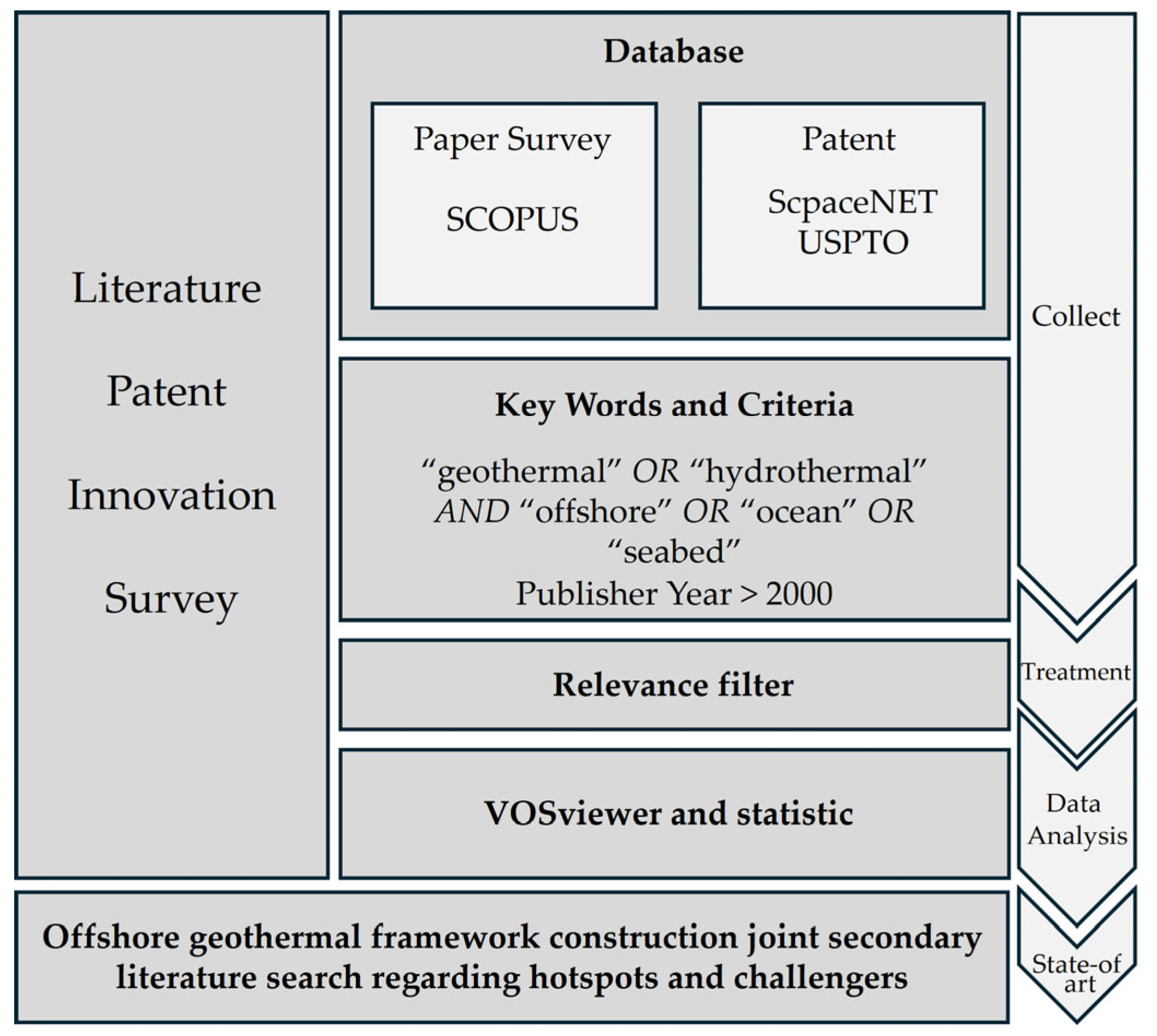

1. Introduction

Over the past few decades, the global adoption of low-carbon energy has grown significantly [

1,

2]. Among the various low-carbon energy sources, geothermal resources stand out great potential worldwide as a reliable, and efficient option for heat and electricity generation. Geothermal energy is derived from the Earth's internal thermal energy, which can reach temperatures between 90 to over 200 °C [

3]. Despite its proven benefits and potential, geothermal energy has often been overshadowed by other renewable sources like solar and wind, which are weather dependent. Nevertheless, it is poised to play a pivotal role in the global transition to sustainable energy systems, complementing other renewable energy technologies [

1].

On ground geothermal technology and estimation resources are well-established and have more than one century of development. Expanding exploitation of offshore geothermal resources, particularly in offshore volcanic and production hot water of petroleum fields, remains a challenge and represents a new frontier in renewable energy development [

4]. Offshore geothermal energy, traditionally overlooked as a viable energy source, is gaining traction due to rising energy prices, solutions to deal with offshore petroleum decommissioning infrastructure and advancements in technology [

5] and has gained significant attention in the energy industry over the past decade as a promising renewable energy [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. These untapped potential marine resources could present competitive opportunities for companies with expertise in subsurface and offshore operations looking for expanding renewables businesses attending greenhouse gases mitigation. Hence, offshore geothermal represents a new emerging exploration frontier in renewable energy towards ocean [

5,

10].

In the context of climate crisis and energy demand, limiting the consequences of human-induced global warming requires, among other strategies, actions for reducing greenhouse gas emissions through transitioning to renewable energy sources, improving energy efficiency, and implementing sustainable land management practices [

11]. This must be balanced with increasing energy demand and population growth, thus harnessing the vast potential of geothermal ocean resources can contribute to meeting energy needs while reducing dependence on fossil fuels, thereby addressing environmental concerns. Actually, at COP28 in 2023, 195 signatories’ countries reached a landmark agreement indicating a gradual shift away from fossil fuels and towards renewable energy sources. The accord emphasizes the crucial need to accelerate climate action, one point out was triple global renewable energy capacity and double the global average annual rate of energy efficiency improvements by the year 2030. This agreement marks a significant, albeit non-binding, step towards achieving global climate goals [

12]. Following the same climate change solutions, COP29 proposal endorsed the renewables energy launching the Global Energy Storage and Grids Pledge and Energy Storage Pledge [

13].

The IPCC 6th Assessment Report (AR6) compiled global energy transition scenarios, performed by Integrated Assessment Model (IAM). On that geothermal energy is among the renewable energy alternatives capable of mitigating greenhouse gas emissions by 2030. It has the potential to contribute to the reduction of greenhouse gases by up to 1.0 GtCO

2-eq year

-1, with costs ranging around

$50-100 per tCO

2-eq year

-1, making it one of affordable renewable energy sources [

11]. Likewise, according to IRENA, geothermal energy “can and should play a greater role in meeting global energy needs”, counteracting climate changes and moving towards a green energy economy, for both electricity and heating and cooling [

1]. According to World Bank, the average CO

2 emission by geothermal power plants worldwide is 122 gCO

2-eqkWh

-1, which is from natural plutonic Earth gases, and not related to combustion [

14]. When analyzing project life cycle emissions, estimates for different energy sources vary significantly. For general geothermal projects life cycle emissions range from 11 to 78 gCO

2-eqkWh

-1. In comparison, solar photovoltaic (PV) systems exhibit a broader range, from 9 to 300 gCO

2-eqkWh

-1 and onshore wind between 8 and 124 gCO

2-eqkWh

-1 [

15].

Another geothermal energy characteristic is that it holds an unconventional advantage as it offers low carbon both heat and electric power generation capabilities, along with the potential for making a variety of cascading uses such as direct hot water (steam), cold generation (e.g. through absorption cycles) and electricity. In addition, more recently, a diverse array of innovations has been developed for thermal energy like subsurface storage combined or not with CO

2 capture and critical mineral brine water mining [

16].

Despite being a resource still in the process of being widely explored, geothermal energy exploitation has an ancient history, beginning with its direct use for bathing and cooking for civilizations like Romans, New Zealanders and Turks. This evolved into indirect applications for mechanical power in mining, and ultimately for electricity generation at the end of XIX century [

3]. The first successful generation of electricity from geothermal energy took place in Italy in 1904, marking a significant milestone in renewable energy sources. This was followed in 1913 by the establishment of Larderello Power Plant, the world's first commercial geothermal power plant, which had a capacity of 250 kilowatts (kW) and supplied electricity to the local railway system and nearby villages [

17].

Geothermal onshore power plants are renowned for their high capacity factors, which significantly surpass those of many other renewable energy sources. Over the past decade, the global geothermal fleet has demonstrated notable capacity factors, averaging between 70% and 80%, being able to reach up to 95% [

18,

19,

20]. Moreover, the capacity factor is highly constant over the years, as historically reported by geothermal output from United States plants [

21]. In fact, certain countries have reported national averages exceeding 90% during specific years, with notable examples including New Zealand, Iceland, Italy, and Ethiopia, where geothermal resources are particularly abundant and effectively harnessed [

19]. In Chile the capacity factor of the first country’s geothermal power plant reaches 84% [

20]. In New Zealand, geothermal energy surpassed natural gas as a source of electricity in 2014, becoming the second-largest contributor to the country's electricity generation. Only hydropower exceeds geothermal energy in providing a reliable and sustainable energy supply [

22].

This remarkable performance is largely due to the inherent geological characteristics of geothermal energy, which allows for continuous heat flux and reliable electricity generation, unlike intermittent sources such as solar photovoltaic systems, which typically operate at capacity factors of only 10-15% or wind onshore with 25-40% [

2,

19]. When comparing energy output, a typical geothermal power plant can generate five to six times more energy than a solar PV installation of equivalent capacity [

19].

While coal and combined-cycle natural gas power plants can achieve similar capacity factors to geothermal facilities, their global averages tend to be lower, around 60% and 50% respectively, because these fossil fuel plants often adjust their output in response to daily or seasonal demand fluctuations and the variability of renewable energy generation [

2,

19]. A typical geothermal power plant is highly flexible in its operation, capable of adjusting its output multiple times per day. It can ramp its power generation from as low as 10% to 100% of its normal capacity, making it a reliable option for balancing energy supply and demand [

23]. Consequently, onshore geothermal power plants stand out as a source of dispatchable renewable electricity, providing a baseload energy supply that can complement and integrate the energy supply expansion of variable energy sources like solar and wind into the broader energy grid [

19,

24].

Conventional use of geothermal energy contributed with 5 exajoules to the global primary energy supply in 2023, representing a 0.8% of overall demand, including as direct uses as heat and cooling. Modern bioenergy currently fulfills approximately 7% of global primary energy demand, exceeding the contributions of hydropower, wind, and solar power, which individually account for between 1.0% to 2.,2%. Thus, geothermal energy remains the fourth least-utilized renewable energy source [

25].

In 2025, approximately 296 geothermal power plants are running worldwide harnessing the Earth's internal heat to generate electricity [

26,

27,

28]. These plants are typically operating in regions characterized by high geothermal gradients, often located within sedimentary basins or volcanic arcs, where geologic activity facilitates access to high geothermal gradient resources.

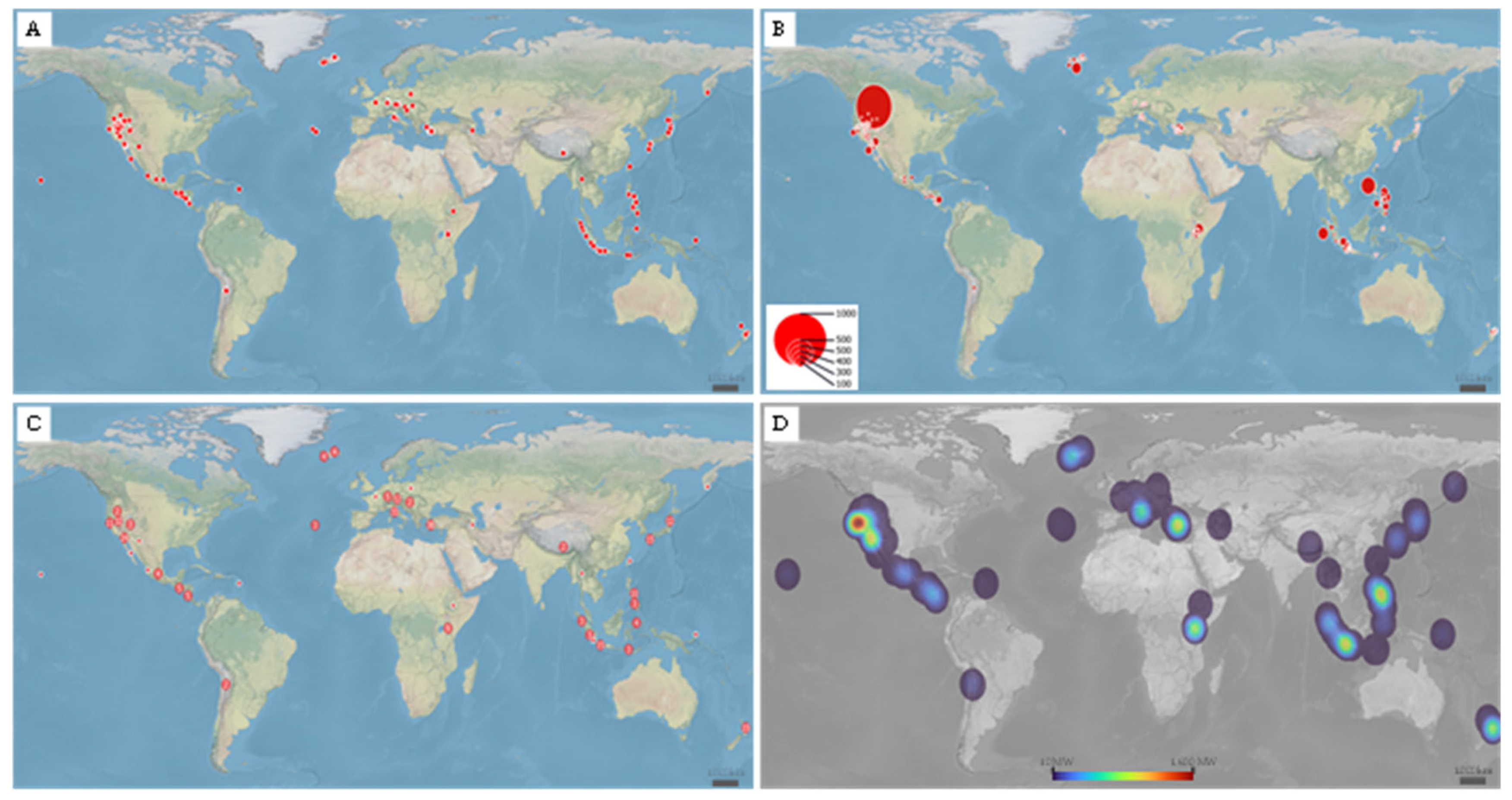

The global map distribution of these facilities reveals a notable concentration in the West of United States, Europe, and Asia, as depicted in

Figure 1. Notably, when examining installed capacity, the United States stands out as a leader in geothermal energy production, joined by regions in Asia and Eastern Europe. The five largest geothermal facilities in terms of installed capacity are situated across diverse counties. The United States boasts the most significant facility, The Big Geysers, with 1,163 MW. Following this is the Makban plant in the Philippines, with a capacity of 458 MW. Indonesia's Surulla facility ranks third at 330 MW, while Iceland's Hellisheidi comes next with a capacity of 303 MW. Lastly, Kenya's Olkaria I rounds out the list with 278 MW. These facilities exemplify the global spread for geothermal energy harnessing, sited in distinct countries and continents. In South America, there are currently two operational power plants, one in Chile and another in Bolivia [

29,

30]. In contrast, Africa boasts a total of ten operational power plants, reflecting the continent's approach to energy development [

26,

27,

28].

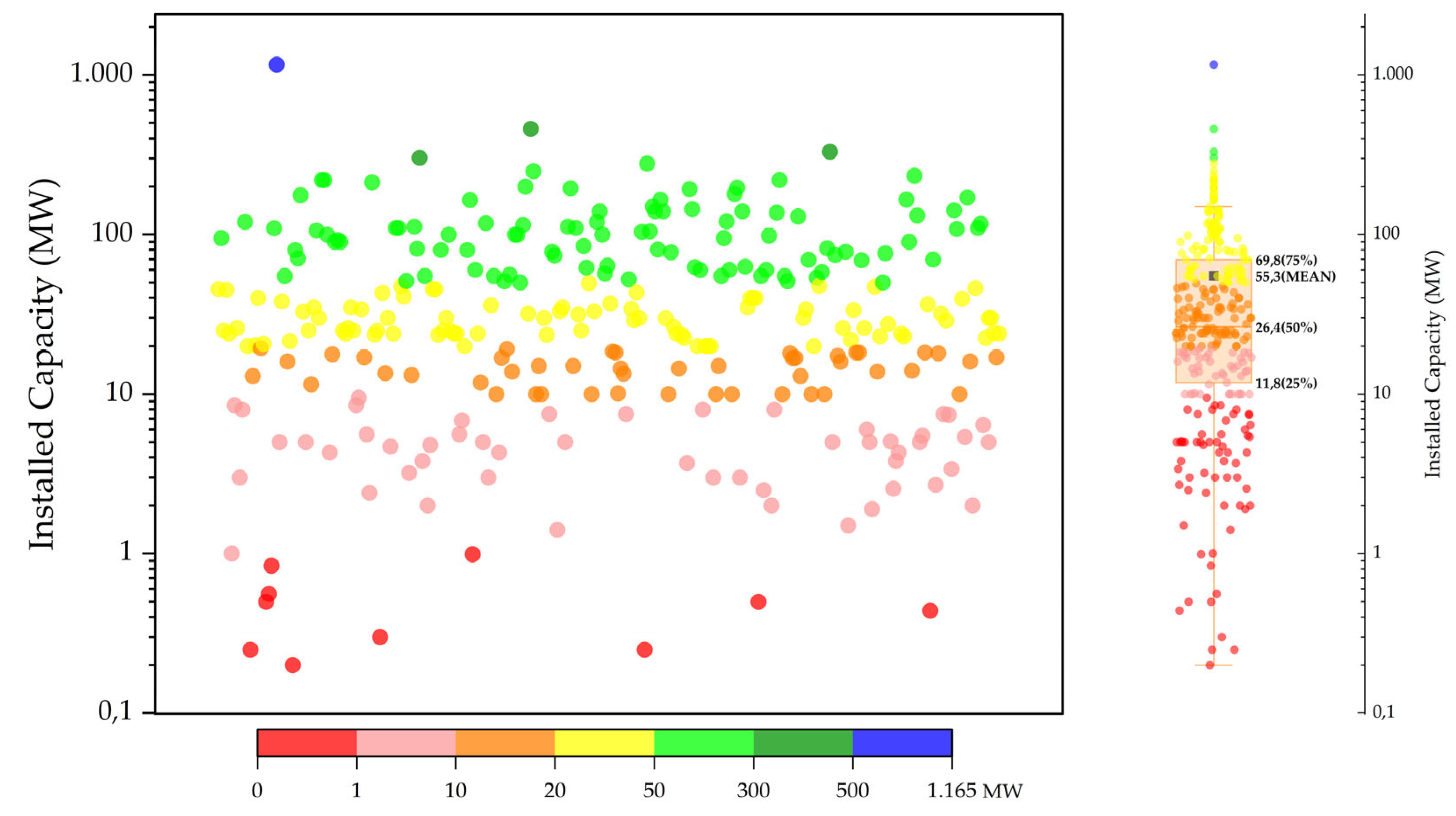

Following the analysis of geothermal power plants in operation in the world, according to the geothermal power plant database [

26,

27,

28], the global landscape of geothermal energy installed capacity displays considerable variation across its 296 operational plants (

Figure 2). When statistically analyzing the installed capacity distribution worldwide, a significant dispersion is observed, ranging from as low as around 1 MW to as high as 1.1 GW (

Figure 2). Despite this wide range, the statistical distribution is relatively narrow in terms of central tendency, most of them are under 100 MW. The average capacity is around 55 MW. The P

25 sits at approximately 12 MW, while the P

75 is around 70 MW, indicating that half of the geothermal plants globally have installed capacities between these two values. This statistical insight, shown in

Figure 2, suggests that, despite the presence of outliers with very high capacities, most geothermal facilities typically operate within a 12-70 MW capacity range.

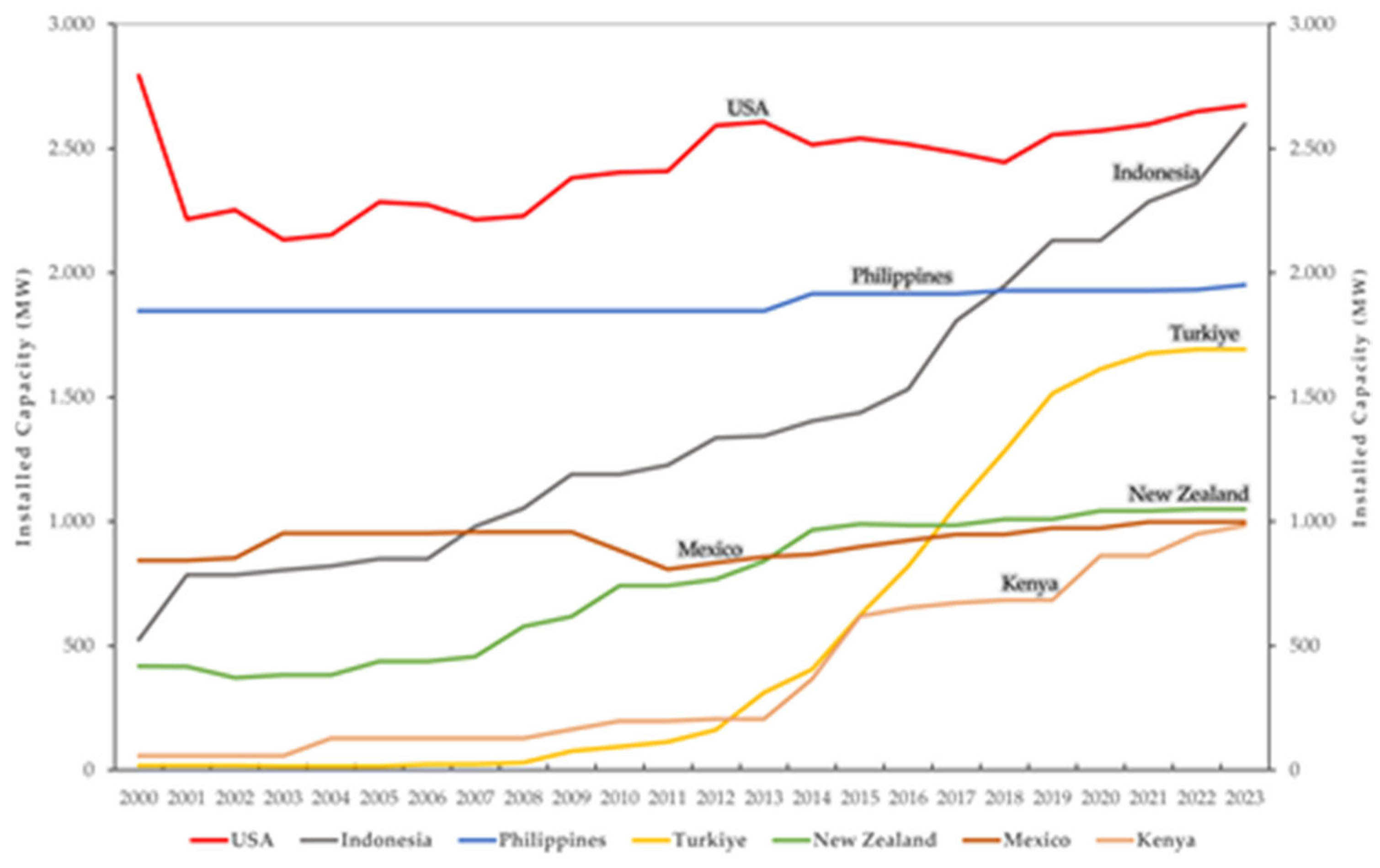

When analyzing the growth evolution from top 7 countries (United States, Indonesia, Philippines, Turkey, New Zealand, Mexico and Kenya) depicted in

Figure 3, based on IRENA statistical data set [

32], the United States leads 2023 the global rankings in total installed geothermal capacity, showing 2,673 MW. This leadership is supported by a well-established infrastructure, with operational plants dating back to the 1960s, reflecting consistent growth over the decades [

33]. Significant milestones in the United States geothermal capacity evolution include increments peaks in 1983, 2012 and 2018 [

33].

Indonesia ranks second, with an installed capacity of 2,567 MW, showcasing remarkable growth due to its substantial geothermal resources, attributed to its tectonically active region. Indonesia made significant progress along this period, with crescent and consistent increase, in 2017 added 275 MW, cementing its status as an emerging leader in the geothermal sector [

34]. The Philippines, with an installed capacity of 1,952 MW, experienced substantial growth during the 1980s, with production peaks of 692.53 MW in 1979 and 324.5 MW in 1983. However, since the 1990s, the growth rate has stagnated, with minimal additions in recent years [

35]. Turkey, with a capacity of 1,696.46 MW, has made notable strides in expanding its geothermal production, particularly after 2012. The year 2017 marked a significant achievement, with an addition of 343 MW, reflecting the country’s investments in technology and infrastructure to harness its geothermal resources as part of long-term strategy and action plans to accelerate emissions mitigation [

36]. Finally, New Zealand, with an installed capacity of 1,050 MW, is a pioneer in geothermal energy utilization and double the installed capacity over the past 23 years [

22].

However, while geothermal energy is a proven and reliable baseload resource on land, expanding the harness of geothermal resource towards offshore has often face challenges related to subsurface geological complexity, offshore operational environment, top side equipment and costs [

37]. Offshore geothermal energy may represent a largely untapped energy resource with the potential to enhance energy sustainability and deal with well-established marine petroleum infrastructure [

38]. By harnessing heat from subsurface of the ocean, it offers a consistent and reliable energy supply, complementing intermittent sources like wind or solar. Geothermal could also be exploited in abandoned petroleum fields, in a brownfield project, repurposing and taking advantage of nearly oil and gas infrastructure decommission. On the other hand, it could be a greenfield project, exploring high geothermal gradients areas such as submarines volcanoes [

39].

Offshore geothermal energy represents an emerging renewable source distinct from conventional onshore geothermal exploitation, offering novel opportunities for industries experienced in offshore operations. Majors oil and gas companies that have offshore experience, along with oil and gas services companies, are well-positioned to leverage existing offshore data sets like seismic, gravimetry, magnetotelluric, petroleum wells completions, subsurface technologies, top side infrastructure, operational expertise, and technological capabilities to address the unique challenges of harnessing geothermal energy in marine environments [

37]. Although there is none offshore geothermal plant operating in the world, advanced research and pilot projects have begun in countries such as Italy, Iceland, Azores, Indonesia, Norway, and United States.

Therefore, this paper aims to provide a comprehensive review and brings to light hotspots and challenges for the emerging opportunities of geothermal resources sited in the offshore ambient in a global perspective. Such analysis is original, due to the scarce scientific literature on the subject, and particularly relevant for energy businesses companies considering expanding and diversifying their portfolio. It is also worthwhile for policymakers aiming at developing proper regulatory frameworks for this emerging way to harness geothermal resources. Furthermore, several offshore oil and gas facilities are approaching to begin their decommissioning process. Therefore, repurposing these infrastructures for geothermal energy could represent an alternative solution for greenhouse gas emission mitigation and electricity and heat (cold) supply.

4. Offshore Geothermal Opportunities

Thousands of petroleum wells have been drilled in regions such as the North Sea Basin, the Gulf of Mexico, East Africa, and Brazil, many of which are now approaching the stage of abandonment [

5,

9,

75]. A significant number of these wells produce more hot water than hydrocarbons, revealing an untapped potential for geothermal energy. Essentially, the existing infrastructure represents a nearly complete geothermal system, with the primary missing component being the installation of power plants on top petroleum infrastructure. Although there are currently no operational offshore geothermal power plants, numerous projects and pilot studies have been developed over the years to explore the feasibility of converting or co-generating these wells into sustainable sources of geothermal energy.

In 1998, Norway explored the possibility of producing electricity from geothermal energy at the Ula Field in the Norwegian North Sea, located at a water depth of 70 meters[

75,

76]. The field, discovered in 1976 and commencing production in 1986, primarily produces oil from sandstone formations in the Upper Jurassic Ula Formation, with the reservoir situated at a depth of 3,345 meters. Additionally, production occurs from parts of the underlying Triassic reservoir at around 3,450 meters depth. The Ula Field produces approximately 800 m

3 of water at 130 °C daily, offering a geothermal potential estimated at 10 MW[

75,

76] . This initiative marked Norway as a pioneer in offshore geothermal feasibility studies. However, with production currently in its late life phase and challenges in gas supply for water alternating gas (WAG) injection, the operator plans to cease production by 2028. In January 2025, the field produced 4,000 barrels of oil equivalent per day compared to 17,000 barrels of water per day [

77]. This indicates a notable production ratio where oil output is significantly lower than water production, which is common in mature fields undergoing water flooding. Despite the recognized geothermal potential, there have been no developments or implementation of geothermal energy reuse reported for the Ula Field to date.

Another field that has estimated geothermal potential is Ekofisk, whose production compose the well-known Brent blend benchmark. The field is located in the Norwegian North Sea at a water depth of approximately 70 meters, is another site identified for its geothermal potential. Discovered in 1969, the initiated test production in 1971, followed by regular oil production starting in 1972. Ekofisk produces oil primarily from naturally fractured chalk reservoirs, specifically the Late Cretaceous Tor Formation and the early Paleocene Ekofisk Formation [

78]. Preliminary assessments by Turboden have estimated that the field could generate around 7 MW of geothermal electricity applying ORC binary power plant. This estimate is based on a water flow rate of 444 l/s at a temperature of 110°C, highlighting Ekofisk’s potential as a source for low-carbon energy production alongside its ongoing oil extraction activities [

75]. At the same stage, Kristin Field is in the tail phase of oil production. With water production at 160 °C, it was estimated at least 1 MW gross generation from thermal water [

75].

In addition to those offshore fields, there are 14 other mature offshore fields in the Norwegian North Sea with production water temperatures exceeding 84°C that have the potential to produce geothermal energy using existing infrastructure (

Table 2). These fields could be utilized for geothermal energy extraction without the need to deepen the wells, making it a technically feasible option with additional retrofit. Furthermore, if these pre-existing wells were deepened, the amount of geothermal energy generated could increase significantly due to the relatively high geothermal gradient of approximately 50°C/km in the region. This gradient indicates that deeper wells could access even hotter water, thereby enhancing the efficiency and output of geothermal energy production from these offshore sites [

75]. The transition from hydrocarbon extraction to geothermal energy production represents a significant shift in the energy landscape, particularly in places like the North Sea. As mature oil and gas fields approach the end of their productive life, innovative approaches are being explored to repurpose existing infrastructure for geothermal energy development. This strategy not only addresses the challenges of energy transition but also leverages the North Sea's established assets to support a low-carbon future, ensuring a more sustainable and efficient use of resources [

79]. Beyond the Norwegian part of then the North Sea, United Kingdom portion areas also exhibit a geothermal gradient exceeding 50°C/km. Notably, the Elgin and Franklin fields have production water temperatures reaching 196°C [

80].

The temperature gradient in the North Sea has been substantiated not only through data derived from petroleum wells, but also by comprehensive regional geological studies [

81]. A three-dimensional thermal model was constructed to assess the present thermal conditions beneath the northern North Sea and adjacent continental regions, aiming to investigate the regional thermal regime. The model indicates that the mainland generally presents lower temperatures at a depth of 2km, although some areas exceed 90°C. However, at a depth of 7 km, the geothermal temperature is projected to reach up to 200°C, with most of the region exhibiting temperatures above 130°C .

In 2023, recent attempts to implement pilot studies have gained significant attention-in the North Sea, the Aquarius North Sea Geothermal Consortium, led by ZeGen Energy, successfully completed a 12-month geothermal assessment project for TotalEnergies. This study, finalized last year, comprehensively evaluated the potential for geothermal energy in offshore environments by integrating subsurface, wells, and topside elements. The findings provide critical insights and guidance for incorporating geothermal power into offshore renewable energy portfolios, marking a significant step toward advancing sustainable energy solutions [

82].

The Gulf of Mexico, a traditional oil and gas prone basin, historically characterized by intensive oil and gas extraction activities, could represent a significant opportunity for geothermal energy exploitation through the repurposing of existing infrastructure. With a legacy of over 53,000 drilled wells, including approximately 30,000 abandoned, and more than 7,000 established platforms, the region offers a substantial foundation for geothermal retrofit projects [

9]. Production data analysis, coupled with geothermal gradient mapping within the American sector of the Gulf, suggests the feasibility of converting offshore petroleum wells and platforms into geothermal electricity production facilities, encompassing both shallow and deep-water fields possessing adequate flow rates and temperature profiles. Initial geothermal resource assessments conducted as early as 1970 highlighted the offshore potential of the Gulf [

83]. Observed geothermal gradients demonstrate considerable heterogeneity, reaching peaks of up to 100°C/km, concentrated within zones of maximum pressure gradient alteration, while the 120°C isogeotherm, signifying a consistent temperature of 120°C, typically located between 2.500 and 5.000 meters below sea level, coinciding with the upper boundary of the geopressured zone. Furthermore, a maximum temperature of 273°C has been documented at a depth of 5.859 meters at the initial studies in the 1970s, providing initial critical data for characterizing subsurface thermal and pressure regimes within the Gulf of Mexico's geological formations [

83].

Geothermal energy potential studies performed in the Galveston Bay, area of the Gulf of Mexico, has been assessed based on data from seven offshore wells. While the geothermal gradient observed, ranging from 28 to 32°C/km, is relatively low, the depth of the wells, ranging from 4,2km to 3,2km, allows for intersection with reservoirs aquifer exhibiting temperatures between 96 and 130°C. Production rates are substantial, with one well registering 8,000 barrels of water per day and an estimated bottom-hole temperature of 102°C, potentially generating between 262,980 and 569,790 kWh annually at this water production rate. However, despite the technical feasibility, economic analyses indicate that the project is currently uncompetitive with the cost of conventionally sourced electricity in the region [

5].

A geothermal gradient map was created for the Gulf of Mexico (

Figure 11) in order to explore the feasibility of using medium-temperature oil and gas water production for clean power generation. Three specific areas were then chosen for detailed temperature gradient estimation (

Figure 12 color dots). Analysis reveals a significant variation in geothermal gradients across the region. Moving from east to west, the gradient shifts from 25 to 30 °C/km off the Alabama coast to a lower range of 15–25°C/km off eastern Louisiana, before increasing considerably to 30–60°C/km off the coast of Texas. This spatial variability suggests differing potentials for geothermal energy extraction within the Gulf of Mexico [

84].

Italy has a long history as a pioneer in geothermal energy, being home to the world’s first commercial geothermal power plant exploiting high-temperature resources on land [

17]. In recent years, however, the country has focused on the innovative concept of harnessing high-temperature geothermal energy from submarine volcanoes [

43,

85,

86]. The first country attempt to test the offshore geothermal also is Italy, which conducted by Unione Geotermica Italiana, Marsili Project [

39]. The Southern Tyrrhenian submarine volcanic district, a relatively young geological basin that formed from the Upper Pliocene to the Pleistocene, has emerged as a new area of interest for geothermal research and development. This region, characterized by tectonic extension and the formation of numerous seamounts, has been extensively studied over the past decades, yielding a wealth of geological, geophysical, and geochemical data. The presence of magmatic bodies beneath the seafloor provides significant heat sources for both deep and shallow geothermal reservoirs [

85]. Advances in offshore exploration technologies, originally developed for oil and gas industry operations, now could enable reliable and competitive assessment of the geothermal potential within these high-enthalpy offshore submarine systems. According to recent studies, the southern Tyrrhenian Sea represents a promising target for the future of geothermal energy in Italy, largely due to its elevated geothermal heat flow [

86].

Feasibility studies in the Tyrrhenian Sea have focused on the Marsili seamount (

Figure 12), situated about 100 km off Italy’s coast, which stands as the largest volcanic structure in both Europe and the Mediterranean. This massive underwater volcano, rising 3,500 meters from the seafloor to just 489 meters below sea level, spans approximately 60 km in length and 20 km in width. Its geological characteristics, including a Curie isotherm depth of 4–5 km below the crest and base temperatures exceeding 600°C, suggest the presence of significant magmatic heat sources, making Marsili a promising candidate for geothermal energy exploitation. Estimates indicate that Marsili could support a total installed capacity of up to 800 MWe, potentially delivering between 5.5 - 6.4 TWh of electricity annually, an amount that could substantially boost Italy’s renewable energy portfolio [

85,

86].

Following with detailed studies, based on preliminary and theoretical evaluations, the Marsili geothermal field could deliver significant power output by utilizing supercritical fluids at approximately 400°C and 10 bar pressure, with mass flow rates ranging from 20 to 100kg/s per interconnected well group. These operational parameters suggest a theoretical power output between 10 and 50 MWe per wells group, aligning with early capacity estimates and paralleling conditions observed in large onshore geothermal fields like The Geysers in the United States. From an energy density perspective, a 1 km³ basalt body beneath the reservoir, at 1,000°C, holds an estimated 690 TWh of thermal energy if cooled to sea temperature, given a density of 3.1 kg/m³ and a specific heat capacity of 840 J/kg°C. Cost projections, following trends in recent large geothermal plants, place the overnight investment at roughly 4,000 USD/kW. Using this cost and the projected energy output over 30 years, the levelized cost of electricity (LCOE) for the Marsili field is estimated to be around 0.040 USD/kWh, highlighting its potential economic viability [

85,

86].

Another volcanic area investigated for geothermal energy recovery is located in Indonesia. Boasting the world’s second-largest installed geothermal capacity, has become a significant focus for offshore geothermal potential, particularly in regions associated with high-enthalpy springs and volcanic activity [

34,

39,

43]. One prominent area under investigation is the Sangihe Archipelago, located north of Sulawesi Island. This archipelago lies along a volcanic arc that has resulted from the ongoing subduction of the Philippine plate beneath the Micro-Sunda plate, a geological process that not only shapes the region’s landscape but also enriches it with geothermal energy resources. The relatively young age of this volcanic arc enhances its suitability for high-enthalpy geothermal development, as youthful volcanic regions typically exhibit more accessible and vigorous geothermal systems[

39].

The presence of seamounts serves as further evidence of substantial subsurface heat flow and geothermal potential. Preliminary assessments of these offshore resources employ a range of geophysical and geological methods, including bathymetric mapping to understand seafloor structures, gravity measurements to detect subsurface density anomalies, magnetic surveys to identify variations in rock magnetism, and broader regional geological studies. Findings from these surveys have revealed distinct features such as volcanic arc alignments, outer-arc ridge structures, and the occurrence of hot springs, surface manifestations indicative of underlying geothermal systems. By integrating the results of these varied analytical approaches, researchers have been able to pinpoint likely zones of geothermal activity, often marked by combinations of significant elevation, high gravity values suggesting dense, hot rocks beneath the surface, and low geomagnetic readings which may indicate hydrothermal alteration [

39]. Collectively, these early investigative efforts highlight Indonesia’s promising potential for harnessing offshore geothermal energy in tectonically active, volcanically influenced regions like the Sangihe Archipelago [

39,

43]. North Tech Energy is partnering with Indonesian developers and turbine producers to establish small offshore geothermal power stations. This collaboration aims to harness Indonesia’s abundant geothermal resources by deploying compact, efficient power generation units at sea [

43,

87].

Other countries and initiatives have considered electricity generated from offshore geothermal plants, which include India, Portugal, Italy, Philippines, Japan, and Russia, along with Central America and the Caribbean [

10] . The analysis of various configurations for power production from offshore geothermal resources in the geothermal field Reykjanes, Iceland, has been developed looking increment geothermal potential [

10]. Alternatives investigations are underway in the near-shore Pacific region to explore geothermal energy as a reliable and renewable base-load power source for U.S. Naval operations [

88].

4.1. Petroleum and Offshore Geothermal Exploration Subsurface Technology Synergy

Exploring offshore geothermal resources relies heavily on the expertise and technology developed for offshore oil and gas exploration and production. Decades of investment and developments in maritime subsurface research have equipped the oil industry with advanced tools and methods for subsurface prospections. As a result, efforts to identify and characterize offshore geothermal resources will inevitably draw on the established technologies, operational experience, and service providers of oil and gas companies. For instance, geophysical techniques such as seismic and potential field methods, which are widely used in oil and gas exploration, play a crucial role in the effective characterization of geothermal resources beneath the seafloor. This transfer of technology and experience is expected to accelerate the development of offshore geothermal energy by reducing technical risks and exploration costs. This synergy and technology transfer have been documented in several reports and pointed out [

19,

89]. Here we show some examples of geophysical and geological studies to characterize offshore geothermal fields.

Seismic data attends as an essential tool for offshore geothermal characterization, similar to their application in petroleum exploration. In the Gulf of Candarli, Turkey, seismic reflection data combined with petrophysical measurements have been utilized to develop a three-dimensional pore-pressure temperature model, also named as a static temperature cube [

90]. This 3D petrophysical modeling approach has been chosen as the primary method for seismic interpretation correlation and then for comprehensive subsurface integration data. Interval seismic velocities obtained at shot points were converted into point data and imported into specialized software to create detailed velocity models. These models were then validated against expected lithological formations in the area to ensure geological accuracy. Subsequently, the velocity data were transformed into static temperature estimates using the formula proposed by Ryan et al., [

91], whose method has been shown to closely match temperature profiles observed in geothermal fields such as those in the West Indies.

This methodology offers a reliable framework to correlate seismic velocity with petrothermal properties, thereby improving the precision of subsurface temperature predictions. The results from this study suggest that the Gulf of Candarli exhibits low to medium geothermal gradients (

Figure 13), with subsurface temperatures potentially reaching around 100°C, indicating moderate geothermal potential in the region [

90].

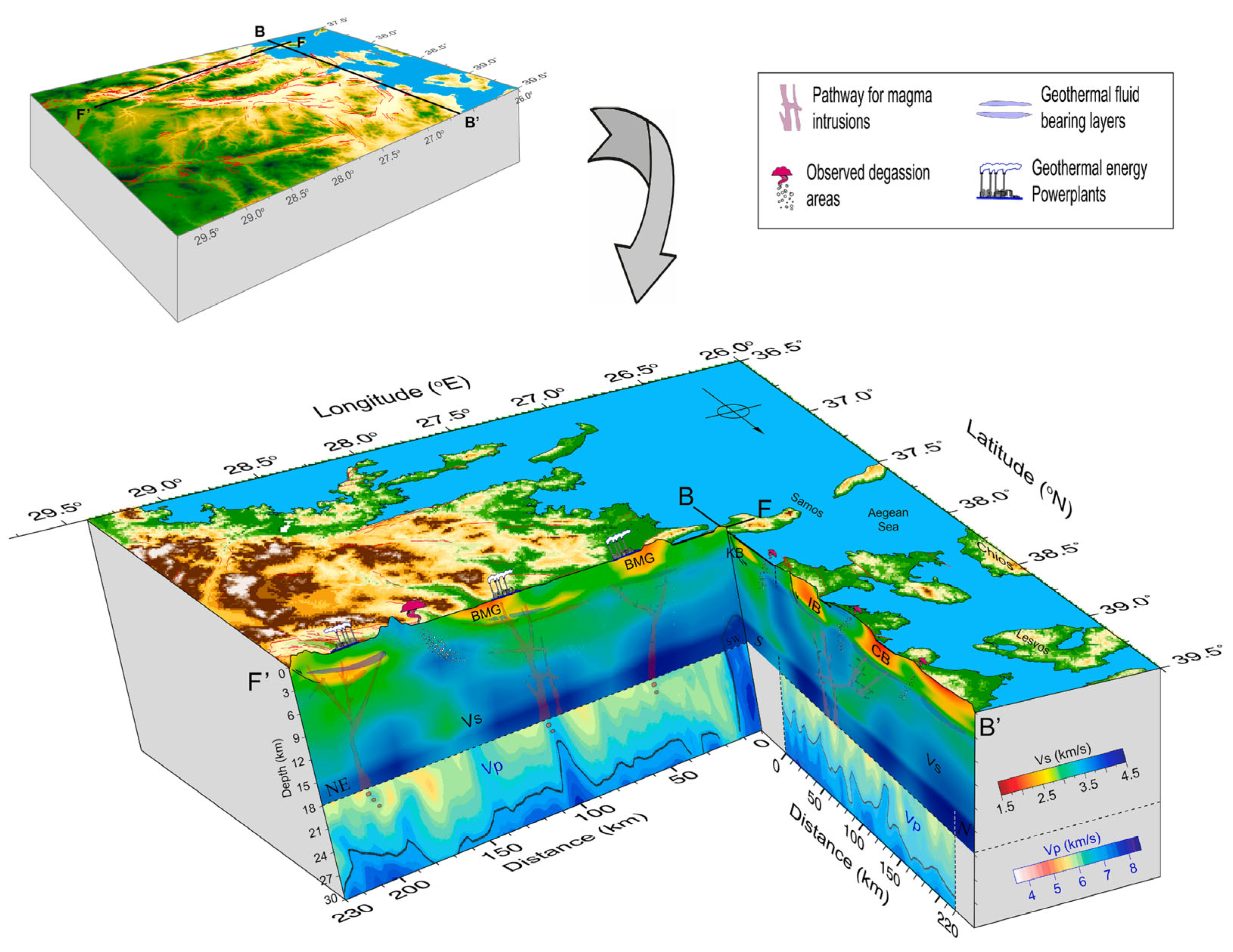

Another advanced seismic use for geothermal focuses on the use of energy from earthquake as a seismic source. In the regional study, Mulumulu et al., [

92] demonstrates the application of passive seismology to create geothermal 3D models that connect onshore and offshore thermal fields in the Aegean region of Turkey. Ambient noise tomography (ANT), a passive and non-destructive seismological imaging technique, is employed to explore the crustal structure at a relatively low cost. By cross-correlating ambient noise signals recorded at various seismic stations across the region, the shear wave velocity of the crust is measured to depths of up to 18 km. Turkey, known for its intense seismic activity, provides abundant data through which these measurements are derived. The resulting velocity models help identify low-velocity zones that are potentially favorable for geothermal resources, thereby guiding future geothermal exploration campaigns. Enhancing the understanding of crustal structure is critical for developing offshore geothermal energy by revealing the geological relationships that control the distribution of geothermal reservoirs. A 3D conceptual model showed in

Figure 14 was constructed from shear wave velocity (Vs) computations combined with previously reported P-wave velocity (Vp) and Vp/Vs anomalies, effectively linking onshore geothermal fields with offshore areas and supporting planning for upcoming geothermal projects [

92].

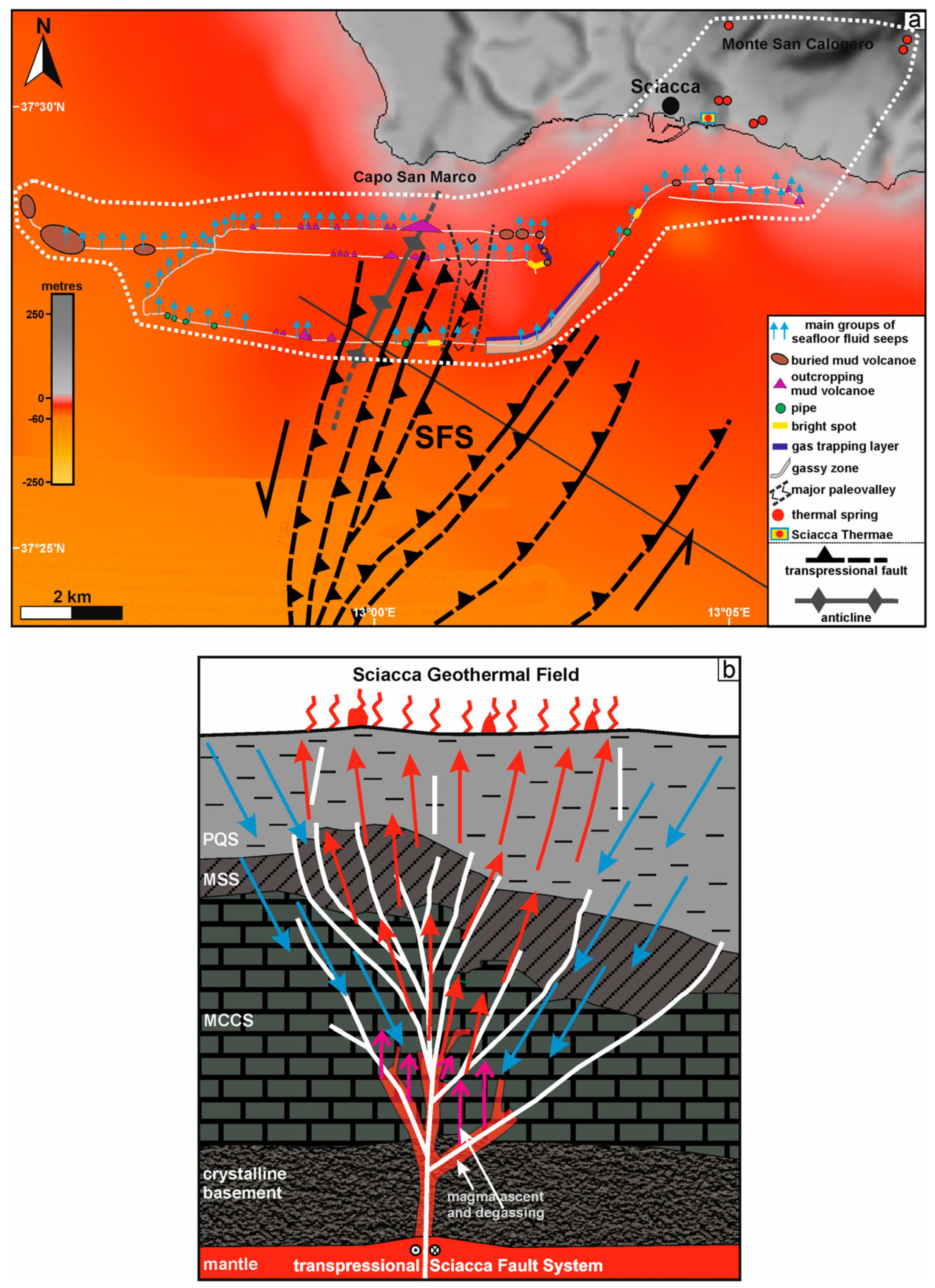

The Sciacca basin, situated in the southern region of western Sicily, is the home of geothermal resources known as the Sciacca Geothermal Field, which is closely associated with the Sciacca Fault System. To better understand the characteristics of this geothermal field towards offshore in this area, Civile et al., [

93] conducted a high-resolution seismic reflection interpretation. The results of this study led to the hypothesis that active fault zones play a crucial role in enabling the upward movement of geothermal fluids from deeper underground. These faults maintain open fractures and dynamically preserve effective permeability within the geothermal reservoir, thereby facilitating the continuous flow and accessibility of thermal fluids (

Figure 15). This insight is important for assessing geothermal potential and for future resource management in the region [

93].

5. Final Remarks

Offshore geothermal energy is a feasible low-carbon energy source. Despite its potential, the technology remains largely in the concept phase, with limited progress made in terms of demonstration or commercial production. The exploration of geothermal energy in offshore environments faces challenges, resulting in relatively slow advancement compared to onshore geothermal developments or others renewable energy sources. This paper review emphasizes the potential of harnessing medium-temperature hot water produced during offshore oil and gas operations for efficient clean power generation. Additionally, it explored the opportunities presented by high-enthalpy thermal fields associated with submarine volcanic areas, which could offer significant geothermal energy resources in the offshore ambient.

Analyzing the number of patents published over the last 25 years revealed a low count, especially compared to those related to renewable energies from intermittent sources. This highlights the need for increased investments and incentives in unconventional geothermal resources. Although there are more published articles, many remain focused on conceptual studies. A combined increase in research and patent activities could significantly benefit the development of offshore geothermal resources.

The technology for exploring and exploiting offshore geothermal fields is well established. Most of the technologies originate from the petroleum industry and on shore traditional geothermal harness. However, some improvement and transfer technology shall be required.

The primary factor limiting the expansion of offshore geothermal energy production is economics limitations. High upfront costs, uncertain resource assessments, and the financial risks associated with deepwater drilling make these projects less attractive compared to more established renewable energy sources. Consequently, economic challenges continue to hinder the large-scale development of offshore geothermal energy, even though the technical capabilities exist to support it. Additionally, the protection of the marine environment during exploration activities is essential and should be carried out carefully. Many near shore areas are designated as protected zones to preserve biodiversity and prevent damage from human activities and are not allowed for economic exploration. Another limitation in implementing co-generation of electrical energy on petroleum platforms is the space and weight of the required equipment. Offshore platforms have strict constraints on available space and load capacity, making it challenging to retrofit existing installations with additional machinery.

For offshore geothermal resource exploration, the use of multidisciplinary data is essential in accurately estimating geothermal potentials. An integrated approach that combines various types of data— including bathymetry, elevation, residual gravity, seismic and geomagnetic measurements—provides a comprehensive understanding of the subsurface conditions and helps identify promising geothermal sites.

High enthalpy areas associated with volcanic activity and hot spots are widely distributed throughout the globe, making them a significant and promising source of geothermal energy. This broad geographic distribution offers an advantage for countries aiming to develop clean energy solutions, particularly in offshore environments where such high-temperature resources can be harnessed. The availability of geothermal resources with high temperatures enables efficient geothermal energy conversion, which could potentially lead to competitive production costs compared to other energy sources in the future.

Hydrocarbon reservoirs store substantial thermal energy mainly due to their large size and amount of hot water production. Nonetheless, most have temperatures below 150°C. At these relatively low temperatures, the thermal energy quality is low, limiting the efficiency of energy recovery and the range of extraction methods require advanced technology. Using organic fluids with lower boiling points than water can be a significant breakthrough for low-enthalpy electric conversion.

Oil industry companies and mostly those with substantial offshore experience possess notable competitive advantages. Their expertise in subsurface characterization, sea drilling, subsea technologies, and complex project management provides them with the skills required to develop and operate offshore geothermal facilities. Additionally, these companies already have established infrastructure and supply chains, allowing for a more efficient transition into geothermal energy compared to traditional land geothermal firms that are less familiar with offshore environments.

Although oil and gas reservoirs offer significant potential for energy development, current technologies for generating electricity from this heat are mostly in pilot stages and have not yet been widely applied. The main technical challenge is the low efficiency of heat exchange processes, which restricts the scalability and practical use of these methods.

Advances in both practical projects and theoretical knowledge are essential to fully realize the potential of unconventional geothermal energy within the oil and gas sector. This emerging technology not only enhances the production of low-carbon power, thereby reducing the sector's carbon footprint, but also can offer a sustainable approach to extend the operational lifespan of existing infrastructure. By integrating geothermal solutions, petroleum operators and service companies can minimize the costly and complex process of decommissioning mature fields. Additionally, these innovations help optimizing resource utilization and enable the delay of field closures, ultimately improving the economic and environmental outcomes for the industry. Continued research and development in this area are critical to overcoming current challenges and unlocking the full benefits of unconventional geothermal energy.