Submitted:

01 May 2025

Posted:

05 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

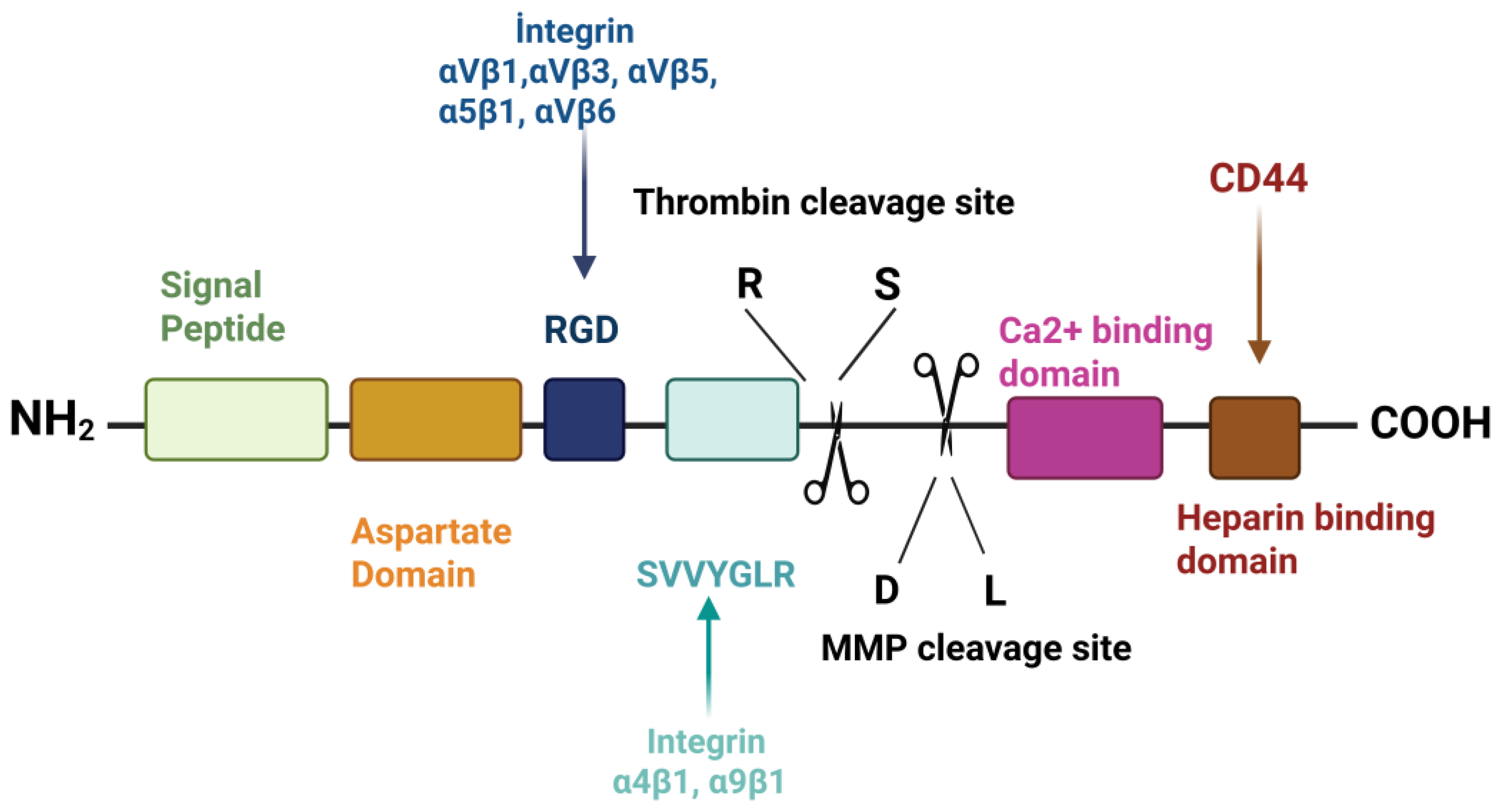

2. Structure and Chemical Properties of Osteopontin

2.1. Biosynthesis of Osteopontin

3. Effects of Environmental Conditions and Genetic Factors on OPN Levels

4. Biological Functions of Osteopontin

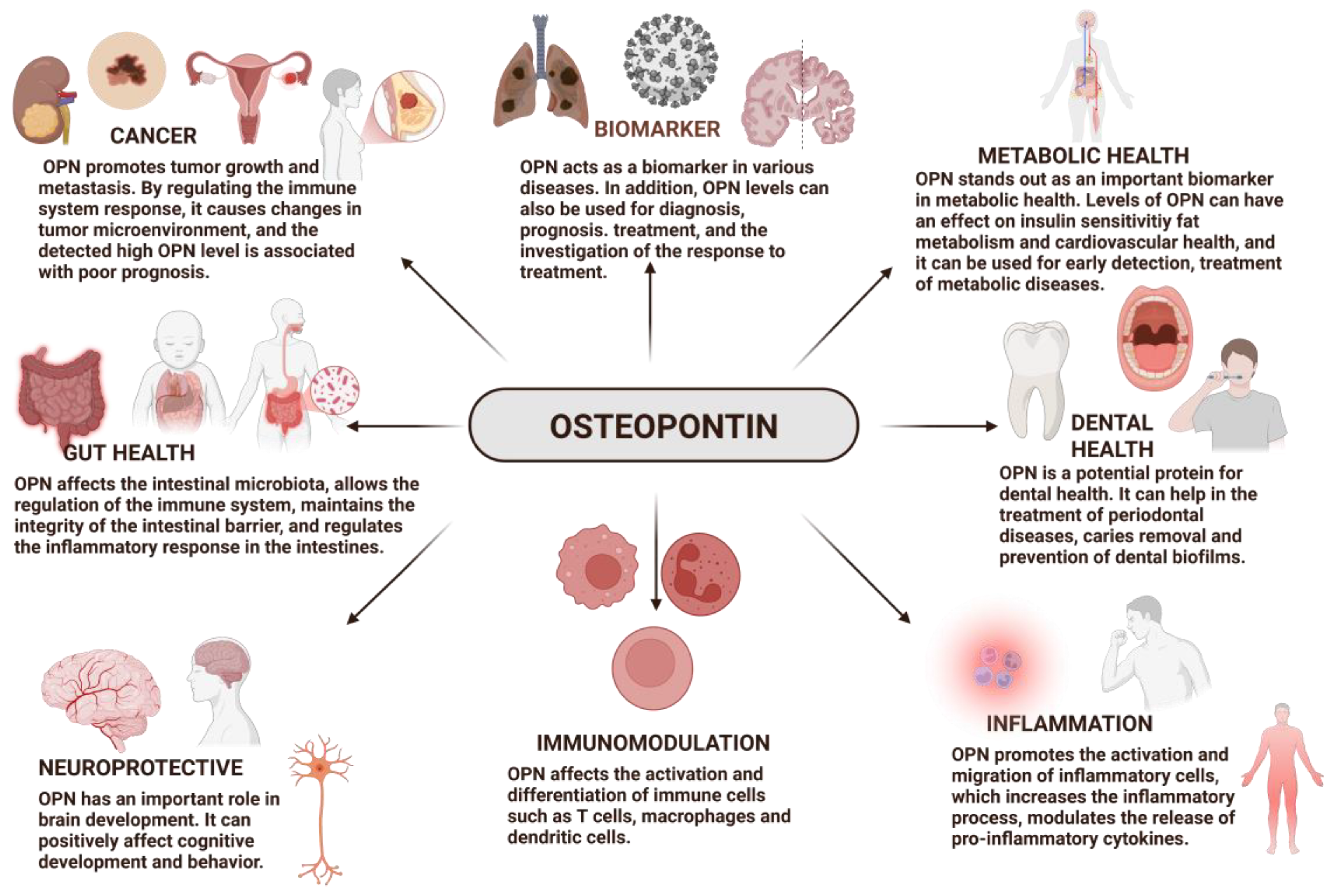

4.1. Osteopontin as a Biomarker

4.2. Osteopontin and Cancer

4.3. Osteopontin and Gut Health

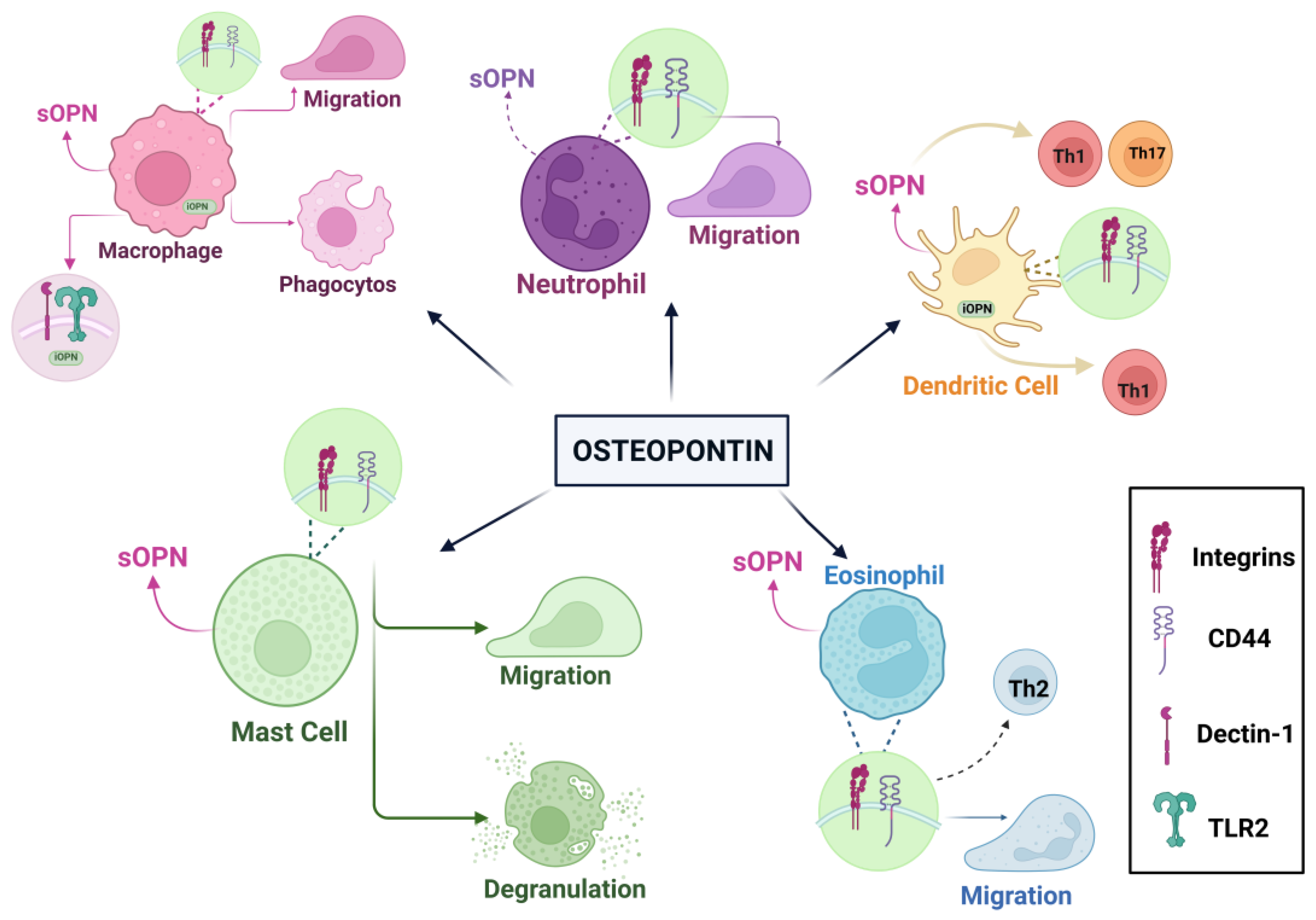

4.4. Osteopontin and Immunological Effects

4.5. Dental Health

4.6. Osteopontin and Brain development- Cognitive Function

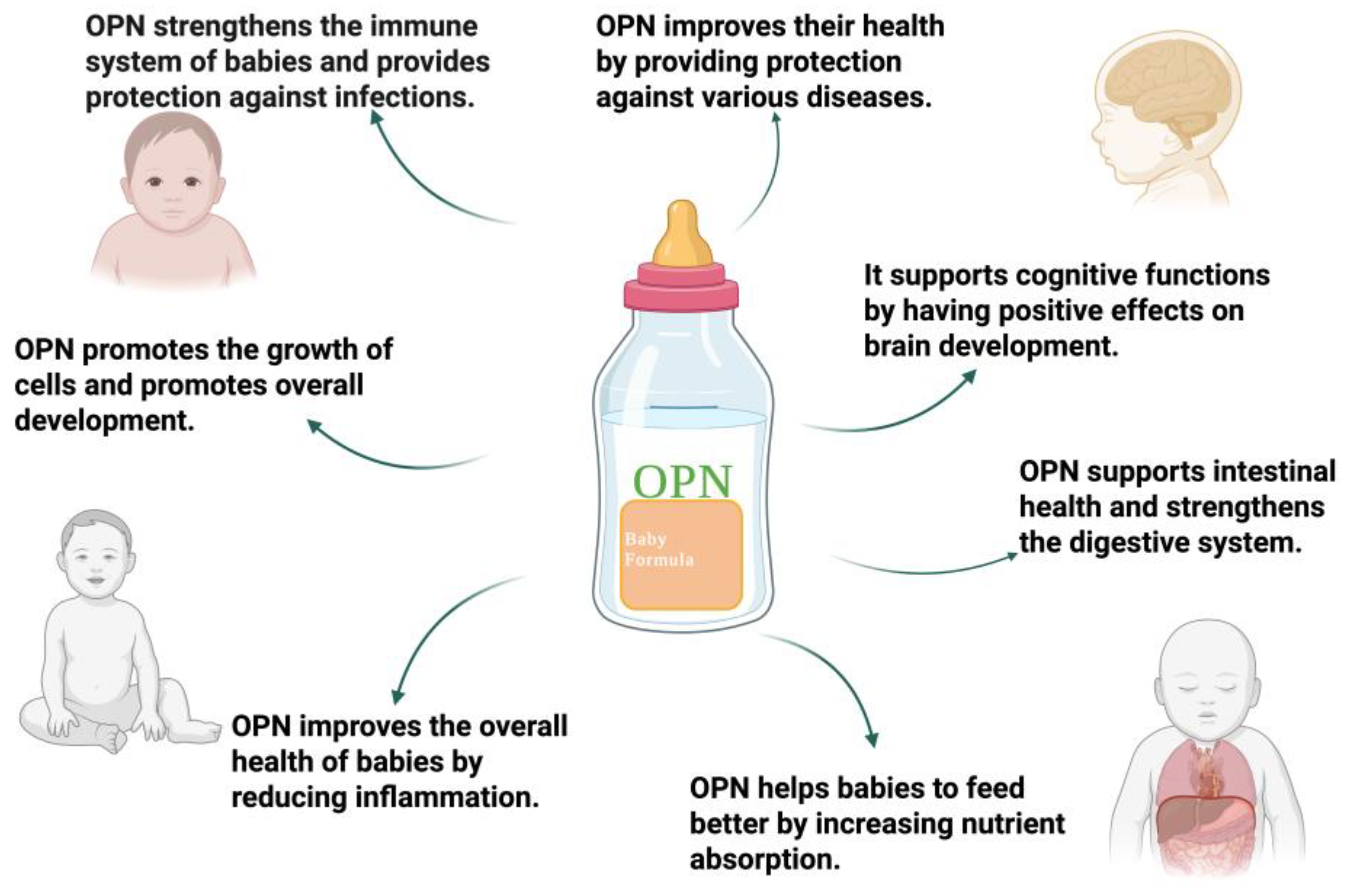

5. Nutritional Potential of Osteopontin

6. Conclusions and Future Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kläning, E.; Christensen, B.; Sørensen, E.S.; Vorup-Jensen, T.; Jensen, J.K. Osteopontin Binds Multiple Calcium Ions with High Affinity and Independently of Phosphorylation Status. Bone 2014, 66, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senger, D.F.; Wirth, D.F.; Hynes, R. 0 Transformed Mammalian Cells Secrete Specific Proteins and Phosphoproteins. Cell 1979, 16, 885–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franzitn, A.; Heinegard, D. Isolation and Characterization of Two Sialoproteins Present Only in Bone Calcified Matrix. Biochem. J 1985, 232, 715–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oldberg, A.; Franzfn, A.; Heinegard, D. Cloning and Sequence Analysis of Rat Bone Sialoprotein (Osteopontin) CDNA Reveals an Arg-Gly-Asp Cell-Binding Sequence (Cell Adhesion/Bone Matrix Proteins/Glycosylation). Biochemistry 1986, 83, 8819–8823. [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen, E.S.; Christensen, B. Milk Osteopontin and Human Health. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wrana, J.L.; Zhang, Q.; Sodek, J. Nucleic Acids Research Full Length CDNA Sequence of Porcine Secreted Phosphoprotein-I (SPP-I, Osteopontin). 17, 1989.

- Craig, A.M.; Denhardt, D.T. The Murine Gene Encoding Secreted Phosphoprotein 1 (Osteopontin): Promoter Structure, Activity, and Induction in Vivo by Estrogen and Progesterone (Promoter Analysis; Gene Structure; Bone Sialoprotein; Transformation-Associated Phosphoprotein; Early T-Lymphocyte Activation 1; Tumor Promoter Induction). Gene 1991, 100, 163–171. [Google Scholar]

- Patarca, R.; Freeman, G.J.; Singh, R.P.; Wei, F.Y.; Durfee, T.; Blattner, F.; Regnier, D.C.; Kozak, C.A.; Mock, B.A.; Morse, H.C.; et al. Structural and Functional Studies of the Early T Lymphocyte Activation 1 (Eta-1) Gene. Definition of a Novel T Cell-Dependent Response Associated with Genetic Resistance to Bacterial Infection. Journal of Experimental Medicine 1989, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, A.M.; Nemir, M.; Mukherjee, B.B.; Chambers, A.F.; Denhardt, D.T. Identification of the Major Phosphoprotein Secreted by Many Rodent Cell Lines as 2AR/Osteopontin: Enhanced Expression in H-RAS-Transformed 3T3 Cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1988, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Q.; Ouyang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yao, S.; Chen, X.; Hu, Z. Osteopontin: A Novel Therapeutic Target for Respiratory Diseases. Lung 2024, 202, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, N.; Raineri, D.; Cappellano, G.; Boggio, E.; Favero, F.; Soluri, M.F.; Dianzani, C.; Comi, C.; Dianzani, U.; Chiocchetti, A. Osteopontin Bridging Innate and Adaptive Immunity in Autoimmune Diseases. J Immunol Res 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wai, P.Y.; Kuo, P.C. The Role of Osteopontin in Tumor Metastasis. Journal of Surgical Research 2004, 121, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimodaira, T.; Matsuda, K.; Uchibori, T.; Sugano, M.; Uehara, T.; Honda, T. Upregulation of Osteopontin Expression via the Interaction of Macrophages and Fibroblasts under IL-1b Stimulation. Cytokine 2018, 110, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attur, M.G.; Dave, M.N.; Stuchin, S.; Kowalski, A.J.; Steiner, G.; Abramson, S.B.; Denhardt, D.T.; Amin, A.R. Osteopontin: An Intrinsic Inhibitor of Inflammation in Cartilage. Arthritis Rheum 2001, 44, 578–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.-M.; Wilson, P.D.; Laskin, J.D.; Denmardt, D.T. Age and Development-Related Changes in Osteopontin and Nitric Oxide Synthase MRNA Levels in Human Kidney Proximal Tubule Epithelial Cells: Contrasting Responses to Hypoxia and Reoxygenation. J Cell Physiol 1994, 160, 6148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, S.M.; Lopez, C.A.; Heck, D.E.; Gardner, C.R.; Laskin, D.L.; Laskin, J.D.; Denhardt, D.T. Tm JOURNAL OF B I O ~ I C A L C m m y Osteopontin Inhibits Induction of Nitric Oxide Synthase Gene Expression by Inflammatory Mediators in Mouse Kidney Epithelial Cells*. 1994, 269, 711–715.

- Scott, J.A.; Lynn Weir, M.; Wilson, S.M.; Xuan, J.W.; Chambers, A.F.; Mccormack, D.G.; Burton, A.C.; Weir, M.L. Osteopontin Inhibits Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase Activity in Rat Vascular Tissue. 1998.

- Denhardt, D.T.; Guo, X. Osteopontin: A Protein with Diverse Functions. The FASEB Journal 1993, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denhardt, D.T.; Noda, M. Osteopontin Expression and Function: Role in Bone Remodeling. J Cell Biochem 1998, 72, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Regan, A.; Berman, J.S. Osteopontin: A Key Cytokine in Cell-Mediated and Granulomatous Inflammation. Int J Exp Pathol 2000, 81, 373–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, G.F. The Metastasis Gene Osteopontin: A Candidate Target for Cancer Therapy.

- Tenen, D.G.; Senger, D.R.; Perruzzi, C.A.; Gracey, C.F.; Papadopoulos, A. Secreted Phosphoproteins Associated with Neoplastic Transformation: Close Homology with Plasma Proteins Cleaved during Blood Coagulation. Cancer Res 1988, 48. [Google Scholar]

- Senger, D.R.; Perruzzi, C.A.; Papadopoulos, A.; Tenen, D.G. Purification of a Human Milk Protein Closely Similar to Tumor-Secreted Phosphoproteins and Osteopontin. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)/Protein Structure and Molecular 1989, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista, D.S.; Denstedt, J.; Chambers, A.F.; Harris, J.F. Low-Molecular-Weight Variants of Osteopontin Generated by Serine Proteinases in Urine of Patients with Kidney Stones. J Cell Biochem 1996, 61, 402–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorman, H.R.; Poschel, D.; Klement, J.D.; Lu, C.; Redd, P.S.; Liu, K. Osteopontin: A Key Regulator of Tumor Progression and Immunomodulation. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toyonaga, T.; Nakase, H.; Ueno, S.; Matsuura, M.; Yoshino, T.; Honzawa, Y.; Itou, A.; Namba, K.; Minami, N.; Yamada, S.; et al. Osteopontin Deficiency Accelerates Spontaneous Colitis in Mice with Disrupted Gut Microbiota and Macrophage Phagocytic Activity. PLoS One 2015, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chunder, R.; Schropp, V.; Marzin, M.; Amor, S.; Kuerten, S. A Dual Role of Osteopontin in Modifying B Cell Responses. Biomedicines 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schack, L.; Lange, A.; Kelsen, J.; Agnholt, J.; Christensen, B.; Petersen, T.E.; Sørensen, E.S. Considerable Variation in the Concentration of Osteopontin in Human Milk, Bovine Milk, and Infant Formulas. J Dairy Sci 2009, 92, 5378–5385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, C.E.; Kvistgaard, A.S.; Peerson, J.M.; Donovan, S.M.; Peng, Y.M.; Lönnerdal, B. Effects of Osteopontin-Enriched Formula on Lymphocyte Subsets in the First 6 Months of Life: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Pediatr Res 2017, 82, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iturbe-Fernández, D.; Pulito-Cueto, V.; Mora-Cuesta, V.M.; Remuzgo-Martínez, S.; Ferrer-Pargada, D.J.; Genre, F.; Alonso-Lecue, P.; López-Mejías, R.; Atienza-Mateo, B.; González-Gay, M.A.; et al. Osteopontin as a Biomarker in Interstitial Lung Diseases. Biomedicines 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, O.A.; Qasem, A.; Taha, G.; Amer, H. Evaluation of Osteopontin as a Potential Biomarker in Hepatocellular Carcinoma in a Sample of Egyptian Patients. Egyptian Journal of Cancer and Biomedical Research 2024, 8, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.; Lönnerdal, B. Evaluation of Bioactivities of Bovine Milk Osteopontin Using a Knockout Mouse Model. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2020, 71, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadoglou, N.P.E.; Khattab, E.; Velidakis, N.; Gkougkoudi, E. The Role of Osteopontin in Atherosclerosis and Its Clinical Manifestations (Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Diseases)—A Narrative Review. Biomedicines 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günaydın, S.; Özlü, T.; Özsu, S.S.; Örem, A. Role of Osteopontin and NGAL in Differential Diagnosis of Acute Exacerbations of COPD and Pneumonia. Medical Science and Discovery 2024, 11, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, A.G.; Eleftheriou, K.; Vlahakos, V.; Magkouta, S.F.; Riba, T.; Dede, K.; Siampani, R.; Kompogiorgas, S.; Polydora, E.; Papalampidou, A.; et al. High Plasma Osteopontin Levels Are Associated with Serious Post-Acute-COVID-19-Related Dyspnea. J Clin Med 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quesnel, M.J.; Labonté, A.; Picard, C.; Bowie, D.C.; Zetterberg, H.; Blennow, K.; Brinkmalm, A.; Villeneuve, S.; Poirier, J. Osteopontin: A Novel Marker of Pre-Symptomatic Sporadic Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimer’s and Dementia 2024. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Lu, Z.; Liu, F.; Lane, J.; Chen, J.; Fu, X.; Huang, Q.; Hu, R.; Zhang, B. Osteopontin Enhances the Probiotic Viability of Bifidobacteria in Pectin-Based Microencapsulation Subjected to in Vitro Infant Gastrointestinal Digestion. Food Hydrocoll 2024, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, M.F.; Sørensen, E.S.; Del Rey, Y.C.; Schlafer, S. Prevention of Initial Bacterial Attachment by Osteopontin and Other Bioactive Milk Proteins. Biomedicines 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurrohman, H.; Carter, L.; Barnes, N.; Zehra, S.; Singh, V.; Tao, J.; Marshall, S.J.; Marshall, G.W. The Role of Process-Directing Agents on Enamel Lesion Remineralization: Fluoride Boosters. Biomimetics 2022, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burling, H.S.S.B.H.J.A.G.G. Use of Osteopontin in Dental Formulations 2005.

- Joung, S.; Fil, J.E.; Heckmann, A.B.; Kvistgaard, A.S.; Dilger, R.N. Early-Life Supplementation of Bovine Milk Osteopontin Supports Neurodevelopment and Influences Exploratory Behavior. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Ma, Q.; Suzuki, H.; Hartman, R.; Tang, J.; Zhang, J.H. Osteopontin Reduced Hypoxia-Ischemia Neonatal Brain Injury by Suppression of Apoptosis in a Rat Pup Model. Stroke 2011, 42, 764–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Y.; Lu, F.; Li, P.; Jian, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhong, T.; Guo, Q.; Yang, Y. Osteopontin Promotes Angiogenesis in the Spinal Cord and Exerts a Protective Role Against Motor Function Impairment and Neuropathic Pain After Spinal Cord Injury. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2024, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodek, J.; Ganss, B.; McKee M., D. OSTEOPONTIN. Critical Reviews in Oral Biology & Medicine 2000, 11, 279–303. [Google Scholar]

- Icer, M.A.; Gezmen-Karadag, M. The Multiple Functions and Mechanisms of Osteopontin. Clin Biochem 2018, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, W.T. The Nature and Significance of Osteopontin. Connect Tissue Res 1989, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayless, K.J.; Davis, G.E. Identification of Dual A4β1 Integrin Binding Sites within a 38 Amino Acid Domain in the N-Terminal Thrombin Fragment of Human Osteopontin. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2001, 276, 13483–13489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Zhao, L.; Yang, Y.G.; Liu, W. The Role of Osteopontin in Tumor Progression Through Tumor-Associated Macrophages. Front Oncol 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Standal, T.; Borset, M.; Sundan, A. Role of Osteopontin in Adhesion, Migration, Cell Survival and Bone Remodeling. Exp Oncol 2004, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Yokosaki, Y.; Matsuura, N.; Sasaki, T.; Murakami, I.; Schneider, H.; Higashiyama, S.; Saitoh, Y.; Yamakido, M.; Taooka, Y.; Sheppard, D. The Integrin A9β1 Binds to a Novel Recognition Sequence (SVVYGLR) in the Thrombin-Cleaved Amino-Terminal Fragment of Osteopontin. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1999, 274, 36328–36334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, B.; Nielsen, M.S.; Haselmann, K.F.; Petersen, T.E.; Sørensen, E.S. Post-Translationally Modified Residues of Native Human Osteopontin Are Located in Clusters: Identification of 36 Phosphorylation and Five O-Glycosylation Sites and Their Biological Implications. Biochemical Journal 2005, 390, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tagliabracci, V.S.; Wiley, S.E.; Guo, X.; Kinch, L.N.; Durrant, E.; Wen, J.; Xiao, J.; Cui, J.; Nguyen, K.B.; Engel, J.L.; et al. A Single Kinase Generates the Majority of the Secreted Phosphoproteome. Cell 2015, 161, 1619–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothari, A.N.; Arffa, M.L.; Chang, V.; Blackwell, R.H.; Syn, W.K.; Zhang, J.; Mi, Z.; Kuo, P.C. Osteopontin—a Master Regulator of Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition. J Clin Med 2016, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Shou, P.; Zhang, L.; Xu, C.; Zheng, C.; Han, Y.; Li, W.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Shao, C.; et al. An Osteopontin-Integrin Interaction Plays a Critical Role in Directing Adipogenesis and Osteogenesis by Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Stem Cells 2014, 32, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, E.Y.H.; Xi, W.; Aggarwal, N.; Shinohara, M.L. Osteopontin (OPN)/SPP1: From Its Biochemistry to Biological Functions in the Innate Immune System and the Central Nervous System (CNS). Int Immunol 2023, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, G.F. The Phylogeny of Osteopontin—Analysis of the Protein Sequence. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, E.S.; Petersen, T.E.; Højrup, P. Posttranslational Modifications of Bovine Osteopontin: Identification of Twenty-eight Phosphorylation and Three O-glycosylation Sites. Protein Science 1995, 4, 2040–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazanecki, C.C.; Uzwiak, D.J.; Denhardt, D.T. Control of Osteopontin Signaling and Function by Post-Translational Phosphorylation and Protein Folding. J Cell Biochem 2007, 102, 912–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kon, S.; Ikesue, M.; Kimura, C.; Aoki, M.; Nakayama, Y.; Saito, Y.; Kurotaki, D.; Diao, H.; Matsui, Y.; Segawa, T.; et al. Syndecan-4 Protects against Osteopontin-Mediated Acute Hepatic Injury by Masking Functional Domains of Osteopontin. Journal of Experimental Medicine 2008, 205, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinohara, M.L.; Kim, H.-J.; Kim, J.-H.; Garcia, V.A.; Cantor, H. Alternative Translation of Osteopontin Generates Intracellular and Secreted Isoforms That Mediate Distinct Biological Activities in Dendritic Cells. 2008.

- Christensen, B.; Karlsen, N.J.; Jørgensen, S.D.S.; Jacobsen, L.N.; Ostenfeld, M.S.; Petersen, S. V.; Müllertz, A.; Sørensen, E.S. Milk Osteopontin Retains Integrin-Binding Activity after in Vitro Gastrointestinal Transit. J Dairy Sci 2020, 103, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schytte, G.N.; Christensen, B.; Bregenov, I.; Kjøge, K.; Scavenius, C.; Petersen, S. V.; Enghild, J.J.; Sørensen, E.S. FAM20C Phosphorylation of the RGDSVVYGLR Motif in Osteopontin Inhibits Interaction with the Avβ3 Integrin. J Cell Biochem 2020, 121, 4809–4818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Evidence for the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding. 1998.

- WHO Protecting, Promoting and Supporting Breast-Feeding: The Special Role of Maternity Services. A Joint WHO/UNICEF Statement. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1989; 2017;

- Aksan, A.; Erdal, I.; Yalcin, S.S.; Stein, J.; Samur, G. Osteopontin Levels in Human Milk Are Related to Maternal Nutrition and Infant Health and Growth. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bezirtzoglou, E.; Tsiotsias, A.; Welling, G.W. Microbiota Profile in Feces of Breast- and Formula-Fed Newborns by Using Fluorescence in Situ Hybridization (FISH). Anaerobe 2011, 17, 478–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fasano, A. Another Reason to Favor Exclusive Breastfeeding: Microbiome Resilience. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2018, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, L.Å.; Korotkova, M. The Role of Breastfeeding in Prevention of Neonatal Infection. Seminars in Neonatology 2002, 7, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Park, H.; Ha, E.; Hong, Y.C.; Ha, M.; Park, H.; Kim, B.N.; Lee, B.; Lee, S.J.; Lee, K.Y.; et al. Effect of Breastfeeding Duration on Cognitive Development in Infants: 3-Year Follow-up Study. J Korean Med Sci 2016, 31, 579–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demmelmair, H.; Prell, C.; Timby, N.; Lönnerdal, B. Benefits of Lactoferrin, Osteopontin and Milk Fat Globule Membranes for Infants. Nutrients 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruan, H.; Tang, Q.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Xiang, Y.; Geng, W.; Feng, Y.; Cai, W. The Levels of Osteopontin in Human Milk of Chinese Mothers and Its Associations with Maternal Body Composition. Food Science and Human Wellness 2022, 11, 1419–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.; Lönnerdal, B. Osteopontin in Human Milk and Infant Formula Affects Infant Plasma Osteopontin Concentrations. Pediatr Res 2019, 85, 502–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goonatilleke, E.; Huang, J.; Xu, G.; Wu, L.; Smilowitz, J.T.; German, J.B.; Lebrilla, C.B. Human Milk Proteins and Their Glycosylation Exhibit Quantitative Dynamic Variations during Lactation. Journal of Nutrition 2019, 149, 1317–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Zhao, A.; Lai, S.; Yuan, Q.; Jia, X.; Wang, P.; Zhang, Y. Longitudinal Changes in the Concentration of Major Human Milk Proteins in the First Six Months of Lactation and Their Effects on Infant Growth. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Yu, X.; Wang, Y.; Bai, S.; Lai, J.; Tong, X.; Xing, Y. Longitudinal Changes of Lactopontin (Milk Osteopontin) in Term and Preterm Human Milk. Front Nutr 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joung, K.E.; Christou, H.; Park, K.H.; Mantzoros, C.S. Cord Blood Levels of Osteopontin as a Phenotype Marker of Gestational Age and Neonatal Morbidities. Obesity 2014, 22, 1317–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, T.; Ueno, H.M.; Yamaide, F.; Nakano, T.; Shiko, Y.; Kawasaki, Y.; Mitsuishi, C.; Shimojo, N. Comparison of 30 Cytokines in Human Breast Milk between 1989 and 2013 in Japan. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Bartolomeo, M.; Pietrantonio, F.; Pellegrinelli, A.; Martinetti, A.; Mariani, L.; Daidone, M.G.; Bajetta, E.; Pelosi, G.; de Braud, F.; Floriani, I.; et al. Osteopontin, E-Cadherin, and β-Catenin Expression as Prognostic Biomarkers in Patients with Radically Resected Gastric Cancer. Gastric Cancer 2016, 19, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashiguchi, Y.; Tsuda, H.; Bandera, C.A.; Nishimura, S.; Inoue, T.; Kawamura, N.; Berkowitz, R.S.; Mok, S.C. Comparison of Osteopontin Expression in Endometrioid Endometrial Cancer and Ovarian Endometrioid Cancer. Medical Oncology 2006, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, G.; Elangovan, S. Investigating the Role of Osteopontin (OPN) in the Progression of Breast, Prostate, Renal and Skin Cancers. Biomedicines 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mack, P.C.; Redman, M.W.; Chansky, K.; Williamson, S.K.; Farneth, N.C.; Lara, P.N.; Franklin, W.A.; Le, Q.T.; Crowley, J.J.; Gandara, D.R. Lower Osteopontin Plasma Levels Are Associated with Superior Outcomes in Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Patients Receiving Platinum-Based Chemotherapy: SWOG Study S0003. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2008, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Song, Z.; Han, H.; Ge, X.; Desert, R.; Athavale, D.; Babu Komakula, S.S.; Magdaleno, F.; Chen, W.; Lantvit, D.; et al. Intestinal Osteopontin Protects From Alcohol-Induced Liver Injury by Preserving the Gut Microbiome and the Intestinal Barrier Function. CMGH 2022, 14, 813–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aasmul-Olsen, K.; Henriksen, N.L.; Nguyen, D.N.; Heckmann, A.B.; Thymann, T.; Sangild, P.T.; Bering, S.B. Milk Osteopontin for Gut, Immunity and Brain Development in Preterm Pigs. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Li, Q.; Du, M.; Mao, X. Bovine Milk Osteopontin Improved Intestinal Health of Pregnant Rats Fed a High-Fat Diet through Improving Bile Acid Metabolism. J Dairy Sci 2024, 107, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreres-Serafini, L.; Martín-Orúe, S.M.; Sadurní, M.; Jiménez, J.; Moreno-Muñoz, J.A.; Castillejos, L. Supplementing Infant Milk Formula with a Multi-Strain Synbiotic and Osteopontin Enhances Colonic Microbial Colonization and Modifies Jejunal Gene Expression in Lactating Piglets. Food Funct 2024, 15, 6536–6552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donovan, S.M.; Monaco, M.H.; Drnevich, J.; Kvistgaard, A.S.; Hernell, O.; Lönnerdal, B. Bovine Osteopontin Modifies the Intestinal Transcriptome of Formula-Fed Infant Rhesus Monkeys to Be More Similar to Those That Were Breastfed. Journal of Nutrition 2014, 144, 1910–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zeng, P.; Gong, L.; Zhang, X.; Ling, Z.; Bi, K.; Shi, F.; Wang, K.; Zhang, Q.; Jiang, J.; et al. Osteopontin Exacerbates High-Fat Diet-Induced Metabolic Disorders in a Microbiome-Dependent Manner. mBio 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layton, G.R.; Antoun, I.; Copperwheat, A.; Khan, Z.L.; Bhandari, S.S.; Somani, R.; Ng, A.; Zakkar, M. Osteopontin as a Biomarker for Coronary Artery Disease. Cells 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denhardt, D.T.; Noda, M.; O’Regan, A.W.; Pavlin, D.; Berman, J.S. Osteopontin as a Means to Cope with Environmental Insults: Regulation of Inflammation, Tissue Remodeling, and Cell Survival. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2001, 107, 1055–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furger, K.A.; Menon, R.K.; Tuck, A.B.; Bramwell, V.H.; Chambers, A.F. The Functional and Clinical Roles of Osteopontin in Cancer and Metastasis. Curr Mol Med 2001, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Alpana Kumari, D.K.V.K.G. Osteopontin in Cancer. In Advances in Clinical Chemistry; Elsevier, 2024; Vol. 118, pp. 87–110.

- Tilli, T.M.; Thuler, L.C.; Matos, A.R.; Coutinho-Camillo, C.M.; Soares, F.A.; da Silva, E.A.; Neves, A.F.; Goulart, L.R.; Gimba, E.R. Expression Analysis of Osteopontin MRNA Splice Variants in Prostate Cancer and Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia. Exp Mol Pathol 2012, 92, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gassler, N.; Autschbach, F.; Gauer, S.; Bohn, J.; Sido, B.; Otto, H.F.; Geiger, H.; Obermüller, N. Expression of Osteopontin (Eta-1) in Crohn Disease of the Terminal Ileum. Scand J Gastroenterol 2002, 37, 1286–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agnholt, J.; Kelsen, J.; Schack, L.; Hvas, C.L.; Dahlerup, J.F.; Sørensen, E.S. Osteopontin, a Protein with Cytokine-like Properties, Is Associated with Inflammation in Crohn’s Disease. Scand J Immunol 2007, 65, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, A.P.B.; Pollett, A.; Rittling, S.R.; Denhardt, D.T.; Sodek, J.; Zohar, R. Exacerbated Tissue Destruction in DSS-Induced Acute Colitis of OPN-Null Mice Is Associated with Downregulation of TNF-α Expression and Non-Programmed Cell Death. J Cell Physiol 2006, 208, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macneil, R.L.; Berry, J.; D’errico, J.; Strayhorn, C.; Piotrowski, B.; Somerman, M.J. Role of Two Mineral-Associated Adhesion Molecules, Osteopontin and Bone Sialoprotein, during Cementogenesis. Connect Tissue Res 1995, 33, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, M.D.; Nanci, A. Osteopontin at Mineralized Tissue Interfaces in Bone, Teeth, and Osseointegrated Implants: Ultrastructural Distribution and Implications for Mineralized Tissue Formation, Turnover, and Repair. Microsc Res Tech 1996, 33, 141–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Liu, X.; Zhong, Y. The Effect of Osteopontin on Microglia. Biomed Res Int 2017, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stampanoni Bassi, M.; Buttari, F.; Gilio, L.; Iezzi, E.; Galifi, G.; Carbone, F.; Micillo, T.; Dolcetti, E.; Azzolini, F.; Bruno, A.; et al. Osteopontin Is Associated with Multiple Sclerosis Relapses. Biomedicines 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiocchetti, A.; Comi, C.; Indelicato, M.; Castelli, L.; Mesturini, R.; Bensi, T.; Mazzarino, M.C.; Giordano, M.; D’Alfonso, S.; Momigliano-Richiardi, P.; et al. Osteopontin Gene Haplotypes Correlate with Multiple Sclerosis Development and Progression. J Neuroimmunol 2005, 163, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Zhou, M.; Dai, W.; Guo, W.; Qiu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Mo, M.; Ding, L.; Ye, P.; Wu, Y.; et al. Bone-Derived Factors as Potential Biomarkers for Parkinson’s Disease. Front Aging Neurosci 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirths, O.; Breyhan, H.; Marcello, A.; Cotel, M.C.; Brück, W.; Bayer, T.A. Inflammatory Changes Are Tightly Associated with Neurodegeneration in the Brain and Spinal Cord of the APP/PS1KI Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurobiol Aging 2010, 31, 747–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gehrmann, J.; Matsumoto, Y.; Kreutzberg, G.W. BRAIN RESEARCH REVIEWS Full-Length Review Microglia: Intrinsic Immuneffector Cell of the Brain. Brain Res Rev 1995, 20, 269–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Luo, X.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Luo, H.; Huang, Q.; Cheng, Y.; Xie, Z. Osteopontin as a Potential Therapeutic Target for Ischemic Stroke. Curr Drug Deliv 2017, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, R.; Prell, C.; Lönnerdal, B. Milk Osteopontin Promotes Brain Development by Up-Regulating Osteopontin in the Brain in Early Life. FASEB Journal 2019, 33, 1681–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosca, F.; Giannì, M.L. Human Milk: Composition and Health Benefits. Pediatria Medica e Chirurgica 2017, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, K.G.; Heinig, M.J.; Nommsen-Rivers, L.A. Differences in Morbidity between Breast-Fed and Formula-Fed Infants. 1995.

- Chatterton, D.E.W.; Rasmussen, J.T.; Heegaard, C.W.; Sørensen, E.S.; Petersen, T.E. In Vitro Digestion of Novel Milk Protein Ingredients for Use in Infant Formulas: Research on Biological Functions. In Proceedings of the Trends in Food Science and Technology; July 2004; Vol. 15, pp. 373–383.

- Ge, X.; Lu, Y.; Leung, T.-M.; Sørensen, E.S.; Nieto, N. Milk Osteopontin, a Nutritional Approach to Prevent Alcohol-Induced Liver Injury. American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology 2013, 304, 929–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvistgaard, A.S.; Matulka, R.A.; Dolan, L.C.; Ramanujam, K.S. Pre-Clinical in Vitro and in Vivo Safety Evaluation of Bovine Whey Derived Osteopontin, Lacprodan® OPN-10. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2014, 73, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Function | Dose | Effect | Study design | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroprotective | The OPN-supplemented formula was designed to use 250 mg/L OPN. | Dietary supplementation of bmOPN enhanced the relative volume of several brain regions and altered behaviors in the novel object recognition task. | In vivo | [41] |

| Neuroprotective | OPN (0.03 μg or 0.1 μg) was administered intracerebroventricularly at 1-hour post-HI. | Exogenous OPN reduced infarct volume and augmented neurological outcomes 7 weeks after HI injury. OPN-induced neuroprotection was inhibited by an integrin antagonist. | In vivo | [42] |

| Neuroprotective | - | The possible advantages of OPN increase in improving locomotor function and alleviating neuropathic pain subsequent to a spinal cord injury. | In vivo | [43] |

| Gut Health | - | It was found that OPN deficiency worsens alcohol-related disease (ALD). In addition, it has been shown that increasing the amount of OPN in intestinal epithelial cells may be beneficial for maintaining the intestinal microbiome and protecting intestinal barrier function and to destroy ALD. | In vivo | [82] |

| Gut, Immunity and Brain Development | 16 premature pigs fed diets with 46 mg/(kg.g) of OPN added. | It has been found that pigs fed with OPN supplementation have greater villus-crypt depth and a higher number of monocytes and lymphocytes. The T-maze test turned out to be similar in all groups, so their cognitive development is similar. In addition, improvements in intestinal structure and immunity have been observed thanks to OPN supplementation. | In vivo | [83] |

| Gut Health | BmOPN was enhanced at a dose of 6 mg/kg body weight. | It has been noticed that use of OPN supplements by pregnant women during pregnancy prevents colon inflammation and increases the function of the intestinal barrier. The intestinal population has been regulated by SCFA production. Bovine OPN provides support for the secretion of bile acid. | In vivo | [84] |

| Gut health and Immune function | 0.436 g/L OPN was added to the milk formulation. | It has been proven to improve digestion, intestinal microbiota, and the newborn immune system in piglets administered OPN. Synbiotic tablets enhance healthy bacteria breeds in piglets' intestines. Supports reducing hazardous genera. It also reduced diarrhea in OPN or synbiotic-fed piglets. Most notably, an increase in SCFA in offspring feeding OPN and the synbiotic formula has reduced ammonia, which prevents pathogen growth. | In vivo | [85] |

| Gut Health | Formula fed supplemented with 25 mg/L bovine OPN. | Newborn rhesus monkeys fed breast milk or OPN-supplemented bovine milk grow similarly. Different nutritional groups express genes differently. Additionally, monkeys administered bovine OPN have similar gene expression to those fed breast milk. OPN may affect newborn rhesus monkey intestines. | In vivo | [86] |

| Biomarker and Bioactivity | 12µg/g OPN was used as a supplement every morning. | BmOPN has been found to improve the growth of the small intestine, inhibit lipopolysaccharide-induce TNF-α secretion, increase the amount of brain myelination and support cognitive development. | In vivo | [32] |

| Biomarker | - | It has been found that OPN is associated with atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases (ASCVD) and vascular calcifications (VC) and plays a pro-inflammatory role. It is known that OPN has different effects on various diseases. In addition, OPN level may be a potential biomarker in patients with coronary artery disease. | In vitro and In Vivo | [33] |

| Biomarker | - | It has been evaluated that the examination of OPN levels is important in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and pneumonia and that OPN may show a potential biomarker property. | In vivo | [34] |

| Biomarker | - | It was noticed that patients hospitalized due to COVID-19 had increased amounts of OPN in their circulation, and these patients showed severe symptoms. Thanks to this finding, it has been thought that OPN may be a biomarker. | In vitro | [35] |

| Biomarker | - | This study examined the diagnosis and prognosis of interstitial lung disorders (ILDs) using OPN levels. According to the study, ILD patients had 0.00105 mg/L OPN, while healthy people had 0.00081 mg/L. OPN levels are inversely linked to required vital capacity and high in ILD patients who died or had lung transplants. Based on these findings, increased OPN levels may help identify ILD patients. | In vivo | [36] |

| Biomarker | - | This study examined the diagnosis and prognosis of interstitial lung disorders (ILDs) using OPN levels. According to the study, ILD patients had 0.00105 mg/L OPN, while healthy people had 0.00081 mg/L. OPN levels are inversely linked to required vital capacity and high in ILD patients who died or had lung transplants. Based on these findings, increased OPN levels may help identify ILD patients. | In vivo | [30] |

| Biomarker | - | In Egypt, biomarker was considered to help diagnose hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The study examined a potential biomarker of OPN concentration in HCV patients. According to the study, OPN is more effective and sensitive than other markers. This suggests that OPN can be employed as a biomarker for early illness diagnosis. | In vivo | [31] |

| Dental Health | - | OPN is effective process-directing agents utilized in the PILP process to stabilize and convey mineral ions and the regulate remineralization had the potential to boost the performance of fluoride. | In vitro | [39] |

| Dental Health | Although 46 µM OPN was used in previous studies, the amount of OPN used in this study is 50 µM, as the desired optimal effect was not observed. | Different milk proteins have been researched to inhibit bacteria adhesion to saliva-coated surfaces. OPN prevents adhesion best among milk proteins. These proteins may improve oral health and prevent dental biofilm. | In vitro | [38] |

| Dental Health | The amount of OPN determined for use in the study is in the range of 100 mg/kg to 1000 mg/kg. But the amount of OPN that is considered suitable for use the most is approximately 350 mg/kg. | It has been found that OPN could bind to hydroxyapatite surfaces, as well as the ability to prevent bacteria from adhering to the tooth surface. | In vitro | [40] |

| Immunomodulation | - | A study on OPN's role in inflammatory intestinal inflammation indicated that colitis progressed quicker in OPN/IL-10 DKO mice than in IL-10 KO animals. Thus, OPN deficiency has advanced colitis. OPN expression is also elevated in IL-10 KO mouse epithelial cells. In OPN/IL-10 DKO mice, Clostridium subset XIVa was less abundant and cluster XVIII was more abundant. | In vivo | [26] |

| Immunomodulation | 2µg/well (1µg/mL) recombinant OPN was added to B cells. | OPN was detected in MS brain tissue B cell clusters and reduces B cells by diminishing CD80 and CD86 helper stimulus molecule expression. OPN also increases B cell clustering, which is linked to persistent neuroinflammation. OPN boosts IL-6 and autoantibodies. IL-6 was down-regulated and IL-10 up-regulated in B cells treated with human recombinant OPN (rOPN). | In vitro | [27] |

| Immunomodulation | - | OPN plasma from 3-month-old babies' umbilical cords is 7-10 times higher than normal. Infant formula's low OPN concentration is insufficient for infants' intestinal immune systems. For this reason, newborn cells are unlikely to express enough cytokines. | In vitro | [28] |

| Immunomodulation | Milk formulas with 65 mg OPN/L or 130 mg OPN/L added were used. | The amount of T cells and monocytes in the circulations of infants fed with (formula 130) increased. It is also thought to have a possible role in the development and progress of immunity in infants. | In vivo | [29] |

| Cancer | - | Cancer can result from high OPN levels. It also promotes tumor growth and metastasis, which can spread cancer. Gastric cancer patients' survival can be predicted by OPN levels. | In vitro | [78] |

| Cancer | - | In particular, the OPN levels of EEC (endometrioid endometrial cancer) and OEC (ovarian endometrioid cancer) cancer types are similar to each other. It was found that the OPN level was higher in advanced tumors. | In vitro | [79] |

| Cancer | - | It was found that OPN expression was high in breast, prostate, kidney and skin cancers. It was noticed that the amount of OPN was even higher in advanced kidney and skin cancers than in other types of cancer. When treatment targets for these types of cancer were applied, the level of OPN decreased. | In vitro | [80] |

| Cancer | - | Patients with strong OPN-expression had a shorter lifespan. OPN levels before chemotherapy are linked to survival, disease development after treatment, and treatment responses in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients. | In vivo | [81] |

| Metabolic Health | - | Identify OPN's role in HFD-induced lipid deposition. OPN-deficient (KO) mice may tolerate HFD-induced lipid accumulation and metabolic circumstances. HFD-fed mice's intestinal lipid and fatty acid metabolism is actively regulated by OPN. By altering the gut flora, OPN deficiency may prevent HFD-induced dyslipidemia. | In vitro – in vivo | [87] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).