1. Introduction

A comprehensive introduction to the subject of variational principles of fluid dynamics is given in [

1] and will not be reproduced here, the reader who is interested in a broader introduction is referred to the original paper. We shall mention, however, that parts of this paper especially

Section 5 follows closely the work of Salmon [

2] (

Section 3).

In this paper we extend what it known on variational barotropic fluid dynamics to non-barotropic fluid dynamics, this has also impact on the form of conserved quantities such as circulation and helicity which have a well known topological meaning in terms of the knottiness of vortex lines [

3].

Non-barotropic flows are distinguished from Barotropic flows by their more realistic equation of state. The internal energy of those flows and therefore the pressure, depend on both the density and specific entropy in contrast to the (over)simplified equation of state of a Barotropic flow which is a function of density alone. This allows us to discuss the effect of entropy and temperature on the dynamics of the flow and points the way to further developments towards the variational analysis of non ideal flows in which heat losses play an important rule.

We start by introducing the basic equations, this is followed by a discussion of a fluid Lagrangian variational action. Then we discuss the Eulerian variational principle and its simplification, including its stationary form. This is followed by the definition of canonical momenta and derivation of the Hamiltonian of the system. The next step is the analysis of conservation laws within the Non-Barotropic framework. Then we demonstrate that the non-barotropic variational problem can be formulated in terms of only four functions. Finally, we give an analytic solution of a family of flows which include also self gravitating torii.

2. Fundamental Equations of Non-Stationary Non-Barotropic Fluid Dynamics

Non-Barotropic Eulerian flows are described using five dependent variables the density

, velocity

, and specific entropy

s. Those variables satisfy the continuity and Euler equations and ideal flows requirement, which is the lack of heat losses in every fluid element:

The pressure function

is dependent on the density and specific entropy

s,

is some specific force potential (which can be gravitational or electromagnetic),

is a partial time derivative,

is the nabla operator of vector analysis. The derivative

is the material time derivative. Equation (

1) tells us that the mass of each fluid element is conserved, Equation (

2) is just Newton’s second law for continuous matter, while Equation (

3) is a mathematical expression for the fact that in an ideal flow, heat is not conducted, nor created but only convected.

3. Thermodynamics & Vortex Dynamics

Applying the rotor operator to Equation (

2) will lead to:

in which:

is the vorticity. Let us now look at the thermodynamics of the fluid. The fluid consists of "fluid elements," [

4,

5] which are conceptualized as "point particles" with certain properties. Each "fluid element" has an infinitesimal mass

, a position vector

, and a velocity

. Unlike true point particles, these fluid elements also possess an infinitesimal volume

, an infinitesimal amount of entropy

, and an infinitesimal internal energy

. It is common practice to define densities for the Lagrangian, mass, and charge of each fluid element in this context:

The density is dependent on

, where the "fluid element" labelled

is in time

t:

It is also common practice to define the specific internal energy

:

which will be important later in the current paper. In an ideal case the "fluid element" does not exchange mass nor heat with other fluid elements, thus:

in which we use the

symbol to denote change. According to thermodynamics a modification of a "fluid element" internal energy satisfies:

the first term in the right hand side of the above equation describes the heat gained by the "fluid element" while the second term in the right hand side is the work done by the "fluid element" on surrounding elements. In the above

denotes the temperature of the "fluid element" and

is its pressure. As the mass of the fluid element is constant we may divide Equation (

10) by

to derive the variation of the specific energy:

is the specific entropy. Thus:

The Enthalpy is defined as:

and thus the specific enthalpy can be calculate as follows:

Thus using Equation (

12) we obtain:

Now we can look again at the gradient of the pressure appearing in Equation (

4):

in which we have used Equation (

15) in the above derivation. Looking again at Equation (

11) and considering a change of the fluid element location, leads to the following identity for the specific internal energy gradient:

Combining Equation (

17) with Equation (

18) leads to the equation:

We can now plug the above equation into Equation (

4) to obtain:

Equation (

4) is a mathematical statement about the vorticity lines being "frozen" in the flow if the temperature or specific entropy are uniform or their gradients are parallel. Frozen vorticity lines (or not) is obviously connected to the conservation of circulation and helicity and thus signifies the profound connection in flows between thermodynamics and vortex dynamics.

4. The Lagrangian Variational Approach

Lagrangian and action for every "fluid element" are the same as that of a point particle, with one difference: its internal energy. The variational formalism of point particles is described in

Appendix A. Thus according to Equation (

A6) we obtain the expression:

in which we replace the discrete index

j with the continuous index

. Of course, all quantities are calculated for a unique

. The fluid’s Lagrangian and action is summed (or integrated) over all

’s:

It follows that the Lagrangian density is:

The Lagrangian is thus a spatial integral:

We shall now vary the action. The only term different from the classical case is the internal energy term whose variation is given in Equation (

10). For an ideal fluid, heat is not generated, nor heat is conducted or radiated, and thus heat can only be convected by the "fluid elements". It follows that

and thus:

We now vary a volume element:

With the help of the Jacobian we relate this to the volume element at

:

. Now:

As both the actual and varied trajectories start at the same location. Varying

J we obtain:

Introducing the notation

it follows that:

And thus the variation of the volume of each "fluid element" is:

And thus the variation of the internal energy follows:

The internal energy is the main new aspect compared to the single particle or system of particles scenarios described in the appendix. Therefore, the rest of the variation analysis proceeds in a straightforward manner. Varying Equation (

21) we derive:

After the steps which lead to Equation (

A2) we obtain:

The variation of a single element action is thus:

From the above we easily derive the total action variation:

Now according to Equation (

6) we may write:

and thus convert the

integral into a volume integral:

According to the identity:

thus, with the help of Gauss theorem we write:

The action variation will vanish if

and the otherwise arbitrary

vanishes on a surface surrounding the fluid, only if the Euler equation is satisfied:

The equation, apart from the pressure terms, resembles that of a point particle. In experimental fluid dynamics, it’s often more practical to describe a fluid using quantities at specific locations rather than those associated with unseen infinitesimal "fluid elements." This approach leads to the Eulerian description of fluid dynamics, which focuses on flow fields rather than the velocities of individual "fluid elements" this will be investigated in

Section 5.

5. The Eulerian Variational Principle

The Eulerian approach is radically differen way to study flows. Instead of fluid elements we look at fluid fields which may be scalar, such as the density of mass

and the entropy per unit mass (specific entropy)

or vector such as the velocity field

. To this we will need to add auxiliary functions for maintaining information that is lost in the transformation from the Lagrangian to the Eulerian picture, such as the particles mass and identity. Here we follow in the footsteps of Clebsch [

6,

7], Davydov [

8] and Seliger & Whitham [

9]. We write the action:

in the above

is simply the Lagrangian density given in Equation (

23).

is composed from a set of constraints which are enforced by the Lagrange multipliers

. The

functions appear also in the barotropic variational formalism [

1], however, the

Lagrange multiplier is of course unique to non-barotropic flows and appears also in non-barotropic magnetohydrodynamics [

10,

11]. Variation with respect to

will obviously lead to:

For the case that

is not zero those are just the mass conservation Equation (

1) and the fact that

and

s are comoving, that is they do not change for any flow element. Varying the action with respect to

:

The boundary terms above include an integration over the external boundary

and an integral over a cut

that must be introduced when

is not single-valued, which will be discussed in later sections. The external boundary term becomes zero in cases of astrophysical flows where

on the free flow boundary, or when the fluid is contained in a vessel with a no-flux boundary condition

(where

is a unit vector normal to the boundary). The cut "boundary" term also vanishes if the velocity field only varies parallel to the cut, satisfying a Kutta-type condition. If these boundary terms are zero,

is of the following form:

this is a generalized Clebsch representation of the velocity (see for example [

4,

6,

7,

12] [page 248]). We now vary the action with respect to

:

Thus if

vanishes on the domain’s boundary, on the cut and in both initial and final times we obtain:

Let us vary with action with respect to

s:

in which the temperature is

is defined in Equation (

12). According to Equation (

47)

is single valued thus no cuts are needed. Using Equation (

45) we obtain for

locations:

if we require that

for arbitrary

.

Finally we vary

A with respect to

:

Thus if

is chosen such that both temporal and spatial boundary terms are null (

to be continuous on the cut if it is needed):

Using the mass conservation Equation (

1) we simply have:

Hence for every location in which

both

and

are comoving coordinates. The vorticity can be derived from equation (

47) :

Calculating

in which

is defined by Equation (

55) and using Equation (

54), Equation (

51) and Equation (

45) will yield Equation (

20). We mention that In particular the six Equations (

45), (

49), (

51), and (

54) are equivalent to Salmon’s [

2] six equations (3.18).

6. Euler’s Equations

Although we obtained from the variational principle the continuity and specific entropy conservation Equations (

1,

3) the rest of the variational equations seem unrelated to the Euler Equations (

2), however, this impression is false.

We shall now demonstrate that a velocity field given in the generalized Clebsch form of Equation (

47), in which the dependent variables

satisfy Equations (

45), (

49), (

51), (

54) satisfies Euler’s equations. We calculate

’s material derivative applying Equation (

51) and Equation (

54):

It can be easily shown using Equation (

45) and Equation (

49) that:

In the above

are Cartesian coordinates and Einstein’s summation convention is utilized. It follows from equation (

57) and Equation (

56) that:

in which we have used both Equation (

47) and Equation (

19). Thus Euler’s equations are derived from the action (

44) and thus all non-barotropic ideal fluid dynamics equations can be derived from the same action.

7. Simplified Eulerian Action

The reader might feel that the authors have unnecessarily complicated the theory of fluid dynamics by introducing four additional functions—

—alongside the standard variables

. However, we will demonstrate that this is not the case. The action given in equation Equation (

44) can indeed be simplified with respect to the number of unknown functions, making it more suitable for a pedagogical presentation. It’s straightforward to show that the Lagrangian density in Equation (

44) can be expressed as:

stands for

(see Equation (

47)). Thus

has three components:

The term

is the only one involving

, and it can be shown that this term will lead to the form given in Equation (

47) when the variational derivative is set to zero, without affecting other variational derivatives. It’s important to note that the term

consists only of complete partial derivatives, so it doesn’t contribute to the equations but can influence the boundary conditions. Thus, equations Equations (

45) , Equation (

49), Equation (

51), and Equation (

54) can be derived using the Lagrangian density

, where

replaces

in the relevant equations. After solving the six Equations (

45,

49,

51,

54), the functions

can be substituted into Equation (

47) to obtain the physical velocity

. This approach means that the general non-barotropic fluid dynamics problem can be approached by solving an alternative set of six equations, which can be derived from the Lagrangian density

, instead of the usual five Equations (

1,

2,

3). The potential

influences the flow dynamics through equation (

49), while thermodynamics impacts flow dynamics through two equations: (

49), which depends on the specific enthalpy

w, and (

51), which depends on the temperature

T. We mention that a variation principle based on

was already described by Salmon [

2] equation (3.16).

8. The Simplified Hamiltonian Formalism

Let us derive the conjugate momenta of the variables appearing in the Lagrangian density

defined in Equation (

60). A simple calculation will yield:

The rest of the canonical momenta

are null. It thus seems that the six functions appearing in the Lagrangian density

can be divided to "approximate" conjugate pairs:

. The Hamiltonian density

can be now calculated as follows:

in which

is defined in Equation (

47). This Hamiltonian density implies the Hamiltonian:

which is numerically identical to the Hamiltonian introduced by Salmon [

2] (2.18). However, in Salmon’s case the Hamiltonian is described in terms of a Lagrangian description of the fluid, while in our case the Hamiltonian density (and hence the Hamiltonian) are described by Eulerian variables. Hamilton’s equation would be the same six Equations (

45), (

49), (

51), and (

54).

9. Stationary Fluid Dynamics

Stationary flows are a distinctive feature of Eulerian fluid dynamics, which do not have an equivalent in Lagrangian fluid dynamics. In stationary flows, the physical fields

remain constant over time (but not over necessarily over space). However, this constancy doesn’t mean that the stationary potentials

are solely functions of spatial coordinates. In fact, if we were to assume that these potentials depend only on spatial coordinates, it would lead to incorrect conclusions, as the stationary equations of motion could not be derived from the Lagrangian density

provided in Equation (

60). To resolve this issue, we can proceed as follows: we should let

depend only on the spatial coordinates, while we select

in a specific manner:

depends only on the spatial coordinates. The Lagrangian density

of Equation (

60) is thus:

Varying

with respect to

and equating the variation of the action to null (assuming the relevant spatial and temporal boundary conditions) leads to a set of equations:

Which simplifies for any spatial point in which the fluid density is not null to:

is just the constant suggested by Bernoulli (see [

13]). Calculations essentially identical to the ones done previously show that the above equations are equivalent to stationary Euler equations:

10. Constants of Motion

A well known concept in fluid dynamics is circulation around a trajectory that is comoving with the flow:

is infinitesimal length oriented along the trajectory. It follows from Equation (

58): that:

hence circulation is not conserved unless the flow is barotropic (which means a uniform specific entropy throughout the flow), or the trajectory happens to be on a constant specific entropy or constant temperature surface. However, using the variational equations that we obtained in the previous sections we can generalized circulations conservation to an arbitrary comoving trajectory as follows. First we define a topological velocity field:

and

s are defined in previous sections. Next we define a circulation of the topological flow field in an analogue way to the definition of standard circulation:

It is easy to show that this quantity is conserved for any trajectory:

in which we have used Equation (

51) and Equation (

70). Taking into account the generalized Clebsch representation Equation (

47) it follows that:

Hence the topological flow field has a standard Clebsch form. Moreover, the associated vorticity of this flow is:

We can use Stokes theorem to write the topological circulation

as topological vorticity flux

through a comoving surface:

Hence a tube of topological vorticity lines will not change its flux due to the flow dynamics. This is of course true even in the cross section of the tube is infinitesimal, which means that each vortex line is comoving and thus the topology of the topological vortex lines is conserved as well, and they cannot be unknotted by the flow if they are initially knotted. This is of course the reason why they are called topological in the first place. It is easy to show using Equation (

45) and Equation (

54) that:

which is a sufficient condition for the topological vortex line to co-move with

. In barotropic fluid dynamics the helicity is a (topological) constant of motion;

which is a measure of the knottiness of lines for

[

3]. However, this quantity is not constant in non-barotropic flows. Nevertheless, previous discussion shows that this quantity can be easily generalized using the concept of topological flow fields and their topological vorticity:

A straightforward calculation will show that this is indeed conserved. We write Equation (

79) in terms of the potentials

, the scalar product

is:

We introduce local vector basis:

in which

is a comoving function with a gradient which is not parallel to either to

or

. Using those functions we can write

as:

Inserting equation (

82) into equation (

79) we obtain:

In certain situations, it might be necessary to divide the flow domain into separate regions or patches, each having different definitions for

. This division is not considered a limitation of our formalism, as the topology of the flow remains consistent with the flow equations. In such cases, the quantity

should be calculated by summing the contributions from each patch. We can envision the fluid domain as being composed of thin, closed tubes of topological vortex lines, each identified by the values of

. Integrating along these thin tubes in the metage direction yields the following result:

In this context,

represents the discontinuity of the function

along its cut. This means that if a thin tube of vortex lines exists where

is single-valued, it doesn’t contribute to the topological helicity integral. When we substitute the expression from the equation

into the helicity equation, we obtain the following result:

in which Equation (

72) was used. Thus:

The discontinuity of

represents the density of topological helicity per unit of topological vortex flux within a tube. This means that the Clebsch representation does not imply zero topological helicity; instead, it can accommodate non-zero topological helicity, as demonstrated above. Moreover, according to equation (

49) :

We can conclude that topological helicity is conserved not just as an overall quantity across the entire flow domain, but also that the local density of topological helicity per unit of topological vortex flux remains conserved.

11. A Simpler Variational Principle of Non-Stationary Fluid Dynamics

Lynden-Bell and Katz [

14] demonstrated that an Eulerian variational principle for non-stationary barotropic fluid dynamics could be expressed using just two functions: the density (

) and the load (

). However, the velocity was implicitly defined through a partial differential equation, and its variations were constrained by this equation. This approach has been similarly criticized in their work on non-barotropic flows [

15]. However, Yahalom & Lynden-Bell [

1] have shown that a true variational principle (that is unconstrained and without implicit definitions) for barotropic flows can be formulated in terms of three dependent variables

and an additional comoving dependent variable

. Here we show that for the non-barotropic flows four dependent variables will suffice those are

and an additional comoving function.

Consider the last two equations in (

45) and write them explicitly in term of the generalized Clebsch form defined in Equation (

47):

We thus derived two algebraic equations for the variables

that can readily be solved. Introducing the notation:

We obtain both

as functionals of the variables

:

In Hamiltonian language this means that the canonical momenta of

and

s are now given expressions of

:

Similarly the velocity field is now a functional of the three variables

:

Finally the Lagrangian density is a functional of the four variables

:

The variation of which will lead to the following four equations which replace the original set of equation (

1,

2,

3):

Written explicitly the form of those equations may look rather complicated.

12. Example: A Flow Solution in Circular Toroidal Coordinates

Consider a stationary fluid where both the velocity and vorticity lines are confined to toroidal surfaces [

16], defined as surfaces where the radial coordinate

remains constant. The cylindrical polar coordinates

are used to describe the position in space, with

being a function that defines these toroidal surfaces:

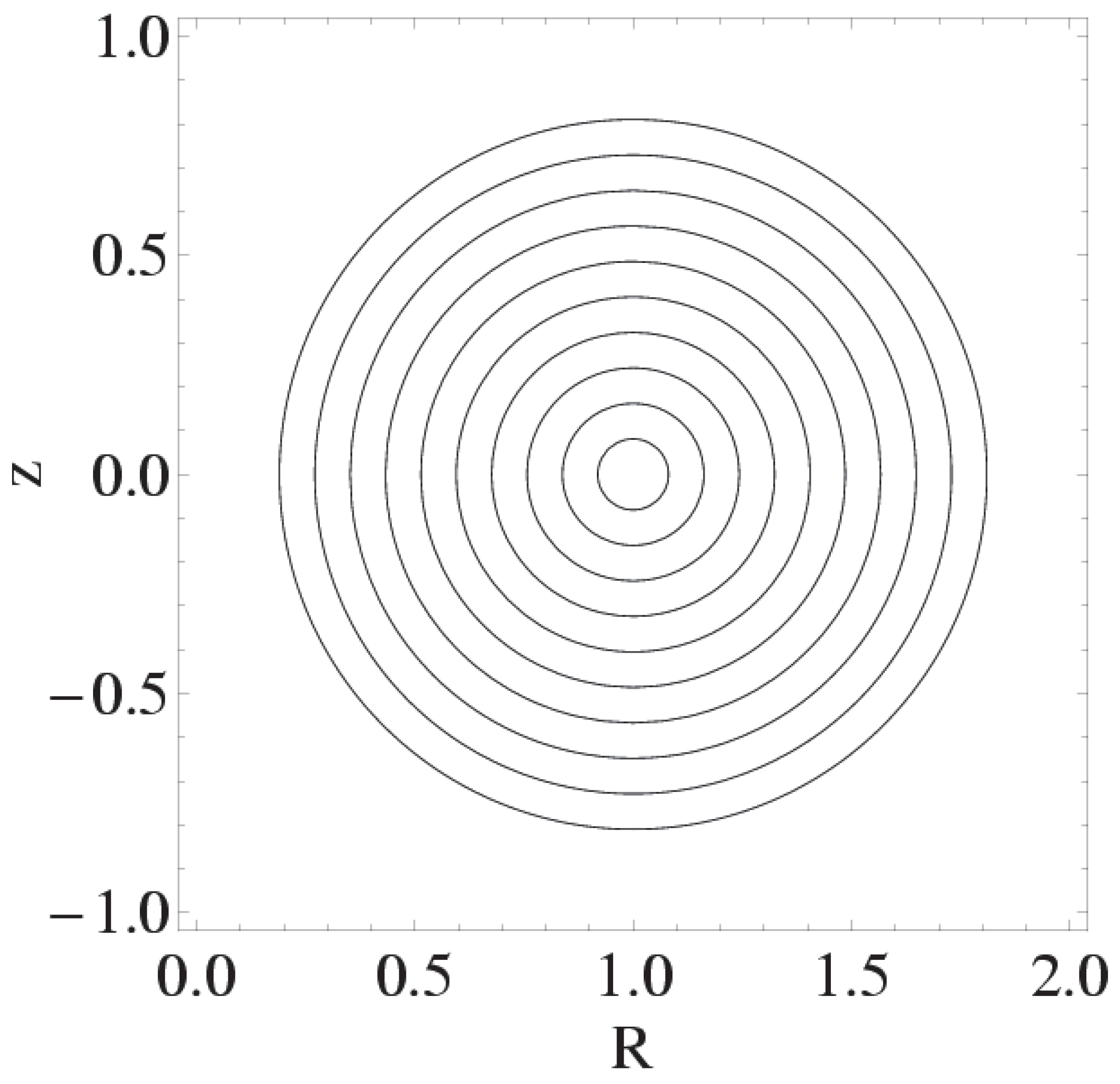

A visual representation of nested tori is depicted in

Figure 1. This cross-section shows how these toroidal surfaces are layered, with each torus having a distinct but constant

, forming a series of concentric structures. These nested tori are the loci of velocity and vorticity lines which are confined to specific toroidal surfaces.

As the velocity field lines are constrained to those tori we have according to Equation (

67)

. For a uniform specific entropy

s, it follows from Equation (

55) that also the vorticity lines are constrained to the same.

We assume that the flow is confined between two specific tori, bounded by

, where

a and

are constants and satisfy

. Within this range, we introduce an angular coordinate

on the tori. This coordinate will help describe the movement along the surface of the tori, providing a clearer understanding of the flow’s structure on these confined surfaces:

In this scenario, we establish an orthogonal coordinate system on the toroidal surfaces using the coordinates

, where

represents the radial coordinate,

is the azimuthal angle, and

is the angular coordinate introduced above. These coordinates are orthogonal to one another, which simplifies the application of standard vector calculus operations in terms of these toroidal coordinates. The mathematical operators used in vector analysis, such as the gradient, divergence, and curl, are given below to facilitate analysis in this specific coordinate system:

12.1. The Toroidal Velocity Field

According to the equation represented by Equation (

47), we can express the velocity field

in a specific form. This equation allows us to rewrite the velocity in a way that reflects the underlying physical principles or constraints imposed by the fluid’s motion. The equation provides a structured relationship between the velocity and other relevant variables, ensuring consistency with the fluid dynamics framework being considered. The form of

in Equation (

47) plays a central role in analyzing and solving fluid dynamics problems in this context:

Introducing the definition below allows us to establish a simpler mathematical and physical concept:

In this context, Equation (

101) is transformed into a new expression that conforms to the established toroidal coordinate system. This step adjusts the general velocity form to be compatible with the specific geometry of the system, which involves toroidal surfaces. By translating the velocity components into the coordinates of the toroidal framework—typically involving

,

, and

—we adapt the original equation to reflect the structure of the flow on these nested tori. This adaptation is essential for analyzing the dynamics of flows constrained within such surfaces:

Since the velocity vector

is assumed to be confined to the toroidal surfaces, we have certain conditions that simplify the analysis. Specifically, the components of the gradient of

along the directions of

and

, are both zero. Also the component of the velocity along the

direction,

, is also zero. This leads to the following simplified expression, represented by a partial derivative notation

:

Provided that

exists it follows that under smoothness assumptions we obtain the equality:

This equation has the following solution:

As

is a divergence-less vector according to Equation (

67) and since is must be also orthogonal to

it follows that a function

exists such that:

In the current case we have:

If the function

indeed exists and is smooth we have:

Inserting Equations (

107) into Equation (

112) it follows that:

Which is simplified to the form below:

A non unique solution of the above is given below:

Thus

is the circulation along the `long path’:

on the other hand is the circulation along the `short path’:

Thus the velocity field is of the form:

The vorticity is calculated using the definition Equations (

5) with the help of Equation (

100):

Solving Equations (

109) for

, we find the expression:

in which:

and also:

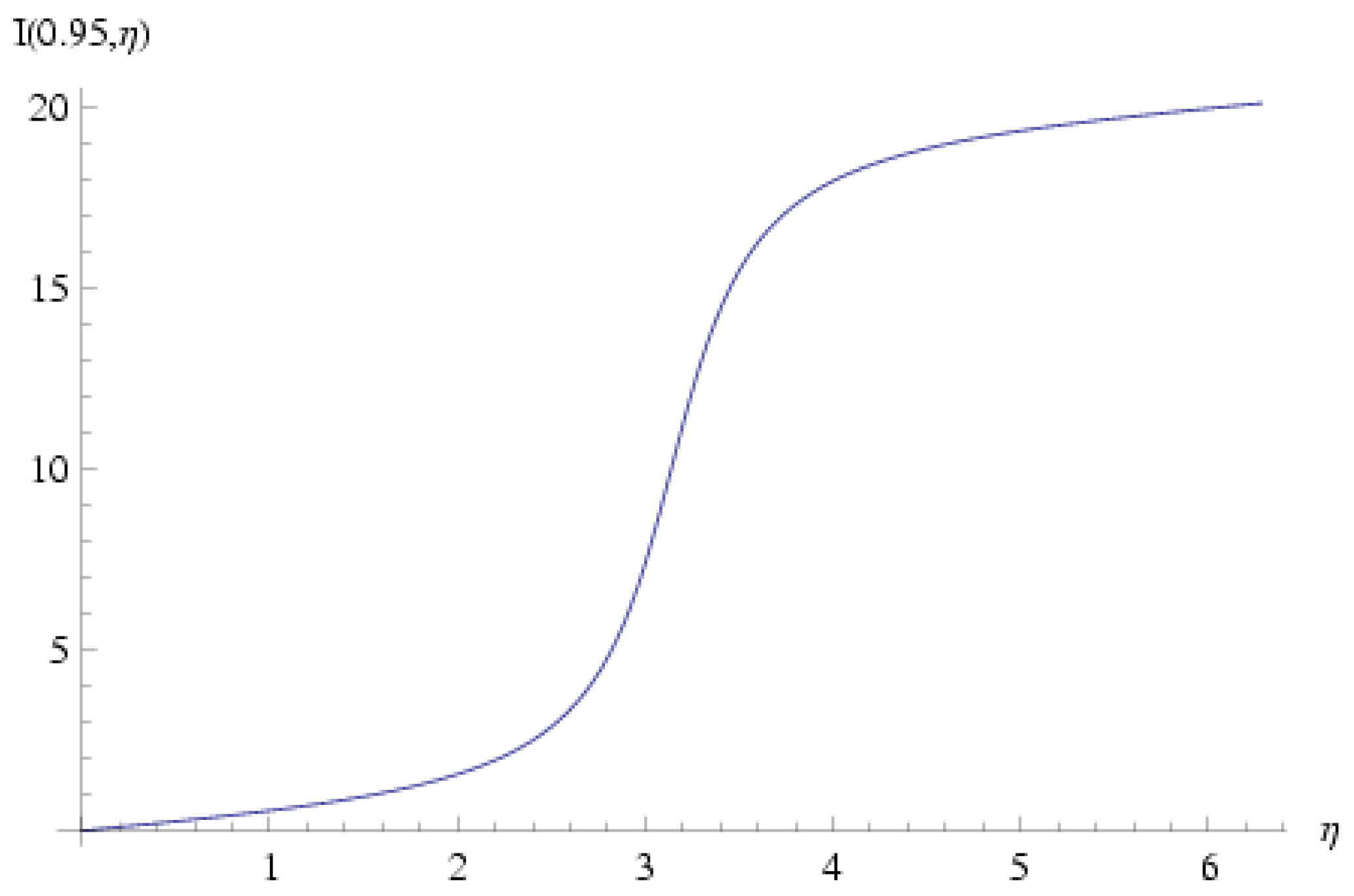

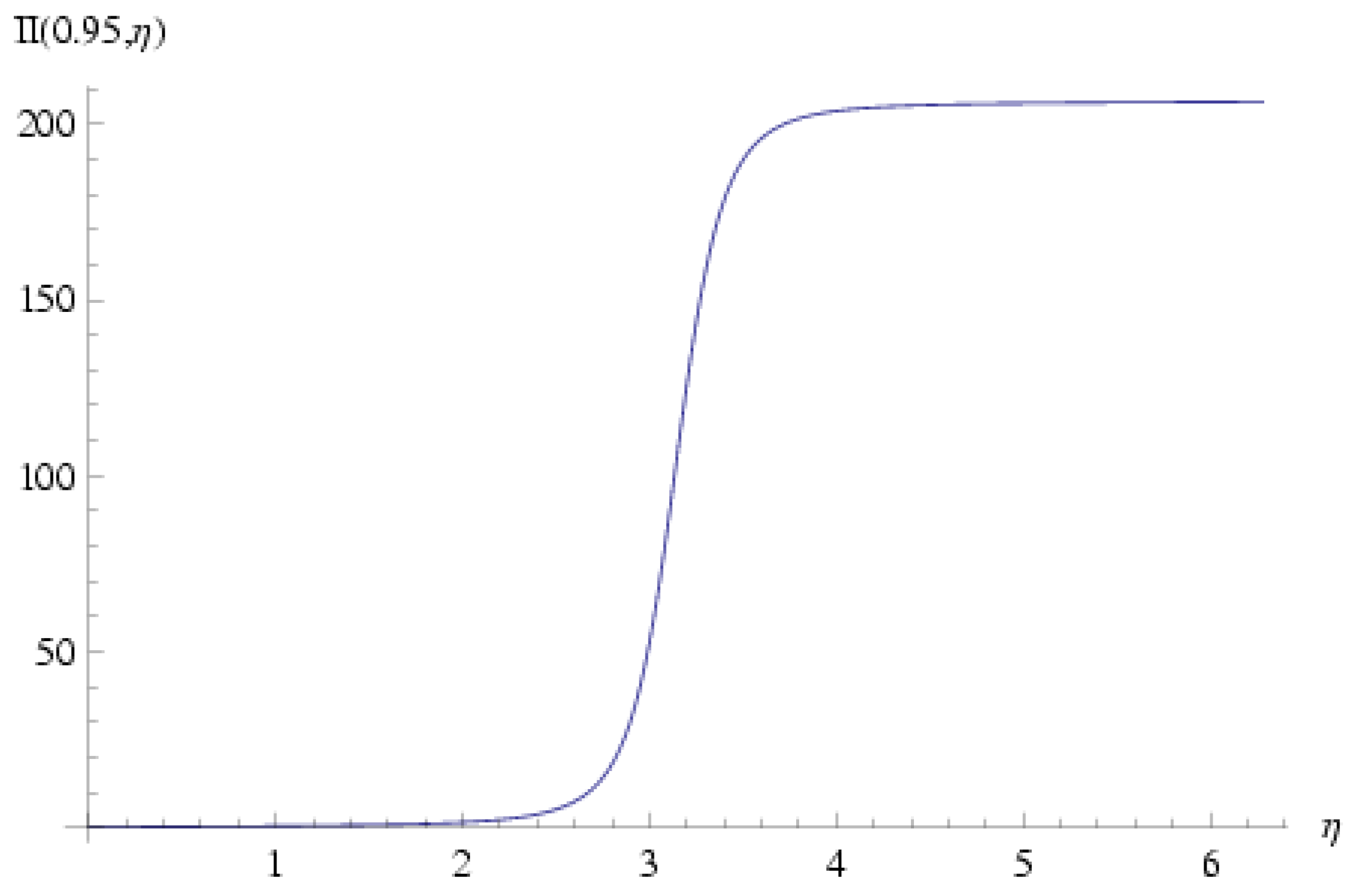

Plots of

and

are shown in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 for the representative value

; obviously both functions are non-single-valued in

.

Combining Equation (

108) with Equation (

67) for

we arrive at the Jacobian equation for

:

Inserting Equation (

120) and Equation (

119) into Equation (

123) it follows that:

Eliminating

and multiplying both sides by

we obtain:

Inserting the vorticity field into the above equation, the following explicit form is derived:

As

is a function of

and not of

it follows that:

thus:

We conclude that up to a constant factor is not an arbitrary function but is dictated by the short-way circulation.

We are now is a position we obtain explicit formulae for the rest of the variation functions. From Equations (

104) it follows that:

and from Equations (

104) for

, we derive:

Thus Equation (

102) yields an expression for

:

12.2. Helicity

Flow helicity can be obtained using Equation (

85).

discontinuity along the the line of fixed

and

is

’s

discontinuity. It thus follows from Equation (

131) that:

The vorticity flux element is:

It follows that the helicity can be calculated easily:

Thus the helicity is due to the azimuthal vortex lines surrounding a `virtual’ vortex line along the symmetry axis of the torus

1. Of course the helicity can also be derived using the standard Equation (

78) but with an identical result.

12.3. Dynamics on the Torus

At this point we have only studied the flow kinematics on the said torus, we did not discuss the forces that cause the flow. The dynamics of the flow is encapsulated in the single scalar equation which is the

Equation (

67). Thus, the force potential needed to drive the flow is:

For which we used Equation (

118), Equation (

115) and Equation (

128) and also taken into account that the specific entropy

s is uniform. It follows that the force potential needed to supports this family of flows depends on the equation of state

of the material under consideration, in addition to the arbitrary functions

and the constant

. It is obvious that the validity of this family of solutions can be verifies by inserting the velocity field given in Equation (

118) and the density of Equation (

115) into Euler Equations (

2) and the continuity Equation (

1).

We consider the case in which

is gravitational. Two possible cases may be considered. The case of torus self-gravity in which the potential

must satisfy:

G is the universal constant of gravity; and the case for which

is external, such that the potential

must satisfy

inside the torus. The potential is a function of

made of two contributions:

is required to balance pressure and centrifugal forces due to rotation the long way round the torus. Let us consider the case in which

(pressure and `long-way’ centrifugal forces neglected); such that:

Using Equation (

99), Equation (

136) takes the approximated form:

A solution is possible only if the following is satisfied:

This is solved by:

in which

are constants. Hence

Through Equation (

138) we can derive the circulation round the short way:

13. Conclusions

We have discussed the variational analysis of non-barotropic flows starting from a classical Lagrangian variational analysis, and moving later to an Eulerian variational analysis which demanded auxiliary functions. This lagrangian which depends on nine functions: the original set of five functions and auxiliary variables was reduces to a six function Lagrangian depending on . This was further reduced to a four function Lagrangian of the remaining variables , leading to a set of four cumbersome equations. We have also dedicated a paragraph to the stationary version of our Lagrangian formalism. Our result can be compared with respect to what was achieved in the last realistic barotropic case, there a three function formalism is available for both stationary and non-stationary flows. In both barotropic and non-barotropic cases variational formalism has reduced the number of variables needed with respect to the physical description. The same equations can be obtained using either a Lagrangian formalism or Hamiltonian formalism provided that we adhere to an Eulerian description of the flow. However, this economy of variables comes with a topological cost. In the barotropic case the vorticity lines must lie on surfaces and cannot be volume filling. This is also true for non-barotropic flows in which one demands the same for the topological vorticity.

Analyzing the stability and describing numerical schemes using the discussed variational principles is beyond the scope of this paper. It is likely that to address these aspects, we will need to introduce additional constants of motion constraints into the action, similar to what was done by Arnold and others [

17,

18], and also discussed in other works [

19,

20]. Additional points for future study include the Noether currents of the present variational formalism and their implications. Also [

21] suggests that as in the magnetohydrodynamic case there may be a way to reduce the variables number down to three for non-barotropic

stationary fluid dynamics. Hopefully this will be studied in a future paper.

Appendix A. Variational Formalism of Point Particles

Let’s examine a classical particle with coordinates

and mass

m moving under the influence of an external force which can be derived from a scalar potential

. We are not concerned with the particle’s influence on the field, treating the field as "external." The action for this particle is given by:

This entails a variation of the action:

Since the classical trajectory is defined by the principle that any small variation of the action

(which vanishes at times

and

but is otherwise arbitrary) results in no change in the action, it follows that:

For a system consisting of

N particles, where each particle is identified by an index

, with corresponding mass

, charge

, position vector

, and velocity

, the action and Lagrangian for each particle are given as follows:

From the above it is easy to derive the action and Lagrangian for a system of particles is:

The variational analysis follows along the same lines as for a single particle.W e thus obtain the following set of equations:

References

- Asher Yahalom and Donald Lynden-Bell "Variational Principles for Topological Barotropic Fluid Dynamics" ["Simplified Variational Principles for Barotropic Fluid Dynamics" Los-Alamos Archives - physics/ 0603162] Geophysical & Astrophysical Fluid Dynamics. 11/2014; 108(6). [CrossRef]

- Salmon, R. Hamiltonian fluid mechanics. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 1988, 20, 225–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H.K. Moffatt, "The degree of knottedness of tangled vortex lines,". J. Fluid Mech. 1969, 35, 117. [CrossRef]

- C. Eckart, "Variation Principles of Hydrodynamics,". Phys. Fluids 1960, 3, 421. [CrossRef]

- F.P. Bretherton "A note on Hamilton’s principle for perfect fluids," Journal of Fluid Mechanics / Volume 44 / Issue 01 / October 1970, pp 19 31, Published online: 29 March 2006. [CrossRef]

- Clebsch, A. Uber eine allgemeine transformation der hydro-dynamischen Gleichungen. J. Reine Angew. Math. 1857, 54, 293–312. [Google Scholar]

- Clebsch, A. Uber die Integration der hydrodynamischen Gleichungen. J. Reine Angew. Math. 1859, 56, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- B. Davydov, "Variational principle and canonical equations for an ideal fluid,". Doklady Akad. Nauk (in Russian). 1949, 69, 165–168.

- R. L. Seliger & G. B. Whitham, Proc. Roy. Soc. London, A305, 1 (1968).

- A. Yahalom "Simplified Variational Principles for non-Barotropic Magnetohydrodynamics". (arXiv: 1510.00637 [Plasma Physics]). J. Plasma Phys. 2016, arXiv:1510.00637 [Plasma Physics]). J. Plasma Phys. vol. 82, 905820204 20162016, 905820204.

- A. Yahalom "Non-Barotropic Magnetohydrodynamics as a Five Function Field Theory". International Journal of Geometric Methods in Modern Physics, No. 10 (November 2016). Vol. 13 1650130 (13 pages) ©World Scientific Publishing Company. [CrossRef]

- H. Lamb Hydrodynamics Dover Publications (1945).

- A. Yahalom, "Method and System for Numerical Simulation of Fluid Flow", US patent 6,516,292, 2003.

- D. Lynden-Bell and J. Katz "Isocirculational Flows and their Lagrangian and Energy principles". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Mathematical and Physical Sciences 1981, 378, 179–205.

- J. Katz & D. Lynden-Bell 1982. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. 1982, A 381, 263–274.

- Asher Yahalom "Using fluid variational variables to obtain new analytic solutions of self-gravitating flows with nonzero helicity". Procedia IUTAM 2013, 7, 223–232. [CrossRef]

- V. I. Arnold "A variational principle for three-dimensional steady flows of an ideal fluid". Appl. Math. Mech. 2014, 29, 154–163.

- V. I. Arnold "On the conditions of nonlinear stability of planar curvilinear flows of an ideal fluid", Dokl. Acad. Nauk SSSR 162 no. 5.

- Yahalom A., Katz J. & Inagaki K. 1994, Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 268 506-516. fluid", Dokl. Acad. Nauk SSSR 162 no. 5.

-

Yahalom A. 2011 Stability in the Weak Variational Principle of Barotropic Flows and Implications for Self-Gravitating Discs. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2011, 418, 401–426.

- Yahalom, Asher. 2021. "A Three-Function Variational Principle for Stationary Nonbarotropic Magnetohydrodynamics" Symmetry 13, no. 9: 1632. [CrossRef]

| 1 |

The author would like to thank Professor Moffatt for the interpretation of this result. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).