1. Introduction

Chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a leading cause of liver cirrhosis, liver failure, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [

1]. The introduction of direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs) has significantly improved treatment outcomes, resulting in high rates of sustained virological response (SVR) in patients with HCV-related chronic liver disease [

2,

3].

NIn Japan, approximately 300,000–600,000 individuals with HCV are treatment-naïve [

4]. Although the WHO aims to eliminate HCV by 2030 [

5], Japan is among the high-income countries projected to meet this target. However, a serious concern is that some individuals who test positive for HCV antibodies do not undergo confirmatory HCV RNA testing [

6]. Consequently, they are not diagnosed as HCV carriers and miss the opportunity to receive DAA therapy [

7]. Therefore, identifying patients eligible for treatment among those who test positive for HCV antibodies is important [

8]. Although automated alerts were incorporated into electronic medical records in Nara Medical University in 2016, and checkups of patients with positive hepatitis virus HCV antibodies and HBs antigen as well as monthly pickups by hepatitis medical coordinators were initiated in 2021, the effectiveness of these efforts remain limited. Thus, effective screening for HCV is essential.

The Elecsys® HCV Duo immunoassay, which was introduced in 2022, simultaneously detects HCV antibodies and the HCV core antigen, with the results being available in approximately 27 minutes. A positive result for the HCV core antigen can already confirm active HCV infection, potentially minimizing the reliance on HCV RNA testing [

9]. This diagnostic tool may facilitate earlier medical intervention and increase the number of patients receiving antiviral therapy. This study aimed to determine the number of patients with positive HCV RNA tests who are eligible to receive DAA therapy at Nara Medical University and to identify effective methods for screening these patients.

2. Materials and Methods

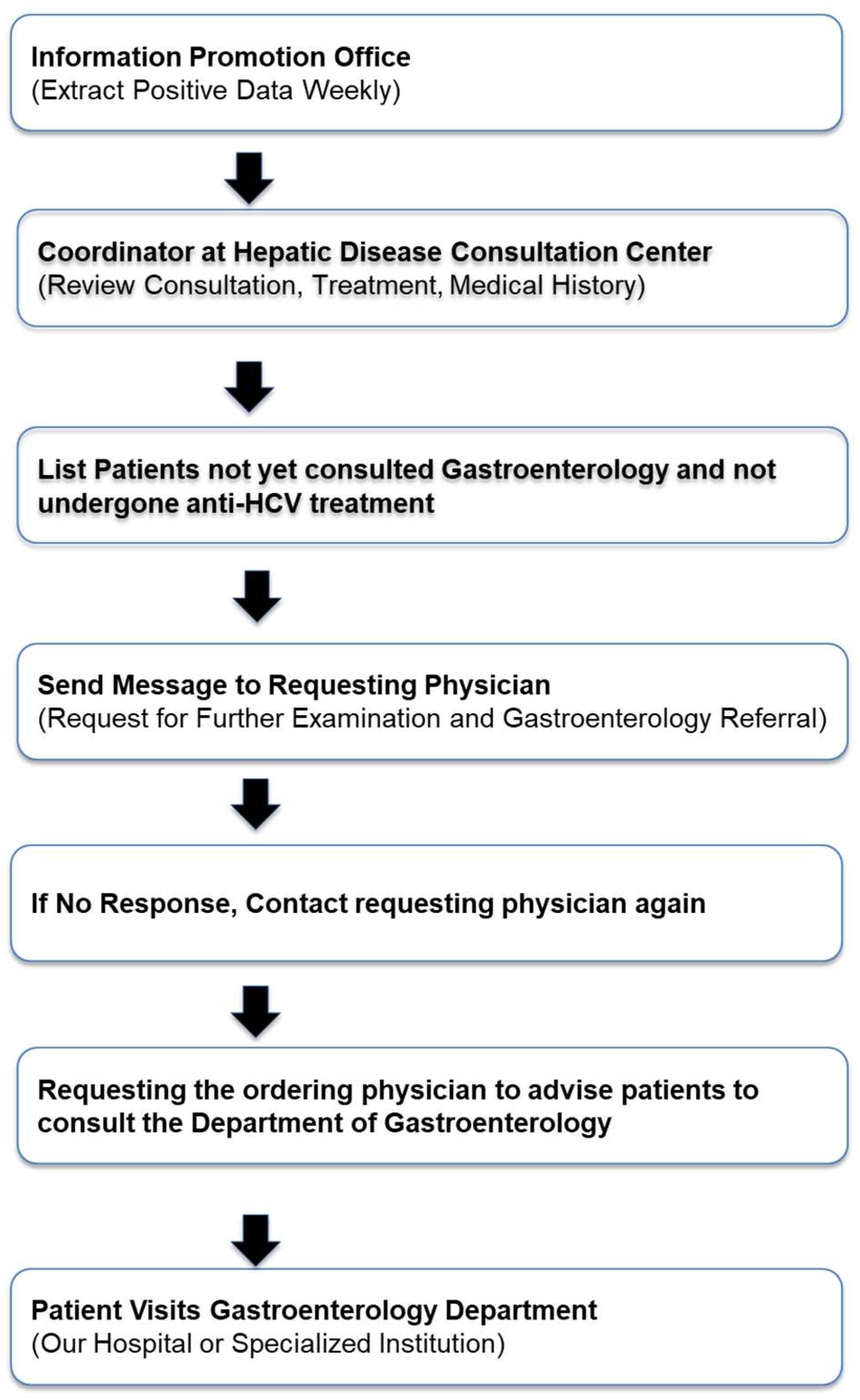

This is a retrospective cohort study that included 866 patients who tested positive for HCV antibodies between June 2021 and May 2024. Nara Medical University started hepatitis medical coordinator activities in 2015. Using the alert function of the electronic medical record, a message was sent to physicians to order tests to confirm chronic hepatitis B virus and HCV infections and to recommend patients with HCV to consult hepatologists and gastroenterologists (

Figure 1). In 2021, Nara Medical University implemented the In-Hospital Hepatitis Virus Screening System Flow to enhance the detection and management of hepatitis infections in response to the historically low screening rates in Nara Prefecture (

Figure 2). This initiative aimed to improve the early diagnosis and treatment outcomes of patients with hepatitis B and C, which contribute to the development of liver disease such as HCC.

The protocol for this study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Nara Medical University (Committee of Nara Medical University approval no. Nara 468) and conforms to the provisions of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later revisions. An opt-out procedure was employed to obtain consent.

2.1. Effectiveness of the New In-Hospital Hepatitis Virus Patient Identification System

The In-Hospital Patient Identification System Flow is as follows (

Figure 1):

Once a week, we extracted data of patients with positive hepatitis virus test results from the information promotion office. Consultation records, treatments, and medical history of each patient were obtained from the Liver Disease Consultation Center coordinator and thoroughly reviewed. Through consultation with a dedicated hepatologist, the system identified individuals who test positive for HCV antibodies, have not been seen at the Department of Gastroenterology, and have not received anti-HCV treatment. Via the electronic medical record system, a notification was sent to the ordering physician that recommended further examinations and encouraged referral to the Department of Gastroenterology in collaboration with the hepatitis coordinator. If the response from the ordering physician was unclear, the coordinator contacted the physician for confirmation. The ordering physician then instructed the patient to seek consultation with the Department of Gastroenterology at Nara Medical University Hospital.

3. Results

3.1. Frequency of Referral Requests Issued to Physicians Who Ordered HCV Antibody Tests

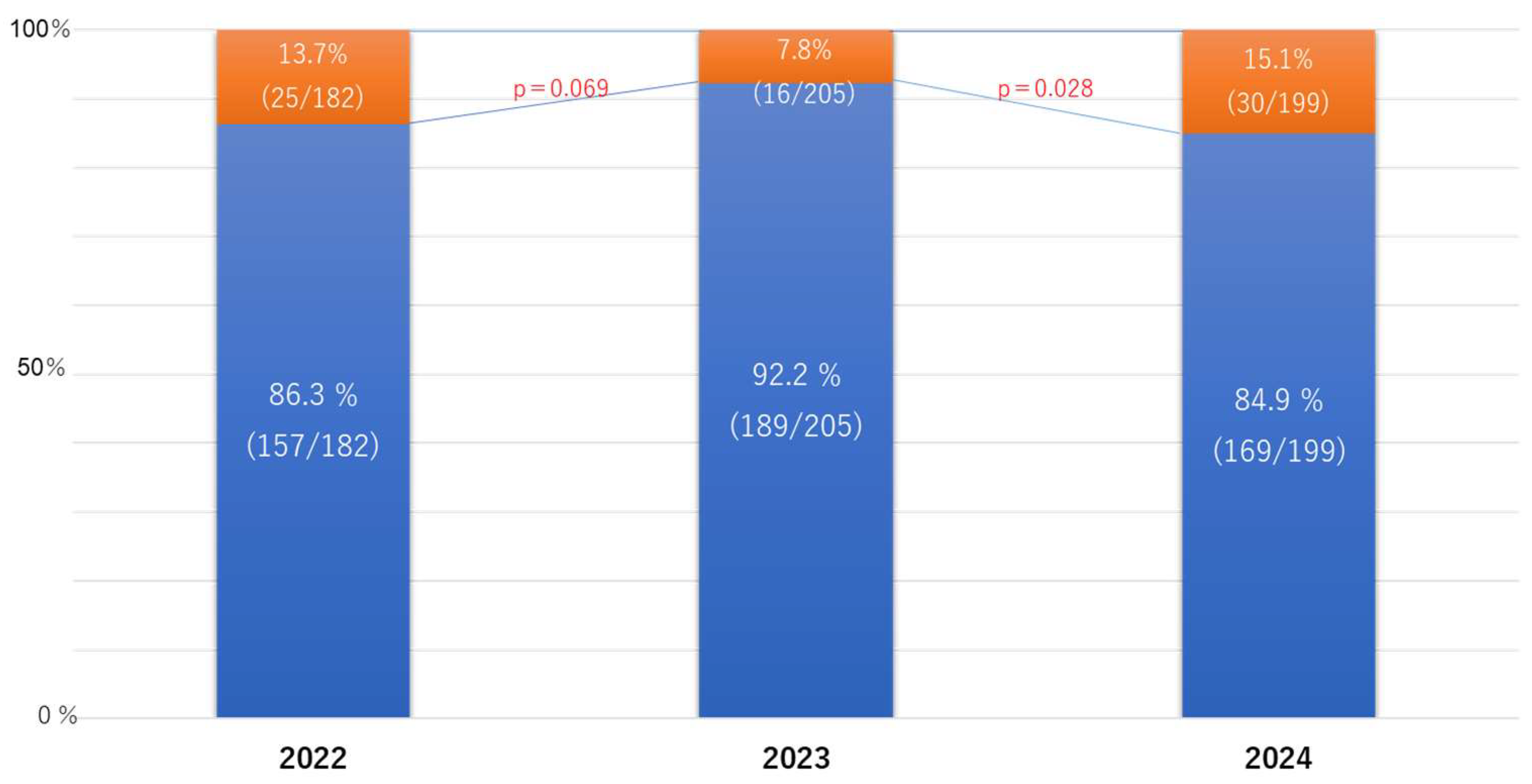

Although the rate of consultations decreased from 13.7% in 2022 to 7.8% in 2023, it significantly increased to 15.1% in 2024 (

Figure 1).

3.2. Diagnosing HCV Infection

Among the 866 patients who underwent anti-HCV testing, HCV RNA evaluations were performed in 253 (29.2%) patients; 57 from the Department of Gastroenterology and 196 from other medical departments (

Table 1).

Among the 253 anti-HCV-positive cases, the HCV RNA positivity rate was 16.6% (n = 42); 26 (45.6%) and 16 (8.2%) cases were from the Department of Gastroenterology and other departments, respectively (

Table 2,

Figure 3).

Of the 42 patients who were HCV RNA-positive, 29 (69.0%) were treatment-naïve; 15 (51.7%) and 14 (48.3%) were from the Department of Gastroenterology and other departments, respectively. Meanwhile, the 13 (31.0%) patients

Among the 42 patients who tested positive for HCV-RNA, 31.0% (n = 13) received an 8-week course of HCV DAA therapy (

Table 3).

3.3. Potential HCV Infection

Meanwhile, the 613 (70.8%) patients who tested positive for anti-HCV antibodies but did not undergo HCV RNA evaluations included 41 patients from the Department of Gastroenterology and 572 patients from other medical departments (

Table 1).

Based on the observed RNA positivity rate of 16.6%, an estimated 66/613 patients, comprised of 19 (45.6%) from the Department of Gastroenterology and 47 (8.2%) from other departments, were potentially positive for HCV RNA (

Table 2).

4. Discussion

In this study, we observed that the rate of identified HCV-positive cases initially declined following the introduction of a new hepatitis screening and identification system. However, the contact rate with the examining physicians at the hospital significantly increased.Based on the observed HCV RNA positivity rates, approximately 66 patients who may require DAA therapy were overlooked. This may be partially explained by insufficient HCV antibody screening and inadequate coordination regarding anti-HCV-positive cases between the hepatitis care coordinator and physicians in other departments [

10]. Strengthening referral pathways and incentivizing greater engagement by primary care physicians on hepatitis C management are critical to ensure that screening efforts translate into effective clinical interventions [

11].

In 2016, automated alerts were integrated into the electronic medical record system and almost simultaneously implemented across most clinical departments. In 2021, the standardized “Flowchart for HCV Antibody (HCV Ab) and HBs Antigen (HBs Ag) Positive Patients” was established to guide subsequent clinical actions, resulting in effective multidisciplinary collaboration regarding hepatitis care activities. However, despite the immediate review of patients positive for HCV antibodies and HBs antigen and the monthly follow-up by hepatitis medical coordinators, there was a significant increase in the number of cases wherein positive test results were not adequately communicated to the patients. Therefore, “leader coordinators,” which included members from various professions such as a nurse, a pharmacist, and a physical therapist, were introduced, but their effectiveness was limited. These findings highlight systemic shortcomings that undermine early diagnosis and timely treatment, which are critical steps for achieving the national hepatitis C elimination targets. In Germany, initiatives aimed at enhancing the hepatitis C care continuum represent a significant advancement in improving hepatitis C care and include reflex testing, wherein laboratories automatically conduct HCV RNA PCR testing on anti-HCV-positive samples obtained through the “Check-Up” program [

12]. As such, further local structural interventions are needed.

The prevalence of an SVR is high among patients with positive HCV antibody results. The clinical utility of the HCV core antigen has been reported [

13,

14]. The Elecsys® HCV Duo assay enables the simultaneous detection of HCV antibodies (Duo/Ab) and core antigen (Duo/Ag) at a reimbursement rate of 102 points, which is equivalent to that of conventional anti-HCV antibody testing (approximately USD 6.84) [

15]. Additionally, this assay can identify approximately 80% of patients with active HCV infection even without performing confirmatory HCV RNA testing, thereby streamlining the diagnostic process and reducing the time to treatment initiation [

16]. These findings indicate that the Duo assay can substantially reduce the costs associated with HCV RNA testing (insurance score: 412 points) to identifying HCV carriers, and that up to 85% of previous follow-up testing may have been unnecessary [

9]. Employing the Duo assay may also significantly reduce the workload for healthcare personnel, including physicians, administrative staff, nurses, and hepatitis care coordinators [

9,

17]. As it has a rapid turnaround time of 27 minutes and costs similar to that of standard HCV-Ab testing, the Duo assay offers a cost-effective and time-efficient strategy for the early identification of patients with HCV [

18]. Through same-day confirmation of active infection, the HCV Duo assay may also potentially reduce diagnostic delays, streamline care pathways, and enhance referral rates to specialized departments [

19]. Moreover, integrating the Duo assay into routine screening programs could substantially improve the linkage to care and support national efforts toward HCV elimination [

20].

This study has several limitations. First, it was conducted retrospectively. Second, the cohort consisted exclusively of Japanese patients and only included HCV genotypes 1 and 2. Third, the estimated number of patients with positive HCV RNA tests was only a theoretical projection and did not correspond to the actual number of individuals.

In conclusion, among 613 cases that tested positive for the HCV antibody, 66 patients would remain HCV RNA-positive based on the RNA positivity rates observed at the respective facilities. Simultaneous measurement of the HCV antibody and core antigen by the HCV Duo immunoassay offers significant medical, temporal, and economic advantages by eliminating the need for separate HCV RNA testing. The Duo assay has the potential to be an important and essential screening tool to support efforts aimed at HCV elimination and facilitate the diagnosis of chronic HCV infection and prompt initiation of DAA therapy.

Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were conducted using EZR (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University), version 1.68 [

21]. Fisher’s exact probability test was employed to evaluate relationships between the two groups. A two-sided p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Author Contributions

T.N.: Writing—original draft—equal. T.N.: Writing—review and editing—equal. T.A.: Data curation—equal: M.M.: Formal analysis—equal. K.O.: Investigation—equal. Y.E.: Investigation—equal. T.N.: Methodology—equal. H.Y: Supervision—equal. H.Y.: Writing—review and editing—equal. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was partially supported by a grant-in-aid for research on hepatitis from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development Sciences Research Grant ID: 23HC2001.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study protocol conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later revisions. Written informed consent for the use of the resected tissue was obtained from all patients, and the study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Nara Medical University (Nara, no. 468).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Raw data were generated at Nara University Hospital. The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author (T.N.) upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Chuaypen, N.; Chittmittrapap, S.; Avihingsanon, A.; Siripongsakun, S.; Wongpiyabovorn, J.; Tanpowpong, N.; Tanaka, Y.; Tangkijvanich, P. Liver fibrosis improvement assessed by magnetic resonance elastography and mac-2-binding protein glycosylation isomer in patients with hepatitis C virus infection receiving direct-acting antivirals. Hepatol. Res. 2021, 51, 528–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musto, F.; Stracuzzi, M.; Cibarelli, A.; Coppola, C.; Caiazzo, R.; David, D.; Di Tonno, R.; Garcia, M.L.; Valentino, M.S.; Giacomet, V. Real-life efficacy and safety of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir pediatric formulation for chronic hepatitis C infection in children aged 3 to 12 years: a case series of 6 patients. Clin. Ther. 2025, 47, 244–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawlowska, M.; Dobrowolska, K.; Moppert, J.; Pokorska-Śpiewak, M.; Purzynska, M.; Marczynska, M.; Zarebska-Michaluk, D.; Flisiak, R. Real-world efficacy and safety of an 8-week glecaprevir/pibrentasvir regimen in children and adolescents with chronic hepatitis C—results of a multicenter epiter-2 study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, J.; Kurisu, A.; Ohara, M.; Ouoba, S.; Ohisa, M.; Sugiyama, A.; Wang, M.L.; Hiebert, L.; Kanto, T.; Akita, T. Burden of chronic hepatitis B and C infections in 2015 and Future trends in japan: a simulation study. Lancet Reg. Health – West. Pac. 2022, 22, 100428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, H.; Sanchez Gonzalez, Y.; Yuen, C.; Cornberg, M. Global timing of hepatitis C virus elimination in high-income countries. Liver Int. 2020, 40, 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spradling, P.R.; Tong, X.; Rupp, L.B.; Moorman, A.C.; Lu, M.; Teshale, E.H.; Gordon, S.C.; Vijayadeva, V.; Boscarino, J.A.; Schmidt, M.A. Trends in HCV RNA testing among HCV antibody-positive persons in care, 2003-2010. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2003, 59, 976–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, T.; Pritlove, C.; Shearer, D.; Tadrous, M.; Shah, H.; Gomes, T. Correction: accessing hepatitis C direct acting antivirals among people living with hepatitis C: a qualitative study. Int. J. Equity Health 2023, 22, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, A.; Hutchinson, S.J.; Weir, A.; Barclay, S.; Schofield, J.; Frew, C.G.; Goldberg, D.J.; Heydtmann, M.; Wilson-Davies, E. Liver function tests in primary care provide a key opportunity to diagnose and engage patients with hepatitis C. Epidemiol. Infect. 2022, 150, e133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majchrzak, M.; Bronner, K.; Laperche, S.; Riester, E.; Bakker, E.; Bollhagen, R.; Klinkicht, M.; Vermeulen, M.; Schmidt, M. Multicenter performance evaluation of the Elecsys HCV duo immunoassay. J. Clin. Virol. 2022, 156, 105293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGibbon, E.; Bornschlegel, K.; Balter, S. Half a Diagnosis: gap in confirming infection among hepatitis C antibody-positive patients. Am. J. Med. 2013, 126, 718–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, J.V.; Wiktor, S.; Colombo, M.; Thursz, M. Micro-elimination – a path to global elimination of hepatitis C. J. Hepatol. 2017, 67, 665–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petroff, D.; Bätz, O.; Jedrysiak, K.; Lüllau, A.; Kramer, J.; Möller, H.; Heyne, R.; Jäger, B.; Berg, T.; Wiegand, J. From screening to therapy: anti-HCV screening and linkage to care in a network of general practitioners and a private gastroenterology practice. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prostko, J.; Rothman, R.; Hsieh, Y.-H.; Pearce, S.; Kilbane, M.; McAuley, K.; Frias, E.; Taylor, R.; Ali, H.; Buenning, C. Performance evaluation of the abbott alinity hepatitis C antigen next assay in a US urban emergency department population. J. Clin. Virol. 2024, 175, 105743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumbhar, N.; Ramachandran, K.; Kumar, G.; Rao Pasupuleti, S.S.; Sharma, M.K.; Gupta, E. Utility of hepatitis C virus core antigen testing for diagnosis and treatment monitoring in HCV infection: a study from India. Indian J. Med. Microbi. 2021, 39, 462–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanokudom, S.; Poovorawan, K.; Nilyanimit, P.; Suntronwong, N.; Aeemjinda, R.; Honsawek, S.; Poovorawan, Y. Comparison of anti-HCV combined with HCVcag (Elecsys HCV duo immunoassay) and anti-HCV rapid test followed by HCV RNA analysis using qRT-PCR to identify active infection for treatment. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0313771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Jin, F.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, X. Evaluation of a new human immunodeficiency virus antigen and antibody test using light-initiated chemiluminescent assay. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1474127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, T.I.; Brown, A.P.; Brown, M.; Lawless, S.; Roemmich, B.; Anderson, N.W.; Farnsworth, C.W. Comparison of a dual antibody and antigen HCV immunoassay to standard of care algorithmic testing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2024, 62, 83224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odari, E.; Budambula, N.; Nitschko, H. Evaluation of an antigen-antibody “combination” enzyme linked immunosorbent assay for diagnosis of hepatitis C virus infections. Ethiop J. Health Sci. 2014, 24, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananchuensook, P.; Wongpiyabovorn, J.; Avihingsanon, A.; Tangkijvanich, P. Performance of Elecsys® HCV duo immunoassay for diagnosis and assessment of treatment response in HCV patients with or without HIV infection. Diagnostics 2019, 14, 2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, G.S.; Flower, B.; Cunningham, E.; Marshall, A.D.; Lazarus, J.V.; Palayew, A.; Jia, J.; Aggarwal, R.; Al-Mahtab, M.; Tanaka, Y. Progress towards elimination of viral hepatitis: a lancet gastroenterology & hepatology commission update. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 9, 346–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanda, Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2013, 48, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).