Background/Objectives: Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a complex clinical condition characterized by the coexistence of interrelated metabolic abnormalities that significantly increase the risk of cardiovascular diseases and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Endocan, an endothelial cell-specific molecule, is considered a biomarker of endothelial dysfunction and inflammation. This study aimed to evaluate the relationship between serum endocan levels and the severity of MetS, assessed using the MetS-Z score.

Methods: In this study, 120 patients with MetS and 50 healthy controls were included. MetS was diagnosed according to the NCEP-ATP III criteria. The MetS-Z scores were calculated using the "MetS Severity Calculator" (

https://metscalc.org). Serum levels of Endocan, sICAM-1, and sVCAM-1 were measured by ELISA method.

Results: Serum levels of endocan, sICAM-1, and sVCAM-1 were significantly higher in the MetS group compared to the control group (all p< 0.001). When the MetS group was divided into tertiles based on MetS-Z scores, a stepwise and statistically significant increase was observed in the levels of endocan and other endothelial markers from the lowest to the highest tertile (p< 0.0001). Correlation analysis revealed a strong positive association between the MetS-Z score and serum endocan levels (r=0.584, p< 0.0001). ROC curve analysis showed that endocan had high diagnostic accuracy for identifying MetS (AUC=0.967, p< 0.0001), with a cutoff value of >88.0 ng/L.

Conclusion: Circulating levels of Endocan were significantly increased in MetS and also were associated with the severity of MetS, suggesting that the levels of endocan may be a potential role of the cellular response to endothelial dysfunction injury in patients with MetS.

1. Introduction

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a health condition characterized by a combination of metabolic disorders such as insulin resistance, hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and obesity. This condition causes the formation of cardiometabolic risk factors characterized by prothrombotic and proinflammatory states, which predisposes to the development of type 2 diabetes (DM) and atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases (ASCVD) [1]. Furthermore, it has been shown that this pathological condition continues to grow with prevalences ranging from 27.4% to 39.0% in the last two decades [1,2]. Researchers investigating MetS encountered challenges in delivering precise risk assessments for individuals with MetS, prompting the creation of a new MetS severity z score (MetS-Z) for additional research. The MetS-Z was derived from validated equations established through clinical trials, utilizing body mass index (BMI), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL), systolic blood pressure (SBP), triglycerides (TG), and fasting blood glucose (FBG). Studies indicate that MetS-Z may correlate with diabetes and coronary heart disease, thereby offering supplementary predictive risk for these conditions [3]. Endothelial dysfunction, platelet hyperactivity, oxidative stress, and low-grade inflammation are some of the factors that cause this disorder to negatively affect the vascular wall. Increased vasoconstriction and atherosclerosis result from the activation of these processes, which eventually encourage a prothrombotic condition [4]. According to clinical research, the development of atherosclerotic vascular disorders is significantly influenced by endothelial dysfunction, hyperlipidemia, oxidative stress, and platelet hyperactivity (2). All of the factors that contribute to MetS negatively impact the endothelium. Endothelial dysfunction may raise the risk of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes in addition to contributing to the pathophysiology of atherosclerosis [4,5].

Dyslipidemia (high blood triglyceride and cholesterol levels) is an important risk factor for the development of atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases (CVD) [6]. It is suggested that the presence of increased and prolonged atherogenic chylomicron remnants, decreased HDL levels, and activation of leukocytes and endothelial cells due to the effect of remnants are effective in the predisposition of individuals with MetS to atherosclerosis [6,7]. Increased dyslipidemia in MetS has been demonstrated to activate leukocytes, which in turn increases oxidative stress and proinflammatory cytokines, which lead to endothelial dysfunction [7]. Vascular endothelial cells play a fundamental role in events such as inflammation, hemostasis, angiogenesis, and tumor invasion with many secreted mediators and receptor/ligand interactions [8]. Endothelial-specific molecule 1 (Endocan), which is expressed in endothelial cells in response to inflammatory cytokines, is stated to be an important predictor of vascular events. Endocan is a proteoglycan secreted by the endothelium and increased tissue expression is an indicator of endothelial activation, inflammation, and neovascularization [9]. Endocan has been observed to interact with other molecules at various stages of cell adhesion, migration, proliferation and differentiation [10].

Understanding the relationship between endothelial dysfunction markers such as Endokan and metabolic syndrome using the metabolic syndrome severity score may provide valuable contributions to combating this syndrome, which is considered an important independent risk factor for cardiovascular events. To the literature, there are no studies investigating the serum endocan levels in MetS and/or the relationship of endocan with the disease severity of MetS. Therefore, the present study tested the hypothesis that changes in the circulating concentrations of Endocan and endothelial factors might occur in MetS according to their disparate MetS-Z score. Another aim of the study was to evaluate the change and relationship of circulating levels of Endocan, endothelial and inflammatory factors according to endothelial dysfunctions observed in MetS-Z score subgroups.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

This cross-sectional study comprised 120 participants with metabolic syndrome and 50 healthy controls admitted to our Family Medicine and Internal Medicine outpatient clinics. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki principles and received approval from the ethics review committee of the University of Health Sciences Trabzon Medicine Faculty Ethical Committee for Scientific Research on Humans (Reference number: 2024/93; Approval Date: 23/07/2024). Informed written consent was acquired from all patients before their enrollment in the trial.

The exclusion criteria included the presence of cardiac and systemic conditions: ischemic heart disease, congenital heart defects, valvular heart disease, neoplastic disorders, inflammatory diseases, and infectious diseases.

Participants were excluded if they were on any medication that could potentially interfere with the measurement of endocan and endothelial dysfunction, including treatments known to affect lipid and lipoprotein levels (e.g., angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and statins), oral antidiabetic medications, or insulin; if they had a serious medical condition such as chronic kidney disease or hepatic failure; a history of gastric or intestinal surgery or inflammatory bowel disease; or if they were alcohol abusers, smokers, using any dietary supplements, or were pregnant or lactating.

The diagnostic criteria for metabolic syndrome were those endorsed by the National Cholesterol Education Program. The Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults – Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP-ATP III) is characterized by the presence of a minimum of three of the following components: 1) augmented waist circumference (> 102 cm for males, > 88 cm for females); 2) elevated triglycerides (≥ 150 mg/dL) or utilization of triglyceride-lowering medications; 3) diminished HDL cholesterol (< 40 mg/dL in males, < 50 mg/dL in females); 4) hypertension (≥ 130/ ≥ 85 mm Hg) or administration of antihypertensive medications; and 5) fasting glucose (≥ 100 mg/dl) or use of antidiabetic medications [11].

2.2. Assessment of MetS Severity Z Score (MetS-Z Score)

The Metabolic Syndrome Severity Score (MetS-S), derived from BMI, was utilized to assess the risk of MetS in the present study. The MetS-S calculation was conducted utilizing the online resource "MetS Severity Calculator" available at

https://metscalc.org/. MetS Calc, the MetS-S calculator, is an online tool that computes an individual's MetS-S score utilizing proven and thoroughly researched equations. MetS Calc was created by Dr. Matthew J. Gurka from the University of Florida and Dr. Mark DeBoer from the University of Virginia under CTS-IT. The formulas for calculating MetS-S are derived from the the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES )study in the USA, incorporating factors such as age, race, gender, BMI, triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), systolic blood pressure (SBP), and blood glucose levels. The MetS-Severity Score was computed in two forms: MetS-S zero (MetS-Sz), which spans from negative infinity to positive infinity [12,13].

2.3. Physical and Laboratory Assessments

Anthropometric measurements (weight, height, waist circumference) and systemic blood pressure readings were obtained via physical examination in accordance with standard protocols. The body mass index (BMI) is calculated by calculating weight (kg) by height squared (m²) [14]. Waist circumferences were measured in the horizontal plane at the halfway between the smallest rib and the iliac crest [15]. Resting systolic and diastolic blood pressure was measured three times at one-minute intervals using a standard mercury sphygmomanometer after a five-minute rest period. The average of the second and third readings was employed in the analysis. Venous blood samples were collected in the morning after a minimum fasting period of 8 hours. Serum cholesterol, triglycerides, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) were measured using enzymatic colorimetric techniques with commercially available kits (COBAS 311, Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) was quantified using the COBAS 311 analyzer by the particle-enhanced immunoturbidimetric method. Serum glucose concentrations were measured enzymatically using the hexokinase method (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). The blood HbA1c level was assessed with a COBAS 311 analyzer through the particle-enhanced immunoturbidimetric method.

2.4. The Serum Endocan and Soluble Cell Adhesion Molecules (sCAMs) ICAM-1, VCAM-1 Concentrations Measurement

Endocan, sICAM-1 and sVCAM-1 were quantified using a sandwich enzyme immunoassay ELISA kit (Bioassay Biotechnology Laboratory, Cat No: E3160Hu, Cat No: E0203Hu and Cat No: E0212Hu, Shangai, China). The absorbance of the samples was quantified at 450 nm utilizing a spectrophotometer equipped with a microplate reader (VERSA max, Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA). The intra-assay coefficients of variation for the endothelium parameters in these tests were 5.13%, 6.24% and 6.03%, respectively. Endocan, and sVCAM-1 results were quantified in ng/L, whereas the sICAM-1 result was quantified in ng/mL.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The results were analyzed utilizing IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (version 23.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The Shapiro-Wilk test was employed to evaluate the distribution of variables. Normally distributed data were represented as mean ± standard deviation, while non-normally distributed variables were represented as median (interquartile range, IQR). The Student's t-test was utilized for comparing two groups with normal distribution, whereas the Mann-Whitney U test was employed for two groups with non-normal distribution. Each MetS group was divided into three equal subgroups according to tertiles of MetS-Z score values and evaluated using the Kruskal-Wallis test. Participants with low MetS-Z scores were assigned to Group 1, those with intermediate scores to Group 2, and those with high scores to Group 3. Analyses were conducted using MedCalc Statistical Software version 19.1 (Medcalc software BVBA, Belgium), and results were assessed by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. Moreover, the "Spearman" test was employed to correlate variables that do not conform to a normal distribution, whereas the "Pearson" test was utilized to analyze the correlation between variables that adhere to a normal distribution. The sample size was determined utilizing G*Power Software 3.1 (Heinrich-Heine University, Düsseldorf, Germany). To identify a significant difference between the groups based on endocan levels with a moderate effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.8), the minimum sample size of 38 individuals was necessary for both the control and MetS groups (α = 0.05, 1-β = 0.80). Statistical significance was evaluated at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Information of the Research Cohorts

The fundamental features, fasting lipid profile, glucose, and insulin levels of the study groups participating in the research are encapsulated in Table 1. No notable variation in gender was detected between the MetS and control groups (p = 0.206) (Table 1). Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics, fasting lipid profiles, and glucose and insulin levels of the control and MetS groups. The TG, TC, and LDL-C levels in the MetS group were considerably elevated compared to the control groups (p = 0.0001, respectively, Table 1). Marked disparities in endothelial parameters were noted between the MetS and Control groups (Table 1). The levels of Endocan, sICAM-1, and sVCAM-1 in the MetS group were significantly elevated compared to the control group (p = 0.0001, 0.003, 0.001, respectively), as shown in Table 2. The MetS group had markedly elevated Endocan levels in comparison to the control group (p = 0.0001). MetS-Z scores exhibited a progressive elevation from the Control group to the MetS group (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparisons of the values expressed in the study groups.

Table 1.

Comparisons of the values expressed in the study groups.

| Parametreler |

Control

n:50 |

MetS

n:120 |

P |

| Gender (F/M) |

22/28 |

53/67 |

0.201 |

| Age (years) |

42.0±6.76 |

45.6±8.42 |

0.586 |

| BMI (kg/m2) |

23.8±2.68 |

29.3±4.75 |

0.001 |

| WHR |

0.782±0.061 |

0.835±0.086 |

0.022 |

| WHtR |

0.415±0.037 |

0.528±0.057 |

0.001 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) |

89±2.15 |

112±3.28 |

0.002 |

| Insulin (μIU/mL) |

8.21 [6.58-9.81] |

10.5 [8.96-13.7] |

0.006* |

| HOMA-IR |

1.52 [0.918-2.53] |

2.38 [1.14-3.81] |

0.019* |

| TG (mg/dL) |

95.0 [71-128] |

188 [167-221] |

0.0001* |

| TC (mg/dL) |

172 [159-188] |

241 [220-269] |

0.0001* |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) |

59 [48-65] |

48 [37-56] ᵃ |

0.025* |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) |

50.0 [43.0-60.0] |

53 [47-59] |

0.0001* |

| SBP (mmHg) |

110 [105-120] |

120 [110-130] ᵃ |

0.028* |

| DBP (mmHg) |

70 [70-80] |

80 [70-85] |

0.258* |

| MetS-Z Score |

-3.41 [-4.41-(-2.88)] |

2.16 [1.88-3.64] |

0.0001* |

The MetS cohort was categorized into three groups according to median MetS-Z scores. Upon analyzing Endocan levels across the tertiles of MetS-z scores, group 3 exhibited the highest levels, which were considerably elevated compared to groups 1 and 2 (p = 0.0001) (Table 2). The levels of sICAM-1 and sVCAM-1 in group 3 were considerably elevated compared to groups 1 and 2 (p = 0.0001) (Table 2). Upon examination of additional endothelial components, the levels of sICAM-1 and sVCAM-1 in group 3 were found to be almost doubled compared to group 1, with statistical significance (p = 0.0001) (Table 2). The endothelial factors level in the MetS severity groups was significantly elevated, roughly doubling in group 3 compared to group 1 (p = 0.0001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Serum levels of endothelial factors in control, MetS and MetS-Z Scores Tertiles.

Table 2.

Serum levels of endothelial factors in control, MetS and MetS-Z Scores Tertiles.

| |

Main Groups |

|

Sub Groups |

|

| |

|

|

|

MetS-Z Scores Tertiles |

|

| |

Control

(n:50) |

MetS

(n:120) |

P |

1

(n:40)

1.18 [0.952-1.26] |

2

(n:40)

1.75 [1.40-2.01] |

3

(n:40)

2.21 [2.09-3.50] |

P |

| Endothelial factors |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Endocan, ng/L |

68.8 (58.0-75.8) |

150 (86.4-176) |

0.0001 |

98.2 (83.0-105) |

125 (112-132)a

|

168 (147-198)a, b

|

0.0001* |

| sICAM-1, ng/mL |

157 (128-169) |

327 (211-810) |

0.003 |

188 (179-253) |

262 (307-510)a,b

|

586 (447-745)a, b

|

0.0001* |

| sVCAM-1, ng/mL |

7.24 (5.11-9.45) |

17.1 (12.1-25.9) |

0.001 |

10.0 (9.11-12.6) |

18.1 (16.1-20.0)a,b

|

29.9 (22.3-41.5)a,b

|

0.0001* |

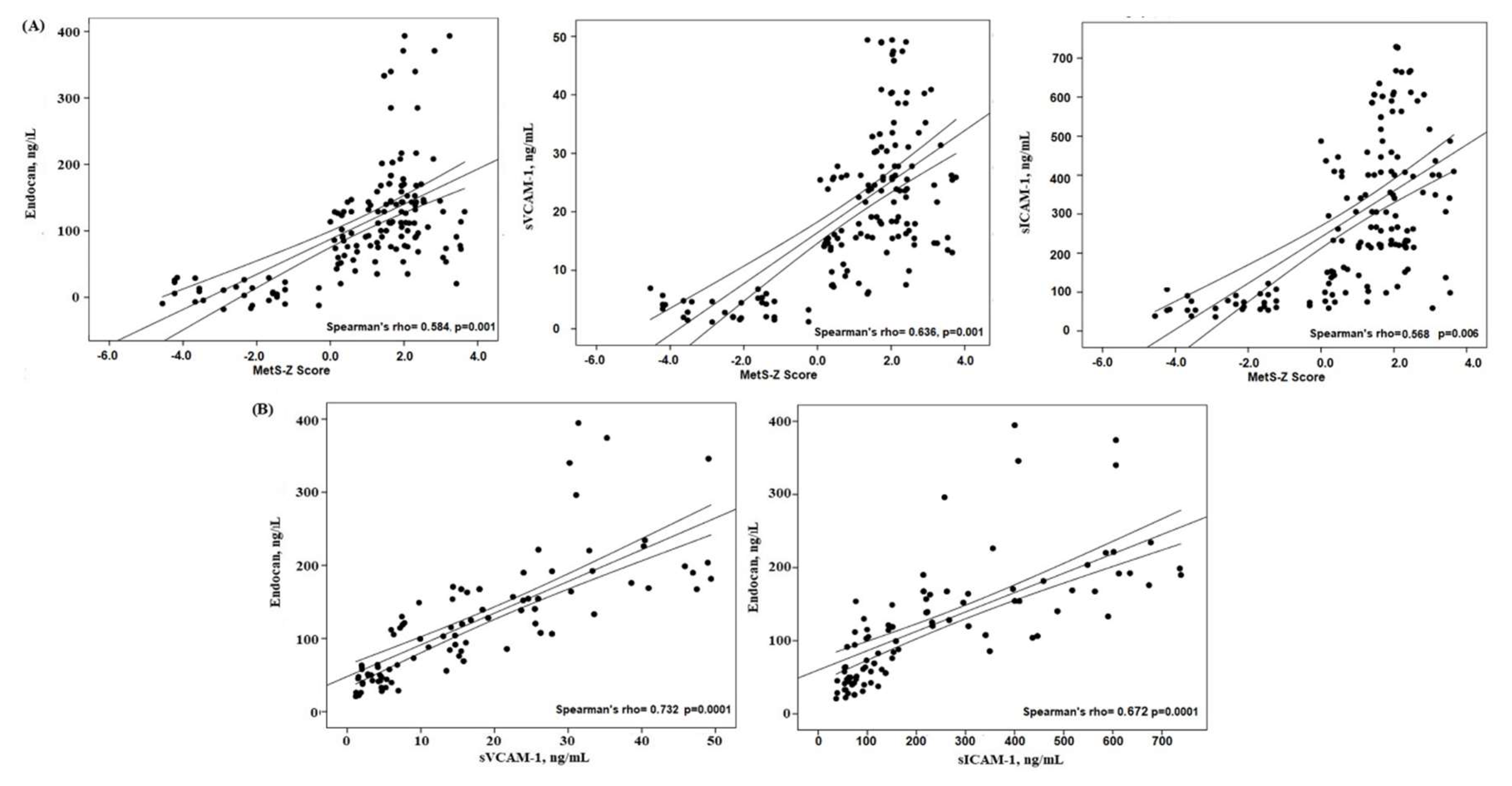

3.2. Correlation Between Ox-LDL, SCORE2 and Other Parameters

To enhance comprehension of the relationships between the MetS-z score and Edocan, along with other endothelium variables, Spearman's coefficient correlations were conducted. The MetS-z score shown a substantial positive connection with Endocan and endothelial variables (Figure 1). Figure 1 illustrates a robust positive association between the MetS-z Score and Endocan (r= 0.584, p = 0.0001). The level of endocan exhibited a positive correlation with other endothelial factors (sICAM-1, sVCAM-1, VEGFA) (p = 0.001, respectively).

Figure 1.

The correlation between (A) MetS-Z Score and Endothelial factors (B) Endocan and Endothelial factors in the study groups.

Figure 1.

The correlation between (A) MetS-Z Score and Endothelial factors (B) Endocan and Endothelial factors in the study groups.

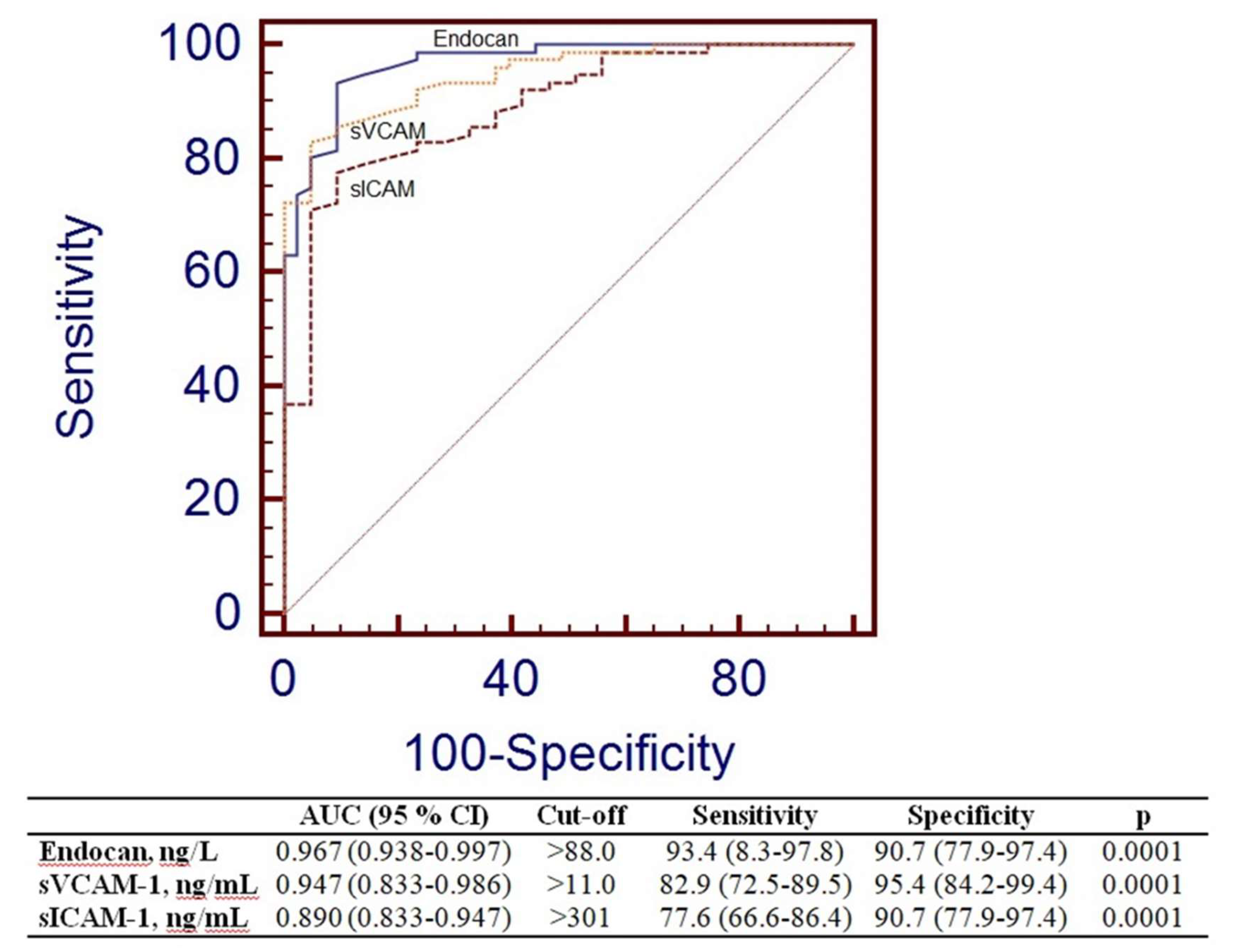

3.3. Receiver-Operating Characteristic Analyses

To assess the efficacy of Endocan and other endothelial variables in differentiating the control group from the MetS group. Figure 2 displays the data for Area Under the Curve (AUC), sensitivity, and specificity. Endocan exhibited markedly elevated AUC values (AUC=0.967, p=0.0001). The threshold for Endocan was more than 88.0 ng/L.

Figure 2.

Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis of Endocan, sVCAM-1 and sICAM-1.

Figure 2.

Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis of Endocan, sVCAM-1 and sICAM-1.

4. Discussion

The main results of this study in the MetS group and the tertile MetS Severity-Z score group are as follows: a) serum endocan levels were significantly elevated, approximately two fold (Table 2); b) additional endothelial factors (sICAM-1 and sVCAM-1) also exhibited significant increases and had a significant association with endocan levels in the study groups (Table 2 and Figure 1).

Recent studies have shown that endocan levels are increased in many diseases, especially in people with coronary artery disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obesity and chronic kidney disease. [16–19]. Studies established that serum endocan levels were markedly elevated in individuals with acute coronary syndrome relative to the control group [20,21]. Previous studies have shown that increasing MetS severity is associated with atherosclerosis and that blood endocan levels are significantly and consistently higher in patients with coronary artery disease [19,20,22]. On the other hand, our study is the first to investigate serum endocan in metabolic syndrome patients in association with MetS-Z score. Therefore, the present study examined endocan levels in MetS concerning tertile values established by the MetS severity-Z score. Consequently, the MetS-Z score was divided into tertiles to more effectively assess the correlation between MetS and endothelial dysfunction within the MetS group. In the aforementioned research, serum endocan levels were observed to be comparable to our findings. Moreover, a significant finding of our study is that an increase in MetS-Z score correlates with a rise in endocan levels. A nearly two-fold disparity was noted between the lower and higher tertiles for endocan levels in the MetS group (Table 2). These findings suggest several pathways that elucidate the role of endocan in metabolic syndrome. The results suggest that a quantitative evaluation of MetS severity could be more effective in precisely forecasting endothelial dysfunction and cardiovascular disease risk in the future. The continuous MetS score facilitates the dynamic monitoring of MetS severity, indicating that participants can be categorized based on MetS severity, allowing for the implementation of various interventions to avoid CVD.

Endocan may aggravate vascular cell failure in metabolic syndrome by promoting activation and cell adhesion. Endocan is associated with endothelial dysfunction in many clinical scenarios [17,23]. Our data suggest that an elevation in the MetS-z score is related with increased endothelial activity, possibly leading to the endothelial dysfunction linked to MetS (Table 2). The adherence of leukocytes through cell adhesion molecules and their corresponding ligands involves inflammation mediated by the cytokines signaling pathways, which have been demonstrated to promote the production of endothelial parameters such as VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 in the endothelium. Researchers have demonstrated that endocan regulates the production of adhesion molecules and integrin-mediated cell adhesion [24,25]. It has been demonstrated to enhance the production of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 facilitate the adherence of monocytes to endothelial cells, elevate inflammation release, and augment vascular proliferation, permeability, and leukocyte migration. Conversely, endocan may impede leukocyte adherence by adhering to inflammation parameters, thereby obstructing the interaction between ICAM-1 [26]. These findings demonstrate that endocan can expedite endothelium cell dysfunction by enhancing inflammation, cell adhesion, and oxidative damage [27–29]. Our results indicated that sICAM-1 and sVCAM-1 levels were significantly elevated in the MetS group relative to the control group, with a steady increase observed from the group 1 to the group 3 in the MetS-z score group (Table 2). Moreover, a nearly two-fold disparity in the levels of these endothelial markers is observed between the group 1 and the group 3 within the MetS-Z score group (Table 2). The increase in the levels of endocan and endothelial parameters appears to be gradual between the groups. Collectively, our findings suggest that an elevation in endocan levels in MetS severity correlates with the activation of endothelial cells, subsequently leading to an increase in circulating adhesion molecules.

Certain investigations observed a substantial association between endocan levels and sICAM-1 and sVCAM-1, underscoring the role of endocan in vascular disease and inflammation [17,30]. Additional research validated that endocan is favorably linked with ICAM-1 in MetS. Moreover, clinical studies have established a favorable correlation between the endothelial dysfunction and endocan levels [17,20,31]. The current investigation reveals a noteworthy finding: the MetS-Z score has a substantial positive connection with serum endocan levels, as well as with other endothelial and inflammatory factor levels (Table 2, Figure 1). Collectively, our findings suggest that the elevation in endocan levels in the MetS group correlates with the activation of endothelial cells, subsequently leading to an increase in blood adhesion molecules (ICAM-1, VCAM-1). This may suggest that elevated endocan, along with other endothelial variables in the MetS group, could be regarded as significant risk factors for the progression of MetS severity.

ROC analysis was performed to evaluate the suitability of endocan values as biomarkers of dysfunctional endothelial cells in MetS. The Endocan ratio exhibited the highest value (AUC = 0.997, p = 0.0001), followed by the sVCAM level (AUC = 0.996, p = 0.0001) (Figure 2). The concentration of endocan demonstrated performance akin to recognized endothelial factors in the MetS group. Thus, Endocan characteristics may be employed to assess endothelial dysfunction in Metabolic Syndrome.

The primary limitation of our investigation is the very small sample size. Enhancing the participant count inside the tertiles could facilitate a more comprehensive understanding of the correlation between the MetS-z score and endocan levels in individuals with MetS. The findings of the current study necessitate more examination in larger investigations. Future research should specifically examine the mechanisms underlying the heightened endothelial activation in individuals with MetS.

5. Conclusions

This study is the first investigation demonstrating that serum endocan is markedly elevated and independently correlated with MetS severity score and endothelial variables in MetS. The elevation of endocan, along with increased endothelial factors, supports endothelial activation in metabolic syndrome. It can be hypothesized that elevated endocan levels in the context of MetS may facilitate endothelial cell failure. Furthermore, endocan levels were determined to may be valuable and dependable in the assessment of MetS. Additional research is necessary to determine which factors are that contributed to these conclusions.

Author Contributions

M.V.; Conceptualization (lead); Supervision (lead); data curation (lead); methodology (lead); software (equal); formal analysis (equal); writing – original draft (lead). S.Y.; Conceptualization (supporting); methodology (equal); data curation (equal); formal analysis (equal). A.C.; Data curation (equal); investigation (equal); methodology (equal),review and editing (equal) Y.S.; Data curation (equal); methodology (equal); software (equal); Formal analysis (equal), review and editing (equal). S.O.Y.; Supervision (lead); Validation (equal); Methodology (equal); supervision (equal); writing – review and editing (equal).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Health Sciences Trabzon Medicine Faculty Ethical Committee for Scientific Research on Humans (Reference number: 2024/93; Approval Date: 23/07/2024) and conducted in accordance with the guidelines in the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients voluntary participated in the study and provided written informed consent.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study's findings are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to appreciate the individuals who agreed to participate in this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BMI |

Body mass index |

| CVD |

Cardiovascular disease |

| DBP |

Diastolic blood pressure |

| Endocan |

Endothelial-specific molecule 1 |

| FBG |

fasting blood glucose |

| HDL-C |

high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol |

| HOMA-IR |

homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance |

| LDL-C |

low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol |

| MetS |

Metabolic syndrome |

| MetS-Z |

MetS severity z score |

| SBP |

Systolic blood pressure |

| TC |

total cholesterol |

| TG |

triglyceride |

| WHR |

waist to hip ratio |

| WHtR |

waist to-height ratio |

References

- Shin, D.; Kongpakpaisarn, K.; Bohra, C. Trends in the prevalence of metabolic syndrome and its components in the United States 2007–2014. Int. J. Cardiol. 2018; 259, 216–219. [CrossRef]

- Beltrán-Sánchez, H.; Harhay, M. O.; Harhay, M. M.; McElligott, S. Prevalence and trends of metabolic syndrome in the adult US population, 1999–2010. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013; 62(8), 697–703. [CrossRef]

- Lee, A. M.; Gurka, M. J.; DeBoer, M. D. A metabolic syndrome severity score to estimate risk in adolescents and adults: current evidence and future potential. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2016; 14(4), 411-413. [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Shruthi, N. R.; Banerjee, A.; Jothimani, G.; Duttaroy, A. K.; Pathak, S.. Endothelial dysfunction, platelet hyperactivity, hypertension, and the metabolic syndrome: molecular insights and combating strategies. Front. in Nutr. 2023; 10, 1221438. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Kaur, M.; Singh, J. Endothelial dysfunction and platelet hyperactivity in type 2 diabetes mellitus: molecular insights and therapeutic strategies. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018; 17, 121. [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Qin, Y. Dyslipidemia and Cardiovascular Disease: Current Knowledge, Existing Challenges, and New Opportunities for Management Strategies. J Clin Med. 2023 ;12, 363. [CrossRef]

- Holewijn, S.; den Heijer, M.; Swinkels, D.W.; Stalenhoef, A.F.; de Graaf, J. The metabolic syndrome and its traits as risk factors for subclinical atherosclerosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009, 94, 2893-9. [CrossRef]

- Krüger-Genge, A.; Blocki, A.; Franke, R.-P.; Jung, F. Vascular Endothelial Cell Biology: An Update. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4411. [CrossRef]

- Balta, S.; Mikhailidis, D.P.; Demirkol, S.; Ozturk, C.; Celik, T.; Iyisoy, A. Endocan: A novel inflammatory indicator in cardiovascular disease? Atherosclerosis. 2015, 243, 339-43. [CrossRef]

- Kali, A.; Shetty, K.S. Endocan: a novel circulating proteoglycan. Indian J Pharmacol. 2014, 46, 579-83. [CrossRef]

- Beltrán-Sánchez, H.; Harhay, M.O.; Harhay, M.M.; McElligott S. Prevalence and trends of metabolic syndrome in the adult U.S. population, 1999-2010. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013, 62(8):697-703. [CrossRef]

- Gurka, M. J.; Lilly, C. L.; Oliver, M. N.; DeBoer, M. D. An examination of sex and racial/ethnic differences in the metabolic syndrome among adults: a confirmatory factor analysis and a resulting continuous severity score. Metabolism. 2014 63(2), 218-225. [CrossRef]

- Gurka, M. J.; DeBoer, M. D.; Filipp, S. L.; Khan, J. Z.; Rapczak, T. J.; Braun, N. D.; Hanson, K. S.; Barnes, C. P. MetS Calc: Metabolic Syndrome Severity Calculator. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Leitzmann, M.F.; Moore, S.C; Koster A.; Harris, T.B.; Park Y.; Hollenbeck, A.; Schatzkin, A. Waist circumference as compared with body-mass index in predicting mortality from specific causes. PLoS One. 2011; 6:e18582. [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.Y.; Yang, C.Y; Shih, S.R.; Hsieh, H.J.; Hung, C.S.; Chiu, F.C.; Lin, M.S; Liu, P.H.; Hua, C.H.; Hsein, Y.C.; Chuang, L.M.; Lin, J.W.; Wei, J.N.; Li, H.Y. Measurement of Waist Circumference: midabdominal or iliac crest? Diabetes Care. 2013, 36,1660-6. [CrossRef]

- Klisic, A.; Patoulias, D. The Role of Endocan in Cardiometabolic Disorders. Metabolites. 2023, 8;13, 640. [CrossRef]

- Ozer Yaman, S.; Balaban Yucesan, F.; Orem, C.; Vanizor Kural, B.; Orem, A. Elevated Circulating Endocan Levels Are Associated with Increased Levels of Endothelial and Inflammation Factors in Postprandial Lipemia. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1267. [CrossRef]

- Sági, B.; Vas, T.; Gál, C.; Horváth-Szalai, Z.; Kőszegi, T.; Nagy, J.; Csiky, B.; Kovács, T.J. The Relationship between Vascular Biomarkers (Serum Endocan and Endothelin-1), NT-proBNP, and Renal Function in Chronic Kidney Disease, IgA Nephropathy: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10552. [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.Y.; Chang, T.T.; Leu, H.B.; Huang, C.C; Wu, T.C.; Chou, R.H.; Huang, P.H.; Yin, W.H.; Tseng, W.K.; Wu, Y.W.; Lin, T.H.; Yeh, H.I.; Chang, K.C.; Wang, J.H.; Wu, C.C.; Chen, J.W.. Novel prognostic impact and cell specific role of endocan in patients with coronary artery disease. Clin Res Cardiol, 2024, . [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Jiang, L.; Yu, X.H.; Hu, M.; Zhang Y.K.; Liu, X.; He, P.; Ouyang, X. Endocan: A Key Player of Cardiovascular Disease. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022, 5;8:798699. [CrossRef]

- Kose, M.; Emet, S.;Akpinar, T.S.; Kocaaga, M.; Cakmak, R.; Akarsu, M.; Yuruyen, G.; Arman, Y.; Tukek, T. Serum Endocan Level and the Severity of Coronary Artery Disease: A Pilot Study. Angiology. 2015, 66(8):727-31. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.S.; Yang, W.; Luo, T.; Wang, J.M.; Jing, Y.Y. Serum endocan levels are correlated with the presence and severity of coronary artery disease in patients with hypertension. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2015, 19(3):124-7. [CrossRef]

- Aparci, M.; Isilak, Z.; Uz, O.;, Yalcin, M.; Kucuk, U. Endocan and Endothelial Dysfunction. Angiology. 2015;66(5):488-489. [CrossRef]

- Chee, Y.J.; Dalan, R.; Cheung, C. The Interplay Between Immunity, Inflammation and Endothelial Dysfunction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1708. [CrossRef]

- Milošević, N.; Rütter, M.; David, A. Endothelial cell adhesion molecules-(un) Attainable targets for nanomedicines. Frontiers in medical technology, 2022, 4, 846065. [CrossRef]

- Gaudet, A.; Portier, L.; Mathieu, D.; Hureau, M.; Tsicopoulos, A.; Lassalle, P.; De Freitas, C. N. Cleaved endocan acts as a biologic competitor of endocan in the control of ICAM-1-dependent leukocyte diapedesis. J Leukoc Biol. 2020 May;107(5):833-841. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; He B. Endothelial dysfunction: molecular mechanisms and clinical implications. Med. Comm. 2024, 5, e651. [CrossRef]

- Medina-Leyte, D.J.; Zepeda-García, O.; Domínguez-Pérez, M.; González-Garrido, A.; Villarreal-Molina, T.; Jacobo-Albavera, L. Endothelial Dysfunction, Inflammation and Coronary Artery Disease: Potential Biomarkers and Promising Therapeutical Approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3850. [CrossRef]

- Medina-Leyte, D.J.; Zepeda-García, O.; Domínguez-Pérez, M.; González-Garrido, A.; Villarreal-Molina, T.; Jacobo-Albavera, L. Endothelial Dysfunction, Inflammation and Coronary Artery Disease: Potential Biomarkers and Promising Therapeutical Approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3850. [CrossRef]

- Pawlak, K.; Mysliwiec, M.; Pawlak, D. Endocan--the new endothelial activation marker independently associated with soluble endothelial adhesion molecules in uraemic patients with cardiovascular disease. Clin Biochem. 2015, 48, 425-30. [CrossRef]

- Mercantepe F, Baydur Sahin S, Cumhur Cure M, Karadag Z. Relationship Between Serum Endocan Levels and Other Predictors of Endothelial Dysfunction in Obese Women. Angiology. 2023, 74, 948-957. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).