Submitted:

30 April 2025

Posted:

02 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

“I have the gift, when I close my eyes and, with my head bowed down, think of a flower in the center of my visual organ, it does not remain for a moment in its first form, but it spreads out and from within it unfolds again new flowers of colored, even green, leaves; they are not natural flowers, but fantastic, but regular, like the rosettes of the sculptors. It is impossible to foresee the sprouting creation, but it lasts as long as I like, does not tire and does not intensify. I can produce the same if I think of the ornament of a colorfully painted disk, which then also changes continuously from the center to the periphery, completely like the kaleidoscopes.” [1] (Fechner, 1860).

- (i)

- Are the VVI differences in self-reports “real”, i.e., do they enable rich, precise, falsifiable predictions?

- (ii)

- Do the phenomenological features of VVI correspond to measurable functional advantages in memory or thinking?

- (iii)

- Does VVI have any corresponding structural, neurological foundation?

2. Materials and Methods

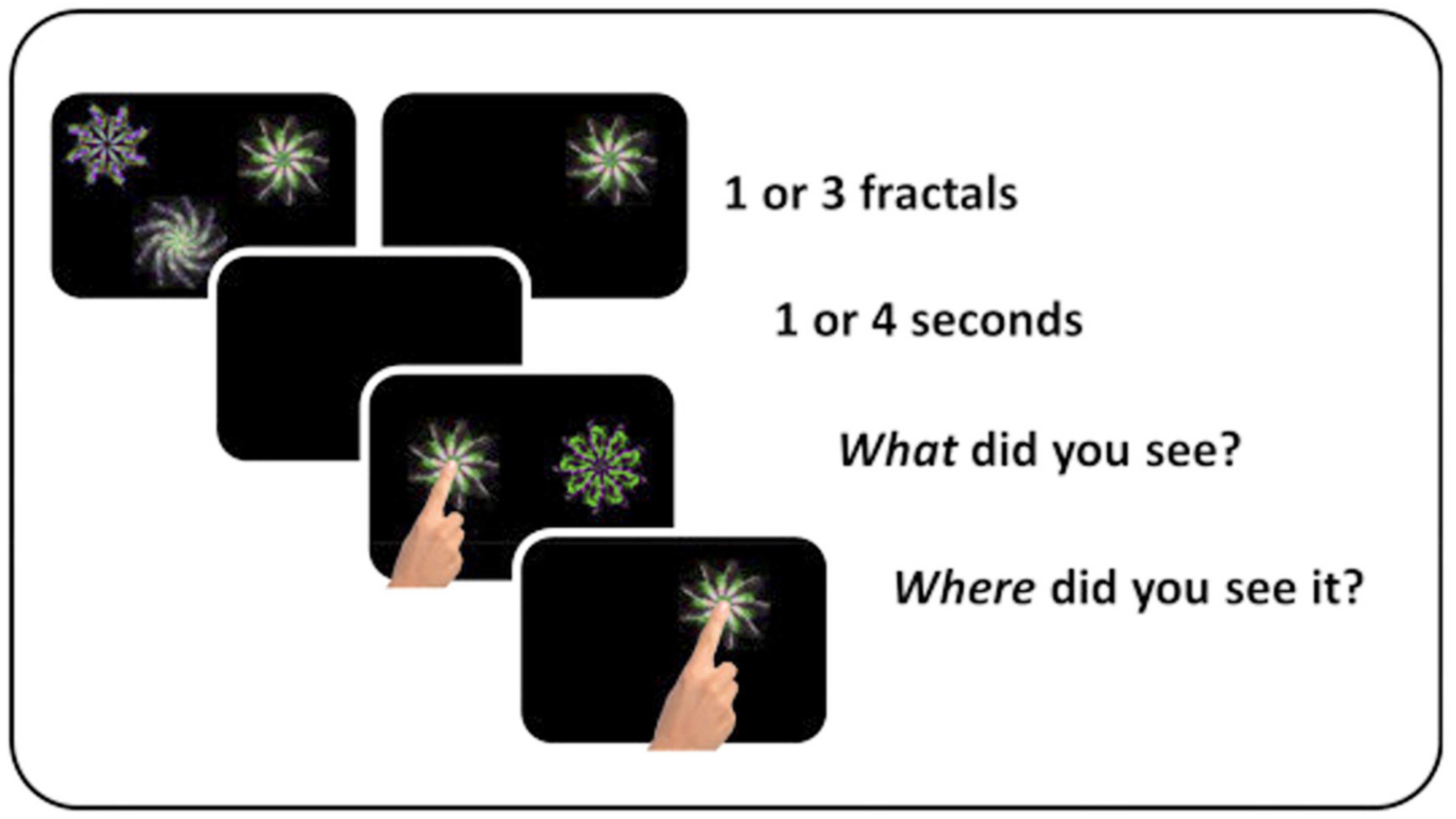

2.1. Short-Term Memory Task

- Identification Accuracy: Trials in which the correct shape was identified out of two divided by the total number of trials of each condition. Trials in which participants did not identify the correct item were excluded from further analysis.

- Response Time: Time taken to point to the correct shape.

- Localisation Performance: Distance between the response and the original target’s location.

- Mis-binding; The probability that a participant can correctly remember the appearances and locations of the shapes at test but confuses or “misbinds” these locations and appearances resulting in the report of another shape’s location for a correctly identified shape.

- Guessing, Guessing indicates a random response likely given when the viewer has forgotten any precise information about the target.

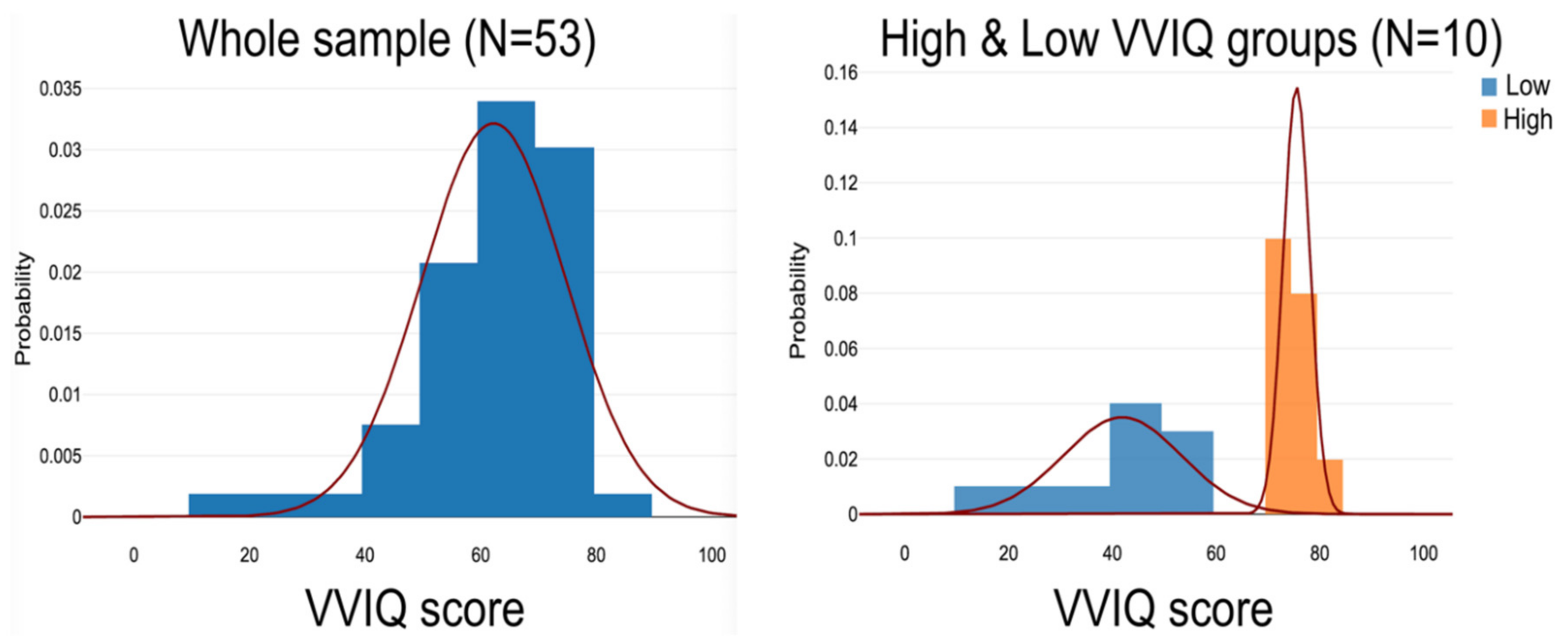

2.2. Vividness of Visual Imagery

2.3. MRI Analysis

2.4. Availability of Data

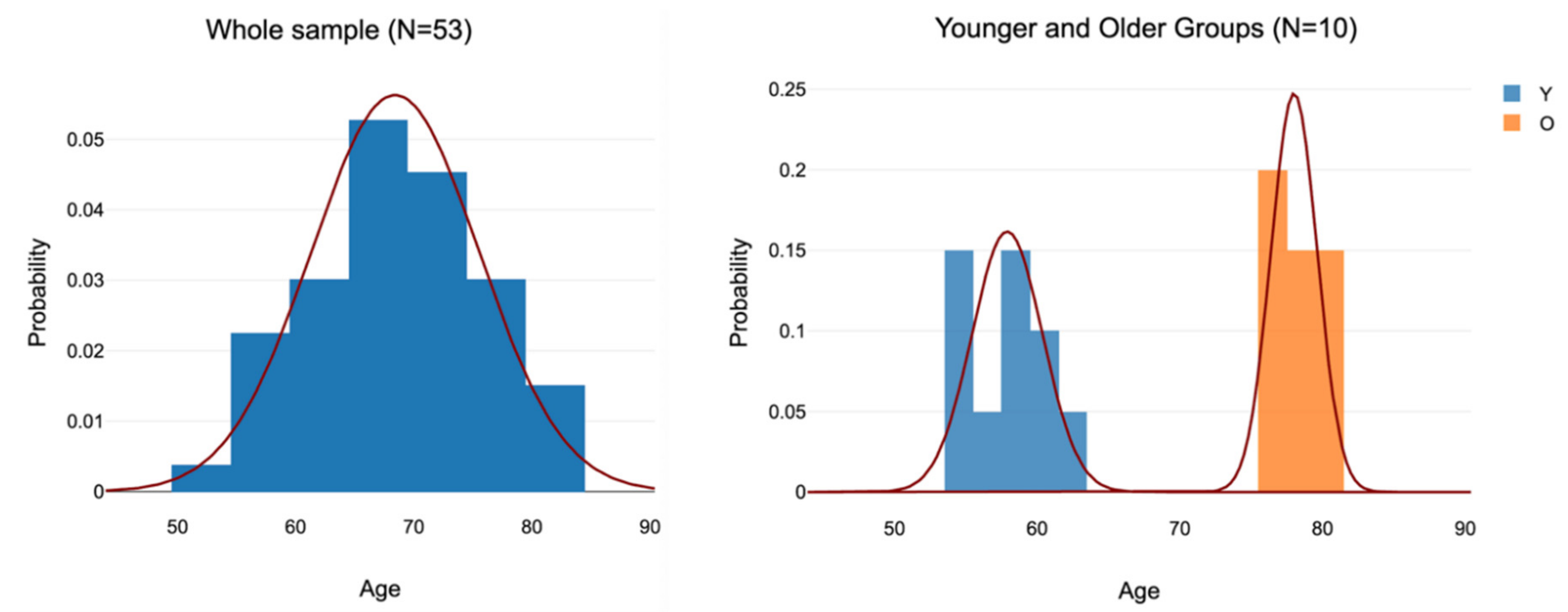

2.5. Participants

3. Results

3.1. VVIQ Scores

3.2. Visual Short-Term Visual Memory (VSTM)

3.2.1. Absolute Error Scores

3.2.2. Mean Guessing Rates

3.2.3. Mean Misbinding Rates

3.2.4. Mean Response Times and Proportions Correct

3.2.5. Aphant and hphant VSTM Results

3.3. MRI Volume Scores

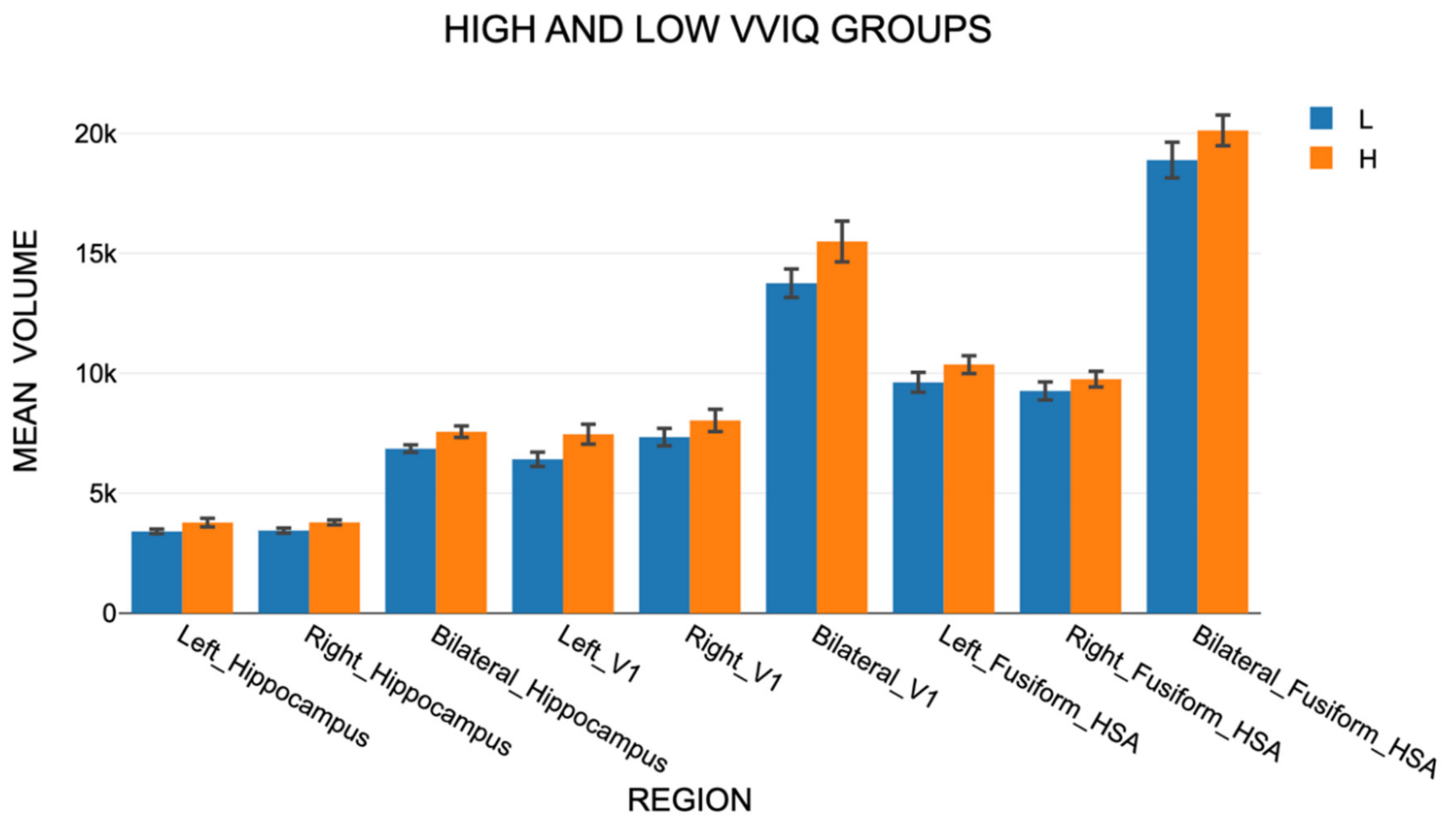

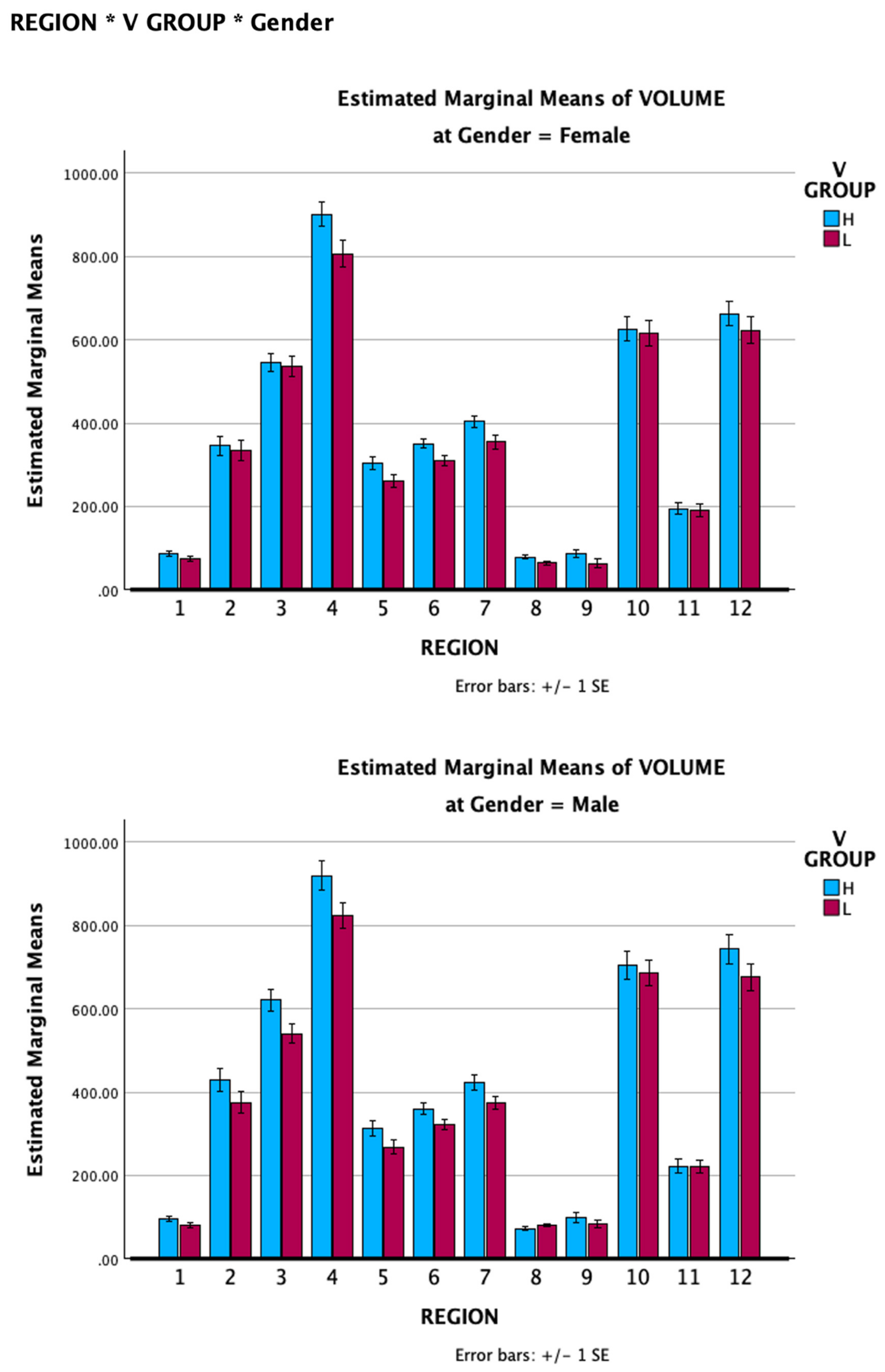

3.3.1. Findings for Set A Areas

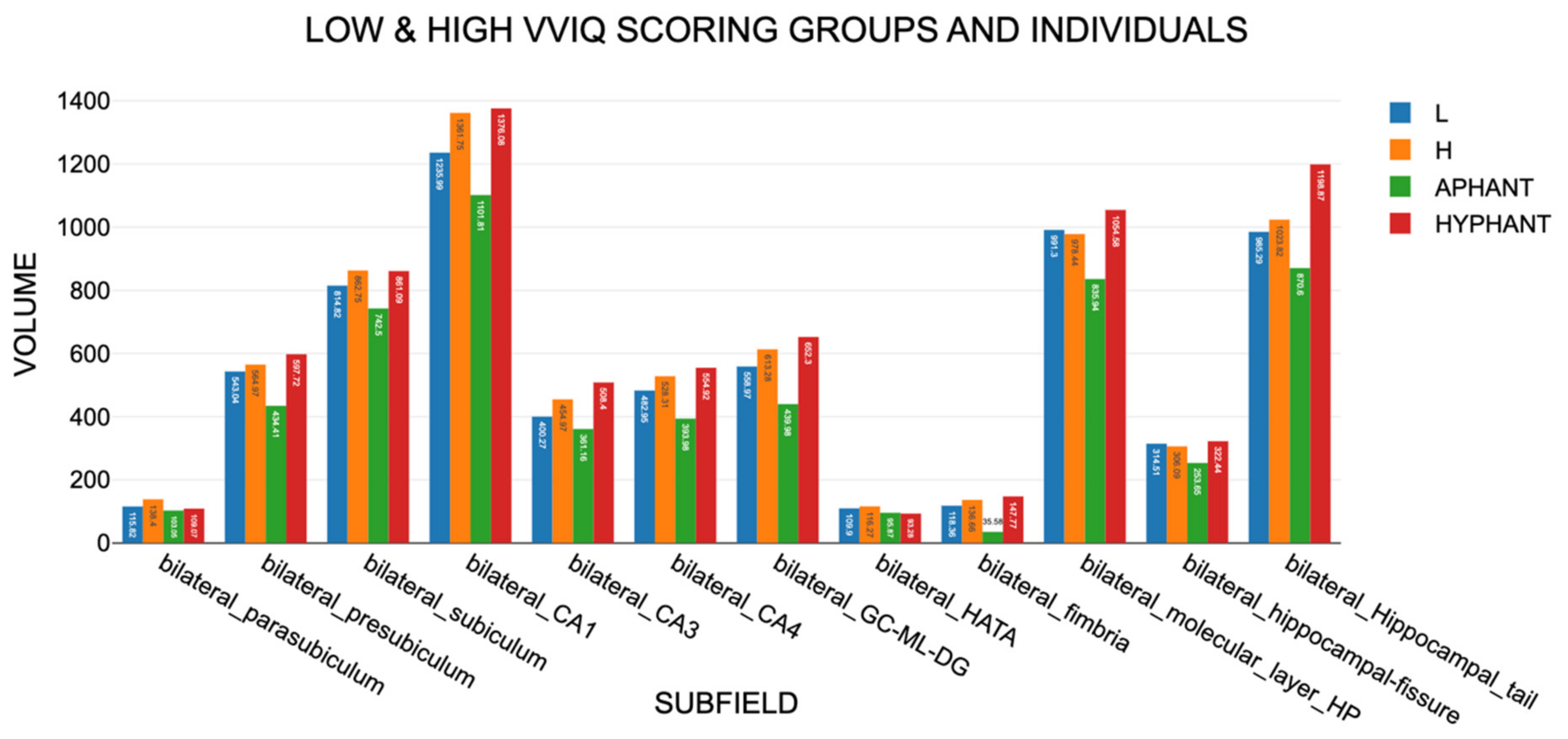

3.3.2. Findings for Set B Subfields

3.3.3. Findings for the Amygdala

3.3.4. Findings for Set D Subfields

3.3.5. Findings for the aphant and hphant

3.3.6. Other Analyses and Observations

3.4. Summary of findings

| Label | Hypothesis | Outcome |

| H1 | People with vivid visual imagery have greater visual short-term memory capacity than people with non-vivid visual imagery. | Strongly supported p=2.38×10−5 |

| H2 | Females have greater visual short-term memory capacity than males. | Supported p = .075 |

| H3 | Younger people have greater visual short-term memory than older people. | Supported p=.01 |

| H4 | In VMIF brain regions, the High VVIQ group have larger volumes than the Low VVIQ group. | Strongly supported p=.012, p=.011, p=0 (rank order correct for 46/47 areas) |

| H5 | In VMIF brain regions, females have larger volumes than males. | Unsupported |

| H6 | In VMIF brain areas younger people have larger volumes than older people. | Unsupported |

| H7 | In non-VMIF brain areas, High and Low VVIQ groups have no volume differences. | Supported |

| H8 | In non-VMIF brain areas, females and males have no volume differences. | Supported |

| H9 | In non-VMIF brain areas, younger and older people have no volume differences. | Supported |

| H10 | Aphant has worse than average VSTM | Unsupported NS |

| H11 | Hphant has better than average VSTM | Unsupported NS |

| H12 | Hphant has better VSTM than aphant | Supported but NS |

| H13 | Aphant has smaller than average VMIF volumes | Supported in 10 areas |

| H14 | Hphant has larger than average VMIF volumes | Supported in 2 areas |

| H15 | Hphant has larger VMIF volumes than aphant | Supported p<.001 |

| H16 | Volume sizes will follow a predictable sequence: hphant, high VVIQ group, entire sample mean, low VVIQ group, aphant |

Predicted order correct 30/57 times: p=0 |

4. Discussion

4.1. General Significance of the Findings

4.1.1. VSTM

4.1.2. Brain Region Differences

4.1.3. The aphant Profile

4.1.4. The hphant Profile

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

4.2.1. Independence and Transparency

4.2.2. Small Group Sizes

5. Conclusions

- 1)

- Are VVI differences real? If by “real” we mean that we can make rich, precise, falsifiable predictions using VVI measures, then the answer is affirmative. Vividness differences are “real” because they enable rich, precise and falsifiable predictions which produced here a set of highly significant findings.

- 2)

- What functions do these differences serve? High VVI serves three primary functions: (A) remembering recent and distant-past stimuli, scenarios, episodes and events; (B) anticipating, foreseeing and simulating near and distant future stimuli, scenarios, episodes and events; (C) constructing phantasy for dreams, imaginary stimuli, scenarios, episodes and events. Low or absent VVI requires alternative, non-imagistic mnemonic strategies such as scaffolding, tagging and listing, to perform tasks but, in some cases, less efficiently.

- 3)

- What is their neurological foundation? VVI differences are founded on brain systems that vary functionally and structurally in magnitude, variance, precision, asymmetry and connectedness. To date, we have only scratched the surface, and further reports will follow.

References

- Fechner, G. Elements of Psychophysics 1860.

- Marks, D.F. Gustav Fechner’s observations on his own and others’ visual mental imagery. J. Educ. Psychol. Res. 2023, 5, 651–675. [Google Scholar]

- Marks, D.F. The Action Cycle Theory of Perception and Mental Imagery. Vision 2023, 7, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marks, D.F. Individual Differences in the Vividness of Visual Imagery and Their Effect on Function. In The Function and Nature of Imagery; Sheehan, P.W., Ed. Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1972; pp. 83–108. [Google Scholar]

- Marks, D.F. Phenomenological Studies of Visual Mental Imagery: A Review and Synthesis of Historical Datasets. Vision 2023, 7, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilzer, M.; Monzel, M. The Phenomenology of Offline Perception: Multisensory Profiles of Voluntary Mental Imagery and Dream Imagery. Vision 2025, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belfi, A. M., Vessel, E. A., & Starr, G. G. (2018). Individual ratings of vividness predict aesthetic appeal in poetry. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 12(3), 341. Belfi, A. M. (2019). Emotional valence and vividness of imagery predict aesthetic appeal in music. Psychomusicology: Music, Mind, and Brain, 29(2-3), 128.

- Marks, D.F. The General Theory of Behaviour: A Sourcebook. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2025.

- Marks, D.F. “Visual imagery differences in the recall of pictures.” British journal of Psychology 64.1 (1973): 17-24.

- Baddeley, A.D. and Andrade, J. (2000) Working memory and the vividness of imagery. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 129, 126–145.

- Chkhaidze, A., Coulson, S., & Kiyonaga, A. (2023). Individual Differences in Preferred Thought Formats Predict Features of Narrative Recall. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society (Vol. 45, No. 45).

- Keogh, R, & Pearson, J. (2011). Mental imagery and visual working memory. PLoS ONE, 6, e29221.

- Keogh, Rebecca, & Pearson, J. (2014). The sensory strength of voluntary visual imagery predicts visual working memory capacity. Journal of Vision, 14(12), 1427–1431.

- Gur, R. C., & Hilgard, E. R. (1975). Visual imagery and the discrimination of differences between altered pictures simultaneously and successively presented. British Journal of Psychology, 66(3), 341-345.

- McKelvie, S. J., & Demers, E. G. (1979). Individual differences in reported visual imagery and memory performance. British Journal of Psychology, 70(1), 51-57.

- Berger, G. H., & Gaunitz, S. C. (1979). Self-rated imagery and encoding strategies in visual memory. British Journal of Psychology, 70(1), 21-24.

- Slee, J. A. (1980). Individual differences in visual imagery ability and the retrieval of visual appearances. Journal of Mental Imagery, 4(1), 93–113.

- McKelvie, S.J. (1995). The VVIQ as a psychometric test of individual differences in visual imagery vividness: A critical quantitative review and plea for direction. Journal of Mental Imagery, 19(3- 4), 1–106.

- Rodway, P., Gillies, K., & Schepman, A. (2006). Vivid imagers are better at detecting salient changes. Journal of Individual Differences, 27(4), 218–228.

- Jacobs, C., Schwarzkopf, D. S., & Silvanto, J. (2018). Visual working memory performance in aphantasia. Cortex, 105, 61-73.

- Heuer, F., Fischman, D., & Reisberg, D. (1986). Why does vivid imagery hurt colour memory? Canadian Journal of Psychology / Revue canadienne de psychologie, 40(2), 161–175.

- Reisberg, D., Culver, L. C., Heuer, F., & Fischman, D. (1986). Visual memory: When imagery vividness makes a difference. Journal of Mental Imagery, 10(4), 51–74.

- Reisberg, D., & Leak, S. (1987). Visual imagery and memory for appearance: Does Clark Gable or George C. Scott have bushier eyebrows? Canadian Journal of Psychology / Revue canadienne de psychologie, 41(4), 521–526.

- Zhang, Ziao, et al. “Effects of age and gender on the vividness of visual imagery: a study with the Chinese version of the VVIQ (VVIQ-C).” (2024).

- Zeman, A., Dewar, M., & Della Sala, S. (2015). Lives without imagery – Congenital aphantasia. Cortex, 73, 378–380.

- Zeman, A., Milton, F., Della Sala, S., Dewar, M., Frayling, T., Gaddum, J., Hattersley, A., Heuerman-Williamson, B., Jones, K., MacKisack, M., & Winlove, C. (2020). Phantasia–The psychological significance of lifelong visual imagery vividness extremes. Cortex, 130, 426–440.

- Blomkvist, A., & Marks, D. F. (2023). Defining and ‘diagnosing’ aphantasia: Condition or individual difference? Cortex, 169, 220-234.

- Jin, F.; Hsu, S.-M.; Li, Y. A Systematic Review of Aphantasia: Concept, Measurement, Neural Basis, and Theory Development. Vision 2024, 8, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geschwind, N. Disconnexion syndromes in animals and man. I. Brain. 1965 Jun;88(2):237-94.

- Farah, M. J., Levine, D. N., & Calvanio, R. (1988). A case study of mental imagery deficit. Brain and cognition, 8(2), 147-164.

- Marks, D.F. (1990). On the relationship between imagery, body and mind. In P J Hampson, D F Marks and John T E Richardson (eds.) Imagery. Current developments. Pp. 1-38.

- Marks, D. F., Uemura, K., Tatsuno, J., Imamura, Y., & Ashida, H. (1985). Topographical analysis of alpha attenuation in mental imagery and calculation. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology, 61(3), S142.

- Marks, Uemura, Tatsuno and Imamura, 1985; Marks, D., Uemura, K., Tatsuno, J., & Imamura, Y. (1985). EEG topographical analysis of imagery. Contemporary psychology: Biological processes and theoretical issues, Amsterdam: Elsevier. Pp. 211-223.

- Marks, D. F., & Isaac, A. R. (1995). Topographical distribution of EEG activity accompanying visual and motor imagery in vivid and non-vivid imagers. British Journal of Psychology, 86(2), 271-282.

- Farah, M. J. (1984). The neurological basis of mental imagery: A componential analysis. Cognition, 18(1-3), 245-272.

- Kosslyn, S. M., & Thompson, W. L. (2003). When is early visual cortex activated during visual mental imagery?. Psychological bulletin, 129(5), 723.

- Amedi, A., Malach, R., & Pascual-Leone, A. (2005). Negative BOLD differentiates visual imagery and perception. Neuron, 48(5), 859-872.

- Cui, X., Jeter, C. B., Yang, D., Montague, P. R., & Eagleman, D. M. (2007). Vividness of mental imagery: Individual variability can be measured objectively. Vision research, 47(4), 474-478.

- Dijkstra, N., Bosch, S. E., & van Gerven, M. A. (2019). Shared neural mechanisms of visual perception and imagery. Trends in cognitive sciences, 23(5), 423-434.

- Pearson, J. (2019). The human imagination: the cognitive neuroscience of visual mental imagery. Nature reviews neuroscience, 20(10), 624-634.

- Spagna, Alfredo, et al. “Visual mental imagery engages the left fusiform gyrus, but not the early visual cortex: A meta-analysis of neuroimaging evidence.” Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 122 (2021): 201-217.

- Dijkstra, N. Uncovering the Role of the Early Visual Cortex in Visual Mental Imagery. Vision 2024, 8, 29.

- Genç, Erhan, et al. “Surface area of early visual cortex predicts individual speed of traveling waves during binocular rivalry.” Cerebral cortex 25.6 (2015): 1499-1508.

- Fulford, J., Milton, F., Salas, D., Smith, A., Simler, A., Winlove, C., & Zeman, A. (2018). The neural correlates of visual imagery vividness–An fMRI study and literature review. Cortex, 105, 26-40.

- Duan, S., Li, Q., Yang, J., Yang, Q., Li, E., Liu, Y., … & Zhao, B. (2025). Precuneus activation correlates with the vividness of dynamic and static imagery: an fMRI study. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 19, 1516058.

- Tullo, M. G., Almgren, H., Van de Steen, F., Sulpizio, V., Marinazzo, D., and Galati, G. (2022). Individual differences in mental imagery modulate effective connectivity of scene-selective regions during resting state. Brain Struct. Funct. 227, 1831–1842.

- Kvamme, T. L., Lumaca, M., Zana, B., Paunovic, D., Silvanto, J., & Sandberg, K. (2024). Vividness of Visual Imagery Supported by Intrinsic Structural-Functional Brain Network Dynamics. bioRxiv, 2024-03.

- Blomkvist, A. (2025). Shaping the Space: A Role for the Hippocampus in Mental Imagery Formation. Vision, 9(1), 2. [CrossRef]

- Ellis, H. (1894). Man and Woman: A Study of Secondary Sexual Characters. London Walter Scott, Ltd.

- Horgan, T. G., Mast, M. S., Hall, J. A., & Carter, J. D. (2004). Gender Differences in Memory for the Appearance of Others. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30(2), 185-196.

- McBurney, D. H., Gaulin, S. J., Devineni, T., & Adams, C. (1997). Superior spatial memory of women: Stronger evidence for the gathering hypothesis. Evolution and Human Behavior, 18(3), 165-174.

- J Choi, I Silverman (1996). Sexual dimorphism in spatial behaviors: Applications to route learning Evolution and Cognition 2, 165-171.

- James, T. W., & Kimura, D. (1997). Sex differences in remembering the locations of objects in an array: Location-shifts versus location-exchanges. Evolution and Human Behavior, 18(3), 155-163.

- McGivern, R. F., Huston, J. P., Byrd, D., King, T., Siegle, G. J., & Reilly, J. (1997). Sex differences in visual recognition memory: support for a sex-related difference in attention in adults and children. Brain and cognition, 34(3), 323-336.

- Levy, L. J., Astur, R. S., & Frick, K. M. (2005). Men and women differ in object memory but not performance of a virtual radial maze. Behavioral neuroscience, 119(4), 853.

- Silverman, Irwin, Jean Choi, and Michael Peters. “The hunter-gatherer theory of sex differences in spatial abilities: Data from 40 countries.” Archives of sexual behavior 36 (2007): 261-268.

- Russell, E. M., Longstaff, M. G., & Winskel, H. (2024). Sex differences in eyewitness memory: A scoping review. Psychonomic bulletin & review, 31(3), 985-999.

- Herlitz, A., & Rehnman, J. (2008). Sex differences in episodic memory. Current directions in psychological science, 17(1), 52-56.

- Asperholm M, Hogman N, Rafi J and Herlitz A (2019). What did you do yesterday? A metaanalysis of sex differences in episodic memory. Psychol. Bull. 145, 785-821.

- Voyer, D., Voyer, S. D., & Saint-Aubin, J. (2017). Sex differences in visual-spatial working memory: A meta-analysis. Psychonomic bulletin & review, 24, 307-334.

- Filipek, P.A., Richelme, C., Kennedy, D.N., Caviness V.S., Jr (1994) The young adult human brain: An MRI-based morphometric analysis. Cereb. Cortex 4:344–360.

- Filipek, Pauline A., et al. “Volumetric MRI analysis comparing subjects having attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder with normal controls.” Neurology 48.3 (1997): 589-601.

- Murphy, D. G., DeCarli, C., Mclntosh, A. R., Daly, E., Mentis, M. J., Pietrini, P., … & Rapoport, S. I. (1996). Sex differences in human brain morphometry and metabolism: an in vivo quantitative magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography study on the effect of aging. Archives of general psychiatry, 53(7), 585-594.

- Paus, T., Otaky, N., Caramanos, Z., Macdonald, D., Zijdenbos, A., d’Avirro, D., … & Evans, A. C. (1996). In vivo morphometry of the intrasulcal gray matter in the human cingulate, paracingulate, and superior-rostral sulci: Hemispheric asymmetries, gender differences and probability maps. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 376(4), 664-673.

- Schlaepfer, T. E., Harris, G. J., Tien, A. Y., Peng, L., Lee, S., & Pearlson, G. D. (1995). Structural differences in the cerebral cortex of healthy female and male subjects: a magnetic resonance imaging study. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, 61(3), 129-135.

- Guadalupe, Tulio, et al. “Asymmetry within and around the human planum temporale is sexually dimorphic and influenced by genes involved in steroid hormone receptor activity.” Cortex 62 (2015): 41-55.

- Witelson, S.F., Glezer, I.I., Kigar, D.L. (1995) Women have greater density of neurons in posterior temporal cortex. J. Neurosci. 15:3418–3428.

- Giedd, Jay N., et al. “Quantitative magnetic resonance imaging of human brain development: ages 4–18.” Cerebral cortex 6.4 (1996): 551-559.

- Paus, Tomáš, et al. “In vivo morphometry of the intrasulcal gray matter in the human cingulate, paracingulate, and superior-rostral sulci: Hemispheric asymmetries, gender differences and probability maps.” Journal of Comparative Neurology 376.4 (1996): 664-673.

- Persson, Jonas, et al. “Sex differences in volume and structural covariance of the anterior and posterior hippocampus.” Neuroimage 99 (2014): 215-225.

- Dalton, M. A., Zeidman, P., McCormick, C., & Maguire, E. A. (2018). Differentiable processing of objects, associations, and scenes within the hippocampus. Journal of Neuroscience, 38(38), 8146-8159.

- Fjell, A. M., Sneve, M. H., Amlien, I. K., Grydeland, H., Mowinckel, A. M., Vidal-Piñeiro, D., … & Walhovd, K. B. (2025). Stable hippocampal correlates of high episodic memory function across adulthood. Scientific Reports, 15(1), 8816.

- Harrison, Theresa M., et al. “Superior memory and higher cortical volumes in unusually successful cognitive aging.” Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society 18.6 (2012): 1081-1085.

- Dawes AJ, Keogh R, Robuck S, Pearson J. 2022. Memories with a blind mind: Remembering the past and imagining the future with aphantasia. Cognition 227:105192.

- Monzel, M., Leelaarporn, P., Lutz, T., Schultz, J., Brunheim, S., Reuter, M., & McCormick, C. (2024). Hippocampal-occipital connectivity reflects autobiographical memory deficits in aphantasia. Elife, 13, RP94916.

- Blomkvist, A. (2023). Aphantasia: In search of a theory. Mind & Language, 38(3), 866-888.

- Tabi, Y. A., Maio, M. R., Attaallah, B., Dickson, S., Drew, D., Idris, M. I., … & Husain, M. (2022). Vividness of visual imagery questionnaire scores and their relationship to visual short-term memory performance. Cortex, 146, 186-199.

- Pertzov Y., Miller T.D., Gorgoraptis N., Caine D., Schott J.M., Butler C., et al. Binding deficits in memory following medial temporal lobe damage in patients with voltage-gated potassium channel complex antibody-associated limbic encephalitis. Brain. 2013;136(8):2474–2485.

- Zokaei N., Grogan J., Fallon S.J., Slavkova E., Hadida J., Manohar S., et al. Short-term memory advantage for brief durations in human APOE ε4 carriers. Scientific Reports. 2020;10(1):1–10.

- Patenaude B., Smith S.M., Kennedy D.N., Jenkinson M. A Bayesian model of shape and appearance for subcortical brain segmentation. Neuroimage. 2011;56(3):907–922.

- Crawford, J.R & Garthwaite, P.H. (2007). Comparison of a single case to a control or normative sample in neuropsychology: Development of a Bayesian approach. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 24, 343-372.

- Perlaki, Gabor, et al. “Are there any gender differences in the hippocampus volume after head-size correction? A volumetric and voxel-based morphometric study.” Neuroscience letters 570 (2014): 119-123.

- Dahmani, Louisa, et al. “Fimbria-fornix volume is associated with spatial memory and olfactory identification in humans.” Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience 13 (2020): 87.

- Bainbridge, Wilma A., et al. “Quantifying aphantasia through drawing: Those without visual imagery show deficits in object but not spatial memory.” Cortex 135 (2021): 159-172.

| 1 | The methods, participants, data collection and curation used in the preparation of this article were contributed by Tabi et al. (2022) at the University of Oxford and are available at: https://osf.io/q37vn/ Full details are available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0010945221003488. Younes Adam Tabi kindly gave permission for this re-analysis but did not participate in the analyses or writing of this article. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).