1. Introduction

Obesity is a complex metabolic disease with significant implications beyond aesthetics [

1,

2,

3], and it represents a global health challenge affecting more than 2.5 billion adults worldwide. Effective treatment requires a comprehensive approach, incorporating interventions that range from nutritional education to surgical procedures [

4].

Although not classified as a mental disorder by the diagnostic classification criteria (DSM-5 [

5] or ICD-11 [

6]), obesity frequently co-occurs with psychiatric syndromes, resulting in substantial clinical, social, and economic burdens [

7]. Among the complex and bidirectional associations between obesity and mental health, regardless of the nature of these associations, the most prominent is its link between obesity and binge eating disorder (BED) [

8,

9,

10]. Consequently, a thorough assessment of the pathological eating behaviors in individuals with obesity is critical for effective clinical management.

Eating behaviors in individuals with obesity are heterogeneous and appear to be associated with varying outcomes [

11], which has drawn increasing clinical and research attention. Behaviors such as binge eating, [

12] grazing [

13,

14] night eating [

15], food addiction [

16], sweet eating [

17], and hyperphagia [

18] are among the most observed in this population and contribute significantly to the complexity of disordered eating. Notably, the study by Caroleo et al. [

19] highlighted the clinical relevance of differentiating these behaviors, as individuals with obesity can be phenotyped based on their specific eating patterns.

However, assessing these varied eating behaviors can be challenging in clinical settings. Currently available tools often require the use of multiple scales, each designed to evaluate a single behavior, and typically tailored to patients with eating disorders rather than those with obesity. This fragmented approach is time-consuming and may be difficult to interpret, especially for clinicians lacking specialized training in eating disorders. Therefore, there is a clear need for a comprehensive, reliable, and easy-to-use instrument to streamline the assessment of disordered eating behaviors in this population.

To address this need, Segura-García et al. [

20] developed and validated the Eating Behavior Assessment for Obesity (EBA-O), an 18-item questionnaire designed to assess the presence and severity of five key eating behaviors common in obesity (i.e., night eating, food addiction, sweet eating, hyperphagia, and binge eating). The EBA-O has demonstrated strong psychometric properties and is available in Italian [

20] and Greek [

21].

Despite its potential utility, a validated Spanish version of the EBA-O is lacking. This study aims to fill this gap by examining the psychometric properties of the Spanish adaptation of the EBA-O in a sample of overweight and obese individuals from the Spanish population.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

Between September and December 2023, we recruited participants through social media (e.g., Facebook, Instagram, and X of the primary researchers, MJJM, and AAM). We shared a survey link that explained the study’s aim, procedures, voluntary participation, utmost confidentiality, anonymity, and secure data handling.

The inclusion criteria were: men and women aged between 18 and 65 years; self-identifying Spanish as their primary language; body mass index (BMI) ≥25 kg/m2; willingness to participate and provision of valid consent. Participants were excluded in case of current diseases or treatments that could affect metabolic processes leading to weight gain or loss; women should not have been pregnant or breastfeeding for the last 12 months.

The survey gathered the tests mentioned below and collected socio-demographic variables such as education level, marital status, and employment status. It also recorded anthropometric measurements (i.e., self-reported weight and height) and general medical history (current and previous mental disorder or active treatment). Only fully completed questionnaires were included in the final analysis.

This study received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee for Human Research of the University of Córdoba (reference CEIH 23-23) and was conducted in accordance with the latest revision of the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Measures

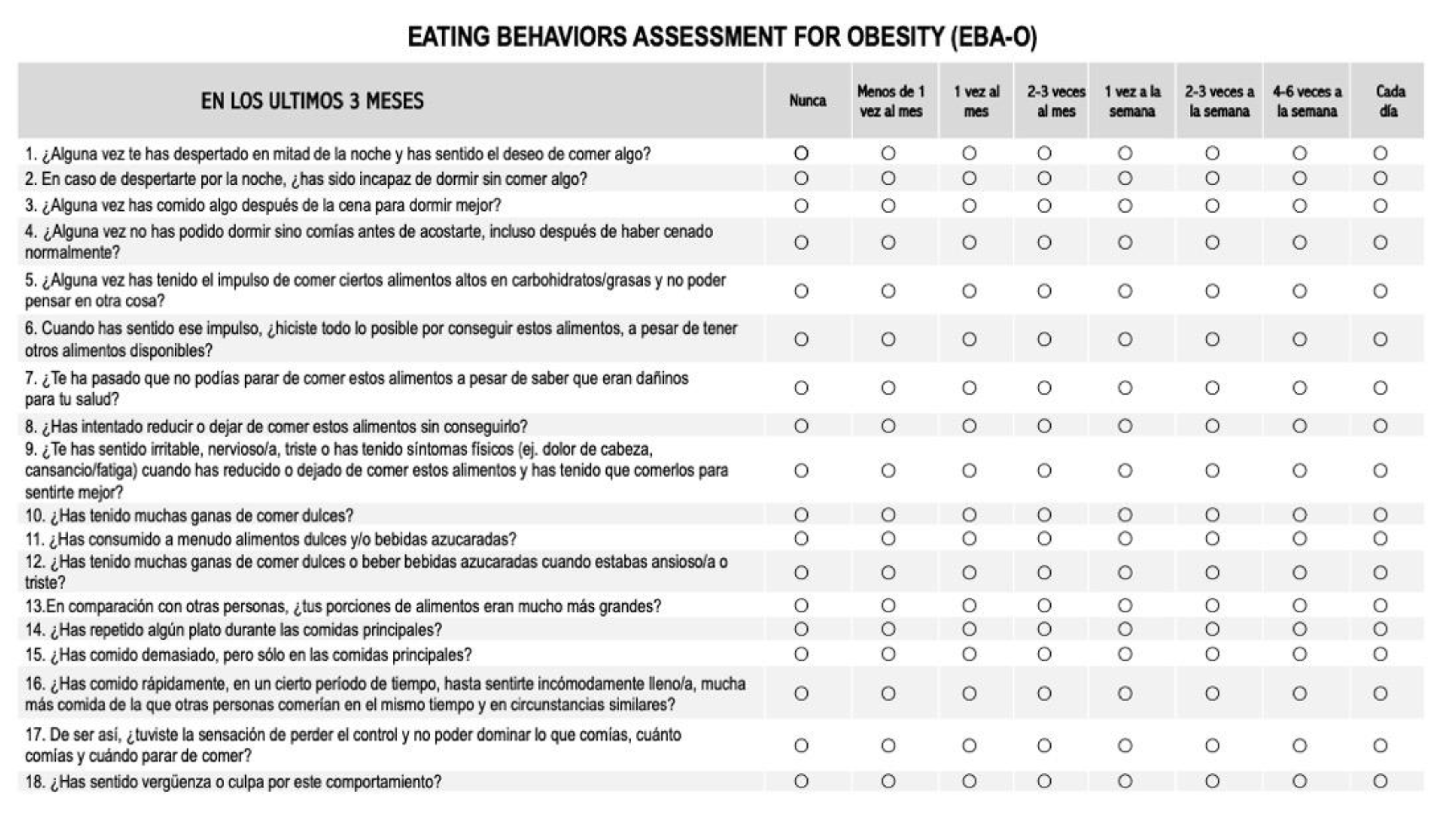

The Eating Behaviors Assessment for Obesity (EBA-O), originally developed and validated by Segura-García et al. [

20], underwent a double Italian/Spanish forward/backward translation process. Following an initial agreement among translators, a researcher blinded to the original version back translated the instrument into Italian to ensure accuracy. To evaluate comprehensibility, the preliminary Spanish version was administered online to a group of 15 volunteers from various Spanish-speaking countries (i.e., Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Spain). All raters considered the items clear and easy to understand, with only minor adjustments made to enhance cultural sensitivity across different Spanish-speaking populations. Legal authorization for translation and adaptation was obtained from the original author.

The EBA-O comprises 18 items rated on an 8-point Likert scale (rangin from 0 = never to 7 = every day) and is designed to assess the presence and severity of five pathological eating behaviors commonly associated with obesity (i.e., night eating, food addiction, sweet eating, hyperphagia, and binge eating) over the preceding three months (

Table 1).

To assess the convergent validity of the Spanish version of the EBA-O, participants completed the following validated questionnaires:

Binge Eating Scale (BES) [

22]: The BES is a 16-item self-report measure that assesses binge eating severity. Scores are interpreted as follows: <17 (unlikely), 17–27 (possible), and >27 (probable) risk of binge eating disorder. McDonald’s ω for the BES in this study was .88.

Yale Food Addiction Scale (YFAS) [

23]: The Spanish version of the YFAS 2.0 was used to assess addiction-like eating behavior over the past 12 months. This 35-item scale, scored on an 8-point Likert scale (0 = never to 7 = every day), measures 11 symptoms of food addiction. The YFAS 2.0 provides two scoring methods: (a) total number of criteria met (range: 0-11), and (b) severity level based on DSM-5 criteria for Substance Use Disorder (mild: 2-3 symptoms, moderate: 4-5 symptoms, severe: 6 or more symptoms). A “food addiction diagnosis” requires meeting at least two criteria plus experiencing impairment or distress. The Kuder–Richardson reliability coefficient for the YFAS 2.0 in this study was .87.

Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire (EDE-Q) [

24]: The EDE-Q is a 28-item self-report questionnaire that assesses eating disorder psychopathology over the past four weeks. It yields four subscale scores (restraint, eating concern, weight concern, and shape concern) and a total score. McDonald’s ω values for the EDE-Q subscales in this study were Restraint (.76), Eating Concern (.78), Weight Concern (.77), and Shape Concern (.84). The McDonald’s ω for the total score was .85.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

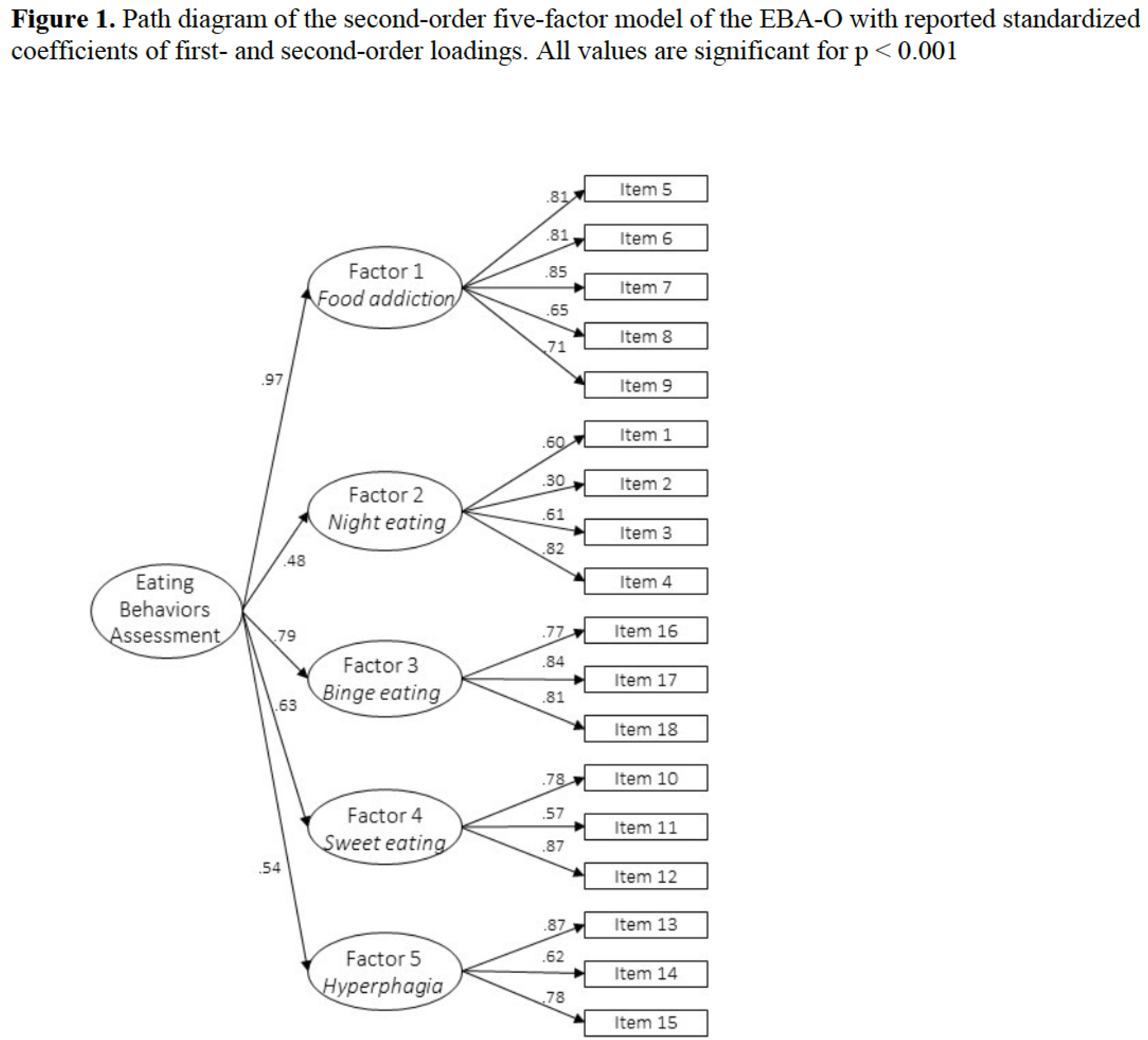

A second-order five-factor model was tested using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) with the open-source JASP software (version 0.18.3)[

25]. This analysis aimed to assess the underlying factor structure of the EBA-O and validate the suitability of a total score. The diagonally weighted least squares (DWLS) estimator, using a polychoric correlation matrix, was selected as it is the most appropriate method for modeling ordered data.

Several indices were used to evaluate the model fit: the relative chi-square (χ

2/df), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), comparative fit index (CFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). Adequate values were defined as TLI and CFI ≥ 0.90 (adequate) and ≥ 0.95 (very good), RMSEA ≤ 0.08 (adequate) and ≤ 0.05 (very good), and SRMR close to 0.08. Additionally, a good fit was indicated by χ

2/df values < 3.0, and a very good fit by values < 2.0, following the guidelines proposed by Hu and Bentler [

26].

To establish construct validity, correlations between the EBA-O factors and respective questionnaires were examined, emphasizing correlation coefficients (r) greater than 0.30, as recommended benchmarks.

A two-way multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) with the five factor of the EBA-O as dependent variables, and sex and BMI category as independent factors, was carried out. Eta-squared (η2) was used to measure the effect size of MANOVA, considering values of 0.01, 0.06, and 0.14 as indicating small, medium, and large effects, respectively. The Bonferroni correction was used to correct for multiple comparisons (p = 0.05/10 = 0.005).

3. Results

After excluding participants who did not meet all inclusion and exclusion criteria, a final sample of 384 participants (154 men, 40.1%; 230 women, 59.9%) was analysed.

Table 2 summarises the characteristics of this sample.

3.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

The confirmatory factor analysis demonstrated excellent fit indices: CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.03, relative chi-square (χ

2/df) =1.21, p = 0.002 supporting the tested second-order five-factor of the Spanish version of the EBA-O model (

Figure 1).

3.2. Internal Consistency.

The internal consistency for the EBA-O total score, as assessed by McDonald’s ω coefficient, was high (ω = .80), indicating excellent reliability of the Spanish version. McDonald’s ω for all factors indicated good reliability: food addiction (ω = .88), night eating (ω = .65), binge eating (ω = .83), sweet eating (ω = .79), and hyperphagia (ω = .82). The factors were highly correlated, with the highest correlation observed between factors 1 and 3, and the lowest between factors 4 and 5 (

Table 3).

3.3. Concurrent Validity

Correlation analysis (

Table 4) revealed significant correlations between the EBA-O subscales and the BES (from r = .401 to .713), YFAS (from r = .342 to .730), and EDE-Q total score (from r = .285 to .699).

3.4. Two-way MANOVA

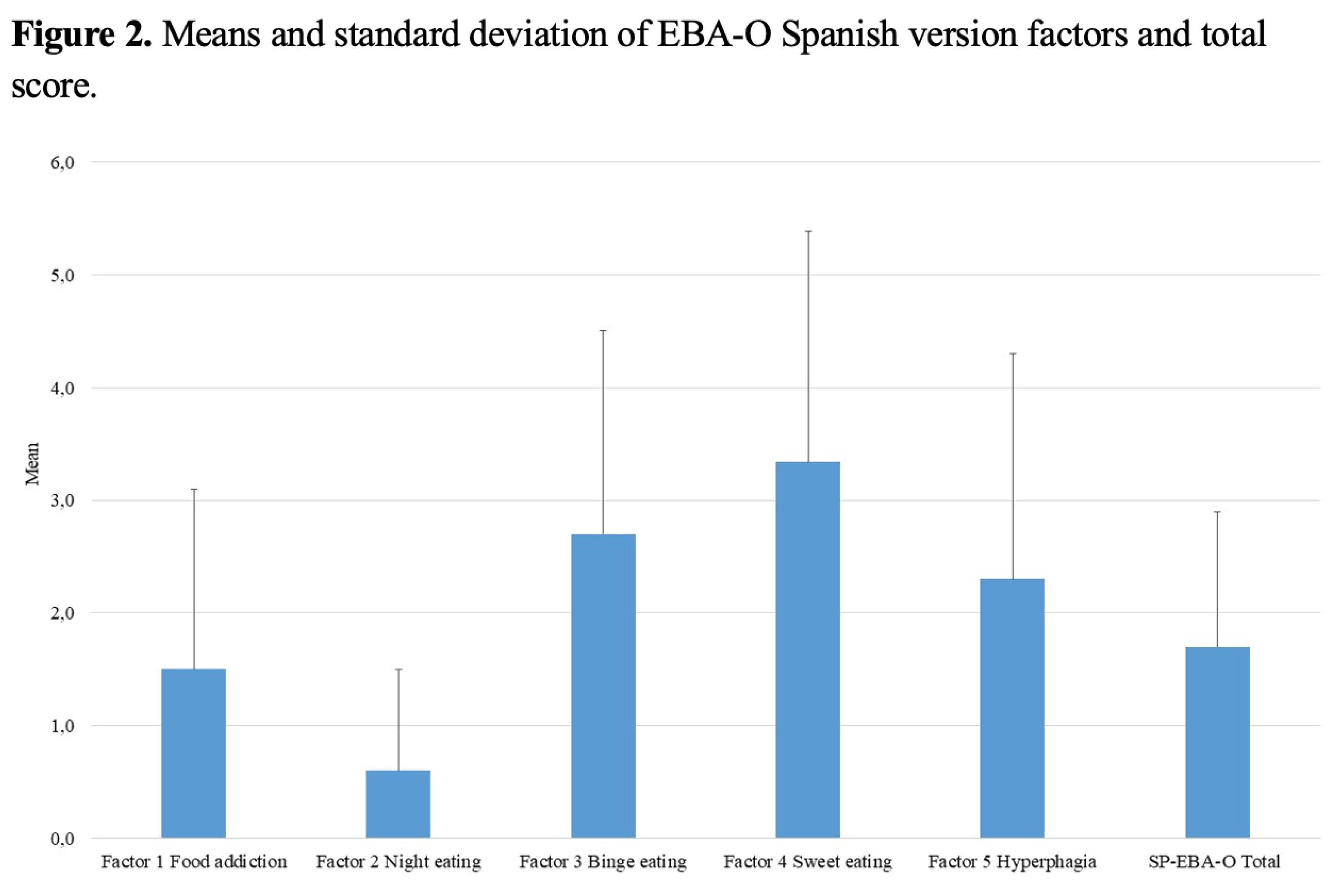

Significant differences in EBA-O subscales were observed based on sex (F = 3.559, p = .005; Wilk’s lambda = 0.881; η

2 = .12), BMI category (F = 3.191, p < .001; Wilk’s lambda = 0.712; η

2 = .11), and their interaction (F = 2.510, p = .002; Wilk’s lambda = 0.763; η

2 = .09). Sex significantly affected the night eating subscale (F = 12.523, p = .001; η

2 = .08). Similarly, categorical BMI significantly influenced both food addiction (F = 5.300, p = .002; η

2 = .11) and night eating (F = 12.685, p < .001; η

2 = .22) subscales. The means and standard deviations of EBA-O factors and the total score are presented in

Figure 2.

4. Discussion

Obesity is a major public health concern due to its high prevalence and its contribution to increased morbidity and mortality. Accurately identifying and characterizing eating behaviors is essential for the development of effective, individualized therapeutic interventions. To our knowledge, this is the first study to validate an instrument designed to comprehensively assess eating behaviors in individuals with overweight or obesity from a native Spanish-speaking population. The present research focused on the validation and factorial structure of the Spanish version of the Eating Behavior Assessment for Obesity (EBA-O) in a sample of Spanish adults with overweight or obesity.

Our findings demonstrate that the Spanish version of the EBA-O is a valid and reliable instrument comparable to the original Italian version. Confirmatory factor analysis supported a second-order five-factor model, consistent with previous validations. The internal consistency of the instrument was strong, with global McDonald’s ω coefficient = .80; ranging from .65 to .88 for the subscales. These results are in line with those reported by Segura-García et al. and Mavrandrea et al., affirming the clinical utility of the EBA-O in Spanish-speaking populations [

20,

21].

The Spanish version of the EBA-O also showed satisfactory convergent validity, showing as evidenced by positive and significant correlations with established measures of pathological eating behavior, including the BES, the YFAS, and the EDE-Q. These findings further support the instrument’s appropriateness for assessing eating behaviors in this population.

The two-way MANOVA revealed significant differences in EBA-O subscale scores according to sex and BMI categories. Specifically, sex significantly influenced the night eating subscale (F = 12.523, p = .001, η² = .08), with women reporting higher scores than men. Some studies have reported sex differences in night eating patterns [

27], whereas others found no consistent differences or suggested that these differences may not be stable over time [

28]. Very recently Oteri et al. [

29] observed that while the average scores of night eating were significantly higher among males, females exhibited a higher prevalence of night eating (i.e., night eating score ≥ 4). Additionally, the BMI categories significantly influenced both food addiction (F = 5.300, p = .002, η² = .11) and night eating (F = 12.685, p < .001, η² = .22) subscales, with higher BMI categories associated with higher scores on both measures. Oteri et al. [

29] found that a higher BMI is associated with greater severity of altered eating behaviors, especially food addiction and binge eating, while hyperphagia is related to slower weight loss during inpatient stay. In our study, the interaction between sex and BMI was also significant (F = 2.510, p = .002, η² = .09), suggesting that these factors may jointly influence eating behaviors. As such interactions effects have not been consistently reported in previous research [

20,

21], further studies with larger and more diverse samples are warranted to clarify these relationships.

This study presents several strengths, such as the use of a rigorous back-translation methodology and the inclusion of participants from diverse Spanish-speaking backgrounds to ensure both linguistic and conceptual comprehensibility. Nevertheless, certain limitations should be acknowledged. The reliance on self-reported data collected through an online questionnaire may introduce bias, and the absence of a retest assessment limits the evaluation of the temporal stability of the Spanish version of the EBA-O scores. Additionally, future research should evaluate the ability of the Spanish EBA-O to effectively capture and differentiate changes in eating behavior within clinical populations, as demonstrated by previous studies that highlight its efficacy [

30,

31].

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the Spanish version of the EBA-O is a valid and reliable tool for assessing disordered eating behaviors in Spanish-speaking individuals with overweight or obesity. Its robust psychometric characteristics support its use in both clinical and research contexts. By providing a comprehensive and easy-to-use measure, the EBA-O can assist clinicians in identifying maladaptative eating patterns and tailoring interventions more effectively for this population.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, MJJ, CGS and MA.; methodology, M.A software, EAC, CCR, AJP; validation, MJJ, CSG, AA, FS, MR and EAC; formal analysis, MR, CCR, AJP; investigation, CSG, MMD, MJMD, FS, CSG, AA, EA, ; resources, AAM, MJJ, CSG.; data curation, MJJ, MA, AA,; writing—original draft preparation, MA, AA, AJP; writing—review and editing, CSG, FS, MJJ, MJM, MA, AJP, AA.; visualization, EAC, MR, MMD; supervision, MA, MJ, FS, CSG, MJM. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The investigation was approved by the Ethics Committee for Human Research of the University of Córdoba (reference CEIH 23-23) and conducted in accordance with the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Availability of data and materials: Data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

We thank all participants who agreed to participate in our study.

Conflicts of Interest

All other authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interests related with this manuscript.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BED |

Binge eating disorder |

| BES |

Binge Eating Scale |

| BMI |

Body Mass Index |

| CFA |

Confirmatory factor analysis |

| DSM-5 |

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition |

| DWLS |

diagonally weighted least squares |

| EBA-O |

Eating Behaviors Assessment for Obesity |

| EDE-Q |

Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire |

| ICD-11 |

International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision |

| MANOVA |

multivariate analysis of variance |

| YFAS |

Yale Food Addiction Scale |

References

- C. J. L. Murray et al., “Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019,” The Lancet, vol. 396, no. 10258, pp. 1223–1249, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Okunogbe, R. Nugent, G. Spencer, J. Powis, J. Ralston, and J. Wilding, “Economic impacts of overweight and obesity: current and future estimates for 161 countries,” BMJ Glob Health, vol. 7, no. 9, Sep. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Lancet Gastroenterology Hepatology, “Obesity: another ongoing pandemic.,” Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol, vol. 6, no. 6, p. 411, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. M. Perdomo, R. V. Cohen, P. Sumithran, K. Clément, and G. Frühbeck, “Contemporary medical, device, and surgical therapies for obesity in adults,” Apr. 01, 2023, Elsevier B.V. [CrossRef]

- P. Association, “DSM-5: Manual diagnóstico y estadístico de los trastornos mentales,” 2014.

- “World Health Organization. (2022). ICD-11: International classification of diseases (11th revision). https://icd.who.int/.

- M. D. Marcus and J. E. Wildes, “Obesity: Is it a mental disorder?,” Dec. 2009. [CrossRef]

- C. Segura-Garcia et al., “Binge Eating Disorder and Bipolar Spectrum disorders in obesity: Psychopathological and eating behaviors differences according to comorbidities,” J Affect Disord, vol. 208, pp. 424–430, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Aloi et al., “Metacognition and emotion regulation as treatment targets in binge eating disorder: a network analysis study,” J Eat Disord, vol. 9, no. 1, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- E. A. Carbone et al., “The relationship of food addiction with binge eating disorder and obesity: A network analysis study,” Appetite, vol. 190, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Rania et al., “Reactive hypoglycemia in binge eating disorder, food addiction, and the comorbid phenotype: unravelling the metabolic drive to disordered eating behaviours,” J Eat Disord, vol. 11, no. 1, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. C. Berg et al., “Relationship between daily affect and overeating-only, loss of control eating-only, and binge eating episodes in obese adults,” Psychiatry Res, vol. 215, no. 1, pp. 185–191, Jan. 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Parsons and J. P. Clemens, “Eating disorders among bariatric surgery patients: The chicken or the egg?,” Nov. 01, 2023, Wolters Kluwer Health. [CrossRef]

- E. M. Conceição, J. E. Mitchell, S. G. Engel, P. P. P. Machado, K. Lancaster, and S. A. Wonderlich, “What is ‘grazing’? Reviewing its definition, frequency, clinical characteristics, and impact on bariatric surgery outcomes, and proposing a standardized definition,” Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases, vol. 10, no. 5, pp. 973–982. 2014. [CrossRef]

- V. Moizé, M. E. Gluck, F. Torres, A. Andreu, J. Vidal, and K. Allison, “Transcultural adaptation of the Night Eating Questionnaire (NEQ) for its use in the Spanish population,” Eat Behav, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 260–263, Aug. 2012. [CrossRef]

- E. Kalon, J. Y. Hong, C. Tobin, and T. Schulte, “Psychological and Neurobiological Correlates of Food Addiction,” in International Review of Neurobiology, vol. 129, Academic Press Inc., 2016, pp. 85–110. [CrossRef]

- M. Van Den Heuvel, R. Hörchner, A. Wijtsma, N. Bourhim, D. Willemsen, and E. M. H. Mathus-Vliegen, “Sweet eating: A definition and the development of the dutch sweet eating questionnaire,” Obes Surg, vol. 21, no. 6, pp. 714–721, Jun. 2011. [CrossRef]

- S. B. Heymsfield et al., “Hyperphagia: current concepts and future directions proceedings of the 2nd international conference on hyperphagia.,” in Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. Caroleo et al., “A real world study on the genetic, cognitive and psychopathological differences of obese patients clustered according to eating behaviours,” European Psychiatry, vol. 48, pp. 58–64, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- C. Segura-Garcia et al., “Development, validation and clinical use of the Eating Behaviors Assessment for Obesity (EBA-O),” Eating and Weight Disorders, vol. 27, no. 6, pp. 2143–2154, 2022. [CrossRef]

- P. Mavrandrea, M. Aloi, M. Geraci, A. Savva, F. Gonidakis, and C. Segura-Garcia, “Validation and assessment of psychometric properties of the Greek Eating Behaviors Assessment for Obesity (GR-EBA-O),” Eating and Weight Disorders, vol. 29, no. 1, 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. Escrivá-Martínez, L. Galiana, M. Rodríguez-Arias, and R. M. Baños, “The binge eating scale: Structural equation competitive models, invariance measurement between sexes, and relationships with food addiction, impulsivity, binge drinking, and body mass index,” Front Psychol, vol. 10, no. MAR. 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. Granero et al., “Validation of the Spanish version of the Yale Food Addiction Scale 2.0 (YFAS 2.0) and clinical correlates in a sample of eating disorder, gambling disorder, and healthy control participants,” Front Psychiatry, vol. 9, no. MAY, May 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Villarroel, E. Penelo, M. Portell, and R. M. Raich, “Screening for eating disorders in undergraduate women: Norms and validity of the spanish version of the eating disorder examination questionnaire (EDE-Q),” J Psychopathol Behav Assess, vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 121–128, Mar. 2011. [CrossRef]

- JASP Team (2024), “JASP (Version 0.18.3). University of Amsterdam. ”.

- L. Hu and P. M. Bentler, “Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives,” Struct Equ Modeling, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 1–55, 1999.

- R. H. Striegel-Moore, D. L. Franko, D. Thompson, S. Affenito, and H. C. Kraemer, “Night eating: Prevalence and demographic correlates,” Obesity, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 139–147, Jan. 2006. [CrossRef]

- J. Kaur, A. B. Dang, J. Gan, Z. An, and I. Krug, “Night Eating Syndrome in Patients With Obesity and Binge Eating Disorder: A Systematic Review,” Jan. 05, 2022, Frontiers Media S.A. [CrossRef]

- V. Oteri et al., “Clinical Assessment of Altered Eating Behaviors in People with Obesity Using the EBA-O Questionnaire,” Nutrients, vol. 17, no. 7, p. 1209, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- E. Colonnello et al., “Eating behavior patterns, metabolic parameters and circulating oxytocin levels in patients with obesity: an exploratory study,” Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, vol. 30, no. 1, p. 6, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- E. A. Carbone et al., “The Greater the Number of Altered Eating Behaviors in Obesity, the More Severe the Psychopathology,” Nutrients, vol. 16, no. 24, p. 4378, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).