Submitted:

30 April 2025

Posted:

02 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

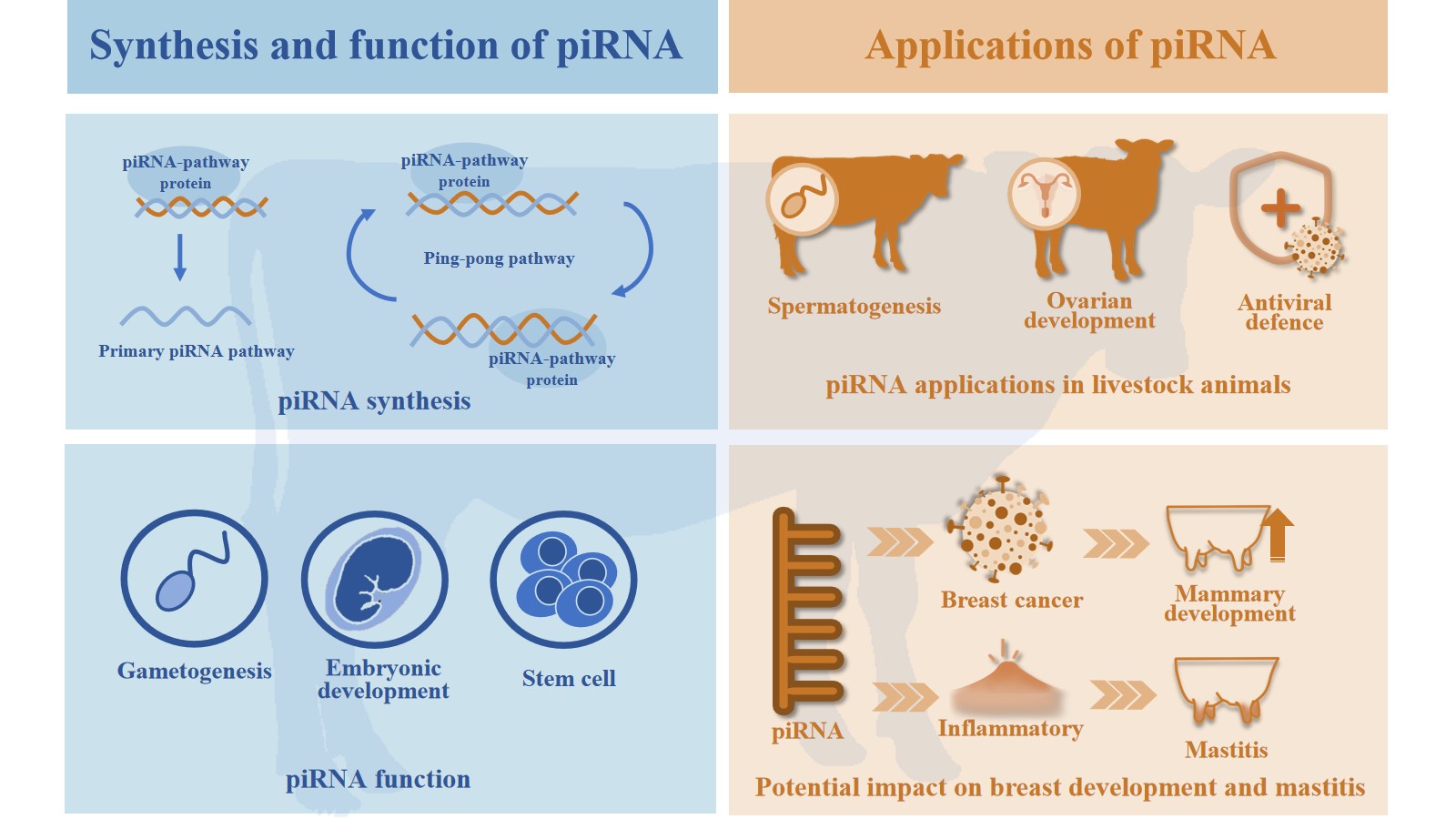

1. Introduction

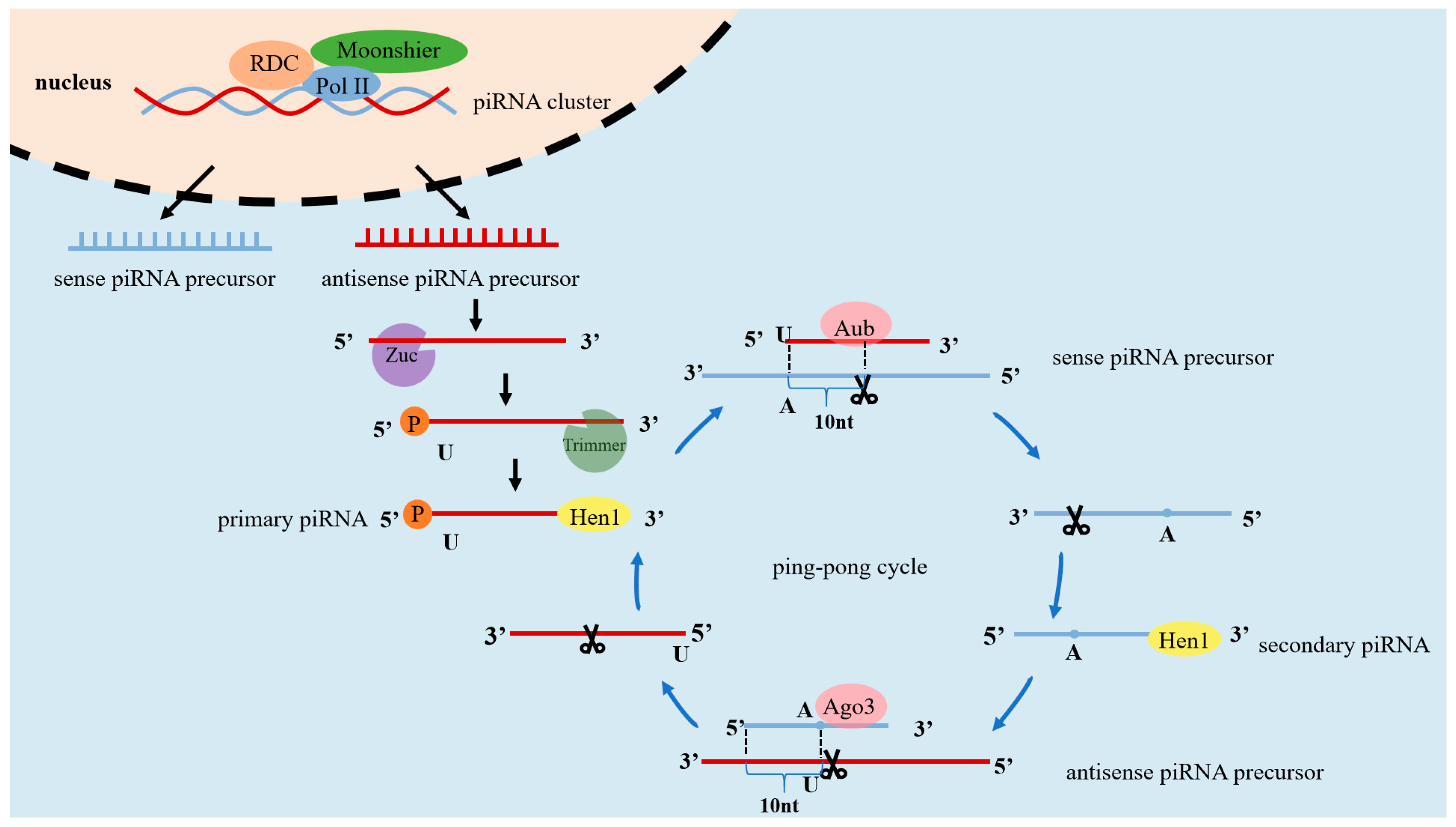

2. The Process of Generating piRNAs

2.1. Primary Processing

2.2. Secondary Amplification

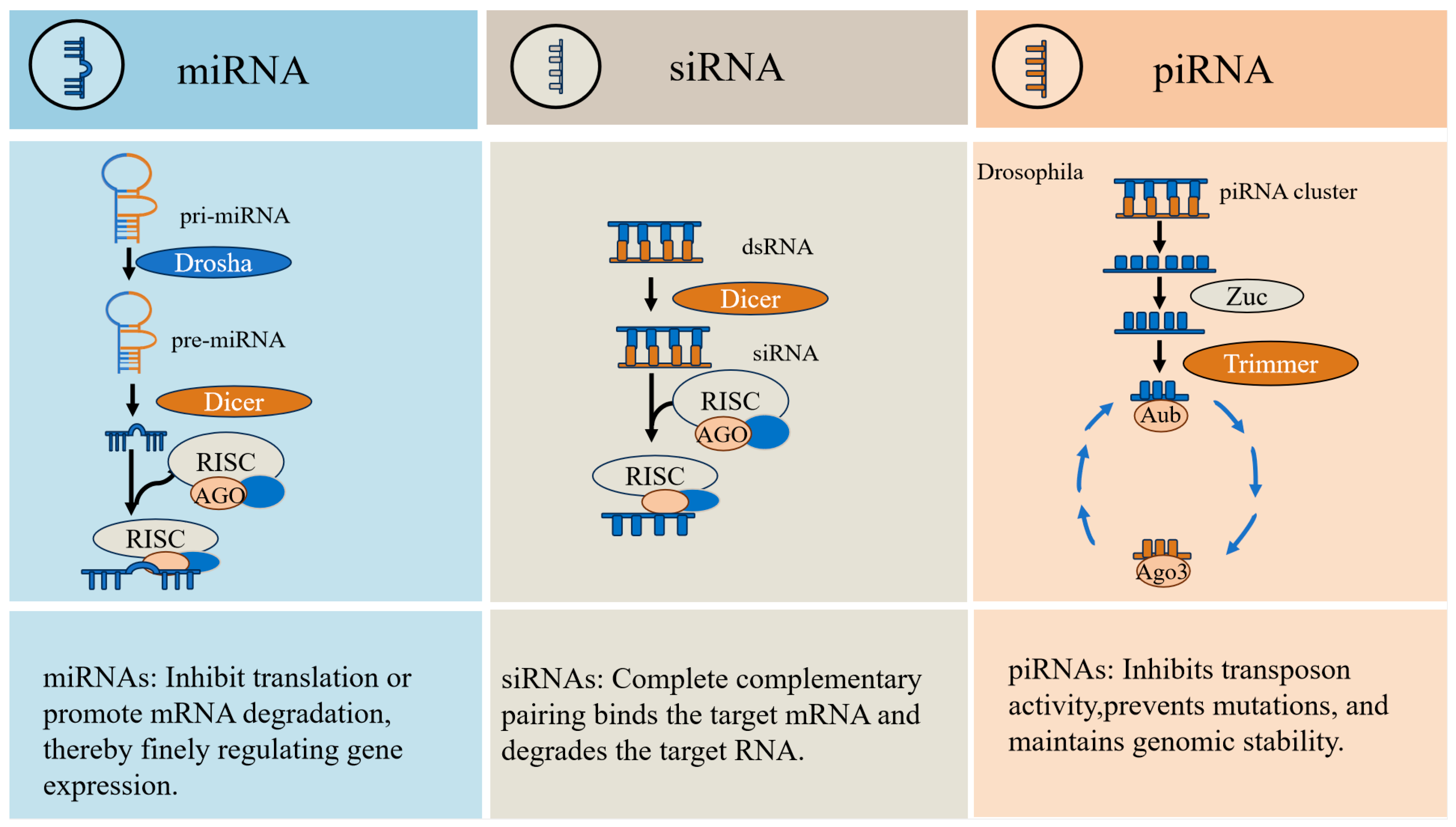

3. Characteristics and Functions of piRNAs

3.1. The Characteristics of piRNAs

3.2. The Role of piRNAs in Silencing Transposons and Stabilizing Genomes

3.3. Physiological Functions of piRNAs

3.4. Factors Regulating piRNAs

4. Characteristics of Mammary Gland Development

4.1. The Role of ncRNAs in Mammary Gland Development

4.2. Prospects for piRNAs in Livestock Animals

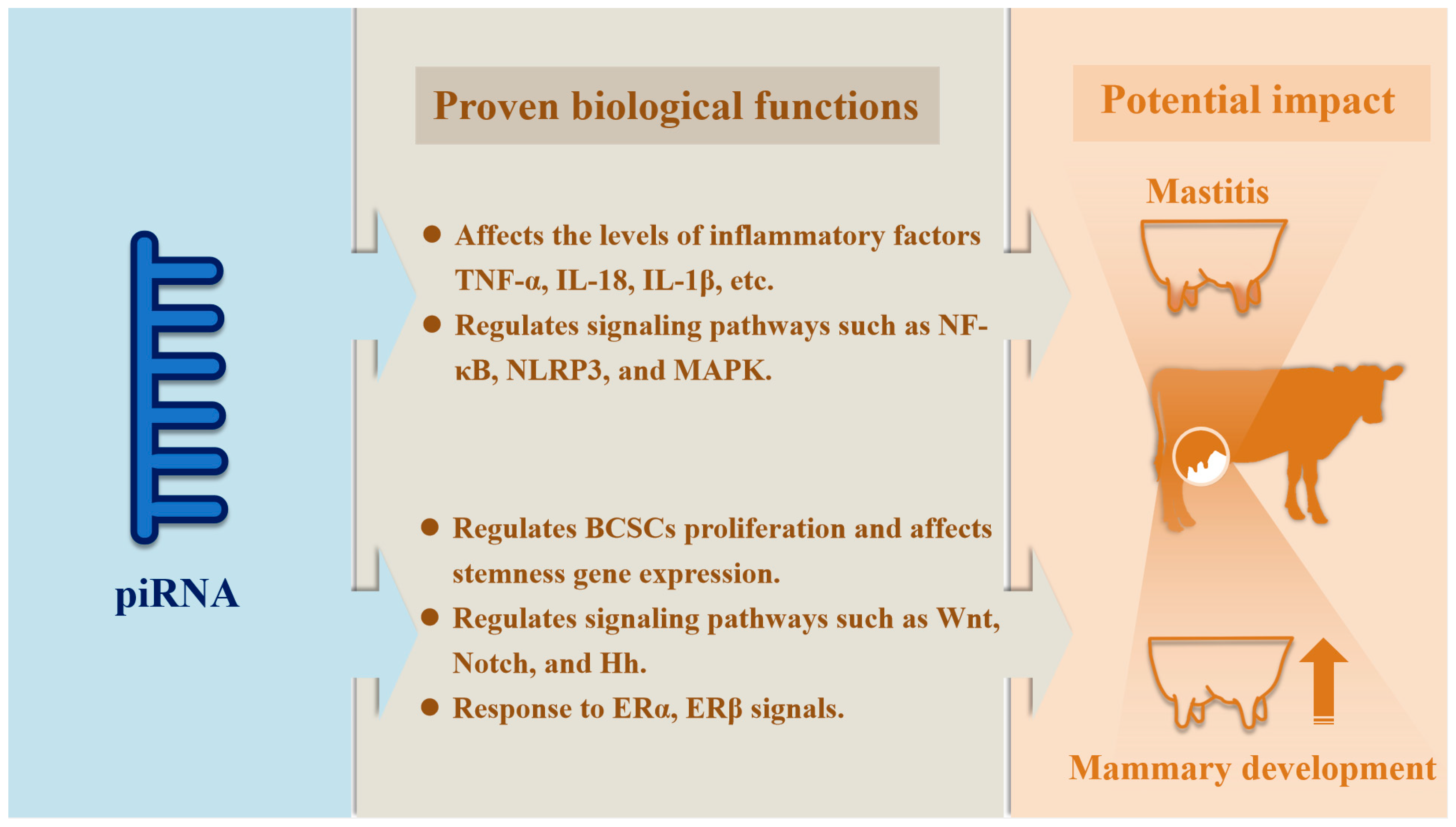

5. The Role of piRNAs in Breast Cancer

6. The Role of piRNAs in Inflammation

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thompson, R.P.; Nilsson, E.; Skinner, M.K. Environmental epigenetics and epigenetic inheritance in domestic farm animals. Anim Reprod Sci 2020, 220, 106316. [CrossRef]

- Ibeagha-Awemu, E.M.; Khatib, H. Epigenetics of livestock health, production, and breeding. In Handbook of epigenetics; Elsevier: 2023; pp. 569-610.

- Do, D.N.; Suravajhala, P. Editorial: Role of Non-Coding RNAs in Animals. Animals (Basel) 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Vagin, V.V.; Sigova, A.; Li, C.; Seitz, H.; Gvozdev, V.; Zamore, P.D. A distinct small RNA pathway silences selfish genetic elements in the germline. Science 2006, 313, 320-324. [CrossRef]

- Aravin, A.; Gaidatzis, D.; Pfeffer, S.; Lagos-Quintana, M.; Landgraf, P.; Iovino, N.; Morris, P.; Brownstein, M.J.; Kuramochi-Miyagawa, S.; Nakano, T.; et al. A novel class of small RNAs bind to MILI protein in mouse testes. Nature 2006, 442, 203-207. [CrossRef]

- Girard, A.; Sachidanandam, R.; Hannon, G.J.; Carmell, M.A. A germline-specific class of small RNAs binds mammalian Piwi proteins. Nature 2006, 442, 199-202. [CrossRef]

- Grivna, S.T.; Beyret, E.; Wang, Z.; Lin, H. A novel class of small RNAs in mouse spermatogenic cells. Genes Dev 2006, 20, 1709-1714. [CrossRef]

- Lau, N.C.; Seto, A.G.; Kim, J.; Kuramochi-Miyagawa, S.; Nakano, T.; Bartel, D.P.; Kingston, R.E. Characterization of the piRNA complex from rat testes. Science 2006, 313, 363-367. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Ren, Y.; Xu, H.; Pang, D.; Duan, C.; Liu, C. The expression of stem cell protein Piwil2 and piR-932 in breast cancer. Surg Oncol 2013, 22, 217-223. [CrossRef]

- Chuma, S.; Nakano, T. piRNA and spermatogenesis in mice. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2013, 368, 20110338. [CrossRef]

- Chalbatani, G.M.; Dana, H.; Memari, F.; Gharagozlou, E.; Ashjaei, S.; Kheirandish, P.; Marmari, V.; Mahmoudzadeh, H.; Mozayani, F.; Maleki, A.R.; et al. Biological function and molecular mechanism of piRNA in cancer. Pract Lab Med 2019, 13, e00113. [CrossRef]

- Trzybulska, D.; Vergadi, E.; Tsatsanis, C. miRNA and Other Non-Coding RNAs as Promising Diagnostic Markers. Ejifcc 2018, 29, 221-226.

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, W.; Li, R.; Gu, J.; Wu, P.; Peng, C.; Ma, J.; Wu, L.; Yu, Y.; Huang, Y. Structural insights into the sequence-specific recognition of Piwi by Drosophila Papi. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018, 115, 3374-3379. [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, Y.W.; Siomi, M.C.; Siomi, H. PIWI-Interacting RNA: Its Biogenesis and Functions. Annu Rev Biochem 2015, 84, 405-433. [CrossRef]

- Djikeng, A.; Shi, H.; Tschudi, C.; Ullu, E. RNA interference in Trypanosoma brucei: cloning of small interfering RNAs provides evidence for retroposon-derived 24-26-nucleotide RNAs. Rna 2001, 7, 1522-1530.

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, A.; Liu, Z.; He, Z.; Yuan, X.; Tuo, S. Prediction of cancer-associated piRNA–mRNA and piRNA–lncRNA interactions by integrated analysis of expression and sequence data. Tsinghua Science and Technology 2018, 23, 115-125.

- Goriaux, C.; Desset, S.; Renaud, Y.; Vaury, C.; Brasset, E. Transcriptional properties and splicing of the flamenco piRNA cluster. EMBO Rep 2014, 15, 411-418. [CrossRef]

- Ipsaro, J.J.; Haase, A.D.; Knott, S.R.; Joshua-Tor, L.; Hannon, G.J. The structural biochemistry of Zucchini implicates it as a nuclease in piRNA biogenesis. Nature 2012, 491, 279-283. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Tu, Y.X.; Ye, D.; Gu, Z.; Chen, Z.X.; Sun, Y. A Germline-Specific Regulator of Mitochondrial Fusion is Required for Maintenance and Differentiation of Germline Stem and Progenitor Cells. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2022, 9, e2203631. [CrossRef]

- Saito, K.; Ishizu, H.; Komai, M.; Kotani, H.; Kawamura, Y.; Nishida, K.M.; Siomi, H.; Siomi, M.C. Roles for the Yb body components Armitage and Yb in primary piRNA biogenesis in Drosophila. Genes Dev 2010, 24, 2493-2498. [CrossRef]

- Andersen, P.R.; Tirian, L.; Vunjak, M.; Brennecke, J. A heterochromatin-dependent transcription machinery drives piRNA expression. Nature 2017, 549, 54-59. [CrossRef]

- Pastore, B.; Hertz, H.L.; Tang, W. Comparative analysis of piRNA sequences, targets and functions in nematodes. RNA Biol 2022, 19, 1276-1292. [CrossRef]

- Houwing, S.; Kamminga, L.M.; Berezikov, E.; Cronembold, D.; Girard, A.; van den Elst, H.; Filippov, D.V.; Blaser, H.; Raz, E.; Moens, C.B.; et al. A role for Piwi and piRNAs in germ cell maintenance and transposon silencing in Zebrafish. Cell 2007, 129, 69-82. [CrossRef]

- Houwing, S.; Berezikov, E.; Ketting, R.F. Zili is required for germ cell differentiation and meiosis in zebrafish. Embo j 2008, 27, 2702-2711. [CrossRef]

- Brennecke, J.; Aravin, A.A.; Stark, A.; Dus, M.; Kellis, M.; Sachidanandam, R.; Hannon, G.J. Discrete small RNA-generating loci as master regulators of transposon activity in Drosophila. Cell 2007, 128, 1089-1103. [CrossRef]

- Hirakata, S.; Siomi, M.C. piRNA biogenesis in the germline: From transcription of piRNA genomic sources to piRNA maturation. Biochim Biophys Acta 2016, 1859, 82-92. [CrossRef]

- Grivna, S.T.; Pyhtila, B.; Lin, H. MIWI associates with translational machinery and PIWI-interacting RNAs (piRNAs) in regulating spermatogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006, 103, 13415-13420. [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, T.; Takeda, A.; Tsukiyama, T.; Mise, K.; Okuno, T.; Sasaki, H.; Minami, N.; Imai, H. Identification and characterization of two novel classes of small RNAs in the mouse germline: retrotransposon-derived siRNAs in oocytes and germline small RNAs in testes. Genes Dev 2006, 20, 1732-1743. [CrossRef]

- Ding, D.; Liu, J.; Dong, K.; Midic, U.; Hess, R.A.; Xie, H.; Demireva, E.Y.; Chen, C. PNLDC1 is essential for piRNA 3' end trimming and transposon silencing during spermatogenesis in mice. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 819. [CrossRef]

- Saito, K.; Sakaguchi, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Suzuki, T.; Siomi, H.; Siomi, M.C. Pimet, the Drosophila homolog of HEN1, mediates 2'-O-methylation of Piwi- interacting RNAs at their 3' ends. Genes Dev 2007, 21, 1603-1608. [CrossRef]

- Gunawardane, L.S.; Saito, K.; Nishida, K.M.; Miyoshi, K.; Kawamura, Y.; Nagami, T.; Siomi, H.; Siomi, M.C. A slicer-mediated mechanism for repeat-associated siRNA 5' end formation in Drosophila. Science 2007, 315, 1587-1590. [CrossRef]

- Olivieri, D.; Senti, K.A.; Subramanian, S.; Sachidanandam, R.; Brennecke, J. The cochaperone shutdown defines a group of biogenesis factors essential for all piRNA populations in Drosophila. Mol Cell 2012, 47, 954-969. [CrossRef]

- Horwich, M.D.; Li, C.; Matranga, C.; Vagin, V.; Farley, G.; Wang, P.; Zamore, P.D. The Drosophila RNA methyltransferase, DmHen1, modifies germline piRNAs and single-stranded siRNAs in RISC. Curr Biol 2007, 17, 1265-1272. [CrossRef]

- Handler, D.; Olivieri, D.; Novatchkova, M.; Gruber, F.S.; Meixner, K.; Mechtler, K.; Stark, A.; Sachidanandam, R.; Brennecke, J. A systematic analysis of Drosophila TUDOR domain-containing proteins identifies Vreteno and the Tdrd12 family as essential primary piRNA pathway factors. Embo j 2011, 30, 3977-3993. [CrossRef]

- Ozata, D.M.; Gainetdinov, I.; Zoch, A.; O'Carroll, D.; Zamore, P.D. PIWI-interacting RNAs: small RNAs with big functions. Nat Rev Genet 2019, 20, 89-108. [CrossRef]

- Rouget, C.; Papin, C.; Boureux, A.; Meunier, A.C.; Franco, B.; Robine, N.; Lai, E.C.; Pelisson, A.; Simonelig, M. Maternal mRNA deadenylation and decay by the piRNA pathway in the early Drosophila embryo. Nature 2010, 467, 1128-1132. [CrossRef]

- Gou, L.T.; Dai, P.; Yang, J.H.; Xue, Y.; Hu, Y.P.; Zhou, Y.; Kang, J.Y.; Wang, X.; Li, H.; Hua, M.M.; et al. Pachytene piRNAs instruct massive mRNA elimination during late spermiogenesis. Cell Res 2014, 24, 680-700. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, H.; Benson, M.; Han, X.; Li, D. Roles of piRNAs in microcystin-leucine-arginine (MC-LR) induced reproductive toxicity in testis on male offspring. Food Chem Toxicol 2017, 105, 177-185. [CrossRef]

- Donkin, I.; Barrès, R. Sperm epigenetics and influence of environmental factors. Mol Metab 2018, 14, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Bartel, D.P. Metazoan MicroRNAs. Cell 2018, 173, 20-51. [CrossRef]

- Santos, D.; Mingels, L.; Vogel, E.; Wang, L.; Christiaens, O.; Cappelle, K.; Wynant, N.; Gansemans, Y.; Van Nieuwerburgh, F.; Smagghe, G.; et al. Generation of Virus- and dsRNA-Derived siRNAs with Species-Dependent Length in Insects. Viruses 2019, 11. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Ding, C.; Chu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Guo, G.; Chen, J.; Su, X. Pln24NT: a web resource for plant 24-nt siRNA producing loci. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 2065-2067. [CrossRef]

- Swarts, D.C.; Makarova, K.; Wang, Y.; Nakanishi, K.; Ketting, R.F.; Koonin, E.V.; Patel, D.J.; van der Oost, J. The evolutionary journey of Argonaute proteins. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2014, 21, 743-753. [CrossRef]

- Tolia, N.H.; Joshua-Tor, L. Slicer and the argonautes. Nat Chem Biol 2007, 3, 36-43. [CrossRef]

- Peters, L.; Meister, G. Argonaute proteins: mediators of RNA silencing. Mol Cell 2007, 26, 611-623. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Ke, A. PIWI Takes a Giant Step. Cell 2016, 167, 310-312. [CrossRef]

- Aravin, A.A.; Sachidanandam, R.; Girard, A.; Fejes-Toth, K.; Hannon, G.J. Developmentally regulated piRNA clusters implicate MILI in transposon control. Science 2007, 316, 744-747. [CrossRef]

- Nishida, K.M.; Saito, K.; Mori, T.; Kawamura, Y.; Nagami-Okada, T.; Inagaki, S.; Siomi, H.; Siomi, M.C. Gene silencing mechanisms mediated by Aubergine piRNA complexes in Drosophila male gonad. Rna 2007, 13, 1911-1922. [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Fan, G.; Song, S.; Jiang, Y.; Qian, C.; Zhang, W.; Su, Q.; Xue, X.; Zhuang, W.; Li, B. piRNA-30473 contributes to tumorigenesis and poor prognosis by regulating m6A RNA methylation in DLBCL. Blood 2021, 137, 1603-1614. [CrossRef]

- Gebert, L.F.R.; MacRae, I.J. Regulation of microRNA function in animals. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2019, 20, 21-37. [CrossRef]

- Dana, H.; Chalbatani, G.M.; Mahmoodzadeh, H.; Karimloo, R.; Rezaiean, O.; Moradzadeh, A.; Mehmandoost, N.; Moazzen, F.; Mazraeh, A.; Marmari, V.; et al. Molecular Mechanisms and Biological Functions of siRNA. Int J Biomed Sci 2017, 13, 48-57.

- Lee, H.C.; Gu, W.; Shirayama, M.; Youngman, E.; Conte, D., Jr.; Mello, C.C. C. elegans piRNAs mediate the genome-wide surveillance of germline transcripts. Cell 2012, 150, 78-87. [CrossRef]

- Batista, P.J.; Ruby, J.G.; Claycomb, J.M.; Chiang, R.; Fahlgren, N.; Kasschau, K.D.; Chaves, D.A.; Gu, W.; Vasale, J.J.; Duan, S.; et al. PRG-1 and 21U-RNAs interact to form the piRNA complex required for fertility in C. elegans. Mol Cell 2008, 31, 67-78. [CrossRef]

- Suen, K.M.; Braukmann, F.; Butler, R.; Bensaddek, D.; Akay, A.; Lin, C.C.; Milonaitytė, D.; Doshi, N.; Sapetschnig, A.; Lamond, A.; et al. DEPS-1 is required for piRNA-dependent silencing and PIWI condensate organisation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 4242. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Bogoch, Y.; Shvaizer, G.; Guler, N.; Levy, K.; Elkouby, Y.M. The piRNA protein Asz1 is essential for germ cell and gonad development in zebrafish and exhibits differential necessities in distinct types of germ granules. PLoS Genet 2025, 21, e1010868. [CrossRef]

- Sienski, G.; Dönertas, D.; Brennecke, J. Transcriptional silencing of transposons by Piwi and maelstrom and its impact on chromatin state and gene expression. Cell 2012, 151, 964-980. [CrossRef]

- Kuramochi-Miyagawa, S.; Watanabe, T.; Gotoh, K.; Totoki, Y.; Toyoda, A.; Ikawa, M.; Asada, N.; Kojima, K.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Ijiri, T.W.; et al. DNA methylation of retrotransposon genes is regulated by Piwi family members MILI and MIWI2 in murine fetal testes. Genes Dev 2008, 22, 908-917. [CrossRef]

- Carmell, M.A.; Girard, A.; van de Kant, H.J.; Bourc'his, D.; Bestor, T.H.; de Rooij, D.G.; Hannon, G.J. MIWI2 is essential for spermatogenesis and repression of transposons in the mouse male germline. Dev Cell 2007, 12, 503-514. [CrossRef]

- Ashe, A.; Sapetschnig, A.; Weick, E.M.; Mitchell, J.; Bagijn, M.P.; Cording, A.C.; Doebley, A.L.; Goldstein, L.D.; Lehrbach, N.J.; Le Pen, J.; et al. piRNAs can trigger a multigenerational epigenetic memory in the germline of C. elegans. Cell 2012, 150, 88-99. [CrossRef]

- Klenov, M.S.; Sokolova, O.A.; Yakushev, E.Y.; Stolyarenko, A.D.; Mikhaleva, E.A.; Lavrov, S.A.; Gvozdev, V.A. Separation of stem cell maintenance and transposon silencing functions of Piwi protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011, 108, 18760-18765. [CrossRef]

- Le Thomas, A.; Rogers, A.K.; Webster, A.; Marinov, G.K.; Liao, S.E.; Perkins, E.M.; Hur, J.K.; Aravin, A.A.; Tóth, K.F. Piwi induces piRNA-guided transcriptional silencing and establishment of a repressive chromatin state. Genes Dev 2013, 27, 390-399. [CrossRef]

- Pezic, D.; Manakov, S.A.; Sachidanandam, R.; Aravin, A.A. piRNA pathway targets active LINE1 elements to establish the repressive H3K9me3 mark in germ cells. Genes Dev 2014, 28, 1410-1428. [CrossRef]

- Khurana, J.S.; Xu, J.; Weng, Z.; Theurkauf, W.E. Distinct functions for the Drosophila piRNA pathway in genome maintenance and telomere protection. PLoS Genet 2010, 6, e1001246. [CrossRef]

- Pek, J.W.; Kai, T. DEAD-box RNA helicase Belle/DDX3 and the RNA interference pathway promote mitotic chromosome segregation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011, 108, 12007-12012. [CrossRef]

- Cox, D.N.; Chao, A.; Lin, H. piwi encodes a nucleoplasmic factor whose activity modulates the number and division rate of germline stem cells. Development 2000, 127, 503-514. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Gao, Q.; Peng, X.; Choi, S.Y.; Sarma, K.; Ren, H.; Morris, A.J.; Frohman, M.A. piRNA-associated germline nuage formation and spermatogenesis require MitoPLD profusogenic mitochondrial-surface lipid signaling. Dev Cell 2011, 20, 376-387. [CrossRef]

- Loubalova, Z.; Fulka, H.; Horvat, F.; Pasulka, J.; Malik, R.; Hirose, M.; Ogura, A.; Svoboda, P. Formation of spermatogonia and fertile oocytes in golden hamsters requires piRNAs. Nat Cell Biol 2021, 23, 992-1001. [CrossRef]

- Casier, K.; Delmarre, V.; Gueguen, N.; Hermant, C.; Viodé, E.; Vaury, C.; Ronsseray, S.; Brasset, E.; Teysset, L.; Boivin, A. Environmentally-induced epigenetic conversion of a piRNA cluster. Elife 2019, 8. [CrossRef]

- Belicard, T.; Jareosettasin, P.; Sarkies, P. The piRNA pathway responds to environmental signals to establish intergenerational adaptation to stress. BMC Biol 2018, 16, 103. [CrossRef]

- Donkin, I.; Versteyhe, S.; Ingerslev, L.R.; Qian, K.; Mechta, M.; Nordkap, L.; Mortensen, B.; Appel, E.V.; Jørgensen, N.; Kristiansen, V.B.; et al. Obesity and Bariatric Surgery Drive Epigenetic Variation of Spermatozoa in Humans. Cell Metab 2016, 23, 369-378. [CrossRef]

- Grandjean, V.; Fourré, S.; De Abreu, D.A.; Derieppe, M.A.; Remy, J.J.; Rassoulzadegan, M. RNA-mediated paternal heredity of diet-induced obesity and metabolic disorders. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 18193. [CrossRef]

- de Castro Barbosa, T.; Ingerslev, L.R.; Alm, P.S.; Versteyhe, S.; Massart, J.; Rasmussen, M.; Donkin, I.; Sjögren, R.; Mudry, J.M.; Vetterli, L.; et al. High-fat diet reprograms the epigenome of rat spermatozoa and transgenerationally affects metabolism of the offspring. Mol Metab 2016, 5, 184-197. [CrossRef]

- Ingerslev, L.R.; Donkin, I.; Fabre, O.; Versteyhe, S.; Mechta, M.; Pattamaprapanont, P.; Mortensen, B.; Krarup, N.T.; Barrès, R. Endurance training remodels sperm-borne small RNA expression and methylation at neurological gene hotspots. Clin Epigenetics 2018, 10, 12. [CrossRef]

- Gapp, K.; Jawaid, A.; Sarkies, P.; Bohacek, J.; Pelczar, P.; Prados, J.; Farinelli, L.; Miska, E.; Mansuy, I.M. Implication of sperm RNAs in transgenerational inheritance of the effects of early trauma in mice. Nat Neurosci 2014, 17, 667-669. [CrossRef]

- Han, R.; Zhang, L.; Gan, W.; Fu, K.; Jiang, K.; Ding, J.; Wu, J.; Han, X.; Li, D. piRNA-DQ722010 contributes to prostate hyperplasia of the male offspring mice after the maternal exposed to microcystin-leucine arginine. Prostate 2019, 79, 798-812. [CrossRef]

- Hurley, W.L. Review: Mammary gland development in swine: embryo to early lactation. Animal 2019, 13, s11-s19. [CrossRef]

- Hue-Beauvais, C.; Faulconnier, Y.; Charlier, M.; Leroux, C. Nutritional Regulation of Mammary Gland Development and Milk Synthesis in Animal Models and Dairy Species. Genes (Basel) 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Davis, S.R. TRIENNIAL LACTATION SYMPOSIUM/BOLFA: Mammary growth during pregnancy and lactation and its relationship with milk yield. J Anim Sci 2017, 95, 5675-5688. [CrossRef]

- Akers, R.M.; Nickerson, S.C. Mastitis and its impact on structure and function in the ruminant mammary gland. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia 2011, 16, 275-289. [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Cao, X.; Lv, X.; Yang, Z.; Chen, Z. Progress in Research on Key Factors Regulating Lactation Initiation in the Mammary Glands of Dairy Cows. Genes (Basel) 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- O'Brien, J.; Hayder, H.; Zayed, Y.; Peng, C. Overview of MicroRNA Biogenesis, Mechanisms of Actions, and Circulation. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2018, 9, 402. [CrossRef]

- Ibarra, I.; Erlich, Y.; Muthuswamy, S.K.; Sachidanandam, R.; Hannon, G.J. A role for microRNAs in maintenance of mouse mammary epithelial progenitor cells. Genes Dev 2007, 21, 3238-3243. [CrossRef]

- Feuermann, Y.; Kang, K.; Shamay, A.; Robinson, G.W.; Hennighausen, L. MiR-21 is under control of STAT5 but is dispensable for mammary development and lactation. PLoS One 2014, 9, e85123. [CrossRef]

- Le Guillou, S.; Sdassi, N.; Laubier, J.; Passet, B.; Vilotte, M.; Castille, J.; Laloë, D.; Polyte, J.; Bouet, S.; Jaffrézic, F.; et al. Overexpression of miR-30b in the developing mouse mammary gland causes a lactation defect and delays involution. PLoS One 2012, 7, e45727. [CrossRef]

- Lv, C.; Li, F.; Li, X.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Sheng, X.; Song, Y.; Meng, Q.; Yuan, S.; Luan, L.; et al. Author Correction: MiR-31 promotes mammary stem cell expansion and breast tumorigenesis by suppressing Wnt signaling antagonists. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 5308. [CrossRef]

- Bonetti, P.; Climent, M.; Panebianco, F.; Tordonato, C.; Santoro, A.; Marzi, M.J.; Pelicci, P.G.; Ventura, A.; Nicassio, F. Correction: Dual role for miR-34a in the control of early progenitor proliferation and commitment in the mammary gland and in breast cancer. Oncogene 2020, 39, 2228. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Haneda, S.; Imakawa, K.; Sakai, S.; Nagaoka, K. A microRNA, miR-101a, controls mammary gland development by regulating cyclooxygenase-2 expression. Differentiation 2009, 77, 181-187. [CrossRef]

- Ucar, A.; Vafaizadeh, V.; Jarry, H.; Fiedler, J.; Klemmt, P.A.; Thum, T.; Groner, B.; Chowdhury, K. miR-212 and miR-132 are required for epithelial stromal interactions necessary for mouse mammary gland development. Nat Genet 2010, 42, 1101-1108. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.M.; Cho, K.W.; Kim, E.J.; Tang, Q.; Kim, K.S.; Tickle, C.; Jung, H.S. A contrasting function for miR-137 in embryonic mammogenesis and adult breast carcinogenesis. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 22048-22059. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; LI, Q.; LI, Y. miR-138 function and its targets on mouse mammary epithelial cells. Progress in Biochemistry and Biophysics 2006.

- Cui, Y.; Sun, X.; Jin, L.; Yu, G.; Li, Q.; Gao, X.; Ao, J.; Wang, C. MiR-139 suppresses β-casein synthesis and proliferation in bovine mammary epithelial cells by targeting the GHR and IGF1R signaling pathways. BMC Vet Res 2017, 13, 350. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Wu, C.; Li, Y.; Liu, J.; Yuan, Y.; Shi, H. Identification and profiling of microRNAs involved in the regenerative involution of mammary gland. Genomics 2022, 114, 110442. [CrossRef]

- Yoo, K.H.; Kang, K.; Feuermann, Y.; Jang, S.J.; Robinson, G.W.; Hennighausen, L. The STAT5-regulated miR-193b locus restrains mammary stem and progenitor cell activity and alveolar differentiation. Dev Biol 2014, 395, 245-254. [CrossRef]

- Shimono, Y.; Zabala, M.; Cho, R.W.; Lobo, N.; Dalerba, P.; Qian, D.; Diehn, M.; Liu, H.; Panula, S.P.; Chiao, E.; et al. Downregulation of miRNA-200c links breast cancer stem cells with normal stem cells. Cell 2009, 138, 592-603. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Cao, J.; Napoli, M.; Xia, Z.; Zhao, N.; Creighton, C.J.; Li, W.; Chen, X.; Flores, E.R.; McManus, M.T.; et al. miR-205 Regulates Basal Cell Identity and Stem Cell Regenerative Potential During Mammary Reconstitution. Stem Cells 2018, 36, 1875-1889. [CrossRef]

- Patel, Y.; Soni, M.; Awgulewitsch, A.; Kern, M.J.; Liu, S.; Shah, N.; Singh, U.P.; Chen, H. Correction: Overexpression of miR-489 derails mammary hierarchy structure and inhibits HER2/neu-induced tumorigenesis. Oncogene 2019, 38, 454. [CrossRef]

- Chu, M.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, S.; Hao, Y.; Zhang, P.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ma, D.; Liu, J.; Cheng, M.; et al. miR-15b negatively correlates with lipid metabolism in mammary epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2018, 314, C43-c52. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Luo, J.; Sun, S.; Cao, D.; Shi, H.; Loor, J.J. miR-148a and miR-17-5p synergistically regulate milk TAG synthesis via PPARGC1A and PPARA in goat mammary epithelial cells. RNA Biol 2017, 14, 326-338. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Luo, J.; Chen, Z.; Cao, W.T.; Xu, H.F.; Gou, D.M.; Zhu, J.J. MicroRNA-24 can control triacylglycerol synthesis in goat mammary epithelial cells by targeting the fatty acid synthase gene. J Dairy Sci 2015, 98, 9001-9014. [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Qiu, H.; Chen, Z.; Li, L.; Zeng, Y.; Luo, J.; Gou, D. miR-25 modulates triacylglycerol and lipid accumulation in goat mammary epithelial cells by repressing PGC-1beta. J Anim Sci Biotechnol 2018, 9, 48. [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.Z.; Luo, J.; Zhang, L.P.; Wang, W.; Shi, H.B.; Zhu, J.J. MiR-27a suppresses triglyceride accumulation and affects gene mRNA expression associated with fat metabolism in dairy goat mammary gland epithelial cells. Gene 2013, 521, 15-23. [CrossRef]

- Bian, Y.; Lei, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, J.; Wang, L.; Liu, L.; Liu, L.; Gao, X.; Li, Q. Epigenetic Regulation of miR-29s Affects the Lactation Activity of Dairy Cow Mammary Epithelial Cells. J Cell Physiol 2015, 230, 2152-2163. [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Luo, J.; Zhang, L.; Wang, W.; Gou, D. MiR-103 controls milk fat accumulation in goat (Capra hircus) mammary gland during lactation. PLoS One 2013, 8, e79258. [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.; Li, Q.; Feng, L.; Ding, W. MiR-126-3p regulates progesterone receptors and involves development and lactation of mouse mammary gland. Mol Cell Biochem 2011, 355, 17-25. [CrossRef]

- Chu, M.; Zhao, Y.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, H.; Liu, J.; Cheng, M.; Li, L.; Shen, W.; Cao, H.; Li, Q.; et al. MicroRNA-126 participates in lipid metabolism in mammary epithelial cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2017, 454, 77-86. [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Zhang, L.; Cui, Y.; Li, H.; Xie, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, C. miR-142-3p Regulates Milk Synthesis and Structure of Murine Mammary Glands via PRLR-Mediated Multiple Signaling Pathways. J Agric Food Chem 2019, 67, 9532-9542. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Shi, H.; Luo, J.; Yi, Y.; Yao, D.; Zhang, X.; Ma, G.; Loor, J.J. MiR-145 Regulates Lipogenesis in Goat Mammary Cells Via Targeting INSIG1 and Epigenetic Regulation of Lipid-Related Genes. J Cell Physiol 2017, 232, 1030-1040. [CrossRef]

- Heinz, R.E.; Rudolph, M.C.; Ramanathan, P.; Spoelstra, N.S.; Butterfield, K.T.; Webb, P.G.; Babbs, B.L.; Gao, H.; Chen, S.; Gordon, M.A.; et al. Constitutive expression of microRNA-150 in mammary epithelium suppresses secretory activation and impairs de novo lipogenesis. Development 2016, 143, 4236-4248. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Shi, H.; Sun, S.; Xu, H.; Cao, D.; Luo, J. MicroRNA-181b suppresses TAG via target IRS2 and regulating multiple genes in the Hippo pathway. Exp Cell Res 2016, 348, 66-74. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Cao, M.; Kong, L.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Song, C.; Chen, X.; Lai, M.; Fang, X.; Chen, H.; et al. MiR-204-5p promotes lipid synthesis in mammary epithelial cells by targeting SIRT1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2020, 533, 1490-1496. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Aydoğdu, E.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Helguero, L.A.; Williams, C. A miR-206 regulated gene landscape enhances mammary epithelial differentiation. J Cell Physiol 2019, 234, 22220-22233. [CrossRef]

- Chu, M.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, S.; Hao, Y.; Zhang, P.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ma, D.; Liu, J.; Cheng, M.; et al. MicroRNA-221 may be involved in lipid metabolism in mammary epithelial cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2018, 97, 118-127. [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Xie, X.; Wang, J.; Bian, Y.; Li, Q.; Gao, X.; Wang, C. MiR-486 regulates lactation and targets the PTEN gene in cow mammary glands. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0118284. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Dong, J.; Li, D.; Lai, L.; Siwko, S.; Li, Y.; Liu, M. Lgr4 regulates mammary gland development and stem cell activity through the pluripotency transcription factor Sox2. Stem Cells 2013, 31, 1921-1931. [CrossRef]

- Lanz, R.B.; Chua, S.S.; Barron, N.; Söder, B.M.; DeMayo, F.; O'Malley, B.W. Steroid receptor RNA activator stimulates proliferation as well as apoptosis in vivo. Mol Cell Biol 2003, 23, 7163-7176. [CrossRef]

- Askarian-Amiri, M.E.; Crawford, J.; French, J.D.; Smart, C.E.; Smith, M.A.; Clark, M.B.; Ru, K.; Mercer, T.R.; Thompson, E.R.; Lakhani, S.R.; et al. SNORD-host RNA Zfas1 is a regulator of mammary development and a potential marker for breast cancer. Rna 2011, 17, 878-891. [CrossRef]

- Adriaenssens, E.; Lottin, S.; Dugimont, T.; Fauquette, W.; Coll, J.; Dupouy, J.P.; Boilly, B.; Curgy, J.J. Steroid hormones modulate H19 gene expression in both mammary gland and uterus. Oncogene 1999, 18, 4460-4473. [CrossRef]

- Ginger, M.R.; Shore, A.N.; Contreras, A.; Rijnkels, M.; Miller, J.; Gonzalez-Rimbau, M.F.; Rosen, J.M. A noncoding RNA is a potential marker of cell fate during mammary gland development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006, 103, 5781-5786. [CrossRef]

- Shore, A.N.; Kabotyanski, E.B.; Roarty, K.; Smith, M.A.; Zhang, Y.; Creighton, C.J.; Dinger, M.E.; Rosen, J.M. Pregnancy-induced noncoding RNA (PINC) associates with polycomb repressive complex 2 and regulates mammary epithelial differentiation. PLoS Genet 2012, 8, e1002840. [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Niu, X.; Huang, S.; Li, S.; Ran, X.; Wang, J.; Dai, X. The piRNAs present in the developing testes of Chinese indigenous Xiang pigs. Theriogenology 2022, 189, 92-106. [CrossRef]

- Gebert, D.; Ketting, R.F.; Zischler, H.; Rosenkranz, D. piRNAs from Pig Testis Provide Evidence for a Conserved Role of the Piwi Pathway in Post-Transcriptional Gene Regulation in Mammals. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0124860. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.W.; Wang, L.; Chen, H.; Guan, J.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Luo, Z.; Huang, W.; Zuo, F. Promoter hypermethylation of PIWI/piRNA pathway genes associated with diminished pachytene piRNA production in bovine hybrid male sterility. Epigenetics 2020, 15, 914-931. [CrossRef]

- Capra, E.; Turri, F.; Lazzari, B.; Cremonesi, P.; Gliozzi, T.M.; Fojadelli, I.; Stella, A.; Pizzi, F. Small RNA sequencing of cryopreserved semen from single bull revealed altered miRNAs and piRNAs expression between High- and Low-motile sperm populations. BMC Genomics 2017, 18, 14. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, Z.; Ren, C.; Wang, X.; He, X.; Mwacharo, J.M.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Di, R.; et al. Expression characteristics of piRNAs in ovine luteal phase and follicular phase ovaries. Front Vet Sci 2022, 9, 921868. [CrossRef]

- Testroet, E.D.; Shome, S.; Testroet, A.; Reecy, J.; Jernigan, R.L.; Zhu, M.; Du, M.; Clark, S.; Beitz, D. Profiling of the Exosomal Cargo of Bovine Milk Reveals the Presence of Immune-and Growth-modulatory ncRNAs. The FASEB Journal 2018, 32, 747.725-747.725.

- Ablondi, M.; Gòdia, M.; Rodriguez-Gil, J.E.; Sánchez, A.; Clop, A. Characterisation of sperm piRNAs and their correlation with semen quality traits in swine. Anim Genet 2021, 52, 114-120. [CrossRef]

- Kowalczykiewicz, D.; Pawlak, P.; Lechniak, D.; Wrzesinski, J. Altered expression of porcine Piwi genes and piRNA during development. PLoS One 2012, 7, e43816. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Chen, Y.; Yang, X.; Du, Y.; Xu, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, C.; Li, S.; et al. The porcine piRNA transcriptome response to Senecavirus a infection. Front Vet Sci 2023, 10, 1126277. [CrossRef]

- Weng, B.; Ran, M.; Chen, B.; Wu, M.; Peng, F.; Dong, L.; He, C.; Zhang, S.; Li, Z. Systematic identification and characterization of miRNAs and piRNAs from porcine testes. Genes & Genomics 2017, 39, 1047-1057.

- Yang, C.X.; Du, Z.Q.; Wright, E.C.; Rothschild, M.F.; Prather, R.S.; Ross, J.W. Small RNA profile of the cumulus-oocyte complex and early embryos in the pig. Biol Reprod 2012, 87, 117. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Xie, Y.; Zhou, C.; Hu, Q.; Gu, T.; Yang, J.; Zheng, E.; Huang, S.; Xu, Z.; Cai, G.; et al. Expression Pattern of Seminal Plasma Extracellular Vesicle Small RNAs in Boar Semen. Front Vet Sci 2020, 7, 585276. [CrossRef]

- Russell, S.; Patel, M.; Gilchrist, G.; Stalker, L.; Gillis, D.; Rosenkranz, D.; LaMarre, J. Bovine piRNA-like RNAs are associated with both transposable elements and mRNAs. Reproduction 2017, 153, 305-318. [CrossRef]

- Spornraft, M.; Kirchner, B.; Pfaffl, M.W.; Riedmaier, I. Comparison of the miRNome and piRNome of bovine blood and plasma by small RNA sequencing. Biotechnol Lett 2015, 37, 1165-1176. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhong, J.; Chai, Z.; Zhu, J.; Xin, J. Comparative expression profile of microRNAs and piRNAs in three ruminant species testes using next-generation sequencing. Reprod Domest Anim 2018, 53, 963-970. [CrossRef]

- Sellem, E.; Marthey, S.; Rau, A.; Jouneau, L.; Bonnet, A.; Perrier, J.P.; Fritz, S.; Le Danvic, C.; Boussaha, M.; Kiefer, H.; et al. A comprehensive overview of bull sperm-borne small non-coding RNAs and their diversity across breeds. Epigenetics Chromatin 2020, 13, 19. [CrossRef]

- Roovers, E.F.; Rosenkranz, D.; Mahdipour, M.; Han, C.T.; He, N.; Chuva de Sousa Lopes, S.M.; van der Westerlaken, L.A.; Zischler, H.; Butter, F.; Roelen, B.A.; et al. Piwi proteins and piRNAs in mammalian oocytes and early embryos. Cell Rep 2015, 10, 2069-2082. [CrossRef]

- Sellem, E.; Marthey, S.; Rau, A.; Jouneau, L.; Bonnet, A.; Le Danvic, C.; Guyonnet, B.; Kiefer, H.; Jammes, H.; Schibler, L. Dynamics of cattle sperm sncRNAs during maturation, from testis to ejaculated sperm. Epigenetics Chromatin 2021, 14, 24. [CrossRef]

- Shome, S.; Jernigan, R.L.; Beitz, D.C.; Clark, S.; Testroet, E.D. Non-coding RNA in raw and commercially processed milk and putative targets related to growth and immune-response. BMC Genomics 2021, 22, 749. [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, P.; Goel, B.M.; Arora, R. Analysis of differentially expressed diverse non-coding rnas in different stages of lactation of murrah buffalo. BIOINFOLET-A Quarterly Journal of Life Sciences 2023, 20, 524-530.

- Li, B.; He, X.; Zhao, Y.; Bai, D.; Bou, G.; Zhang, X.; Su, S.; Dao, L.; Liu, R.; Wang, Y.; et al. Identification of piRNAs and piRNA clusters in the testes of the Mongolian horse. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 5022. [CrossRef]

- Di, R.; Zhang, R.; Mwacharo, J.M.; Wang, X.; He, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Gong, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chu, M. Characteristics of piRNAs and their comparative profiling in testes of sheep with different fertility. Front Genet 2022, 13, 1078049. [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Li, B.; Fu, S.; Wang, B.; Qi, Y.; Da, L.; Te, R.; Sun, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, W. Identification of piRNAs in the testes of Sunite and Small-tailed Han sheep. Anim Biotechnol 2021, 32, 13-20. [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Wang, H.; Ma, K.; Wu, Y.; Qi, X.; Liu, Z.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, Y. Identification and functional characterization of developmental-stage-dependent piRNAs in Tibetan sheep testes. J Anim Sci 2023, 101. [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Hu, H.; Xue, X.; Shen, S.; Gao, E.; Guo, G.; Shen, X.; Zhang, X. Altered expression of piRNAs and their relation with clinicopathologic features of breast cancer. Clin Transl Oncol 2013, 15, 563-568. [CrossRef]

- Hashim, A.; Rizzo, F.; Marchese, G.; Ravo, M.; Tarallo, R.; Nassa, G.; Giurato, G.; Santamaria, G.; Cordella, A.; Cantarella, C.; et al. RNA sequencing identifies specific PIWI-interacting small non-coding RNA expression patterns in breast cancer. Oncotarget 2014, 5, 9901-9910. [CrossRef]

- Koduru, S.V.; Tiwari, A.K.; Leberfinger, A.; Hazard, S.W.; Kawasawa, Y.I.; Mahajan, M.; Ravnic, D.J. A Comprehensive NGS Data Analysis of Differentially Regulated miRNAs, piRNAs, lncRNAs and sn/snoRNAs in Triple Negative Breast Cancer. J Cancer 2017, 8, 578-596. [CrossRef]

- Kärkkäinen, E.; Heikkinen, S.; Tengström, M.; Kosma, V.M.; Mannermaa, A.; Hartikainen, J.M. The debatable presence of PIWI-interacting RNAs in invasive breast cancer. Cancer Med 2021, 10, 3593-3603. [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Wang, J.; Sun, L.; Li, M.; He, X.; Jiang, J.; Zhou, Q. Piwi-interacting RNA-651 promotes cell proliferation and migration and inhibits apoptosis in breast cancer by facilitating DNMT1-mediated PTEN promoter methylation. Cell Cycle 2021, 20, 1603-1616. [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Li, Y.; Lü, J.; Zhao, Q.; Guo, Y.; Lu, Z.; Ma, W.; Liu, P.; Pestell, R.G.; Liang, C.; et al. piRNA-823 Is Involved in Cancer Stem Cell Regulation Through Altering DNA Methylation in Association With Luminal Breast Cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9, 641052. [CrossRef]

- Oner, C.; Colak, E. PIWI interacting RNA-823: epigenetic regulator of the triple negative breast cancer cells proliferation. Eurasian J Med Oncol 2022, 10.

- Zhao, Q.; Qian, L.; Guo, Y.; Lü, J.; Li, D.; Xie, H.; Wang, Q.; Ma, W.; Liu, P.; Liu, Y.; et al. IL11 signaling mediates piR-2158 suppression of cell stemness and angiogenesis in breast cancer. Theranostics 2023, 13, 2337-2349. [CrossRef]

- Ou, B.; Liu, Y.; Gao, Z.; Xu, J.; Yan, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J. Senescent neutrophils-derived exosomal piRNA-17560 promotes chemoresistance and EMT of breast cancer via FTO-mediated m6A demethylation. Cell Death Dis 2022, 13, 905. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Chen, B.; Qiu, P.; Yan, Z.; Liang, Z.; Luo, K.; Huang, B.; Jiang, H. In vitro study of piwi interaction RNA-31106 promoting breast carcinogenesis by regulating METTL3-mediated m6A RNA methylation. Transl Cancer Res 2023, 12, 1588-1601. [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Liu, J.; Ning, Y.; Yin, M.; Xu, M.; Liu, Z.; Liu, K. The piR-31115-PIWIL4 complex promotes the migration of the triple-negative breast cancer cell lineMDA-MB-231 by suppressing HSP90AA1 degradation. Gene 2025, 942, 149255. [CrossRef]

- Alexandrova, E.; Lamberti, J.; Saggese, P.; Pecoraro, G.; Memoli, D.; Cappa, V.M.; Ravo, M.; Iorio, R.; Tarallo, R.; Rizzo, F.; et al. Small Non-Coding RNA Profiling Identifies miR-181a-5p as a Mediator of Estrogen Receptor Beta-Induced Inhibition of Cholesterol Biosynthesis in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cells 2020, 9. [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Mai, D.; Zhang, B.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, J.; Bai, R.; Ye, Y.; Li, M.; Pan, L.; Su, J.; et al. PIWI-interacting RNA-36712 restrains breast cancer progression and chemoresistance by interaction with SEPW1 pseudogene SEPW1P RNA. Mol Cancer 2019, 18, 9. [CrossRef]

- Lü, J.; Zhao, Q.; Ding, X.; Guo, Y.; Li, Y.; Xu, Z.; Li, S.; Wang, Z.; Shen, L.; Chen, H.W.; et al. Cyclin D1 promotes secretion of pro-oncogenic immuno-miRNAs and piRNAs. Clin Sci (Lond) 2020, 134, 791-805. [CrossRef]

- Fu, A.; Jacobs, D.I.; Hoffman, A.E.; Zheng, T.; Zhu, Y. PIWI-interacting RNA 021285 is involved in breast tumorigenesis possibly by remodeling the cancer epigenome. Carcinogenesis 2015, 36, 1094-1102. [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Chen, X.; Zhang, X.; Duan, X.; Pan, T.; Hu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhong, F.; Liu, J.; Zhang, H.; et al. An Lnc RNA (GAS5)/SnoRNA-derived piRNA induces activation of TRAIL gene by site-specifically recruiting MLL/COMPASS-like complexes. Nucleic Acids Res 2015, 43, 3712-3725. [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Tan, X.; Wang, Z.; Shen, L.; Long, C.; Wei, G.; He, D. Novel piRNA MW557525 regulates the growth of Piwil2-iCSCs and maintains their stem cell pluripotency. Mol Biol Rep 2022, 49, 6957-6969. [CrossRef]

- Balaratnam, S.; West, N.; Basu, S. A piRNA utilizes HILI and HIWI2 mediated pathway to down-regulate ferritin heavy chain 1 mRNA in human somatic cells. Nucleic Acids Res 2018, 46, 10635-10648. [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Huang, S.; Tian, W.; Liu, P.; Xie, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Li, X.; Tang, Y.; Zheng, S.; Sun, Y.; et al. PIWI-interacting RNA-YBX1 inhibits proliferation and metastasis by the MAPK signaling pathway via YBX1 in triple-negative breast cancer. Cell Death Discov 2024, 10, 7. [CrossRef]

- Visvader, J.E. Keeping abreast of the mammary epithelial hierarchy and breast tumorigenesis. Genes Dev 2009, 23, 2563-2577. [CrossRef]

- Visvader, J.E.; Clevers, H. Tissue-specific designs of stem cell hierarchies. Nat Cell Biol 2016, 18, 349-355. [CrossRef]

- Shackleton, M. Normal stem cells and cancer stem cells: similar and different. Semin Cancer Biol 2010, 20, 85-92. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.C.; Verheyen, E.M.; Zeng, Y.A. Mammary Development and Breast Cancer: A Wnt Perspective. Cancers (Basel) 2016, 8. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Wei, W.; Yu, L.; Ye, Z.; Huang, F.; Zhang, L.; Hu, S.; Cai, C. Mammary Development and Breast Cancer: a Notch Perspective. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia 2021, 26, 309-320. [CrossRef]

- Visbal, A.P.; Lewis, M.T. Hedgehog signaling in the normal and neoplastic mammary gland. Curr Drug Targets 2010, 11, 1103-1111. [CrossRef]

- Borish, L.C.; Steinke, J.W. 2. Cytokines and chemokines. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2003, 111, S460-475. [CrossRef]

- Saha, B.; Chakravarty, S.; Ray, S.; Saha, H.; Das, K.; Ghosh, I.; Mallick, B.; Biswas, N.K.; Goswami, S. Correlating tissue and plasma-specific piRNA changes to predict their possible role in pancreatic malignancy and chronic inflammation. Biomed Rep 2024, 21, 186. [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Hu, L.; Shi, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yu, G.; Zhou, Y.; An, Q.; Zhu, W. Changes in the Small RNA Expression in Endothelial Cells in Response to Inflammatory Stimulation. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2021, 2021, 8845520. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, N.; Nong, X.; Diao, J.; Yang, G. piRNA-6426 increases DNMT3B-mediated SOAT1 methylation and improves heart failure. Aging (Albany NY) 2022, 14, 2678-2694. [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Yang, L.; Cheng, X.; Huang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Wen, D.; Song, Z.; Li, Y.; Wen, S.; Li, Y.; et al. pir-hsa-216911 inhibit pyroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma by suppressing TLR4 initiated GSDMD activation. Cell Death Discov 2025, 11, 11. [CrossRef]

- Jiao, A.; Liu, H.; Wang, H.; Yu, J.; Gong, L.; Zhang, H.; Fu, L. piR112710 attenuates diabetic cardiomyopathy through inhibiting Txnip/NLRP3-mediated pyroptosis in db/db mice. Cell Signal 2024, 122, 111333. [CrossRef]

- Radmehr, E.; Yazdanpanah, N.; Rezaei, N. Non-coding RNAs affecting NLRP3 inflammasome pathway in diabetic cardiomyopathy: a comprehensive review of potential therapeutic options. J Transl Med 2025, 23, 249. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Yu, F.; Wang, C.; Peng, J.; Wang, C.; Chen, X. PiRNA hsa_piR_019949 promotes chondrocyte anabolic metabolism by inhibiting the expression of lncRNA NEAT1. J Orthop Surg Res 2024, 19, 31. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jiao, X.; Wang, T.; Yue, X.; Wang, Y.; Cai, B.; Wang, C.; Lu, S. piRNA mmu_piR_037459 suppression alleviated the degeneration of chondrocyte and cartilage. Int Immunopharmacol 2024, 128, 111473. [CrossRef]

- Ren, R.; Tan, H.; Huang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yang, B. Differential expression and correlation of immunoregulation related piRNA in rheumatoid arthritis. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1175924. [CrossRef]

- Samir, M.; Vidal, R.O.; Abdallah, F.; Capece, V.; Seehusen, F.; Geffers, R.; Hussein, A.; Ali, A.A.H.; Bonn, S.; Pessler, F. Organ-specific small non-coding RNA responses in domestic (Sudani) ducks experimentally infected with highly pathogenic avian influenza virus (H5N1). RNA Biol 2020, 17, 112-124. [CrossRef]

- Nathan, C. Nonresolving inflammation redux. Immunity 2022, 55, 592-605. [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, M.; Guo, S.; Guo, Y.F.; Zahoor, A.; Shaukat, A.; Chen, Y.; Umar, T.; Deng, P.G.; Guo, M. Upregulated-gene expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6) via TLRs following NF-κB and MAPKs in bovine mastitis. Acta Trop 2020, 207, 105458. [CrossRef]

- Tak, P.P.; Firestein, G.S. NF-kappaB: a key role in inflammatory diseases. J Clin Invest 2001, 107, 7-11. [CrossRef]

- Kyriakis, J.M.; Avruch, J. Mammalian mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathways activated by stress and inflammation. Physiol Rev 2001, 81, 807-869. [CrossRef]

- Haneklaus, M.; O'Neill, L.A. NLRP3 at the interface of metabolism and inflammation. Immunol Rev 2015, 265, 53-62. [CrossRef]

| Species | 5'-terminal Enzyme | 3'-terminal Enzyme | Key PIWI protein | Reference |

| Nematodes | Uncertainty | Uncertainty | Plasticity-related gene 1 (PRG-1)、plasticity-related gene 2 (PRG-2) | [22] |

| Zebrafish | Phospholipase D family member 6 (PLD6) | Uncertainty | ZIWI、ZILI | [23,24] |

| Drosophila | Zuc | Trimmer |

PIWI、Argonaute 3 (Ago3)、Aubergin(Aub) |

[25,26] |

| Mice | PLD6 | Poly(A)-specific ribonuclease-like domain containing 1 (PNLDC1) | MIWI、MIWI2、MILI | [27,28,29] |

| Particular year | miRNA | Research target | Outcomes | References | |

| Mammary gland development | |||||

| 2007 | let-7 | Comma-Dβ | Inhibited self-renewal capacity of progenitor cells and promoted differentiation. | [82] | |

| 2014 | miR-21 | HC11、mice | Regulated mammary gland development and lactation. | [83] | |

| 2012 | miR-30b | Mice | Inhibited normal mammary gland development and lipid droplet accumulation. | [84] | |

| 2020 | miR-31 | HC11、mice | Promoted mammary stem cells (MaSCS) self-renewal, alveogenesis, and lipid droplet accumulation. | [85] | |

| 2020 | miR-34a | Comma-Dβ、SUM159pt、mice | Inhibited MaSCs self-renewal, terminal end bud (TEB) development. | [86] | |

| 2009 | miR-101a | HC11、mice | Inhibited HC11 proliferation and β-casein expression, affected mammary gland development and degeneration. | [87] | |

| 2010 | miR-132、miR-212 | Mice | Promoted ducts growth and modulated epithelial-stromal interactions. | [88] | |

| 2015 | miR-137 | MDA-MB-231、293T、mice | Promoted thickening of the mammary substrate. | [89] | |

| 2006 | miR-138 | Mouse mammary epithelial cells、mice | Regulated mammary epithelial cell proliferation and mammary gland development, promoted β-casein expression. | [90] | |

| 2017 | miR-139 | BMEC、Holstein cows | Inhibited β-casein synthesis and BMEC proliferation. | [91] | |

| 2022 | miR-142-5p、miR-148C、miR-152、miR-218、 | Goats | Regulated mammary gland regenerative degeneration. | [92] | |

| 2014 | miR-193b | MEC、mice | Inhibited mammary stem/progenitor cell activity and alveolar differentiation. | [93] | |

| 2009 | miR-200c | 293T、Tera-2 、mice | Inhibited mammary ducts formation. | [94] | |

| 2018 | miR-205 | MEC、mice | Impacted mammary regenerative capacity and mammary homeostasis. | [95] | |

| 2019 | miR-489 | Mouse mammary epithelial cells、mice | Inhibited ducts growth and TEB formation. | [96] | |

| Milk component synthesis | |||||

| 2018 | miR-15b | MCF-10A、mice、goats | Inhibited lipid synthesis and metabolism. | [97] | |

| 2017 | miR-17-5p miR-148a |

GMEC、goats | Promoted triacylglycerol (TAG) synthesis and milk fat droplet accumulation. | [98] | |

| 2015 | miR-24 | GMEC、goats | Increased unsaturated fatty acid concentrations, TAG levels and milk fat droplet accumulation. | [99] | |

| 2018 | miR-25 | GMEC、goats | Inhibited TAG synthesis and lipid droplet accumulation. | [100] | |

| 2013 | miR-27a | GMEC、goats | Inhibited TAG synthesis and reduced the ratio of unsaturated/saturated fatty acids. | [101] | |

| 2015 | miR-29s | DCMEC、293T、Chinese Holstein cows | Inhibited triglyceride, protein and lactose secretion. | [102] | |

| 2013 | miR-103 | GMEC、goats | Promoted lipid droplet accumulation and TAG accumulation. | [103] | |

| 2011/2017 | miR-126-3p | MCF-10A、mice | Inhibited β-casein secretion and lipid synthesis. | [104,105] | |

| 2019 | miR-142-3p | MMGEC、mice | Inhibited secretion of β-casein and TAG. | [106] | |

| 2017 | miR-145 | GMEC、goats | Promoted lipid droplet enlargement and TAG accumulation, increased the relative content of unsaturated fatty acids. | [107] | |

| 2016 | miR-150-5p | Mice | Inhibited of the de novo synthesis of lipids and fatty acids. | [108] | |

| 2016 | miR-181b | GMEC、goats | Increased TAG levels and cream droplet accumulation. | [109] | |

| 2020 | miR-204 | HC11、mice | Promoted β-casein and milk fat synthesis. | [110] | |

| 2019 | miR-206 | HC11、mice | Promoted lipid accumulation. | [111] | |

| 2018 | miR-221 | MEC、MCF-10A、mice | Promoted lipid synthesis. | [112] | |

| 2015 | miR-486 | BMEC、Holstein cows | Promoted beta-casein, lactose and lipid secretion. | [113] | |

| Particular year | Detection Methods | Species | Outcomes | References |

| 2021 | Small RNA-seq | Porcine | Characterization of the composition of piRNAs in spermatozoa suggests that piRNAs may be potential negative regulatory markers of sperm quality. | [126] |

| 2012 | Small RNA-seq、qRT-PCR | Porcine | It was demonstrated that piRNAs were predominantly enriched in the mature gonads and were expressed more in the testis than in the ovary. | [127] |

| 2023 | Small RNA-seq | Porcine | Expression of piRNAs is regulated by Senecavirus A (SVA) and promotes apoptosis. | [128] |

| 2015 | Small RNA-seq | Porcine | Characterization of the composition of piRNAs in testis suggests that mammalian piRNAs exist in the ping-pong cycle and have a role in the post-transcriptional regulation of protein-coding genes. | [121] |

| 2022 | Small RNA-seq | Xiang pigs | Identification of the composition of piRNAs in testicular tissues at different stages demonstrates that piRNAs regulate spermatogenesis. | [120] |

| 2017 | Small RNA-seq 、qRT-PCR | Porcine | Characterization of the expression profiles of testicular piRNAs at different stages of sexual maturation demonstrated that piRNAs regulate testicular development and spermatogenesis. spermatogenesis. | [129] |

| 2012 | Small RNA-seq、qRT-PCR | Porcine | Evidence for a potential role of piRNAs in female germ cell development. | [130] |

| 2020 | Small RNA-seq 、qRT-PCR | Porcine | Characterization of the expression profile of sperm plasma extracellular vesicles (SP-EV) piRNAs suggests that piRNAs play a role in the physiological function of spermatozoa. | [131] |

| 2017 | Small RNA-seq、qRT-PCR | Bovids | The piRNAs in the testis were identified as longer than the piIRNAs in oocytes and embryos. | [132] |

| 2020 | Small RNA-seq | Yattle、cattle、yaks、 | Promoter hypermethylation of PIWI/piRNA pathway genes leading to gene silencing and reduction of testis-thick piRNAs is a driver of bovine HMS. | [122] |

| 2015 | Small RNA-seq | Calves | Expression of piRNAs in bovine blood and plasma was revealed, suggesting that they may originate from tissues other than blood cells and thus enter the circulation. | [133] |

| 2018 | Small RNA-seq | Cattle、yaks、dzo | Comparison of the expression characteristics of three ruminant piRNAs provides theoretical references for exploring their regulatory mechanisms in spermatogenesis and dzo reproductive therapy. | [134] |

| 2020 | Small RNA-seq、qRT-PCR | Bulls | Expression of piRNAs in spermatozoa was detected, suggesting that they may play a role in embryonic development and may serve as biomarkers of semen fertility. | [135] |

| 2017 | Small RNA-seq | Bulls | Characterization of the composition of piRNAs in frozen spermatozoa suggests a role in sperm development and fertility. | [123] |

| 2015 | Small RNA-seq | Bovine | Detection of the composition of mature testicular and ovarian piRNAs revealed that ovarian piRNAs were very similar to spermatogenesis thick-walled stage piRNAs. | [136] |

| 2018 | Small RNA-seq | Bovids | Detection of milk exosomal piRNAs expression suggests that they may be related to immune and developmental functions. | [125] |

| 2021 | Small RNA-seq | Cattle | The presence of piRNAs in ejaculated sperm was confirmed, suggesting that they may regulate sperm maturation, fertilization process, and embryonic genome activation. | [137] |

| 2021 | Small RNA-seq | Bovids | Expression of piRNAs was detected separately in both milks, suggesting a possible regulatory role in calf immunity and development. | [138] |

| 2023 | Small RNA-seq | Murrah buffalo | Characterization of the composition of piRNAs at different stages of lactation implies that piRNAs can serve as potential targets for the regulation of lactation. | [139] |

| 2019 | Small RNA-seq | Mongolian horse | Characterization of piRNAs composition in sexually mature and immature testes suggests that piRNAs may regulate testicular development and spermatogenesis. | [140] |

| 2022 | Small RNA-seq | Sheep | Expression profiles of piRNAs in LP and FP ovaries were characterized to facilitate understanding of the role of piRNAs in the estrous cycle. | [124] |

| 2022 | Small RNA-seq | Sheep | Characterization of the composition of testicular piRNAs demonstrates that piRNAs may mediate blood-testis barrier stability and spermatogonial stem cell differentiation. | [141] |

| 2021 | Small RNA-seq | Sunite (SN)、Small-tailed Han (STH) | Identification of differential expression of testicular piRNAs in different breeds suggests that piRNAs may be associated with male fecundity. | [142] |

| 2023 | Small RNA-seq、qRT-PCR | Tibetan sheep | Characterization of piRNAs expression profiles in different stages of testis suggests that piRNAs regulate male fertility and spermatogenesis. | [143] |

| Particular year | piRNA | Expression | Research target | Finding | References |

| 2021 | piR-651 | Upregulation | MDA-MB-231、MCF-7、AU565、HCC38 | Bound to PIWIL2, promoted cell proliferation and migration through DNMT1-mediated methylation of the PTEN promoter. | [148] |

| 2021 | piR-823 | Upregulation | MCF-7、T-47D、nude mice | Increased the expression of DNMT1, DNMT3A, and DNMT3B genes to promote DNA methylation of APC genes to activate the Wnt signaling pathway. | [149] |

| 2022 | piR-823 | Upregulation | MDA-MB-231 | Inhibited piR-823 expression inhibited cell proliferation, PI3K/Akt /mTOR gene expression, and increased gene and protein expression of ERα. | [150] |

| 2013 | piR-932 | Upregulation | Cancer stem cells、SCID mice | Bound to PIWIL2, promoted methylation of promoter CpG islands to repress Latexin expression. | [9] |

| 2023 | piR-2158 | Downregulation | ALDH+ breast cancer stem cells、MDA-MB-231、4T1、HUVEC、293T、nude mice、BALB/c mice | Competed with FOSL1 to inhibit IL-11 expression and secretion, inactivated JAK/STAT signaling and thereby inhibiting breast cancer. | [151] |

| 2022 | piR-17560 | Upregulation | MDA-MB-231、MCF-7 | Targeted FTO-mediated m6A demethylation enhances ZEB1 expression, thereby promoting chemotherapy resistance and EMT. | [152] |

| 2013 | piR-4987 piR-20365、piR-20485、piR-20582 |

Upregulation | breast tissue samples | Influenced cancer development and lymph node metastasis. | [144] |

| 2017 | piR-1282、piR-21131、piR-23672、piR-26526、piR-26527、piR-26528、piR-30293、piR-32745 | Upregulation | breast tissue samples | Can be used as a biomarker for breast cancer and provided a therapeutic target. | [146] |

| piR-23662 | Downregulation | ||||

| 2014 | piR-31106 | Upregulation | MCF-7、SKBR3 、ZR-75.1、MCF10A | Responded to cell growth, cell cycle progression, and hormonal signaling. | [145] |

| 2021 | piR-31106、piR-34998、piR-40067 | Upregulation | breast tissue samples | Can be used as a prognostic and therapeutic marker for breast cancer | [147] |

| 2023 | piR-31106 | Upregulation | MDA-MB-231、MCF-7 | Promoted cell proliferation and migration as well as oncogene expression and METTL3-mediated m6A methylation. | [153] |

| 2025 | piR-31115 | Upregulation | MDA-MB-231、MCF-7、SK-BR-3、MCF-10A | Bound to PIWIL4 and inhibits the degradation of HSP90AA1 protein, thereby promoting cell migration. | [154] |

| 2020 | piR-31143 | Upregulation | HCC1806、MDA-MB-468、Hs 578T | Can modulation of TNBC behavior through ERβ. | [155] |

| 2014 | piR-34377、piR-35407、piR-36743 | Upregulation | MCF-7、SKBR3 、ZR-75.1、MCF10A | Responded to cell growth, cell cycle progression, and hormonal signals. | [145] |

| piR-36026、piR-36249、piR-36318、piR-36712 | Downregulation | ||||

| 2019 | piR-36712 | Downregulation | MCF-7、ZR75-1、293T、BALB/c nude mice | Knockdown of piR-36712 inhibits p53 activity through SEPW1, upregulates Slug/p21 and decreases E-calmodulin levels, ultimately inhibiting cell proliferation, migration and invasion. | [156] |

| 2020 | piR-016658 | Upregulation | MCF-7、SUM-159、Hs-578t、MDA-MB-231、MDA-MB-453、T-47D、BT474、SKBR3 | Regulated by cell Cyclin D1, affects stem cell function. | [157] |

| piR-016975 | Downregulation | ||||

| 2015 | piR-021285 | Upregulation | MCF-7、MDA-MB-231 | Increases the methylation level of ARHGAP11A gene, which promotes cell invasion and inhibits cell apoptosis | [158] |

| 2015 | piR-sno75 | Upregulation | MCF-7、HEK293T、NOD/SCID mice | Binding to WDR5 recruits the MLL3/UTX complex to the TRAIL promoter region thereby inducing H3K4 methylation and H3K27 demethylation. | [159] |

| 2022 | piR-MW557525 | Upregulation | FBs、Piwil2-iCSCs | Promotes the proliferation, migration and invasion of Piwil2-iCSCs, promotes the expression of CD24, CD133, KLF4 and SOX2, and inhibits apoptosis. | [160] |

| 2018 | piR-FTH1 | Downregulation | MDA-MB-231、MCF-7、HEK293、A549、A2008、PC3、RF3、Hela | Binds to HILI/HIWI2 and down-regulates FTH1, increasing sensitivity to chemotherapy. | [161] |

| 2024 | piR-YBX1 | Downregulation | MDA-MB-231、BT 549、BALB/c nude mice | Inhibition of YBX1 expression leads to inhibition of MEK and ERK1/2 MAPK signaling pathways ultimately inhibiting cell proliferation and migration. | [162] |

| Particular year | piRNA | Expression | Research target | Finding | References |

| 2024 | hsa-piR-3411、hsa-piR-24541、hsa-piR-27080、hsa-piR-28104、hsa-piR-32157 and 10 others | Upregulation | Human peripheral venous blood | Identification of piRNAs in the plasma of CP patients demonstrated that piRNAs are associated with inflammation. | [170] |

| hsa-piR-32835、hsa-piR-32836、hsa-piR-32986、hsa-piR-33168 | Downregulation | ||||

| 2022 | piRNA-6426 | Downregulation | Rat cardiomyocytes、rats | Inhibits secretion of inflammatory factors IL-1β and TNF-α, cardiomyocyte apoptosis, oxidative stress, and improves the inflammatory microenvironment in heart failure. | [172] |

| 2023 | piR-has-27620、piR-has-27124 | Upregulation | Blood samples | Identification of peripheral leukocyte piRNAs expression and their enrichment in Rap1, PI3K-Akt, and MAPK pathways as RA biomarkers. | [178] |

| 2021 | rno-piR-017330 | Upregulation | Endothelial cells、 rats | Identification of piRNAs expression in endothelial cells under inflammatory conditions suggests that piRNAs may regulate inflammatory processes. | [171] |

| 2024 | hsa_piR_019949 | Downregulation | C28/I2、SW1353 | Inhibition of NEAT1 and NLRP3 expression regulates the NOD-like receptor signaling pathway and modulates OA progression. | [176] |

| 2024 | mmu_piR_037459 | Upregulation | Mice cardiomyocytes、mice | Inhibition of collagenase II expression, promotion of chondrocyte apoptosis and inhibition of proliferation, inhibition of USP7 expression, and regulation of OA progression. | [177] |

| 2024 | piR-112710 | Downregulation | Mice cardiomyocytes、mice |

Inhibits the Txnip/NLRP3 signaling pathway, reduces the levels of IL-18, IL-1β, and NLRP3, inhibits cardiomyocyte injury, and regulates inflammation progression. | [174] |

| 2025 | pir-has-216911 | Upregulation | HL7702、Huh7、 HepG2、Hep3B、nude mice | Inhibition of the TLR4/NFκB/NLRP3 inflammatory signaling pathway suppressed the inflammatory response. | [173] |

| 2020 | piRNAs | Differential expression | Sudani duck | The composition of piRNAs in brain and lung was characterized, suggesting that they may be associated with lung inflammation. | [179] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).