Submitted:

03 May 2025

Posted:

06 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

2.2. Microbial Strain and Culture Conditions

2.3. Sugarcane Bagasse Hydrolysate (SCH) Preparation

2.4. Ethanol Production from Acid and Enzymatic Hydrolysate of Sugarcane Bagasse

2.5. Optimization Conditions for Ethanol Production from SBH

2.6. Analytical Methods and Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

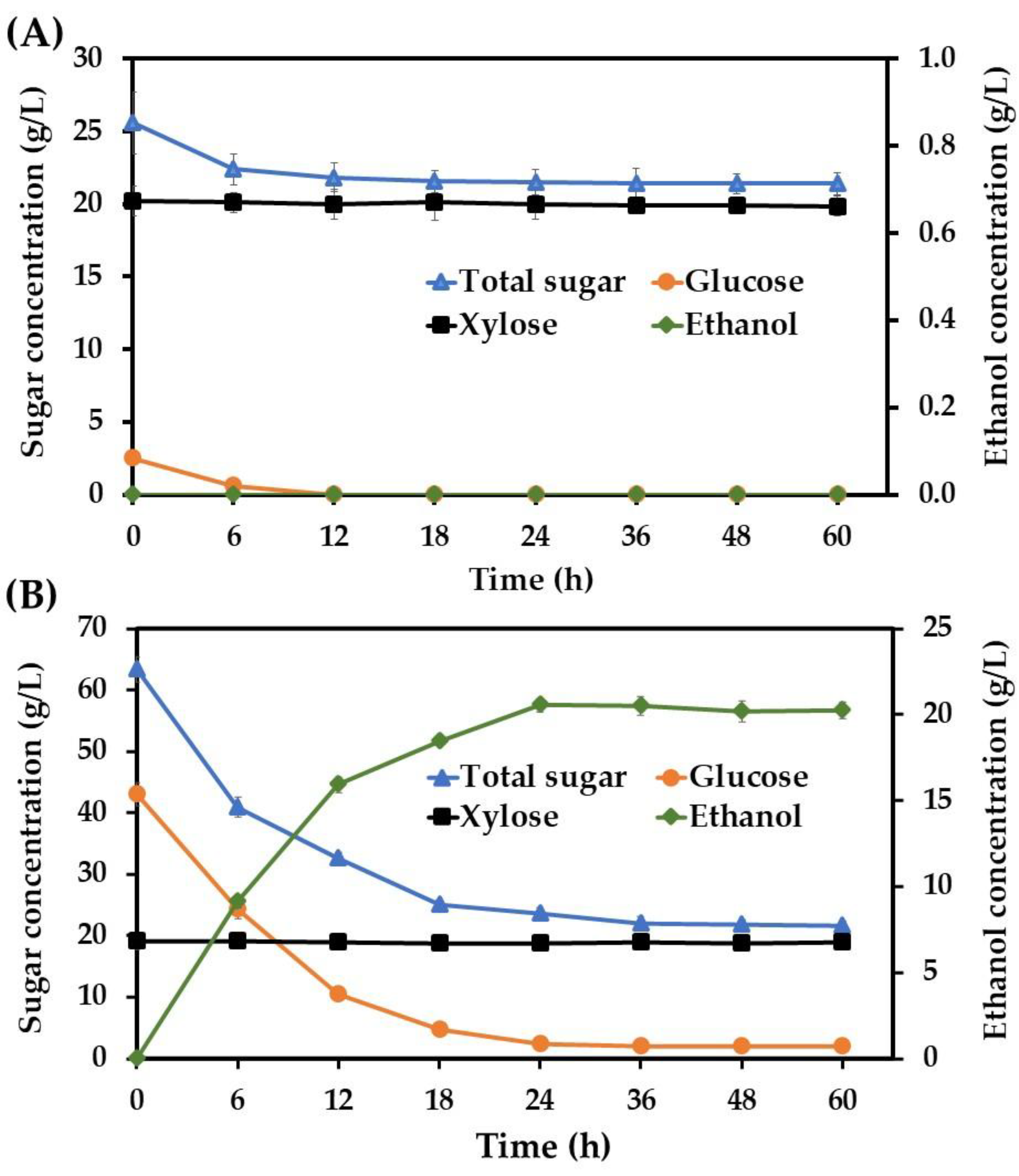

3.1. Ethanol Production Potential of S. ludwigii Using Acid and Enzymatic Sugarcane Bagasse Hydrolysate as Feedstock

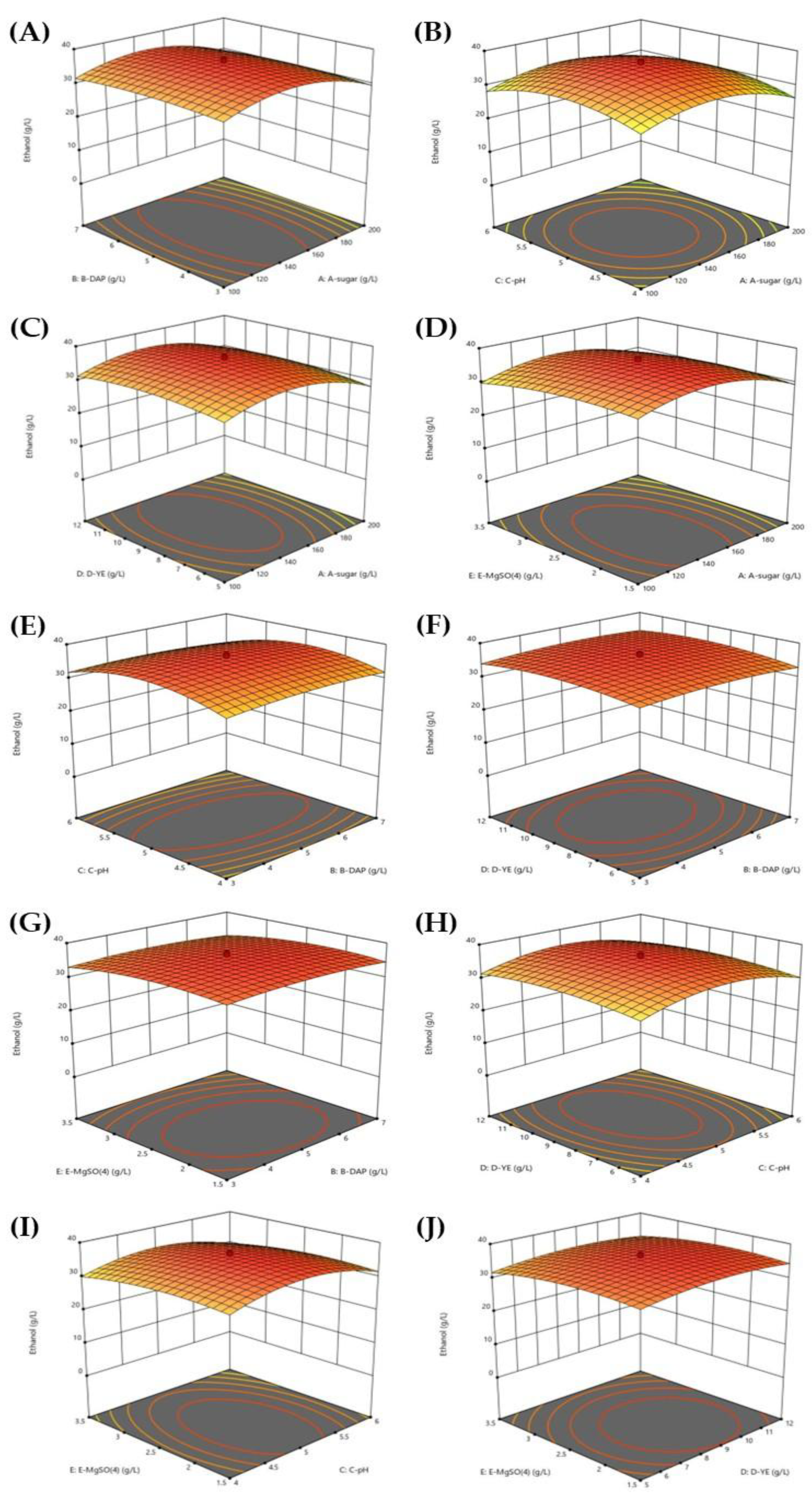

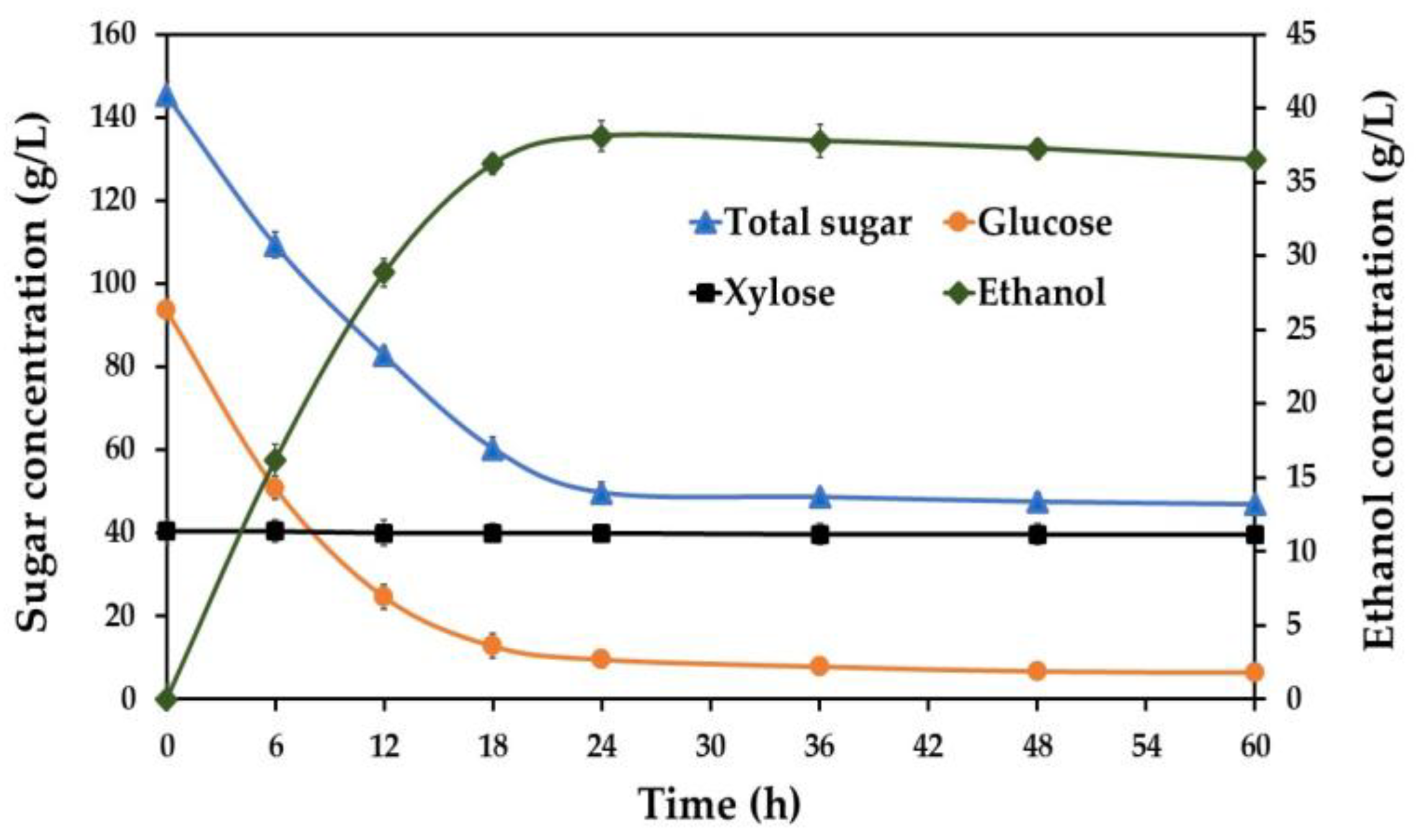

3.2. Optimization Conditions for Ethanol Production from SBH

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/sugar-cane-production?country=USA~BRA~IND~CHN~European+Union~THA (accessed on 19 April, 2025).

- Junpen, A.; Pansuk, J.; Garavait, S. Estimation of reduced air emissions as a result of the implementation of the measure to reduce burned sugarcane in Thailand. Atmosphere. 2020, 11, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, S.C.; Maehara, L.; Machado, C.M.M.; Farinas, C.S. 2G ethanol from the whole sugarcane lignocellulosic biomass. Biotechnol. Biofuels. 2015, 8, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Souza, R.F.R.; Dutra, E. D.; Leite, F.C.B.; Cadete, R.M.; Rosa, C.A.; Stambuk, B.U.; Stamford, T.L.M.; de Morais, M.A.Jr. Production of ethanol fuel from enzyme-treated sugarcane bagasse hydrolysate using d-xylose-fermenting wild yeast isolated from Brazilian biomes. 3 Biotech. 2018, 8, 312. [Google Scholar]

- de Araujo Guilherme, A.; Dantas, P.V.F.; Padilha, C.E.A.; Dos Santos, E.S.; de Macedo, G.R. Ethanol production from sugarcane bagasse: Use of different fermentation strategies to enhance an environmental-friendly process. J Environ Manage. 2019, 234, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamnipa, N.; Klanrit, P.; Thanonkeo, S.; Thanonkeo, P. Sorbitol production from a mixture of sugarcane bagasse and cassava pulp hydrolysates using thermotolerant Zymomonas mobilis TISTR548. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2022, 188, 115741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolpatcha, S.; Phong, H.X.; Thanonkeo, S.; Klanrit, P.; Yamada, M.; Thanonkeo, P. Adaptive laboratory evolution under acetic acid stress enhances the multistress tolerance and ethanol production efficiency of Pichia kudriavzevii from lignocellulosic biomass. Sci. Rep.-UK. 2023, 13, 21000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, A.A.; Inambao, F.L. Bioethanol production techniques from lignocellulose biomass as alternative fuel: a review. Int. J. Mech. Eng. Technol. 2019, 10, 34–71. [Google Scholar]

- Dussan, K.J.; Silva, D.D.V.; Moraes, E.J.C.; Arruda, P.V.; Felipe, M.G.A. Dilute-acid hydrolysis of cellulose to glucose from sugarcane bagasse. Chem. Engineer. Trans. 2014, 38, 433–438. [Google Scholar]

- Azhar, S.H.M.; Abdulla, R.; Jambo, S.A.; Marbawi, H.; Gansau, J.A.; Faik, A.A.M.; Rodrigues, K.F. Yeasts in sustainable bioethanol production: A review. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2017, 10, 52–61. [Google Scholar]

- Sritrakul, N.; Nitisinprasert, S.; Keawsompong, S. Evaluation of dilute acid pretreatment for bioethanol fermentation from sugarcane bagasse pith. Agri. Natural Resour. 2017, 51, 512–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phong, H.X.; Klanrit, P.; Dung, N.T.P.; Yamada, M.; Thanonkeo, P. Isolation and characterization of thermotolerant yeasts for the production of second-generation bioethanol. Ann. Microbiol. 2019, 69, 765–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunkar, B.; Bhukya, B. Bi-phasic hydrolysis of corncobs for the extraction of total sugars and ethanol production using inhibitor resistant and thermotolerant yeast, Pichia kudriavzevii. Biomass Bioenerg. 2021, 153, 106230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandel, A.K.; Kapoor, R.K.; Singh, A.; Kuhad, R.C. Detoxification of sugarcane bagasse hydrolysate improves ethanol production by Candida shehatae NCIM 3501. Bioresource Technol. 2007, 98, 1947–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, D.H.; Park, E.H.; Kim, M.D. Isolation of thermotolerant yeast Pichia kudriavzevii from nuruk. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2017, 26, 1357–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avchar, R.; Lanjekar, V.; Kshirsagar, P.; Dhakephalkar, P.K.; Dagar, S.S.; Baghela, A. Buffalo rumen harbours diverse thermotolerant yeasts capable of producing second-generation bioethanol from lignocellulosic biomass. Renew. Energ. 2021, 173, 795–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamnipa, N.; Thanonkeo, S.; Klanrit, P.; Thanonkeo, P. The potential of the newly isolated thermotolerant yeast Pichia kudriavzevii RZ8-1 for high-temperature ethanol production. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2018, 49, 378–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aouine, M.; Elalami, D.; Koraichi, S.I.; Haggoud, A.; Barakat, A. Exploring natural fermented foods as a source for new efficient thermotolerant yeasts for the production of second-generation bioethanol. Energies. 2022, 15, 4954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Zhang, P.; Zhou, X.; Zheng, J.; Ma, Y.; Liu, C.; Wu, T.; Li, H.; Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Zhao, X.; Mehmood, M.A.; Zhu, H. Isolation, identification, and characterization of an acid-tolerant Pichia kudriavzevii and exploration of its acetic acid tolerance mechanism. Fermentation. 2023, 9, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charoensopharat, K.; Thanonkeo, P.; Thanonkeo, S.; Yamada, M. Ethanol production from Jerusalem artichoke tubers at high temperature by newly isolated thermotolerant inulin-utilizing yeast Kluyveromyces marxianus using consolidated bioprocessing. A. Van. Leeuw. J. Microb. 2015, 108, 173–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemansi.; Himanshu.; Patel, A.K.; Saini, J.K.; Singhania, R.R. Development of multiple inhibitor tolerant yeast via adaptive laboratory evolution for sustainable bioethanol production. Bioresource Technol. 2022, 344, 126247.

- Pattanakittivorakul, S.; Tsuzuno, T.; Kosaka, T.; Murata, M.; Kanesaki, Y.; Yoshikawa, H.; Limtong, S.; Yamada, M. Evolutionary adaptation by repetitive long-term cultivation with gradual increase in temperature for acquiring multi-stress tolerance and high ethanol productivity in Kluyveromyces marxianus DMKU 3-1042. Microorganisms. 2022, 10, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilap, W.; Thanonkeo, S.; Klanrit, P.; Thanonkeo, P. The potential of multistress tolerant yeast, Saccharomycodes ludwigii, for second-generation bioethanol production. Sci. Rep-UK. 2022, 12, 22062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loureiro, V.; Malfeito-Ferreira, M. Spoilage yeasts in the wine industry. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2003, 86, 23–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thammasittirong, S.N.; Chamduang, T.; Phonrod, U.; Sriroth, K. Ethanol production potential of ethanol-tolerant Saccharomyces and non-Saccharomyces yeasts. Pol. J. Microbiol. 2012, 61, 219–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udomsaksakul, N.; Kodama, K.; Tanasupawat, S.; Savarajara, A. Diversity of ethanol fermenting yeasts in coconut inflorescence sap and their application potential. ScienceAsia. 2018, 44, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vejarano, R. Saccharomycodes ludwigii, control and potential uses in winemaking processes. Fermentation. 2018, 4, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuanpeng, S.; Thanonkeo, S.; Yamada, M.; Thanonkeo, P. Ethanol production from sweet sorghum juice at high temperatures using a newly isolated thermotolerant yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae DBKKU Y-53. Energies. 2016, 9, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Techaparin, A.; Thanonkeo, P.; Klanrit, P. High-temperature ethanol production using thermotolerant yeast newly isolated from Greater Mekong Subregion. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2017, 48, 465–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuanpeng, S.; Thanonkeo, S.; Klanrit, P.; Yamada, M.; Thanonkeo, P. Optimization conditions for ethanol production from sweet sorghum juice by thermotolerant yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae: using a statistical experimental design. Fermentation. 2023, 9, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phong, H.X.; Klanrit, P.; Dung, N.T.P.; Thanonkeo, S.; Yamada, M.; Thanonkeo, P. High-temperature ethanol fermentation from pineapple waste hydrolysate and gene expression analysis of thermotolerant yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Sci. Rep-UK. 2022, 12, 13965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.V.; Nguyen, K.H.V.; Nguyen, N.L.; Ho, X.T.T.; Truong, P.H.; Nguyen, K.C.T. Lychee-derived, thermotolerant yeasts for second-generation bioethanol production. Fermentation. 2022, 8, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, F.; Guimarães, P.M.R.; Teixeira, J.A.; Domingues, L. Optimization of low-cost medium for very high gravity ethanol fermentations by Saccharomyces cerevisiae using statistical experimental designs. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 7856–7863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mecozzi, M. Estimation of total carbohydrate amount in environmental samples by the phenol−sulphuric acid method assisted by multivariate calibration. Chemometr. Intell. Lab. 2005, 79, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laopaiboon, L.; Nuanpeng, S.; Srinophakun, P.; Klanrit, P.; Laopaiboon, P. Ethanol production from sweet sorghum juice using very high gravity technology: Effects of carbon and nitrogen supplementations. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 4176–4182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limtong, S.; Sringiew, C.; Yongmanitchai, W. Production of fuel ethanol at high temperature from sugar cane juice by a newly isolated Kluyveromyces marxianus. Bioresour. Technol. 2007, 98, 3367–3374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilap, W.; Thanonkeo, S.; Klanrit, P.; Thanonkeo, P. The potential of the newly isolated thermotolerant Kluyveromyces marxianus for high-temperature ethanol production using sweet sorghum juice. 3 Biotech. 2018, 8, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, F.W.; Chen, L.J.; Zhang, Z.; Anderson, W.A.; Moo-Young, M. Continuous ethanol production and evaluation of yeast cell lysis and viability loss under very high gravity medium conditions. J. Biotechnol. 2004, 110, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozmihci, S.; Kargi, F. Comparison of yeast strains for batch ethanol fermentation of cheese-whey powder (CWP) solution. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2007, 44, 602–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballesteros, I.; Oliva, J.M., Negro, M. J., Manzanares, P. & Ballesteros, M. Enzymic hydrolysis of steam exploded herbaceous agricultural waste (Brassica carinata) at different particule sizes. Process Biochem. 38, 187−192 (2002).

- Boonchuay, P.; Techapun, C.; Leksawasdi, N.; Seesuriyachan, P.; Hanmoungjai, P.; Watanabe, M.; Chaiyaso, T. Bioethanol production from cellulose-rich corncob residue by the thermotolerant Saccharomyces cerevisiae TC-5. J. Fungi. 2021, 7, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valamonfared, J.; Javanmard, A.S.; Ghaedi, M.; Bagherinasab, M. Bioethanol production using lignocellulosic materials and thermophilic microbial hydrolysis. Biomass Conv. Bior. 2024, 14, 16589–16601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Cao, M.; Guo, H.; Qi, W.; Su, R.; He, Z. Enhanced ethanol production from pomelo peel waste by integrated hydrothermal treatment, multienzyme formulation, and fed-batch operation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 4643–4651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, P.; Beniwal, A.; Kokkiligadda, A.; Vij, S. Response and tolerance of yeast to changing environmental stress during ethanol fermentation. Process Biochem. 2018, 72, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eardley, J.; Timson, D.J. Yeast cellular stress: Impacts on bioethanol production. Fermentation. 2020, 6, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagi, H. Molecular mechanisms and highly functional development for stress tolerance of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2021, 85, 1017–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postaru, M.; Tucaliuc, A.; Cascaval, D.; Galaction, A.I. Cellular stress impact on yeast activity in biotechnological processes-A short overview. Microorganisms. 2023, 11, 2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, B.; Wang, W.B.; Wang, Y.T.; Zhao, X.Q. Regulatory mechanisms underlying yeast chemical stress response and development of robust strains for bioproduction. Curr. Opinion. Biotechnol. 2024, 86, 103072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.R.; Mehmood, M.A.; Wang, L.; Ahmad, N.; Ma, H.J. Omics-based strategies to explore stress tolerance mechanisms of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for efficient fuel ethanol production. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10, 884582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topaloğlu, A.; Esen, Ö.; Turanli-Yildiz, B.; Arslan, M.; Çakar, Z.P. From Saccharomyces cerevisiae to ethanol: Unlocking the power of evolutionary engineering in metabolic engineering applications. J. Fungi. 2023, 9, 984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasch, A.P.; Spellman, P.T.; Kao, C.M.; Carmel-Harel, O.; Eisen, M.B.; Storz, G.; Botstein, D.; Brown, P.O. Genomic expression programs in the response of yeast cells to environmental changes. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2000, 11, 4241–4257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubiak-Szymendera, M.; Pryszcz, L.P.; Bialas, W.; Celinska, E. Epigenetic response of Yarrowia lipolytica to stress: Tracking methylation level and search for methylation patterns via whole-genome sequencing. Microorganisms. 2021, 9, 1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, J.; Grillitsch, K.; Daum, G.; Mas, A.; Beltran, G.; Torija, M.J. The role of the membrane lipid composition in the oxidative stress tolerance of different wine yeasts. Food Microbiol. 2019, 78, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, R.A.; Bourbon-Melo, N.; Sá-Correia, I. The cell wall and the response and tolerance to stresses of biotechnological relevance in yeasts. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 953479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, Y.; Qi, X.; Lin, Y.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Q. A hierarchical transcriptional regulatory network required for long-term thermal stress tolerance in an industrial Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 9, 826238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özel, A.; Topaloğlu, A.; Esen, Ö.; Holyavkin, C.; Baysan, M.; Çakar, Z.P. Transcriptomic and physiological meta-analysis of multiple stress-resistant Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains. Stresses. 2024, 4, 714–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Code | Variable | Unit | Level | ||||

| −2.37 | −1 | 0 | +1 | +2.37 | |||

| A | Sugar concentration | g/L | 31.08 | 100.00 | 150.00 | 200.00 | 268.92 |

| B | DAP | g/L | 0.24 | 3.00 | 5.00 | 7.00 | 9.76 |

| C | pH | - | 2.62 | 4.00 | 5.00 | 6.00 | 7.38 |

| D | Yeast extract | g/L | 0.18 | 5.00 | 8.50 | 12.00 | 16.82 |

| E | MgSO4 | g/L | 0.12 | 1.50 | 2.50 | 3.50 | 4.88 |

| Run | A-sugar (g/L) |

B-DAP (g/L) |

C-pH | D-YE (g/L) |

E-MgSO4 (g/L) |

Ethanol concentration (P, g/L) | |

| Predict value | Actual value | ||||||

| 1 | 200.00 | 3.00 | 4.0 | 12.00 | 1.50 | 22.70 | 20.34 |

| 2 | 150.00 | 5.00 | 5.0 | 16.82 | 2.50 | 28.08 | 27.40 |

| 3 | 150.00 | 5.00 | 5.0 | 8.50 | 4.88 | 25.04 | 23.14 |

| 4 | 100.00 | 3.00 | 6.0 | 12.00 | 3.50 | 23.54 | 24.06 |

| 5 | 200.00 | 7.00 | 6.0 | 5.00 | 3.50 | 20.27 | 20.81 |

| 6 | 200.00 | 7.00 | 6.0 | 5.00 | 1.50 | 22.14 | 21.59 |

| 7 | 200.00 | 7.00 | 4.0 | 5.00 | 3.50 | 20.93 | 19.89 |

| 8 | 150.00 | 5.00 | 5.0 | 8.50 | 2.50 | 36.26 | 36.62 |

| 9 | 150.00 | 5.00 | 5.0 | 8.50 | 2.50 | 36.26 | 35.80 |

| 10 | 100.00 | 7.00 | 4.0 | 12.00 | 3.50 | 24.69 | 25.10 |

| 11 | 100.00 | 3.00 | 4.0 | 12.00 | 3.50 | 23.85 | 24.34 |

| 12 | 100.00 | 3.00 | 4.0 | 12.00 | 1.50 | 25.55 | 26.20 |

| 13 | 100.00 | 7.00 | 6.0 | 12.00 | 1.50 | 25.30 | 25.04 |

| 14 | 150.00 | 5.00 | 2.6 | 8.50 | 2.50 | 14.37 | 13.35 |

| 15 | 200.00 | 3.00 | 4.0 | 5.00 | 3.50 | 21.03 | 22.76 |

| 16 | 200.00 | 3.00 | 6.0 | 5.00 | 3.50 | 22.28 | 20.40 |

| 17 | 200.00 | 3.00 | 6.0 | 12.00 | 1.50 | 23.75 | 24.60 |

| 18 | 150.00 | 5.00 | 5.0 | 8.50 | 0.12 | 29.28 | 30.20 |

| 19 | 100.00 | 7.00 | 6.0 | 5.00 | 3.50 | 21.73 | 23.56 |

| 20 | 100.00 | 3.00 | 4.0 | 5.00 | 1.50 | 25.08 | 25.82 |

| 21 | 200.00 | 7.00 | 4.0 | 12.00 | 3.50 | 22.71 | 23.57 |

| 22 | 150.00 | 5.00 | 5.0 | 0.18 | 2.50 | 26.10 | 25.80 |

| 23 | 31.08 | 5.00 | 5.0 | 8.50 | 2.50 | 12.00 | 10.02 |

| 24 | 100.00 | 3.00 | 4.0 | 5.00 | 3.50 | 23.38 | 23.15 |

| 25 | 100.00 | 3.00 | 6.0 | 12.00 | 1.50 | 25.63 | 26.04 |

| 26 | 100.00 | 7.00 | 4.0 | 12.00 | 1.50 | 27.14 | 28.40 |

| 27 | 200.00 | 3.00 | 4.0 | 5.00 | 1.50 | 21.76 | 21.50 |

| 28 | 150.00 | 9.76 | 5.0 | 8.50 | 2.50 | 30.54 | 29.80 |

| 29 | 268.92 | 5.00 | 5.0 | 8.50 | 2.50 | 6.87 | 7.87 |

| 30 | 200.00 | 7.00 | 4.0 | 5.00 | 1.50 | 22.42 | 22.80 |

| 31 | 100.00 | 7.00 | 4.0 | 5.00 | 3.50 | 23.37 | 23.90 |

| 32 | 150.00 | 5.00 | 7.4 | 8.50 | 2.50 | 13.67 | 13.71 |

| 33 | 200.00 | 7.00 | 6.0 | 12.00 | 3.50 | 21.46 | 21.80 |

| 34 | 200.00 | 3.00 | 4.0 | 12.00 | 3.50 | 21.95 | 22.90 |

| 35 | 150.00 | 5.00 | 5.0 | 8.50 | 2.50 | 36.26 | 37.03 |

| 36 | 150.00 | 5.00 | 5.0 | 8.50 | 2.50 | 36.26 | 35.90 |

| 37 | 200.00 | 7.00 | 4.0 | 12.00 | 1.50 | 24.20 | 24.19 |

| 38 | 200.00 | 7.00 | 6.0 | 12.00 | 1.50 | 23.34 | 22.75 |

| 39 | 150.00 | 0.24 | 5.0 | 8.50 | 2.50 | 31.04 | 30.80 |

| 40 | 100.00 | 7.00 | 4.0 | 5.00 | 1.50 | 25.81 | 25.76 |

| 41 | 200.00 | 3.00 | 6.0 | 5.00 | 1.50 | 23.40 | 23.88 |

| 42 | 200.00 | 3.00 | 6.0 | 12.00 | 3.50 | 22.62 | 22.42 |

| 43 | 100.00 | 3.00 | 6.0 | 5.00 | 1.50 | 25.74 | 24.65 |

| 44 | 100.00 | 7.00 | 6.0 | 12.00 | 3.50 | 22.46 | 22.38 |

| 45 | 150.00 | 5.00 | 5.0 | 8.50 | 2.50 | 36.26 | 35.30 |

| 46 | 100.00 | 3.00 | 6.0 | 5.00 | 3.50 | 23.65 | 25.02 |

| 47 | 100.00 | 7.00 | 6.0 | 5.00 | 1.50 | 24.56 | 24.40 |

| Source | Sum Square | df | Mean Square | F-value | p-value* | Remark |

| Model | 1619.550 | 20 | 80.980 | 51.540 | < 0.0001 | Significant |

| A | 50.420 | 1 | 50.420 | 32.090 | < 0.0001 | |

| B | 0.471 | 1 | 0.471 | 0.300 | 0.5885 | |

| C | 0.935 | 1 | 0.935 | 0.595 | 0.4474 | |

| D | 7.520 | 1 | 7.520 | 4.790 | 0.0379 | |

| E | 34.560 | 1 | 34.560 | 22.000 | < 0.0001 | |

| AB | 0.014 | 1 | 0.014 | 0.009 | 0.9266 | |

| AC | 1.910 | 1 | 1.910 | 1.220 | 0.2802 | |

| AD | 0.414 | 1 | 0.414 | 0.264 | 0.6120 | |

| AE | 1.850 | 1 | 1.850 | 1.180 | 0.2875 | |

| BC | 7.350 | 1 | 7.350 | 4.680 | 0.0399 | |

| BD | 1.440 | 1 | 1.440 | 0.920 | 0.3464 | |

| BE | 1.100 | 1 | 1.100 | 0.702 | 0.4098 | |

| CD | 0.684 | 1 | 0.684 | 0.436 | 0.5150 | |

| CE | 0.300 | 1 | 0.300 | 0.191 | 0.6656 | |

| DE | 0.0002 | 1 | 0.0002 | 0.000 | 0.9911 | |

| A2 | 1086.690 | 1 | 1086.690 | 691.660 | < 0.0001 | |

| B2 | 45.170 | 1 | 45.170 | 28.750 | < 0.0001 | |

| C2 | 746.940 | 1 | 746.940 | 475.410 | < 0.0001 | |

| D2 | 126.960 | 1 | 126.960 | 80.810 | < 0.0001 | |

| E2 | 125.030 | 1 | 125.030 | 79.580 | < 0.0001 | |

| Residual | 40.850 | 26 | 1.570 | |||

| Lack of fit | 38.950 | 22 | 1.770 | 3.730 | 0.105 | Not significant |

| Pure error | 1.900 | 4 | 0.475 | |||

| Cor Total | 1660.400 | 46 | ||||

| R2 | 0.975 | |||||

| Adj. R2 | 0.957 | |||||

| CV (%) | 5.140 |

| Microbe | Feedstock | Fermentation parameter 1 | References | ||||

| S (g/L) | T (°C) | P (g/L) | Qp (g/L.h) | TY (%) | |||

| P. kudriavzevii RZ8-1 | Sugarcane bagasse | 85 | 37 | 35.51 | 1.48 | 81.75 | [17] |

| 85 | 40 | 33.84 | 1.41 | 77.91 | |||

| P. kudriavzevii RGB3.2 | Rice straw | 19.10 | 40 | 9.32 | 0.39 | 95.49 | [16] |

| K. marxianus RGB4.5 | Rice straw | 19.10 | 40 | 8.03 | 0.33 | 82.27 | |

| K. marxianus CECT10875 | Woody and herbaceous biomass | NR | 42 | 19.0 | NR | 71.2 | [40] |

| S. cerevisiae | Pomelo peel waste | NR | 30 | 36.00 | 0.75 | 73.50 | [43] |

| S. cerevisiae TC-5 | Corncob residue | NR | 40 | 31.96 | 0.22 | NR | [41] |

| S. cerevisiae PTCC5052 | Wheat straw | NR | 25 | 24.02 | 0.25 | NR | [42] |

| S. ludwigii APRE2 | Pineapple waste | 105.65 | 37 | 38.02 | 1.58 | 82.35 | [23] |

| S. ludwigii APRE2 | Sugarcane bagasse | 143.95 | 37 | 38.11 | 1.59 | 88.24 | This study |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).