1. Introduction

1.1. Proteostasis and Cellular Protein Quality Control

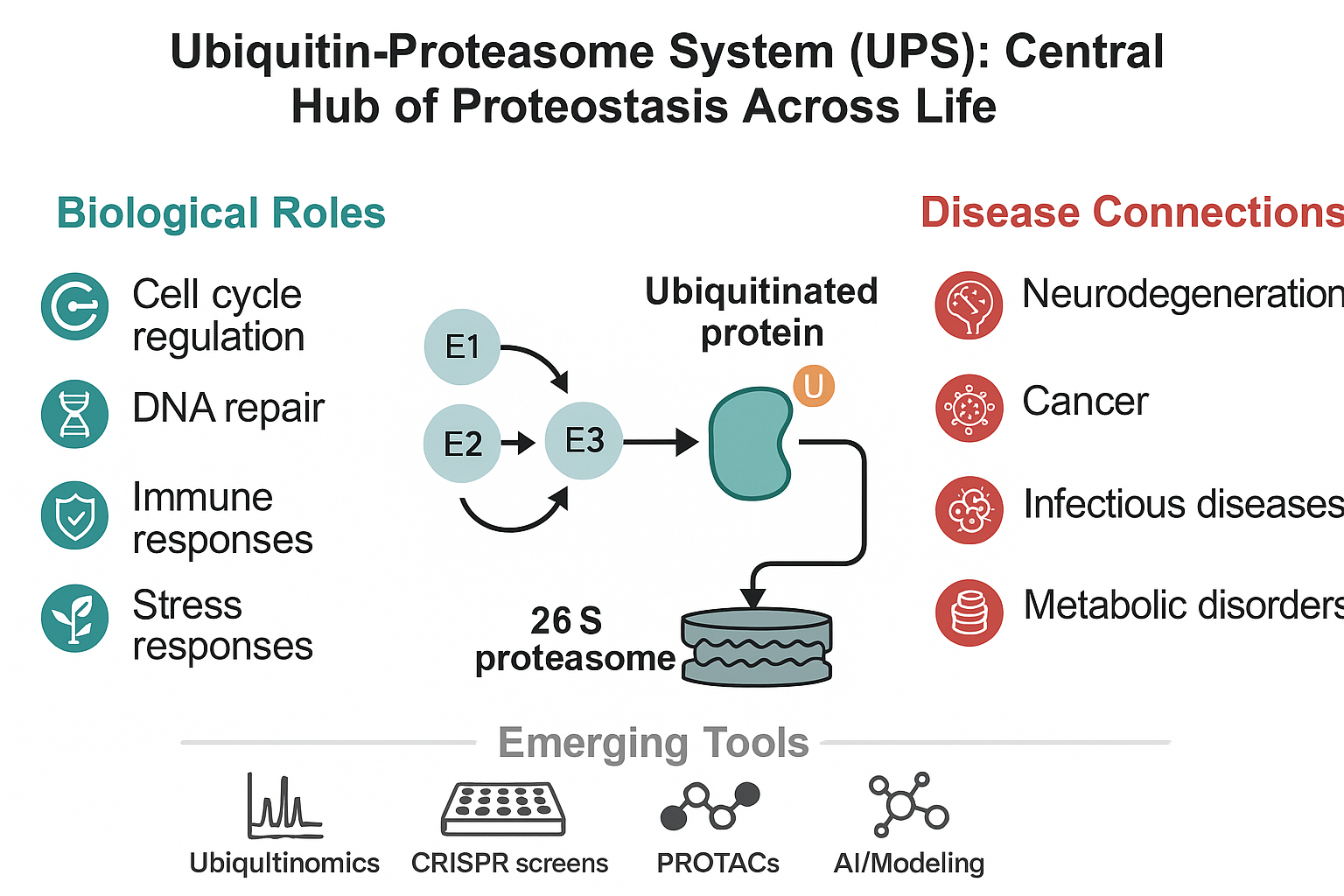

Proteostasis, or protein homeostasis, is the dynamic process by which cells maintain a functional proteome through coordinated control of protein synthesis, folding, trafficking, and degradation (Ottens et al., 2021). The balance of proteostasis is essential for cellular health and organismal survival. Disruptions in this balance, leading to the accumulation of misfolded, aggregated, or damaged proteins, are implicated in a range of pathological conditions, including neurodegenerative diseases, cancer, and metabolic disorders (Henning et al., 2017). Central to the maintenance of proteostasis is the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS), which orchestrates the selective degradation of proteins, thus regulating protein quality and quantity within the cell (Meyer-Schwesinger, 2019).

1.2. The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System: A Central Regulator of Cellular Function

The UPS represents the primary pathway for the targeted degradation of intracellular proteins (Hanna et al., 2019). This system operates through the covalent attachment of ubiquitin, a highly conserved 76-amino acid protein, to substrate proteins destined for turnover. The conjugation of ubiquitin involves a hierarchical enzymatic cascade mediated by E1 ubiquitin-activating enzymes, E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes, and E3 ubiquitin ligases, the latter of which confer substrate specificity (Voutsadakis, 2013). Polyubiquitinated proteins, particularly those modified via lysine-48 (K48) linkages, are recognized and degraded by the 26S proteasome, a multi-subunit protease complex (Shin et al., 2020). Beyond proteolysis, ubiquitination also modulates diverse aspects of protein function, including localization, complex formation, and signaling activity, thereby broadening the regulatory scope of the UPS across numerous cellular pathways (Pohl & Dikic, 2019).

1.3. Rationale for a Cross-Disciplinary Exploration

Recent advances have uncovered that the role of the UPS extends far beyond simple protein degradation. It is now recognized as a master regulator of key cellular processes such as the DNA damage response, cell cycle progression, immune signaling, and stress adaptation (Li et al., 2022). Dysregulation of UPS components contributes to the onset and progression of multiple diseases, ranging from neurodegenerative disorders and malignancies to infectious diseases and metabolic syndromes (Maiuolo et al., 2021). Moreover, the UPS plays a critical role in plant responses to environmental stress and hormonal signaling, underscoring its evolutionary conservation and functional versatility (Dreher & Callis, 2007). This review aims to provide an integrated perspective on the molecular mechanisms governing the UPS, its involvement in maintaining cellular and systemic homeostasis, and its dysregulation across various disease states. We also highlight emerging therapeutic strategies and technological advances that harness the power of the UPS. By bridging insights from different biological systems, we seek to underscore the pivotal role of the UPS in health and disease and identify future opportunities for translational research.

2. The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System: Molecular Architecture and Function

2.1. Ubiquitination: The Enzymatic Cascade (E1, E2, E3)

Ubiquitination is a highly regulated post-translational modification process that targets specific proteins for degradation or functional modulation (Lee et al., 2023). The cascade begins with the activation of ubiquitin by an E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme, which uses ATP to form a high-energy thioester bond with the ubiquitin molecule. Subsequently, the activated ubiquitin is transferred to an E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme. The final step involves an E3 ubiquitin ligase, which facilitates the covalent attachment of ubiquitin to the lysine residues of target substrate proteins (Zhang & Sidhu, 2014). Among these enzymes, E3 ligases confer substrate specificity, with the human genome encoding over 600 distinct E3 ligases to accommodate the regulation of a vast and diverse proteome (Yang et al., 2021). Depending on the cellular context, substrates can be mono-ubiquitinated or polyubiquitinated, directing them toward different fates, including proteasomal degradation, endocytosis, or signaling modulation (Wang et al., 2023).

2.2. Diversity of Ubiquitin Chains and Functional Outcomes

The versatility of ubiquitin signaling arises from its ability to form polymeric chains through any of its seven internal lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, and K63) or the N-terminal methionine (M1). The type of linkage within the polyubiquitin chain dictates distinct biological outcomes (Gonzalez-Santamarta et al., 2022). K48-linked polyubiquitin chains represent the canonical signal for proteasomal degradation, ensuring the removal of damaged, misfolded, or regulatory proteins (Çetin et al., 2021). In contrast, K63-linked chains are primarily associated with non-proteolytic functions, including DNA damage response, signal transduction, and endocytic trafficking. M1-linked (linear) chains are particularly involved in regulating immune and inflammatory responses (Çetin et al., 2021). Other atypical linkages, such as K11 and K29, have been implicated in cell cycle regulation and lysosomal degradation, respectively (Dhara & Sinai, 2016). The complexity of the “ubiquitin code” enables the UPS to orchestrate diverse cellular processes with exquisite specificity and temporal control (Foster et al., 2021).

2.3. The 26S Proteasome: Structure and Regulation

The 26S proteasome is a large, ATP-dependent proteolytic complex responsible for the degradation of polyubiquitinated proteins. It consists of a cylindrical 20S core particle (CP) and one or two 19S regulatory particles (RP) that cap the core (Marshall & Vierstra, 2019). The 19S regulatory complex recognizes ubiquitinated substrates, removes ubiquitin chains through associated deubiquitinases (DUBs), and unfolds the substrate proteins in an ATP-dependent manner. The unfolded proteins are then translocated into the proteolytic chamber of the 20S core, where they are cleaved into small peptides (Snyder & Silva, 2021). Proteasomal activity is subject to tight regulation by various post-translational modifications, allosteric modulators, and interacting proteins, allowing cells to dynamically adjust protein degradation rates in response to developmental cues, cellular stress, and environmental changes (Pennington et al., 2018). Disruption of proteasomal function has profound implications for proteostasis and is implicated in numerous pathological conditions, including neurodegenerative diseases and cancer (Kurtishi et al., 2019).

2.4. Deubiquitinases (DUBs): Resetting the System

Deubiquitinases (DUBs) constitute an essential component of the UPS, responsible for the removal of ubiquitin from substrates or from polyubiquitin chains. By reversing ubiquitination, DUBs regulate the stability, activity, and interactions of substrate proteins (Farshi et al., 2015). They also recycle ubiquitin molecules, maintaining a sufficient pool of free ubiquitin necessary for ongoing cellular processes. DUBs exhibit specificity for certain ubiquitin linkages or substrates, allowing them to selectively fine-tune signaling pathways or proteolytic processes (Mevissen et al., 2017). Dysregulation of DUB activity has been implicated in tumorigenesis, neurodegeneration, and immune dysfunction, highlighting their emerging potential as therapeutic targets in diverse diseases (Qin et al., 2024).

2.5. UPS vs Autophagy: Complementary or Redundant?

While the UPS primarily degrades short-lived and soluble proteins, autophagy is responsible for the bulk degradation of long-lived proteins, protein aggregates, and damaged organelles (Fleming et al., 2022). Although mechanistically distinct, the UPS and autophagy are functionally interconnected, with significant crosstalk ensuring the maintenance of proteostasis under basal and stress conditions (Li et al., 2022). When proteasomal capacity is compromised, autophagy can be upregulated to alleviate the proteotoxic burden. Conversely, defects in autophagy can increase the reliance on proteasomal degradation (Chua et al., 2022). Molecular regulators such as p62/SQSTM1 mediate interactions between ubiquitinated proteins and the autophagic machinery, further bridging the two systems (Kumar et al., 2022). Understanding the balance between UPS and autophagy is crucial for elucidating cellular responses to stress and offers potential therapeutic avenues for diseases characterized by proteostasis impairment (Panwar et al., 2024).

3. The UPS in Cellular and Systemic Homeostasis

3.1. Regulation of the Cell Cycle and DNA Damage Response

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) is indispensable for the regulation of the cell cycle, ensuring precise control over the abundance and activity of key cell cycle regulators (Dang et al., 2017). Timely degradation of cyclins, cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors, and checkpoint proteins is orchestrated through the activity of E3 ligase complexes such as the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C) and the SCF (Skp1-Cullin-F-box) complexes (Koliopoulos et al., 2022). For instance, APC/C-mediated ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation of mitotic cyclins is crucial for the progression through and exit from mitosis (Greil et al., 2022). Aberrant UPS function in this context leads to cell cycle arrest or uncontrolled proliferation, both of which have profound pathological consequences, including tumorigenesis (Fhu and Ali., 2021). Similarly, the UPS plays a central role in the DNA damage response by modulating the stability of proteins involved in DNA repair pathways (Molinaro et al., 2021). A prominent example is the regulation of the tumor suppressor p53, whose levels are tightly controlled by the E3 ligase MDM2 under homeostatic conditions. In response to genotoxic stress, inhibition of MDM2-mediated ubiquitination leads to p53 stabilization, allowing it to activate target genes involved in cell cycle arrest, DNA repair, and apoptosis (Nagpal and Yuan, 2021). Thus, the UPS acts as a dynamic and sensitive regulator of genome integrity and cell fate decisions (Song et al., 2021).

3.2. Adaptation to Proteotoxic Stress

Cells are continually exposed to proteotoxic stresses, including oxidative stress, heat shock, and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, which threaten the stability of the proteome (Lang et al., 2021). The UPS plays a frontline role in mitigating these threats by selectively degrading misfolded, oxidized, or otherwise damaged proteins before they can aggregate and impair cellular function (Koszla and Solek, 2024). During ER stress, the unfolded protein response (UPR) is activated to restore homeostasis, with the ER-associated degradation (ERAD) pathway relying heavily on the UPS for the removal of aberrant proteins from the ER lumen (Ajoolabady et al., 2022). Likewise, oxidative stress leads to modifications in protein structure that are rapidly recognized and targeted for degradation via ubiquitin tagging (Synder et al., 2021). Failure to maintain efficient UPS activity under stress conditions results in the accumulation of toxic protein aggregates, a hallmark of many neurodegenerative diseases and other proteopathies (Chopra et al., 2022). By constantly adapting to proteotoxic insults, the UPS serves as a crucial component of the cellular stress response machinery.

3.3. Regulation of Cellular Signaling and Transcriptional Programs

The UPS extends its influence beyond proteostasis by intricately regulating key signaling pathways and transcriptional networks (Ulfig and Jakob, 2024). In the canonical NF-κB signaling pathway, the degradation of the inhibitory protein IκBα by the UPS is essential for the activation and nuclear translocation of NF-κB, a master regulator of inflammation and immune responses (Collins et al., 2016). Similarly, components of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway are tightly controlled by ubiquitination, with β-catenin degradation by the SCF^βTrCP complex preventing aberrant activation of proliferative signals (Yu et al., 2021). Transcription factors such as c-Myc, STATs, and HIF-1α are also subject to UPS-mediated degradation, which determines their stability and transcriptional output in response to diverse stimuli (Lee et al., 2023). Moreover, recent research has revealed that ubiquitination of chromatin regulators and histone-modifying enzymes adds another layer of complexity to gene expression control. Through these mechanisms, the UPS ensures that signal transduction and transcriptional programs are tightly regulated in a context-dependent and temporally precise manner (Aberger and Altaba, 2014).

3.4. Contribution of Systemic Homeostasis

Beyond the cellular level, the UPS contributes fundamentally to the maintenance of organismal homeostasis (Hoppe and Cohen, 2020). In the immune system, the generation of antigenic peptides for presentation by major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-I) molecules is critically dependent on proteasomal activity (Kloetzel, 2004). The immunoproteasome, a specialized form of the proteasome induced during inflammatory responses, enhances the generation of peptides optimal for immune surveillance (Groettrup et al., 2010). In metabolic regulation, components of insulin signaling and lipid metabolism are modulated by ubiquitination, linking UPS activity directly to nutrient sensing and energy balance (Marshall, 2006). Aging is associated with a gradual decline in proteasome activity and ubiquitin recycling, leading to increased protein aggregation and cellular dysfunction (Frankowska et al., 2022). This decline is thought to underlie many aspects of age-related diseases, including neurodegeneration, sarcopenia, and metabolic disorders. Understanding how systemic signals modulate UPS function across different tissues remains a key frontier in biology, with profound implications for disease prevention and therapeutic intervention (Guo et al., 2024).

4. Disease-Specific Insights into UPS Dysregulation

4.1. Neurodegenerative Disorders

UPS Dysfunction in Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and Huntington’s Disease

Neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), and Huntington’s disease (HD) are characterized by the progressive accumulation of misfolded and aggregated proteins, a hallmark linked to impaired ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) function (Ciechanover & Kwon, 2015). In AD, the UPS fails to effectively degrade hyperphosphorylated tau proteins and amyloid-β peptides, leading to the formation of neurofibrillary tangles and amyloid plaques that disrupt neuronal communication and viability (Ajoolabady et a., 2022). Similarly, in PD, mutations in genes such as PARK2, encoding the E3 ligase parkin, compromise the clearance of damaged mitochondria and misfolded proteins, contributing to dopaminergic neuron degeneration (Madsen et al., 2021). HD, caused by expanded polyglutamine tracts in the huntingtin protein, results in protein aggregates that can physically inhibit proteasome activity, exacerbating cellular stress and promoting neurotoxicity (Hipp et al., 2014). Importantly, evidence suggests that UPS dysfunction may precede visible protein aggregation, positioning impaired proteasomal degradation as a potential initiating event in neurodegenerative pathogenesis rather than a mere downstream consequence (Papaevgeniou & Chondrogianni., 2016).

Therapeutic Strategies Targeting the UPS in Neurodegeneration

Given the central role of UPS dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases, several therapeutic strategies are under investigation. Enhancing proteasomal activity through small molecules, such as inhibitors of deubiquitinases like USP14 (e.g., IU1), can increase the degradation of misfolded proteins (Lee et al., 2010). Augmenting E3 ligase function, particularly that of parkin, has been proposed to promote mitochondrial quality control and substrate clearance (Müller-Rischart et al., 2013). Novel technologies such as proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) offer a means to artificially direct pathogenic proteins toward proteasomal degradation (Pettersson & Crews, 2019). Additionally, compounds that prevent aggregate formation or enhance disaggregation may indirectly alleviate proteasomal burden. Gene therapy approaches targeting defective UPS components represent an emerging frontier, offering potential for durable neuroprotection (Pena et al., 2020).

4.2. Cancer Biology

UPS Regulation of Oncoproteins and Tumor Suppressors

The UPS governs the stability of key regulators of cell proliferation, apoptosis, and DNA repair, making it a central player in tumorigenesis (Tu et al., 2012). Oncoproteins such as c-Myc, Cyclin D1, and Mdm2 are tightly controlled through ubiquitination-mediated degradation under normal conditions (Shi & Gu, 2012). Tumor suppressors, most notably p53, are similarly regulated, with MDM2-mediated ubiquitination ensuring low basal p53 levels. In cancer, aberrant UPS activity often promotes malignant progression (Marine et al., 2010). Overexpression of MDM2, leading to excessive p53 degradation, is observed in multiple cancer types, while impaired ubiquitination of oncoproteins allows their pathological accumulation (Chao, 2015). Depending on the cellular context, either hyperactivation or inhibition of UPS components can drive tumorigenesis, underscoring the dual roles of UPS in cancer biology (Papaioannou & Chevet., 2017).

E3 Ligases as Tumor Drivers or Suppressors

E3 ligases represent a particularly diverse and functionally critical subset of UPS components in cancer. Some E3 ligases, such as MDM2, SKP2, and HUWE1, act as oncogenes by targeting tumor suppressors for degradation, thereby promoting proliferation and survival (Kao et al., 2018). Conversely, others like FBW7 function as tumor suppressors by degrading oncoproteins such as c-Myc, Cyclin E, and Notch (Wang et al., 2012). Loss of FBW7 is frequently associated with poor prognosis and therapy resistance across various cancers (Fan et al., 2022). Recent studies have highlighted the context-dependent roles of specific E3 ligases, suggesting that their functional output may vary depending on the molecular landscape of the tumor, further complicating therapeutic targeting strategies (Zou et al., 2023).

Targeted Protein Degradation as a Novel Anti-Cancer Strategy

The advent of targeted protein degradation platforms has revolutionized cancer therapeutics. PROTACs, bifunctional molecules that recruit E3 ligases to disease-relevant proteins, enable the selective ubiquitination and degradation of previously “undruggable” targets, including transcription factors and scaffolding proteins (Samarasinghe & Crews, 2021). In parallel, molecular glues, such as lenalidomide, modulate E3 ligase-substrate specificity to induce degradation of specific oncogenic factors (Nagel et al., 2021). Clinical trials investigating PROTACs targeting androgen receptors, estrogen receptors, and anti-apoptotic proteins such as BCL-XL are ongoing, offering promising new avenues for treatment. Nonetheless, challenges remain, including achieving tissue specificity, avoiding off-target effects, and circumventing resistance mechanisms.

4.3. Infectious Diseases

Viral Manipulation of the Host UPS

Many viruses have evolved sophisticated mechanisms to hijack the host UPS for their own benefit, modulating immune responses and facilitating replication. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) encodes accessory proteins such as Vif and Vpu that recruit host E3 ligase complexes to ubiquitinate and degrade antiviral factors like APOBEC3G and tetherin (Strebel, 2007). Human papillomavirus (HPV) E6 and E7 proteins similarly exploit the UPS to degrade tumor suppressors p53 and Rb, driving oncogenesis (Tomaic, 2016). Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has also been implicated in UPS manipulation, with viral proteins such as ORF10 proposed to interact with Cullin-2 E3 ligase complexes, potentially altering host protein stability and dampening immune defenses (Zhou et al., 2024). These examples highlight the critical role of UPS modulation in viral pathogenesis.

Bacterial Subversion of Ubiquitination Pathways

Pathogenic bacteria have also developed strategies to subvert the UPS. Legionella pneumophila, for instance, injects effector proteins like the SidE family, which catalyze ubiquitination independently of the canonical E1-E2-E3 cascade, facilitating bacterial survival within host cells (Tomaskovic et al., 2022). Salmonella and Shigella species produce bacterial E3 ligase-like proteins that modulate host immune signaling pathways to evade clearance (Sharma et al., 2018). Mycobacterium tuberculosis interferes with proteasome function in macrophages, impairing antigen presentation and facilitating immune evasion (Chandra et al., 2022). These findings underscore the versatility of ubiquitin system manipulation in host-pathogen interactions.

Therapeutic Opportunities Targeting UPS-Pathogen Interactions

Understanding how pathogens manipulate the UPS has opened new therapeutic avenues. Strategies aimed at restoring host UPS function, blocking pathogen-mediated hijacking of ubiquitin machinery, or enhancing proteasomal degradation of infected cells are under active investigation (Alonso & García del Portillo, 2004). Immunoproteasome activators that enhance antigen presentation could improve pathogen clearance, while pathogen-specific UPS inhibitors might selectively disrupt microbial survival mechanisms without harming host proteostasis (Thakur et al., 2019). Advances in this field could yield novel anti-infective therapies with high specificity and reduced risk of resistance.

4.4. Immune Regulation and Inflammation

The UPS is fundamental to immune regulation, mediating antigen processing, cytokine signaling, and immune cell homeostasis (Di Conza et al., 2023). During antigen presentation, proteasomal degradation of intracellular proteins generates peptides for loading onto MHC class I molecules, a process further optimized by immunoproteasomes under inflammatory conditions (Rana et al., 2023). Cytokine signaling pathways, particularly those involving NF-κB, are tightly controlled by UPS-mediated degradation of inhibitors such as IκBα (Haberecht-Müller et al., 2021). Dysregulation of UPS components can lead to chronic inflammation or immune suppression, contributing to diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, and cancer (Wang & Maldonado, 2006). Furthermore, mutations affecting E3 ligases such as Cbl-b or impairments in DUBs have been implicated in autoimmune pathogenesis, highlighting the delicate balance maintained by UPS activity within the immune system (Parihar & Bhatt, 2021).

4.5. Metabolic Disorders and Aging

UPS dysfunction is increasingly recognized as a contributing factor to metabolic disorders and age-related diseases. In insulin signaling, the degradation of insulin receptor substrate (IRS) proteins by SOCS-mediated ubiquitination attenuates signaling and promotes insulin resistance, a hallmark of type 2 diabetes (Galic et al., 2014). Lipid metabolism is similarly regulated through UPS-mediated control of transcription factors such as SREBP and PPARγ (Gu et al., 2024). Impairments in these pathways contribute to obesity, hepatic steatosis, and metabolic syndrome. Aging is accompanied by a decline in proteasomal activity, leading to the accumulation of damaged proteins and defective organelles, particularly mitochondria (Kaushik & Cuervo, 2015). The failure of mitophagy, often initiated by UPS-mediated tagging of dysfunctional mitochondria via E3 ligases like parkin, contributes to increased oxidative stress and systemic metabolic dysfunction (Kocaturk & Gozuacik, 2018). Enhancing UPS efficiency or targeting specific degradation pathways represents a promising strategy to mitigate metabolic disease progression and promote healthy aging.

5. The UPS in Plant Biology and Agricultural Innovation

5.1. Regulation of Stress Responses and Hormone Signaling

In plants, the UPS is a fundamental regulator of responses to both abiotic and biotic stresses (Liu et al., 2024). Environmental challenges such as drought, salinity, heat, and pathogen infection induce rapid and dynamic changes in the plant proteome, necessitating tight control over protein stability (Singh et al., 2023). The UPS orchestrates these responses by selectively degrading key transcription factors, signaling intermediates, and regulatory proteins involved in stress adaptation (Uday et al., 2024). For instance, components of the drought and salinity stress pathways, including transcription factors such as DREB2A, are regulated via ubiquitination to fine-tune gene expression under adverse conditions (Chaffai et al., 2024). Hormone signaling networks in plants are also heavily dependent on the UPS for their regulation (Saha et al., 2024). In the auxin signaling pathway, perception of the hormone leads to the recruitment of AUX/IAA repressors to the SCF^TIR1 E3 ligase complex, resulting in their ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation (Cui et al., 2024). This degradation event releases the repression of auxin-responsive genes, enabling developmental processes such as cell elongation and differentiation (Phanindhar & Mishra, 2023). Similar mechanisms operate in gibberellin, jasmonate, and abscisic acid (ABA) signaling, where hormone-triggered degradation of negative regulators rapidly adjusts the physiological response. The ability of the UPS to mediate swift and reversible changes in protein abundance is thus critical for plant adaptability and survival under fluctuating environmental conditions (Kumar et al., 2024).

5.2. Opportunities for Crop Improvement Through UPS Engineering

enhancing stress tolerance, growth regulation, and resource use efficiency (Javed et al., 2022). Genetic manipulation of specific UPS components, such as E3 ligases or deubiquitinases, has demonstrated the potential to confer beneficial traits without negatively affecting overall plant fitness (Suranjika et al., 2024). For example, overexpression of E3 ligases that promote drought resistance, or the engineering of UPS pathways that enhance nutrient uptake, can improve crop performance under suboptimal agricultural conditions (Alam et al., 2022). Advances in genome-editing technologies, including CRISPR/Cas9, now allow precise targeting of UPS genes to create crops with customized responses to environmental cues (Nerkar et al., 2022). Moreover, modulating UPS-regulated hormone signaling pathways offers another avenue for trait improvement. Targeting the UPS components controlling flowering time, seed dormancy, or fruit ripening could lead to the development of varieties better suited to changing climates and agricultural demands (Banjare et al., 2023). However, given the broad and interconnected roles of the UPS in plant development, careful and context-specific interventions are necessary to avoid unintended pleiotropic effects (Cabrera-Serrano et al., 2025).

5.3. Cross-Kingdom Insights into Ubiquitination Mechanisms

The core architecture of the UPS is remarkably conserved across eukaryotic kingdoms, yet plants have evolved unique adaptations to address the challenges of a sessile lifestyle (Pożoga et al., 2022). For instance, plants possess plant-specific ubiquitin-like modifiers, such as RUB (related to ubiquitin), and specialized E3 ligases tailored for environmental sensing and response (Li, 2021). Comparative studies between plant and animal UPS systems have provided valuable insights into the evolution of stress resilience mechanisms. Furthermore, lessons from plant UPS research are increasingly informing animal and human biology (Kacprzyk et al., 2024). Mechanisms discovered in plants, such as fine-tuning protein turnover in response to redox changes or nutrient fluctuations, have parallels in mammalian systems and could inspire novel therapeutic strategies for proteostasis-related diseases. Thus, exploring the plant UPS not only advances agricultural biotechnology but also contributes to a broader understanding of ubiquitin biology and its applications across disciplines (Sinha et al., 2022).

6. Emerging Tools and Technologies to Study the UPS

6.1. Ubiquitin-omics and Mass Spectrometry

The advent of advanced mass spectrometry (MS) techniques has revolutionized the study of ubiquitination on a proteome-wide scale (Xu et al., 2024). Ubiquitinomics, the global profiling of ubiquitinated proteins, has provided unprecedented insights into the dynamics of the ubiquitin landscape in health and disease (Geddes-McAlister & Uhrig, 2025). Enrichment strategies utilizing antibodies specific to ubiquitin remnants, such as the diGly (K-ε-GG) motif, allow for the selective capture and identification of ubiquitination sites from complex biological samples (van der wal et al., 2022). Quantitative MS approaches, including tandem mass tag (TMT) labeling and label-free quantification, enable dynamic comparisons of ubiquitination patterns under different cellular conditions, treatments, or disease states (Sang et al., 2025). Recent advances have further expanded the ability to map atypical ubiquitin chain linkages and branched polyubiquitin architectures, revealing novel layers of regulation beyond the canonical K48 and K63 linkages (PT & Sahu, 2024). The integration of ubiquitinomics with other omics platforms, such as phosphoproteomics and transcriptomics, is now providing systems-level insights into how ubiquitination intersects with broader cellular networks.

6.2. CRISPR-Based Screens for Functional Dissection of the UPS

CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing technologies have opened powerful avenues for dissecting the functional components of the UPS (Haq et al., 2024). Genome-wide CRISPR knockout (CRISPR-KO) and activation (CRISPRa) screens allow systematic identification of E3 ligases, deubiquitinases, and ubiquitin-like modifiers that regulate specific cellular phenotypes. For example, CRISPR screens have uncovered novel UPS regulators of proteasomal degradation, immune responses, and drug resistance mechanisms. Pooled CRISPR libraries targeting UPS-related genes can also be used to identify synthetic lethal interactions, informing therapeutic strategies for diseases such as cancer (Tubío-Santamaría et al., 2023). Furthermore, CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) enables the partial repression of target genes without complete knockout, providing a more nuanced view of gene function and facilitating the study of essential UPS components. As CRISPR technologies continue to evolve, their application to UPS research promises to deepen our understanding of ubiquitin-mediated regulation and identify novel therapeutic targets (Ashitomi et al., 2025).

6.3. Live-Cell Imaging of Ubiquitination and Proteasomal Activity

Recent technological advances in live-cell imaging have enabled direct visualization of ubiquitination events and proteasomal degradation dynamics in real time (Berkley et al., 2025). Fluorescent ubiquitin sensors, degron-tagged reporter constructs, and Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET)-based assays allow the monitoring of protein ubiquitination and turnover within living cells (Tröster et al., 2025). These tools facilitate spatiotemporal analysis of how ubiquitination patterns change in response to cellular stress, signaling events, or therapeutic interventions. For instance, time-lapse imaging of proteasomal degradation can reveal how cells adapt their proteostasis machinery under oxidative stress or during infection (Enenkel et al., 2022). Live-cell imaging approaches are increasingly being integrated with optogenetics and super-resolution microscopy, offering unprecedented resolution and control in studying the dynamic regulation of the UPS in situ (Kalies, 2023).

6.4. Artificial Intelligence and Computational Modeling of Ubiquitination

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning approaches are rapidly transforming the field of ubiquitin biology by enabling the prediction of ubiquitination sites, degron motifs, and E3-substrate relationships (Hou et al., 2022). Deep learning models trained on ubiquitination datasets can accurately forecast degradation signals embedded within protein sequences, accelerating the identification of novel UPS targets (Ullah et al., 2024). Computational modeling of ubiquitin chain assembly, E3 ligase specificity, and proteasomal degradation kinetics is providing systems-level perspectives that complement experimental observations (Sikander et al., 2022). AI-driven analyses are also aiding drug discovery efforts by predicting the efficacy and selectivity of targeted protein degradation molecules such as PROTACs and molecular glues (An et al., 2025). As computational tools become more sophisticated, their integration with high-throughput experimental platforms will enhance the precision and scalability of UPS research (Liu et al., 2024).

7. Challenges and Future Directions

7.1. Mapping E3 Ligase Specificity at Scale

Despite significant progress in elucidating the components of the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS), a major unresolved challenge remains the comprehensive mapping of E3 ligase-substrate relationships. With over 600 E3 ligases encoded in the human genome, only a small fraction has well-characterized substrate profiles (Sun, 2022). Traditional methods such as co-immunoprecipitation and yeast two-hybrid screening are labor-intensive and often miss transient or low-affinity interactions (Tabar et al., 2022). Recent advances in proximity-labeling techniques, such as BioID and APEX tagging, combined with mass spectrometry, are beginning to uncover broader E3-substrate networks (Millar, 2023). However, distinguishing direct substrates from indirect interactors remains a critical hurdle. The development of scalable, high-throughput, and substrate-centric discovery methods is urgently needed to fully chart the UPS landscape. A complete E3-substrate interactome would greatly accelerate the identification of novel therapeutic targets and deepen our understanding of cellular regulatory circuits (Potjewyd & Axtman, 2021).

7.2. Achieving Selectivity in Therapeutic Targeting

Another major challenge in leveraging the UPS for therapeutic interventions lies in achieving precise selectivity (Dhoundiyal et al., 2024). Small molecules targeting the proteasome or broad classes of E3 ligases risk unintended effects on global proteostasis, potentially leading to toxicity and off-target consequences (kim et al., 2024). New technologies such as PROTACs and molecular glues offer improved selectivity by directing degradation toward specific disease-associated proteins. Nevertheless, optimizing the specificity, bioavailability, and tissue distribution of these molecules remains a formidable task (wang et al., 2024). The design of programmable degrons, rational E3 ligase recruitment, and tissue-specific delivery platforms represents promising strategies to enhance therapeutic precision (Békés et al., 2022). Overcoming these challenges is critical for translating targeted protein degradation strategies into safe and effective treatments.

7.3. Expanding UPS Insights to Underexplored Diseases

While UPS research has predominantly focused on cancer, neurodegeneration, and infectious diseases, its roles in other pathological contexts remain comparatively understudied (Gonçalves et al., 2024). Emerging evidence implicates UPS dysfunction in cardiovascular diseases, fibrotic disorders, and rare genetic syndromes (Biernacka et al., 2024). For instance, defects in proteasomal activity have been linked to cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure, while aberrant ubiquitination of fibrotic mediators may contribute to pathological tissue remodeling. Expanding UPS research into these areas could uncover novel mechanisms of disease progression and identify new therapeutic windows. Greater attention to the roles of the UPS in underexplored diseases will be critical for fully appreciating its systemic importance and therapeutic potential.

7.4. Opportunities in Precision Medicine and Synthetic Biology

The convergence of UPS research with precision medicine and synthetic biology offers exciting opportunities for future innovation (Yan et al., 2023). Personalized ubiquitinomics, integrating patient-specific ubiquitination profiles, could enable the identification of individualized therapeutic vulnerabilities (Su et al., 2021). Meanwhile, synthetic biology approaches are engineering programmable ubiquitin circuits, synthetic E3 ligases, and orthogonal degradation pathways to control cellular behavior with unprecedented precision (Teixeira & Fussenegger, 2024). These innovations hold promise not only for therapeutic applications but also for advancing biotechnology and regenerative medicine. As our understanding of the UPS deepens, its integration with cutting-edge technologies will likely drive the development of highly targeted, personalized interventions capable of restoring proteostasis in a wide range of diseases (Kumar, 2025).

8. Conclusions

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) serves as a central hub for maintaining cellular health by orchestrating protein turnover, regulating key signaling pathways, and safeguarding proteostasis under both normal and stress conditions. Its roles extend beyond proteolytic degradation, influencing nearly every aspect of cell biology, including immune responses, cell cycle progression, DNA repair, metabolic regulation, and adaptation to environmental challenges. Dysregulation of the UPS is increasingly recognized as a driver of a wide range of diseases, from cancer and neurodegenerative disorders to infectious and metabolic diseases, underscoring its critical importance in human health and disease. The past decade has witnessed remarkable advances in our understanding of UPS mechanisms, fueled by the development of new tools such as ubiquitinomics, CRISPR-based functional screens, live-cell imaging, and artificial intelligence-driven modeling. These technologies have not only deepened our mechanistic insights but have also opened new therapeutic avenues, particularly through the emergence of targeted protein degradation platforms like PROTACs and molecular glues. Furthermore, research on plant UPS systems offers valuable cross-kingdom perspectives and highlights the evolutionary versatility of ubiquitin-mediated regulation. Despite these advances, significant challenges remain. Comprehensive mapping of E3 ligase specificity, achieving therapeutic selectivity, and expanding our understanding of UPS roles in underexplored diseases are critical next steps. Future research integrating precision medicine, synthetic biology, and systems-level approaches holds immense promise for unlocking the full potential of the UPS as a therapeutic target. As our knowledge of the ubiquitin-proteasome system continues to expand, it is becoming increasingly clear that mastering the control of ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation will not only enable us to treat existing diseases but may also allow us to proactively maintain cellular and organismal health. Harnessing the UPS with precision offers a transformative opportunity to reshape the future of medicine, agriculture, and biotechnology.

Author Contributions

M.A.A.H., S.S., and A.A.M. comprehended and planned the study, carried out the analysis, wrote the manuscript; and prepared the graphs and illustrations; S.B.I., and M.M. contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript and wrote the manuscript; A.A.M. supervised the whole work, and all authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding

There was no fund available.

Ethics declarations

This article does not include any studies by any of the authors that used human or animal participants. All authors are conscious and accept responsibility for the manuscript. No part of the manuscript content has been published or accepted for publication elsewhere.

Code availability

There was no code available.

Data availability

The corresponding author Abdullah Al Mamun is responsible for all data and materials.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to thank the department of Biotechnology and Genetic Engineering for supporting this research

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Aberger, F.; i Altaba, A. R. Context-dependent signal integration by the GLI code: the oncogenic load, pathways, modifiers and implications for cancer therapy. In Seminars in cell & developmental biology; Academic Press, September 2014; Vol. 33, pp. 93–104. [Google Scholar]

- Ajoolabady, A.; Lindholm, D.; Ren, J.; Pratico, D. ER stress and UPR in Alzheimer’s disease: mechanisms, pathogenesis, treatments. Cell death & disease 2022, 13(8), 706. [Google Scholar]

- Ajoolabady, A.; Lindholm, D.; Ren, J.; Pratico, D. ER stress and UPR in Alzheimer’s disease: mechanisms, pathogenesis, treatments. Cell death & disease 2022, 13(8), 706. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, I.; Batool, K.; Huang, Y.; Liu, J.; Ge, L. Developing genetic engineering techniques for control of seed size and yield. International journal of molecular sciences 2022, 23(21), 13256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, A.; García del Portillo, F. Hijacking of eukaryotic functions by intracellular bacterial pathogens, 2004.

- An, Q.; Huang, L.; Wang, C.; Wang, D.; Tu, Y. New strategies to enhance the efficiency and precision of drug discovery. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2025, 16, 1550158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashitomi, H.; Nakagawa, T.; Nakagawa, M.; Hosoi, T. Cullin-RING Ubiquitin Ligases in Neurodevelopment and Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Biomedicines 2025, 13(4), 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banjare, R.; Nidhi, N.; Sood, A. Physiological Aspects of Flowering, Fruit Setting, Fruit Development and Fruit Drop, Regulation and their Manipulation: A Review. Int. J. Environ. Clim. Change 2023, 13(12), 205–224. [Google Scholar]

- Békés, M.; Langley, D. R.; Crews, C. M. PROTAC targeted protein degraders: the past is prologue. Nature reviews Drug discovery 2022, 21(3), 181–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkley, K.; Zalejski, J.; Sharma, N.; Sharma, A. Journey of PROTAC: From Bench to Clinical Trial and Beyond. Biochemistry 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biernacka, E. K.; Osadnik, T.; Bilińska, Z. T.; Krawczyński, M.; Latos-Bieleńska, A. I.; Gil, R. Genetic testing for inherited cardiovascular diseases. A position statement of the Polish Cardiac Society endorsed by Polish Society of Human Genetics and Cardiovascular Patient Communities. Polish Heart Journal (Kardiologia Polska) 2024, 82(5), 569–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Serrano, A. J.; Sánchez-Maldonado, J. M.; González-Olmedo, C.; Carretero-Fernández, M.; Díaz-Beltrán, L.; Gutiérrez-Bautista, J. F.; Sainz, J. Crosstalk Between Autophagy and Oxidative Stress in Hematological Malignancies: Mechanisms, Implications, and Therapeutic Potential. Antioxidants 2025, 14(3), 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çetin, G.; Klafack, S.; Studencka-Turski, M.; Krüger, E.; Ebstein, F. The ubiquitin–proteasome system in immune cells. Biomolecules 2021, 11(1), 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaffai, R.; Ganesan, M.; Cherif, A. Gene Expression Regulation in Plant Abiotic Stress Response. In Plant Adaptation to Abiotic Stress: From Signaling Pathways and Microbiomes to Molecular Mechanisms; Springer Nature Singapore; Singapore, 2024; pp. 275–302. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra, P.; Grigsby, S. J.; Philips, J. A. Immune evasion and provocation by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2022, 20(12), 750–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chao, C. C. K. Mechanisms of p53 degradation. Clinica Chimica Acta 2015, 438, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, G.; Shabir, S.; Yousuf, S.; Kauts, S.; Bhat, S. A.; Mir, A. H.; Singh, M. P. Proteinopathies: deciphering physiology and mechanisms to develop effective therapies for neurodegenerative diseases. Molecular neurobiology 2022, 59(12), 7513–7540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, J. P.; De Calbiac, H.; Kabashi, E.; Barmada, S. J. Autophagy and ALS: mechanistic insights and therapeutic implications. Autophagy 2022, 18(2), 254–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciechanover, A.; Kwon, Y. T. Degradation of misfolded proteins in neurodegenerative diseases: therapeutic targets and strategies. Experimental & molecular medicine 2015, 47(3), e147–e147. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, X.; Wang, J.; Li, K.; Lv, B.; Hou, B.; Ding, Z. Protein post-translational modifications in auxin signaling. Journal of Genetics and Genomics 2024, 51(3), 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang, F.; Nie, L.; Wei, W. Ubiquitin signaling in cell cycle control and tumorigenesis. Cell Death & Differentiation 2021, 28(2), 427–438. [Google Scholar]

- Dhara, A.; Sinai, A. P. A cell cycle-regulated, 2016.

- Dhoundiyal, S.; Srivastava, S.; Kumar, S.; Singh, G.; Ashique, S.; Pal, R.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F. Radiopharmaceuticals: navigating the frontier of precision medicine and therapeutic innovation. European Journal of Medical Research 2024, 29(1), 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Conza, G.; Ho, P. C.; Cubillos-Ruiz, J. R.; Huang, S. C. C. Control of immune cell function by the unfolded protein response. Nature Reviews Immunology 2023, 23(9), 546–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreher, K.; Callis, J. Ubiquitin, hormones and biotic stress in plants. Annals of botany 2007, 99(5), 787–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enenkel, C.; Kang, R. W.; Wilfling, F.; Ernst, O. P. Intracellular localization of the proteasome in response to stress conditions. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2022, 298(7), 102083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Bellon, M.; Ju, M.; Zhao, L.; Wei, M.; Fu, L.; Nicot, C. Clinical significance of FBXW7 loss of function in human cancers. Molecular cancer 2022, 21(1), 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farshi, P.; Deshmukh, R. R.; Nwankwo, J. O.; Arkwright, R. T.; Cvek, B.; Liu, J.; Dou, Q. P. Deubiquitinases (DUBs) and DUB inhibitors: a patent review. Expert opinion on therapeutic patents 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fhu, C. W.; Ali, A. Dysregulation of the ubiquitin proteasome system in human malignancies: a window for therapeutic intervention. Cancers 2021, 13(7), 1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, A.; Bourdenx, M.; Fujimaki, M.; Karabiyik, C.; Krause, G. J.; Lopez, A.; Rubinsztein, D. C. The different autophagy degradation pathways and neurodegeneration. Neuron 2022, 110(6), 935–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, B.; Attwood, M.; Gibbs-Seymour, I. Tools for decoding ubiquitin signaling in DNA repair. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology 2021, 9, 760226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankowska, N.; Lisowska, K.; Witkowski, J. M. Proteolysis dysfunction in the process of aging and age-related diseases. Frontiers in Aging 2022, 3, 927630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galic, S.; Sachithanandan, N.; Kay, T. W.; Steinberg, G. R. Suppressor of cytokine signalling (SOCS) proteins as guardians of inflammatory responses critical for regulating insulin sensitivity. Biochemical Journal 2014, 461(2), 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geddes-McAlister, J.; Uhrig, R. G. The plant proteome delivers from discovery to innovation. Trends in Plant Science 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, M.; Vale, N.; Silva, P. Neuroprotective effects of olive oil: A comprehensive review of antioxidant properties. Antioxidants 2024, 13(7), 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Santamarta, M.; Bouvier, C.; Rodriguez, M. S.; Xolalpa, W. Ubiquitin-chains dynamics and its role regulating crucial cellular processes. In Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology; Academic Press, December 2022; Vol. 132, pp. 155–170. [Google Scholar]

- Greil, C.; Engelhardt, M.; Wäsch, R. The role of the APC/C and its coactivators Cdh1 and Cdc20 in cancer development and therapy. Frontiers in Genetics 2022, 13, 941565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groettrup, M.; Kirk, C. J.; Basler, M. Proteasomes in immune cells: more than peptide producers? Nature Reviews Immunology 2010, 10(1), 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, W.; Wu, G.; Chen, G.; Meng, X.; Xie, Z.; Cai, S. Polyphenols alleviate metabolic disorders: the role of ubiquitin-proteasome system. Frontiers in Nutrition 2024, 11, 1445080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Jin, Y.; Chen, X.; Ye, X.; Shen, X.; Lin, M.; Zhang, J. NF-κB in biology and targeted therapy: new insights and translational implications. Signal transduction and targeted therapy 2024, 9(1), 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haberecht-Müller, S.; Krüger, E.; Fielitz, J. Out of control: the role of the ubiquitin proteasome system in skeletal muscle during inflammation. Biomolecules 2021, 11(9), 1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, J.; Guerra-Moreno, A.; Ang, J.; Micoogullari, Y. Protein degradation and the pathologic basis of disease. The American journal of pathology 2019, 189(1), 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, E. U.; Yousaf, A.; Sardar, M.; Irshad, A.; Basharat, Z.; Ali, A.; Arsalan, M. Uncovering Genetic Interactions: CRISPR-Mediated Gene Knockouts and Activations in Understanding Complex Diseases. Pak-Euro Journal of Medical and Life Sciences 2024, 7(Special 2), S211–S220. [Google Scholar]

- Henning, R. H.; Brundel, B. J. Proteostasis in cardiac health and disease. Nature Reviews Cardiology 2017, 14(11), 637–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hipp, M. S.; Park, S. H.; Hartl, F. U. Proteostasis impairment in protein-misfolding and-aggregation diseases. Trends in cell biology 2014, 24(9), 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, T.; Cohen, E. Organismal protein homeostasis mechanisms. Genetics 2020, 215(4), 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, C.; Li, Y.; Wang, M.; Wu, H.; Li, T. Systematic prediction of degrons and E3 ubiquitin ligase binding via deep learning. BMC biology 2022, 20(1), 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javed, T.; I, I.; Singhal, R. K.; Shabbir, R.; Shah, A. N.; Kumar, P.; Siuta, D. Recent advances in agronomic and physio-molecular approaches for improving nitrogen use efficiency in crop plants. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 13, 877544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kacprzyk, J.; Burke, R.; Armengot, L.; Coppola, M.; Tattrie, S. B.; Vahldick, H.; McCabe, P. F. Roadmap for the next decade of plant programmed cell death research. New Phytologist 2024, 242(5), 1865–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalies, S. M. K. Visualization and manipulation of repair and regeneration in biological systems using light, 2023.

- Kao, S. H.; Wu, H. T.; Wu, K. J. Ubiquitination by HUWE1 in tumorigenesis and beyond. Journal of biomedical science 2018, 25, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, S.; Cuervo, A. M. Proteostasis and aging. Nature medicine 2015, 21(12), 1406–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Byun, I.; Joh, H.; Kim, H. J.; Lee, M. J. Targeted protein degradation directly engaging lysosomes or proteasomes. In Chemical Society Reviews; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kloetzel, P. M. Generation of major histocompatibility complex class I antigens: functional interplay between proteasomes and TPPII. Nature immunology 2004, 5(7), 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocaturk, N. M.; Gozuacik, D. Crosstalk between mammalian autophagy and the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology 2018, 6, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koliopoulos, M. G.; Alfieri, C. Cell cycle regulation by complex nanomachines. The FEBS Journal 2022, 289(17), 5100–5120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koszła, O.; Sołek, P. Misfolding and aggregation in neurodegenerative diseases: Protein quality control machinery as potential therapeutic clearance pathways. Cell Communication and Signaling 2024, 22(1), 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A. V.; Mills, J.; Lapierre, L. R. Selective autophagy receptor p62/SQSTM1, a pivotal player in stress and aging. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology 2022, 10, 793328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P. Protein misfolding in nonneurological diseases. In Protein Misfolding in Neurodegenerative Diseases; Academic Press, 2025; pp. 493–523. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P.; Paul, D.; Jhajhriya, S.; Kumar, R.; Dutta, S.; Siwach, P.; Das, S. Understanding heat-shock proteins’ abundance and pivotal function under multiple abiotic stresses. Journal of Plant Biochemistry and Biotechnology 2024, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtishi, A.; Rosen, B.; Patil, K. S.; Alves, G. W.; Møller, S. G. Cellular proteostasis in neurodegeneration. Molecular neurobiology 2019, 56(5), 3676–3689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, B. J.; Guerrero, M. E.; Prince, T. L.; Okusha, Y.; Bonorino, C.; Calderwood, S. K. The functions and regulation of heat shock proteins; key orchestrators of proteostasis and the heat shock response. Archives of toxicology 2021, 95(6), 1943–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, B. H.; Lee, M. J.; Park, S.; Oh, D. C.; Elsasser, S.; Chen, P. C.; Finley, D. Enhancement of proteasome activity by a small-molecule inhibitor of USP14. Nature 2010, 467(7312), 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J. M.; Hammarén, H. M.; Savitski, M. M.; Baek, S. H. Control of protein stability by post-translational modifications. Nature Communications 2023, 14(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. M.; Hammarén, H. M.; Savitski, M. M.; Baek, S. H. Control of protein stability by post-translational modifications. Nature Communications 2023, 14(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L. Role of the metacaspase AtMC1 in stress-triggered protein aggregate formation in yeast and plants, 2021.

- Li, Y.; Li, S.; Wu, H. Ubiquitination-proteasome system (UPS) and autophagy two main protein degradation machineries in response to cell stress. Cells 2022, 11(5), 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Xi, M.; Liu, T.; Wu, X.; Ju, L.; Wang, D. The central role of transcription factors in bridging biotic and abiotic stress responses for plants’ resilience. New crops 2024, 1, 100005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liang, L.; Su, B.; Wu, D.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Fu, C. Transformative strategies in photocatalyst design: merging computational methods and deep learning. Journal of Materials Informatics 2024, 4(4), N–A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, D. A.; Schmidt, S. I.; Blaabjerg, M.; Meyer, M. Interaction between Parkin and α-synuclein in PARK2-mediated Parkinson’s disease. Cells 2021, 10(2), 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiuolo, J.; Gliozzi, M.; Musolino, V.; Carresi, C.; Scarano, F.; Nucera, S.; Mollace, V. From metabolic syndrome to neurological diseases: role of autophagy. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2021, 9, 651021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marine, J. C.; Lozano, G. Mdm2-mediated ubiquitylation: p53 and beyond. Cell Death & Differentiation 2010, 17(1), 93–102. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, R. S.; Vierstra, R. D. Dynamic regulation of the 26S proteasome: from synthesis to degradation. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences 2019, 6, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, S. Role of insulin, adipocyte hormones, and nutrient-sensing pathways in regulating fuel metabolism and energy homeostasis: a nutritional perspective of diabetes, obesity, and cancer. Science’s STKE 2006, 2006(346), re7–re7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mevissen, T. E.; Komander, D. Mechanisms of deubiquitinase specificity and regulation. Annual review of biochemistry 2017, 86(1), 159–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer-Schwesinger, C. The ubiquitin–proteasome system in kidney physiology and disease. Nature Reviews Nephrology 2019, 15(7), 393–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millar, S. R. Evaluating Stress Granule Compositional Plasticity using a Systematic Proteomics Approach. Master’s thesis, University of Toronto (Canada)), 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Molinaro, C.; Martoriati, A.; Cailliau, K. Proteins from the DNA damage response: Regulation, dysfunction, and anticancer strategies. Cancers 2021, 13(15), 3819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller-Rischart, A. K.; Pilsl, A.; Beaudette, P.; Patra, M.; Hadian, K.; Funke, M.; Winklhofer, K. F. The E3 ligase parkin maintains mitochondrial integrity by increasing linear ubiquitination of NEMO. Molecular cell 2013, 49(5), 908–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagel, Y. A.; Britschgi, A.; Ricci, A. From Degraders to Molecular Glues: New Ways of Breaking Down Disease-Associated Proteins. Successful Drug Discovery 2021, 47–85. [Google Scholar]

- Nagpal, I.; Yuan, Z. M. The basally expressed p53-mediated homeostatic function. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology 2021, 9, 775312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerkar, G.; Devarumath, S.; Purankar, M.; Kumar, A.; Valarmathi, R.; Devarumath, R.; Appunu, C. Advances in crop breeding through precision genome editing. Frontiers in Genetics 2022, 13, 880195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ottens, F.; Franz, A.; Hoppe, T. Build-UPS and break-downs: metabolism impacts on proteostasis and aging. Cell Death & Differentiation 2021, 28(2), 505–521. [Google Scholar]

- Panwar, S.; Uniyal, P.; Kukreti, N.; Hashmi, A.; Verma, S.; Arya, A.; Joshi, G. Role of autophagy and proteostasis in neurodegenerative diseases: Exploring the therapeutic interventions. Chemical Biology & Drug Design 2024, 103(4), e14515. [Google Scholar]

- Papaevgeniou, N.; Chondrogianni, N. UPS activation in the battle against aging and aggregation-related diseases: an extended review. Proteostasis: Methods and Protocols 2016, 1–70. [Google Scholar]

- Papaioannou, A.; Chevet, E. Driving cancer tumorigenesis and metastasis through UPR signaling. Coordinating organismal physiology through the unfolded protein response 2017, 159–192. [Google Scholar]

- Parihar, N.; Bhatt, L. K. Deubiquitylating enzymes: potential target in autoimmune diseases. Inflammopharmacology 2021, 29, 1683–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennington, K. L.; Chan, T. Y.; Torres, M. P.; Andersen, J. The dynamic and stress-adaptive signaling hub of 14-3-3: emerging mechanisms of regulation and context-dependent protein–protein interactions. Oncogene 2018, 37(42), 5587–5604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersson, M.; Crews, C. M. PROteolysis TArgeting Chimeras (PROTACs)—past, present and future. Drug Discovery Today: Technologies 2019, 31, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phanindhar, K.; Mishra, R. K. Auxin-inducible degron system: an efficient protein degradation tool to study protein function. Biotechniques 2023, 74(4), 186–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohl, C.; Dikic, I. Cellular quality control by the ubiquitin-proteasome system and autophagy. Science 2019, 366(6467), 818–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potjewyd, F. M.; Axtman, A. D. Exploration of aberrant E3 ligases implicated in Alzheimer’s disease and development of chemical tools to modulate their function. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience 2021, 15, 768655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pożoga, M.; Armbruster, L.; Wirtz, M. From nucleus to membrane: a subcellular map of the N-acetylation machinery in plants. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23(22), 14492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PT, B.; Sahu, I. Decoding the ubiquitin landscape by cutting-edge ubiquitinomic approaches. Biochemical Society Transactions 2024, 52(2), 627–637. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, B.; Chen, X.; Wang, F.; Wang, Y. DUBs in Alzheimer’s disease: mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Cell Death Discovery 2024, 10(1), 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rana, P. S.; Ignatz-Hoover, J. J.; Driscoll, J. J. Targeting proteasomes and the MHC class I antigen presentation machinery to treat cancer, infections and age-related diseases. Cancers 2023, 15(23), 5632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, B.; Nayak, J.; Srivastava, R.; Samal, S.; Kumar, D.; Chanwala, J.; Giri, M. K. Unraveling the involvement of WRKY TFs in regulating plant disease defense signaling. Planta 2024, 259(1), 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samarasinghe, K. T.; Crews, C. M. Targeted protein degradation: A promise for undruggable proteins. Cell chemical biology 2021, 28(7), 934–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sang, T.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, G.; Wang, P. Navigating the landscape of plant proteomics. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Verma, S.; Seranova, E.; Sarkar, S.; Kumar, D. Selective autophagy and xenophagy in infection and disease. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology 2018, 6, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, M. Y.; Goldberg, A. L. Cellular defenses against unfolded proteins: a cell biologist thinks about neurodegenerative diseases. Neuron 2001, 29(1), 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.; Gu, W. Dual roles of MDM2 in the regulation of p53: ubiquitination dependent and ubiquitination independent mechanisms of MDM2 repression of p53 activity. Genes & cancer 2012, 3(3-4), 240–248. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, J. Y.; Muniyappan, S.; Tran, N. N.; Park, H.; Lee, S. B.; Lee, B. H. Deubiquitination reactions on the proteasome for proteasome versatility. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21(15), 5312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikander, R.; Arif, M.; Ghulam, A.; Worachartcheewan, A.; Thafar, M. A.; Habib, S. Identification of the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway domain by hyperparameter optimization based on a 2D convolutional neural network. Frontiers in Genetics 2022, 13, 851688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, B. K.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Egidi, E.; Guirado, E.; Leach, J. E.; Liu, H.; Trivedi, P. Climate change impacts on plant pathogens, food security and paths forward. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2023, 21(10), 640–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, R.; Bala, M.; Ranjan, A.; Lal, S. K.; Sharma, T. R.; Pattanayak, A.; Singh, A. K. Proteomic approaches to understand plant response to abiotic stresses. In Agricultural biotechnology: Latest research and trends; Springer Nature Singapore; Singapore, 2022; pp. 351–383. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, N. A.; Silva, G. M. Deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs): Regulation, homeostasis, and oxidative stress response. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2021, 297(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, N. A.; Silva, G. M. Deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs): Regulation, homeostasis, and oxidative stress response. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2021, 297(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Gao, J.; Feng, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M. Mitochondrial quality control in the maintenance of cardiovascular homeostasis: The roles and interregulation of UPS, mitochondrial dynamics and mitophagy. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity 2021, 2021(1), 3960773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strebel, K. HIV accessory genes Vif and Vpu. Advances in pharmacology 2007, 55, 199–232. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Su, M.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, L.; Han, C.; Huang, C.; Nice, E. C. Proteomics, personalized medicine and cancer. Cancers 2021, 13(11), 2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R. Post-Translational Regulation of 4-1BB, an Emerging Target for Cancer Immunotherapy. Doctoral dissertation, Purdue University, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Suranjika, S.; Barla, P.; Sharma, N.; Dey, N. A review on ubiquitin ligases: Orchestrators of plant resilience in adversity. Plant Science 2024, 112180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabar, M. S.; Parsania, C.; Chen, H.; Su, X. D.; Bailey, C. G.; Rasko, J. E. Illuminating the dark protein-protein interactome. Cell reports methods 2022, 2(8). [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, A. P.; Fussenegger, M. Synthetic Gene Circuits for Regulation of Next-Generation Cell-Based Therapeutics. Advanced Science 2024, 11(8), 2309088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, A. P.; Fussenegger, M. Synthetic Gene Circuits for Regulation of Next-Generation Cell-Based Therapeutics. Advanced Science 2024, 11(8), 2309088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakur, A.; Mikkelsen, H.; Jungersen, G. Intracellular pathogens: host immunity and microbial persistence strategies. Journal of immunology research 2019, 2019(1), 1356540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaić, V. Functional roles of E6 and E7 oncoproteins in HPV-induced malignancies at diverse anatomical sites. Cancers 2016, 8(10), 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaskovic, I.; Gonzalez, A.; Dikic, I. Ubiquitin and Legionella: From bench to bedside. In Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology; Academic Press, December 2022; Vol. 132, pp. 230–241. [Google Scholar]

- Tracz, M.; Bialek, W. Beyond K48 and K63: non-canonical protein ubiquitination. Cellular & Molecular Biology Letters 2021, 26(1), 1. [Google Scholar]

- Tröster, V.; Wong, R. P.; Börgel, A.; Cakilkaya, B.; Renz, C.; Möckel, M. M.; Ulrich, H. D. Custom affinity probes reveal DNA-damage-induced, ssDNA-independent chromatin SUMOylation in budding yeast. Cell Reports 2025, 44(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.; Chen, C.; Pan, J.; Xu, J.; Zhou, Z. G.; Wang, C. Y. The Ubiquitin Proteasome Pathway (UPP) in the regulation of cell cycle control and DNA damage repair and its implication in tumorigenesis. International journal of clinical and experimental pathology 2012, 5(8), 726. [Google Scholar]

- Tubío-Santamaría, N.; Jayavelu, A. K.; Schnoeder, T. M.; Eifert, T.; Hsu, C. J.; Perner, F.; Heidel, F. H. Immunoproteasome function maintains oncogenic gene expression in KMT2A-complex driven leukemia. Molecular Cancer 2023, 22(1), 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyedmers, J.; Mogk, A.; Bukau, B. Cellular strategies for controlling protein aggregation. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology 2010, 11(11), 777–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uday, G.; Shardha, H. B.; Priyanka, K.; Jagirdhar, S. Advances in Plant Proteomics toward Improvement of Crop Productivity and Stress Resistance. Plant Proteomics: Implications in Growth, Quality Improvement, and Stress Resilience 2024, 11–29. [Google Scholar]

- Ulfig, A.; Jakob, U. Cellular oxidants and the proteostasis network: balance between activation and destruction. Trends in Biochemical Sciences 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, F. U. M.; Rho, S.; Lee, M. Y. Predictive modeling for ubiquitin proteins through advanced machine learning technique. Heliyon 2024, 10(12). [Google Scholar]

- van der Wal, L.; Bezstarosti, K.; Demmers, J. A. A ubiquitinome analysis to study the functional roles of the proteasome associated deubiquitinating enzymes USP14 and UCH37. Journal of Proteomics 2022, 262, 104592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voutsadakis, I. A. Ubiquitin-and ubiquitin-like proteins-conjugating enzymes (E2s) in breast cancer. Molecular biology reports 2013, 40(2), 2019–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, W.; Wu, Y.; Xing, D. New-generation advanced PROTACs as potential therapeutic agents in cancer therapy. Molecular Cancer 2024, 23(1), 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Maldonado, M. A. The ubiquitin-proteasome system and its role in inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. Cell Mol Immunol 2006, 3(4), 255–261. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Xiang, Y.; Fan, M.; Fang, S.; Hua, Q. The Ubiquitin–Proteasome System in Tumor Metabolism. Cancers 2023, 15(8), 2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Inuzuka, H.; Zhong, J.; Wan, L.; Fukushima, H.; Sarkar, F. H.; Wei, W. Tumor suppressor functions of FBW7 in cancer development and progression. FEBS letters 2012, 586(10), 1409–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Q.; Sun, L. Mass spectrometry-intensive top-down proteomics: an update on technology advancements and biomedical applications. Analytical Methods 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Liu, X.; Zhao, C.; Chen, G. Q. Applications of synthetic biology in medical and pharmaceutical fields. Signal transduction and targeted therapy 2023, 8(1), 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Zhao, J.; Chen, D.; Wang, Y. E3 ubiquitin ligases: styles, structures and functions. Molecular biomedicine 2021, 2, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, F.; Yu, C.; Li, F.; Zuo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yao, L.; Ye, L. Wnt/β-catenin signaling in cancers and targeted therapies. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2021, 6(1), 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Sidhu, S. S. Development of inhibitors in the ubiquitination cascade. FEBS letters 2014, 588(2), 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Chen, Z.; Liu, S.; Liu, S.; Liao, Y.; Du, A.; Xia, Z. A Cullin 5-based complex serves as an essential modulator of ORF9b stability in SARS-CoV-2 replication. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2024, 9(1), 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Q.; Liu, M.; Liu, K.; Zhang, Y.; North, B. J.; Wang, B. E3 ubiquitin ligases in cancer stem cells: key regulators of cancer hallmarks and novel therapeutic opportunities. Cellular Oncology 2023, 46(3), 545–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).