Introduction

1.1 Background to the Study

Social Studies impart the knowledge, skills, and attitudes needed to exhibit the national spirit of being in learners. Invariably, it is an integrated subject with its origin, not directly from Nigeria; it was adopted from other countries. It can be traced to countries such as the United States of America and Great Britain. According to Drake and Reid (2018), an integrated subject implies a form of character education, financial literacy, critical literacy, and environmental awareness mandated in the subject-based curriculum. However, the integrated curriculum features a common theme in different subject areas, yet it is distinct in its approach. For example, the theme of “identity” could be explored in geography (mapping), history (nationality), literature (characterisation), and science (classification). Social Studies as an integrated subject includes other subjects such as Law, Philosophy, Political Science, Psychology, Religion, Sociology, Economics, Anthropology, and Archaeology. Adedoja and Abimbade (2016) opined that Social Studies are concerned with the realities of human existence on earth and asserted that students are expected to learn about humankind, such as social, political, economic, religious, and artistic behaviour. Penner (2019) sees these multiple perspectives in the Social Studies discipline differently by asserting that while the value of Social Studies in promoting citizenship, literacy, and critical thinking skills is often stated, Social Studies fade in importance when compared to many other subjects.

Research has shown that the main purpose of social studies was for ‘National Integration’ and wiping out memories of the civil war. In Nigeria, Okoro (2019) revealed that Social Studies was introduced into the school curriculum to inculcate national consciousness, unity in diversity, and national tolerance and respect for others. He further argued that Nigeria also used Social Studies as an instrument for social transformation to address national issues and moral decadence in society. The National Policy on Education (FRN, 2013) in agreement with this assertion, stated that education should develop an individual into a morally sound, patriotic and effective citizen. Pryor, Pryor, and Kang (2016) assert that Social Studies is to help young people develop the ability to make informed and reasonable decisions for the public good, as citizens of a culturally diverse, democratic society in an interdependent world. This can be achieved through educational activities that are centred on maximum development and self-fulfilment. Li (2016) revealed positive outcomes when he employed a learner-centred approach, such that independent learning in the web environment encouraged students to have self-paced learning which allowed them to focus better, understand better, and be motivated because they could plan their own learning process. Penner (2019) revealed that the goals and end products of Social Studies are to prepare learners to be well-informed citizens. While Pryor, Pryor, and Kang (2016) described Social Studies as teaching students today how to be productive members of a democratic society, they further revealed that Social Studies has had the educational mission of preparing the nation’s next generation to participate in a democratic society.

Social Studies has since been recognised as a major subject in elementary and middle schools in Osun State. Recently, the discipline has evolved into other subjects studied in Nigeria, such as Civic Education at the senior secondary school level, while Social Studies retained its relevance to the needs and aspirations of societal sanity in the early years of learning at elementary levels and middle secondary schools in Osun State. Goals involve developing individual learners in knowledge, skills, and attitude, as stated above, as a fundamental basis of what education is to present to every learner within the four walls of a school and beyond.

Okoro (2019) opined that the effectiveness and efficiency of the teaching-learning process are very much dependent on the teaching strategies used by instructors. Social Studies and what constitutes it as an area of enquiry are complex and difficult to define (Case and Abbott, 2013). The Social Studies discipline is then said to be defaced with an unresolved problem, such as failure in terms of the purpose of its incorporation into the Nigerian school curriculum. It is unscholarly to rely on personal experiences; rather, it is necessary to do so critically (Smith, 2013). The unachieved purpose of Social Studies may be as a result of teaching strategies or methodology which most Social Studies learners refer to as being “boring” or they lack interest for reasons best known to them. Based on the reflection on learners’ attitude to Social Studies subject matter Smith (2014) referred to such unresolved as the self-imposed epistemological demand to reshape student conceptions of Social Studies “text”. Given the conceptual depth and brightness of definitions for the field itself, it seemed to take on greater levels of import and frustration.

According to Ajani (2018), teachers cannot rely only on the entry knowledge they begin their teaching careers. This implies that learning strategies must be constantly improved. Abbah, Umar and Hussain (2018) cited Mezieobi and Joof, attributing the poor performance to the use of inappropriate strategies by the instructor in teaching and learning activities. In this regard,Adedoja and Abimbade(2016) stressed that in Sub-Sahara Africa, learning strategies are mainly characterised by traditional teaching methods, where teachers are seen as the “know all and be all’. Furthermore,Abimbade, Akinyemi, and Bello (__) opined that traditional teaching strategies are teacher-centred and characterised by direct instruction. Iwuamadi (2013) emphasised using an appropriate method of teaching to foster learning. It is generally believed that learners are fascinated by technological tools, and they learn much faster and better when digital media are used or integrated into the teaching-learning processes because they can hear and see what is being taught on the screens.

The researcher’s aim is not to argue on the existing conceptual framework, value, importance, methodology, and techniques used to disseminate Social Studies concepts in the classroom, but rather to develop a viable method for students to learn the subject effectively while improving their attitude and achievement via technological integration in classroom settings. Sofadekan (2012) agreed that when techniques are appropriately used by specialists in the Social Studies field to a point where they give meaning to teaching, the teaching technique can determine the extent of achievement or otherwise of the instructional objectives. These methods and techniques include presentation, creative activities, discussion, dramatisation, and problem-solving methods. Each method embodies various techniques, such as lecturing, storytelling, drawing, brainstorming, role-play, and field trips. Thus, innovative instructional strategies, regardless of their use, should focus more on mastery and pair-to-pair learning strategies (Animola and Bello, 2019). Okoyefi and Nzewi (2013) showed that the right learning strategies should be able to arouse learners’ interest in Social Studies education.

Therefore, this study investigates the effect of a think-pair-share collaborative digital storytelling instructional strategy and a centralised video-based digital storytelling instructional strategy. Learning is achieved through the development process and has specified patterns. Education is a widespread occurrence in organised societies, and it states that teachers seek to solve problems through various learning techniques, both human and non-human resources. Social Studies education has faced many challenges in the past and even in today’s educational system. Prominent among these numerous challenges are the teaching and learning strategies used by teachers to aid learning processes in Social Studies classrooms.

This study adopts the use of digital storytelling which connotes storytelling through technological media. Teaching involves storytelling. What then is the storytelling? Kratka, (2015) is of the view that storytelling contains a reflection of our perception of the experience of a body of knowledge while Animola and Bello (2019), revealed that teachers telling stories reflect teaching strategies known as expository, explanatory, lecture method, field trip method etc. Storytelling informs the narrative of an event or happenstance that informs learning within the classroom or outdoor events, methods, or strategies that the instructor tends to adopt in the course of teaching. The National Storytelling Network (2011) highlights storytelling as the art of using language, vocalisation, and/or physical movement and gestures to reveal the elements and images of a story. Digital storytelling which deals with the use of digital media to tell stories, with media elements such as graphical images, videos, sounds, and animations, organised together by leveraging educational tools (such as Camtasia, PowerPoint, and Movie Maker) and implemented through various channels, such as projectors, televisions, radio, smart mobile devices, blogs/websites, print media, laptops, and desktop computers. This could be a solution to some of the problems encountered in teaching and learning Social Studies. Rubin (2016) further revealed that multimedia elements are brought together with the use of digital software, to narrate stories that focus on a specific theme or topic and tone of the message.

Hence, digital stories are most likely found to be relatively short in length, ranging between 2 and 10 minutes, and processed in a digital format that can be accessed on a desktop computer, laptop, or smart device capable of playing video files. The pedagogical benefits of digital storytelling, suggesting that digital media can provide the forum and space for students to reflect in a presentational form and in this, more efficiently address changes in self-perception and/or attitude (Perry, Stoner, Schleser, Stoner, Wadsworth, Tarrant, 2015 and Hamilton, Rubin, Tarrant, Mikkel 2019). Over the years, Digital storytelling has gained recognition among researchers and educational practitioners and is currently practiced in various places, including schools, libraries, community centres, museums, businesses, and medical and nursing schools. The major teaching strategies associated with activity methods are discussion, simulation, and collaborative learning strategies, among others (Okoro, 2019).

Collaborative learning strategies have existed for a long time. Some scholars have addressed the discourse as cooperative (Kreijns, Kirschner, & Jochems, 2003; Roberts, 2004; Sung, Yang, & Lee, 2017), while scholars such as Dillenbourg (1999) and Slavin (1997) tried to differentiate conceptually narrative and collaborative learning, according to Adedoja and Olasunkanmi (2015), encompassed educational approaches that promote joint efforts among learner-learners and learners-teachers interaction in a learning process. Van Leeuwen, and Janssen (2019) opined that when collaborative concepts and cooperative concepts are interchanged, it is often based on theidea that cooperative learning involves division of labour, while collaborative learning is seen as the mutual engagement of participants. This study is in agreement with Van Leeuwen and Janssen, who conceptualised the terms collaborative learning and cooperative learning to be used interchangeably for the sake of simplicity and clarity. Think-pair-share (TPS) is a learning strategy of several techniques from Cooperative Learning (Sutrisno et al., 2019).They further revealed that TPS was designed and developed by Lyman and associated with other collaborative strategies to encourage classroom participation among learners. TPS collaborative digital storytelling instructional strategy can be considered a pedagogical model based on a small workgroup and student interaction where students build their own learning, searching for a common objective (Johnson and Johnson in Saborit, Fernández-Río, Estrada, Méndez-Giménez, and Alonso, 2016). Fatimah (2015) believes that cooperative learning think-pair-share is an easy method to implement during learning. Despite being a teaching practice that began in the 1980s, it is considered to be one of the most innovative approaches in the current educational landscape (Surian and Damini, 2014). David and Johnson quoted by Sutrisno et al (2019), revealed that this strategy involves a collaborative model with three steps. In the first step, the individual learner is given the opportunity to “think” about questions posed by the instructor. In the second step, learners are paired into groups and exchange perspectives. Step three, each group member (learner) shares insights with other group members and other groups during the course of inter-group discussion when needed. Learners come together to work towards a common goal which is to bring about permanent changes in their behaviour by exchanging and sharing ideas, information, knowledge, resources, tools, products, and results. The TPS collaborative digital storytelling instructional learning strategy contradicts a centralised video-based digital storytelling instructional strategy. Centralised video-based instructional strategies inform a type of video-based learning where the teacher in a conventional teaching strategy relies on digital stories in video format as an instructional teaching aid related to the focused topic being treated in class. Videos have over the years been regarded as the main means by which content creation is created, produced and implemented for the “millennials and iGeneration” (iGeneration implies birth between 1995 and 2007, meaning that as of 2016 they were between ages 9 and 21 years) (Mitrovic, Dimitrova, Lau, Weerasinghe and Mathews 2017).

Centralised video-based digital storytelling allows students to brainstorm, pay attention, observe and interpret a script, and develop an interesting story from their own perspective and understanding. While taking a centralised video-based storytelling class, different technological tools and programs, such as podcasts, infographics, and other types of presentations, make it easy for instructors to create digital stories for a better understanding of students, which could be used as teasers to amplify their curiosity about a topic or idea or to link prior knowledge to new knowledge. Schroeder (2014) found that video-based learning has been implemented in a wide spectrum of instructional settings, including flipped classrooms. In recent learning activities, online learning has found this a valuable tool from Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCS) to informal learning using YouTube, (Kurtz, Tsimerman, Steiner-Lavi(2014), Guo, Kim Rubin (2014), and Vieira, Lopes, Soares (2014) and other digital storytelling video platforms on the internets (such as Storify, StoryBook, Historypin, Storybird, Cowbird, Animoto, ZooBurst, ComicMaster, Project, Picture Book Maker, and Stop Frame Animator) as highlighted by Ribeiro (2015).Digital storytelling has become a global phenomenon. Therefore, it can be used to enhance learners’ academic achievement in Social Studies.

Achievement of learners mostly at the elementary school level is not only a pointer to the effectiveness or otherwise of schools but is also a major determinant of the future of youths in particular and the nation in general (Dev 2016). Scholars such as Adesina (2003), Çatak, Kaya and Erol (2016), Çatak (2019) and Sel and Sözer (2019) have it that, it was the general feeling that most students felt inadequate in Social Studies subject area, the feeling of prejudice and negative judgment that may stem from either teachers, families or students themselves, and the misconception of construct which results to students complaining that Social Studies was complex and difficult to understand. The attitude exhibited by learners could then result in poor performance in the subject area, as seen in their annual results sheets. Scholars have revealed the effects of negative attitudes toward learning on the achievement of learners of all ages. Adedoja and Olasunkanmi (2015) asserted that learners’ attitudes toward any learning process remain a germane issue from age to age, even in the digital era. However, Pruet, Ang, and Farzin (2016) defined attitude as the evaluation of a specific target and behaviour of individuals in the environment, and it is also an inclination obtained after learning and a consistent behaviour due to the incurring feel and opinion after the recognition and evaluation of events and objects. The multimedia teaching approach has generally been found to have better effects on students’ learning attitude as revealed in an investigation carried out by Weng, Ho, Yang, and Weng (2019). This indicates that the digital storytelling approach to learning enhances learners’ achievement and attitudes. Scholars have pointed out that isolated learning strategies have been faulty. To support this claim that isolated teaching may be the cause, where teachers speak more of the content to the learners and do not implement the learner-centred approach, Sychterz (2015) revealed that such isolation deters student engagement and divorces them from their natural inclination to synthesise connections and develop critical thinking skills. Teachers tend to expose learners to rote memorisation, such as names, dates, and places, and implementing activities that discourage critical thinking in the classroom. The academic outcome could then be attributed to many factors, among which teaching strategies were found to be inadequate, leading to mass failure in both teachers who conducted tests and standardised examinations, among others. These factors include examination malpractice, learners’ mindset, and negative attitudes toward the subject or towards the teacher.

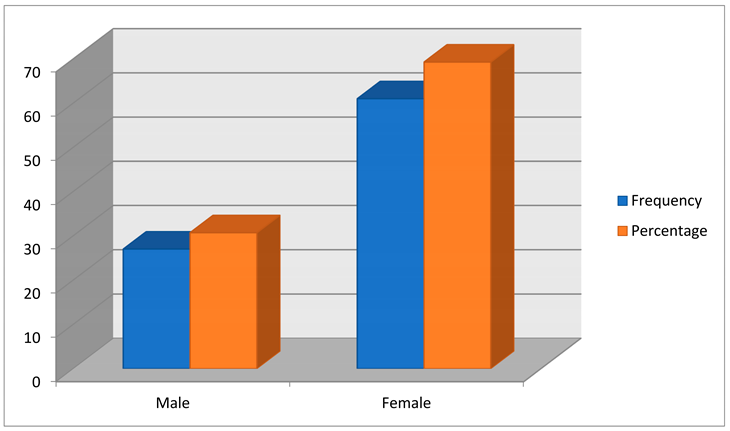

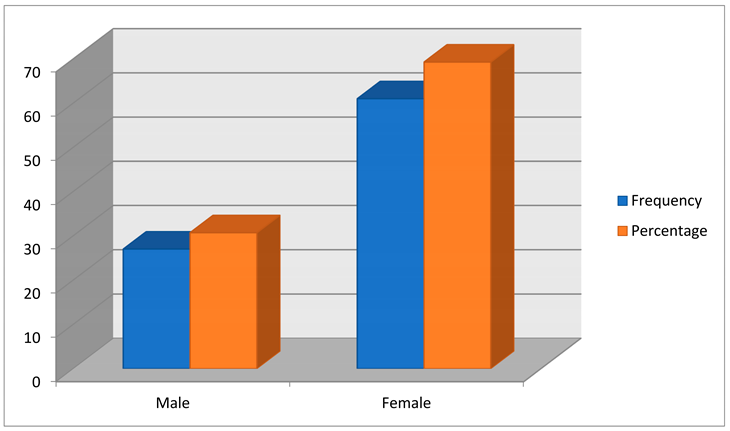

However, centralised video-based digital storytelling and think-pair-share collaborative digital storytelling instructional strategy served as the two modes of digital storytelling approach, which are invariably applicable in a wide range of settings, with all age groups and genders in diverse disciplines. Learning involves going through specific patterns that enhance the teaching process of a young child, thereby testing the significant differences in age and gender of the participants in terms of attitude and academic achievement. Blackwell et al. (2015) provided insight into a scholastic revelation that researchers have long agreed that girls have superior language abilities than boys. Until now, no one has clearly provided a biological basis that may account for these differences, even though Zoghi et al. (2013) argued that research has evidently shown that female learners usually achieve higher grades than male learners. Vanston and Strother (2016) opined that male learners tend to have a larger visual cortex than female learners. Gender is widely regarded as a significant factor, which plays a dominant role in learning, as well as influences the academic achievement of learners (Sarwar, Khan, and Manzoor, 2019).

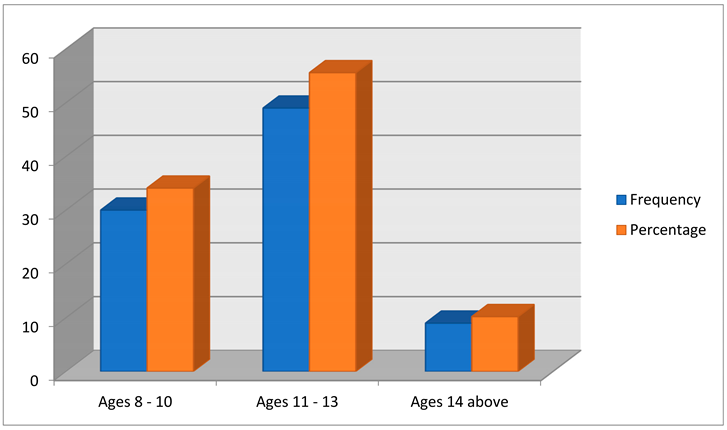

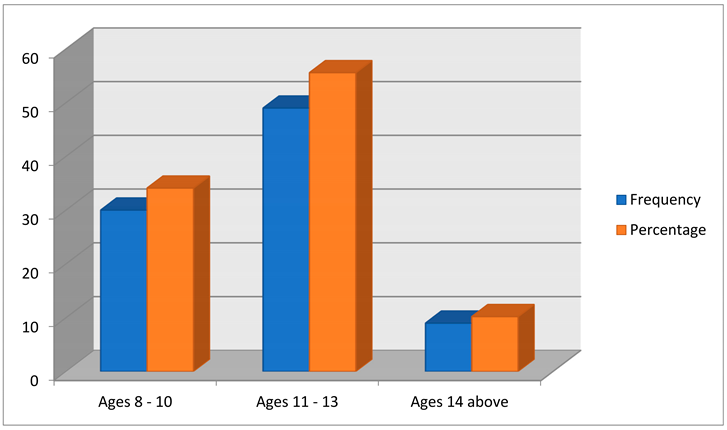

Age remains an important factor in this study because of the nature of the learners involved. One example is the belief that academic success is strongly and positively related to a student’s age at entrance to school or compared to the age of classmates (Grissom, 2004). Voyles (2011) revealed that numerous studies regarding school entrance age and student success have been published, but scholars have yet to come to agree on the extent to which learners’ age reflects their school achievement. Hence, Grissom (2011) and Voyles (2011) revealed that students who were slightly older than their peers performed better academically than their younger classmates, but students who were older because of previous retentions and other factors actually performed worse academically than their peers. Guo, Tompkins, Justice, and Petscher (2014) explained how that managing a classroom with children of different ages and meeting the diverse needs of children is a challenging task for teachers. Scholars have indicated the importance of age as a factor when the investigation is essential in early childhood and elementary learning.

Over the years, research on digital storytelling has revolved around the subject matter of students’ engagement, technological integration, reflective learning, project-based learning, and collaborative/cooperative learning, among others. Moreover, it is regarded as the core of constructivist learning strategies which form the learning theory base of the study. This research involved the selection of three government-owned schools in an L.G.A within Osogbo, State of Osun. The study critically examined the basic method of teaching which this study basically centred on, primarily looking at the effect of digital storytelling, think-pair-share collaborative strategy, centralised-video-based digital storytelling strategy, and conventional instructional teaching strategy, also known as teacher-centred. The effective academic achievement embedded in the modes as an articulated learning strategy in Social Studies and the significant effects and interaction, as opposed to conventional teaching strategies, were investigated.

1.2 Statement of the Problem

Social Studies in schools have been implemented for many years, with little success in terms of inculcating the values of good citizenship among younger children. Teachers are mostly perceived to implement learning activities that focus more on conventional teaching strategies, such as the teacher expository method categorised by dictation and note-taking, which are not very interactive. Most Social Studies learners refer to these as boring or uninteresting for reasons best known to them. The situation is worsened by the fact that some teachers may not be able to use Web 2.0 to impart knowledge. Recent studies have focused on pre-service Social Studies teachers’ training and subsequent use of a combination of tools such as WebQuests, games, internet resources, PowerPoint, Microsoft Publisher, Inspiration, Timeline, and digital/video cameras. However, all of these serve a primary function of facilitating students’ access to content and teachers’ delivery of content. Unfortunately, to a large extent, Social Studies teachers have focused on teaching strategies which are deficient in addressing the educational needs of 21st-century learners, such as the use of digital technology, tools, resources, and online learning activities. Hence, the need to examine the effect of think-pair-share collaborative digital storytelling instructional strategy and centralized video-based digital storytelling instructional strategy of pupils’ achievement and attitude towards Social Studies

1.3. Research Hypotheses

The following null hypotheses were tested at a significance level of 0.05:

Ho1: There is no significant main effect of treatment on

- i.

pupils’ achievement in Social Studies

- ii.

pupils’ attitude towards Social Studies

Ho2: There is no significant main effect of age on

- i.

pupils’ achievement in Social Studies

- ii.

pupils’ attitude towards Social Studies

Ho3: There is no significant main effect of gender on

- i.

pupils’ achievement in Social Studies

- ii.

pupils’ attitude towards Social Studies

Ho4: There is no significant interaction effect of treatment and gender on

- i.

pupils’ achievement in Social Studies

- ii.

pupils’ attitude towards Social Studies

Ho5: There is no significant interaction effect of treatment and age on

- i.

pupils’ achievement in Social Studies

- ii.

pupils’ attitude towards Social Studies

Ho6: There is no significant interaction effect of gender and age on

- i.

pupils’ achievement in Social Studies

- ii.

pupils’ attitude towards Social Studies

Ho7: There is no significant interaction effect of treatment, gender and age on

- i.

pupils’ achievement in Social Studies

- ii.

pupils’ attitude towards Social Studies

1.4 Scope of the Study

The study was restricted to three government-owned elementary schools in three districts of Osogbo, Osun State. This study focused on 4th-grade elementary school students offering Social Studies. The study covered three levels of treatment: centralised-video-based digital storytelling instructional strategy, ‘think-pair-share’ collaborative digital storytelling instructional strategy, and conventional instructional strategy. Gender and age formed the bases on which the moderating variable was mapped to examine their effect on academic achievement, considering the level of learners being investigated. The content selected for the study was drug abuse, with subthemes ranging from (i) synthetic and naturally occurring substances or drugs, (ii) nature of drug abuse, and (iii) identifying drug abusers, treatments, and rehabilitation. The concepts were drawn from the content of four primary Social Studies curricula. The pupils’ learning outcomes and attitudes toward Social Studies were articulated to test the effectiveness of the treatments.

1.5. Significance of the Study

The study contributed to identifying the effects of the use of the think-pair-share collaborative digital storytelling instructional strategy and the centralised video-based digital storytelling instructional strategy to improve the academic achievement of elementary school pupils’ learning and attitudes towards Social Studies. That is, individual learners will have a sense of fulfilment knowing fully well that they can confidently influence their learning and improve the level of teamwork with other peers while collaboration is at the centre of their decision making. Learners’ attitudes are expected to be positively influenced in a way that arouses national consciousness, unity in diversity, national tolerance, and respect for others. This study contributes to Social Studies teachers’ awareness of the effects of digital storytelling and media integration when planning and setting learning goals. This will, in turn, enable learners to develop the right techniques to collaborate while learning effortlessly and meaningfully. The study revealed the important sets of skills needed by major actors, teachers, and other stakeholders, such as educational policymakers, administrators, learning experts, and curriculum designers to implement the program. It also enlightened development experts on the need to appropriately integrate the right technological tools into the Social Studies curriculum that could inspire learners’ interest, engagement, and motivation to perform excellently through digital storytelling. More importantly, as a result of this, the learner develops cognitively, psychologically, and socially such that the learner’s ability to lead among peers is enhanced. The study also serves as the right pointer for digital literacy education at the lower elementary level of education. Finally, the findings serve as a scientific basis to show the effective use of digital storytelling and the impact of other moderator variables on achievement in relation to their level of participation with regard to the age and gender of pupils in Social Studies.

1.6. Operational Definition of Terms

Centralised Video-based Digital Storytelling: This is a teacher-led instructional strategy involving instructors’ ability to interact with multimedia gadgets such as phones and laptops to aid classroom instructions and pupils’ learning.

Digital Storytelling Package:An instructional digital storytelling package designed with animated 3D motion graphics, graphical images, pictures, and background sounds, a voiceover to illustration concept drawn from the curriculum via recommended textbook of grade four pupils.

Think-pair-share Collaborative Digital Storytelling: This is a deliberate grouping of pupils to aid interaction that involves critical thinking and shared learning toward a common academic goal.

Pupils’ Achievement in Social Studies:The outcome of an instructional endeavour in Social Studies concept as a result of pupils being exposed to an instructional digital storytelling package. This was measured using the Social Studies Achievement Test.

Pupils’ attitude towards Social Studies: A way of thinking or disposition that affects pupils’ behaviour in learning Social Studies concepts when interacting with digital storytelling instructional packages. This is measured using Pupils Attitude to Social Studies Questionnaire

Elementary School Pupils: State of Osun primary schools is usually referred to as elementary schools, classified into grades one to four. These are primary school pupils, classified into grade one to grade four classes particularly in the State of Osun, Nigeria. This differs from school formation observed in other states in Nigeria

Literature Review

This review focuses on the effect of two modes of digital storytelling strategy on lower elementary school pupils’ academic achievement in Social Studies. The following subthemes were extensively discussed to validate the available research areas:

2.1 Theoretical Framework

2.1.1 Piagetian CognitivistTheory

2.1.2 Constructivist Learning Theory

2.1.3 ASSURE Model of Instructional Design for Integrating Instructional Package in the

Classroom

2.2 Conceptual Framework

2.2.1 Digital Storytelling in Social Studies discipline

2.2.2 Pupils’ achievement in Social Studies

2.2.3 Pupils attitude towards Social Studies.

2.2.4 Think-Pair-Share collaborative strategy and Digital Storytelling Instructional Strategy

2.2.5 Centralized Video-based Digital Storytelling Instructional Strategy

2.2.6Age and Instructional Strategy.

2.2.7Gender and Instructional Strategy.

2.3 Empirical Review

2.3.1 Gender and Achievement.

2.3.2 Gender and Attitude

2.3.3 Age and Achievement

2.3.4 Age and Attitude

2.4 Literature Appraisal

2.1 Theoretical Framework

2.1.1 Piagetian Cognitivist Theory

The theory deals with the nature of knowledge itself and how humans gradually acquire, construct, and use it. Piaget's theory is mainly known as the developmental stage theory. Piaget was interested in how children of different ages made different kinds of mistakes while solving such problems. He also believed that children are not like young adults who may know less; they just think and say words in a different way. By Piaget’s thinking that children have great cognitive abilities, he came up with four different cognitive development stages: sensorimotor, preoperational, concrete operational, and formal operational periods. Highlighting the symbolic function in his theory, the sub-stage is when children are able to understand, represent, remember, and picture objects in their minds without having the object in front of them. The intuitive thought sub-stage is when children tend to propose the questions of "Why?" and "How come?" In this stage, children want to understand everything. Piaget’s cognitive development is the progressive reorganisation of mental processes resulting from biological maturation and environmental experience. He believed that children construct an understanding of the world around them, experience discrepancies between what they already know and what they discover in their environment, and adjust their ideas accordingly. Moreover, Piaget believes that cognitive development is at the centre of the human organism.

The Relevance of Cognitive Development Theory to the Study

This theory reflects each stage of child development and how children manage to develop their cognitive skills. For example, Piaget believed that children experience the world through actions, representing things with words, thinking logically, and reasoning. Storytelling reflects images in the mind of the child; thus, when a story is made, regardless of age, toddlers smile and affirm stories being told while growing. This reflects Piaget’s theoretical perspective, which focuses on the operational and figurative transformation of human development. This theory proposes that at age seven, the child's sensory-motor anatomy is well-developed and can acquire skills faster. The role of digital storytelling is to bridge the gap between conventional teaching styles and storytelling. Digital storytelling brings the story to half its real form, with a combination of pictures in 3D, line drawings, animations, soft background sounds, and real videos to aid better storytelling. This makes knowledge operational in nature, appealing to connections that exist in learners' minds. Instructional designers highlight the psychological implementation and development model to help transform the state of learning into learning instructions. Children of different ages behaved differently in class. Each of these student behavioural patterns is in accordance with either their environmental configuration or the result of parental upbringing. Hence, pupil behaviour in the classroom affects how much and how well students learn. Each pupil had a different assimilation method. One of the most common and easiest ways of assimilation among pupils is multimedia learning, in which digital storytelling is incorporated. This serves as a medium to better enhance thought and imaginations, different from the reality of learners’ awareness levels, and it keeps the information as fresh as possible for a long period of time. It also engages pupils in learning without boredom.

2.1.2 Constructivist Learning Theory

Constructivism is a learning perspective in psychology that argues on the construction of knowledge that humans generate meanings from their experiences as propounded by Jean Piaget, the likes of Lev Vygotsky, John Dewey, and Mary Montessori. Constructivism is a theory that focuses on observation and scientific studies of how people learn. Cunningham (2009) revealed that schools, for the most part, rejected Dewey's participatory approach to learning, preferring the decontextualised, non-experiential, and generalised knowledge found in textbooks,and that modern technology and the use of ICT to construct collaborative learning might return to the Darwinian idea of participatory and experiential approaches to learning. Krutka and Carpenter (2016) perceived the theoretical construct as the most effective means of fostering intrinsic motivation, intelligence, the disposition for social cooperation, and an appreciation of aesthetic experience, and for helping students develop the habits of mind necessary to continually reconstruct their understanding and to direct the course of subsequent experiences. Learners construct their own knowledge and understanding of the world by experiencing things and reflecting on their own experiences. Constructivism as a learner-centred approach proposes that the learning environment should enhance several views or interpretations of realities, knowledge construction, context-rich, and experience-based activities.

The relevance of the Constructivists Theory to the Study

The strategies in this study using digital storytelling will create conducive self-paced learning environments that will task learners' ability to engage in critical thinking and enhance problem skills in learners with facilities that will be provided, thus enhancing knowledge construction and retention in the two-mode digital storytelling learning strategy. Constructivism focuses on how well learners construct knowledge, not how learners bid or attempt to reproduce knowledge. This is because true knowledge emanates from acquired experience. Mental structures and beliefs are used to interpret objects and events, respectively. The most vital tenet of constructivism is that it affords learners the ability to create authentic educational activities that engage the mind and the ability to think about effective strategies to construct their own level of awareness. The curriculum should be deliberate on how learners influence their own knowledge, while the teacher serves as a facilitating guide. Digital storytelling, centralised or in a collaborative sense, affords learners the opportunity to direct their own level of participation, problem-solving, and experiences as learners and their environment affect each other positively; Krutka and Carpenter (2016) revealed that teachers are flexible; sometimes they are the givers of knowledge but often are the facilitators. This theory will make relevant skills available to pupils to engage in activities that will enhance the acquisition of desired learning goals.

2.1.3 ASSURE Model of Instructional Design for Integrating Instructional Package into the Classroom

Most teachers understand that integrating technology into the curriculum is the best way to make a positive difference to education. While many specific strategies can be used to integrate technology into learning instructions, the ASSURE instructional model has been considered more appropriate for achieving the learning goals of this study. The ASSURE model was developed by Heinich, Molenda, Russell, and Smaldino in 1999, and is an instructional model for planning a lesson and the technology that will enhance it. The ASSURE model contains six steps, and the letters in the ASSURE form an acronym. This model is relevant in this study, as it forms the basis on which the instructional package is carefully integrated into class activities. The ASSURE model provides bases on which learners’ characteristics, background, environment, and learning style are well considered before looking into the appropriate technology to be used in the class. The ASSURE acronyms are explained in detail below.

The “A” stands for Analyse the learner: Who the learners are? This step is important because keeping the learner in mind will help ensure that the learning process is planned to a fault for finding materials and resources that will be most appropriate and useful to the learners. Knowing who the learners are involved in (e.g. demographics, prior knowledge, learning styles, and academic abilities) on a multitude of levels, and using this knowledge in every lesson plan.

The first “S” stands for State objectives: it involves a curriculum to teach in the classroom, with specific objectives that will become the focus of individual lessons. What are the objectives? What are the outcomes of lessons that learners will know or learn? Etc.

The second “S” is Select media and materials: When choosing the media and materials to help teach a lesson, the instructor will first choose a method for delivering instruction. For example, the instructor might decide that having learners work in small cooperative groups is most appropriate, or might determine that a lesson is best taught using a tutorial. Select the media that best supplements or enhances the chosen teaching method. Media can include technological solutions (for example, CD-ROMs, DVDs, calculators, software, Internet resources, and videos), print resources, such as textbooks, or any combination of the various media types.

The “U” stands for Utilise media and materials: at this stage, we identify the specific media and materials to help meet learning objectives. In this step, the lesson is taught and the media and materials are implemented. This step should also have a backup plan in place.

The “R” stands for Require learner participation: students are going to find learning more meaningful when they are actively involved in the learning process and not sitting there passively. One major goal of this research study was to determine how learning can be made effective and collaborative. This extends to finding relevant strategies to implement group engagement via thinking, problem-solving, creating, and analysing.

The “E” stands for Evaluate and revise: This is one of the most important steps, but is often overlooked. At this stage, the instructional package is evaluated with the proper strategy, activity, and media, which are pivotal in making learning effective.

The ASSURE model is only one strategy to adequately incorporate innovation into an educational program, the model filled in as a manual for instructional developers of digital stories, so it has not to miss ventures as enunciated by the researcher. Models such as those mentioned above have been discovered to be essential to instructional improvement. It illuminates the instructional developer the sight of who the learner is, where he or she comes from, and what interest or make learning activity engaging to the learner. The research process adheres to the cognizance and caution resource guidelines made available by this model in designing effective learning packages.

2.2.1 Digittal Storytelling in Social Studies

The practice of storytelling is a participatory experience geared towards transmitting meaning in a bid to impart pedagogical or didactic lessons (Conference, 2016). In the past, the authentic vehicle used for influencing morals, preserving historical achievements, and the vital part of instruction was through oral traditions and storytelling (Ogbu 2018). Ogbu vehemently pained on the level of moral decadence in our society, when it revealed that “Certain questions arise: are there certain cultural cues or traditions we lose with the passing of each ‘iroko’ tree in our society? Has modern civilisation and the influence of Western culture changed our perspectives? Or is the problem with how we are able to teach and communicate to our children (means and methods), the values we hold dear, and those that are sacrosanct? pp 148”. Kojian Okolie-Osemene (2016) revealed that the crime rate has been on the incline and has caused us to wonder about the possibility of these issues coming at the heels of broken moral compasses.

However, storytelling has been assessed for critical literacy skills and the learning of theatre-related terms by the nationally recognised storytelling and creative drama organisation Neighbourhood Bridges in Minneapolis. Storyteller researchers in Europe propose that the social space created preceding oral storytelling in schools may trigger sharing(Seker2016) further studies on the role of storytelling in the Metis community have shown promise in furthering research on the Metis and their shared communal atmosphere during storytelling events. Seker focused on the idea of witnessing a storyteller as a vital way to share and partake in the Metis community, as members of the community would stop everything else they were doing in order to listen to or "witness" the storyteller and allow the story to become a "ceremonial landscape”, or shared reference, for everyone present. This was a powerful tool for the community to engage and teach new learners to share references to the values and ideologies of the Metis. Through storytelling, Metis cemented the shared reference of personal or popular stories and folklore, which members of the community can use to share ideologies. In the future, Seker noted that Metis elders wished for the stories being told to be used for further research into their culture, as stories were a traditional way to pass down vital knowledge to younger generations.For the stories we read, the "neuro-semantic encoding of narratives happens at levels higher than individual semantic units and that this encoding is systematic across both individuals and languages. “This encoding seems to appear most prominently in the default mode network. (Dehghani, Boghrati, Man, Hoover, Gimbel, Vaswani, and Kaplan 2017).

Another group of scholars whose main focus revealed the strength of storytelling in teaching mathematics,Abah, Iji, and Abakpa (2018), are of the view that stories narrated by teachers and students during story-time are meant to convey historical messages, encourage the students to academic valour, and deter the cultivation of wrong attitudes and deviant behaviours. Hourani (2015) expands further, that students may not be intrigued with the moral, cultural values in stories, they unconsciously assimilate these values by means of narration and role-playing. Abah et al add that “stories take students on a journey that inspires them to learn about themselves and the world around them” pp 166.

Abah (2016) observed that there is an indication that very few elements of history are embedded in classroom instruction, considering how general history as a subject has fared in the development of curriculum in Nigeria. Hence, Abah et al. (2018) found in an embedded storytelling strategy in mathematics revealed in their outcome that stories are often told to illustrate learning points and motivate learners into action within the instructional context; however, the findings showed that storytelling encourages discussion, improves listening skills, creates enthusiasm or excitement, and drastically develops learners’ creativity level. Fouze and Amit (2018) support this claim by affirming that stories from within students’ culture and previous knowledge contribute greatly to the students’ learning process, help them better understand the study material, raise their motivation, and ultimately, improve their achievement.

Studies have long argued that teachers who use digital storytelling more effectively encourage their students to engage in discussions, participate, and make content more comprehensible (Alismail, 2015). According to Sandaran and Kia (2013), digital stories are new versions of storytelling. Narrating has a rich custom, and has advanced and extended to accept dynamic, contemporary nearness crosswise over settings and capacities. Developing digital strategies is changing the idea of narrating and opening up new conceivable outcomes for collaboratively oriented methodologies. These techniques support repositioning students as co-makers of information, who are accomplices in the meaning of issues, definition of hypotheses, and use of arrangements in the learning condition.

The simplification, interactivity, and affordability of technology have led to the rapid and diverse expansion of participatory storytelling strategies. In 1990, Lambert developed digital storytelling in the virtual world as the co-founder of the Center for Digital Storytelling (CDS) (Alismail, 2015). Digital storytelling has been shown to be a valuable tool to help teachers encourage their students to engage in discussions, participate in instruction, and support the comprehension of content (Kosara and Mackinlay, 2013). This study tested an instructional model designed to empower students in early childhood classrooms as emerging digital storytellers.

There are many ways teachers choose to integrate computer systems, projectors, and other smart devices, as seen in Barrow et al. ’s (2017) conceptualisation. It has been observed that bringing iPads and other mobile devices into classroom instruction impacts student learning. Mobile technology in the classroom should be conceptualised around learners’ mobility, with seamless learning as the primary goal. That is, once conceived as distinct, independent learning experiences should be bound together to create a continuous learning environment. (Sharples, Pea 2014 and Barrow et al 2017). The omnipresence of digital stories and instruments that can be utilised to control data and improve learners’ education is increasing each day. Over the past decade, the deluge of devices, spaces, and practices (i.e. smartphones, digital cameras, editing software, authoring tools, and electronic news sources such as blogs) has urged instructors to use many more approaches and newer media and devices to assist learners in building their own learning curves and to present and offer them all more viably. It is said that digital narrative can offer numerous advantages to learners as they have the chance to figure out how to create their own digital stories. Barrow et al. (2017), in their findings on the use of photo blogs in the Social Studies elementary school pupils class activity, asserted that learners’ benefits of using blogs and photo blogs as an instructional technique include (a) providing an online space for students and (b) promoting increased participation in class.

Kuo, Belland, and Kuo (2017) observed the “increasing of students’ motivation to learn the subject content”. It was noted that students are more likely to engage in blogging activities, incorporating materials and topics of interest to them (Li, Bado, Smith, and Moore, 2013). In other words, learners can upgrade their insight and scholarly aptitudes as they are approached to investigate a subject, search for pictures, record their voice, and then select a specific perspective engaging with digital media. In this examination, our emphasis was on the utilisation of digital storytelling as a vehicle to assist elementary learners with building competence with respect to media gadgets and strengthening collaborations with their pairs beyond the classroom. Yet, within these changing dynamics, there are questions about the use of digital media, where most educational organisations have placed a strict ban on digital media within schools. Welch (2015), Welch and Dooley (2013) supporting these views, observed that most students have experiences with these literacy practices while others do not. They further discovered that too many children in schools do not have the opportunity to participate in digital literacy practices and tools in early childhood education (Burnett, 2010; Flewitt et al., 2015). There is a need for increased understanding of the role of educational technologies in early childhood educational contexts (Blackwell et al., 2015). However, even though Digital Storytelling has existed for a long time, the construct became prominent in the educational arena in the 90s as Joe Lambert developed digital storytelling in the virtual world as the co-founder of the Centre for Digital Storytelling (CDS) (Alismail, 2015).

Since then, the CDS has been influential in developing and disseminating the Seven Elements of Digital Storytelling, such as (a) point of view, (b) a dramatic question, (c) emotional content, (d) the gift of voice, (e) effect of the soundtrack, (f) economy, and (g) pacing. These seven key elements according to Lambert aids teachers in creating digital stories with their students as revealed by (Lambert 1990, Robin 2008 and Alismail 2015). Creating digital stories in education brings with it a number of variables that impact instruction and student interaction.

Hence, literature has contended that instructors should utilize digital storytelling to help innovate learning by urging them to sort out and express their thoughts and information in an individual and significant manner (Robin 2008, Burnett 2010, Dooley 2013, Blackwell et al. and Welch, Alismail, and Flewitt et al., 2015 and Kuo 2017). For instance, Kosara and Mackinlay (2013) expressed this discourse as an “emerging digital storyteller”. In their view, the instructional model focuses on social-emotional development and identifies student voices through writing and digital content construction in the early childhood education context. The concept highlights the place of knowledge construction, critical thinking, and problem-solving learning strategies as means exhibited by early childhood learners by deciding their own learning pace, constructs, and realities.

Digital storytelling provides teachers with a powerful collaborative tool that can be used in their classrooms. This tool can be used to encourage teachers to prepare their own stories for their students and connect with pairs in other schools to build their own collaborative learning spaces (Alismail, 2015). Children are now surrounded by a plethora of screens that may concern adults, yet they may also be a hallmark of our networked society. Digital storytelling has been shown to be a powerful collaboration tool used by teachers to support student collaboration and communication. The tools and practices included in digital storytelling have been useful, as teachers encourage students to prepare their own stories for their pairs and connect with others in and out of school. Given the emerging challenges and opportunities that exist, and the potential for applications of these technologies as educational tools, there is an urgent need to explore how current and future human-computer interactions will impact learners (Read & Markopoulos, 2013; Hess & Saxberg, 2013). Educators make the assumption that developers, researchers, and organisations are delivering technologies that will improve student learning outcomes without negatively impacting individuals (Punchoojit and Hongwarittorrn, 2015). These new developments and technologies also need to be matched with best practices and contemporary paradigms in educational psychology to best scaffold learners.

Teachers can create digital stories inspired by the content of the subject taught to further enlighten them with a fascinating digital illustration or have students express mastery of the content in digital stories. The most powerful example of the use of digital storytelling may be instances in which students are asked to create their own narratives either individually or as members of a small group. Similarly, Alexander (2011) and Seker (2016) claimed that the process of creating a digital story can be group based and helpful in implementing collaborative learning for students. According to Smeda and Sharda (2014), digital stories are an efficient pedagogical tool that increases students’ motivation, while providing a learning environment that fosters the process of story creation through collation, reflection, and interpersonal communication.

The creation of digital stories begins with the selection of an appropriate subject. Three main titles can guide the authors in selecting subjects. The use of digital storytelling in education also increases research-based learning skills for students who think about creating their own stories. Educators can show the digital stories they have created as an example for students planning to create their own stories. After viewing examples of stories, students can be assigned assignments in which they are first asked to research a topic. They will then be expected to select their own appropriate title. Within the scope of the chosen title, work based on information is carried out while considering the seven elements of digital storytelling. According to Smeda, Dakichand Sharda (2014), digital stories are an efficient pedagogical tool that increases the motivation of students, while providing a learning environment for the students in the process of story creation which engages the students through collaboration, reflection, and interpersonal communication. Instructors guide learners on how to use programs such as Movie Maker, Plotagon, and Camtasia, which help with the preparation of storytelling elements. Students who create, tell, and convey their own stories also have the opportunity to become more self-aware. In addition, digital stories can be used to increase the motivation of students, in particular, to read and write, allowing them to personalise the learning experience, gain in-depth and meaningful reading experiences, and provide them with information and skills about the technical aspects of language (Ware and Warschauer, 2005; Ohler, 2013).

The inclusion of digital stories as a complementary tool in curricula can contribute to effective teaching and learning. Robin, (2006) and Smeda et al., (2014). Digital stories also help concretise abstract concepts, transform conceptual content in a more understandable way, and convey content in an interesting manner. Tran (2014) enumerated five relevant elements of cooperative learning: 1) positive interdependence, 2) promotive interaction, 3) individual accountability, 4) teaching interpersonal and social skills, and 5) quality of group processing.

2.2.2 Pupils’ Achievement in Social Studies

Ajani (2013) raised concerns for quality education in the Nigerian education system and opined that quality education is derived from the needs and earnings of teachers to improve the academic outcomes of learners in schools. These vast expectations from teachers make them repositioned for in-service professional development activities that can increase the knowledge, skills, and attitudes necessary for optimum performance for learners. Social Studies, as stated earlier, is a very broad discipline that cuts across other fields such as Geography, History, Law, Philosophy, Political Science, Psychology, Religion, Sociology, Economics, Anthropology, and Archaeology. Abbah et al. (2018) further justified the inclusion of these various subject areas in Social Studies. They declared that most of the life decisions an individual takes have to do with events of the past (history), physical and cultural objects (geography), power struggle (Political Science), satisfaction with unlimited resources (economics), and understanding the values, customs, and cultures of groups and relationships among men in general (sociology/anthropology). The primary purpose of Social Studies is to help young learners develop the ability to make informed and reasoned decisions about the public good as citizens of a culturally diverse, democratic society in an interdependent world. According to Abimbola (2004), Danlandi (2009) and Abbah et al (2018) an individual exists in a world in which he is surrounded by people, objects, institutions, and events. These environmental factors all have roles to play in him, as he struggles to survive. Social Studies education, therefore, draws its contents from social science subjects and from the environment in which the child exists and integrates them in order to help the child develop complete knowledge and reflective thinking.

However, studies have recognised various elements that might be responsible for students' poor academic outcomes and the university specifically. Some of these components incorporate learners' traits, quality of students admitted into universities, parental attitude toward their children’s education, government's lack of sufficient attention and support for training, government's conflicting and clashing educational policies, the tone of the school (discipline) as set by the school authority, deficient support, improper administration and initiative, and disengagement with the economy (Materu 2007; Agharuwhe and Ugborugbo 2009; Shabani 2013; Okebukola 2014; Adeyemi 2017). In comparison with cooperative learning techniques, lecture-based teaching has been reported to be less effective in meeting the demands of high rates of cognitive and academic outcomes (Slavin, 2011, cited by Tran, 2014). According to Ajao, cited in Adeyemi (2017), students’ academic achievement has been connected with the instructor’s adequacy in terms of teaching and learning. Thus, teachers appear to have a significant impact on learners' academic accomplishments. Educators likewise assume the critical role of interpreting instructive strategies into activities and learning encounters at the classroom level. The disparity in academic achievement among learners is evident from day one, when learning is initiated and maintained until the university level. Unless preschool learning and early primary school assistance are provided, underperforming pupils are rarely able to catch up.

According to Robin in Aktas and Yurt (2017), digital stories have six basic elements: perspective, interesting questions, emotional content, use of sound, economy, and speed. In addition, Aktas and Yurt (2017) opined that programs such as Windows MovieMaker, MS PowerPoint, MS Photostory, Imovie, and Scratch can be used to create digital stories. There are also several websites that help learners create digital stories in the web environment and support teamwork in this process (Kocamanand Karoğlu, 2015). Aktas and Yurt (2017) conducted a study to test the effectiveness of digital storytelling on academic achievement; however, the results showed that there was a significant difference in the experimental group, exposed to practiced digital storytelling, compared to the control group, who were exposed to the existing traditional curriculum. The achievement test scores obtained from the study by students in both groups increased as a result of digital storytelling treatments. However, the scores in the experimental group were higher. Scholars’ findings suggest that digital storytelling has a positive effect on student achievement.

The approach is an educational method in which a group of learners share ideas and thoughts to learn and improve themselves through progressive togetherness channelled towards academic success (Saborit et al. 2016). Social Studies, a discipline by nature, includes many abstract concepts. Meanwhile, the use of digital stories in teaching Social Studies should be considered an effective way to concretise abstract concepts, increase continuance in learning, make learning appeals to multiple senses, and develop creative thinking.

2.2.3 Pupils attitude towards Social Studies

According to Nunnally, inAbbal et al (2018) “Attitudes are predisposition to react negatively or positively in some degree towards a class of objects, ideas, institutions or positively in some degree towards a class of objects, ideas, institutions or people”, Abbah et al expand further, that predisposition implies the state of readiness to respond in some preferential manner towards a specific object event or idea. For instance, a student is faced with different issues, and so as to adapt to the issues and to fulfil their needs, the student builds an ideal attitude towards objects and individuals that fulfil their needs. In this manner, the students’ questions regarding the overall merit of social studies education in meeting their future needs could be a delight in the advancement of positive attitudes towards social studies education. Abbah et al (2018).

However, Social studies as a school subject strongly emphasises the development of the affective domain that can guarantee the promotion of unity in diversity. It tends to inculcate in students the ideal values (honesty, integrity, etc.), national consciousness, awareness, positive attitudes of togetherness, comradeship, and cooperation despite diversity in race, desires, beliefs, aspirations, religion, and the desire to fit in and gain pair acceptance, which can have powerful influences on adolescent behaviour (Wentzel, 2017).To attain these objectives, schools require teachers (as role models) to take the lead in changing the focus of social studies lessons from academic to socialisation. Through the verbal and visual presentation of instructions or information to pupils, who are expected to develop a common set of understanding, appropriate skills, competencies, attitudes, and actions that increase human interaction, coexistence, relationship, and societal development (FRN, 2013).

Januarsi and Khafid (2019) observed in their findings, revealed the impact of the problem-based learning model had over the think-pair-share collaborative instructional strategy in effecting attitudinal changes in learners. However, this research claim was strongly supported by Rahmatin and Azinar (2017) and Fitrianawati (2016), who employed the same strategy in their investigations.

Hence, the attitude of pupils toward the concept of the social studies interdisciplinary approach which prompted the drafting of social studies teachers from composite disciplines such as government, geography, history philosophy, sociology, economics, etc., has heightened the plurality of instructional methods and techniques, unclear duties/roles, and ambiguity of assignment that hampers an in-depth teaching of concepts, modes of thinking, and analysis of contemporary issues which have greatly influenced the interest of learners and the abstractness of the subject. Digital storytelling has been shown to be a powerful collaboration tool used by teachers to support student collaboration and communication. The tools and practices included in digital storytelling have been useful, as teachers encourage students to prepare their own stories for their pairs and connect with others in and out of school. Teachers can create digital stories inspired by the content or have students express mastery of the content in digital stories.

2.2.4 Think-Pair-Share Collaborative Digital Storytelling Instructional Strategy

The think-pair-share approach engages learners to think silently about a question, pair up, and discuss their possible responses and answers. Learners’ pairs think and share their responses with other pairs, teams, or the entire group (Othman and Othman, 2012). Chen and Chiu outline three functional sequences needed in the incorporation of Think- pair-share in instructional design as an individual, intra-group, and inter-group. Shelby-Caffey, Úbéda, and Jenkins (2014) describe a digital storytelling project that was used to teach the fifth-grade processes to create a movie based on a recommended class novel. In their view, one of the projects examined an experiment carried out on fifth-grade students, showing that students went from passive observers to active learners. Fifth-grade students first participated in a shared reading of a novel and then used digital storytelling, engaging in what instructors had assigned participants to do, such that the learning process involved active participants taking control of their learning. The researchers summarised that the reward for their investigation was incredible and worth every minute invested in the study.

In educational settings, different technological tools and programs, such as podcasts, infographics, and other types of presentations, make it easy for instructors to create digital stories (McLellan 2007; Bower 2015). Digital stories weave “the art of telling stories with a variety of digital multimedia, such as images, audio, and video” (Robin, 2015). It accommodates the opportunity for the teacher to pose a question, for students to think and share in pairs, and for each pair to share back to the whole class and by so doing, collaborate with pairs. Thus far, pair collaboration has elaborated on learning contribution processes. Thus, think-pair-share promotes a variety of responses, including analytic, comparative, inferential, and evaluative reasoning, and plays a positive role in improving students’ oral communicative skills and enhancing their motivation to learn better (Raba, 2017).

However, Januarsi and Khafid (2019) revealed that various studies have proven the effectiveness of problem-based learning models and think pair share models separately, but there is no comparison between the effectiveness of both models to ascertain to what extent the effectiveness of both strategies could be rated. Meanwhile, Januarsi and Khafid (2019) observed that the experimental group of the problem-based learning model showed higher learning outcomes when compared to the experimental groups exposed to collaborative think-pair-share learning strategies. The findings of Januarsi and Khafid (2019) were in agreement with the outcome of Fitrianawati (2016), who revealed that the problem-based learning model is more effective in improving student learning outcomes than the think-pair-share model. Research conducted by Hidayat and Muhson (2018) showed that the think-pair-share collaborative instructional strategy was more effective than the conventional instructional strategies employed by instructors. This strategy could then be said to be very effective in enhancing student learning outcomes and improving collaboration.

This strategy can be said to be based on the adage that no one is an island of knowledge. Sutrisno et al (2019), Opined that TPS technique is a method that has been developed to enable learners to think about a given topic, to be formulated into ideas by all learners, and then the ideas are shared to the “group members”, and other learners within a predefined grouping

2.2.5 Centralized Video-based Digital Storytelling instructional Strategy

Digital storytelling and centralised video-based learning are combined strategies. Storytelling is always a social phenomenon involving the narrator and listener. Hence, a separate perspective is drawn between story production and story consumption when decoded; thus, narrative transportation evolves in the receiver’s mind (Van et al., Visconti and Wetzels 2014). It is a story receiver who experiences narrative transportation, aside from understanding the qualitative structure of digital story videos. In addition, to explore the experience of the receiver in the consumption phase of the story, the digital story is decoded and consumed. (Pera and Viglia, 2016). The creation of digital stories in the classroom is a powerful instructional technique, but the strategy is more helpful when it is individualised for students, even though the joint/group classroom activity encourages intra-group discussion and the contribution of students.

However, digital storytelling, defined as video communication that incorporates vivid images and sounds with rich narratives, can be a meaningful learning experience for a variety of content areas, ranging from kindergarten to university levels (Lambert, 2013; Robin, 2008; Shelton, Archambault, & Hale, 2017). Digital stories are portable as they are documented and shared via digital texts and tools when these materials are communicated to learners in a more intimate environment, which speeds up the learning process. This allows teachers to document the work process and product of the learner by observing his/her attentiveness and interaction during the class while allowing the students to express themselves. Even with these opportunities to embed digital storytelling in educational settings, questions remain about the role and place of digital screens and devices in early childhood education. Mentoring students in digital storytelling may seem overwhelming in early childhood educational settings, but the focus should be on core learning objectives, building capacity over time, and supported by plans for mentoring and the targeted professional development of teachers. This guidance is identified in the joint position statement of the National Association for the Education of Young Children and the Fred Rogers Center for Early Learning and Children’s Media at Saint Vincent College (2012).Grant and Basye (2014) defined the digital learning approach as a tool for pupils, helping them realise student-centred learning models by allowing learners to take ownership, accountability, and responsibility through a process. When used for personalised learning and teaching, ICT can transform the process and organisation of education.

Digital storytelling is an especially good technology tool for use in instructional settings, as it combines research, creation, analysis, and combining visual images with written text (Cherry, 2017). Robin, Pierson (2005) and Cherry (2015) expand on this by indicating that integration of visual elements with written text both enhances and accelerates student comprehension. Thus, digital storytelling production is particularly compelling because of its emotional and multimodal nature, which combines rich narrative stories and stimulating images that are salient, memorable, and compelling enough to aid learning and interest in learners.

2.2.6 Age and Instructional Strategy.

Age is not considered to be a factor in determining the learning capability of every human. Younger learners, such as early childhood or elementary school students, were not excluded from this category. Their achievement, reaction, behaviour, rate of assimilation, relation with their pairs, the extent to which they exercise their minds and brains, and functions of age, even though in some cases, students assimilate faster and comprehend easier when younger, and research has shown that learning cuts across every age with no limitation. Pupils giving expressions during class activities when it comes to school and learning can exert great influence, so the attitudes and actions of teachers and families can also play a vital role. However, other studies, as revealed by Aransi (2018), opined that there is no appropriate age for learners to enter school because they fact that learners do not all experience growth at the same pace. He further stated that early childhood education programs should be planned and focused on handling school tasks rather than on age. While John, Jackson, and Simiyu (2015) support this claim by stating that the chronological age of learners had a significant bearing on his/her academic performance such that the younger learners had the potential to perform better than their oldest counterparts in a teacher-made test. This is to collaborate with the perspective of Aransi et al. (2018) that early childhood should base its focus on school tasks rather than the age of the learner, which when looking at the younger learner could outsmart the other counterparts.

Hence, Azuka and Kurumeh (2015), in support of the above assertion, examined the effect of emotional intelligence skills, which enable students to thrive to improve their academic achievement, mostly in geometry. They further revealed that students’ emotional skills and intellectual status are a function of their age, which in turn determines their readiness for school, academic performance, and productivity. Another argument focuses on the aspect of productivity: with increasing age, working individuals tend to exhibit relatively high performance levels, but this exhibition of high performance is restricted to a certain age gap; however, there is a claim that with increasing age, performance tends to decline. (Kotur and Anbazhagan, 2014).

2.2.7 Gender and Instructional Strategy.

Gender is one of the personal variables that have been related to the differences found in research studies, and scholars have attributed the study to motivation, academic achievement, interest, and perceptions. Research on gender differences in cognitive processes, academic achievement, interest, stereotypical perceptions of everyday behaviours, and the ability to perform various tasks have been neglected (Dev 2016). Virtually everyone concerned with education places a premium on academic achievement, and studies have demonstrated the existence of different trait patterns in male and female individuals. Thus, female learners tend to place more emphasis on effort when exhibiting the relevant skills needed to aid positive academic outcomes, and researchers have often investigated the significant effect of gender. Male and female learners are likely to exhibit the same traits in learning situations. Researchers have found narratives relevant to various studies of learners’ pair groups.

Learners’ academic outcomes and social lives are closely intertwined in school (Liem, 2016; Shim and Finch, 2014); thus, male learners usually attribute successes to stable internal causes such as efforts, thus showing their peculiarities which enables them to enhance their own image of themselves, while the differences in the scholastic achievements of males and females are generally attributed to biological, social, and cultural causes, and these influences have clear ramifications for the cognitive development of girls and boys.

Viviline, Enose, and Dorothy (2013) identified vital elements that could influence disparity in academic achievement of learners ranging from school levies, indiscipline, family problems, the entry behaviour of the child, lack of interest in the girls’ side to complete their work, the attitude some parents have towards the girl child compared to the boy child, and lack of required school materials such as books as predictors of girls’ academic achievement. Similarly, Ahmad and Yusuf (2013) pointed out elements such as poverty, involvement in household activities, investments in boys’ education, early marriage, absence of proper security, lack of child interest, parents’ death, school distance, disrespect, and stubbornness expected from female students, and religious beliefs as some of the psychosocial factors which influence high dropout rates among female students compared to their male counterparts. In terms of personal characteristics, some students find themselves in school late in life. (Aransi2018).

2.3.1 Gender and Achievement

Cooperative learning has proven to be efficient in various branches of learning, such as social science, math, and the arts (Cheung & Slavin, 2013; Hossain & Tarmizi, 2013; Lehrer andLesh,2013). However, a recent meta-analysis of 65 studies found different results between the subjects (Kyndt et al., 2013). Saborit et al (2016) concluded that subjects with non-linguistic exercises such as Maths show more positive effects than linguistic subjects such as Literature or Social Science. He further explained that math tasks are usually more hierarchical, and that help from other students may favour faster progress. In pair learning activities, students learn faster when some start from superior stages of knowledge, which is beneficial for the less brilliant students (Van-Blankenstein, Dolmans, Vander-Vleuten, and Schmidt, 2013). Stressing the importance of collaborative instructional strategies.

There are persistent gender gaps in school achievement, with girls outperforming boys worldwide (OECD, 2015; Stout and Geary, 2015). Not only are girls ahead of boys in language and literacy skills, but they also achieve better grades in stereotypically masculine subjects, such as maths and science (Voyer & Voyer, 2014). In addition, boys report lower levels of school engagement relative to girls in international studies (Lam, Jimerson, Kikas, Cefai, Veiga, Nelson, Zollneritsch, 2012).

Despite the proliferation of research on achievement goals, only a small subset of studies have reported gender differences (Butler & Hasenfratz, 2017), and few have examined how these differences in achievement goals may translate into gender differences in engagement and achievement. Mentoring students in digital storytelling may seem overwhelming in early childhood educational settings, but the focus should be on student learning objectives, building capacity over time, and supported by plans for mentoring and the targeted professional development of teachers. This perspective has mostly been supported and identified by a statement by the National Association for the Education of Young Children and the Fred Rogers Center for Early Learning and Children’s Media at Saint Vincent College, 2012