Submitted:

05 May 2025

Posted:

06 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

2.2. Nutritional and Health Characteristics

2.3. Childhood Anemia by Sociodemographic Characteristics

2.4. Childhood Anemia by Nutritional and Health Characteristics

3. Discussion

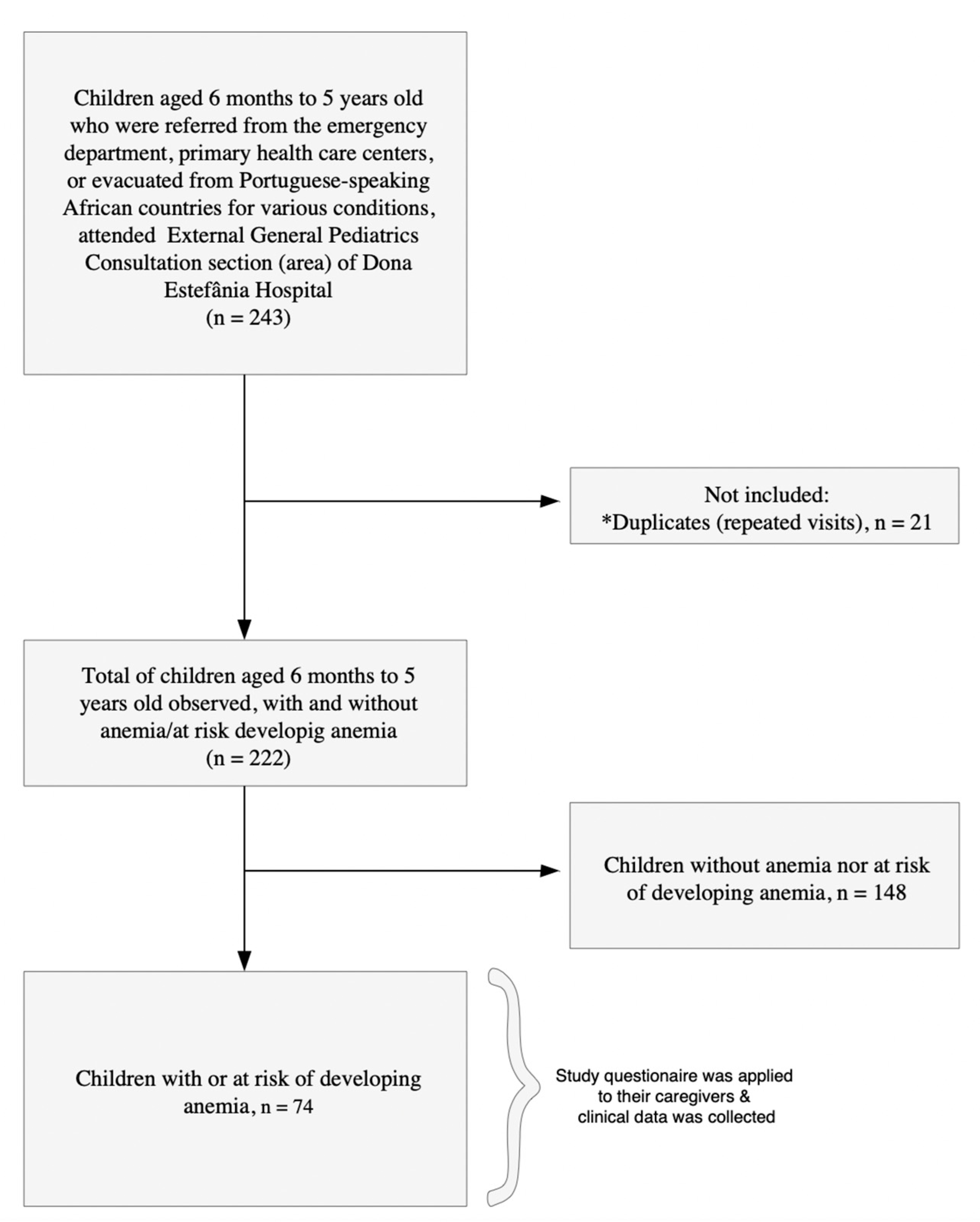

4. Materials and Methods

5. Conclusions

6. Strengths and Limitations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AIDS | Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome |

| CPLP | Community of Portuguese Language Countries |

| ID | Iron deficiency |

| IDA | Iron deficiency anemia |

| Hb | Hemoglobin |

| HIV | Human immunodeficiency virus |

| HDE | Dona Estefânia Hospital |

| MI | Mild anemia |

| MCV | Mean corpuscular volume |

| MO | Moderate anemia |

| RCBs | Red blood cells |

| UI | Uncertainty interval |

| ULS | Unidade Local de Saúde |

References

- Gallagher, P.G. Anemia in the pediatric patient. Blood 2022, 140, 571–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouédraogo, O.; Compaoré, E.W.R.; Kiburente, M.; Dicko, M.H. Prevalence and Associated Factors of Anemia in Children Aged 6 to 59 Months in the Eastern Region of Burkina Faso. Glob. Pediatr. Heal. 2024, 11, 2333794X241263163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. (2023). Anaemia. World Health Organization. Retrieved January 30, 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/anaemia.

- Matysiak, M. Anemia in children: a pediatrician’s view. Acta Haematol. Pol. 2021, 52, 402–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, A.I.; Azevedo, S.; Cabral, J.; Ferreira, M.G.; Sande-Lemos, P.; Ferreira, R.; Trindade, E.; Lima, R.; Antunes, H. Portuguese Consensus on Diagnosis, Treatment, and Management of Anemia in Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease. GE Port. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 27, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelaw, Y.; Getaneh, Z.; Melku, M. Anemia as a risk factor for tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Heal. Prev. Med. 2021, 26, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohene-Agyei, P.; Ndoadoumgue, A.L.; Bana-Ewai, E.; Yaya, I.; Nambiema, A. Population attributable fractions for risk factors for childhood anaemia: Findings from the 2017 Togo Malaria Indicator Survey. Br. J. Nutr. 2025, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, L.; Arnold, C.; Peerson, J.; Long, J.M.; Westcott, J.L.E.; Islam, M.M.; Black, R.E.; Krebs, N.F.; McDonald, C.M. Predictors of Anaemia Among Young Children Receiving Daily Micronutrient Powders (MNPs) for 24 Weeks in Bangladesh: A Secondary Analysis of the Zinc in Powders Trial. Matern. Child Nutr. 2025, e13806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braat, S.; Fielding, K.L.; Han, J.; E Jackson, V.; Zaloumis, S.; Xu, J.X.H.; Moir-Meyer, G.; Blaauwendraad, S.M.; Jaddoe, V.W.V.; Gaillard, R.; et al. Haemoglobin thresholds to define anaemia from age 6 months to 65 years: estimates from international data sources. Lancet Haematol. 2024, 11, e253–e264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, F. S. , Burgess, A., Quinn, V. J., & Osei, A. J. (2015). Nutrition for developing countries (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Qiu, Y.; Long, Z.; Long, Z. Epidemiology of dietary iron deficiency in China from 1990 to 2021: findings from the global burden of disease study 2021. BMC Public Heal. 2025, 25, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaparro, C.M.; Suchdev, P.S. Anemia epidemiology, pathophysiology, and etiology in low- and middle-income countries. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 2019, 1450, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brittenham, G.M.; Moir-Meyer, G.; Abuga, K.M.; Datta-Mitra, A.; Cerami, C.; Green, R.; Pasricha, S.-R.; Atkinson, S.H. Biology of Anemia: A Public Health Perspective. J. Nutr. 2023, 153, S7–S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- USAID Advancing Nutrition. (2022). Understanding anemia and its coexisting factors: A brief. USAID. Retrieved April 2, 2025. Available online: https://www.advancingnutrition.org/sites/default/files/2022-10/usaid-an-anemia-coexisting-brief-2022.pdf.

- Martins, R.R.; Paixão, F.; Mendes, I.; Schäfer, S.; Monge, I.; Costa, F.; Correia, P. Intestinal Parasitic Infections in Children: A 10-Year Retrospective Study. Cureus 2024, 16, e75862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimanda, P.P.; Amukugo, H.J.; Norström, F. Socioeconomic factors associated with anemia among children aged 6-59 months in Namibia. J. Public Heal. Afr. 2020, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melku, M.; Alene, K.A.; Terefe, B.; Enawgaw, B.; Biadgo, B.; Abebe, M.; Muchie, K.F.; Kebede, A.; Melak, T.; Melku, T. Anemia severity among children aged 6–59 months in Gondar town, Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2018, 44, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Liu, X.; Zha, P. Trends in Socioeconomic Inequalities and Prevalence of Anemia Among Children and Nonpregnant Women in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. JAMA Netw. Open 2018, 1, e182899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, A.; Adeleye, K.; Bangura, C.; Wongnaah, F.G. Trends and inequalities in anaemia prevalence among children aged 6–59 months in Ghana, 2003–2022. Int. J. Equity Heal. 2024, 23, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Sun, M.; Wu, T.; Li, J.; Shi, H.; Wei, Y. The association between maternal anemia and neonatal anemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2024, 24, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandran, V.; Kirby, R.S. An Analysis of Maternal, Social and Household Factors Associated with Childhood Anemia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowe, A.; Wood, E.; Gautam, S.K. Maternal Anemia as a Predictor of Childhood Anemia: Evidence from Gambian Health Data. Nutrients 2025, 17, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2011). Haemoglobin concentrations for the diagnosis of anaemia and assessment of severity. World Health Organization. Retrieved April 2, 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-NMH-NHD-MNM-11.1.

- Williams, A. M. Williams, A. M., Ansai, N., Ahluwalia, N., & Nguyen, D. T. (2024). Anemia prevalence: United States, August 2021–August 2023 (NCHS Data Brief No. 519). National Center for Health Statistics. Retrieved April 2, 2025. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db519.htm.

- Leung, A.K.; Lam, J.M.; Wong, A.H.; Hon, K.L.; Li, X. Iron Deficiency Anemia: An Updated Review. Curr. Pediatr. Rev. 2024, 20, 339–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janus, J., & Moerschel, S. K. (2010). Evaluation of anemia in children. American family physician, 81(12), 1462–1471.

- Ngnie-Teta, I.; Receveur, O.; Kuate-Defo, B. Risk Factors for Moderate to Severe Anemia among Children in Benin and Mali: Insights from a Multilevel Analysis. Food Nutr. Bull. 2007, 28, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benedict, R.K.; Pullum, T.W.; Riese, S.; Milner, E. Is child anemia associated with early childhood development? A cross-sectional analysis of nine Demographic and Health Surveys. PLOS ONE 2024, 19, e0298967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maner, B. S., Killeen, R. B., & Moosavi, L. (2024). Mean corpuscular volume. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved April 5, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545275/.

- Turner, J., Parsi, M., & Badireddy, M. (2023). Anemia. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved April 5, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499994/.

- Yeboah, F.A.; Bioh, J.; Amoani, B.; Effah, A.; Senu, E.; Mensah, O.S.O.; Agyei, A.; Kwarteng, S.; Agomuo, S.K.S.; Opoku, S.; et al. Iron deficiency anemia and its association with cognitive function among adolescents in the Ashanti Region - Ghana. BMC Public Heal. 2024, 24, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, J. J., & Kirchner, J. T. (2001). Anemia in children. American family physician, 64(8), 1379–1386.

- Chaudhry, H. S., & Kasarla, M. R. (2025). Microcytic hypochromic anemia. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved April 29, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470252/.

- Sarbay, H.; Ay, Y. Evaluation of children with macrocytosis: clinical study. Pan Afr. Med J. 2018, 31, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, G., & Shaikh, H. (2023). Normochromic normocytic anemia. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved April 29, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK565880/.

- Moore, C. A., Killeen, R. B., & Adil, A. (2025). Macrocytic anemia. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved April 29, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459295/.

- Gardner, W.M.; Razo, C.; A McHugh, T.; Hagins, H.; Vilchis-Tella, V.M.; Hennessy, C.; Taylor, H.J.; Perumal, N.; Fuller, K.; Cercy, K.M.; et al. Prevalence, years lived with disability, and trends in anaemia burden by severity and cause, 1990–2021: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Haematol. 2023, 10, e713–e734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Stevens, G.; Paciorek, C.J.; Flores-Urrutia, M.C.; Borghi, E.; Namaste, S.; Wirth, J.P.; Suchdev, P.S.; Ezzati, M.; Rohner, F.; Flaxman, S.R.; et al. National, regional, and global estimates of anaemia by severity in women and children for 2000–19: a pooled analysis of population-representative data. Lancet Glob. Heal. 2022, 10, e627–e639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2015). Haemoglobin concentrations for the diagnosis of anaemia and assessment of severity. WHO/NMH/NHD/MNM/11.1. Retrieved March 12, 2025. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/177094/9789241564960_eng.pdf.

- Nunes, A.R.; Mairos, J.; Brilhante, D.; Marques, F.; Belo, A.; Cortez, J.; Fonseca, C. Screening for Anemia and Iron Deficiency in the Adult Portuguese Population. Anemia 2020, 2020, 1048283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2022). Global Health Observatory Data Repository: By Category, Child Malnutrition, Anaemia in children.

- Fonseca, C.; Marques, F.; Nunes, A.R.; Belo, A.; Brilhante, D.; Cortez, J. Prevalence of anaemia and iron deficiency in Portugal: the EMPIRE study. Intern. Med. J. 2016, 46, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, F. , Fonseca, C., Robalo Nunes, A., Belo, A., Brilhante, D., & Cortez, J. (2016). Contextualising the High Prevalence of Anaemia in the Portuguese Population: Perception, Characterisation and Predictors: an EMPIRE Sub-Study. Internal Medicine, 23(4), 26–38. [CrossRef]

- Cane, R.M.; Chidassicua, J.B.; Varandas, L.; Craveiro, I. Anemia in Pregnant Women and Children Aged 6 to 59 Months Living in Mozambique and Portugal: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2022, 19, 4685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaré, M.J. , Ferrão, A., Carreira, M., & Morais, A. (2004). Défice de ferro na criança. Acta Pediátrica Portuguesa, 3 (35), 243-247.

- Antunes, H., Gonçalves, S., Teixeira-Pinto, A., Costa-Pereira, A., Tojo-Sierra, R., & Aguiar, Á. (2005). Anemia por deficiência de ferro no lactente: Resultados preliminares do desenvolvimento aos cinco anos. Acta Médica Portuguesa, 18(4), 261–266. Retrieved March 10, 2025. Available online: https://www.actamedicaportuguesa.com/revista/index.php/amp/article/view/1034/702.

- Virella, D.; Pina, M.J. [Prevalence of iron deficiency in early infancy]. . 1998, 11, 607–13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. (2024). Haemoglobin cutoffs to define anaemia in individuals and populations. Guideline Central. Retrieved March 20, 2025. Available online: https://www.guidelinecentral.com/guideline/3534081/#section-3534102.

- World Health Organization. (2023). Nutrition landscape information system (Nlis). Anaemia. Nutrition and nutrition-related health and development data. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. Retrieved March 20, 2025. Available online: https:// www.who.int/data/nutrition/nlis/info/anaemia.

- da Silva, L.L.S.; Fawzi, W.W.; Cardoso, M.A. ; ENFAC Working Group Factors associated with anemia in young children in Brazil. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0204504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E Agho, K.; Dibley, M.J.; D'Este, C.; Gibberd, R. Factors Associated with Haemoglobin Concentration among Timor-Leste Children Aged 6–59 Months. 2008, 26, 200–209.

- Ferreira, H.S.; Vieira, R.C.S.; Livramento, A.R.S.; Dourado, B.L.L.; Silva, G.F.; Calheiros, M.S.C. Prevalence of anaemia in Brazilian children in different epidemiological scenarios: an updated meta-analysis. Public Health Nutr 2021, 24, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, R.F.; Gonzalez, E.S.C.; de Albuquerque, E.C.; de Arruda, I.K.G.; Diniz, A.d.S.; Figueroa, J.N.; Pereira, A.P.C. Prevalence of anemia in under five-year-old children in a children's hospital in Recife, Brazil. Rev. Bras. de Hematol. e Hemoter. 2011, 33, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, C. S. M., Cardoso, M. A., Araújo, T. S., & Muniz, P. T. (2011). Anemia em crianças de 6 a 59 meses e fatores associados no Município de Jordão, Estado do Acre, Brasil. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, 27(5), 1008–1020. Retrieved March 25, 2025. Available online: https://repositorio.usp.br/item/002344964.

- Fançony, C.; Lavinha, J.; Brito, M.; Barros, H. Anemia in preschool children from Angola: a review of the evidence. Porto Biomed. J. 2020, 5, e60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semedo, R.M.; Santos, M.M.; Baião, M.R.; Luiz, R.R.; Da Veiga, G.V. Prevalence of Anaemia and Associated Factors among Children below Five Years of Age in Cape Verde, West Africa. 2014, 32, 646–657.

- Silva, C.C.; Catarino, E. Malnutrition and anemia in children aged 6 to 59 months in the Autonomous Region of Príncipe and its relation to maternal health. Popul. Med. 2023, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ncogo, P.; Romay-Barja, M.; Benito, A.; Aparicio, P.; Nseng, G.; Berzosa, P.; Santana-Morales, M.A.; Riloha, M.; Valladares, B.; Herrador, Z. Prevalence of anemia and associated factors in children living in urban and rural settings from Bata District, Equatorial Guinea, 2013. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0176613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aly, M.M.; Berti, C.; Chemane, F.; Macuelo, C.; Marroda, K.R.; La Vecchia, A.; Agostoni, C.; Baglioni, M. Prevalence of anemia among children aged 6–59 months in the Ntele camp for internally displaced persons (Cabo Delgado, Mozambique): a preliminary study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2025, 79, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cane, R.M.; Keita, Y.; Lambo, L.; Pambo, E.; Gonçalves, M.P.; Varandas, L.; Craveiro, I. Prevalence and factors related to anaemia in children aged 6–59 months attending a quaternary health facility in Maputo, Mozambique. Glob. Public Heal. 2023, 18, 2278876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhajarine, N.; A Adeyinka, D.; Matandalasse, M.; Chicumbe, S. Inequities in childhood anaemia at provincial borders in Mozambique: cross-sectional study results from multilevel Bayesian analysis of 2018 National Malaria Indicator Survey. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e051395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailu, B.A. Mapping, trends, and factors associated with anemia among children aged under 5 y in East Africa. Nutrition 2023, 116, 112202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huamani, M.A.A.; Aliaga-Gastelumendi, R.A. Calidad de atención y satisfacción del usuario en un Servicio de Emergencia de un Hospital del Seguro Social. Acta MEDICA Peru. 2023, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebede, D.; Getaneh, F.; Endalamaw, K.; Belay, T.; Fenta, A. Prevalence of anemia and its associated factors among under-five age children in Shanan gibe hospital, Southwest Ethiopia. BMC Pediatr. 2021, 21, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mghanga, F.P.; Genge, C.M.; Yeyeye, L.; Twalib, Z.; Kibopile, W.; Rutalemba, F.J.; Shengena, T.M. Magnitude, Severity, and Morphological Types of Anemia in Hospitalized Children Under the Age of Five in Southern Tanzania. Cureus 2017, 9, e1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraz, I. S. , Daneluzzi, J. C., Vannucchi, H., Jordão, A. A., Jr, Ricco, R. G., Del Ciampo, L. A., Martinelli, C. E., Jr, Engelberg, A. A., Bonilha, L. R., & Custódio, V. I. (2005). Prevalência da carência de ferro e sua associação com a deficiência de vitamina A em pré-escolares [Prevalence of iron deficiency and its association with vitamin A deficiency in preschool children]. Jornal de Pediatria, 81(2), 169–174.

- Gompakis, N.; Economou, M.; Tsantali, C.; Kouloulias, V.; Keramida, M.; Athanasiou-Metaxa, M. The Effect of Dietary Habits and Socioeconomic Status on the Prevalence of Iron Deficiency in Children of Northern Greece. Acta Haematol. 2007, 117, 200–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Ruzafa, E.; Vázquez-López, M.A.; Galera-Martínez, R.; Lendínez-Molinos, F.; Gómez-Bueno, S.; Martín-González, M. Prevalence and associated factors of iron deficiency in Spanish children aged 1 to 11 years. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2021, 180, 2773–2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tympa-Psirropoulou, E.; Vagenas, C.; Dafni, O.; Matala, A.; Skopouli, F. Environmental risk factors for iron deficiency anemia in children 12-24 months old in the area of Thessalia in Greece. . 2008, 12, 240–50. [Google Scholar]

- Akkermans, M.D.; van der Horst-Graat, J.M.; Eussen, S.R.; van Goudoever, J.B.; Brus, F. Iron and Vitamin D Deficiency in Healthy Young Children in Western Europe Despite Current Nutritional Recommendations. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2016, 62, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, L.C.-B.; Paixão, F.; Costa, F.; Correia, P. Migrant Pathology Screening in the Pediatric Population: A Five-Year Retrospective Study From a Level II Hospital. Cureus 2024, 16, e53770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Merwe, L.F.; Eussen, S.R. Iron status of young children in Europe. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 106, 1663S–1671S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leal, L.P.; Filho, M.B.; de Lira, P.I.C.; Figueiroa, J.N.; Osório, M.M. Prevalência da anemia e fatores associados em crianças de seis a 59 meses de Pernambuco. Rev. de Saude publica 2011, 45, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aheto, J.M.K.; Alhassan, Y.; Puplampu, A.E.; Boglo, J.K.; Sedzro, K.M. Anemia prevalence and its predictors among children under-five years in Ghana. A multilevel analysis of the cross-sectional 2019 Ghana Malaria Indicator Survey. Heal. Sci. Rep. 2023, 6, e1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belachew, A.; Tewabe, T. Under-five anemia and its associated factors with dietary diversity, food security, stunted, and deworming in Ethiopia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst. Rev. 2020, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, S.E.; Zerga, A.A.; Mekonnen, T.C.; Tadesse, A.W.; Hussien, F.M.; Feleke, Y.W.; Anagaw, M.Y.; Ayele, F.Y. Burden and Determinants of Anemia among Under-Five Children in Africa: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Anemia 2022, 2022, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mboya, I.B.; Mamseri, R.; Leyaro, B.J.; George, J.; Msuya, S.E.; Mgongo, M. Prevalence and factors associated with anemia among children under five years of age in Rombo district, Kilimanjaro region, Northern Tanzania. F1000Research 2020, 9, 1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omer, A.; Hailu, D.; Nigusse, G.; Mulugeta, A. Magnitude and morphological types of anemia differ by age among under five children: A facility-based study. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Torres, V.; Torres, N.; A Davis, J.; Corrales-Medina, F.F. Anemia and Associated Risk Factors in Pediatric Patients. Pediatr. Heal. Med. Ther. 2023, ume 14, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunardi, D.; Bardosono, S.; Basrowi, R.W.; Wasito, E.; Vandenplas, Y. Dietary Determinants of Anemia in Children Aged 6–36 Months: A Cross-Sectional Study in Indonesia. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, S. N., Madeira, S., Sobral, M. A., & Delgadinho, G. (2016). Hemoglobinopatias em Portugal e a intervenção do médico de família. Revista Portuguesa de Medicina Geral e Familiar, 32, 416–424. Available online: https://rpmgf.pt/ojs/index.php/rpmgf/article/view/11963.

- Estrela, P. (2009). A saúde dos imigrantes em Portugal. Revista Portuguesa de Clínica Geral, 25, 45–55. Available online: https://rpmgf.pt/ojs/index.php/rpmgf/article/view/10590.

- Raju, A. A. Raju, A. A., Boddu, A. B., Raju, D. S. S. K., & Surabhi, U. S. (2023). The prevalence and predictors of iron deficiency anemia in toddlers: A population-based study. Journal of Advances in Medicine and Pharmacy, 6(2), 648–651. Retrieved March 25, 2025. Available online: https://academicmed.org/Uploads/Volume6Issue2/137.%20[3019.%20JAMP_PH]%20648-651.pdf.

- Shibeshi, A.H.; Mare, K.U.; Kase, B.F.; Wubshet, B.Z.; Tebeje, T.M.; Asgedom, Y.S.; Asmare, Z.A.; Asebe, H.A.; Lombebo, A.A.; Sabo, K.G.; et al. The effect of dietary diversity on anemia levels among children 6–23 months in sub-Saharan Africa: A multilevel ordinal logistic regression model. PLOS ONE 2024, 19, e0298647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathuria, N.; Bandyopadhyay, P.; Srivastava, S.; Garg, P.R.; Devi, K.S.; Kurian, K.; Rathi, S.K.; Mehra, S. Association of minimum dietary diversity with anaemia among 6–59 months’ children from rural India: An evidence from a cross-sectional study. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2023, 12, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soliman, A.T.; De Sanctis, V.; Yassin, M.; Wagdy, M.; Soliman, N. Chronic anemia and thyroid function. Acta Bio-Medica Atenei Parmensis 2017, 88, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chand, D.H.; Valentini, R.P. Chronic Kidney Disease: Treatment of Comorbidities II (Hypertension, Anemia, and Electrolyte Management). Curr. Treat. Options Pediatr. 2019, 5, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministério dos Negócios Estrangeiros. (2025). Sobre Portugal. Portal Diplomático. Retrieved February 19, 2025. Available online: https://portaldiplomatico.mne.gov.pt/sobre-portugal.

- European Union. (2024). Portugal. Retrieved February 6, 2025. Available online: https://european-union.europa.eu/principles-countries-history/eu-countries/portugal_en.

- European Parliament. (2019). Economic, social and territorial situation of Portugal: Briefing requested by the REGI committee. Retrieved February 6, 2025, Available online:. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2019/629190/IPOL_BRI (accessed on day month year).

- Serviço Nacional de Saúde. (2025). Unidade Local de Saúde de São José. Retrieved February 20, 2025. Available online: https://www.sns.gov.pt/entidades-de-saude/unidade-local-de-saude-de-sao-jose/.

- Hospital Dona Estefânia. (2025). ULS São José: Contexto regional e nacional da instituição.

- Staples, A.O.; Wong, C.S.; Smith, J.M.; Gipson, D.S.; Filler, G.; Warady, B.A.; Martz, K.; Greenbaum, L.A. Anemia and Risk of Hospitalization in Pediatric Chronic Kidney Disease. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2009, 4, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2025). Child growth standards. World Health Organization. Retrieved March 15, 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/tools/child-growth-standards/standards.

- IBM Corp. (2021). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 28.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

| Variables (n = 74) | Categories | N | % |

| Sex | Male | 42 | 56.8 |

| Female | 32 | 43.2 | |

| Child´s age | 6 months - 1 year | 28 | 37.8 |

| 2 -3 years | 29 | 39.2 | |

| 4-5 years | 17 | 23.0 | |

| Country of residence | Portugal | 73 | 98.6 |

| Cape Verde | 1 | 1.4 | |

| Region of residence | Metropolitan Lisbon Area (Greater Lisbon) | 61 | 82.4 |

| Other regions (Setúbal peninsula, Alentejo, Madeira, West and Tagus Valley, etc) | 13 | 17.6 | |

| Caregiver's Degree of Kinship | Mother | 63 | 85.1 |

| Father | 11 | 14.9 | |

| Caregiver´s Level of Education | Basic/Primary or Secondary Level | 41 | 55.4 |

| Technical or Higher education (bachelor's, master's, doctorate) | 22 | 29.7 | |

| Other | 11 | 14.9 | |

| Country of origin of the child´s mother | Portugal | 20 | 29.9 |

| CPLP | 32 | 47.8 | |

| Other countries | 15 | 22.4 | |

| Mother's occupation (by role) | Specialized Intellectual and scientific roles | 5 | 12.2 |

| Administrative, Managerial, or Support roles | 36 | 87.8 | |

| Country of origin of the child's father | Portugal | 18 | 34.6 |

| Other countries | 34 | 65.4 | |

| Father´s occupation (by role) | Administrative, Managerial, or Support roles | 18 | 45.0 |

| Other roles | 22 | 55.0 | |

| Notes: | • CPLP: Community of Portuguese Language Countries. • Mother’s other origin countries included: Nepal, Bangladesh, Ukraine, Lithuania, Spain, India, Venezuela, Ivory Coast, and the Republic of Guinea (Conakry). Father’s other countries of origin included CPLP countries, Nepal, Bangladesh, India, and Ukraine. | ||

| • Mother’s occupation, by roles, includes two large groups, namely: Specialized Intellectual and Scientific roles (experts in intellectual and scientific professions) and Administrative, Managerial or Support roles (administrative staff and similar, managers, self-employed individuals, entrepreneurs, service and sales staff, and unemployed or domestic workers). | |||

| • Father’s occupation, by roles, includes two large groups, namely: Administrative, Managerial, or Support roles (administrative staff and similar, managers, self-employed individuals, entrepreneurs, service and sales staff, and unemployed or domestic workers) and other roles (experts in intellectual and scientific professions, technicians and professionals at the intermediate level, and industrial, agricultural, and fishing workers). | |||

| Variables (n = 74) | Categories | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nutritional characteristics | History of exclusive breastfeeding | Yes (Past/Present) | 55 | 83.3 |

| No | 11 | 16.7 | ||

| Duration of breastfeeding | 1-5 months | 21 | 42.0 | |

| 6-12 months | 29 | 58.0 | ||

| Complementary feeding* | Yes | 64 | 86.5 | |

| No | 10 | 13.5 | ||

| Cereal porridge intake | Yes | 43 | 58.9 | |

| No | 30 | 41.1 | ||

| Number of meals/days | 3-4 meals/day | 25 | 34.7 | |

| 5 or more meals/day | 47 | 65.3 | ||

| Cereals and derivatives, tubes | Yes | 57 | 77.0 | |

| No | 17 | 23.0 | ||

| Meat, fish, and eggs | Yes | 65 | 87.8 | |

| No | 9 | 12.2 | ||

| Dairy products | Yes | 70 | 94.6 | |

| No | 4 | 5.4 | ||

| Fruits | Yes | 63 | 85.1 | |

| No | 11 | 14.9 | ||

| Legumes | Yes | 67 | 90.5 | |

| No | 7 | 9.5 | ||

| Vegetables | Yes | 53 | 71.6 | |

| No | 21 | 28.4 | ||

| Fats and oils | Yes | 14 | 18.9 | |

| No | 60 | 81.1 | ||

| Minimum dietary diversity | Adequate (4 or more food groups) | 61 | 82.4 | |

| Inadequate (1-3 food groups) | 13 | 17.6 | ||

| Excessive milk consumption | Yes (> 500mL/day) | 8 | 10.8 | |

| No | 66 | 89.2 | ||

| Supplements intake | Yes | 39 | 52.7 | |

| No | 35 | 47.3 | ||

| Type of supplements | Iron | 25 | 64.1 | |

| Iron, folic acid, and vitamin B12, and/or multivitamins | 14 | 35.9 | ||

| Anthropometric characteristics | Weight percentile | Adequate weight for age (Percentile 3-97) | 30 | 88.2 |

| Not adequate for age [Percentile <3 (low weight for age) or Percentile >97 (high weight for age] | 4 | 11.8 | ||

| Child anemia | Anemia based on hemoglobin (Hb) level | Has anemia/At risk of developing anemia (11.0g/dL≤Hb≤11.4g/dL) | 66 | 94.3 |

| Without anemia (Hb>11.4g/dL) | 4 | 5.7 | ||

| Anemia severity, based on hemoglobin (Hb) level | Borderline or pre-anemic stage (11.0 g/dL ≤ Hb ≤ 11.4 g/dL | 7 | 10.6 | |

| Mild (10.0 g/dL ≤ Hb ≤ 10.9 g/dL) | 36 | 54.5 | ||

| Moderate (7.0 g/dL ≤ Hb ≤ 9.9 g/dL) | 23 | 34.8 | ||

| Anemia based on hematocrit (%) level | Has anemia (Hematocrit<34.0%) | 59 | 85.5 | |

| Normal (34.0%≤Hematocrit≤40.0%) | 10 | 14.5 | ||

| Anemia based on the size of red blood cells (RCBs) measured by the mean corpuscular volume (MCV) | Microcytic (<80 fL) | 64 | 91,4 | |

| Normocytic (80-100 fL) | 6 | 8.6 | ||

| Iron deficiency by serum iron level | Iron deficiency (Serum iron < 30.0 mcg/dL) | 10 | 37.0 | |

| Mild iron deficiency /Pre-anemic stage (30.0 mcg/dL ≤ Serum iron ≤ 50.0 mcg/dL) | 10 | 37.0 | ||

| Normal (> 50.0 mcg/dL-120.0 mcg/dL) | 7 | 25.9 | ||

| Iron deficiency anemia (IDA) by ferritin level | Iron deficiency anemia (Ferritin< 12 ng/mL) | 12 | 40.0 | |

| Adequate iron storage in children with infection or inflammation/ IDA in children with no inflammation (12-30 ng/mL) | 4 | 13.3 | ||

| Normal (> 30.0 ng/mL) | 12 | 40.0 | ||

| Risk of iron overload (> 500.0 ng/mL) | 2 | 6.7 | ||

| Sickle cell trait | Yes (Sickle trait cell) | 3 | 33.3 | |

| No/pendent | 6 | 66.7 | ||

| Health characteristics | Vomit or refusal to eat** | Yes (had vomited or refused to eat) | 12 | 16.2 |

| No | 62 | 83.8 | ||

| Presence of infection or inflammation by C-reactive protein (CRP) level | Yes (CRP > 5.0 mg/mL) | 15 | 31.9 | |

| No (CRP <5.0 mg/mL) | 32 | 68.1 | ||

| Blood glucose level | Normal (60.0–180.0 mg/dL) | 18 | 100.0 | |

| Bilirubin | Hyperbilirubinemia (Bilirubin>1.20 mg/dL) | 10 | 90.9 | |

| Normal (0.30-1.20 mg/dL) | 1 | 9.1 | ||

| Urea | Uremia (Blood urea >36.0mg/dL) | 5 | 13.9 | |

| Normal (5.0-36.0mg/dL) | 31 | 86.1 | ||

| Had any hospitalization (in the past) | Yes | 23 | 31.9 | |

| No | 49 | 68.1 | ||

| Duration of hospitalization (in days) | Up to 5 days | 7 | 53.8 | |

| More than 5 days | 6 | 46.2 | ||

| Notes: | (*) Children whose mothers reported that they had either previously received or were currently receiving complementary feeding.(**) Children whose mothers reported a history of food selectivity behavior (e.g., children who eat "normally" at kindergarten or school but refuse to eat the same foods at home), refusal to eat certain types of food (such as meat), or vomiting after consuming certain types of food (e.g., due to irritability or irritated behavior, abdominal pain, or an unspecified reason). | |||

| Characteristics | Categories | Cases of anemia based on hemoglobin (Hb) | Cases of anemia based on hematocrit (%) | Cases of anemia based on mean corpuscular value (MCV) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Has anemia/At risk of developing anemia (11.0g/dL≤Hb≤11.4g/dL) | Without anemia (Hb>11.4g/dL) | Has anemia (<33.0%) | Normal (34.0%-40.0%) | Microcytic anemia(<80 fL) | Normocytic anemia (80-100 fL) | ||||||||

| n | % | n | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | n | % | ||

| Gender | Male | 36 | 54.5 | 3 | 75.0 | 34 | 57.6 | 4 | 40.0 | 35 | 54.7 | 4 | 66.7 |

| Female | 30 | 45.5 | 1 | 25.0 | 25 | 42.4 | 6 | 60.0 | 29 | 45.3 | 2 | 33.3 | |

| Child´s age | 6 months - 1 year | 23 | 34.8 | 1 | 25.0 | 22 | 37.3 | 2 | 20.0 | 21 | 32.8 | 4 | 66.7 |

| 2 -3 years | 26 | 39.4 | 3 | 75.0 | 23 | 39.0 | 6 | 60.0 | 29 | 45.3 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| 4-5 years | 17 | 25.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 14 | 23.7 | 2 | 20.0 | 14 | 21.9 | 2 | 33.3 | |

| Region of residence | Metropolitan Lisbon Area (Greater Lisbon) | 54 | 81.8 | 3 | 75.0 | 48 | 81.4 | 9 | 90.0 | 53 | 82.8 | 4 | 66.7 |

| Other regions (Setúbal peninsula, Alentejo, Madeira, West and Tagus Valley, etc) | 12 | 18.2 | 1 | 25.0 | 11 | 18.6 | 1 | 10.0 | 11 | 17.2 | 2 | 33.3 | |

| Caregiver's Degree of Kinship | Mother | 56 | 84.8 | 4 | 100.0 | 50 | 84.7 | 9 | 90.0 | 54 | 84.4 | 6 | 100.0 |

| Father | 10 | 15.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 9 | 15.3 | 1 | 10.0 | 10 | 15.6 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Caregiver´s Level of Education | Basic/Primary or Secondary Level | 39 | 59.1 | 1 | 25.0 | 34 | 57.6 | 5 | 50.0 | 36 | 56.3 | 3 | 50.0 |

| Technical or Higher education (bachelor's, master's, doctorate) | 17 | 25.8 | 2 | 50.0 | 17 | 28.8 | 2 | 20.0 | 17 | 26.6 | 3 | 50.0 | |

| Other | 10 | 15.2 | 1 | 25.0 | 8 | 13.6 | 3 | 30.0 | 11 | 17.2 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Country of origin of the child's mother | Portugal | 18 | 30.0 | 2 | 50.0 | 17 | 31.5 | 3 | 33.3 | 19 | 32.8 | 1 | 16.7 |

| CPLP | 29 | 48.3 | 1 | 25.0 | 24 | 44.4 | 5 | 55.6 | 26 | 44.8 | 4 | 66.7 | |

| Other countries | 13 | 21.7 | 1 | 25.0 | 13 | 24.1 | 1 | 11.1 | 13 | 22.4 | 1 | 16.7 | |

| Mother's occupation (by role) | Specialized Intellectual and scientific roles | 3 | 8.8 | 1 | 2.0 | 3 | 9.1 | 2 | 50.0 | 5 | 13.2 | - | - |

| Administrative, Managerial or Support roles | 31 | 91.2 | 3 | 75.0 | 30 | 90.9 | 2 | 50.0 | 33 | 86.8 | - | - | |

| Country of origin of the child's father | Portugal | 15 | 33.3 | 3 | 75.0 | 14 | 32.6 | 4 | 80.0 | 18 | 39.1 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Other countries | 30 | 66.7 | 1 | 25.0 | 29 | 67.4 | 1 | 20.0 | 28 | 60.9 | 3 | 100.0 | |

| Father´s occupation (by role) | Administrative, Managerial or Support roles | 15 | 45.5 | 1 | 25.0 | 15 | 46.9 | 2 | 50.0 | 17 | 45.9 | - | - |

| Other roles | 18 | 54.5 | 3 | 75.0 | 17 | 53.1 | 2 | 50.0 | 20 | 54.1 | - | - | |

| Notes: | •Metropolitan Lisbon area: Amadora, Barreiro, Cascais, Lisbon, Loures, Moita, Montijo, Odivelas, Seixal, Sintra, Sesimbra, Vila Franca de Xira. •CPLP: Community of Portuguese Language Countries. •Mother’s other origin countries included: Nepal, Bangladesh, Ukraine, Lithuania, Spain, India, Venezuela, Ivory Coast, and the Republic of Guinea (Conakry). Father’s other countries of origin included CPLP countries, Nepal, Bangladesh, India, and Ukraine. | ||||||||||||

| •Mother’s occupation, by roles, includes two large groups, namely: Specialized Intellectual and Scientific roles (experts in intellectual and scientific professions) and Administrative, Managerial or Support roles (administrative staff and similar, managers, self-employed individuals, entrepreneurs, service and sales staff, and unemployed or domestic workers). | |||||||||||||

| •Father’s occupation, by roles, includes two large groups, namely: Administrative, Managerial, or Support roles (administrative staff and similar, managers, self-employed individuals, entrepreneurs, service and sales staff, and unemployed or domestic workers) and Other roles (experts in intellectual and scientific professions, technicians and professionals of intermediate level, industrial, agricultural and fishing workers). | |||||||||||||

| Characteristics | Categories | Cases of anemia based on hemoglobin (Hb) | Cases of anemia based on hematocrit (%) | Cases of anemia based on mean corpuscular value (MCV) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Has anemia/At risk of developing anemia (11.0g/dL≤Hb≤11.4g/dL) | Without anemia (Hb>11.4g/dL) | Has anemia (<33.0%) | Normal (34.0%-40.0%) | Microcytic anemia (<80 fL) | Normocytic anemia (80-100 fL) | |||||||||

| n | % | N | % | N | % | n | % | N | % | n | % | |||

| Nutritional characteristics | History of exclusive breastfeeding | Yes (Past/Present) | 48 | 81.4 | 4 | 100.0 | 43 | 81.1 | 9 | 90.0 | 51 | 87.9 | 2 | 33.3 |

| No | 11 | 18.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 10 | 18.9 | 1 | 10.0 | 7 | 12.1 | 4 | 66.7 | ||

| Duration of breastfeeding | 1-5 months | 18 | 40.9 | 1 | 33.3 | 17 | 42.5 | 3 | 42.9 | 19 | 41.3 | 1 | 50.0 | |

| 6-12 months | 26 | 59.1 | 2 | 66.7 | 23 | 57.5 | 4 | 57.1 | 27 | 58.7 | 1 | 50.0 | ||

| History of complementary feeding | Yes (Past/Present) | 56 | 84.8 | 4 | 100.0 | 49 | 83.1 | 10 | 100.0 | 57 | 89.1 | 3 | 50.0 | |

| No | 10 | 15.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 10 | 16.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 7 | 10.9 | 3 | 50.0 | ||

| Cereal porridge intake | Yes | 40 | 61.5 | 1 | 25.0 | 34 | 58.6 | 6 | 60.0 | 35 | 55.6 | 5 | 83.3 | |

| No | 25 | 38.5 | 3 | 75.0 | 24 | 41.4 | 4 | 40.0 | 28 | 44.4 | 1 | 16.7 | ||

| Number of meals/days | 3-4 meals/day | 23 | 35.9 | 3 | 75.0 | 18 | 31.6 | 6 | 60.0 | 22 | 34.9 | 2 | 40.0 | |

| 5 or more meals/day | 41 | 64.1 | 1 | 25.0 | 39 | 68.4 | 4 | 40.0 | 41 | 65.1 | 3 | 60.0 | ||

| Cereals and derivatives, tubes | Yes | 52 | 78.8 | 2 | 50.0 | 48 | 81.4 | 4 | 40.0 | 49 | 76.6 | 4 | 66.7 | |

| No | 14 | 21.2 | 2 | 50.0 | 11 | 18.6 | 6 | 60.0 | 15 | 23.4 | 2 | 33.3 | ||

| Meat, fish, and eggs | Yes | 57 | 86.4 | 4 | 100.0 | 50 | 84.7 | 10 | 100.0 | 57 | 89.1 | 4 | 66.7 | |

| No | 9 | 13.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 9 | 15.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 7 | 10.9 | 2 | 33.3 | ||

| Dairy products | Yes | 62 | 93.9 | 4 | 100.0 | 55 | 93.2 | 10 | 100.0 | 62 | 96.9 | 4 | 66.7 | |

| No | 4 | 6.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 6.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 3.1 | 3 | 33.3 | ||

| Fruits | Yes | 56 | 84.8 | 4 | 100.0 | 50 | 84.7 | 9 | 90.0 | 56 | 87.5 | 4 | 66.7 | |

| No | 10 | 15.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 9 | 15.3 | 1 | 10.0 | 8 | 12.5 | 2 | 33.3 | ||

| Legumes | Yes | 59 | 89.4 | 4 | 100.0 | 53 | 89.8 | 9 | 90.0 | 59 | 92.2 | 4 | 66.7 | |

| No | 7 | 10.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 10.2 | 1 | 10.0 | 5 | 7.8 | 2 | 33.3 | ||

| Vegetables | Yes | 49 | 74.2 | 1 | 25.0 | 45 | 76.3 | 5 | 50.0 | 45 | 70.3 | 5 | 83.3 | |

| No | 17 | 25.8 | 3 | 75.0 | 14 | 23.7 | 5 | 50.0 | 19 | 29.7 | 1 | 16.7 | ||

| Fats and oils | Yes | 14 | 21.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 13 | 22.0 | 1 | 10.0 | 14 | 21.9 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| No | 52 | 78.8 | 4 | 100.0 | 46 | 78.0 | 9 | 90.0 | 50 | 78.1 | 6 | 100.0 | ||

| Minimum dietary diversity | Adequate (4 or more food groups) | 53 | 80.3 | 4 | 100.0 | 47 | 79.7 | 9 | 90.0 | 56 | 87.5 | 1 | 16.7 | |

| Inadequate (1-3 food groups) | 13 | 19.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 12 | 20.3 | 1 | 10.0 | 8 | 12.5 | 5 | 83.3 | ||

| Excessive milk consumption | Yes (> 500mL/day) | 6 | 9.1 | 2 | 50.0 | 6 | 10.2 | 1 | 10.0 | 8 | 12.5 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| No | 60 | 90.9 | 2 | 50.0 | 53 | 89.3 | 9 | 90.0 | 56 | 87.5 | 6 | 100.0 | ||

| Supplements intake | Yes | 34 | 51.5 | 3 | 75.0 | 29 | 49.2 | 7 | 70.0 | 32 | 50.0 | 5 | 83.3 | |

| No | 32 | 48.5 | 1 | 25.0 | 30 | 50.8 | 3 | 30.0 | 32 | 50.0 | 1 | 16.7 | ||

| Type of supplements | Iron | 21 | 61.8 | 3 | 100.0 | 18 | 62.1 | 4 | 57.1 | 22 | 68.8 | 1 | 20.0 | |

| Iron, folic acid, and vitamin B12, and/or multivitamins | 13 | 38.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 11 | 37.9 | 3 | 42.9 | 10 | 31.3 | 4 | 80.0 | ||

| Anthropometric characteristics | Weight percentile | Adequate weight for age (Percentile 3-97) | 26 | 86.7 | 3 | 100.0 | 24 | 85.7 | 4 | 100.0 | 27 | 87.1 | 2 | 100.0 |

| Not adequate for age [Percentile <3 (low weight for age) or Percentile >97 (high weight for age] | 4 | 13.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 14.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 12.9 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Health characteristics | Vomit or refusal to eat* | Yes (had vomited or refused to eat) | 11 | 16.7 | 1 | 25.0 | 10 | 16.9 | 1 | 10.0 | 11 | 17.2 | 1 | 16.7 |

| No | 55 | 83.3 | 3 | 75.0 | 49 | 83.1 | 9 | 90.0 | 53 | 82.8 | 5 | 83.3 | ||

| Presence of infection or inflammation by C reactive protein (CRP) level | Yes (CRP>5.0mg/mL) | 15 | 34.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 15 | 36.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 14 | 33.3 | 1 | 20.0 | |

| No (CRP<5.0mg/mL) | 28 | 65.1 | 3 | 100.0 | 26 | 63.4 | 6 | 100.0 | 28 | 66.7 | 4 | 80.0 | ||

| Glucose | Normal (60.0-180.0mg/dL) | 18 | 100.0 | - | - | 16 | 100.0 | 2 | 100.0 | 15 | 100.0 | 3 | 100.0 | |

| Bilirubin | Hyperbilirubinemia (Bilirubin>1.20mg/dL) | 1 | 9.1 | - | - | 1 | 11.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 25.0 | |

| Normal (0.30-1.20mg/dL) | 10 | 90.9 | - | - | 8 | 88.9 | 2 | 100.0 | 7 | 100.0 | 3 | 75.0 | ||

| Urea | Uremia (Blood urea >36.0mg/dL) | 5 | 14.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 9.4 | 2 | 50.0 | 5 | 15.6 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Normal (5.0-36.0mg/dL) | 30 | 85.7 | 1 | 100.0 | 29 | 90.6 | 2 | 50.0 | 27 | 84.4 | 4 | 100.0 | ||

| Had any hospitalization (in the past) | Yes | 23 | 35.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 20 | 34.5 | 3 | 30.0 | 18 | 28.6 | 5 | 83.3 | |

| No | 42 | 64.6 | 4 | 100.0 | 38 | 65.5 | 7 | 70.0 | 45 | 71.4 | 1 | 16.7 | ||

| Duration of hospitalization (in days) | Up to 5 days | 6 | 46.2 | - | - | 7 | 58.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 60.0 | 1 | 33.3 | |

| More than 5 days | 7 | 53.8 | - | - | 5 | 41.7 | 1 | 100.0 | 4 | 40.0 | 2 | 66.7 | ||

| Notes: | (*) Children whose mothers reported a history of food selectivity behavior (e.g., children who eat "normally" at kindergarten or school but refuse to eat the same foods at home), refusal to eat certain types of food (such as meat), or vomiting after consuming certain types of food (e.g., due to irritability or irritated behavior, abdominal pain, or an unspecified reason). | |||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).