Submitted:

30 April 2025

Posted:

05 May 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction (Rationale, Current Status, Gaps, Objectives, Overview of the Work)

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microbial Strain Used in This Study

2.2. Culture of PGP Strain and Genomic DNA Isolation

2.3. Library Preparation and Sequencing

2.4. Genome Assembly and Annotation

2.5. Phylogenetic Relationship of SAI-25

2.6. Pan-Genome Analysis

2.7. Identification of Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs) in SAI-25 Strain

2.8. Identification of Potential Genes/Enzymes Responsible for Biosynthesis of an Insecticidal Diketopiperazine Derivative, Cyclo(Trp-Phe)

2.9. Genes/Pathways Underlying PGP Features

3. Results

3.1. Features of Genome Assembly of Streptomyces sp. SAI-25:

| GenBank accession no.: | KF770901 |

| Source of isolation: | Rice rhizosphere soil |

| Temperature tolerance: | 20–40°C |

| PGP and biocontrol traits: | Siderophore+, chitinase+, cellulase+, lipase+, protease+, |

| indole-3-acetic acid+ and hydrocyanic acid+ | |

| Entomopathogenic | Helicoverpa armigera, Spodoptera litura and Chilo partellus |

| Metabolite identified: | Cyclo(Trp-Phe), a diketopiperazine derivative with insecticidal activity on H. armigera. |

3.2. Phylogenetic Relationship and Taxonomic Positioning of SAI-25

3.3. Core Ortho-Groups and Unique Genes of SAI-25

3.4. Secondary Metabolite Potential of SAI-25

3.5. Potential Genes/Enzymes Responsible for Biosynthesis of an Insecticidal Diketopiperazine Derivative, Cyclo(Trp-Phe)

3.6. Genes/Pathway Underlying PGP Features

4. Discussion

4.1. SAI-25’s Chromosome-Level Assembly with High Completeness Will Be a Valuable Resource for Streptomyces Genome Mining

4.2. Phylogenetic Analysis Corrected the Species Name from S. griseoplanus to S. cavourensis

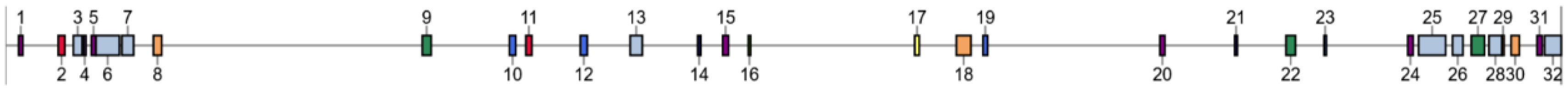

4.3. Presence of Sixteen Annotated and the Same Unannotated BGCs Highlights Its PGP and Industrial Potential

4.4. Limited Success in Prediction of Genes/BGCs for Cyclo(Trp-Phe) Biosynthesis Opens the Scope for Further Characterization

4.5. Limitations and Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 10-epi-HSAF | 10-epi-heat-stable antifungal factor |

| A-domain | Adenylation-domain |

| AMR | Antimicrobial resistance |

| BGC | Biosynthetic Gene Cluster |

| BLAST | Basic Local Alignment Search Tool |

| BlastKOALA | Automatic KO assignment and KEGG mapping service |

| bOH-Tyr | β-hydroxytyrosine |

| bp | base pairs |

| BUSCO | Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs |

| CDPs | Cyclodipeptides |

| CDPSs | Cyclodipeptide Synthases |

| CDS | Coding DNA Sequence |

| CRISPR | Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats |

| .faa | FASTA format for Amino Acid sequences |

| FTIR | Fourier Transform Infrared |

| HMMs | Hidden Markov Models |

| IAA | Indole-3-Acetic Acid |

| IAM | Indole-3-acetamide |

| InterPro | Integrative Protein Signature Database |

| iTOL | Interactive Tree Of Life |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| NCBI | National Center for Biotechnology Information |

| NRPSs | Non-Ribosomal Peptide Synthetases |

| Pfam | Protein Families And Motifs |

| PGP | Plant Growth Promotion |

| PGPB | Plant Growth Promoting Bacteria |

| Phe | Phenylalanine |

| Ph-Gly | Phenylglycine |

| RAST | Rapid Annotation using Subsystem Technology |

| Trp | Tryptophan |

| TYGS | Type (Strain) Genome Server |

| Tyr | Tyrosine |

| WGS | Whole genome Shotgun Sequencing |

References

- Subramaniam, G. Plant Growth Promoting Actinobacteria: A New Avenue for Enhancing the Productivity and Soil Fertility of Grain Legumes; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: New York, NY, 2016; ISBN 978-981-10-0705-7. [Google Scholar]

- Gopalakrishnan, S.; Sharma, R.; Srinivas, V.; Naresh, N.; Mishra, S.P.; Ankati, S.; Pratyusha, S.; Govindaraj, M.; Gonzalez, S.V.; Nervik, S.; et al. Identification and Characterization of a Streptomyces Albus Strain and Its Secondary Metabolite Organophosphate against Charcoal Rot of Sorghum. Plants 2020, 9, 1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggarwal, N.; Thind, S.K.; Sharma, S. Role of Secondary Metabolites of Actinomycetes in Crop Protection. In Plant Growth Promoting Actinobacteria; Subramaniam, G., Arumugam, S., Rajendran, V., Eds.; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2016; pp. 99–121. ISBN 978-981-10-0705-7. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya, C.; Bakshi, U.; Mallick, I.; Mukherji, S.; Bera, B.; Ghosh, A. Genome-Guided Insights into the Plant Growth Promotion Capabilities of the Physiologically Versatile Bacillus Aryabhattai Strain AB211. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayabharathi, R.; Gopalakrishnan, S.; Sathya, A.; Srinivas, V.; Sharma, M. Deciphering the Tri-Dimensional Effect of Endophytic Streptomyces Sp. on Chickpea for Plant Growth Promotion, Helper Effect with Mesorhizobium Ciceri and Host-Plant Resistance Induction against Botrytis Cinerea. Microb. Pathog. 2018, 122, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayabharathi, R.; Gopalakrishnan, S.; Sathya, A.; Vasanth Kumar, M.; Srinivas, V.; Mamta, S. Streptomyces Sp. as Plant Growth-Promoters and Host-Plant Resistance Inducers against Botrytis Cinerea in Chickpea. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2018, 28, 1140–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, S.; Srinivas, V.; Naresh, N.; Pratyusha, S.; Ankati, S.; Madhuprakash, J.; Govindaraj, M.; Sharma, R. Deciphering the Antagonistic Effect of Streptomyces Spp. and Host-Plant Resistance Induction against Charcoal Rot of Sorghum. Planta 2021, 253, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam Gopalakrishnan Biocontrol of Charcoal-Rot of Sorghum by Actinomycetes Isolated from Herbal Vermicompost. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2011, 10. [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, S.; Upadhyaya, H.; Vadlamudi, S.; Humayun, P.; Vidya, M.S.; Alekhya, G.; Singh, A.; Vijayabharathi, R.; Bhimineni, R.K.; Seema, M.; et al. Plant Growth-Promoting Traits of Biocontrol Potential Bacteria Isolated from Rice Rhizosphere. SpringerPlus 2012, 1, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gopalakrishnan, S.; Vadlamudi, S.; Apparla, S.; Bandikinda, P.; Vijayabharathi, R.; Bhimineni, R.K.; Rupela, O. Evaluation of Streptomyces Spp. for Their Plant-Growth-Promotion Traits in Rice. Can. J. Microbiol. 2013, 59, 534–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, S.; Vadlamudi, S.; Bandikinda, P.; Sathya, A.; Vijayabharathi, R.; Rupela, O.; Kudapa, H.; Katta, K.; Varshney, R.K. Evaluation of Streptomyces Strains Isolated from Herbal Vermicompost for Their Plant Growth-Promotion Traits in Rice. Microbiol. Res. 2014, 169, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, S.; Srinivas, V.; Alekhya, G.; Prakash, B.; Kudapa, H.; Rathore, A.; Varshney, R.K. The Extent of Grain Yield and Plant Growth Enhancement by Plant Growth-Promoting Broad-Spectrum Streptomyces Sp. in Chickpea. SpringerPlus 2015, 4, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, S.; Srinivas, V.; Alekhya, G.; Prakash, B. Effect of Plant Growth-Promoting Streptomyces Sp. on Growth Promotion and Grain Yield in Chickpea (Cicer Arietinum L). 3 Biotech 2015, 5, 799–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramaniam, G.; Thakur, V.; Saxena, R.K.; Vadlamudi, S.; Purohit, S.; Kumar, V.; Rathore, A.; Chitikineni, A.; Varshney, R.K. Complete Genome Sequence of Sixteen Plant Growth Promoting Streptomyces Strains. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 10294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gopalakrishnan, S.; Srinivas, V.; Chand, U.; Pratyusha, S.; Samineni, S. Streptomyces Consortia-Mediated Plant Growth-Promotion and Yield Performance in Chickpea. 3 Biotech 2022, 12, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambangi, P.; Gopalakrishnan, S. Streptomyces-Mediated Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles for Enhanced Growth, Yield, and Grain Nutrients in Chickpea. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2023, 47, 102567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathya, A.; Vijayabharathi, R.; Kumari, B.R.; Srinivas, V.; Sharma, H.C.; Sathyadevi, P.; Gopalakrishnan, S. Assessment of a Diketopiperazine, Cyclo(Trp-Phe) from Streptomyces Griseoplanus SAI-25 against Cotton Bollworm, Helicoverpa Armigera (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Appl. Entomol. Zool. 2016, 51, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivas, V.; Naresh, N.; Pratyusha, S.; Ankati, S.; Govindaraj, M.; Gopalakrishnan, S. Exploring Plant Growth-Promoting. Crop Pasture Sci. 2022, 73, 484–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayabharathi, R.; Kumari, B.R.; Sathya, A.; Srinivas, V.; Abhishek, R.; Sharma, H.C.; Gopalakrishnan, S. Biological Activity of Entomopathogenic Actinomycetes against Lepidopteran Insects (Noctuidae: Lepidoptera). Can. J. Plant Sci. 2014, 94, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayabharathi, R.; Sathya, A.; Gopalakrishnan, S. Extracellular Biosynthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Streptomyces Griseoplanus SAI-25 and Its Antifungal Activity against Macrophomina Phaseolina, the Charcoal Rot Pathogen of Sorghum. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2018, 14, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandham, P.; Vadla, N.; Saji, A.; Srinivas, V.; Ruperao, P.; Selvanayagam, S.; Saxena, R.K.; Rathore, A.; Gopalakrishnan, S.; Thakur, V. Genome Assembly, Comparative Genomics, and Identification of Genes/Pathways Underlying Plant Growth-Promoting Traits of an Actinobacterial Strain, Amycolatopsis Sp. (BCA-696). Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 15934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A Flexible Trimmer for Illumina Sequence Data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankevich, A.; Nurk, S.; Antipov, D.; Gurevich, A.A.; Dvorkin, M.; Kulikov, A.S.; Lesin, V.M.; Nikolenko, S.I.; Pham, S.; Prjibelski, A.D.; et al. SPAdes: A New Genome Assembly Algorithm and Its Applications to Single-Cell Sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 2012, 19, 455–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurevich, A.; Saveliev, V.; Vyahhi, N.; Tesler, G. QUAST: Quality Assessment Tool for Genome Assemblies. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 1072–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, R.; Liu, B.; Xie, Y.; Li, Z.; Huang, W.; Yuan, J.; He, G.; Chen, Y.; Pan, Q.; Liu, Y.; et al. SOAPdenovo2: An Empirically Improved Memory-Efficient Short-Read de Novo Assembler. Gigascience 2012, 1, 2047–217X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, E.E.; Kampanya, N.; Lu, J.; Nordberg, E.K.; Karur, H.R.; Shukla, M.; Soneja, J.; Tian, Y.; Xue, T.; Yoo, H.; et al. PATRIC: The VBI PathoSystems Resource Integration Center. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, D401–D406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, M.V.; Cosentino, S.; Lukjancenko, O.; Saputra, D.; Rasmussen, S.; Hasman, H.; Sicheritz-Pontén, T.; Aarestrup, F.M.; Ussery, D.W.; Lund, O. Benchmarking of Methods for Genomic Taxonomy. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014, 52, 1529–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosi, E.; Donati, B.; Galardini, M.; Brunetti, S.; Sagot, M.-F.; Lió, P.; Crescenzi, P.; Fani, R.; Fondi, M. M e D u S a : A Multi-Draft Based Scaffolder. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 2443–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simão, F.A.; Waterhouse, R.M.; Ioannidis, P.; Kriventseva, E.V.; Zdobnov, E.M. BUSCO: Assessing Genome Assembly and Annotation Completeness with Single-Copy Orthologs. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 3210–3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brettin, T.; Davis, J.J.; Disz, T.; Edwards, R.A.; Gerdes, S.; Olsen, G.J.; Olson, R.; Overbeek, R.; Parrello, B.; Pusch, G.D.; et al. RASTtk: A Modular and Extensible Implementation of the RAST Algorithm for Building Custom Annotation Pipelines and Annotating Batches of Genomes. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 8365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Göker, M. TYGS Is an Automated High-Throughput Platform for State-of-the-Art Genome-Based Taxonomy. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhaiyan, M.; Saravanan, V.S.; See-Too, W.-S.; Volpiano, C.G.; Sant’Anna, F.H.; Faria Da Mota, F.; Sutcliffe, I.; Sangal, V.; Passaglia, L.M.P.; Rosado, A.S. Genomic and Phylogenomic Insights into the Family Streptomycetaceae Lead to the Proposal of Six Novel Genera. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2022, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emms, D.M.; Kelly, S. OrthoFinder: Phylogenetic Orthology Inference for Comparative Genomics. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Sato, Y.; Morishima, K. BlastKOALA and GhostKOALA: KEGG Tools for Functional Characterization of Genome and Metagenome Sequences. J. Mol. Biol. 2016, 428, 726–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Sato, Y. KEGG Mapper for Inferring Cellular Functions from Protein Sequences. Protein Sci. 2020, 29, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Sato, Y.; Kawashima, M. KEGG Mapping Tools for Uncovering Hidden Features in Biological Data. Protein Sci. 2022, 31, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, M.; Andreeva, A.; Florentino, L.C.; Chuguransky, S.R.; Grego, T.; Hobbs, E.; Pinto, B.L.; Orr, A.; Paysan-Lafosse, T.; Ponamareva, I.; et al. InterPro: The Protein Sequence Classification Resource in 2025. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D444–D456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, C.; Coulouris, G.; Avagyan, V.; Ma, N.; Papadopoulos, J.; Bealer, K.; Madden, T.L. BLAST+: Architecture and Applications. BMC Bioinformatics 2009, 10, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blin, K.; Shaw, S.; Augustijn, H.E.; Reitz, Z.L.; Biermann, F.; Alanjary, M.; Fetter, A.; Terlouw, B.R.; Metcalf, W.W.; Helfrich, E.J.N.; et al. antiSMASH 7.0: New and Improved Predictions for Detection, Regulation, Chemical Structures and Visualisation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, W46–W50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistry, J.; Chuguransky, S.; Williams, L.; Qureshi, M.; Salazar, G.A.; Sonnhammer, E.L.L.; Tosatto, S.C.E.; Paladin, L.; Raj, S.; Richardson, L.J.; et al. Pfam: The Protein Families Database in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D412–D419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Choi, J.; Choi, S.-J.; Baek, K.-H. Cyclodipeptides: An Overview of Their Biosynthesis and Biological Activity. Molecules 2017, 22, 1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widodo, W.S.; Billerbeck, S. Natural and Engineered Cyclodipeptides: Biosynthesis, Chemical Diversity, and Engineering Strategies for Diversification and High-Yield Bioproduction. Eng. Microbiol. 2023, 3, 100067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, C.; García-Estrada, C.; Lorenzana, D.; Martín, J.F. NRPSsp: Non-Ribosomal Peptide Synthase Substrate Predictor. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 426–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v6: Recent Updates to the Phylogenetic Tree Display and Annotation Tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, W78–W82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patzer, S.I.; Braun, V. Gene Cluster Involved in the Biosynthesis of Griseobactin, a Catechol-Peptide Siderophore of Streptomyces Sp. ATCC 700974. J. Bacteriol. 2010, 192, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lautru, S.; Deeth, R.J.; Bailey, L.M.; Challis, G.L. Discovery of a New Peptide Natural Product by Streptomyces Coelicolor Genome Mining. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2005, 1, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellotti, D.; Remelli, M. Deferoxamine B: A Natural, Excellent and Versatile Metal Chelator. Molecules 2021, 26, 3255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbeva, P.; Avalos, M.; Ulanova, D.; Van Wezel, G.P.; Dickschat, J.S. Volatile Sensation: The Chemical Ecology of the Earthy Odorant Geosmin. Environ. Microbiol. 2023, 25, 1565–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozfidan-Konakci, C.; Yildiztugay, E.; Alp, F.N.; Kucukoduk, M.; Turkan, I. Naringenin Induces Tolerance to Salt/Osmotic Stress through the Regulation of Nitrogen Metabolism, Cellular Redox and ROS Scavenging Capacity in Bean Plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 157, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiztugay, E.; Ozfidan-Konakci, C.; Kucukoduk, M.; Turkan, I. Flavonoid Naringenin Alleviates Short-Term Osmotic and Salinity Stresses Through Regulating Photosynthetic Machinery and Chloroplastic Antioxidant Metabolism in Phaseolus Vulgaris. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.; Kim, S.H.; Bahk, S.; Vuong, U.T.; Nguyen, N.T.; Do, H.L.; Kim, S.H.; Chung, W.S. Naringenin Induces Pathogen Resistance Against Pseudomonas Syringae Through the Activation of NPR1 in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 672552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Li, L.; Wang, C.; Wang, L.; Lu, D.; Shen, D.; Wang, J.; Jiang, C.; Cheng, L.; Pan, X.; et al. Naringenin Confers Defence against Phytophthora Nicotianae through Antimicrobial Activity and Induction of Pathogen Resistance in Tobacco. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2022, 23, 1737–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orhan, F.; Parlak, K.U.; Tabay, D.; Bozarı, S. Alleviation of the Cadmium Toxicity by Application of a Microbial Derived Compound, Ectoine. Water. Air. Soil Pollut. 2023, 234, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarov, A.V.; Anan’ina, L.N.; Gorbunov, A.A.; Pyankova, A.A. Bacteria Producing Ectoine in the Rhizosphere of Plants Growing on Technogenic Saline Soil. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2022, 55, 1074–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, K.; Oinuma, K.-I.; Ikeda, G.; Hosono, K.; Ohnishi, Y.; Horinouchi, S.; Beppu, T. AmfS, an Extracellular Peptidic Morphogen in Streptomyces Griseus. J. Bacteriol. 2002, 184, 1488–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tietz, J.I.; Schwalen, C.J.; Patel, P.S.; Maxson, T.; Blair, P.M.; Tai, H.-C.; Zakai, U.I.; Mitchell, D.A. A New Genome-Mining Tool Redefines the Lasso Peptide Biosynthetic Landscape. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2017, 13, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, E.J.; Siebers, A.; Altendorf, K. Bafilomycins: A Class of Inhibitors of Membrane ATPases from Microorganisms, Animal Cells, and Plant Cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1988, 85, 7972–7976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papini, E.; Bernard, M.; Bugnoli, M.; Milia, E.; Rappuoli, R.; Montecucco, C. Cell Vacuolization Induced by Helicobacter Pylori : Inhibition by Bafilomycins A1, B1, C1 and D. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1993, 113, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Liu, Z.; Yu, D.; Li, H.; Ju, J.; Li, W. Targeted Isolation of New Polycyclic Tetramate Macrolactams from the Deepsea-Derived Streptomyces Somaliensis SCSIO ZH66. Bioorganic Chem. 2020, 101, 103954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Liu, Y.; Liu, W.-Q.; Neubauer, P.; Li, J. The Nonribosomal Peptide Valinomycin: From Discovery to Bioactivity and Biosynthesis. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettit, G.R.; Tan, R.; Melody, N.; Kielty, J.M.; Pettit, R.K.; Herald, D.L.; Tucker, B.E.; Mallavia, L.P.; Doubek, D.L.; Schmidt, J.M. Antineoplastic Agents. Part 409: Isolation and Structure of Montanastatin from a Terrestrial Actinomycete[1]1Dedicated to the Memory of Professor Sir Derek H. R. Barton (1918–1998), a Great Chemist and Friend.1. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 1999, 7, 895–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabolotneva, A.A.; Shatova, O.P.; Sadova, A.A.; Shestopalov, A.V.; Roumiantsev, S.A. An Overview of Alkylresorcinols Biological Properties and Effects. J. Nutr. Metab. 2022, 2022, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Guo, M.; Yang, J.; Chen, J.; Xie, B.; Sun, Z. Potential TSPO Ligand and Photooxidation Quencher Isorenieratene from Arctic Ocean Rhodococcus Sp. B7740. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruce, T.J.; Birkett, M.A.; Blande, J.; Hooper, A.M.; Martin, J.L.; Khambay, B.; Prosser, I.; Smart, L.E.; Wadhams, L.J. Response of Economically Important Aphids to Components of Hemizygia Petiolata Essential Oil. Pest Manag. Sci. 2005, 61, 1115–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, G.; Kim, J.; Park, C.G.; Nislow, C.; Weller, D.M.; Kwak, Y.-S. Caryolan-1-Ol, an Antifungal Volatile Produced by Streptomyces Spp., Inhibits the Endomembrane System of Fungi. Open Biol. 2017, 7, 170075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klosterman, H.J.; Lamoureux, G.L.; Parsons, J.L. Isolation, Characterization, and Synthesis of Linatine. A Vitamin B6 Antagonist from Flaxseed (Linum Usitatissimum)*. Biochemistry 1967, 6, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Mu, J.; Jiang, Y.; Fu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, H.; Yu, X.; Ye, Z. Biosynthetic Pathways and Functions of Indole-3-Acetic Acid in Microorganisms. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laville, J.; Blumer, C.; Von Schroetter, C.; Gaia, V.; Défago, G.; Keel, C.; Haas, D. Characterization of the hcnABC Gene Cluster Encoding Hydrogen Cyanide Synthase and Anaerobic Regulation by ANR in the Strictly Aerobic Biocontrol Agent Pseudomonas Fluorescens CHA0. J. Bacteriol. 1998, 180, 3187–3196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, N.; Hwang, S.; Kim, J.; Cho, S.; Palsson, B.; Cho, B.-K. Mini Review: Genome Mining Approaches for the Identification of Secondary Metabolite Biosynthetic Gene Clusters in Streptomyces. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 1548–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Liu, Z.; Huang, Y. Complete Genome Sequence of Soil Actinobacteria Streptomyces Cavourensis TJ430. J. Basic Microbiol. 2018, 58, 1083–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas Hoyos, H.A.; Santos, S.N.; Padilla, G.; Melo, I.S. Genome Sequence of Streptomyces Cavourensis 1AS2a, a Rhizobacterium Isolated from the Brazilian Cerrado Biome. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2019, 8, e00065–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaaniche, F.; Hamed, A.; Elleuch, L.; Chakchouk-Mtibaa, A.; Smaoui, S.; Karray-Rebai, I.; Koubaa, I.; Arcile, G.; Allouche, N.; Mellouli, L. Purification and Characterization of Seven Bioactive Compounds from the Newly Isolated Streptomyces Cavourensis TN638 Strain via Solid-State Fermentation. Microb. Pathog. 2020, 142, 104106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creencia, A.R.; Alcantara, E.P.; Diaz, M.G.Q.; Monsalud, R.G. Draft Genome Sequence of a Philippine Mangrove Soil Actinomycete with Insecticidal Activity Reveals Potential as a Source of Other Valuable Secondary Metabolites. 2021, 14. 14.

- Belknap, K.C.; Park, C.J.; Barth, B.M.; Andam, C.P. Genome Mining of Biosynthetic and Chemotherapeutic Gene Clusters in Streptomyces Bacteria. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, H.-Q.; Yu, S.-Y.; Song, C.-F.; Wang, N.; Hua, H.-M.; Hu, J.-C.; Wang, S.-J. Identification and Characterization of the Antifungal Substances of a Novel Streptomyces Cavourensis NA4. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 25, 353–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Yao, T.; Jiang, Y.; Li, H.; Yuan, W.; Li, W. Deciphering a Cyclodipeptide Synthase Pathway Encoding Prenylated Indole Alkaloids in Streptomyces Leeuwenhoekii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 87, e02525–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Yu, H.; Li, S.-M. Expanding Tryptophan-Containing Cyclodipeptide Synthase Spectrum by Identification of Nine Members from Streptomyces Strains. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 4435–4444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cellulose; Rodríguez Pascual, A. , Eugenio Martín, M.E., Eds.; IntechOpen: Erscheinungsort nicht ermittelbar, 2019; ISBN 9781839680564. [Google Scholar]

| Paired-end (100 bp) | Mate-pair (250 bp) | |

|---|---|---|

| Raw reads | 50,83,396 | 1,34,97,102 |

| Clean reads | 48,81,906 | 1,03,71,537 |

| Features | Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Assembly details | Contig count | 1 |

| Genome length | 7,733,723 bp | |

| No. of plasmids | 1 | |

| Total no. of non-ATCG bases | 19,290 (0.25%) | |

| Number of Ns per 100kb | 249.43 | |

| GC content | 72.12% | |

| Contig L50 | 1 | |

| Contig N50 | 7,733,723 | |

| Annotated genome | Coding density | 88.91% |

| Coding seq. count | 6,923 | |

| Coding seq. mean length | 989.9 bp | |

| tRNA gene count | 74 | |

| tRNA mean length | 76.01 | |

| rRNA gene count | 3 | |

| rRNA mean length | 1,595.33 | |

| Count of repeats | 152 | |

| Repeat mean length | 126.87 | |

| CRISPR spacer count | 81 | |

| CRISPR spacer mean length | 32.42 | |

| Proteins | Count of Hypothetical proteins | 2,363 (34.13%) |

| Count of proteins with functional assignment | 4,560 (65.86%) | |

| Count of proteins with EC number assignment | 1,207 |

| Property | Source DB | No. of genes |

|---|---|---|

| Antibiotic resistance | PATRIC | 48 |

| Drug targets | Drug Bank | 6 |

| Drug targets | TTD | 1 |

| Transporter | TCDB | 36 |

| Virulence factors | PATRIC_VF | 3 |

| AMR mechanism | Genes |

|---|---|

| Antibiotic activation enzyme | katG |

| Antibiotic inactivation enzymes | AAC(2’)-I |

| Antibiotic target in susceptible genes | Alr,Ddl, dxr, EF-G, EF-Tu, folA, Dfr, folP, gyrA, gyrB, inhA, Fabl, Iso-tRNA, kasA, MurA, rho, rpoB, rpoC, S10p, S12p |

| Antibiotic target replacement protein | FabG, HtdX |

| Efflux pump conferring antibiotic resistance | CmIV family, Otr(C) |

| Gene conferring resistance via absence | gldB |

| Protein-altering cell wall charge | GdpD, MprF, PgsA |

| Regulator modulating expression of antibiotic resistance genes | LpqB, MtrA, MtrB, OxyR |

| ID | Annotation/Function | Source | Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| fig|1472664.5.peg.3363 | Ribokinase (EC 2.7.1.15) | RAST server | Code: idu(2);D-ribose_utilization idu(2);Deoxyribose_and_Deoxynucleoside_Catabolism |

| fig|1472664.5.peg.4738 | PE-PGRS FAMILY PROTEIN | RAST server | Not provided |

| fig|1472664.5.peg.5531 | Xanthine dehydrogenase, molybdenum binding subunit (EC 1.17.1.4) | RAST server | Code: icw(2);Purine_Utilization icw(2);Xanthine_dehydrogenase_subunits |

| fig|1472664.5.peg.1814 | ligA protein [Mycobacterium pseudoshottsii JCM 15466] | NCBI BLAST followed by Reciprocal Best BLAST | Accession: GAQ32343.1 e-value: 2.36E-04 Alignment length: 461 Percentage identity: 32.936 Query coverage (fig|1472664.5.peg.1814): 81% Subject coverage (GAQ32343.1): 85% |

| Metabolites | Biosynthetic gene cluster | Functions | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geosmin | Region 5 | Regulates seed germination and acts as a chemical repellent/attractant to predators (nematodes and protists) and insects | [48] |

| Griseobactin | Region 6 | Siderophore | [45] |

| Coelichelin | Region 7 | Siderophore | [46] |

| Naringenin | Region 8 | Alleviates abiotic stress (osmotic and salinity stress) and also contributes to pathogen resistance in plants | [49,50,51,52] |

| Desferrioxamine B | Region 11 | Siderophore | [47] |

| Ectoine | Region 16 | An osmoprotectant that alleviates cadmium-induced stress in plants | [53,54] |

| AmfS | Region 17 | Whose derivative acts as an extracellular morphogen for the onset of aerial mycelium | [55] |

| Biosynthesis of type II polyketide backbone | Region 18* | It is utilised for the biosynthesis of type II polyketide products | Figure S3 |

| Keywimysin | Region 19 | A lasso peptide whose biological function remains unknown | [56] |

| Terpenoid backbone biosynthesis | Region 20* | It is utilised in sesquiterpenoids and triterpenoids biosynthesis | Figure S4 |

| D-Amino acid metabolism | Region 21* | It plays a role in the production of D-proline, which is utilised for biosynthesis of linatine (a vitamin B6 antagonist) | Figure S5 and [66] |

| Bafilomycin B1 | Region 25 | A macrolide antibiotic that inhibits vacuolar-type ATPase (V-ATPase) | [57,58] |

| 10-epi-HSAF and its analogues | Region 26 | Shows antifungal activities against plant pathogens | [59] |

| Valinomycin and Montanastatin | Region 28 | Valinomycin is a potassium ionophore which demonstrates a diverse spectrum of biological activities (antibacterial, antifungal, insecticidal, etc.), and Montanastatin is a cancer cell growth inhibitory cyclooctadepsipeptide | [60,61] |

| Alkylresorcinol | Region 30 | A polyketide which exhibits a wide range of bioactivities (antimicrobial, anti-cancer, antilipidemic, antioxidant, etc.) | [62] |

| Isorenieratene | Region 31 | A natural antioxidant and photo/UV damage inhibitor | [63] |

| Protein ID | RAST annotation | Biosynthetic gene cluster | Number of A-domains |

|---|---|---|---|

| fig|1472664.5.peg.6606 | hypothetical protein | Region 28 | 2 |

| fig|1472664.5.peg.6542 | Polyketide synthase modules and related proteins | Region 27 | 2 |

| fig|1472664.5.peg.481 | Siderophore biosynthesis non-ribosomal peptide synthetase modules | Region 7 | 3 |

| fig|1472664.5.peg.6541 | Siderophore biosynthesis non-ribosomal peptide synthetase modules | Region 27 | 2 |

| fig|1472664.5.peg.429 | Siderophore biosynthesis non-ribosomal peptide synthetase modules | Region 6 | 2 |

| fig|1472664.5.peg.5776 | Polyketide synthase modules and related proteins | Region 22 | 1 |

| fig|1472664.5.peg.2757 | Polyketide synthase modules and related proteins | Region 13 | 1 |

| fig|1472664.5.peg.6452 | Capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis fatty acid synthase WcbR | Region 26 | 1 |

| fig|1472664.5.peg.6605 | hypothetical protein | Region 28 | 2 |

| fig|1472664.5.peg.2758 | Polyketide synthase modules and related proteins | Region 13 | 1 |

| fig|1472664.5.peg.6533 | Polyketide synthase modules and related proteins | Region 27 | 1 |

| fig|1472664.5.peg.392 | Polyketide synthase modules and related proteins | Region 6 | 1 |

| fig|1472664.5.peg.6862 | Polyketide synthase modules and related proteins | Region 32 | 2 |

| fig|1472664.5.peg.2755 | Polyketide synthase modules and related proteins | Region 13 | 1 |

| fig|1472664.5.peg.5774 | hypothetical protein | Region 22 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).