1. Introduction

Postoperative pain is one of the main concerns dentists must deal with when per-forming surgical procedures like bone regeneration/augmentation. Pain is an unpleasant multidimensional sensation that varies in intensity, quality, duration, and reference. Pain is classified into several types: nociceptive, inflammatory, neuropathic, and functional [

1]. Tissue engineering surgical procedures for bone regeneration unavoidably produce tissue damage, and due to local anesthesia, the nociceptive system ignores the injury and delays the body’s defensive mechanism. This condition induces a systemic reaction through inflammatory pain aimed to heal the injured area by increasing sensitivity in the surgical site. The amplified sensitivity prevents further tissue damage during the postoperative period by minimizing movement or frictional contact of the healing site, such as a standard stimulus, which should usually not cause pain, but in the presence of a hypertensive area, the healing site will respond painfully. Therefore, clinicians must pharmacologically control the inflammatory pain without interfering with the healing process. Hence, the anti-inflammatory/analgesic treatment should aim to manage and not suppress the symptoms [

2].

To achieve the above and strive for the patient’s comfort, analgesics are prescribed systemically after the procedure. A long-time used drug with great potential and versatility is tramadol (TMD) due to its moderate analgesia capacity, synergy with anti-inflammatories, low possibility of causing allergic reactions, and efficacy in treating incisional pain. Some common side effects of TMD include nausea (6.1%), dizziness (4.6%), drowsiness (2.4%), fatigue (2.3%), sweating (1.9%), vomiting (1.7%), and dry mouth (1.6%). Although TMD has been demonstrated to be a broad-spectrum analgesic as a unimodal agent or combined with other analgesics, the side effects may contribute to clinicians’ preference for different therapeutic approaches [

3]. To reduce these unwanted effects, lower doses of TMD, used locally at the injury site, have been recommended. Local analgesia achieves a high local concentration of the drug with lower systemic levels, limiting adverse effects. In addition, pharmacological interactions are minimized and the use of the drug is facilitated without being limited depending on the tolerability dose [

4]. Clinical positive results were obtained when TMD was placed into the tooth socket after third molar extractions, improving healing tolerance [

5]. Studies have looked into the efficacy of combining TMD with local anesthetics such as lidocaine, mepivacaine, and articaine in local infiltration anesthesia procedures in the maxillae. In the case of lidocaine, it improved the anesthetic effect, healing, and perception of pain in patients [

6,

7]. The combination of TMD-mepivacaine showed encouraging results in the inferior alveolar nerve block, where the synergy between TMD-articaine for the surgery of impacted third molars and in the treatment of symptomatic irreversible pulpitis pain was clinically demonstrated [

8].

Peripheral analgesia has been achieved through topical gels or creams, patches, aerosols, mouthwashes, and, the use of membranes for the controlled release of drugs locally [

4]. Membranes are commonly used in dentistry for regenerative procedures, especially for guided bone regeneration. They are an essential element of tissue engineering based on its three main components: cells, their extracellular matrix (ECM), and a signaling system. Controlled manipulation of the extracellular microenvironment seeks to boost the ability of cells to organize, grow, differentiate, form an ECM, and, ultimately, develop new functional tissue [

9]. The use of a membrane is fundamental, as it works as a barrier for soft tissues in guided bone regeneration processes and acts as a scaffolding to reconstruct soft tissues during the healing process of a wound. Membranes’ desirable characteristics include biocompatibility, cell occlusion properties, integration capacity to host tissues, clinical manageability, space-creating ability, and suitable physico-mechanical properties. Resorbable membranes have been developed as a second generation of membranes that emerged to avoid the second surgical intervention that implied the removal of the non-resorbable membranes [

10].

Resorbable membranes for bone regeneration have traditionally been synthesized with polymers using various manufacturing techniques. This polymer-based material provides porous and three-dimensional membranes, striving to create a biomatrix framework with resemblant geometric characteristics to the ECM, in which a cell interacts with its substrate [

11,

12]. Biodegradable polymers used to manufacture membranes are further classified as natural or synthetic. Polylactic acid (PLA) is highly relevant as a synthetic polymer with great potential in biomedical applications [

9]. Among PLA’s various qualities, we can mention its workability, processability, biodegradation, low cost, and drug encapsulation capacity [

11,

13,

14,

15,

16],

17.

Some of the most traditional methods for manufacturing polymeric membranes and scaffolds are electrospinning and air jet spinning (AJS). The AJS technique can be considered the most advantageous from the point of view of industrialization and scalability because it’s faster and easier to use, it’s less expensive than other techniques, safe because it does not use high voltage in the processing, and its versatility in the choice of solvent. AJS uses pressurized gas dispensed at extreme speed to stretch the polymer solution into thin fibers, which, as mentioned, are deposited on a substrate, producing micro and nanoscale fibers of different polymers [

10,

17,

18].

Polymer therapy is a growing and important area of biopharmaceuticals that seeks to use linear or branched polymer chains as a bioactive element to which a therapeutic agent (usually a drug) is covalently bound. This binding improves its pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties such as an increased plasma half-life (less frequent dosing is required), resistance to proteolytic enzymes, reduced immunogenicity, better protein stability, better low drug solubility, low molecular weight, and the potential for locally directed action [

17,

18,

19,

20]. The development of more efficient, biocompatible, biodegradable barriers and scaffolds that can be used for tissue engineering and could also provide a slow controlled drug delivery system, releasing an analgesic drug locally to provide lasting comfort for patients undergoing a regeneration treatment, is still an undergoing process. Hence, the objective of this study was to produce TMD-loaded PLA nanofibers to manufacture resorbable membranes using the AJS technique with stable and biocompatible physicochemical characteristics.

3. Discussion

The AJS technique was chosen mainly due to the feasibility to customize and synthetize PLA nanofibrillar membranes to be used as a drug delivery system. This technique offers important advantages such as low-cost synthesis equipment, fabrication speed and non-voltage source needed [

18,

21]. In our research, the AJS method allowed a predictable way to obtain 10% PLA membranes with and without TMD at a concentration of 80 : 1. As indicated by Medeiros et al. who compared the efficiency of the AJS and electrospinning methods; AJS method allows to obtain a range of micro and nanofibers from different polymer solutions in the same size range as fibers made by electrospinning but with greater potential for commercial scale-up; offering also the possibility to coat different kinds of materials including those sensible to thermal changes or voltage sensitive polymers. To assure a proper result from AJS method, there must be an optimal relationship between gas flow pressure, solution feed rate and working distance for the solvent to evaporate and form solidified naonfibers on the receptor [

22]. Previous study analyzed the correlations between solution-blown, fiber morphology and annular turbulent airflow fields under different air pressures, that straight segment length of the polymer solution jet, velocity fluctuations, flapping motion and solvent evaporation affect the final fiber morphology, with more uniform and smaller diameters when air pressure was increased; however, more uneven fibers are obtained and the appearance of some fiber strands [

23].

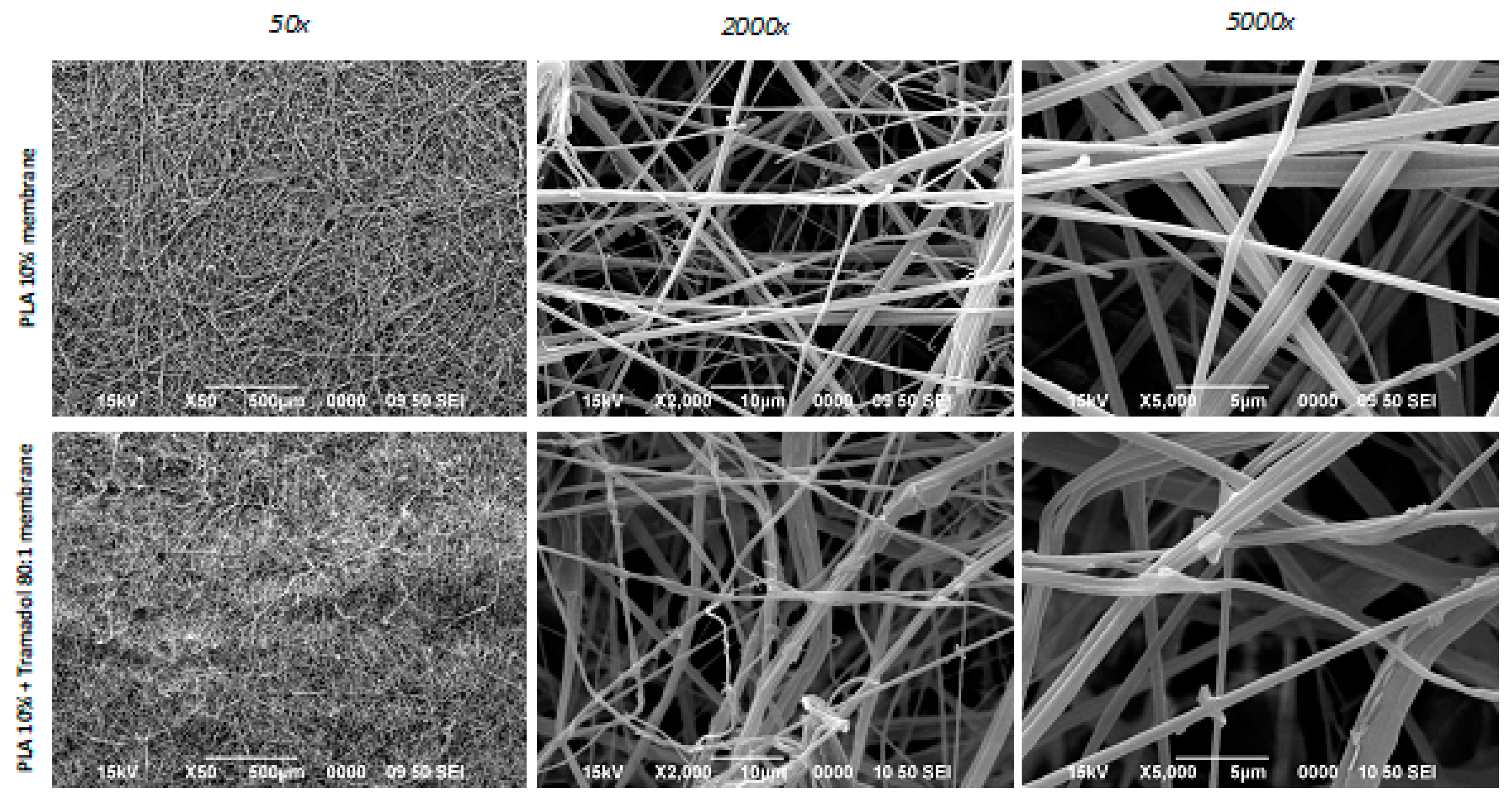

Stojanovska et al, developed a list of parameters to be considered during the processing of membranes and scaffolds by AJS, where they highlighted the polymer concentration, air pressure, diameter of the ejector nozzle, and synthesis distance as the main aspects to control [

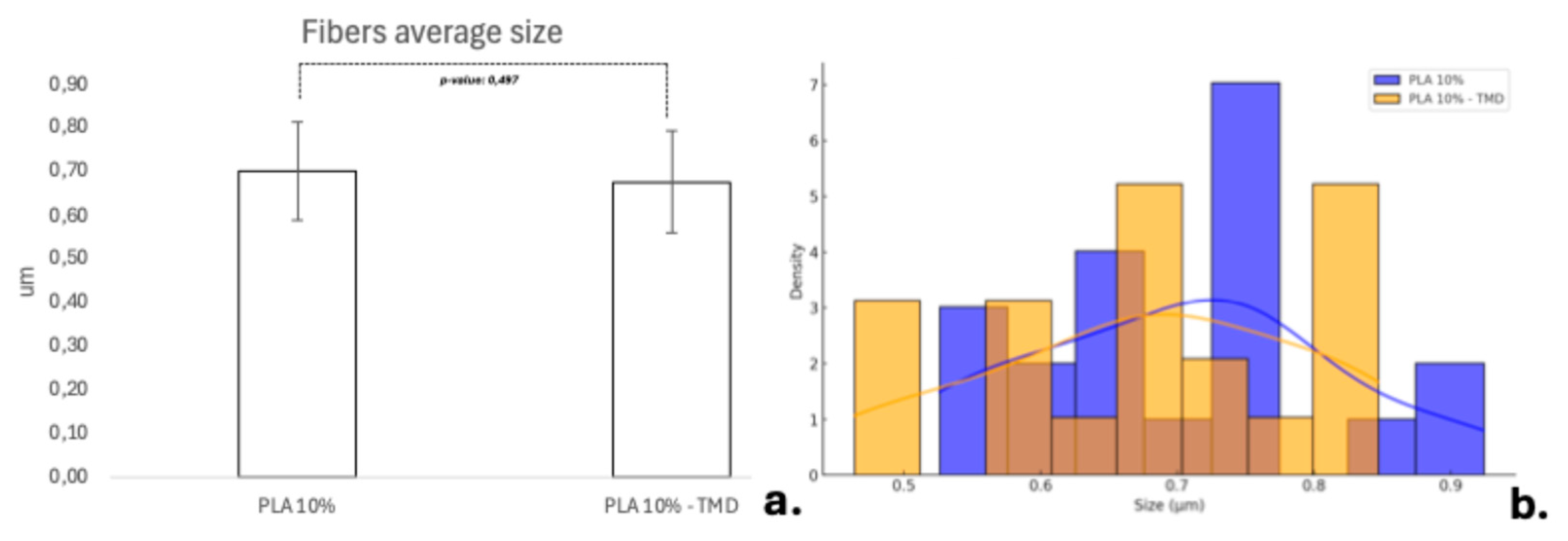

17]. In the present investigation, an air pressure of 30 psi, a 0.3 mm exit nozzle pointed to a receptor frame located at a distance of 11 cm and a PLA concentration of 10% PLA was selected, based on the methodology used by Suarez-Franco et al, who studied the influence of PLA concentration at 6%, 7% and 10% on membrane biocompatibility, concluding that cell adhesion and proliferation was improved with the highest concentration [

11]. Although lower concentrations were also considered, preliminary pilot data showed that the formation of nanofibers was also enhanced at this concentration once the drug was added. With respect to the concentration of the drug, previous tests performed determined that the 80:1 concentration was the most favorable in terms of fiber stability and drug stability. By combining the PLA concentration and drug charge, it was possible to obtain membranes with similar microtopographic characteristics, showing random distribution of polymer nanofibers oriented in various planes and angulations, with a fiber size not exceeding a 5 µm diameter. PLA is an excellent biomaterial to achieve characteristics such as those achieved in the present study and that favor the qualities as a scaffold for tissue regeneration, but its use in bone regeneration procedures has been debated because of its mechanical qualities, however, criticisms are made when the membranes have been fabricated by electrospinning and not AJS, being the AJS technique the one that most favors random deposition, fiber morphology, pore formation and polymeric solution behavior to achieve better physico-mechanical qualities; However, in the present study, a difficult handling of the samples was noted, so future studies should focus on improving this aspect, as cited by Bharadwaz et al, who indicate that to improve the mechanical strength of PLA scaffolds, it has been opted to make mixtures with other polymeric fibers or modify the structure of the polymer as such [

24,

25,

26].

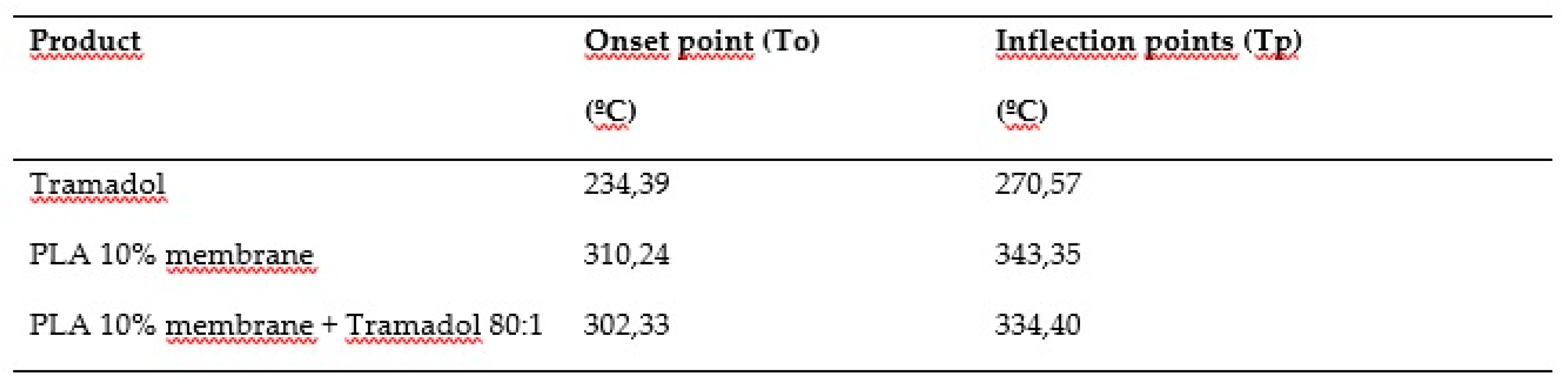

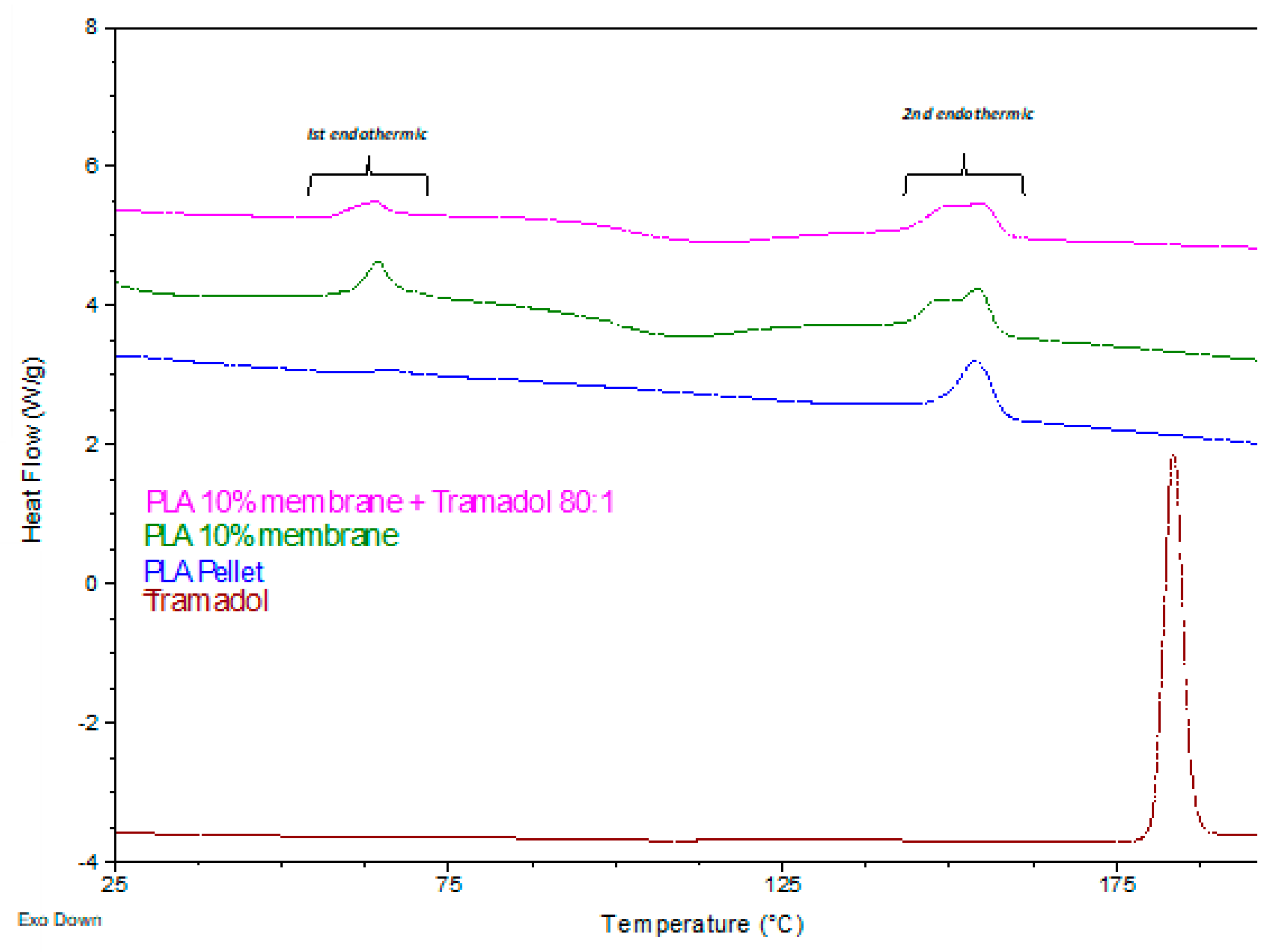

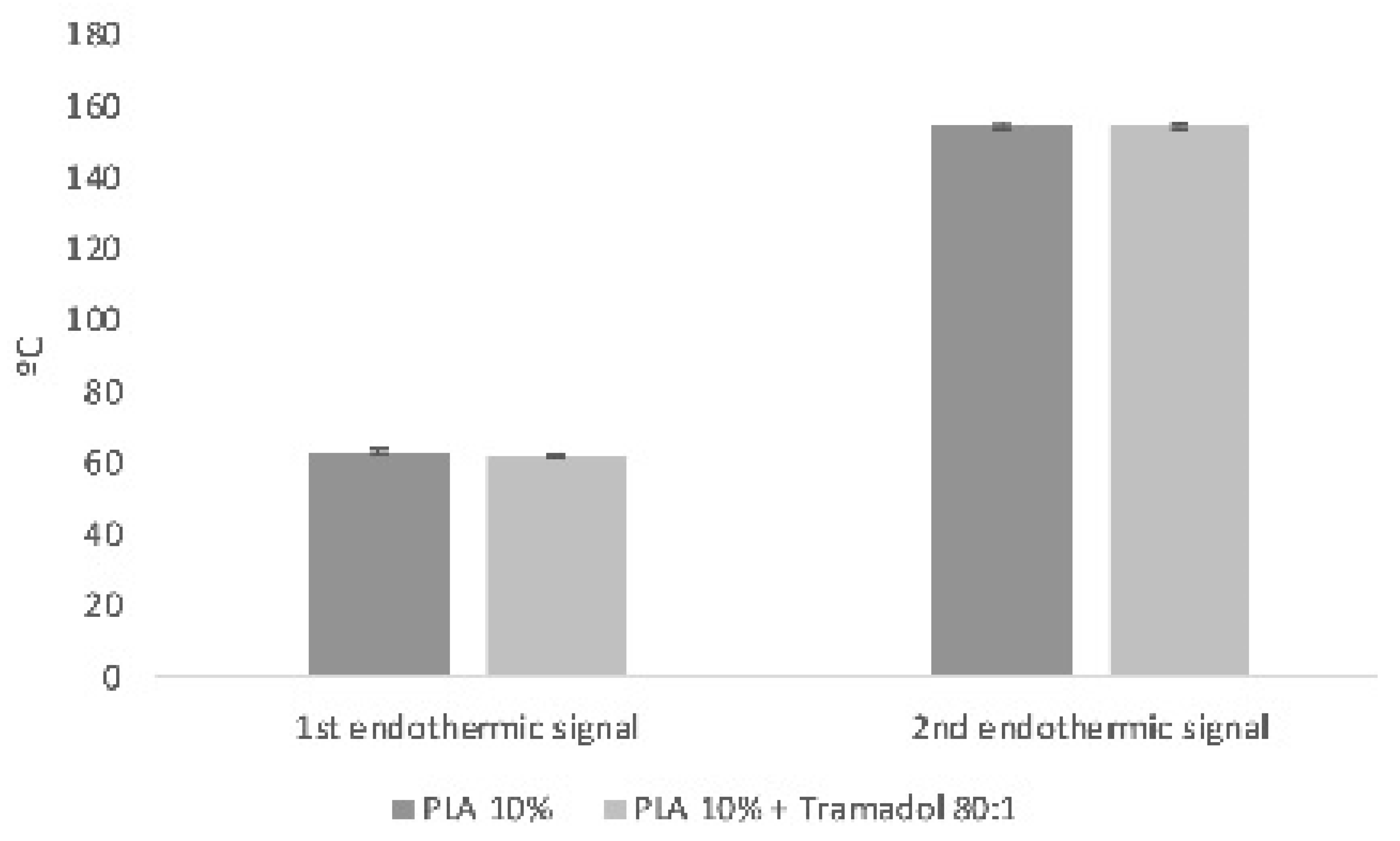

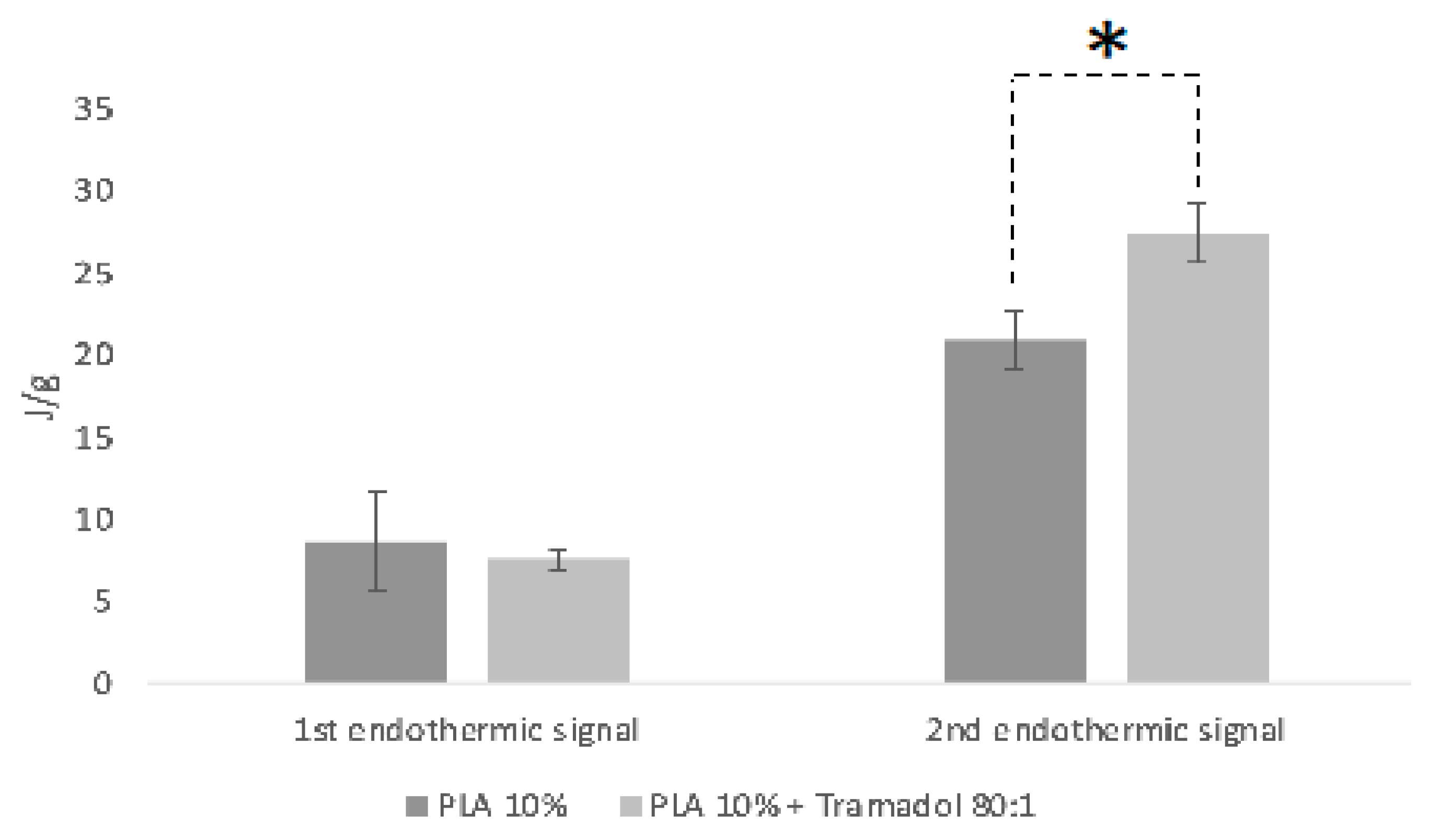

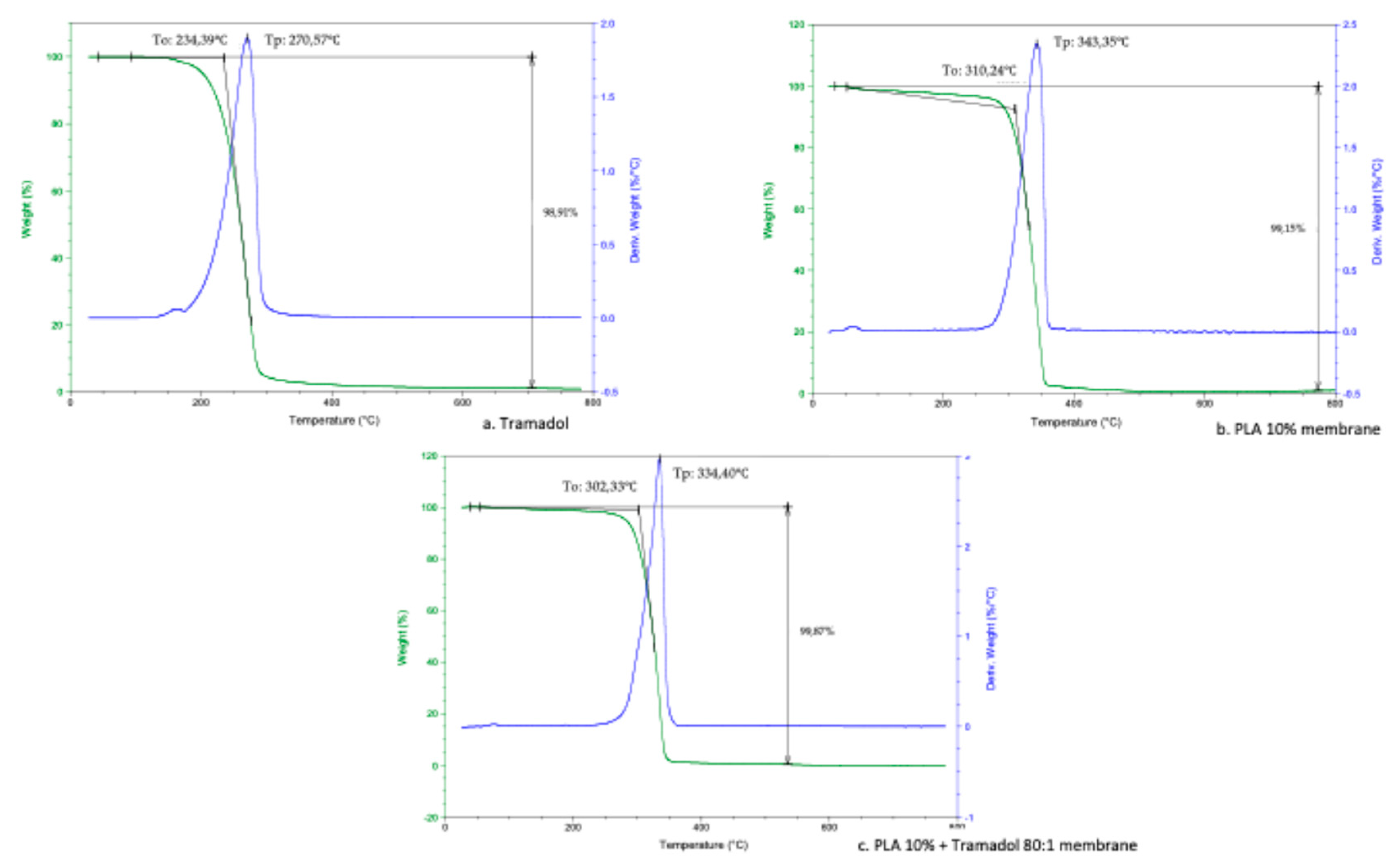

Thermodynamic analyses obtained by DSC and TGD allowed to analyze the effect of the components added to a polymeric matrix and its homogeneity and stability, as well as the presence of impurities or contaminants from the manufacturing process. DSC demonstrate the absence of the characteristic endothermic peak of TMD, which is identifiable at approximately 180°C. Such absence could be due to the loss of the crystalline structure of the drug once dissolved and mixed with the polymer [

27]. In addition, a change in the thermal capacity of the charged membrane was identified, for which it is assumed that the drug was homogeneously and stably incorporated in the system. A similar finding was reported by Kumar et.al. when samples of an alginate- gelatin gel loaded with TMD was analyzed by DSC. They noticed the absence of the drug endothermic signal, indicating that it is a product of a possible shielding of the TMD by a drug-polymer inclusion complex [

28]. Present results showed a remarkable change in the thermodynamic profile of the membranes charged with TMD. As previously reported, a change in the mass of the materials implies a chemical change that is reflected in the thermodynamic characteristics [

29,

30]. In the TGA the presence of TMD, decreases the To and Tp of the PLA 10% membrane, behavior similar to the study of Maubrouk et al, where the effect of TMD in poly(Ɛ-caprolactone) tapes was assessed [

31]; in addition, the TGA demonstrated the efficiency of the method of handling and production of the samples by not identifying process impurities.

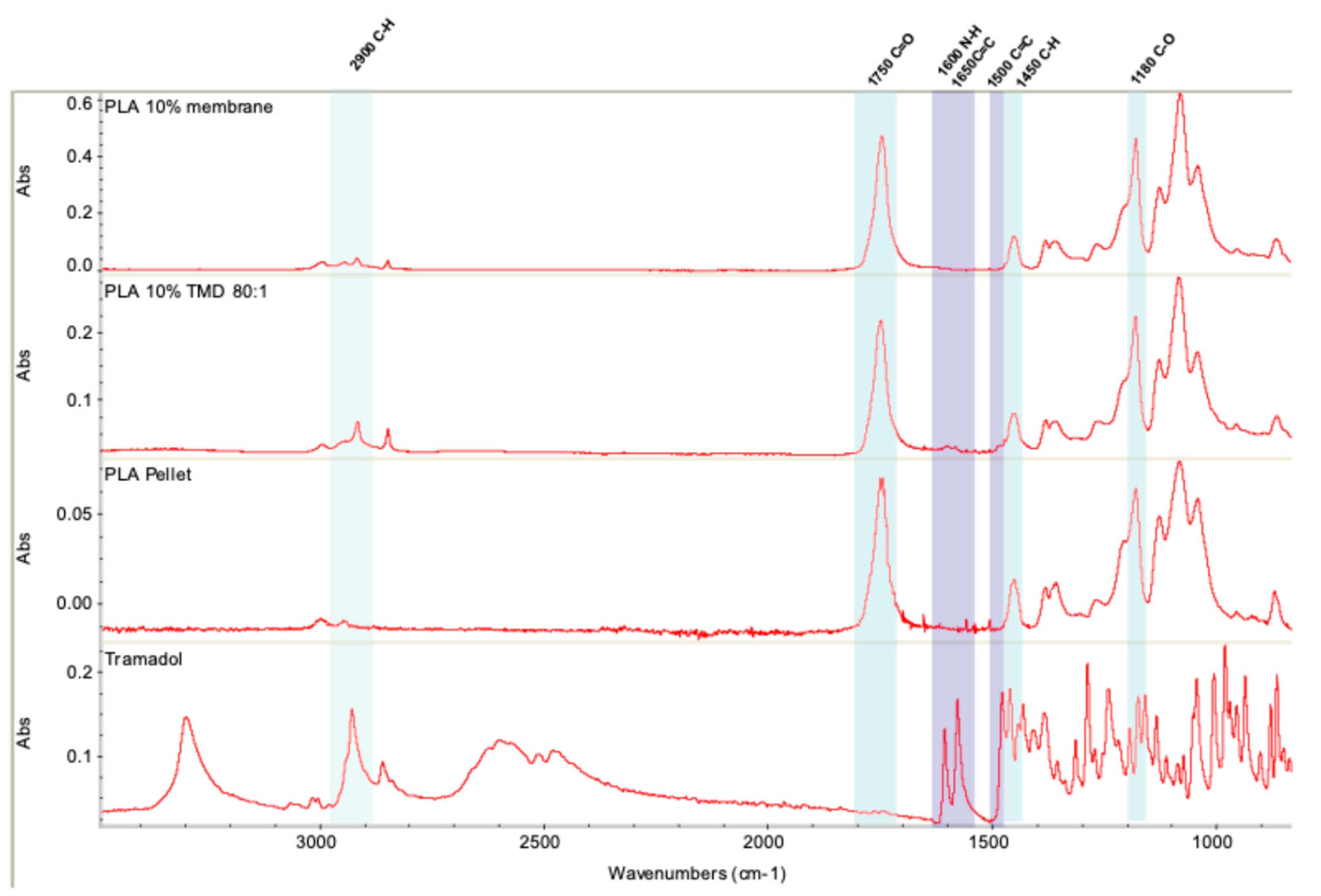

The incorporation of TMD into the 10% PLA membrane was evaluated by Fourier transform infrared spectrometry (FT-IR). The results show that the manipulation of the polymer for the synthesis of the membranes does not alter its composition. Similarly, the incorporation of TMD is compatible with the polymeric system, and does not affect the infrared profile, which is in agreement with previous studies that incorporated the drug into a polymeric matrix [

28,

29,

32,

33,

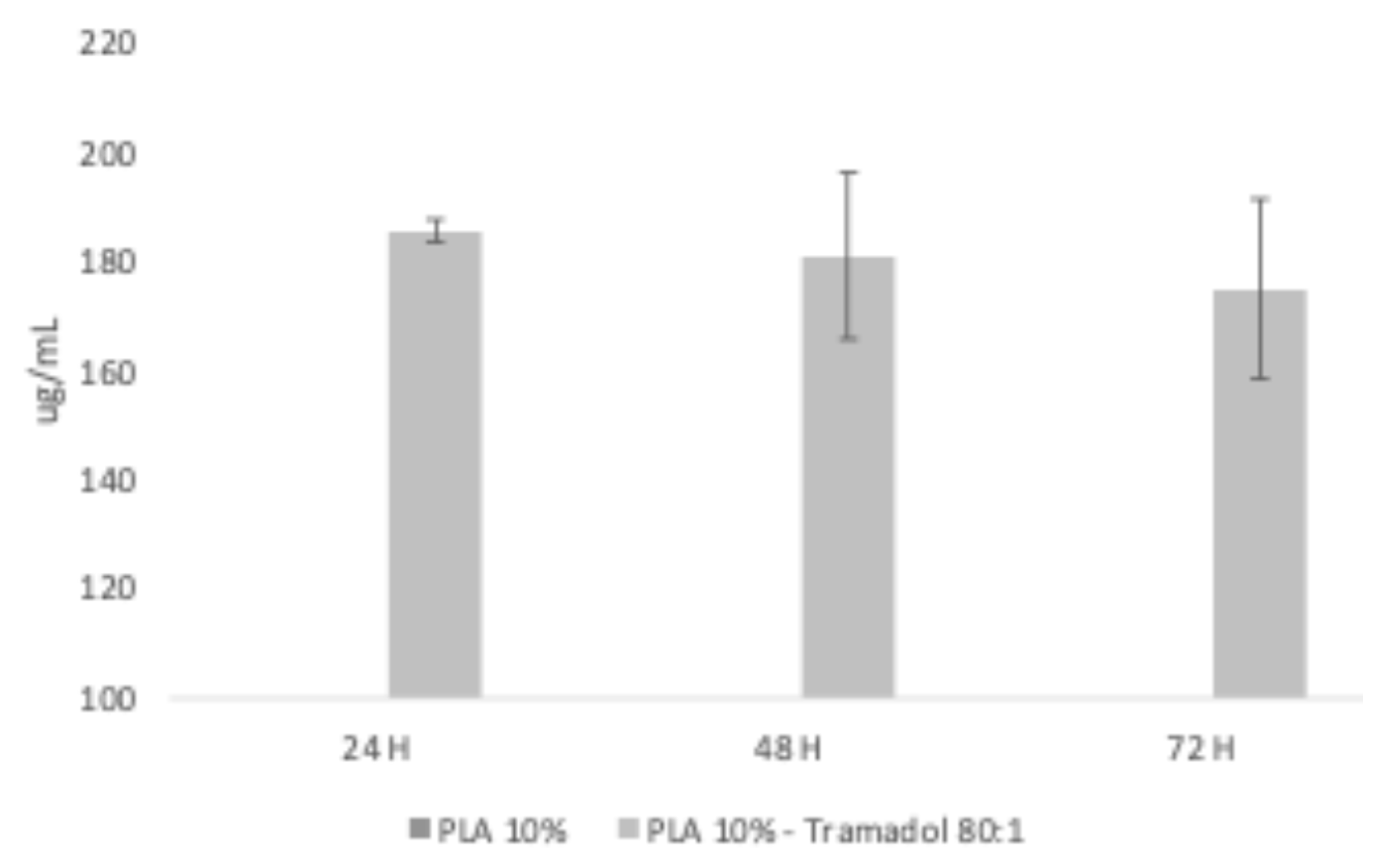

34]. In order to verify that the TMD was loaded on the membranes and that it can be release from the matrix, UV-VIS analysis was used. According to Küçük and Kadıoğlu, it is possible to determine the presence of TMD in methanol and water by means of an ultra violet spectrophotometer at a reading wavelength of 271 nm [

35], while PLA is measurable at approximately 230nm. The controlled release assay performed to the membranes demonstrated that it was possible to recover TMD form the water aliquots, identifying the presence of TMD at 24, 48 and 72 h. Future studies will be designed to analyze the relationship between theoretical and recovered loading; as well as the release kinetics as a function of time. A limitation of the present study was that recovery aliquots were obtained using only distilled water grade 3, with a pH between 5.0 and 7.5 at 25°C according to the ISO 3696 Standard [

36]. Therefore, future studies should evaluate the behavior of the membrane with the drug in other media such as different pH levels, or biological fluids such as saliva or blood [

29].

To determine the biocompatibility of the samples, the cytotoxicity of 10% PLA membranes and 10% PLA membranes with TMD was evaluated by means of staining tests to quantify cell adhesion and proliferation. As it was previously reported, the cellular behavior is influenced by the environment, so customized scaffolds must try to resemble the microarchitecture of the ECM. Therefore, polymeric matrices must provide an environment that allows these dynamic behaviors of cells through nanopores and fibers morphologically compatible with the minimum mechanical requirements [

11,

37,

38]. The biocompatibility of PLA scaffolds is widely accepted. Granados-Hernandez et al. evaluated the response of human bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells in 10% PLA scaffolds obtained by AJS, showing that after different culture periods cytotoxicity was absent [

21]. In the present study, the use of a line of human fetal osteoblasts and the crystal violet staining assay, allows confirming the biocompatibility of the unloaded scaffolds, and the possible biological changes under the presence of TMD, since, the staining detects only living cells due to the fact that the dye binds to the chromatin and nucleus of them. The membrane results obtained were consistent with previous reports that have used a methodology similar to the one presented here, confirming that the designed scaffolds are suitable for enhancing cell proliferation [

39,

40]. The results also showed an increased growth in the charged scaffold, which was slightly decreased but not inhibited by the presence of TMD. These results confirmed that charged membranes didn´t generate an immediate cytotoxic response.

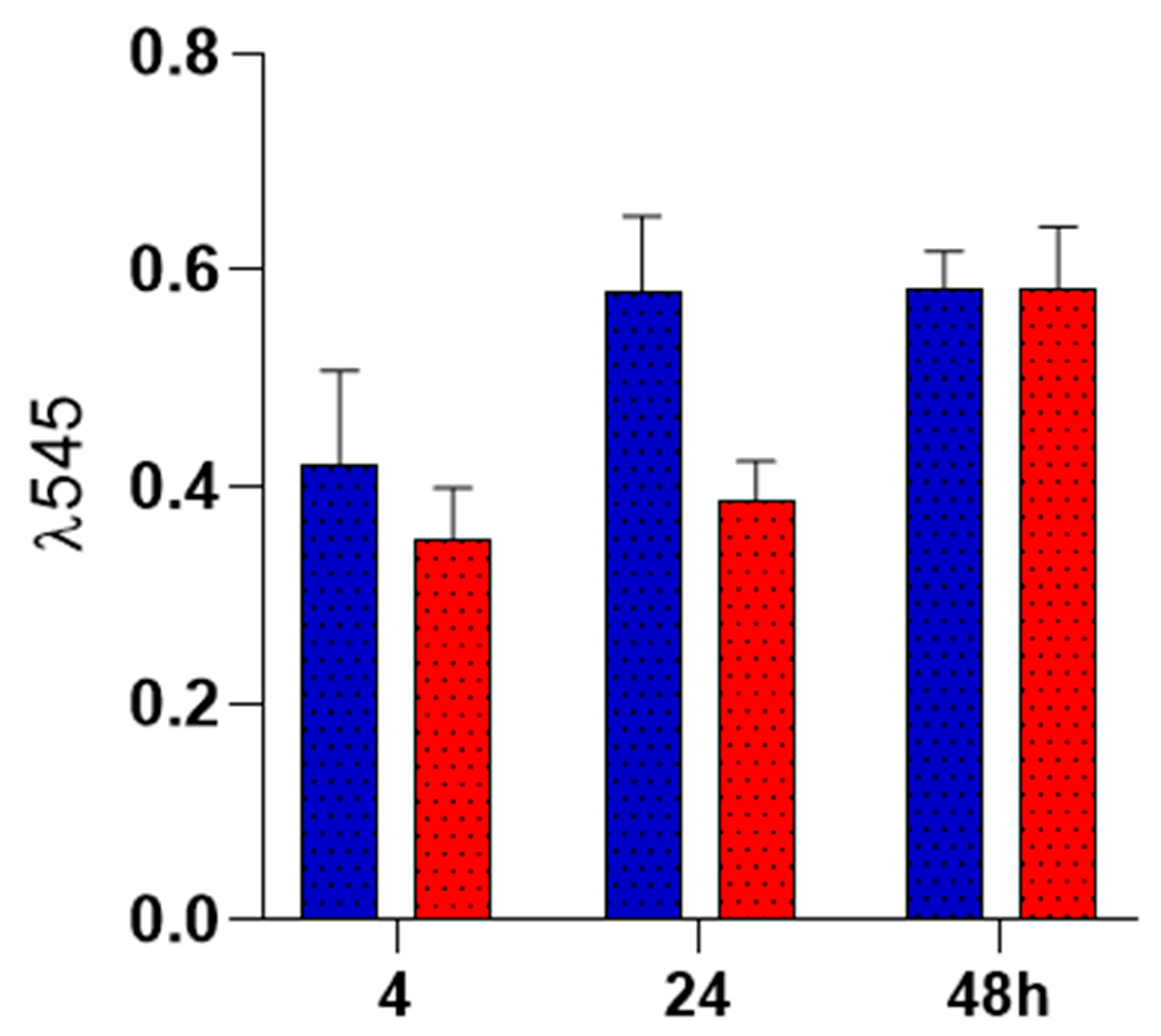

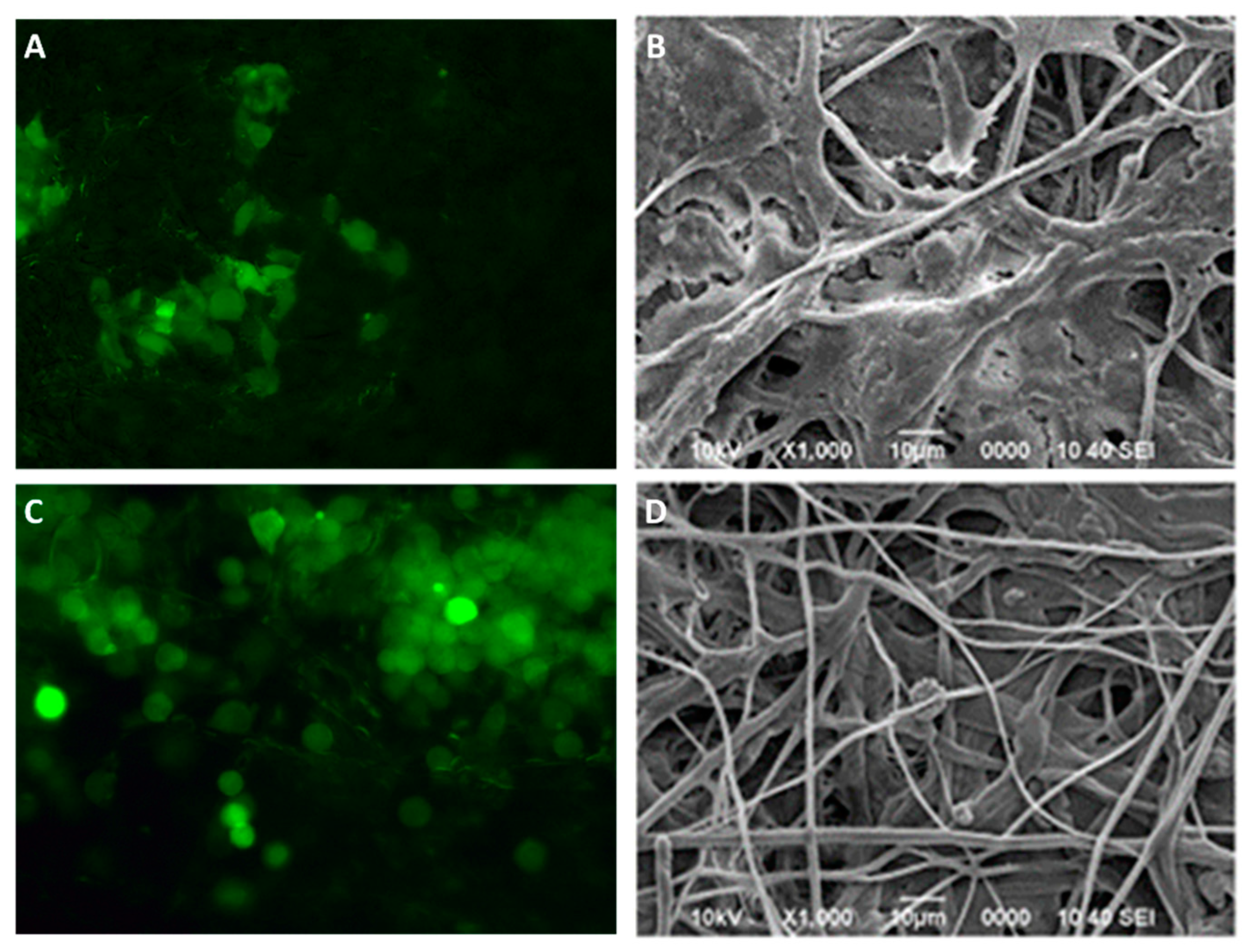

Cell adhesion on the surface of the membranes was also evaluated, showing no difference between groups at 24 and 48 h. To determine this, the rezasurin staining test was used to evaluate cell adhesion due to its non-toxic permeability to the cells. It also offers important information about cell vitality, since its reduction to resofurin depends of mitochondrial activity [

41]. TMD-loaded membranes shown a biocompatible behavior since cell adhesion was maintained during observation periods, and was comparable to control membranes. The cell-membranes interaction was evaluated by fluorescence microscopy and scanning electron microscopy. Fluorescence microscopy allows to evaluate not only cell viability on the membranes, but also their distribution and morphology. Because the CellTracker™ has an affinity for lipids, the stain will only emit its signal upon binding to the intact cell membrane. In the microphotographs, cell presence and viability were observed at 48 h post culture and was comparable between both groups. In addition, we can identify the position and homogeneous distribution of the cells on the membranes, the hexagonal morphology characteristic of osteoblasts, and it was possible to identify cytoplasmic prolongations to start interacting with neighboring cells by means of their lamellipodia, all of which indicates that charged membranes with TMD 80:1 didn´t affect cellular response. Scanning electron microscopy also showed some of the behavior observed by fluorescence, confirming in tridimensional images the cell morphology and surface integrity. These findings support that these nanofibrillar membranes offers promising biological properties to enhance cellular response [

18,

38,

39]. A key aspect to achieve biocompatibility was the low dosage of TMD present in the membranes, and the avoidance of chemical toxins after the membrane’s synthesis. According to dos Santos, in his study on hydrogels for TMD administration, the higher the concentrations of the drug, the higher the in-vitro cytotoxic potential and this harmful effect could be attenuated by the medium used to transport the drug [42]. Therefore, the PLA could be counteracting the cytotoxicity of the drug and this could explain the reason why the experimental group did not have such a large increase in cell proliferation as the control group, but ultimately it did increase but slightly. Future research should analyze whether the dose of TMD in the membranes is sufficient to achieve the desirable clinical effects.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Polymer Fiber Fabrication of PLA Loaded with Tramadol

Fibrous spun scaffolds were fabricated via the air jet spinning process from PLA polymeric solutions of 10 % wt. First, polymeric solutions of 10 % wt of PLA were prepared: PLA pellets (C3H6O3; molecular weight (MW) 192,000, designated Ingeo Biopolymer 2003D from Promaplast, Mexico) were dissolved in chloroform (CHCl3) and stirred for 20 hours. After that, anhydrous absolute ethyl alcohol (CH3CH2OH, J. T. Baker) was added, and let the solution stirring for 30 minutes up to obtain a homogeneous solution. The volume ratio of chloroform/ethanol was 3:1. Then, the polymeric solution was prepared with tramadol (Tramadol HCL, code 15101782, lot 3735ID12) to obtain a mixture with a volumetric ratio of 80:1 for the composite fiber scaffold. The synthesis of the membranes, in all cases, the polymeric solution was placed in a commercially available airbrush ADIR model 699 with a 0.3 mm nozzle diameter and with a gravitational feed of the solution to synthesize the fiber membrane scaffolds. The airbrush was connected to a pressurized argon tank (CAS number 7740-37, concentration > 99%, PRAXAIR Mexico). For deposition of the fibers, a pressure of 30 psi with 11 cm of distance from the nozzle to the target was held constant. Once the fibers were obtained, they were subjected to analysis of their physicochemical and structural properties.

4.2. PLA Loaded with Tramadol Fiber Scaffold Characterization

The morphology and structure of the fibers were observed with a scanning electron microscope (SEM, JSM 7600F, JEOL, USA). Chemical structure of fibers was analyzed by Fourier transform infrared spectrophotometer (FTIR) employing the Nicolet iS50 (ThermoFisher, Madison, USA) spectrometer within the 400–4,000 cm−1 range.

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was done using TGA-Q500 equipment (TA In-struments, Delaware, USA). Platinum baskets were tared before automatically weighing 4-6 mg of the sample to be analyzed. After loading, the furnace was closed and running on a ramp from 25 °C to 800 °C, with a heating rate of 10 °C/min. Data were analyzed using TGA software (Universal V4.5A TA Instruments) to identify onset points (To), inflection points (Tp), and maximum mass loss point (Tmax).

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) (Q200, TA Instruments, Delaware, USA) was performed with 2 mg of each sample, running a ramp from 25 °C to 250 °C, with a heating rate of 10 °C/min. Glass transition temperature (Tg) and melting points (Tm) were calculated.

UV-Vis spectroscopy was used to confirm the presence of TMD in the synthesized membranes and the release from the spun scaffold. The equipment was first calibrated using a TMD curve (271 nm wavelength). Then, membrane specimens weighing 23 mg of the experimental group were placed in a Transwell system with 12 mm diameter inserts and polycarbonate membranes with 0.4µm pores. Each well was filled with 1.5 mL of distilled water and incubated at 37°C and after 24, 48, and 72 h, after the time 1 mL aliquot was retrieved for spectroscopy analysis. The experiment was performed in triplicate.

4.3. In Vitro Studies

Human fetal osteoblast cells (hFOB, 1.19 ATCC CRL-11372) was used to evaluate the cell biocompatibility response of PLA fibers spun mat and PLA loaded with tramadol. hFOB cells were cultured in 75 cm2 cell culture flasks containing a 1:1 mixture of Ham´s F12 medium Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Media (DMEM, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA), supple-mented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Biosciences, USA), 2.5 mM L-glutamine and antibiotic solution (streptomycin 100 μg/mL and penicillin 100U/mL, Sigma-Aldrich). The cell cultures were incubated in a 100% humidified environment at 37°C in 95% air and 5% CO2. hFOB on passages 2-6 were used for all the experimental procedures. Before the biological assays, PLA fibers spun mat and PLA loaded with tramadol were sterilized by UV light for 10 min. To evaluate the cell viability of the hFOB onto fiber scaffold, cells were seeded at 1x104 cells/mL and analyzed after 24, 48, and 72 h of culture. The viability was checked by the resazurin colorimetric assay after prescribed time 20 µl of resazurin solution (BioReagent R7017, CAS number 62758-13-8) was added to the samples and incubated for 4 h at 37°C. Then, 200 μL of the supernatant was removed, and absorbance was quantified by spectrophotometry at 545 nm with a ChroMate plate reader (Awareness Technology, MN, USA).

Colonization and spreading interaction of hFOB cells seeded at 1 x 104 cells/mL onto PLA fibers spun mat and PLA loaded with tramadol were examined after 48 h using SEM and epifluorescence microscopy. For fluorescence observation, before seeding the hFOB 1.19 cells onto the fiber membrane scaffold, cells were incubated with CellTracker™ Green (CMFDA, 5-chloromethylfluorescein diacetate) in phenol red-free medium at 37°C for 30 min. Subsequently, the cells were washed with PBS and incubated for 1 h in a complete medium. Then, hFOB 1.19 cells were trypsinized and counted to the desired cell concentration (1 x 104 cells/mL) incubated for 48 h and examined under the epifluorescence inverted microscopy (AE31E, MOTIC). For SEM analysis, after 48 h of incubation, scaffolds were washed three times with PBS, fixed with 2% glutaraldehyde, then dehydrated with a graded series of ethanol (25-100%) and air-dried. Next, the samples were sputter-coated with a thin layer of gold and examined by SEM.

4.4. Statistic Analysis:

Fiber’s diameter was analyzed, and average data was compared by T-test. For the biocompatibility tests, the statistics were performed using Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) and the Wilcoxon test for the DSC data analysis.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, L. F.-M., F. V.-V., A. P.-G., and D. Ch.-B.; methodology, L. F.-M., M. M.-A., J. S.-B., R. P.-R., and D. Ch.-B.; software, M. M.-A., J. S.-B., and J. B.-V.; validation, M. M.-A., F. V.-V., R. P.-R. and D. Ch.-B.; formal analysis, M. M.-A., A. P.-G., and D. Ch.-B.; investigation, L. F.-M., F. V.-V., R. P.-R.; resources, J. B.-V. R. P.-R., F. V.-V., and D. Ch.-B.; data curation, L. F.-M., F. V.-V., and R. P.-R.; writing—original draft preparation, L. F.-M., F. V.-V., and D. Ch.-B.; writing—review and editing, M. M.-A., F. V.-V., J. S.-B., R. P.-R., A. P.-G., and D. Ch.-B.; visualization, M. M.-A., J. S.-B., R. P.-R., and D. Ch.-B.; supervision, A. P.-G., and D. Ch.-B.; project administration, D. Ch.-B.; funding acquisition, J. B.-V., and D. Ch.-B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

) and control 10 % PLA spun mat (

) and control 10 % PLA spun mat ( ).

).

) and control 10 % PLA spun mat (

) and control 10 % PLA spun mat ( ).

).