Submitted:

30 April 2025

Posted:

30 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Characterization of Materials

2.3. Synthesis Methods

2.3.1. Functionalization of Merrifield Resin with 1 ,2-Ethanedithiol and 1,2-Benzenedithiol

2.3.2. Functionalization of Merrifield Resin with 2-Benzimidazolylthio Acetic Acid

2.3.3. Adsorption Studies

2.3.4. Competitive Study

3. Results

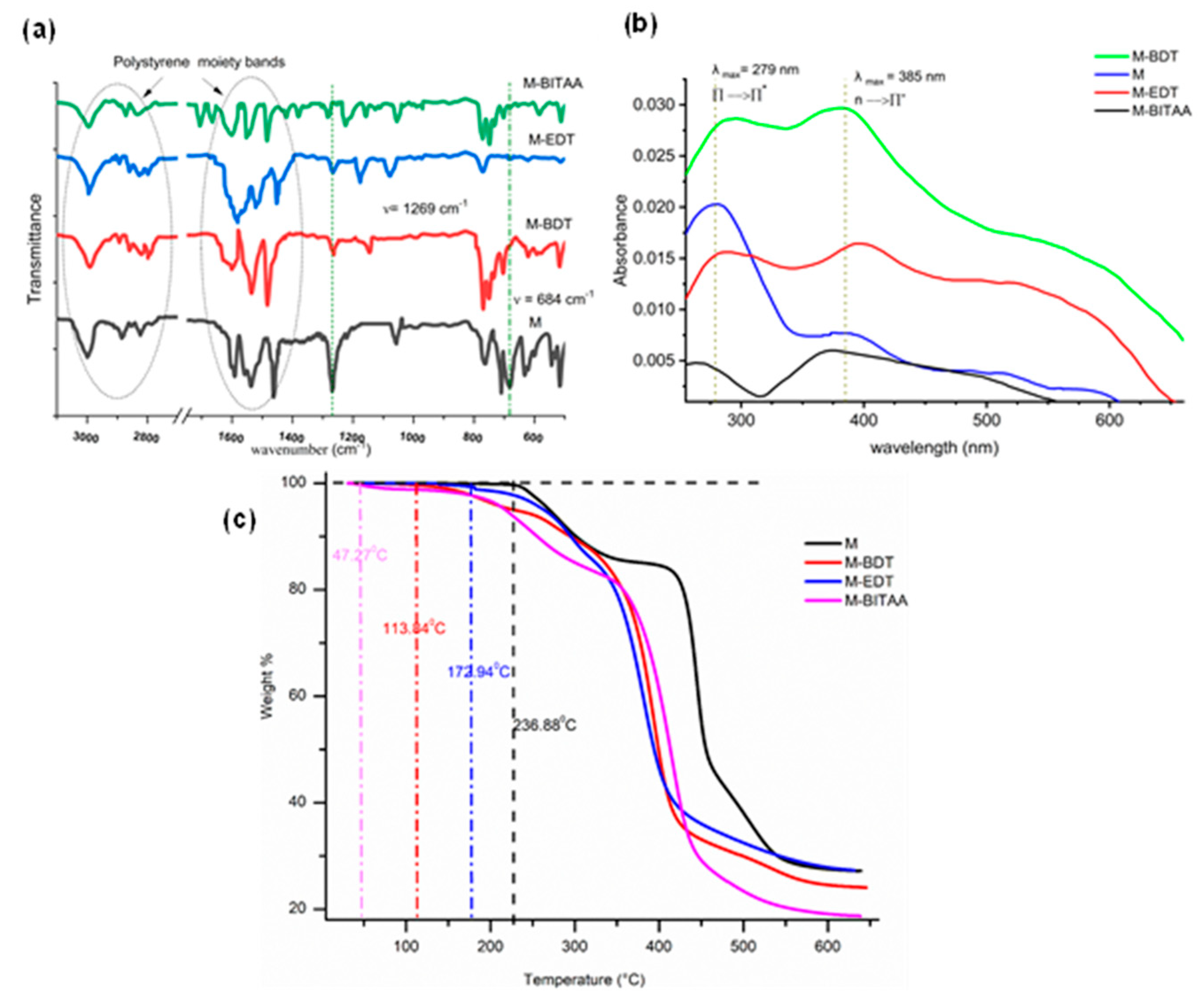

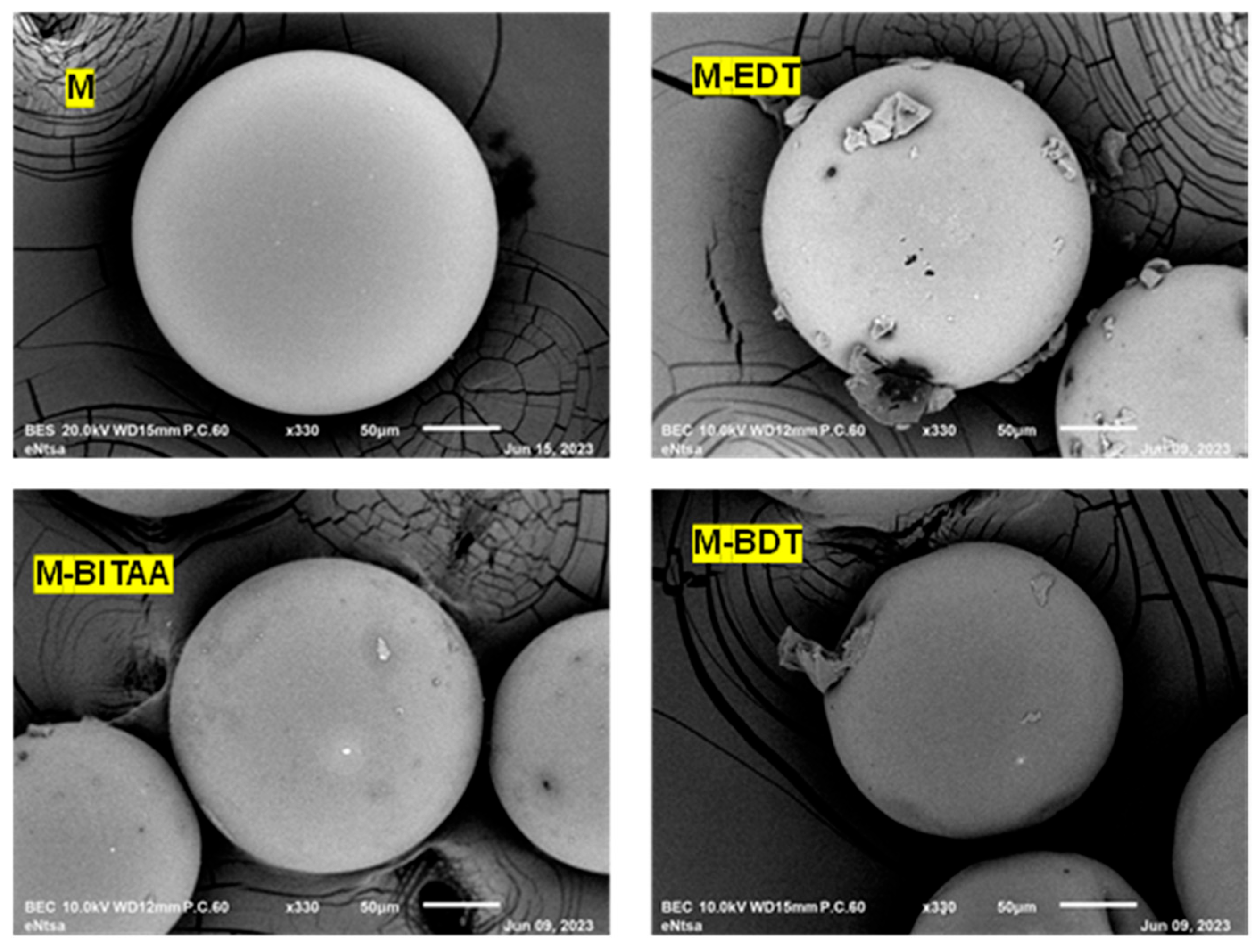

3.1. Characterization of Materials

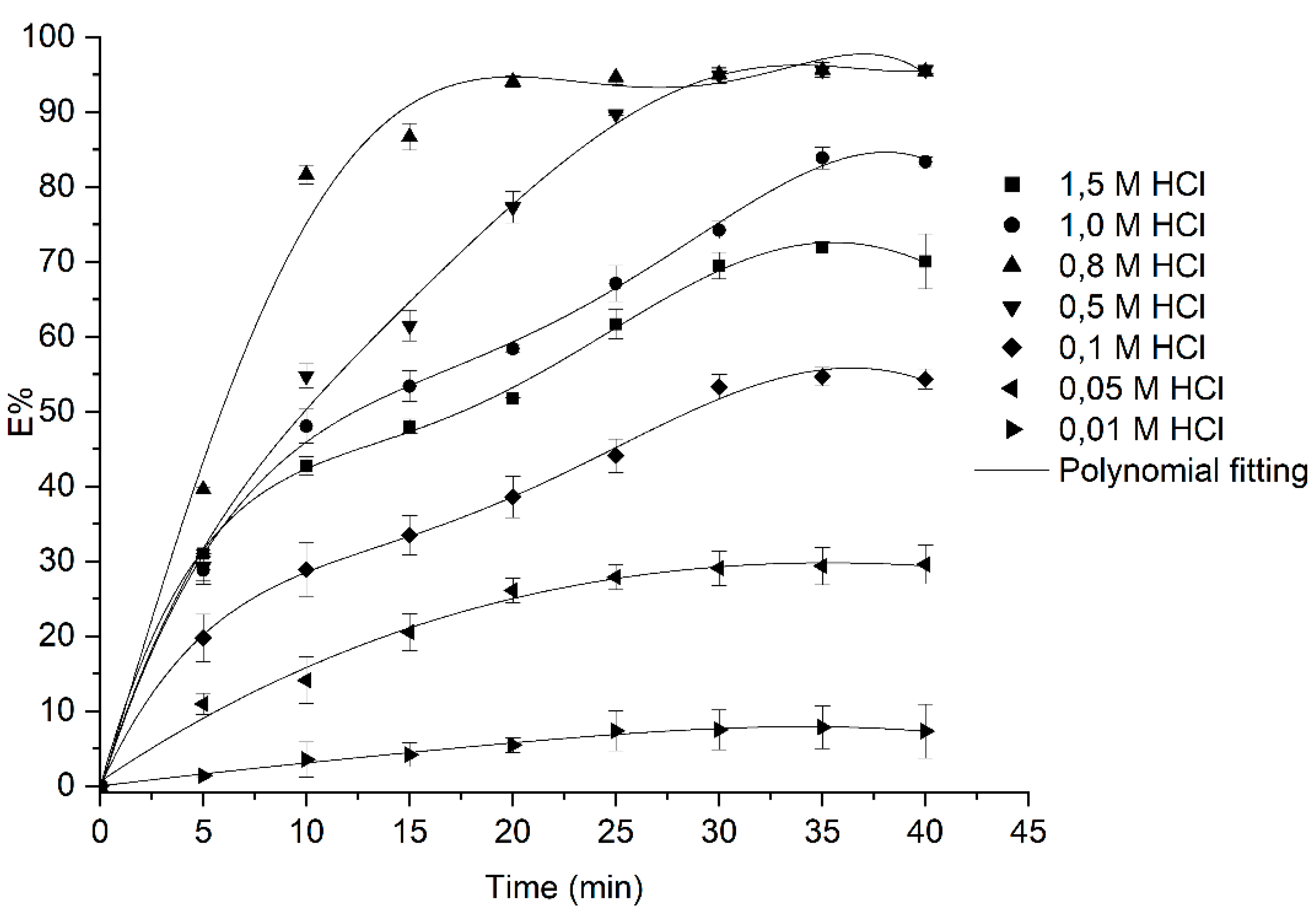

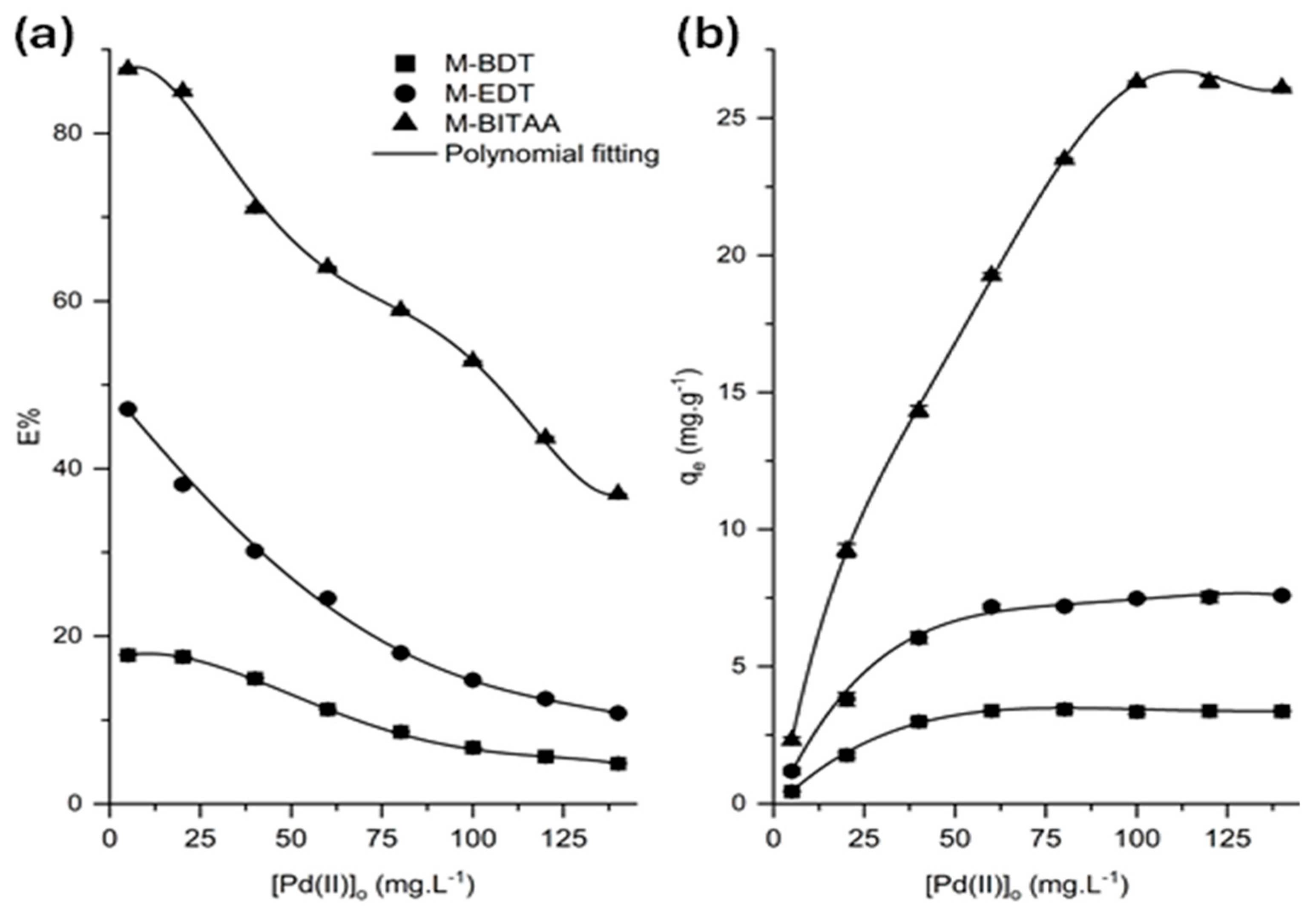

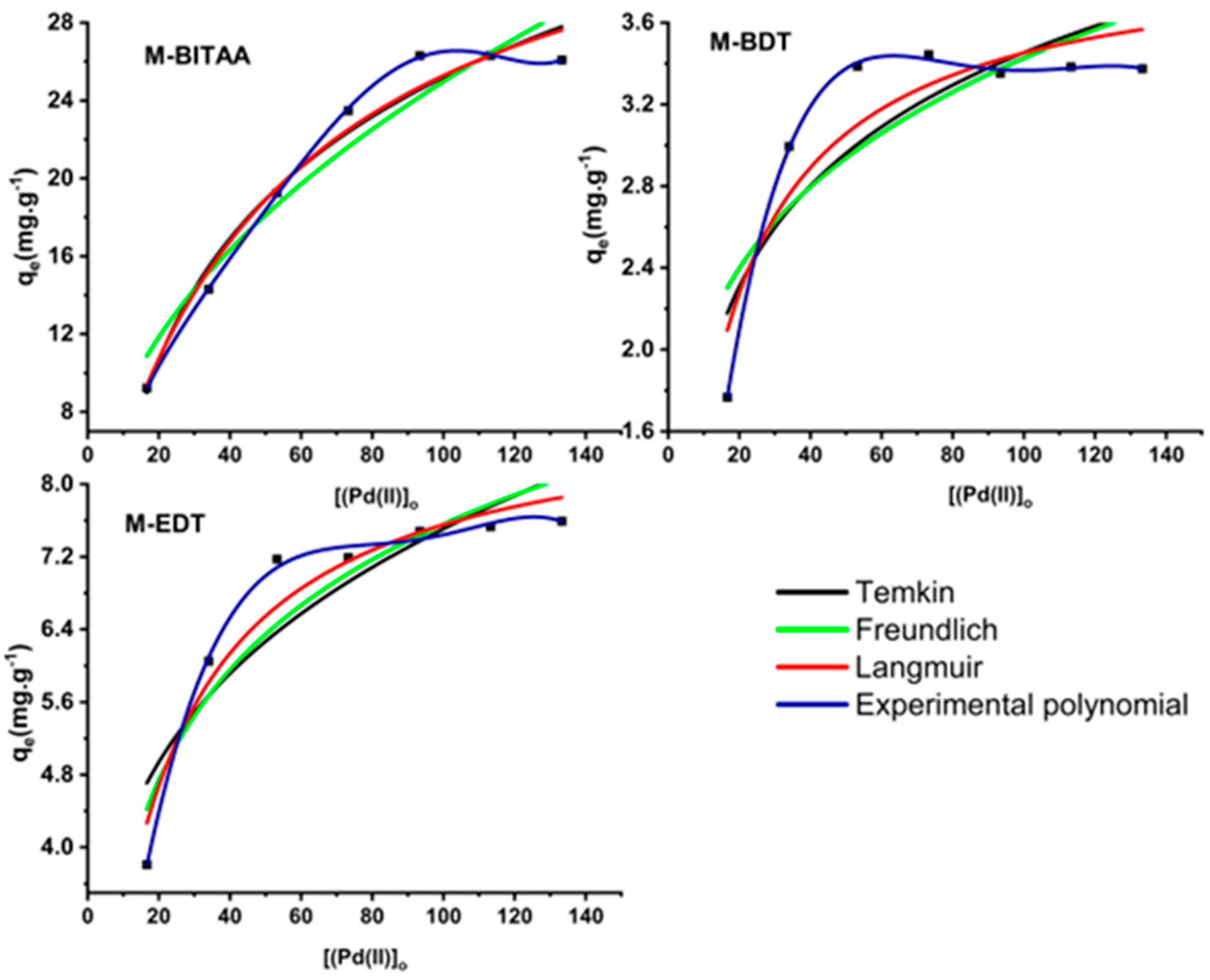

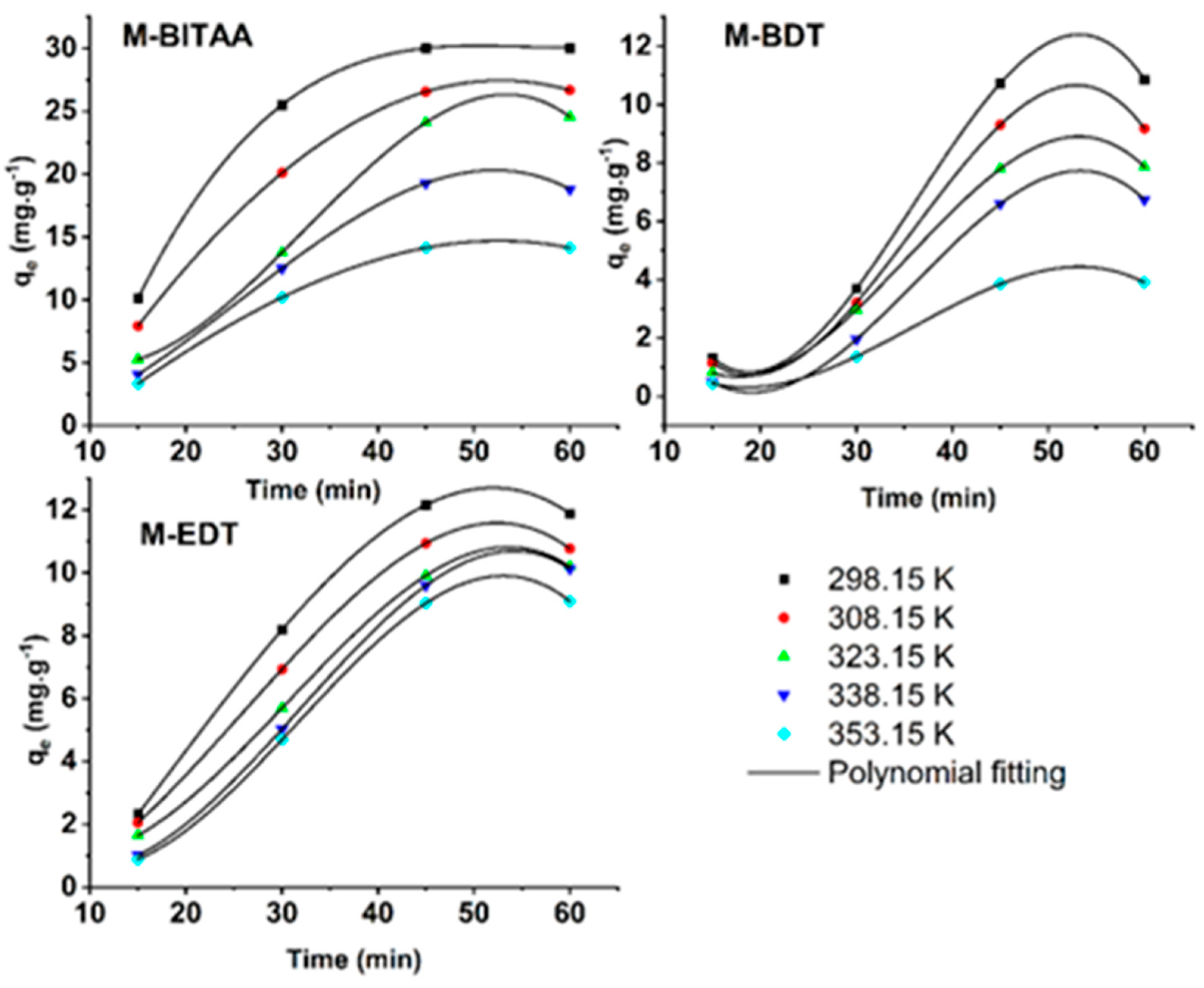

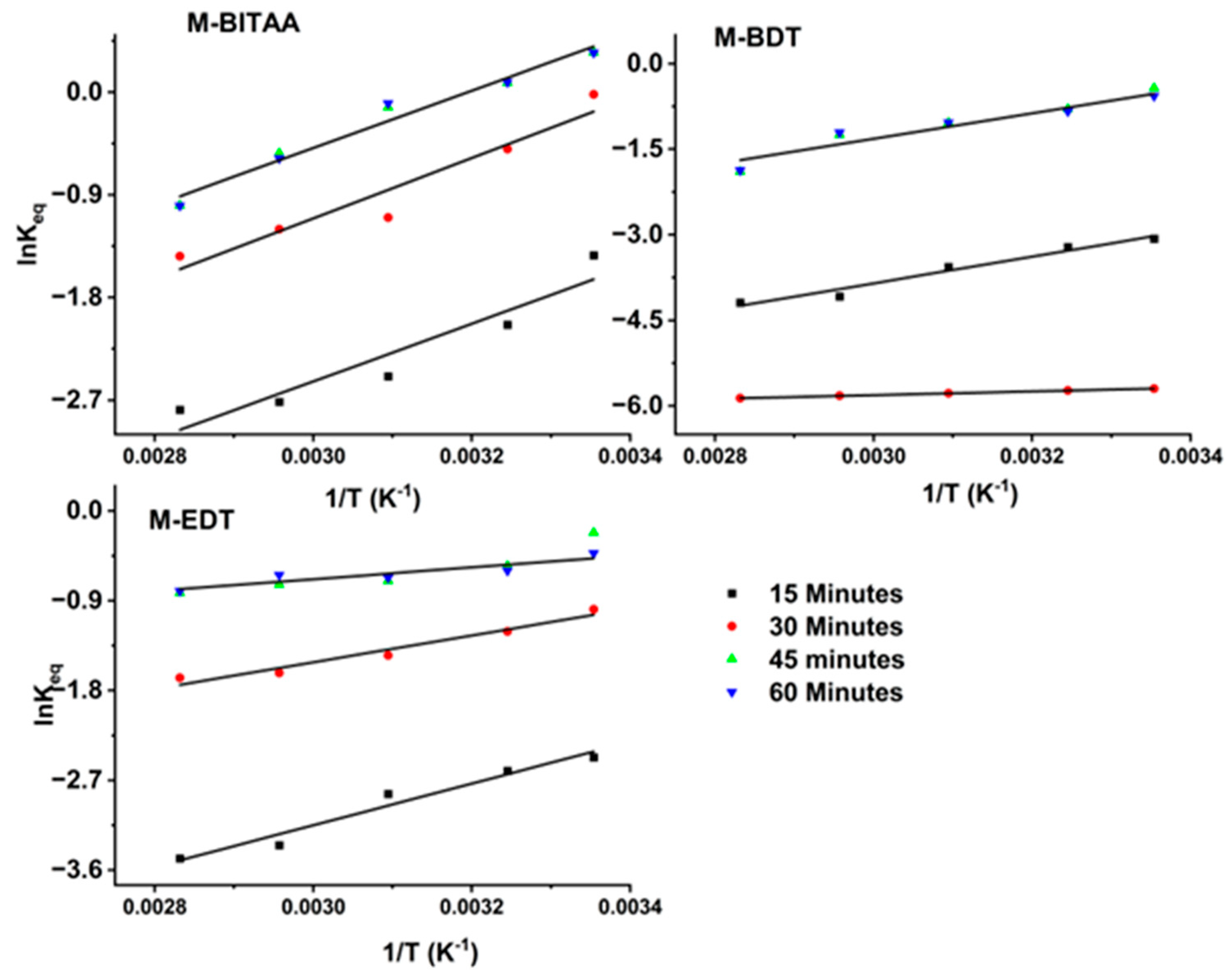

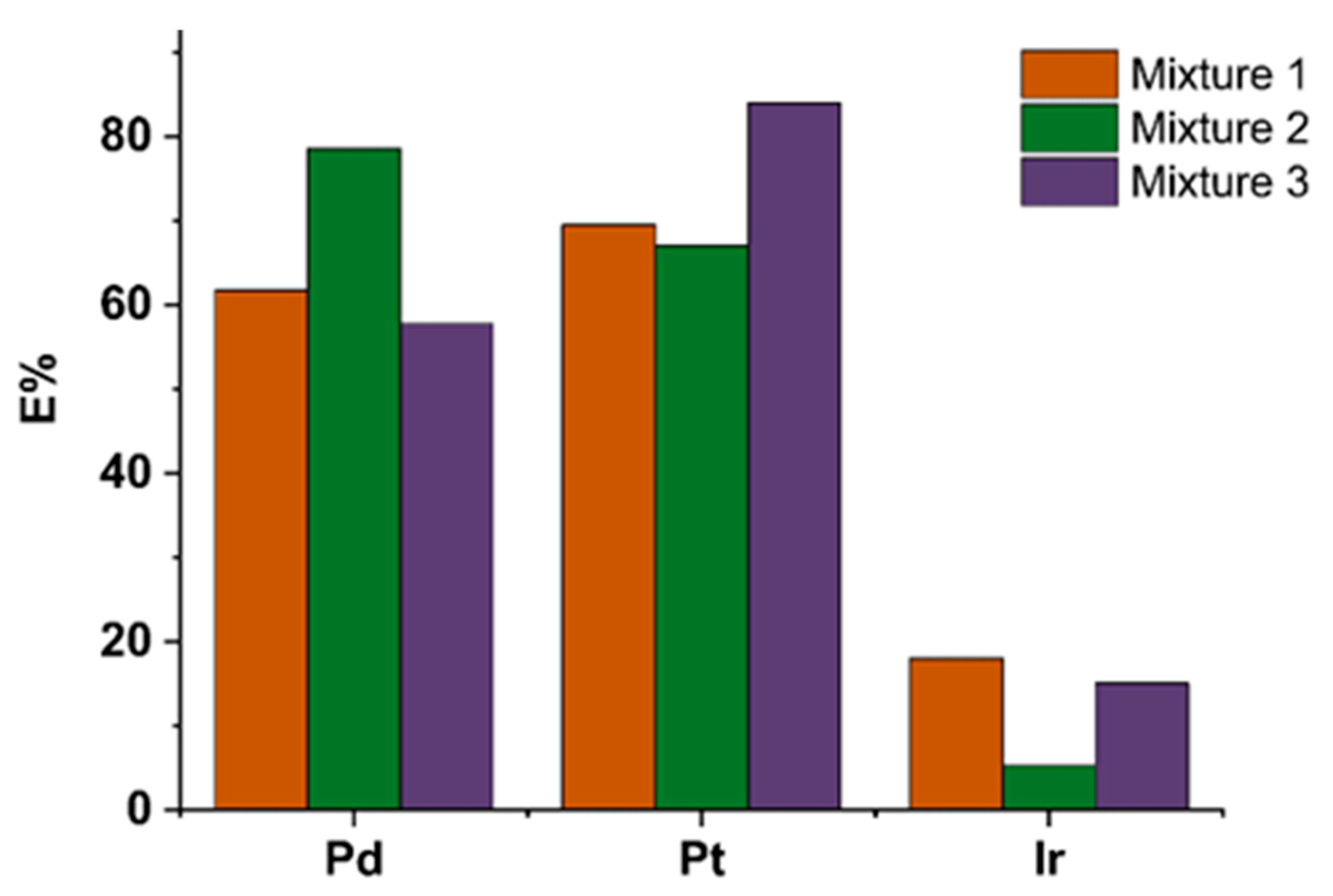

3.2. Adsorption Studies

4. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hughes, A.E. , Haque, N. , Northey, S.A., & Giddey, S. Platinum group metals: A review of resources, production and usage with a focus on catalysts. Resources 2021, 10, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulliani, S. , Volpe, M. , Messineo, A., & Volpe, R. Recovery of metals and valuable chemicals from waste electric and electronic materials: a critical review of existing technologies. RSC Sustainability 2023, 1, 1085–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, M. Recovery of metals and nonmetals from electronic waste by physical and chemical recycling processes. Waste Management 2016, 100, 64–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnan, S. , Zulkapli, N. S., Kamyab, H., Taib, S.M., Din, M.F. B. M., Abd Majid, Z.,Chaiprapat, S., Kenzo, I., Ichikawa, Y., Nasrullah, M., Chelliapan,S., & Othman, N. Current technologies for recovery of metals from industrial wastes: An overview. Environmental Technology & Innovation 2021, 22, 101525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.C. , Hong, H. J., Chung, K.W., & Kim, S. Separation of platinum, palladium and rhodium from aqueous solutions using ion exchange resin: A review. Separation and Purification Technology 2020, 246, 116896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siu, W.K. M. (2004). Applications and Microwave Assisted Synthesis of Poly (ethylene glycol) modified Merrifield resins.

- Zviagin, I.M. , Khimchenko, S.V., Blank, T.A., Shcherbakov, I.K., Bryleva, E.Y., Bunina, Z.Y., Sofronov, D,S., Belikov, K.N., & Chebanov, V.A. (2018). Merrifield resin-linked polyazole-based sorbent for heavy metal ions extraction from water. Functional Materials.

- Fontenot, S.A. , Carter, T.G., Johnson, D.W., Addleman, R.S., Warner, M.G., Yantasee, W., Warner, C.L., Fryxell, G,E.,& Bays, J.T. Nanostructured Materials for Selective Collection of Trace-Level Metals from Aqueous Systems. Trace Analysis with Nanomaterials 2010, 191-221.

- Fernández-Puig, S. , Luaces-Alberto, M.D., Vallejo-Becerra, V., Teran, A.O., Chávez-Ramírez, A.U., & González, A.V. (2019). Modified Merrifield’s resin materials used in capturing of Pb(II) ions in water. Materials Research Express, 2019; 6, 115104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X. , Hao, J., Xi, Z., Liu, T., Lin, Y., & Xu, B. Investigation of low concentration SO2 adsorption performance on different amine-modified Merrifield resins. Atmospheric Pollution Research, 2019, 10, 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pustam, A.N. , & Alexandratos, S. D. Engineering selectivity into polymer-supported reagents for transition metal ion complex formation. Reactive and Functional Polymers 2010, 70, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, T. , Park, Y. , & Yi, J. Highly selective adsorption of Pt2+ and Pd2+ using thiol-functionalized mesoporous silica. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research 2004, 43, 1478–1484. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.L. , Sun, M. , Shi, Y.H., Zhou, X.M., Zhang, P.Z., Jia, A.Q., & Zhang, Q.F. Functional modification, self-assembly and application of calix [4] resorcinarenes. Journal of Inclusion Phenomena and Macrocyclic Chemistry 2022, 102, 201–233. [Google Scholar]

- Tofan, L. , & Wenkert, R. Chelating polymers with valuable sorption potential for development of precious metal recycling technologies. Reviews in Chemical Engineering 2022, 38, 167–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F. , Ye, G. , Yi, R., Sun, T., Xu, C., & Chen, J. Novel polyazamacrocyclic receptor decorated core–shell superparamagnetic microspheres for selective binding and magnetic enrichment of palladium: synthesis, adsorptive behavior and coordination mechanism. Dalton transactions 2016, 45, 9553–9564. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fayemi, O.E. , Ogunlaja, A. S., Kempgens, P.F., Antunes, E., Torto, N., Nyokong, T., & Tshentu, Z.R. Adsorption and separation of platinum and palladium by polyamine functionalized polystyrene-based beads and nanofibers. Minerals Engineering 2013, 53, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kancharla, S. , & Sasaki, K. Selective extraction of precious metals from simulated automotive catalyst waste and their conversion to carbon supported PdPt nanoparticle catalyst. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2023, 665, 131179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mildan, E. , & Gülfen, M. Equilibrium, kinetics, and thermodynamics of Pd (II) adsorption onto poly (m-aminobenzoic acid) chelating polymer. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2015, 132.

- Sari, A. , Mendil, D., Tuzen, M., & Soylak, M. Biosorption of palladium (II) from aqueous solution by moss (Racomitrium lanuginosum) biomass: Equilibrium, kinetic and thermodynamic studies. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2009, 162(2-3), 874-879.

- Matsumoto, K. , Shimazaki, H. , Miyamoto, Y., Shimada, K., Haga, F., Yamada, Y., Miyazawa, H., Nishiwaki, K,.& Kashimura, S. Simple and convenient synthesis of esters from carboxylic acids and alkyl halides using tetrabutylammonium fluoride. Journal of Oleo Science 2014, 63, 539–544. [Google Scholar]

- Majavu, A. , Ogunlaja, A. S., & Tshentu, Z.R. Separation of rhodium(III) and iridium(IV) chlorido complexes using polymer microspheres functionalised with quaternary diammonium groups. Separation Science and Technology 2017, 52, 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Dardouri, M. , Ammari, F., & Meganem, F. Aminoalkylated Merrifield resins reticulated by tris-(2-chloroethyl) phosphate for cadmium, copper, and iron(II) extraction. International Journal of Polymer Science 2015, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. , Li, P. , Zhang, Y., Ren, K., Wang, L., & Wang, G. Recyclable Merrifield resin-supported organocatalysts containing pyrrolidine unit through A3-coupling reaction linkage for asymmetric Michael addition. Chirality 2010, 22, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boruah, J.J. , Das, S. P., Ankireddy, S.R., Gogoi, S.R., & Islam, N.S. Merrifield resin supported peroxomolybdenum (VI) compounds: recoverable heterogeneous catalysts for the efficient, selective and mild oxidation of organic sulfides with H 2 O 2. Green chemistry 2013, 15, 2944–2959. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G. (2007). Surface modification with polymers using living radical polymerisation and click chemistry (Doctoral dissertation, University of Warwick).

- Kachhap, P. , & Haldar, C. Catalytic Oxidation of Aliphatic Alcohols by Hydrogen Peroxide Using Merrifield Resin-Supported Binuclear Dioxidovanadium(v) Complexes of Hydrazone Ligands as a Catalyst. Topics in Catalysis 2024, 1-21. [CrossRef]

- Pisk, J. , Agustin, D. , & Poli, R. Organic salts and Merrifield resin supported [PM12O40] 3−(M= Mo or W) as catalysts for adipic acid synthesis. Molecules, 2019, 24, 783. [Google Scholar]

- Boruah, J.J. , & Das, S. P. Solventless, selective and catalytic oxidation of primary, secondary and benzylic alcohols by a Merrifield resin supported molybdenum(VI) complex with H2O2 as an oxidant. RSC advances 2018, 8, 34491–34504. [Google Scholar]

- Maurya, M.R. , Chaudhary, N., & Avecilla, F. (2014). Polymer-grafted and neat vanadium(V) complexes as functional mimics of haloperoxidases. Polyhedron, 67, 436–448. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y. (2013). Novel applications of surface-modified sporopollenin exine capsules (Doctoral dissertation, University of Hull).

- Edo, G.I. , Ndudi, W., Ali, A.B., Yousif, E., Zainulabdeen, K., Onyibe, P.N., Ekokotu, H, A., Isoje, E.F.,Essaghah, A.E., Agmed, D.S., Umar, D.,& Ozsahin, D.U. (2024). Poly(vinyl chloride) (PVC): an updated review of its properties, polymerization, modification, recycling, and applications. Journal of Materials Science, 1-44. [CrossRef]

- Rajesh Krishnan, G. , & Sreekumar, K. (2008). Catalysis by Polymer Supported Dendrimers, their Metal Complexes and Nanoparticle Conjugates (Doctoral dissertation, Cochin University of Science and Technology).

- Dalla Valle, C. (2017). Novel mesoporous polymers and their application in heterogeneous catalysis (Doctoral thesis University of padua).

- Lamblin, M. , Nassar-Hardy, L. , Hierso, J.C., Fouquet, E., & Felpin, F.X. Recyclable heterogeneous palladium catalysts in pure water: Sustainable developments in Suzuki, Heck, Sonogashira and Tsuji–Trost reactions. Advanced Synthesis & Catalysis, 2010, 352, 33–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbey, R. , Lavanant, L. , Paripovic, D., Schuwer, N., Sugnaux, C., Tugulu, S., & Klok, H.A. Polymer brushes via surface-initiated controlled radical polymerization: synthesis, characterization, properties, and applications. Chemical Reviews, 2009, 109, 5437–5527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biernat, J.F. Konieczka, P.; Tarbet, B.J.; Bradshaw, J.S.; Izatt, R.M. Complexing and Chelating Agents Immobilized on Silica Gel and Related Materials and Their Application for Sorption of Inorganic Species. Sep. Purif. Methods 1994, 23, 77–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapinte, V. , Montembault, V., Houdayer, A., & Fontaine, L. Surface initiated ring-opening metathesis polymerization of norbornene onto Wang and Merrifield resins. Journal of Molecular Catalysis A: Chemical 2007, 276(1-2), 219-225. [CrossRef]

- Kappert, E.J. , Raaijmakers, M. J., Tempelman, K., Cuperus, F.P., Ogieglo, W., & Benes, N.E. Swelling of 9 polymers commonly employed for solvent-resistant nanofiltration membranes: A comprehensive dataset. Journal of Membrane Science 2019, 569, 177–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D. , Sivaramakrishna, A. , Brahmmananda Rao, C.V. S., Sivaraman, N., & Vijayakrishna, K. Phosphoramidate-functionalized Merrifield resin: synthesis and application in actinide separation. Polymer International 2018, 67, 374–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyhan, S. , Çolak, M. , Merdivan, M., & Demirel, N. Solid phase extractive preconcentration of trace metals using p-tert-butylcalix [4] arene-1, 2-crown-4-anchored chloromethylated polymeric resin beads. Analytica Chimica Acta 2007, 584, 462–468. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M.S. , Hossain, M. S., Ahmed, S., & Mobarak, M.B. Characterization and adsorption performance of nano-hydroxyapatite synthesized from Conus litteratus waste seashells for Congo red dye removal. RSC Advances 2024, 14, 38560–38577. [Google Scholar]

- Ogata, F. , Inoue, K. , Tominaga, H., Iwata, Y., Ueda, A., Tanaka, Y., & Kawasaki, N. Adsorption of Pt(IV) and Pd(II) from aqueous solution by calcined gibbsite (Aluminum hydroxide). e-Journal of Surface Science and Nanotechnology 2013, 11, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M. , Wang, J. , Liu, X., Pei, Y., Gao, M., Wang, W., & Yang, H. Bio-inspired adsorbent with ultra-uniform and abundance sites accelerate breaking the trade-off effect between adsorption capacity and removal efficiency. Chemical Engineering Journal 2023, 465, 142790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alias, M.F. , Obed, S. M., & Jassim, A.H. Synthesis and characterization of the heavy metals; Au(III), Pd(II), Pt(IV) Rh(III) complexes of s–propynyl 2–thiobenzimidazole. Baghdad Science Journal 2007, 4, 95–101. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, R.K. , Kumar, H. , & Kumar, A. A highly efficient and magnetically retrievable functionalized nano-adsorbent for ultrasonication assisted rapid and selective extraction of Pd2+ ions from water samples. RSC Advances 2015, 5, 43371–43380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, P. , Chochkova, M., & Karadjov, M. Adsorption of Pd(II) on N- and S-modified silica sorbents. Journal of Chemical Technology & Metallurgy 2022, 57.

- Elsayed, S.A. , Badr, H. E., di Biase, A., & El-Hendawy, A.M. Synthesis, characterization of ruthenium(II), nickel(II), palladium (II), and platinum (II) triphenylphosphine-based complexes bearing an ONS-donor chelating agent: Interaction with biomolecules, antioxidant, in vitro cytotoxic, apoptotic activity and cell cycle analysis. Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry 2021, 223, 111549. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.B. , Solanki, A. , & Kundu, S. Copper(II) and palladium(II) complexes with tridentate NSO donor Schiff base ligand: Synthesis, characterization and structures. Journal of Molecular Structure 2017, 1143, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- [45] Jiang, L. , Liu, Y. , Meng, X., Xian, M., & Xu, C. Adsorption behavior study and mechanism insights into novel isothiocyanate modified material towards Pd2+. Separation and Purification Technology 2021, 277, 119514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y. , Xu, C. , Qi, Q., Qiu, J., Li, Z., Wang, H., & Wang, J. Tailoring delicate pore environment of 2D Covalent organic frameworks for selective palladium recovery. Chemical Engineering Journal 2022, 446, 136823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheufele, F.B. , Módenes, A. N., Borba, C.E., Ribeiro, C., Espinoza-Quiñones, F.R., Bergamasco, R., & Pereira, N.C. Monolayer–multilayer adsorption phenomenological model: Kinetics, equilibrium and thermodynamics. Chemical Engineering Journal 2016, 284, 1328–1341. [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara, K. , Ramesh, A., Maki, T., Hasegawa, H., & Ueda, K. Adsorption of platinum(IV), palladium(II) and gold(III) from aqueous solutions onto l-lysine modified crosslinked chitosan resin. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2007, 146(1-2), 39-50.

- Xu, L. , Zhang, A. , Zhang, F., & Liu, J. Preparation and characterization of a novel macroporous silica-bipyridine asymmetric multidentate functional adsorbent and its application for heavy metal palladium removal. Journal of hazardous materials 2017, 337, 178–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M. , Wang, M. , Zhang, L., Fan, Y., Xu, L., Ma, Z., Wen, Z., Wang, H., & Cheng, N. Adsorption of Pd(II) ions by electrospun fibers with effective adsorption sites constructed by N, O atoms with a particular spatial configuration: mechanism and practical applications. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2023, 458, 132014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S. , Bediako, J. K., Cho, C.W., Song, M.H., Zhao, Y., Kim, J.A., Choi, J.W., & Yun, Y.S. Selective adsorption of Pd(II) over interfering metal ions (Co(II), Ni(II), Pt(IV)) from acidic aqueous phase by metal-organic frameworks. Chemical Engineering Journal 2018, 345, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uheida, A. , Iglesias, M. , Fontàs, C., Hidalgo, M., Salvadó, V., Zhang, Y., & Muhammed, M. Sorption of palladium (II), rhodium (III), and platinum (IV) on Fe3O4 nanoparticles. Journal of colloid and interface science 2006, 301, 402–408. [Google Scholar]

- Fayemi, O.E. , Ogunlaja, A. S., Antunes, E., Nyokong, T., & Tshentu, Z.R. The development of palladium (II)-Specific amine-functionalized silica-based microparticles: adsorption and column separation studies. Separation Science and Technology, 2015, 50, 1497–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moleko-Boyce, P. , Makelane, H. , Ngayeka, M.Z., & Tshentu, Z.R. Recovery of platinum group metals from leach solutions of spent catalytic converters using custom-made resins. Minerals, 2022, 12, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pd (mg.L-1) | Pt (mg.L-1) | Ir (mg.L-1) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mixture 1 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Mixture 2 | 10 | 5 | 5 |

| Mixture 3 | 5 | 10 | 10 |

| Resins | C | H | N | S | % Functionalization | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (Pristine) | 79.00 | 5.00 | 0.50 | 0.00 | N/A | |

| M-EDT | 79.00 | 6.00 | 0.70 | 0.03 | 30-40 | |

| M-BDT | 78.00 | 6.00 | 0.80 | 0.01 | 5-8 | |

| M-BITAA | 76.00 | 7.00 | 4.00 | 0.04 | 50-80 | |

| Rwrt Pt (IV) | Rwrt Ir(III) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mixture 1 | 0.81 | 3.58 |

| Mixture 2 | 2.04 | 28.92 |

| Mixture 3 | 0.32 | 1.91 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).