1. Introduction

Technological developments and the integration of social media have transformed the media ecosystem, reshaping the processes of collection, production, and dissemination of news. While offering new opportunities, this change has created challenges, such as the lack of clear guidelines for the quality of online news. In addition, the principles of journalistic impartiality and integrity are often compromised, particularly in smaller news organizations, where sales and advertising pressures, political agendas, and powerful media ownership interfere with editorial independence [

1,

2]. News editors frequently overlook ethical standards, prioritizing market-driven goals or clickbait techniques, such as sensational headlines to increase page views and audience engagement metrics, thus undermining the credibility of the media over time.

Given these challenges, exploring news quality in the digital era is crucial. IQJournalism adopts a mixed-methods research approach [

3], combining semi-structured in-depth interviews with big data analysis to identify factors that improve the quality and engagement of journalistic content. Oriented by definitions of journalism as a medium for informing and empowering citizens [

4,

5], the project emphasizes key quality parameters, including subject matter, linguistic attributes, writing style, and audience reception, to support journalists in creating credible and impactful news.

More specifically, we developed IQJournalism, an AI-powered intelligent advisor designed to guide journalists in improving the overall quality of articles and predicting social media success. Leveraging Natural Language Processing (NLP) and user-centered design principles, the system provides real-time feedback on various aspects, including language quality, subjectivity level, emotionality, and entertainment. By fostering readability and engagement, IQJournalism improves the dissemination of news articles, discourages clickbait practices, and offers applications in fields such as politics and marketing.

1.1. Background Work

In recent years, intelligent authoring tools and natural language generators have incorporated sophisticated methods, such as the use of Large Language Models (LLMs) that allow authors to produce content based on specific instructions. Remarkable progress in LLMs, such as Chat-GPT

1, Gemini

2 and Claude

3, along with their increasing integration into everyday products, highlights their potential as highly capable authoring assistants [

6].

Based on these advancements, we conducted a thorough examination of various online editors and writing assistants with the aim of identifying the specific needs and challenges journalists encounter when composing, editing, and revising text based on system recommendations, as well as when managing text files and folders. More specifically, we studied the functionality of the widely used application “Grammarly”

4. It is an award-winning online language component in English Foreign Language (EFL), specifically designed to identify and correct various language errors, including grammatical and spelling mistakes, irregular verb conjugations, inappropriate noun usage, incorrect word choices, as well as check for plagiarism [

7]. The system’s functionality is driven by an interconnected network that integrates AI techniques, including machine learning, deep learning, and NLP. It is important to note that Fitria’s [

7] descriptive qualitative research demonstrated a significant improvement in students’ writing ability, with test performance scores rising from 34 to 77 out of 100 after using “Grammarly.”

Additionally, “Wordcraft” is a traditional text editor, which also contains a set of integrated controls supported by LLM for authoring tasks such as rewriting, summarizing, and changing the style of text. The features of this application are powered by LaMDA, a neural language model trained on Google data, such as public Web documents, forum data, and Wikipedia content. The system has been further refined on high-quality dialogue data, resulting in a model with a chatbot-like interface. The user study conducted to evaluate the application showed that “Wordcraft” demonstrated enhanced engagement, high levels of utility, reduced writing time, facilitated longer stories, encouraged the integration of AI suggestions, and led to greater satisfaction and convenience for authors [

8].

The advanced writing assistant “Wordtune”

5 goes beyond conventional grammar and spelling checks, exploiting AI to understand the author’s intentions and reasoning. It offers suggestions for rewording with alternative informal or formal tones, and adjusts the length of the text by either shortening or expanding it. It also has the ability to change sentence structures and replace words with synonyms, while maintaining the original context [

9]. Furthermore, a Chinese data input method designed to enhance the writing experience through real-time suggestions was presented by Dai et al. [

10]. The system provides context-appropriate suggestions, including syntactic and semantic options, which are derived from text corpus mining and use NLP techniques, such as word vector representation and the Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) topic model. The study findings revealed the effectiveness of “WINGS” in supporting creative writing.

Alongside these developments, Stefnisson and Thue [

11] developed “Mimisbrunnur”, an interactive narrative authoring tool that combines AI technologies, NLP and a mixed-initiative framework. Specifically, the tool consists of three main modules: an initial state editor that defines the starting facts for the generated stories, an action editor that manages the possible actions, and a goal editor that allows authors to specify the desired conditions for the story. Li’s [

12] research investigated the application of an automatic assessment system in English writing with a focus on its potential to improve writing ability and enhance learning motivation. The study findings confirmed the positive role of big data in providing feedback of autocorrection. Although the web-based automatic assessment system is still in the stage of human-machine collaboration, the model consistently reduces errors by 63.4%, with a stable feedback accuracy of about 66.8%.

A slightly different direction of research focused on creating fictional characters through a chatbot called “CharacterChat” [

13]. This tool assists writers in defining character traits through chatbot prompts and enables editors to refine these attributes through open discussions. Two user studies demonstrated the effectiveness of “CharacterChat” as an effective tool for writers, particularly in generating ideas for new characters. Finally, Osone and Ochiai [

14] introduced “BunCho,” a web-based writing interface aimed at enhancing the creative abilities of Japanese novelists through the integration of AI tools, specifically by exploiting GPT-2. The evaluation of “BunCho” revealed positive user experiences and improved writing capabilities, with 69% of writers reporting enjoyment in using the system to enrich their stories. Another study also revealed that 69% of the writers’ summaries showed enhanced creativity.

This paper analyzes the steps taken to develop the IQJournalism system following a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods. For each method applied in the development of the system, research questions and hypotheses were formulated to guide the process and confirm the outcomes. The paper begins by presenting key insights from 20 semi-structured interviews with journalism experts, identifying crucial indicators of journalistic quality. Following this, the paper delves into the stages of knowledge extraction, including data collection, preprocessing, transformation, data mining, and interpretation/evaluation, to extract meaningful patterns and features for model training. The extracted features were used as input for machine learning algorithms, with a focus on supervised learning approaches applied to classify article quality. Evaluation metrics of model performance are presented, along with detailed description of prediction accuracy and the final selection of the optimal model. Lastly, the user-centered methodology, designed to meet the needs of journalists and editors, is described, analyzing the iterative design process of prototyping, testing, and refining the system.

2. Materials and Methods

Despite the fact that there is a growing focus on the development of tools for educational purposes, for enhancing writing skills, and even for creating science fiction characters, there is a lack of guidance tools for the production of journalistic content. The IQJournalism system came to fill this gap aiming to highlight the qualitative characteristics of news articles and their potential to increase engagement on social media. In more detail, the objectives of this approach were as follows:

a. To detect and evaluate the impact of specific text features, such as language quality parameters, headline accuracy, emotional discourse, and audiovisual material, on the overall quality and attractiveness of news pieces.

b. To build and evaluate a machine learning model capable of predicting the quality and social media engagement of online news, focusing on the dimensions of language quality, subjectivity, emotionality, and entertainment.

c. To implement an iterative design process that includes prototyping, testing, and redesign to effectively address specific user needs and requirements.

Bearing in mind the aforementioned objectives, the study was carried out through three distinct methodological phases (see

Figure 1). The first phase (A) involved a qualitative approach, using semi-structured, in-depth interviews with experts to identify key characteristics that influence journalistic quality and engagement. For the purpose of this qualitative study the following research questions were formulated: Which are the main reliability characteristics of a journalistic product/report? Which are the main language quality parameters/characteristics of a journalistic text? Which factors determine the impartiality of a journalist?

The second phase (B) followed a quantitative and computational approach, where insights from the qualitative study were translated into measurable features and incorporated into machine learning models created to predict the quality and social media engagement of online news. In this phase the following research questions were established: How can AI provide a nuanced understanding of what constitutes quality journalism in the digital age? Can the model dimensions, namely Language Quality, Subjectivity, Emotionality, and Entertainment predict quality in online news? What is the specific contribution of the quality criteria to the quality prediction? Can a machine learning model accurately predict social media engagement of news?

The third phase (C) focused on iterative design, where prototyping, testing and redesign processes were employed to improve the system, ensuring that it meets the specific needs and requirements of users [

15]. Through this innovative approach, the IQJournalism system aims to become an essential tool tailored to the preferences of editors, enabling them to produce quality and engaging content.

2.1. Phase A: Qualitative Research

Our initial step toward achieving our main objective was to conduct, for the first time in Greece, semi-structured in-depth interviews [

16] (p. 183), [

17,

18] (p. 756), [

19] (p. 156), [

20]. The interviews were conducted between 13/05/2022 and 13/07/2022 and the total number of interviews was 20: 16 with journalists with significant experience in the media field, focusing on structuring journalistic discourse within a framework of reliability, quality, and impartiality, and with 4 Greek academic researchers specializing in communication and journalism. Data response saturation occurred at the 18th interview and 2 further interviews were conducted for final confirmation. To analyze the information acquired through our interviews thematic analysis was employed [

21,

22,

23] (p. 40).

The research hypotheses (Hs) proposed for Phase A of the study were as follows:

H1: Experts will argue that the decreased accuracy of the headline of a story undermines the overall quality and attractiveness of the journalistic product [

1,

24].

H2: Experts of our research are likely to assert that the intense use of emotionally charged discourse [

24,

25] reduces the overall quality of the journalistic product.

H3: Experts of this research are expected to contend that the use of audiovisual material enhances the overall quality of the journalistic product [

26].

Thematic analysis of interviews with journalism experts highlighted key aspects of quality in journalism. The experts emphasized that credibility relies on core journalistic principles, including effective questioning techniques and the use of reliable, diverse sources. They also highlighted the importance of investigative journalism, which faces challenges in the online media landscape [

27]. Quality also involves correct language use, effective source management, and informative lead paragraphs. Experts largely disapprove capital letters in news articles, finding them distracting, but support bullet points for clarity.

Moreover, according to the experts, the ideal article length varies based on news type and coverage depth, with some preferring concise texts to retain reader attention. Regarding impartiality, although considered a challenge due to inherent biases, experts agree that journalists should present all perspectives, even when expressing personal opinions. Based on experts’ responses, headlines should accurately reflect the article’s content, supporting the hypothesis that accuracy outweighs emotional appeal [

24,

25]. Experts also affirmed the value of audiovisual material in digital journalism, provided it’s relevant to the text, aligning with the third hypothesis (H

3) on its integral role in quality news content.

The insights provided by the experts on structuring journalistic discourse within a framework of qualitative and engaging journalistic writing were substantial and significant. However, a deeper analysis of the findings from this qualitative research method would be beyond the scope of this paper [

28].

The preliminary qualitative research findings, which emerged from the experts’ interviews, described several key issues: credibility, diversity of opinions and sources, language quality, text characteristics such as punctuation and article length, impartiality, importance of the headline, emotionality, and the role of accompanying audiovisual material. These main themes formed the basis for developing perceived quality indicators. In other words, experts’ insights on crafting high-quality, engaging journalistic articles were used as input features to train the machine learning model in Phase B of the study.

2.2. Phase B: Computational Model Development and Training

As mentioned in the previous research phase, the findings of the qualitative research, which derived from the interviews with the experts, identified key topics and characteristics that formed the foundation for the development of the quality indicators. These indicators were then used as input features for training the machine learning model in phase B of the study. This phase, therefore, examines the various steps involved in the computational approach, with the aim of building machine learning models able to predict the quality and engagement of online social media news.

2.2.1. Data Collection, Preprocessing, and Feature Extraction

Initially, in the second phase of the study, a text analysis was performed on a dataset of over 10 million Greek news articles published on news websites from the year 2021 to 2023. Specifically, the content was sourced from 7.359 Greek news websites, with articles selected from the following categories: Economy, Politics, International, Sports, Technology, Culture, Society, News, Health, Tourism, and Lifestyle. After tagging a representative sample of publications and analyzing all sites, approximately 2.5 million articles were selected. Before using the corpus, Python techniques were used to prepare the dataset to process stopwords, symbols, nonstandard words, remove NaN values, and HTML code from the texts. After the data cleaning stage, 902.133 unique texts of articles from high-quality news websites and 607.704 unique texts from tabloid websites remained.

For the creation of the sophisticated features that correspond to the theoretical framework various text analysis techniques, Python packages, and NLP libraries were utilized. These included tokenization, stemming, lemmatization, and part-of-speech tagging, along with many lexicons which required the original form of words. In other cases, the original text was used instead of the preprocessed text to identify adjectives or assess the readability of a text.

For sentiment analysis, we chose the dictionary method and used translated versions of emotion and subjectivity lexicons. Specifically, to assess subjectivity, we used the Multi-perspective Question Answering (MPQA) Subjectivity Lexicon by Wilson, Wiebe and Hoffmann [

29], freely available for research purposes. To measure emotionality, we utilized 3 established dictionaries: the NRC Word-Emotion Association Lexicon (Emolex), with 14.182 words associated with 8 basic emotions (anger, fear, anticipation, trust, surprise, sadness, joy, and disgust) at two levels (1 = associated, 0 = not associated) and two polarities (positive and negative); the National Research Council Canada Valence, Arousal and Dominance Lexicon (NRC-VAD) [

30], containing 20.000 words labeled with scores for Valence, Arousal, and Dominance; and the National Research Council Canada Affect Intensity Lexicon (NRC-AIL) [

31], with 5.815 terms rated by intensity for 4 basic emotions, anger, fear, joy, sadness [

32,

33].

The dependent categorical variable was determined by annotators: articles receiving at least two positive responses to the quality question were assigned a score of 1, while the rest were assigned a score of 0. Independent variables for the model were selected and operationalized based on the theoretical framework dimensions, which, according to the literature, define journalistic quality (refer to

Table 1 for measurement details). To examine general features across a large corpus, we employed a computer-assisted text analysis methodology, using concept measurement.

It should be noted that the aim of the study was to investigate, verify and evaluate the theoretical framework of quality in journalistic discourse, derived from the previous phases of the project and from the study of the literature, rather than simply constructing an efficient classifier, which could be achieved by simpler methods.

2.2.2. Machine Learning Model Development

To build the machine learning algorithms we used several classification models from the Python scikit-learn

6 library. In particular, we used seven different approaches, Naive Bayes, K-Nearest Neighbors, Logistic Regression, Support Vector Machine (SVM), Decision Tree, Random Forest, and the XGBoost classifier, which uses gradient boosting to create and add new trees to the previous model to improve prediction. For the experiments, 80% of the news articles were used for training purposes and the remaining 20% for testing. To evaluate the different classification methods, the weighted average F-measure (F1) was applied, which is derived from the average of accuracy and recall.

The process of text mining involves the use of techniques to extract and analyze information from unstructured textual data. Initially, three techniques were used for the baseline models, Bag of Words (bigrams and trigrams), TF-IDF (Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency) and the BERT language model. More specifically, we used the Bag of Words model, a feature extraction technique that represents text as a numerical vector, with each element indicating the frequency of a specific word. These vectors for each news story were then used as input for the machine learning algorithms.

To test our general hypothesis that certain features of a news story are related to quality, we used the corpus of newspapers as input for the machine learning models, which exploited the proposed features for training to predict the quality of an article. After the initial modeling, a series of analyses follows to interpret the machine learning models in order to make the hidden decision-making mechanisms apparent and to examine the importance of each dimension in more detail. In the stage of model explanation (Explainable AI), all available tools in Python language were used, SHAP

7, LIME

8, TreeInterpreter

9, Eli5

10, DTreeViz

11.

The corpus of online news stories was also used as input for the machine learning algorithms in order to test our hypothesis that certain inherent attributes of an article can influence its engagement on social media. To create the dependent variable about successful and unsuccessful articles on Facebook, we separated the data into two buckets, the low one consisted of articles belonging to the 5th percentile and had a value of 0, and the high to the 95th and was labeled as 1. We believed that in order to discover the hidden patterns behind engaging news content we should examine the really popular ones in contrast with the completely irrelevant ones in terms of engagement. Furthermore, we created 4 models, each one predicting a different engagement metric, namely Likes, Shares, Comments, and the number of Total Interactions that include the emojis of Love, Care, Haha, Wow and so on. The independent variables (see

Table 2) quantified some of the engagement and quality criteria from the literature that we believed can capture audience engagement with news on Facebook. From the 7.359 websites, after tagging a representative sample of posts and analyzing all websites in relation to user engagement with Facebook and Twitter posts, over 5 million articles were selected.

The engagement analysis also was based on tree models because according to previous work [

49,

50] these types of classifiers can be explained by providing in-depth interpretations of the model predictions. Therefore, we proceeded with a binary classification task and used three different approaches models from the scikit-learn Python library, namely a Decision Tree, a Random Forest, and an XGBoost. From the dataset, we used 80% for training and the remaining 20% was used for testing, while the F-measure (F1) was our preferred accuracy method. Finally, a series of explainability methods were also used to acquire a set of rules able to predict audience engagement.

At this stage of the research, the following research hypothesis was proposed:

H4: Lower levels of subjectivity and entertainment will predict higher quality, whereas higher levels of emotional content and poor language use will predict lower quality. The accuracy of the quality classification models is presented in

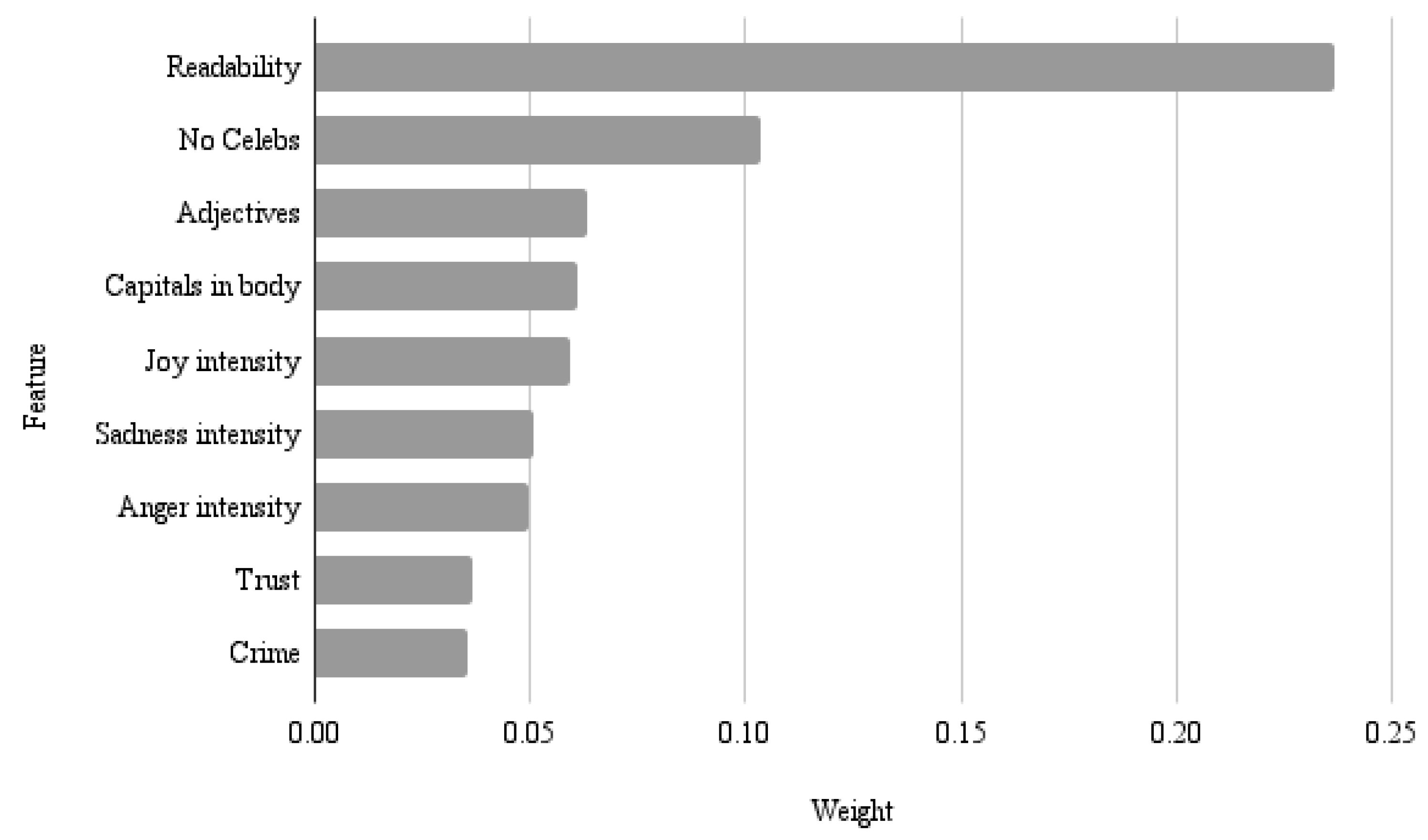

Table 3 and with the best models being the XGBoost classifier and Random Forest. The preferred classifier was able to correctly classify 85% of the news articles into high or low quality categories based on the identified features. The other models performed F1 scores ranging from 80% to 85%. To find the most important features, we used the ELI5 Python library for “Inspecting Black-Box Estimators” to get the permutation importance (

Figure 2). Therefore, the accuracy of the models indicates that the theoretical quality framework is effective in Greek articles.

Specifically, as shown in

Figure 2, readability is the primary predictor for the model. The concept of readability refers to the overall sum of all the features of a text and their interactions that affect whether a reader will read it successfully. The degree to which a text is successfully read lies in the extent to which readers understand it, retain the information taken in from it, read it at a satisfactory speed and find it interesting [

51].

Additionally, in the ranking, it appears that emotions play a particularly important role in prediction, with Anger Intensity, Joy & Sadness Intensity, and Trust ranking high. The number of adjectives and the presence of capitals in the body of the article are also important. Finally, the number of Celebrities appearing in the article seems to play a large role in prediction.

To enhance understanding of the predictions, we analyzed the graphical representation of a Decision Tree from the XGBoost classifier to propose rules related to journalistic quality. However, extracting all rules from a Decision Tree can become increasingly challenging as the tree expands, leading to greater complexity and reduced interpretability. Besides, the constraints are conjunctive along one path and different paths may provide contradictory information and require extra effort for post-processing the initial set of rules. To avoid these issues we applied measures of confidence and support and opted for the “most important” rules. Therefore, we selected the leaf nodes with a high probability to belong in class 0 (low quality) or class 1 (high quality), having a large number of samples (20% of the total training samples) at the tree construction phase where at the same time the misclassification error during the test phase for that specific leaf nodes remains very low (<0.1). Using Python’s DTreeViz library [

52], we visualized the algorithm’s decision-making process at the leaf nodes and based on the above preconditions for node selection, this approach supports confident generalization of the extracted rules.

The results identify six key rules for news discrimination based on nine important sub-dimensions of the framework. According to these rules (see

Table 4), a high-quality article tends to be difficult to read, suitable for people with at least a third-grade education or age 17 or older, and has words of fewer than six characters on average. In addition, such articles occasionally convey positive emotions, with the number of adjectives varying according to other characteristics of the text, such as length, references to famous people, or references to crimes, accidents, or conflicts. For journalistic articles that are more readable - understandable by people without a high school education or under 17 years old - the prediction model considers them to be of high quality if they contain less than 21% of words expressing joy. In addition, shorter texts (less than 243 words) should contain more than 15% of adjectives, while longer texts should contain words that convey emotions such as anger or confidence.

For the engagement prediction classification models, we conducted 3 experiments, each targeting a different variable: Likes, Shares, and Comments. Using three classifiers, the XGBoost model demonstrated the highest accuracy, achieving an F1-score of 91% for predicting Likes (see

Table 5). The Information Quality dimension is the most important with the number of words in the title to be constantly the best predictor among the three different engagement metrics, while the difficulty, length, and diversity features also appear high in the permutation importance table. Furthermore, all four dimensions of the framework are significant for the model, with Emotionality having anticipation, dominance, arousal, and valence as important features, Subjectivity in the body of the article and in the headline used on the Facebook post also influence prediction and finally from the Entertainment dimension, famous people are of importance. We observe that the significance of some features changes depending on the target variable, which is to be expected according to the literature [

53]. Therefore, the number of celebrities referred to in the text best predicts Comments and Likes and does not influence Shares, while the emotion of dominance is crucial for Likes, fear is only relevant for Likes and positivity for Comments.

By analyzing the five paths leading to the most important end nodes, a set of rules for this model emerged that can increase engagement rates if followed by professional journalists before they publish their stories on Facebook. In general, the basic rule is this: a story with a high likelihood of engagement tends to have an average word length of up to five characters, is easy to understand, includes positive language, and contains less than 11% adjectives. In addition, the story should express trust and include references to crimes, conflicts or accidents. If the article refers to famous people, evoking emotions such as fear or excitement is likely to improve engagement.

2.3. Phase C: User-Centered Design

The development of the intelligent text editor IQJournalism followed a design thinking approach, initially focusing on a deep understanding of the user’s specific requirements. This user-centered methodology then incorporated an iterative design process involving prototyping, testing, and redesigning [

54]. The design and development steps followed in creating the IQJournalism system are depicted in the figure below.

The first step involved conducting user research, in our case with journalists, in order to identify the needs and challenges they face during the writing process. These needs mainly concern the composition, editing and revision of the text, based on the system’s recommendations, as well as the management of text files and folders. Considering that journalists are already familiar with similar online tools, we examined widely used online writing assistants. Most of the authoring tools and AI assistants we evaluated shared common features, such as a minimalist design to support focused and interrupted writing, AI feedback displayed to the right of the text, and color-coded suggestions.

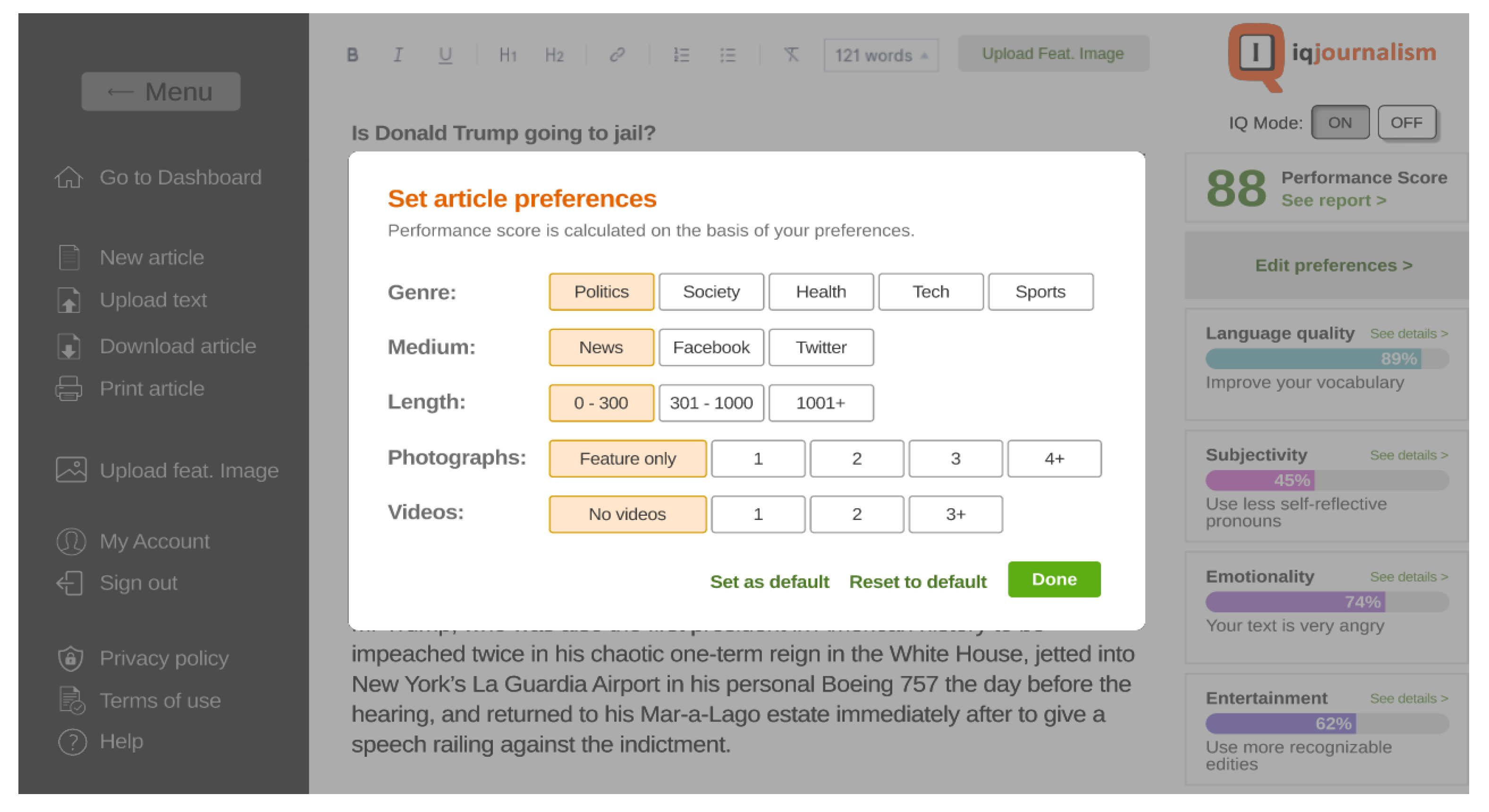

The above research led to the creation of a prototype design of the intelligent text editor. More specifically, during the ideation stage, we developed various design alternatives for the tool’s Homepage and User Dashboard using Drawio

12. As shown in

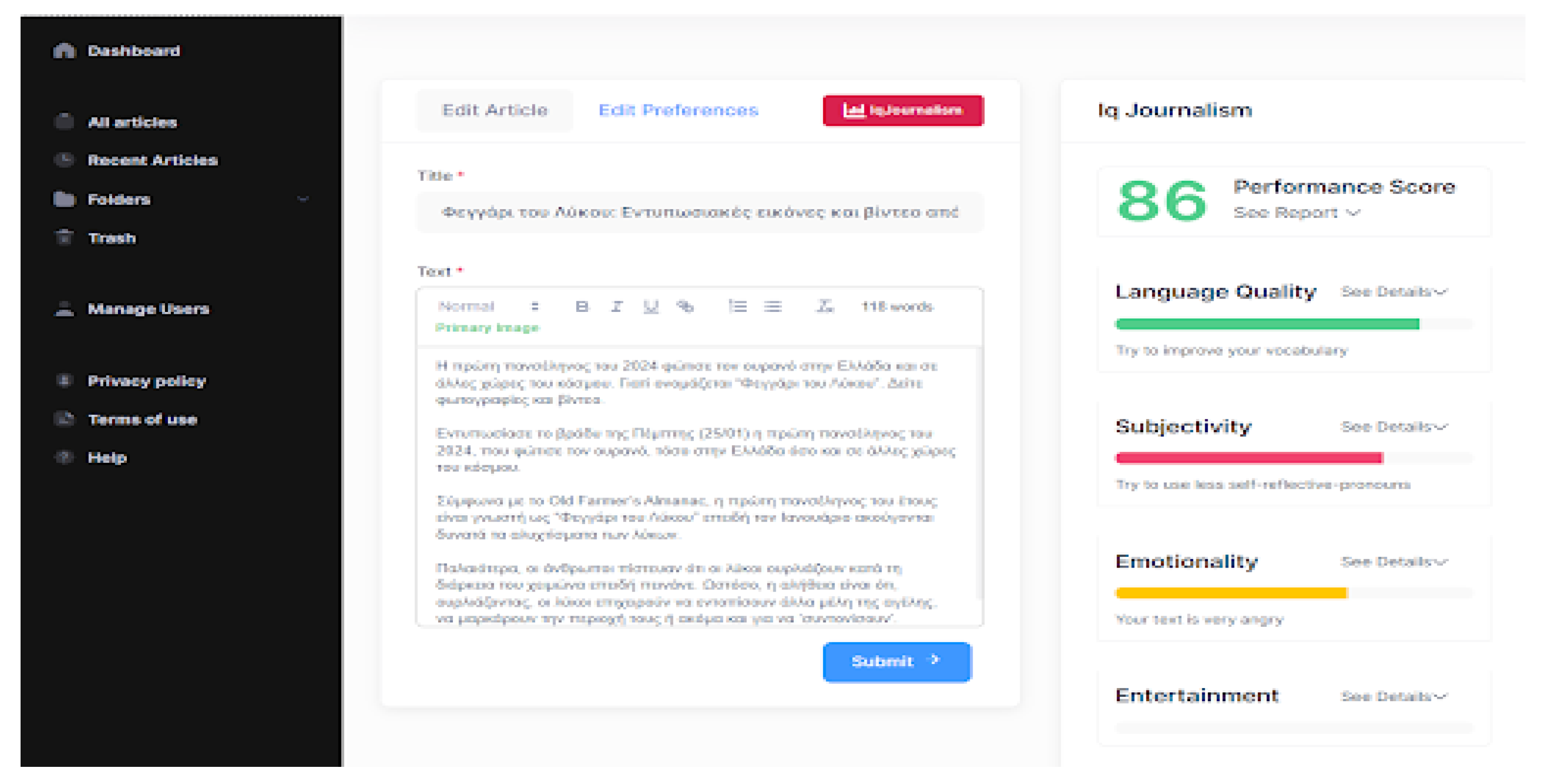

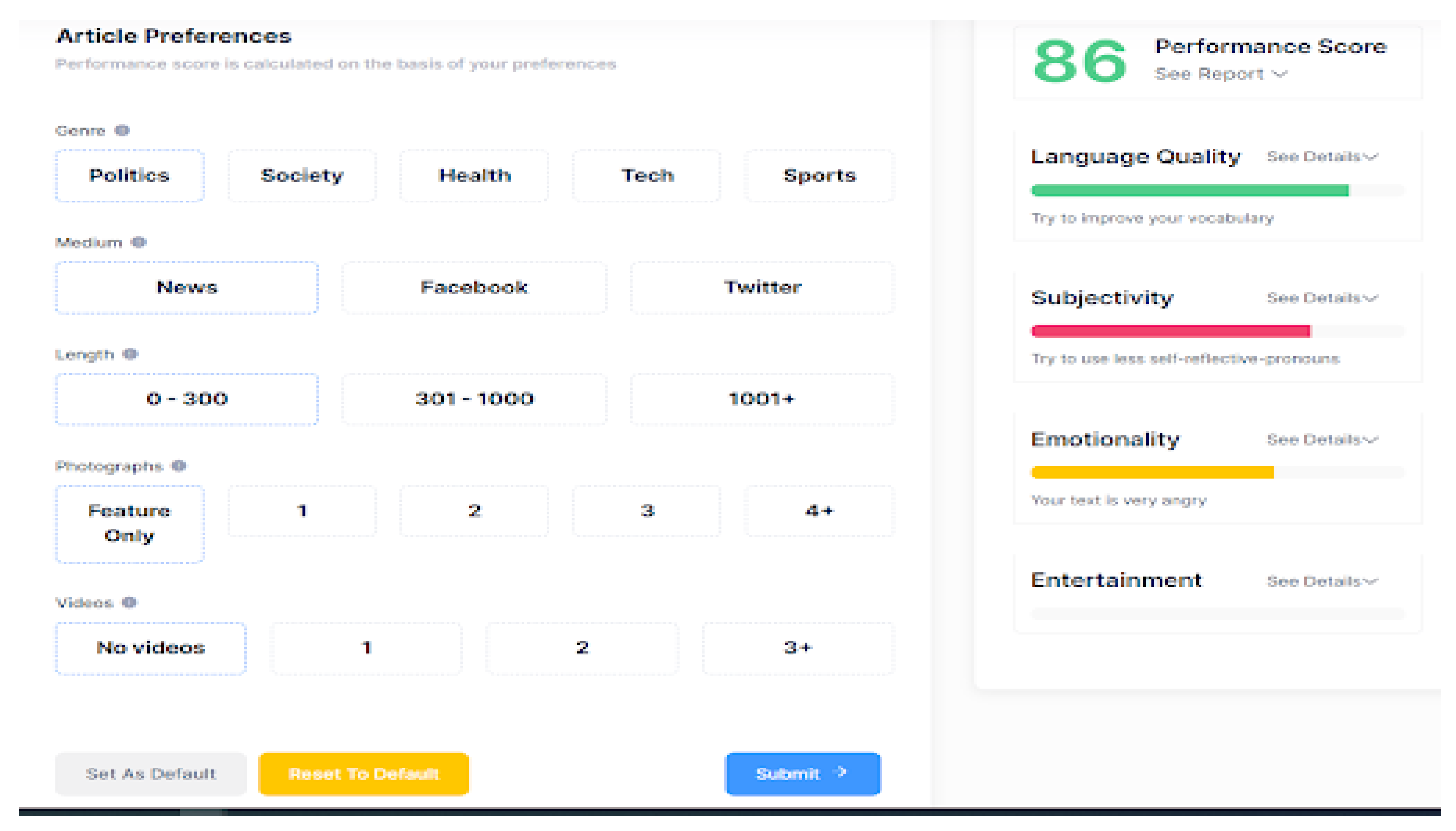

Figure 4, the text editing interface is centered, with a main menu on the left sidebar offering essential functions like saving and printing. The right sidebar provides text quality improvement suggestions in terms of “Language quality”, “Subjectivity”, “Emotionality”, and “Entertainment,” displayed through color progress bars for visual assessment. Users can access more details by clicking the “See details” hypertext under each factor. In the foreground, the “Text Preferences” pop-up window appears, where users at the beginning set article parameters such as the “Genre”, “Medium”, “Length of the text”, and multimedia inclusion of “Photographs” and “Videos”. This window is accessible anytime by clicking the “Edit Preferences” button.

This preliminary concept was tested with a focus group, gathering valuable user insights that helped refine the design prototype for greater usability [

55]. The focus group method facilitated group interaction, allowing us to adapt questions and gather important observations on the design of the system. This session included 10 Media Studies postgraduate students (8 female, 2 male, aged 23-40) with experience in using similar professional text editors/tools. After reviewing the designs, participants expressed preferences and suggested improvements for features such as the login button, menu items, color palette, IQ mode button, and performance score.

The next step involved refining the initial designs based on focus group feedback and creating an interactive functional prototype using Figma

13. This prototype allowed users to engage with the system’s computational layer, which assesses article’s perceived quality. Views and functionalities include a Homepage with a “Start Writing” prompt, top menu, and sign-up options; a User Dashboard for file management and document creation; and a Document Page, where users can adjust preferences, review system feedback through the I Q Mode button, and make necessary changes. The following diagram (

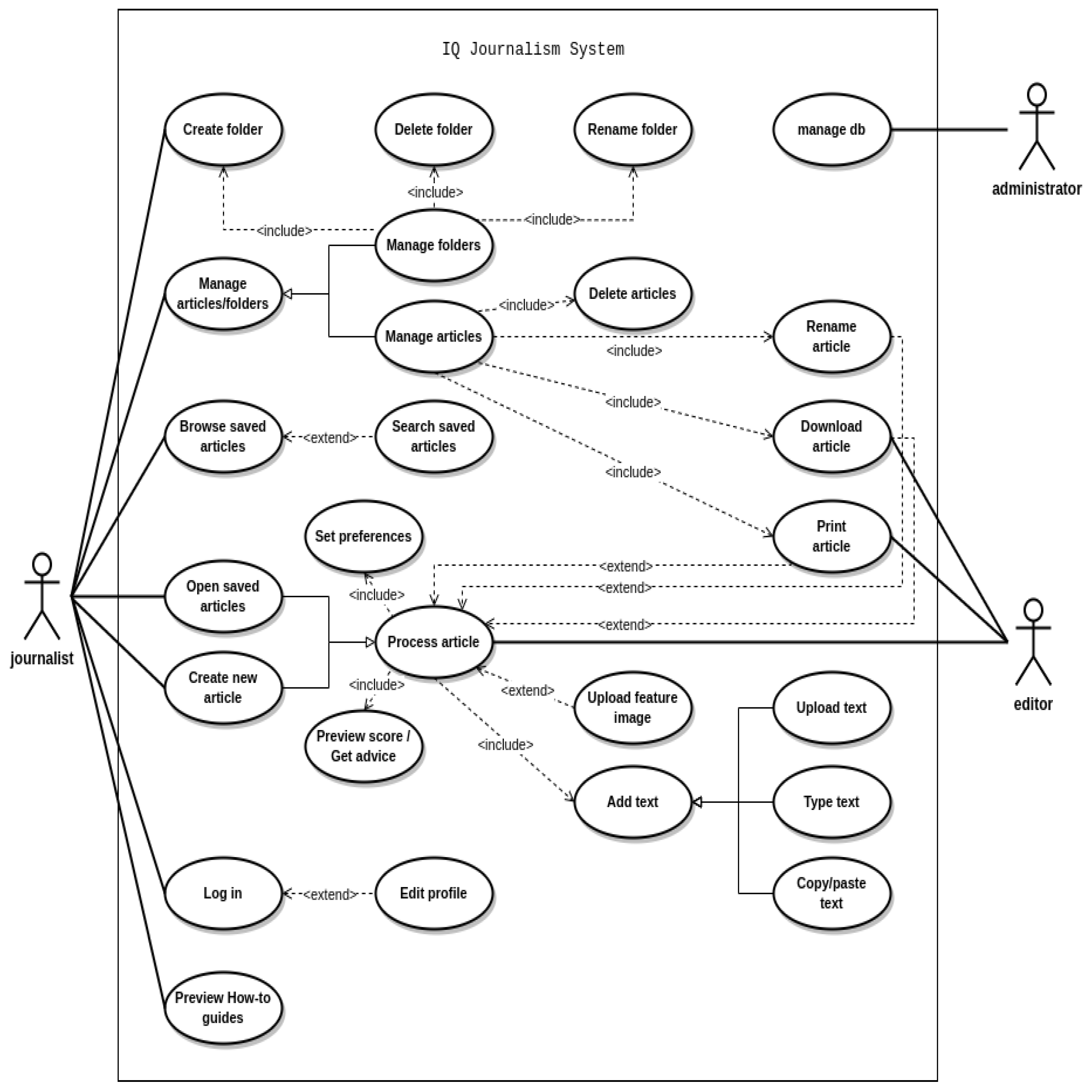

Figure 5) depicts a visual representation of the system’s entities. It provides a clear overview of the components, along with the interactions and actions available to the user.

Indicatively,

Figure 6 illustrates the main interface of the IQJournalism platform, which includes two sidebars that host tools and information. These sidebars can be displayed or hidden by pressing the IQJournalism button. The left sidebar (Menu) allows users to perform a variety of actions, such as creating new files, uploading or downloading text, printing documents, editing their profile, and accessing informational and help material related to the application. The right sidebar (IQJournalism) displays detailed analysis results provided by the platform. These results include assessments of the text’s language quality, subjectivity, emotionality, and entertainment value. At the top-right corner of the screen, the platform presents an overall performance score for the article, along with a button labeled “Edit Preferences” for defining or updating the article’s attributes.

As shown in

Figure 7, the “Edit Preferences” button opens a pop-up window that allows users to define or adjust the article’s attributes. This step is crucial for ensuring that the AI-generated analysis aligns accurately with the intended purpose of the content. Attributes can be updated at any time to adapt various publishing contexts, such as adapting content for Facebook or Twitter based on an article initially created and configured for print or online media.

To evaluate the IQJournalism prototype’s user experience, we conducted a moderated desirability (light) usability study over two weeks in May 2023 at the Department of Communication and Media Studies. For the purpose of the usability study 5 research hypotheses were formulated:

H5: There is a strong positive user experience when participants interact with the prototype [

56].

H6: The perceived usability score of all participants is higher than the standard average SUS score of 68 [

57].

H7: Participants’ NPS score is over 30, showing a clear tendency towards recommending IQJournalism system [

58].

H8: Participants’ scores distribution with respect to their overall experience and satisfaction with the prototype show a central tendency towards the top values (strong attitudes) of the subsequent Likert scales.

H9: The majority of the participants performed faster and more effectively (i.e., SWA < 1) when they interacted with the various tasks of the prototype.

The study involved 20 postgraduate students (18 female, 2 male) aged 20-35, experienced in journalism and familiar with online editing tools. Each participant, guided by one or two moderators, performed situation-specific tasks designed to provide both implicit and explicit feedback. Participants completed 3 tasks: uploading a text file to assess its predicted performance, modifying article preferences to observe changes in performance scores, and improving the language quality score before downloading the file. Task performance was recorded, including timing and assistance levels. To capture usability and desirability, we used several assessment approaches: the User Experience Questionnaire (UEQ), System Usability Scale (SUS), Product Reaction Cards, perceived satisfaction items, Net Promoter Score (NPS), and open-ended questions. These tools allowed us to gather insights into user satisfaction and acceptance, combining qualitative feedback and quantitative measures like NPS, which indicated participants’ likelihood of recommending IQJournalism.

Participants also completed a Google Forms survey that documented demographic information, experience with web-based editors, and expertise at editing and authoring tasks. This valuable feedback highlighted the prototype’s strengths in visual design, ease of use, and usefulness, alongside areas for further refinement. The final step in the user-centered iterative process involved refining IQJournalism’s design and functionality based on user feedback and testing. Iterative improvements enhanced the tool’s usability, effectiveness, and overall user experience, leading to a fully functional version. This phase included the development and integration of a complete software solution encompassing machine learning algorithms and complementary features into the text editor, as described in Phase B of the methodology.

3. Results

The evaluation results of IQJournalism focused on user experience, usability, satisfaction, and user performance with the various tasks of the IQJournalism prototype.

3.1. User Experience

Using the UEQ focusing on Pragmatic Quality, which measures task-oriented aspects such as efficiency and ease of use, as well as Hedonic Quality, which assesses fun, appeal, and overall originality of the experience provided by a system, participants rated IQJournalism highly on both conditions with Cronbach’s alpha reliability scores above 0.7 (

= 0.72 for the Pragmatic and

= 0.80 for the Hedonic qualities respectively). The scores and benchmarking interpretation of UEQ [

56] were the following: Pragmatic quality scored 1.81 (“Excellent”), Hedonic quality: 1.12 (“Above Average”), and overall experience scored 1.47 (“Good”). Additionally, using Product Reaction Cards, positive attributes like “Easy to use” and “Friendly” were described by 80% and 70% of users respectively, 55% of users described it as “Clean” and 50% as “Efficient”, while few selected negative terms like “Sterile” (5%) or “Inconsistent,” (5%). All these scores indicated strong user acceptance, simultaneously confirming H

5.

3.2. SUS and NPS

The SUS baseline score of 82.5 indicated high perceived usability, with standard deviation of 7.8, well above the threshold of 68 (above average [

59]). Therefore, the evaluation of the IQJournalism prototype revealed that the participants’ interaction with the specific tasks positively affected their perceived usability. Consequently, the research hypothesis related to the usability of the system was accepted (H

6). The NPS score of 40 (Mdn = 8.5, IQR = 7.75), showed a high likelihood of recommendation and consequently confirmation of the seventh hypothesis. Based on the scale categories outlined by Reichheld [

60], the IQJournalism prototype received the following score allocations from a total of 20 participants: 5 participants (25%) responded with a score of 10 and 5 participants (25%) responded with a score of 9 (categorized as Promoters); while 2 (10%) participants fell into the category of Detractors (scoring 5 and 6). Among the users categorized as Passives, 8 participants (40%) responded with a score of 7 and 8. These results suggested that participants exhibited enthusiasm towards IQJournalism, generating positive word-of-mouth among colleagues and potential users of the proposed system [

61]. Concerning its correlation with SUS (noted to have a strong positive correlation of 0.61 with NPS - [

61], the overall perceived usability score initially appears to justify the observed NPS score. However, a higher score close to, e.g., 70 [

62] for NPS could be expected. This suggests that the first version of the interactive prototype provided to participants may have affected their perception, especially when compared to a fully functional version of the tool that could address factors such as faster response times and guidance during the tasks’ execution.

3.3. Satisfaction

Regarding users’ perceived satisfaction and performance, we observed a generally positive consensus. The central tendency of the participants’ scoring preference is concentrated towards the highest values (strong positive attitudes) of the scales (i.e. 5, 6 and 7). On the question “How easy is it to deal with IQJournalism for doing your job?”, the participants provided positive feedback (M = 6, SD = 1.02), with 20% selecting 5 on the scale, 60% selecting 6 and 35% selecting 7. Regarding the statement “Using the data from the various system’s views (e.g., articles’ preferences, predicted performance), I can self-reflect and get a good understanding of my performance”, 85% of the participants expressed general agreement with the statement (M = 5.3, SD = 1.08). Additionally, 90% of the participants provided a positive response to the question “How would you rate your overall satisfaction with the IQJournalism prototype?” (M = 5.65, SD = 1.03). Concerning the last item, given its negative phrasing, we were expecting to observe a concentration of scores towards the more negative values of the scale (i.e., 1, 2 and 3). This expectation was confirmed, as 85% of participants disagreed (M = 2.05, SD = 1.35) with the statement: “When I interact with the various views of IQJournalism, (e.g., data entry, dashboard, preferences) for accomplishing my tasks, I usually feel uncomfortable and emotionally loaded (i.e., stressed-out/ overwhelmed)”.

The combination of the aforementioned results supports the acceptance of hypothesis H8. Participants found the system to be engaging and easy to use, demonstrating an awareness of their performance while interacting with the various features of the prototype. Moreover, users reported not feeling stressed or overwhelmed during their interactions with the system and expressed overall satisfaction with the experience.

3.4. Task Performance

During the study, users had to complete three main tasks, capturing SWA, completion time, and open-ended feedback. To test H

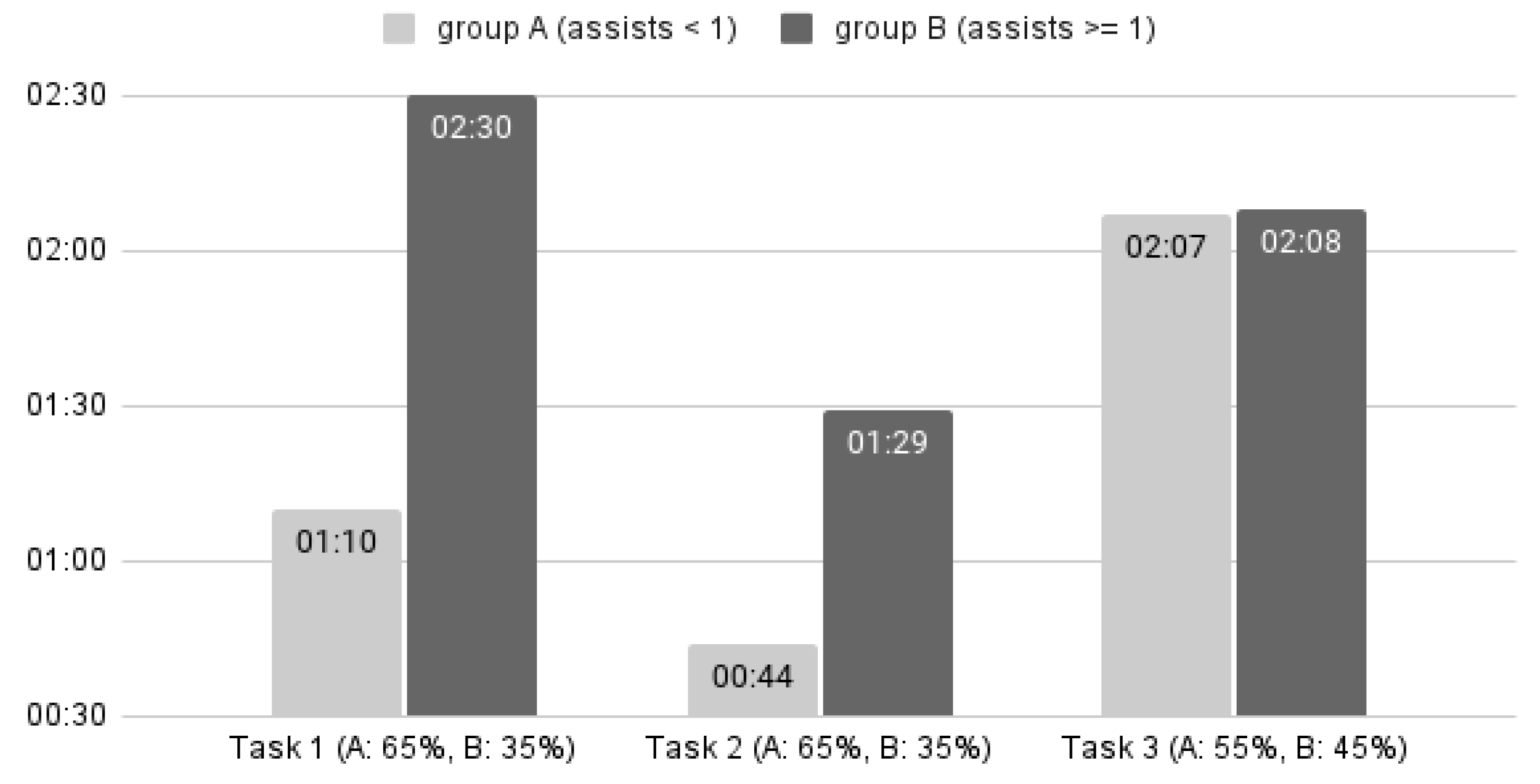

9, which states that the majority of the participants performed faster and more effectively (i.e., SWA < 1) when they interacted with the various tasks of the prototype, participants were split into two groups: Group A consisted of the participants who managed to complete the 3 tasks without significant assistance (i.e., SWA < 1), and Group B included participants that needed more support during interaction (i.e., SWA >= 1). Overall, a positive correlation was observed between assists and time for each task. For tasks 1 and 2 we observe a strong positive correlation r = 0.71 and r = 0.65, respectively, and for task 3 a weak positive correlation r = 0.15. This indicates that users in Group A (the majority) completed the tasks more quickly than those in Group B. We then represent the results for each task (see

Figure 8), with the coefficient of variation (CV) calculated for each group to better understand the relative variability of the data, respectively:

For task 1 study participants were asked to upload a text file on IQJournalism and see its predicted performance. The participants had first read the article in order to gain an overview of its genre and content. Group A users (65%, CV = 34.8%) completed the task with an average time of M = 01:10, SD = 00:24, and had a mean SWA score M = 0, SD = 0 indicating no significant assistance from the moderators. In contrast, for Group B users (35%, CV = 39.6%), the mean time of completion was M = 02:30, SD = 00:59 and the average SWA score was M = 1, SD = 0, indicating they needed more support. Therefore, users who did not receive assistance completed this task significantly faster. Considering the respective qualitative input from the users, 11 (N = 20) of them stated that the interaction with the system was easy, user-friendly and the system output was understandable, while 4 (N = 20) users c had difficulty quickly locating the IQ Mode button.

As for the task 2 users were required to edit the article’s preferences and review the changes in the system’s output. Group A users (65%, CV = 59.3%) completed this task within an average time of M = 00:44, SD = 00:26, and average SWA score of M = 0, SD = 0. On the contrary, for Group B (35%, CV = 87.9%), the average completion time was M = 01:29, SD = 01:18 and the average SWA score was M = 1, SD = 0.4. Also users with low SWA scores were able to perform faster during the execution of task 2. In their open-ended responses, users stated that the task was easy to complete and that the changes in performance scores were clear. However, 6 participants (N = 20) mentioned that they had difficulty in locating the edit preferences button.

For task 3 study participants were asked to edit the article in order to improve the language quality score, download the article and sign out. In detail, Group A (55%, CV = 61.8%) completed task 3 within an average time of M = 02:07, SD = 01:19. The average SWA score for Group A was M = 0.4, SD = 0.2. For Group B (45%, CV = 24.9%), the average completion time was M = 02:08, SD = 00:32 and the average SWA score was M = 1.1, SD = 0.17. In contrast to tasks 1 and 2, task 3 showed a weak correlation between completion time and SWA (r = 0.15), and users took longer to complete the task, regardless of the assistance provided. According to the qualitative feedback, participants faced some challenges with this task, which were addressed in the iterations of the prototype and the tool. Indicatively, many users reported that they expected more guidance by the system, they did not notice the system’s advice on improving the language quality score, and had difficulty in locating the download button. Nevertheless, it can be argued that users in Group A completed the task almost as fast as those in Group B, even though they received no help.

After implementing iterative adjustments and improvements based on the findings from the usability study, the fully functional version of the system will be developed. IQJournalism system integrates a comprehensive software solution, incorporating machine learning algorithms alongside complementary features into the text editor.

4. Discussion

The IQJournalism project showcases the potential of integrating journalism principles with machine learning techniques and user-centered design to enhance the quality and engagement of journalistic content. The research methodology began with expert interviews (Phase A) to identify key indicators of perceived quality in journalism directly addressing the first three research questions concerning the fundamental characteristics of journalistic quality, reliability, and impartiality. The thematic analysis of these interviews showed the fundamental principles of journalism. The majority of respondents attributed the credibility of a news medium to three main characteristics; the inclusion of essential information (what, where, who, when, and why), the presence of sources in the text, and the pluralism of opinions or information. Additionally, the correct language use that respects spelling, syntactic, and grammatical rules was also considered an important component of quality content. Comprehensible and simple writing was recommended as a standard, with experts emphasizing clarity while rejecting colorism, subjectivity, emotional and biased discourse.

Furthermore, the findings validated the first research hypothesis (H

1) as the majority of experts affirmed that headlines should mainly serve as accurate leads to the journalistic text. Additionally, in addressing the role of emotionality, the second research hypothesis (H

2) was similarly confirmed. Experts prioritized the accuracy of reporting over the attempt to evoke the readers’ feelings [

24,

25]. Nevertheless, they stressed that journalistic text should not be completely free of emotion. Emotionality should complement the reporting of accurate information, enhancing the storytelling while maintaining the actual core of the narrative.

Finally, the importance of audiovisual material in digital journalism [

26], was explored to test the third research hypothesis (H

3). Experts recognized audiovisual content as an integral element of contemporary journalism, provided it is relevant to the accompanying text. The only prerequisite they underlined is that any kind of audiovisual material should be relevant to the content of the text it escorts. The results of this study are in line with a number of attributes based on the theoretical foundations of journalistic quality. More specifically, the Language Quality dimension emerged as the most influential in determining content of high or low quality, with readability, length, and image-to-text ratio playing key roles.

The second phase (Phase B) involved building and evaluating machine learning models, where features, derived from the expert-defined theoretical framework, were tested for their predictive power. Models like XGBoost and Random Forest achieved impressive F1 scores reaching up to 85% for classifying article quality, verifying the effectiveness of the framework. Addressing the following research question -how AI can provide a nuanced understanding of journalistic quality- the findings demonstrated that machine learning models effectively captured the multifaceted nature of quality through the expert-defined dimensions of Language Quality, Subjectivity, Emotionality, and Entertainment. To the query whether the model dimensions could predict quality in online news, the results confirmed this by disclosing the distinct contribution of linguistic and contextual elements. In particular, emotions like anger, joy, and trust, as well as the presence of celebrities and the use of adjectives, played crucial roles, highlighting the correlation between linguistic and contextual factors in quality prediction.

Additionally to the research question that investigated whether machine learning models could accurately predict social media engagement, the prediction experiments targeted specific metrics, Likes, Shares, and Comments, with XGBoost achieved an F1 score of 91% for Likes. Title length, emotionality, and references to celebrities emerged as significant predictors. For instance, positivity enhanced Comments, while fear and dominance were linked to Likes. These findings indicated the importance of tailoring content to audience preferences while maintaining journalistic integrity.

The final phase of the methodology (Phase C) involved a user-centered iterative approach to the design of the IQJournalism system. The aim of this approach was to understand the specific user requirements through an iterative design process involving prototyping, testing, redesign and implementation. The needs and challenges faced by journalists and editors in the content writing process were collected. Subsequently, the collection of this data led to the creation of a design prototype for the assisting text editor. The early designs were then presented to a focus group in order to identify potential issues and gain insights into the usability challenges or areas for enhancements. In the next stage, the findings of the focus group identified the improvements required to create an interactive prototype.

To test the effectiveness and acceptance of the interactive prototype, a desirability (light) usability research study was conducted with 20 users. The preliminary research findings showed a positive user experience and acceptance of the system prototype, also offering significant points for improvement to move to the final stage of the user-centered iterative process and the integrated development of the system. The final phase involved iterating the design based on users’ feedback and testing that led to the improvement of the interactive prototype and then developing the fully functional version of the system.

Through open-ended questions, valuable information was obtained about the participants’ general perception of the IQJournalism system. The majority of the 20 users were satisfied with their interaction with the tool, underscoring its usefulness in terms of saving effort and time. Participants particularly stressed the system’s importance for improving content written in Greek language. They also acknowledged its exploitation by young editors, social media copywriters and university students who are often asked to write essays. In addition, one participant recognized the intended use of the tool as an additional evaluation step “especially for harder tasks, as it gives some feedback before the evaluation of chief editors/readers”. Moreover, study participants expressed strong liking for the user-friendly interface and the color selection, highlighting these features as the most significant and aesthetically pleasing aspects of the system. Study participants also appreciated the visual bars of scores and percentages and, most notably, the “word counter” indicator which was mentioned as a useful feature. In contrast, in terms of the least liked features of the system, 5 participants described the design as outdated. At the same time, they stressed the need to accurately identify the parts of the text proposed to be improved and were dissatisfied with the lack of tracking of the changes implemented.

Furthermore, regarding the question about the improved functional version of the IQJournalism system, the most predominant response given by users was again the necessity for more detailed feedback on text passages that could be improved. Additionally, users suggested incorporating auto-generation features, including attributes such as keywords generation, synonym recommendations, and “suggestions on how to enrich the article with media (photos, videos etc).” Two participants asked for “spelling, grammar, syntax checks always on”, as well as a text reading time indicator. Ideally, one user suggested using the tool “as an add-on for Word or Wordpress.”

Overall, the usability evaluation of the IQJournalism platform verified its effectiveness and user satisfaction, aligning with the proposed hypotheses. More specifically, the fifth research hypothesis (H5) was confirmed, as the UEQ ratings indicated a strong positive user experience, with scores for Pragmatic Quality (1.81) and Hedonic Quality (1.12) exceeding benchmarks for usability and enjoyment. The sixth research hypothesis (H6) was also supported, with the SUS score of 82.5 exceeding the standard average of 68, demonstrating high perceived usability. Furthermore, the seventh hypothesis (H7) was validated by the NPS score of 42, indicating a strong tendency among participants to recommend the platform to others. The eighth hypothesis (H8) was confirmed as participants consistently rated their satisfaction with the platform’s functionality and usability toward the higher end of the Likert scales. Similarly, hypothesis H9 was confirmed as task performance analysis showed that most participants completed tasks faster and more effectively (SWA < 1) when interacting with the prototype, although minimal guidance was required for specific tasks such as understanding quality scores and navigating certain features.

The progress of the interactive prototype was driven by iterative adjustments based on the feedback from the usability study, ensuring improvements in usability and user experience. The user-centered design process proved essential to the refinement of the platform, allowing for the incorporation of analysis features. This iterative approach transformed the prototype into a fully functional tool that effectively meets its objectives. Specifically, the final implementation of IQJournalism combines machine learning insights with user-friendly design, offering journalists a tool to enhance content quality and audience engagement. The ability to customize features for different publishing contexts allows for flexibility and adaptability, making the platform a useful service for newsrooms facing the challenges of digital journalism. The project not only contributes to the state of journalism technology, but also provides a roadmap for future research and development in the media sector.

5. Conclusions

This paper outlines the development of the IQJournalism system, integrating both qualitative and quantitative research methodologies across three distinct phases. Initially, the in-depth research conducted by analyzing various online editors and writing assistants was presented. This study was helpful in understanding the existing text editing and revision tools based on the system recommendations. Next, the paper presents key insights derived from 20 semi-structured interviews with journalism experts, which helped identify critical indicators of journalistic quality. The paper then explores the stages of knowledge extraction, including data collection, preprocessing, transformation, data mining, and interpretation/evaluation, all aimed at identifying meaningful patterns and features for model training. These features were subsequently used as input for machine learning classification algorithms. Evaluation metrics were provided to evaluate the performance of the models, leading to the selection of the optimal model. Finally, the paper analyzes the user-centered methodology employed to meet the needs of journalists and editors, highlighting the iterative process of prototyping, testing, refining, and finally implementing the system.

The IQJournalism project addressed critical challenges in the modern media ecosystem. By combining qualitative insights from expert interviews with advanced machine learning techniques as well as user-centered design principles, the project successfully developed an AI-assisted intelligent text editor to support and enhance journalistic practices. The system provides real-time feedback on language quality, subjectivity, emotionality, and entertainment, empowering journalists to produce reliable, engaging, and high-quality content.

However, this project has certain limitations. The machine learning models were developed and trained exclusively based on a dataset of Greek news articles. As a result, its linguistic adaptability is restricted to the Greek language and context. The intelligent advisor’s recommendations, designed to address nuances specific to Greek journalistic practices, are not directly applicable to other languages. This limitation highlights the need for future work to extend the capabilities of the system to other languages, allowing for a wider application of AI in improving the quality of journalism at a national level.

As the media landscape continues to evolve, AI-powered tools such as IQJournalism play a vital role in supporting newsrooms’ processes, content quality and fostering greater audience engagement. Based on editors’ feedback and the changing needs of the media industry, AI has the potential to both improve and transform digital journalism.

Acknowledgments

This research has been co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund of the European Union and Greek national funds through the Operational Program Competitiveness, Entrepreneurship and Innovation, under the call RESEARCH – CREATE – INNOVATE (project code:T2EDK-04616). The authors express their sincere appreciation to all those who contributed to the various stages of this research, with special thanks to Katerina Mandenaki, Antonis Armenakis, Stamatis Poulakidakos, and Spiros Moschonas for their expertise and invaluable support during Phase A: Qualitative Research, as well as to Theodoros Paraskevas and Irene Konstanta for their significant contributions to Phase C: User-Centered Design.

References

- Hendrickx, J.; Truyens, P.; Donders, K.; Picone, I. The media for democracy monitor 2021. How leading news media survive digital transformation 2: Flanders (Belgium): News diversity put under pressure. In The media for democracy monitor 2021: How leading news media survive digital transformation (2); Nordicom, 2021; pp. 8–41.

- Kalogeropoulos, A.; Rori, L.; Dimitrakopoulou, D. ‘Social Media Help Me Distinguish between Truth and Lies’: News Consumption in the Polarised and Low-trust Media Landscape of Greece. South European Society and Politics 2021, 26, 109–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. Social research methods; Oxford university press, 2016.

- Lacy, S.; Rosenstiel, T. Defining and measuring quality journalism; Rutgers School of Communication and Information New Brunswick, NJ, 2015.

- Rosenstiel, T. The elements of journalism: What newspeople should know and the public should expect; Three Rivers Press, 2014.

- Bhat, A.; Shrivastava, D.; Guo, J.L. Approach intelligent writing assistants usability with seven stages of action. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2304.02822 2023.

- Fitria, T.N. Grammarly as AI-powered English writing assistant: Students’ alternative for writing English. Metathesis: Journal of English Language, Literature, and Teaching 2021, 5, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, A.; Coenen, A.; Reif, E.; Ippolito, D. Wordcraft: story writing with large language models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Intelligent User Interfaces, 2022, pp.

- Zhao, X. Leveraging artificial intelligence (AI) technology for English writing: Introducing wordtune as a digital writing assistant for EFL writers. RELC Journal 2023, 54, 890–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, B. Wings: writing with intelligent guidance and suggestions. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of 52nd annual meeting of the association for computational linguistics: System demonstrations, 2014, pp. 25–30.

- Stefnisson, I.; Thue, D. Mimisbrunnur: AI-assisted authoring for interactive storytelling. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on artificial Intelligence and Interactive Digital entertainment, 2018, Vol. 14,pp.236–242.

- Li, J. [Retracted] English Writing Feedback Based on Online Automatic Evaluation in the Era of Big Data. Mobile Information Systems 2022, 2022, 9884273. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, O.; Buschek, D. Characterchat: Supporting the creation of fictional characters through conversation and progressive manifestation with a chatbot. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 13th Conference on Creativity and Cognition, 2021, pp. 1–10.

- Osone, H.; Lu, J.L.; Ochiai, Y. BunCho: ai supported story co-creation via unsupervised multitask learning to increase writers’ creativity in japanese. In Proceedings of the Extended Abstracts of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; 2021; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Paraskevas, T.; Konstanta, I.; Germanakos, P.; Sotirakou, C.; Karampela, A.; Mourlas, C.; Gekas, C. Measuring the Desirability of an Intelligent Advisor for Predicting the Perceived Quality of News Articles. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference of the ACM Greek SIGCHI Chapter, 2023, pp. 1–8.

- Phellas, C.N.; Bloch, A.; Seale, C. Structured methods: interviews, questionnaires and observation. Researching society and culture 2011, 3, 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- DiCicco-Bloom, B.; Crabtree, B.F. The qualitative research interview. Medical education 2006, 40, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, D. Qualitative Interview Design: A practical guide for novice investigators in The Qualitative Report, Vol. 15, 2010.

- Alsaawi, A. A critical review of qualitative interviews. European Journal of Business and Social Sciences 2014, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, M.; et al. General guidelines for conducting interviews. Saatavissa: http://managementhelp. org/evaluatn/intrview. htm (Luettu 21.8. 2015). 2009.

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fereday, J.; Muir-Cochrane, E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International journal of qualitative methods 2006, 5, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhojailan, M.I. Thematic analysis: a critical review ofits process and evaluation. In Proceedings of the WEI international European academic conference proceedings, Zagreb, Croatia. Citeseer; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, M.; Shazali, M. The interpretation of implicature: A comparative study between implicature in linguistics and journalism. Journal of language teaching and research 2010, 1, 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Wahl-Jorgensen, K. The strategic ritual of emotionality: A case study of Pulitzer Prize-winning articles. Journalism 2013, 14, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harcup, T.; O’neill, D. What is news? News values revisited (again). Journalism studies 2017, 18, 1470–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molyneux, L.; Holton, A. Branding (health) journalism: Perceptions, practices, and emerging norms. Digital journalism 2015, 3, 225–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotirakou, C.; Mandenaki, K.; Poulakidakos, S.; Armenakis, A.; Moschonas, S.; Karampela, A.; Mourlas, C. Deliverable 2.2: Analysis of journalistic texts using traditional quality assessment techniques 2023.

- Wilson, T.; Wiebe, J.; Hoffmann, P. Recognizing contextual polarity in phrase-level sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of human language technology conference and conference on empirical methods in natural language processing, 2005, pp. 347–354.

- Mohammad, S. Obtaining reliable human ratings of valence, arousal, and dominance for 20,000 English words. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 56th annual meeting of the association for computational linguistics (volume 1: Long papers), 2018, pp. 174–184.

- Mohammad, S.M. Word affect intensities. arXiv preprint, arXiv:1704.08798 2017.

- Plutchik, R. A general psychoevolutionary theory of emotion. In Theories of emotion; Elsevier, 1980; pp. 3–33.

- Ekman, P. An argument for basic emotions. Cognition & emotion 1992, 6, 169–200. [Google Scholar]

- Steensen, S. The intimization of journalism. Handbook of Digital Journalism Studies. 2016, pp.113–127.

- Lasorsa, D.L.; Lewis, S.C.; Holton, A.E. Normalizing Twitter: Journalism practice in an emerging communication space. Journalism studies 2012, 13, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, S. Source diversity in US online citizen journalism and online newspaper articles. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Online Journalism, Vol. 4; 2008; pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Flesch, R. A new readability yardstick. Journal of Applied Psychology 1948, 32, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quandt, T. (No) News on the World Wide Web?: A Comparative Content Analysis of Online News in Europe and the United States. Journalism Studies 2008, 9, 717–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harcup, T. Journalism: principles and practice 2021.

- Bogart, L. Press and public: Who reads what, when, where, and why in American newspapers; Routledge, 1989.

- Horne, B.; Adali, S. This just in: Fake news packs a lot in title, uses simpler, repetitive content in text body, more similar to satire than real news. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the international AAAI conference on web and social media, 2017, Vol. 11,pp.759–766.

- Cohen, J. Defining identification: A theoretical look at the identification of audiences with media characters. In Advances in foundational mass communication theories; Routledge, 2018; pp. 253–272.

- Chakraborty, A.; Paranjape, B.; Kakarla, S.; Ganguly, N. Stop clickbait: Detecting and preventing clickbaits in online news media. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE/ACM international conference on advances in social networks analysis and mining (ASONAM). IEEE; 2016; pp. 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Sparks, C. Introduction: Tabloidization and the media. Javnost–The Public 1998, 5, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, C. Emotion aside or emotional side? Crafting an ‘experience of involvement’in the news. Journalism 2011, 12, 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantti, M. The value of emotion: An examination of television journalists’ notions on emotionality. European Journal of Communication 2010, 25, 168–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, S. Popular news in the 21st century Time for a new critical approach? Journalism 2008, 9, 266–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoemaker, P.J.; Cohen, A.A. News around the world: Content, practitioners, and the public; Routledge, 2012.

- Lundberg, S.M.; Erion, G.; Chen, H.; DeGrave, A.; Prutkin, J.M.; Nair, B.; Katz, R.; Himmelfarb, J.; Bansal, N.; Lee, S.I. From local explanations to global understanding with explainable AI for trees. Nature machine intelligence 2020, 2, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 22nd acm sigkdd international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining, 2016, pp. .785–794.

- Tzimokas, D.; Mattheoudaki, M. , Readability indicators: Issues of application and reliability. In Major Trends in Theoretical and Applied Linguistics Volume 3; Versita, 2014; pp. 367–384.

- Parr, T.; Howard, J. The Mechanics of Machine Learning; 2018.

- Park, C.S.; Kaye, B.K. Applying news values theory to liking, commenting and sharing mainstream news articles on Facebook. Journalism 2021, 24, 633–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preece, J.; Sharp, H.; Rogers, Y. Interaction Design: Beyond Human-Computer Interaction; John Wiley & Sons, 2015.

- Abras, C.; Maloney-Krichmar, D.; Preece, J.; et al. User-centered design. Bainbridge, W. Encyclopedia of Human-Computer Interaction. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications 2004, 37, 445–456. [Google Scholar]

- Hinderks, A.; Schrepp, M.; Thomaschewski, J. A benchmark for the short version of the user experience questionnaire. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies-APMDWE. SciTePress,2018,pp.373–377.

- Lewis, J.R.; Sauro, J. Item benchmarks for the system usability scale. Journal of Usability studies 2018, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, D.; Berent, M.; Thomas, R.; Krosnick, J. Measuring customer satisfaction and loyalty: Improving the ‘Net-Promoter’score. In Proceedings of the Poster presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Association for Public Opinion Research, New Orleans, Louisiana, Vol. 19. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sauro, J. Measuring usability with the system usability scale (SUS) 2011.

- Reichheld, F.F. The one number you need to grow. Harvard business review 2003, 81, 46–55. [Google Scholar]

- Sauro, J. Does better usability increase customer loyalty?, 2010.

- Sauro, J. The challenges and opportunities of measuring the user experience. Journal of Usability Studies 2016, 12, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

| 1 |

|

| 2 |

|

| 3 |

|

| 4 |

|

| 5 |

|

| 6 |

|

| 7 |

|

| 8 |

|

| 9 |

|

| 10 |

|

| 11 |

|

| 12 |

|

| 13 |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).