Submitted:

03 May 2025

Posted:

05 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Equipment

2.3. Method Development

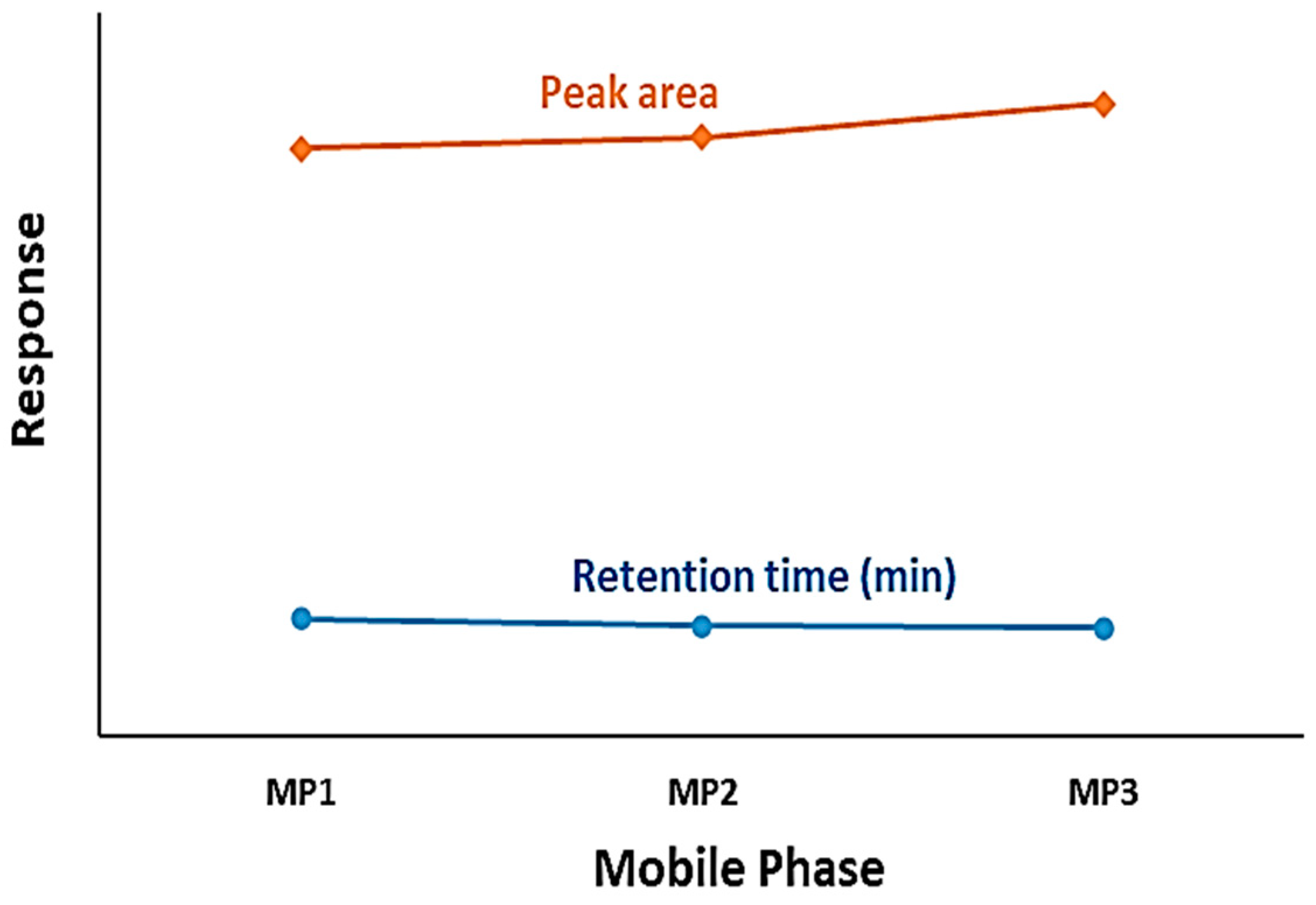

2.3.1. Mobile Phase Optimization

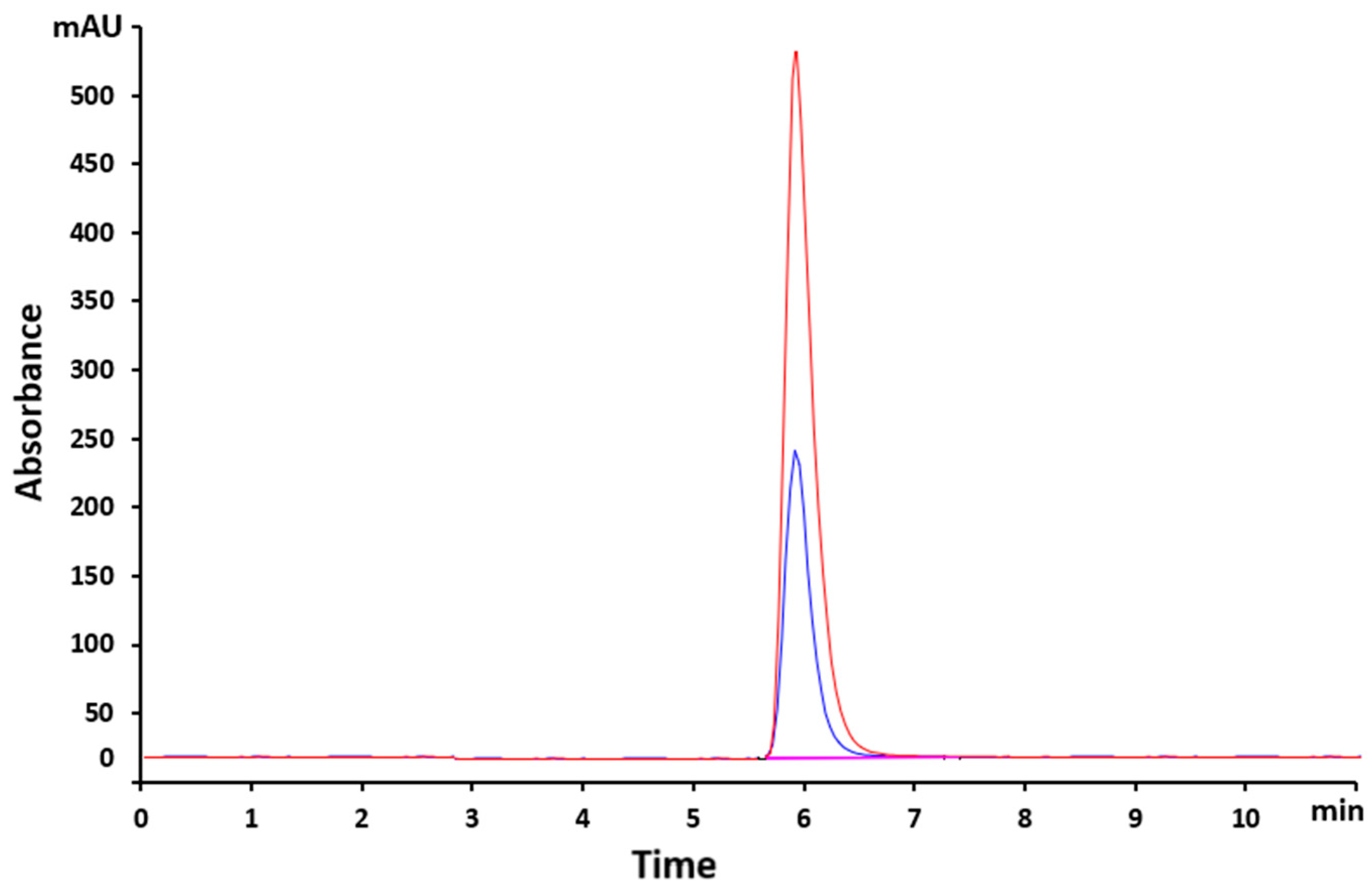

2.3.2. Column Optimization

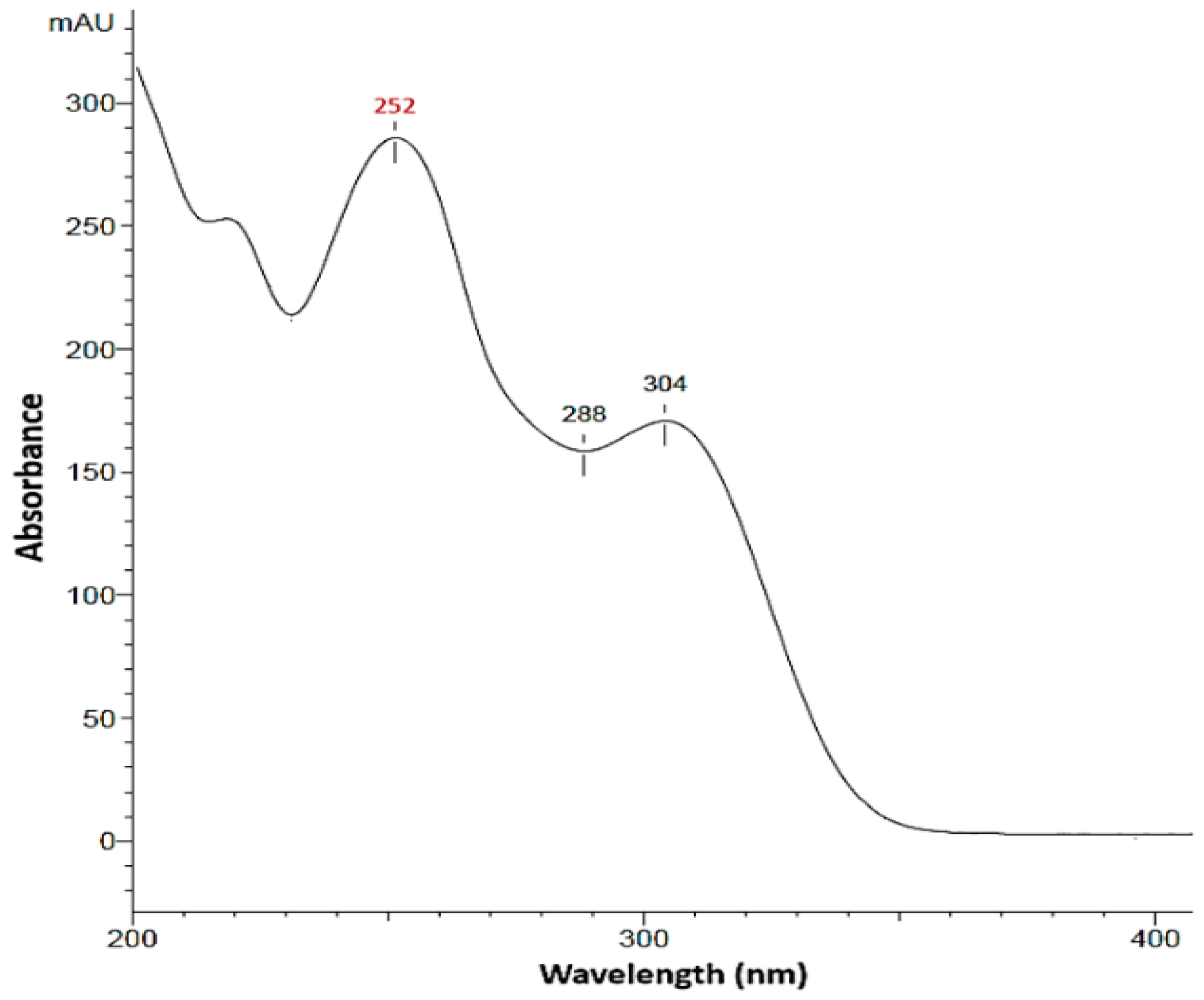

2.3.3. Determination of the Wavelength Corresponding to MAXIMUM absorption (λ max)

2.3.4. Determination of the Retention Time for VEM

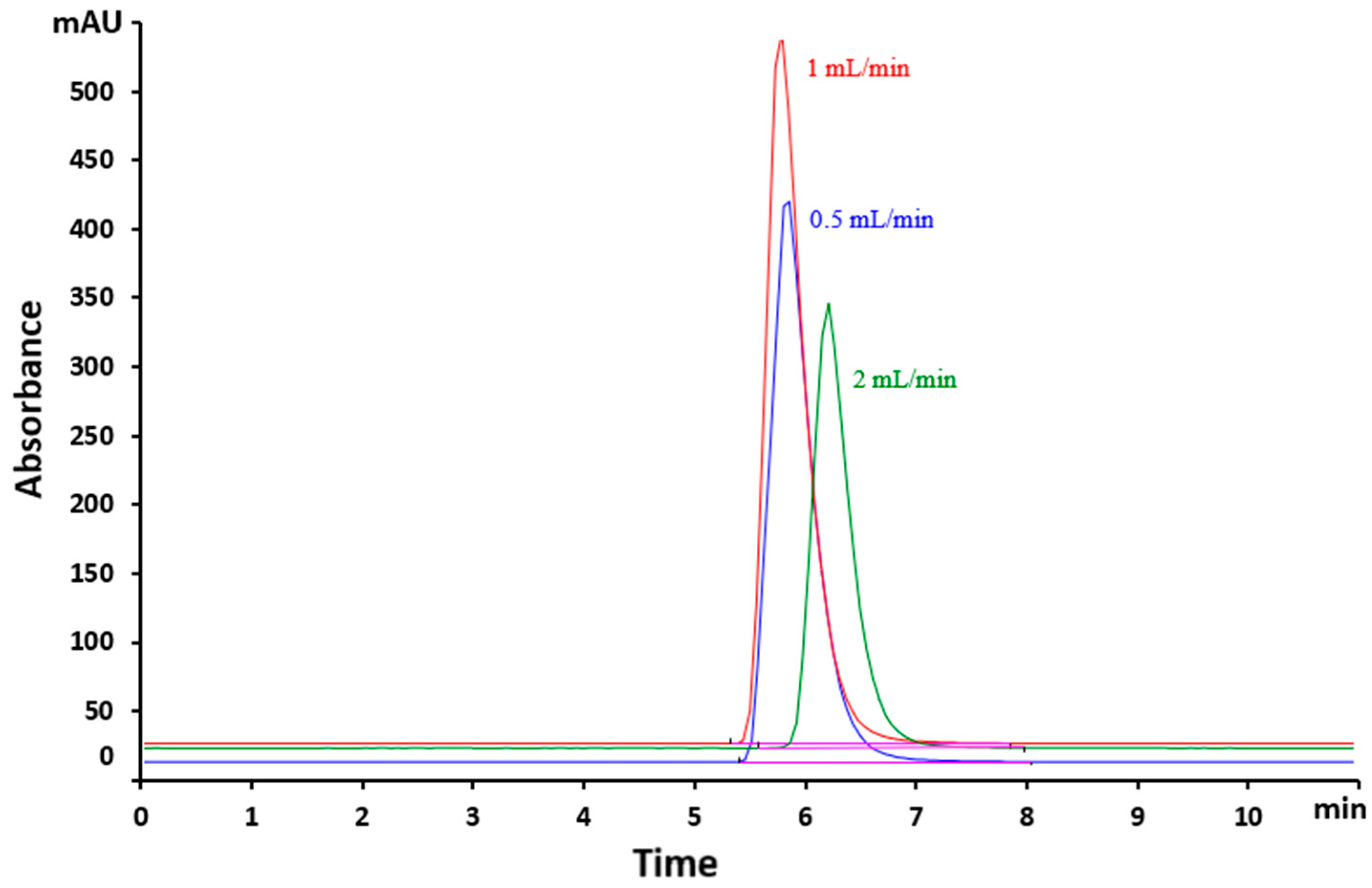

2.3.5. Determination of the Flow Rate

2.4. Validation

2.4.1. Selectivity

2.4.2. Linearity

2.4.3. Limit of Detection (LOD) and Limit of Quantification (LOQ)

2.4.4. System Suitability

2.4.5. Method Precision

2.4.6. Accuracy

2.4.7. Robustness

2.4.8. Stability study

2.5. The HPLC–UV conditions for sample analysis

2.6. Application to Hydrogels' Characterization

2.6.1. Sample Preparation

2.6.2. Drug Loading Capacity (DL) and Drug Entrapment Efficiency (DEE%) of the Formulations

2.6.3. In vitro Drug Release Studies and Drug Release Kinetics

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussions

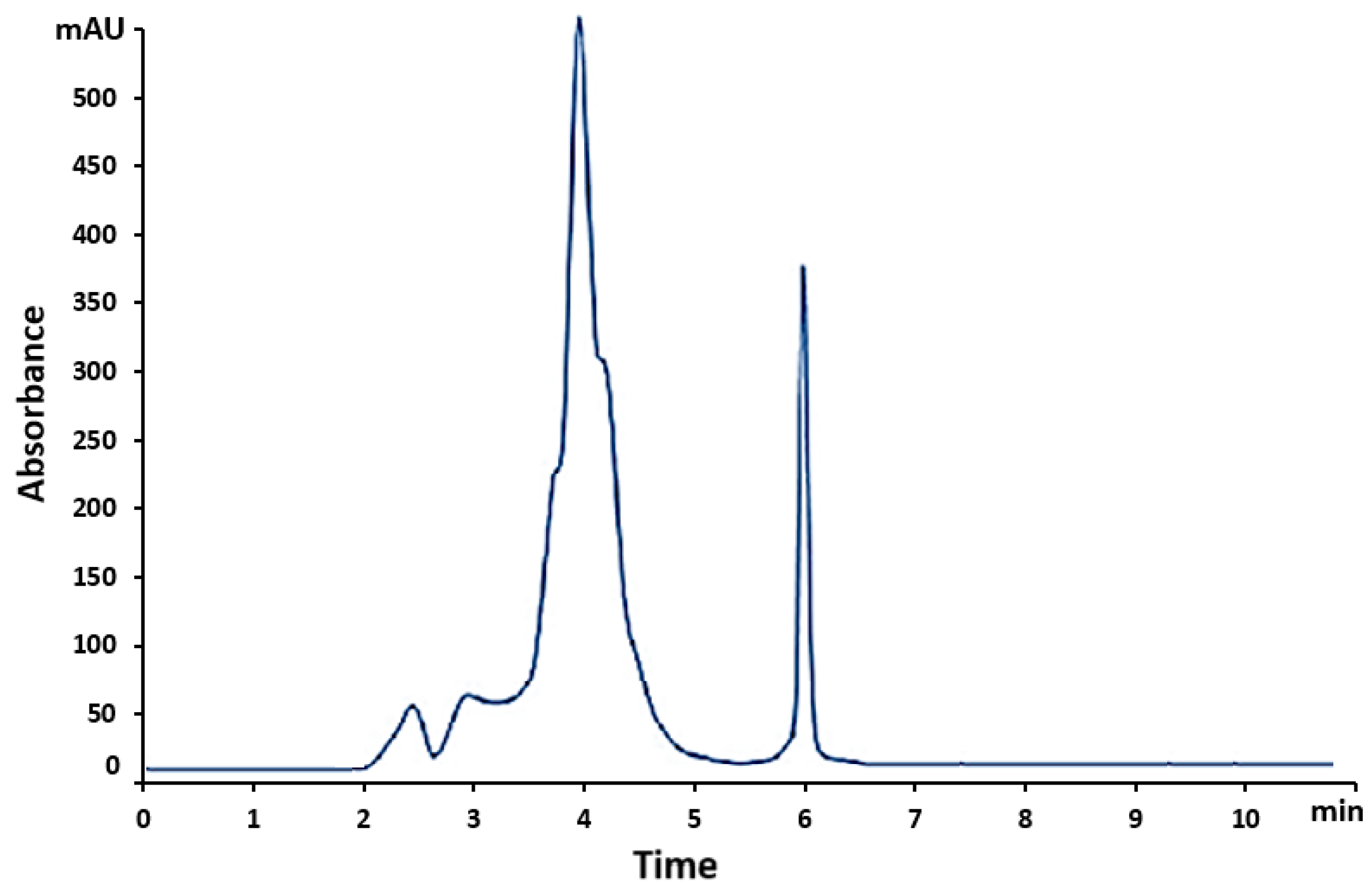

3.1. Optimization of Chromatographic Conditions

3.2. Validation

3.2.1. Selectivity

3.2.2. System Suitability

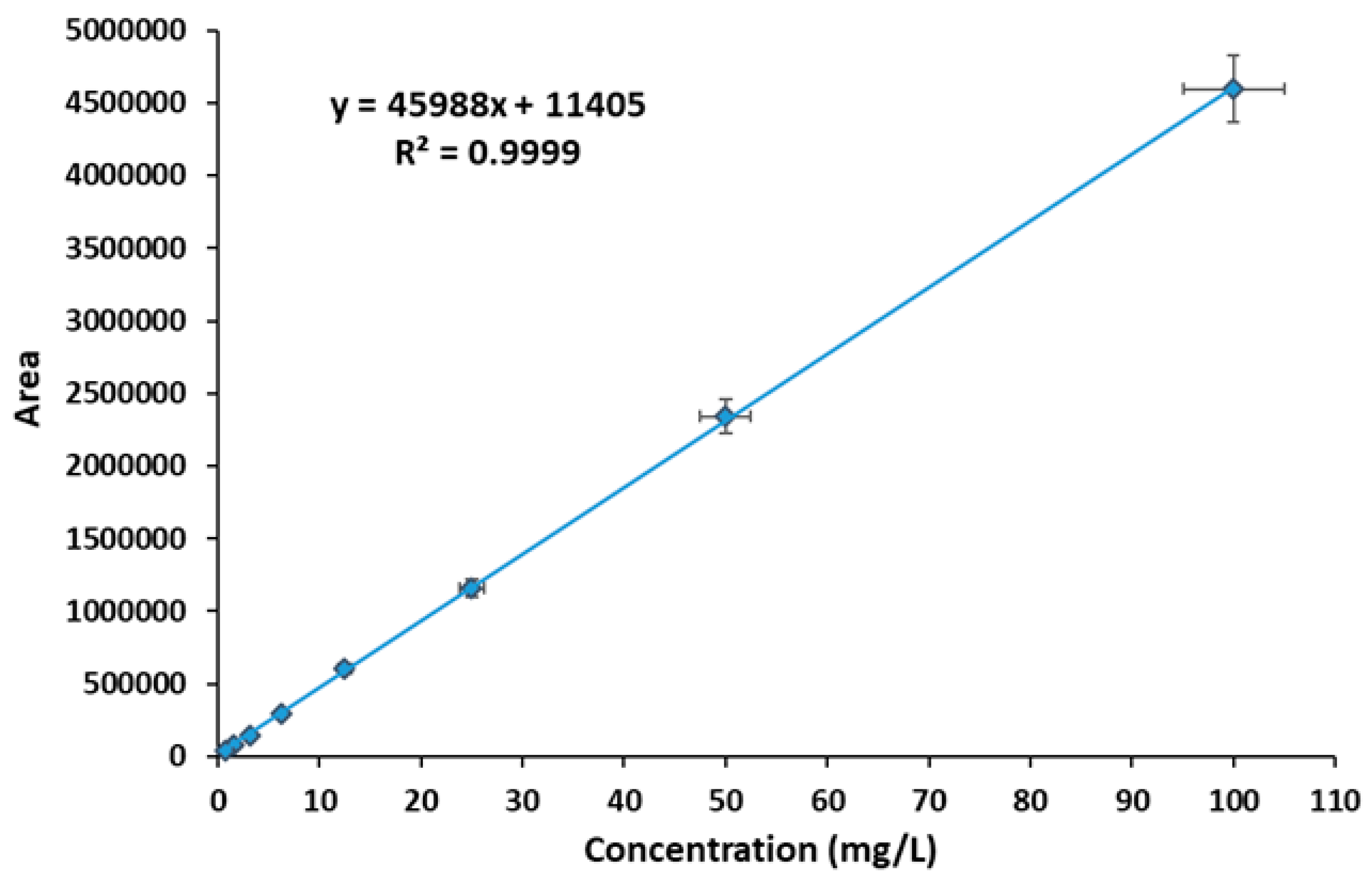

3.2.3. Linearity, LOD, LOQ

3.2.4. Intra- and Inter-Day Accuracy and Precision

3.2.5. Robustness

3.2.6. VEM Solution's Stability

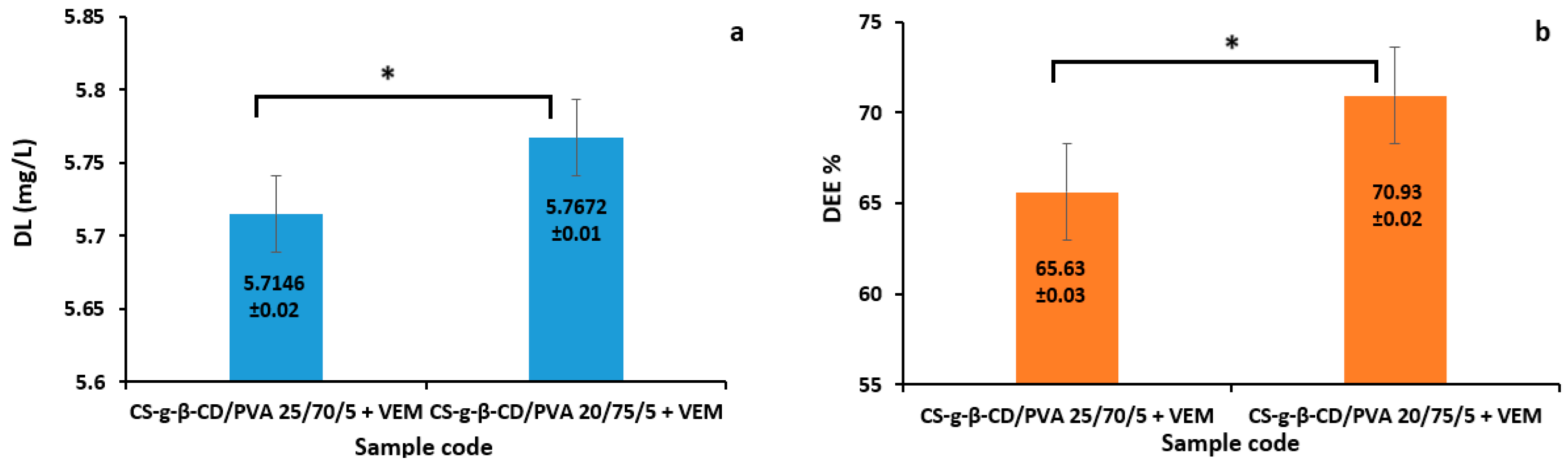

3.2.7. The Capacity of Hydrogels in Loading and Releasing VEM

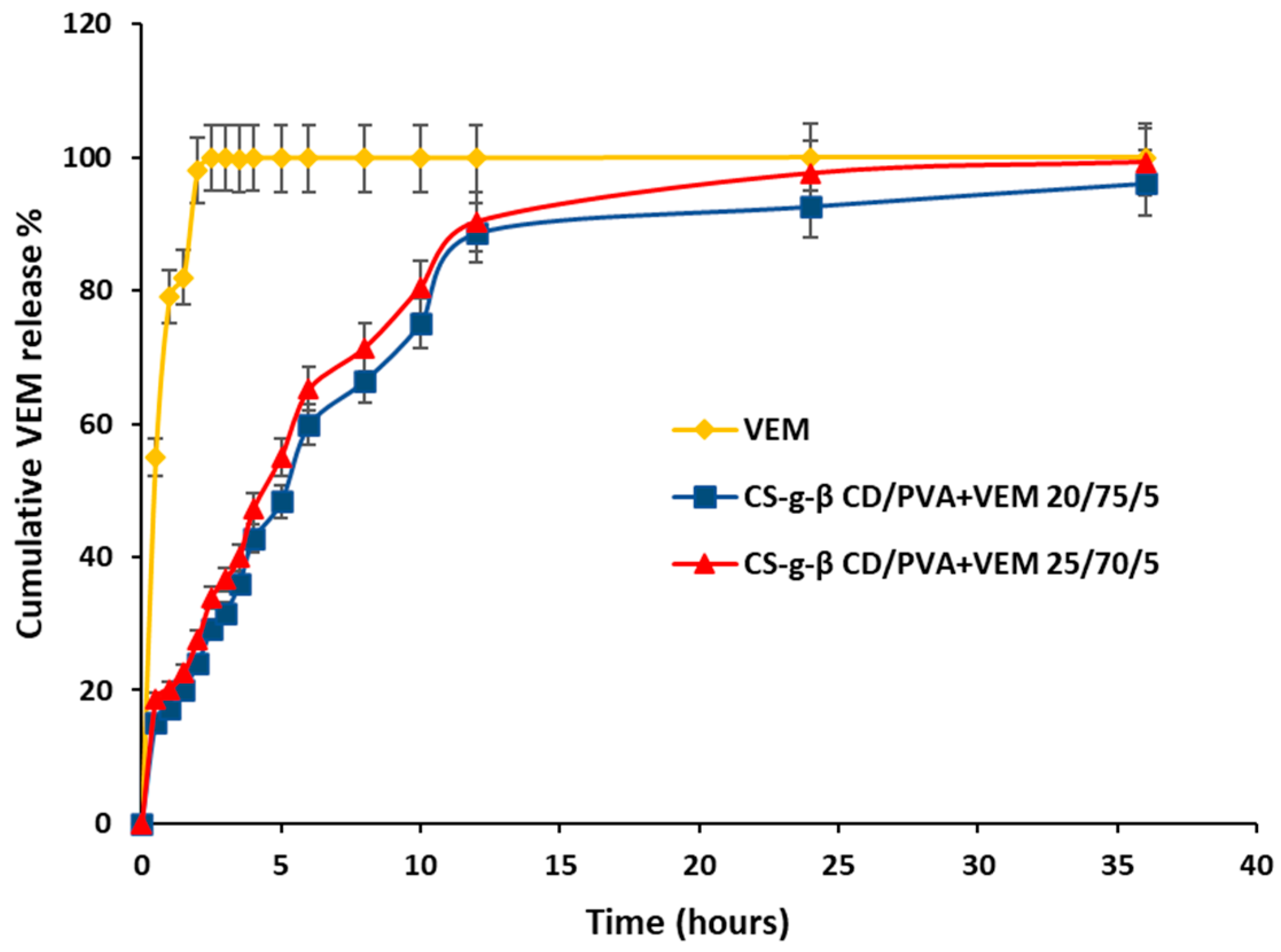

3.2.8. In Vitro Drug Release Analysis

3.2.9. Kinetics of In Vitro Drug Release Study

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Richard, M.A.; Paul, C.; Nijsten, T.; Gisondi, P.; Salavastru, C.; Taieb, C.; Trakatelli, M.; Puig, L.; Stratigos, A. Prevalence of Most Common Skin Diseases in Europe: A Population-based Study. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2022, 36, 1088–1096. [CrossRef]

- Lopes, J.; Rodrigues, C.M.P.; Gaspar, M.M.; Reis, C.P. Melanoma Management: From Epidemiology to Treatment and Latest Advances. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14, 4652. [CrossRef]

- Koizumi, S.; Inozume, T.; Nakamura, Y. Current Surgical Management for Melanoma. J. Dermatol. 2024, 51, 312–323. [CrossRef]

- Alieva, M.; van Rheenen, J.; Broekman, M.L.D. Potential Impact of Invasive Surgical Procedures on Primary Tumor Growth and Metastasis. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 2018, 35, 319–331. [CrossRef]

- National Cancer Institute. Melanoma Treatment (PDQ®)–Health Professional Version. National Institutes of Health, 26 Apr. 2024. https://www.cancer.gov/types/skin/hp/melanoma-treatment-pdq (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Grynberg, S.; Stoff, R.; Asher, N.; Shapira-Frommer, R.; Schachter, J.; Haisraely, O.; Lawrence, Y.; Ben-Betzalel, G. Radiotherapy May Augment Response to Immunotherapy in Metastatic Uveal Melanoma Patients. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- D’Andrea, M.A.; Reddy, G.K. Systemic Antitumor Effects and Abscopal Responses in Melanoma Patients Receiving Radiation Therapy. Oncology 2020, 98, 202–215. [CrossRef]

- Pham, J.P.; Joshua, A.M.; da Silva, I.P.; Dummer, R.; Goldinger, S.M. Chemotherapy in Cutaneous Melanoma: Is There Still a Role? Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2023, 25, 609–621. [CrossRef]

- Haider, T.; Pandey, V.; Banjare, N.; Gupta, P.N.; Soni, V. Drug Resistance in Cancer: Mechanisms and Tackling Strategies. Pharmacol. Rep. 2020, 72, 1125–1151. [CrossRef]

- Knight, A.; Karapetyan, L.; Kirkwood, J.M. Immunotherapy in Melanoma: Recent Advances and Future Directions. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15, 1106. [CrossRef]

- da Rocha Dias, S.; Salmonson, T.; van Zwieten-Boot, B.; Jonsson, B.; Marchetti, S.; Schellens, J.H.M.; Giuliani, R.; Pignatti, F. The European Medicines Agency Review of Vemurafenib (Zelboraf®) for the Treatment of Adult Patients with BRAF V600 Mutation-Positive Unresectable or Metastatic Melanoma: Summary of the Scientific Assessment of the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use. Eur. J. Cancer 2013, 49, 1654–1661. [CrossRef]

- Oneal, P.A.; Kwitkowski, V.; Luo, L.; Shen, Y.L.; Subramaniam, S.; Shord, S.; Goldberg, K.B.; McKee, A.E.; Kaminskas, E.; Farrell, A.; et al. FDA Approval Summary: Vemurafenib for the Treatment of Patients with Erdheim-Chester Disease with the BRAF V600 Mutation. Oncologist 2018, 23, 1520–1524. [CrossRef]

- Russi, M.; Valeri, R.; Marson, D.; Danielli, C.; Felluga, F.; Tintaru, A.; Skoko, N.; Aulic, S.; Laurini, E.; Pricl, S. Some Things Old, New and Borrowed: Delivery of Dabrafenib and Vemurafenib to Melanoma Cells via Self-Assembled Nanomicelles Based on an Amphiphilic Dendrimer. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 180, 106311. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Archer, P.A.; Manspeaker, M.P.; Avecilla, A.R.C.; Pollack, B.P.; Thomas, S.N. Sustained Release Hydrogel for Durable Locoregional Chemoimmunotherapy for BRAF-Mutated Melanoma. J. Control. Release 2023, 357, 655–668. [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.; Ding, W.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, S.; Li, F.; Ruan, R.; Wei, P.; Qiu, B. Peptide-Modified Vemurafenib-Loaded Liposomes for Targeted Inhibition of Melanoma via the Skin. Biomaterials 2018, 182, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Bîrsan, M.; Cristofor, A.C.; Antonoaea, P.; Todoran, N.; Bibire, N.; Panainte, A.D.; Vlad, R.A.; Grigore, M.; Ciurba, A. Evaluation of Miconazole Nitrate Permeability through Biological Membrane from Dermal Systems. Farmacia 2020, 68, 111–115. [CrossRef]

- Almajidi, Y.Q.; Maraie, N.K.; Raauf, A.M.R. Modified Solid in Oil Nanodispersion Containing Vemurafenib-Lipid Complex-in Vitro/in Vivo Study. F1000Res 2022, 11, 841. [CrossRef]

- Alkilani, A.; McCrudden, M.T.; Donnelly, R. Transdermal Drug Delivery: Innovative Pharmaceutical Developments Based on Disruption of the Barrier Properties of the Stratum Corneum. Pharmaceutics 2015, 7, 438–470. [CrossRef]

- Almajidi, Y.Q.; Maraie, N.K.; Raauf, A.M.R. Utilization of Solid in Oil Nanodispersion to Prepare a Topical Vemurafenib as Potential Delivery System for Skin Melanoma. Appl. Nanosci. (Switzerland) 2023, 13, 2845–2856. [CrossRef]

- Alex, M.; Alsawaftah, N.M.; Husseini, G.A. State-of-All-the-Art and Prospective Hydrogel-Based Transdermal Drug Delivery Systems. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2926. [CrossRef]

- Jacob, S.; Nair, A.B.; Shah, J.; Sreeharsha, N.; Gupta, S.; Shinu, P. Emerging Role of Hydrogels in Drug Delivery Systems, Tissue Engineering and Wound Management. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 357. [CrossRef]

- Esmaeili, J.; Barati, A.; Ai, J.; Nooshabadi, V.T.; Mirzaei, Z. Employing Hydrogels in Tissue Engineering Approaches to Boost Conventional Cancer-Based Research and Therapies. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 10646–10669. [CrossRef]

- Caccavo, D.; Cascone, S.; Lamberti, G.; Barba, A.A. Controlled Drug Release from Hydrogel-Based Matrices: Experiments and Modeling. Int. J. Pharm. 2015, 486, 144–152. [CrossRef]

- Păduraru, L.; Panainte, A.-D.; Peptu, C.-A.; Apostu, M.; Vieriu, M.; Bibire, T.; Sava, A.; Bibire, N. Smart Drug Delivery Systems Based on Cyclodextrins and Chitosan for Cancer Therapy. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2025, 18. [CrossRef]

- Chuah, L.-H.; Loo, H.-L.; Goh, C.F.; Fu, J.-Y.; Ng, S.-F. Chitosan-Based Drug Delivery Systems for Skin Atopic Dermatitis: Recent Advancements and Patent Trends. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2023, 13, 1436–1455. [CrossRef]

- Chander, S.; Piplani, M.; Waghule, T.; Singhvi, G. Role of Chitosan in Transdermal Drug Delivery. In Chitosan in Drug Delivery; Elsevier, 2022; pp. 83–105.

- Ketabchi, N.; D.R.; A.M.; G.M.; F.S.; A.B.; F.-M.R. Study of Third-Degree Burn Wounds Debridement and Treatment by Actinidin Enzyme Immobilized on Electrospun Chitosan/PEO Nanofibers in Rats. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 2020, 11, 10358–10370. [CrossRef]

- Tiplea, R.E.; Lemnaru, G.M.; Trușcă, R.D.; Holban, A.; Kaya, M.G.A.; Dragu, L.D.; Ficai, D.; Ficai, A.; Bleotu, C. Antimicrobial Films Based on Chitosan, Collagen, and Zno for Skin Tissue Regeneration. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 2021, 11, 11985–11995. [CrossRef]

- Nieto González, N.; Rassu, G.; Cossu, M.; Catenacci, L.; Sorrenti, M.L.; Cama, E.S.; Serri, C.; Giunchedi, P.; Gavini, E. A Thermosensitive Chitosan Hydrogel: An Attempt for the Nasal Delivery of Dimethyl Fumarate. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 278. [CrossRef]

- Naeem, A.; Chengqun, Y.; Hetonghui; Zhenzhong, Z.; Weifeng, Z.; Yongmei, G. β-Cyclodextrin/Chitosan-Based (Polyvinyl Alcohol-Co-Acrylic Acid) Interpenetrating Hydrogels for Oral Drug Delivery. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 242, 125149. [CrossRef]

- Najm, A.; Niculescu, A.-G.; Bolocan, A.; Rădulescu, M.; Grumezescu, A.M.; Beuran, M.; Gaspar, B.S. Chitosan and Cyclodextrins—Versatile Materials Used to Create Drug Delivery Systems for Gastrointestinal Cancers. Pharmaceutics 2023, 16, 43. [CrossRef]

- Tian, B.; Hua, S.; Liu, J. Cyclodextrin-Based Delivery Systems for Chemotherapeutic Anticancer Drugs: A Review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 232, 115805. [CrossRef]

- Kali, G.; Haddadzadegan, S.; Bernkop-Schnürch, A. Cyclodextrins and Derivatives in Drug Delivery: New Developments, Relevant Clinical Trials, and Advanced Products. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 324, 121500. [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.H.; Lee, J.S.; Yang, D.H.; Nah, H.; Min, S.J.; Lee, S.Y.; Yoo, J.H.; Chun, H.J.; Moon, H.-J.; Hong, Y.K.; et al. Development of a Temperature-Responsive Hydrogel Incorporating PVA into NIPAAm for Controllable Drug Release in Skin Regeneration. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 44076–44085. [CrossRef]

- Manohar, D.; Babu, R.S.; Vijaya, B.; Nallakumar, S.; Gobi, R.; Anand, S.; Nishanth, D.S.; Anupama, A.; Rani, M.U. A Review on Exploring the Potential of PVA and Chitosan in Biomedical Applications: A Focus on Tissue Engineering, Drug Delivery and Biomedical Sensors. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 283, 137318. [CrossRef]

- Panainte, A.-D.; Popa, G.; Pamfil, D.; Butnaru, E.; Vasile, C.; Tarțău, L.M.; Gafițanu, C. In Vitro Characterization Of Polyvinyl Alcohol/ Chitosan Hydrogels As Modified Release Systems For Bisoprolol. Farmacia 2018, 66, 1.

- Păduraru, L.; Sava, A.; Orhan, H.; Yilmaz, C.N.; Apostu, M.; Panainte, A.D.; Vieriu, M.; Atmaca, K.; Bibire, N. Vemurafenib Based Hydrogels As Potential Topical Bioformulations For The Treatment Of Melanoma. Med. Surg. J.-Rev. Med. Chir. Soc. Med. Nat 2025, 129, 278–290. [CrossRef]

- Sparidans, R.W.; Durmus, S.; Schinkel, A.H.; Schellens, J.H.M.; Beijnen, J.H. Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometric Assay for the Mutated BRAF Inhibitor Vemurafenib in Human and Mouse Plasma. J. Chromatogr. B 2012, 889–890, 144–147. [CrossRef]

- Vakhariya, R.-R.; Shah, R.-R.; Patil, S.-S.; Salunkhe N.-S.; Mohite, S.K. Development and Validation of Analytical Method for Vemurafenib. Int. J. Curr. Sci. 2024, 14, 519–529.

- Pawanjeet. J. Chhabda, M.B.S.V. and 2K. M.Ch.A.R. Development and Validation of a New Simple and Stability Indicating RP-HPLC Method for the Determination of Vemurafenib in Presence of Degradant Products . Der Pharma Chemica 2013, 5, 189–198.

- Nijenhuis, C.M.; Rosing, H.; Schellens, J.H.M.; Beijnen, J.H. Development and Validation of a High-Performance Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry Assay Quantifying Vemurafenib in Human Plasma. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2014, 88, 630–635. [CrossRef]

- Ravix, A.; Bandiera, C.; Cardoso, E.; Lata-Pedreira, A.; Chtioui, H.; Decosterd, L.A.; Wagner, A.D.; Schneider, M.P.; Csajka, C.; Guidi, M. Population Pharmacokinetics of Trametinib and Impact of Nonadherence on Drug Exposure in Oncology Patients as Part of the Optimizing Oral Targeted Anticancer Therapies Study. Cancers (Basel) 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Rousset, M.; Titier, K.; Bouchet, S.; Dutriaux, C.; Pham-Ledard, A.; Prey, S.; Canal-Raffin, M.; Molimard, M. An UPLC-MS/MS Method for the Quantification of BRAF Inhibitors (Vemurafenib, Dabrafenib) and MEK Inhibitors (Cobimetinib, Trametinib, Binimetinib) in Human Plasma. Application to Treated Melanoma Patients. Clin. Chim. Acta 2017, 470, 8–13. [CrossRef]

- Zhen, Y.; Thomas-Schoemann, A.; Sakji, L.; Boudou-Rouquette, P.; Dupin, N.; Mortier, L.; Vidal, M.; Goldwasser, F.; Blanchet, B. An HPLC-UV Method for the Simultaneous Quantification of Vemurafenib and Erlotinib in Plasma from Cancer Patients. J. Chromatogr. B 2013, 928, 93–97. [CrossRef]

- Shah, N.; Iyer, R.M.; Mair, H.-J.; Choi, D.; Tian, H.; Diodone, R.; Fahnrich, K.; Pabst-Ravot, A.; Tang, K.; Scheubel, E.; et al. Improved Human Bioavailability of Vemurafenib, a Practically Insoluble Drug, Using an Amorphous Polymer-Stabilized Solid Dispersion Prepared by a Solvent-Controlled Coprecipitation Process. J. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 102, 967–981. [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, J.-C.; Funck-Brentano, E.; Abe, E.; Etting, I.; Saiag, P.; Knapp, A. A LC/MS/MS Micro-Method for Human Plasma Quantification of Vemurafenib. Application to Treated Melanoma Patients. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2014, 97, 29–32. [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Food and Drug Administration (FDA); Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER); Center for Veterinary Medicine (CVM). Bioanalytical Method Validation Guidance for Industry Biopharmaceutics Contains Nonbinding Recommendations, 2018.

- Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use ICH Q2(R2). Guideline on Validation of Analytical Procedures, 2023;

- Panainte, A.D.; Vieriu, M.; Tantaru, G.; Apostu, M.; Bibire, N. Fast HPLC Method for the Determination of Piroxicam and Its Application to Stability Study. Revista de Chimie 2017, 68, 701–706. [CrossRef]

- Moosavi, S.M.; Ghassabian, S. Linearity of Calibration Curves for Analytical Methods: A Review of Criteria for Assessment of Method Reliability. In Calibration and Validation of Analytical Methods - A Sampling of Current Approaches; InTech, 2018.

- European Pharmacopoeia, 7th edition. Chapter 4.1.3. Buffer Solutions, , Council of Europe, Strasbourg, 2010, pp. 489-494.;

- Kaufmann, A.; Butcher, P.; Maden, K.; Walker, S.; Widmer, M.; Kaempf, R. Improved Method Robustness and Ruggedness in Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry by Increasing the Acid Content of the Mobile Phase. J. Chromatogr. A 2024, 1717, 464694. [CrossRef]

- International Conferences on Harmonization of Technical requirements for the registration of Drugs for Human use (ICH) Q2B. Validation of Analytical Procedure; Methodology, 2003;

- S. Lakka, N.; Kuppan, C. Principles of Chromatography Method Development. In Biochemical Analysis Tools - Methods for Bio-Molecules Studies; IntechOpen, 2020.

- Handbook of Pharmaceutical Analysis by HPLC; Satinder Ahuja, Michael W. Dong, Eds.; 1st ed.; Academic Press, 2005, 6.

- Almpani, S.; Agiannitou, P.-I.; Monou, P.K.; Kamaris, G.; Markopoulou, C.K. Development of a Validated HPLC-UV Method for the Determination of Panthenol, Hesperidin, Rutin, and Allantoin in Pharmaceutical Gel-Permeability Study. Separations 2025, 12, 19. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Thomas-Schoemann, A.; Sakji, L.; Boudou-Rouquette, P.; Dupin, N.; Mortier, L.; Vidal, M.; Goldwasser, F.; Blanchet, B. An HPLC-UV Method for the Simultaneous Quantification of Vemurafenib and Erlotinib in Plasma from Cancer Patients. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2013, 928, 93–37. [CrossRef]

- Nilima, S.; Pragati Ranjan, S.; Madhu Chhanda, M.; Bisakha, T.; Bhavna, G. A New Analytical Rp-Hplc Method For The Estimation Of Vemurafenib In Pure Form And Marketed Pharmaceutical Dosage Form. Der Pharma Chemica 2023. [CrossRef]

- Gioacchino Luca Losacco; Amandine Dispas; Jean-Luc Veuthey and Davy Guillarme. Chapter 2 - Application Space for SFC in Pharmaceutical Drug Discovery and Development. In Practical Application of Supercritical Fluid Chromatography for Pharmaceutical Research and Development; Michael Hicks, Paul Ferguson, Eds.; 2022; Vol. 14, pp. 29–47.

- Neamah, M.J.; Al-Akkam, E.J.M. Preparation and Characterization of Vemurafenib Microemulsion Based Hydrogel Using Surface Active Ionic Liquid. Pharmacia 2024, 71, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Zhang, X.; Gao, Y.; Wang, S.; Ning, Y. Robust Total Least Squares Estimation Method for Uncertain Linear Regression Model. Mathematics 2023, 11, 4354. [CrossRef]

- Güven, G. Development and Validation of a RP-HPLC Method for Vemurafenib in Human Urine. Lat. Am. J. Pharm. 2019. 38 (4): 1-5.

- Anusha, D.; Yasodha, A. and Venkatesh, M.-V. A New Analytical RP-HPLC Method for the Estimation of Vemurafenib in Pure Form and Marketed Pharmaceutical Dosage Form. Tijer - International Research Journal 2023, 10.

- The United States Pharmacopeial Convention. USP34 – NF29, Volume 1. Rockville, Maryland, 2011.

- Bibire, T.; Panainte, A.-D.; Yilmaz, C.N.; Timofte, D.V.; Dănilă, R.; Bibire, N.; Păduraru, L.; Ghiciuc, C.M. Dexketoprofen-Loaded Alginate-Grafted Poly(N-Vinylcaprolactam)-Based Hydrogel for Wound Healing. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26, 3051. [CrossRef]

- Peppas, N.A.; Narasimhan, B. Mathematical Models in Drug Delivery: How Modeling Has Shaped the Way We Design New Drug Delivery Systems. Journal of Controlled Release 2014, 190, 75–81. [CrossRef]

- Grassi, M.; Grassi, G. Application of Mathematical Modeling in Sustained Release Delivery Systems. Expert Opin Drug Deliv 2014, 11, 1299–1321. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, N.; Ortiz, A.C.; Jerez, A.; Morales, J.; Arriagada, F. Kinetics and Mechanism of Camptothecin Release from Transferrin-Gated Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles through a PH-Responsive Surface Linker. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1590. [CrossRef]

- Ata, S.; Rasool, A.; Islam, A.; Bibi, I.; Rizwan, M.; Azeem, M.K.; Qureshi, A. ur R.; Iqbal, M. Loading of Cefixime to PH Sensitive Chitosan Based Hydrogel and Investigation of Controlled Release Kinetics. Int J Biol Macromol 2020, 155, 1236–1244. [CrossRef]

- Raina, N.; Pahwa, R.; Bhattacharya, J.; Paul, A.K.; Nissapatorn, V.; de Lourdes Pereira, M.; Oliveira, S.M.R.; Dolma, K.G.; Rahmatullah, M.; Wilairatana, P.; et al. Drug Delivery Strategies and Biomedical Significance of Hydrogels: Translational Considerations. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 574. [CrossRef]

|

System Suitability Parameter |

Acceptance Criteria |

Results |

| Injection Precision for Retention Time (Min) | RSD ≤ 1% | RSD = 0.97 |

| Injection Precision for Peak Area | RSD ≤ 1% | RSD = 0.91 |

| USP Tailing Factor (T) | T ≤ 2.0 | 1.15*±0.06 |

| Capacity Factor (K) | K ≥ 2.0 | 7.02*±0.15 |

| Theoretical Plates (N) | N ≥ 2000 | 5562*±0.02 |

| No. |

VEM (mg/L) |

Area mean ± SD (n= 3) |

| 1. | 0.78 | 37776 |

| 2. | 1.5625 | 78257 |

| 3. | 3.125 | 146193 |

| 4. | 6.25 | 291083 |

| 5. | 12.5 | 606229 |

| 6. | 25 | 1158865 |

| 7. | 50 | 2339810 |

| 8. | 100 | 4594650 |

| Theoretical conc. of VEM (mg/L) | Accuracy | Precision | ||||

| Mean recovered conc. of VEM | Mean % recovery |

Intra-day | Inter-day | |||

| Mean*±SD | %RSD | Mean*±SD | %RSD | |||

| 40 | 39.78 | 99.45 | 40.98±0.3141 | 0.71 | 41.08±0.3401 | 0.68 |

| 50 | 50.05 | 100.10 | 50.12±0.2856 | 0.67 | 50.06±0.2536 | 0.63 |

| 75 | 75.01 | 100.01 | 75.08±0.3452 | 0.78 | 75.02±0.3452 | 0.73 |

| Parameter | Variation | Retention time (min) | Theoretical Plates | Tailing Factor |

|

Flow Rate |

0.8 mL/min | 6.23 | 5492 | 1.08 |

| 1 mL/min | 6.01 | 5547 | 1.12 | |

| 1.2 mL/min | 5.98 | 5562 | 1.12 | |

|

Wavelength |

250 nm | 6.03 | 5649 | 1.11 |

| 252 nm | 6.01 | 5598 | 1.10 | |

| 254 nm | 5.99 | 5697 | 1.06 | |

|

Temperature |

38°C | 6.02 | 5789 | 1.13 |

| 40°C | 6.00 | 5856 | 1.02 | |

| 42°C | 6.02 | 5698 | 1.03 |

| Conditions | High concentration | Low concentration |

| 24 h at ambient temperature | 101.5 ± 1.3 | 93.7 ± 0.6 |

| 3 free-thaw cycles | 105.3 ± 1.6 | 94.8 ± 2.3 |

| 3 month -30°C | 102.5 ± 1.8 | 97.3 ± 3.8 |

| No. |

Stationary phase/ chromatographic column |

Mobile phase and flow rate |

Detection/ Tr |

Statistical parameters |

Practical application |

Ref. |

| 1 | Xterra® MS C8 (250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 µm) |

glycine buffer (pH 9.0, 100 mM) : acetonitrile (45:55, v/v) 0.9 mL/min |

249 nm 6.3 min |

*DL = 1.25-100 mg/L LOQ = 1.25 mg/L r2 = 0.99 Recovery = 99,1% |

mouse plasma | [57] |

| 2 | X-Terra RP-18 (250 x 4.60 mm, ID 5 µm) | acetonitrile : water 60:40 (v/v) 1.0 mL/min |

249 nm 6.69 min |

DL = 2-10.0 mg/mL LOQ = 0.146 mg/L r2 = 0.9999 Recovery = 100.1- 102.33% |

human urine | [62] |

| 3 | Acquity UPLC® BEH C18 (30 mm × 2.1 mm, 1.7 µm) |

0.1% (v/v) formic acid in water (10%, v/v) : water (20%, v/v) : methanol (70%, v/v) 0.6 mL/min |

MS m/z 490.1→255.05 | DL = 0.1–100 mg/L LOQ = 0,1 mg/mL r2 = 0.9996 Recovery = 99-106% |

human and mouse plasma | [38] |

| 4 | Symmetry C18 (4.6 mm × 150 mm, 5 μm) |

methanol : water (45:55, v/v) 1.0 mL/min |

260 nm 2.379 min |

DL = 24-120 mg/L LOQ = 16.7 mg/mL r2 = 0.998 Recovery = 99.4-99.9% |

in pure form and dosage forms | [58] |

| 5 | Symmetry ODS C18 (4.6 x 250 mm, 5 μm) |

acetonitrile : methanol (80:20, v/v) 1.0 mL/min |

272 nm 3.15 min |

DL = 10-50 mg/L LOQ = 3.2 mg/L r2 = 0.999 Recovery = 98.0-102% |

in pure form and dosage forms | [63] |

| 6 | Acquity UPLC BEH C18 column (2.1 × 50 mm, 1.7 mm) |

10 mM ammonium acetate in water (A) and methanol (B) with applied phase gradient: 50–80% B (0.0–0.5 min), 80% B (0.5–2.5 min), 80–95% B (2.5–2.6 min), 95% B (2.6–3.6 min), 95–40% B (3.6–3.7 min), 50% B (3.7–7.0 min). 0.25 mL/min |

MS m/z 488.2 → 381.0 3.4 min |

DL = 1.0 -100.0 mg/L LOQ = 0.1mg/mL r2 = 0.9985 |

human plasma |

[41] |

| 7 | Waters CORTECS C18 column (2.1 × 100 mm, 2.7 μm) | water/formic acid - (99.9/0.1, v/v) : acetonitrile : methanol 40:55:5 (v/v/v) 1.0 mL/min |

252 nm 6 min |

DL = 0.78-100 mg/L LOQ = 0.75 mg/L Recovery = 99,45-100.0% r2 = 0.9999 |

hydrogels |

The propo- sed method |

| Kinetic Model | Parameters | Sample | |

| CS-g-β-CD/PVA 25/70/5 | CS-g-β-CD/PVA 20/75/5 | ||

| Zero order | K0 | 4.588 | 4.302 |

| r2 | 0.668 | 0.496 | |

| AIC | 148.420 | 144.043 | |

| First order | K | 0.155 | 0.156 |

| r2 | 0.895 | 0.839 | |

| AIC | 6.887 | 14.342 | |

| Higuchi | KH | 27.513 | 29.468 |

| r2 | 0.923 | 0.865 | |

| AIC | 125.549 | 134.365 | |

| Korsmeyer–Peppas | KP | 45.991 | 48.097 |

| n | 0.372 | 0.293 | |

| r2 | 0.958 | 0.897 | |

| AIC | 103.589 | 108.123 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).