Submitted:

30 April 2025

Posted:

02 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Network Traffic Forecasting

2.2. Blockchain and Federated Learning

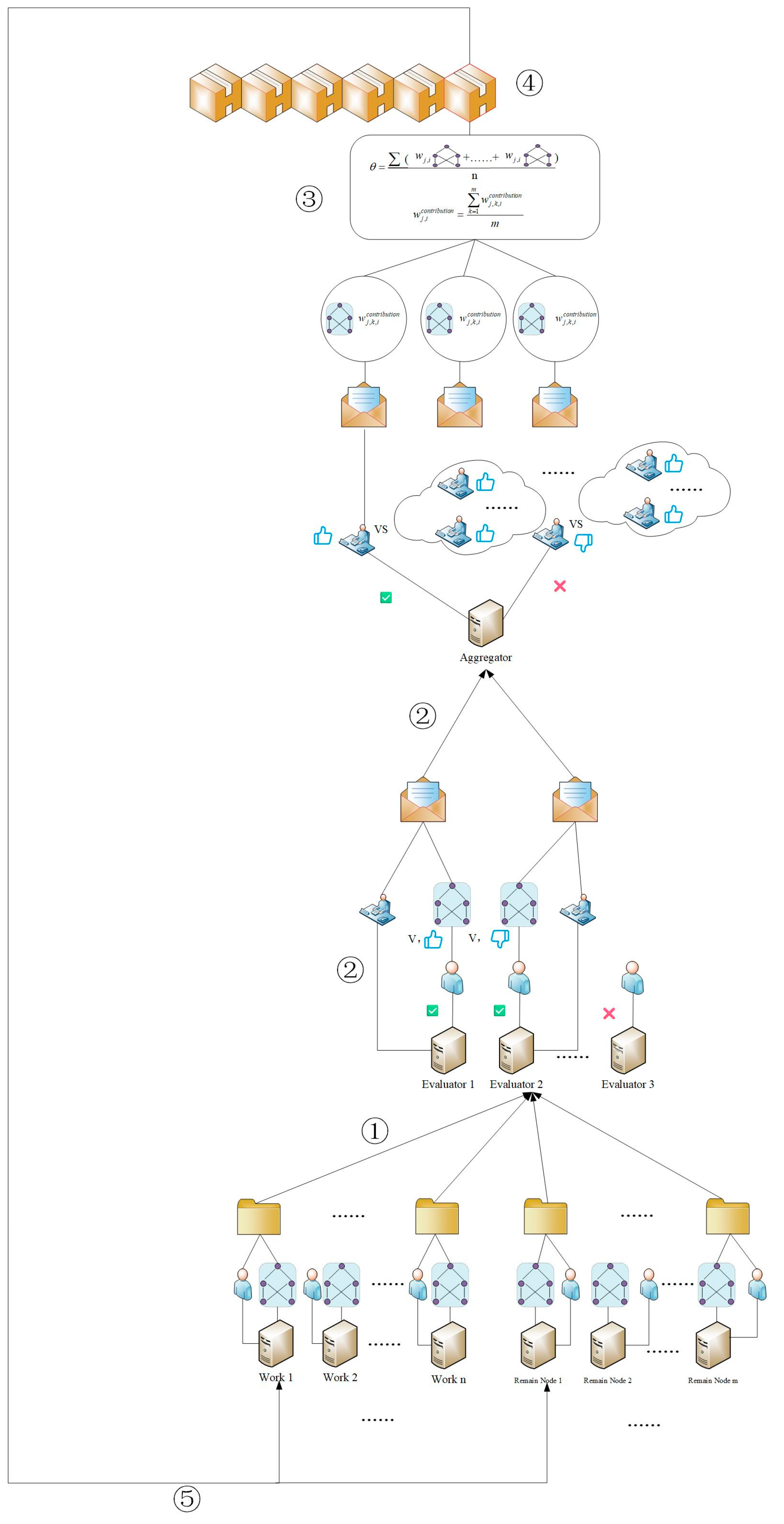

3. System Architecture

3.1. Mathematical Model of VNF Migration Problem

3.1.1. Decision Variable

3.1.2. Constraints

- Constraint (4):

- Ensure that the traffic of each SFC request cannot be split.

3.1.3. Migration Cost

3.1.4. Optimization Objectives

3.2. System Model

3.2.1. General Architecture

3.2.2. Implementation Steps

3.3. Consensus Mechanism

4. Algorithms

| Inputs: Node set , Block and Global model . |

| Output: New block , New global model . |

| 1 For each node i: |

| 2 Randomize the type to which the nodes belongs. |

| 3 End for |

| 4 For each node i: |

| 5 If node i belongs worker: |

| 6 ← 0; |

| 7 End if |

| 8 End for |

| 9 For each round out_r from 1 to EPOCH_OUT: |

| 10 For each round in_r from 1 to EPOCH_IN: |

| 11 Train each local model using local private historical traffic data; //At Worker |

| 12 Generate transactions with model parameter of each local model and authentication information, then send them to all Evaluator nodes; // At Worker |

| 13 For each model i: //At Evaluator |

| 14 If model i is worker or remain node: |

| 15 For each Evaluator : |

| 16 Verify the identity of the node; |

| 17 If identity passes: |

| 18 Evaluate the migration cost of the model i according to Eq.(25); |

| 19 Compute the gap ratio according to Eq.(28); |

| 20 If < threshold : |

| 21 Select the node and update the contribution according to Eq.(30); |

| 22 Else: |

| 23 Ignore the node and update the contribution according to Eq.(29); |

| 24 End if |

| 25 End if |

| 26 End for |

| 27 End if |

| 28 End for |

| 29 For each node k://At Aggregator |

| 30 If node k is evaluator: |

| 31 Compute evaluation for evaluator according to Eq.(31); |

| 32 If evaluation > threshold : |

| 33 Generate a transaction containing the validation results and send it to the Aggregator node. |

| 34 Else: |

| 35 Set evaluator to be the remaining node; |

| 36 Set the contribution value of the remaining node k to 0; |

| 37 If the number of evaluator nodes is less than half the maximum number of evaluator nodes. |

| 38 TRANS=1; |

| 39 Else: |

| 40 TRANS=0; |

| 41 End if |

| 42 End if |

| 43 End if |

| 44 End for |

| 45 For each Worker:// At Aggregator |

| 46 If more than half of the Evaluators select this worker. |

| 47 Select this worker as the aggregation node; |

| 48 End if |

| 49 End for |

| 50 For each worker:// At Aggregator |

| 51 Calculate the actual contribution according to Eq.(32); |

| 52 End for |

| 53 Generate global model and new block according to Eq.(26) using all of local models of the selected aggregator; |

| 54 Broadcast the new block to all Workers and the Remaining nodes. |

| 55 If TRANS==1: |

| 56 break; |

| 57 End if |

| 58 End for |

| 59 Reassign node roles according to Algorithm 2; |

| 60 End for |

| Input: Current roles of all nodes. |

| Output: Updated node roles (Aggregator, Worker, Residual, or Evaluator nodes). |

| 1 Select a node as aggregator from the Workers and Residual nodes with the highest contribution; |

| 2 Select k nodes as evaluators from the Workers and Residual nodes with higher contribution; |

| 3 for each node i: |

| 4 If the node i is the former Evaluator or Aggregator: |

| 5 set the node i as Worker; |

| 6 End if |

| 7 End for |

| 8 Select n-m-1 nodes as Workers from the Workers and Residual nodes with higher contribution; |

| 9 Set the remaining nodes as Residual nodes; |

| 10 Return the result of the updated role assignment; |

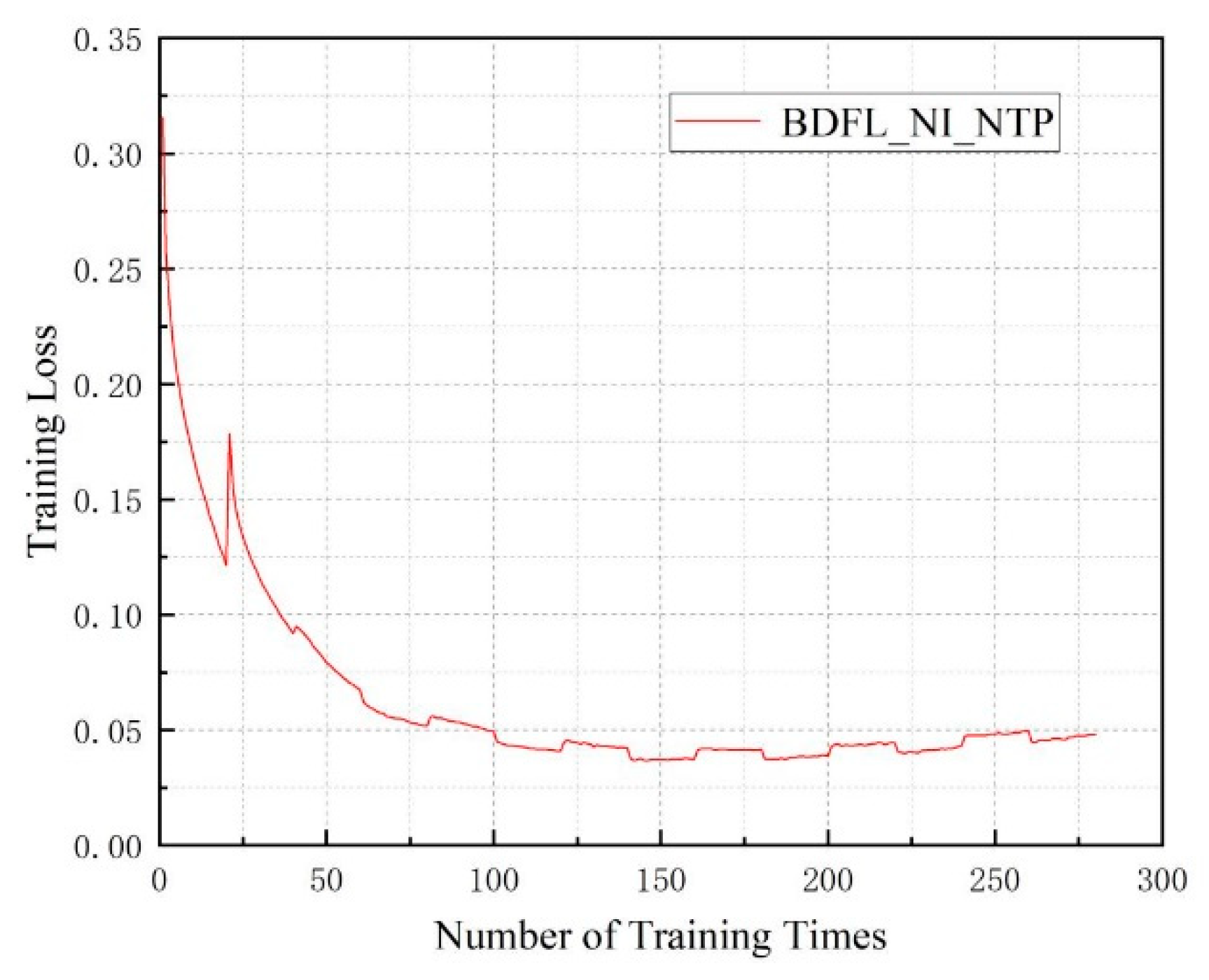

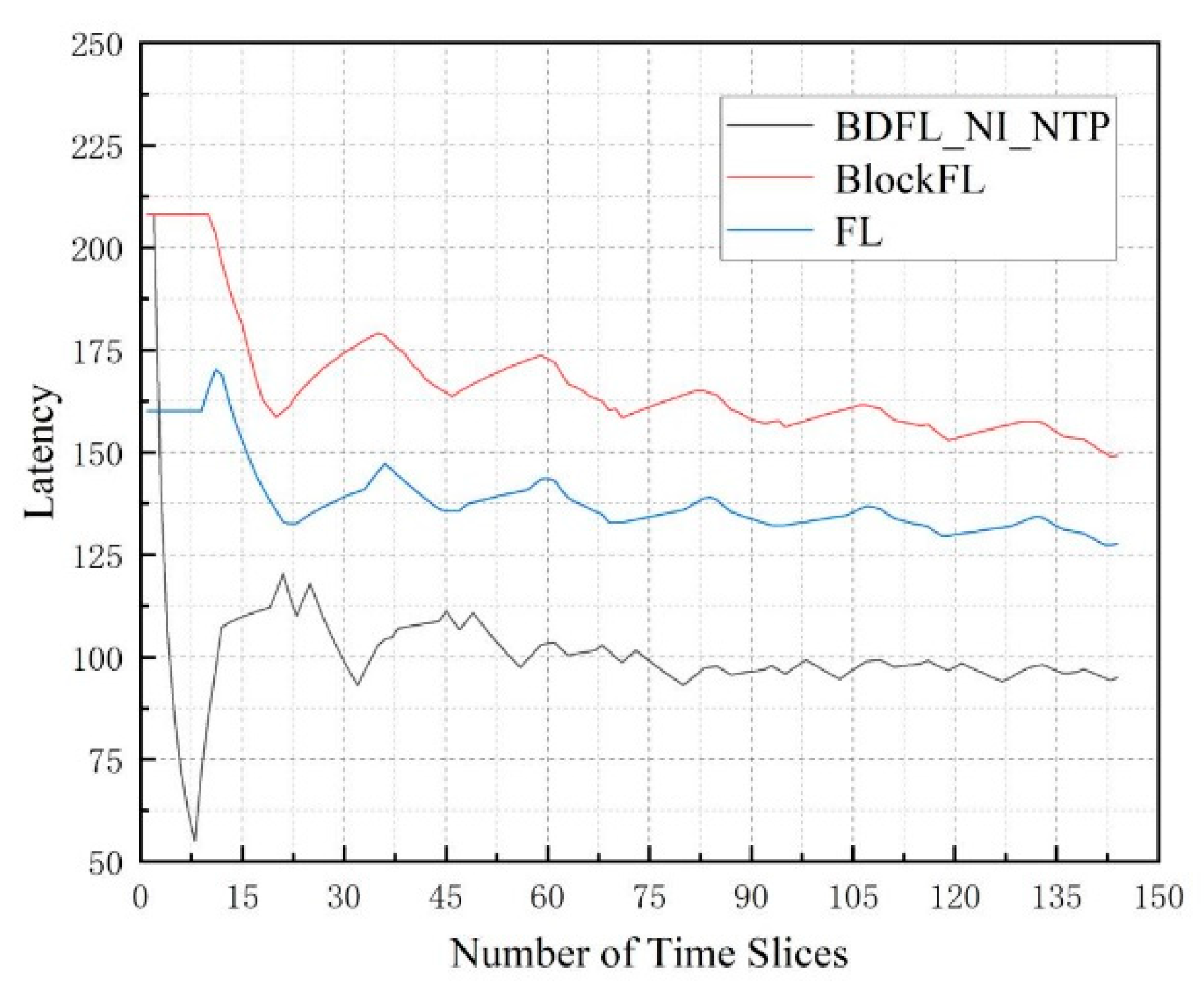

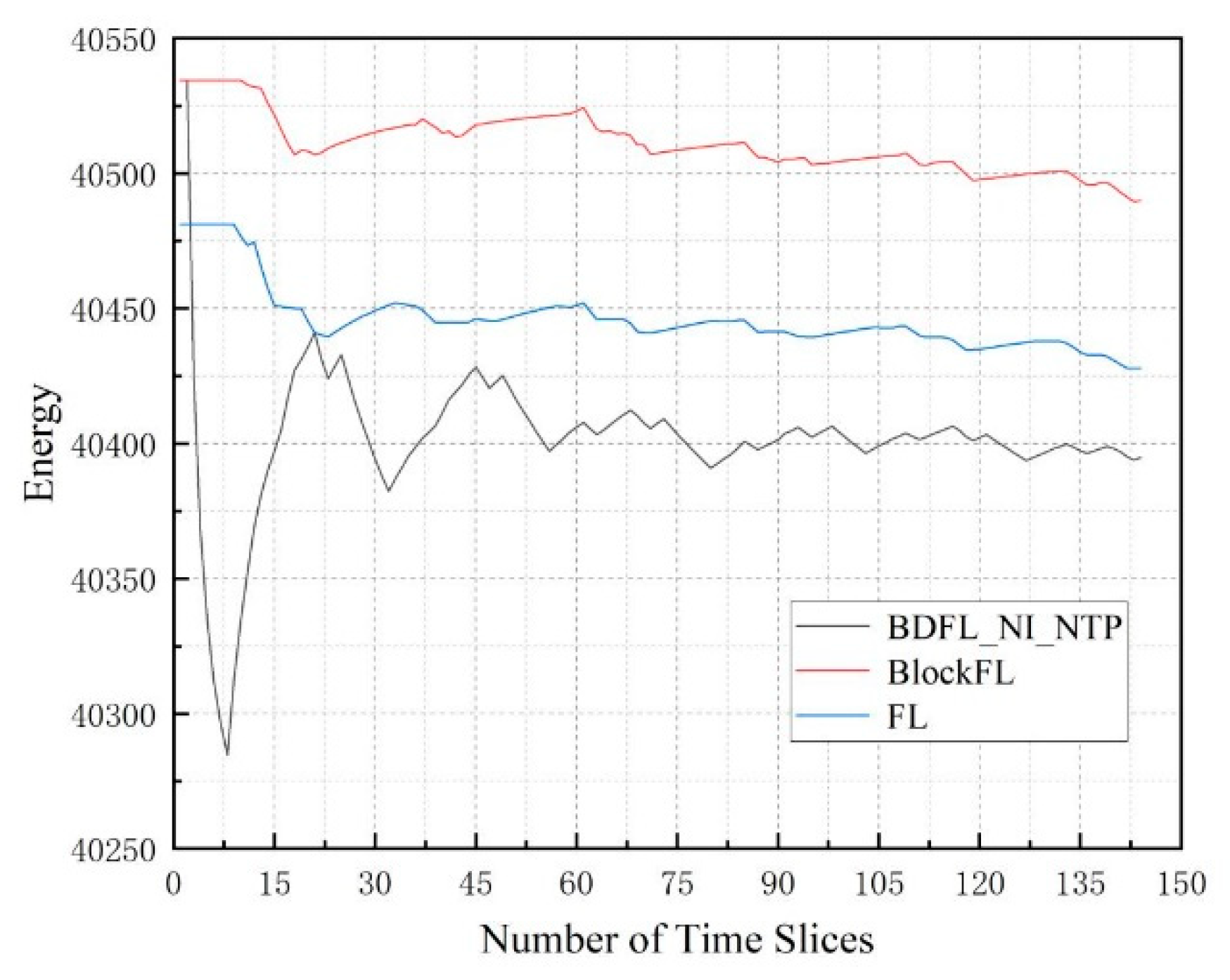

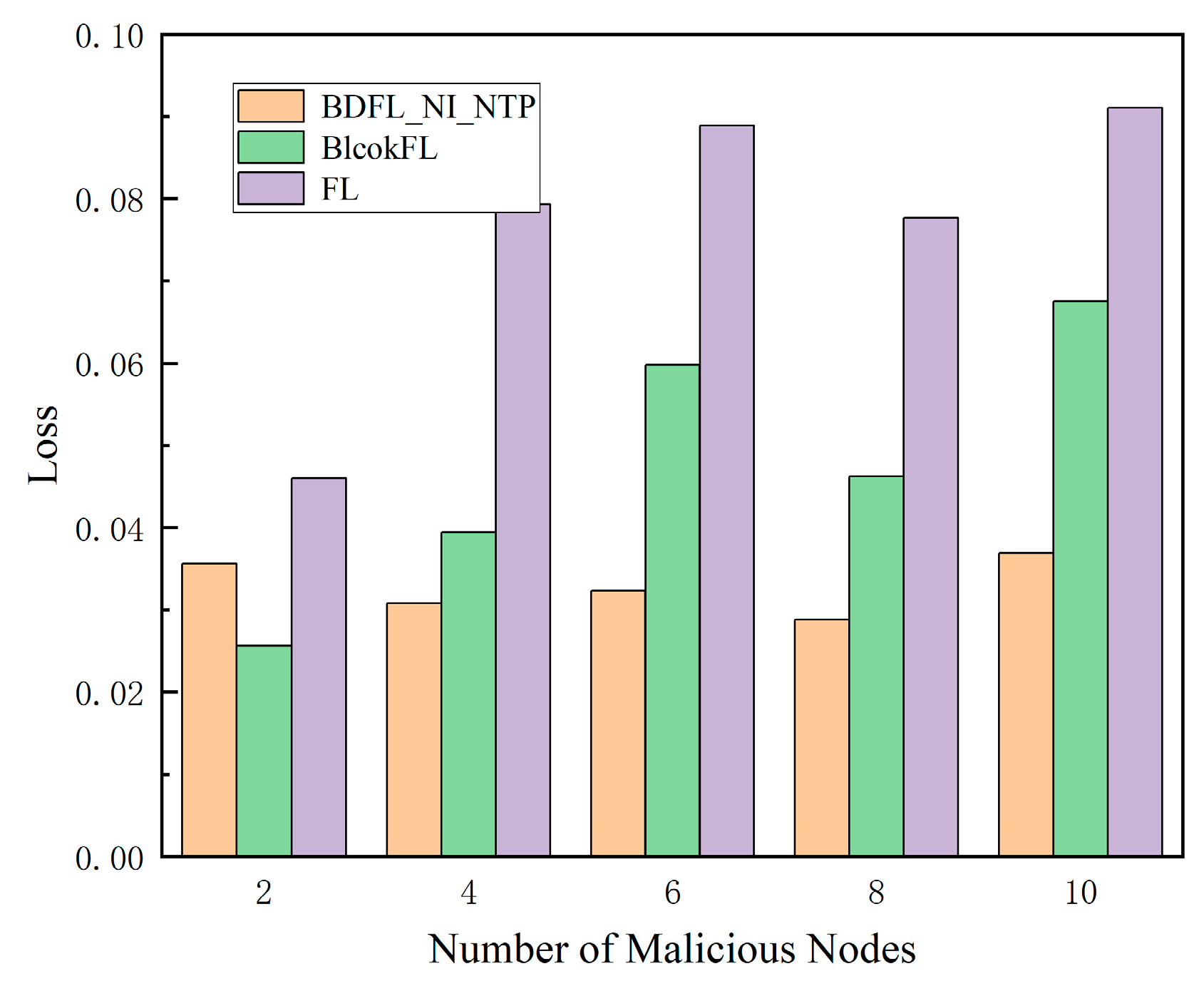

5. Simulation

5.1. Settings

5.1.1. Parameter Settings

5.1.2. Data Sources

5.1.3. Benchmark Schemes

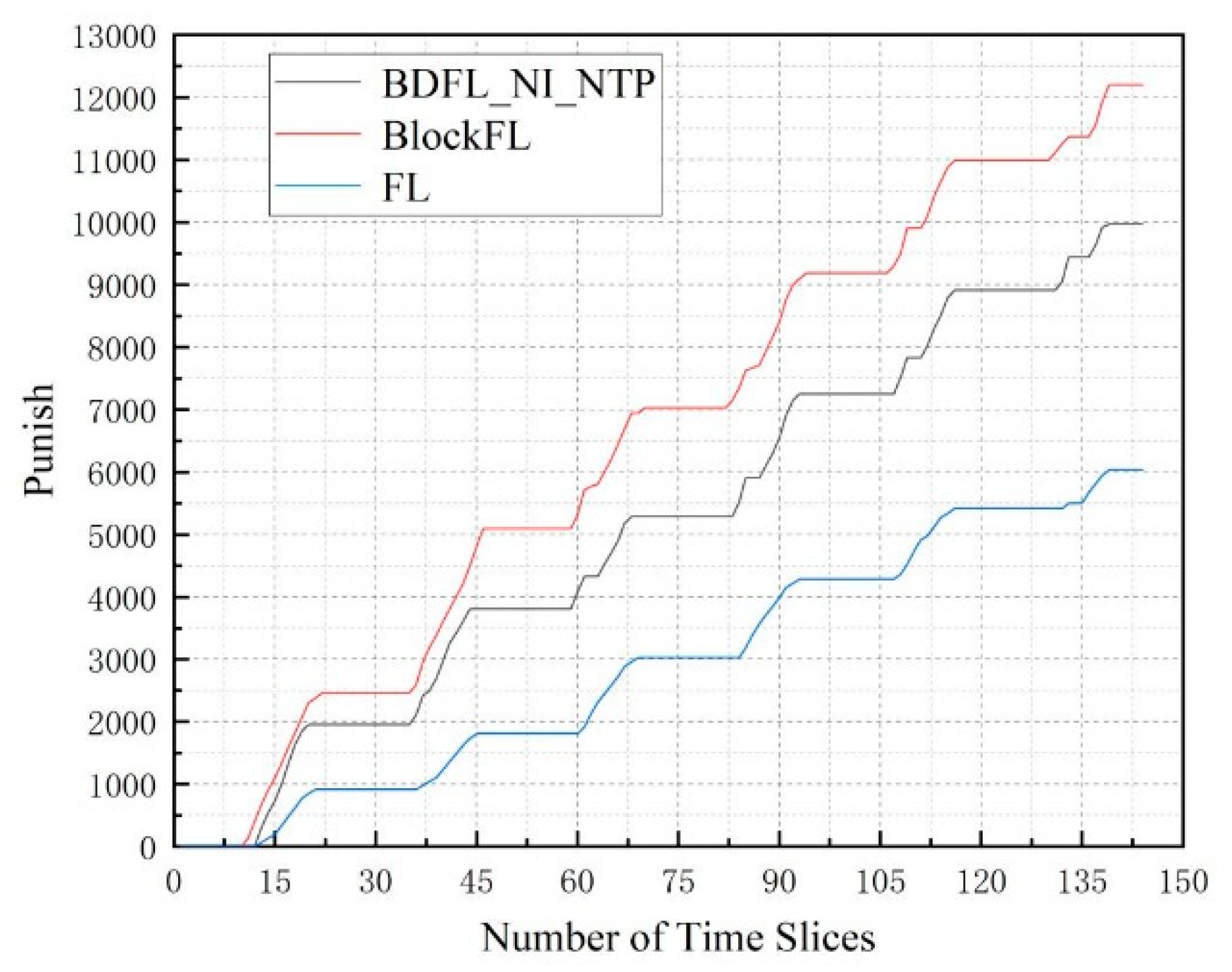

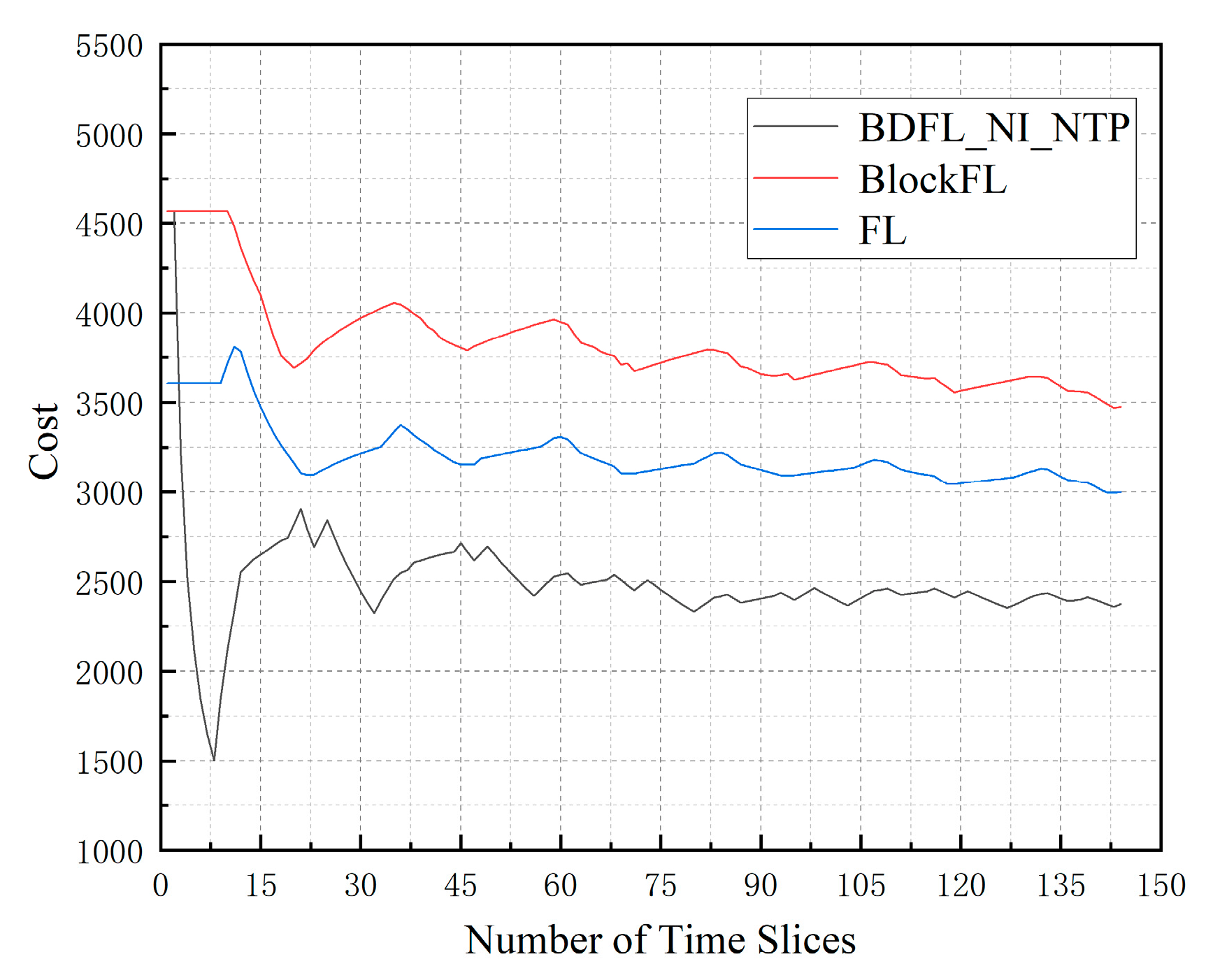

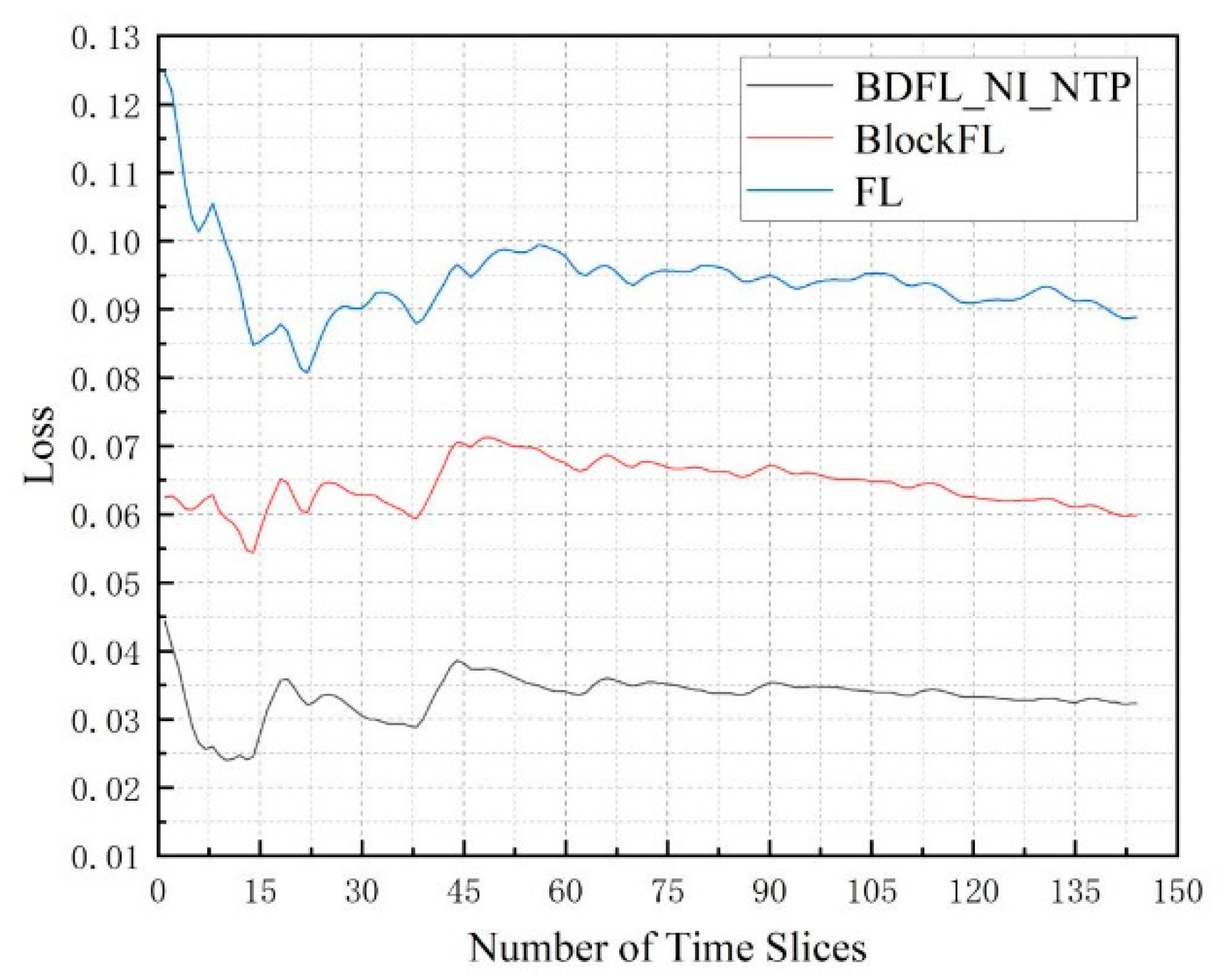

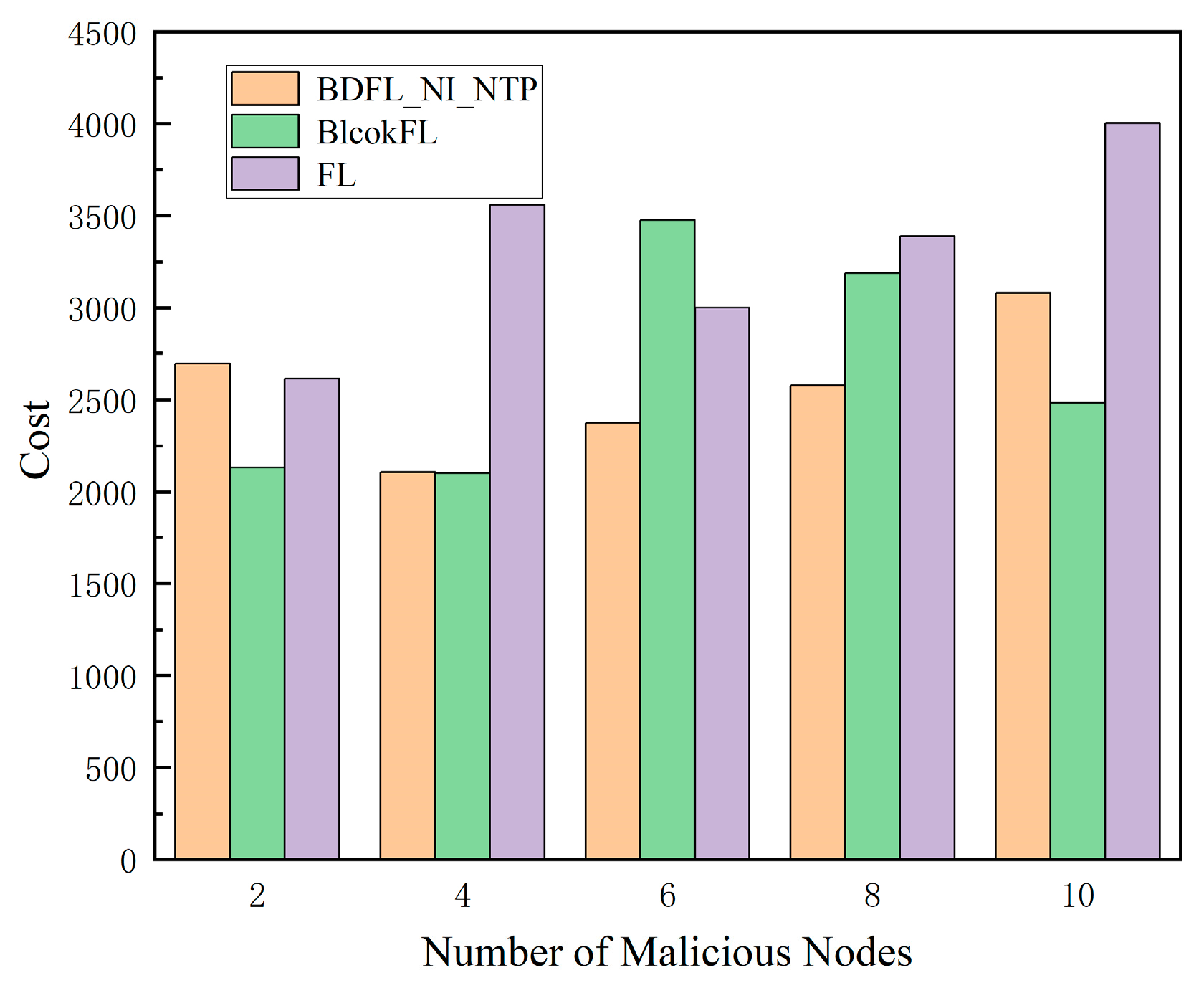

5.2. Evaluation Indicators

5.3. Performance Evaluation

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Q. Liu et al., “Deep reinforcement learning for resource demand prediction and virtual function network migration in digital twin network,” IEEE Internet Things J., vol. 10, no. 21, pp. 19102–19116, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Cai et al., “Privacy-preserving deployment mechanism for service function chains across multiple domains,” IEEE Trans. Netw. Service Manag., vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 1241–1256, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- P. Kairouz et al., “Advances and open problems in federated learning,” Found. Trends Mach. Learn., vol. 14, no. 1–2, pp. 1–210, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Z. Li et al., “Byzantine resistant secure blockchained federated learning at the edge,” IEEE Netw., vol. 35, no. 4, pp. 295–301, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Q. Li et al., “AdaFL: Adaptive client selection and dynamic contribution evaluation for efficient federated learning,” in Proc. IEEE ICASSP, Seoul, Korea, 2024, pp. 6645–6649. [CrossRef]

- Y. Hou, L. Zhao, and H. Lu, “Fuzzy neural network optimization and network traffic forecasting based on improved differential evolution,” Future Gener. Comput. Syst., vol. 81, pp. 425–432, Apr. 2018. [CrossRef]

- N. Ramakrishnan and T. Soni, “Network traffic prediction using recurrent neural networks,” in Proc. IEEE ICMLA, Orlando, FL, USA, 2018, pp. 187–193. [CrossRef]

- C.-W. Huang, C.-T. Chiang, and Q. Li, “A study of deep learning networks on mobile traffic forecasting,” in Proc. IEEE PIMRC, Montreal, QC, Canada, 2017, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- C. Pan et al., “DC-STGCN: Dual-channel based graph convolutional networks for network traffic forecasting,” Electronics, vol. 10, no. 9, p. 1014, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Huo et al., “A blockchain-based security traffic measurement approach to software defined networking,” Mobile Netw. Appl., vol. 26, pp. 586–596, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Qi et al., “Privacy-preserving blockchain-based federated learning for traffic flow prediction,” Future Gener. Comput. Syst., vol. 117, pp. 328–337, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. Guo et al., “B2SFL: A bi-level blockchained architecture for secure federated learning-based traffic prediction,” IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput., vol. 16, no. 6, pp. 4360–4374, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- V. Kurri, V. Raja, and P. Prakasam, “Cellular traffic prediction on blockchain-based mobile networks using LSTM model in 4G LTE network,” Peer-to-Peer Netw. Appl., vol. 14, pp. 1088–1105, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Feng et al., “BAFL: A blockchain-based asynchronous federated learning framework,” IEEE Trans. Comput., vol. 71, no. 5, pp. 1092–1103, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Li et al., “Blockchain assisted decentralized federated learning (BLADE-FL): Performance analysis and resource allocation,” IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst., vol. 33, no. 10, pp. 2401–2415, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. Połap, G. Srivastava, and K. Yu, “Agent architecture of an intelligent medical system based on federated learning and blockchain technology,” J. Inf. Secur. Appl., vol. 58, p. 102748, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Cui, X. Su, and Y. Zhou, “A fast blockchain-based federated learning framework with compressed communications,” IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun., vol. 40, no. 12, pp. 3358–3372, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Ren et al., “BPFL: Blockchain-based privacy-preserving federated learning against poisoning attack,” Inf. Sci., vol. 665, p. 120377, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Kasyap, A. Manna, and S. Tripathy, “An efficient blockchain assisted reputation aware decentralized federated learning framework,” IEEE Trans. Netw. Service Manag., vol. 20, no. 3, pp. 2771–2782, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Qiao et al., “LBFL: A lightweight blockchain-based federated learning framework with proof-of-contribution committee consensus,” IEEE Trans. Big Data, 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. Che et al., “A decentralized federated learning framework via committee mechanism with convergence guarantee,” IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst., vol. 33, no. 12, pp. 4783–4800, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Q. Yang, Y. Liu, T. Chen, and Y. Tong, “Federated machine learning: Concept and applications,” ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol., vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 1–19, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- H. Kim, J. Park, M. Bennis, and S.-L. Kim, “Blockchained on-device federated learning,” IEEE Commun. Lett., vol. 24, no. 6, pp. 1279–1283, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

| Hyper parameters | Values |

|---|---|

| Learning rate | 0.0001 |

| Dropout factor | 0.2 |

| The number of outer layer cycles | 10 |

| The number of inner layer cycles | 5 |

| in Eq. (18) | 20 |

| in Eq. (20) | 1 |

| in Eq. (22) | 200 |

| in Eq. (22) | 300 |

| in Eq. (23) | 0.01 |

| in Eq. (24) | 1 |

| in Eq. (24) | 1 |

| in Eq. (24) | 1 |

| in Eq. (29) | 100 |

| in Eq. (30) | 100 |

| 1 | |

| 50% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).