Submitted:

05 May 2025

Posted:

06 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Types, Applications, and Recent Advances of Piezoelectric Shunt Circuits

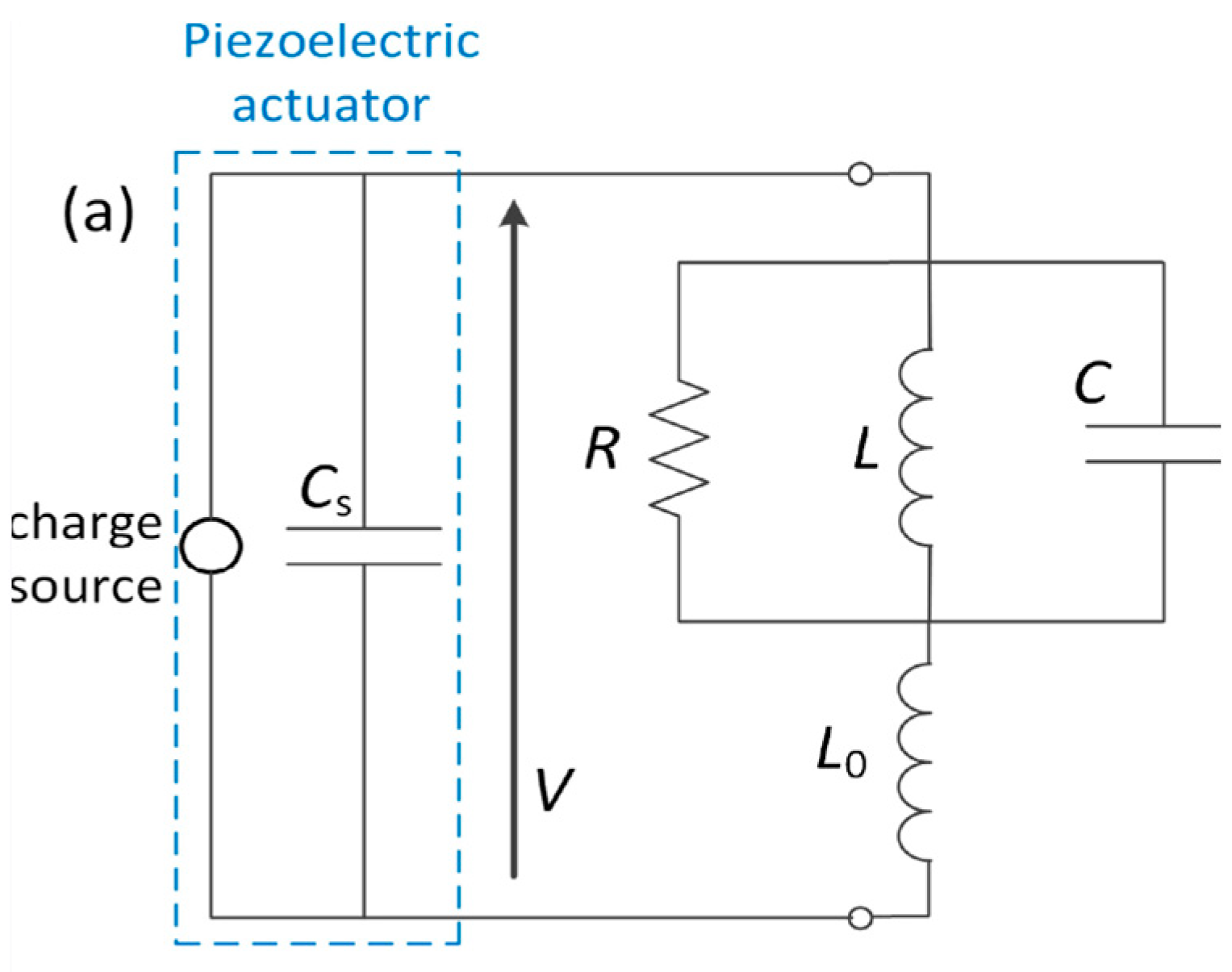

2.1. Single-Mode Resistive (R), Resonant (RL), and (RLC) Circuits

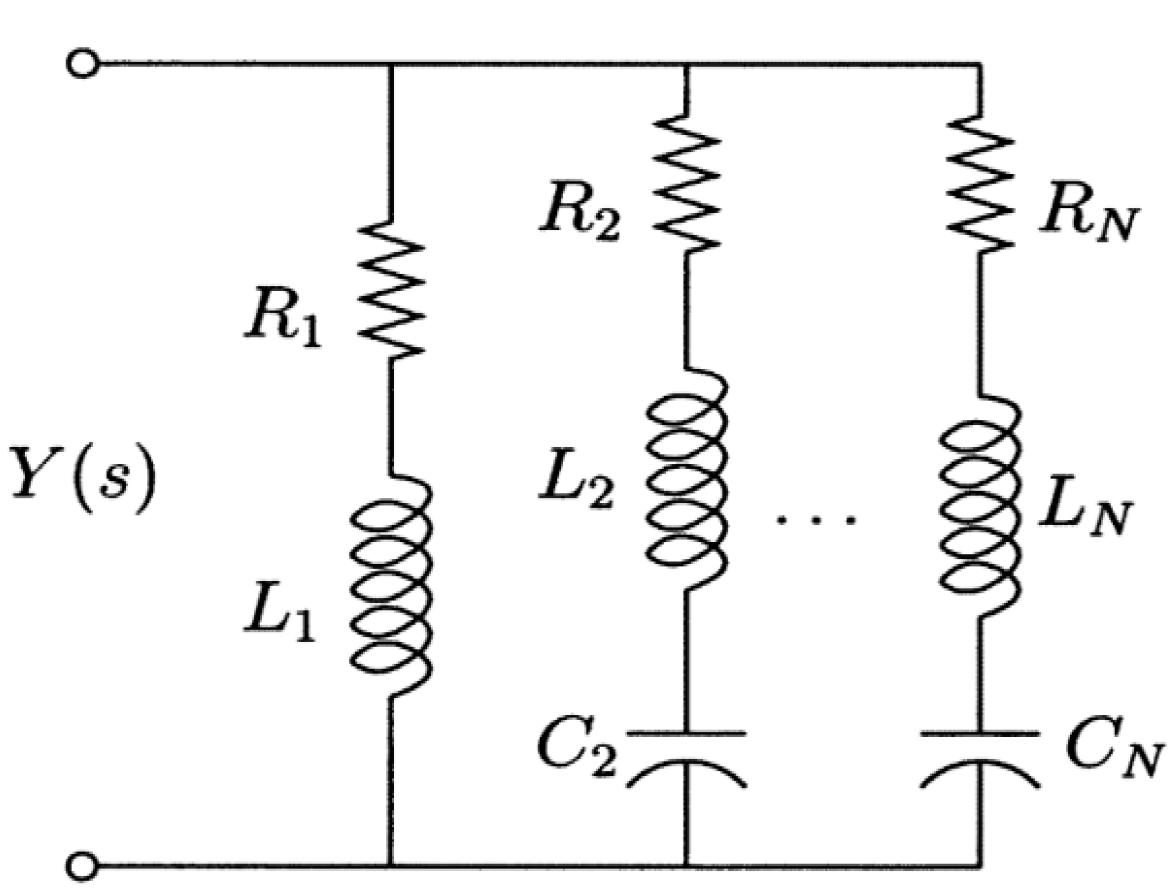

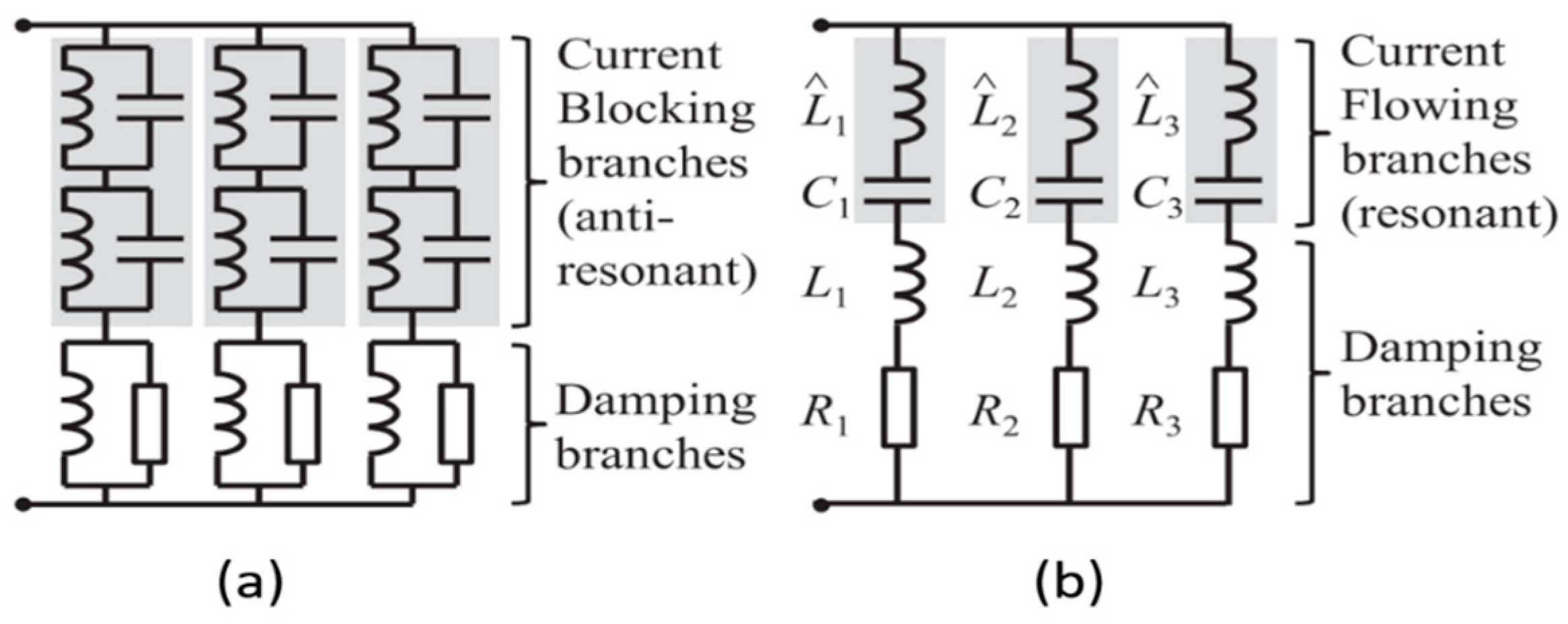

2.2. Multi-Mode Resonant (RL) Circuits

2.3. Negative Capacitance Shunt Circuits

2.4. Switching Circuits

2.5. Quadratic and Cubic Nonlinear Shunt Circuits

3. Modelling of Dynamical Systems with Piezoelectric Shunt Circuits

3.1. Lumped-Parameter Systems

| Circuit Name | Circuit Configuration | Total Impedance | Characteristics | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

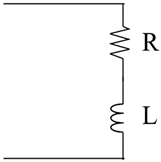

| R circuit |  |

Passive control Single-mode It behaves similarly to a Viscoelastically damped system. |

[12] | |

| RL circuit in series |  |

Passive control Single-mode. It creates an electrical frequency that can be tuned to the structure's natural frequency to induce antiresonance |

[12] | |

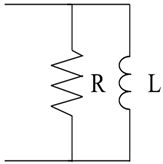

| RL Circuit in parallel |  |

Passive control Single-mode |

[17] | |

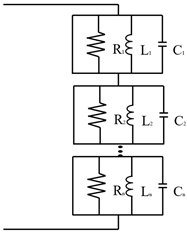

| parallelRLC Circuit in series |

|

Passive control Multi-mode |

[105] | |

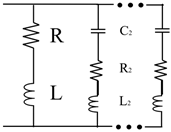

| Series RLC circuit in parallel |

|

|

Passive control Multi-mode |

[39] |

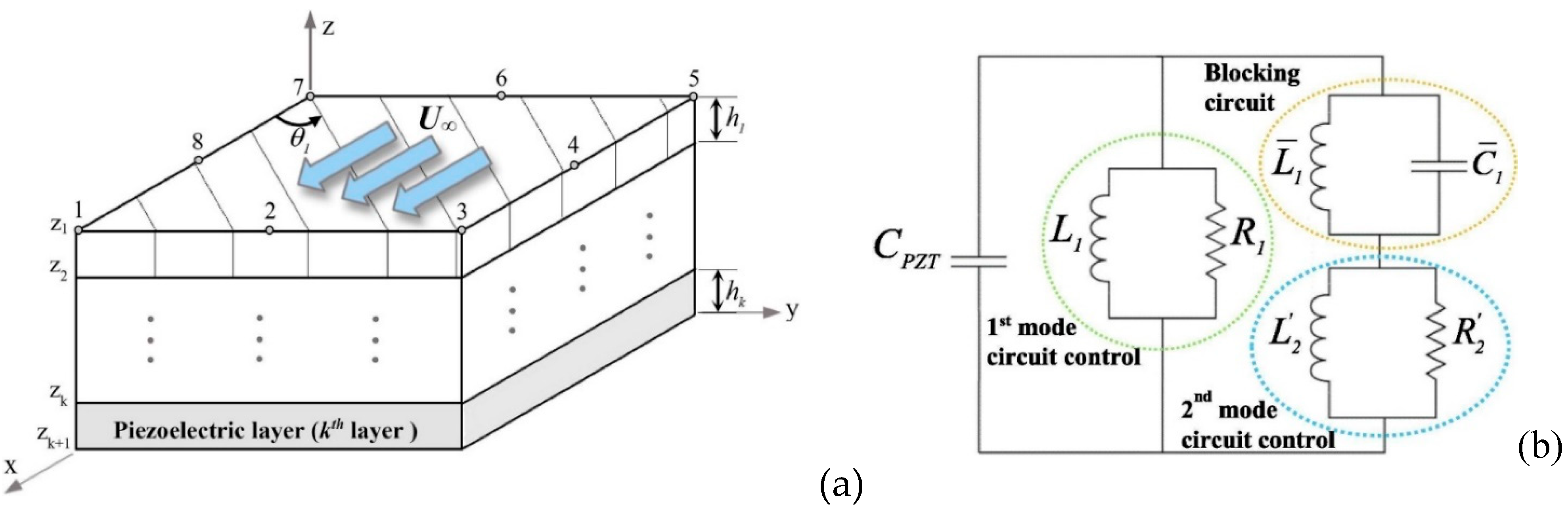

3.2. Distributed-Parameter Systems

3.3. Inducing Internal Resonances into the System

4. Conclusions and Future Work

References

- J.A.B. Gripp and D.A. Rade, Vibration and noise control using shunted piezoelectric transducers: A review, Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, vol. 112, pp. 359-383, 2018.

- Marakakis, Georgios K. Tairidis, Panagiotis Koutsianitis and Georgios E. Stavroulakis, Shunt Piezoelectric Systems for Noise and Vibration Control: A Review, Konstantinos, Frontiers in Built Environment, vol. 5, Article 64, 2019.

- H. A. Sodano, D. J. H. A. Sodano, D. J. Inman and G. Park, "A review of power harvesting from vibration using piezoelectric materials," Shock Vib Dig, vol. 36, (3), pp. 197–206, 2004.

- M. Zhu, Q. M. Zhu, Q. Shi, T. He, Z. Yi, Y. Ma, B. Yang, T. Chen, and C. Lee, "Self-Powered and Self-Functional Cotton Sock Using Piezoelectric and Triboelectric Hybrid Mechanism for Healthcare and Sports Monitoring," ACS Nano, vol. 13, (2), pp. 1940–1952, 2019. [CrossRef]

- W. Deng, Z. W. Deng, Z. Yihao, A. Libanori, G. Chen, W. Yang, and J. Chen, "Piezoelectric nanogenerators for personalized healthcare," Chem. Soc. Rev., vol. 51, (9), pp. 3380–3435, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Erturk and D., J. Inman, Piezoelectric Energy Harvesting. 2011.

- H. S. Tzou and C. I. Tseng, "Distributed piezoelectric sensor/actuator design for dynamic measurement/control of distributed parameter systems: a piezoelectric finite element approach," J. Sound Vibrat., vol. 138, (1), pp. 17–34, 1990.

- R. L. Forward, "Electronic damping of vibrations in optical structures," Appl. Opt., vol. 18, (5), pp. 690–697, 1979. Available: https://opg.optica.org/ao/abstract.cfm?URI=ao-18-5-690. [CrossRef]

- D. D. L. Chung, "Review: Materials for vibration damping," J. Mater. Sci., vol. 36, (24), pp. 5733–5737, 2001. [CrossRef]

- H. Ji, J. H. Ji, J. Qiu, Y. Wu, and C. Zhang, "Semi-active vibration control based on synchronously switched piezoelectric actuators," Int. J. Appl. Electromagn. Mech., vol. 59, pp. 299–307, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Baz, "Vibration Damping," pp. 1–10, 2018. [CrossRef]

- N. W. Hagood and A. von Flotow, "Damping of structural vibrations with piezoelectric materials and passive electrical networks," J. Sound Vibrat., vol. 146, (2), pp. 243–268, 1991. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0022460X91907629. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J. Ducarne and J. Deü, "Performance of piezoelectric shunts for vibration reduction," Smart Mater. Struct., vol. 21, (1), pp. 015008, 2011.

- K. Yamada, "Complete passive vibration suppression using multi-layered piezoelectric element, inductor, and resistor," J. Sound Vibrat., vol. 387, pp. 16–35, 2017. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022460X16305417. [CrossRef]

- B. Lossouarn et al, "Design of inductors with high inductance values for resonant piezoelectric damping," Sensors and Actuators A: Physical, vol. 259, pp. 68–76, 2017. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0924424716309785. [CrossRef]

- H. Park, "Dynamics modelling of beams with shunt piezoelectric elements," J. Sound Vibrat., vol. 268, (1), pp. 115–129, 2003. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022460X02014918. [CrossRef]

- S. Wu, "Piezoelectric shunts with a parallel RL circuit for structural damping and vibration control," in Smart Structures and Materials 1996: Passive Damping and Isolation, 1996.

- R. Darleux, B. R. Darleux, B. Lossouarn and J. Deü, "Passive self-tuning inductor for piezoelectric shunt damping considering temperature variations," J. Sound Vibrat., vol. 432, pp. 105–118, 2018.

- L. Pernod et al, "Vibration damping of marine lifting surfaces with resonant piezoelectric shunts," J. Sound Vibrat., vol. 496, pp. 115921, 2021.

- X. Liu et al, "Improving aeroelastic stability of bladed disks with topologically optimized piezoelectric materials and intentionally mistuned shunt capacitance," Materials, vol. 15, (4), pp. 1309, 2022.

- Y. G. Wu et al, "Design of dry friction and piezoelectric hybrid ring dampers for integrally bladed disks based on complex nonlinear modes," Comput. Struct., vol. 233, pp. 106237, 2020.

- M. Morad, M. M. Morad, M. Kamel and M. K. Khalil, "Vibration damping of aircraft propeller blades using shunt piezoelectric transducers," in IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 2021.

- Wang, G. Yao and M. Liu, "Passive vibration control of subsonic thin plate via nonlinear capacitance and negative capacitance coupled piezoelectric shunt damping," Thin-Walled Structures, vol. 198, pp. 111656, 2024.

- K. Yamada et al, "Optimum tuning of series and parallel LR circuits for passive vibration suppression using piezoelectric elements," J. Sound Vibrat., vol. 329, (24), pp. 5036–5057, 2010. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022460X10004116. [CrossRef]

- G. K. Rodrigues et al, "Piezoelectric patch vibration control unit connected to a self-tuning RL-shunt set to maximise electric power absorption," J. Sound Vibrat., vol. 536, pp. 117154, 2022.

- C. Sugino, M. C. Sugino, M. Ruzzene and A. Erturk, "Design and analysis of piezoelectric metamaterial beams with synthetic impedance shunt circuits," IEEE/ASME Transactions on Mechatronics, vol. 23, (5), pp. 2144–2155, 2018.

- T. Ikegame, K. T. Ikegame, K. Takagi and T. Inoue, "Exact solutions to H∞ and H2 optimizations of passive resonant shunt circuit for electromagnetic or piezoelectric shunt damper," Journal of Vibration and Acoustics, vol. 141, (3), pp. 031015, 2019.

- S. Dai, Y. S. Dai, Y. Zheng and Y. Qu, "Programmable piezoelectric meta-rings with high-order digital circuits for suppressing structural and acoustic responses," Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, vol. 200, pp. 110517, 2023.

- Heuss et al, "Tuning of a vibration absorber with shunt piezoelectric transducers," Arch Appl Mech, vol. 86, pp. 1715–1732, 2016.

- V. P. Matveenko et al, "An approach to determination of shunt circuits parameters for damping vibrations," International Journal of Smart and Nano Materials, vol. 9, (2), pp. 135–149, 2018.

- J. F. Toftekær, A. J. F. Toftekær, A. Benjeddou and J. Høgsberg, "General numerical implementation of a new piezoelectric shunt tuning method based on the effective electromechanical coupling coefficient," Mechanics of Advanced Materials and Structures, vol. 27, (22), pp. 1908–1922, 2020.

- P. Gardonio et al, "Extremum seeking online tuning of a piezoelectric vibration absorber based on the maximisation of the shunt electric power absorption," Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, vol. 176, pp. 109171, 2022.

- J. Jeon, "Passive vibration damping enhancement of piezoelectric shunt damping system using optimization approach," J Mech Sci Technol, vol. 23, (5), pp. 1435–1445, 2009. Available: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12206-009-0402-8. [CrossRef]

- J. Jeon, "Passive acoustic radiation control for a vibrating panel with piezoelectric shunt damping circuit using particle swarm optimization algorithm," Journal of Mechanical Science and Technology, vol. 23, pp. 1446–1455, 2009.

- N. Wahid, A. G. N. Wahid, A. G. Muthalif and K. A. Nor, "Investigating negative capacitance shunt circuit for broadband vibration damping and utilizing ACO for optimization," Int.J.Circuits Electron, vol. 1, pp. 168–173, 2016.

- G. Caruso, "A critical analysis of electric shunt circuits employed in piezoelectric passive vibration damping," Smart Mater. Struct., vol. 10, (5), pp. 1059, 2001.

- P. Soltani et al, "Piezoelectric vibration damping using resonant shunt circuits: an exact solution," Smart Mater. Struct., vol. 23, (12), pp. 125014, 2014.

- S. Wu, "Method for multiple-mode shunt damping of structural vibration using a single PZT transducer," in Smart Structures and Materials 1998: Passive Damping and Isolation, 1998.

- J. J. Hollkamp, "Multimodal passive vibration suppression with piezoelectric materials and resonant shunts," J Intell Mater Syst Struct, vol. 5, (1), pp. 49–57, 1994.

- S. Wu, "Method for multiple mode piezoelectric shunting with single PZT transducer for vibration control," J Intell Mater Syst Struct, vol. 9, (12), pp. 991–998, 1998.

- S. Behrens, A. J. S. Behrens, A. J. Fleming and S. Moheimani, "A broadband controller for shunt piezoelectric damping of structural vibration," Smart Mater. Struct., vol. 12, (1), pp. 18, 2003.

- S. Behrens, S. R. S. Behrens, S. R. Moheimani and A. J. Fleming, "Multiple mode current flowing passive piezoelectric shunt controller," J. Sound Vibrat., vol. 266, (5), pp. 929–942, 2003.

- F. dell’Isola, C. F. dell’Isola, C. Maurini and M. Porfiri, "Passive damping of beam vibrations through distributed electric networks and piezoelectric transducers: prototype design and experimental validation," Smart Mater. Struct., vol. 13, (2), pp. 299, 2004.

- J. Fleming and S. R. Moheimani, "Control orientated synthesis of high-performance piezoelectric shunt impedances for structural vibration control," IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol., vol. 13, (1), pp. 98–112, 2004.

- G. K. Tairidis, "Vibration control of smart composite structures using shunt piezoelectric systems and neuro-fuzzy techniques," J. Vibrat. Control, vol. 25, (18), pp. 2397–2408, 2019.

- G. Raze, A. G. Raze, A. Paknejad, G. Zhao, C. Collette, and G. Kerschen, "Multimodal vibration damping using a simplified current blocking shunt circuit," J Intell Mater Syst Struct, vol. 31, (14), pp. 1731–1747, 2020.

- G. Raze, J. G. Raze, J. Dietrich and G. Kerschen, "Passive control of multiple structural resonances with piezoelectric vibration absorbers," J. Sound Vibrat., vol. 515, pp. 116490, 2021.

- L. P. Ribeiro and A. M. G. de Lima, "Robust passive control methodology and aeroelastic behavior of composite panels with multimodal shunt piezoceramics in parallel," Composite Structures, vol. 262, pp. 113348, 2021.

- G. A. Lesieutre, "Vibration damping and control using shunt piezoelectric materials," Shock Vib Dig, vol. 30, (3), pp. 187–195, 1998.

- Tylikowski, "Control of circular plate vibrations via piezoelectric actuators shunt with a capacitive circuit," Thin-Walled Structures, vol. 39, (1), pp. 83–94, 2001.

- H. Park, K. H. Park, K. Kabeya and D. J. Inman, "Enhanced piezoelectric shunt design," in ASME International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition, 1998,.

- H. Park and D. J. Inman, "Enhanced piezoelectric shunt design," Shock Vibrat., vol. 10, (2), pp. 127–133, 2003.

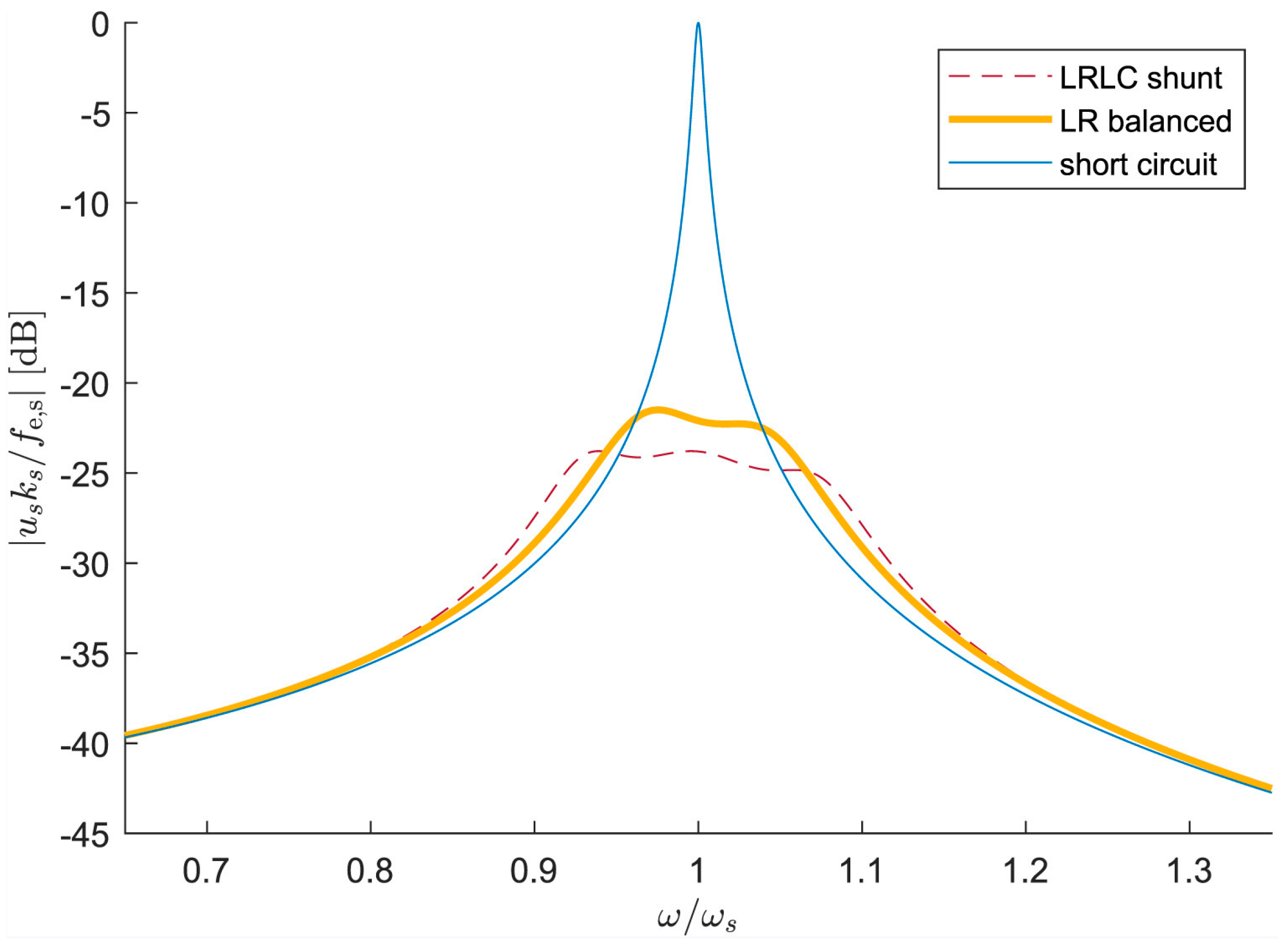

- M. Berardengo et al, "LRLC-shunt piezoelectric vibration absorber," J. Sound Vibrat., vol. 474, pp. 115268, 2020.

- C. H. Park and H. C. Park, "Multiple-mode structural vibration control using negative capacitive shunt damping," KSME International Journal, vol. 17, pp. 1650–1658, 2003.

- K. Billon, N. K. Billon, N. Montcoudiol, A. Aubry, R. Pascual, F. Mosco, F. Jean, C. Pezerat, C. Bricault, and S. Chesne, "Vibration isolation and damping using a piezoelectric flextensional suspension with a negative capacitance shunt," Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, vol. 140, pp. 106696, 2020.

- M. Pohl, "An adaptive negative capacitance circuit for enhanced performance and robustness of piezoelectric shunt damping," J Intell Mater Syst Struct, vol. 28, (19), pp. 2633–2650, 2017.

- M. Berardengo, S. M. Berardengo, S. Manzoni, O. Thomas, C. Giraud-Audine, L. Drago, S. Marelli, M. Vanali, "The reduction of operational amplifier electrical outputs to improve piezoelectric shunts with negative capacitance," J. Sound Vibrat., vol. 506, pp. 116163, 2021.

- T. Wang, J. T. Wang, J. Dupont and J. Tang, "On integration of vibration suppression and energy harvesting through piezoelectric shunting with negative capacitance," IEEE/ASME Transactions on Mechatronics, vol. 28, (5), pp. 2621–2632, 2023.

- Y. G. Wu, H. Y. G. Wu, H. Wang, Y. Fan, L. Li, "On the network of synchronized switch damping for blisks," Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, vol. 184, pp. 109695, 2023.

- G. D. Larson, The Analysis and Realization of a State-Switched Acoustic Transducer. 1996.

- C. Richard et al, "Semi-passive damping using continuous switching of a piezoelectric device," in Smart Structures and Materials 1999: Passive Damping and Isolation, 1999,.

- C. Richard, D. C. Richard, D. Guyomar, D. Audigier, H. Bassaler, "Enhanced semi-passive damping using continuous switching of a piezoelectric device on an inductor," in Smart Structures and Materials 2000: Damping and Isolation, 2000,.

- W. W. Clark, "Semi-active vibration control with piezoelectric materials as variable-stiffness actuators," in Smart Structures and Materials 1999: Passive Damping and Isolation, 1999,.

- W. W. Clark, "Vibration control with state-switched piezoelectric materials," J Intell Mater Syst Struct, vol. 11, (4), pp. 263–271, 2000.

- Y. Wu, L. Y. Wu, L. Li, Y. Fan, J. Liu, Q. Gao, "A linearised analysis for structures with synchronized switch damping," IEEE Access, vol. 7, pp. 133668–133685, 2019.

- J. Liu, L. J. Liu, L. Li and Y. Fan, "A comparison between the friction and piezoelectric synchronized switch dampers for blisks," J Intell Mater Syst Struct, vol. 29, (12), pp. 2693–2705, 2018.

- R. Qi, L. R. Qi, L. Wang, J. Jin, L. Yuan, D. Zhang, Y. Ge, "Enhanced Semi-active piezoelectric vibration control method with shunt circuit by energy dissipations switching," Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, vol. 201, pp. 110671, 2023.

- D. Guyomar, C. D. Guyomar, C. Richard and L. Petit, "Non-linear system for vibration damping," in 142th Meeting of Acoustical Society of America, 2001,.

- L. R. Corr and W. W. Clark, "A novel semi-active multi-modal vibration control law for a piezoceramic actuator," J.Vib.Acoust., vol. 125, (2), pp. 214–222, 2003.

- H. Ji, J. H. Ji, J. Qiu, and K. Zhu, "Semi-active vibration control of a composite beam using an adaptive SSDV approach," J Intell Mater Syst Struct, vol. 20, (4), pp. 401–412, 2009.

- C. R. Kelley and J. L. Kauffman, "Adaptive synchronized switch damping on an inductor: a self-tuning switching law," Smart Mater. Struct., vol. 26, (3), pp. 035032, 2017.

- F. Yu et al, "Mechanism of interconnected synchronized switch damping for vibration control of blades," Chinese Journal of Aeronautics, vol. 36, (8), pp. 207–228, 2023.

- L. Petit et al, "A broadband semi passive piezoelectric technique for structural damping," in Smart Structures and Materials 2004: Damping and Isolation, 2004,.

- E. Lefeuvre et al, "Semi-passive piezoelectric structural damping by synchronized switching on voltage sources," J Intell Mater Syst Struct, vol. 17, (8-9), pp. 653–660, 2006.

- Faiz et al, "Wave transmission reduction by a piezoelectric semi-passive technique," Sensors and Actuators A: Physical, vol. 128, (2), pp. 230–237, 2006.

- Badel et al, "Piezoelectric vibration control by synchronized switching on adaptive voltage sources: Towards wideband semi-active damping," J. Acoust. Soc. Am., vol. 119, (5), pp. 2815–2825, 2006.

- Bao and, W. Tang, "Semi-active vibration control featuring a self-sensing SSDV approach," Measurement, vol. 104, pp. 192–203, 2017.

- L. Zheng et al, "Semi-active vibration control of the motorized spindle using a self-powered SSDV technique: simulation and experimental study," Automatika: Časopis Za Automatiku, Mjerenje, Elektroniku, Računarstvo i Komunikacije, vol. 63, (3), pp. 511–524, 2022.

- H. Ji et al, "Application of a negative capacitance circuit in synchronized switch damping techniques for vibration suppression," 2011.

- J. Cheng et al, "Semi-active vibration suppression by a novel synchronized switch circuit with negative capacitance," Int. J. Appl. Electromagn. Mech., vol. 37, (4), pp. 291–308, 2011.

- W. Tang et al, "Design and experimental analysis of self-sensing SSDNC technique for semi-active vibration control," Smart Mater. Struct., vol. 27, (8), pp. 085028, 2018.

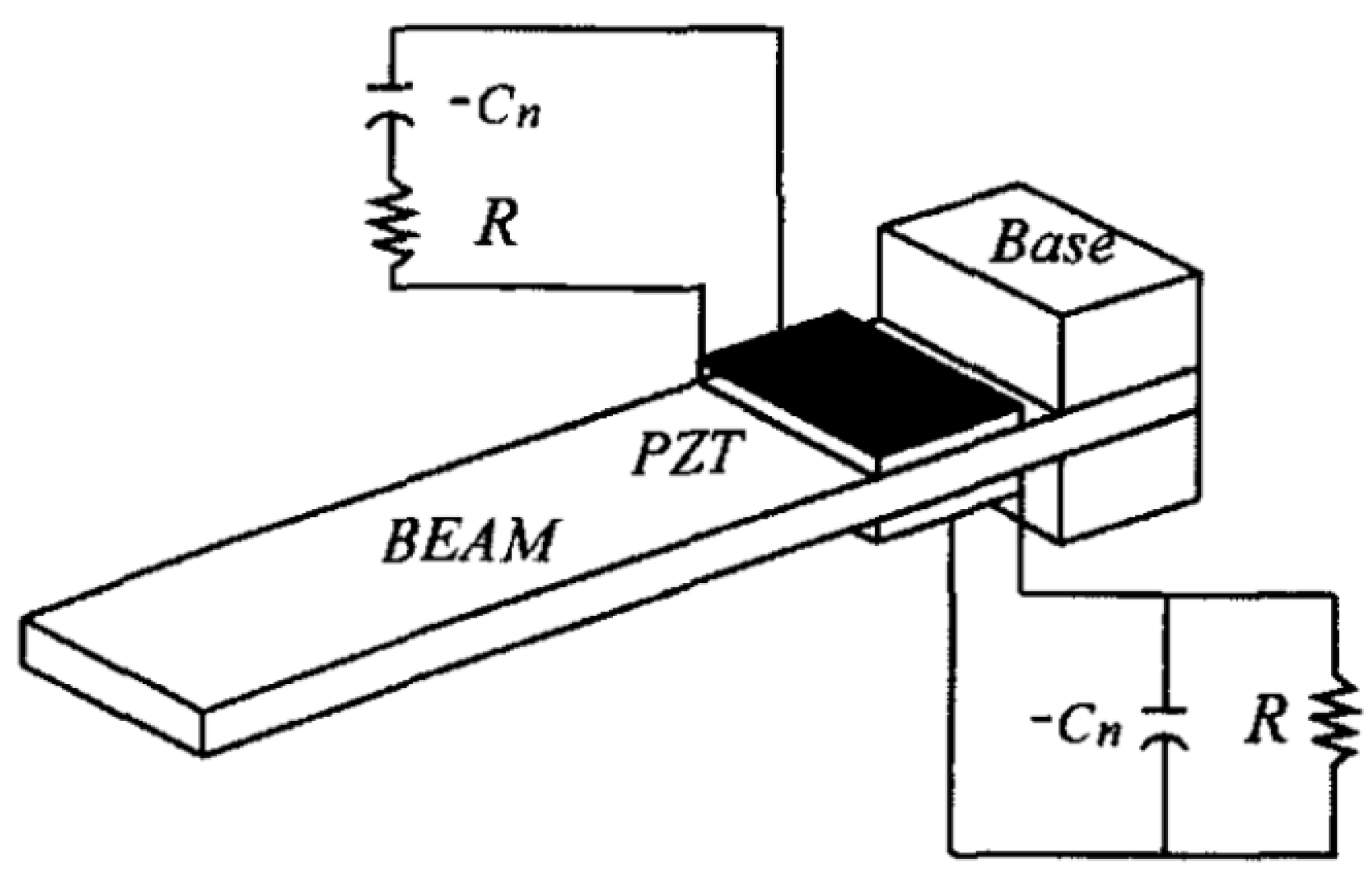

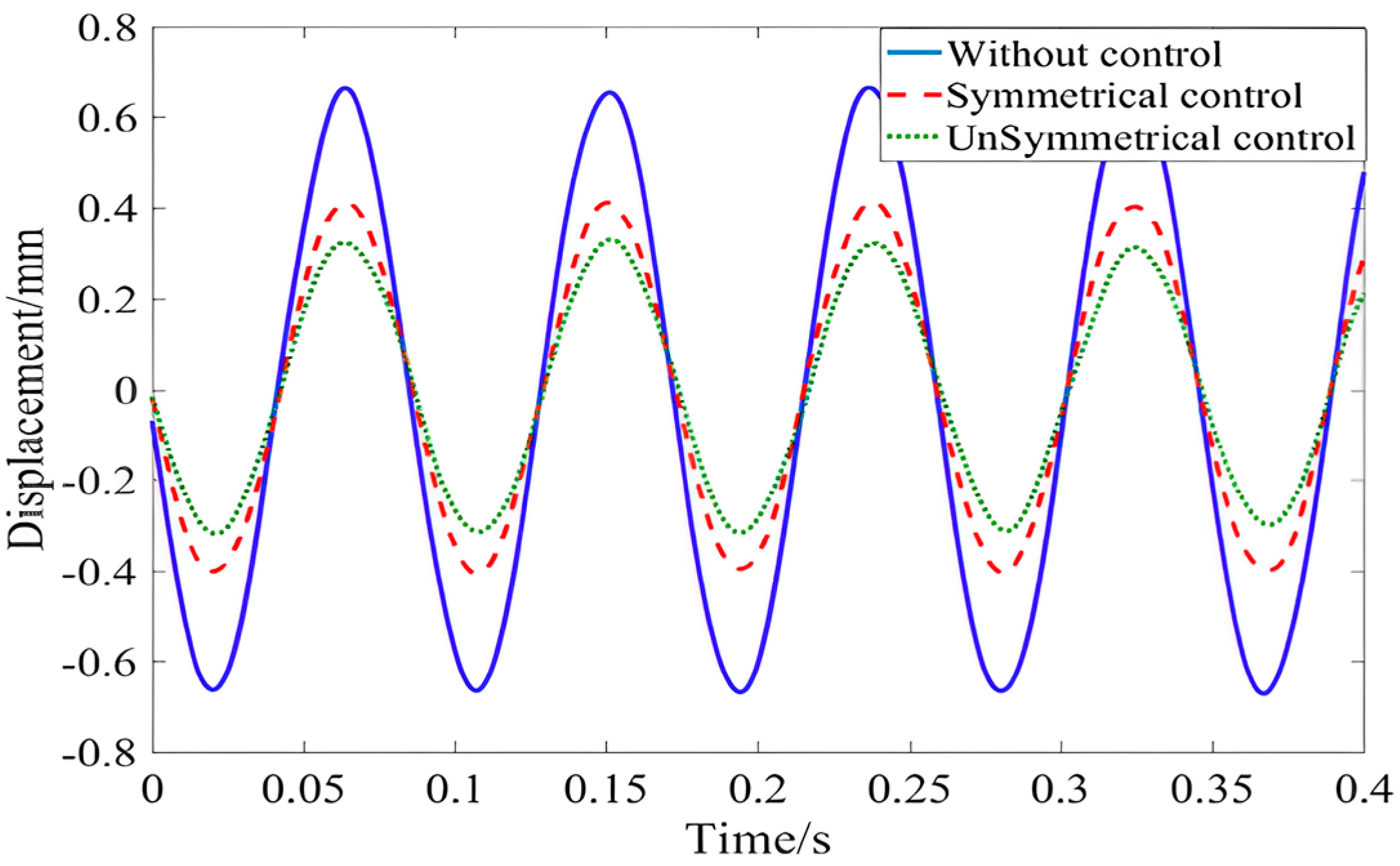

- H. Ji et al, "A new design of unsymmetrical shunt circuit with negative capacitance for enhanced vibration control," Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, vol. 155, pp. 107576, 2021.

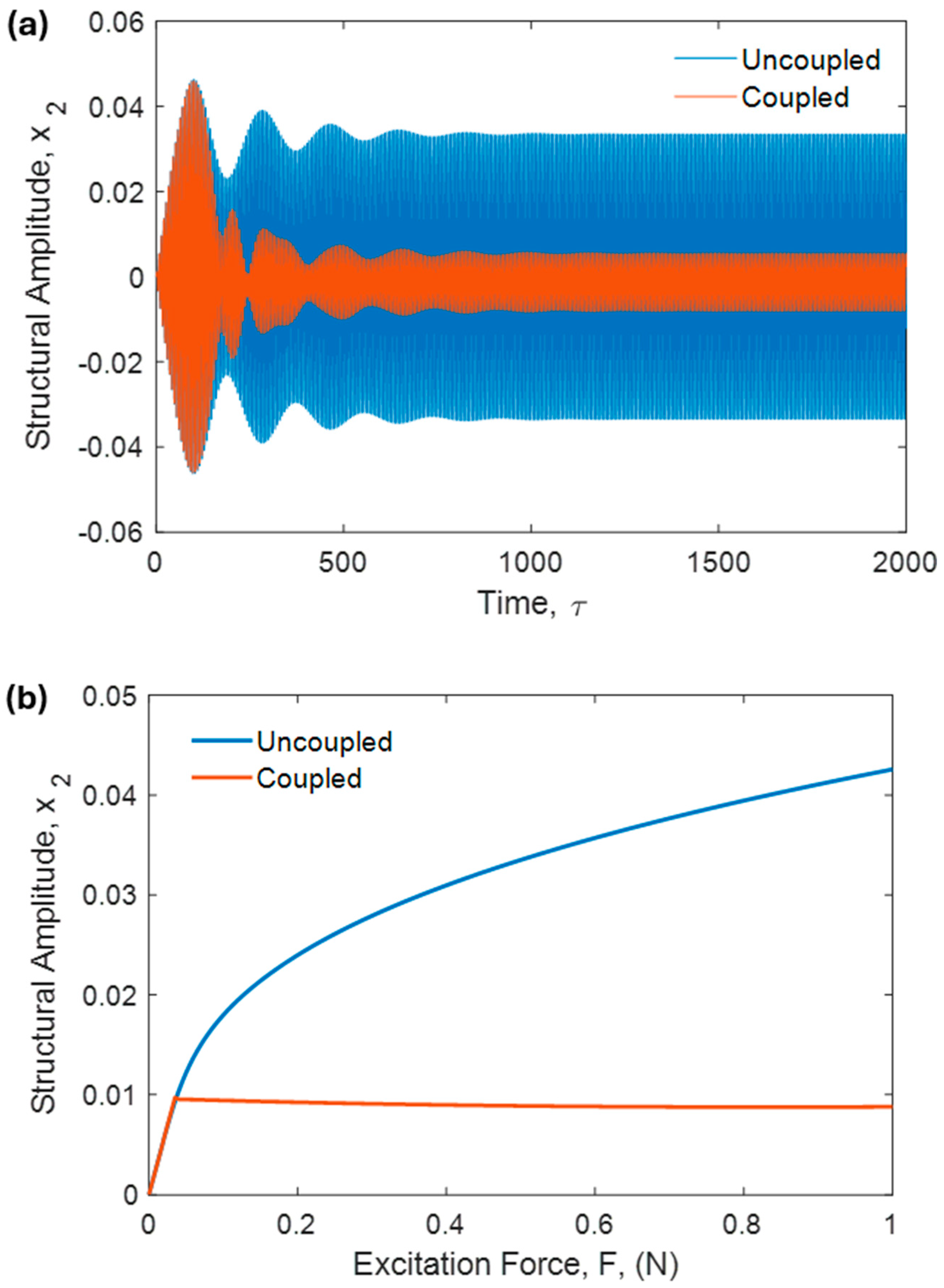

- G. S. Agnes and D. J. Inman, "Nonlinear piezoelectric vibration absorbers," Smart Mater. Struct., vol. 5, (5), pp. 704, 1996.

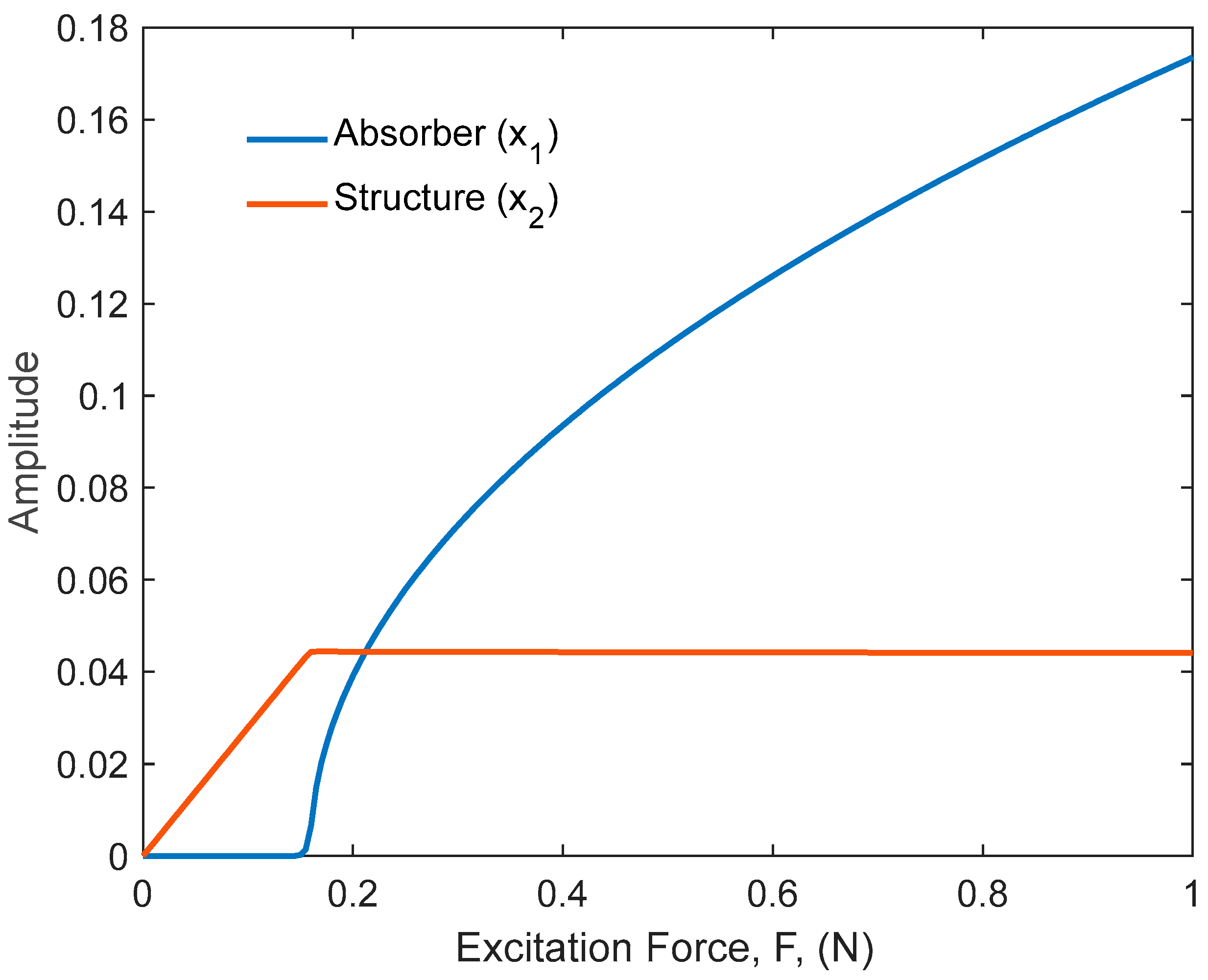

- P. Soltani and G. Kerschen, "The nonlinear piezoelectric tuned vibration absorber," Smart Mater. Struct., vol. 24, (7), pp. 075015, 2015.

- Lossouarn, J. Deü and G. Kerschen, "A fully passive nonlinear piezoelectric vibration absorber," Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, vol. 376, (2127), pp. 20170142, 2018.

- B. Lossouarn, G. Kerschen and J. Deü, "An analogue twin for piezoelectric vibration damping of multiple nonlinear resonances," J. Sound Vibrat., vol. 511, pp. 116323, 2021.

- G. Raze et al, "A digital nonlinear piezoelectric tuned vibration absorber," Smart Mater. Struct., vol. 29, (1), pp. 015007, 2019.

- Alfahmi, C. Sugino and A. Erturk, "Duffing-type digitally programmable nonlinear synthetic inductance for piezoelectric structures," Smart Mater. Struct., vol. 31, (9), pp. 095044, 2022.

- Alfahmi and, A. Erturk, "Programmable hardening and softening cubic inductive shunts for piezoelectric structures: Harmonic balance analysis and experiments," J. Sound Vibrat., vol. 571, pp. 118029, 2024.

- X. F. Geng, H. Ding, J. C. Ji, K. X. Wei, X. J. Jing, L. Q. Chen, ”A state-of-the-art review on the dynamic design of nonlinear energy sinks, Eng. Struct., vol. 313, 118228, 2024.

- R. Viguié, G. Kerschen and M. Ruzzene, "Exploration of nonlinear shunting strategies as effective vibration absorbers," in Active and Passive Smart Structures and Integrated Systems 2009, 2009.

- B. Zhou, F. Thouverez and D. Lenoir, "Essentially nonlinear piezoelectric shunt circuits applied to mistuned bladed disks," J. Sound Vibrat., vol. 333, (9), pp. 2520–2542, 2014.

- T. M. Silva et al, "An experimentally validated piezoelectric nonlinear energy sink for wideband vibration attenuation," J. Sound Vibrat., vol. 437, pp. 68–78, 2018.

- K. Dekemele, C. Giraud-Audine and O. Thomas, "A piezoelectric nonlinear energy sink shunt for vibration damping," Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, vol. 220, pp. 111615, 2024.

- K. Zhou and Z. Hu, "Vibration suppression on the composite laminated plates subjected to aerodynamic and harmonic excitations based on the nonlinear piezoelectric shunt damping," Appl. Math. Model., vol. 121, pp. 134–165, 2023.

- F. Mangussi and D. H. Zanette, "Internal resonance in a vibrating beam: a zoo of nonlinear resonance peaks," PloS One, vol. 11, (9), pp. e0162365, 2016.

- H. Nayfeh, D. T. Mook and L. R. Marshall, "Nonlinear coupling of pitch and roll modes in ship motions," Journal of Hydronautics, vol. 7, (4), pp. 145–152, 1973.

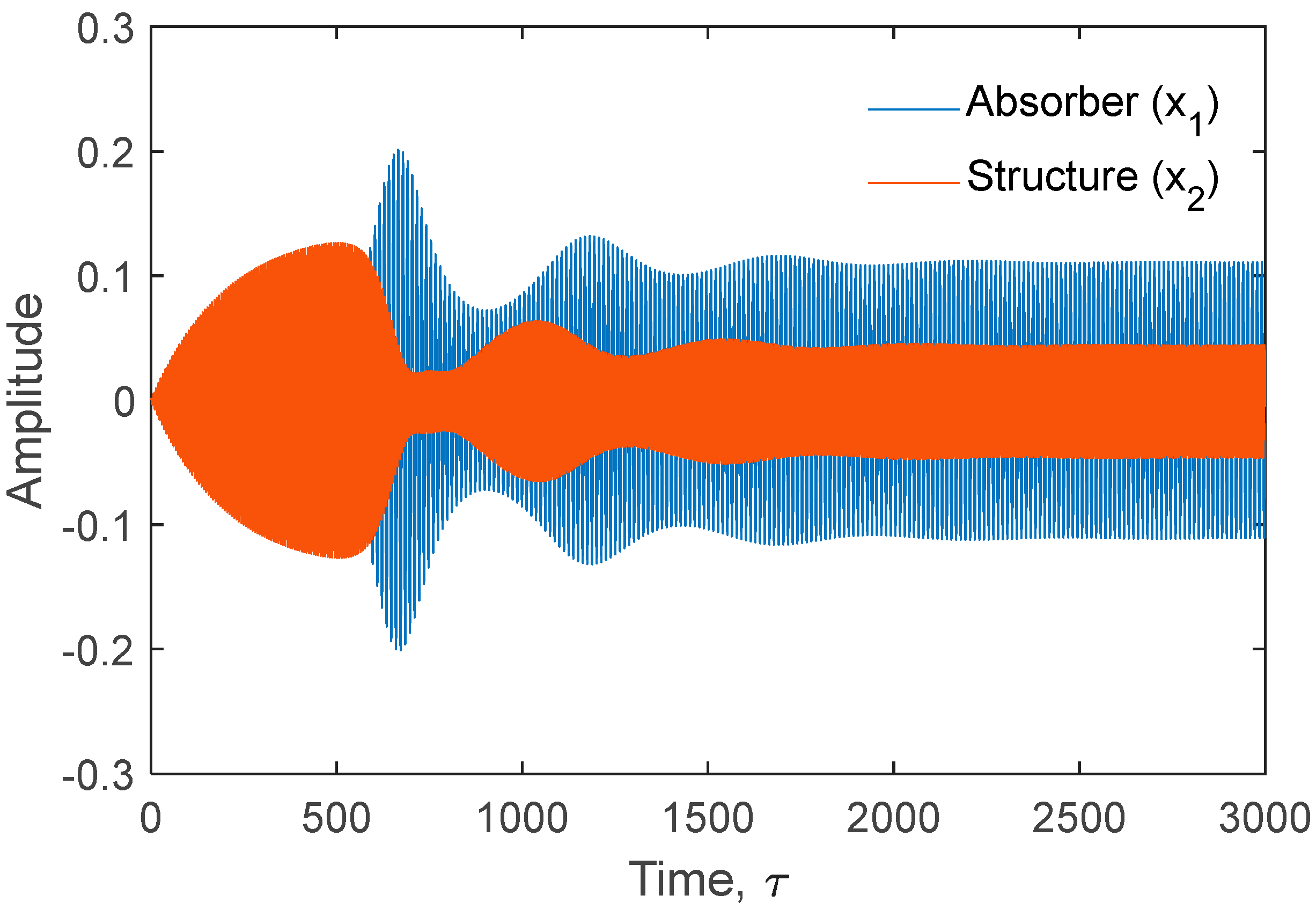

- Z. A. Shami, C. Giraud-Audine and O. "A nonlinear piezoelectric shunt absorber with 2: 1 internal resonance: experimental proof of concept," Smart Mater. Struct., vol. 31, (3), pp. 035006, 2022.

- Z. A. Shami, C. Giraud-Audine and O. Thomas, "A nonlinear piezoelectric shunt absorber with a 2: 1 internal resonance: theory," Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, vol. 170, pp. 108768, 2022.

- Z. A. Shami et al, "Nonlinear dynamics of coupled oscillators in 1: 2 internal resonance: effects of the non-resonant quadratic terms and recovery of the saturation effect," Meccanica, vol. 57, (11), pp. 2701–2731, 2022.

- Z. A. Shami, C. Giraud-Audine and O. Thomas, "Saturation correction for a piezoelectric shunt absorber based on 2: 1 internal resonance using a cubic nonlinearity," Smart Mater. Struct., vol. 32, (5), pp. 055024, 2023.

- K. Al-Souqi, Exploiting the internal resonance in shunted-circuit based vibration suppression, MS Thesis, American University of Sharjah, Sharjah, UAE, 2024.

- N. Hagood, W. Chung, A. von Flotow, Modeling of piezoelectric actuator dynamics for active structural control, J. of Int. Mat. Sys. and Str., vol. 1, pp. 327–354, 1990.

- Thomas, J. F. Deü, and J. Ducarne, “Vibrations of an elastic structure with shunted piezoelectric patches: efficient finite element formulation and electromechanical coupling coefficients,” Int. J. for N. M. in Eng, vol. 80 (2), pp. 235-268, 2009.

- J. Fleming, S. Behrens and S. Moheimani, "Reducing the inductance requirements of piezoelectric shunt damping systems," Smart Mater. Struct., vol. 12, (1), pp. 57, 2003.

- H.N. Arafat, A.H. Nayfeh and C.M. Chin, '"Nonlinear nonplanar dynamics of parametrically excited cantilever beams," Nonlinear dynamics, vol. 15, no. 1, Jan 1, pp. 31–61.

- K. Kadri, Nonlinear multimode vibration attenuation using passive shunt circuits, MS Thesis, American University of Sharjah, Sharjah, UAE, 2024.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).