Submitted:

05 May 2025

Posted:

06 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

2.2. Population Characteristics and Recruitment

2.3. Metabolomics Experiments

2.3.1. Sample Harvesting and Processing

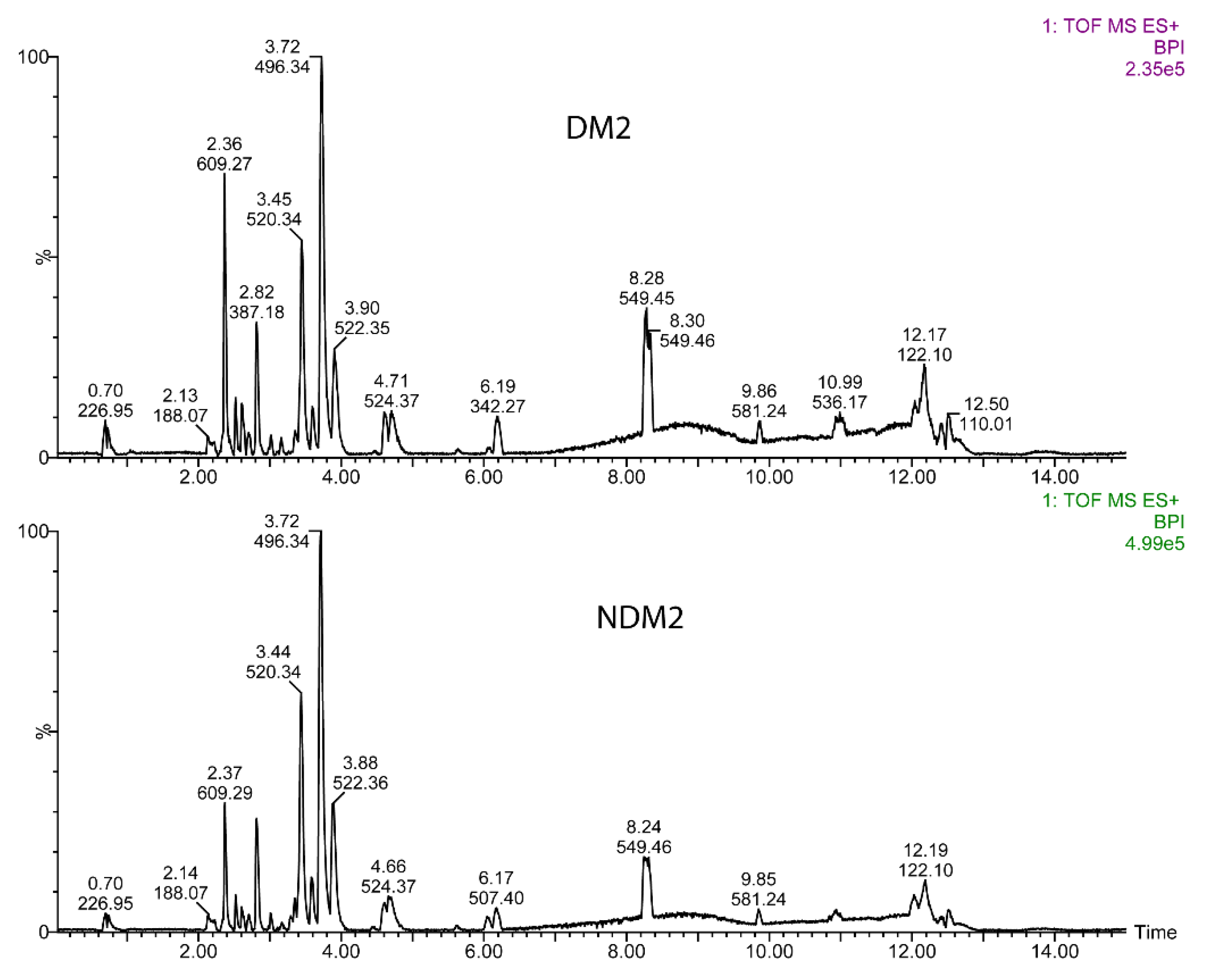

2.3.2. UPLC-MS Measurements

2.3.3. UPLC-MS Data Analysis

2.3.4. Classical Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Evaluation of the Cohort Characteristics

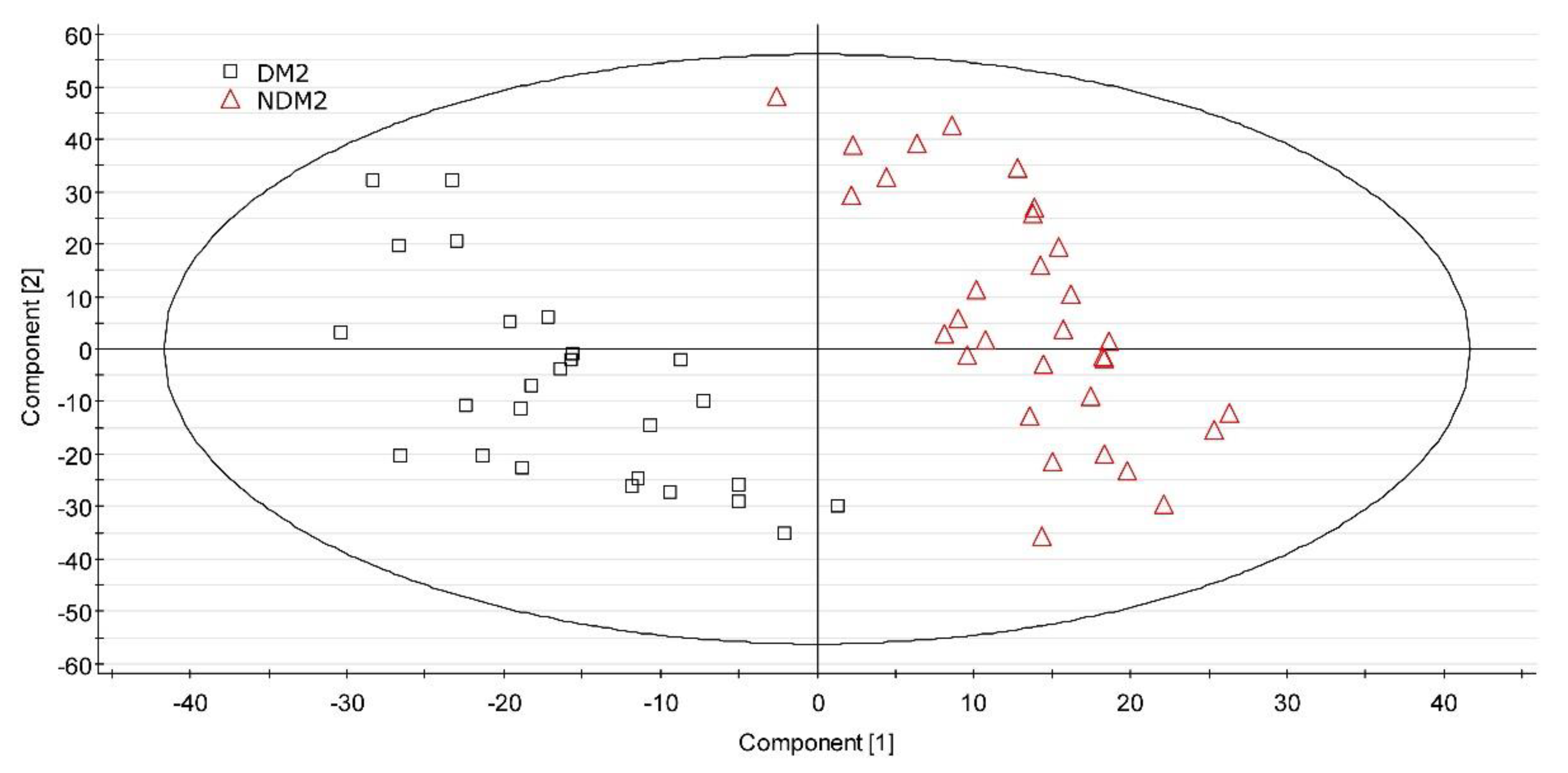

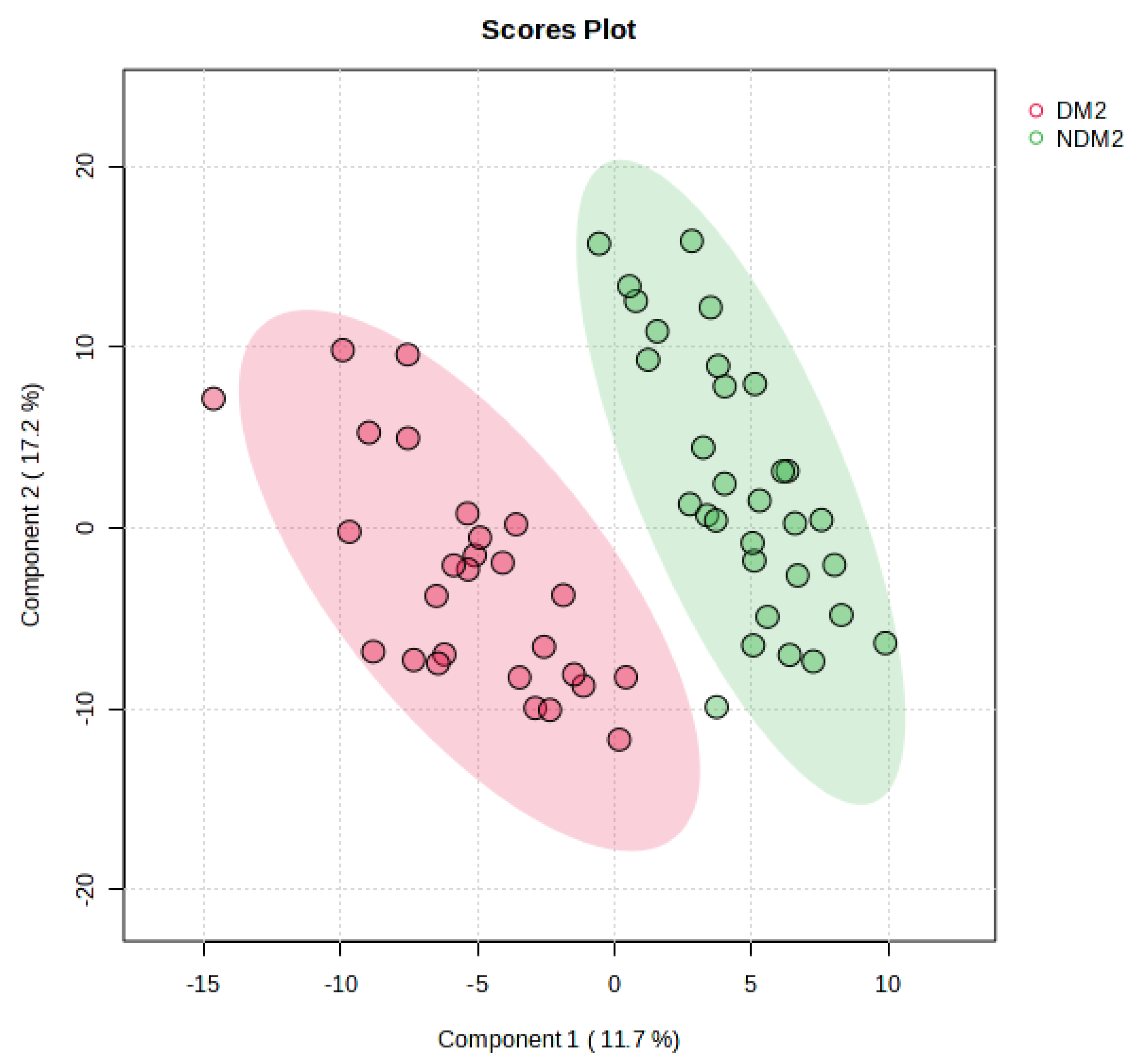

3.2. UPLC-MS Data Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UPLC | Ultra-high Pressure Liquid Chromatography |

| MS | Mass Spectrometry |

| QToF | Quadrupole Time of Fligh |

| XS | Extended Statistics |

| MEDAS-14 | Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener-14 ítems |

| LPC | Lysophosphatidylcholine |

| DM2 | Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| BCAAs | Branched-Chain Amino Acids |

| AAAs | Aromatic Amino Acids |

| IR | Insulin Resistance |

| NDM2 | Non-Diabetic Metabolic Syndrome |

| PC | Phosphatidylcholine |

| PPARγ | Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma |

| TLR4 | Toll-Like Receptor 4 |

| CE | Cholesteryl Ester |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

References

- Johannsen, D.L.; Conley, K.E.; Bajpeyi, S.; Punyanitya, M.; Gallagher, D.; Zhang, Z.; Covington, J.; Smith, S.R.; Ravussin, E. Ectopic Lipid Accumulation and Reduced Glucose Tolerance in Elderly Adults Are Accompanied by Altered Skeletal Muscle Mitochondrial Activity. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2012, 97, 242–250. [CrossRef]

- Guasch-Ferré, M.; Hruby, A.; Toledo, E.; Clish, C.B.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Hu, F.B. Metabolomics in Prediabetes and Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Diabetes Care 2016, 39, 833–846. [CrossRef]

- Arneth, B.; Arneth, R.; Shams, M. Metabolomics of Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes. IJMS 2019, 20, 2467. [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, M.N.; Green, J.A.; Cnop, M.; Igoillo-Esteve, M. tRNA Biology in the Pathogenesis of Diabetes: Role of Genetic and Environmental Factors. IJMS 2021, 22, 496. [CrossRef]

- Ferdous, S.-E.; Ferrell, J.M. Pathophysiological Relationship between Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease: Novel Therapeutic Approaches. IJMS 2024, 25, 8731. [CrossRef]

- Pallares-Méndez, R.; Aguilar-Salinas, C.A.; Cruz-Bautista, I.; Del Bosque-Plata, L. Metabolomics in Diabetes, a Review. Annals of Medicine 2016, 48, 89–102. [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.J.; Larson, M.G.; Vasan, R.S.; Cheng, S.; Rhee, E.P.; McCabe, E.; Lewis, G.D.; Fox, C.S.; Jacques, P.F.; Fernandez, C.; et al. Metabolite Profiles and the Risk of Developing Diabetes. Nat Med 2011, 17, 448–453. [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Tavintharan, S.; Sum, C.F.; Woon, K.; Lim, S.C.; Ong, C.N. Metabolic Signature Shift in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Revealed by Mass Spectrometry-Based Metabolomics. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2013, 98, E1060–E1065. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, L.D.; Koulman, A.; Griffin, J.L. Towards Metabolic Biomarkers of Insulin Resistance and Type 2 Diabetes: Progress from the Metabolome. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology 2014, 2, 65–75. [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; He, B.; Xia, J.; Wang, Z. Untargeted and Targeted Lipidomics Unveil Dynamic Lipid Metabolism Alterations in Type 2 Diabetes. Metabolites 2024, 14, 610. [CrossRef]

- Lynch, C.J.; Adams, S.H. Branched-Chain Amino Acids in Metabolic Signalling and Insulin Resistance. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2014, 10, 723–736. [CrossRef]

- Han, H.-S.; Ahn, E.; Park, E.S.; Huh, T.; Choi, S.; Kwon, Y.; Choi, B.H.; Lee, J.; Choi, Y.H.; Jeong, Y.L.; et al. Impaired BCAA Catabolism in Adipose Tissues Promotes Age-Associated Metabolic Derangement. Nat Aging 2023, 3, 982–1000. [CrossRef]

- Choi, B.H.; Hyun, S.; Koo, S.-H. The Role of BCAA Metabolism in Metabolic Health and Disease. Exp Mol Med 2024, 56, 1552–1559. [CrossRef]

- Shahisavandi, M.; Wang, K.; Ghanbari, M.; Ahmadizar, F. Exploring Metabolomic Patterns in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Response to Glucose-Lowering Medications—Review. Genes 2023, 14, 1464. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.; Samson, S.L.; Reddy, V.T.; Gonzalez, E.V.; Sekhar, R.V. Impaired Mitochondrial Fatty Acid Oxidation and Insulin Resistance in Aging: Novel Protective Role of Glutathione. Aging Cell 2013, 12, 415–425. [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Al Dubayee, M.; Alshahrani, A.; Masood, A.; Benabdelkamel, H.; Zahra, M.; Li, L.; Abdel Rahman, A.M.; Aljada, A. Distinctive Metabolomics Patterns Associated With Insulin Resistance and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2020, 7, 609806. [CrossRef]

- Cortés Tormo, M.; Marcos Tomás, J.V.; Giner Galvañ, V.; Redón I Mas, J. Metabolomics as a tool towards personalized medicine in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Rev Med Lab 2021. [CrossRef]

- Albillos, S.M.; Montero, O.; Calvo, S.; Solano-Vila, B.; Trejo, J.M.; Cubo, E. Plasma Acyl-Carnitines, Bilirubin, Tyramine and Tetrahydro-21-Deoxycortisol in Parkinson’s Disease and Essential Tremor. A Case Control Biomarker Study. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders 2021, 91, 167–172. [CrossRef]

- Vaughan D, W.H. Dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation.

- Sjoberg, D., D.; Whiting, K.; Curry, M.; Lavery, J., A.; Larmarange, J. Reproducible Summary Tables with the Gtsummary Package. The R Journal 2021, 13, 570. [CrossRef]

- Ahola-Olli, A.V.; Mustelin, L.; Kalimeri, M.; Kettunen, J.; Jokelainen, J.; Auvinen, J.; Puukka, K.; Havulinna, A.S.; Lehtimäki, T.; Kähönen, M.; et al. Circulating Metabolites and the Risk of Type 2 Diabetes: A Prospective Study of 11,896 Young Adults from Four Finnish Cohorts. Diabetologia 2019, 62, 2298–2309. [CrossRef]

- Kimura, K.; Nakamura, Y.; Inaba, Y.; Matsumoto, M.; Kido, Y.; Asahara, S.; Matsuda, T.; Watanabe, H.; Maeda, A.; Inagaki, F.; et al. Histidine Augments the Suppression of Hepatic Glucose Production by Central Insulin Action. Diabetes 2013, 62, 2266–2277. [CrossRef]

- DiNicolantonio, J.J.; McCarty, M.F.; OKeefe, J.H. Role of Dietary Histidine in the Prevention of Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome. Open Heart 2018, 5, e000676. [CrossRef]

- Gall, W.E.; Beebe, K.; Lawton, K.A.; Adam, K.-P.; Mitchell, M.W.; Nakhle, P.J.; Ryals, J.A.; Milburn, M.V.; Nannipieri, M.; Camastra, S.; et al. α-Hydroxybutyrate Is an Early Biomarker of Insulin Resistance and Glucose Intolerance in a Nondiabetic Population. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e10883. [CrossRef]

- Floegel, A.; Stefan, N.; Yu, Z.; Mühlenbruch, K.; Drogan, D.; Joost, H.-G.; Fritsche, A.; Häring, H.-U.; Hrabě De Angelis, M.; Peters, A.; et al. Identification of Serum Metabolites Associated With Risk of Type 2 Diabetes Using a Targeted Metabolomic Approach. Diabetes 2013, 62, 639–648. [CrossRef]

- Ferrannini, E.; Natali, A.; Camastra, S.; Nannipieri, M.; Mari, A.; Adam, K.-P.; Milburn, M.V.; Kastenmüller, G.; Adamski, J.; Tuomi, T.; et al. Early Metabolic Markers of the Development of Dysglycemia and Type 2 Diabetes and Their Physiological Significance. Diabetes 2013, 62, 1730–1737. [CrossRef]

- Wittenbecher, C.; Mühlenbruch, K.; Kröger, J.; Jacobs, S.; Kuxhaus, O.; Floegel, A.; Fritsche, A.; Pischon, T.; Prehn, C.; Adamski, J.; et al. Amino Acids, Lipid Metabolites, and Ferritin as Potential Mediators Linking Red Meat Consumption to Type 2 Diabetes. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2015, 101, 1241–1250. [CrossRef]

- Drabkova, P.; Sanderova, J.; Kovarik, J.; Kandar, R. An Assay of Selected Serum Amino Acids in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Adv Clin Exp Med 2015, 24, 447–451. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wu, Z.; Dai, Z.; Yang, Y.; Wang, J.; Wu, G. Glycine Metabolism in Animals and Humans: Implications for Nutrition and Health. Amino Acids 2013, 45, 463–477. [CrossRef]

- Ha, C.Y.; Kim, J.Y.; Paik, J.K.; Kim, O.Y.; Paik, Y.; Lee, E.J.; Lee, J.H. The Association of Specific Metabolites of Lipid Metabolism with Markers of Oxidative Stress, Inflammation and Arterial Stiffness in Men with Newly Diagnosed Type 2 Diabetes. Clinical Endocrinology 2012, 76, 674–682. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, G.F.; Carpentier, A.; Adeli, K.; Giacca, A. Disordered Fat Storage and Mobilization in the Pathogenesis of Insulin Resistance and Type 2 Diabetes. Endocrine Reviews 2002, 23, 201–229. [CrossRef]

- Wang-Sattler, R.; Yu, Z.; Herder, C.; Messias, A.C.; Floegel, A.; He, Y.; Heim, K.; Campillos, M.; Holzapfel, C.; Thorand, B.; et al. Novel Biomarkers for Pre-diabetes Identified by Metabolomics. Molecular Systems Biology 2012, 8, 615. [CrossRef]

- Mirza, A.Z.; Althagafi, I.I.; Shamshad, H. Role of PPAR Receptor in Different Diseases and Their Ligands: Physiological Importance and Clinical Implications. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2019, 166, 502–513. [CrossRef]

- Donath, M.Y.; Shoelson, S.E. Type 2 Diabetes as an Inflammatory Disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2011, 11, 98–107. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wu, L.; Chen, J.; Dong, L.; Chen, C.; Wen, Z.; Hu, J.; Fleming, I.; Wang, D.W. Metabolism Pathways of Arachidonic Acids: Mechanisms and Potential Therapeutic Targets. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2021, 6, 94. [CrossRef]

- Ellulu, M.S.; Samouda, H. Clinical and Biological Risk Factors Associated with Inflammation in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. BMC Endocr Disord 2022, 22, 16. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Sun, J.; Zhang, W.; Guo, Z.; Ma, Q. Arachidonic Acid Metabolism in Health and Disease. MedComm 2023, 4, e363. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhang, W.; Cai, Y.; Shan, P.; Wu, D.; Zhang, B.; Liu, H.; Khan, Z.A.; Liang, G. Arachidonic Acid Inhibits Inflammatory Responses by Binding to Myeloid Differentiation Factor-2 (MD2) and Preventing MD2/Toll-like Receptor 4 Signaling Activation. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease 2020, 1866, 165683. [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Subramanian, V.S.; Subbaiah, P.V. Modulation of the Positional Specificity of Lecithin−Cholesterol Acyltransferase by the Acyl Group Composition of Its Phosphatidylcholine Substrate: Role of the Sn -1-Acyl Group. Biochemistry 1998, 37, 13626–13633. [CrossRef]

- Nakhjavani, M.; Morteza, A.; Karimi, R.; Banihashmi, Z.; Esteghamati, A. Diabetes Induces Gender Gap on LCAT Levels and Activity. Life Sciences 2013, 92, 51–54. [CrossRef]

- Bandet, C.L.; Mahfouz, R.; Véret, J.; Sotiropoulos, A.; Poirier, M.; Giussani, P.; Campana, M.; Philippe, E.; Blachnio-Zabielska, A.; Ballaire, R.; et al. Ceramide Transporter CERT Is Involved in Muscle Insulin Signaling Defects Under Lipotoxic Conditions. Diabetes 2018, 67, 1258–1271. [CrossRef]

- Sandhoff, R.; Schulze, H.; Sandhoff, K. Ganglioside Metabolism in Health and Disease. In Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science; Elsevier, 2018; Vol. 156, pp. 1–62 ISBN 978-0-12-812341-6.

- Xia, Q.-S.; Lu, F.-E.; Wu, F.; Huang, Z.-Y.; Dong, H.; Xu, L.-J.; Gong, J. New Role for Ceramide in Hypoxia and Insulin Resistance. WJG 2020, 26, 2177–2186. [CrossRef]

| Variable | NDM2 Group (n=32) | DM2 Group (n=27) |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics and anthropometric characteristics | ||

| Age (years; p = 0.004) | 71.4 ± 9.0 | 75.9 ± 8.1 |

| Sex (Female/Male) | 21 (66%) / 11 (34%) | 15 (56%) / 12 (44%) |

| BMI (kg/m2)1 | 28.8 ± 5.8 | 28.5 ± 6.3 |

| Underweight | 4 (13%) | 3 (11%) |

| Normal | 7 (22%) | 9 (33%) |

| Overweight | 7 (22%) | 6 (22%) |

| Obese | 14 (44%) | 9 (33%) |

| Waist circumference-Female (cm)2 | 100.6 ± 16.0 (n = 21) | 100.6 ± 14.9 (n = 15) |

| Waist circumference-Male (cm)2 | 104.8 ± 10.4 (n = 11) | 108.9 ± 11.4 (n = 12) |

| Lifestyle and dietary habits | ||

| Alcohol intake3 (p = 0.049) | 15 (47%) | 6 (22%) |

| Smoking status | ||

| Never smoker | 22 (69%) | 20 (74%) |

| Former smoker | 6 (19%) | 5 (19%) |

| Current smoker | 4 (13%) | 2 (7.4%) |

| Physical activity (MET-h/week)4 | 77.1 ± 93.8 | 64.9 ± 67.0 |

| Vigorous-intensity | 16 (50%) | 14 (52%) |

| Moderate | 10 (31%) | 7 (26%) |

| Light | 2 (6.3%) | 2 (7.4%) |

| Rest-being | 4 (13%) | 4 (15%) |

| Mediterranean diet score (MEDAS-14)5 | 8.6 ± 1.5 | 7.9 ± 1.1 |

| Low adherence | 7 (22%) | 8 (30%) |

| Moderate adherence | 19 (59%) | 18 (67%) |

| Strong adherence | 6 (19%) | 1 (3.7%) |

| High sugar food intake6 (p = 0.013) | 21 (66%) | 9 (33%) |

| Sugar intake (g/day: p = 0.019) | 47.3 ± 83.7 | 26.7 ± 55.5 |

| High fat food intake7 | 13 (41%) | 8 (30%) |

| Meat intake type | ||

| No meat diet | 5 (16%) | 6 (22%) |

| White and processed meat | 8 (25%) | 7 (26%) |

| Red and processed meat | 8 (25%) | 11 (41%) |

| White meat | 11 (34%) | 3 (11%) |

| Family history, treatments, polypharmacy, blood pressure, and biochemical parameters | ||

| Family history of cardiovascular disease | 15 (47%) | 7 (26%) |

| Family history of endocrine disease (p < 0.001) | 8 (25%) | 19 (70%) |

| Treatment for dyslipidemia | 11 (34%) | 12 (44%) |

| Polypharmacy (> 3 medications, p < 0.001) | 12 (38%) | 24 (89%) |

| Systolic blood pressure left arm (mmHg) (p = 0.038) | 134.6 ± 19.4 | 138.4 ± 15.2 |

| Diastolic blood pressure right arm (mmHg) | 83.1 ± 9.0 | 79.1 ± 8.5 |

| HbA1c (%) | - | 6.9 ± 0.9 |

| Fasting glucose (mmol/L, p < 0.001) | 5.1 ± 0.6 | 7.2 ± 1.9 |

| Total serum cholesterol (mg/dL, p < 0.001) | 193.0 ± 28.8 | 164.2 ± 36.3 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 61.8 ± 16.2 | 61.6 ± 32.9 |

| LDL (mg/dL, p < 0.001) | 109.0 ± 24.2 | 86.4 ± 29.5 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 102.4 ± 37.3 | 105.4 ± 43.0 |

| TG/HDL ratio | 1.8 ± 1.0 | 2.0 ± 1.1 |

| LDL/HDL cholesterol ratio | 1.7 ± 0.6 | 1.6 ± 0.7 |

| High cardiovascular risk | 13 (41%) | 11 (41%) |

| Metabolite | Formula [M + H]+ |

m/z | Normalized Chromatographic Peak Areas | Retention Time (min) |

FC (Log2) |

Regulation | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DM2 | NDM2 | |||||||

| LPC(14:0) | C22H47NO7P | 468.3072 | 0.032 ± 0.016 | 0.053 ± 0.029 | 3.18 | - 0.73 | Down | <0.001 |

| LPC(16:0) | C24H50NO7P | 496.3413 | 3.321 ± 0.982 | 4.075 ± 0.984 | 3.72 | - 0.29 | Down | 0.003 |

| LPC(18:0) | C26H54NO7P | 525.3698 | 0.235 ± 0.067 | 0.332 ± 0.109 | 4.68 | - 0.50 | Down | <0.001 |

| LPC(18:1) | C26H52N89P | 522.3556 | 1.253 ± 0.502 | 1.306 ± 0.494 | 3.90 | - 0.06 | Down | 0.344 |

| LPC(18:2) | C26H50NO7P | 520.3401 | 1.834 ± 0.794 | 2.320 ± 1.027 | 3.45 | - 0.34 | Down | 0.023 |

| LPC(20:4) | C28H50NO7P | 544.3397 | 0.323 ± 0.139 | 0.313 ± 0.159 | 3.42 | + 0.05 | Up | 0.400 |

| LPC(22:6) | C30H50NO7P | 569.3391 | 0.077 ± 0.038 | 0.083 ± 0.040 | 3.36 | - 0.10 | Down | 0.296 |

| PC(16:0/18:2) | C42H80NO8P | 758.5605 | 2.29 10-4 ± 6.55 10-4 | 6.22 10-4 ± 12.6 10-4 | 7.54 | - 1.44 | Down | 0.081 |

| Ganglioside 1 | C75H137N3O27 | 754.9894 | 0.074 ± 0.041 | 0.096 ± 0.045 | 3.72 | - 0.37 | Down | 0.032 |

| Ganglioside 2 | C75H135N3O27 | 762.9800 | 0.013 ± 0.010 | 0.019 ± 0.009 | 3.72 | - 0.57 | Down | 0.009 |

| Ganglioside 3 | C78H142N2O31 | 791.4910 | 0.017 ± 0.014 | 0.024 ± 0.022 | 3.44 | - 0.52 | Down | 0.080 |

| Glycine-Histidine | C8H12N4O3 | 195.0888 | 0.008 ± 0.013 | 0.021 ± 0.035 | 2.18 | - 1.43 | Down | 0.040 |

| Unidentified 1 | C26H47N2O7P? | 531.8243 | 0.100 ± 0.056 | 0.133 ± 0.064 | 3.44 | - 0.41 | Down | 0.020 |

| Gly-His | LPC(22:6) | LPC(20:4) | LPC(14:0) | Ganglioside 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gly-His | - | - 0.211 (0.113) | - 0.057 (0.669) | 0.366 (0.005) | 0.006 (0.963) |

| LPC(22:6) | - 0.211 (0.113) | - | 0.513 (<0.001) | 0.250 (0.059) | 0.540 (<0.001) |

| LPC(20:4) | - 0.057 (0.669) | 0.513 (<0.001) | - | 0.190 (0.153) | 0.333 (0.011) |

| LPC(14:0) | 0.366 (0.005) | 0.250 (0.059) | 0.190 (0.153) | - | 0.480 (<0.001) |

| Ganglioside 2 | 0.006 (0.963) | 0.540 (<0.001) | 0.333 (0.011) | 0.480 (<0.001) | - |

| Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | n | OR | 95% CI2 | p-Value | OR | 95% CI | p-Value | |

| Age | 59 | 1.064 | 1.000-1.140 | 0.060 | 1.096 | 1.009-1.208 | 0.041 | |

| Gender masculine | 59 | 1.527 | 0.533-4.441 | 0.430 | 1.413 | 0.281-7.305 | 0.670 | |

| Gly-Hist | Gender | 59 | 0.994 | 0.985-1.000 | 0.108 | 0.995 | 0.985-1.003 | 0.349 |

| No gender | 59 | 0.994 | 0.986-1.000 | 0.108 | 0.996 | 0.986-1.003 | 0.336 | |

| LPC(22:6) | Gender | 59 | 1.000 | 0.997-1.003 | 0.624 | 1.001 | 0.995-1.008 | 0.652 |

| No gender | 59 | 1.001 | 0.998-1.004 | 0.624 | 1.001 | 0.995-1.008 | 0.740 | |

| LPC(20:4) | Gender | 59 | 1.000 | 0.999-1.001 | 0.100 | 1.001 | 1.000-1.003 | 0.049 |

| No gender | 59 | 1.001 | 0.999-1.002 | 0.100 | 1.002 | 1.001-1.004 | 0.026 | |

| LPC(14:0) | Gender | 59 | 0.990 | 0.982-0.996 | 0.009 | 0.988 | 0.977-0.997 | 0.018 |

| No gender | 59 | 0.991 | 0.983-0.997 | 0.009 | 0.989 | 0.978-0.997 | 0.019 | |

| Ganglioside 2 | Gender | 59 | 0.986 | 0.971-0.998 | 0.044 | 0.976 | 0.950-0.996 | 0.042 |

| No gender | 59 | 0.986 | 0.971-0.999 | 0.044 | 0.977 | 0.952-0.997 | 0.045 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).