1. Introduction

Philanthropy, also referred to as “passion for the human good,” has contributed to the development of societies. Since ancient civilisations, forms of mutual aid have favoured a more equitable social fabric (Bremner, 1988; Cunningham, 2016). However, it was in the industrial era that philanthropy took on systematic and structured roles (Owen, 1964; Rodgers, 1998). The contributions of philanthropists such as Andrew Carnegie (Nasaw, 2006) and John D. Rockefeller (Chernow, 1998) emphasised the importance of redistribution of wealth to promote the common good, including through donations and investments in education, culture, and innovation (Frumkin, 2003b). In recent years, philanthropy has evolved from purely charitable models to more structured and strategic ones. Today, philanthropy is no longer a simple act of generosity but a complex industry that interacts with public policies, businesses and especially non-profit organisations (Bishop & Green, 2008).

The greater value of philanthropy has increased attention to the effectiveness of interventions and the application of social impact assessment methods. Among them, “venture philanthropy” has become important, combining investment logic with social objectives to maximise the resources’ impact (John et al., 2013; Letts et al., 1997). This approach, like others, uses innovative measurement tools and unconventional financing models such as “social impact investing” (Bugg-Levine & Emerson, 2011; Nicholls et al., 2015).

The increased availability of statistical data also allows the use of advanced quantitative techniques to assess the effectiveness of philanthropic interventions, with a focus on measuring social capital and related economic growth (Katz & Page, 2014).

The Italian reality favours studies on the links between philanthropy and economic expansion due to its solid tradition of solidarity, also induced by widespread Christian morality (Vogt, 2002), often supported by institutionalised financial structures, such as banking foundations, which are fundamental for financing social charitable initiatives (Barbetta, 1998 & 2004). These institutions, established to balance wealth and social responsibility, have progressively evolved and have become leading actors in territorial development, social cohesion, and economic resilience, with funding for educational, cultural and inclusion programs (Anheier & Leat, 2006). However, the real verification of the impact of philanthropic activities on regional economic development requires an in-depth quantitative analysis based on econometric methods.

This study, therefore, aims to answer two fundamental questions:

The answer to these questions is entrusted to an econometric model applied to regional panel data: the possible relationships between GDP per capita (GDP) and social capital are examined using data relating to each territory. In particular, the study aims to test three hypotheses to evaluate the socioeconomic effectiveness of philanthropic initiatives.

(H1) Philanthropy strengthens social capital. The best empirical literature (Putnam, 2000; Andreoni, 1990) has already documented the positive correlation between prosocial activities, such as volunteering and donations, and the generation of social capital manifested through trust and social cohesion networks. These elements are endogenous variables fundamental to the systemic stability of community structures. Empirical evidence suggests that philanthropic initiatives act as catalysts for civic participation and a sense of belonging, contributing to the evolution of a social fabric characterised by greater equity and propensity for interpersonal collaboration. The quantitative measurement of these positive externalities can be quantified with social capital indices, such as the number of voluntary associations per capita and the degree of civic participation, which will be detected with standardised institutional opinion polls. This investigation verifies the validity of these assertions.

(H2) Social capital is a catalyst for regional economic growth. Guiso et al., in 2004, already highlighted positive correlations between social capital and economic efficiency. The latter contributes to the reduction of transactional costs and the increase in aggregate productivity. Therefore, the continuous and organised action of well-structured social networks is a fundamental facilitator for the optimal allocation of credit resources, the dissemination of information and coordination between economic agents, favouring an optimal environment for productive investments. Starting from these established doctrinal positions, in order to verify this second hypothesis, the present survey uses econometric models to quantify the impact of social capital on the regional gross domestic product per capita, incorporating in the analytical framework several control variables, including human capital indicators, the concentration of entrepreneurial activities and the territorial infrastructure endowment.

(H3) Philanthropic activities generate sustainable economic and social benefits. According to Salamon and Anheier (1997), the non-profit sector strengthens economic resilience, helping to make public resources more efficient and creating sustainable development. Integrating philanthropy and economic strategies can encourage inclusive growth that respects the environment. In this study, the verification of this hypothesis is entrusted to a fixed-effects regression model to evaluate the possible connection between philanthropic and regional spending and per capita income growth.

Therefore, this research aims to contribute to the academic and political debate on philanthropy as a factor of economic growth through empirical evidence and theoretical proposals to analyse the relationships between charity and socioeconomic well-being. Also, through the in-depth analysis of territorial dynamics and interactions between philanthropy and public policies, this study proposes new models of more equitable and efficient development based on a rigorous econometric methodology.

2. Literature Review

2.1. A First Bibliometric Approach

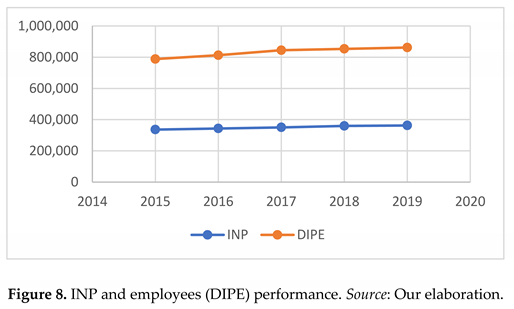

The subject matter of this study has not been adequately analysed in the best doctrine. In an exploratory survey on the Scopus platform in March 2025, using the following search string: “economic AND growth AND philanthropy,” only 125 documents produced in the last fifty years were found (

Figure 1).

In the last century, the topic has been substantially neglected. However, interest has been growing in the new millennium, albeit fluctuating. Overall, however, there is clear room for in-depth study, especially considering the pandemic and war challenges that have characterised recent years.

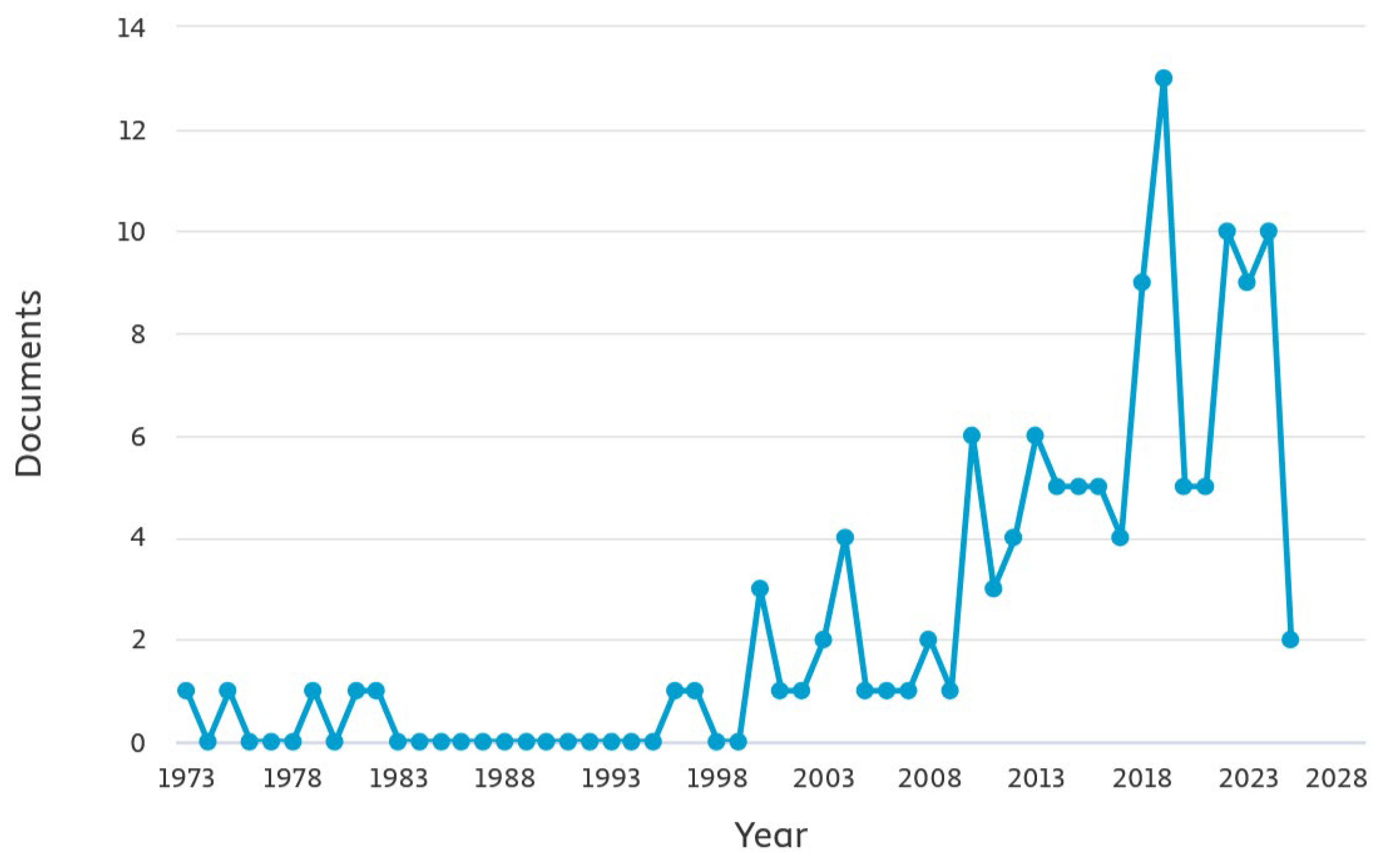

More in-depth research allows us to verify which disciplinary areas have been interested in the relationship between philanthropy and economic growth (

Figure 2).

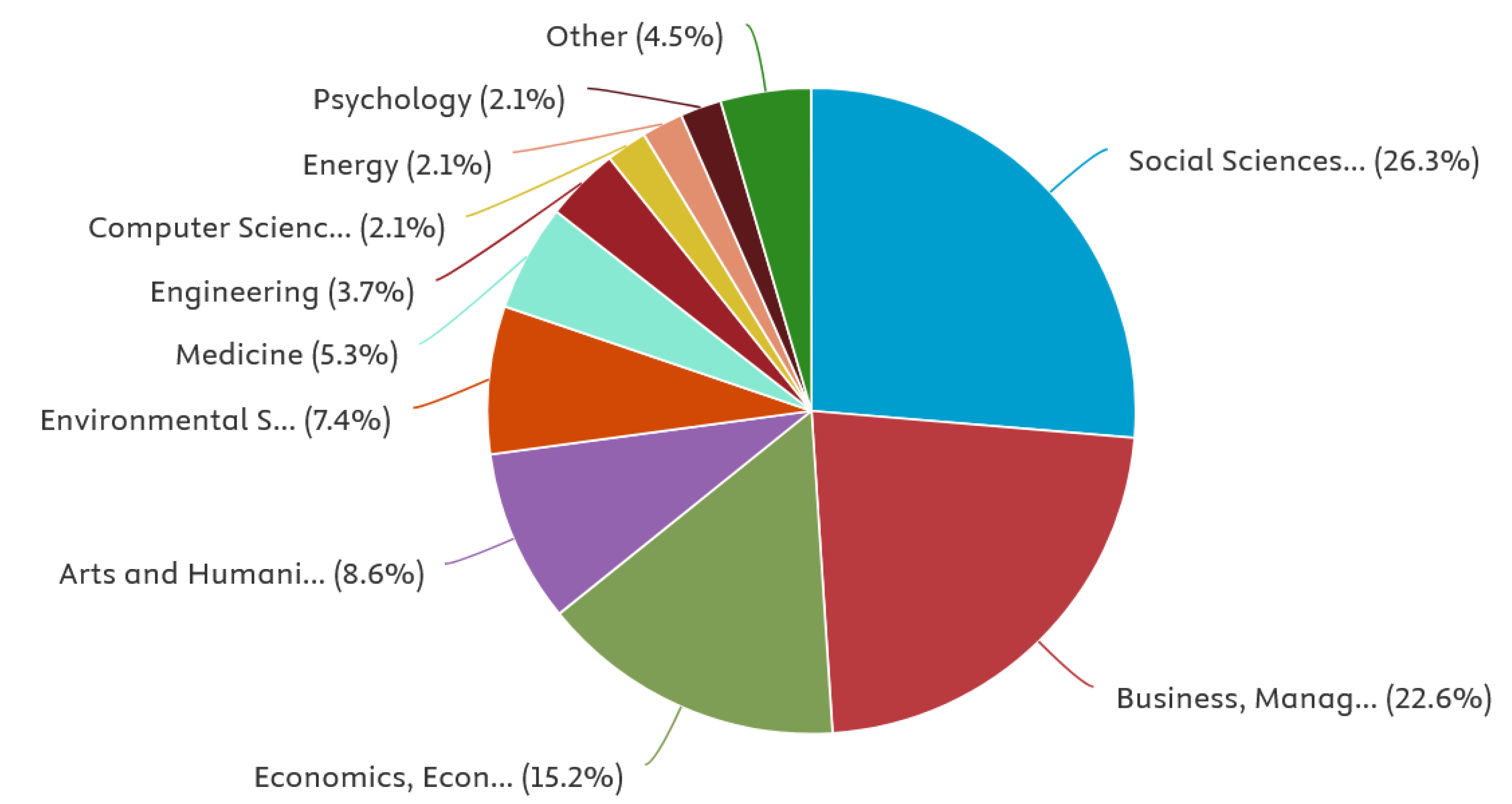

Therefore, the social sciences prevail, followed by the business economics disciplines. Relatively distant are the economic and econometric ones, which, instead, should have played a central role in the analysis of the relationships between philanthropic generosity and economic and social growth. There are only 37 documents indexed in Scopus relating to the “Economics, Econometrics and Finance” area, most of them concentrated in the last decade (

Figure 3), on which subsequent attention is developed because they are more relevant to the approach of this research.

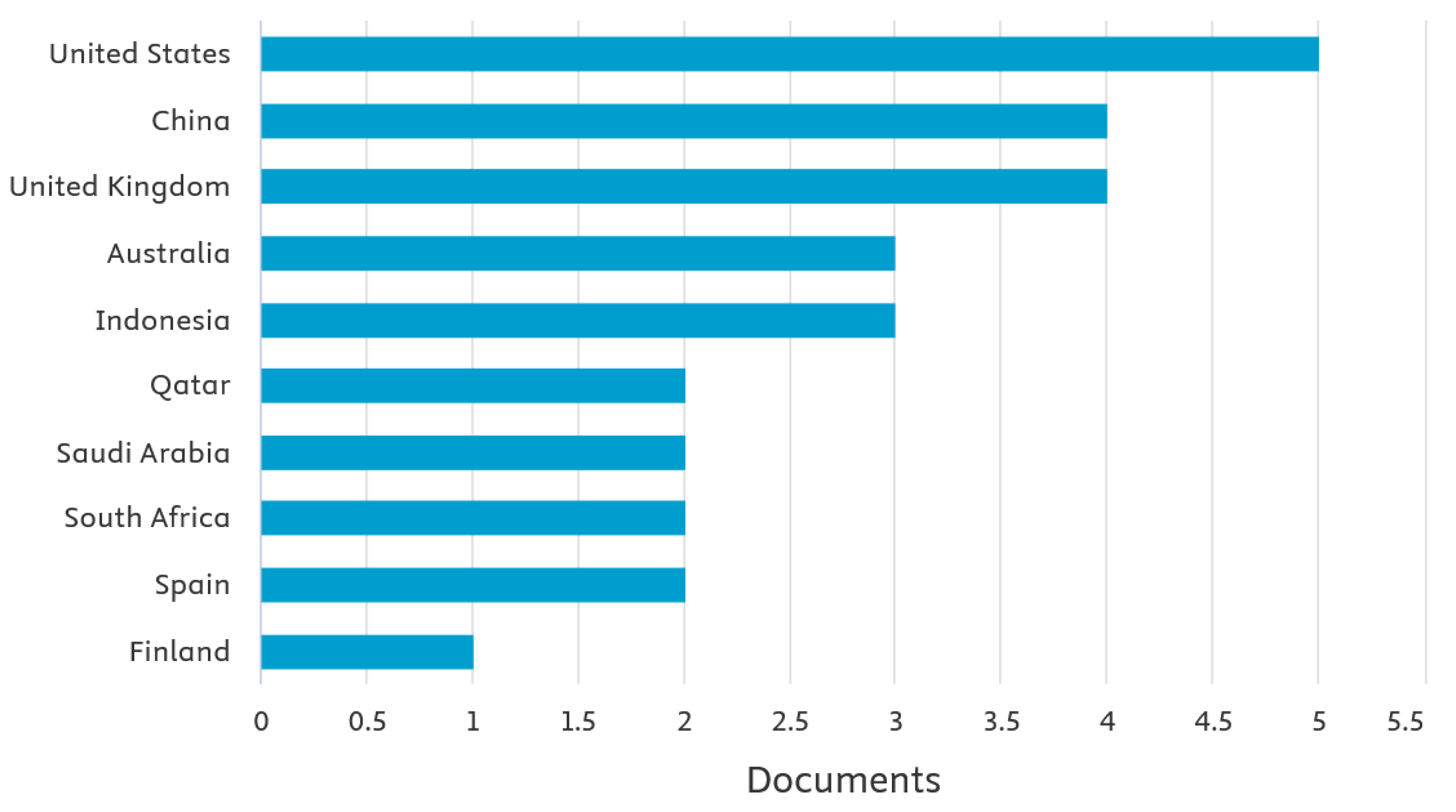

It is also interesting to locate the scientific production on the subject (

Figure 4).

Anglophone countries dominate, with surprising presences from China, Indonesia, and other nations, which, although with a modest number of contributions, signal the need to verify whether philanthropic actions can also induce greater economic and social well-being.

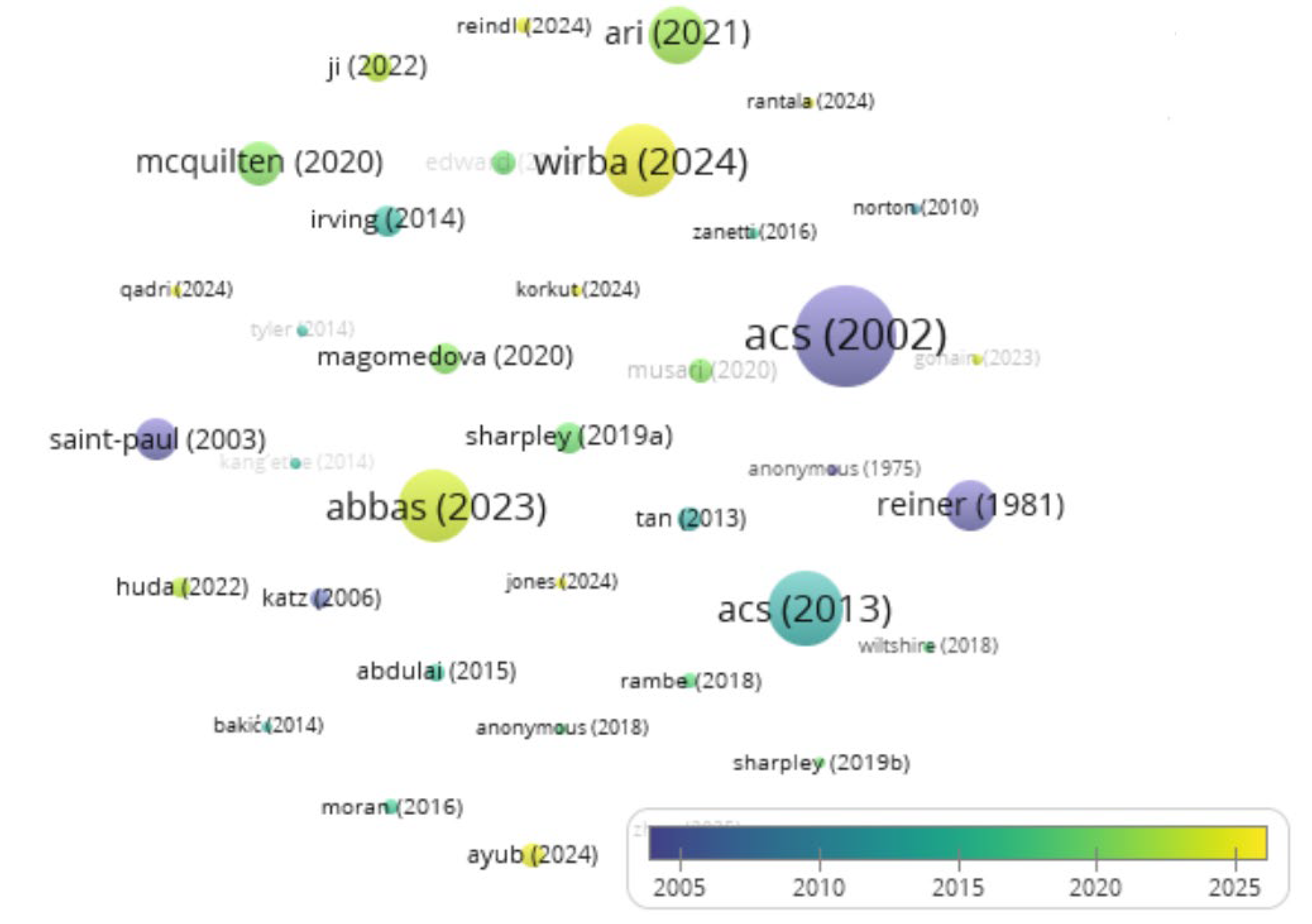

The most cited documents likely to have influenced subsequent studies are listed in

Table 1, identified with the first author’s surname and year of publication.

23 documents of the 37 surveyed had at least one citation. The first publication by ACS & Phillips (2002), which is dedicated to “Entrepreneurship and philanthropy in American capitalism,” a necessary cognitive step for any study on the subject, clearly dominates. One of the two authors, ACS, subsequently ventured, in 2013, to investigate the motivations, even hidden ones, of philanthropy, evaluating its effects on our economy. This document is the second most cited, although significantly distanced from the first. All the other, less-studied contributions follow.

The bibliographic framework is mapped in

Figure 5, in which the size of each node highlights the number of citations, and the colour refers to the year of publication.

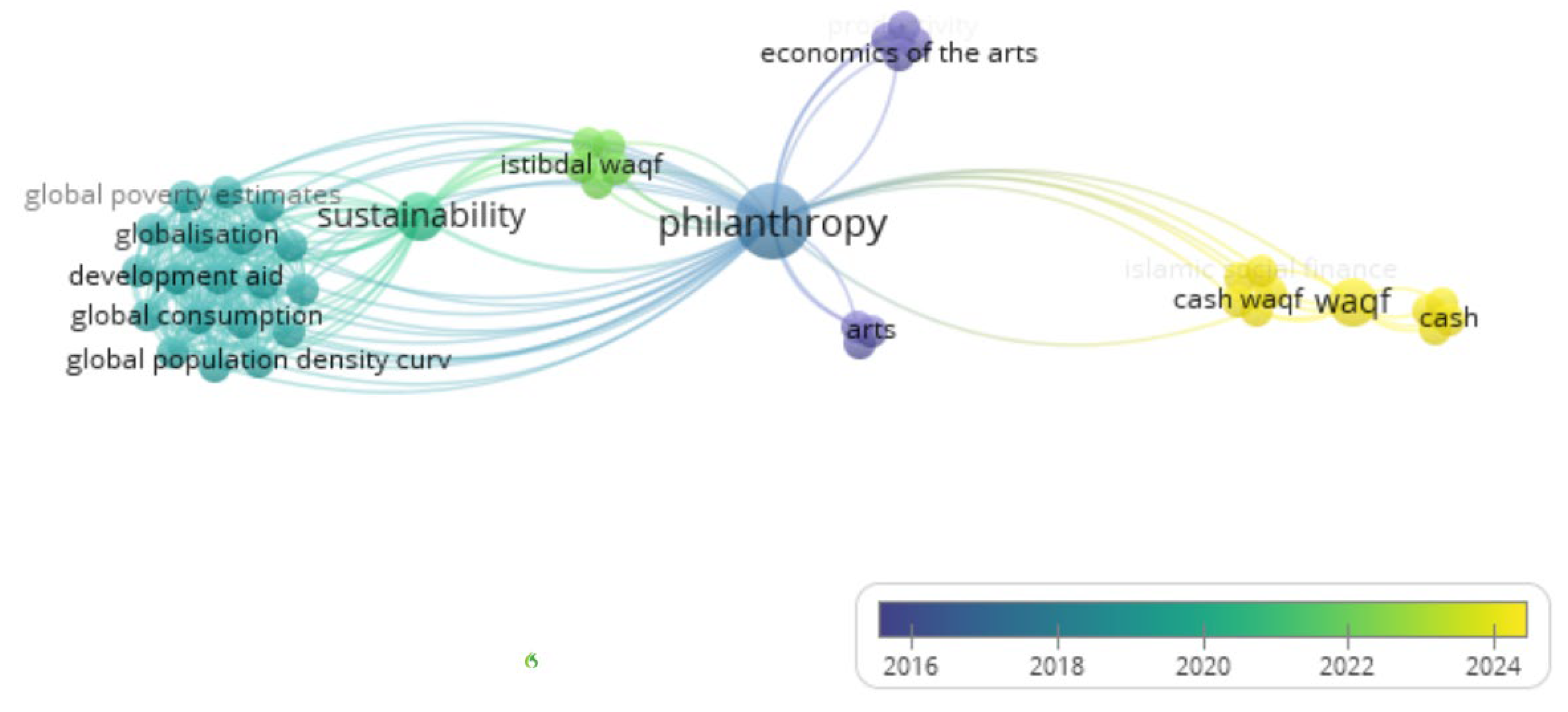

The keywords chosen by the authors usually provide the prevalence of the topics covered. The 28 most frequent among the 85 used are indicated in

Table 2 with the specification of the “Total Link Strength” (TLS), which is the sum of the “strength” of all the connections of a node. A node may have few links, but a high link strength if its ties to other nodes are significant

[1] (A high TLS value indicates, for example, that an article is highly connected and therefore has central relevance in the network.).

The connections between the keywords are mapped in

Figure 6: only 43 of the 85 are linked to each other.

Finally, the 16 primary sources that are most cited and willing to accept contributions related to the topic under analysis are listed (

Table 3).

No privileged source hosts studies on philanthropy’s economic impact in the international bibliographic panorama. The 37 different searches were found in 37 different sources. However, the impact on the scientific community has been considerably different. Linked to the journal Small Business Economics (ACS & Phillips, 2002), it has had the highest number of citations.

2.2. The Main Themes

The main contributions can be ranked according to their focus, allowing for the identification of at least three central themes that have characterised the scholarly literature.

2.2.1. Philanthropy and Social Capital

In the economic sphere, the concept of social capital has been mainly outlined by Bourdieu (1986) and Putnam (2000): it is the set of networks of relationships, trust and shared norms that facilitate cooperation in a community. According to Putnam, regions with high social capital also have greater innovation and economic growth capacity.

Other empirical studies have recently confirmed philanthropy’s importance in social capital construction. Ji & Lv (2022), for example, showed, with an econometric analysis in China, that corporate philanthropy improves trust and social cohesion, which are necessary for sustainable economic growth. Similarly, Zamagni (2005) has highlighted how, in Italy, banking foundations and other non-profit institutions help strengthen social capital, especially in economically backward areas.

Other recent quantitative studies have also analysed the correlation between the density of philanthropic organisations and increased civic participation, highlighting a significant positive effect. Reference may be made, for example, to the “IV Biennial Report on Volunteering” (ISFOL, 2011), which highlights the relationship between the presence of voluntary organisations and the increased collective awareness of the importance of volunteering in addressing social problems.

The “National Report on Volunteer Organizations surveyed by the CSV system” (CSVnet, 2015) also points out that volunteering absorbs 83.3% of the human resources of the non-profit sector in Italy, with over 4.7 million active volunteers: a greater presence of philanthropic organisations can encourage more active civic participation.

Finally, ISTAT’s “2023 Annual Report” analyses civic and political participation in various ways, indicating that the presence of philanthropic organisations can positively influence citizens’ civic engagement.

2.2.2. Philanthropy and Economic Growth

The economic literature has also analysed the connections between social capital and economic growth. First, Guiso et al. (2004) showed that regions with higher social participation also benefit from better economic efficiency and attractiveness for investment. Then Musari (2020) also analysed the role of Islamic microfinance in poverty reduction: ethical financing and philanthropy are practical tools for inclusive growth.

For the relationship between philanthropy and GDP, it is possible to refer to the aforementioned ISTAT 2023 Annual Report, which also highlights how philanthropy has a growing impact on economic development through integrating social services and strengthening human capital in local communities.

Reindl (2023) then examined the “creating shared value” model in Chinese and Austrian firms, concluding that strategic philanthropy can generate tangible economic benefits for companies and society. The integration of longitudinal data has made it possible to highlight the role of corporate donations in improving local economic efficiency.

Despite the valuable contributions of the doctrine, econometric models that analyse the relationships between regional GDP and philanthropic activities are necessary to deepen this relationship.

2.2.3. Philanthropy in the International Arena

In the United States, philanthropy has become strategic, with “venture philanthropy” achieved by combining entrepreneurial approaches and social goals (Frumkin, 2003a). Previously, Tyler (2021) analysed the role of social entrepreneurship in the United States, highlighting the positive effects on innovation and economic development of the combination of philanthropy and social impact investing.

In Europe, philanthropy is instead integrated with public policies (Salamon et al., 2014).

The extension of international econometric models compared the effects of philanthropy on national economies, showing significant variations based on the institutional context and governance strategies adopted.

For example, analysing the socioeconomic characteristics of donors and their social and professional networks has shown how cultural, institutional and political arrangements influence the development of philanthropy in different countries (Barman, 2017, as cited in “Why and How to Study Philanthropy”).

Structural equation (SEM) model-based approaches have, at the same time, isolated latent variables and improved understanding of philanthropic impact dynamics.

However, more integration between empirical studies and theoretical models is needed to refine methodologies for measuring philanthropic impact: machine learning can help predict the effectiveness of philanthropic initiatives in different economic contexts.

3. Materials and Methods

This work aims to analyse the relationship between regional economic growth and philanthropy in Italy, using econometric statistical methodologies to assess the impact of the non-profit sector on economic dynamics at the national and local levels. In particular, the study aims to:

To examine the distribution and diffusion of philanthropic institutions in the different Italian regions, with a focus on their contribution to local economies;

analyse the correlation between the growth of the non-profit sector and the regional GDP (gross domestic product), with specific attention to the territorial differences between Northern, Central and Southern Italy;

assess the effect of philanthropy on employment and social cohesion, with particular reference to its impact in policy areas such as education, health and social welfare.

The work is part of a context in which philanthropy is acquiring an increasingly central role as a lever for economic and social development. It contributes significantly to the creation of social capital and the reduction of territorial inequalities. Statistical analyses can offer helpful empirical evidence to confirm or refute these hypotheses and are based on theoretical foundations provided by previous studies concerning philanthropy and social capital (Putnam, 1993; Guiso et al., 2004; Calcagnini et al., 2016). The dataset used was quantitative (official source: ISTAT) from 2015 to 2019 (the years following the COVID-19 pandemic were not considered to avoid distortions related to its effects).

The main variables analysed in the study are:

Number of non-profit institutions by region, divided by sector of activity (culture, health, education, social assistance, economic development, volunteering);

Number of employees in the non-profit sector in order to estimate their impact on the labour market;

Regional economic indicators, such as GDP per capita and economic growth rate;

Socioeconomic variables include volunteer participation rate, crime index, and a measure of social capital (Guiso et al., 2004).

The survey on philanthropic realities was conducted on a regional basis, with a further aggregation into macro-areas (North, Centre, South) to highlight territorial dynamics and control regional heterogeneity, as well as the specific effects of each geographical area. Especially:

the change in GDP per capita indicates the regional economic trend over time;

the variable “Volunteering” represents the number of citizens active in volunteering initiatives in each region;

the share capital is expressed through an index developed at the regional level;

the variables Crime and Education are measured in percentage terms.

The topic of philanthropy and its growing diffusion within the Italian economic landscape represents a relatively recent but rapidly expanding field that is also arousing considerable interest in the academic context. In this context, the principles and beliefs that inspire philanthropic action were highlighted due to what happened during the COVID-19 pandemic, where the awareness emerged even more that human beings were going in a direction that was too selfish and disrespectful of the surrounding nature. The real challenge could, therefore, lie in the ability to renew organisational systems, enhance human resources and adopt a more sustainable and responsible approach to entrepreneurship. This paradigm shift could represent a crucial step in transforming organisations and improving governance models.

In order to understand whether awareness of the importance of philanthropic initiatives for the country’s development is widespread among entrepreneurs and managers, an empirical survey was conducted to photograph the current situation and identify possible evolutionary trajectories in the Italian context.

4. Descriptive Econometric Analyses

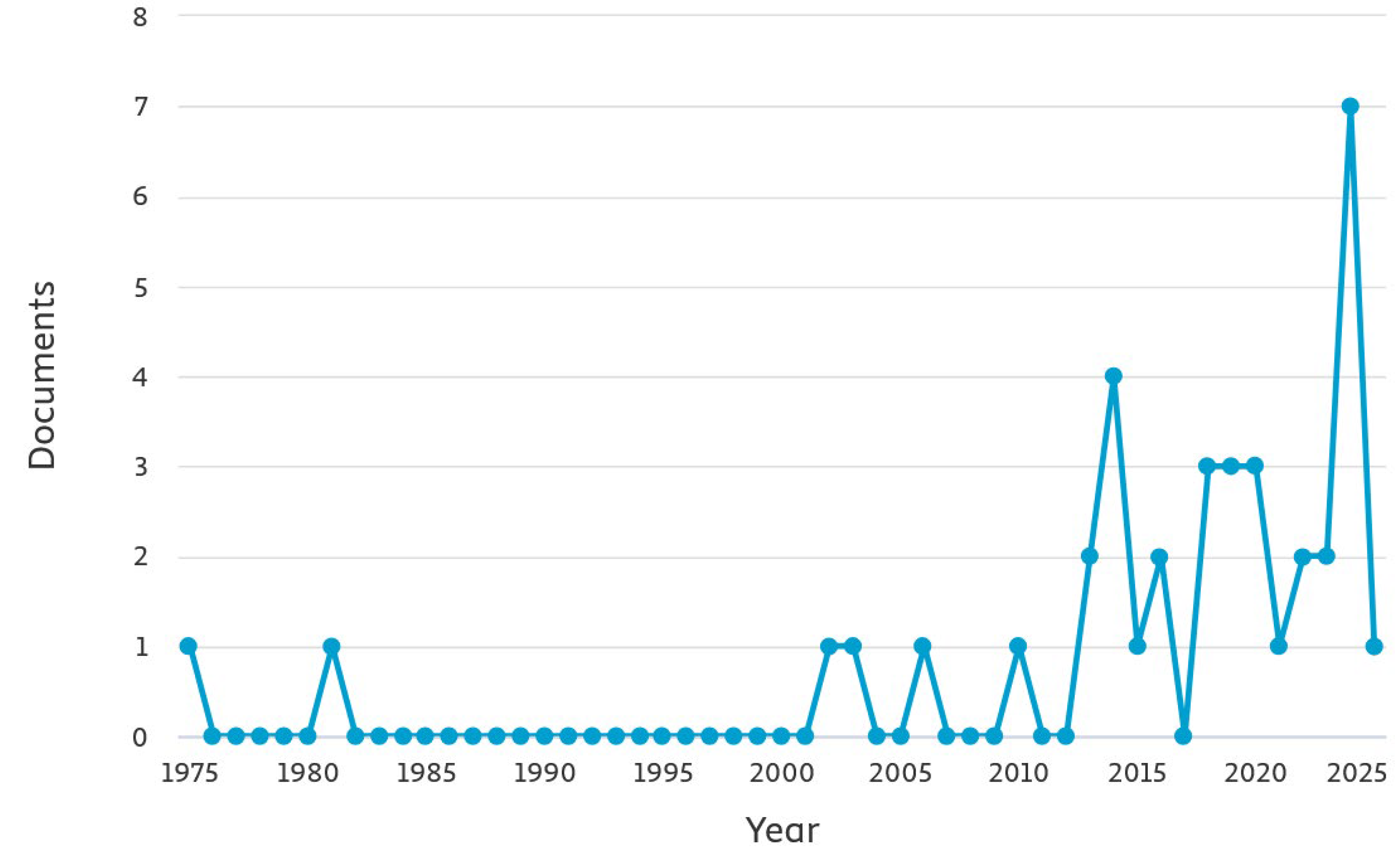

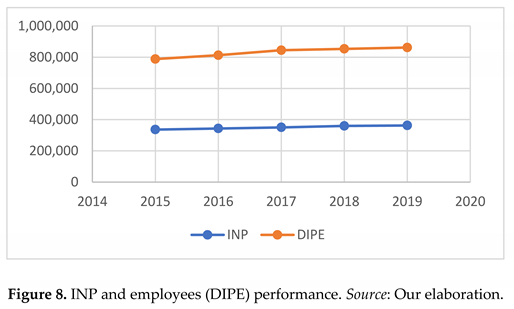

Table 4 shows (in the five years considered) the numbers of non-profit institutions (NPIs) in absolute value, broken down by region and with the addition of the two autonomous provinces of Trento and Bolzano and the aggregate data by macro-areas, North, Centre, South and Islands. As can be seen from the data, in the period 2015-2019, the NPIs in Italy grew in number (it was found that one in 5 institutions was established in this period). If we look at the Istat Permanent Census of NPIs, employees have also grown to a greater extent precisely in the sectors of philanthropy and promotion of volunteering (+12.2%). In particular, from

Table 5 (which shows the data relating to the INPs and their respective employees), we observe that since 2015, the INPs have grown by 8.1% and the employees by 10.4%. Between 2018 and 2019, NPIs grew by 0.9%, less than what was recorded between 2017 and 2018 (which recorded an increase of 2.6%), while the growth in the number of employees was slight and remained around 1% in both years (Source: ISTAT).

The NPIs have a concentrated territorial distribution since over 50% are active in the North, 22.2% in the Centre and 8.2% and 9.4% respectively in the South and the Islands. The territorial concentration is even more evident concerning employees because 57.2% are employed in the northern regions against 20% in the South. If we look specifically at the philanthropy and volunteer promotion sector, the percentage of this component with volunteers presents a figure of 84.6%, higher than the national one, 72.1% (Source: ISTAT).

An aggregate analysis by regional macro-areas is proposed in

Table 6, where the index numbers with a fixed base for 2015 have been calculated to highlight the phenomenon’s overall growth.

From the data, it can be seen that in the South, there is a more sudden increase in the phenomenon, an indication of the fact that the development of philanthropic activities in areas with more fragile socioeconomic conditions (Felice, 2007 and 2016; Gabrielli and Lee, 2009) is a symptom of a less efficient public administration, and/or even of southern populations likely to be more inclined to generosity (Placanica, 1998).

Table 7 shows the main descriptive statistics for NPIs by region.

Data distributions are symmetrical overall and are little affected by anomalous data. The means and medians have a marginal difference, and the interval ranges (difference between maximum and minimum) do not have high values. The driving regions for the North (which has the most significant number of non-profit institutions) are Liguria, Veneto and Piedmont. In the South and the Islands (which have greater variability in the data), the regions with the most relevant data are Sicily and Campania, while Molise and Basilicata presented the smallest values overall.

Table 8 shows the percentage distribution of companies in the various sectors identified by macro-areas with the relative values of employees. In particular, the twelve sectors in which non-profit organisations operate are culture, sport and recreation; education and research; health; social assistance and civil protection; environment; economic development and social cohesion; protection of rights and political activity; philanthropy and promotion of volunteering; international cooperation and solidarity; religion; trade union relations and representation of interests; other activities.

The culture, sport and recreation sector involves most non-profit institutions in all three geographical areas, with values ranging from 61% to 65% approximately. This figure reflects Italy’s leading role in the world regarding artistic and cultural heritage, allowing it to access funding from international bodies to enhance and promote its cultural riches, thus constituting a significant source of economic income. Organisations operating in the sports and recreational field also fall within the same scope. As can be seen from the data and for the three geographical areas, the second group of activities carried out by philanthropic entities is represented by social assistance and civil protection, with values ranging around 10%. Next, the other non-profit activities with high percentages are the sectors of trade union relations and representation, religion education and research. The lowest percentage values correspond with international cooperation and solidarity, philanthropy and promotion of volunteering, protection of rights and political activity, economic development and social cohesion, and the environment.

Employees are concentrated in a few sectors. In a decreasing sense, social assistance, health, education and research, economic development, and social cohesion. The remaining sectors have few employees, proportionating to fewer initiatives.

5. Regional Economic Growth and Philanthropy: Relationships?

In this section, we want to evaluate the relationship between regional economic growth and philanthropy in Italy. To this end, the ISTAT source dataset reported in the Appendix was considered, containing each Italian region, identified with an “id” and, for the 2015-2019 interval, nine variables representing the GDP per capita, an indicator of political participation, the number of volunteers and the religious presence per capita, the mortality and crime rate as a percentage, the per capita unemployment rate, the number of economic establishments and the resident population.

Since these are panel observations over several years and several (longitudinal) regions, we proceeded to estimate an unconditional fixed effects model (FEM):

yit=αi+βxit+ϵit

It wants to analyse the effect of philanthropy on the gross domestic product per capita by checking for the Italian region. This means that in these models, a global intercept is not considered because the data are centred by eliminating the average of each group (region) before proceeding with the estimates: it is as if each region, in order to maintain its characteristics, had its intercept which, however, is not shown in the output. The software for the analysis is RStudio; the variable GDP per capita (also calculated in its logarithmic version) is suitable as a dependent variable for estimating economic growth. The independent variable is a measure of philanthropy chosen from one or more variables in the dataset (e.g., the number of volunteers per capita, the presence of religious bodies, etc.).

The estimation of the first fixed-effects model, using GDP per capita as a dependent variable and volunteering and the presence of religious bodies as explanations, does not show a significant relationship with economic growth (measured both as GDP per capita and as a log of GDP per capita) in the Italian regions. The values associated with the tests for the coefficients of the two explanatory variables are very high (respectively for VOLpro 0.68 and RELpro 0.36).

Unfortunately, using other variables such as unemployment per capita, crimes per 100 inhabitants, and the mortality rate does not lead to similar results (the condition number is very high and suggests multicollinearity problems between them). Moreover, selecting the explanatory variables that best explain GDP per capita using a stepwise regression (MA) also led to the same results.

Consequently, a comparison was made between the model with fixed effects and the model with random effects to establish whether the former is more appropriate than the latter through the Hausman test, which, with a p-value almost close to 1, does not allow to reject the null hypothesis. Therefore, a random effects model would be appropriate (which allows an assessment of the relationship between variables over time and considers the regions’ diversity).

The estimation of this model (

Table 9) leads to a determination index that explains 40% of the model.

Most of the variance is intra-individual (79%), so variation over time within regions is predominant over differences between regions. Volunteering has a positive and highly significant impact on GDP per capita. The interception is significant, and the variable linked to the contribution of religious communities is borderline. However, if you eliminate this variable, the model improves significantly.

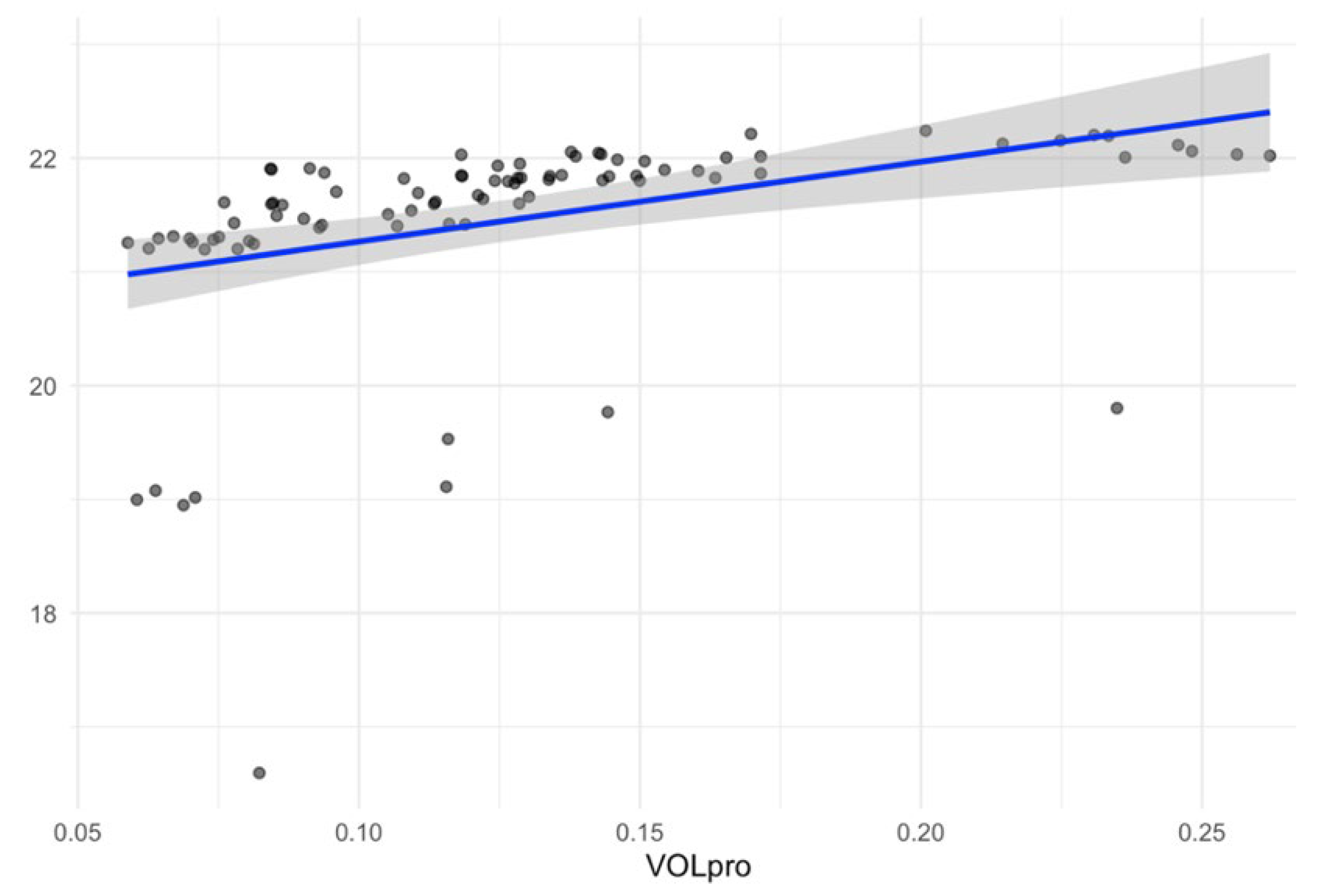

From a descriptive point of view, in support of the inferential results, the graph of the relationship between the number of volunteers and the logarithm of GDP per capita (

Figure 7) is shown (correlation coefficient equal to 0.38).

This confirms that regions with many volunteers also have a high GDP per capita. However, the fact that the points are not entirely close to the regression line indicates the presence of territories for which this is not the case.

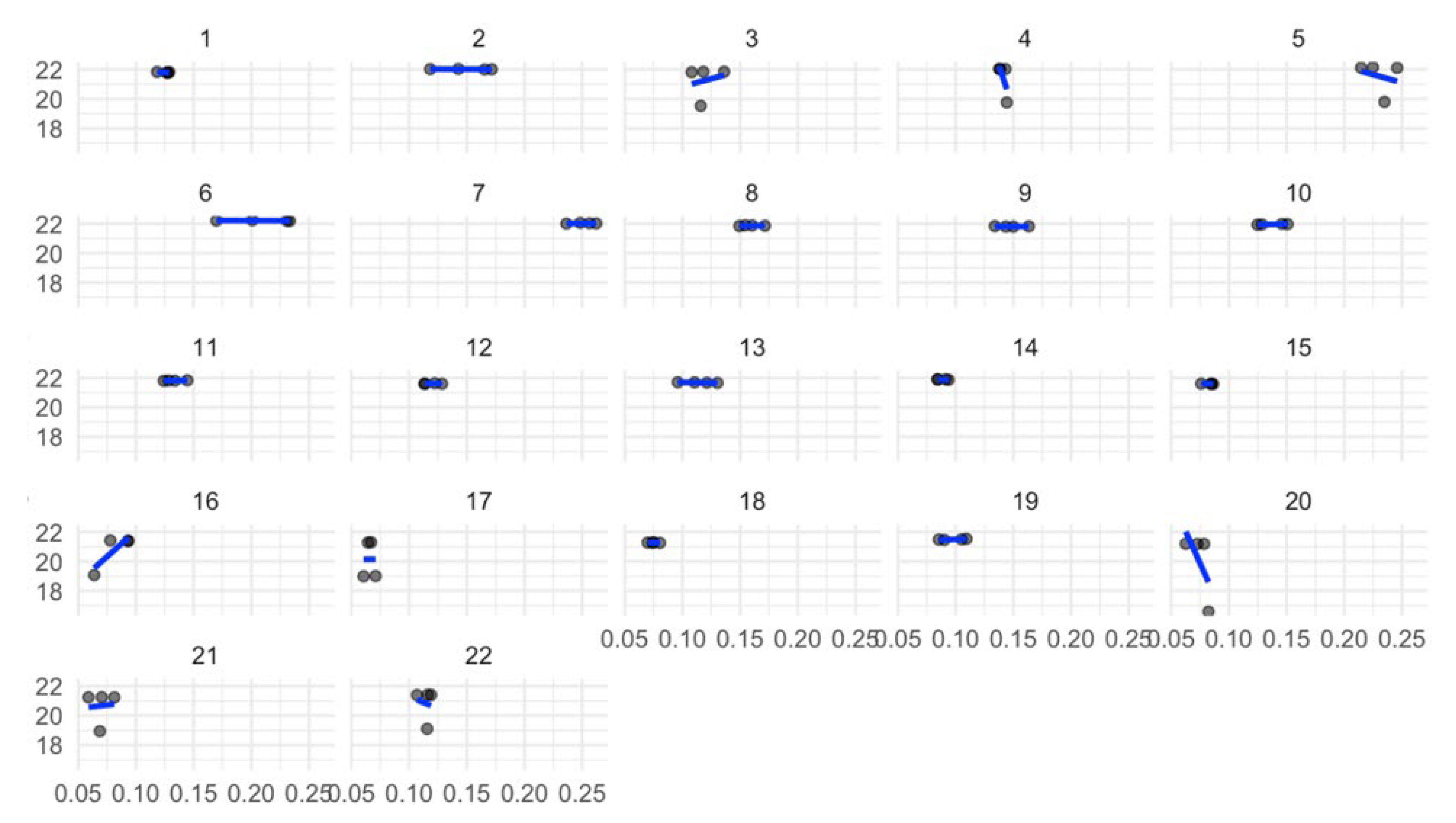

Figure 8 also shows the graph (faceted) where each box represents an Italian region with a regression analysis between the variables GDP per capita (logarithm) and number of volunteers.

There is no uniform relationship between these two variables across all Italian regions; the association depends on the specific local context. Volunteering appears to be more positively correlated with GDP in certain northern areas; however, some regions, such as Lombardy, despite exhibiting high GDP levels, do not show a higher-than-average number of volunteers.

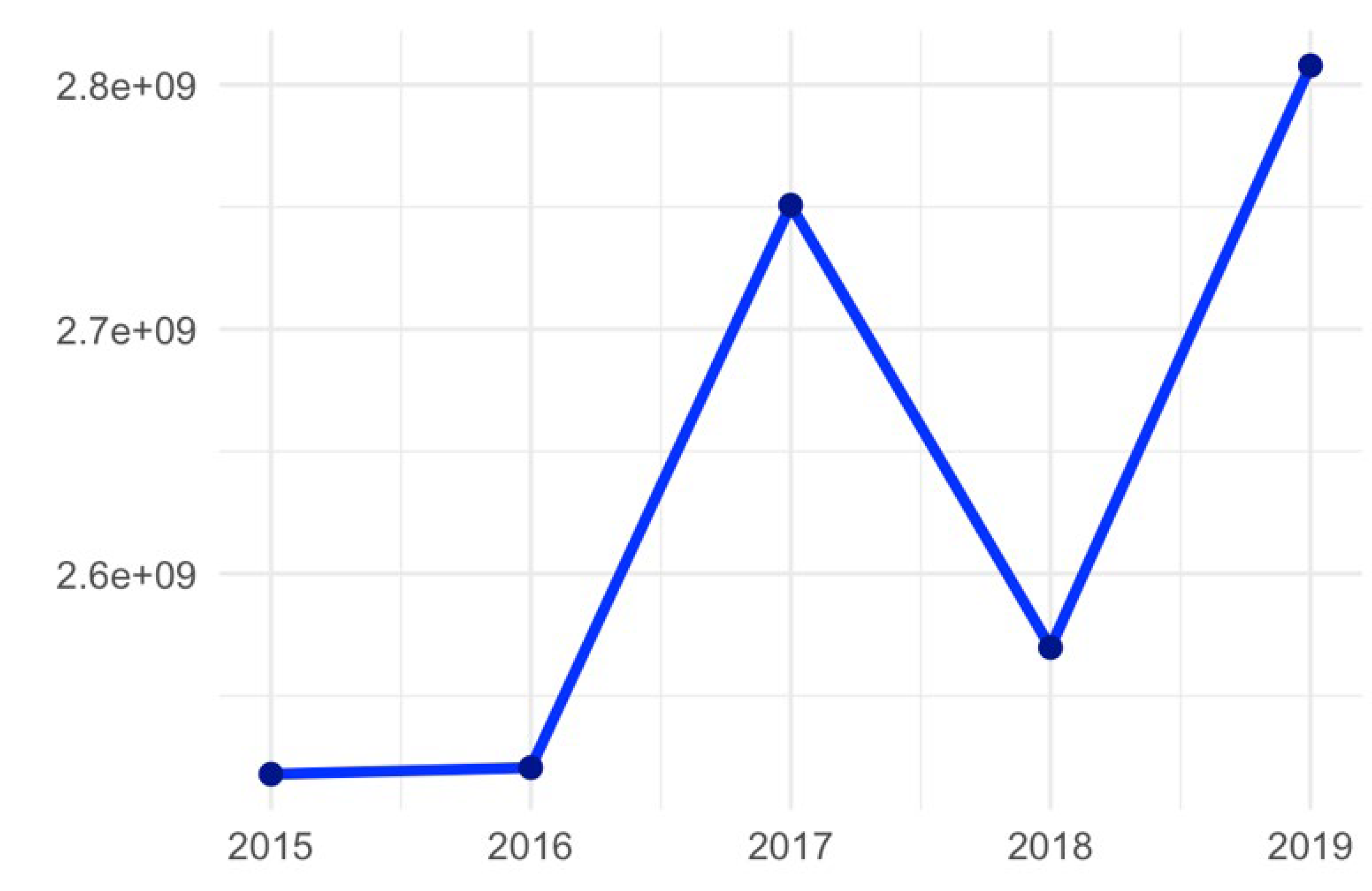

A fixed effects estimate of the GDP per capita growth rate compared to its lagged version of one unit of time has also been made. The coefficient estimate (-0.25870) with the relative standard error (0.10393) is reported. The negative sign of the coefficient estimate may seem counterintuitive, but it indicates that from an economic point of view, there has been a “rebound” effect (e.g., after a high or low GDP, the variable tends to decrease or increase). An analysis of the average GDP per capita in the time interval considered shows its stability at the turn of the two years 2015-2016 and then has an increasing fluctuating trend in the following three-year period up to 2019 (

Figure 9).

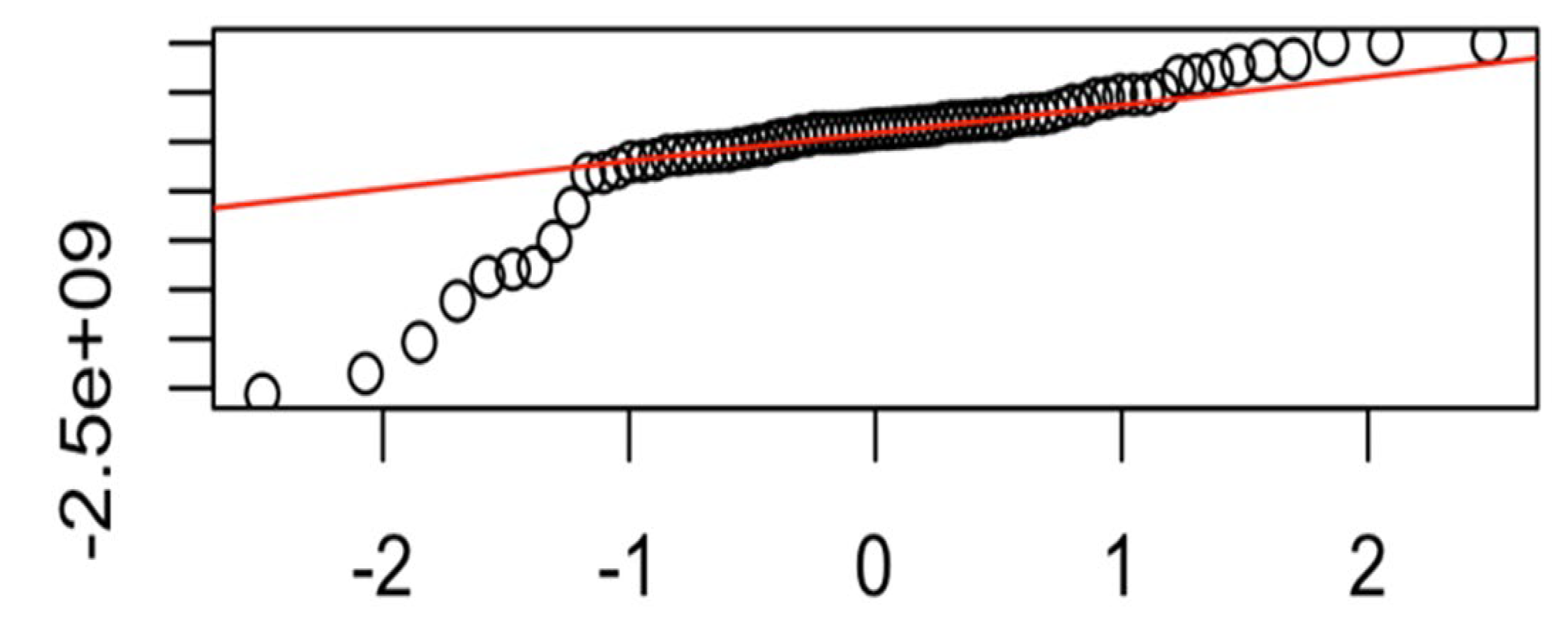

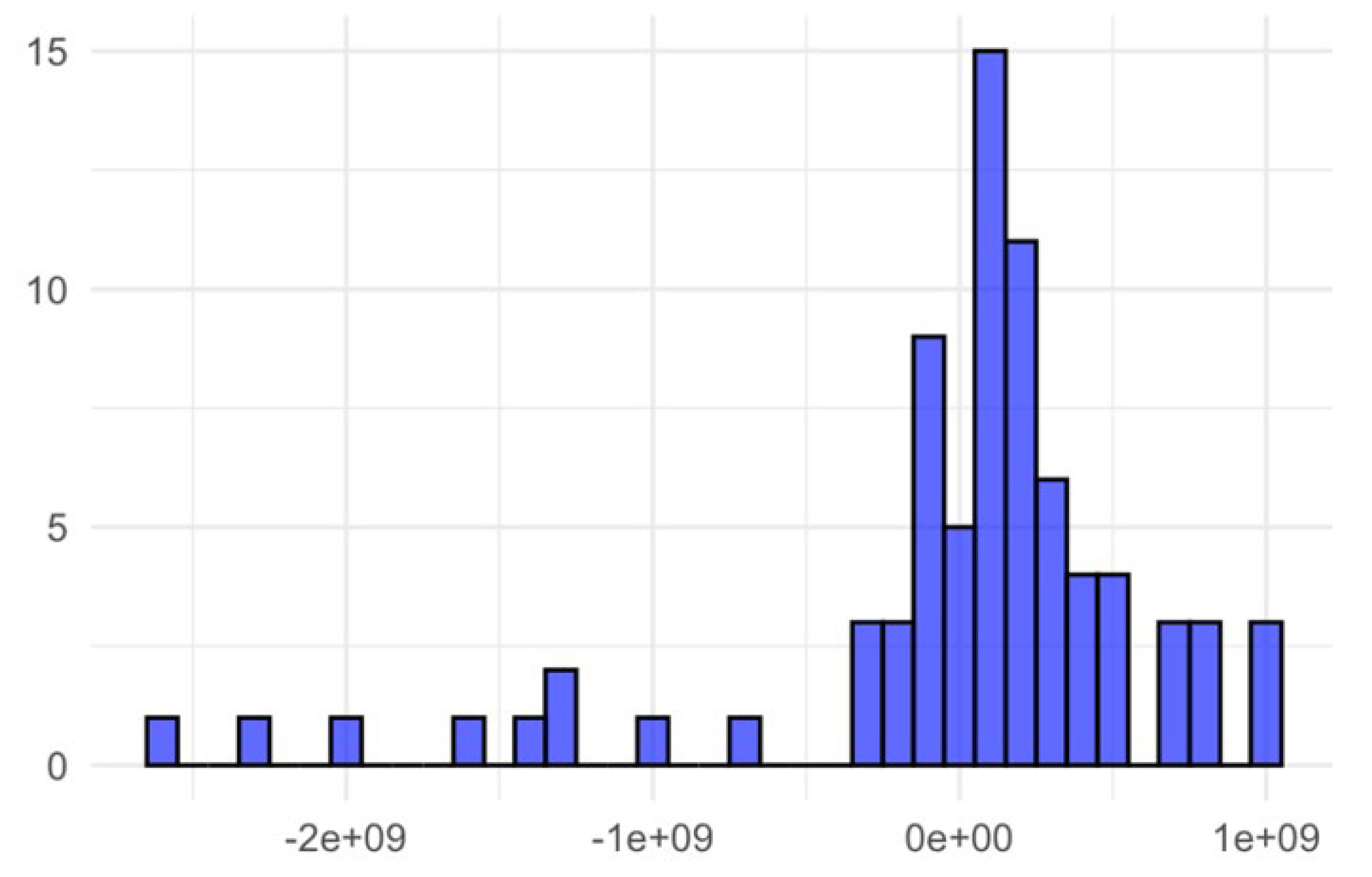

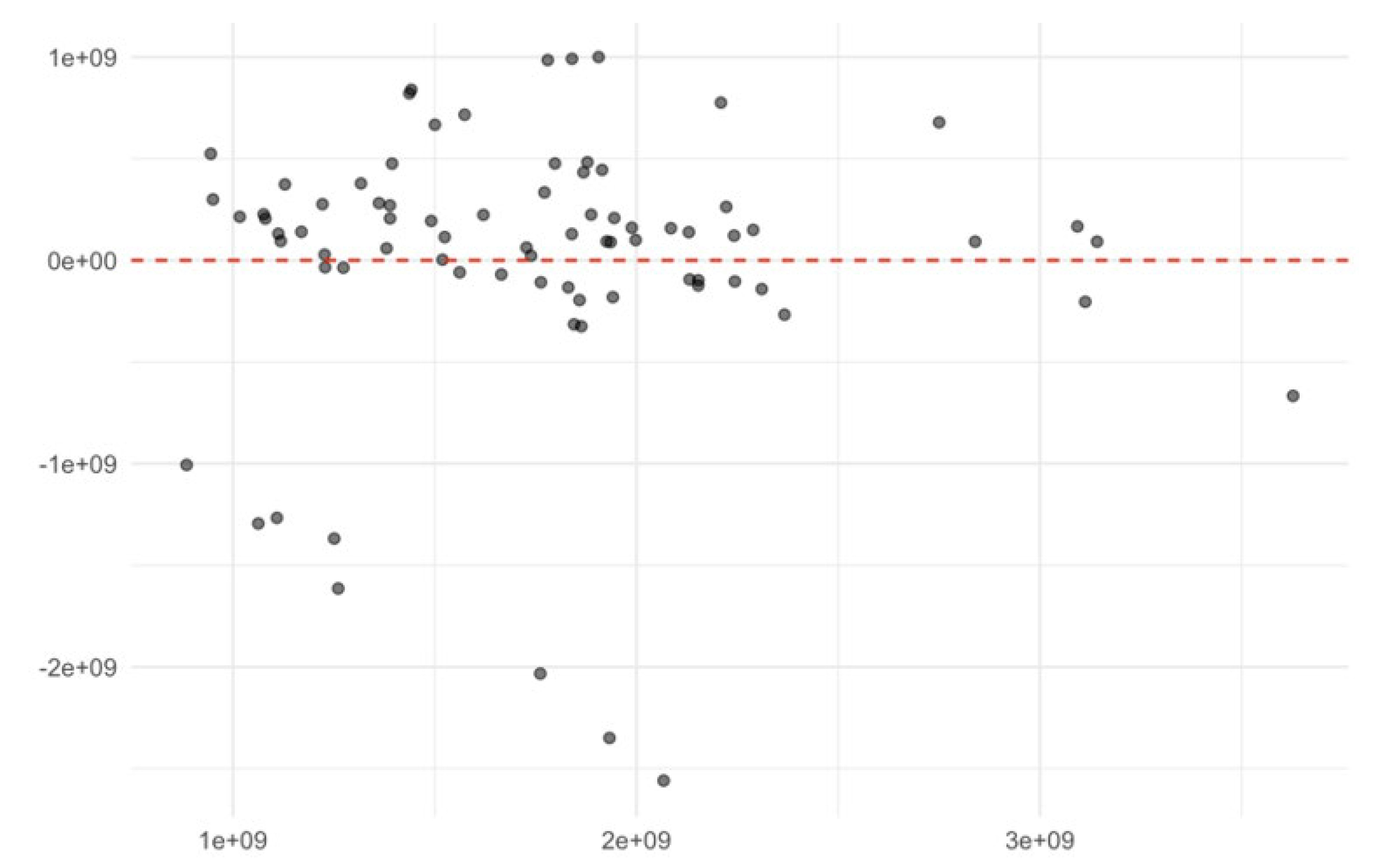

The analysis of residues leads to comforting results on the choice of model. The Breusch-Pagan test, which is used to verify the presence of heteroskedasticity in the residues, has a p-value of 0.71; therefore, robust models are not required. Even the Wooldridge test (which is used to verify whether the residues of a regression model in the panel data are correlated with each other over time) allows us to affirm that the observations do not depend on the error value of those that precede them (p-value equal to 0.8561). However, the normality of the residuals is violated (p-value equal to 5.341e-09). These results are confirmed by Figure 10,

Figure 11 and

Figure 12, which show residuals that deviate from the normal distribution, especially in tails (see the comparison between sample quantiles with those of a normal distribution).

The histogram presents clusters in the initial part (probably regions with distant behaviour from the others). Finally, their distribution appears random around the null value except for a few points that could indicate the presence of outliers.

Therefore, Social capital is a decisive element for economic growth and a component of philanthropy, which can be considered a driving force.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

The results confirm the evidence of Guiso et al. (2004) on the role of social capital in economic growth. They also align with studies by Salamon and Anheier (1997), which emphasise the non-profit sector’s contribution to economic resilience.

Guiso et al. (2004) showed that social capital determines economic growth. Social capital, defined as trust between individuals and the ability to cooperate within a community, fosters economic development because it reduces transaction costs, facilitates access to credit, and promotes productivity.

This study has results compatible with this theory, namely that social capital is a fundamental channel through which philanthropy can positively impact economic growth.

Salamon and Anheier (1997) focused on the non-profit sector’s role and highlighted how it contributes to economic resilience. Economic resilience is the ability of an economic system to adapt and recover from adverse shocks. The two authors suggested that non-profits and philanthropic activities play a stabilising role in modern economies. The results of the proposed econometric analysis now confirm this idea, showing that philanthropy has a long-term effect on the stability and growth of regional economies.

Empirical evidence reinforces the theoretical model that philanthropy can catalyse economic growth by strengthening social networks and increasing interpersonal trust. The results confirm that private donations and investments in the non-profit sector create a virtuous circle in which economic growth and social capital mutually reinforce. In particular, the analysis showed that the increase in donations not only stimulates direct economic development but also fosters the creation of a more cohesive social environment, facilitating access to credit and improving the efficiency of local markets.

However, some critical issues emerge that deserve attention. First, the effect of philanthropy on economic growth is more significant in areas with more established institutions and effective governance, suggesting that the institutional environment plays a key role in determining the impact of philanthropic investments. In addition, the regional differences highlighted by the analysis raise questions about philanthropy’s ability to generate a homogeneous impact on a national scale. Some previous studies (Knack & Keefer, 1997; Alesina & La Ferrara, 2002) have already pointed out that social capital and interpersonal trust can vary significantly between regions, influencing philanthropy’s ability to generate economic growth.

Therefore, although philanthropy emerges as an effective tool for economic development, its success depends on some structural and institutional factors. These findings suggest the need for closer integration between public policies and philanthropic initiatives to amplify positive effects and mitigate regional inequalities in economic impact.

The empirical results confirm the study’s starting hypothesis: philanthropy positively impacts regional economic growth, mediated by social capital. However, regional differences indicate that the effectiveness of philanthropy depends on the quality of the institutional and social context. This result is consistent with the evidence of Knack and Keefer (1997), who demonstrate that social capital is a key element for sustainable economic growth, and with the research of Alesina and La Ferrara (2002), which underline the influence of interpersonal trust on productive investments.

The implications for economic policy suggest that governments should incentivise donations and public-private partnerships to maximise positive effects. In particular, tax incentive policies for philanthropy could further strengthen its impact, as evidenced by previous studies (Andreoni, 2006; Bekkers & Wiepking, 2011). Moreover, the involvement of the private sector in philanthropic initiatives may generate synergies with public investments, thereby enhancing the effectiveness of local economic development policies.

A further critical aspect concerns the measurement of social capital, which still represents a challenge for economists. The difficulty of obtaining reliable quantitative data could affect the accuracy of econometric estimates, as Durlauf and Fafchamps (2005) pointed out. In addition, the potential endogeneity problem between philanthropy and economic growth requires further methodological insights, with the application of advanced techniques, such as more robust instrumental variable models and the use of machine learning-based approaches to improve the predictivity of analyses.

Future research could also explore the role of digitalisation in philanthropy and social capital. With the increasing prevalence of crowdfunding platforms and digital social impact initiatives (Katz & Ronfeldt, 2018), there is an opportunity to study how technology can amplify the positive effects of philanthropy on economic growth and social cohesion.

Methodologically, it is desirable in the future to use multilevel models (regions nested in macro-areas).

In addition, the comparative analysis with other countries could provide further empirical evidence on the validity of the results observed at the Italian level.

Author Contributions

The article results from collaboration between the two authors. However, assigning paragraphs concerning the work carried out mainly by each is possible. Guido Migliaccio introduced the topic and edited the bibliographic review, drawing up the discussion and conclusions. Consequently, the paragraphs “Introduction,” “Review of the literature,” and “Discussion and Conclusions” are to be assigned to him. Simona Pacillo, on the other hand, processed the data and drafted the related observations. The other paragraphs are, therefore, her. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data used as their primary source is the Istat website, from which the variables shown in the Appendix table were retrieved and aggregated.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Diletta Migliaccio for her valuable input and collaboration in collecting and processing the data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open-access journals |

| TLA |

Three letter acronym |

| LD |

Linear dichroism |

References

- Acs, Z. J. (2013). Why Philanthropy Matters: How the Wealthy Give, and What It Means for Our Economic Well-Being. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Acs, Z. J., & Phillips, R. J. (2002). Entrepreneurship and philanthropy in American capitalism. Small Business Economics, 19(3), 189–204. [CrossRef]

- Alesina, A., & La Ferrara, E. (2002). Who trusts others? Journal of Public Economics, 85(2), 207-234. [CrossRef]

- Andreoni, J. (1990). Impure Altruism and Donations to Public Goods: A Theory of Warm-Glow Giving. The Economic Journal, 100(401), 464–477. [CrossRef]

- Andreoni, J. (2006). Philanthropy. In S.-C. Kolm & J. Mercier-Ythier (Eds.), Handbook of the Economics of Giving, Altruism and Reciprocity (Vol. 2, pp. 1201-1269). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Anheier, H. K. , & Leat, D. (2006). Creative Philanthropy: Toward a New Philanthropy for the Twenty-First Century. London, UK: Routledge.

- Arellano, M., & Bond, S. (1991). Some Tests of Specification for Panel Data: Monte Carlo Evidence and an Application to Employment Equations. The Review of Economic Studies, 58(2), 277-297. [CrossRef]

- Baltagi, B. H. (2008). Econometric Analysis of Panel Data. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

- Baratta, L. (2020). Promemoria per i sovranisti: senza gli immigrati il nostro Pil calerebbe a picco. Available online: https://www.linkiesta.it/2020/02/immigrati-fondazione-di-vittorio-pil/.

- Barbetta, G. P. (1998). Le fondazioni bancarie in Italia. Bologna, Italia: Il Mulino.

- Barbetta, G. P. (2004). Le fondazioni bancarie: dall’assistenza allo sviluppo locale. Bologna, Italia: Il Mulino.

- Becattini, G. (2014). Sport e società: dalla competizione alla corruzione. Il Ponte, 70(3), 44-45.

- Bekkers, R. , & Wiepking, P. (2011). A literature review of empirical studies of philanthropy: Eight mechanisms that drive charitable giving. Non-profit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly. [CrossRef]

- Benacchio, G. A. (2015). Lo sport e il dialogo sociale in Europa. Informator, 22(3), 90-94.

- Bishop, M., & Green, M. (2008). Philanthrocapitalism: How Giving Can Save the World. New York, NY: Bloomsbury Press.

- Boonen, J. T., & Li, H. (2017). Modeling and forecasting mortality with economic growth: a multi-population approach. Demography, 54, 1921-1946. [CrossRef]

- Bordogna, L., & Pedersini, R. (2019). Relazioni industriali. L’esperienza italiana nel contesto internazionale. Bologna, Italia: Il Mulino.

- Bourdieu, P. (1986). The Forms of Capital. In J. G. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education (pp. 241–258). Westport, CT: Greenwood.

- Bremner, R. H. (1988). American Philanthropy. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Bugg-Levine, A., & Emerson, J. (2011). Impact Investing: Transforming How We Make Money While Making a Difference. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Calcagnini, G., Giombini, G., & Perugini, F. (2016). Bank Foundations, Social Capital, and the Growth of Italian Provinces. Working paper no. 131. Available online: http://docs.dises.univpm.it/web/quaderni/pdfmofir/Mofir131.pdf.

- Carnegie, A. (1889). The Gospel of Wealth. North American Review, 148(391), 653–664.

- Celant, A. (1994). Geografia degli squilibri: I fattori economici e territoriali nella formazione e nell’andamento dei divari regionali in Italia. Roma, Italia: Kappa.

- Chernow, R. (1998). Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr. New York, NY: Penguin Press.

- CSVnet (2015). Report Nazionale sulle Organizzazioni di Volontariato censite dal sistema dei CSV. Roma: Fondazione IBM Italia. Available online: https://www.volontariatotrentino.it/sites/default/files/download/Report%20delle%20organizzazioni%20di%20volontariato.pdf.

- Cunningham, H. (2016). Philanthropy and Charity in the Past: A Historical Perspective. London, UK: Taylor & Francis.

- D’Alessandro, V. (1999). La sfida dell’istruzione. Modernizzazione e formazione nella società italiana. Roma, Italia: Carocci.

- D’Ascanio, V. (2018). La polisemia della performance. L’istruzione superiore e la società della conoscenza. Roma, Italia: Anicia.

- Davidson, R., & MacKinnon, J. G. (2004). Econometric Theory and Methods. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- De Vincenti, C., Finocchi Ghersi, R., & Tardiola, A. (Eds.). (2011). La sanità in Italia. Organizzazione, governo, regolazione, mercato. Bologna, Italia: Il Mulino.

- Del Guercio, A., & Bifulco, L. (2016). Lo sport come veicolo di inclusione sociale dei migranti. Diritti dell’Uomo, (3), 569-596.

- Durlauf, S. N. , & Fafchamps, M. (2005). Social capital. In P. Aghion & S. Durlauf (Eds.), Handbook of Economic Growth (Vol. 1, pp. 1639-1699). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Ettner, S. L. (1996). New evidence on the relationship between income and health. Journal of Health Economics, 15, 67-85. [CrossRef]

- Felice, E. (2007). Divari regionali e intervento pubblico. Per una rilettura dello sviluppo in Italia. Bologna, Italia: Il Mulino.

- Felice, E. (2016). Perché il Sud è Rimasto Indietro. Bologna, Italia: Il Mulino.

- Fiore, E. (2013). Fiere, sagre e feste paesane. Sant’Arcangelo di Romagna, Italia: Maggioli.

- Fiore, E., & Corradi, M. (2022). Fiere, sagre, feste paesane e spettacoli viaggianti. Sant’Arcangelo di Romagna, Italia: Maggioli.

- Frumkin, P. (2003a). Inside venture philanthropy. Society, 40(4), 7-15. [CrossRef]

- Frumkin, P. (2003b). On Being Non-profit: A Conceptual and Policy Primer. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Gabrielli, L., & Lee, S. (2009). The relative importance of sector and regional factors in Italy. Journal of Property Investment & Finance, 27(3), 277-289. [CrossRef]

- Genzone, A. (2021). Non profit in Italia. I numeri di un settore in crescita. Available online: https://www.lenius.it/non-profit-in-italia/.

- Greco, G. (2014). Il valore sociale dello sport: un nuovo limite alla c.d. specificità? Giornale di diritto amministrativo, 20(8/9), 815-824.

- Guiso, L., Sapienza, P., & Zingales, L. (2004). The Role of Social Capital in Financial Development. American Economic Review, 94(3), 526–556. [CrossRef]

- Hanewald, K. (2011). Explaining mortality dynamics: The role of macroeconomics fluctuations and cause of death trends. North American Actuarial Journal, 15, 290-314. [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, C. (2014). Analysis of Panel Data. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Isfol (2011). IV Rapporto biennale sul volontariato. Roma: Ministero del Lavoro e delle Politiche Sociali. Available online: https://www.lavoro.gov.it/sites/default/files/archivio-doc-pregressi/Documents/Resources/AnnoEuropeoVolontariato/Documenti/Rapporto_Biennale_Volontariato_vol_1.pdf.

- ISTAT (2023). Rapporto annuale 2023. Roma: ISTAT. Available online: https://www.istat.it/storage/rapporto-annuale/2023/Rapporto-Annuale-2023.pdf.

- Katz, B., & Ronfeldt, D. (2018). The rise of networked philanthropy: Digital platforms and social impact investing. Stanford Social Innovation Review, 16(3), 34-41.

- Katz, S., & Page, K. (2014). The Impact Investor: Lessons in Leadership and Strategy for Collaborative Capitalism. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Knack, S., & Keefer, P. (1997). Does social capital have an economic payoff? A cross-country investigation. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(4), 1251-1288. [CrossRef]

- Melis, V. (2021). Il lavoro degli stranieri vale 134 miliardi, il 9% del Pil italiano. Il Sole 24 Ore, 13 ottobre. Retrieved from https://www.ilsole24ore.com/art/il-lavoro-stranieri-vale-134-miliardi-9percento-pil-italiano-AE9Gi2n?refresh_ce=1 (Consultato il 15 giugno 2022).

- Nasaw, D. (2006). Andrew Carnegie. New York, NY: Penguin Press.

- Neumayer, E. (2005). Commentary: the economic business cycle and mortality. International Journal of Epidemiology, 1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, A., Emerson, J., & Paton, R. (2015). Social Finance. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Orlandis, J. (2005). Le istituzioni della Chiesa cattolica. Storia, diritto, attualità. Cinisello Balsamo, Italia: San Paolo.

- Owen, D. (1964). English Philanthropy 1660-1960. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Peri, G. (2004). Socio-Cultural Variables and Economic Success: Evidence from Italian Provinces 1951–1991. The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, 4(2), 1-31. [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R. D. (1993). Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

- Realfonzo, R., & Vita, C. (2007). Sviluppo dualistico e mezzogiorni d’Europa. Verso nuove interpretazioni dei divari regionali in Europa e in Italia. Milano, Italia: Franco Angeli.

- Rodgers, D. T. (1998). Atlantic Crossings: Social Politics in a Progressive Age. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Salamon, L. M., & Anheier, H. K. (1997). Defining the Non-profit Sector: A Cross-National Analysis. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

- Salamon, L. M., & Sokolowski, W. (2014). The Third Sector in Europe: Towards a Consensus Conceptualization. TSI Working Paper Series No. 2. Brussels, Belgium: Third Sector Impact.

- Sirven, N., & Debrand, T. (2011). Social Capital and health of older Europeans: Individual Pathways to Health Inequalities. Gerontologist, 51, 217-217. [CrossRef]

- Swift, R. (2011). The relationship between health and GDP in OECD countries in the very long run. Health Economics, 20(3), 306-322.

- Vallauri, C. (2022). Storia dei sindacati nella società italiana. Roma, Italia: Futura.

- Vogt, C.P. (2002). Patronage and Philanthropy in the Early Church: The Transformation of Piety. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Wooldridge, J. M. (2010). Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Zamagni, S. (2005). Economia Civile. Bologna, Italia: Il Mulino.

Figure 1.

Documents by year. Source: Scopus.

Figure 1.

Documents by year. Source: Scopus.

Figure 2.

Documents by subject area. Source: Scopus.

Figure 2.

Documents by subject area. Source: Scopus.

Figure 3.

Documents by year. Source: Scopus.

Figure 3.

Documents by year. Source: Scopus.

Figure 4.

Documents by country or territory. Source: Scopus.

Figure 4.

Documents by country or territory. Source: Scopus.

Figure 5.

Map of the most cited documents. Source: VOSviewer processing.

Figure 5.

Map of the most cited documents. Source: VOSviewer processing.

Figure 6.

Connections between keywords. Source: VOSviewer processing.

Figure 6.

Connections between keywords. Source: VOSviewer processing.

Figure 7.

Relationship between the number of volunteers (VOLpro) and the logarithm of GDP per capita Source. Our elaboration.

Figure 7.

Relationship between the number of volunteers (VOLpro) and the logarithm of GDP per capita Source. Our elaboration.

Figure 8.

Relationship between volunteering (in abscissa) and GDP by region (in ordinate). Source. Faceted chart, our elaboration.

Figure 8.

Relationship between volunteering (in abscissa) and GDP by region (in ordinate). Source. Faceted chart, our elaboration.

Figure 9.

Average GDP growth over time. Source: Our elaboration.

Figure 9.

Average GDP growth over time. Source: Our elaboration.

Figure 11.

Graph of sample quantiles compared with those of a Normal. Source: our elaboration.

Figure 11.

Graph of sample quantiles compared with those of a Normal. Source: our elaboration.

Figure 12.

Histogram of residues (Abscissa residues; Frequency in ordinate). Source: our elaboration.

Figure 12.

Histogram of residues (Abscissa residues; Frequency in ordinate). Source: our elaboration.

Figure 13.

Graph the residuals towards the rented values (Rented values in the x-axis; Residues in ordinate). Source: our elaboration.

Figure 13.

Graph the residuals towards the rented values (Rented values in the x-axis; Residues in ordinate). Source: our elaboration.

Table 1.

Most cited documents.

Table 1.

Most cited documents.

| n. |

Document |

Citations |

n. |

Document |

Citations |

| 1 |

Acs (2002) |

88 |

13 |

Tan (2013) |

5 |

| 2 |

Acs (2013) |

47 |

14 |

Edward (2019) |

5 |

| 3 |

Abbas (2023) |

46 |

15 |

Musari (2020) |

5 |

| 4 |

Wirba (2024) |

45 |

16 |

Ayub (2024) |

5 |

| 5 |

Ari (2021) |

28 |

17 |

Huda (2022) |

4 |

| 6 |

Reiner (1981) |

23 |

18 |

Katz (2006) |

4 |

| 7 |

Mcquilten (2020) |

17 |

19 |

Abdulai (2015) |

3 |

| 8 |

Saint-Paul (2003) |

15 |

20 |

Rambe (2018) |

2 |

| 9 |

Irving (2014) |

9 |

21 |

Moran (2016) |

2 |

| 10 |

Magomedova (2020) |

8 |

22 |

Reindl (2024) |

2 |

| 11 |

Sharpley (2019a) |

8 |

23 |

Sharpley (2019b) |

1 |

| 12 |

Ji (2022) |

7 |

24 |

--- |

|

|

Source: Our processing of VOSviewer data. |

Table 2.

Keywords: Frequency and TLS.

Table 2.

Keywords: Frequency and TLS.

| n. |

Keyword |

Occurrences |

TLS |

n. |

Keyword |

Occurrences |

TLS |

| 1 |

Philanthropy |

5 |

39 |

15 |

Global Poverty Estimates |

1 |

20 |

| 2 |

Sustainability |

2 |

26 |

16 |

Globalisation |

1 |

20 |

| 3 |

Waqf |

2 |

10 |

17 |

Inequality |

1 |

20 |

| 4 |

Corporate Philanthropy |

2 |

9 |

18 |

Poverty Lines |

1 |

20 |

| 5 |

Government |

2 |

9 |

19 |

The Cold War |

1 |

20 |

| 6 |

Poverty |

2 |

9 |

20 |

The Precariat |

1 |

20 |

| 7 |

China |

2 |

8 |

21 |

The Prosperiat |

1 |

20 |

| 8 |

Corporate Social Responsibility |

2 |

8 |

22 |

The Securiat |

1 |

20 |

| 9 |

Development Aid |

1 |

20 |

23 |

The Welfare State |

1 |

20 |

| 10 |

Economic Growth |

1 |

20 |

24 |

The World Bank |

1 |

20 |

| 11 |

Global Consumption |

1 |

20 |

25 |

Wealth Redistribution |

1 |

20 |

| 12 |

Global Consumption Density Curves |

1 |

20 |

26 |

Welfare Dynamics |

1 |

20 |

| 13 |

Global Growth Incidence Curves |

1 |

20 |

27 |

World Development Indicators |

1 |

20 |

| 14 |

Global Population Density Curves |

1 |

20 |

28 |

Cash Waqf |

1 |

6 |

|

Source: Our processing of VOSviewer data. |

Table 3.

The main sources.

Table 3.

The main sources.

| n. |

Source |

Documents |

Citations |

| 1 |

Small Business Economics |

1 |

88 |

| 2 |

Why Philanthropy Matters: how the Wealthy Give, and

what it Means for our Economic Well-Being |

1 |

47 |

| 3 |

Economic Growth and Environmental Quality in a Post-Pandemic World: New Directions in the Econometrics of the Environmental Kuznets Curve |

1 |

46 |

| 4 |

Journal of the Knowledge Economy |

1 |

45 |

| 5 |

Borsa Istanbul Review |

1 |

28 |

| 6 |

Economic Geography |

1 |

23 |

| 7 |

Social Enterprise Journal |

1 |

17 |

| 8 |

Journal of the European Economic Association |

1 |

15 |

| 9 |

The Upside of aging: How Long Life is Changing the World of Health, Work, Innovation, Policy, and Purpose |

1 |

9 |

| 10 |

A Research Agenda for Tourism and Development |

1 |

8 |

| 11 |

Ciriec-Espana Revista de Economia Publica, Social Y Cooperativa |

1 |

8 |

| 12 |

Economic Modelling |

1 |

7 |

| 13 |

Asian Journal of Business Ethics |

1 |

5 |

| 14 |

Economic Empowerment of Women in the Islamic

World: Theory and Practice |

1 |

5 |

| 15 |

Qualitative Research in Financial Markets |

1 |

5 |

| 16 |

The End of Poverty: Inequality and Growth in Global Perspective |

1 |

5 |

|

Source: Our processing of VOSviewer data. |

Table 4.

Non-profit institutions in the Italian regions (2015-2019).

Table 4.

Non-profit institutions in the Italian regions (2015-2019).

| Regions and autonomous provinces |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

| Piedmont |

28,527 |

29,017 |

29,649 |

30,090 |

30,011 |

| Aosta Valley |

1,339 |

1,370 |

1,382 |

1,410 |

1,410 |

| Lombardy |

10,455 |

10,668 |

10,905 |

11,165 |

11,152 |

| Liguria |

52,667 |

54,984 |

56,447 |

57,710 |

58,124 |

| Trentino-Alto Adige |

11,342 |

11,520 |

11,853 |

12,063 |

12,245 |

| Bolzano |

5,340 |

5,365 |

5,588 |

5,607 |

5,755 |

| Trento |

6,002 |

6,155 |

6,265 |

6,456 |

6,490 |

| Veneto |

29,871 |

30,235 |

30,597 |

31,035 |

31,087 |

| Friuli-Venezia Giulia |

10,235 |

10,495 |

10,722 |

11,004 |

10,973 |

| Emilia-Romagna |

26,983 |

27,162 |

27,342 |

27,819 |

27,900 |

| North |

171,419 |

175,451 |

178,897 |

182,296 |

182,902 |

| Tuscany |

26,588 |

26,869 |

27,534 |

27,802 |

28,182 |

| Umbria |

6,781 |

6,745 |

6,875 |

7,098 |

7,130 |

| Marche |

11,487 |

11,443 |

11,449 |

11,555 |

11,566 |

| Latium |

30,894 |

31,274 |

32,236 |

33,325 |

33,812 |

| Center |

75,751 |

76,331 |

78,094 |

79,780 |

80,690 |

| Abruzzo |

7,835 |

7,853 |

8,043 |

8,221 |

8,316 |

| Molise |

1,779 |

1,933 |

2,061 |

1,971 |

2,063 |

| Campania |

19,252 |

19,562 |

20,979 |

21,315 |

21,489 |

| Apulia |

16,823 |

17,355 |

17,147 |

18,485 |

18,968 |

| Basilicata |

3,334 |

3,627 |

3,669 |

3,807 |

3,767 |

| Calabria |

8,593 |

9,070 |

9,370 |

10,010 |

10,329 |

| Sicily |

20,699 |

21,291 |

21,886 |

22,420 |

22,664 |

| Sardinia |

10,790 |

10,959 |

10,346 |

11,269 |

11,446 |

| South |

89,105 |

91,650 |

93,501 |

97,498 |

99,042 |

| Italy |

336,275 |

343,432 |

350,492 |

359,574 |

362,634 |

|

Source: Istat |

Table 5.

Non-profit institutions and their number of employees (2015-2019).

Table 5.

Non-profit institutions and their number of employees (2015-2019).

| Years |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

| INP |

336275 |

343432 |

350492 |

359574 |

362634 |

| DEPENDENTS |

788126 |

812706 |

844775 |

853476 |

861919 |

|

Source: Istat |

Table 6.

The development of philanthropy in Italy - numbers, indices, fixed base 2015.

Table 6.

The development of philanthropy in Italy - numbers, indices, fixed base 2015.

| Macro areas |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

| North |

1.000 |

1.024 |

1.044 |

1.063 |

1.067 |

| Center |

1.000 |

1.008 |

1.031 |

1.053 |

1.065 |

| South |

1.000 |

1.029 |

1.049 |

1.094 |

1.112 |

|

Source: Our elaboration. |

Table 7.

Descriptive statistics related to non-profit institutions.

Table 7.

Descriptive statistics related to non-profit institutions.

| Regions and autonomous provinces |

Average |

Standard error |

Median |

Minimum |

Maximum |

| Piedmont |

29,459 |

300 |

29,649 |

28,527 |

30,090 |

| Aosta Valley |

1,382 |

13 |

1,382 |

1,339 |

1,410 |

| Lombardy |

10,869 |

138 |

10,905 |

10,455 |

11,165 |

| Liguria |

55,986 |

994 |

56,447 |

52,667 |

58,124 |

| Trentino-Alto Adige |

11,805 |

167 |

11,853 |

11,342 |

12,245 |

| Bolzano |

5,531 |

78 |

5,588 |

5,340 |

5,755 |

| Trento |

6,274 |

92 |

6,265 |

6,002 |

6,490 |

| Veneto |

30,565 |

233 |

30,597 |

29,871 |

31,087 |

| Friuli-Venezia Giulia |

10,686 |

146 |

10,722 |

10,235 |

11,004 |

| Emilia-Romagna |

27,441 |

180 |

27,342 |

26,983 |

27,900 |

| North |

178,193 |

2,155 |

178,897 |

171,419 |

182,902 |

| Tuscany |

27,395 |

294 |

27,534 |

26,588 |

28,182 |

| Umbria |

6,926 |

80 |

6,875 |

6,745 |

7,130 |

| Marche |

11,500 |

26 |

11,487 |

11,443 |

11,566 |

| Latium |

32,308 |

564 |

32,236 |

30,894 |

33,812 |

| Center |

78,129 |

953 |

78,094 |

75,751 |

80,690 |

| Abruzzo |

8,054 |

96 |

8,043 |

7,835 |

8,316 |

| Molise |

1,961 |

52 |

1,971 |

1,779 |

2,063 |

| Campania |

20,519 |

464 |

20,979 |

19,252 |

21,489 |

| Apulia |

17,756 |

412 |

17,355 |

16,823 |

18,968 |

| Basilicata |

3,641 |

83 |

3,669 |

3,334 |

3,807 |

| Calabria |

9,474 |

314 |

9,370 |

8,593 |

10,329 |

| Sicily |

21,792 |

361 |

21,886 |

20,699 |

22,664 |

| Sardinia |

10,962 |

192 |

10,959 |

10,346 |

11,446 |

| South |

94,159 |

1,834 |

93,501 |

89,105 |

99,042 |

| Italy |

350,481 |

4,909 |

350,492 |

336,275 |

362,634 |

|

Source: elaborations on Istat data. |

Table 8.

Geographical distribution of philanthropic activities (% values).

Table 8.

Geographical distribution of philanthropic activities (% values).

| Macro Region |

Culture, sport and recreation |

Education and research |

Health |

Social assistance and civil protection |

Environment |

Economic development and social cohesion |

Protection of rights and political activity |

Philanthropy and volunteering |

Cooperation and solidarity internazionale |

Religion |

Trade union relations and the like |

Other activities |

Total |

| North |

65,786 |

4,155 |

3,536 |

8,526 |

1,608 |

1,436 |

1,660 |

1,146 |

1,555 |

4,947 |

5,176 |

0,469 |

100 |

| Center |

61,468 |

3,772 |

3,757 |

9,800 |

1,725 |

2,010 |

2,061 |

0,988 |

1,293 |

5,249 |

7,188 |

0,688 |

100 |

| South |

61,889 |

3,810 |

3,489 |

10,889 |

1,408 |

2,767 |

1,190 |

1,054 |

0,596 |

3,919 |

8,512 |

0,477 |

100 |

|

Geographical distribution of employees (values%)

|

| North |

5,907 |

16,644 |

22,746 |

36,492 |

0,172 |

11,915 |

0,219 |

0,278 |

0,446 |

0,896 |

3,761 |

0,526 |

100 |

|

| Center |

7,604 |

13,226 |

22,106 |

34,333 |

0,435 |

12,057 |

0,998 |

0,358 |

0,936 |

1,324 |

5,959 |

0,664 |

100 |

|

| South |

2,268 |

13,404 |

21,176 |

42,504 |

0,278 |

11,879 |

0,299 |

0,117 |

0,146 |

1,400 |

5,821 |

0,707 |

100 |

|

|

Source: Istat |

|

Table 9.

Estimation of the random effects model.

Table 9.

Estimation of the random effects model.

| Coefficients |

Esteem |

Std.error |

zvalue |

pvalue |

| Intercepts |

194373 |

7579201 |

2.5646 |

0.01033 |

| Volpro |

135301 |

2626036 |

5.1523 |

0.00000 |

| Relpro |

-422439 |

2309150 |

-1.8294 |

0.06734 |

|

Source: Processing carried out with RStudio software (plm library) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).