Submitted:

30 April 2025

Posted:

02 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Overview

Survey Design

Survey Procedures

Statistical Analysis

| Country-Lever Ecological Variables | ||

| Domain & Variable(s) | Year | Data Source |

| Geographies | ||

| REGION: World Regions | 2024 | World Bank. [32] |

| Demography | ||

| LAND SIZE: Territory Size (SqKm) | 2021 | Food and Agriculture Organization, electronic files and web site. [33] |

| POPULATION: Population Size (n) | 2023 | United Nations Population Division; Eurostat: Demographic Statistics. [34] |

| RURAL: Rural Population Percentage (%) | 2023 | World Bank.[35] |

| Socio-development and democracy | ||

| DEMOCRACY INDEX: Democracy Index | 2022 | Economist Intelligence Unit (2006-2023) – processed by Our World in Data [36] |

| SDI: Socio-Demographic Index | 2021 | Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 (GBD 2021) Socio-Demographic Index (SDI) 1950–2021. [37] |

| Economics (Income Level Indicators) | ||

| INCOME LEVEL: Income Level | 2024 | World Bank. [32] |

| GNI: Gross National Income (US$/capita) | 2022 | World Bank national accounts data, and OECD National Accounts data files. [38] |

| Health-Economic Indicators | ||

| GOVERNMENT FUNDED: Domestic General Government Health Expenditure (%) | 2021 | World Health Organization Global Health Expenditure database. [39] |

| EXPENDITURES: Current Health Expenditure Per Capita (US$/capita) | 2021 | World Health Organization Global Health Expenditure database. [40] |

| Population Needs | ||

| YLDs RATE: Years Lived with Disability Rate for Mental Disorders and Substance Disorders | 2021 | Global Burden of Disease. [41] |

| YLDs PERCENT: Years Lived with Disability Percent for Mental Disorders and Substance Disorders | 2021 | Global Burden of Disease. [41] |

| INDIVIDUAL-RESPONDENT socio-demographic variables: available from the survey | ||

| Years of work: Years of Experience Working in Occupational Therapy | ||

| MH service load: Volume of Work that Addresses People with Specific Mental Health Needs | ||

| Self-rated competency: Level of Preparation/Training to Work with People with Mental Health Heeds | ||

| Fieldwork in MH: Fieldwork/practice placement in mental health during education | ||

Results

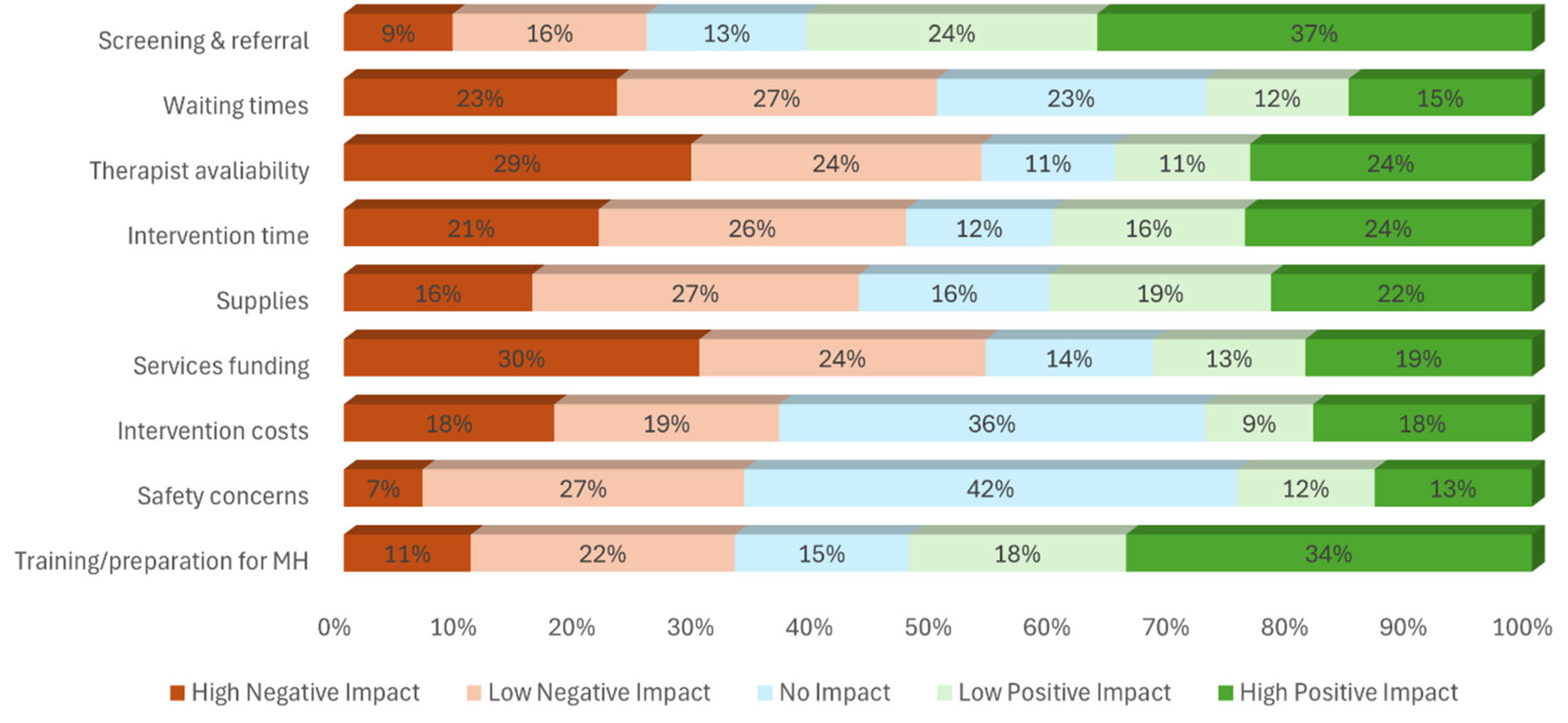

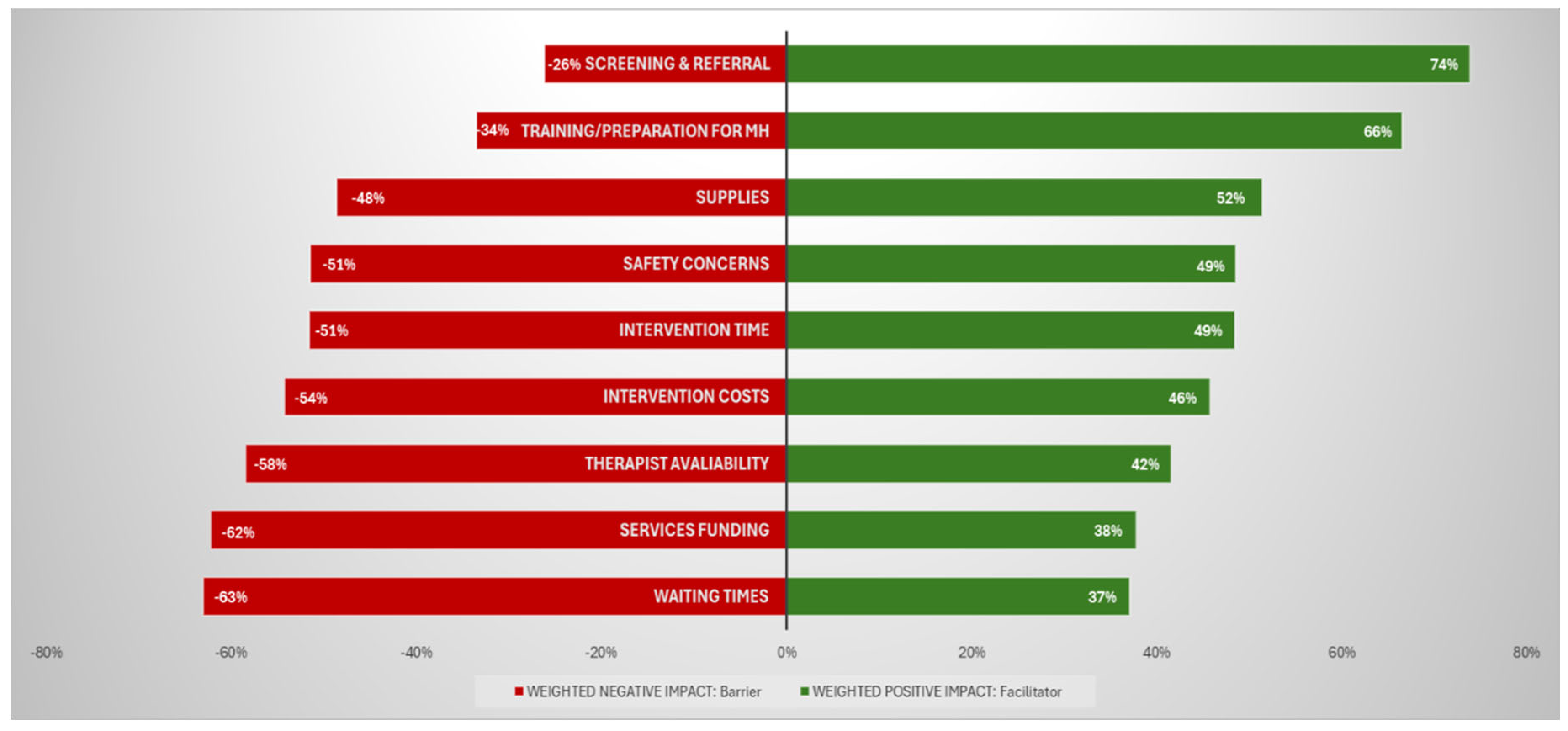

1. Factors Rated as Positively or Negatively Affecting the Practice in MH

2. How the Rated Factors Vary Across Respondent Contexts

Discussion

Limitations

Conclusion

Funding

Consent for publication

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Competing interests

Author Contributions Statement

Availability of data and materials

Acknowledgements

Abbreviations

| AIC | Akaike Information Criterion |

| MH | Mental Health |

| WFOT | World Federation of Occupational Therapists |

| SDI | Socio-Demographic Index |

References

- World Federation of Occupational Therapists. Defintions of occupational therapy from member organizations Online: 2013.

- World Federation of Occupational Therapists. Occupational Therapy Human Resources. Geneva: 2021.

- Jesus TS, Mani K, Bhattacharjya S, Kamalakannan S, von Zweck C, Ledgerd R. Situational analysis for informing the global strengthening of the occupational therapy workforce. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2023;38(2):527-35. Epub 20221220. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jesus TS, Mani K, von Zweck C, Kamalakannan S, Bhattacharjya S, Ledgerd R, et al. Type of Findings Generated by the Occupational Therapy Workforce Research Worldwide: Scoping Review and Content Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(9). Epub 20220427. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Occupational Therapy Association. Workforce and salary survey Bethesda: AOTA; 2019.

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational employment and wage statistics Washinghton, DC2023. Available from: https://www.bls.gov/oes/2022/may/naics5_621330.htm.

- National Institute of Mental Health. Mental Illness: NIH; 2024. Available from: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/mental-illness.

- Kaiser Family Foundation. Mental Health Care Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs) 2024. Available from: https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/mental-health-care-health-professional-shortage-areas-hpsas/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Percent%20of%20Need%20Met%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D.

- GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9(2):137-50. Epub 20220110. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endale T, Qureshi O, Ryan GK, Esponda GM, Verhey R, Eaton J, et al. Barriers and drivers to capacity-building in global mental health projects. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2020;14(1):89. Epub 20201203. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakuma R, Minas H, van Ginneken N, Dal Poz MR, Desiraju K, Morris JE, et al. Human resources for mental health care: current situation and strategies for action. Lancet. 2011;378(9803):1654-63. Epub 20111016. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Global Health Observatory. Occupational therapists in mental health sector (per 100,000) 2019. Available from: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/occupational-therapists-in-mental-health-sector-(per-100-000).

- Sedgwick A, Cockburn L, Trentham B. Exploring the mental health roots of occupational therapy in Canada: a historical review of primary texts from 1925-1950. Can J Occup Ther. 2007;74(5):407-17. [PubMed]

- Shepherd HA, Jesus TS, Nalder E, Dabbagh A, Colquhoun H. Occupational Therapy Research Publications From 2001 to 2020 in PubMed: Trends and Comparative Analysis with Physiotherapy and Rehabilitation. OTJR (Thorofare N J). 2024:15394492241292438. Epub 20241106. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Read H, Zagorac S, Neumann N, Kramer I, Walker L, Thomas E. Occupational Therapy: A Potential Solution to the Behavioral Health Workforce Shortage. Psychiatr Serv. 2024;75(7):703-5. Epub 20240207. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krupa T, Fossey E, Anthony WA, Brown C, Pitts DB. Doing daily life: how occupational therapy can inform psychiatric rehabilitation practice. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2009;32(3):155-61. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galderisi S, Heinz A, Kastrup M, Beezhold J, Sartorius N. Toward a new definition of mental health. World Psychiatry. 2015;14(2):231-3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Occupational Therapy Association. Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain and Process-Fourth Edition. Am J Occup Ther. 2020;74(Supplement_2):7412410010p1-p87. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keptner K, Lambdin-Pattavina C, Jalaba T, Nawotniak S, Cozzolino M. Preparing for and Responding to the Current Mental Health Tsunami: Embracing Mary Reilly's Call to Action. Am J Occup Ther. 2024;78(1). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Federation Of Occupational, T. POSITION STATEMENT: Occupational Therapy and Mental Health. 2019.

- Jesus TS, Landry MD, Dussault G, Fronteira I. Classifying and Measuring Human Resources for Health and Rehabilitation: Concept Design of a Practices- and Competency-Based International Classification. Phys Ther. 2019;99(4):396-405. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilburn VG, Hoss A, Pudeler M, Beukema E, Rothenbuhler C, Stoll HB. Receiving Recognition: A Case for Occupational Therapy Practitioners as Mental and Behavioral Health Providers. Am J Occup Ther. 2021;75(5). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gréaux M, Moro MF, Kamenov K, Russell AM, Barrett D, Cieza A. Health equity for persons with disabilities: a global scoping review on barriers and interventions in healthcare services. Int J Equity Health. 2023;22(1):236. Epub 20231113. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butura AM, Ryan GK, Shakespeare T, Ogunmola O, Omobowale O, Greenley R, et al. Community-based rehabilitation for people with psychosocial disabilities in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review of the grey literature. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2024;18(1):13. Epub 20240314. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- To Dutka J, Gans BM, Bracciano A, Bharadwaj S, Akinwuntan A, Mauk K, et al. Delivering Rehabilitation Care Around the World: Voices From the Field. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2023;104(9):1385-93. [CrossRef]

- Naicker AS, Htwe O, Tannor AY, De Groote W, Yuliawiratman BS, Naicker MS. Facilitators and Barriers to the Rehabilitation Workforce Capacity Building in Low- to Middle-Income Countries. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2019;30(4):867-77. Epub 20190824. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharjya S, Curtis S, Kueakomoldej S, von Zweck C, Russo G, Mani K, et al. Developing a Global Strategy for strengthening the occupational therapy workforce: a two-phased mixed-methods consultation of country representatives shows the need for clarifying task-sharing strategies. Hum Resour Health. 2024;22(1):62. Epub 20240905. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jesus TS vZC, Bhattacharjya S, Mani K, Kamalakannan S, Ledgerd R. WFOT Global Strategy for the Occupational Therapy Workforce. Geneva: WFOT, 2024.

- Jesus TS, Mani K, von Zweck C, Bhattacharjya S, Kamalakannan S, Ledgerd R. The Global Status of Occupational Therapy Workforce Research Worldwide: A Scoping Review. Am J Occup Ther. 2023;77(3). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Mental Health Atlas. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240036703.

- Jesus TS, Landry MD, Hoenig H, Dussault G, Koh GC, Fronteira I. Is Physical Rehabilitation Need Associated With the Rehabilitation Workforce Supply? An Ecological Study Across 35 High-Income Countries. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2022;11(4):434-42. Epub 20220401. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups 2024 [October 25, 2024]. Available from: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups.

- World Bank. Land area (sq. km) 2021 [October 25, 2024]. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/AG.LND.TOTL.K2.

- World Bank. Population, total 2023 [October 25, 2024]. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL.

- World Bank. Rural population (% of total population) 2023 [October 25, 2024]. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.RUR.TOTL.ZS?end=2023&start=1960&view=chart.

- Our World in Data. Democracy index 2023 [October 25, 2024]. Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/democracy-index-eiu?tab=table#sources-and-processing.

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 (GBD 2021) Socio-Demographic Index (SDI) 1950–2021 2021 [October 25, 2024]. Available from: https://ghdx.healthdata.org/record/global-burden-disease-study-2021-gbd-2021-socio-demographic-index-sdi-1950%E2%80%932021.

- World Bank. GNI per capita, Atlas method (current US$) 2023 [October 25, 2024]. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GNP.PCAP.CD.

- World Bank. Domestic general government health expenditure (% of current health expenditure) 2021 [October 25, 2024]. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.GHED.CH.ZS.

- World Bank. Current health expenditure per capita (current US$) 2021 [October 25, 2024]. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.CHEX.PC.CD?view=chart.

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). Global Burden of Disease 2021 [October 25, 2024]. Available from: https://www.healthdata.org/research-analysis/gbd.

- Mao HF, Chang LH, Tsai AY, Huang WN, Wang J. Developing a Referral Protocol for Community-Based Occupational Therapy Services in Taiwan: A Logistic Regression Analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11(2):e0148414. Epub 20160210. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heasman D, Morley M. Introducing Prioritisation Protocols to Promote Efficient and Effective Allocation of Mental Health Occupational Therapy Resources. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2012;75(11):522-6. [CrossRef]

- Ige JJ, Hunt DF. Quality improvement project to improve the standardisation and efficiency of occupational therapy initial contact and assessment within a mental health inpatient service. BMJ Open Quality. 2022;11(4):e001932. [CrossRef]

- Loubani K, Polo KM, Baxter MF, Rand D. Identifying Facilitators of and Barriers to Referrals to Occupational Therapy Services by Israeli Cancer Health Care Professionals: A Qualitative Study. Am J Occup Ther. 2024;78(1). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Royal College of Occupational Therapists. Occupational therapy under pressure: Workforce survey findings 2022–2023. Report, Royal College of Occupational Therapy UK; 2023.

- Carey G, Malbon E, Carey N, Joyce A, Crammond B, Carey A. Systems science and systems thinking for public health: a systematic review of the field. BMJ Open. 2015;5(12):e009002. Epub 20151230. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jesus TS, Landry MD, Dussault G, Fronteira I. Human resources for health (and rehabilitation): Six Rehab-Workforce Challenges for the century. Hum Resour Health. 2017;15(1):8. Epub 20170123. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mertala SM, Kanste O, Keskitalo-Leskinen S, Juntunen J, Kaakinen P. Job Satisfaction among Occupational Therapy Practitioners: A Systematic Review of Quantitative Studies. Occup Ther Health Care. 2022;36(1):1-28. Epub 20210819. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scanlan JN, Meredith P, Poulsen AA. Enhancing retention of occupational therapists working in mental health: relationships between wellbeing at work and turnover intention. Aust Occup Ther J. 2013;60(6):395-403. Epub 20130901. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster F, Palexas S, Hitch D. Early career programs for mental health occupational therapists: A survey of current practice. Aust Occup Ther J. 2022;69(3):255-64. Epub 20220104. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scanlan JN, Pépin G, Haracz K, Ennals P, Webster JS, Meredith PJ, et al. Identifying educational priorities for occupational therapy students to prepare for mental health practice in Australia and New Zealand: Opinions of practising occupational therapists. Aust Occup Ther J. 2015;62(5):286-98. Epub 20150507. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scanlan JN, Meredith PJ, Haracz K, Ennals P, Pépin G, Webster JS, et al. Mental health education in occupational therapy professional preparation programs: Alignment between clinician priorities and coverage in university curricula. Aust Occup Ther J. 2017;64(6):436-47. Epub 20170629. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dillon MB, Dillon TH, King RM, Chamberlin JL. Interfacing with Community Mental Health Services: Opportunities for Occupational Therapy and Level II Fieldwork Education. Occup Ther Health Care. 2007;21(1-2):91-104. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Imam MH, Jahan I, Das MC, Muhit M, Akbar D, Badawi N, et al. Situation analysis of rehabilitation services for persons with disabilities in Bangladesh: identifying service gaps and scopes for improvement. Disabil Rehabil. 2022;44(19):5571-84. Epub 20210627. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heim E, Henderson C, Kohrt BA, Koschorke M, Milenova M, Thornicroft G. Reducing mental health-related stigma among medical and nursing students in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2019;29:e28. Epub 20190401. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javed A, Lee C, Zakaria H, Buenaventura RD, Cetkovich-Bakmas M, Duailibi K, et al. Reducing the stigma of mental health disorders with a focus on low- and middle-income countries. Asian J Psychiatr. 2021;58:102601. Epub 20210213. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray LK, Skavenski S, Bass J, Wilcox H, Bolton P, Imasiku M, et al. Implementing Evidence-Based Mental Health Care in Low-Resource Settings: A Focus on Safety Planning Procedures. J Cogn Psychother. 2014;28(3):168-85. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo G, Jesus TS, Deane K, Osman AY, McCoy D. Epidemics, Lockdown Measures and Vulnerable Populations: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review of the Evidence of Impacts on Mother and Child Health in Low-and Lower-Middle-Income Countries. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2022;11(10):2003-21. Epub 20211107. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2021 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990-2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet. 2024;403(10440):2133-61. Epub 20240417. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Question (common trunk) | Survey items: List of factors affecting the practice in mental health to be rates | Possible Rates |

| Please rate the degree to which the following factors affect your ability to provide quality occupational therapy services for people with mental health needs: | Screening & referral: Screening and referral mechanisms to identify people needing occupational therapy | - “High Negative Impact” - “Low Negative Impact” - “No Impact” “Low Positive Impact” - “High Positive Impact” OR - “Unknown” - “Not applicable” |

| Waiting times: Wait time for occupational therapy intervention | ||

| Therapist availability: Availability of occupational therapists | ||

| Intervention time: Availability of time to provide needed intervention | ||

| Supplies: Availability and suitability of equipment / supplies | ||

| Services funding: Funding for occupational therapy services | ||

| Intervention costs: costs of occupational therapy intervention for the user | ||

| Safety concerns: Personal safety concerns | ||

| Training/preparation for MH: Training/preparation to provide occupational therapy for people with mental health needs |

|

Survey Item (whole-model p value) |

Predictor | VIF | Estimate | 95% CI | P value | |

| Screening & referral (0.0607) |

Years of work | 1.00 | 0.0742 | -0.0029 | 0.1513 | 0.0594 |

| Waiting times (0.0021*) |

POPULATION | 1.11 | -3.76E-10 | -1E-09 | 2.46E-10 | 0.2357 |

| SDI | 1.88 | -3.2539 | -5.0493 | -1.4584 | 0.0004** | |

| DEMOCRACY | 2.02 | 0.1424 | -0.0085 | 0.2934 | 0.0644 | |

| YLDs PERCENT | 1.05 | -4.4543 | -9.6735 | 0.7648 | 0.0944 | |

| MH service load | 1.02 | -0.1244 | -0.2557 | 0.0070 | 0.0634 | |

| Therapist availability (0.0002*) |

INCOME | 1.00 | -0.0638 | -0.2650 | 0.1374 | 0.5343 |

| LAND | 1.00 | 6.54E-08 | 3.12E-08 | 9.95E-08 | 0.0002** | |

| Years of work | 1.00 | 0.0859 | 0.0132 | 0.1586 | 0.0205* | |

| Intervention time (0.0004*) |

LAND | 1.04 | 6.27E-08 | 2.87E-08 | 9.66E-08 | 0.0003** |

| GOVERNMENT | 1.04 | 0.0093 | 0.0010 | 0.0177 | 0.0291* | |

| Services funding (0.0002*) |

REGION | 1.64 | 0.0630 | -0.0321 | 0.1582 | 0.1943 |

| POPULATION | 1.32 | -8.53E-10 | -1.5E-09 | -1.6E-10 | 0.0158* | |

| LAND | 1.49 | 7.11E-08 | 2.95E-08 | 1.13E-07 | 0.0008** | |

| SDI | 1.78 | -2.0354 | -3.7459 | -0.3250 | 0.0197* | |

| GOVERNMENT | 1.87 | 0.0119 | 0.0004 | 0.0234 | 0.0417* | |

| MH service load | 1.01 | -0.0991 | -0.2284 | 0.0303 | 0.1334 | |

| Fieldwork in MH | 1.05 | 0.1573 | -0.0381 | 0.3526 | 0.1146 | |

| Intervention Costs (<.0001*) |

INCOME | 2.31 | -0.4692 | -0.7867 | -0.1516 | 0.0038** |

| POPULATION | 1.38 | -5.87E-10 | -1.3E-09 | 1.13E-10 | 0.1003 | |

| LAND | 1.47 | 5.21E-08 | 7.65E-09 | 9.66E-08 | 0.0216* | |

| DEMOCRACY | 1.88 | -0.1010 | -0.2500 | 0.0481 | 0.1845 | |

| YLDs RATE | 1.86 | 0.0005 | 0.0002 | 0.0008 | 0.0039** | |

| MH service load | 1.01 | -0.1510 | -0.2917 | -0.0102 | 0.0355* | |

| Fieldwork in MH | 1.03 | 0.2397 | 0.0302 | 0.4493 | 0.0249* | |

| Safety concerns (<.0001*) |

INCOME | 6.47 | -1.3219 | -1.8594 | -0.7845 | <.0001** |

| SDI | 8.64 | 11.0802 | 7.0913 | 15.0692 | <.0001** | |

| DEMOCRACY | 1.93 | -0.1249 | -0.2754 | 0.0256 | 0.1038 | |

| EXPENDITURES | 4.05 | -0.0001 | -0.0002 | 0.0000 | 0.0098* | |

| GOVERNMENT | 2.37 | 0.0120 | -0.0013 | 0.0254 | 0.0773 | |

| YLDs RATE | 2.45 | 0.0009 | 0.0005 | 0.0012 | <.0001** | |

| Years of work | 1.02 | -0.0911 | -0.1695 | -0.0127 | 0.0227* | |

| Fieldwork in MH | 1.06 | 0.1845 | -0.0199 | 0.3889 | 0.0768 | |

| Training/preparation for MH (<.0001*) | INCOME | 1.79 | -0.1004 | -0.3673 | 0.1665 | 0.4610 |

| GOVERNMENT | 1.78 | -0.0096 | -0.0207 | 0.0015 | 0.0911 | |

| Years of work | 1.07 | 0.1032 | 0.0275 | 0.1790 | 0.0075** | |

| Preparation | 1.06 | 0.1542 | -0.0096 | 0.3179 | 0.0650 | |

| Fieldwork in MH | 1.03 | -0.2778 | -0.4670 | -0.0885 | 0.004** | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).