Submitted:

03 December 2024

Posted:

04 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Study Population Characteristics

3.2. The Random Effect of Anemia

3.3. Determinants of Anemia Among Children Living in Mozambique

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Leung AK, C.; Lam, J.M.; Wong AH, C.; Hon, K.L.; Li, X. Iron Deficiency Anemia: An Updated Review. Current Pediatric Reviews 2024, 20, 339–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallagher, P.G. Anemia in the pediatric patient. Blood 2022, 140, 571–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Anaemia in women and children. WHO Global Anaemia estimates, 2021 Edition. Retrieved May 21, 2024. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/anaemia_in_women_and_children.

- Lozoff, B.; Beard, J.; Connor, J.; Barbara, F.; Georgieff, M.; Schallert, T. Long-lasting neural and behavioral effects of iron deficiency in infancy. Nutrition reviews 2006, 64(5 Pt 2), S34–S91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwetu, T.P.; Taylor, M.; Chhagan, M.; Kauchali, S.; Craib, M. Health and educational achievement of school-aged children: The impact of anaemia and iron status on learning. Health SA = SA Gesondheid 2019, 24, 1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuwabaine, L.; Kawuki, J.; Kamoga, L.; Sserwanja, Q.; Gatasi, G.; Donkor, E.; Mutisya, L.M.; Asiimwe, J.B. Factors associated with anaemia among pregnant women in Rwanda: an analysis of the Rwanda demographic and health survey of 2020. BMC pregnancy and childbirth 2024, 24, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daru, J. Sustainable Development Goals for anaemia: 20 years later, where are we now? The Lancet. Global health 2022, 10, e586–e587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weze, K.; Abioye, A.I.; Obiajunwa, C.; Omotayo, M. Spatio-temporal trends in anaemia among pregnant women, adolescents and preschool children in sub-Saharan Africa. Public health nutrition 2021, 24, 3648–3661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesema, G.A.; Worku, M.G.; Tessema, Z.T.; Teshale, A.B.; Alem, A.Z.; Yeshaw, Y.; Alamneh, T.S.; Liyew, A.M. Prevalence and determinants of severity levels of anemia among children aged 6-59 months in sub-Saharan Africa: A multilevel ordinal logistic regression analysis. PloS one 2021, 16, e0249978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmare, A.A.; Agmas, Y.A. Determinants of coexistence of undernutrition and anemia among under-five children in Rwanda; evidence from 2019/20 demographic health survey: Application of bivariate binary logistic regression model. PloS one 2024, 19, e0290111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akseer, N.; Al-Gashm, S.; Mehta, S.; Mokdad, A.; Bhutta, Z.A. Global and regional trends in the nutritional status of young people: a critical and neglected age group. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2017, 1393, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthi, M.; Shekar, M. Breastfeeding: A Key Investment in Human Capital. Pediatrics 2021, 147, e2020040824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, S.P.; Chen-Edinboro, L.P.; Caulfield, L.E.; Murray-Kolb, L.E. The impact of anemia on child mortality: an updated review. Nutrients 2014, 6, 5915–5932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Victora, C. G., Adair, L., Fall, C., Hallal, P. C., Martorell, R., Richter, L., Sachdev, H. S.,; Maternal and Child Undernutrition Study Group. Maternal and child undernutrition: consequences for adult health and human capital. Lancet 2008, 371, 340–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brabin, B.J.; Premji, Z.; Verhoeff, F. An analysis of anemia and child mortality. The Journal of Nutrition 2001, 131(2S-2), 636S–648S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muhajarine, N., Adeyinka, D. A., Matandalasse, M.,; Chicumbe, S. Inequities in childhood anaemia at provincial borders in Mozambique: Cross-sectional study results from multilevel Bayesian analysis of 2018 National Malaria Indicator Survey. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e051395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Bank. The World Bank in Mozambique: Overview. Retrieved May 2, 2024. 2024. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/mozambique/overview.

- United States Census Bureau. Mozambique: Population Vulnerability and Resilience Profile. Retrieved May 2, 2024. 2024. Available online: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/international-programs/data/population-vulnerability/mozambique.html.

- USAID. Mozambique: Nutrition Profile. Retrieved May 2, 2024. 2021. Available online: https://www.usaid.gov/document/mozambique-nutrition-profile.

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. (2020). World fertility and family planning 2020. Retrieved July 3, 2024, from https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/family/Ten_key_messages%20for%20WFFP2020_highlights.pdf.

- WHO Africa. (2024). Health Topics (Mozambique). Retrieved May 3, 2024, from https://www.afro.who.int/countries/mozambique/topic/health-topics-mozambique.

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE) & ICF. (2024). Inquérito Demográfico e de Saúde em Moçambique 2022–23. Maputo, Moçambique e Rockville, Maryland, EUA: INE e ICF. Retrieved May 20, 2024, from https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR389/FR389.pdf.

- Instituto Nacional de Saúde (INS) & ICF. (2019). Inquérito Nacional sobre Indicadores de Malária em Moçambique 2018. Maputo, Moçambique. Rockville, Maryland, EUA: INS e ICF. Retrieved May 3, 2024, from https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/MIS33/MIS33.pdf.

- Ministério da Saúde (MISAU), Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE), & ICF Internacional. (2016). Inquérito de Indicadores de Imunização, Malária e HIV/SIDA em Moçambique 2015. Retrieved May 3, 2024, from https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/ais12/ais12.pdf.

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE). (2011). Moçambique—Inquérito Demográfico e de Saúde 2011. Retrieved May 3, 2024, from https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/fr266/fr266.pdf.

- The World Bank. (2013). Demográfico e de Saúde 2011. Study description. Microdata Library. Retrieved May 3, 2024, from https://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/1563/study-description.

- The World Bank. (2018). Inquérito de Indicadores de Imunização, Malária e HIV/SIDA 2015 Study description. Microdata Library. Retrieved May 3, 2024, from https://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/2977#study_desc1674579234511.

- The World Bank. (2019). Inquérito Nacional sobre Indicadores de Malária 2018. Study description. Microdata Library. Retrieved May 3, 2024, from https://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/3488/study-description.

- The World Bank. (2024a). Inquérito Demográfico e de Saúde 2022-2023. Study description. Microdata Library. Retrieved May 3, 2024, from https://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/6247.

- Usanzineza, H.; Nsereko, E.; Niyitegeka, J.P.; Uwase, A.; Tuyishime, D.H.; Sunday, F.X.; Mazimpaka, C.; Ahishakiye, J. Prevalence and risk factors for childhood anemia in Rwanda: Using Rwandan demographic and health survey 2019–2020. Public Health Challenges 2024, 3, e159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, A.K.; Afful-Dadzie, E.; Marquis, G.S. Infant and young child feeding practices are associated with childhood anaemia and stunting in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Nutrition 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrichs, H.; Endris, B.S.; Dejene, T.; Dinant, G.J.; Spigt, M. Anaemia and its determinants among young children aged 6-23 months in Ethiopia (2005-2016). Maternal & child nutrition 2021, 17, e13082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.; Larijani, B.; Esmaillzadeh, A. Concurrent anemia and stunting in young children: Prevalence, dietary and non-dietary associated factors. Nutrition Journal 2019, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto-Patron, A.; Van der Horst, K.; Hutton, Z.V.; Detzel, P. Association between Anaemia in Children 6 to 23 Months Old and Child, Mother, Household and Feeding Indicators. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USAID. (2013). Conceptual frameworks for anemia. Retrieved May 27, 2024, from https://spring-nutrition.org/sites/default/files/events/multisectoral_anemia_meeting_diagrams.pdf.

- MOST, USAID Micronutrient Program. (2004). A strategic approach to anemia control programs. Arlington, VA: MOST, USAID Micronutrient Program.

- Owais, A.; Merritt, C.; Lee, C.; Bhutta, Z.A. Anemia among Women of Reproductive Age: An Overview of Global Burden, Trends, Determinants, and Drivers of Progress in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. (2011). Vmnis: Vitamin and mineral nutrition information system. Haemoglobin concentrations for the diagnosis of anaemia and assessment of severity. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. Retrieved May 20, 2024, from https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-NMH-NHD-MNM-11.1.

- Croft, T. N., Allen, C. K., Zachary, B. W., et al. (2023). Guide to DHS Statistics. Rockville, Maryland, USA: ICF. Retrieved from https://www.dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/DHSG1/Guide_to_DHS_Statistics_DHS-8.pdf.

- Wasswa, R.; Kananura, R.M.; Muhanguzi, H.; Waiswa, P. Spatial variation and attributable risk factors of anaemia among young children in Uganda: Evidence from a nationally representative survey. PLOS Global Public Health 2023, 3, e0001899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armah-Ansah, E.K. Determinants of anemia among women of childbearing age: analysis of the 2018 Mali demographic and health survey. Archives of Public Health = Archives Belges de Sante Publique 2023, 81, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Sanharawi, M.; Naudet, F. Comprendre la régression logistique [Understanding logistic regression]. Journal Francais d'Ophtalmologie 2013, 36, 710–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakum, M.N.; Atanga, F.D.; Ajong, A.B.; Eba Ze, L.E.; Shah, Z. Factors associated with full vaccination and zero vaccine dose in children aged 12-59 months in 6 health districts of Cameroon. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danaei, G.; Andrews, K.G.; Sudfeld, C.R.; Fink, G.; McCoy, D.C.; Peet, E.; Sania, A.; Smith Fawzi, M.C.; Ezzati, M.; Fawzi, W.W. Risk Factors for Childhood Stunting in 137 Developing Countries: A Comparative Risk Assessment Analysis at Global, Regional, and Country Levels. PLoS medicine 2016, 13, e1002164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- StataCorp. 2023. Stata Statistical Software: Release 18. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC.

- Hailu, B.A. Mapping, trends, and factors associated with anemia among children aged under 5 y in East Africa. Nutrition 2023, 116, 112202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahiledengle, B.; Mwanri, L.; Agho, K.E. Household environment associated with anaemia among children aged 6–59 months in Ethiopia: A multilevel analysis of Ethiopia demographic and health survey (2005–2016). BMC Public Health 2024, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, A.M.; Fawzi, W.; Hill, A.G. Anaemia among Egyptian Children between 2000 and 2005: trends and predictors. Maternal & Child Nutrition 2012, 8, 522–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semedo, R.M.; Santos, M.M.; Baião, M.R.; Luiz, R.R.; da Veiga, G.V. Prevalence of anaemia and associated factors among children below five years of age in Cape Verde, West Africa. Journal of Health, Population, and Nutrition 2014, 32, 646–657. [Google Scholar]

- Fançony, C.; Lavinha, J.; Brito, M.; Barros, H. Anemia in preschool children from Angola: a review of the evidence. Porto Biomedical Journal 2020, 5, e60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zavala, E.; Adler, S.; Wabyona, E.; Ahimbisibwe, M.; Doocy, S. Trends and determinants of anemia in children 6-59 months and women of reproductive age in Chad from 2016 to 2021. BMC Nutrition 2023, 9, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorne, C.J.; Roberts, L.M.; Edwards, D.R.; Haque, M.S.; Cumbassa, A.; Last, A.R. Anaemia and malnutrition in children aged 0-59 months on the Bijagós Archipelago, Guinea-Bissau, West Africa: a cross-sectional, population-based study. Paediatrics and International Child Health 2013, 33, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shenton, L.M.; Jones, A.D.; Wilson, M.L. Factors associated with anemia status among children aged 6–59 months in Ghana 2020, 2003–2014. Maternal and Child Health Journal 24, 483–502. [CrossRef]

- Gebreegziabher, T.; Sidibe, S. Prevalence and contributing factors of anaemia among children aged 6-24 months and 25-59 months in Mali. Journal of Nutritional Science 2023, 12, e112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeagu, E.I.; Obeagu, G.U. Tackling childhood anemia in malaria zones: Comprehensive strategies, challenges, and future directions. Academia Medicine 2024, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Nutrition Report (GNR). (2024). Mozambique: The burden of malnutrition at a glance. Retrieved May 20, 2024, from https://globalnutritionreport.org/resources/nutrition-profiles/africa/eastern-africa/mozambique/.

- World Health Organization. (2019). Nutrition landscape information system (Nlis): Anaemia. Nutrition and nutrition-related health and development data. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. Retrieved May 20, 2024, from https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/332223/9789241516952-eng.pdf?sequence=1.

- Maulide Cane, R.; Keita, Y.; Lambo, L.; Pambo, E.; Gonçalves, M.P.; Varandas, L.; Craveiro, I. Prevalence and factors related to anaemia in children aged 6–59 months attending a quaternary health facility in Maputo, Mozambique. Global Public Health 2023, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavaleta, N.; Astete-Robilliard, L. Efecto de la anemia en el desarrollo infantil: consecuencias a largo plazo [Effect of anemia on child development: long-term consequences]. Revista Peruana de Medicina Experimental y Salud Publica 2017, 34, 716–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engidaye, G., Melku, M., Yalew, A.,; et al. Under nutrition, maternal anemia and household food insecurity are risk factors of anemia among preschool aged children in Menz Gera Midir district, Eastern Amhara, Ethiopia: A community based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, K.K.; Vijay, J.; Mangal, A.; Mangal, D.K.; Gupta, S.D. Burden of anaemia among children aged 6–59 months and its associated risk factors in India – Are there gender differences? Children and Youth Services Review 2021, 122, 10591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J., Wu, H., Zhao, M., Magnussen, C. G.,; Xi, B. Prevalence and changes of anemia among young children and women in 47 low- and middle-income countries, 2000-2018. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 41, 101136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agho, K.E.; Chitekwe, S.; Rijal, S.; Paudyal, N.; Sahani, S.K.; Akombi-Inyang, B.J. Association between child nutritional anthropometric indices and iron deficiencies among children aged 6–59 months in Nepal. Nutrients 2024, 16, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alamneh, T.S.; Melesse, A.W.; Gelaye, K.A. Determinants of anemia severity levels among children aged 6-59 months in Ethiopia: Multilevel Bayesian statistical approach. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 4147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira M de LP, D.; Lira PI, C.; Coutinho, S.B.; Eickmann, S.H.; Lima M de, C. Influence of breastfeeding type and maternal anemia on hemoglobin concentration in 6-month-old infants. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2010, 86, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeeshan, F.; Bari, A.; Farhan, S.; Jabeen, U.; Rathore, A.W. Correlation between maternal and childhood VitB12, folic acid and ferritin levels. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences 2017, 33, 162–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, R.d.e.F.; Taddei, J.A.; Konstantyner, T.; Marques, A.C.; Braga, J.A. Correlation between hemoglobin levels of mothers and children on exclusive breastfeeding in the first six months of life. Jornal de Pediatria 2016, 92, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miniello, V.L.; Verga, M.C.; Miniello, A.; Di Mauro, C.; Diaferio, L.; Francavilla, R. Complementary feeding and iron status: "The unbearable lightness of being" infants. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutonhodza, B.; Dembedza, M.P.; Lark, M.R.; Joy EJ, M.; Manzeke-Kangara, M.G.; Njovo, H.; Nyadzayo, T.K.; Kalimbira, A.A.; Bailey, E.H.; Broadley, M.R.; Matsungo, T.M.; Chopera, P. Anemia in children aged 6-59 months was significantly associated with maternal anemia status in rural Zimbabwe. Food Science & Nutrition 2022, 11, 1232–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maulide Cane, R., Sheffel, A., Salomão, C.,; et al. Structural readiness of health facilities in Mozambique: How is Mozambique positioned to deliver nutrition-specific interventions to women and children? Journal of Global Health Reports 2023, 7, e2023074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaro, M. Accelerating progress in micronutrient deficiencies in Mozambique: A Ministry of Health perspective. Maternal & Child Nutrition 2019, 15 Suppl 1, e12707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2024). Strengthening primary health care with a community health strategy in Mozambique. World Health Organization. Retrieved September 13, 2024, from https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/strengthening-primary-health-care-with-a-community-health-strategy-in-mozambique.

- Van Weel, C.; Kidd, M.R. Why strengthening primary health care is essential to achieving universal health coverage. Canadian Medical Association Journal = Journal de l'Association Medicale Canadienne 2018, 190, E463–E466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebrehaweria Gebremeskel, M.; Lemma Tirore, L. Factors Associated with Anemia Among Children 6-23 Months of Age in Ethiopia: A Multilevel Analysis of Data from the 2016 Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey. Pediatric Health, Medicine and Therapeutics 2020, 11, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tegegne, M.; Abate, K.H.; Belachew, T. Anaemia and associated factors among children aged 6-23 months in agrarian community of Bale zone: a cross-sectional study. Journal of Nutritional Science 2022, 11, e96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harding, K.B.; Neufeld, L.M. Iron deficiency and anemia control for infants and young children in malaria-endemic areas: a call to action and consensus among the research community. Advances in Nutrition 2012, 3, 551–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, C.; Leets, I.; Puche, R.; Anzola, E.; Montilla, R.; Parra, C.; Aguilera, A.; García-Casal, M.N. A single dose of vitamin A improves haemoglobin concentration, retinol status and phagocytic function of neutrophils in preschool children. The British Journal of Nutrition 2010, 103, 798–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva AD, P.; Pereira AD, S.; Simões BF, T.; Omena, J.; Cople-Rodrigues CD, S.; De Castro IR, R.; Citelli, M. Association of vitamin A with anemia and serum hepcidin levels in children aged 6 to 59 mo. Nutrition 2021, 91-92, 111463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imdad, A.; Mayo-Wilson, E.; Haykal, M.R.; Regan, A.; Sidhu, J.; Smith, A.; Bhutta, Z.A. Vitamin A supplementation for preventing morbidity and mortality in children from six months to five years of age. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2022, 3, CD008524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semba, R.D.; de Pee, S.; Ricks, M.O.; Sari, M.; Bloem, M.W. Diarrhea and fever as risk factors for anemia among children under age five living in urban slum areas of Indonesia. International Journal of Infectious Diseases : IJID : official publication of the International Society for Infectious Diseases 2008, 12, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INS, MISAU, & UNICEF. (2022). Relatório sobre avaliação da suplementação com vitamina A nos cuidados de saúde primários nas províncias de Sofala, Manica, Tete, Zambézia e Nampula (ASUVA) - Uma avaliação da implementação, Retrieved May 28, 2024, from https://drive.google.com/file/d/16LDjk_u4TWx9nX3MonjU8rjpK-omlKhy/view.

- Kothari, M.T.; Coile, A.; Huestis, A.; Pullum, T.; Garrett, D.; Engmann, C. Exploring associations between water, sanitation, and anemia through 47 nationally representative demographic and health surveys. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2019, 1450, 249–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xiao, J.; Liao, M.; Huang, G.; Zheng, J.; Wang, H.; Huang, Q.; Wang, A. Anemia prevalence, severity and associated factors among children aged 6-71 months in rural Hunan Province, China: a community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barletta, G.; Castigo, F.; Egger, E.M.; Keller, M.; Salvucci, V.; Tarp, F. The impact of COVID-19 on consumption poverty in Mozambique. Journal of International Development 2022, 34, 771–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvucci, V.; Tarp, F. Poverty and vulnerability in Mozambique: An analysis of dynamics and correlates in light of the Covid-19 crisis using synthetic panels. Review of Development Economics 2021, 25, 1895–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierce, H.; Foster, K. Health and well-being outcomes of women and children in Sub-Saharan Africa: Examining the role of formal schooling, literacy, and health knowledge. International Journal of Educational Development 2020, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldi, A.J.; Clucas, D.; Pasricha, S.R. Anemia and water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH)—is there really a link? American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2020, 112, 1145–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bountogo, M., Ouattara, M., Sié, A., Compaoré, G., Dah, C., Boudo, V., Zakane, A., Lebas, E., Brogdon, J. M., Godwin, W. W., Lin, Y., Arnold, B. F., Oldenburg, C. E.,; Étude CHAT Group. Access to Improved Sanitation and Nutritional Status among Preschool Children in Nouna District, Burkina Faso. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2021, 104, 1540–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arntson, L.; McLaughlin, K.R.; Smit, E. Factors influencing fever care-seeking for children under five years of age in The Gambia: a secondary analysis of 2019-20 DHS data. Malaria Journal 2024, 23, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Random effect | Model 1 (Empty) | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 |

| Regional level variance (SE) | 0.20(0.08) | 0.16(0.05) | 0.20(0.08) | 0.08(0.03) | 0.09(0.03) |

| Region > Community level variance (SE) | 0.44(0.15) | 0.50(0.17) | 0.46(0.16) | 0.41(0.14) | 0.47(0.16) |

| Regional ICC(%) | 5.1 | 4.1 | 5.0 | 2.1 | 2.4 |

| Community | Region ICC(%) | 16.4 | 16.7 | 16.6 | 12.9 | 14.7 |

| Model fit statistics | |||||

| Log likelihood | -4,675 | -4,436 | -4,659 | -4,591 | -4,402 |

| AIC | 9,355 | 8,891 | 9,332 | 9,203 | 8,824 |

| Notes: | SE: standard error. ICC: intra-cluster correlation coefficient. AIC: Akaike Information Criterion | ||||

| Variable | Model 1 (Empty) |

Model 2 aOR[95%CI] |

Model 3 aOR[95%CI] |

Model 4 aOR[95%CI] |

Model 5 aOR[95%CI] |

| Age of the woman | 0.99[0.98,1.01] | 0.99[0.98,1.01] | |||

| Education level | |||||

| No education† | 1.00[1.00,1.00] | 1.00[1.00,1.00] | |||

| Primary | 0.96[0.82,1.12] | 1.03[0.87,1.21] | |||

| Secondary/Higher | 0.64[0.50,0.82]** | 0.83[0.58,1.18] | |||

| At least 4 ANC visits | |||||

| less than 4 visits† | 1.00[1.00,1.00] | ||||

| 4+ visits | 0.97[0.78,1.22] | 0.99[0.79,1.26] | |||

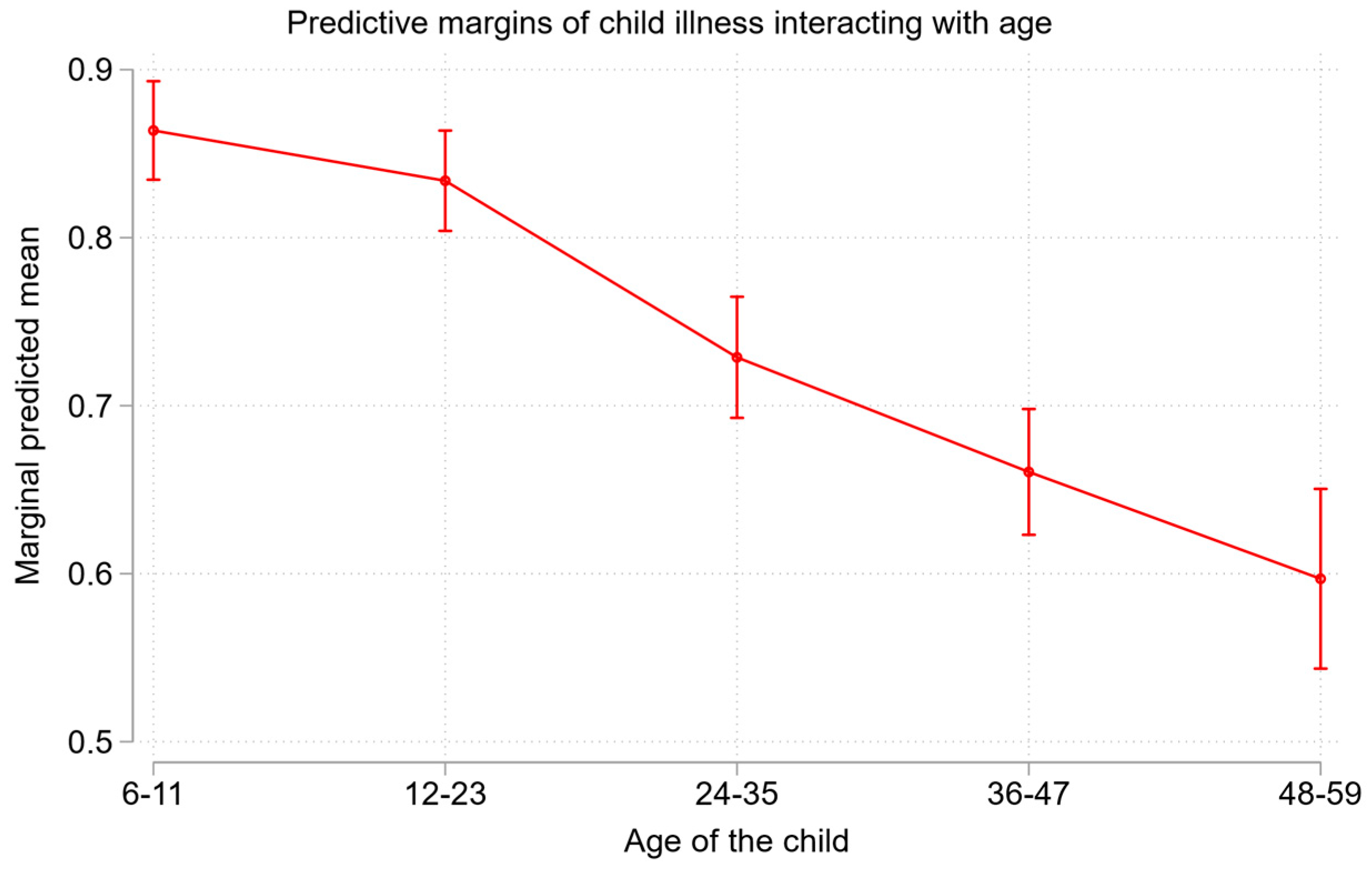

| Child´s age (in months) | |||||

| 6-11† | 1.00[1.00,1.00] | 1.00 | |||

| 12-23 | 0.75[0.59,0.96]* | 0.77[0.62,0.97]* | |||

| 24-35 | 0.40[0.32,0.50]** | 0.38[0.29,0.50]** | |||

| 36-47 | 0.28[0.25,0.33]** | 0.27[0.22,0.32]** | |||

| 48-59 | 0.20[0.17,0.24]** | 0.19[0.16,0.24]** | |||

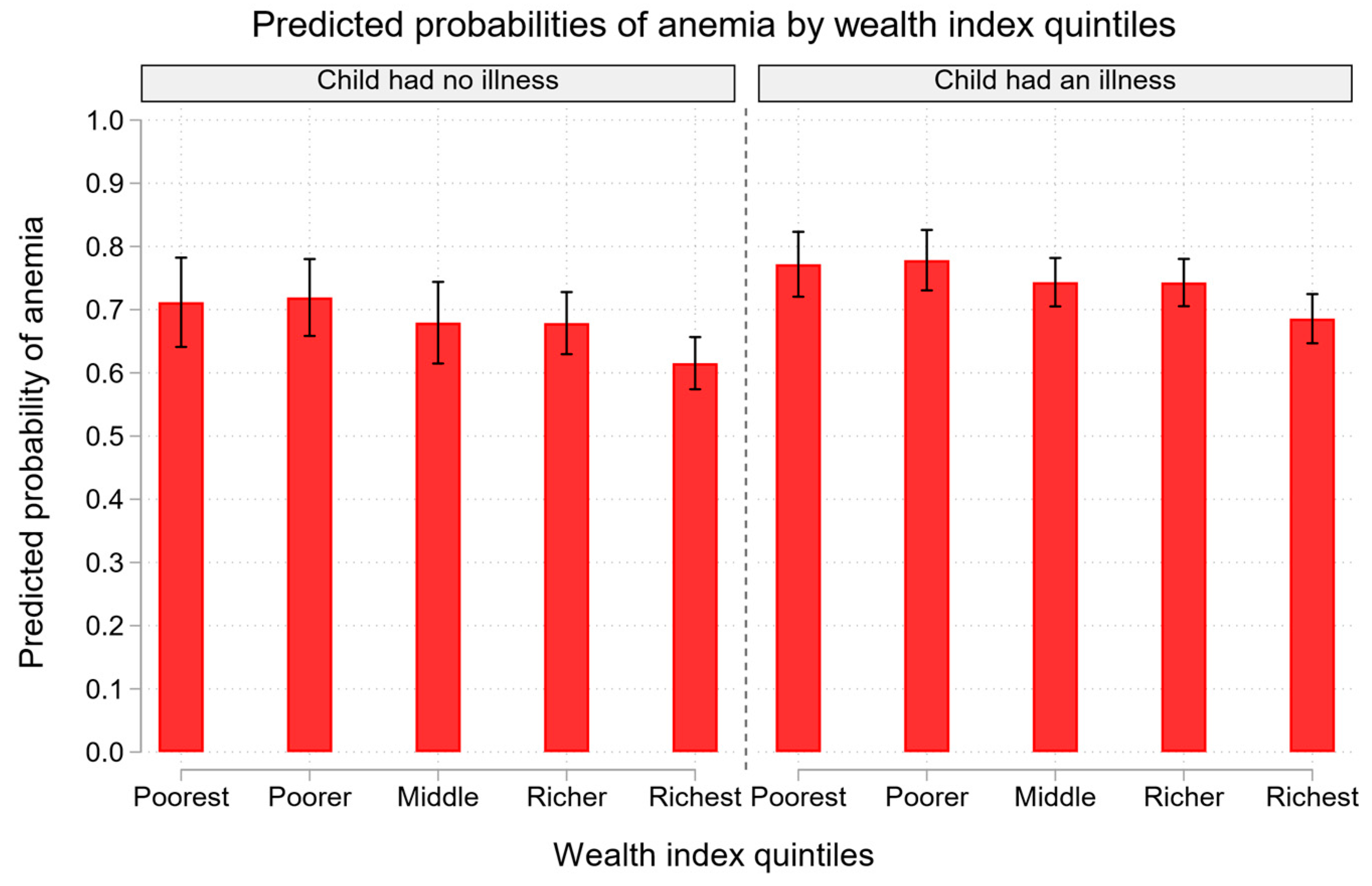

| Child illness | |||||

| No† | 1.00[1.00,1.00] | 1.00[1.00,1.00] | |||

| Yes | 1.41[1.14,1.73]** | 1.42[1.15,1.74]** | |||

| Children aged 6-59 months given Vit. A supplement | |||||

| No† | 1.00[1.00,1.00] | 1.00[1.00,1.00] | |||

| Yes | 0.74[0.61,0.91]** | 0.76[0.63,0.93]** | |||

| Feeding characteristics | |||||

| Group 1 (cereals, roots, and tubers) | 1.24[1.01,1.54]* | 0.78[0.58,1.04] | |||

| Group 2 (Legumes and nuts) | 1.16[1.02,1.31]* | 1.10[0.94,1.28] | |||

| Group 4 (Flesh foods (meat, fish, fowl, liver, or other organs and eggs) | 1.05[0.85,1.30] | 1.08[0.83,1.40] | |||

| Group5 (Fruits and vegetables) | 1.01[0.87,1.17] | 0.99[0.87,1.13] | |||

| Wealth index | |||||

| Poorest† | 1.00[1.00,1.00] | 1.00[1.00,1.00] | |||

| Poorer | 1.03[0.88,1.20] | 1.04[0.87,1.25] | |||

| Middle | 0.81[0.65,1.01] | 0.84[0.68,1.05] | |||

| Richer | 0.78[0.63,0.97]* | 0.84[0.68,1.04] | |||

| Richest | 0.56[0.40,0.79]** | 0.62[0.41,0.93]* | |||

| Sex of household head | |||||

| Male† | 1.00[1.00,1.00] | 1.00[1.00,1.00] | |||

| Female | 1.10[0.96,1.26] | 1.13[0.99,1.29] | |||

| Source of drinking water | |||||

| Improved† | 1.00[1.00,1.00] | 1.00[1.00,1.00] | |||

| Unimproved | 1.30[1.13,1.49]** | 1.32[1.11,1.57]** | |||

| Type of toilet facility | |||||

| Improved† | 1.00[1.00,1.00] | 1.00[1.00,1.00] | |||

| Not improved | 0.98[0.74,1.30] | 0.98[0.74,1.29] | |||

| Residence area | |||||

| Urban† | 1.00[1.00,1.00] | 1.00[1.00,1.00] | |||

| Rural | 1.10[0.93,1.31] | 1.10[0.91,1.32] | |||

| Notes: | † is a Reference category; aOR is the adjusted odds ratio; SE is the standard error; ICC is the inter-cluster correlation coefficient; AIC is the Akaike Information Criterion; 95% CI is the Confidence Interval; * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01; the assessment was based on multivariate three-level logistic regression model. | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).