1. Introduction

Ovarian cancer is more frequently diagnosed in post- menopausal patients, and it is considered an agressive tumor that is usually diagnosed at an advanced stage. Treatment for ovarian cancer is multimodal, and consists of a combination of surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy in the majority of cases. Surgery is the main pilar of treatment, and it is considered as the initial tool when the extension of disease makes amenable its complete resection [

1]. After initial surgery, a great number of patients require postoperative chemotherapy, depending on FIGO stage and histology. In some cases, the extension of the disease or the baseline condition of the patients, mostly on elderly patients, does not allow a complete surgery, so the treatment starts with neoadjuvant chemotherapy [

2]. After three or four cycles, reevaluation is made in order to propose interval debulking surgery if complete excision is amenable or, on the contrary, to complete chemotherapy [

3,

4]. Despite all therapeutical efforts, ovarian cancer is still the first cause of death due to gynecological malignancies [

5].

Clasically, surgery for ovarian cancer was made by an extended laparotomy, which makes possible a proper examination and access to the upper abdomen [

6,

7]. The introduction of MIS has lead to doubts to its applicability to gynaecological oncology procedures [

8]. The nature of ovarian cancer and its extension into the abdominal cavity, for cases with advanced disease, is conducive to maintain the laparotomic approach in the majority of cases, since complete cytoreduction is the most important prognostic factor [

9]. Nonetheless, MIS may represent a valid option in selected cases, that would diminish surgical complications [

10]. Furthermore, the shorter recovery time after MIS allows an early onset of adjuvant chemotherapy [

11].

The different surgical indications in ovarian cancer where MIS may be applied includes: staging surgery for early stage disease, interval debulking surgery for advanced disease after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and primary debulking surgery for very selected cases.,

The role of MIS for staging surgery (SS) in early- stage ovarian cancer has been subject to a large number of studies. Some of them have shown similar effectiveness than laparotomic procedures considering number of resected lymph nodes or risk of upstaging due to tumoral rupture [

12,

13]. MIS offers a faster recovery, shorter hospital stay and reduced blood loss. Nonetheless, the majority of studies have a limited evidence and might also be influenced by confounding factors [

14]. Most studies are founded on retrospective evidence.

Interval debulking surgery (IDS) is the elected treatment when the extension of the disease does not allow a complete surgical removal, so neoadjuvant chemotherapy is administered in order to diminish tumoral burden [

15]. MIS has also been postulated for IDS, since the extension of disease is less due to adjuvant treatment, allowing a complete cytoreduction [

16]. With this indication, MIS has shown similar prognosis compared to laparotomy, with less rate of complications [

17]. MIS might be laparoscopic or robobic surgery [

18]. Retrospective evidence has shown no difference in 3-year survival among patients that underwent laparotomic compared to MIS IDS [

19]. Neverthless, again, the quality of the studies and its retrospective nature may have influenced these results.

The role of MIS for prymary debulking surgery in advanced ovarian cancer is practically limited to evaluate tumor resecability rather than to serve actually as a surgical approach for the surgery [

20]. There is scarce evidence regarding its applicability for advanced stages, and it has shown lower rates of lymph node dissection and disease resection compared to laparotomý [

21]. There is not adequate evidence that supports the use of MIS for advanced stage disease as a primary treatment [

22].

In addition, MIS is related to possible complications inherent to the surgery, such as tumor spillage and port- site metastasis, that also need to be considered when planning an ovarian cancer surgery [

23,

24,

25].

Since there is still scarce evidence about the role of surgical route of approach for the treatment of ovarian cancer, our aim was to evaluate the advantages of MIS in the management of ovarian cancer among young patients.

2. Material and Methods

We conducted a multicenter retrospective study with the participation of 55 Spanish hospitals. Patients with diagnosis of invasive ovarian cancer from 2010 to 2019 were collected. Our study intended to analyze characteristics that might be differential in younger patients, so age was an excluding factor. All patients had ages from 18 to 45 years old and were diagnosed of invasive ovarian tumors of any histology with FIGO stage I- IV. Patients outside that age range or with diagnosis of benign or borderline tumors were excluded. The study was approved by the Hospital Clinico San Carlos Ethics Committee (intern code 20/775-E) and, in order to participate, all collaborating hospitals had to obtain the approval of their own ethics committee.

In order to confirm malignancy, histological analisis was compulsory, so the totality of patients underwent surgery. Surgical planning varied depending on the initial suspicion for malignancy and the extension of disease. Patients with highly suspicious tumours underwent one surgery with intraoperative frozen section to confirm malignancy and proceed with the cytoreductive or staging surgery if possible. In advanced tumors, if complete cytoreduction was not possible, surgery was done with diagnostic and explorative purpose, and patients were referred to neoadjuvant chemotherapy after confirmation of malignancy.

MIS included laparoscopy or robotic surgery. Selection of the approach was based on surgical intention, suspicion for malignancy, extension of disease, tumoral size and surgical team experience. After initial surgery, patients could be referred to primary chemotherapy, adjuvant chemotherapy or observation, based on national guidelines. If neoadjuvant chemotherapy was administered, surgery would be postulated as an interval procedure after three or four cycles, if a complete cytoreduction was possible.

PFS was considered as the time, in months, from the initial diagnosis of ovarian cancer to the date of the recurrence diagnosis. OS was defined as the time, in months, since the first diagnosis until the decease date.

Statistical Analysis

Absolute frequencies and proportions were used to present categorical variables and mean (standard deviation) were used for continuous variables. Comparisons between groups were performed using the Student’s t-test for comparisons between groups of continuous variables and the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables as appropriate. Survival analysis was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. The log-rank test was used to assess survival differences between groups by univariate analysis. The multivariate cox proportional hazards regression modeling was used to identify the prognostic clinical-pathological features independently associated with OS and progression free survival (PFS). All the tests were two-sided, and alpha error was set at 5%. The analyses were performed using STATA 15.1 (StataCorp LLC, Texas, USA).

3. Results

A total of 1144 patients were collected. Among them, 867 (75.8%) underwent laparotomic surgery and 277 (24.2%) were treated by MIS. Histology was epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) in 992 (86.7%) patients and non epithelial ovarian cancer (non-EOC) in 152 (13.3%) patients. Early-stage tumors (FIGO stage I and II) were present in 630 (55%) patients and advanced- stage tumors (FIGO stage III and IV) in the remaining 514 (45%) patients. The mean age of the patients was 36.5 (SD 6.4) years old in the MIS group and 38.4 (SD 6.5) years old in the laparotomy group. Suspicion for malignancy was low in 155 (13.5%) patients, intermediate in 244 (21.3%) patients and high in 675 (59%) patients.

Data such as age, tumor size, FIGO stage, body mass index (BMI), histology, preoperative ASA and suspicion for malignancy were analyzed and compared among both surgical approaches (

Table 1). Statistically significant differences were found in all of them but BMI, ASA and preoperative ECOG. Detailed FIGO stage is reported in

Table 2.

Considering surgical procedure, laparotomy was the elected surgical approach in 345 (39.8%) cytoreductive surgery, 287 (33.1%) staging surgery, 142 (16.4%) interval debulking surgery and 93 (10.7%) fertility- sparing surgery. On the other hand, MIS was chosen in 45 (16.25%) cytoreductive surgery, 155 (55.95%) staging surgery, 8 (2.9%) Interval debulking surgery and 69 (24.9%) fertility- sparing surgery. The differences found were statistically significant (p<0.0001).

Complications such as blood loss, lenght of surgery and hospital stay were higher in the laparotomy group, and were statistically significant. No significant differences were found on the tumoral rupture rate between groups (

Table 3).

A multivariate analysis has been conducted to analyze OS based on age, FIGO stage, ASA, histology, tumoral rupture and surgical approach. Data are shown on

Table 4.

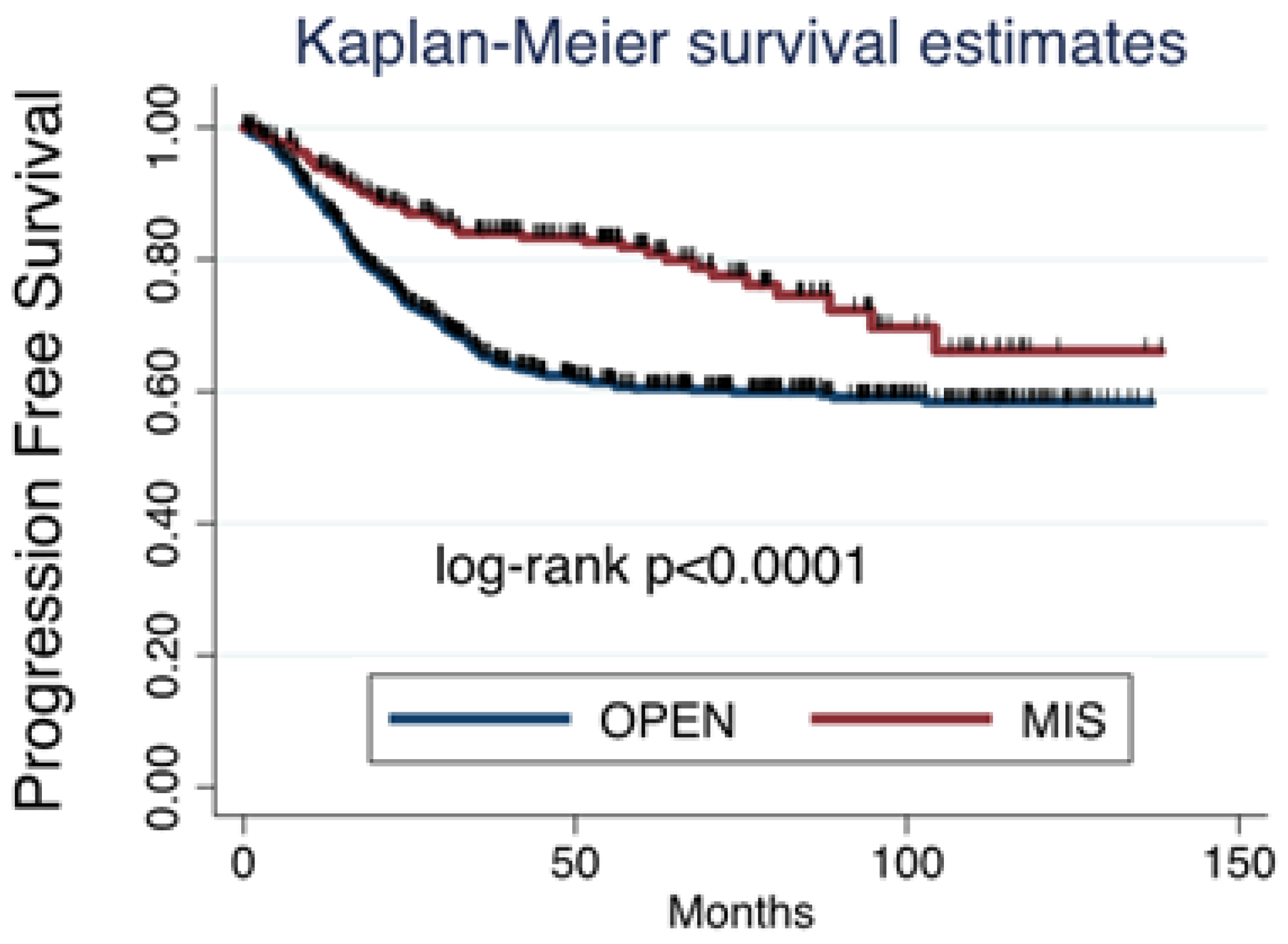

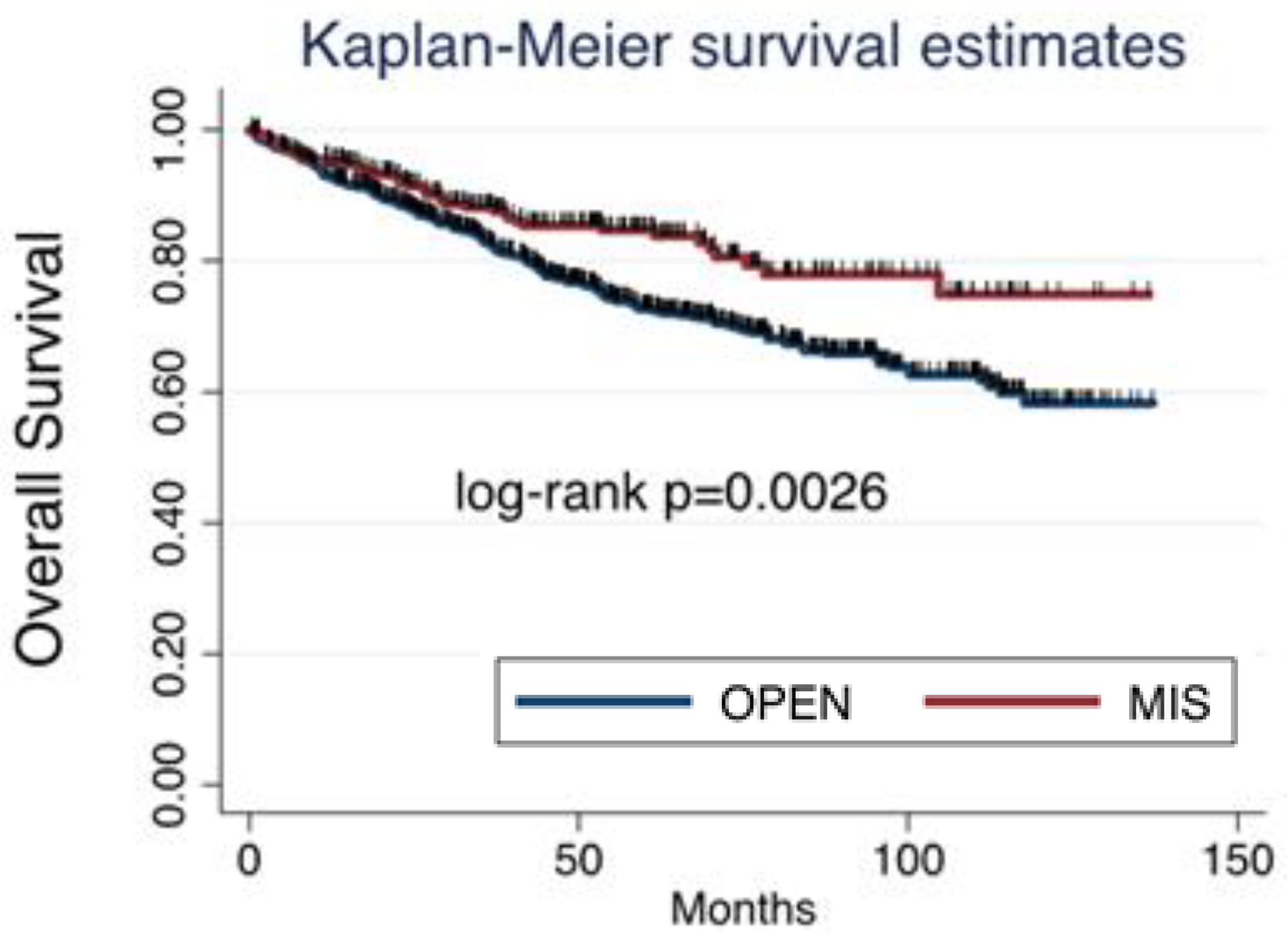

Among all cases collected, 353 (30.85%) patients had relapse of disease, which were 302 (26.4%) after open surgery and 51 (4.45%) after MIS. Considering survival, death was reported in 199 (17.4%) patients, being 169 (14.8%) in the open surgery group and 30 (2.6%) in the MIS group. Both progression free survival (PFS) and overal survival (OS) were significantly worse after open surgery than after MIS (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2).

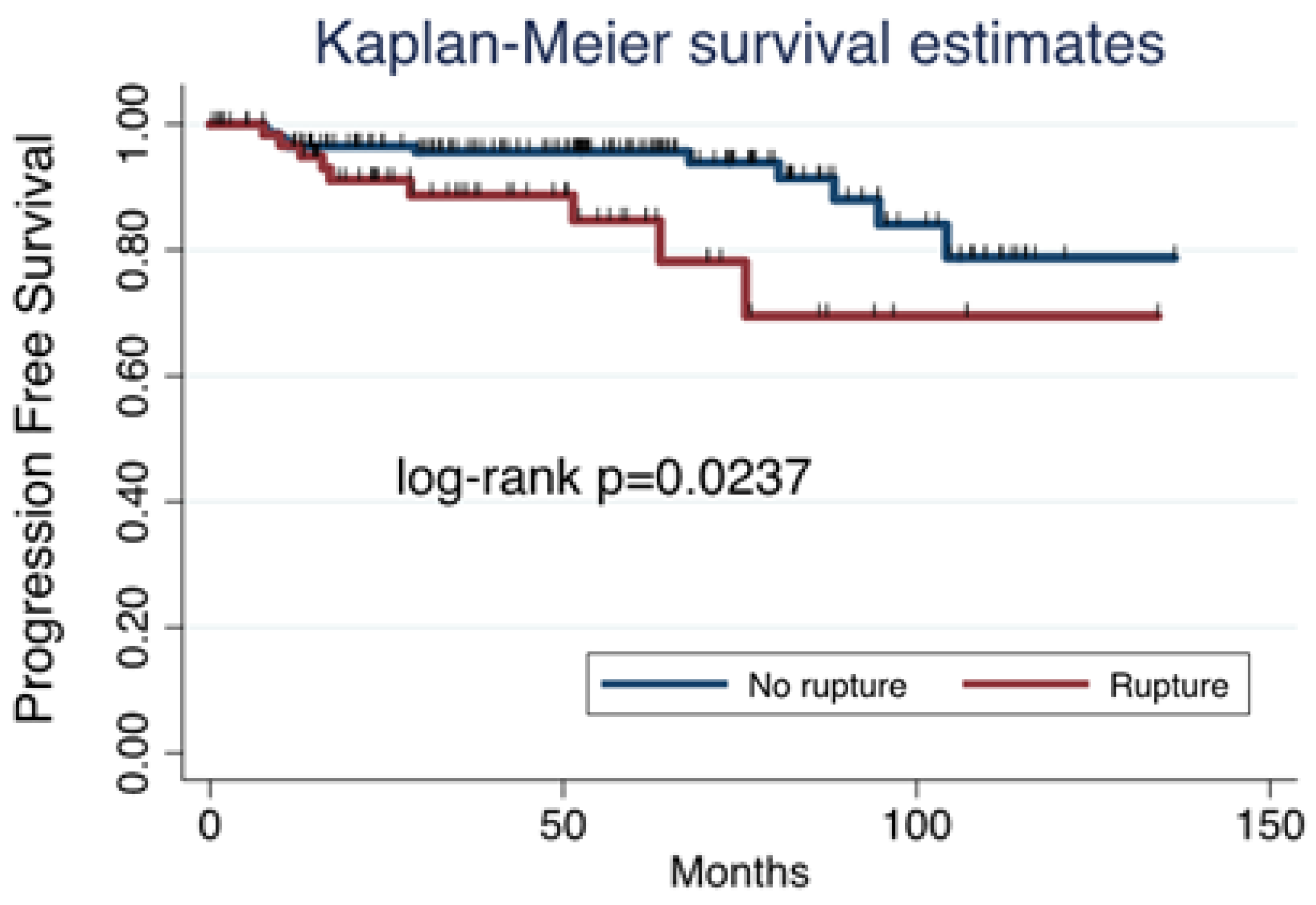

In the MIS group, PFS was influenced by tumor spillage, as it was higher in those tumors that were removed without rupture (

Figure 3).

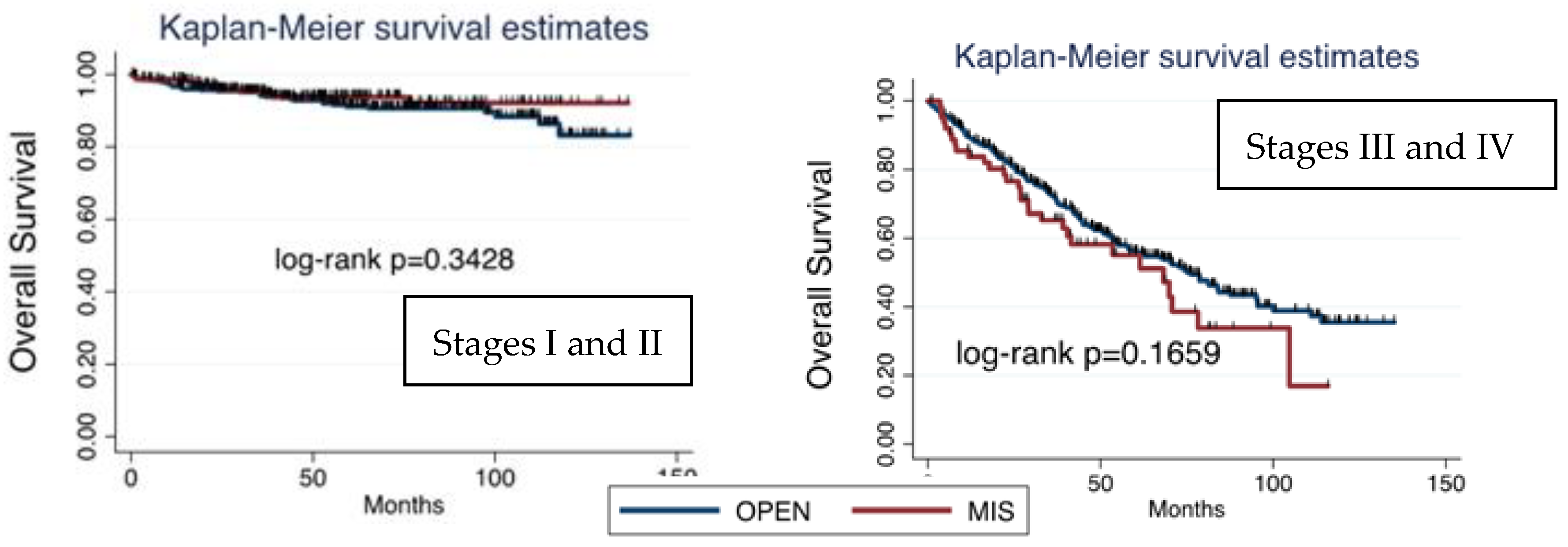

Considering survival based on FIGO stage and surgical approach, OS was higher on early- stage tumors (FIGO stages I and II), and, within them, the prognosis was better in patients undergoing MIS. On the other hand, OS in advanced stages was lower than in early stage and, in contrast to early stages, was even worse after MIS than after laparotomy. Nonetheless, no significant differences were found (

Figure 4).

4. Discussion

Our findings may suggest that MIS applied to ovarian cancer surgery seems to entail not only similar prognosis compared to laparotomy, but even lower rates of recurrences and deaths. Nonetheless, the role of MIS for ovarian cancer is still limited, in the majority of cases, to early- stage tumors and staging surgery, so data have to be interpreted with caution. First, most of the patients have undergone laparotomic approach, so both groups present a clear asymmetry. Second, MIS has been mostly used in early- stage tumors, so patients with greater extension of disease and, therefore, worse prognosis, have been more frequently treated with laparotomy.

Surgical approach for ovarian cancer surgery has been changing in the past years, with the application of MIS in selected cases [

26]. MIS in staging surgery for early- stage tumors have shown its safety when performed by a trained surgeon [

27]. In our series, 77.3% of the patients that underwent MIS surgery were early- stage tumors, and 55.95% of the MIS were for staging purpose. After its application for early- stage tumors, effort has been also focused on the role of MIS for IDS and cytoreductive surgery. IDS can be performed by MIS, as stated in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, although larger analysis are necessary to assure a good selection of patients [

28,

29]. In our study, only 5.3% of the IDS were performed by MIS, compared to the 94.7% that were laparotomic. Finally, safety of MIS for cytorreduction in advanced stages or recurrences still lacks of evidence to prove its safety [

28,

30,

31]. In accordance with this, MIS was elected in only 45 of our 390 cytoreductive procedures, which represents 11.5%.

Indication of MIS for ovarian cancer is highly influenced by factors such as age, tumoral size, FIGO stage and histology [

32]. Laparotomy is more frequent in elder patients, as prognosis improves at younger age [

33]. Our study collects only patients younger than 45 years old, so the rate of MIS might be higher than in other series. Tumoral size is related with risk of tumoral rupture during MIS, as shown on LOChneSS Study [

34]. Tumors that underwent MIS surgery were significantly smaller than those treated with laparotomy, in line with the results of other studies [

35]. As for histology and FIGO stage, MIS has proven its efficacy and safety in early- stage tumors [

36]. On the other hand, its safety for advanced stage has not been proven, since an optimal removal is the most important prognostic factor [

37]. In our series, MIS was mainly chosed for early- stage tumors; only 22.7% of the MIS performed were for advanced- stage tumors.

A multivariate analysis was conducted considering those variables, finding statistically significant differences among them regarding overall survival (OS). OS was higher in patients of younger age, early- stage tumor, with an ASA < 2 or non- epithelial tumors. On the other hand, non- significant differences on OS were found concerning tumoral rupture and the surgical approach (

Table 4).

Recent studies have been postuled to address the deficiencies of previous studies. The LOChneSS study has postulated the effectiveness of a predictive model for ovarian rupture in MIS [

34]. LANCE and KGOG are two on- going randomized studies carried out to compare open vs. MIS, whose results are expected to discern the actual safety of MIS for IDS [

38,

39]

In conclusion, MIS has been predominantly used for staging purpose in early- stage tumors, proving its oncological safety when no spread of disease is presumed. Significant differences concerning OS have been found comparing MIS to open surgery, although both groups are not homogeneous, with a striking increase of advanced stages in the open surgery group. MIS has proven to have a role in the treatment of ovarian cancer, without compromising its oncological safety, but with a extremely cautious selection of cases. Current studies have failed to prove the widespread safety of the use of MIS for ovarian cancer, beyond its use in selected cases [

40]. Currently, laparotomy remains the standard of care for ovarian cancer surgery, as provided in ESMO and ESGO guidelines [

41]. More studies and addition of prospective evidence are both necessary in order to identify those patients that will benefit of the advantages of the MIS without compromising their oncological safety. Hopefully, the on-going studies will add high quality evidence to our clinical practice, to homogenize the use of minimally invasive surgery for selected ovarian tumors.

5. Limitations

Our study is retrospective and multicenter, so there might be a variability of criteria depending on the hospital at the time of choosing the route of approach. Moreover, the groups are not balanced, since laparotomy was the preferred surgical approach due to the stage of the disease. These factors need to be considered at the time of evaluating our results.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank the whole YOC- Care Group Collaborative for their full support and contribution to the manuscript: Alcalá MM (Hospital de Poniente, Almería), Alkourdi A (Hospital Virgen de las Nieves, Granada), Alonso M (Hospital Universitario de Guadalajara, Guadalajara), Alonso T (Hospital Universitario de Burgos, Burgos), Álvarez R (Hospital Universitario Santa Cristina, Madrid), Amengual J (Hospital Universitario Son Espases, Palma de Mallorca), Aparicio I (Complejo Hospitalario Universitario, Pontevedra), Arencibia O (Hospital Universitario Materno Infantil, Canarias), Azcona L (Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Macarena, Sevilla), Baciu A (La Paz University Hospital, Madrid), Bayón E (Hospital Clínico de Valladolid, Valladolid), Bellete C (Hospital General de Segovia, Segovia), Bellón M (Hospital Clínico San Carlos, Madrid), Boldó A (Hospital La Plana, Castellón), Brunel I (Hospital Quirón Málaga, Málaga), Bustillo S (Hospital Universitario de Salamanca, Salamanca), Cabezas MN (Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Macarena, Sevilla), Cano A (Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón, Madrid), Cárdenas L (Hospital Josep Trueta, Gerona), Chacón E (Clínica Universitaria Navarra, Navarra), Coronado P (Hospital Clínico San Carlos, Madrid), Corraliza V (Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal, Madrid), Corredera FJ (Hospital Universitario de Salamanca, Salamanca), Couso A (Hospital Príncipe de Asturias, Madrid), Díaz B (Hospital Clinic Barcelona, Barcelona), Duch S (Hospital Universitario Infanta Sofía, Madrid), Fernández M (MD Anderson Cancer Center, Madrid), Fernández MJ (Complejo Asistencial de Zamora, Zamora), Fidalgo S (Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias, Asturias), García J (Fundación Jiménez Díaz, Madrid), Gil- Ibánez B (Gynecologic Oncology and Minimally Invasive Surgery Unit, Gynecology and Obstetrics Department, University Hospital 12 de Octubre, Madrid), Gilabert- Estelles J (Hospital Universitari Valencia, Valencia), Gómez AI (Hospital General de Segovia, Segovia), Gómez B (Hospital Virgen de la Arraixaca, Murcia), González L (Hospital Universitario de Torrejón, Madrid), González MH (Hospital Príncipe de Asturias, Madrid), Gorostidi M (Hospital Universitario de Donostia, San Sebastián), Herrero S (Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro, Madrid), Hidalgo E (Hospital Universitario San Cecilio, Granada), Iacoponi S (Hospital Quirón Madrid, Madrid), Izquierdo R (Hospital de Igualada, Barcelona), Lamarca M (Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet, Zaragoza), Lara AM (Hospital Virgen de las Nieves, Granada), Lete I (Hospital Universitario Araba, Vitoria), Llueca A (Hospital de Castellón, Castellón), López I (Hospital HM Montepríncipe y Sanchinarro, Madrid), López CA (Hospital General Universitario de Ciudad Real, Ciudad Real), Mancebo G (Hospital del Mar, Barcelona), Marcos J (Hospital General Universitario de Alicante, Alicante), Marino M (Hospital Universitario de Salamanca, Salamanca), Martí L (Hospital Universitario Bellvitge, Barcelona), Martínez M (Hospital Virgen de la Luz, Almería), Martínez MC (Hospital Son Llatzer, Palma de Mallorca), Melero LM (Hospital Virgen del Rocío, Sevilla), Minig L (IMED Hospitales, Valencia), Montesinos M (Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe, Valencia), Moral R (Hospital Poniente, Almería), Morales S (Hospital Universitario Infanta Leonor, Madrid), Negredo I (Hospital Miguel Servet, Zaragoza), Nieto A (Hospital Virgen de la Arrixaca, Murcia), Níguez I (Hospital Virgen de la Arrixaca, Murcia), Ribot L (Hospital Universitario Parc Tauli, Barcelona), Rosado C (Hospital de Mataró, Barcelona), Sancho V (Hospital Universitario de Salamanca, Salamanca), Tetilla V (Hospital General de Segovia, Segovia), Torres MC (Hospital del Perpetuo Socorro, Badajoz), Valencia I (Hospital Universitario Puerto Real, Cádiz), Veiga A (Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madrid), Vidal R (Complejo Hospitalario de Pontevedra, Pontevedra), Vilches JC (Hospital Quirón Málaga, Málaga).

References

- Orr, B.; Edwards, R.P. Diagnosis and Treatment of Ovarian Cancer. Hematol. Clin. North Am. 2018, 32, 943–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bercow, A.; Stewart, T.; Bregar, A.J.; Gockley, A.; Mazina, V.; Rauh-Hain, J.A.; Melamed, A. Utilization of Primary Cytoreductive Surgery for Advanced-Stage Ovarian Cancer. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2439893–e2439893, 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.39893. Erratum in: JAMA Netw Open. 2024, 7, e2456651. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.56651. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hacker, N.F.; Rao, A. Surgery for advanced epithelial ovarian cancer. Best Pr. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2016, 41, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dauplat, J.; Pomel, C.; Scherer, C.; Le Bouëdec, G. Cytoreductive surgery for advanced stages of ovarian cancer. Semin. Surg. Oncol. 2000, 19, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroki, L.; Guntupalli, S.R. Treatment of epithelial ovarian cancer. BMJ 2020, 371, m3773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova, J.; Cunha, J.F. Right upper quadrant cytoreductive procedures and cardiophrenic lymph node resection in primary debulkig surgery for ovarian cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. Rep. 2021, 36, 100781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandraklakis, A.; Mitsopoulos, V.; Biliatis, I. En-block cytoreduction for advanced ovarian cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. Rep. 2023, 47, 101170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardenas-Goicoechea, J.; Wang, Y.; McGorray, S.; Saleem, M.D.; Mamani, S.L.C.; Pomputius, A.F.; Markham, M.-J.; Castagno, J.C. Minimally invasive interval cytoreductive surgery in ovarian cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Robot. Surg. 2018, 13, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuss, A.; du Bois, A.; Harter, P.; Fotopoulou, C.; Sehouli, J.; Aletti, G.; Guyon, F.; Greggi, S.; Mosgaard, B.J.; Reinthaller, A.; et al. TRUST: Trial of Radical Upfront Surgical Therapy in advanced ovarian cancer (ENGOT ov33/AGO-OVAR OP7). Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2019, 29, 1327–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Kim, S.W.; Paek, J.; Lee, S.H.; Yim, G.W.; Kim, J.W.; Kim, Y.T.; Nam, E.J. Comparisons of Surgical Outcomes, Complications, and Costs Between Laparotomy and Laparoscopy in Early-Stage Ovarian Cancer. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2011, 21, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.K.; Kim, D.Y.; Cho, A.; Choi, J.-Y.; Park, J.-Y.; Kim, Y.-M. Role of minimally invasive surgery in early ovarian cancer. Gland. Surg. 2021, 10, 1252–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallotta, V.; Ghezzi, F.; Vizza, E.; Chiantera, V.; Ceccaroni, M.; Franchi, M.; Fagotti, A.; Ercoli, A.; Fanfani, F.; Parrino, C.; et al. Laparoscopic staging of apparent early stage ovarian cancer: Results of a large, retrospective, multi-institutional series. Gynecol. Oncol. 2014, 135, 428–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, N.G.; Moreno, C.S.; Teixeira, N.; Lloret, P.E.; Guibourg, R.L.; Negre, R.R. Comparison of Laparoscopy and Laparotomy in the Management of Early-stage Ovarian Cancer. Gynecol. Minim. Invasive Ther. 2023, 12, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Gao, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yu, J.; Zhang, T. Comparison of efficacy of robotic surgery, laparoscopy, and laparotomy in the treatment of ovarian cancer: a meta-analysis. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2019, 17, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melamed, A.; Rauh-Hain, J.A.; Gockley, A.A.; Nitecki, R.; Ramirez, P.T.; Hershman, D.L.; Keating, N.; Wright, J.D. Association Between Overall Survival and the Tendency for Cancer Programs to Administer Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy for Patients With Advanced Ovarian Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2021, 7, 1782–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagotti, A.; Alletti, S.G.; Corrado, G.; Cola, E.; Vizza, E.; Vieira, M.; E Andrade, C.; Tsunoda, A.; Favero, G.; Zapardiel, I.; et al. The INTERNATIONAL MISSION study: minimally invasive surgery in ovarian neoplasms after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2019, 29, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.; Drury, L.; Crane, E.K.; Anderson, W.E.; Tait, D.L.; Higgins, R.V.; Naumann, R.W. When Less Is More: Minimally Invasive Surgery Compared with Laparotomy for Interval Debulking After Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Women with Advanced Ovarian Cancer. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2019, 26, 902–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbajal-Mamani, S.L.; Schweer, D.; Markham, M.J.; Esnakula, A.K.; Grajo, J.R.; Castagno, J.C.; Cardenas-Goicoechea, J. Robotic-assisted interval cytoreductive surgery in ovarian cancer: a feasibility study. Obstet. Gynecol. Sci. 2020, 63, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch, L.; Chi, D.S. An overview of the current debate between using minimally invasive surgery versus laparotomy for interval cytoreductive surgery in epithelial ovarian cancer. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2023, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alletti, S.G.; Capozzi, V.A.; Rosati, A.; De Blasis, I.; Cianci, S.; Vizzielli, G.; Uccella, S.; Gallotta, V.; Fanfani, F.; Fagotti, A.; et al. Laparoscopy vs. laparotomy for advanced ovarian cancer: a systematic review of the literature. Minerva Medica 2019, 110, 341–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoi, A.; Machida, H.; Shimada, M.; Matsuo, K.; Shigeta, S.; Furukawa, S.; Nishikawa, N.; Nomura, H.; Hori, K.; Tokunaga, H.; et al. Efficacy and safety of minimally invasive surgery versus open laparotomy for epithelial ovarian cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gynecol. Oncol. 2024, 190, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, E.S.; Wakabayashi, M. Indications for Minimally Invasive Surgery for Ovarian Cancer. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2011, 9, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghirardi, V.; De Felice, F.; Rosati, A.; Ergasti, R.; Alletti, S.G.; Mascilini, F.; Scambia, G.; Fagotti, A. A Laparoscopic Adjusted Model Able to Predict the Risk of Intraoperative Capsule Rupture in Early-stage Ovarian Cancer: Laparoscopic Ovarian Cancer Spillage Score (LOChneSS Study). J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2022, 29, 961–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronsini, C.; Pasanisi, F.; Molitierno, R.; Iavarone, I.; Vastarella, M.G.; De Franciscis, P.; Conte, C. Minimally Invasive Staging of Early-Stage Epithelial Ovarian Cancer versus Open Surgery in Terms of Feasibility and Safety: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Guo, L.; Wang, B. The Pathogenesis and Prevention of Port-Site Metastasis in Gynecologic Oncology. Cancer Manag. Res. 2020, ume 12, 9655–9663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, I.; Chon, H.S.; Apte, S.M. The Role of Surgery in the Management of Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. Cancer Control. 2011, 18, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, D.A.; Ramirez, P.T. Role of Minimally Invasive Surgery in Staging of Ovarian Cancer. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2011, 12, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psomiadou, V.; Prodromidou, A.; Fotiou, A.; Lekka, S.; Iavazzo, C. Robotic interval debulking surgery for advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: current challenge or future direction? A systematic review. J. Robot. Surg. 2020, 15, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong D.K, Alvarez R.D, Backes F.J, Bakkum-Gamez J.N, Barroilhet L, Behbakht K et al. NCCN Guidelines® Insights: Ovarian Cancer, Version 3.2022. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2022, 20, 972–980.

- Minig, L.; Iserte, P.P.; Zorrero, C.; Zanagnolo, V. Robotic Surgery in Women With Ovarian Cancer: Surgical Technique and Evidence of Clinical Outcomes. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2015, 23, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniele, A.; Rosso, R.; Ceccaroni, M.; Roviglione, G.; D’ancona, G.; Peano, E.; Clignon, V.; Calandra, V.; Puppo, A. Laparoscopic Treatment of Bulky Nodes in Primary and Recurrent Ovarian Cancer: Surgical Technique and Outcomes from Two Specialized Italian Centers. Cancers 2024, 16, 1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallotta, V.; Jeong, S.Y.; Conte, C.; Trozzi, R.; Cappuccio, S.; Moroni, R.; Ferrandina, G.; Scambia, G.; Kim, T.-J.; Fagotti, A. Minimally invasive surgical staging for early stage ovarian cancer: A long-term follow up. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. (EJSO) 2021, 47, 1698–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cianci, S.; Capozzi, V.A.; Rosati, A.; Rumolo, V.; Corrado, G.; Uccella, S.; Alletti, S.G.; Riccò, M.; Fagotti, A.; Scambia, G.; et al. Different Surgical Approaches for Early-Stage Ovarian Cancer Staging. A Large Monocentric Experience. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 880681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghirardi, V.; De Felice, F.; Rosati, A.; Ergasti, R.; Alletti, S.G.; Mascilini, F.; Scambia, G.; Fagotti, A. A Laparoscopic Adjusted Model Able to Predict the Risk of Intraoperative Capsule Rupture in Early-stage Ovarian Cancer: Laparoscopic Ovarian Cancer Spillage Score (LOChneSS Study). J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2022, 29, 961–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Generali, M.; Annunziata, G.; Pirillo, D.; D’ippolito, G.; Ciarlini, G.; Aguzzoli, L.; Mandato, V.D. The role of minimally invasive surgery in epithelial ovarian cancer treatment: a narrative review. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1196496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dioun, S.; Chen, L.; Melamed, A.; Gockley, A.; Clair, C.M.S.; Hou, J.Y.; Tergas, A.I.; Khoury-Collado, F.; Elkin, E.; Accordino, M.; et al. Minimally invasive surgery for suspected early-stage ovarian cancer; a cost-effectiveness study. BJOG: Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2021, 129, 777–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Bois, A.; Reuss, A.; Pujade-Lauraine, E.; Harter, P.; Ray-Coquard, I.; Pfisterer, J. Role of surgical outcome as prognostic factor in advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: A combined exploratory analysis of 3 prospectively randomized phase 3 multicenter trials: by the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynaekologische Onkologie Studiengruppe Ovarialkarzinom (AGO-OVAR) and the Groupe d’Investigateurs Nationaux Pour les Etudes des Cancers de l’Ovaire (GINECO. Cancer 2009, 115, 1234–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitecki, R.; Rauh-Hain, J.A.; Melamed, A.; Scambia, G.; Pareja, R.; Coleman, R.L.; Ramirez, P.T.; Fagotti, A. Laparoscopic cytoreduction After Neoadjuvant ChEmotherapy (LANCE). Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2020, 30, 1450–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, K.-J.; Kim, N.K.; Song, J.-Y.; Choi, M.C.; Lee, S.W.; Lee, K.H.; Kim, M.K.; Kang, S.; Choi, C.H.; Lee, J.-W.; et al. From the Beginning of the Korean Gynecologic Oncology Group to the Present and Next Steps. Cancers 2024, 16, 3422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcetta, F.S.; A Lawrie, T.; Medeiros, L.R.; da Rosa, M.I.; I Edelweiss, M.; Stein, A.T.; Zelmanowicz, A.; Moraes, A.B.; Zanini, R.R.; Rosa, D.D.; et al. Laparoscopy versus laparotomy for FIGO stage I ovarian cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 2022, CD005344–CD005344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, N.; Sessa, C.; Du Bois, A.; Ledermann, J.; McCluggage, W.G.; McNeish, I.; Morice, P.; Pignata, S.; Ray-Coquard, I.; Vergote, I.; et al. ESMO–ESGO consensus conference recommendations on ovarian cancer: pathology and molecular biology, early and advanced stages, borderline tumours and recurrent disease. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 672–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).