1. Introduction

Metallic materials suffer from a ductile-to-brittle transition (DBT) phenomenon as temperature decreases over a critical point or range, which is called the DBT temperature (DBTT). Above DBTT, metals or alloys fracture in a ductile mode companied with large energy absorption through plastic deformation. Below DBTT, crack propagates rapidly without evident deformation at crack tip, thereby inducing a brittle fracture behavior. Different from face-centered cubic (FCC) and hexagonal close-packed (HCP) metals, body-centered cubic (BCC) metals exhibit the most pronounced DBT behavior, with a distinct temperature interval over which the transition occurs [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. BCC are the most common crystal structure of refractory metals and alloys, as well as iron and steels, due to its much higher ability to achieve high strength and creep resistance through processing or heat treatment. Understanding the mechanisms underlying the DBT of BCC metals and alloys is of significance for improving their low-temperature toughness and reducing their DBTT.

Compared to FCC metals, BCC metals possess a higher number of slip systems, but only a limited number of these systems (e.g., {110} <111>) can be activated at low temperatures due to their high critical shear stresses. This results in pronounced deformation anisotropy [

7]. From the perspective of energy, the atomic arrangement in BCC metals is less compact than in FCC metals, leading to higher lattice resistance. Dislocations in BCC metals must overcome significant Peierls potential during motion. Thermal activation above the DBTT facilitates dislocation movement overcoming Peierls potential, enabling ductile fracture via plastic deformation. Below DBTT, thermal activation is insufficient, causing the Peierls potential to become insurmountable, which restricts dislocation motion and leads to brittle fracture. From the perspective of dislocation motion and multiplication, the mobility of screw dislocations in BCC metals is more temperature-sensitive than that of edge dislocations. Below DBTT, the screw-character ends of the Frank-Read (F-R) source have restricted mobility and cannot effectively curl back, resulting in inefficient dislocation multiplication. As a result, plastic deformation is stuck at crack tip, leading to a brittle fracture. Recent studies by Han, et al have advanced the understanding of DBT in BCC metals. In their investigation of Cr metal, they identified the ratio of screw dislocation to edge dislocation motion rates α as a key parameter controlling DBT [

8]. Based on F-R dislocation sources, they elucidated how α influences dislocation multiplication and proposed a DBTT prediction model for BCC metals [

9]. Experimental validation confirmed the role of α in regulating the proliferation efficiency of F-R dislocation sources [

10]. These findings established a direct link between DBTT and the mobility of screw dislocations in BCC metals. Further, the motion of screw dislocations is fundamentally governed by the thermally activated nucleation and migration of double kinks, which are significantly temperature-dependent [

11]. Ghafarollahi and Curtin discussed the nucleation and migration of double kinks in BCC alloys, as detailed in the literature [

12] and [

13], and proposed an analytical statistical model for the double-kink nucleation and migration with energy barriers under the effect of solute atoms. However, due to the discrete three-dimensional core structure of screw dislocations and the lack of proper characterization techniques, the study remains primarily on model constructions and theoretical calculations. The lack of direct evidence makes it impossible to experimentally verify the temperature dependence of double kinks and their effect on screw dislocation mobility.

Besides temperature-dependent thermal activation, solute atoms would also exert great influences on the nucleation and migration of double kinks in BCC metals. As early as 1978, Pink and Arsenault [

14] discussed the “alloy softening” effect in BCC alloys,where the solid solution of alloying elements results in a lower yield stress than that of the base metal at low temperatures. This phenomenon, known as “Dilute solid solution softening”, is observed in dilute solid solution systems (alloy content < 1 at. %), this anomalous effect manifests as simultaneous strength reduction and ductility enhancement at low temperatures, countering the known “solid solution strengthening”. Recent molecular dynamics simulations by Lin, et al. [

15] revealed that Re additions in BCC-W alloys effectively decrease the DBTT while flattening the DBT slope, thereby enhancing cryogenic fracture toughness. Based on density functional calculations, Ghafarollahi and Curtin [

12,

13] reported that the yield stresses of dilute Fe-Si, W-Ta and W-Re alloys at 0 K were remarkably lower than those of pure Fe and pure W, and suggested that solute atoms improve the low-temperature mobility of screw dislocations by lowering the nucleation energy of double kinks. Wakeda, et al. [

16] demonstrated that Si reduces the nucleation energy of double kinks from 150.6 meV in pure Fe to 50 meV in Fe-Si alloys, accompanied with a decrease of DBTT by approximately 50 K. Trinkle [

17] further concluded in dilute BCC Mo alloys: At low temperatures, double kinks on screw dislocations can migrate rapidly along the dislocation line as they are edge character which is less temperature-sensitive. Therefore, the kink migration has a negligible barrier and the double-kink nucleation is the rate-limiting step of screw dislocation mobility at low temperatures. Dilute solute atoms promote double-kink nucleation through their stress fields, thereby enhancing the mobility of screw dislocations at low temperature.

Since BCC is the main crystal structure of most low-alloy steels and refractory alloys, elucidating the DBT mechanism in BCC metals and understanding/utilizing the dilute solution softening effect are of significant scientific and practical value for improving the low-temperature toughness of such materials. Therefore, this review aims to enhance the understanding of the DBT mechanism and dilute solid solution softening effect in BCC metals, providing new insights for further reducing the ductile-to-brittle transition temperature (DBTT) of BCC metals or alloys, thereby advancing the development of cost-effective cryogenic-resistant alloy materials.

2. DBT of BCC Metals

The low-temperature brittleness of BCC metals stems from the competitive mechanism between hindered screw dislocation motion and cleavage fracture. At low temperatures, screw dislocations exhibit significantly diminished mobility whereas edge dislocations maintain relatively high mobility. The velocity ratio between screw and edge dislocations (α = vs/ve) becomes as the critical parameter governing DBT. When the temperature decreases below the DBTT, α undergoes a precipitous decline, rendering F-R dislocation sources incapable of sustained multiplication. Consequently, crack tips cannot release stress through dislocation emission, ultimately resulting in brittle fracture. Fundamentally, this phenomenon arises from the dynamic competition between screw and edge dislocations, manifesting the synergistic relationship between dislocation motion and microstructural evolution.

2.1. DBT Behavior of BCC Metals

Zhang, et al. [

18] conducted systematic numerical simulations to study the low-temperature brittle fracture behavior of BCC metals, as illustrated in

Figure 1 (a-b). Their findings revealed that the uncertainty distribution characteristics of four distinct crack propagation pathways are closely associated with the low-temperature brittleness of BCC metals, indirectly reflecting the material's brittle fracture behavior at low temperatures. As shown in

Figure 1 (c) [

19], the transition from ductile to brittle fracture in BCC metals occurs as temperature decreases. Its fracture behavior has remarkable features: lack of thermal activation at low temperatures leads to the dislocation motion being hindered, and the plastic deformation ability of the material is reduced, while the stress concentration is intensified, and the rapid expansion of microcracks ultimately leads to brittle fracture. Above DBTT, ductile fracture dominated by slow crack propagation with characteristic dimpled morphology; below DBTT, brittle fracture featuring rapid crack extension manifested by cleavage steps and river patterns; in the DBT zone, hybrid fracture morphology emerges, combining localized dimples with cleavage features, indicative of competing plastic deformation and brittle fracture mechanisms. Du, et al. [

20] investigated the microstructural evolution and fracture behavior of three typical BCC metals (Tantalum (Ta), Iron (Fe), and Tungsten (W)) at low temperature using a multi-scale quasi-continuum method. Their results showed that Ta exhibits ductile fracture behavior due to dislocation emission at the crack tip and energy dissipation through twinning bands, which suppresses crack propagation. Iron (Fe) undergoes plastic deformation via dislocations and twins in the early stages but transitions to brittle fracture in the later stages, showing high sensitivity to DBT. Tungsten (W) experiences delayed crack propagation due to dislocation activity and twin formation but is unable to effectively suppress brittle fracture, resulting in predominantly brittle fracture behavior.

Critical factors governing low-temperature ductile/brittle fracture behavior and structure evolution in BCC metals: (1) Crystal Structure and Slip Systems:

Figure 2 (a) [

22] illustrates the DBTT curves for FCC, HCP, and BCC metals. BCC metals exhibit significant low-temperature brittleness. FCC metals with 12 independent slip systems ({111}<110>), undergo uniform plastic deformation due to the multi-slip systems, and typically do not exhibit DBT; HCP metals with only three slip systems ({0001}<11-20>), have minimal plastic deformation ability and are nearly brittle at room temperature, without significant DBT variation upon cooling [

23]; BCC metals have a slip direction of <111>, and slip planes such as {110}, {112}, {123}, etc., totaling 48 independent slip systems. However, compared with FCC metals, at low temperatures, the effective slip systems are limited. The atomic arrangement is not compact enough as shown in

Figure 2 (b) and the Peierls potential are high, which leads to dislocation cross-slip difficulties and exacerbates stress concentration and brittle fracture. The difficulty of screw dislocation slip requires overcoming the Peierls potential, further limiting its movability. (2) Dislocation behavior with Peierls potential: At low temperatures, screw dislocations rely on thermal activation for double kinks formation. Insufficient thermal activation leads to low nucleation rates, causing dislocation plugging that initiate microcracks. Solute atoms such as real earth (Re) and Nickel (Ni) enhance screw dislocation mobility by lowering Peierls potential. A representative example is provided by Raffo, et al. [

24], whose experimental studies on W-Re alloys demonstrated that adding 1% Re significantly reduces the DBTT. (3) Grain boundary and impurity elements: The segregation of impurities such as Phosphorus (P) and Sulfur (S) at grain boundaries, reducing boundary binding energy and causing intergranular brittle fracture. Adding rare earth elements like Cerium (Ce) or Lanthanoids (La) mitigates detrimental inclusions (e.g., MnS), purifies grain boundaries, and refines grains structures, thereby significantly enhancing low-temperature impact toughness. A representative case is demonstrated by Dong, et al. [

25], where rare earth-modified HRB400E rebar exhibited a 117% increase in impact energy at -20°C. (4) Temperature and strain rate: Insufficient thermal activation energy at low-temperature/high-strain-rate conditions, dislocations have difficulty in overcoming the Peierls potential, which can lead to stress concentrations to initiate brittle fracture. A representative example is Riedle, et al. [

26] study found that pure Tungsten (W) undergoes cleavage fracture at liquid nitrogen temperatures (77 K). Conversely, under high-temperature/low-strain-rate conditions, adequate thermal activation enhances dislocation mobility, enabling the material to exhibit ductile behavior.

2.2. Dislocations in DBT of BCC Metals

Extensive computational studies [

27,

28,

29] have established that screw dislocations in BCC metals exhibit a discrete three-dimensional core structure, which results in significant lattice friction during their movement. The slip of these dislocations is a thermally activated process that becomes increasingly hindered as temperature decreases. A representative example is Chromium (Cr) [

8], the substantial increase in Peierls potential at low temperatures makes dislocation slip particularly difficult. The pronounced low-temperature DBT behavior observed in BCC metals is attributed to their unique crystal structures and dislocation behaviors. The deformation characteristics are closely related to the DBT mechanism, which mainly involves the coordinated effects of dislocation nucleation, dislocation motion, and the relative motion rates of screw dislocations and edge dislocations.

(1) Dislocation nucleation domination: Research by Rice, et al. [

4,

30,

31] showed that the stress concentration at crack tips during material deformation is blunted by dislocation nucleation and motion, a process regulated by temperature and strain rate. At elevated temperatures, thermal activation facilitates rapid dislocation nucleation, forming a passivation zone that inhibits crack propagation, leading to ductile behavior. Conversely, at low temperatures, dislocation nucleation is hindered, causing stress concentrations to persist and trigger brittle fracture. Thus, dislocation nucleation governs crack propagation and dominates the DBT behavior in BCC metals. (2) Dislocation motion dominance: Gumbsch, et al. found that stress concentration at the crack tip is dynamically regulated by dislocation mobility through three-point bending experiments [

2] and Brunner, et al. [

32,

33,

34,

35] studied metal Tungsten (W). Under high-temperature or low-strain-rate conditions, dislocations are highly mobile, rapidly migrating to the crack tip to form dislocation sources and passivate the crack, resulting in ductile behavior and a lower the DBTT. Conversely, at low temperatures or high strain rates, dislocation motion is restricted, preventing stress release and leading to brittle fracture with an elevated DBTT. This behavior reflects a dynamic equilibrium between dislocation migration rates and stress concentration accumulation rates, which determines the DBT in BCC metals through the coupling of temperature and strain rate. (3) Relative motion rate control of Screw-edge dislocation: Han, et al. [

8,

9,

30] found that the DBT is controlled by the ratio of the relative motion rates of the screw dislocations to the edge dislocations (α =

vs /

ve) [

8,

36], which determines the plasticity capability of the material by regulating the multiplication efficiency of the F-R dislocation source, and the specific mechanism is shown in

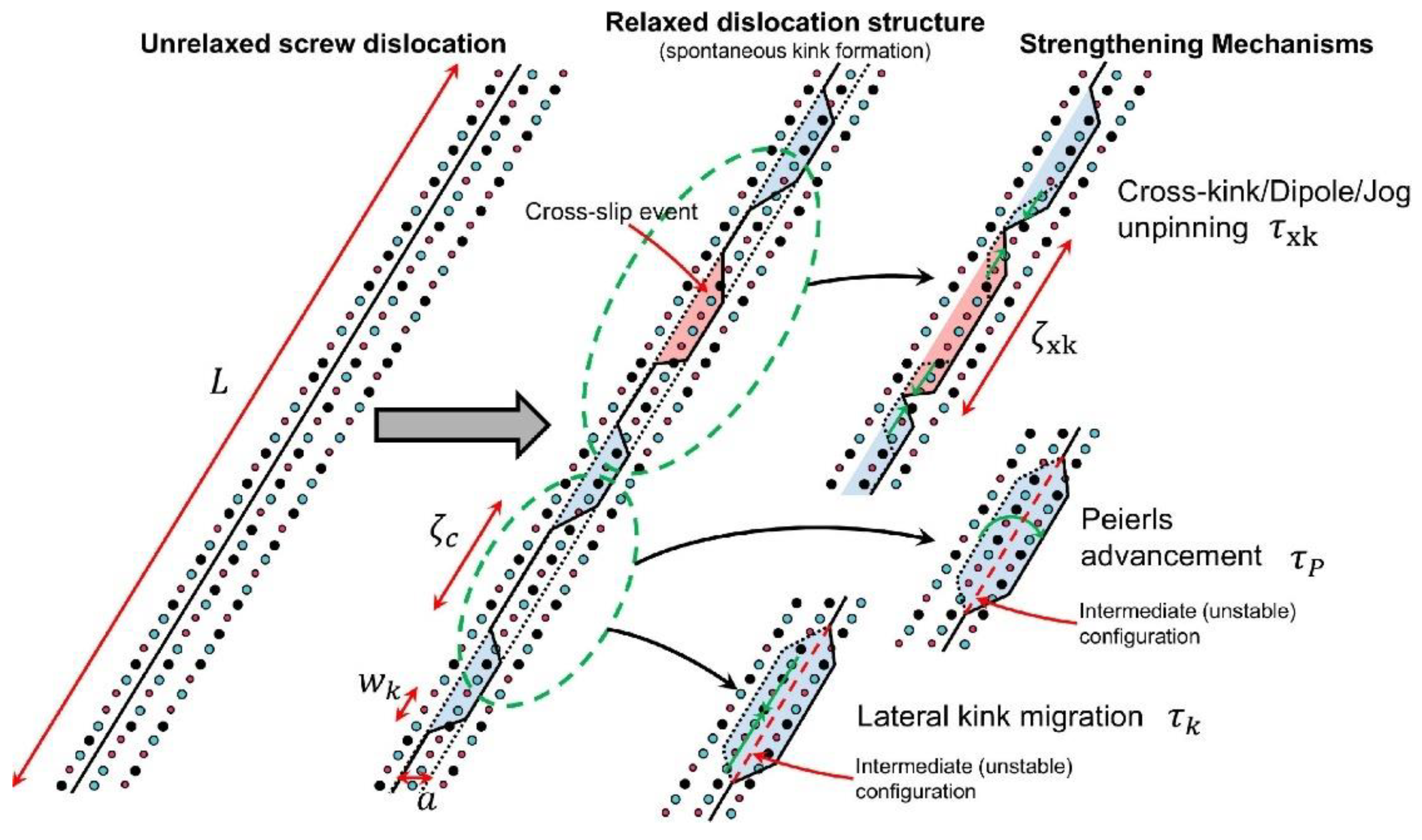

Figure 3 [

8,

10] When α ≥ 0.5, edge dislocations bow out beyond the semicircle, screw dislocations dominate the slip surface, efficiently proliferate the F-R dislocation source, the plastic mechanism dominates, and the material exhibits ductility; When α < 0.5, dislocations are difficult to coordinate, dislocation sources fail, and stress-concentrated brittle fracture dominates. In high-temperature nanoindentation experiments [

8], the team found that the screw dislocation mobility was significantly increased with temperature, and the α value increased with temperature, which promotes the activation of dislocation sources and reduces the DBTT. In Chromium (Cr), the critical α value for DBT was identified as 0.7, corresponding to a morphological transition in dislocation bow-out from semicircular configurations to fully activated F-R source geometries [

8]. Quantitative theoretical modeling [

10] further correlates dislocation source efficiency directly with the

vs /

ve mobility ratio, establishing α as a fundamental microstructural parameter for predicting ductile versus brittle failure modes.

Where α is the dislocation source efficiency; vs is the screw dislocation motion rate; ve is the edge dislocation motion rate; x, y denoted the slip distances of the edge dislocation and screw dislocation, respectively; r is the radius of the dislocation source; ellipse major axis is (x+r); ellipse minor axis is (y+r); and the ratio of the major and minor axes of the ellipse is k.

The DBT in BCC metals fundamentally arises from the dynamic competition between screw and edge dislocation velocities. This mechanism provides a well-defined microdynamic target for optimizing the low-temperature toughness of BCC metals through controlled dislocation kinematics.

3. Role of Screw Dislocation in DBT of BCC Metals

Screw dislocations play a pivotal role in governing the low-temperature DBT of BCC metals, exhibiting the strongest temperature dependence. This behavior primarily stems from three mechanistic origins: Firstly, the temperature dependence of double-kink thermal activation: screw dislocation motion critically relies on thermally activated double-kink nucleation and migration processes. Second, mobility disparity with edge dislocations: at low temperatures, screw dislocations demonstrate significantly lower mobility compared to edge dislocations. This mobility deficit leads to dislocation source inactivation and brittle fracture initiation. Third, solute atom effects: specific solute atoms enhance low-temperature screw dislocation mobility by perturbing local stress fields, thereby lowering the activation energy barrier for double-kink nucleation. Crucially, double-kink dynamics serve as the pivotal mechanism constraining screw dislocation mobility at low temperatures, dominates the DBT behavior in BCC metals.

3.1. Double-Kink Structure in Srew Dislocation

In the plastic deformation of BCC-W, the distinct core structures and energy states of 1/2〈111〉screw dislocations are intrinsically linked to their double-kink nucleation mechanisms [

37,

38,

39]. As illustrated in

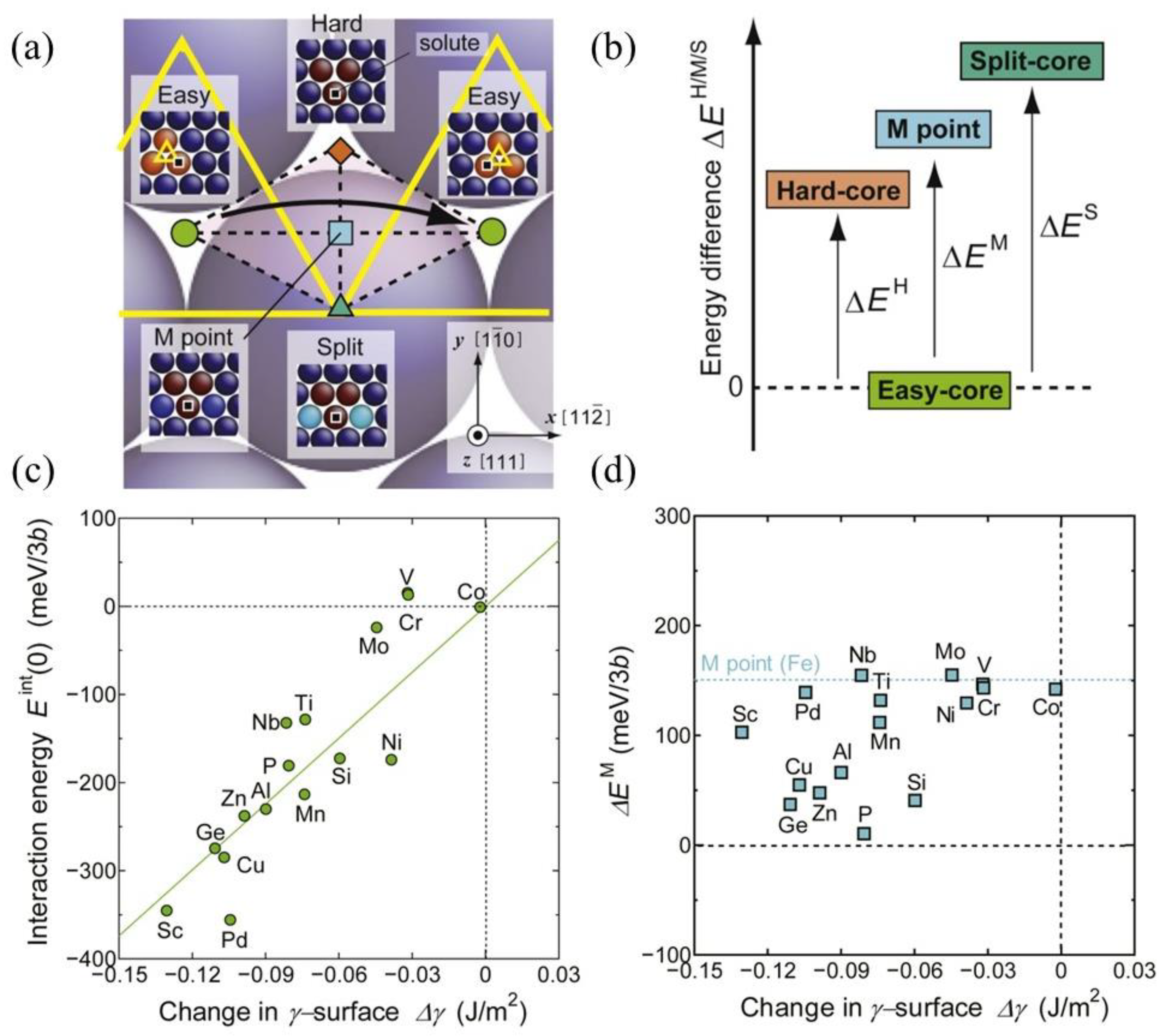

Figure 4 [

27,

28], screw dislocations exhibit four distinct core structures: Easy core, Hard core, Split core, and Saddle point, with significant energy disparities among them. The Easy core, minimum energy due to high atomic bond symmetry, while the Split core, maximum energy from severe lattice distortion. This energy gradient dictates the dynamic behavior of screw dislocations, enabling slip via the double kinks mechanism. Screw dislocations reduce slip resistance by forming a double kinks structure, which surmount the Peierls potential; the extension of these double kinks toward both ends of the dislocation is also influenced by the Peierls valley. As depicted in

Figure 5 (a) [

16], the effect (i) and effect (ii) on the Peierls valley and Peierls potential of screw dislocations following the substitution of solute atoms for Fe atoms at the dislocation core. According to the Cottrell's dislocation theory [

40], the restricted screw dislocation motion at low temperatures arises from high Peierls potential that hinder thermally activated double kinks formation, leading to dislocation pile-ups and subsequent brittle fracture. During dislocation motion, screw dislocations predominantly reside in low-energy Peierls valleys [

41], and screw dislocations must overcome periodic Peierls potential. When positioned in the Peierls valley, dislocations encounter minimal resistance to expansion, allowing localized kinks folds to form under thermal activation. These kinks subsequently propagate along the dislocation line under shear stress, eventually forming the double kinks structure depicted in

Figure 5 (b). The edged components at the kink steps reduce the activation energy of the extension, causing double kinks to extend to both ends, thus driving the whole screw dislocation forward, but this structure makes the screw dislocation slip path complex leading to increased lattice friction and difficult slip. If the double-kink nucleation is insufficient, the dislocation motion is blocked and drive the material toward brittle fracture. Consequently, the nucleation and migration of double kinks structures are dominated by thermally activated processes and exhibit the strongest temperature dependence [

17,

42,

43,

44]. The combination of limited lateral slip of the screw dislocations and rapid movement of the edge dislocations in BCC metals leads to the destruction of the mixed dislocation structure and the formation of long straight screw dislocations [

45]. At low temperature, the disparity between fast-moving edge dislocations and slow-moving screw dislocations prevents the evolution of an effective dislocation source, insufficiently producing mobile dislocations and inducing brittleness. As temperature increases, thermal activation facilitates double kinks formation [

10]. For instance, the effective formation of screw dislocation double kinks in metal W is approximately 1.05 eV [

36], which lies near the DBT threshold. Minor temperature reductions significantly suppress double-kink nucleation.

Trinkle, et al. [

12,

13,

17] demonstrated through first-principles calculations and experimental studies that certain solute atoms, such as Re and Pt, can effectively enhance the formation of double kinks in screw dislocations of BCC metals. These solutes significantly reduce dislocation motion resistance by lowering the formal energy barriers associated with double kinks formation, thereby promoting their nucleation and growth.

Screw dislocations overcome slip resistance by forming double kinks structures, which must overcome the Peierls potential. The expansion of these double kinks toward the dislocation ends is also influenced by the Peierls valleys. The Peierls-Nabarro stress dominates the dislocation motion, with solute atoms contribute to the nucleation of the double kinks by reshaping the electronic structure of the core of the dislocation and the strain field. Wakeda, et al. [

16] further revealed through first-principles calculations that solute atoms can promote double kinks formation by reducing the energy difference (

∆E) and Peierls potential associated with screw dislocations transitioning from the Easy core to the Hard core. For example, Silicon (Si) significantly lowers the Peierls potential by reconstructing the electron cloud or inducing lattice distortion, reducing

∆E from 150.6 meV in pure Iron (Fe) to approximately 50 meV. P reduces

∆E and the Peierls potential through charge transfer and bond electron cloud rearrangement, enabling screw dislocations to form double kinks even at low temperatures. Aluminum (Al) through its light atomic size effect and electronic interactions, modifies the local stress field within the dislocation core,lowering the formal energy barrier. In pure Iron (Fe), Aluminum (Al) reduces

∆E from 150.6 meV to approximately 80 meV, thereby facilitating double kinks formation. These mechanisms highlight how solute atoms promote BCC metals double kinks formation by altering core energetics and electronic configurations.

3.2. Low-Temperature Mobility of Screw Dislocations

The low-temperature mobility of screw dislocations constitutes the critical limiting factor for the low-temperature DBT in BCC metals. The F-R dislocation sources play a pivotal role in screw dislocation multiplication: Insufficient screw dislocation mobility at low temperatures reduces the number of mobile dislocations, leading to stress concentration and brittle fracture initiation. While edge dislocations can slide relatively easily, they alone cannot fulfill the extensive plastic deformation demands, particularly at low temperatures when screw dislocations are significantly less mobile than edge dislocations. This disparity hinders effective self-proliferating of dislocations, resulting in stress concentration and brittle fracture, and causes a sudden DBT in BCC metals. The motion of screw dislocations requires overcoming the Peierls potential through the formation of double kinks via thermal activation. As demonstrated in

Figure 6 [

36] illustrates the structural evolution of rolled Tungsten (W) at different temperatures, visually demonstrating the recovery of screw dislocation motion with increasing temperature. Below DBTT, the relative motion rate ratio between screw and edge dislocations (α =

vs/

ve) decreases significantly. The nucleation and migration of double kinks in screw dislocations become increasingly difficult, leading to reduced motion and dislocation source failure. Consequently, the material cannot relieve stresses through plastic deformation, resulting in brittle fracture dominance. Near DBTT, rising temperatures promote the thermal activation of screw dislocations, which enabling some to migrate and bend. This enhances dislocation source efficiency and crack tip blunting capability initiate the DBT. Above DBTT, thermal activation facilitates rapid nucleation and migration of double kinks, allowing screw dislocations to move as bent mixed dislocations. This effectively suppresses crack nucleation and propagation, enabling significant plasticity and completing the DBT [

13]. As the temperature increases further, the mobility of screw dislocations accelerates, with double kinks nucleating and migrating rapidly. Screw dislocations move as bent mixed dislocations, releasing stress and inhibiting crack propagation, thereby imparting toughness to the material. At low temperatures, the mobility of screw dislocations is limited by the nucleation rate of double kinks. Although the edged component of double kinks reduces the extension activation energy, the overall energy barrier for nucleation results in screw dislocations mobility several orders of magnitude lower than that of edge dislocations. Additionally, the elevated critical initiation stress of screw dislocations at low temperatures further restricts their mobility. Solute atoms can effectively modulate this process by perturbing the local stress field, thereby reducing the activation energy for double-kink nucleation in screw dislocations and promoting their initiation at low temperatures. Woodward, et al. [

17] demonstrated that Re solute atoms in Mo-Re alloys attract screw dislocations cores, lowering the energy barrier for double-kink nucleation. Below 350 K, the presence of Re solute significantly enhances the nucleation rate of double kinks and improves the mobility of screw dislocations.

The low-temperature ductility and DBT of BCC metals are predominantly governed by the mobility of screw dislocations at low temperatures. This dominance arises because, unlike edge dislocations, the mobility of screw dislocations is essential for activating and proliferating F-R dislocation sources, which facilitates extensive plastic deformation in BCC metals under low temperatures conditions. The low-temperature mobility of screw dislocations is closely tied to the number of double kinks on the dislocation. The edged component at the kink step allows the kink pair to expand to both ends of the screw dislocation with a smaller activation energy, thus driving the entire screw dislocation forward.

4. Dilute Solid Solution Softening Effect

The dilute solid solution softening effect refers to a unique phenomenon where low -concentration solutes (alloy content < 1 at. %) induce metal softening at low temperatures. This effect arises from solute-induced lattice distortions that reduce the Peierls potential, thereby weakening dislocation pinning and promoting the motion of screw dislocations. [

46,

47,

48]. The mechanisms include: (1) solute-induced local atomic rearrangement that lowers double-kink nucleation (Peierls mechanism); (2) kink slip bypass pinning points; (3) cross-kink promoting unpinning. Additionally, the attraction interaction between solutes and dislocations enhances dislocation mobility by reducing double-kink nucleation energy barriers (e.g., Re in W-Re and Mo-Re alloys), decreases critical resolved shear stress (CRSS), improves plastic deformation capability, and delays brittle fracture. This effect is particularly pronounced in BCC metals, manifesting as a significant decrease in low-temperature flow stress.

4.1. Dilute Solid Solution System and Softening Effect

A dilute solid solution system refers to solid solutions with solute atomic concentrations (alloy content < 1 at. %), within the matrix lattice without forming ordered phases or precipitates. While solute atoms typically act as solid solution strengtheners by hindering dislocation motion, the dilute solid solution softening effect describes a unique phenomenon where specific solute additions lead to material softening at low temperatures. This effect occurs because solute atoms reduce the Peierls potential associated with screw dislocation double-kink nucleation, thereby weakening the pinning effect on dislocations. By lowering the energy barriers for kink formation and propagation, solute atoms enhance dislocation mobility, reduce CRSS and improve plastic deformability. Additionally, this softening mechanism promote the plastic deformation capability of the material and delay the occurrence of brittle fracture.

The dilute solid solution softening effect is a unique phenomenon caused by low-concentration solutes (alloy content < 1 at. %) enhancing dislocation mobility through mechanisms involving reduced Peierls potential and enabling mechanisms such as kink-slip and unpinning. In dilute solid solution systems, the motion of screw dislocations is governed by three primary mechanisms, as illustrated in

Figure 7 [

49].

(1) Peierls mechanism [

50,

51,

52,

53]: In dilute solid solutions, solute atoms induce local lattice distortions that facilitate dislocation motion by reducing the energy required for double-kink nucleation. This directly weakening of the Peierls potential, thereby promoting material softening.

(2) Kink slip mechanism [

49]: In dilute solid solution systems, where solute atom concentrations are low, dislocations are more likely to bypass pinning points via kink slip. This reduces the pinning effect and lowers resistance to dislocation motion, enabling kinks to extend more readily and causing material softening.

(3) Cross-kink and unpinning mechanisms [

49,

54]: The formation of cross-kink relies on solute-induced multi-slip surface kinks. In dilute solid solution systems, solute atoms promote kink formation and pinning, but the resistance to kink extension remains low. This allows dislocations to unpin and continue gliding, resulting in the softening behavior of the material.

4.2. Dilute Solid Solution Softening Mechanim

The dilute solid solution softening mechanism appears to be the effect of solute atoms on dislocation motion, and the essence is the effect of screw dislocation double kinks structure. Solute atoms reduce the nucleation energy barrier of double kinks by interacting with the dislocation core, thereby promoting dislocation mobility and material softening. Weertman, et al. [

43] study demonstrated that solute atoms facilitate localized atomic rearrangements along dislocation lines, enabling double kinks formation at lower stress levels. The motion of screw dislocations at low temperatures depends on the nucleation and migration of double kinks. Solute atoms lower the nucleation barrier by modifying the local energy landscape of the dislocation core. In pure BCC metals (e.g., Iron (Fe)), periodic energy barriers of uniform height arise from the Peierls potential [

55,

56,

57]. In contrast, solute atoms in dilute solid solutions reduce the energy barrier for double-kink formation, particularly in regions along the dislocation line where localized solute fluctuations enhance kink nucleation. However, solute atoms increase the migration barrier for kinks, as kinks must overcome the maximum energy barrier along the dislocation line [

13].

Figure 8 [

16] illustrates that solute atoms are positioned centrally and migrate along the screw dislocation line by overcoming energy barriers. In dilute solid solution systems at low temperatures, solute additions alter the double kinks structure of screw dislocations [

58,

59], thereby softening the metallic matrix [

17]. Additionally, attractive forces exist between solute atoms and dislocation lines. At low concentrations, these attractive solutes exert a pulling effect on the dislocation core, reducing the Peierls potential for dislocation motion. This interaction promotes dislocation mobility and ultimately leads to material softening.

The dilute solid solution softening in BCC metals is effectively promoted by certain solute atoms that enhance screw dislocation double kinks formation in dilute solid solution systems. Curtin, et al. [

12] demonstrated that in W-Re alloys, low concentrations of Re interact attractively with screw dislocation cores, reducing the activation energy for double-kink nucleation. The local stress field perturbations caused by Re lower the resistance to kink extension, facilitating screw dislocation slip at low temperatures; Density functional theory (DFT) calculations indicate that Re solute interactions with screw dislocations significantly reduce nucleation energy barrier. Experimental data show a 30% reduction in yield stress for W-1% Re alloy at 300 K compared to pure Tungsten (W); Wiener Process Model (WPM) predicts that Re addition makes double-kink nucleation the dominant mechanism by reducing energy fluctuations during migration, ultimately achieving low-temperature softening. In Fe-Si alloys, low concentrations of Silicon (Si) atoms reduce the nucleation energy barrier for double kinks formation through local lattice distortions. Energy fluctuations induced by Silicon (Si) atoms promote double kinks formation, lowering the Peierls potential and enhancing low-temperature mobility of screw dislocations. Both the Discrete Rigid-Kink Model (DRKM) and the Stochastic Rigid Kink Model (SRKM) demonstrate that Si atoms reduce nucleation energy barriers, shifting plastic deformation from kink-controlled to migration-controlled, ultimately resulting in material softening. Trinkle [

17] noted that in Mo-Re alloys, the softening effect is most pronounced at low temperatures (77 K) with an 8% Re concentration, where yield stress is reduced by about 30% compared to pure Molybdenum (Mo). Double kinks deformation cores dominate this softening, directly confirming the solute-facilitated softening mechanism. In Mo-Pt alloys, strong attractive interactions between Platinum (Pt) concentration (alloy content ≪ 1 at. % ) solutes and dislocations significantly reduces the double-kink nucleation energy barrier, resulting in initial softening. Ghafarollahi, et al. [

12] studied Fe-Si alloys and found that Silicon (Si) atoms reduce the energy barrier to double-kink nucleation through localized energy fluctuations, thereby promoting low-temperature softening. Wakeda, et al. [

16] discovered that solute atoms modify the local bonding environment in screw dislocation cores through chemical misfit, thereby modulating the Peierls barrier and achieving solute softening. A strong correlation exists between chemical misfit (

∆γ) and interaction energy (

Eint(0)) in

Figure 8 (c, d) [

16], independent of

ΔEM, indicating that solute atoms significantly influence the local energy state of screw dislocations in the Easy-core by altering the local chemical bonding environment (e.g., the difference in the strength of Fe-solute and Fe-Fe bonds). Solute atoms (e.g., Si, Cu) exhibit negative

∆γ values by lowering local bonding energy, stabilizing the Easy-core and reducing the energy difference between the transition state Hard-core and M-points. This lowers the Peierls potential and promotes dislocation slip, manifesting as low-temperature softening; Sc forms strongly attractive dislocation-solute interactions through chemical misfit, creating energy valleys that reduce the activation energy for double-kink nucleation. This accelerates dislocation slip rates, enhances low-temperature dislocation mobility, decreases CRSS and ultimately manifests as solute softening.

The core mechanism of dilute solid solution softening in BCC metals lies in solute atoms effectively promoting the double-kink nucleation and propagation by modulating the bonding environment, energy fluctuations, and perturbing the stress field at screw dislocation cores. This mechanism provides crucial theoretical guidance for the designing high-performance BCC alloys.

5. Potential of Dilute Solid Solution Softening in Lowering DBTT

The DBTT is the critical temperature at which a metallic material transitions from a ductile to a brittle behavior, and lowering the DBTT enhances low-temperature ductility. The dilute solid solution softening mechanism significantly lowers the DBTT through solute atom microalloying and dislocation dynamics regulation, the effect originates two primary aspects: on the one hand, controlling impurities and inclusions is crucial. It is widely accepted that the low-temperature toughness of low-alloy steels after rare earth (Re) addition is attributed to inclusion modification and grain boundary purification. Modern research and metallurgical techniques have enabled the control of impurity elements and inclusions at very low levels. For example, Liu, et al. [

60] demonstrated that adding an appropriate amount of Cerium (Ce) to C-Mn steel purifies grain boundaries and suppresses the formation of large irregular Sulphur (S) or Titanium (Ti)-containing inclusions. This reduces the risk of cleavage fracture in C-Mn steels at low temperatures, increases resistance to crack propagation, significantly improves low-temperature toughness, while lowering DBTT. However, such approaches remain constrained by the inherent limitations of ferrite matrix in further reducing the DBTT. On the other hand, the dilute solid solution softening effect after rare earth solid solution plays a significant role. Solute atoms (e.g., Ni, Mn, Si) promote low-temperature dislocation slip by reconfiguring the electron clouds in the dislocation core or inducing lattice distortions, thereby reducing Peierls-Nabarro stress and double-kink nucleation energy barrier. For example, Tanaka, et al. [61] found that adding 2 mass% Nickel (Ni) to ultra-low carbon (C) steel decreased the DBTT from 200 K to 150 K. The yield stress was lower than that of the Nickel (Ni)-free matrix, exhibiting significant solid solution softening. Wakeda, et al. [

16] noted that Silicon (Si) in Fe-Si alloys reduces the double-kink nucleation energy barrier from 150.6 meV in pure Iron (Fe) to 50 meV, leading to a DBTT reduction of about 50 K; Scandium (Sc) forms strong interactions with dislocations through chemical misfit, creating energy valleys that significantly lower the activation energy for double kinks formation and promote low-temperature dislocation slip dynamics. This solute softening effect enhances low-temperature plastic deformability by reducing the CRSS, suppressing brittle fracture tendencies, and ultimately leading to a significant reduction in DBTT. Hu, et al. [

58] investigated the solute-induced softening effect of 21 alternative alloying elements (Al, Co, Cr, etc.) in BCC-W and found that Aluminium (Al) and Manganese (Mn) are the most promising alternative solute elements to Re for improving the low-temperature toughness of BCC-W, capable of significantly reducing the DBTT. Solute atoms (e.g., Mn, Si) enhance low-temperature toughness by reducing strain-rate sensitivity, thereby potentially lowering the DBTT. Uenishi, et al. [62] observed in interstitial-free (IF) steels that Mn/Si additions reduce low-temperature brittleness by adjusting the dislocation thermal activation mechanism. In the models of Sato and Meshii, et al. [

48], Mn solute atoms inhibit brittle fracture by introducing misfit strain centers, reducing the double kinks formation energy barrier, and making dislocations more prone to slip at low temperatures. These findings collectively highlight the importance of solute atom interactions in enhancing low-temperature toughness and reducing the DBTT in BCC metals.

In summary, the dilute solid solution softening mechanism, combined with the unique role of solute atoms, particularly rare earth elements, overcomes the limitations of traditional inclusion modification and offers a novel approach to reducing the DBTT. By leveraging the grain boundary purification capability of rare earth elements and the electron/strain effects of solutes such as Scandium (Sc) Nickel (Ni), a synergistic improvement in low-temperature toughness can be achieved. This approach not only enhances the mechanical performance of materials at low temperatures but also accelerates the development of high-strength, low-temperature-resistant materials for applications in extreme environments, such as polar engineering and aerospace.

6. Conclusions and Prospects

This reviews the low-temperature brittle fracture behavior and dilute solid solution softening effects of BCC metals. The DBT behavior of BCC metals is mainly governed by the low-temperature mobility of screw dislocations, whose core mechanism is the nucleation and migration of the double kinks. Dilute solid solution softening reduces the nucleation activation energy of the double kinks of screw dislocations through the action of solute atoms on the double kinks of screw dislocations and weakens the Peierls potential, thus enhancing the screw dislocation mobility and lowering the DBTT. The addition of specific alloying elements, such as Ce, Re, Ni, etc., to BCC metal can effectively exert the dilute solid solution softening effect, reduce the DBTT and improve the low-temperature toughness. Rare earth elements, due to their unique atomic and electronic structures, show significant potential for enhancing the properties of BCC metals. However, the mechanisms through which these elements improve low-temperature toughness remain unclear and warrant further investigation. The principal conclusions and prospects are summarized as follows:

Conclusions:

(1) BCC metals exhibit fewer effective slip systems and higher dislocation motion resistance compared to FCC metals at low temperatures, making them prone to stress concentration and eventual brittle fracture. This pronounced low-temperature brittleness is attributed to the high Peierls potential, which hinders screw dislocation motion. The resulting dislocation pile-up triggers significant DBT, leading to a distinct DBTT and brittle fracture.

(2) The DBT mechanism in BCC metals is primarily governed by the low-temperature mobility of screw dislocations, which overcome the Peierls potential through the nucleation and migration of double kinks. Their motion is thermally activated and regulated by temperature-dependent processes. When the ratio of the relative motion rates of the screw dislocations to the edge dislocations α ≥ 0.5, the screw dislocations dominate the slip surface and activate the F-R dislocation source to proliferate dislocations efficiently, which makes the material ductile; Conversely, when α < 0.5, the source of dislocations fails to proliferate, which leads to brittle fracture caused by stress concentration.

(3) The low-temperature mobility of screw dislocations in BCC metals is dominated by the nucleation rate of double kinks. Overcoming the Peierls potential involves thermally activated nucleation and migration processes. Nucleation requires dislocation segments to surmount the energy barrier of the Peierls potential, while migration is influenced by residual potential barriers. Solute atoms reduce this energy barrier, promoting double-kink nucleation and enhancing dislocation slip rates. Insufficient thermal activation at low temperatures reduces nucleation rates, causing dislocations to become trapped in the Peierls valleys, leading to pile-up and brittle fracture. Alloying counteracts this limitation by systematically reducing nucleation barriers, effectively restoring dislocation mobility at low temperatures and mitigating brittleness.

(4) The dilute solid solution softening effect describes how trace solute additions (alloy content < 1 at. %) to reduce the formal energy barrier of double kinks in screw dislocations. This is achieved through localized lattice distortions at low temperatures, which increase the nucleation rate of double kinks and enhance the low-temperature mobility of screw dislocations. By promoting the dynamic expansion of double kinks, solute atoms lower the Peierls potential for dislocation slip, thereby improving the low-temperature toughness of BCC metals and significantly reducing the DBTT.

Prospects:

(1) Currently, due to the limitations of low-temperature in-situ experimental techniques, research on the DBT mechanism of BCC metals remains focused on theoretical derivations and ex-situ experimental validations. Further microscopic and intuitive evidence is required to substantiate the screw dislocation-controlled DBT mechanism and the effects of dilute solid solution softening. Future studies should employ multiscale approaches combining computational simulations (e.g., first-principles calculations, density functional theory, and molecular dynamics simulations) with advanced experimental characterization techniques (e.g., in-situ TEM and atom probe tomography) to precisely elucidate the mechanisms by which solid-solution rare earths influence the low-temperature toughness and DBT of low-alloyed steels.

(2) The dilute solid solution softening effect of alloying elements serves as a crucial mechanism for enhancing the low-temperature toughness and reducing the DBTT in BCC alloys. By developing an integrated design strategy that links “alloy composition - low-temperature mobility of screw dislocations - low-temperature toughness,” further breakthroughs can be achieved in improving the low-temperature toughness of BCC alloys. This approach will accelerate the research and development of cost-effective cryogenic alloys, meeting the demand for such materials in applications like polar engineering, aerospace, and cryogenic storage.

Author Contributions

Jie Zhang: Writing –original draft, Investigation, Data curation. Tianliang Zhao: Writing –review & editing, Supervision, Methodology, Funding acquisition. Tingping Hou: Writing – review & editing. YanLi: Resources, Investigation. Zhongyu Cui: Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Kaiming Wu: Writing – review & editing, Resources.

Acknowledgments

This research was financially supported by the National Key Research and Development Program (No. 2023YFB3710300) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52471090).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors state that there are no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Christian, J. Some surprising features of the plastic deformation of body-centered cubic metals and alloys. Metall. Trans. A 1983, 14, 1237–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumbsch, P.; Riedle, J.; Hartmaier, A. Fischmeister H F. Controlling factors for the brittle-to-ductile transition in tungsten single crystals. Science 1998, 282, 1293–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, C. S. The brittle-to-ductile transition in pre-cleaved silicon single crystals. Philos. Mag., 1975, 32, 1193–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, J. R.; Thomson, R. Ductile versus brittle behaviour of crystals. Philos. Mag. 1974, 29, 73–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, S.G.; Booth, A.S.; Hirsch, P.B. Dislocation activity and brittle-ductile transitions in single crystals. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 1994, 176, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarleton, E.; Roberts, S. G. Dislocation dynamic modelling of the brittle–ductile transition in tungsten. Philos. Mag. 2009, 89, 2759–2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.; Takeuchi, S.; Yoshinaga, H. Dislocation dynamics and plasticity . Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media, 2013:. S: Berlin, 2013.

- Lu, Y.; Zhang, Y. H.; Ma, E.; Han, W. Z. Relative mobility of screw versus edge dislocations controls the ductile-to-brittle transition in metals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2021, 118, e2110596118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. H.; Ma, E.; Sun, J.; Han, W. Z. A unified model for ductile-to-brittle transition in body-centered cubic metals. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2023, 141, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. H.; Han, W. Z. Dislocation source efficiency and the ductile-to-brittle transition in metals. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2025, 229, 173–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caillard, D.; Martin, J. Thermally activated mechanisms in crystal plasticity. Amsterdam, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, 2003;

- Ghafarollahi, A.; Curtin, W. Theory of kink migration in dilute BCC alloys. Acta. Mater., 2021, 215, 117078.

- Ghafarollahi, A.; Curtin, W. A. Theory of double-kink nucleation in dilute BCC alloys. Acta. Mater., 2020, 196, 635–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pink, E.; Arsenault, R. J. Low-temperature softening in body-centered cubic alloys. Prog. Mater. Sci. 1980, 24, 1–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P. d.; Nie, J.f.; Cui, S. G.; Lu, Y. P. Molecular dynamics study on the ductile-to-brittle transition in W-Re alloy systems. Acta. Mater. 2025, 285, 120684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakeda, M.; Tsuru, T.; Kohyama, M.; Ozaki, T.; Sawada, H.; Itakura, M.; Ogata, S. Chemical misfit origin of solute strengthening in iron alloys. Acta. Mater. 2017, 131, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinkle, D. R.; Woodward, C. The chemistry of deformation: how solutes soften pure metals. Science 2005, 310, 1665–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Multi-scale simulation of crack propagation in the ductile-brittle transition region. (PDF) Multi-Scale Simulation of Crack Propagation in the Ductile-Brittle Transition Region (August 1, 2013).

- Du, H.; Ni, Y. S. Multi-scale simulation and toughness and brittleness analysis of three body-centered cubic metal cracks of tantalum, iron and tungsten. Acta. Phys. Sin-Ch. Ed. 2016, 65, 196202. [Google Scholar]

- Ha, K. F. Fundamentals of Fracture Physics. Beijing: Science Press, 2000: 55.

- Raffo, P. L. Yielding and fracture in tungsten and tungsten-rhenium alloys. J. Less. Common. Met. 1969, 17, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S. H.; Lu, H. C.; Liu, T. S.; Wang, C.C.; Xie, X.; Dong, H. Effect of rare earth on low-temperature impact toughness of HRB400E rebar. Chi. Metal. 2022, 32, 16–25. [Google Scholar]

- Riedle, J.; Gumbsch, P.; Fischmeister, H. F. Cleavage anisotropy in tungsten single crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett 1996, 76, 3594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S. Reliability design of mechanical systems. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd, 2020:286.

- Dezerald, L.; Rodney, D.; Clouet, E.; Ventelon, L.; Willaime, F. Plastic anisotropy and dislocation trajectory in BCC metals. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dezerald, L.; Ventelon, L.; Clouet, E.; Denoual, C.; Rodnry, D. Ab initio modeling of the two-dimensional energy landscape of screw dislocations in bcc transition metals. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 89, 024104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egorov, A.; Kraych, A.; Mrovec, M.; Drautz, R. Core structure of dislocations in ordered ferromagnetic FeCo. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2024, 8, 093604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W. Z.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, Y. H. Research Progress on Tough-Brittle Transition Mechanism of Body-Centered Cubic Metals. Acta. Metall. Sin. 2023, 59, 335–338. [Google Scholar]

- Kameda, J. A kinetic model for ductile-brittle fracture mode transition behavior. Acta. Metall. 1986, 34, 2391–2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, D.; Glebovsky, V. Analysis of flow-stress measurements of high-purity tungsten single crystals. Mater. Lett., 2000, 44, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannattasio, A. Roberts, S. G. Strain-rate dependence of the brittle-to-ductile transition temperature in tungsten. Philos. Mag. 2007, 87, 2589–2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannattasio, A.; Tanaka, M.; Joseph, T.; Roberts, S. An empirical correlation between temperature and activation energy for brittle-to-ductile transitions in single-phase materials. Phys. Scr. 2007, 89, 2589–2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannattasio, A.; Yao, Z.; Tarleton, E.; Roberts, S. Brittle-ductile transitions in polycrystalline tungsten [J]. Philos. Mag. 2010, 90, 3947–3959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. H.; Han, W. Z. Mechanism of brittle-to-ductile transition in tungsten under small-punch testing. Acta. Mater. 2021, 220, 117332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duesbery, M. S.; Vitek, V. Plastic anisotropy in bcc transition metals. Acta. Mater. 1998, 46, 1481–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrovec, M.; Gröger, R.; Bailey, A. G. Bond-order potential for simulations of extended defects in tungsten. Phys. Rev. B 2007, 75, 104119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitek, V. Core structure of screw dislocations in body-centred cubic metals: relation to symmetry and interatomic bonding. Philos. Mag. 2004, 84, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottrell, A. H. Theory of brittle fracture in steel and similar metals. Trans. Met. Soc. AIME 1958, 212. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, B. G.; Paramore, J. D.; Ligda, J. P. Mechanisms of deformation and ductility in tungsten–A review. Int. J. Refract. Met. 2018, 75, 248–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinzato, S.; Wakeda, M.; Ogata, S. An atomistically informed kinetic Monte Carlo model for predicting solid solution strengthening of body-centered cubic alloys. Int. J. Plast. 2019, 122, 319–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weertman, J. Dislocation Model of Low-Temperature Creep. J. Appl. Phys. 1958, 29, 1685–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Marian, J. Direct prediction of the solute softening-to-hardening transition in W-Re alloys using stochastic simulations of screw dislocation motion [J]. Model. Simul. Mater. Sc. 2018, 26, 045002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caillard, D. On the stress discrepancy at low-temperatures in pure iron. Acta. Mater. 2014, 62, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsenault, R. The double-kink model for low-temperature deformation of BCC metals and solid solutions. Acta. Metall. 1967, 15, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medvedeva, N.; Gornostyrev, Y. N.; Freeman, A. J. Solid solution softening in bcc Mo alloys: Effect of transition-metal additions on dislocation structure and mobility. Phys. Rev. B 2005, 72, 134107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, A.; Meshii, M. Solid solution softening and solid solution hardening. Acta. Metall. 1973, 21, 753–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maresca, F.; Curtin, W. A. Theory of screw dislocation strengthening in random BCC alloys from dilute to “High-Entropy” alloys. Acta. Mater. 2020, 182, 144–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, A.; Jacobson, D.; Shin, K. Solution softening mechanism of iridium and rhenium in tungsten at room temperature. Int. J. Refract. Met. H. 1991, 10, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, J. R.; Witzke, W. R. Alloy softening in group via metals alloyed with rhenium. J. Less. Common. Met. 1971, 23, 325–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, J. R.; Witzke, W. R. Alloy softening in binary iron solid solutions. J. Less. Common. Met. 1976, 48, 285–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T. Watanabe, S. The temperature dependence of the yield stress and solid solution softening in Fe Ni and Fe Si alloys. Acta. Metall. 1971, 19, 991–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocks, U.; Argon, A.; Ashby, M. Models for macroscopic slip. Prog. Mater. Sci. 1975, 19, 171–185. [Google Scholar]

- Itakura, M.; Kaburaki, H.; Yamaguchi, M. First-principles study on the mobility of screw dislocations in bcc iron. Acta. Metall. 2012, 60, 3698–3710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita, K.; Shimokawa, T.; Kinari, T. Influence of non-glide stresses on the peierls energy of screw dislocations. Trans. JSME 2014, 80, CM0018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventelon, L.; Willaime, F.; Clouet, E.; Sawada, H.; Kawakami, K. Ab initio investigation of the Peierls potential of screw dislocations in bcc Fe and W. Acta. Mater. 2013, 61, 3973–3985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y. J.; Fellinger, M. R.; Butler, B. G.; Wang, Y.; Darling, K. A. Solute-induced solid-solution softening and hardening in bcc tungsten. Acta. Mater. 2017, 141, 304–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romaner, L.; Ambrosch-Draxl, C.; Pippan, R. Effect of rhenium on the dislocation core structure in tungsten. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 104, 195503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L. P.; Liu, Y.; Zhi, J. G.; Zhang, J.S.; Liu, Q. Effect mechanism of rare earth Ce on the strength and toughness of C-Mn low-temperature steel. Rare. Matel. Mat. Eng. 2022, 51, 4561–4569. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, M.; Matsuo, K.; Yoshimura, N.; Shigesato, G.; Hoshino, M. Effects of Ni and Mn on brittle-to-ductile transition in ultralow-carbon steels. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2017, 682, 370–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uenishi, A.; Teodosiu, C. Solid solution softening at high strain rates in Si-and/or Mn-added interstitial free steels. Acta. Mater. 2003, 51, 4437–4446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).