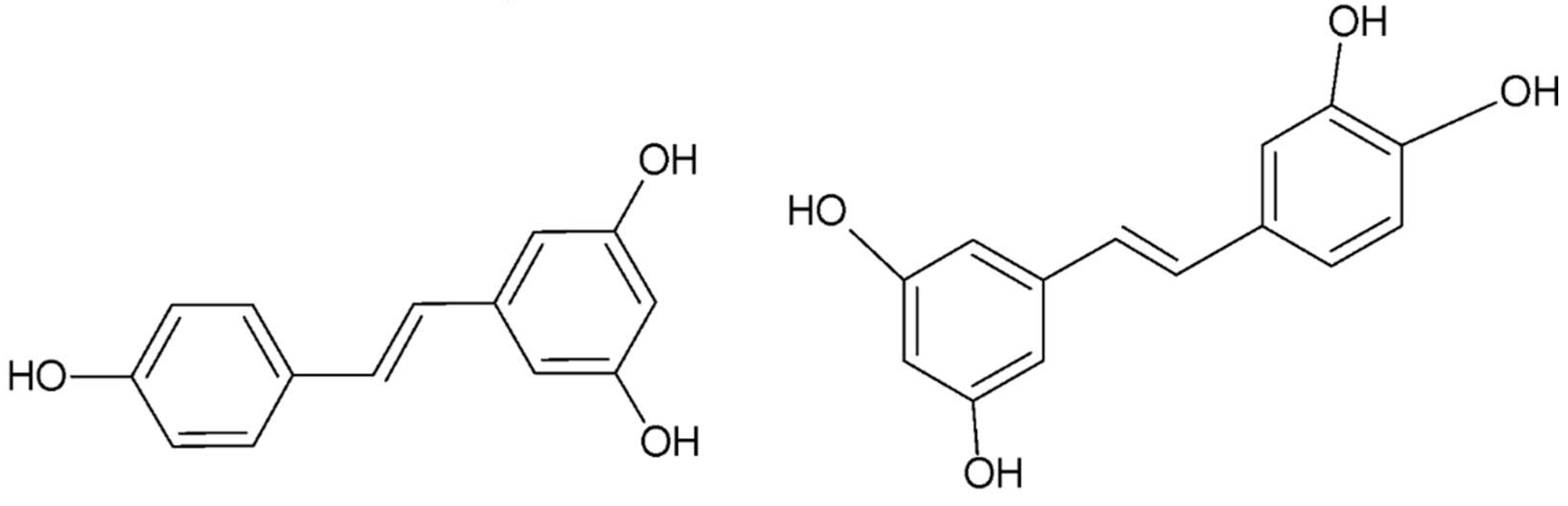

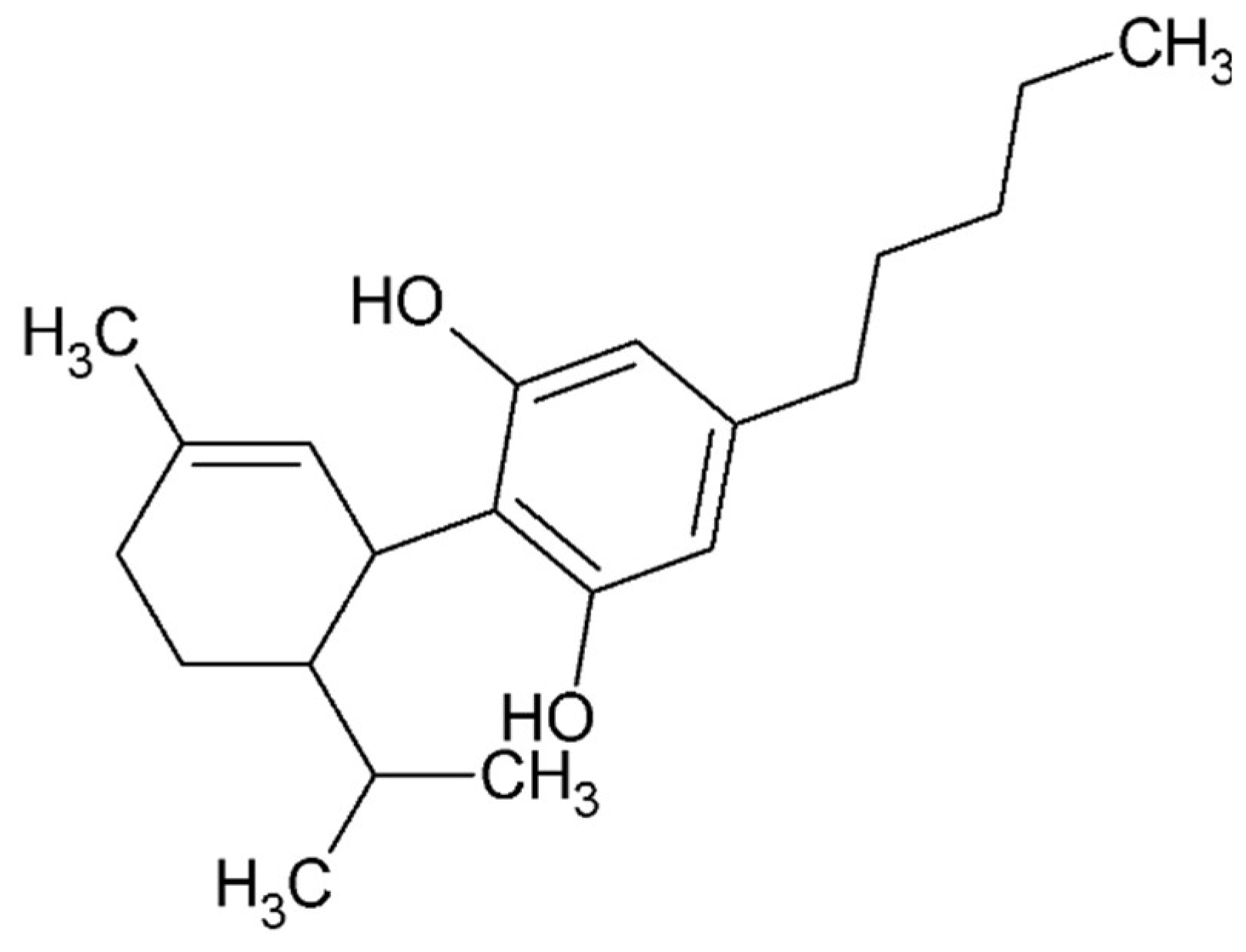

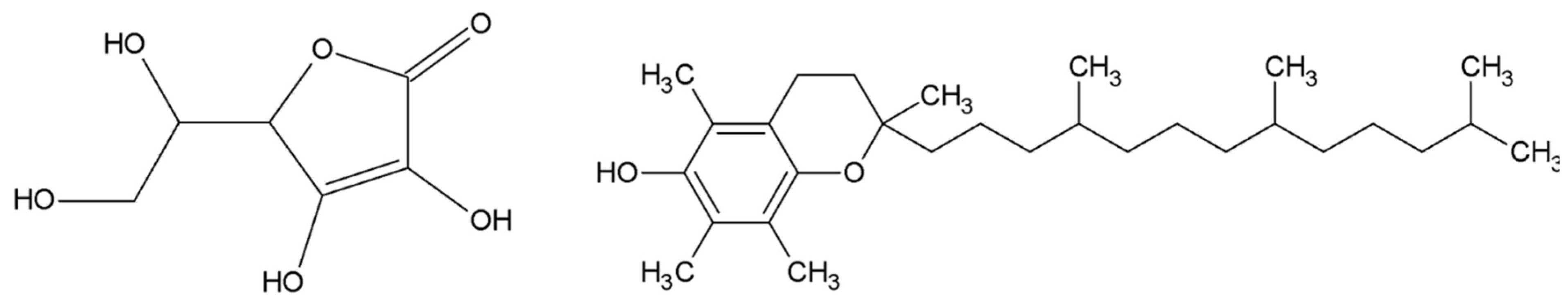

- Resveratrol

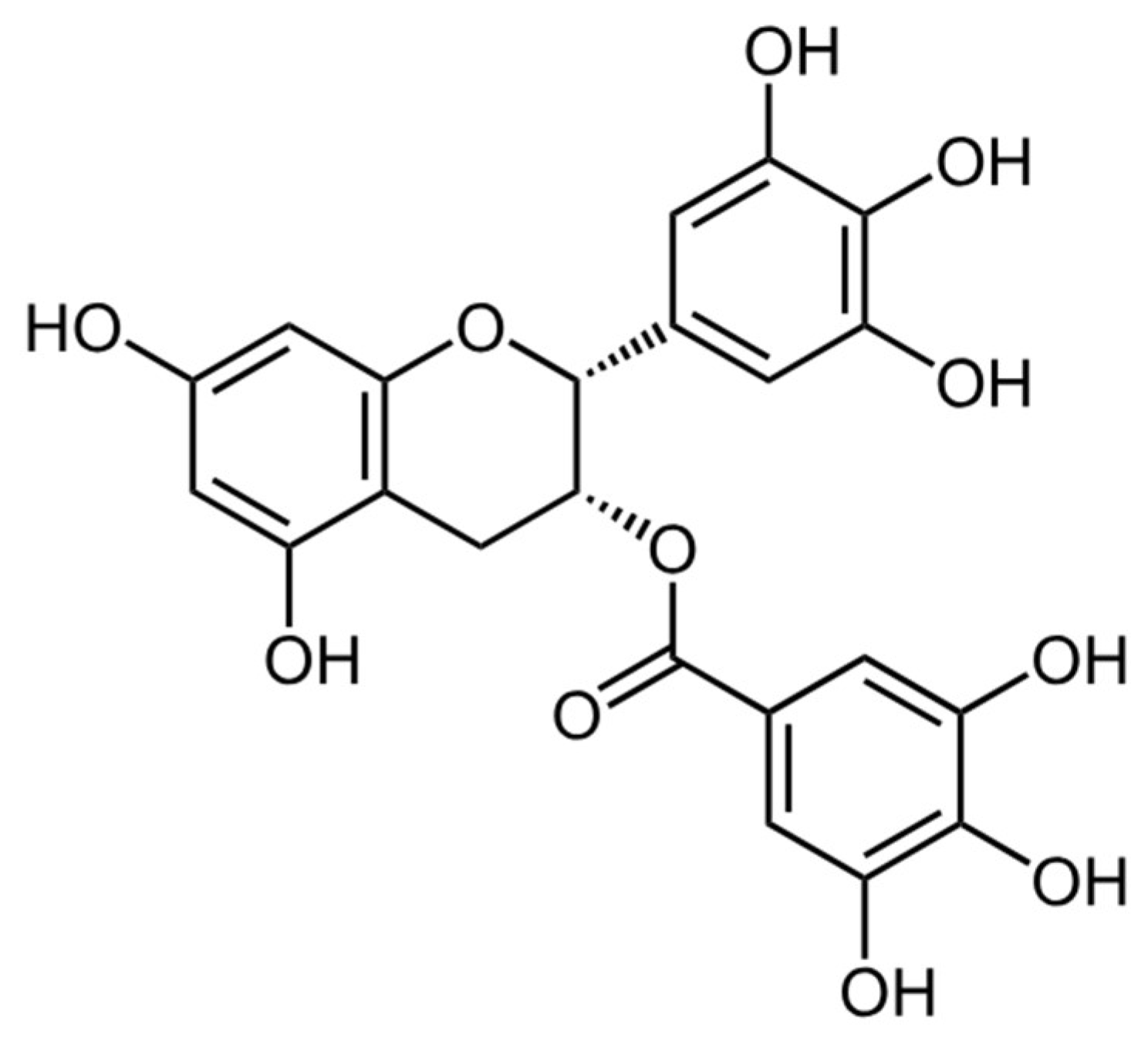

- Epigallocatechin gallate

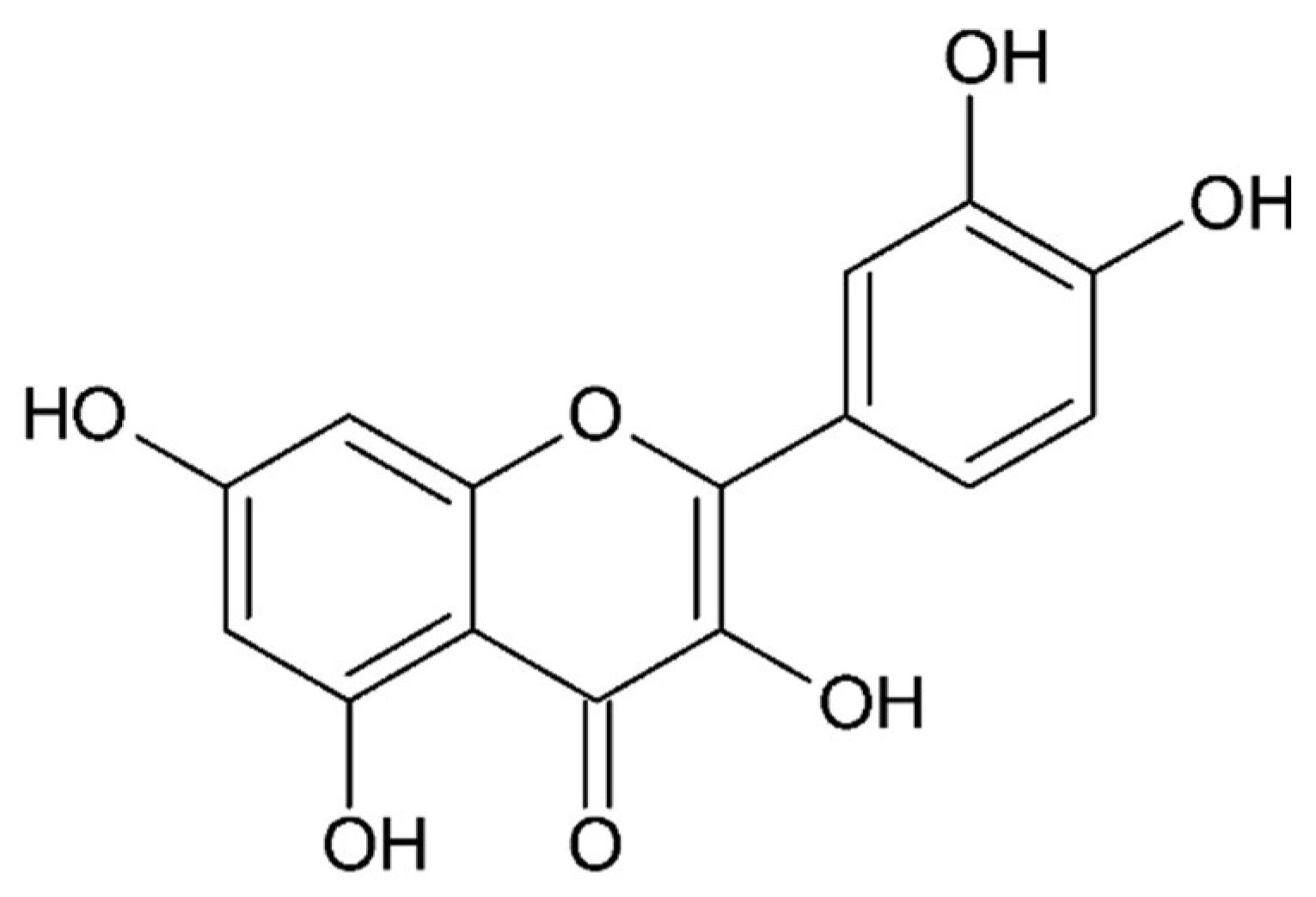

- Quercetin

4.5. Small Compounds Used in the Treatment

4.6. Stem Cell Therapy

4.7. Gene Therapy

5. Impact on Quality of Life

References

- Vlahos, N. F.; Economopoulos, K. P.; Fotiou, S., Endometriosis, in vitro fertilisation and the risk of gynaecological malignancies, including ovarian and breast cancer. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2010, 24, (1), 39-50. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, H.; Sumimoto, K.; Kitanaka, T.; Yamada, Y.; Sado, T.; Sakata, M.; Yoshida, S.; Kawaguchi, R.; Kanayama, S.; Shigetomi, H.; Haruta, S.; Tsuji, Y.; Ueda, S.; Terao, T., Ovarian endometrioma--risks factors of ovarian cancer development. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2008, 138, (2), 187-93. [CrossRef]

- Melin, A.; Sparén, P.; Persson, I.; Bergqvist, A., Endometriosis and the risk of cancer with special emphasis on ovarian cancer. Hum Reprod 2006, 21, (5), 1237-42. [CrossRef]

- Vercellini, P.; Scarfone, G.; Bolis, G.; Stellato, G.; Carinelli, S.; Crosignani, P. G., Site of origin of epithelial ovarian cancer: the endometriosis connection. BJOG 2000, 107, (9), 1155-7. [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, S.; Kaku, T.; Amada, S.; Kobayashi, H.; Hirakawa, T.; Ariyoshi, K.; Kamura, T.; Nakano, H., Ovarian endometriosis associated with ovarian carcinoma: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study. Gynecol Oncol 2000, 77, (2), 298-304. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Munkarah, A.; Arabi, H.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Semaan, A.; Hayek, K.; Garg, G.; Morris, R.; Ali-Fehmi, R., Prognostic analysis of ovarian cancer associated with endometriosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011, 204, (1), 63.e1-7. [CrossRef]

- Giudice, L. C., Clinical practice. Endometriosis. N Engl J Med 2010, 362, (25), 2389-98.

- Bulun, S. E., Endometriosis. N Engl J Med 2009, 360, (3), 268-79.

- Jabbour, H. N.; Kelly, R. W.; Fraser, H. M.; Critchley, H. O., Endocrine regulation of menstruation. Endocr Rev 2006, 27, (1), 17-46. [CrossRef]

- Critchley, H. O. D.; Maybin, J. A.; Armstrong, G. M.; Williams, A. R. W., Physiology of the Endometrium and Regulation of Menstruation. Physiol Rev 2020, 100, (3), 1149-1179. [CrossRef]

- Sampson, J. A., Metastatic or Embolic Endometriosis, due to the Menstrual Dissemination of Endometrial Tissue into the Venous Circulation. Am J Pathol 1927, 3, (2), 93-110.43.

- Jubanyik, K. J.; Comite, F., Extrapelvic endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 1997, 24, (2), 411-40.

- Maruyama, T.; Yoshimura, Y., Stem cell theory for the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2012, 4, (8), 2754-63. [CrossRef]

- Gargett, C. E., Uterine stem cells: what is the evidence? Hum Reprod Update 2007, 13, (1), 87-101.

- Maruyama, T.; Masuda, H.; Ono, M.; Kajitani, T.; Yoshimura, Y., Human uterine stem/progenitor cells: their possible role in uterine physiology and pathology. Reproduction 2010, 140, (1), 11-22. [CrossRef]

- Sasson, I. E.; Taylor, H. S., Stem cells and the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2008, 1127, 106-15. [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Taylor, H. S., Contribution of bone marrow-derived stem cells to endometrium and endometriosis. Stem Cells 2007, 25, (8), 2082-6. [CrossRef]

- Hufnagel, D.; Li, F.; Cosar, E.; Krikun, G.; Taylor, H. S., The Role of Stem Cells in the Etiology and Pathophysiology of Endometriosis. Semin Reprod Med 2015, 33, (5), 333-40.

- Duke, C. M.; Taylor, H. S., Stem cells and the reproductive system: historical perspective and future directions. Maturitas 2013, 76, (3), 284-9. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, M.; Katabuchi, H.; Tohya, T.; Fukumatsu, Y.; Matsuura, K.; Okamura, H., Scanning electron microscopic and immunohistochemical studies of pelvic endometriosis. Hum Reprod 1993, 8, (12), 2218-26. [CrossRef]

- Matsuura, K.; Ohtake, H.; Katabuchi, H.; Okamura, H., Coelomic metaplasia theory of endometriosis: evidence from in vivo studies and an in vitro experimental model. Gynecol Obstet Invest 1999, 47 Suppl 1, 18-20; discussion 20-2. [CrossRef]

- Lamceva, J.; Uljanovs, R.; Strumfa, I., The Main Theories on the Pathogenesis of Endometriosis. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, (5). [CrossRef]

- Signorile, P. G.; Viceconte, R.; Baldi, A., New Insights in Pathogenesis of Endometriosis. Front Med (Lausanne) 2022, 9, 879015. [CrossRef]

- Stefanko, D. P.; Eskander, R.; Aisagbonhi, O., Disseminated Endometriosis and Low-Grade Endometrioid Stromal Sarcoma in a Patient with a History of Uterine Morcellation for Adenomyosis. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol 2020, 2020, 7201930. [CrossRef]

- Sepilian, V.; Della Badia, C., Iatrogenic endometriosis caused by uterine morcellation during a supracervical hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol 2003, 102, (5 Pt 2), 1125-7.

- Cubuk, A.; Ozkaptan, O.; Neymeyer, J., Iatrogenic endometriosis following apical pelvic organ prolapse surgery: a case report. J Med Case Rep 2020, 14, (1), 3. [CrossRef]

- Rahmioglu, N.; Mortlock, S.; Ghiasi, M.; Møller, P. L.; Stefansdottir, L.; Galarneau, G.; Turman, C.; Danning, R.; Law, M. H.; Sapkota, Y.; Christofidou, P.; Skarp, S.; Giri, A.; Banasik, K.; Krassowski, M.; Lepamets, M.; Marciniak, B.; Nõukas, M.; Perro, D.; Sliz, E.; Sobalska-Kwapis, M.; Thorleifsson, G.; Topbas-Selcuki, N. F.; Vitonis, A.; Westergaard, D.; Arnadottir, R.; Burgdorf, K. S.; Campbell, A.; Cheuk, C. S. K.; Clementi, C.; Cook, J.; De Vivo, I.; DiVasta, A.; Dorien, O.; Donoghue, J. F.; Edwards, T.; Fontanillas, P.; Fung, J. N.; Geirsson, R. T.; Girling, J. E.; Harkki, P.; Harris, H. R.; Healey, M.; Heikinheimo, O.; Holdsworth-Carson, S.; Hostettler, I. C.; Houlden, H.; Houshdaran, S.; Irwin, J. C.; Jarvelin, M. R.; Kamatani, Y.; Kennedy, S. H.; Kepka, E.; Kettunen, J.; Kubo, M.; Kulig, B.; Kurra, V.; Laivuori, H.; Laufer, M. R.; Lindgren, C. M.; MacGregor, S.; Mangino, M.; Martin, N. G.; Matalliotaki, C.; Matalliotakis, M.; Murray, A. D.; Ndungu, A.; Nezhat, C.; Olsen, C. M.; Opoku-Anane, J.; Padmanabhan, S.; Paranjpe, M.; Peters, M.; Polak, G.; Porteous, D. J.; Rabban, J.; Rexrode, K. M.; Romanowicz, H.; Saare, M.; Saavalainen, L.; Schork, A. J.; Sen, S.; Shafrir, A. L.; Siewierska-Górska, A.; Słomka, M.; Smith, B. H.; Smolarz, B.; Szaflik, T.; Szyłło, K.; Takahashi, A.; Terry, K. L.; Tomassetti, C.; Treloar, S. A.; Vanhie, A.; Vincent, K.; Vo, K. C.; Werring, D. J.; Zeggini, E.; Zervou, M. I.; Adachi, S.; Buring, J. E.; Ridker, P. M.; D'Hooghe, T.; Goulielmos, G. N.; Hapangama, D. K.; Hayward, C.; Horne, A. W.; Low, S. K.; Martikainen, H.; Chasman, D. I.; Rogers, P. A. W.; Saunders, P. T.; Sirota, M.; Spector, T.; Strapagiel, D.; Tung, J. Y.; Whiteman, D. C.; Giudice, L. C.; Velez-Edwards, D. R.; Uimari, O.; Kraft, P.; Salumets, A.; Nyholt, D. R.; Mägi, R.; Stefansson, K.; Becker, C. M.; Yurttas-Beim, P.; Steinthorsdottir, V.; Nyegaard, M.; Missmer, S. A.; Montgomery, G. W.; Morris, A. P.; Zondervan, K. T.; Consortium, D. G.; Study, F.; Taskforce, F. E.; Team, C. R.; Team, a. R., The genetic basis of endometriosis and comorbidity with other pain and inflammatory conditions. Nat Genet 2023, 55, (3), 423-436. [CrossRef]

- Bedrick, B. S.; Courtright, L.; Zhang, J.; Snow, M.; Amendola, I. L. S.; Nylander, E.; Cayton-Vaught, K.; Segars, J.; Singh, B., A Systematic Review of Epigenetics of Endometriosis. F S Rev 2024, 5, (1). [CrossRef]

- Pagliardini, L.; Gentilini, D.; Sanchez, A. M.; Candiani, M.; Viganò, P.; Di Blasio, A. M., Replication and meta-analysis of previous genome-wide association studies confirm vezatin as the locus with the strongest evidence for association with endometriosis. Hum Reprod 2015, 30, (4), 987-93. [CrossRef]

- Edwards, M. J., Functional neurological disorder: lighting the way to a new paradigm for medicine. Brain 2021, 144, (11), 3279-3282. [CrossRef]

- Laganà, A. S.; Condemi, I.; Retto, G.; Muscatello, M. R.; Bruno, A.; Zoccali, R. A.; Triolo, O.; Cedro, C., Analysis of psychopathological comorbidity behind the common symptoms and signs of endometriosis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2015, 194, 30-3. [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K., Patients presenting with somatic complaints: epidemiology, psychiatric comorbidity and management. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2003, 12, (1), 34-43. [CrossRef]

- Delanerolle, G.; Ramakrishnan, R.; Hapangama, D.; Zeng, Y.; Shetty, A.; Elneil, S.; Chong, S.; Hirsch, M.; Oyewole, M.; Phiri, P.; Elliot, K.; Kothari, T.; Rogers, B.; Sandle, N.; Haque, N.; Pluchino, N.; Silem, M.; O'Hara, R.; Hull, M. L.; Majumder, K.; Shi, J. Q.; Raymont, V., A systematic review and meta-analysis of the Endometriosis and Mental-Health Sequelae; The ELEMI Project. Womens Health (Lond) 2021, 17, 17455065211019717. [CrossRef]

- Laganà, A. S.; La Rosa, V. L.; Rapisarda, A. M. C.; Valenti, G.; Sapia, F.; Chiofalo, B.; Rossetti, D.; Ban Frangež, H.; Vrtačnik Bokal, E.; Vitale, S. G., Anxiety and depression in patients with endometriosis: impact and management challenges. Int J Womens Health 2017, 9, 323-330. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S. K.; Foster, W. G.; Groessl, E. J., Rethinking endometriosis care: applying the chronic care model via a multidisciplinary program for the care of women with endometriosis. Int J Womens Health 2019, 11, 405-410. [CrossRef]

- Mundo-López, A.; Ocón-Hernández, O.; Lozano-Lozano, M.; San-Sebastián, A.; Fernández-Lao, C.; Galiano-Castillo, N.; Cantarero-Villanueva, I.; Arroyo-Morales, M.; Artacho-Cordón, F., Impact of symptom burden on work performance status in Spanish women diagnosed with endometriosis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2021, 261, 92-97. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, H. S.; Kotlyar, A. M.; Flores, V. A., Endometriosis is a chronic systemic disease: clinical challenges and novel innovations. Lancet 2021, 397, (10276), 839-852. [CrossRef]

- McPeak, A. E.; Allaire, C.; Williams, C.; Albert, A.; Lisonkova, S.; Yong, P. J., Pain Catastrophizing and Pain Health-Related Quality-of-Life in Endometriosis. Clin J Pain 2018, 34, (4), 349-356. [CrossRef]

- Maulenkul, T.; Kuandyk, A.; Makhadiyeva, D.; Dautova, A.; Terzic, M.; Oshibayeva, A.; Moldaliyev, I.; Ayazbekov, A.; Maimakov, T.; Saruarov, Y.; Foster, F.; Sarria-Santamera, A., Understanding the impact of endometriosis on women's life: an integrative review of systematic reviews. BMC Womens Health 2024, 24, (1), 524. [CrossRef]

- Della Corte, L.; Di Filippo, C.; Gabrielli, O.; Reppuccia, S.; La Rosa, V. L.; Ragusa, R.; Fichera, M.; Commodari, E.; Bifulco, G.; Giampaolino, P., The Burden of Endometriosis on Women's Lifespan: A Narrative Overview on Quality of Life and Psychosocial Wellbeing. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17, (13). [CrossRef]

- Pontoppidan, K.; Olovsson, M.; Grundström, H., Clinical factors associated with quality of life among women with endometriosis: a cross-sectional study. BMC Womens Health 2023, 23, (1), 551. [CrossRef]

- Gete, D. G.; Doust, J.; Mortlock, S.; Montgomery, G.; Mishra, G. D., Impact of endometriosis on women's health-related quality of life: A national prospective cohort study. Maturitas 2023, 174, 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Warzecha, D.; Szymusik, I.; Wielgos, M.; Pietrzak, B., The Impact of Endometriosis on the Quality of Life and the Incidence of Depression-A Cohort Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17, (10). [CrossRef]

- Leuenberger, J.; Kohl Schwartz, A. S.; Geraedts, K.; Haeberlin, F.; Eberhard, M.; von Orellie, S.; Imesch, P.; Leeners, B., Living with endometriosis: Comorbid pain disorders, characteristics of pain and relevance for daily life. Eur J Pain 2022, 26, (5), 1021-1038. [CrossRef]

- Linton, S. J.; Shaw, W. S., Impact of psychological factors in the experience of pain. Phys Ther 2011, 91, (5), 700-11. [CrossRef]

- Gerdle, B.; Åkerblom, S.; Brodda Jansen, G.; Enthoven, P.; Ernberg, M.; Dong, H. J.; Stålnacke, B. M.; Äng, B. O.; Boersma, K., Who benefits from multimodal rehabilitation - an exploration of pain, psychological distress, and life impacts in over 35,000 chronic pain patients identified in the Swedish Quality Registry for Pain Rehabilitation. J Pain Res 2019, 12, 891-908. [CrossRef]

- Evans, S.; Fernandez, S.; Olive, L.; Payne, L. A.; Mikocka-Walus, A., Psychological and mind-body interventions for endometriosis: A systematic review. J Psychosom Res 2019, 124, 109756. [CrossRef]

- Buggio, L.; Barbara, G.; Facchin, F.; Frattaruolo, M. P.; Aimi, G.; Berlanda, N., Self-management and psychological-sexological interventions in patients with endometriosis: strategies, outcomes, and integration into clinical care. Int J Womens Health 2017, 9, 281-293. [CrossRef]

- van Aken, M. A. W.; Oosterman, J. M.; van Rijn, C. M.; Ferdek, M. A.; Ruigt, G. S. F.; Peeters, B. W. M. M.; Braat, D. D. M.; Nap, A. W., Pain cognition versus pain intensity in patients with endometriosis: toward personalized treatment. Fertil Steril 2017, 108, (4), 679-686. [CrossRef]

- Dancet, E. A.; Apers, S.; Kremer, J. A.; Nelen, W. L.; Sermeus, W.; D'Hooghe, T. M., The patient-centeredness of endometriosis care and targets for improvement: a systematic review. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2014, 78, (2), 69-80. [CrossRef]

- Grundström, H.; Kilander, H.; Wikman, P.; Olovsson, M., Demographic and clinical characteristics determining patient-centeredness in endometriosis care. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2023, 307, (4), 1047-1055. [CrossRef]

- Boersen, Z.; de Kok, L.; van der Zanden, M.; Braat, D.; Oosterman, J.; Nap, A., Patients' perspective on cognitive behavioural therapy after surgical treatment of endometriosis: a qualitative study. Reprod Biomed Online 2021, 42, (4), 819-825. [CrossRef]

- Aerts, L.; Grangier, L.; Streuli, I.; Dällenbach, P.; Marci, R.; Wenger, J. M.; Pluchino, N., Psychosocial impact of endometriosis: From co-morbidity to intervention. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2018, 50, 2-10. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, S.; Bergqvist, A.; Chapron, C.; D'Hooghe, T.; Dunselman, G.; Greb, R.; Hummelshoj, L.; Prentice, A.; Saridogan, E.; Group, E. S. I. G. f. E. a. E. G. D., ESHRE guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis. Hum Reprod 2005, 20, (10), 2698-704. [CrossRef]

- Soliman, A. M.; Coyne, K. S.; Zaiser, E.; Castelli-Haley, J.; Fuldeore, M. J., The burden of endometriosis symptoms on health-related quality of life in women in the United States: a cross-sectional study. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 2017, 38, (4), 238-248. [CrossRef]

- Vannuccini, S.; Clemenza, S.; Rossi, M.; Petraglia, F., Hormonal treatments for endometriosis: The endocrine background. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2022, 23, (3), 333-355. [CrossRef]

- Exacoustos, C.; Malzoni, M.; Di Giovanni, A.; Lazzeri, L.; Tosti, C.; Petraglia, F.; Zupi, E., Ultrasound mapping system for the surgical management of deep infiltrating endometriosis. Fertil Steril 2014, 102, (1), 143-150.e2. [CrossRef]

- Nisolle, M.; Donnez, J., Peritoneal endometriosis, ovarian endometriosis, and adenomyotic nodules of the rectovaginal septum are three different entities. Fertil Steril 1997, 68, (4), 585-96.

- O'Brien, T. J.; Beard, J. B.; Underwood, L. J.; Shigemasa, K., The CA 125 gene: a newly discovered extension of the glycosylated N-terminal domain doubles the size of this extracellular superstructure. Tumour Biol 2002, 23, (3), 154-69.

- Yin, B. W.; Lloyd, K. O., Molecular cloning of the CA125 ovarian cancer antigen: identification as a new mucin, MUC16. J Biol Chem 2001, 276, (29), 27371-5.

- Barbieri, R. L.; Niloff, J. M.; Bast, R. C.; Scaetzl, E.; Kistner, R. W.; Knapp, R. C., Elevated serum concentrations of CA-125 in patients with advanced endometriosis. Fertil Steril 1986, 45, (5), 630-4. [CrossRef]

- Anfosso, F.; Bardin, N.; Vivier, E.; Sabatier, F.; Sampol, J.; Dignat-George, F., Outside-in signaling pathway linked to CD146 engagement in human endothelial cells. J Biol Chem 2001, 276, (2), 1564-9. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J. P.; Rothbächer, U.; Sers, C., The progression associated antigen MUC18: a unique member of the immunoglobulin supergene family. Melanoma Res 1993, 3, (5), 337-40.

- Leñero, C.; Kaplan, L. D.; Best, T. M.; Kouroupis, D., CD146+ Endometrial-Derived Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cell Subpopulation Possesses Exosomal Secretomes with Strong Immunomodulatory miRNA Attributes. Cells 2022, 11, (24). [CrossRef]

- Hilage, P.; Birajdar, A.; Marsale, T.; Patil, D.; Patil, A. M.; Telang, G.; Somasundaram, I.; Sharma, R. K.; Joshi, M. G., Characterization and angiogenic potential of CD146. Stem Cell Res Ther 2024, 15, (1), 330. [CrossRef]

- Chiu, P. C.; Koistinen, R.; Koistinen, H.; Seppala, M.; Lee, K. F.; Yeung, W. S., Zona-binding inhibitory factor-1 from human follicular fluid is an isoform of glycodelin. Biol Reprod 2003, 69, (1), 365-72. [CrossRef]

- Loukovaara, S.; Immonen, I. R.; Loukovaara, M. J.; Koistinen, R.; Kaaja, R. J., Glycodelin: a novel serum anti-inflammatory marker in type 1 diabetic retinopathy during pregnancy. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 2007, 85, (1), 46-9. [CrossRef]

- Oehninger, S.; Coddington, C. C.; Hodgen, G. D.; Seppala, M., Factors affecting fertilization: endometrial placental protein 14 reduces the capacity of human spermatozoa to bind to the human zona pellucida. Fertil Steril 1995, 63, (2), 377-83. [CrossRef]

- Rachmilewitz, J.; Riely, G. J.; Tykocinski, M. L., Placental protein 14 functions as a direct T-cell inhibitor. Cell Immunol 1999, 191, (1), 26-33. [CrossRef]

- Chiu, P. C.; Chung, M. K.; Koistinen, R.; Koistinen, H.; Seppala, M.; Ho, P. C.; Ng, E. H.; Lee, K. F.; Yeung, W. S., Cumulus oophorus-associated glycodelin-C displaces sperm-bound glycodelin-A and -F and stimulates spermatozoa-zona pellucida binding. J Biol Chem 2007, 282, (8), 5378-88. [CrossRef]

- Chiu, P. C.; Chung, M. K.; Tsang, H. Y.; Koistinen, R.; Koistinen, H.; Seppala, M.; Lee, K. F.; Yeung, W. S., Glycodelin-S in human seminal plasma reduces cholesterol efflux and inhibits capacitation of spermatozoa. J Biol Chem 2005, 280, (27), 25580-9. [CrossRef]

- Moore, R. G.; McMeekin, D. S.; Brown, A. K.; DiSilvestro, P.; Miller, M. C.; Allard, W. J.; Gajewski, W.; Kurman, R.; Bast, R. C.; Skates, S. J., A novel multiple marker bioassay utilizing HE4 and CA125 for the prediction of ovarian cancer in patients with a pelvic mass. Gynecol Oncol 2009, 112, (1), 40-6. [CrossRef]

- Drapkin, R.; von Horsten, H. H.; Lin, Y.; Mok, S. C.; Crum, C. P.; Welch, W. R.; Hecht, J. L., Human epididymis protein 4 (HE4) is a secreted glycoprotein that is overexpressed by serous and endometrioid ovarian carcinomas. Cancer Res 2005, 65, (6), 2162-9.

- Kang, S.; Tanaka, T.; Narazaki, M.; Kishimoto, T., Targeting Interleukin-6 Signaling in Clinic. Immunity 2019, 50, (4), 1007-1023. [CrossRef]

- Bedaiwy, M. A.; Falcone, T.; Goldberg, J. M.; Sharma, R. K.; Nelson, D. R.; Agarwal, A., Peritoneal fluid leptin is associated with chronic pelvic pain but not infertility in endometriosis patients. Hum Reprod 2006, 21, (3), 788-91. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Huang, X.; Guo, F.; Lei, T.; Li, S.; Monaghan-Nichols, P.; Jiang, Z.; Xin, H. B.; Fu, M., TRIM65 E3 ligase targets VCAM-1 degradation to limit LPS-induced lung inflammation. J Mol Cell Biol 2020, 12, (3), 190-201. [CrossRef]

- Taooka, Y.; Chen, J.; Yednock, T.; Sheppard, D., The integrin alpha9beta1 mediates adhesion to activated endothelial cells and transendothelial neutrophil migration through interaction with vascular cell adhesion molecule-1. J Cell Biol 1999, 145, (2), 413-20. [CrossRef]

- Marchese, M. E.; Berdnikovs, S.; Cook-Mills, J. M., Distinct sites within the vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) cytoplasmic domain regulate VCAM-1 activation of calcium fluxes versus Rac1 during leukocyte transendothelial migration. Biochemistry 2012, 51, (41), 8235-46. [CrossRef]

- Chu, X.; Qin, X.; Xu, H.; Li, L.; Wang, Z.; Li, F.; Xie, X.; Zhou, H.; Shen, Y.; Long, J., Structural insights into Paf1 complex assembly and histone binding. Nucleic Acids Res 2013, 41, (22), 10619-29. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Yi, D.; Lai, C.; Wang, H.; Zou, W.; Cao, B., Knockdown of vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 impedes transforming growth factor beta 1-mediated proliferation, migration, and invasion of endometriotic cyst stromal cells. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2019, 17, (1), 69. [CrossRef]

- Chung, M. S.; Han, S. J., Endometriosis-Associated Angiogenesis and Anti-angiogenic Therapy for Endometriosis. Front Glob Womens Health 2022, 3, 856316. [CrossRef]

- Arici, A.; Oral, E.; Attar, E.; Tazuke, S. I.; Olive, D. L., Monocyte chemotactic protein-1 concentration in peritoneal fluid of women with endometriosis and its modulation of expression in mesothelial cells. Fertil Steril 1997, 67, (6), 1065-72. [CrossRef]

- Jolicoeur, C.; Boutouil, M.; Drouin, R.; Paradis, I.; Lemay, A.; Akoum, A., Increased expression of monocyte chemotactic protein-1 in the endometrium of women with endometriosis. Am J Pathol 1998, 152, (1), 125-33.

- Anastasiu, C. V.; Moga, M. A.; Elena Neculau, A.; Bălan, A.; Scârneciu, I.; Dragomir, R. M.; Dull, A. M.; Chicea, L. M., Biomarkers for the Noninvasive Diagnosis of Endometriosis: State of the Art and Future Perspectives. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, (5). [CrossRef]

- Harada, T.; Kubota, T.; Aso, T., Usefulness of CA19-9 versus CA125 for the diagnosis of endometriosis. Fertil Steril 2002, 78, (4), 733-9. [CrossRef]

- Shen, A.; Xu, S.; Ma, Y.; Guo, H.; Li, C.; Yang, C.; Zou, S., Diagnostic value of serum CA125, CA19-9 and CA15-3 in endometriosis: A meta-analysis. J Int Med Res 2015, 43, (5), 599-609. [CrossRef]

- Chantalat, E.; Valera, M. C.; Vaysse, C.; Noirrit, E.; Rusidze, M.; Weyl, A.; Vergriete, K.; Buscail, E.; Lluel, P.; Fontaine, C.; Arnal, J. F.; Lenfant, F., Estrogen Receptors and Endometriosis. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, (8).

- Chen, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhong, Z.; Wei, C.; Zhu, X., Peritoneal immune microenvironment of endometriosis: Role and therapeutic perspectives. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1134663. [CrossRef]

- Vercellini, P.; Buggio, L.; Frattaruolo, M. P.; Borghi, A.; Dridi, D.; Somigliana, E., Medical treatment of endometriosis-related pain. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2018, 51, 68-91. [CrossRef]

- Becker, C. M.; Bokor, A.; Heikinheimo, O.; Horne, A.; Jansen, F.; Kiesel, L.; King, K.; Kvaskoff, M.; Nap, A.; Petersen, K.; Saridogan, E.; Tomassetti, C.; van Hanegem, N.; Vulliemoz, N.; Vermeulen, N.; Group, E. E. G., ESHRE guideline: endometriosis. Hum Reprod Open 2022, 2022, (2), hoac009. [CrossRef]

- Casper, R. F., Progestin-only pills may be a better first-line treatment for endometriosis than combined estrogen-progestin contraceptive pills. Fertil Steril 2017, 107, (3), 533-536. [CrossRef]

- Vercellini, P.; Bracco, B.; Mosconi, P.; Roberto, A.; Alberico, D.; Dhouha, D.; Somigliana, E., Norethindrone acetate or dienogest for the treatment of symptomatic endometriosis: a before and after study. Fertil Steril 2016, 105, (3), 734-743.e3. [CrossRef]

- Surrey, E. S., GnRH agonists in the treatment of symptomatic endometriosis: a review. F S Rep 2023, 4, (2 Suppl), 40-45. [CrossRef]

- Wang, P. H.; Yang, S. T.; Chang, W. H.; Liu, C. H.; Lee, F. K.; Lee, W. L., Endometriosis: Part I. Basic concept. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol 2022, 61, (6), 927-934.

- Saridogan, E.; Becker, C. M.; Feki, A.; Grimbizis, G. F.; Hummelshoj, L.; Keckstein, J.; Nisolle, M.; Tanos, V.; Ulrich, U. A.; Vermeulen, N.; De Wilde, R. L.; Working group of ESGE, E. S. H. R., and WES, Recommendations for the surgical treatment of endometriosis-part 1: ovarian endometrioma. Gynecol Surg 2017, 14, (1), 27. [CrossRef]

- Imperiale, L.; Nisolle, M.; Noël, J. C.; Fastrez, M., Three Types of Endometriosis: Pathogenesis, Diagnosis and Treatment. State of the Art. J Clin Med 2023, 12, (3). [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, A. M.; Viganò, P.; Somigliana, E.; Panina-Bordignon, P.; Vercellini, P.; Candiani, M., The distinguishing cellular and molecular features of the endometriotic ovarian cyst: from pathophysiology to the potential endometrioma-mediated damage to the ovary. Hum Reprod Update 2014, 20, (2), 217-30. [CrossRef]

- Falik, R. C.; Li, A.; Farrimond, F.; Meshkat Razavi, G.; Nezhat, C.; Nezhat, F., Endometrios: classification and surgical management. OBG Manag 2017, 29, 38–43.

- Castellarnau Visus, M.; Ponce Sebastia, J.; Carreras Collado, R.; Cayuela Font, E.; Garcia Tejedor, A., Preliminary results: ethanol sclerotherapy after ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration without anesthesia in the management of simple ovarian cysts. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2015, 22, (3), 475-82. [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C. L.; Shiau, C. S.; Lo, L. M.; Hsieh, T. T.; Chang, M. Y., Effectiveness of ultrasound-guided aspiration and sclerotherapy with 95% ethanol for treatment of recurrent ovarian endometriomas. Fertil Steril 2009, 91, (6), 2709-13. [CrossRef]

- Zondervan, K. T.; Becker, C. M.; Missmer, S. A., Endometriosis. N Engl J Med 2020, 382, (13), 1244-1256.

- Clower, L.; Fleshman, T.; Geldenhuys, W. J.; Santanam, N., Targeting Oxidative Stress Involved in Endometriosis and Its Pain. Biomolecules 2022, 12, (8). [CrossRef]

- Salehi, B.; Butnariu, M.; Corneanu, M.; Sarac, I.; Vlaisavljevic, S.; Kitic, D.; Rahavian, A.; Abedi, A.; Karkan, M. F.; Bhatt, I. D.; Jantwal, A.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Rodrigues, C. F.; Martorell, M.; Martins, N., Chronic pelvic pain syndrome: Highlighting medicinal plants toward biomolecules discovery for upcoming drugs formulation. Phytother Res 2020, 34, (4), 769-787. [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, I.; Banerjee, S.; Driss, A.; Xu, W.; Mehrabi, S.; Nezhat, C.; Sidell, N.; Taylor, R. N.; Thompson, W. E., Curcumin attenuates proangiogenic and proinflammatory factors in human eutopic endometrial stromal cells through the NF-κB signaling pathway. J Cell Physiol 2019, 234, (5), 6298-6312. [CrossRef]

- Cao, W. G.; Morin, M.; Metz, C.; Maheux, R.; Akoum, A., Stimulation of macrophage migration inhibitory factor expression in endometrial stromal cells by interleukin 1, beta involving the nuclear transcription factor NFkappaB. Biol Reprod 2005, 73, (3), 565-70. [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Wei, Y. X.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, X. P.; Zhang, J., Inhibitory effect of curcumin in human endometriosis endometrial cells via downregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor. Mol Med Rep 2017, 16, (4), 5611-5617. [CrossRef]

- Markowska, A.; Antoszczak, M.; Markowska, J.; Huczyński, A., The Role of Selected Dietary Factors in the Development and Course of Endometriosis. Nutrients 2023, 15, (12). [CrossRef]

- Hipólito-Reis, M.; Neto, A. C.; Neves, D., Impact of curcumin, quercetin, or resveratrol on the pathophysiology of endometriosis: A systematic review. Phytother Res 2022, 36, (6), 2416-2433. [CrossRef]

- Farzaei, M. H.; Bahramsoltani, R.; Rahimi, R., Phytochemicals as Adjunctive with Conventional Anticancer Therapies. Curr Pharm Des 2016, 22, (27), 4201-18. [CrossRef]

- Ricci, A. G.; Olivares, C. N.; Bilotas, M. A.; Bastón, J. I.; Singla, J. J.; Meresman, G. F.; Barañao, R. I., Natural therapies assessment for the treatment of endometriosis. Hum Reprod 2013, 28, (1), 178-88. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C. C.; Xu, H.; Man, G. C.; Zhang, T.; Chu, K. O.; Chu, C. Y.; Cheng, J. T.; Li, G.; He, Y. X.; Qin, L.; Lau, T. S.; Kwong, J.; Chan, T. H., Prodrug of green tea epigallocatechin-3-gallate (Pro-EGCG) as a potent anti-angiogenesis agent for endometriosis in mice. Angiogenesis 2013, 16, (1), 59-69. [CrossRef]

- Delenko, J.; Xue, X.; Chatterjee, P. K.; Hyman, N.; Shih, A. J.; Adelson, R. P.; Safaric Tepes, P.; Gregersen, P. K.; Metz, C. N., Quercetin enhances decidualization through AKT-ERK-p53 signaling and supports a role for senescence in endometriosis. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2024, 22, (1), 100. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Zhuang, M. F.; Yang, Y.; Xie, S. W.; Cui, J. G.; Cao, L.; Zhang, T. T.; Zhu, Y., Preliminary study of quercetin affecting the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis on rat endometriosis model. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2014, 2014, 781684. [CrossRef]

- Jamali, N.; Zal, F.; Mostafavi-Pour, Z.; Samare-Najaf, M.; Poordast, T.; Dehghanian, A., Ameliorative Effects of Quercetin and Metformin and Their Combination Against Experimental Endometriosis in Rats. Reprod Sci 2021, 28, (3), 683-692. [CrossRef]

- Zaurito, A.; Mehmeti, I.; Limongelli, F.; Zupo, R.; Annunziato, A.; Fontana, S.; Tardugno, R., Natural compounds for endometriosis and related chronic pelvic pain: A review. Fitoterapia 2024, 179, 106277. [CrossRef]

- Ilhan, M.; Ali, Z.; Khan, I. A.; Taştan, H.; Küpeli Akkol, E., The regression of endometriosis with glycosylated flavonoids isolated from Melilotus officinalis (L.) Pall. in an endometriosis rat model. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol 2020, 59, (2), 211-219. [CrossRef]

- Ilhan, M.; Ali, Z.; Khan, I. A.; Taştan, H.; Küpeli Akkol, E., Bioactivity-guided isolation of flavonoids from Urtica dioica L. and their effect on endometriosis rat model. J Ethnopharmacol 2019, 243, 112100. [CrossRef]

- Kohama, T.; Herai, K.; Inoue, M., Effect of French maritime pine bark extract on endometriosis as compared with leuprorelin acetate. J Reprod Med 2007, 52, (8), 703-8.

- Kim, J. H.; Woo, J. H.; Kim, H. M.; Oh, M. S.; Jang, D. S.; Choi, J. H., Anti-Endometriotic Effects of Pueraria Flower Extract in Human Endometriotic Cells and Mice. Nutrients 2017, 9, (3).

- Park, W.; Park, M. Y.; Song, G.; Lim, W., 5,7-Dimethoxyflavone induces apoptotic cell death in human endometriosis cell lines by activating the endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway. Phytother Res 2020, 34, (9), 2275-2286. [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Song, G.; Lim, W., Myricetin inhibits endometriosis growth through cyclin E1 down-regulation in vitro and in vivo. J Nutr Biochem 2020, 78, 108328. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. Y.; Li, M. Z.; Shen, H. H.; Abudukeyoumu, A.; Xie, F.; Ye, J. F.; Xu, F. Y.; Sun, J. S.; Li, M. Q., Ginsenosides in endometrium-related diseases: Emerging roles and mechanisms. Biomed Pharmacother 2023, 166, 115340. [CrossRef]

- Uchendu, E.; Shukla, M.; Reed, B.; Brown, D.; Saxena, P.; MooYoung, M., Improvement of Ginseng by <i>In Vitro</i> Culture: Challenges and Opportunities. Comprehensive Biotechnology, Vol 4: Agricultural and Related Biotechnologies, 2nd Edition 2011, 317-329.

- Norooznezhad, A. H.; Norooznezhad, F., Cannabinoids: Possible agents for treatment of psoriasis via suppression of angiogenesis and inflammation. Med Hypotheses 2017, 99, 15-18. [CrossRef]

- Brunetti, P.; Lo Faro, A. F.; Pirani, F.; Berretta, P.; Pacifici, R.; Pichini, S.; Busardò, F. P., Pharmacology and legal status of cannabidiol. Ann Ist Super Sanita 2020, 56, (3), 285-291. [CrossRef]

- Kogan, N. M.; Blázquez, C.; Alvarez, L.; Gallily, R.; Schlesinger, M.; Guzmán, M.; Mechoulam, R., A cannabinoid quinone inhibits angiogenesis by targeting vascular endothelial cells. Mol Pharmacol 2006, 70, (1), 51-9. [CrossRef]

- Solinas, M.; Massi, P.; Cantelmo, A. R.; Cattaneo, M. G.; Cammarota, R.; Bartolini, D.; Cinquina, V.; Valenti, M.; Vicentini, L. M.; Noonan, D. M.; Albini, A.; Parolaro, D., Cannabidiol inhibits angiogenesis by multiple mechanisms. Br J Pharmacol 2012, 167, (6), 1218-31. [CrossRef]

- Anvari Aliabad, R.; Hassanpour, K.; Norooznezhad, A. H., Cannabidiol as a possible treatment for endometriosis through suppression of inflammation and angiogenesis. Immun Inflamm Dis 2024, 12, (8), e1370. [CrossRef]

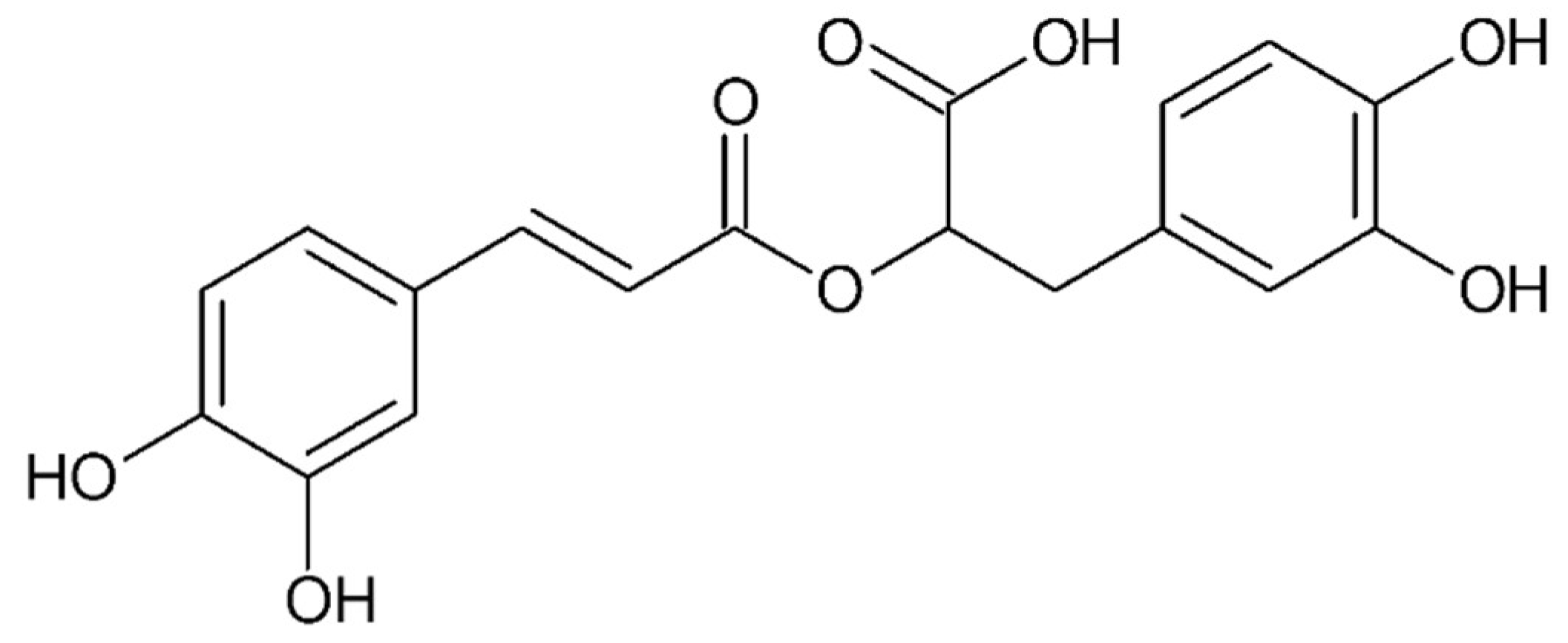

- Alagawany, M.; Abd El-Hack, M. E.; Farag, M. R.; Gopi, M.; Karthik, K.; Malik, Y. S.; Dhama, K., Rosmarinic acid: modes of action, medicinal values and health benefits. Anim Health Res Rev 2017, 18, (2), 167-176. [CrossRef]

- Adomako-Bonsu, A. G.; Chan, S. L.; Pratten, M.; Fry, J. R., Antioxidant activity of rosmarinic acid and its principal metabolites in chemical and cellular systems: Importance of physico-chemical characteristics. Toxicol In Vitro 2017, 40, 248-255. [CrossRef]

- Baba, S.; Osakabe, N.; Natsume, M.; Terao, J., Orally administered rosmarinic acid is present as the conjugated and/or methylated forms in plasma, and is degraded and metabolized to conjugated forms of caffeic acid, ferulic acid and m-coumaric acid. Life Sci 2004, 75, (2), 165-78. [CrossRef]

- Baba, S.; Osakabe, N.; Natsume, M.; Yasuda, A.; Muto, Y.; Hiyoshi, K.; Takano, H.; Yoshikawa, T.; Terao, J., Absorption, metabolism, degradation and urinary excretion of rosmarinic acid after intake of Perilla frutescens extract in humans. Eur J Nutr 2005, 44, (1), 1-9.

- Ferella, L.; Bastón, J. I.; Bilotas, M. A.; Singla, J. J.; González, A. M.; Olivares, C. N.; Meresman, G. F., Active compounds present inRosmarinus officinalis leaves andScutellaria baicalensis root evaluated as new therapeutic agents for endometriosis. Reprod Biomed Online 2018, 37, (6), 769-782. [CrossRef]

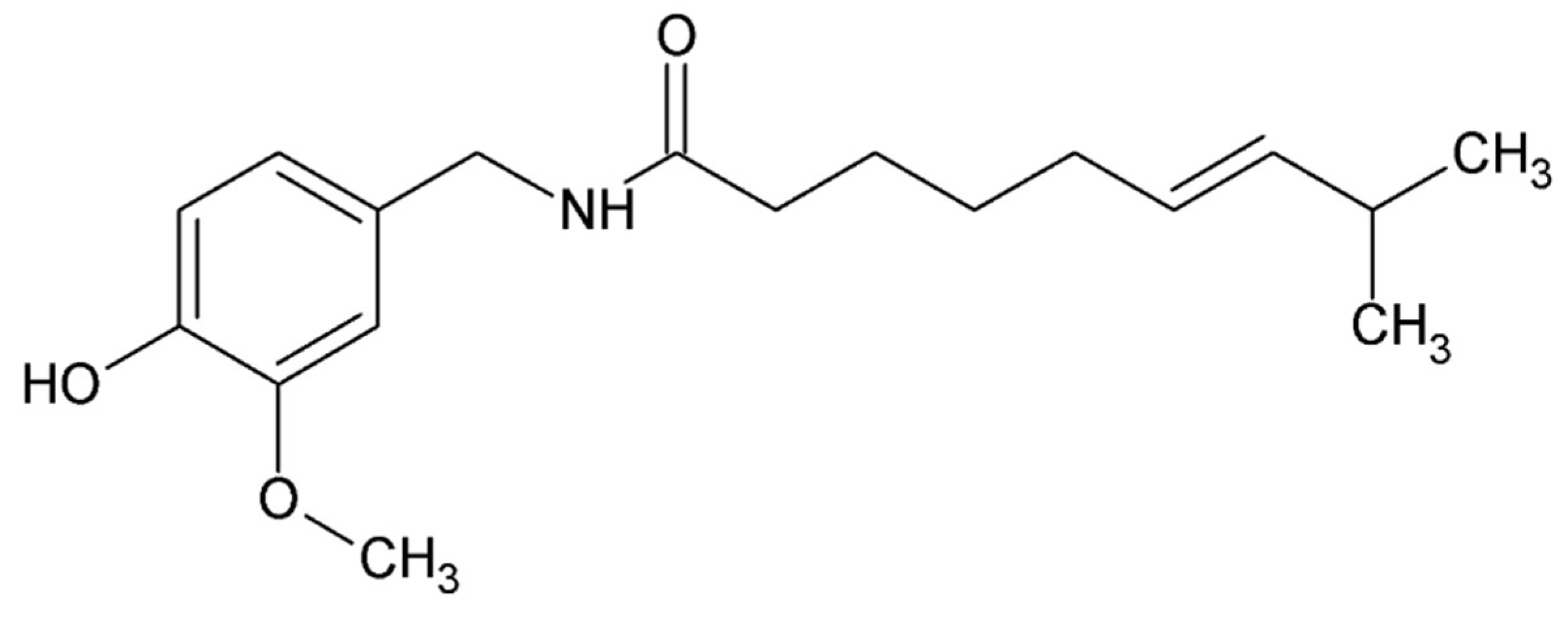

- Holzer, P., Capsaicin: cellular targets, mechanisms of action, and selectivity for thin sensory neurons. Pharmacol Rev 1991, 43, (2), 143-201. [CrossRef]

- Szallasi, A.; Blumberg, P. M., Vanilloid (Capsaicin) receptors and mechanisms. Pharmacol Rev 1999, 51, (2), 159-212. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Bolognese, J.; Calder, N.; Baxendale, J.; Kehler, A.; Cummings, C.; Connell, J.; Herman, G., Effect of morphine and pregabalin compared with diphenhydramine hydrochloride and placebo on hyperalgesia and allodynia induced by intradermal capsaicin in healthy male subjects. J Pain 2008, 9, (12), 1088-95. [CrossRef]

- Wallace, M.; Duan, R.; Liu, W.; Locke, C.; Nothaft, W., A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Crossover Study of the T-Type Calcium Channel Blocker ABT-639 in an Intradermal Capsaicin Experimental Pain Model in Healthy Adults. Pain Med 2016, 17, (3), 551-560. [CrossRef]

- Lembeck, F., Columbus, Capsicum and capsaicin: past, present and future. Acta Physiol Hung 1987, 69, (3-4), 265-73.

- Watson, C. P., Topical capsaicin as an adjuvant analgesic. J Pain Symptom Manage 1994, 9, (7), 425-33. [CrossRef]

- Arora, V.; Campbell, J. N.; Chung, M. K., Fight fire with fire: Neurobiology of capsaicin-induced analgesia for chronic pain. Pharmacol Ther 2021, 220, 107743. [CrossRef]

- Basith, S.; Cui, M.; Hong, S.; Choi, S., Harnessing the Therapeutic Potential of Capsaicin and Its Analogues in Pain and Other Diseases. Molecules 2016, 21, (8). [CrossRef]

- Fattori, V.; Hohmann, M. S.; Rossaneis, A. C.; Pinho-Ribeiro, F. A.; Verri, W. A., Capsaicin: Current Understanding of Its Mechanisms and Therapy of Pain and Other Pre-Clinical and Clinical Uses. Molecules 2016, 21, (7). [CrossRef]

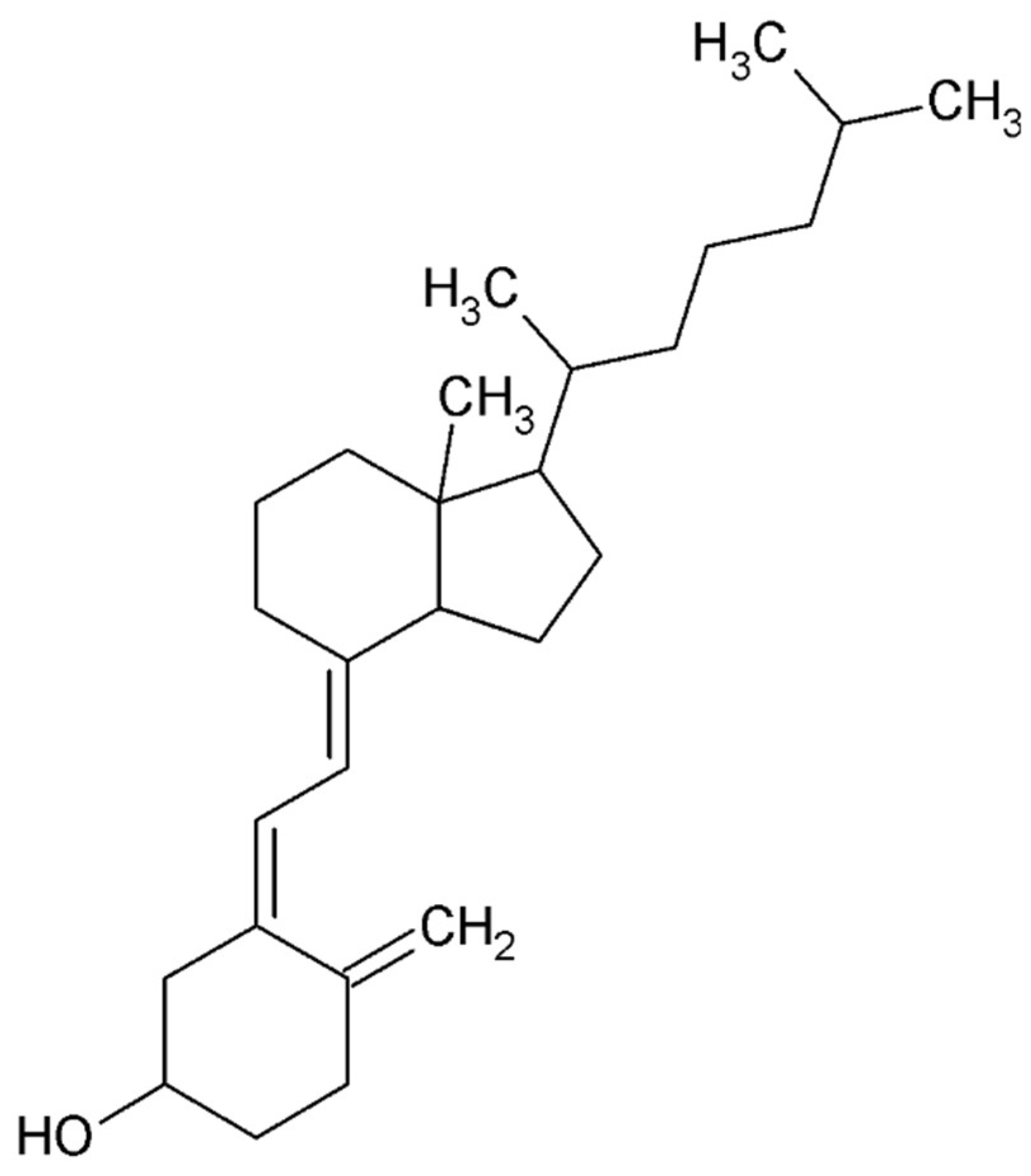

- Qiu, Y.; Yuan, S.; Wang, H., Vitamin D status in endometriosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2020, 302, (1), 141-152. [CrossRef]

- Delbandi, A. A.; Torab, M.; Abdollahi, E.; Khodaverdi, S.; Rokhgireh, S.; Moradi, Z.; Heidari, S.; Mohammadi, T., Vitamin D deficiency as a risk factor for endometriosis in Iranian women. J Reprod Immunol 2021, 143, 103266. [CrossRef]

- Yarmolinskaya, M.; Denisova, A.; Tkachenko, N.; Ivashenko, T.; Bespalova, O.; Tolibova, G.; Tral, T., Vitamin D significance in pathogenesis of endometriosis. Gynecol Endocrinol 2021, 37, (sup1), 40-43. [CrossRef]

- Harris, H. R.; Chavarro, J. E.; Malspeis, S.; Willett, W. C.; Missmer, S. A., Dairy-food, calcium, magnesium, and vitamin D intake and endometriosis: a prospective cohort study. Am J Epidemiol 2013, 177, (5), 420-30. [CrossRef]

- Miyashita, M.; Koga, K.; Izumi, G.; Sue, F.; Makabe, T.; Taguchi, A.; Nagai, M.; Urata, Y.; Takamura, M.; Harada, M.; Hirata, T.; Hirota, Y.; Wada-Hiraike, O.; Fujii, T.; Osuga, Y., Effects of 1,25-Dihydroxy Vitamin D3 on Endometriosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2016, 101, (6), 2371-9. [CrossRef]

- Baek, J. C.; Jo, J. Y.; Lee, S. M.; Cho, I. A.; Shin, J. K.; Lee, S. A.; Lee, J. H.; Cho, M. C.; Choi, W. J., Differences in 25-hydroxy vitamin D and vitamin D-binding protein concentrations according to the severity of endometriosis. Clin Exp Reprod Med 2019, 46, (3), 125-131. [CrossRef]

- Somigliana, E.; Panina-Bordignon, P.; Murone, S.; Di Lucia, P.; Vercellini, P.; Vigano, P., Vitamin D reserve is higher in women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod 2007, 22, (8), 2273-8. [CrossRef]

- Mier-Cabrera, J.; Aburto-Soto, T.; Burrola-Méndez, S.; Jiménez-Zamudio, L.; Tolentino, M. C.; Casanueva, E.; Hernández-Guerrero, C., Women with endometriosis improved their peripheral antioxidant markers after the application of a high antioxidant diet. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2009, 7, 54. [CrossRef]

- Hoorsan, H.; Simbar, M.; Tehrani, F. R.; Fathi, F.; Mosaffa, N.; Riazi, H.; Akradi, L.; Nasseri, S.; Bazrafkan, S., The effectiveness of antioxidant therapy (vitamin C) in an experimentally induced mouse model of ovarian endometriosis. Womens Health (Lond) 2022, 18, 17455057221096218. [CrossRef]

- Erten, O. U.; Ensari, T. A.; Dilbaz, B.; Cakiroglu, H.; Altinbas, S. K.; Çaydere, M.; Goktolga, U., Vitamin C is effective for the prevention and regression of endometriotic implants in an experimentally induced rat model of endometriosis. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol 2016, 55, (2), 251-7. [CrossRef]

- Ansariniya, H.; Hadinedoushan, H.; Javaheri, A.; Zare, F., Vitamin C and E supplementation effects on secretory and molecular aspects of vascular endothelial growth factor derived from peritoneal fluids of patients with endometriosis. J Obstet Gynaecol 2019, 39, (8), 1137-1142. [CrossRef]

- Amini, L.; Chekini, R.; Nateghi, M. R.; Haghani, H.; Jamialahmadi, T.; Sathyapalan, T.; Sahebkar, A., The Effect of Combined Vitamin C and Vitamin E Supplementation on Oxidative Stress Markers in Women with Endometriosis: A Randomized, Triple-Blind Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Pain Res Manag 2021, 2021, 5529741. [CrossRef]

- Mier-Cabrera, J.; Genera-García, M.; De la Jara-Díaz, J.; Perichart-Perera, O.; Vadillo-Ortega, F.; Hernández-Guerrero, C., Effect of vitamins C and E supplementation on peripheral oxidative stress markers and pregnancy rate in women with endometriosis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2008, 100, (3), 252-6. [CrossRef]

- Santanam, N.; Kavtaradze, N.; Murphy, A.; Dominguez, C.; Parthasarathy, S., Antioxidant supplementation reduces endometriosis-related pelvic pain in humans. Transl Res 2013, 161, (3), 189-95.

- Tang, H. C.; Lin, T. C.; Wu, M. H.; Tsai, S. J., Progesterone resistance in endometriosis: A pathophysiological perspective and potential treatment alternatives. Reprod Med Biol 2024, 23, (1), e12588. [CrossRef]

- Critchley, H. O. D.; Chodankar, R. R., 90 YEARS OF PROGESTERONE: Selective progesterone receptor modulators in gynaecological therapies. J Mol Endocrinol 2020, 65, (1), T15-T33. [CrossRef]

- Béliard, A.; Noël, A.; Foidart, J. M., Reduction of apoptosis and proliferation in endometriosis. Fertil Steril 2004, 82, (1), 80-5. [CrossRef]

- Burns, K. A.; Rodriguez, K. F.; Hewitt, S. C.; Janardhan, K. S.; Young, S. L.; Korach, K. S., Role of estrogen receptor signaling required for endometriosis-like lesion establishment in a mouse model. Endocrinology 2012, 153, (8), 3960-71.

- Kulak, J.; Fischer, C.; Komm, B.; Taylor, H. S., Treatment with bazedoxifene, a selective estrogen receptor modulator, causes regression of endometriosis in a mouse model. Endocrinology 2011, 152, (8), 3226-32. [CrossRef]

- Khine, Y. M.; Taniguchi, F.; Nagira, K.; Nakamura, K.; Ohbayashi, T.; Osaki, M.; Harada, T., New insights into the efficacy of SR-16234, a selective estrogen receptor modulator, on the growth of murine endometriosis-like lesions. Am J Reprod Immunol 2018, 80, (5), e13023.

- Harada, T.; Ohta, I.; Endo, Y.; Sunada, H.; Noma, H.; Taniguchi, F., SR-16234, a Novel Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulator for Pain Symptoms with Endometriosis: An Open-label Clinical Trial. Yonago Acta Med 2017, 60, (4), 227-233.

- Clemenza, S.; Vannuccini, S.; Ruotolo, A.; Capezzuoli, T.; Petraglia, F., Advances in targeting estrogen synthesis and receptors in patients with endometriosis. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2022, 31, (11), 1227-1238. [CrossRef]

- Bulun, S. E.; Zeitoun, K. M.; Takayama, K.; Sasano, H., Estrogen biosynthesis in endometriosis: molecular basis and clinical relevance. J Mol Endocrinol 2000, 25, (1), 35-42. [CrossRef]

- Attar, E.; Tokunaga, H.; Imir, G.; Yilmaz, M. B.; Redwine, D.; Putman, M.; Gurates, B.; Attar, R.; Yaegashi, N.; Hales, D. B.; Bulun, S. E., Prostaglandin E2 via steroidogenic factor-1 coordinately regulates transcription of steroidogenic genes necessary for estrogen synthesis in endometriosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009, 94, (2), 623-31.

- Słopień, R.; Męczekalski, B., Aromatase inhibitors in the treatment of endometriosis. Prz Menopauzalny 2016, 15, (1), 43-7. [CrossRef]

- Stanway, S. J.; Purohit, A.; Woo, L. W.; Sufi, S.; Vigushin, D.; Ward, R.; Wilson, R. H.; Stanczyk, F. Z.; Dobbs, N.; Kulinskaya, E.; Elliott, M.; Potter, B. V.; Reed, M. J.; Coombes, R. C., Phase I study of STX 64 (667 Coumate) in breast cancer patients: the first study of a steroid sulfatase inhibitor. Clin Cancer Res 2006, 12, (5), 1585-92. [CrossRef]

- Rižner, T. L.; Romano, A., Targeting the formation of estrogens for treatment of hormone dependent diseases-current status. Front Pharmacol 2023, 14, 1155558. [CrossRef]

- Pavone, M. E.; Bulun, S. E., Aromatase inhibitors for the treatment of endometriosis. Fertil Steril 2012, 98, (6), 1370-9. [CrossRef]

- Ailawadi, R. K.; Jobanputra, S.; Kataria, M.; Gurates, B.; Bulun, S. E., Treatment of endometriosis and chronic pelvic pain with letrozole and norethindrone acetate: a pilot study. Fertil Steril 2004, 81, (2), 290-6. [CrossRef]

- Ferrero, S.; Gillott, D. J.; Venturini, P. L.; Remorgida, V., Use of aromatase inhibitors to treat endometriosis-related pain symptoms: a systematic review. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2011, 9, 89. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, H. S.; Giudice, L. C.; Lessey, B. A.; Abrao, M. S.; Kotarski, J.; Archer, D. F.; Diamond, M. P.; Surrey, E.; Johnson, N. P.; Watts, N. B.; Gallagher, J. C.; Simon, J. A.; Carr, B. R.; Dmowski, W. P.; Leyland, N.; Rowan, J. P.; Duan, W. R.; Ng, J.; Schwefel, B.; Thomas, J. W.; Jain, R. I.; Chwalisz, K., Treatment of Endometriosis-Associated Pain with Elagolix, an Oral GnRH Antagonist. N Engl J Med 2017, 377, (1), 28-40. [CrossRef]

- Sbracia, M.; Scarpellini, F., Use of depot GNRH antagonist (Degarelix) in the treatment of endometriomas (ovarian endometriosis) before IVF: a controlled trial. Fertility and sterility 2015, 104, (3). [CrossRef]

- Franssen, A. M.; Kauer, F. M.; Chadha, D. R.; Zijlstra, J. A.; Rolland, R., Endometriosis: treatment with gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist Buserelin. Fertil Steril 1989, 51, (3), 401-8. [CrossRef]

- Rocha, A. L.; Reis, F. M.; Taylor, R. N., Angiogenesis and endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol Int 2013, 2013, 859619. [CrossRef]

- Bouquet de Joliniere, J.; Fruscalzo, A.; Khomsi, F.; Stochino Loi, E.; Cherbanyk, F.; Ayoubi, J. M.; Feki, A., Antiangiogenic Therapy as a New Strategy in the Treatment of Endometriosis? The First Case Report. Front Surg 2021, 8, 791686. [CrossRef]

- Antônio, L. G. L.; Rosa-E-Silva, J. C.; Machado, D. J.; Westin, A. T.; Garcia, S. B.; Candido-Dos-Reis, F. J.; Poli-Neto, O. B.; Nogueira, A. A., Thalidomide Reduces Cell Proliferation in Endometriosis Experimentally Induced in Rats. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet 2019, 41, (11), 668-672. [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Hung, S. W.; Liang, B.; Zhang, R.; Gao, Y.; Chu, C. Y.; Zhang, T.; Xu, H.; Chung, J. P. W.; Wang, C. C., Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Sunitinib as Novel Immunotherapy to Inhibit Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells for Treatment of Endometriosis. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 641206. [CrossRef]

- Selak, V.; Farquhar, C.; Prentice, A.; Singla, A., Danazol for pelvic pain associated with endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000, (2), CD000068. [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Mamillapalli, R.; Habata, S.; Taylor, H. S., Endometriosis stromal cells induce bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell differentiation and PD-1 expression through paracrine signaling. Mol Cell Biochem 2021, 476, (4), 1717-1727.

- Li, J.; Yan, S.; Li, Q.; Huang, Y.; Ji, M.; Jiao, X.; Yuan, M.; Wang, G., Macrophage-associated immune checkpoint CD47 blocking ameliorates endometriosis. Mol Hum Reprod 2022, 28, (5). [CrossRef]

- D'Hooghe, T. M.; Bambra, C. S.; Raeymaekers, B. M.; De Jonge, I.; Hill, J. A.; Koninckx, P. R., The effects of immunosuppression on development and progression of endometriosis in baboons (Papio anubis). Fertil Steril 1995, 64, (1), 172-8. [CrossRef]

- Chatzianagnosti, S.; Dermitzakis, I.; Theotokis, P.; Kousta, E.; Mastorakos, G.; Manthou, M. E., Application of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Female Infertility Treatment: Protocols and Preliminary Results. Life (Basel) 2024, 14, (9). [CrossRef]

- Laschke, M. W.; Giebels, C.; Nickels, R. M.; Scheuer, C.; Menger, M. D., Endothelial progenitor cells contribute to the vascularization of endometriotic lesions. Am J Pathol 2011, 178, (1), 442-50. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Mamillapalli, R.; Mutlu, L.; Du, H.; Taylor, H. S., Chemoattraction of bone marrow-derived stem cells towards human endometrial stromal cells is mediated by estradiol regulated CXCL12 and CXCR4 expression. Stem Cell Res 2015, 15, (1), 14-22. [CrossRef]

- Artemova, D.; Vishnyakova, P.; Gantsova, E.; Elchaninov, A.; Fatkhudinov, T.; Sukhikh, G., The prospects of cell therapy for endometriosis. J Assist Reprod Genet 2023, 40, (5), 955-967. [CrossRef]

- Yuxue, J.; Ran, S.; Minghui, F.; Minjia, S., Applications of nanomaterials in endometriosis treatment. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2023, 11, 1184155. [CrossRef]

- Othman, E. E.; Salama, S.; Ismail, N.; Al-Hendy, A., Toward gene therapy of endometriosis: adenovirus-mediated delivery of dominant negative estrogen receptor genes inhibits cell proliferation, reduces cytokine production, and induces apoptosis of endometriotic cells. Fertil Steril 2007, 88, (2), 462-71. [CrossRef]

- Egorova, A.; Shubina, A.; Sokolov, D.; Selkov, S.; Baranov, V.; Kiselev, A., CXCR4-targeted modular peptide carriers for efficient anti-VEGF siRNA delivery. Int J Pharm 2016, 515, (1-2), 431-440. [CrossRef]

- Mazzone, M.; Dettori, D.; de Oliveira, R. L.; Loges, S.; Schmidt, T.; Jonckx, B.; Tian, Y. M.; Lanahan, A. A.; Pollard, P.; de Almodovar, C. R.; De Smet, F.; Vinckier, S.; Aragonés, J.; Debackere, K.; Luttun, A.; Wyns, S.; Jordan, B.; Pisacane, A.; Gallez, B.; Lampugnani, M. G.; Dejana, E.; Simons, M.; Ratcliffe, P.; Maxwell, P.; Carmeliet, P., Heterozygous deficiency of PHD2 restores tumor oxygenation and inhibits metastasis via endothelial normalization. Cell 2009, 136, (5), 839-851. [CrossRef]

- Tapmeier, T. T.; Rahmioglu, N.; Lin, J.; De Leo, B.; Obendorf, M.; Raveendran, M.; Fischer, O. M.; Bafligil, C.; Guo, M.; Harris, R. A.; Hess-Stumpp, H.; Laux-Biehlmann, A.; Lowy, E.; Lunter, G.; Malzahn, J.; Martin, N. G.; Martinez, F. O.; Manek, S.; Mesch, S.; Montgomery, G. W.; Morris, A. P.; Nagel, J.; Simmons, H. A.; Brocklebank, D.; Shang, C.; Treloar, S.; Wells, G.; Becker, C. M.; Oppermann, U.; Zollner, T. M.; Kennedy, S. H.; Kemnitz, J. W.; Rogers, J.; Zondervan, K. T., Neuropeptide S receptor 1 is a nonhormonal treatment target in endometriosis. Sci Transl Med 2021, 13, (608). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).