1. Introduction

Virtual reality (VR) is the name given to the technology that allows a user to simulate a situation or experience of interest, using a VR headset, within an interactive but computer-generated environment [

1,

2,

3]. It is used in many areas of healthcare, in a variety of applications from medical education to rehabilitation, patient treatments, medical marketing, and educating people about a disease or medical condition or process both in the adult and pediatric field [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11].

In recent years, a multimodal approach to pain management has been established [

12,

13], proposing a deep integration of pharmaceutical and non-pharmacological approaches. Among them, one of the most promising technologies for trauma and distressing medical procedures is immersive virtual reality [

14]. The effectiveness of VR distraction treatment in reducing acute pain, anxiety, and distress during invasive medical procedures has been the most investigated therapeutic use of VR in pediatric settings [

14,

15,

16,

17].

The literature on VR safety, efficacy, and acceptability has grown significantly in recent years. VR has proven to be an effective distraction tool, capable of increasing children's comfort during sedation procedures and ensuring high levels of satisfaction among patients [

2,

3,

18].

VR can offer several potential advantages to a cohort of pediatric patients such as cancer patients, who often need several procedures during their illness trajectory as well improving their quality of life during and after treatment. A particular focus that has not yet been thoroughly investigated is the application of VR in pain management in procedures aimed at patients with chronic diseases, such as pediatric oncohematological patients [

2]. Given the repeated harm that can occur if pain is not adequately treated, it is important to consider once more in these children the use of alternative strategies for managing pain beyond standard care.

According to Sinatra [19], anxiety, worry, and stress can have a detrimental influence on hospital stay, decrease the efficacy of therapies, prolong recovery times, and have long-term psychological effects. Sedation during medical operations can have a detrimental impact on the overall experience and quality of life of the patient [20].

Regarding previous sedation procedures, it is important to note that, over time, patients tend to become more familiar with them. When these procedures are managed appropriately, they can help patients anticipate outcomes, thereby reducing anxiety and uncertainty. The literature states that the way pediatric patients use coping strategies to deal with pain is influenced by various factors such as age, sex and previous pain experiences [21–24].

Parental anxiety has been widely recognized in the literature as a significant factor influencing children’s preprocedural anxiety. Elevated stress and anxiety levels in caregivers can negatively affect the emotional experience of the child, amplifying their own anxiety response [

25]. Several studies have shown a bidirectional association between parental and pediatric anxiety [

23,

25,

26].

Based on these findings, the present study aimed to assess anxiety symptoms in both pediatric patients and their caregivers during the pre- and the post-procedure phase. Specifically, we examined the correlation between caregiver and child anxiety, as well as potential differences in anxiety levels based on the child's age and gender.

Furthermore, given the established role of pain coping strategies in modulating anxiety, we sought to identify the most used strategies and explore whether their use varied according to age and the number of previous painful procedures, assuming a possible habituation effect over time.

Finally, a central objective of the study was to evaluate whether virtual reality (VR) could effectively reduce the perception of fear and pain in patients during procedures. We also evaluated patient satisfaction and gathered feedback from healthcare professionals involved in its implementation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The present study involved all pediatric patients followed by the Pediatric Hematology-Oncology Clinic of the University Hospital of Padua, along with their caregivers, who underwent procedural sedation. The project was presented to both children and their parents and informed consent was obtained through a specific consent form.

A total of 29 pediatric patients diagnosed with hematological-oncological conditions participated in the study. The participants ranged in age from 8 to 20 years (M = 12.19 years, SD = 3.16), 72.4% were male (n = 21) and 27.6% were female (n = 8). All patients had acute medical conditions, with the majority diagnosed with leukemia (ALL, AML, APL); for a complete breakdown of diagnoses, see

Table 1.

The children also differed in terms of the type of medical procedure they underwent, with four different types represented in the sample (see

Table 2. for details).

In addition to the children, their parents were also invited to participate in the study. Among the 29 caregivers, 10.3% were fathers (n = 3) and 89.7% were mothers (n = 26). Of these, 51.7% (n = 15) completed the study by filling in the questionnaires. Sociodemographic information on caregivers was collected via a specific questionnaire (see

Table 3. for a summary).

2.2. Procedure

This study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Hospital of Padua (protocol code: 5809/AO/23; date of approval 7/20/2023). After signing the parental informed consent, participants used VR headsets as a distraction tool playing with TOMMI or Nature Trek apps before and during induction of anesthesia for medical procedures. Procedural sedation in our institution is provided by the Pediatric Palliative Care and Pain Service team, which can provide procedural sedation mainly for bone marrow puncture, lumbar puncture, bone biopsies, both in the Pediatric Hematology-Oncology Clinic hospitalization unit and in the day hospital setting.

Pain and fear levels were measured using the Wong-Baker Faces Pain Scale (Wong & Baker, 1983) and the Children’s Fear Scale (McMurtry, 2011), respectively, before the procedure (T1) and after awakening (T2). At T1 also the SAFA-anxiety scale and PPCI for patients were adopted, while for caregivers GAD7 and ASA27 were administered.

2.3. Instruments

The instruments adopted for patients and their caregivers were described below.

2.3.1. Sociodemographic and Medical Information

Sociodemographic and medical information was collected through a structured questionnaire administered to caregivers. The questionnaire included items that evaluated parental education and occupational status. Specifically, the following variables were considered: years of education, type of employment, average weekly working hours, economic status, and number of family members and children in the household. Additional items collected medical information such as the type of diagnosis and the number of procedures performed under sedation.

2.3.2. SAFA General Screening Anxiety Scale

The SAFA battery is a self-administered diagnostic tool. Unlike tests developed individually by different authors, its strength lies in being a coordinated set of scales designed to assess a broad range of symptoms and mental states related to internalizing disorders. The wording of the items is adapted to the age of the subject, and for younger children, the number of items is slightly reduced, which improves the reliability of the instrument between age groups. Each scale can also be administered independently. Furthermore, the diagnostic criteria are compatible with the DSM-5. The battery consists of six scales, each available in different versions based on age groups: 8–10 years (“e”), 11–13 years (“m”), and 14–18 years (“s”). In this study, only the anxiety scale was used [

27].

2.3.3. PPCI

The Pediatric Pain Coping Inventory (PPCI; Varni et al., 1996; Bonichini & Axia, 2000) is a self-report instrument available in both child- and parent-report forms. It consists of 41 items designed to provide a standardized assessment of the child’s and caregiver’s perceptions of the coping strategies the child uses to manage physical pain. Items are rated on a 3-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (never, not at all) to 1 (sometimes) to 2 (often, a lot), developed for clarity and ease of administration.

According to the authors, children in pain may adopt five distinct coping strategies, which correspond to the following subscales:

Cognitive Self-Instruction (α = 0.74): Includes internal self-statements that help the child cognitively manage pain (7 items);

Problem Solving (α = 0.67): Encompasses deliberate actions intended to manage or alleviate pain (10 items);

Distraction (α = 0.66): Involves shifting attention away from pain to other stimuli or activities (9 items);

Seeking Social Support (α = 0.66): Refers to seeking comfort, understanding, or help from parents, peers, or others (9 items);

Catastrophizing/Helplessness (α = 0.57): Reflects feelings of powerlessness and victimization in relation to pain (6 items).

Findings from a study conducted by Tremolada et al. (2022) using the PPCI in children with cancer highlighted that coping strategies such as distraction were influenced by treatment-related factors and the child’s age. Additionally, the use of specific pain coping strategies, particularly seeking social support, was associated with a reduced need for sedative-hypnotic medication during bone marrow aspiration. On the contrary, a catastrophic coping style was identified as a negative predictor, linked to the need for higher doses of propofol during sedation [

28,

29].

2.3.4. Wong-Baker Faces Pain Rating Scale

This self-assessment tool is designed to facilitate communication about physical pain, especially in pediatric contexts. It features six facial expressions, each paired with a numerical value and a short verbal descriptor, ranging from a smiling face at 0 (“no hurt”) to a crying face at 5 (“hurts worst”).

By combining visual, numerical, and linguistic cues, the scale provides children with multiple ways to recognize and communicate their perceived intensity of pain. This approach supports healthcare professionals in accurately assessing the subjective experience of pain of the child and in implementing appropriate interventions to manage discomfort [

30].

2.3.5. Children’s Fear Scale

This tool is designed to assess fear in children undergoing painful medical procedures. It consists of a single-item, five-point scale that features a sequence of sex-neutral faces, ranging from a neutral expression indicating no fear to an expression of extreme fear. Children are asked to select the face that best represents their current level of fear or anxiety.

Originally adapted from the Faces Anxiety Scale [

31] the CFS has shown good construct validity in initial validation studies, including strong concurrent validity with other child fear measures and moderate discriminant validity with observed coping behaviors. The scale also demonstrates acceptable test-retest and interrater reliability. It offers a quick and accessible way of evaluating the perceived fear of children in clinical settings [

32].

2.3.6. GAD7

GAD-7 is a brief self-administered 7-item questionnaire that is used to screen for and assess the severity of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). Each item is rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day), with total scores ranging from 0 to 21. Cut-off scores of 5, 10, and 15 indicate mild, moderate, and severe anxiety, respectively. A score of 10 or greater suggests the need for further clinical evaluation.

The scale demonstrates high sensitivity (89%) and specificity (82%) to detect GAD at the recommended threshold. It also shows moderate effectiveness in identifying other anxiety-related disorders, including panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder. GAD-7 has demonstrated good reliability and strong criterion, construct, factorial, and procedural validity. Higher scores have been consistently associated with greater functional impairment in multiple domains of life [

32].

2.3.7. ASA27

The Adult Separation Anxiety Questionnaire is a self-report instrument designed to assess symptoms of adult separation anxiety, including excessive worry, distress, and avoidance related to separation from attachment figures or familiar environments. The scale comprises 27 items derived from the Adult Separation Anxiety Semi-Structured Interview (ASA-SI), rated on a four-point Likert scale from 0 (“this has never happened”) to 3 (“this happens very often”), yielding total raw scores ranging from 0 to 81.

Higher scores indicate greater severity of separation anxiety symptoms. Interpretative cut-offs include: scores of 0–15 suggest low or no separation anxiety, 16–21 reflect mild to moderate symptoms (highly sensitive but potentially including false positives), and scores ≥22 indicate probable adult separation anxiety disorder (ASAD), characterized by pervasive symptoms such as dependency, avoidance behaviors, excessive concern for attachment figures, and impaired autonomy [

33].

2.4. Statistical Analyses Plan

Descriptive statistics will show the position of patients and caregivers regarding the level of general and separation anxiety. Mean and Standard deviations will be run also for the coping with pain strategies of patients. Non-parametric tests such as Spearman correlations, Wilcoxon signed-rank and Mann Whitney tests will be run to address the other research questions.

3. Results

3.1. Anxiety Levels in Pediatric Patients and Their Caregivers and Associated Socio-Demographic Variables

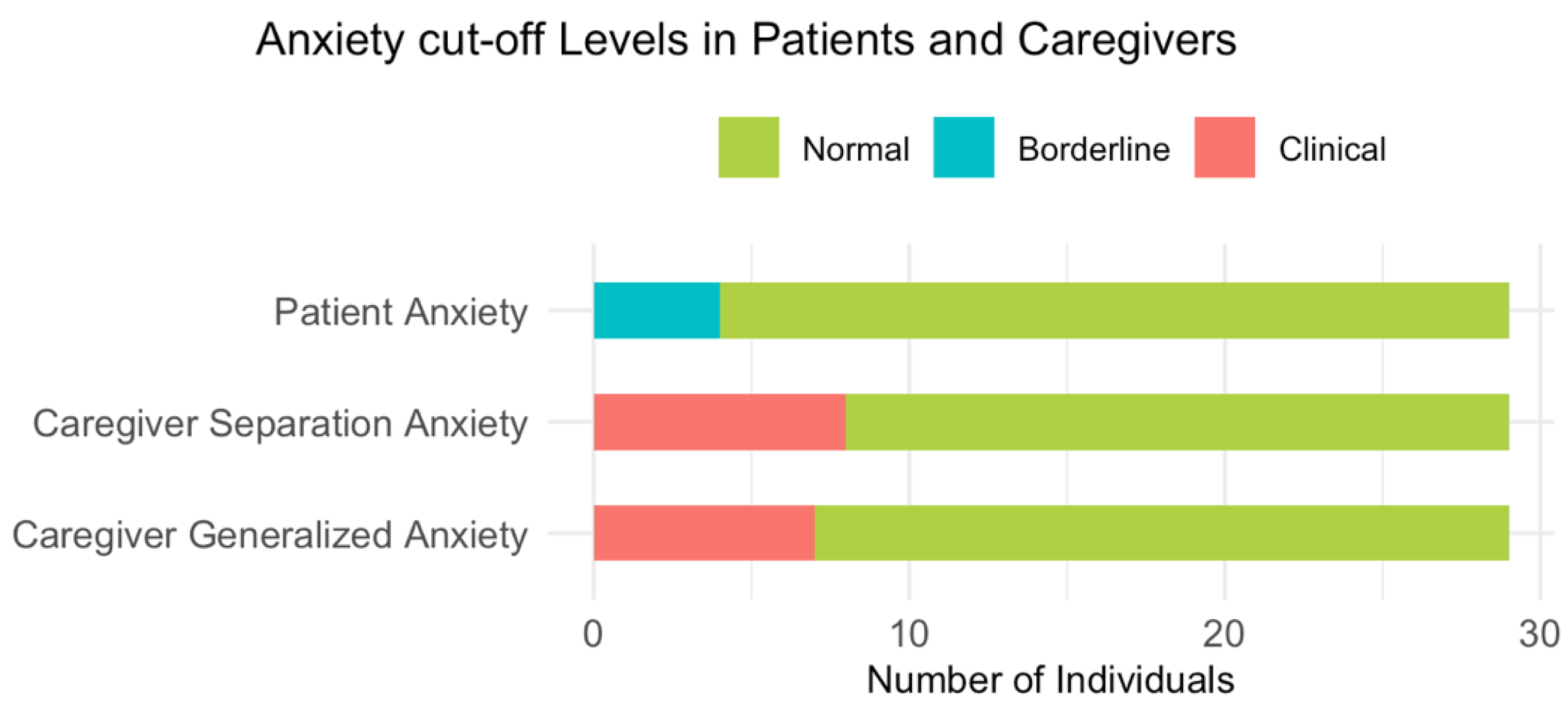

Most pediatric patients reported anxiety levels within the normal range (86.2%), with only 13.8% falling into the borderline range. Similarly, the majority of caregivers reported normal levels of separation anxiety (72.4%) and general anxiety (75.9%). However, 27.5% and 24.1% of caregivers scored within the clinical range for separation and general anxiety, respectively. These results are illustrated in

Figure 1.

T-scores on the SAFA-A scale, administered to patients prior to the sedation procedure, revealed significant positive correlations with age in the generalized anxiety (rho = 0.46, p = 0.012) and social anxiety (rho = 0.65, p < 0.001) subscales. No significant gender differences were observed in anxiety subscale scores.

To examine the relationship between caregiver anxiety (measured with ASA and GAD-7) and pre-procedural anxiety in children (measured with SAFA-A), non-parametric Spearman correlations were conducted. Additionally, significant correlation was found between caregiver separation anxiety and children's generalized anxiety (rho = 0.60, p < 0.001). In addition, significant correlations were observed between SAFA-A total scores and ASA (rho = 0.424, p = 0.025), as well as between SAFA-A and GAD-7 scores (rho = 0.51, p = 0.005). These findings suggest a strong association between caregiver anxiety symptoms and those of the child.

3.2. Coping with Pain: Differences by Sex and Exposure to Past Painful Procedures

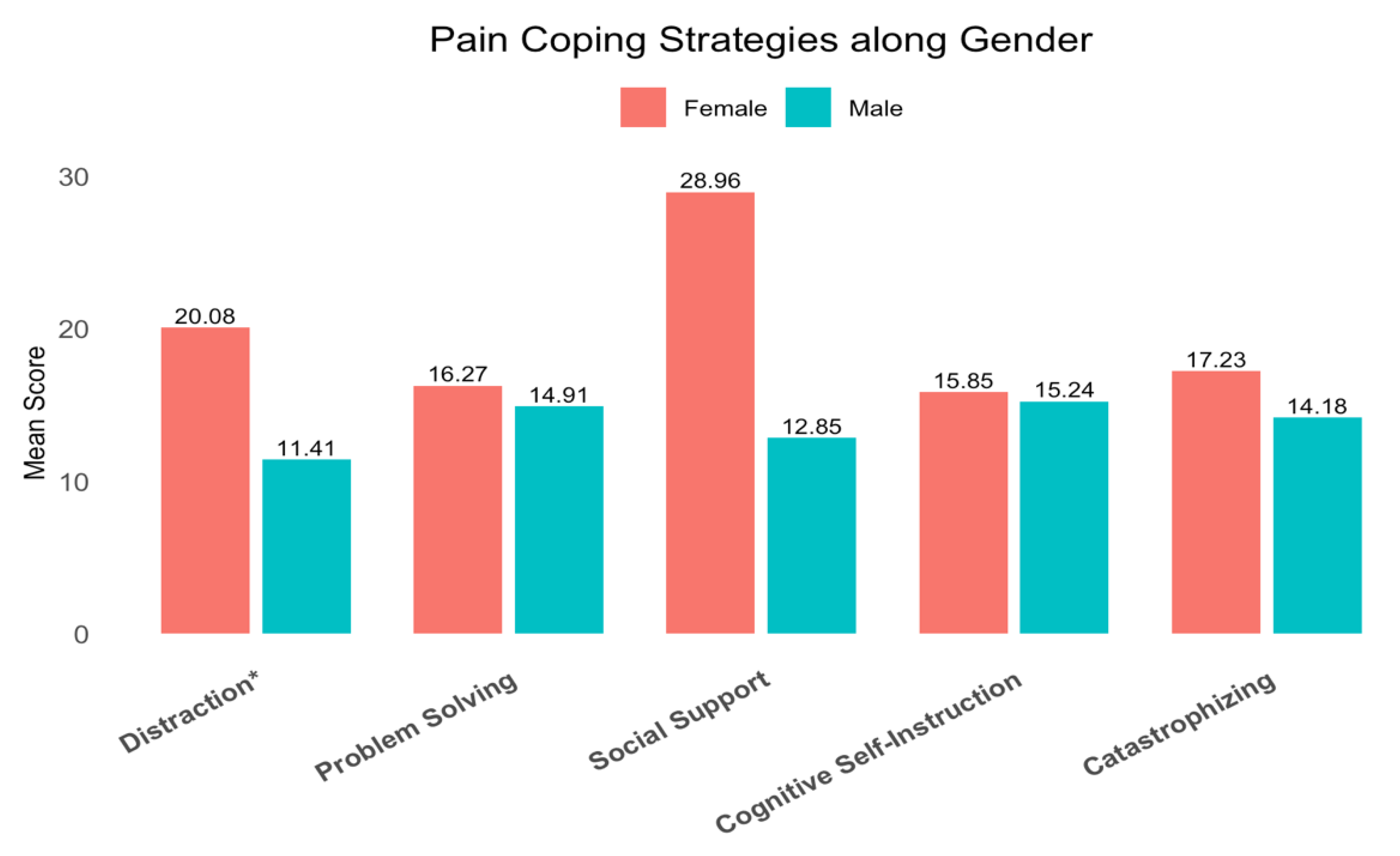

To address the second research question, the nonparametric Mann–Whitney test was used to assess differences in the use of coping strategies (PPCI) among young patients based on gender. Analysis revealed statistically significant differences in mean rankings for specific strategies.

Table 4 and

Figure 2 illustrate the results.

A significant negative Spearman correlation was observed between the global coping score and the number of anesthesia-based medical procedures (rho = –.46, p = .010). This suggests that individuals who undergo a higher number of such procedures tend to exhibit lower overall coping skills, highlighting a potential inverse relationship between procedural exposure and coping resources.

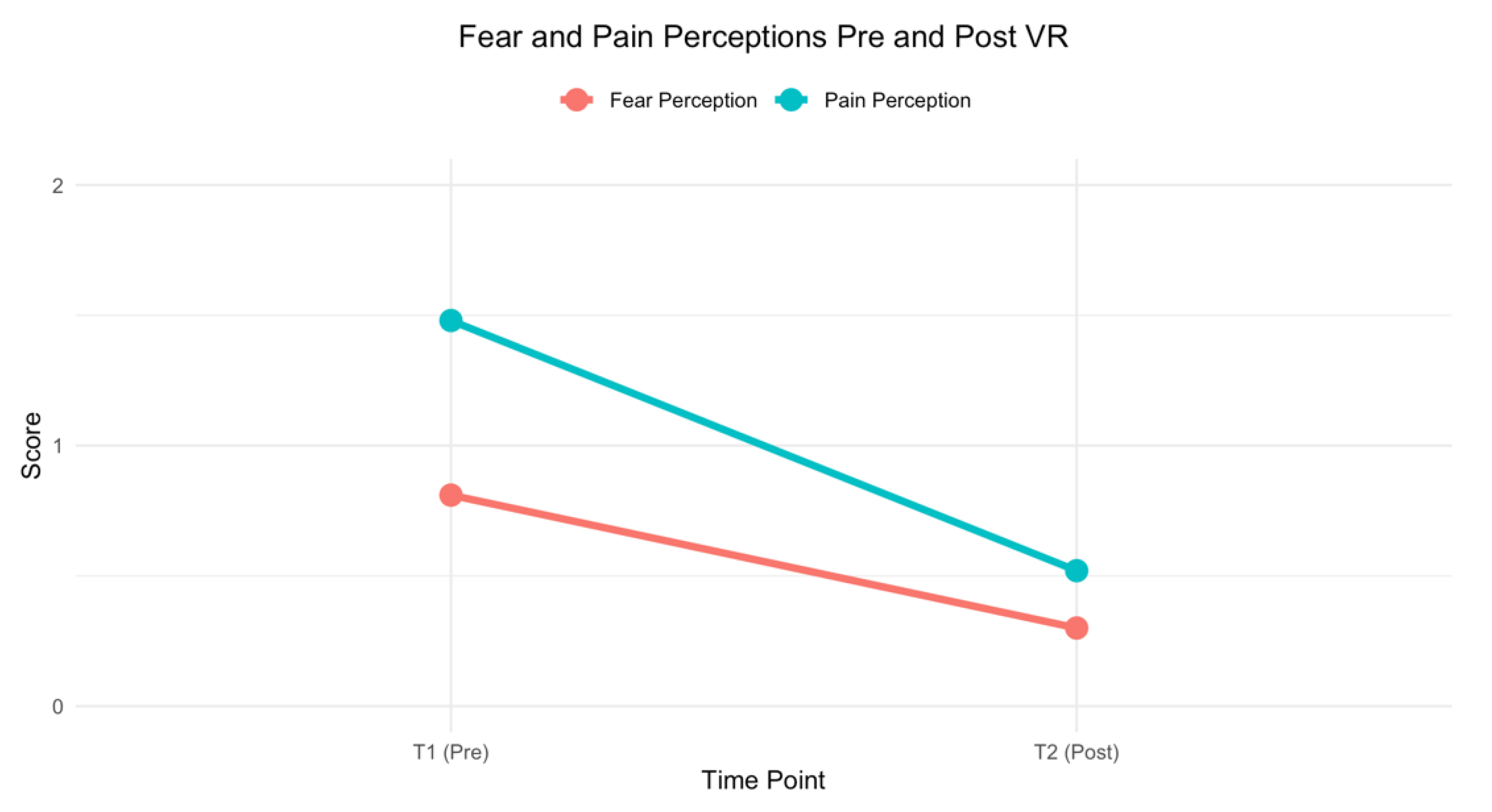

3.3. Virtual Reality Experience Effect on Fear and Pain Perceptions in Cancer Patients

To assess the effectiveness of VR use on the perception of fear and pain before and after the procedure, two Wilcoxon signed rank tests were performed. The first test (Z = –2.74,

p = 0.006) revealed a significant reduction in fear perception between pre-procedure (Mean T1 = 0.81, SD = 1.27) and post-procedure (Mean T2 = 0.30, SD = 0.61). Similarly, the second Wilcoxon test (Z = –2.74,

p = 0.006) showed a significant decrease in pain perception from pre-procedure (Mean T1 = 1.48, SD = 2.19) to post-procedure (Mean T2 = 0.52, SD = 1.05). These results are illustrated in

Figure 3.

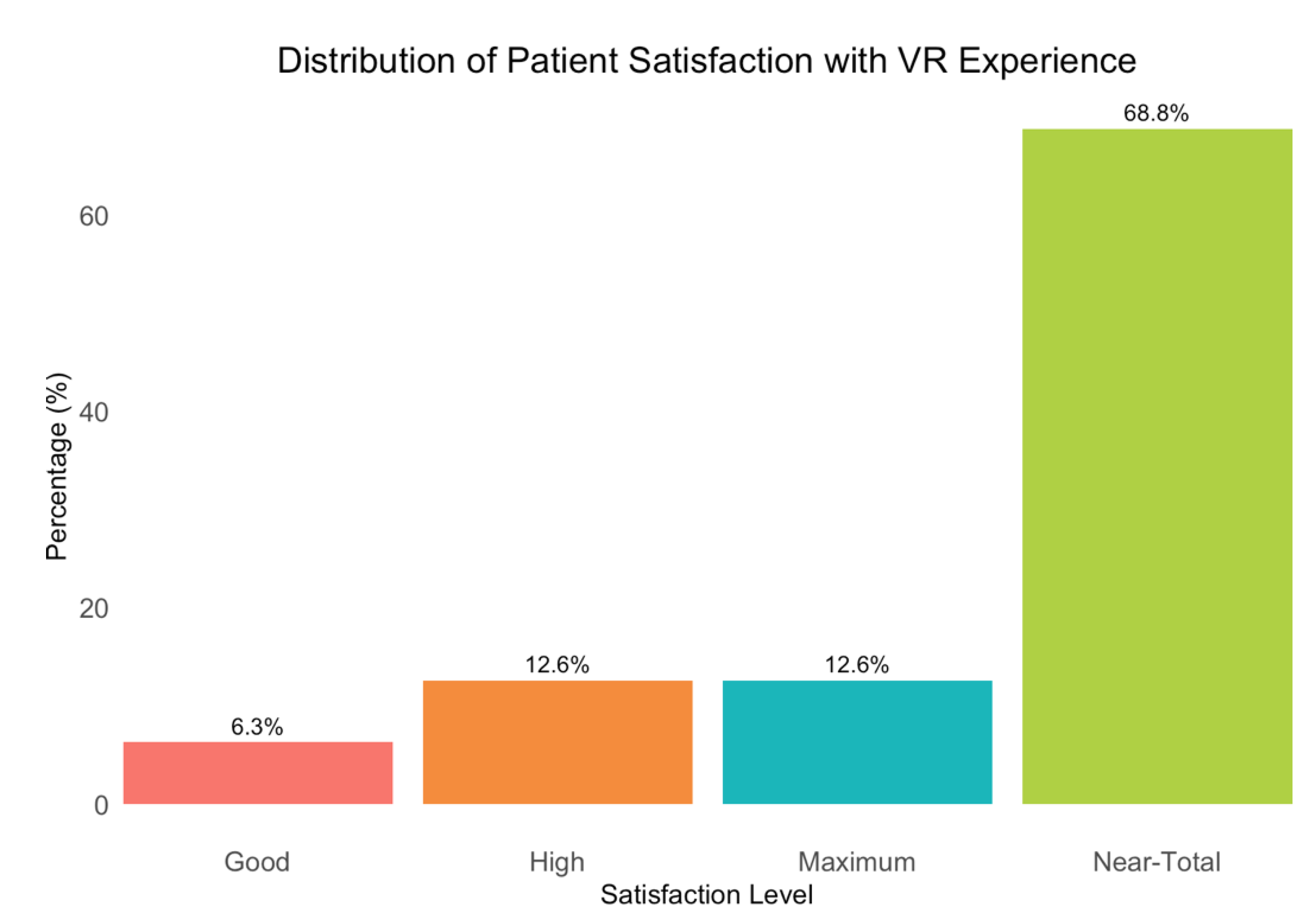

3.4. Level of Satisfaction with VR Activity Reported by Patients and Healthcare Professionals

Patients reported a high level of satisfaction with their VR experience, as shown in

Figure 4.

Healthcare professionals reported initial perplexity, with 50.1% expressing concerns about the time required for VR implementation. However, 68.8% of them revised their opinion due to the observed higher effectiveness of the technology. They noted improvements in patient behavior, suggesting that the use of virtual reality could be considered beneficial. Ultimately, 62.6% of healthcare professionals agreed that they would support the use of virtual reality in future procedures, reflecting a general consensus on its potential advantages.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the impact of VR on anxiety, pain, and coping in pediatric oncohematological patients undergoing sedation procedures, and to explore the interaction between patient and caregiver anxiety.

Our findings indicate that patients generally reported low levels of anxiety, while a notable proportion of caregivers experienced clinically significant anxiety. This highlights the importance of addressing the psychological needs of caregivers in the context of pediatric procedures, as their own anxiety can negatively influence the child's experience [

25,

26].Interestingly, we found a significant positive correlation between caregiver anxiety and patient anxiety levels, with both separation and general anxiety in caregivers being associated with higher preprocedural anxiety in children. This is consistent with previous research that has demonstrated the influence of parental anxiety on pediatric patients' anxiety responses in medical settings [23, 25, 26].

An important aspect reported in the literature concerns gender differences. Unlike some previous studies that have reported gender differences in preprocedural anxiety, we did not observe any significant gender differences in our patient sample. In fact, girls appear to have significantly higher levels of preoperative anxiety than males [

22,

23]. In addition to gender, age is also considered a risk factor for pre-procedural anxiety in children, but in this regard the literature presents conflicting data. Some studies, in fact, highlight that young children are at increased risk of showing anxious symptoms due to their difficulty fully understanding the situations they experience [

24,

35,

36]. In contrast, other research suggests that older children are at increased risk of developing anxious symptoms, due to their greater ability to process cognitive information. In fact, they may be more aware of the implications of medical procedures and of the possible consequences, which may intensify their worries and anxieties [

37,

38]. However, we did find that older children reported higher levels of generalized and social anxiety. This could be attributed to their increased cognitive awareness and understanding of the implications of medical procedures.

Regarding coping strategies, our results showed that gender influences how young patients cope with pain, particularly in the use of distraction strategies, with girls reporting higher levels than boys. This finding is consistent with the existing literature, which highlights gender differences in coping strategies, emphasizing that girls tend to use cognitive and avoidance coping mechanisms more frequently, such as distraction. These differences can be attributed to various psychological, social, and cultural factors that shape the way boys and girls approach and manage pain [21]. Furthermore, we observed a negative correlation between the number of previous anesthesia-based medical procedures and the overall use of pain coping strategies. This suggests that repeated exposure to such procedures might be associated with a reduction in active coping abilities. This phenomenon is consistent with existing literature, which indicates that invasive and sedation-based medical experiences can negatively impact children's psychological well-being, increasing the risk of emotional and behavioral difficulties, such as anxiety, depression, and reduced resilience [39]. Over time, these repeated exposures can erode the child’s coping resources, making it more difficult to effectively manage stress and pain. This finding underscores the importance of considering not only the frequency but also the psychological burden of medical procedures. Indeed, the moment of the procedure is often the most feared by young patients. Anxiety, fear, and stress can significantly affect their hospital experience, reduce treatment effectiveness, and prolong recovery times, potentially leading to long-term psychological consequences [19]. Sedation-based procedures, although clinically necessary, may thus negatively influence overall perception of care and quality of life of a patient [40].

In response to these challenges, increasing attention has been given to nonpharmacological interventions that can support emotional regulation during medical procedures. As a result, several studies have demonstrated the positive effects of virtual reality (VR) in pediatric settings [2-5, 13-16, 41], showing that VR offers an immersive and engaging distraction that helps manage fear and pain, significantly improving the procedural experience for young patients. This suggests that integrating virtual reality into clinical practice could be a promising strategy to preserve or even improve coping resources in children repeatedly exposed to medical procedures.

In our study, the use of virtual reality (VR) as a distraction technique was associated with a significant reduction in the perception of both fear and pain from pre- to post-procedure. While it is important to acknowledge that a natural decline in fear and pain may occur after the completion of a medical procedure due to the relief of anticipatory anxiety, our findings suggest that the immersive VR experience likely contributed to this effect beyond the procedural endpoint itself.

Specifically, the calming and engaging nature of VR prior to sedation may play a key role in modulating emotional states before and after the procedure. By promoting relaxation and diverting attention away from the medical context, VR can foster a more peaceful induction into sedation, which can influence the patient’s emotional state upon awakening. Patients who fall asleep in a calm and distracted state may wake up in a similarly relaxed condition, retrospectively evaluating the experience as less distressing and reporting lower levels of fear, anxiety, and pain [

19,

42].

Furthermore, research indicates that VR not only affects real-time pain perception but can also influence pain memory. According to [

42], children's memory of pain is not merely a passive recall but can be shaped by emotional context and attention at the time of encoding. Therefore, providing a pleasant and immersive experience during a stressful medical event can help reframe the emotional memory associated with the procedure, potentially reducing anticipation fear in future exposures. Similarly, a growing body of literature has shown that VR distraction significantly reduces acute procedural pain and anxiety in pediatric patients [

2,

3,

5,

13,

16,

44], and that its effects may persist due to the formation of more positive procedural memories [13, 44.

These findings underscore the value of VR not only as a tool for immediate pain and fear reduction, but also as a means of positively influencing how medical experiences are encoded and remembered, with implications for long-term emotional coping and procedural tolerance.

In line with this, patients in our study reported high levels of satisfaction with the VR experience. While some healthcare professionals initially expressed concerns about the time required for VR implementation, the majority recognized its benefits in improving patient cooperation and emotional regulation, and expressed a willingness to adopt the technology in future procedures. This positive feedback supports the feasibility of integrating VR into routine clinical care and suggests its potential as a sustainable tool in pediatric settings. Importantly, our findings further reinforce the role of VR as a nonpharmacological adjunct for managing procedural pain and anxiety in children with chronic medical conditions, particularly in oncohematological patients who often undergo repeated interventions throughout the path of the disease.

Despite the growing literature on VR in acute procedural contexts, its application in pediatric populations with chronic and complex needs, such as those with cancer, genetic and metabolic disorders, or neurological conditions requiring frequent sedation and rehabilitation, remains relatively underexplored. For these vulnerable groups, who may face cumulative emotional and physical burdens from repeated procedures, virtual reality may serve not only as a distraction tool but also as a protective factor against the long-term psychological sequelae of unmanaged pain, and should be considered as a complement to standard medical care. In this sense, expanding the use of VR could represent a crucial step toward more holistic and child-centred approaches to procedural care, improving not only immediate outcomes, but also the overall experience of treatment and quality of life of patients.

However, some limitations of this study should be acknowledged. The absence of a control group that uses an alternative distraction technique prevents us from fully isolating the unique contribution of the immersive experience itself. Future research should include comparative studies involving nonimmersive interventions (e.g., tablet games, music, or storytelling) to determine whether it is specifically the immersive quality of VR that yields these benefits. Additionally, longitudinal studies are needed to confirm the role of pain memory and assess whether the positive effects of VR on pain perception extend over time, reducing anticipatory anxiety in future procedures.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study reinforces the efficacy of VR as a non-pharmacological tool to manage anxiety and pain in pediatric oncohematological patients undergoing sedation procedures. The results demonstrate VR's potential to enhance the procedural experience, reducing distress and improving overall patient comfort. These findings suggest that VR should be considered for integration into standard care, particularly in pediatric oncology settings. Future research should further explore the long-term effects of VR on pain memory and examine its benefits compared to other distraction techniques. In addition, addressing caregiver anxiety and emotional factors is crucial to optimize patient outcomes.

Key Points:

Efficacy of VR for pain and anxiety

Importance of caregiver anxiety

Potential for improved quality of care

Need for future research

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at Preprints.org, Table S1: Data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.T and A.Z..; methodology, R.M.I. and A.Z..; formal analysis, R.M.I. and M.T..; investigation, R.M.I and M.T..; resources, A.B. and F.B..; data curation, R.M.I.; writing—original draft preparation, M.T and A.Z.; writing—review and editing, R.M.I.; supervision, F.B. and A.B..; project administration, M.T..; funding acquisition, M.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research, including the provision of virtual reality (VR) equipment, was funded by AIL PADOVA ODV as part of the clinical project STAI BENE 3.0 Plus (approval date: 1st February 2024), sponsored by the Italian Ministry of Labor and Social Policies. The project was conducted within the Pediatric Oncology Hematology Division of Padua as part of its clinical care and research activities.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of University Hospital of Padua (protocol code: 5809/AO/23; date of approval 7/20/2023)

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the

Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Softcare studios for the collaboration of Valentino Megale with TOMMI VR APP and all the pediatric patients and their caregivers that participated in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yeung, A.W.K.; Tosevska, A.; Klager, E.; Eibensteiner, F.; Laxar, D.; Stoyanov, J.; Glisic, M.; Zeiner, S.; Kulnik, S.T.; Crutzen, R.; Kimberger, O.; Kletecka-Pulker, M.; Atanasov, A.G.; Willschke, H. Virtual and Augmented Reality Applications in Medicine: Analysis of the Scientific Literature. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e25499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Z.; Yu, S.; Zhang, W.; Liu, X.; Shen, Y.; Weng, H. Virtual Reality for Pain and Anxiety of Pediatric Oncology Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Asia Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2022, 9, 100152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Addab, S.; Hamdy, R.; Thorstad, K.; Le May, S.; Tsimicalis, A. Use of Virtual Reality in Managing Pediatric Procedural Pain and Anxiety: An Integrative Literature Review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2022, 31, 3032–3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chirico, A.; Lucidi, F.; De Laurentiis, M.; et al. Virtual Reality in Health System: Beyond Entertainment. A Mini-Review on the Efficacy of VR During Cancer Treatment. J. Cell. Physiol. 2016, 231, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoag, J.A.; Karst, J.; Bingen, K.; Palou-Torres, A.; Yan, K. Distracting Through Procedural Pain and Distress Using Virtual Reality and Guided Imagery in Pediatric, Adolescent, and Young Adult Patients: Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e30260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izard, S.G.; Juanes, J.A.; García Peñalvo, F.J.; Estella, J.M.G.; Ledesma, M.J.S.; Ruisoto, P. Virtual Reality as an Educational and Training Tool for Medicine. J. Med. Syst. 2018, 42, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mergen, M.; Meyerheim, M.; Graf, N. Reviewing the Current State of Virtual Reality Integration in Medical Education: A Scoping Review Protocol. Syst. Rev. 2023, 12, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyama, H. Virtual Reality for the Palliative Care of Cancer. Virtual Reality in Neuro-Psycho-Physiology.

- Schneider, S.M.; Hood, L.E. Virtual Reality: A Distraction Intervention for Chemotherapy. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2007, 34, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanin, A.; Mercante, A.; Benini, F. Virtual Reality in Children and Adolescents with Pain and Palliative-Care Needs. In Virtual Reality for Serious Illness; Routledge: London, UK, 2024; pp. 78–103. [Google Scholar]

- Mercante, A.; Zanin, A.; Vecchi, L.; De Tommasi, V.; Benini, F. Virtual Reality Intervention as Support to Pediatric Palliative Care Providers: A Pilot Study. Acta Paediatrica 2024, 113, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, S.N.; Carr, D.B.; Cohen, M.; et al. The Revised International Association for the Study of Pain Definition of Pain: Concepts, Challenges, and Compromises. Pain 2020, 161, 1976–1982 DOI. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, H.G.; Chambers, G.T.; Meyer, W.J.; Arceneaux, L.L.; Russell, W.J.; Seibel, E.J. .; Patterson, D.R. Virtual Reality as an Adjunctive Non-Pharmacologic Analgesic for Acute Burn Pain During Medical Procedures. Ann. Behav. Med. 2011, 41, 183–191 DOI. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrett, B.; Taverner, T.; Masinde, W.; Gromala, D.; Shaw, C.; Negraeff, M. A Rapid Evidence Assessment of Immersive Virtual Reality as an Adjunct Therapy in Acute Pain Management in Clinical Practice. Clin. J. Pain 2014, 30, 1089–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persky, S.; Lewis, M.A. Advancing Science and Practice Using Immersive Virtual Reality: What Behavioral Medicine Has to Offer. Transl. Behav. Med. 2019, 9, 1040–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pourmand, A.; Davis, S.; Marchak, A.; Whiteside, T.; Sikka, N. Virtual Reality as a Clinical Tool for Pain Management. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2018, 22, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marseglia, G.L.; Alessio, M.; Da Dalt, L.; Giuliano, M.; Ravelli, A.; Marchisio, P. Acute Pain Management in Children: A Survey of Italian Pediatricians. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2019, 45, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eijlers, R.; Dierckx, B.; Staals, L.M.; Berghmans, J.M.; van der Schroeff, M.P.; Strabbing, E.M. .; Utens, E.M. Virtual Reality Exposure Before Elective Day Care Surgery to Reduce Anxiety and Pain in Children: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 2019, 36, 728–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinatra, R. Causes and Consequences of Inadequate Management of Acute Pain. Pain Med. 2010, 11, 1859–1871 DOI. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshijima, H.; Higuchi, H.; Sato, A.; Shibuya, M.; Morimoto, Y.; Fujisawa, T.; Mizuta, K. Patient Satisfaction with Deep Versus Light/Moderate Sedation for Non-Surgical Procedures: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicine 2021, 100, e27176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compas, B.E.; Jaser, S.S.; Dunn, M.J.; Rodriguez, E.M. Coping with Chronic Illness in Childhood and Adolescence. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2012, 8, 455–480 DOI. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, D.E.; Rose, J.B. Gender Differences in Post-Operative Pain and Patient Controlled Analgesia Use Among Adolescent Surgical Patients. Pain 2004, 109, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, R.; Yaddanpudi, S.; Panda, N.B.; Kohli, A.; Mathew, P.J. Predictors of Pre-Operative Anxiety in Indian Children. Indian J. Pediatr. 2018, 85, 504–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vest, E.; Armstrong, M.; Olbrecht, V.A.; Thakkar, R.K.; Fabia, R.B.; Groner, J.; Noffsinger, D.; Tram, N.K.; Xiang, H. Association of Pre-Procedural Anxiety with Procedure-Related Pain During Outpatient Pediatric Burn Care: A Pilot Study. J. Burn Care Res. 2023, 44, 610–617 DOI. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santapuram, P.; Stone, A.L.; Walden, R.L.; Alexander, L. Interventions for Parental Anxiety in Preparation for Pediatric Surgery: A Narrative Review. Children 2021, 8, 1069 DOI. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, B.D.; Wood, J.J.; Weisz, J.R. Examining the Association Between Parenting and Childhood Anxiety: A Meta-Analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 27, 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cianchetti, C.; Fancello, G.S. SAFA: Scale psichiatriche di autosomministrazione per fanciulli e adolescenti: Manuale; OS: Firenze, Italy, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Varni, J.W.; Waldron, S.A.; Gragg, R.A.; Rapoff, M.A.; Bernstein, B.H.; Lindsley, C.B.; Newcomb, M.D. Development of the Waldron/Varni Pediatric Pain Coping Inventory. Pain 1996, 67, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonichini, S.; Axia, G. La valutazione delle strategie di coping al dolore fisico nei bambini di età scolare. Psicol. Clin. dello Sviluppo 2000, 4, 97–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, D.L.; Baker, C.M. Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale [Database Record]. APA PsycTests 1988. [CrossRef]

- McKinley, S.; Coote, K.; Stein-Parbury, J.; Stein-Parbury, J. Development and testing of a Faces Scale for the assessment of anxiety in critically ill patients. J. Adv. Nurs. 2003, 41, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurtry, C.M.; Noel, M.; Chambers, C.T.; McGrath, P.J. Children's Fear During Procedural Pain: Preliminary Investigation of the Children's Fear Scale. Health Psychol. 2011, 30, 780–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.W.; Löwe, B. A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manicavasagar, V.; Silove, D.; Wagner, R.; Drobny, J. A Self-Report Questionnaire for Measuring Separation Anxiety in Adulthood. Compr. Psychiatry 2003, 44, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.I.; Farrell, M.A.; Parrish, K.; Karla, A.M.A.N. Preoperative Anxiety in Children: Risk Factors and Non-Pharmacological Management. Middle East J. Anaesthesiol. 2011, 21, 153–164. [Google Scholar]

- Reinfjell, T.; Diseth, T.H. Pre-Procedure Evaluation and Psychological Screening of Children and Adolescents in Pediatric Clinics. In Pediatric Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry: A Global, Healthcare Systems-Focused, and Problem-Based Approach; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 193–215. [Google Scholar]

- Vasey, M.W.; Crnic, K.A.; Carter, W.G. Worry in Childhood: A Developmental Perspective. Cognit. Ther. Res. 1994, 18, 529–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muris, P.; Merckelbach, H.; Luijten, M. The Connection Between Cognitive Development and Specific Fears and Worries in Normal Children and Children with Below-Average Intellectual Abilities: A Preliminary Study. Behav. Res. Ther. 2002, 40, 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakri, M.H.; Ismail, E.A.; Ali, M.S.; Elsedfy, G.O.; Sayed, T.A.; Ibrahim, A. Behavioral and Emotional Effects of Repeated General Anesthesia in Young Children. Saudi J. Anaesth. 2015, 9, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mistraletti, G.; Umbrello, M.; Mariani, V.; Carloni, E.; Miori, S.; Taverna, M.; Sabbatini, G.; Formenti, P.; Terzoni, S.; Destrebecq, A.L.; et al. Conscious Sedation in Critically Ill Patients Is Associated with Stressors Perception Lower Than Assessed by Caregivers. Minerva Anestesiol. 2018, 84, 1150–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, G.; Wiederhold, B.K.; Mantovani, F. Neuroscience of Virtual Reality: From Virtual Exposure to Embodied Medicine. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2019, 22, 82–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yildiz, N.; Besir, A.; Tugcugil, E.; Dohman, D. The Effect of Pre-Operative Sleep Quality on Post-Operative Pain and Emergence Agitation: Prospective and Cohort Study. Cir. Cir. 2023, 91, 743–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noel, M.; Chambers, C.T.; McGrath, P.J.; Klein, R.M.; Stewart, S.H. The Role of State Anxiety in Children's Memories for Pain. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2012, 37, 567–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, H.G.; Patterson, D.R.; Carrougher, G.J.; Sharar, S.R. Effectiveness of Virtual Reality-Based Pain Control with Multiple Treatments. Clin. J. Pain 2001, 17, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).