1. Introduction

The construction of a fence in the sea made of bamboo sticks along Tangerang, Banten, Indonesia’s coastal areas, has been controversial and broadly discussed in most Indonesian media. The fence reached a length of more than 30km and became visible to the local population and by aerial and satellite images. The fence closed off a bay to local fishing traffic and appeared to be an initial delineation of what looked like a reclamation plan. Various stories emerged on who constructed this fence and why. Moreover, who authorized this construction, and why was the local population apparently not involved in the planning and evaluating possible impacts? Was there a plan at all, and had rights and responsibilities already been surrendered or allowed outside standard institutional and legal procedures? Was this a unique case of apparent informal or extra-legal demarcation of sea territory, or was this a signal that a broader process is taking place whereby individuals, private and/or public organizations can claim and demarcate sea and land rights themselves rather than rely on officially approved procedures and participatory, inclusive processes? If so, are alternative institutional processes emerging alongside the formal ones, or in the lack of effective formal ones?

This article starts by selecting two theoretical modelling perspectives on integration: a territoriality and space perspective on the one hand and an institutional perspective on the formal legal procedures of how Indonesian laws regulate the steps to create structures and buildings for land and sea. Both perspectives serve as a basis to compare the emerging practices of the specific case of the sea fences in Tangerang (with the information available through recent and accessible documentation) to analyse : (1) which controversies and contradictions between formal procedures and informal practices related to land and sea rights exist (2) which values and perceptions of the involved stakeholders play a role in these controversies and contradictions (3) which kind of boundary work or boundary objects could resolve these controversies and contradictions.

2. Theoretical Embedding

The theoretical embedding starts by viewing land and sea from the perspective of territoriality and space. From this conceptualisation, one can describe how Indonesia has regulated their territory and space of both land and sea.

2.1. Territoriality and Space

Territory refers to the authority and responsibility of a certain space within boundaries. Territoriality refers to the process of establishing ownership and control over a space, whether it is a physical location or a broader neighborhood [

1]. A key factor is the debate about the legitimacy of control over space. The debate around its legitimacy is the question of the extent to which the physical environment interacts with social factors to shape an individual’s behavior. Or, in other words, once any actor claims a space, when or how will that claim become legitimate, legal or illegal, and which authority has the mandate and the adequate enforcement power to rule over this space, even if this means involuntary eviction?

The conventional manner of gaining and documenting legitimate claims or formal rights is either by adjudicating and delineating these rights, followed by cadastral mapping and registration and/or recording process in a formally recognized legal database. Common is also to use Land Administration Domain Models (LADM) in which the actors, space, rights, restrictions and responsibilities are described and formally connected. Similar models exist for sea or marine rights [

2].

There are, however, several situations when the conventional approaches are challenged. In coastal areas affected by tidal floods, formally registered land may become permanent or semi-permanent sea space. In these cases, the land right still exists, at least for some time, until there is a formal declaration that space has become sea instead of land [

3]. This declaration automatically changes the spatial authority, as different ministries or agencies are mandated to allocate rights, restrictions, and licenses over sea or coastal areas instead of land areas.

Another situation concerns reclamation. This changes the control over space in the other direction, from the sea or water bodies to land agencies and municipalities. The newly reclaimed land typically becomes subject to the same landownership laws as existing land, meaning it can be owned, sold, or used under local regulations. The reclaimed land can be subject to zoning laws and development regulations, like other land areas. Land reclamation reduces the sea area, and the former seabed becomes land, impacting the extent of the territorial sea and other maritime zones. Land reclamation can have implications under international law, particularly concerning the delimitation of maritime boundaries and the rights of coastal states. Reclamation projects are often subject to environmental regulations and assessments to minimize their impact on the marine environment.

A third situation which confuses who has control over space concerns the construction of houses on or on top of the water. [

4] describe how the Bajau tribe in Indonesia construct their houses and entire community areas on top of water or sea areas. From a land registration point of view, the ownership or land rights of the community members are difficult to register, as the properties are not on land and thus cannot be connected to coordinates on land. [

5] argue that their rights can be protected through so-called HGB rights, which in Indonesian land law refers to the right to build and own buildings on land that is not theirs. In the case of the Bajau tribe, these HGB certificates were provided for a maximum period of 30 years, with an extension possibility of 20 years. According to Article 35 of the Indonesian land law, such building rights can even be transferred to any third party, and the right can be upgraded to a Freehold title by applying to upgrade the status of Land Rights under applicable laws and regulations.

A last comment on the lawful or unlawful claiming of land or sea concerns the activity of fencing and fencing off. [

6] describe how large landscapes of grazing land are being fenced off in Kenya to exercise influence and power in a conflict over statutory and pastoralist land tenure. They argue that ‘While fences fill in landscapes, and grazing restrictions are set within (still unfenced) conservancies, the dependency on the commons may sooner or later push these hybrid pastoral practices to a point where their grazing practices are no longer compatible with a fully fenced landscape’. In other words, fencing is a means to control space, yet ultimately leads to a tragedy of the commons or the public benefits.

From these quandaries and contradictions, one can derive the following key adapted principles of territoriality and space with a specific reference to integrating land and sea rights, restrictions and responsibilities:

The current spatial boundaries between land and sea create an institutional vacuum and overlap, contradicting operational procedures and expectations. Therefore, the control over land and sea should be inter-connected and reflect both a spatial and legal continuum. This can be the basis for a single (omnibus) law.

Spatial planning laws and regulations should integrate procedures considering all values and claims from all affected stakeholders on land and sea.

Ownership and use models of spatial entities should be possible for hybrid constructions on land and sea

2.2. Institutional Models of Land and Sea Rights in Indonesia

Land and sea rights are typically managed in two separate institutional systems: spatial planning and land administration (including cadastral surveys and registration of land rights, restrictions and responsibilities) and ocean, marine and fisheries management. On top of that, the coastal local and regional governments manage the coastal spaces. Analysing how such systems operate can rely on various logic and principles, which determine inter-and intra-organisational and institutional relations and interactions. The formal rules prescribe the expected ‘humanly devised constraints in behaviour’, whereas the de facto practices reveal the ‘rules, norms, and social structures created by people that shape and limit individual behaviour within a society’ (using the classical definition of [

7]). Comparing how and why these differ can reveal the causes and effects of controversies and contradictions.

The formal procedures in Indonesia to obtain ownership, use, building rights, licenses, etc., and decide on responsibilities, restrictions, ramifications, sanctions, penalties over non-compliance with land and sea laws, etc., depend on different laws which overlap and interact. These include:

Law No. 5 of 1960 concerning Basic Agrarian Principles (UUPA). This law regulates all land-related rights, restrictions, and responsibilities matters in Indonesia, including land ownership and utilisation. It also provides the basis for all rights related to the Earth, the sea, and space.

Law No. 26 of 2007 on Spatial Planning. This law governs spatial planning across Indonesia, which is crucial for managing land and coastal areas.

Law No. 27 of 2007 (amended by Law No. 1 of 2014) on the Management of Coastal Areas and Small Islands: This legislation explicitly addresses the management of coastal regions and small islands, which is vital for regulating sea rights and the interface between land and sea.

Regulation of the Minister of Agrarian Affairs and Spatial Planning/Head of National Land Agency Number 17/2016 regarding Land Management in Coastal Areas. This regulation provides detailed guidance on land management within coastal areas, including the provision of land rights.

Law No. 32 of 2014 concerning Maritime Affairs. This law is also very important for the regulation of sea rights, including the utilisation and management of marine resources.

Government Regulation Number 18/ 2021 regarding Management Right, Land Right, Apartment Unit, and Land Registration. This regulation provides detailed guidance on the implementation of management rights, land rights and land registration. It outlines the procedures for granting management rights (HPL), cultivation rights (HGU), building rights (HGB), and use right (HP) over land, including reclamation land.

Presidential Regulation Number 122/ 2012 regarding Reclamation in Coastal Areas and Small Islands. This regulation governs the procedures for implementing reclamation, including the division of authority in issuing reclamation permits. Further details on the implementation are regulated under the Regulation of the Ministry of Marine and Fisheries Number 25/ 2019 regarding the Reclamation Permit in Coastal Areas and Small Islands.

Regulation of the Head of the National Land Agency of the Republic of Indonesia Number 2/2013 regarding The Delegation of Authority to Grant Land Rights and Land Registration Activities. This governs the distribution of authority for granting land rights, including SHM and SHGB, to the Land Office (local level), Regional Office (provincial level), and Central Government (national level).

According to Indonesian law, maritime and terrestrial areas are governed under different spatial jurisdictional authorities. Terrestrial areas fall under the authority of the Ministry ATR/BPN, the government body authorised to issue land certificates, including SHM and SHGB. Generally, SHM and SHGB are issued by local Land Offices. However, for SHM with an area exceeding 3000 m

2 (non-agricultural land) or 50,000 m

2 (agricultural land), and SHGB exceeding 3000 m

2 (for individuals) or 20,000 m2 (for legal entities), the authority to grant the rights is vested in the Regional Office or Central Government. Furthermore, the authority over spatial conformity differs between terrestrial and coastal areas. For land in terrestrial areas, spatial conformity refers to the Regional Spatial Plan (RTRW) or the Detailed Plan of Spatial Planning (RDTR) issued by the Local Government, or to the National RTRW if the area is designated as a National Strategic Area (PSN). Meanwhile, for coastal areas, the spatial conformity refers to the Zoning Plan for Coastal Areas and Small Islands (RZWP3K), which falls under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of KKP. The Ministry of Environment and Forestry (KLHK) may also be involved in environmental impact assessment, particularly concerning conservation areas. However, granting SHM and SHGB in coastal areas requires a Location Permit from the Ministry of KKP, ensuring its alignment with the RZWP3K and approval of Marine Spatial Utilisation Suitability (KKPRL). If the land originates from reclamation, it must be accompanied by a Reclamation Permit issued by the Governor or Minister of KKP. We further present a comparison of land certificate issuance (SHM and SHGB) between terrestrial and coastal areas, as shown in

Table 1.

3. Methodology

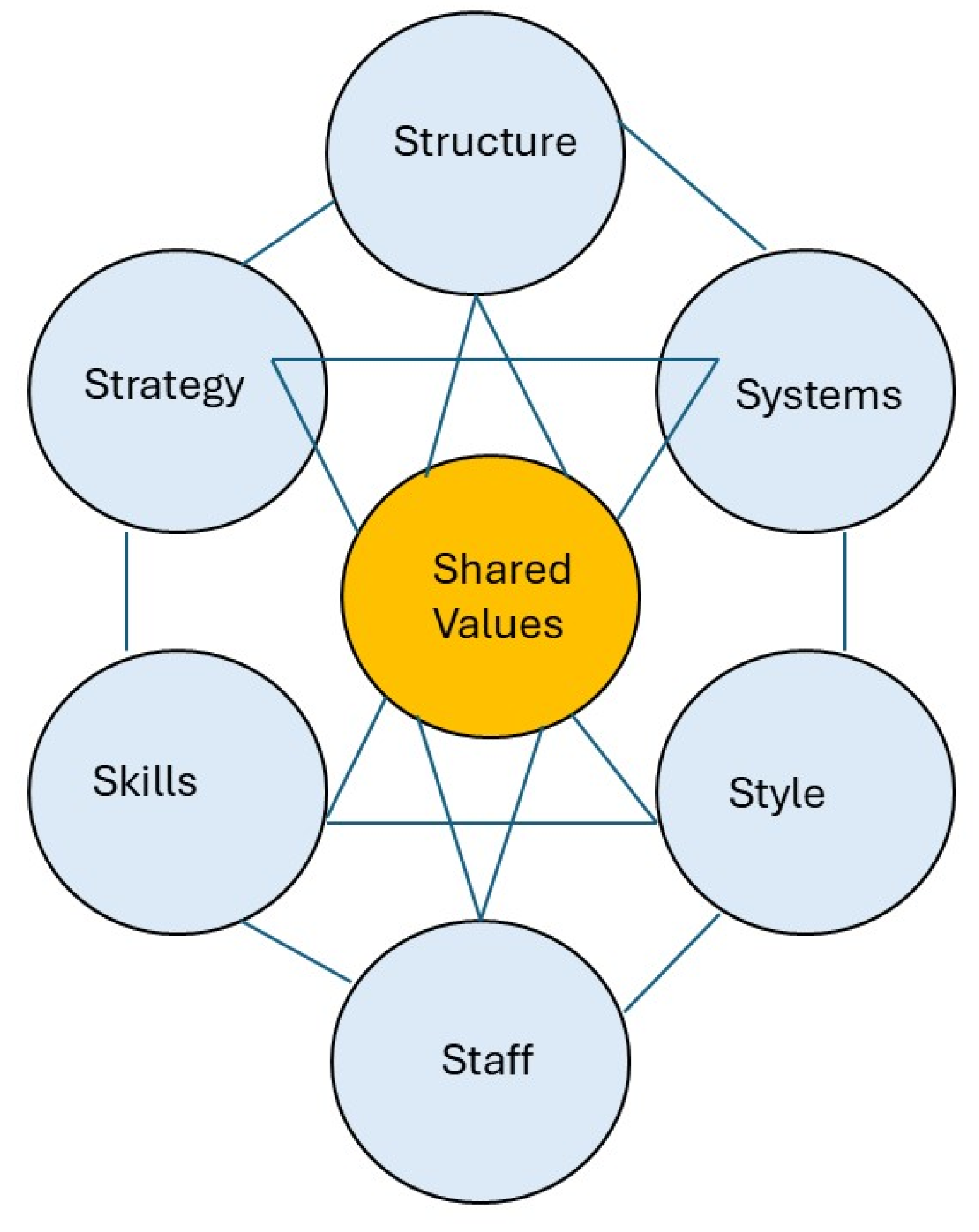

As the documentation on the controversies and contradictions connected to the ‘Pagar Laut’ is relatively limited in scientific literature and publicly accessible government reports, the methodology of data collection relied on a systematic search for grey literature, consisting of reliable and reputable journalistic media, websites, and hard copy publications, as well as on the social media tags #pagarlaut. Once these were collected, an interpretative review took place based on a set of prompts derived from the McKinsey 7S Model [

8,

9,

10]. This model served as an analytical model to evaluate the actual practices of controversies and contradictions arising from the differences between formal procedures and informal practices related to land and sea rights. This model connects the behaviour and perceptions of interrelated stakeholders through the 7s’s, which represent Structure, Strategy, Skill, System, Shared Values, Style, and Staff (presented in

Figure 1). The 7S model posits that organisations, or organisational systems, succeed and perform well when all these factors align and mutually reinforce each other. Analysing where the factors do not align makes it possible to find causes for controversies and contradictions and starting points for improving, regulating, or re-engineering the organisational system.

4. Results

4.1. Study Site

The sea fence spans approximately 30.16 kilometres along the coastal waters of 6 sub-districts and 17 villages within the Tangerang and Serang Regencies. Positioned about 200 – 500 offshore, the barrier extends from Teluknaga to Kronjo. The surrounding are primarily consists of swamps, fishponds and mangrove forests. A visual representation of the sea barrier is provided in

Figure 2, with an example of the existing conditions in Kohod Village, which has been at the center of media coverage and discussion in this paper.

4.2. Sequence of Events

The Indonesian newspaper Kompas reports on 23 January 2025 that since early January 2025, the public has witnessed and has been shocked by the discovery of a mysterious 30.16-kilometre sea fence in the waters of Tangerang Regency, Banten [

11]. The sea fence is reportedly made of bamboo that is stuck into the seabed. The initial issue surrounding the mysterious coastal fence was the illegal and unlawful reclamation of coastal waters, which later expanded to include environmental, socio-economic, and coastal management concerns. The report further states that several authorities have intervened in dealing with the sea fence, from the local government to the central government. Some parties admit to having a role in constructing the sea fence, while others deny it. Also, several officials’ names were dragged into the vortex of the Tangerang Sea fence case.

At roughly the same time, a report of the VOI reports that the Indonesian Ombudsman (ORI) has investigated the case [

12]. The ORI concludes that the 30.16 km long sea fence affected 16 villages in 6 sub-districts, including Kronjo, Kemiri, Mauk, Sukadiri, Pakuhaji, and Teluknaga. This area is included in the general utilization area regulated by Regional Regulation Number 1 of 2023. This area covers critical zones such as fishery capture, fishing ports, tourism, and energy management. These reported facts trigger discussions and critical remarks by experts, practitioners and politicians. Marine expert from Airlangga University, Prof. Mochammad Amin Alamsjah, emphasizes that the fence contradicts Article 33 paragraph 3 of the 1945 Constitution, which states that the state controls the sea and the natural resources within it for the welfare of the people [

13]. The legal argument is that the sea fence violates this law and can potentially damage the marine ecosystem. “This fence can accelerate sedimentation, damage fish habitat, and threaten the life of marine biota such as coral reefs and seagrass beds”. Another impact is that local fishermen have difficulty going to sea because their access is restricted. As a result, they needed to look for new locations that were further away, required more money, and impacted the decline in fish catches. “If this sea fence remains, fishermen will have more difficulties. Productivity decreases, and their economy can be disrupted,” states Prof. Amin.

Despite reaching national notice in early 2025, officials were aware of the sea fence’s existence some months previously. The Banten Provincial Marine and Fisheries Office (DKP) first received a report concerning the structure on August 14, 2024. Five days later, a field inspection revealed that the fence at that time extended approximately 7 kilometres. In early September 2024, DKP Banten, in coordination with the Civil Service Police Unit (Polsus) from the Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries (KKP), conducted further site visits and discussions. Findings revealed that the construction lacked official recommendations or permits from local sub-district or village authorities. Shortly thereafter, the Ministry of KKP sealed off the structure, citing the absence of a Coastal and Small Islands Zoning Utilisation Permit (KKPRL) and its location within designated Capture Fisheries and Energy Management Zones.

Further investigation revealed that several land certificates had been issued in the coastal fence area, comprising 263 plots with Building Use Right (SHGB) status – 258 owned by private entities and 9 by individuals – and 17 plots held by individuals with private right (SHM). In a press conference on 30 January 2025, current Minister of ATR/BPN, Nusron Wahid, stated that nearly all of these certificates were issued through the conversion of traditional land rights (girik) that had been issued in 1982, indicating that no new land rights were granted. Moreover, as the certificates were issued between 2022 and 2023, less than five years since the issue arose, they may be revoked directly without court proceedings due to administrative irregularities [

14]. In February 2025, the Ministry of ATR/BPN revoked 193 certificates deemed illegal due to procedural errors, while 13 remain under review, and 58 certificates were not revoked.

While some parties have claimed that the sea fences were constructed on submerged land to prevent coastal abrasion, Gadjah Mada University (UGM) experts have refuted this assertion. A study conducted by the UGM team, using satellite imagery, indicates that the area has historically been part of the sea. The imagery reveals that since 1976, the shoreline has remained hundreds of meters away from the current location of the sea fences. This pattern persisted through 1982. Although there have been some land certificate claims, the satellite data consistently shows that the area has never constituted dry land. Further analysis using Sentinel-2 satellite data suggests that the sea fence was likely constructed around May 2024 [

15].

There were also significant debates on the fences’ legality and the information’s transparency. There were serious allegations of permits being obtained through questionable means. The issuance of SHGB and SHM titles for the contested area suggests possible legal manipulation and land mafia practice. According to the Agrarian Reform Consortium (KPA), the subdivision of SHGB into smaller plots was mostly intended to allow registration and the local Land Office (district level), bypassing central government oversight. Furthermore, SHGB titles cannot legally be issued over marine areas, as stipulated in Government Regulation No.18/ 2021 in conjunction with Ministerial Regulation Number 18/2021. KPA also noted potential alterations to land and marine spatial planning at the local government level, which may have shifted coastal boundaries, enabling the issuance of location permits (PKKPR) to support SHGB registration [

16]. The progression of the case was further illustrated in the timeline presented in

Figure 3.

Besides the newspaper and grey literature articles, the online discussions with #pagarlaut demonstrated a range of strong opinions. Drawing on the information gathered, the key controversies are related to environmental damage, anticipated impact on local fishermen, issues of legality and transparency and mere conflicting interests of stakeholders. The debates showed the conflicting interests of stakeholders. The controversy highlights the tension between economic development and environmental protection. Critics argue that the ‘Pagar Laut’ projects prioritize the interests of investors over the well-being of local communities and the environment. The environmental damage controversy concerns that the fencing structures could potentially harm the coast. The critique was that the fences disrupt the natural water flow, leading to sedimentation and damage to marine habitats. This disruption also poses a threat to the biodiversity of the area, affecting various marine species . From the perspective of local fishermen, the main problems were that the ‘Pagar Laut’ structures had been accused of obstructing traditional fishing routes and access to fishing grounds. This directly impacts the livelihoods of local fishermen, who rely on these areas for their sustenance. Those fishermen feel they are being kept out of their own “home”. The development of ‘Pagar Laut’ should be carried out with greater transparency and inclusive public engagement, and it is essential that such initiatives consider the interests of multiple stakeholders, including local fishers and coastal communities [

17].

The lack of transparency in the planning and construction fuelled suspicion and distrust among local communities. There were also allegations of corruption. The ‘Pagar Laut’ issue drew attention from high-ranking officials, indicating the seriousness of the situation. There are calls for thorough investigations and legal action against those responsible for illegal activities. Some expressed the feeling that a “mafia” is controlling the progress of these projects, which could have legal and political ramifications.

4.3. The Stakeholders Related to 7Ss in the ‘Pagar Laut’ Case

Table 2 presents the stakeholders - persons or institutions - who are involved in the ‘Pagar Laut’ issue.

4.4. The 7S Values

Analysing the stakeholders of the ‘Pagar Laut’ issue for similarities in behaviour, strategy, skills, systems, values, presentation styles, and staff reveals a complex picture of convergence and divergence. While some actors – such as local communities, civil society organisations, and environmental experts – shared values rooted in ecological sustainability, transparency and social justice, other actors, including certain government bodies and private developers appeared driven by growth-oriented or profit-maximising strategies. Structural and systematic fragmentation among institutions has led to inconsistencies in the application of land and marine spatial regulations, with varying levels of institutional and legal capacity across actors. Although operating within a common bureaucratic structure and legal framework, government bodies differ in their effectiveness and public engagement approaches. They generally require legal expertise and public communication skills. Local communities rely heavily on local knowledge and uphold values related to traditional livelihoods and cultural preservation. Organisations and experts primarily engage in research, advocacy, and legal reform. Developers and private companies, by contrast, emphasise legal compliance, financial planning, and professional stakeholder presentations. These differences are also reflected in strategic and skill-based approaches: developers and officials leverage legal, financial, and economic tools, while civil society actors rely on advocacy, grassroots mobilisations, and traditional practices to assert their rights. Communication styles further illustrate these divides, with formal bureaucratic discourse often clashing with affected communities’ direct, emotive expressions. We summarise the findings of the 7 values of all involved stakeholders in

Table 3.

Furthermore, we also present a colour-coded matrix in

Table 4 to visualise stakeholder alignment or divergence on each of the 7 elements. Red colours represent the highest distance (or lowest likelihood) from reaching a consensus on this issue, orange represents a partial alignment, and green implies the highest probability of reaching a consensus. The assessments in this table are based on how firm and strict or inert each stakeholder is on the specific aspect, and the colour codes are based on interpretations of verbal or documented evidence. Where the colour codes are orange or green, the assumption is that there is some room for changing the fundamental positions on these aspects, whereas a colour code red would imply no space for any change.

5. Discussion

The analysis reveals key contradictions, boundaries, and areas of reaching potential consensus. Firstly, significant contradictions emerged particularly in the domain of shared values. Government bodies and organisations generally prioritise legal frameworks, regulatory compliance, public accountability and public interests. In contrast, developers prioritise profit and efficiency, and local communities emphasise cultural preservation, environmental sustainability and traditional livelihoods. These differing values result in significant rigid and fixed positions and hence conflicts in relation to the sea fence issue.

Secondly, clear cultural and organisational boundaries exist between stakeholders, especially in structure, style and strategy. Government institutions and developers operate in a nodal cooperation culture through a formal, hierarchical system with structured communication and strategic planning. In contrast, communities often function through informal networks, relying on direct action, pragmatic and ad hoc cooperative structures and emotive appeals. This divergence in operational systems and communicative approaches reinforces divisions and can hinder mutual understanding and boundary work. The informal nature of community organisation can also limit their ability to develop and implement structured strategies, especially when engaging with institutional stakeholders. Without formal frameworks, the community may struggle to maintain consistency, coordinate efforts, or gain legitimacy in policy discussions, further widening the gap between them and more institutionalised actors.

Thirdly, communication styles vary significantly among stakeholders, from formal government statements to emotional community protests. The rigidity of structures and systems in which the actors operate and interact influences the shared values in the operationalisation of strategies. Discretionary spaces of decision makers and strategists expand and open the possibilities for opportunistic behaviour and corruption. If the desired results cannot be achieved via formal processes, actors start to reach their goals via informality and possibly illegality. Additionally, multiple narratives start to emerge with processes of re-framing, blaming and shaming. Such novel strategies may conceal the strategic informality and illegality. A panel discussion aired on YouTube revolved around the contrasting perspectives of the police and prosecutors, with the police focusing on document forgery and the prosecutors leaning towards corruption. The panel highlighted the importance of collaboration between the police and the prosecutor’s office, potentially with KPK assistance, to resolve the case effectively and transparently. The panel expressed public concern over the release of the suspect due to the expiration of the detention period, emphasising the need for justice and accountability. They stress that focusing on corruption charges could reveal a broader network of involved parties beyond the initial four suspects. Ultimately, they urge the police to align with the prosecutor’s direction by investigating forgery and corruption to ensure a thorough and credible legal process.

Finally, while

Table 4 highlights the differences between the 7S and difficulties in reaching consensus,

Table 4 is also helpful in assessing the potential for so-called boundary objects or boundary work to start or create a dialogue to resolve the differences. [

11,

12,

13]. This could, for example, start by identifying staff from different stakeholders with a similar educational or geographical background. This background may epistemically and/or emotionally connect staff members of various stakeholders and thus create a fundamental willingness to move forward and adapt their positions in the debate. It may also be a start for further information exchange and transparency in what is expected and what is being achieved and debunk some of the narratives emerging in regular and social media. Another anchor to foster boundary work is to start the exchange of formal academic/scientific knowledge and information, visible and manifested in longitudinal geospatial information (for example, with multi-year remote sensing), with historical community-based experiences of managing the land and water in coastal areas. Connecting these through open and iterative dialogues could generate new perspectives and chances for the development and relevance of coastal areas.

6. Conclusions

The analysis revealed that there is no shortage of laws and rules to regulate land and water rights, restrictions and responsibilities. Nevertheless, the case of the sea fence also revealed that these contradict each other. This is rooted in the legal ambiguity when referring to coastal spaces, which include terrestrial areas immediately adjacent to moving coastlines and coastal water areas where land-based constructions are planned. Additionally, spatial land use plans affect land and water institutional mandates differently, creating ambiguity in the responsibilities and thus creating flexible and opportunistic strategies for all stakeholders, which may not serve the public interest. The controversies occur especially in the operationalisation of the strategies and the mandates of the different organisations, as they operate with varying systems, staff and styles, which are so rigid that reaching consensus is difficult. On the other hand, it also opens discretionary spaces for involved parties, which creates the potential for bypassing formal rules, opting for informality, and ultimately for corruption.

The values of the involved stakeholders which play a role in the controversies and contradictions are the perceived obviousness of adhering to the rule of law, the perceived necessity of public interests, the perceived relevance of cultural heritage, the perceived relevance and urgency of environmental sustainability and social justice and the perceived priority of profit maximisation and cost efficiency. As stakeholders rank these values in different orders, the value conflicts lead to insurmountable legal and institutional mandate operationalisation differences. The sea fences are a manifestation of insurmountable differences in legal and institutional mandates, instead of being the cause of these differences. In other words, the sea fences can emerge because the insurmountable differences create discretionary spaces for the involved parties.

Despite the stakeholders’ insurmountable differences in sea fences, the boundary objects of joint epistemic values and dialogues on development opportunities in coastal land and water areas can bring divergent positions closer together. Still, there also needs to be boundary work to foster public interests and mutually beneficial outcomes. This will require, however, closer discretionary spaces and/or more transparent operational processes.

Further research is necessary to investigate other cases and locations where sea fences have emerged, verify if similar value conflicts have occurred, and check if these have also led to informality and illegality. Additionally, one could expand the research to locations where fences have been created on land and assess if the role of coastal areas influences the outcomes in informality and illegality. Finally, what was not part of the scope of this study, yet still relevant, is to investigate how land and water rights can be unified into a single legal and institutional system such that ambiguities in land management and land use planning can be diminished.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, WdV.; methodology, WdV.; formal analysis, WdV, SP.; resources, X.X.; data curation, X.X.; writing—original draft preparation, W.dV, SP.; writing—review and editing, WdV, SP.; visualization, SP.; supervision, WdV.; funding acquisition, WdV. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SHGB |

Building Right Certificate |

| SHM |

Individual Right Certificate |

| PKKPR |

Location permit regarding spatial planning |

| RTRW |

Regional Spatial Planning |

| RDTR |

Detailed Plan of Spatial Planning |

| RZWP3K |

Zoning Plan for Coastal Areas and Small Islands |

| KKPRL |

Marine Spatial Utilization Suitability |

| The Ministry of ATR/BPN |

The Ministry of Agrarian and Spatial Planning/ National Land Agency Republic of Indonesia |

| The Ministry of KKP |

The Ministry of Marine and Fisheries Republic of Indonesia |

| The Ministry of KLHK |

The Ministry of Environment and Forestry |

References

- E. Warwick. Defensible Space. Int. Encycl. Hum. Geogr, Second Ed.; 2020; pp. 195-201. [CrossRef]

- A. Zamzuri, M. I. Hassan, and A. Abdul Rahman. Incorporating Adjacent Free Space (AFS) for marine spatial unit in 3D marine cadastre data model based on LADM. Land use policy 2024,, vol. 139, p. 107084. [CrossRef]

- S. Pinuji, W. T. de Vries, T. W. Rineksi, and W. Wahyuni. Is Obliterated Land Still Land? Tenure Security and Climate Change in Indonesia. Land 2023, vol. 12, no. 2, p. 478. [CrossRef]

- P. D. Soegiono and L. S. Arifin. Sustainable Aspects of Wall Constructions of Traditional Houses: Insights from the Bajau Tribe House, Indonesia. ISVS e-journal 2024, vol 11(2). [CrossRef]

- S. M. Noor, A. S. Pide, K. Lahae, and W. O. Intan. Challenges and Legal Certainty of Land Rights for the Bajo Tribe in the Context of SDG 15: Perspective of Building Use Rights and Ownership Rights. J. Lifestyle SDGs Rev. 2025, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. e02963–e02963, 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Løvschal and M. L. Gravesen. De-/fencing grasslands: Ongoing boundary making and unmaking in postcolonial Kenya. Land 2021, vol. 10, no. 8, p. 786. [CrossRef]

- D. C. North. Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge University Press: ., 1990.

- D. F. Channon and A. A. Caldart. McKinsey 7S model. In Wiley encyclopedia of management; John Wiley & Sons;2014; Volume 1.

- S. Kumar. The McKinsey 7S model helps in strategy implementation: A theoretical foundation. Tec. J. Manag. Stud. 2019, vol. 14, no. 1.

- T. Peters and R. H. Waterman Jr. McKinsey 7-S model. Leadersh. Excell. 2011, vol. 28, no. 10, p. 2011.

- Perjalanan Kasus Pagar Laut Tangerang dari Awal Ditemukan sampai SHGB Dicabut. Available online: https://www.kompas.com/tren/read/2025/01/23/050000065/perjalanan-kasus-pagar-laut-tangerang-dari-awal-ditemukan-sampai-shgb?page=all (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Looking For The Brain Behind The Tangerang Sea Fence. Available online: https://voi.id/en/tulisan-seri/453555 (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Polemik Pagar Laut di Tangerang, Nelayan Terancam!. Available online: https://fpk.unair.ac.id/polemik-pagar-laut-di-tangerang-nelayan-terancam/ (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Nusron: Sertifikat Pagar Laut Tangerang Konversi Girik ke SHGB-SHM. Available online: https://www.antaranews.com/berita/4616934/nusron-sertifikat-pagar-laut-tangerang-konversi-girik-ke-shgb-shm (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Soal Polemik Pagar Laut, Pakar UGM Sebut Perairan Kepulauan Tidak Boleh Dimiliki Individu atau Perusahaan. Available online: https://ugm.ac.id/id/berita/soal-polemik-pagar-laut-pakar-ugm-sebut-perairan-kepulauan-tidak-boleh-dimiliki-individu-atau-perusahaan/ (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- KPA Anggap Sertifikat HGB di Lokasi Pagar Laut Bentuk Akrobatik Hukum. Available online: https://www.tempo.co/hukum/kpa-anggap-sertifikat-hgb-di-lokasi-pagar-laut-bentuk-akrobatik-hukum-1197320 (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- U. Aemanah. Konsep Pagar Laut. In Kajian Pagar Laut dalam Perspektif Hukum Agraria , 1st ed.; A. A. Siagian, Ed; CV. Gita Lentera; Padang, Indonesia, 2025; pp. 1–12.

- F. Harvey and N. Chrisman. Boundary objects and the social construction of GIS technology. Environ. Plan. A 1998, vol. 30, no. 9, pp. 1683–1694. [CrossRef]

- J. Sapsed and A. Salter. Postcards from the edge: Local communities, global programs and boundary objects. Organ. Stud. 2024, vol. 25, no. 9, pp. 1515–1534. [CrossRef]

- S. L. Star and J. R. Griesemer. Institutional ecology,translations’ and boundary objects: Amateurs and professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907-39. Soc. Stud. Sci. 1989, vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 387–420.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Aligned with formal systems or clear focus

Aligned with formal systems or clear focus  Partial/ mixed alignment

Partial/ mixed alignment  Conflicting/ contrasting with others or misaligned with formal system

Conflicting/ contrasting with others or misaligned with formal system