1. Introduction

The solar PV generation has reached up to 1000 TWH globally, with a record of 179 TWH (up to 22% ) in 2021 alone, primarily due to its cost-effectiveness as a power generation option. It is anticipated that solar PV generation will increase by 25% between 2022 and 2030 in alignment with net-zero emissions goals by 2050 [

113]. The transportation sector significantly contributes to CO2 emissions [

2] and EVs are a viable solution that has been actively promoted. Consequently, an increase in Electric Car sales by 35% is expected, reaching 14 million in 2023 compared to the previous year (2022) when it was at 10 million globally [

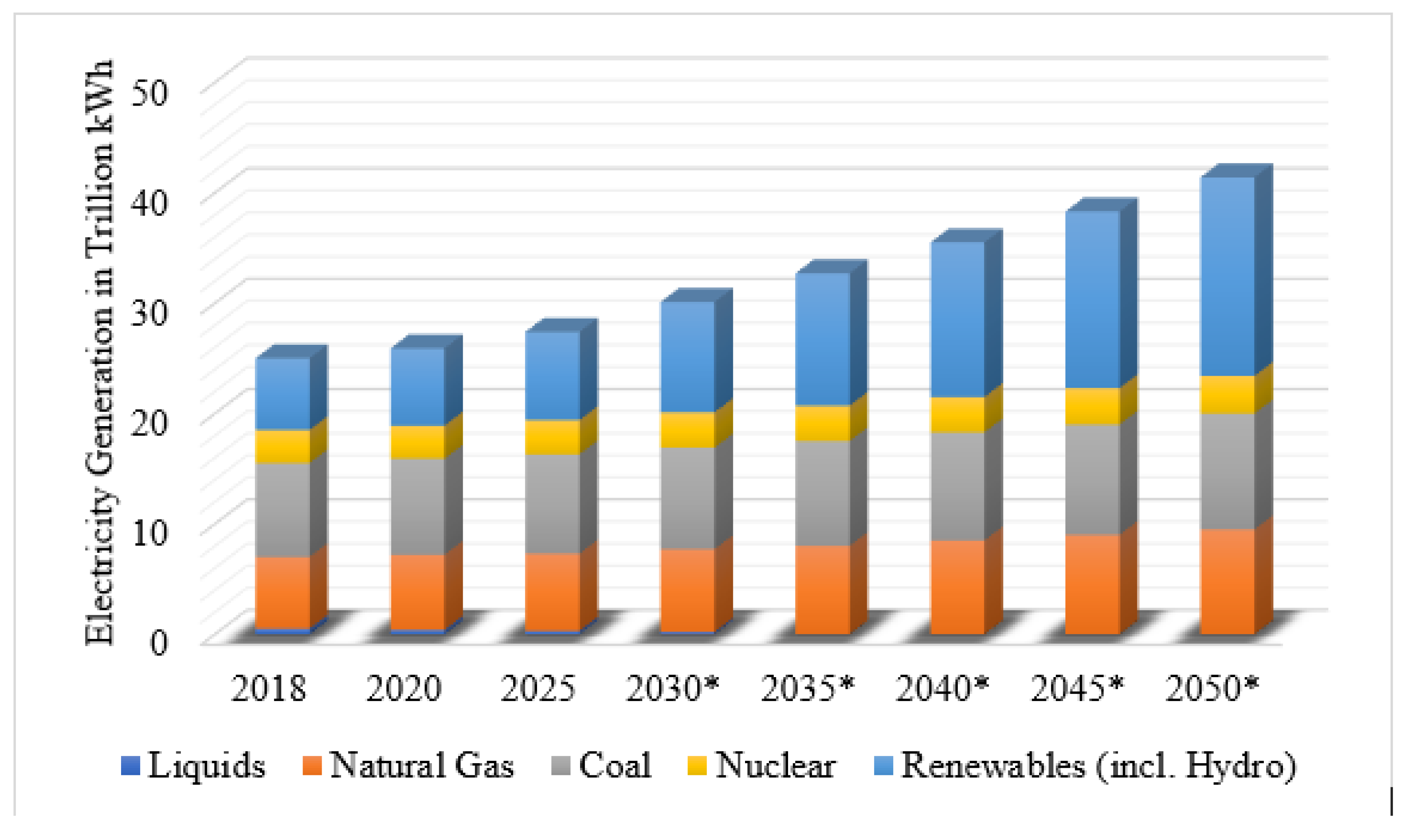

2]. Worldwide electricity production is anticipated to rise by about 50% in the coming thirty years, achieving an estimated 42,000 terawatt-hours by 2050 [

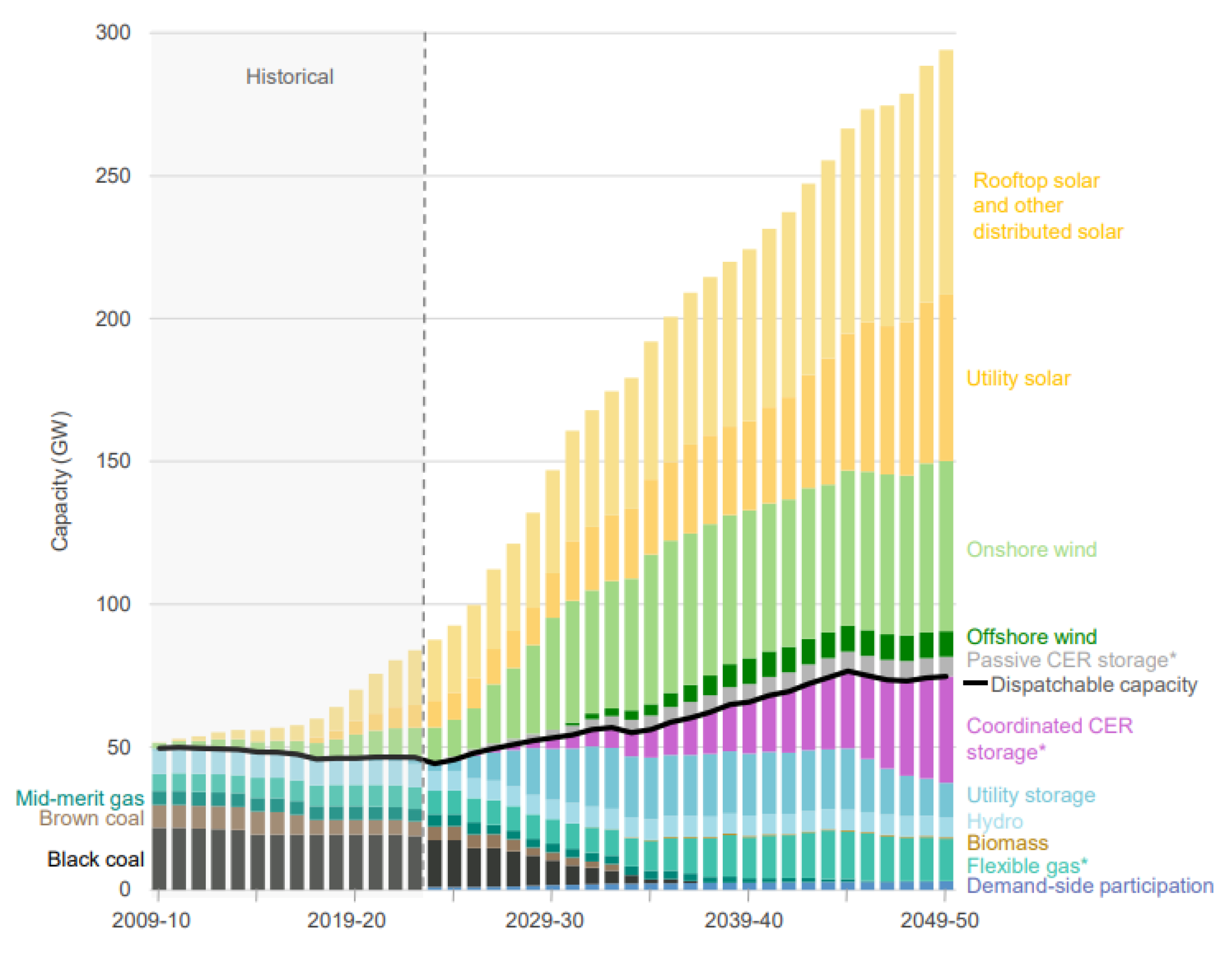

163]. At that point, renewable energy sources are projected to form the primary component of the global electricity composition, making up close to 50% of the overall generation, as depicted in

Figure 1.

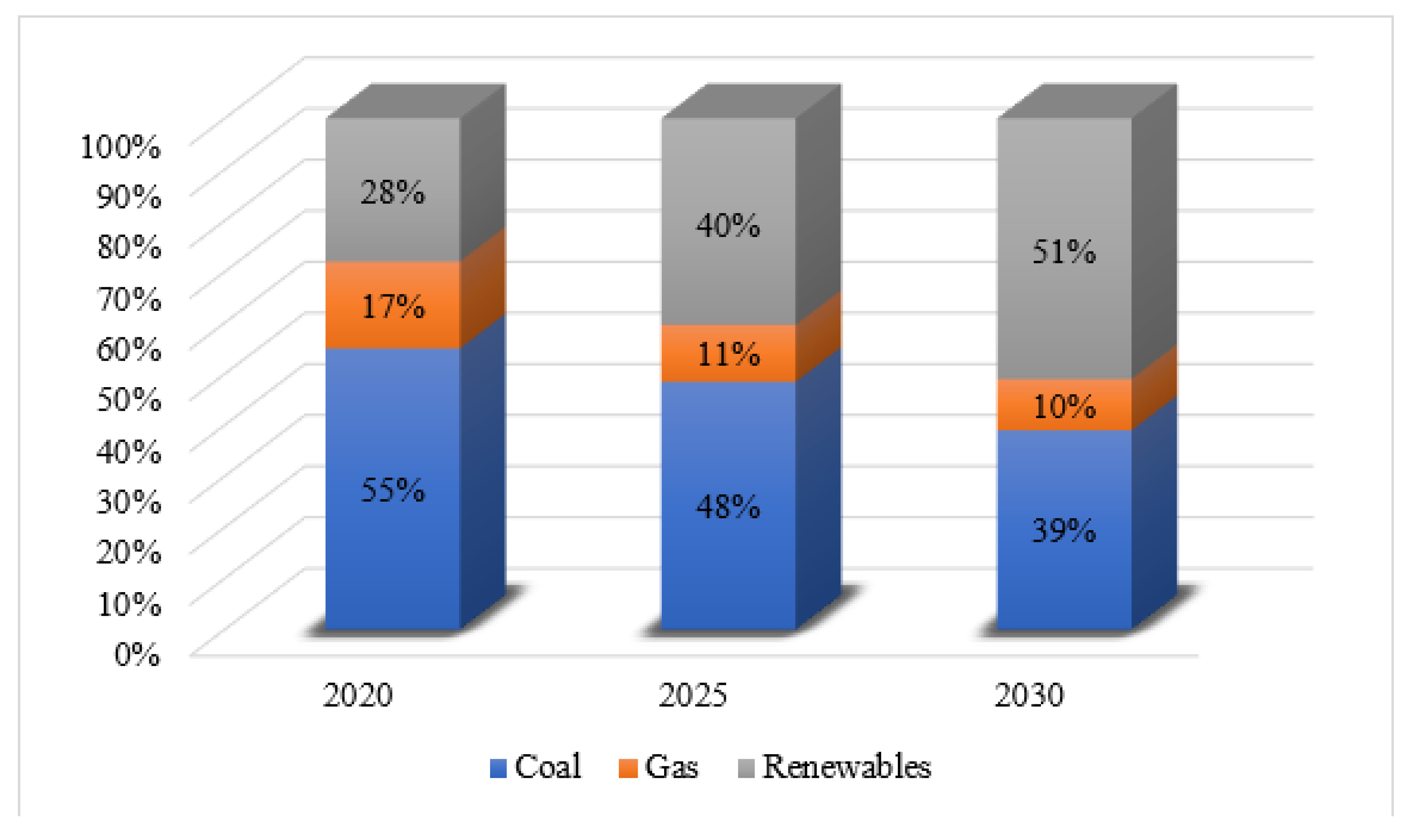

Along with the rest of the world, Australia is increasingly adopting renewable energy sources to meet its energy demands, with a growing emphasis on distributed energy resources (DERs), as shown in

Figure 2. The trends suggest a significant increase in the incorporation of DERs into regional distribution grids. The uptake of solar PV systems among electricity users connected to LV distribution networks is on the rise, driven by the multitude of benefits associated with this technology [

2].

Despite being environmentally friendly, the large-scale integration of PV presents operational, management, and planning challenges in LV Distribution Networks [

2]. The significant increase in PV and EV integration poses a new challenge for local grids that were not initially designed to handle intermittent generation from PV or uncontrolled loads like EV charging [

2]. The intermittent nature of solar PV and wind can impact the power and frequency of the system, resulting in power quality issues, especially in the case of microgrids. Therefore, energy systems like BESSs could be a reasonable solution to address the intermittency of these energy resources. The worldwide implementation of DERs like Solar PVs and EVs is in accordance with political, social, economic, technical, and environmental goals related to climate management [

7]. This surge in DERs integration has led to inevitable transformations in traditional local grids, presenting new challenges for Distribution Network Service Providers (DNSPs) in accommodating customers at a higher capacity[

8]. The increased integration of DERs can have adverse effects on network operations, including voltage fluctuations, thermal overloading, and protection-related issues [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. In conventional practice, local distribution grids are designed for one-way power transmission. However, the incorporation of DERs specially in LV/MV networks introduces bidirectional power flow, raising Power Quality issues within the network[

15]. There has been a conflict of interest between investors in DERs and DNSPs due to the unplanned and rapid integration of these energy resources, leading to operational and technical challenges for DNSPs. Consequently, the concept of HC has gained significance as a crucial step towards fostering a sustainable environment. In the current context, there is a pressing requirement to optimize the integration of DERs based on their HC within the Distribution Network. The significant incorporation of these DERs poses challenges attributed to their bidirectional power flow, contrasting with the conventional unidirectional power flow design of grids and networks from generation sources to end consumers. Within this framework, the precise evaluation of the HC of DERs in a distribution network is regarded as a fundamental and essential initial phase from a strategic planning standpoint. The review provides state-of-the-art information on various methods, tools and approaches utilized for quantifying DERs HC. Additionally, it addresses the factors influencing DERs HC in a distribution network. Furthermore, the work discusses different methods and techniques employed to ensure these factors remain within permissible limits. An in-depth analysis of various studies on how these methods and techniques enhance DERs HC in electric distribution networks is presented. Moreover, this work primarily focuses on a new concept called Dynamic Operating Envelope, its different aspects, challenges concerning current studies in the Australian context for the large-scale integration of these DERs, and potential challenges in implementing these operating envelopes. Many papers have been published on the Integration of DERs in distribution networks regarding HC assessment, enhancement, and the impact of these enhancement techniques on HC levels. However, none have conducted a comprehensive review specifically focusing on the concept of DOEs in the Australian context and related projects. The organization of my review is as follows:

Section 2 presents the concept of HC and reviews various methods, tools (including their advantages and limitations), and AI techniques used to quantify the HC of DERs.

Section 3 discusses the factors influencing DERs Hosting Capacity.

Section 4 examines various techniques for enhancing DERs Hosting Capacity.

Section 5 explores the role of DOEs in integrating distributed energy resources into low- and medium-voltage distribution networks within the Australian context. It highlights the importance of DOEs, their use cases, a general framework, related Australian projects, implementation strategies, the calculation of operating envelopes, their role in the energy market, and the challenges associated with their deployment.

Finally, conclusions and future directions are presented in

Section 6 and 7, respectively.

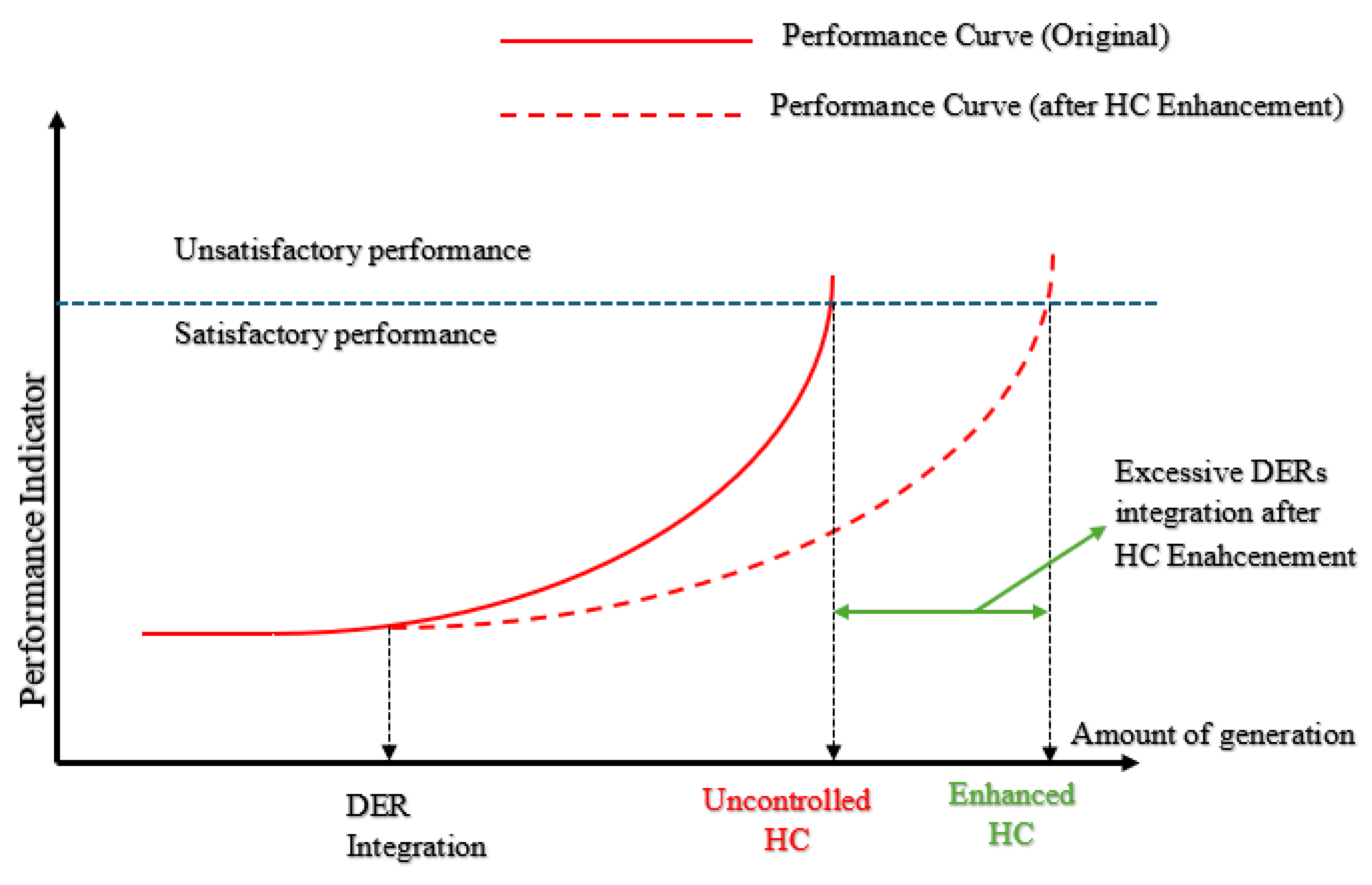

2. Hosting Capacity

Hosting Capacity (HC) is the measure of a distribution network’s ability to incorporate DERs without exceeding its operational thresholds, such as voltage, overloading, power quality, and protection. HC has become increasingly significant as a foundation for integrating DERs such as PVs, BESSs and EVs. The concept of HC can be easily grasped with the aid of

Figure 3, illustrating how DERs can be extensively integrated into the same distribution network by improving HC while adhering to the network’s operational limits.

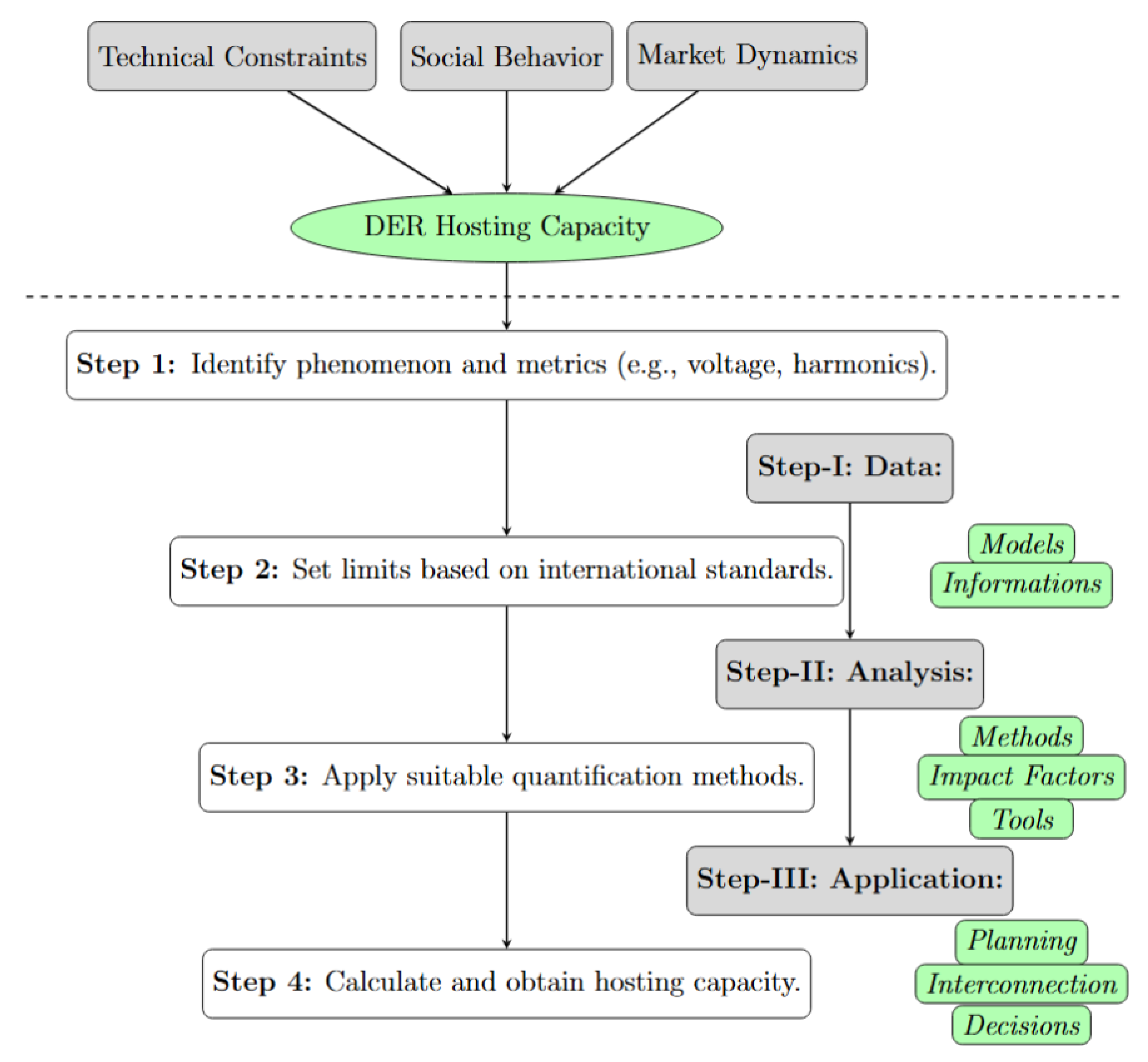

The Hosting Capacity of Distributed Energy Resources is subject to multiple factors, such as the DER type, connection configuration (single or three-phase), weather patterns, network structure and topology, and the nature of the load. Studies such as [

16,

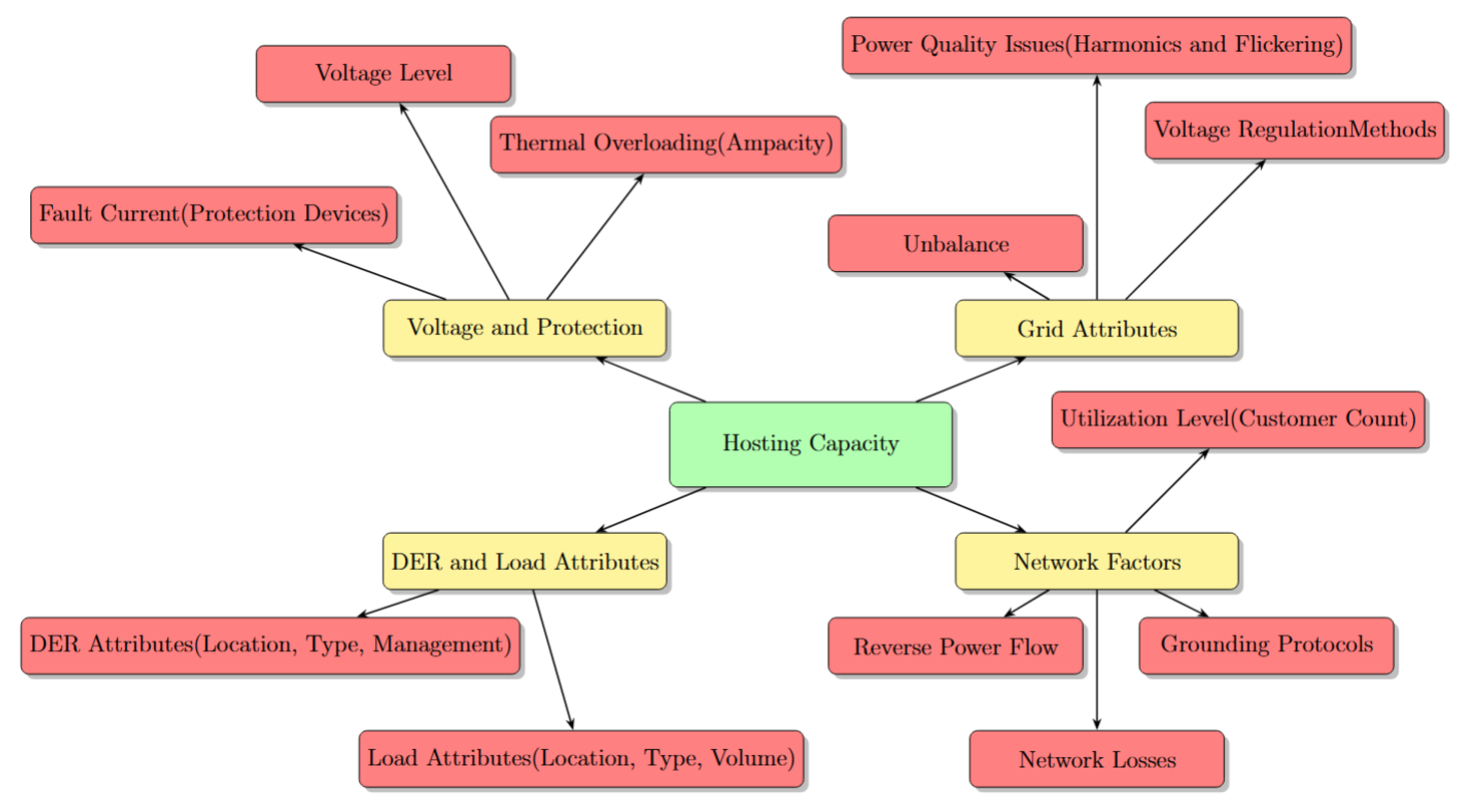

17] have highlighted that the location of DERs plays a crucial role in determining HC, among other factors. Initially, precise and prompt quantification of HC is vital at different points within a distribution network. Subsequently, understanding how HC can be improved through various technical methods is essential. DNSPs face a significant challenge in identifying and implementing innovative approaches to enhance the HC of DERs, such as Solar PV and EVs, in a Distribution Network. The primary consideration in HC Assessment is its use case, which is determined by the study’s purpose, analysis method, scalability level, and level of detail. Hosting capacity can be affected by several general factors, as shown in

Figure 4.

2.1. Methods for Quantification of DERs Hosting Capacity

Typically, the procedures delineated in

Figure 4 are adhered to for ascertaining HC.

This methodology includes employing a minimum of one Performance Index (PI) (like voltage fluctuations, thermal overloads, imbalance, harmonic distortions, inefficiencies, or protection concerns) with predefined thresholds aligned with recognized norms[

7]. A suitable HC quantification method is then selected to assess the HC concerning that specific DER. The selection of the methodology type is contingent upon the study’s objectives [

8]. The total process of Hosting Capacity Assessment can be divided into three steps. Initially, we require data in the form of models, or any relevant information related to networks. Subsequently, based on the available data, we analyze the appropriate methods, impact factors as per requirements, and the tools needed for calculating Hosting Capacity. Lastly, the Hosting Capacity Assessment can be utilized for planning, interconnection, and decision-making, as illustrated in

Figure 4.

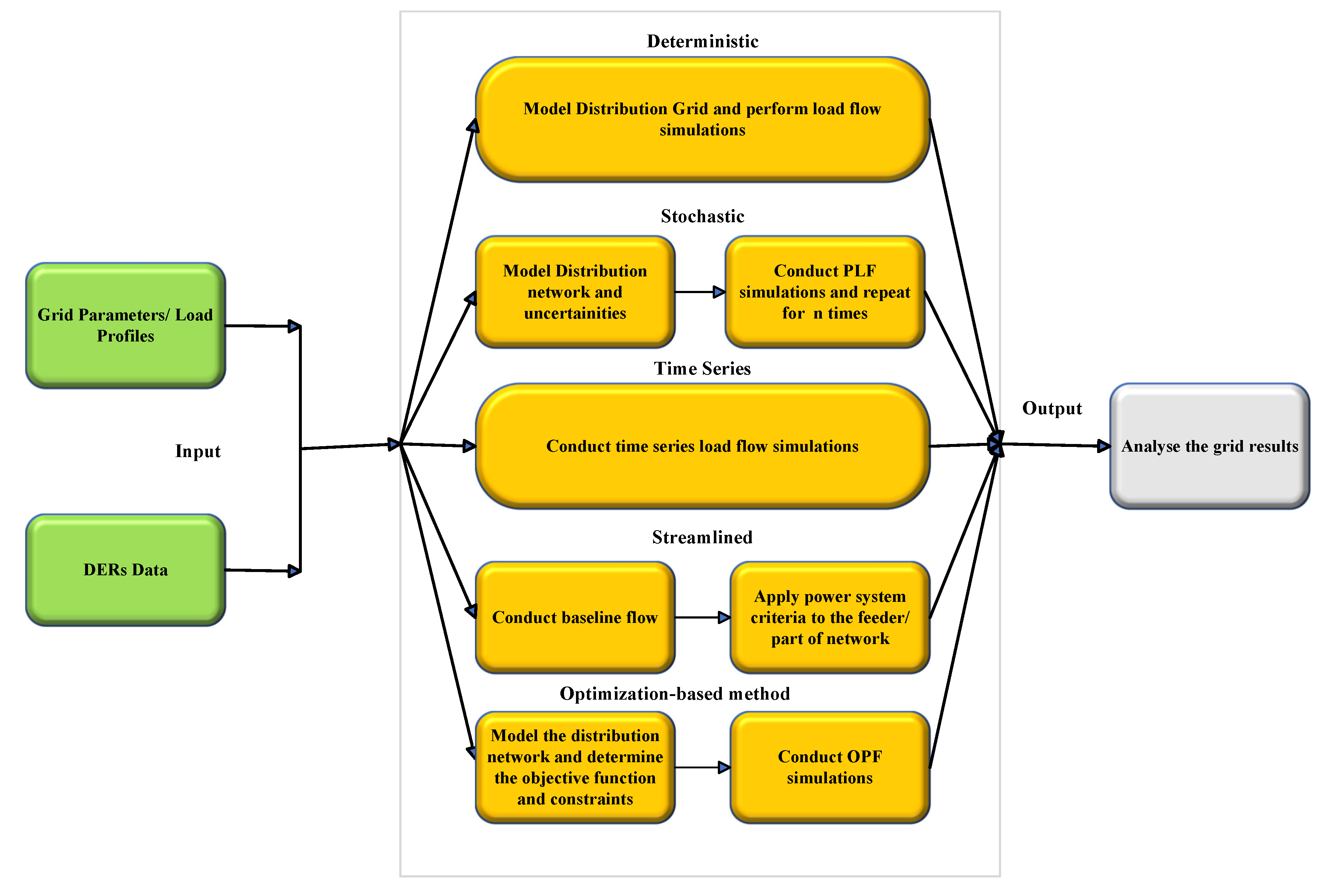

2.1.1. Deterministic

The deterministic method is a fundamental approach that commences with data collection, followed by the steps outlined in

Figure 5. Unlike probabilistic methods, deterministic approaches do not factor in uncertainties such as PV output, load consumption, PV capacity and location, relying instead on predefined or assumed values derived from grid, PV, and customer models [

18,

19]. This method operates based on worst-case scenarios to evaluate uncertain parameters [

8]. The deterministic method is straightforward and efficient, involving minimal calculations. It relies on limited input data and is beneficial for rapid HC assessments. Typically suitable for a single large installation, this method overlooks uncertainties and tends to underestimate Hosting Capacity due to its focus on worst-case scenarios [

20]. Therefore, deterministic methods do not incorporate any elements of randomness or statistical techniques in their processes. Some examples of studies of deterministic methods are given in

Table 1.

2.1.2. Stochastic

The stochastic method considers uncertainties categorized as aleatory and epistemic. Aleatory uncertainties pertain to the intermittency in PV production and load, while epistemic uncertainties relate to the lack of precise data, such as the capacity and location of PV in the grid, forming a probabilistic model of the distribution system [

18]. By employing probabilistic load flow (PLF) and random scenarios for PV placement and capacity as inputs in the network using probability distribution functions (PDFs) developed from historical data, this method incorporates the likelihood of occurrence of unknown variables [

19]. Subsequently, network load flow simulation is conducted, as illustrated in

Figure 5. Some examples of studies of Stochastic methods are given in

Table 2.

This method takes into account the uncertainties mentioned above and can simulate real grid scenarios. By utilizing Probability Distribution Functions (PDFs), it can offer a more realistic depiction of grid operations. However, in this method, the temporal relationship among variables may be compromised, leading to an increase in ambiguity due to an excessive number of scenarios. Additionally, the need for extensive data measurements results in a heavy computational burden. Consequently, analyzing and interpreting Hosting Capacity results becomes challenging.

2.1.3. Time Series

The time series approach to Hosting Capacity Assessment looks at how well a power distribution grid can handle different DERs, by studying detailed data collected over a long period. The exploration of integrating DERs such as BESS, smart inverters, and EVs into distribution networks requires contemporary methodologies and technologies also commonly known as Quasi-Static Time Series (QSTS) [

36]. This is a modified version of the deterministic method where real measurements of PV output and load consumption are conducted instead of using fixed values as in the deterministic approach for HC calculations [

19]. By incorporating time series data of PV generation and load, this method ensures accurate DERHC calculations [

8]. While this method enhances accuracy in HC calculations by considering the time series of load consumption and PV generation, it may not capture all potential effects of DERs on network performance, such as voltage violations or increased tap operations. Since this method considers the time series of load consumption and PV generation, so it gives accuracy in the HC calculation of the system. Despite its precision, the QSTS method is time-consuming and imposes an additional computational burden due to the requirement for high-resolution simulations [

18]. The Time series method can be briefly illustrated in

Figure 5. Some examples of studies of Time Series methods are given in

Table 3.

2.1.4. Streamlined

The Streamlined Method, pioneered by the Pacific Gas and Electric Company (PG&E), is employed for the estimation of HC in Distribution Networks. This approach utilizes a series of equations and algorithms to predict HC at different points within distribution networks. The methodology comprises two main phases: initially, conducting a baseline power flow analysis, and subsequently assessing performance indicators including voltage, thermal, and protection limits. This iterative procedure is repeated numerous times, as necessitated for California’s integration capacity analysis spanning 576 hours, to track fluctuations in load, DERs, and voltage regulation devices, in alignment with time-based HC methodologies [

8]. One key advantage of this method is its estimation of HC without considering DER profiles, enhancing computational efficiency and enabling time-based HC assessments [

42]. However, drawbacks include the necessity for DER forecasting (e.g., using smart meter data), time-series load data, and accuracy challenges in complex circuit scenarios [

8]. Generally, the streamlined method can be illustrated as in

Figure 5. Some examples of studies of Streamlined methods are given in

Table 4.

2.1.5. Optimization-Based Method

An optimization-based method is a structured technique that seeks to identify the optimal solution to a problem by either maximizing or minimizing a defined objective function while adhering to a set of specified constraints. This method views PV integration as an optimization challenge and applies the Optimal Power Flow technique (OPF) to maximize the installed PV capacity within grid constraints as per the study [

30]. While some studies indicate that this method can be employed with a single objective function to maximize HC [

45,

46] in other instances, it can serve multiple objectives such as enhancing HC while minimizing losses and costs simultaneously [

47,

48]. The optimization-based approach is typically depicted as shown in

Figure 5. Some examples of studies of Optimization-based methods are given in

Table 5.

2.1.6. Other Approaches

- i.

Iterative method. An iterative method is a mathematical procedure used to generate a sequence of improving approximate solutions for a class of problems. This method utilizes software packages for distribution network analysis to estimate HC by assessing individual DER locations incrementally until limits are exceeded. Commercial software such as Cyme and Synergy also employ this approach. The advantages of this method include multi-feeder analysis and the utilization of accessible tools [

8]. Time-based HC analysis necessitates load and DER forecasts.

- ii.

Hybrid Drive method. DRIVE is the abbreviation for Distribution Resource Integration and Value Estimation. The Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI) recently developed this method to address the primary drawback of previous methods, which was the computational burden, and to provide accurate estimates of hosting capacity. This method can be described as a combination of features from stochastic, streamlined, and iterative methods.

2.2. AI Based Hosting Capacity Assessment Techniques

As per study [

156], author proposes the utilization of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) methodologies as a substitute for traditional electrical models in HC estimation. This approach addresses the inherent limitations of electrical models, which are often characterized by their computational intensity, high cost, and potential inaccuracies. Conversely, AI/ML models offer a compelling alternative by providing rapid and accurate estimations, thereby streamlining the HC assessment process.

Table 6 presents a compilation of AI-driven assessment techniques employed in HC evaluations, as documented in various studies.

2.3. Power Flow Analysis Tools

Power flow analysis methodologies serve as the foundational data for HC assessments, integrating both conventional and artificial intelligence methodologies. Moreover, these analytical instruments play a pivotal role in network planning, design, and operational processes [

61]. Commercially accessible power flow analysis software includes PSS/Sincal, PSCAD, DIgSILENT PowerFactory, NEPLAN, Synergy Electric, and CYME. Conversely, open-source power flow analysis tools include PandaPower, OpenDSS, PowerModelsDistribution, and OpenDSOPF. A comparative analysis of various software tools used for HC evaluation, highlighting their methods, key parameters, features, strengths, and limitations for HC assessment, as detailed in

Table 7.

3. Main Factors Affecting the DERs Hosting Capacities

Numerous factors influence the HC of a feeder or network within distribution systems. A general overview of these influences is presented in

Figure 4, which categorizes them as: (i) technical constraints, (ii) social behavior, and (iii) market dynamics. Among these, social behavior and market dynamics typically fall outside the direct control of network operators. However, technical constraints can be actively managed and mitigated. Therefore, the primary focus of this section is on the technical constraints that limit HC. Impact factors or limiting factors are crucial in Hosting Capacity studies as the grid choice and characteristics of DER devices considered significantly affect the outcome. Many studies have been conducted in this regard. Hosting Capacity may not be a single value due to different limiting factors resulting in varying HC values.

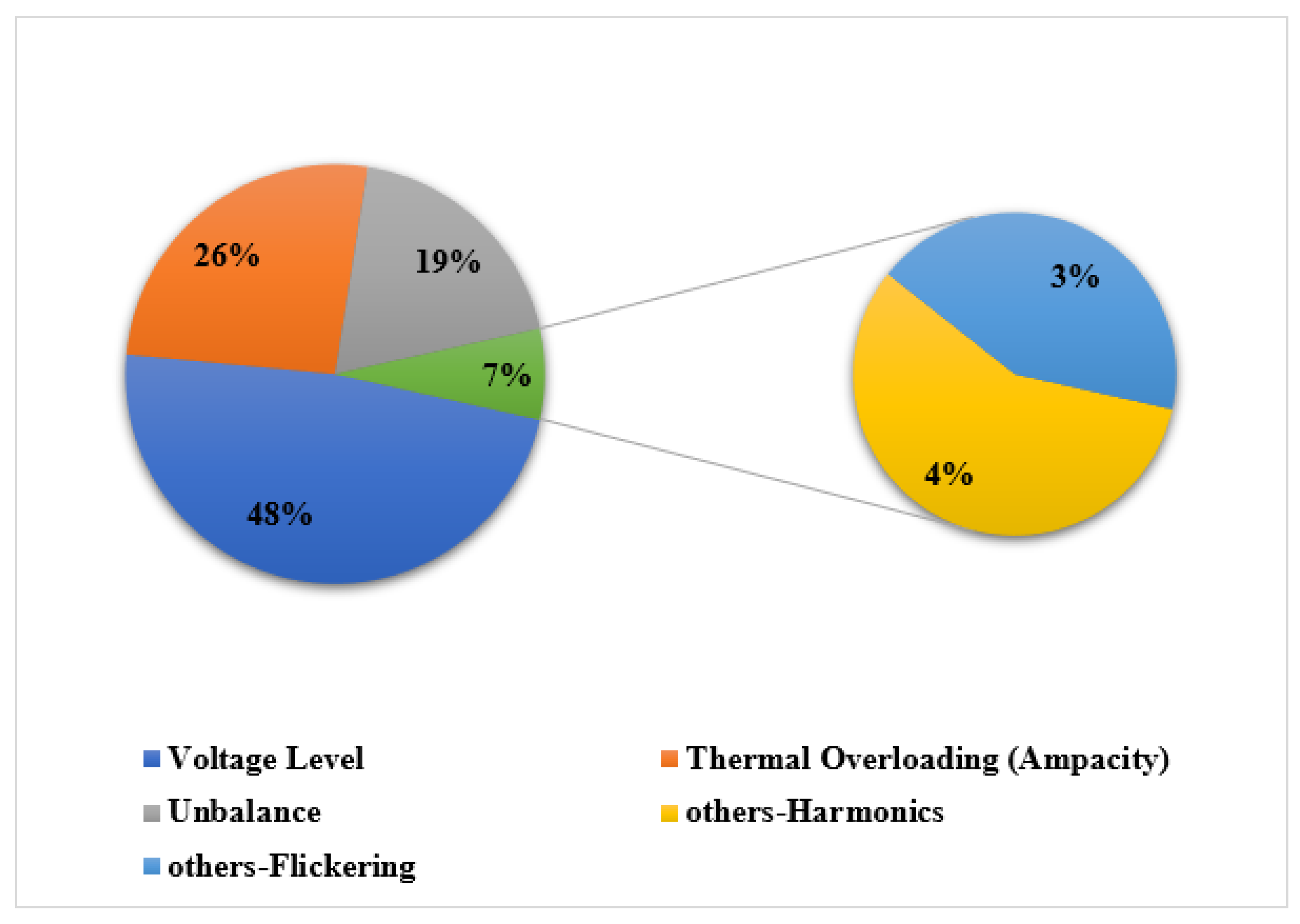

According to [

49,

72,

73,

74], voltage violations, voltage unbalance, ampacity, and power quality issues (such as harmonics and flickering) impact HC. However, in [

75,

76,

77,

78,

79], other limiting factors like fault current concerning protection devices, reverse power flow, network losses, and utilization level (based on the number of customers) were considered by the authors. The high integration of PV into the LV network primarily relies on Power Quality and the feeder’s thermal limits [

79].

The Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI) concluded that grid characteristics (including voltage control schemes), load characteristics (such as location, type, and quantity), phasing, grounding procedures, reconfiguration capabilities, and DER characteristics (including location, type/technology, and control) are the primary limiting factors [

80,

81]. In [

17] sensitivity studies were conducted to analyze various feeders regarding overall HC impacts, revealing that PVHC is highly sensitive to PV location and operating power factor. Additionally in [

11], the author demonstrated that PV distribution, load modeling, and network topology also influence HC levels in a distribution network. As per the study [

2] voltage violation is identified as one of the primary limiting factors compared to others, as indicated by previous literature surveys shown in

Figure 7. Different limiting factors considered in various studies are presented in Table 1,2,3,4&5 respectively. Based on the aforementioned studies, it can be concluded that the following factors are primarily significant as limiting elements for hosting capacity levels in a distribution network:

Figure 6.

Different limiting factors (technical) considered as per various studies.

Figure 6.

Different limiting factors (technical) considered as per various studies.

Figure 7.

Limiting Factors (%) in literature [

2].

Figure 7.

Limiting Factors (%) in literature [

2].

Additionally, previous research studies have identified several factors that influence hosting capacity limitations in distribution networks. Many factors affect the DERS HC in networks, as demonstrated by various studies and illustrated in

Figure 6. These include fault current constraints related to protection devices, reverse power flow, network losses, and utilization levels based on customer count. Furthermore, grid attributes (such as voltage regulation methods), load characteristics (including location, type, and volume), grounding protocols, and DER attributes (encompassing location, technology, and management strategies) also play a significant role in determining hosting capacity levels. The selection of impact factors to apply depends on the specific objectives of the analysis and the availability of relevant data. Different factors may be prioritized based on the intended application and the context of the distribution network.

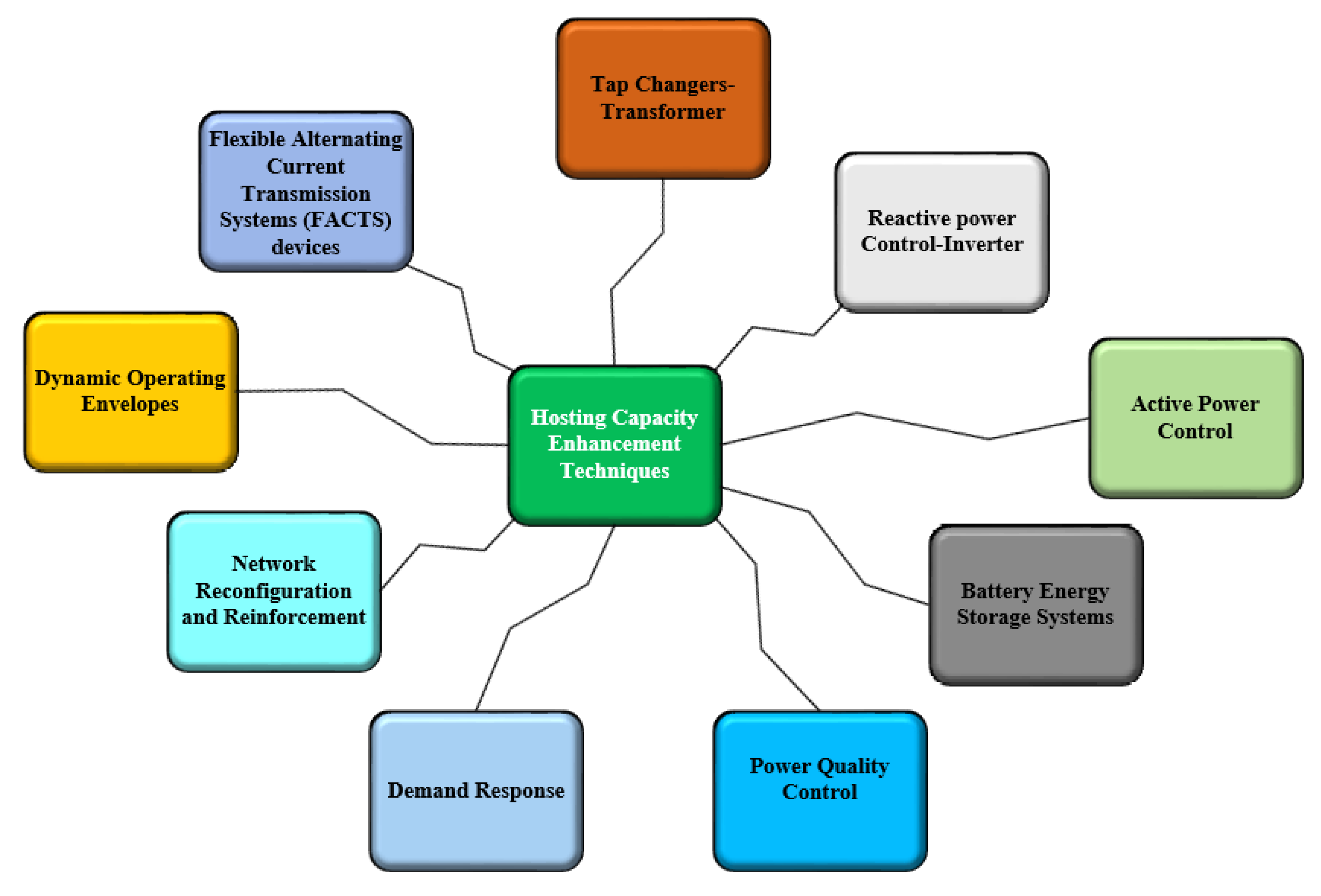

4. Different Techniques Used for HC Enhancement of DERs

Various techniques have been used to enhance the Hosting Capacities (HCs) of Distributed Energy Resources (DERs) in distribution networks, and some of them are outlined below.

The author of the study [

72] demonstrated the role of On-Load Tap Changer (OLTC) in enhancing Hosting Capacity (HC) through voltage regulation in balanced three-phase systems concerning single phase. The use of reactive power control (Inverter) is particularly beneficial when the X/R ratio is high, such as in high voltage grids compared to low voltage grids [

2]. In [

84], authors recommended Reactive Power Control (RPC) over Active Power Curtailment (APC) for voltage compensation in a distribution network. The authors of [

85,

86] considered the use of APC to address network stability issues due to high Photovoltaic (PV) integration into the distribution network. In reference [

87] discussed how advanced OLTC settings, along with Secondary VAr Controllers and smart inverters, doubled the HC of Keolu Substation from 77% to 154% of peak load. In [

89] the author demonstrated the efficiency of voltage regulation through OLTC compared to PV Var absorption in a real rural Medium Voltage/Low Voltage distribution network. According to [

87], optimal power flow can enhance voltage stability in a distribution network, while [

89] highlighted that improper Demand Response can lead to increased losses and voltage unbalance. Author of [

91] proved how Network Reconfiguration can enhance HC in a distribution network. As per[

92], Active Power Curtailment (APC) plays a crucial role in HC improvement, with APC up to 30% and 50% of PV HC being more cost-effective than Reactive Power Control (RPC) or storage strategies. In [

93], the author discussed that installation of Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS) with forecasting doubled the HC from 19.65% to 39.29%, and a centralized BESS control combined with forecast algorithms increased PV HC by 26Power Quality issues like Unbalance, Harmonics, and Flickering often arise from rooftop solar PV, inverters, non-linear loads, and intermittent DERs like solar in distribution networks. Decreasing harmonic voltage can lead to a 12% improvement in HC according to author of [

94]. The proposed Optimization Strategy for PV inverters by the author of [

95] can address Power Quality issues like Unbalance and voltage fluctuations effectively. PV inverters can regulate voltage locally through Active Power (P) and Reactive Power (Q), known as Volt/Var and/or Volt/Watt control. Smart inverters typically operate based on predefined setpoints designed for worst-case scenarios rather than local network conditions, leading to underutilization of DERs. A Dynamic Control Strategy for inverters that responds to actual network conditions is essential [

8]. Sophisticated Flexible AC Transmission System (FACTS) apparatus such as the Unified Power Flow Controller (UPFC) or Unified Power Quality Conditioner (UPQC) possess the capability to regulate both active and reactive power flows within a feeder [

96]. The effectiveness of FACTS Devices like the Dynamic Voltage Restorer (DVR), Distributed Static Compensator (D-STATCOM), and UPFC for voltage regulation, loss reduction, and enhancement of power quality in distribution networks has been examined in references [

97,

98,

99]. In [

100], author explores dynamic limits for DERs along with feasibility and control schemes. In reference [

101], Operating Envelopes are shown to be beneficial for integrating a maximum number of DERs in the same network. In reference [

102], an investigation was conducted to evaluate and improve the uncertain Hosting Capacity of Renewable Energy, with or without voltage control devices, in distribution grids. This study employed the Manta Foraging Optimization (MRFO) algorithm in conjunction with OLTC, Static Var Compensator (SVC), and Power Factor control of DERs. This study considered solar PV and wind turbines as renewables while accounting for uncertainty from all sources including load. The bi-stage approach resulted in a significant increase in HC levels with 33-bus and 118-bus systems showing improvements of 77.8% and 74.5%, respectively.

Figure 8 and

Table 8 illustrate several techniques identified in various studies for enhancing hosting capacity (HC) levels of DERs.

5. The Role of Dynamic Operating Envelopes in the integration of DERs in an LV/MV Distribution Network in Australian Context

Due to the various advantages of DERs over traditional resources, they are gaining global attention. Australia boasts the highest rate of solar adoption globally. Based on data from the Clean Energy Regulator [

115], as of December 31, 2020, the country had more than 2.68 million rooftop solar power systems installed. Roughly one in every four households in Australia has solar panels installed on their rooftops. Despite the numerous benefits such as energy reliability and security from integrating DERs (like Solar PV, BESS, EVs) in the Low Voltage (LV)/Medium Voltage (MV) Distribution Network, it also exposes the network to the challenge of two-way power flow, leading to breaches in operational and physical limits of Distribution Networks. To address this issue, the concept of Dynamic Operating Envelopes (DOE) has been introduced to mitigate violations of operational limits. According to the AEMO 2020 Integrated System Plan (ISP), DERs might supply between 13% to 22% of the total underlying annual National Electricity Market (NEM) energy consumption by 2050. By 2040, they are predicted to double or even quadruple in size. The rapid adoption of distributed solar PV is expected to persist until 2050 and potentially beyond, driving the growth of DERs in Australia. According to references [

116,

117], there exist numerous advantages associated with the utilization of Operating Envelopes in the context of incorporating DERs into distribution networks. Operating Envelopes present a flexible resolution to the myriad challenges encountered during the assimilation of DERs into Distribution Networks. Their implementation does not require complex local control and optimization systems, rendering them readily adaptable across a variety of DER assets.

Moreover, Operating Envelopes can be incrementally implemented across different segments of distribution networks as the need arises. Moreover, the implementation of Operating Envelopes holds several potential benefits:

- i.

Enhanced solar PV/Battery export.

- ii.

Improved market efficiency: Operating Envelopes may result in increased embedded energy in the market, potentially leading to reduced wholesale energy prices for all customers.

- iii.

Enhanced interoperability: This can facilitate efficient balancing of generation and demand, potentially reducing the need for costly infrastructure investments. Participation in real-time energy markets can be advantageous for all customer categories.

- iv.

Enhanced network efficiency.

As per [

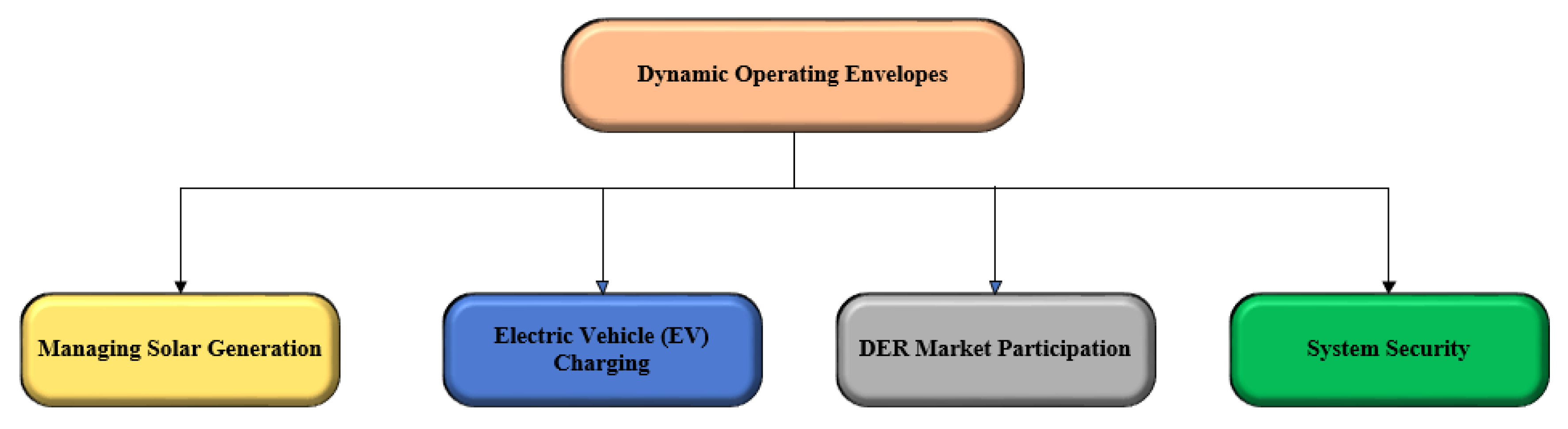

100], use cases for DOEs include managing Solar Generation in terms of export, DERs market participation for import and export facilitation, EVs charging in terms of import, and power system security as gievn in the

Figure 9. The advantages of integrating DERs into distribution networks align with the changing generation mix in the National Electricity Market (NEM) would resemble this as we approach 2050, as depicted in

Figure 10. An Operating Envelope (OE) is the specification of DERs/connection points that can be integrated into a Distribution network without surpassing the operational/physical limits. Furthermore, operating envelopes define the technical constraints on power import and export for customers.

5.1. Dynamic Operating Envelopes

A DOE refers to the systematic allocation of available HC to a DER/DERs within a distribution network for each time interval. A DOE sets upper and lower limits on the power that can be imported or exported within a specific timeframe for particular DER assets or a connection point. Import and export constraints are adjusted by the DOE according to the overall capacity of the local network or power system over time and space.

Different distribution companies in Australia are implementing region-wide fixed active power export levels [

119] for DER owners to manage voltage and thermal constraints, disregarding phase. This approach discourages DER owners from utilizing their DERs due to less profitable investments.

The intermittent nature of DERs leads to continuous variations and imbalances between power generation and consumption in distribution networks, limiting the network’s full utilization. Different studies on the implementation of DOEs have demonstrated the potential and benefits of DOEs compared to the Fixed region-wide approach [

120,

121].

Different techniques for enhancing HC are being utilized and integrated into the DOEs implementation plan to facilitate the integration of DERs at maximum capacity. A General framework providing an Overview of Dynamic Operating Envelopes in

Figure 11.

5.2. Australian Projects Related to Dynamic Operating Envelopes

Details of some of the Australian Projects on Dynamic Operating Envelopes are given in

Table 9.

5.3. Implementation of DOE

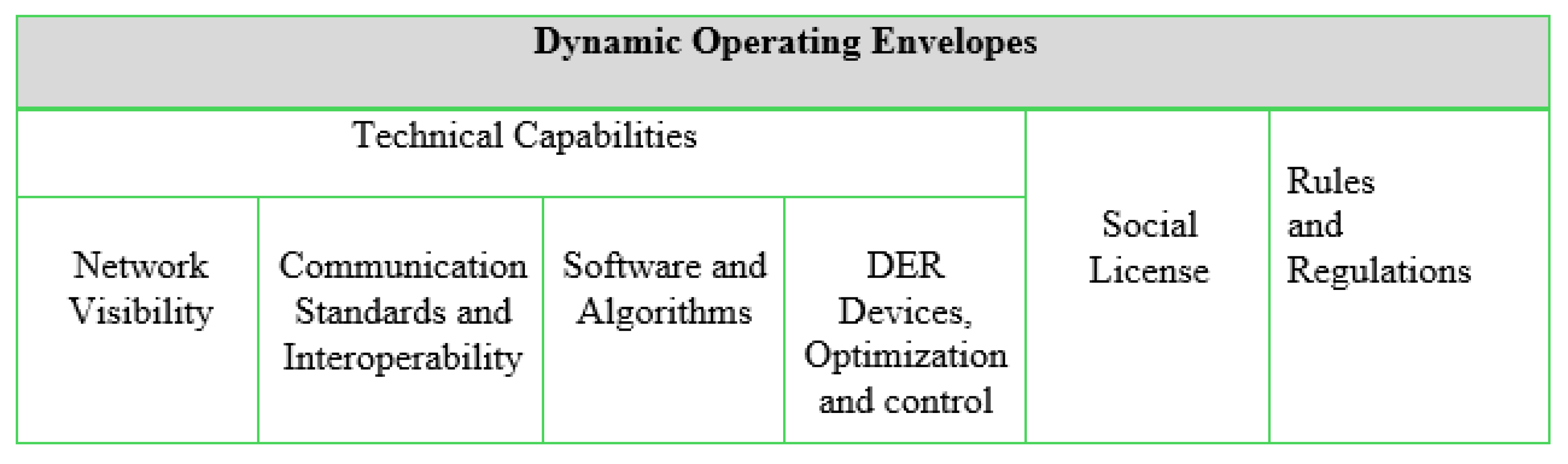

As per the study in [

101], the implementation of Dynamic Operating Envelopes (DOE) in the evolve project is founded on three major pillars: technical capabilities, social license, and rules & regulations, as illustrated in

Figure 12.

Technical Capabilities are further subdivided into four sub-categories: network visibility, communication standards and interoperability, software and algorithms, and DER devices optimization & control. As per research conducted in [

130] has provided insights into the present status of Distributed Energy Resources (DOEs) and the strategies adopted by Distribution Network Service Providers (DNSPs) to support their integration. The examination underscored the emergence of DOEs as a notable aspect of the electricity landscape, with a majority of DNSPs currently engaged in experimental or preparatory phases for DOE provision. The outcomes suggest an escalating inclination towards furnishing DOEs to consumers within the forthcoming five-year period, indicative of a deliberate transition towards dynamic and adaptable grid management approaches. In the context of Dynamic Operating Envelopes (DOEs), customers can be categorized into two groups:

- i.

Active Customers utilizing the DOE facility (Prosumers).

- ii.

Fixed Customers operating within fixed limits (may have DERs).

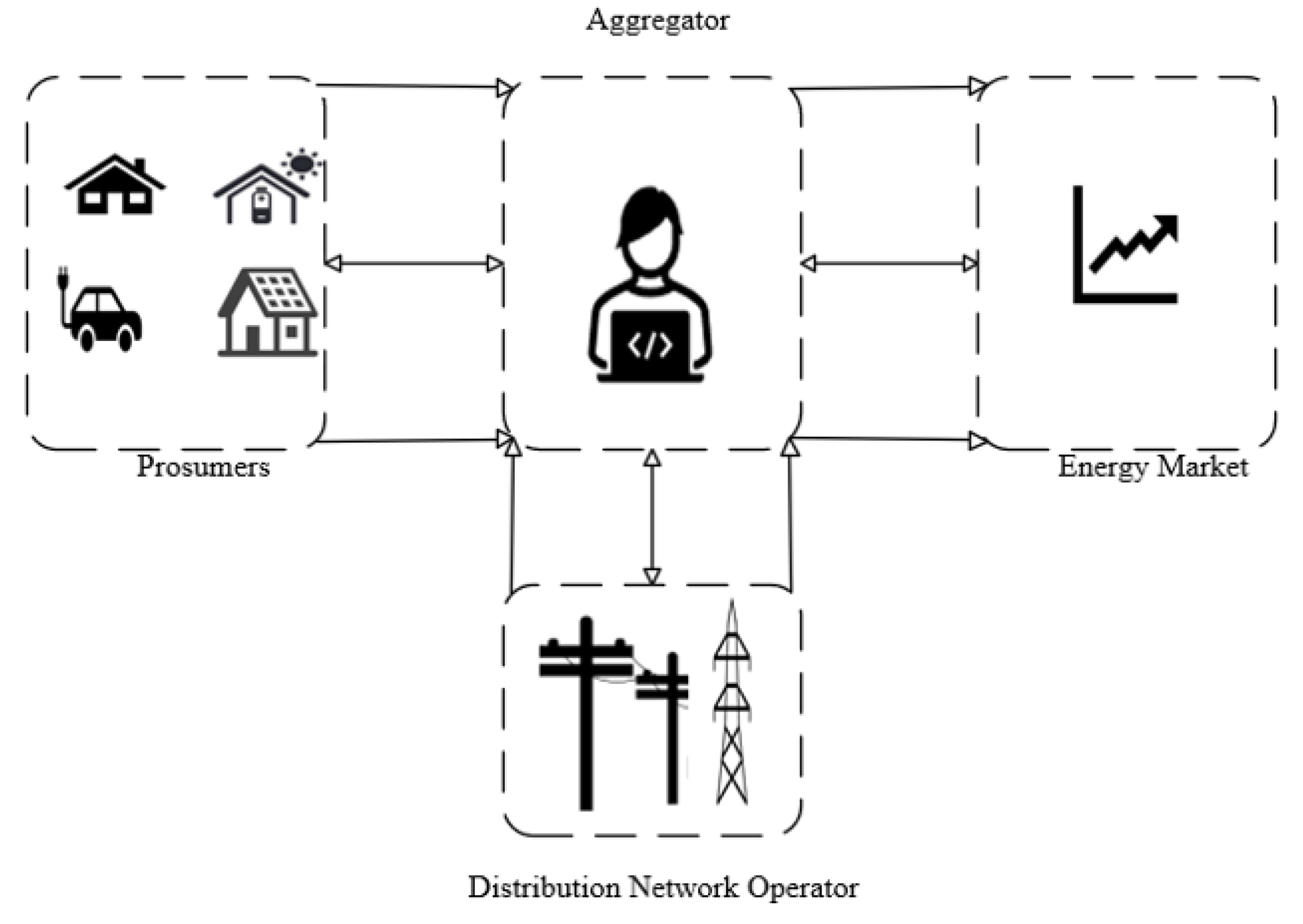

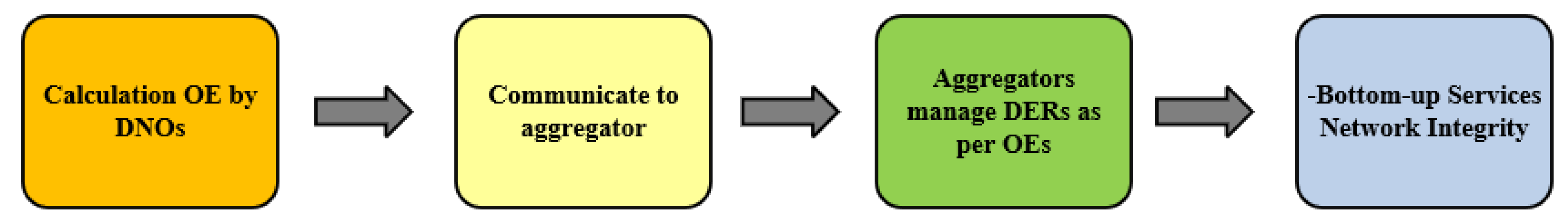

Many studies have explored different approaches for implementing Dynamic Operating Envelopes (DOEs). Some studies suggest direct control of Distributed Energy Resources (DERs) by Distribution Network Operators (DNOs) [

131,

132] which could potentially infringe on the privacy and priorities of active DER owners (prosumers). Other researchers have proposed indirect control of DERs by DNOs [

120,

121] where prosumers use their energy management systems to manage their DERs, while DNOs oversee export levels and communicate with prosumers accordingly. Aggregators may also play a role in facilitating interactions between prosumers and DNOs [

133]. Aggregators are responsible for managing DERs based on the Operating Envelopes (OEs) communicated by DNOs and sharing necessary DER data with DNOs to update OEs in line with network constraints such as voltage and thermal considerations. This approach aligns with regulatory frameworks in the electricity sector by clearly defining the roles of distribution companies and aggregators. The responsibility of aggregators extends to making network-secure bidding decisions in real-time energy and reserve markets [

133]. A Generalized Approach for DOE-Based DER Management, as indicated by various studies, is outlined in

Figure 13.

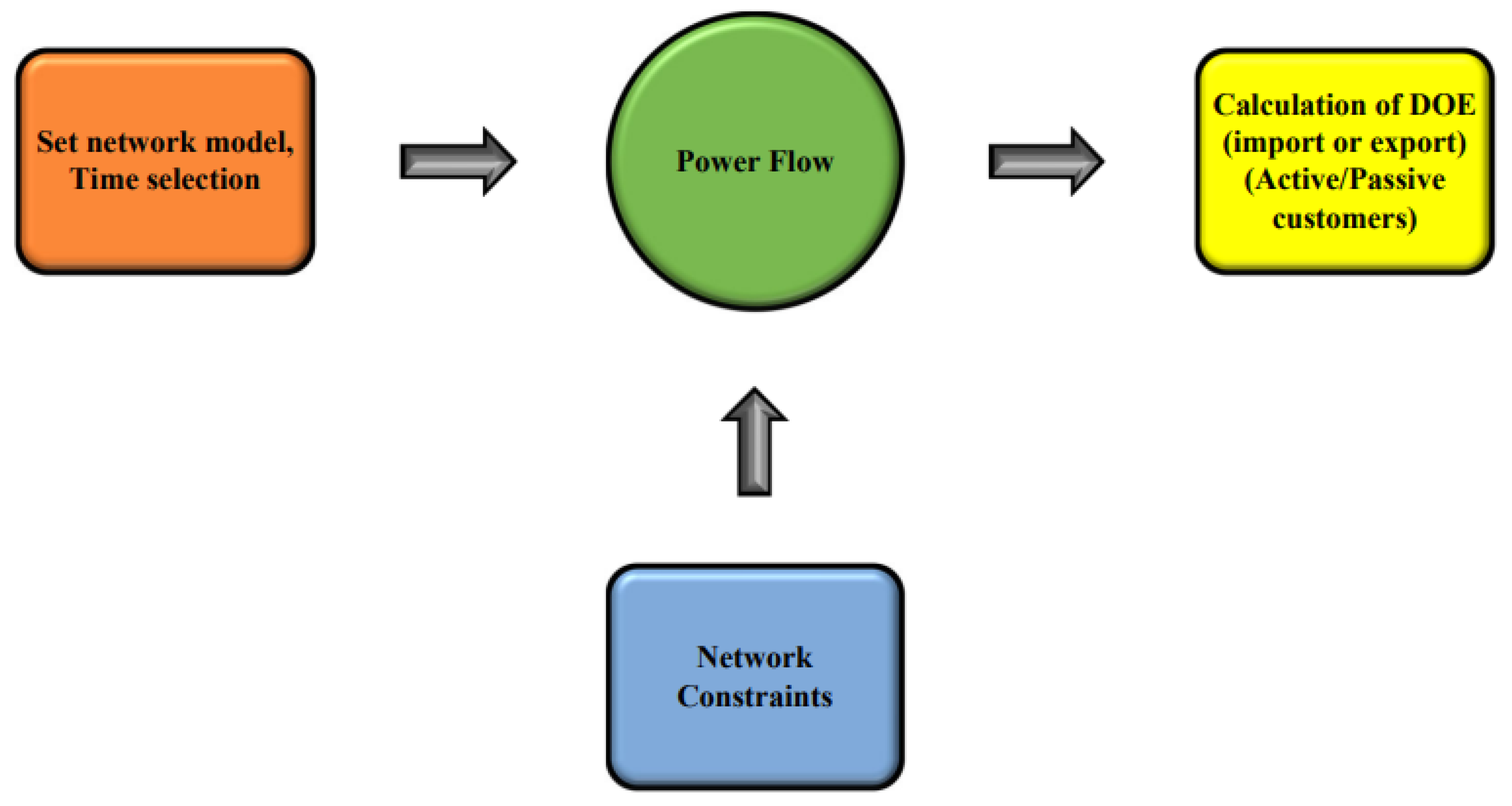

5.4. Calculation of OEs

Operating Envelopes can be calculated by Distribution Network Operators through several steps. Initially, the Hosting Capacity of the distribution network is determined, followed by the allocation of available Hosting Capacity to individual or aggregated connection points or DERs. Subsequently, DERs and connection points are managed according to the Operating Envelope (OE), ensuring that the operational limits of the network are not exceeded. In addition, Operating Envelopes (OEs) can be calculated either in advance (offline) or in almost real-time (online) depending on the frequency of data exchange. For day-ahead calculations, load and generation forecasts are utilized [

134], while for online calculations, the Distribution Network Operator (DNO) collects data from aggregators or prosumers at regular intervals. Given the challenge of reliable load forecasting in low-voltage distribution networks, dynamic data sharing offers increased accuracy [

135]. Moreover, dynamic data exchange facilitates iterative negotiations to adjust the computed OEs [

136]. Generally, calculating a Dynamic Operating Envelope (DOE) involves mathematical modeling and analysis to establish the operational limits or boundaries within which a system, such as a power distribution grid, can operate safely and reliably. Further, Dynamic Operating Envelopes (DOEs) can be calculated using the following approaches:

- i.

Iterative approach.

- ii.

Optimization-based approach.

To calculate DOEs, a mathematical model of the system is developed, and its behaviour is simulated under various conditions to ensure it operates within safety constraints while optimizing performance. This process is dynamic and iterative, necessitating continuous monitoring and adaptation to changing conditions. A general approach to calculating DOEs is illustrated in

Figure 14.

It’s important to note that the specific calculation methods and software tools used to determine a dynamic operating envelope can vary widely based on the complexity of the system and the goals of the analysis. Additionally, industry standards and guidelines may influence the methodology and criteria used in DOE calculations, particularly in critical infrastructure systems like power grids. In [

120], the author has focused solely on Active Power Operating Envelopes (OEs) as they can enhance network integrity by managing voltage and line thermal constraints. On the other hand, in [

121], the author has identified two types of OEs for communication between Distribution Network Operators (DNOs) and Prosumers: I. Active Power OEs, and II. Reactive Power OEs. It was observed that utilizing both Active Power and Reactive Power OEs together can lead to increased active power generation, especially in scenarios with a low R/X ratio. Off-load taps, Volt-Watt, and Volt-Var functions have also been employed in the implementation of DOEs in a case study [

137].

5.5. Prosumers Participation and Market Integration of Distributed Energy Resources

The success of the Distributed Energy Resources (DER) concept primarily hinges on the engagement of everyday energy consumers. To attract energy users to this concept, the key lies in introducing new electricity tariffs and incentives. With the increasing adoption of Rooftop solar systems (PV) paired with battery energy storage systems (BESS), there is a pressing need to rethink how distribution systems operate and interact with electricity markets. Aggregators play a crucial role in converting DER flexibility into valuable electrical market services, such as frequency reserve services [

138]. Distributed Network Operators (DNOs) have enabled prosumers to participate in real-time energy markets through aggregators, allowing for bidding and trading. However, without proper coordination between DER actions and DNOs, there is a risk of voltage fluctuations and congestion issues in medium-voltage to low-voltage distribution networks [

136]. Various studies have explored ways for prosumers to benefit financially from bidding while ensuring network security. Furthermore, Dynamic Operating Envelopes (DOEs) can facilitate peer-to-peer trading among prosumers, focusing on profit generation [

139]. As per [

120], It is essential to address challenges such as prosumer response to price signal spikes, which could lead to constraint violations if not managed effectively. Innovative mechanisms, as proposed in studies [

140], offer solutions for energy sharing within communities by considering agents’ strategic decision-making processes. As per an other study [

160], Peer-to-peer (P2P) trading offers significant advantages in energy markets by enhancing financial returns for prosumers, as they can sell their excess energy at higher prices compared to conventional feed-in tariffs. This mechanism also reduces reliance on the main grid by facilitating localized energy exchange, thereby minimizing transmission losses and improving overall system efficiency. Furthermore, P2P trading contributes to grid stability by enabling local energy balancing, which mitigates voltage fluctuations and reduces the need for costly infrastructure upgrades. Additionally, by providing a market for surplus renewable energy, it incentivizes greater adoption of distributed energy resources, accelerating the transition toward a more sustainable and decentralized energy system.Despite its advantages, peer-to-peer (P2P) energy trading presents several challenges, including the complexity of implementation and management, requiring advanced metering, communication, and control infrastructure, transaction costs that may reduce financial benefits, regulatory hurdles due to outdated policies, and potential inequitable outcomes for participants with limited access to renewable energy or advanced energy technologies. These mechanisms incorporate day-ahead and real-time trading strategies, aiming to reduce energy costs for agents and overall community operating expenses while enhancing the network’s efficiency and reducing reliance on the upstream grid. Such approaches are instrumental in advancing the functionality and sustainability of energy communities.

5.6. Challenges in the Implementation of OEs for DERs Grid Integration

5.6.1. Network Visibility

Network visibility is a crucial aspect in Operating Envelope (OE) calculations. The lack of information concerning network topology, line impedance, and customers’ phase connections can pose challenges for Distribution Network Operators (DNOs) and impede the calculation of OEs for individual prosumers [

117,

142]. Additionally, determining the operational state of the entire distribution system necessitates voltage magnitudes and angles at all phases of the reference bus, typically located at the high voltage side of the transformer. Real-time network conditions, hybrid approaches incorporating advanced modelling techniques, and the installation of new equipment are essential for accurate OE calculations. It is worth noting that monitoring at distribution transformers is uncommon in distribution companies in Australia. In a study [

143], the authors proposed the use of a Distribution System State Estimation (DSSE) engine on feeders, combined with capacity constrained optimization (CCO), to enhance network visibility and estimate real-time operating conditions at various points in the network. The analysis of this approach in south-east Queensland indicates that previously restricted DERs now have greater opportunities to export energy. Furthermore, this method could enable networks to manage the anticipated growth in electric vehicles and batteries without requiring physical infrastructure upgrades.

5.6.2. Factor of Uncertainties

Uncertainty remains a factor in DOE implementation regarding load or generation due to the intermittent nature of DERs [

125,

144,

145]. Load visibility constitutes a pivotal element in Operating Envelope (OE) computations. Information sourced from prosumers regarding controllable elements including PV solar generators, batteries, and electric vehicles, alongside uncontrollable loads such as air conditioners, hot water systems, electric heating, and various cooking appliances, is imperative. In the context of forecasting, predicting their operational status as exporters or importers is crucial. Forecasting the uncontrolled load of an individual customer can be challenging, but it can be estimated for customers collectively within a specific section of the network. There are a lot of AI Models for load forecasting, but baseline model can be divided into three group: (I) Machine Learning (II)Deep Learning (III) Hybrid Models. Hybrid Models are gaining importance because of less error rate as compared to others. In a study [

146], the author proposed a hybrid technique using a (Convolution Neural Network) CNN and (Multi-layer Bi-directional Long-short Term Memory) M-BDLSTM for short term forecasting of residential load forecasting. In a study [

147], author has proposed AI tools like. a hybrid Convolution Neural Network (CNN) and Gated Recurrent Units (GRU) model for short term load forecasting in residential buildings. These AI tools, with a lower error rate, can make a significant difference in load forecasting using the DOE approach. In another study [

148], the author suggests a risk-based method for multi-period reconfiguration and utilizes Relative Distance Measure (RDM) arithmetic to account for the uncertainty in load and generation from renewable energy sources. In another study, the author presents a framework for an [

149] (ADMS) that integrates a dual-horizon rolling scheduling model based on dynamic AC optimal power flow to address operational uncertainties. Uncertainty poses a significant challenge in the implementation of Dynamic Operating Envelopes (DOEs). This uncertainty can stem from fluctuations in electric power due to the intermittent nature of Distributed Energy Resources (DERs), variations in system load, and errors in power forecasting. Excessive generation or load imbalance can lead to blackouts, underscoring the importance of maintaining system balance amidst uncertainty. Load or generation visibility can be achieved with installation smart metering infrastructure with communication networks, utilizing common approaches such as model-based, data-driven, and physics-informed techniques [

150,

151,

152,

153]. Model-based methods face limitations due to the need for detailed PV parameters and precise meteorological data, while newer approaches integrate physical PV models with statistical models using smart meter and weather data [

153,

154]. The absence of detailed PV array parameters, precise meteorological data, and typical PV generation curves impacted by local conditions like shadows and dirt reduces estimation accuracy.

5.6.3. Calculation of OEs in Terms of Computational and Scalability [145]

Operating Envelopes (OEs) are computed for individual prosumers and disseminated to them by Distribution Network Operators (DNOs). Distribution networks consist of numerous buses, each serving hundreds of thousands of customers. While the current number of prosumers may be low, the scalability and calculation of these OEs for DNOs could pose challenges over time. Innovative algorithms are essential to address this issue, requiring new mathematical modelling techniques for solving complex networks. Reliable operational Low Voltage (LV) network models are crucial for this purpose. In a study [

155], the author proposes a phase Optimal Power Flow method for rapid real-time OE calculations using commercial solvers, contingent upon having complete electrical models of Medium Voltage (MV)/LV networks and smart meter data. In another study of [

156], the author introduces a model-free approach for accurately calculating voltage using smart meter data and artificial intelligence, as an alternative to traditional methods involving power flow analysis and LV network electrical models. This is particularly important for DNOs to monitor voltage fluctuations in networks due to the integration of various DERs. However, the lack of smart meter data from certain customers like commercial and industrial users (managed by third parties) may impede the effectiveness of this approach.

5.6.4. Capacity Allocation to Consumers [141]

Fairness is a crucial factor in the implementation of Dynamic Operating Envelopes (DOEs), regardless of the method or strategy used for calculating Operating Envelopes (OEs). Two customers with identical DER ratings and load patterns may receive significantly different OEs based on their location. Achieving fair allocation can be accomplished through appropriate rules and the formulation of an objective function to guide implementation. Several studies have explored this aspect. In a study [

120], the author demonstrates the effectiveness of a quadratic objective function (Quadratically Constrained Quadratic Program) in promoting fairness among prosumers compared to a linear objective function. In [

157], it is noted that the maximize allocation technique is more advantageous for increasing DER exports compared to equally distributing OEs, due to voltage sensitivity based on location. Therefore, equal allocation of OEs to all customers may not be conducive to maximizing DER integration, considering the varying sensitivities of customers towards network constraints.

5.6.5. Cybersecurity.

As Dynamic Operating Envelopes (DOEs) rely on digital data and communication networks, they are vulnerable to cybersecurity threats. Safeguarding the integrity and security of DOE systems and data is paramount. Cybersecurity is a continuous process as threats and vulnerabilities evolve. It is crucial to stay informed about emerging threats and adjust cybersecurity measures accordingly. Regular assessment and updating of cybersecurity strategies are essential to effectively protect DOEs. Adopting strategies like the zero-trust cybersecurity model, which operates under the assumption that malicious insiders or agents may always be present, can significantly strengthen the overall security and resilience of the system [

158]. Additionally, New cybersecurity technologies developed for industrial IoT (IIoT) applications can also be applied to Distributed Energy Resources (DERs). Because these BTM DERs function autonomously and rely on internet-based communications (IP communications), they can be considered part of the IIoT ecosystem [

159].

6. Discussion

Hosting Capacity (HC) serves as a critical foundation for integrating Distributed Energy Resources (DERs) into distribution networks, playing a pivotal role in reducing carbon emissions and advancing the transition to sustainable energy systems. Accurately assessing HC levels is essential for researchers and stakeholders to ensure the seamless integration of DERs while mitigating potential adverse impacts on network performance. However, HC is not a static value; it varies significantly depending on predefined limiting factors such as bus overvoltage, voltage deviation, line and transformer overload, and protection device miscoordination. While peak load is commonly used as a reference, its reliability diminishes in networks with frequent load variations, underscoring the need for more dynamic and adaptive approaches.

The accurate definition of HC requires a comprehensive consideration of various parameters, including network topology, load conditions, and DER deployment patterns. The choice of methodology depends on the specific objectives of the study, and commercial tools vary widely in terms of cost, functionality, and data requirements. Therefore, selecting the appropriate tool must align with the goals of the network analysis. Emerging artificial intelligence (AI)-based methods for HC analysis present a promising alternative, enabling real-time assessment and facilitating the efficient and sustainable integration of DERs into medium- and low-voltage distribution networks.

High penetration of solar PV and other DERs necessitates a stable and resilient network. Traditional solutions such as voltage regulators, capacitors, and On-Load Tap Changers (OLTCs) remain relevant but must be adapted for smart grids with bidirectional power flow. Strategies like inverter oversizing, coordinated OLTC operation, and Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS) can enhance HC, though they require careful cost-benefit analysis. Power quality issues, such as voltage unbalance and harmonic distortion, can be mitigated through harmonic filters, reactive power control, and Active Power Curtailment (APC). However, excessive curtailment may lead to energy losses, highlighting the need for balanced solutions.

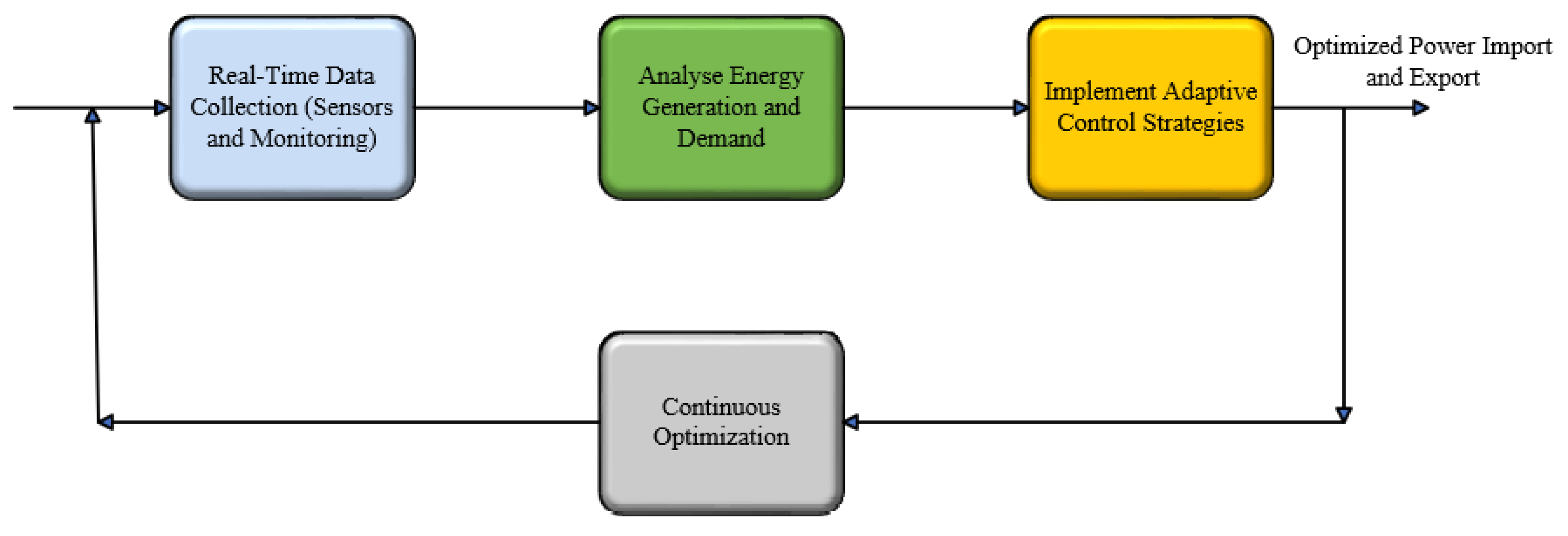

Real-time monitoring, dynamic thermal ratings, and adaptive control systems further optimize HC, emphasizing the importance of standardized procedures and the careful consideration of both technical and economic factors. Among the various techniques for enhancing HC, the concept of Dynamic Operating Envelopes (DOEs) has gained significant traction. Unlike traditional methods that often require costly infrastructure upgrades, DOEs focus on efficient import/export management based on real-time energy generation and demand, minimizing the need for extensive network modifications. The integration of DOEs into energy markets offers additional benefits, attracting energy users due to their cost-effectiveness for both DER and non-DER participants. Moreover, DOEs empower household DER owners to actively engage in energy markets, unlocking financial incentives and fostering greater consumer participation.

The primary objective of DOEs is to implement real-time management of power import and export within low- and medium-voltage distribution networks, optimizing network utilization through dynamic analysis of critical limiting factors and adaptive control strategies. However, several challenges must be addressed for successful DOE implementation:

Innovative Approaches: Novel software, advanced modelling techniques, and sophisticated algorithms are essential to address emerging challenges and enhance DOE functionality.

Real-Time Data: Accurate and reliable real-time data from sensors and monitoring devices is crucial, though it may require significant investment in infrastructure and data management systems.

Alignment with Infrastructure: DOE implementation must align with existing infrastructure, investment plans, and local DER road-maps to ensure compatibility and scalability.

Collaboration: Successful adoption of DOEs requires close coordination among utilities, regulators, technology providers, and researchers.

Regulatory Frameworks: Supportive policies and creative regulatory solutions are necessary to integrate DOEs into modern distribution grids effectively.

Public Engagement: Gaining public acceptance is vital, requiring clear communication of benefits and proactive efforts to address stakeholder concerns. Policies that incentivize participation in energy markets can further enhance public engagement.

Australia serves as a valuable case study, having made significant investments in DOE-related projects, as highlighted in

Section 5.2. However, challenges remain, as discussed in

Section 5.6, particularly in addressing the exponential growth in energy demand. This underscores the insufficiency of relying on a single technique for enhancing HC. Instead, a combination of approaches—such as network reinforcement, advanced control strategies, and market integration—should be adopted to achieve optimal results. Once HC levels are maximized, network augmentation and reinforcement become critical for continued improvement.

Moving forward, researchers and stakeholders must prioritize cost-effective and innovative solutions to address these challenges. By doing so, they can ensure the efficient integration of DERs into distribution networks, paving the way for a more flexible, resilient, and sustainable energy future. This holistic approach will not only optimize DER utilization but also support the global transition toward decarbonized and decentralized energy systems.

7. Conclusions and Future Work

In the context of evolving power systems, the development of cost-effective and innovative strategies will be crucial for maximizing the HC of DERs in both LV and MV distribution networks. The increasing penetration of diverse DERs such as PV, BESS, EVs, and wind turbines requires comprehensive methodologies that can accurately quantify their collective impacts on system stability, power quality, and operational reliability. A deeper understanding of these impacts will facilitate better planning, operation, and integration practices within modern grids.

One of the most promising directions lies in the combined application of advanced HC enhancement techniques and the implementation of DOEs. This integrated approach offers a dynamic and adaptive framework to manage DER operations in real time, helping to maintain network balance while exploiting available HC to its fullest extent. The deployment of DOEs necessitates substantial progress in modelling capabilities, control algorithms, and digital tools that can support precise and scalable operation. In this regard, the adoption of AI and ML can enable predictive and responsive control strategies that effectively account for the stochastic nature of DER behaviour and network conditions.

To accommodate the rising share of DERs, grid infrastructure must also evolve. Cost-efficient reinforcement options such as smart transformers, power electronic converters, and adaptive protection schemes should be considered to enhance grid flexibility and resilience. These technologies will support a smoother transition towards decentralized energy systems without requiring prohibitively expensive overhauls.

Another emerging opportunity is the integration of DOEs within local and wholesale energy markets. Enabling DOEs to actively participate in energy trading frameworks can deliver significant economic and operational advantages for both prosumers and DNOs. Novel market models, including P2P energy trading supported by blockchain and smart contracts, have the potential to democratize energy access and empower consumers by transforming them into active market participants.

Beyond technical solutions, future research should also focus on the regulatory, social, and economic aspects of DER integration. Ensuring interoperability, consumer engagement, and compliance with evolving policy landscapes will be essential to achieving widespread DOE deployment and optimizing DER contributions. Addressing uncertainties in DER forecasting, enhancing network visibility, and developing cyber-secure communication infrastructures will be vital for scaling DOE applications.

Ultimately, a multifaceted strategy that combines HC enhancement techniques, DOE frameworks, and intelligent control systems can pave the way toward a more robust, efficient, and sustainable distribution grid. The transition to a decentralized and decarbonized energy future hinges on continued interdisciplinary collaboration and innovation that aligns technical advancements with policy, regulatory, and social imperatives.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to this work.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors confirm no financial or personal conflicts of interest influenced this work. The study was conducted independently, with no funding from entities having a vested interest in the outcomes.

References

- IEA. Global EV Outlook 2023. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2023 (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. Demand for Electric Cars is Booming with Sales Expected to Leap 35% this Year after a Record-Breaking 2022. Available online: https://www.iea.org/news/demand-for-electric-cars-is-booming-with-sales-expected-to-leap-35-this-year-after-a-record-breaking-2022 (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Haque, M.M.; Wolfs, P. A Review of High PV Penetrations in LV Distribution Networks: Present Status, Impacts and Mitigation Measures. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 62, 1195–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, S.; Püvi, V.; Lehtonen, M. Review on the PV Hosting Capacity in Distribution Networks. Energies 2020, 13, 4756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalobos, J.G. Optimized Charging Control Method for Plug-in Electric Vehicles in LV Distribution Networks [Ph.D. Thesis], 2016.

- Ismael, S.M.; Aleem, S.H.A.; Abdelaziz, A.Y.; Zobaa, A.F. State-of-the-Art of Hosting Capacity in Modern Power Systems with Distributed Generation. Renew. Energy 2019, 130, 1002–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabi, A.; Elphick, S.; David, J.; Pors, A.; Robinson, D. Innovative Approaches for Assessing and Enhancing the Hosting Capacity of PV-Rich Distribution Networks: An Australian Perspective. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 161, 112365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adefarati, T.; Bansal, R.C. Integration of Renewable Distributed Generators into the Distribution System: A Review. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2016, 10, 873–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebad, M.; Grady, W.M. An Approach for Assessing High-Penetration PV Impact on Distribution Feeders. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2016, 133, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaunt, C.T.; Herman, R.; Namanya, E.; Chihota, J. Voltage Modelling of LV Feeders with Dispersed Generation: Probabilistic Analytical Approach Using Beta PDF. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2017, 143, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, M.; Mokhlis, H.; Naidu, K.; Uddin, S.; Bakar, A.H.A. Photovoltaic Penetration Issues and Impacts in Distribution Network – A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 53, 594–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, P.; Mehraeen, S. Challenges of PV Integration in Low-Voltage Secondary Networks. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2017, 32, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Silva, V.; Lopez-Botet-Zulueta, M. Impact of High Penetration of Variable Renewable Generation on Frequency Dynamics in the Continental Europe Interconnected System. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2016, 10, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, S.E.; et al. Impact of Distributed Generation on Protection and Voltage Regulation of Distribution Systems: A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 105, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenicek, D.; Inam, W.; Ilic, M. Locational Dependence of Maximum Installable PV Capacity in LV Networks While Maintaining Voltage Limits. In Proceedings of the 2011 North American Power Symposium, 15 September 2011; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, F.; Mather, B.; Gotseff, P. Technologies to Increase PV Hosting Capacity in Distribution Feeders. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Power and Energy Society General Meeting (PESGM); 2016; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulenga, E.; Bollen, M.H.J.; Etherden, N. A Review of Hosting Capacity Quantification Methods for Photovoltaics in Low-Voltage Distribution Grids. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2020, 115, 105445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abideen, M.Z.U.; Ellabban, O.; Al-Fagih, L. A Review of the Tools and Methods for Distribution Networks’ Hosting Capacity Calculation. Energies 2020, 13, 2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharrazi, A.; Sreeram, V.; Mishra, Y. Assessment Techniques of the Impact of Grid-Tied Rooftop Photovoltaic Generation on the Power Quality of Low Voltage Distribution Network—A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 120, 109643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, F.; Mather, B.; Gotseff, P. Technologies to Increase PV Hosting Capacity in Distribution Feeders. In 2016 IEEE Power and Energy Society General Meeting (PESGM); pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Mulenga, E.; Bollen, M. H. J.; Etherden, N. A Review of Hosting Capacity Quantification Methods for Photovoltaics in Low-Voltage Distribution Grids. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2020, 115, 105445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abideen, M. Z. U.; Ellabban, O.; Al-Fagih, L. A Review of the Tools and Methods for Distribution Networks’ Hosting Capacity Calculation. Energies 2020, 13, 2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharrazi, A.; Sreeram, V.; Mishra, Y. Assessment Techniques of the Impact of Grid-Tied Rooftop Photovoltaic Generation on the Power Quality of Low Voltage Distribution Network—A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 120, 109643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintero-Molina, V.; Romero-L, M.; Pavas, A. Assessment of the Hosting Capacity in Distribution Networks with Different DG Location. In 2017 IEEE Manchester PowerTech; pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Estorque, L. K. L.; Pedrasa, M. A. A. Utility-Scale DG Planning Using Location-Specific Hosting Capacity Analysis. In 2016 IEEE Innovative Smart Grid Technologies - Asia (ISGT-Asia); pp. 984–989. [CrossRef]

- Shayani, R. A.; Oliveira, M. A. G. d. Photovoltaic Generation Penetration Limits in Radial Distribution Systems. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2011, 26, 1625–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balamurugan, K.; Srinivasan, D.; Reindl, T. Impact of Distributed Generation on Power Distribution Systems. Energy Procedia 2012, 25, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carollo, R.; Chaudhary, S. K.; Pillai, J. R. Hosting Capacity of Solar Photovoltaics in Distribution Grids under Different Pricing Schemes. In 2015 IEEE PES Asia-Pacific Power and Energy Engineering Conference (APPEEC); pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Umoh, V.; Davidson, I.; Adebiyi, A.; Ekpe, U. Methods and Tools for PV and EV Hosting Capacity Determination in Low Voltage Distribution Networks—A Review. Energies 2023, 16, 3609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duwadi, K.; Ingalalli, A.; Hansen, T. M. Monte Carlo Analysis of High Penetration Residential Solar Voltage Impacts Using High Performance Computing. In 2019 IEEE International Conference on Electro Information Technology (EIT); pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Baut, J. L. ; others. Probabilistic Evaluation of the Hosting Capacity in Distribution Networks. In 2016 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Conference Europe (ISGT-Europe); pp. 1–6.

- Schwanz, D.; Busatto, T.; Bollen, M. H. J.; Larsson, A. A Stochastic Study of Harmonic Voltage Distortion Considering Single-Phase Photovoltaic Inverters. In 2018 18th International Conference on Harmonics and Quality of Power (ICHQP); pp. 1–6.

- Conti, S.; Raiti, S. Probabilistic Load Flow for Distribution Networks with Photovoltaic Generators Part 1: Theoretical Concepts and Models. In 2007 International Conference on Clean Electrical Power; pp. 132–136. [CrossRef]

- Chihota, M. J.; Bekker, B.; Gaunt, T. A Stochastic Analytic-Probabilistic Approach to Distributed Generation Hosting Capacity Evaluation of Active Feeders. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2022, 136, 107598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saint, B. Update on IEEE P1547.7-Draft Guide to Conducting Distribution Impact Studies for Distributed Resource Interconnection. In PES T&D 2012; pp. 1–2; IEEE.

- Chathurangi, D.; Jayatunga, U.; Rathnayake, M.; Wickramasinghe, A.; Agalgaonkar, A. P.; Perera, S. Potential Power Quality Impacts on LV Distribution Networks with High Penetration Levels of Solar PV. In 2018 18th International Conference on Harmonics and Quality of Power (ICHQP); pp. 1–6.

- Do, M. T.; Bruyere, A.; Francois, B. Sensitivity Analysis of the CIGRE Distribution Network Benchmark According to the Large-Scale Connection of Renewable Energy Generators. In 2017 IEEE Manchester PowerTech; pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Bartecka, M.; Barchi, G.; Paska, J. Time-Series PV Hosting Capacity Assessment with Storage Deployment. Energies 2020, 13, 2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athari, M. H.; Wang, Z.; Eylas, S. Time-Series Analysis of Photovoltaic Distributed Generation Impacts on a Local Distributed Network. In Conference Proceedings; pp. 1–6.

- Tricarico, G.; Gonzalez-Longatt, F.; Marasciuolo, F.; Ishchenko, O.; Dicorato, M.; Forte, G. A Time-Series Hosting Capacity Assessment of the Maximum Distributed Energy Resource Production. In 2023 IEEE International Conference on Environment and Electrical Engineering and 2023 IEEE Industrial and Commercial Power Systems Europe (EEEIC / I&CPS Europe); pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Rogers, L. Hosting Capacity Methods, Applications, Opportunities and Challenges; EPRI: 2019.

- Rylander, M.; Smith, J.; Sunderman, W. Streamlined Method for Determining Distribution System Hosting Capacity. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2016, 52, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rylander, M.; Smith, J.; Sunderman, W. Streamlined Method for Determining Distribution System Hosting Capacity. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Rural Electric Power Conference, Spokane, WA, USA; 2015; pp. 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Tang, L. Practical Power Distance Test Tool Based on OPF to Assess Feeder DG Hosting Capacity. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Electrical Power and Energy Conference (EPEC), Montreal, QC, Canada; 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Gunda, J.; Dowling, R.; Djokic, S. Z. A Two-stage Approach for Renewable Hosting Capacity Assessment. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Europe (ISGT-Europe), Bucharest, Romania; 2019; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Lakshmi, S.; Ganguly, S. Simultaneous Optimisation of Photovoltaic Hosting Capacity and Energy Loss of Radial Distribution Networks with Open Unified Power Quality Conditioner Allocation. IET Renewable Power Generation 2018, 12, 1382–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghian, H.; Wang, Z. A Novel Impact-Assessment Framework for Distributed PV Installations in Low-Voltage Secondary Networks. Renewable Energy 2020, 147, 2179–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakar, S.; Balci, M. E.; Aleem, S. H. E. A.; Zobaa, A. F. Increasing PV Hosting Capacity in Distorted Distribution Systems Using Passive Harmonic Filtering. Electric Power Systems Research 2017, 148, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alturki, M.; Khodaei, A. Optimal Loading Capacity in Distribution Grids. In Proceedings of the 2017 North American Power Symposium (NAPS), Fargo, ND, USA; 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alturki, M.; Khodaei, A. Marginal Hosting Capacity Calculation for Electric Vehicle Integration in Active Distribution Networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/PES Transmission and Distribution Conference and Exposition (T&, Denver, CO, USA, 2018, D); pp. 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Li, Q.; Sheng, M.; Gao, H. An Optimization-Based Approach for the Distribution Network Electric Vehicle Hosting Capacity Assessment. In Proceedings of the 2022 China Automation Congress (CAC), Zhengzhou, China; 2022; pp. 3795–3800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yuan, J.; Weng, Y.; Ayyanar, R. Spatial-Temporal Deep Learning for Hosting Capacity Analysis in Distribution Grids. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2023, 14, 354–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomin, N.; Voropai, N.; Kurbatsky, V.; Rehtanz, C. Management of Voltage Flexibility from Inverter-Based Distributed Generation Using Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning. Energies 2021, 14, 8270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breker, S.; Rentmeister, J.; Sick, B.; Braun, M. Hosting Capacity of Low-Voltage Grids for Distributed Generation: Classification by Means of Machine Learning Techniques. Applied Soft Computing 2018, 70, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Azuatalam, D.; Power, T.; Chapman, A. C.; Verbič, G. A Novel Probabilistic Framework to Study the Impact of Photovoltaic-Battery Systems on Low-Voltage Distribution Networks. Applied Energy 2019, 254, 113669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahriar, S.; Al-Ali, A. R.; Osman, A. H.; Dhou, S.; Nijim, M. Prediction of EV Charging Behavior Using Machine Learning. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 111576–111586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M. T.; Hossain, M. J.; Habib, M. A. Machine Learning-Based Hosting Capacity Analysis and Forecasting in Low-Voltage Networks. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Future Energy Electronics Conference (IFEEC), Singapore; 2023; pp. 461–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chihota, M. J.; Lewis, W.; Bekker, B. Using Machine Learning to Advance Computational Efficiency in Stochastic Hosting Capacity Evaluations. In Proceedings of the IEEE EUROCON 2023 - 20th International Conference on Smart Technologies, Zagreb, Croatia; 2023; pp. 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qammar, N.; Arshad, A.; Miller, R. J.; Mahmoud, K.; Lehtonen, M. Machine Learning Based Hosting Capacity Determination Methodology for Low Voltage Distribution Networks. IET Generation, Transmission & Distribution 2024, 18, 911–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bam, L.; Jewell, W. Review: Power System Analysis Software Tools. In Proceedings of the IEEE Power Engineering Society General Meeting, San Francisco, CA, USA; 2005; pp. 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siemens. PSS®SINCAL – Simulation Software for Analysis and Planning of Electric and Pipe Networks. Available online: https://new.siemens.com/global/en/products/energy/energy-automation-and-smart-grid/pss-software/pss-sincal.html (accessed on day month year).

- Manitoba Hydro International Ltd. PSCAD-Power System Studies. Available online: https://www.pscad.com/engineering-services/power-system-studies (accessed on day month year).

- DIgSILENT. POWERFACTORY Applications. (accessed on day month year).

- NEPLAN. NEPLAN | Target Grid Planning. Available online: https://www.neplan.ch/description/target-grid-planning/ (accessed on day month year).

- Synergi Electric. Power Distribution System and Electrical Simulation Software - Synergi Electric. Available online: https://www.dnv.com/services/power-distribution-system-and-electrical-simulation-software-synergi-electric-5005 (accessed on day month year).

- CYME. CYME Power Engineering Software. Available online: https://www.cyme.com/software/ (accessed on day month year).

- Thurner, L.; et al. Pandapower—An Open-Source Python Tool for Convenient Modeling, Analysis, and Optimization of Electric Power Systems. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2018, 33, 6510–6521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI). OpenDSS-Simulation Tool. Available online: https://www.epri.com/pages/sa/opendss?lang=en (accessed on day month year).

- The National Renewable Energy Laboratory. PyDSS. Available online: https://www.nrel.gov/grid/pydss.html (accessed on day month year).

- PowerModelsDistribution Software Tool. PowerModelsDistribution. Available online: https://lanl-ansi.github.io/PowerModelsDistribution.jl/stable/reference/internal.html#PowerModelsDistribution._dss2eng_load (accessed on day month year).

- Arshad, A.; Lindner, M.; Lehtonen, M. An Analysis of Photo-Voltaic Hosting Capacity in Finnish Low Voltage Distribution Networks. Energies 2017, 10, 1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, F.; Horowitz, K. A. W.; Mather, B. A.; Palmintier, B. Sequential Mitigation Solutions to Enable Distributed PV Grid Integration. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Power &, Portland, OR, USA, 2018, Energy Society General Meeting (PESGM); pp. 1–5.

- Navarro, B. B.; Navarro, M. M. A Comprehensive Solar PV Hosting Capacity in MV and LV Radial Distribution Networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Conference Europe (ISGT-Europe), Warsaw, Poland; 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, A.; Ochoa, L. F.; Randles, D. Monte Carlo-Based Assessment of PV Impacts on Real UK Low Voltage Networks. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Power &, Energy Society General Meeting, Vancouver, BC, Canada; 2013; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Marinelli, M.; Coppo, M.; Zecchino, A.; Bindner, H. W. Coordinated Voltage Control of a Decoupled Three-Phase On-Load Tap Changer Transformer and Photovoltaic Inverters for Managing Unbalanced Networks. Electric Power Systems Research 2016, 131, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jothibasu, S.; Santoso, S.; Dubey, A. Determining PV Hosting Capacity Without Incurring Grid Integration Cost. In Proceedings of the 2016 North American Power Symposium (NAPS), Denver, CO, USA; 2016; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitworawut, P.; Azuatalam, D.; Collin, A. J. An Investigation into the Technical Impacts of Microgeneration on UK-Type LV Distribution Networks. In Proceedings of the 2016 Australasian Universities Power Engineering Conference (AUPEC), Melbourne, Australia; 2016; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, W.; Stauffer, Y.; Ballif, C.; Hutter, A.; Alet, P.-J. Automated Quantification of PV Hosting Capacity in Distribution Networks Under User-Defined Control and Optimisation Procedures. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Conference Europe (ISGT-Europe), Ljubljana, Slovenia; 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- EPRI. Impact Factors, Methods, and Considerations for Calculating and Applying Hosting Capacity; EPRI Report 3002011009; Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2018.

- EPRI. Impact Factors and Recommendations on How to Incorporate Them When Calculating Hosting Capacity; EPRI, 2018.

- Ding, C.; et al. Improvement in Storage Stability of Infrared-Dried Rough Rice. Food and Bioprocess Technology 2016, 9, 1010–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. T. Gaunt, E. Namanya, and R. Herman. Voltage modelling of LV feeders with dispersed generation: Limits of penetration of randomly connected photovoltaic generation. Electric Power Systems Research 2017, 143, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. C. Tang and G. W. Chang, "A stochastic approach for determining PV hosting capacity of a distribution feeder considering voltage quality constraints," in 2018 18th International Conference on Harmonics and Quality of Power (ICHQP), 2018, pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- W. Niederhuemer and R. Schwalbe, "Increasing PV hosting capacity in LV grids with a probabilistic planning approach," in 2015 International Symposium on Smart Electric Distribution Systems and Technologies (EDST), 2015, pp. 537–540. [CrossRef]

- P. Lusis, L. L. H. Andrew, S. Chakraborty, A. Liebman, and G. Tack, "Reducing the Unfairness of Coordinated Inverter Dispatch in PV-Rich Distribution Networks," in 2019 IEEE Milan PowerTech, 2019, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- M. Asano et al., "On the Interplay between SVCs and Smart Inverters for Managing Voltage on Distribution Networks," in 2019 IEEE Power & Energy Society General Meeting (PESGM), 2019, pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Y Dong, X. Xie, W. Shi, B. Zhou, and Q. Jiang, "Demand-Response-Based Distributed Preventive Control to Improve Short-Term Voltage Stability," IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid, vol. 9, no. 5. 2018, 4785–4795. [CrossRef]

- J. Medina, N. Muller, and I. Roytelman, "Demand Response and Distribution Grid Operations: Opportunities and Challenges," IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid, vol. 1, no. 2. 2010; 193–198. [CrossRef]

- D. Sarmiento Nova, P. P. Vergara, L. C. P. Silva, and M. De Almeida, "Increasing the PV hosting capacity with OLTC technology and PV VAr absorption in a MV/LV rural Brazilian distribution system," in Proceedings of a Conference, 2016.

- Y. Y. Fu and H. D. Chiang, "Toward optimal multi-period network reconfiguration for increasing the hosting capacity of distribution networks," in 2017 IEEE Power & Energy Society General Meeting, 2017. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- C. Heinrich, P. C. Heinrich, P. Fortenbacher, A. N. Fuchs, and G. Andersson, "PV-integration strategies for low voltage networks," in 2016 IEEE International Energy Conference (ENERGYCON), 2016, pp. 1–6.

- T. Jamal, C. Carter, T. Schmidt, G. M. Shafiullah, M. Calais, and T. Urmee, "An energy flow simulation tool for incorporating short-term PV forecasting in a diesel-PV-battery off-grid power supply system," Applied Energy, vol. 254. 2019, 113718. [CrossRef]

- T. E. C. d. Oliveira, P. M. S. Carvalho, P. F. Ribeiro, and B. D. Bonatto, "PV Hosting Capacity Dependence on Harmonic Voltage Distortion in Low-Voltage Grids: Model Validation with Experimental Data," Energies, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 465, 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.mdpi.com/1996-1073/11/2/465.

- X. Su, M. A. S. Masoum, and P. J. Wolfs, "Optimal PV Inverter Reactive Power Control and Real Power Curtailment to Improve Performance of Unbalanced Four-Wire LV Distribution Networks," IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Energy, vol. 5, pp. 967–977, 2014.

- S. Ali, M. M. Haque, and P. J. Wolfs, "A review of topological ordering based voltage rise mitigation methods for LV distribution networks with high levels of photovoltaic penetration," Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2019.

- M. A. Sayed and T. Takeshita, "All nodes voltage regulation and line loss minimization in loop distribution systems using UPFC," IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics, vol. 26, no. 6, pp. 1694–1703, 2010.