1. Introduction

General Relativity (GR) and Quantum Mechanics (QM) each provide a distinct and comprehensive understanding of the universe at different scales. GR governs the macroscopic behaviour of spacetime and gravity [

1], while QM describes the probabilistic nature of particles at the microscopic level [

2,

3]. However, an intriguing question arises when these two realms intersect: How does the inherent uncertainty in quantum systems influence the curvature of spacetime as described by GR.

The quest to reconcile GR and QM has been one of the most significant challenges in theoretical physics. Traditional approximations, such as semiclassical gravity, attempt to bridge this gap by using the expectation value of the stress-energy tensor to influence the curvature of spacetime as described by GR [

4]. However, this approach assumes a deterministic description of spacetime geometry, which seems inadequate when considering the inherently probabilistic nature of the quantum world.

In contrast, this research investigates a different perspective: the direct impact of quantum uncertainty - specifically in the position or momentum of particles - on the curvature of spacetime itself. Rather than taking the expectation value of the stress-energy tensor, this study explores the uncertainty in spacetime curvature that arises when particles at the boundary of a past light cone exhibit quantum uncertainties.

In this research, we explore the implications of introducing conditional probability theory into the framework of GR, particularly how it influences the curvature of spacetime at a point when particles on the boundary of its past light cone exhibit momentum or positional uncertainty. Traditionally, GR treats spacetime curvature as deterministic; however, on using Bayesian analysis, the presence of uncertainties suggests that this curvature may itself become uncertain under certain conditions.

Motivated by the potential to understand the link between these two theories, if any, we apply a heuristic Bayesian approach to assess the probability of an eigenstate of a particle within uncertain spacetime geometries. This study not only offers a novel perspective on the interaction between quantum mechanics and general relativity but also provides a methodological framework that could be instrumental in advancing our understanding of gravity. By investigating the probabilistic nature of spacetime curvature, this research paves the way for new approach to investigate effects of quantum effects on gravity.

To frame this investigation, we draw upon Total Probability Theorem, a fundamental concept in probability theory that allows us to update the probability of an event based on new information. In its simplest form, Total Probability Theorem relates the total probability of an event A occurring to the sum of probabilities of A occurring under different conditions, weighted by the likelihood of those conditions. Mathematically, this is expressed as [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]:

Here, represents the total probability of event A, is the probability of a specific condition occurring, and is the probability of Event A ocurring given that has occurred. This theorem provides a powerful tool for understanding complex systems where multiple factors contribute to a given outcome.

By leveraging Total Probability Theorem, we can extend our analysis to calculate the total probability of a particle being in a specific eigenstate when it travels through an uncertain spacetime geometry. In this scenario, the total probability is determined by using the probabilities of the particle’s eigenstate after time evolution in each of the possible spacetime geometries that might arise due to quantum uncertainties.

To better understand it, let’s imagine you have two boxes, Box A and Box B. Each box contains a certain number of balls of different colours.

Now, let’s say you want to find the probability of drawing a red ball. However, you don’t know which box you’re drawing. This uncertainty is akin to being in a superposition of two states as there’s uncertainty about the state of the system until it is observed or measured. Here’s where conditional probability and total probability come into play.

In this scenario, you need to determine the total probability of drawing a red ball without knowing which box you are drawing from. To find this total probability, you apply the law of total probability, which combines the probabilities of drawing a red ball from each box, weighted by the likelihood of choosing each box.

Mathematically, if we denote the event of drawing a red ball as R, and the event of selecting each box as A (selecting Box A) and B (selecting Box B). The probability of drawing a red ball from Box A, denoted and the probability of drawing a red ball from Box A, denoted . The total probability can be expressed as:

In the context of this research, we can analogously consider event A as observing a particle in a given eigenstate, and as representing different possible spacetime manifolds. The conditional probability then corresponds to the likelihood of observing the particle in a certain eigenstate after time evolution in a specific spacetime geometry.

The subsequent sections of this study will delve into deriving the rules for determining , where is one of spacetime manifold arising out of the uncertainty in curvature of the spacetime. By employing Total Probability Theorem, we aim to calculate the probability of observing a test particle in a given eigenstate within a spacetime geometry that possesses uncertainty in its curvature.

2. Conditional Probability Theory in Gravity

In the previous section, we discussed how the probabilistic nature of quantum systems can influence the curvature of spacetime and, consequently, how the state of a particle evolves in such an uncertain geometry. To quantify this relationship, we can leverage the concept of conditional probability, which allows us to rigorously calculate the likelihood of an event given the occurrence of another related event.

Specifically, we are interested in the relationship that is captured by the Bayes’ theorem [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]:

is the probability of Event A occurring due to Event B,

is the probability of both Event A and Event B occurring and

is the probability of Event B occurring

From this, we can conclude that the joint probability can also be expressed as .

This expression highlights how the probability of both events A and B occurring together depends on the probability of B and the conditional probability of A given B.

If we consider the scenario where the conditional probability is equal to the reverse conditional probability , we can also express as .

In this case, becomes equal to , meaning the probability of Event A is equal to the probability of Event B occurring.

Now, consider a scenario where Event

A is defined as the value of the metric

at a specific spacetime point

, which depends on the mass equivalence

of Particle

B1. Here,

is the relativistic mass of Particle

B, and Event

B corresponds to the observation of Particle

B at the coordinates

, assuming there is no uncertainty in the momentum of Particle

B.

where

is the function of Particle B’s mass equvalence and position on the boundary of the past light cone of

determing

.

In the deterministic framework of General Relativity, if Particle B is separated from by a light-like interval, the metric at will be determined by Particle B’s energy and position. This deterministic relationship dictates the probability of the metric at being influenced by Particle on being seperated by a light like interval to be 1.

Conversely, if the metric at

is influenced by the energy and position of Particle B, then Particle B must be separated from

by a light-like interval. This means

Now that we have proven

for this case, we can conclude

to be true for this case, which can be also expressed as

where

ids the position space wave function of particle B

Since the sum of probabilities across all scenarios must equal 1, a normalization condition must be satisfied:

To achieve this normalization, we can define a normalizing constant (Z) as :

With this understanding, we now examine a scenario where Event A corresponds to the values of the metric

at

being dependent on

; where

is the mass equivalence of Particle B and Event B is defined as observation of Particle B with momentum

at

[

9,

10,

11], considering there is no uncertainty in position of particle B, we get

where

is the function of Particle B’s mass equvalence and position on the boundary of the past light cone of

determing

.

Moreover, using similar reasoning to that employed in Equation (

3), the probability of

being dependent on

if Particle B is observed with

at

and its converse will be 1.

Consequently, Equation (

6) simplifies to

where

is the momentum space wave function of Particle B.

In Equations (5) and (7), it has been demonstrated that the probability of the metric values depends on the likelihood of observing Particle B in the momentum and position eigenstates corresponding to the specific spacetime geometry at under consideration. If Particle B, at , has number of momentum eigenstates, then Particle B will correspondingly have different mass equivalence eigenvalues , which in turn produce distinct s for the spacetime point associated with each respective eigenvalue .

Continuing, if we extend this framework to include uncertainties in both the momentum and position of Particle B, the uncertainty in the metric

is then linked to the likelihood of observing Particle B in a momentum and position eigenstate that corresponds to a particular spacetime geometry at

as seen in Equation (

8).

Building upon our reasoning applied in Equations (5) and (7), when considering uncertainty in both momentum and position of Particle B simultaneously, on inputting Event A as value of the metric

at

being dependent on

; where

is the mass equivalence of Particle B and event B as Particle B is observed with

at

, we get

On considering there are

number of spacetime points separated by light like interval from

where particle B has a non-zero probability of being observed and

number of momentum eigenstates at the respective retarded times where position space distribution of particle B is non zero at the light like interval separated spacetime point, we can ascertain that there will be

number of

values as

, where

is the Schwarzschild metric such at the wavepacket (Particle B) is observed at nth spacetime point.

2.

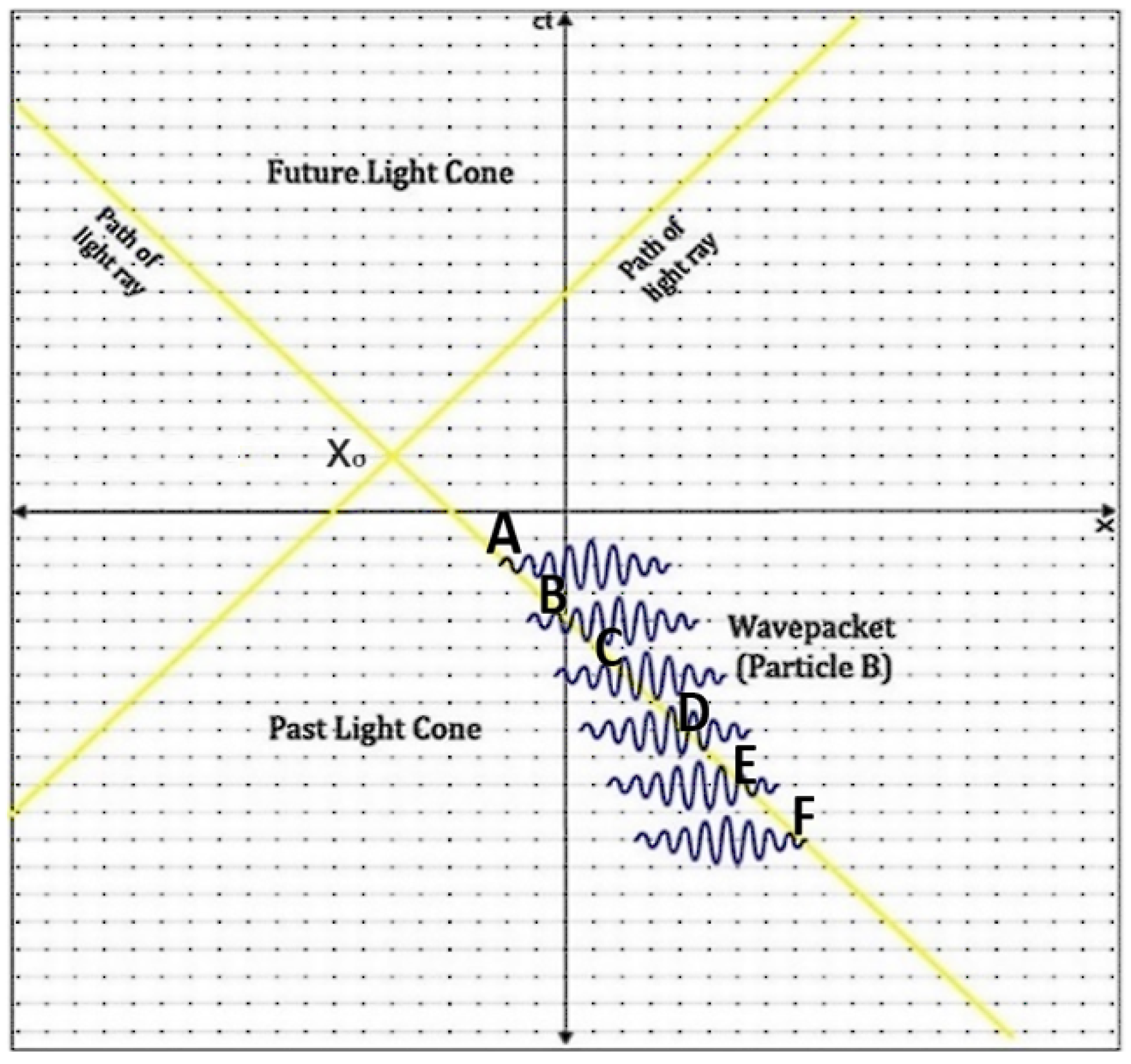

Let’s understand it by analysing the metric at the spacetime point

using

Figure 1.

The Schwarzschild metric at

will be a function of the distance of separation

such that wavepacket (Particle B) is observed at spacetime point A and the ’observed’ mass equivalence of the wavepacket at the corresponding time in that frame of refernece.

On taking into account presence of energy at point B, C, D, E and F, the metric becomes (let).

Now, if have number of values respectively due uncertainty in momentum of particle B at the spacetime point A, B, C, D, E and F, then there will be number of values can have.

Given this, for

to be 1, it is necessary for Event B to correspond to the observation of particle B with momenta

at their corresponding

, where

are the mass equivalence values of Particle B at

corresponding to that value of

inputted in

as per the argument discussed previosuly for Equation (

5).

3. Particle Propagation in Spacetime with Uncertainty in Their Metric

Building upon the framework where the metric of spacetime is treated probabilistically, we now consider how this uncertainty affects the propagation of particles. The previous discussion laid out how a particle’s observables be proabilistically correlated with specific values of the metric in an uncertain spacetime curvature. Extending this idea, we now approach the problem of particle propagation by first discretizing spacetime into extremely small regions, each with a distinct set of possible metric values. This allows us to model the manifold structure of spacetime as a composite of these regions, each with uncertainty in its geometry.

These segments form a set of infinitesimally small regions, labeled as region 1, region 2, region 3, ..., up to region j. Within each region, the metric can take on a number of possible values, denoted by for regions 1 through j, respectively.

This discretization gives rise to a total of distinct manifolds, , each corresponding to a unique combination of metric values across all regions. The manifold is characterized by the specific set of values that the metric assumes in each region. Since the metric in each region is uncertain, the overall structure of spacetime is not fixed.

The multiplication rule of probability states that the probability of a series of independent events all occurring is the product of their individual probabilities. In the context of proability of manifold

, this principle applies by considering the manifold’s representation as a set of infinitesimally small regions. Each metric value is a constituent event whose probability that is independent of values of metric in the other regions in the manifold under consideration. To find the total probability of observing manifold

, we multiply the probabilities of observing each of these metric values in their respective regions

where

is the value of the metric in region n in manifold

and

is the probability observing the regions with the

value corresponding to that manifold.

Once we have determined all possible manifolds and their associated probabilities, we can determine the particle propagation in these classical manifolds by solving the S-matrix for each manifold. The wavefunction of the particle in manifold denoted as

To connect this with the observable outcomes, we apply Total Probability Theorem. Let us consider event

as the probability of the observing spacetime as manifold

, and the event (

) as the observation of the test particle with a momentum eigenstate

at time

in the manifold

. The contribution from this scenario (time evolution of particle in manifold

) to overall probability of the observing particle with momentum

p at time

is given by:

Similarly, if we define Event

as probability of manifold

and Event

as observing the test particle in position eigenstate

in manifold

, probability of the particle A to be observed at the given coordinate due to this scenario contributing to overall probability

To obtain the overall probability distributions for the particle’s momentum and position, we sum over all possible manifolds . This gives us the resultant probability distributions:

Having derived the modulus of the phase space distributions of the canonically conjugate variables - momentum and position - we can now reconstruct the wavefunctions in their respective spaces. This is achieved through iterative phase retrieval algorithms, which are crucial for reconstructing the phase information using the modulus of two distributions in their respective canonically conjugate spaces. Algorithms such as the Gerchberg-Saxton and Fienup algorithms are particularly effective in this context. They employ this iterative approach for phase retrieval [

12,

13,

14,

15]. These methods, originally developed for applications in optics and imaging systems, are now increasingly used in quantum mechanics for quantum state reconstruction and quantum tomography.

At distances where uncertainties in the metric at a spacetime point become negligible, each scenario for the spacetime geometry converges, and the metric effectively assumes a single value. In these cases, the probabilistic nature of the framework ceases to have an impact, and the model simplifies to the deterministic nature of general relativity. This transition occurs because the uncertainty in the metric becomes insignificant, making all scenarios nearly identical to one another. Consequently, the system aligns with the classical description, where spacetime curvature is solely dictated by the energy-matter distribution, as governed by Einstein’s field equations.

At distances where the ratio of uncertainty in the Schwarzschild radius to the distance of seperation from the position expectation value of the particle curving spacetime at the correponding retarded time, becomes negligible, i.e., for the uncertainty in the metric are effectively zero, and the spacetime geometry transitions to the deterministic framework of general relativity.

An uncertainty in

produces an uncertainty in

as:

To evaluate the uncertainty in

, we use:

with

, where

and

are the momentum and energy expectation values respectively.

Substituting this into

, we get

For a highly relativistic particle,

and

, so the equation reduces to

We know

and for a wave packet of wavelength

,

, we get

. Substituting that into

, we find

For distances from the position expectation value of the particle curving spacetime , the uncertainty in the metric becomes negligible, and the probabilistic effects of the framework vanish. This regime aligns with macroscopic scales, where quantum uncertainties are negligible, and the classical solution accurately describes spacetime geometry.

Conversely, in a spacetime being curved by a for a wave packet of wavelength at distances or less from the wavepacket, the uncertainty in the metric becomes significant. In these regimes, the framework described in this study offers a comprehensive approach to account for the probabilistic effects of quantum uncertainties on spacetime geometry.

The term establishes a critical length scale below which quantum uncertainties in the spacetime metric become significant. In this formulation, the characteristic length scale is directly tied to the particle’s wavelength. For a given wavelength , the model indicates that spacetime curvature can be predicted accurately only at distances in order of and exceeding from the position expectation value of the particle curving spacetime. As the particle’s wavelength decreases (corresponding to an increase in energy), the description implies that the regime of its validity shifts to larger scales.

In our semiclassical framework, the derived length scale establishes a natural boundary for the applicability of the model—it functions effectively only near the Planck length and not beyond it. When the particle’s wavelength is comparable to the Planck length , where , the characteristic scale reduces to , affirming that the approach is intrinsically limited to phenomena at or near the Planck scale.

Furthermore, for a particle whose wavelength is smaller than the Planck scale, the inverse dependence on in the expression causes the corresponding length scale to exceed the Planck length, as is evident from the equation. This result indicates that when dealing with sub-Planckian wavelengths, the semiclassical model predicts a regime where the effective length scale becomes larger than , thereby delineating the limit beyond which the current approximation ceases to provide a valid description.

This reinforces the model’s limitation: while it may function near the Planck length, beyond this threshold, it cannot accurately predict spacetime curvature, and a more fundamental approach should be employed to describe the physics at these extreme scales. The model presented here is valid and applicable near the Planck length, but it ceases to be accurate for distances smaller than this characteristic scale.

Thus, while our model successfully bridges the transition from probabilistic to deterministic behavior as one moves from microscopic to macroscopic scales and captures the dynamic interplay of uncertainties at small scales while converging to the deterministic behavior of spacetime at larger scales, it also inherently highlights its own limitations. It operates effectively in regimes where the distance from the position expectation value in order of and exceeding , but for distances smaller than this critical scale, a more fundamental approach is required to fully capture the underlying physics.

4. Discussion

The interplay between quantum mechanics (QM) and general relativity (GR) represents one of the most profound challenges in modern physics. This study addresses a key aspect of this problem by exploring the influence of quantum uncertainties on spacetime curvature. Employing a Bayesian framework, we uncover several critical insights into the probabilistic nature of spacetime and its implications for gravitational phenomena.

A central result of this work is the demonstration that uncertainties in the position and momentum of particles introduce corresponding uncertainties in the spacetime metric. By modeling spacetime as a collection of probabilistic manifolds, the study extends the scope of GR into regimes where deterministic assumptions no longer hold.

One of the key insights pertains to the scale at which quantum effects necessitate this probabilistic framework for accurately describing wavefunction evolution. The analysis reveals that this framework becomes indispensable at scales, where is the wavelength of the particle curving spacetime. This criterion delineates the transition from the deterministic regime of classical GR to a probabilistic regime dominated by quantum uncertainties.

At macroscopic scales, where , the uncertainties in spacetime curvature are negligible, and the framework naturally converges to the deterministic predictions of GR. Conversely, for wave packets with larger wavelengths, the distance r at which the probabilistic effects become significant can be extremely small. However, for highly relativistic particles with longer wavelengths, this transition scale shifts, making the framework relevant over larger distances. The derived scale dependency thus highlights the importance of this framework in regimes where quantum effects play a non-negligible role in determining spacetime geometry.

Future work extending the framework to include multi-particle systems or exploring its implications for cosmological models may further enrich our understanding or help us validate this framework. In particular, analyzing collective quantum effects in gravitational systems and their role in early-universe dynamics may provide key observational signatures.

In conclusion, this study establishes a probabilistic framework for spacetime curvature influenced by quantum uncertainties. By demonstrating the scale at which quantum effects become significant, it provides a robust methodology for accurately determining the time evolution of wavefunctions in uncertain spacetimes.

Funding

No funding was received for this research.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

It has not been published elsewhere and that it has not been submitted simultaneously for publication elsewhere.

Data Availability Statement

No Data associated in the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

I thank Dr. Alok Laddha (Chennai Mathematical Institute, India) for all the fruitful discussions.

Conflicts of Interest

There is no conflicting interest to disclose.

References

- Smeenk, C.; Wuthrich, C. Determinism and general relativity. Philos. Sci. 2021, 88, 638–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovelli, C. The relational interpretation of quantum physics. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2109.09170. [Google Scholar]

- Man’ko, O.V.; Man’ko, V.I. Probability Representation of Quantum States. Entropy 2021, 23, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Struyve, W. Towards a Novel Approach to Semi-Classical Gravity. In The Philosophy of Cosmology; Chamcham, K., Silk, J., Barrow, J.D., Saunders, S., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017; pp. 356–374. [Google Scholar]

- Gelman, A.; Shalizi, C. Philosophy and the practice of Bayesian statistics. Br J Math Stat Psychol. 2013, 66, 8–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoot, R. Bayesian statistics and modelling. Nat Rev Methods Primers 2021, 1, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooij, R.; Schulz, K. Conditionals, causality and conditional probability. J. Log. Lang. Inf. 2019, 28, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pederson, R. Conditional probability density functional theory. Phys. Rev. B 2451, 105, 245138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajek, A. Conditional probability. Philosophy Of Statistics 2011, 99–135. [Google Scholar]

- Chataignier, L. Relational observables, reference frames, and conditional probabilities. Phys. Rev. D 2021, 103, 026013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaynes, E. Probability theory: The logic of science; Cambridge university press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pluzhnik, E.; Sirbu, D.; Belikov, R.; Bendek, E.; Dudinov, V. Wavefront retrieval through random pupil plane phase probes: Gerchberg-Saxton approach. arxiv 2017, arXiv:1709.01571. [Google Scholar]

- Fannjiang, A.; Strohmer, T. The numerics of phase retrieval. Acta Numer. 2020, 29, 125–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Chi, Y. Modified Gerchberg-Saxton (G-S) Algorithm and Its Application. Entropy 2020, 22, 1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauschke, H.H.; Combettes, P.L.; Luke, D.R. Phase retrieval, error reduction algorithm, and Fienup variants: A view from convex optimization. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 2002, 19, 1334–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1 |

Note: can also have contribution from gravitational waves |

| 2 |

Note: Although wave packets are usually superposition of infinite number of eigenstates, here a generalised form is used where the particle’s momentum space distribution is superposition of number of arbitrary states. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).