Submitted:

29 April 2025

Posted:

30 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

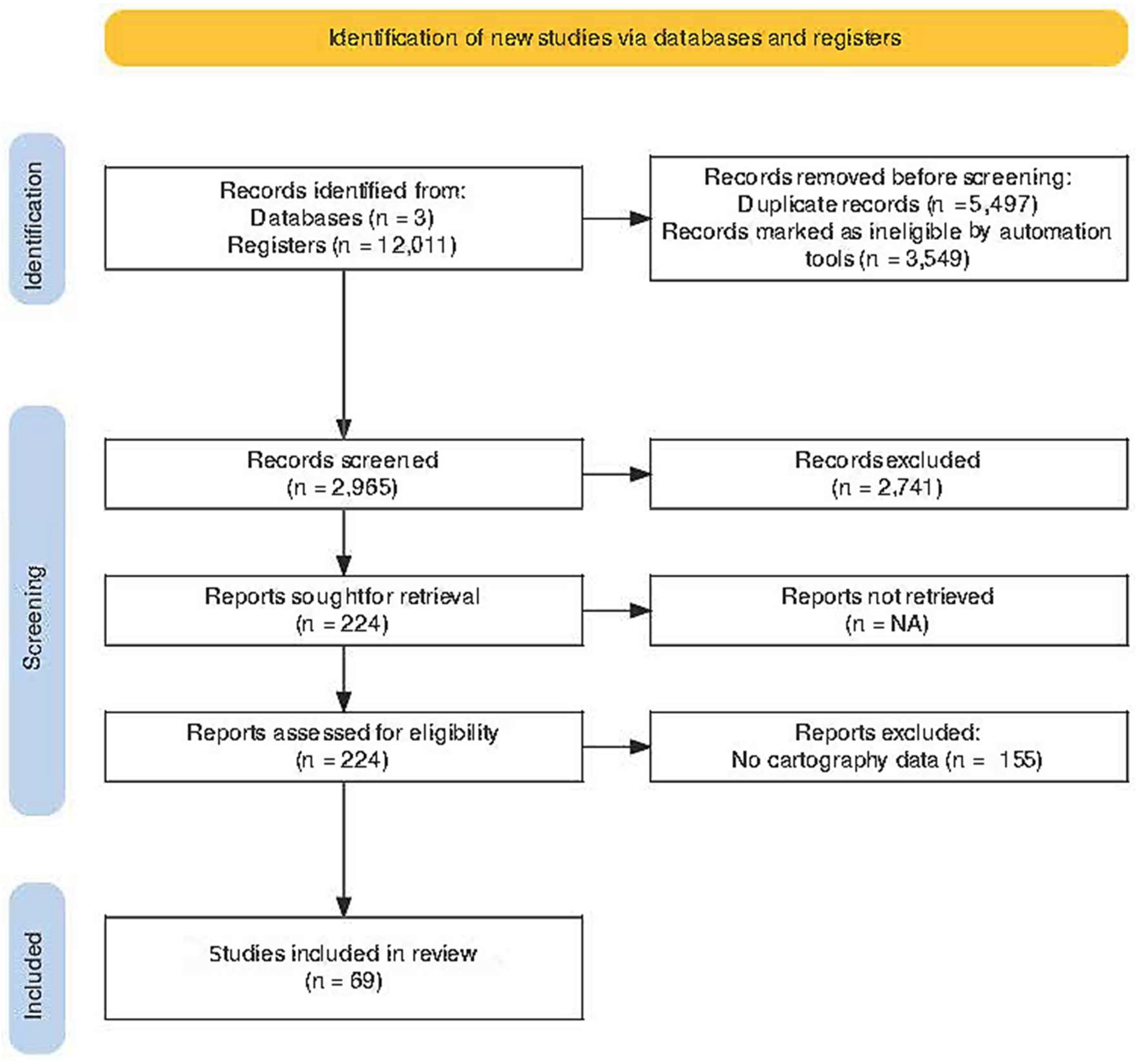

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Sources and Search Strategies

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Screening and Selection Process of Articles

2.6. Methodological Quality Assessment and Data Analysis

3. Results

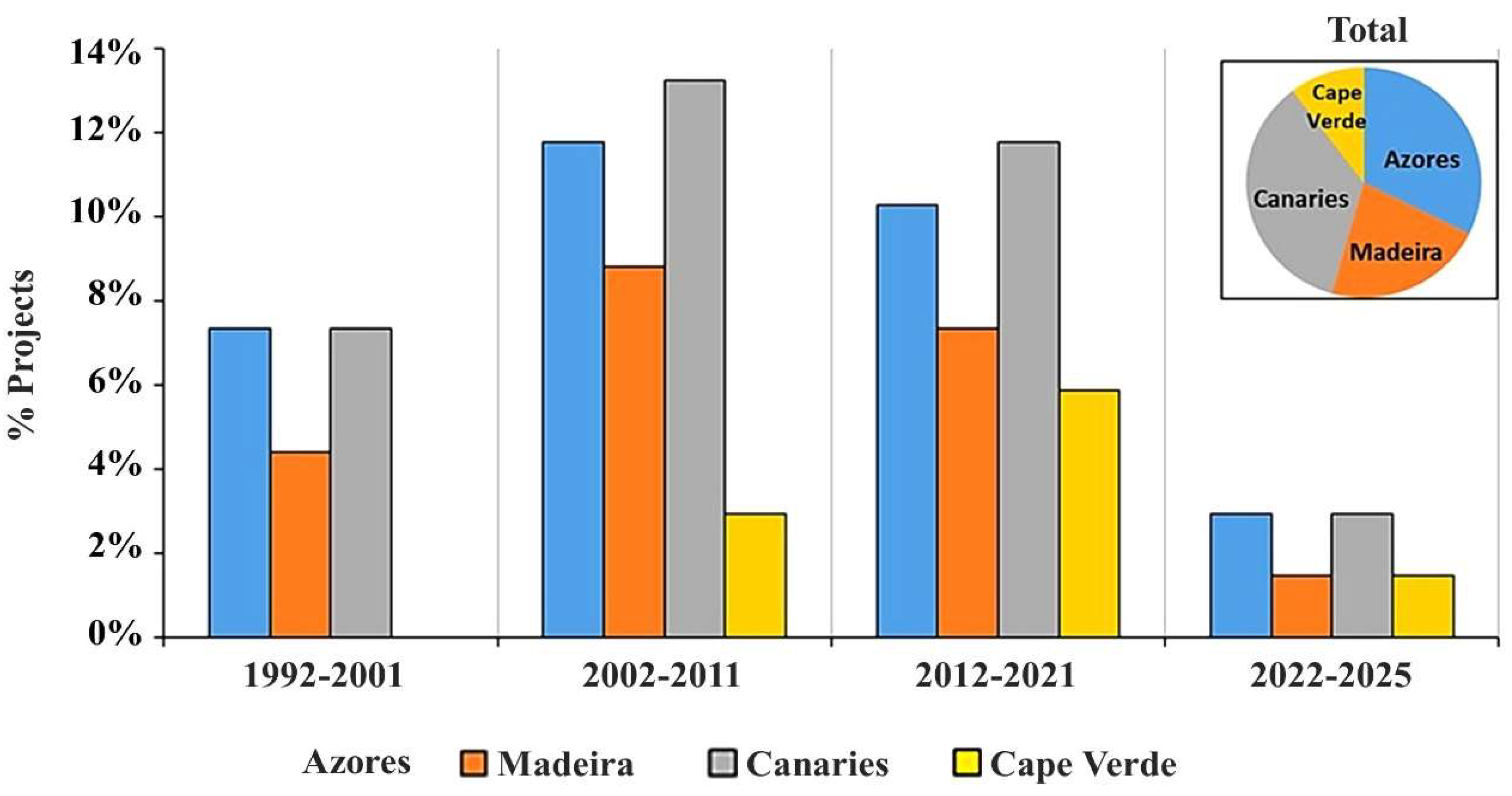

3.1. Research Effort and Objectives

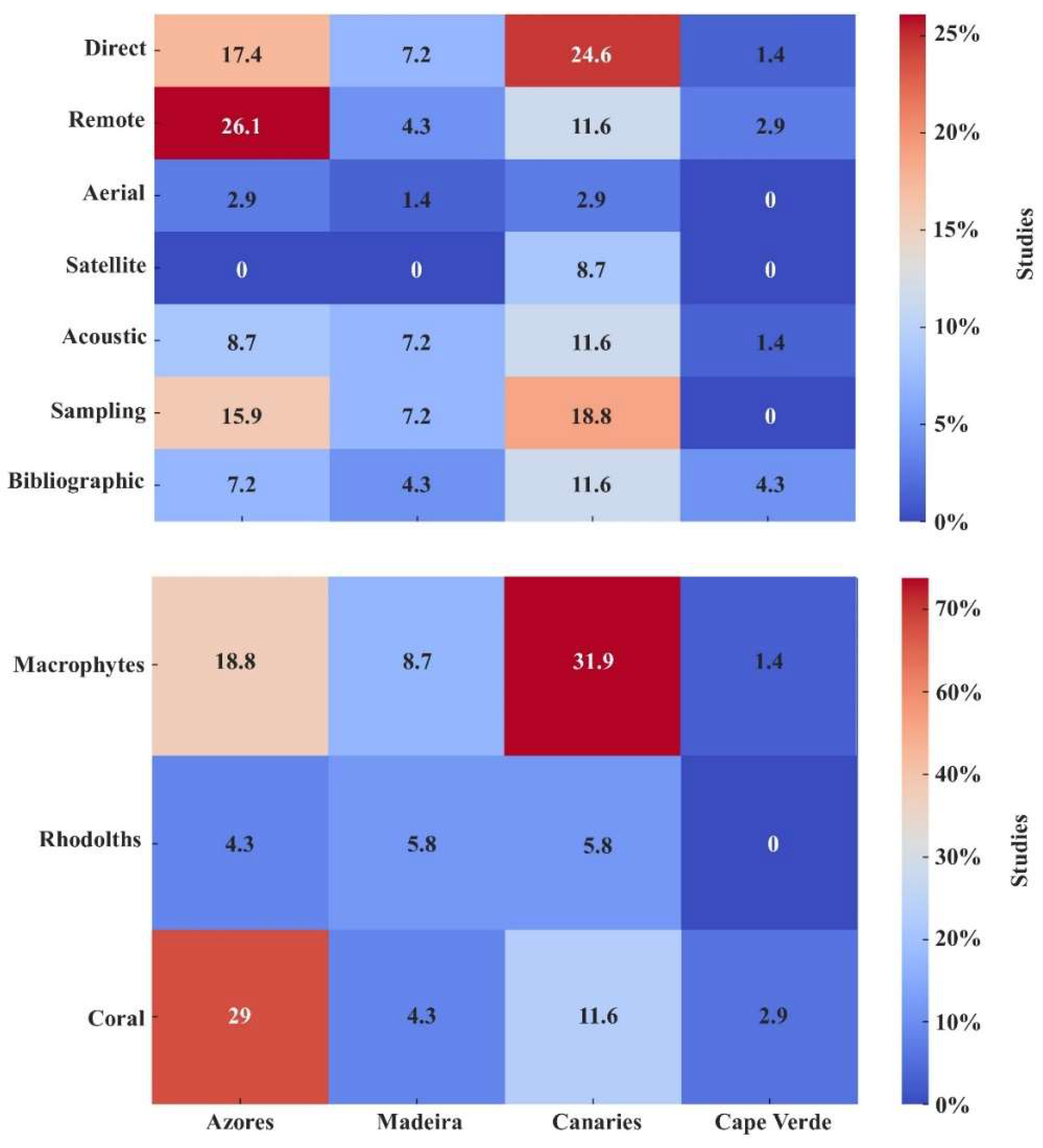

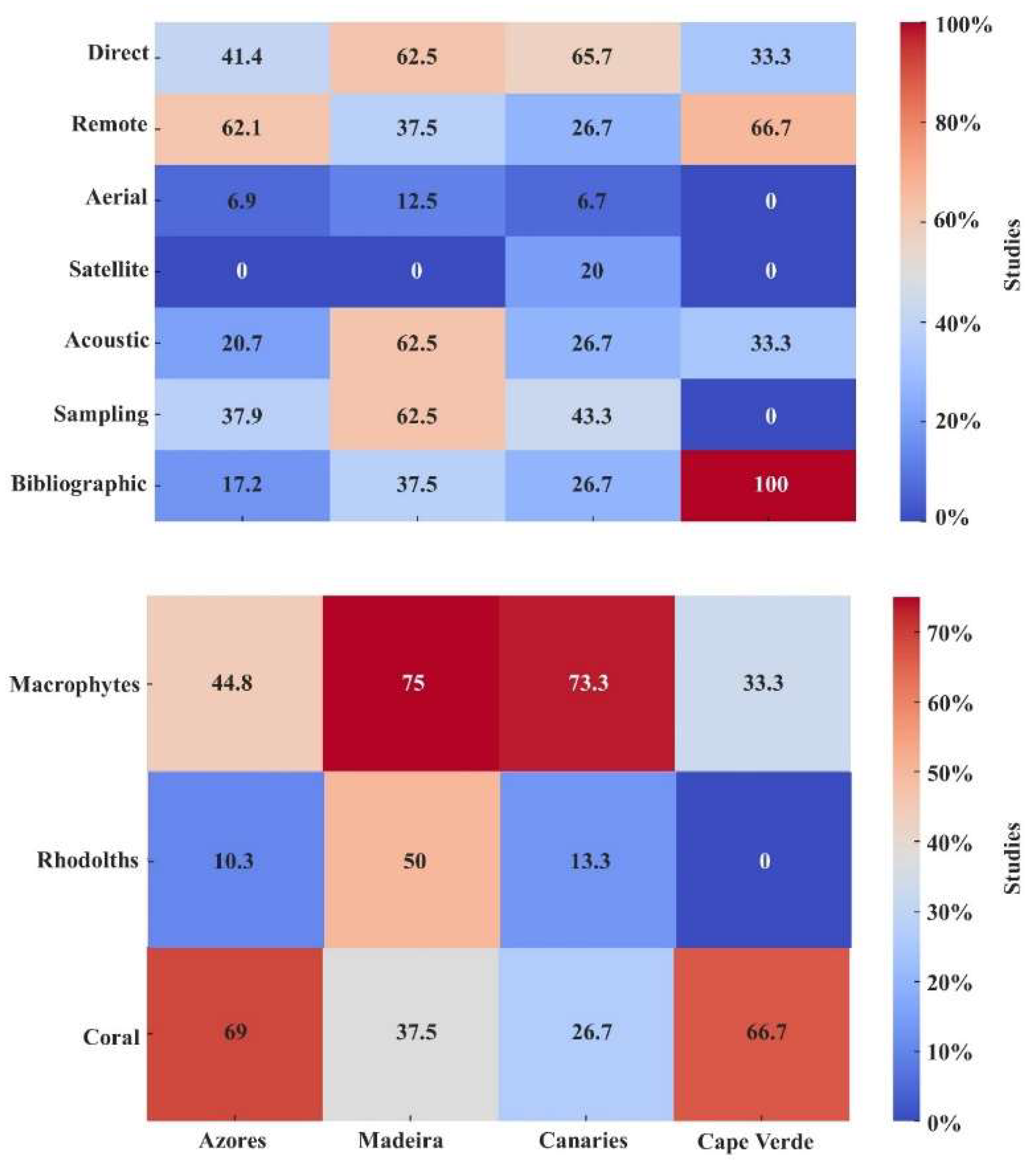

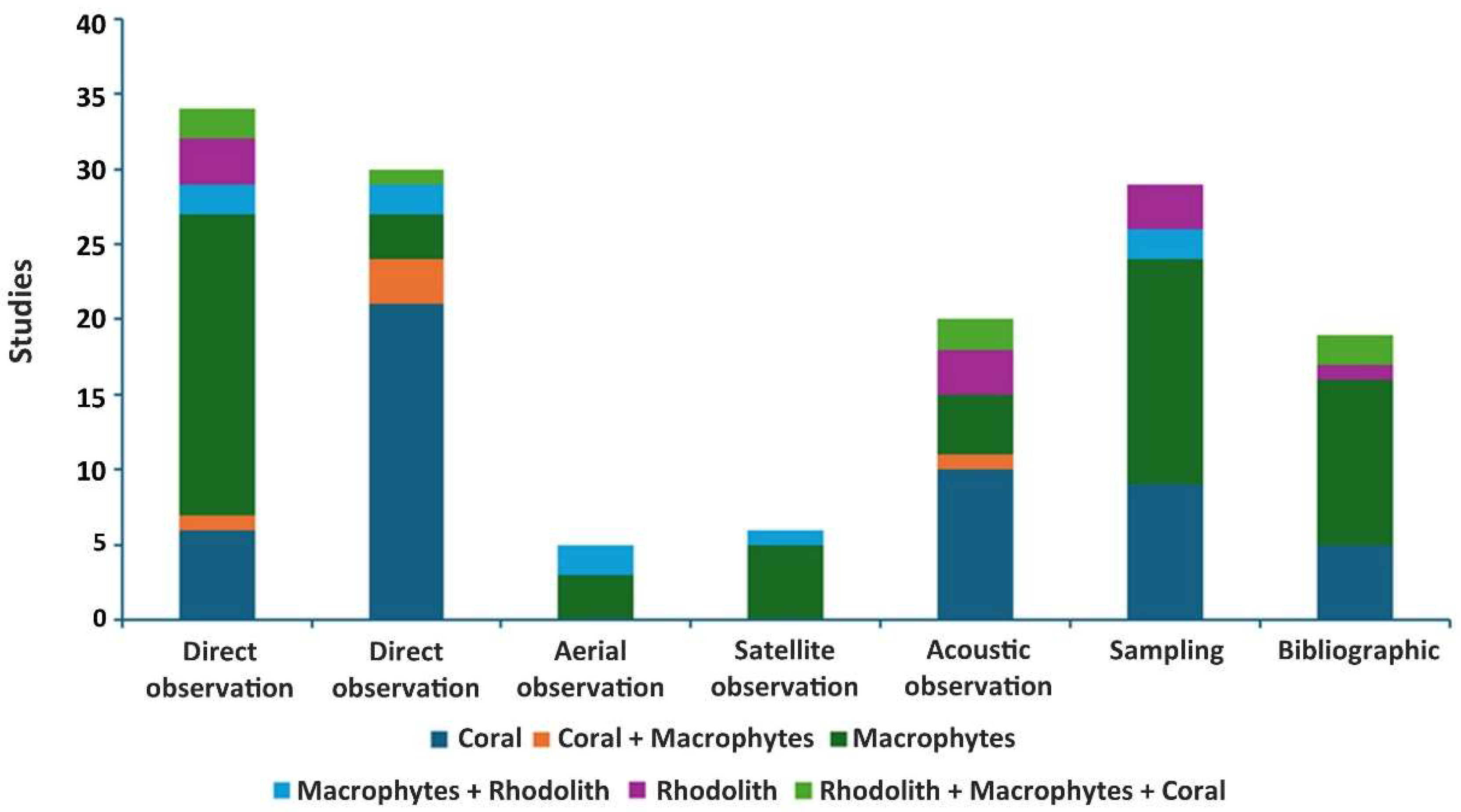

3.2. Methodologies and Habitats Analysis

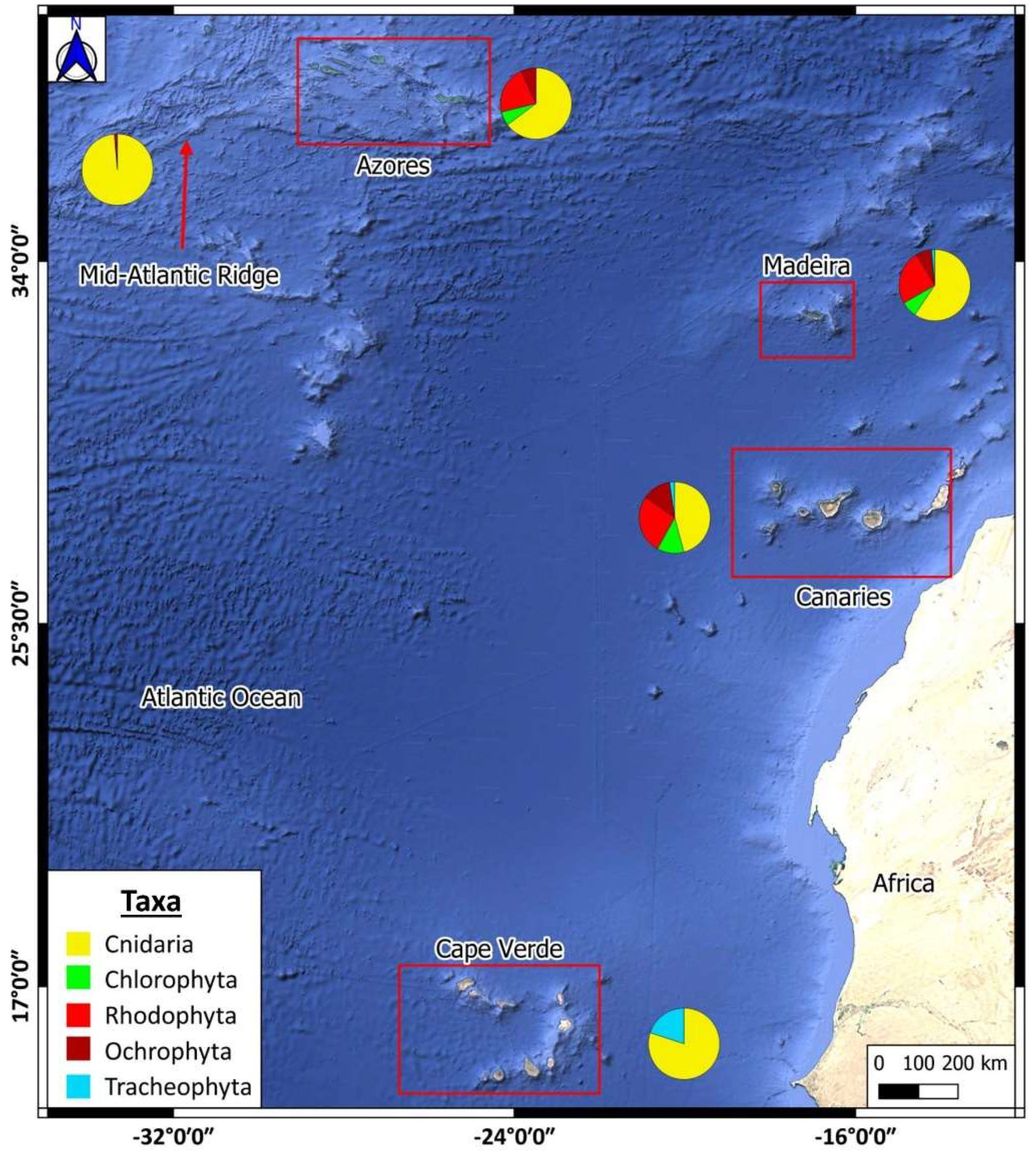

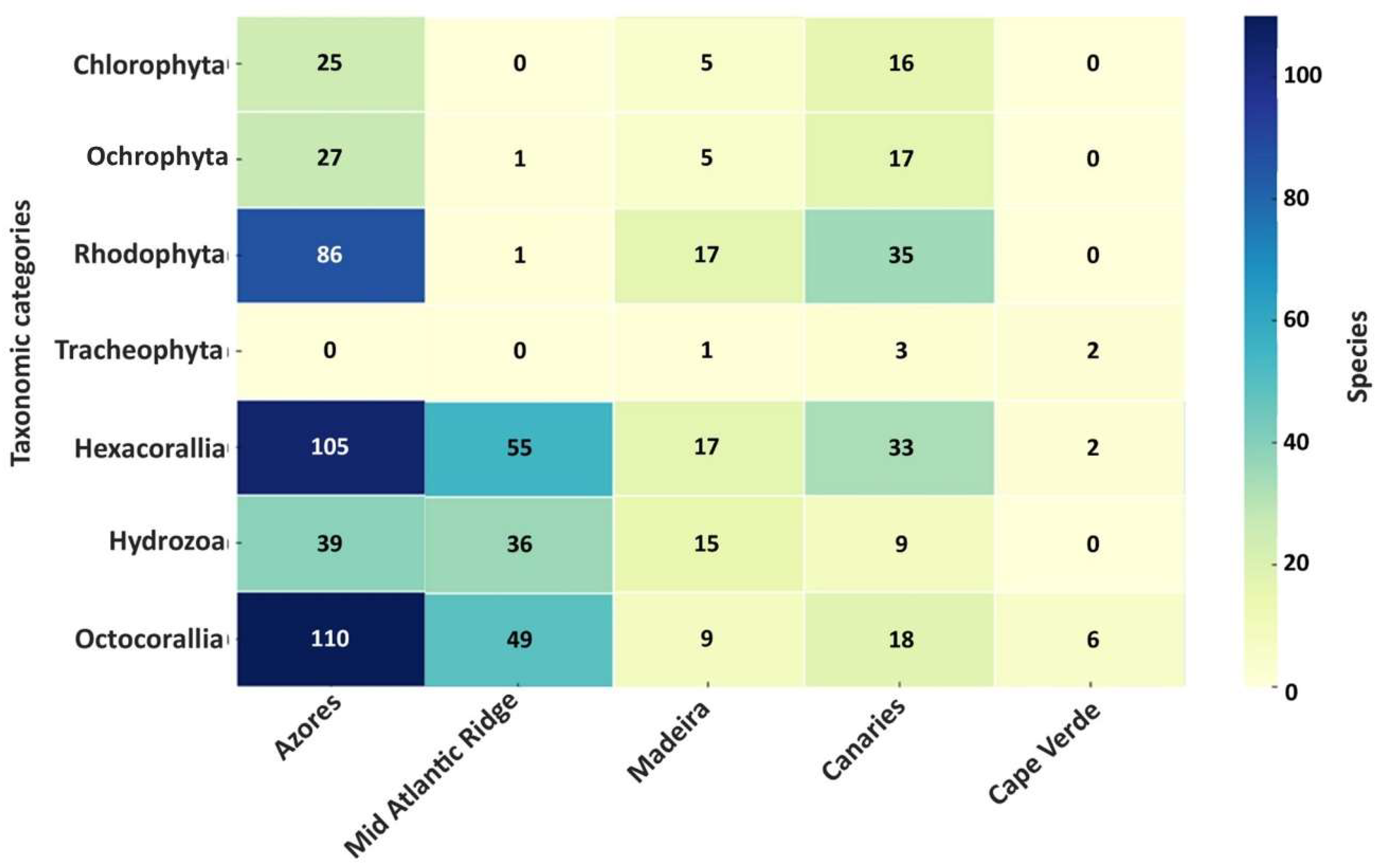

3.3. Biodiversity Analysis

3.4. Postprocessing Data Analyses

4. Discussion

4.1. Methodologies and Technological Advances

4.1.1. Direct and Remote Observation Techniques

4.1.2. Acoustic Methodologies

4.1.3. Aerial and Satellite Methodologies

4.1.4. Data Postprocessing

4.2. Habitat Mapping

4.2.1. Methodologies

4.2.2. Biotic-Abiotic Data

4.2.3. Habitat-Related Factors

4.2.4. Final Habitat Map in the Central-Eastern Atlantic Archipelagos

4.3. Challenges and Future Implications

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Habitats | ||||||||||||

| Paper | Reference | Year | Zone | Main objective | Macrophytes | Rhodolith beds | Coral | Habitat map | Geological map | Depth (m) | Substrate | Area size (ha) |

| 1 | [175] | 2021 | Madeira | exploratory | - | x | - | x | - | 35 | mixed | 2,368 |

| 2 | [198] | 2022 | Madeira | monitoring | x | - | - | x | - | 20 | soft | - |

| 3 | [131] | 2000 | Azores | monitoring | x | - | - | - | - | 40 | hard | - |

| 4 | [186] | 2000 | Azores | exploratory | - | - | x | - | - | 3800 | hard | - |

| 5 | [203] | 2008 | Azores | monitoring | x | - | - | x | - | 30 | hard | 400 |

| 6 | [136] | 2015 | Canary Islands | exploratory | - | - | x | - | - | 600 | hard | - |

| 7 | [140] | 2022 | Madeira | exploratory | x | x | x | - | - | 990 | mixed | 1,55 |

| 8 | [165] | 2017 | Canary Islands | mapping | x | - | - | x | - | 20 | mixed | - |

| 9 | [158] | 2022 | Azores | exploratory | - | - | x | - | - | 210 | mixed | 0,019 |

| 10 | [166] | 2015 | Azores | mapping | x | x | x | x | - | n/a | mixed | 167692,2 |

| 11 | [146] | 2023 | Canary Islands | mapping | - | - | x | x | - | 110 | mixed | 48,075 |

| 12 | [116] | 2012 | Azores | exploratory | - | - | x | - | - | 3,3 | mixed | - |

| 13 | [129] | 2017 | Azores, Canary Islands | exploratory | x | - | x | - | - | 734 | mixed | - |

| 14 | [204] | 1992 | Azores | exploratory | x | - | - | x | - | 5,5 | hard | - |

| 15 | [185] | 2013 | Madeira | mapping | - | - | x | x | x | 2660 | soft | 56000 |

| 16 | [143] | 2020 | Azores | exploratory | - | - | x | - | x | 1700 | hard | 0,045 |

| 17 | [196] | 2014 | Canary Islands | monitoring | x | - | - | - | - | 15 | soft | 393,9 |

| 18 | [195] | 2014 | Azores | monitoring | - | - | x | - | x | 1092 | hard | - |

| 19 | [205] | 2021 | Azores | exploratory | - | - | x | - | x | 595 | hard | - |

| 20 | [206] | 2013 | Azores | exploratory | - | - | x | - | x | 1097 | mixed | 2,378 |

| 21 | [176] | 2013 | Azores | exploratory | - | - | x | x | - | 1500 | hard | - |

| 22 | [15] | 2019 | Canary Islands | monitoring | - | x | - | x | - | 50 | mixed | 0,72 |

| 23 | [164] | 2021 | Canary Islands | monitoring | x | - | - | - | - | 75 | soft | - |

| 24 | [14] | 2020 | Canary Islands | monitoring | - | x | - | - | - | 40 | soft | - |

| 25 | [163] | 2024 | Canary Islands | monitoring | x | x | - | x | - | 25 | mixed | 2150 |

| 26 | [182] | 2024 | Cabo Verde | mapping | - | - | x | x | x | 2100 | hard | 118800 |

| 27 | [130] | 2022 | Canary Islands | monitoring | x | - | - | - | - | n/a | hard | - |

| 28 | [114] | 2020 | Madeira | mapping | x | x | x | x | - | 50 | mixed | 240 |

| 29 | [56] | 2024 | Azores | mapping | x | - | x | x | - | 60 | mixed | 394,08 |

| 30 | [207] | 2018 | Canary Islands | mapping | x | - | - | x | - | 50 | mixed | 9138 |

| 31 | [202] | 2013 | Canary Islands | exploratory | x | - | - | - | - | 19 | mixed | - |

| 32 | [208] | 2019 | Madeira | exploratory | x | - | - | - | - | 2,6 | mixed | - |

| 33 | [209] | 2006 | Azores | exploratory | x | - | - | x | - | 20 | hard | - |

| 34 | [200] | 2019 | Canary Islands | exploratory | - | - | x | x | - | 35 | hard | 0,018 |

| 35 | [148] | 2024 | Canary Islands | monitoring | x | - | - | x | - | 50 | hard | - |

| 36 | [173] | 2021 | Madeira | monitoring | x | - | - | - | - | 12 | soft | 0,009 |

| 37 | [4] | 2021 | Azores | mapping | x | - | - | x | - | 15 | mixed | - |

| 38 | [210] | 2012 | Canary Islands | exploratory | x | - | - | - | - | 46 | mixed | - |

| 39 | [211] | 2002 | Canary Islands | mapping | x | - | - | x | - | 10 | mixed | - |

| 40 | [212] | 2023 | Canary Islands | mapping | x | - | - | x | - | n/a | soft | - |

| 41 | [213] | 2012 | Azores | mapping | - | - | x | - | x | 1350 | hard | - |

| 42 | [214] | 2017 | Canary Islands | monitoring | x | - | - | x | - | 20 | hard | 7,4 |

| 43 | [215] | 2020 | Canary Islands | mapping | x | - | - | x | - | 40 | mixed | 746 |

| 44 | [162] | 2020 | Canary Islands | mapping | x | - | - | x | - | 40 | hard | 746 |

| 45 | [194] | 2016 | Canary Islands | mapping | - | - | x | - | x | 2500 | mixed | 367388 |

| 46 | [144] | 2020 | Azores | exploratory | - | - | x | x | x | 4000 | mixed | - |

| 47 | [216] | 2008 | Azores | exploratory | - | - | x | - | x | 2977 | mixed | - |

| 48 | [161] | 2015 | Canary Islands | mapping | x | - | - | x | - | 25 | mixed | - |

| 49 | [197] | 2023 | Azores | mapping | - | - | x | x | - | 2387 | mixed | 154 |

| 50 | [142] | 2012 | Azores | mapping | x | - | - | x | x | 80 | mixed | 53750 |

| 51 | [217] | 2023 | Azores | mapping | - | - | x | x | x | 2700 | hard | - |

| 52 | [199] | 2021 | Azores | exploratory | x | x | - | x | - | 85 | mixed | - |

| 53 | [218] | 2023 | Cabo Verde | exploratory | x | - | - | x | - | 5 | soft | 0,62 |

| 54 | [219] | 2023 | Azores | exploratory | - | - | x | x | - | 2000 | mixed | 2200000 |

| 55 | [220] | 2022 | Canary Islands | mapping | x | - | - | x | - | n/a | mixed | - |

| 56 | [221] | 2008 | Azores | monitoring | x | x | x | - | - | 30 | mixed | - |

| 57 | [46] | 2020 | Canary Islands | mapping | - | - | x | x | - | 173 | hard | 55 |

| 58 | [201] | 2021 | Canary Islands | mapping | - | - | x | x | x | 3000 | mixed | - |

| 59 | [141] | 2013 | Azores | mapping | - | - | x | - | x | 160 | hard | - |

| 60 | [183] | 2020 | Canary Islands | exploratory | x | - | - | x | - | 40 | mixed | - |

| 61 | [184] | 2013 | Canary Islands | mapping | x | - | x | x | - | 50 | mixed | 1574 |

| 62 | [150] | 2019 | Azores | monitoring | x | - | - | x | - | 10 | mixed | - |

| 63 | [167] | 2022 | Azores | exploratory | - | - | x | x | x | 1600 | hard | - |

| 64 | [115] | 2024 | Cabo Verde | exploratory | - | - | x | - | x | 3218 | mixed | 2,807 |

| 65 | [222] | 2013 | Canary Islands | exploratory | x | - | - | x | x | 45 | mixed | - |

| 66 | [160] | 2023 | Canary Islands | mapping | x | - | - | x | - | 20 | mixed | - |

| 67 | [151] | 2024 | Canary Islands | mapping | x | x | - | x | - | 10 | mixed | 58,5 |

| 68 | [149] | 2021 | Madeira | mapping | x | x | - | x | - | 14 | mixed | 10 |

| 69 | [120] | 2008 | Azores | mapping | x | - | - | - | - | 30 | mixed | - |

| Methologies | Data classification | ||||||||||||||

| Paper | Reference | Year | Direct observation | Remote observation | Aerial observation | Satellite observation | Acoustic observation | Sampling | Bibliographic | Modeling | GIS tools | Acoustic / Bathymetry | Image analysis | STATS | Taxonomic / Morphology |

| 1 | [175] | 2021 | x | - | - | - | x | x | x | - | x | - | x | - | - |

| 2 | [198] | 2022 | x | - | - | - | x | x | x | x | x | - | - | - | - |

| 3 | [131] | 2000 | - | - | - | - | - | - | x | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 4 | [186] | 2000 | - | x | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 5 | [203] | 2008 | x | - | - | - | - | x | - | - | - | - | - | - | x |

| 6 | [136] | 2015 | x | x | - | - | - | - | x | - | x | - | - | - | - |

| 7 | [140] | 2022 | - | x | - | - | x | - | - | - | - | - | x | - | - |

| 8 | [165] | 2017 | - | - | - | x | - | - | - | x | - | - | - | - | - |

| 9 | [158] | 2022 | - | x | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | x | - | - |

| 10 | [166] | 2015 | - | - | - | - | - | - | x | x | x | x | - | - | - |

| 11 | [146] | 2023 | x | x | - | - | x | - | - | x | x | x | - | - | - |

| 12 | [116] | 2012 | - | x | - | - | - | - | x | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 13 | [129] | 2017 | x | x | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | x | - | - |

| 14 | [204] | 1992 | x | - | - | - | - | x | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 15 | [185] | 2013 | - | x | - | - | x | x | - | x | x | x | - | - | - |

| 16 | [143] | 2020 | - | x | - | - | x | - | - | x | - | - | x | - | - |

| 17 | [196] | 2014 | x | - | - | - | - | x | - | x | - | - | - | - | - |

| 18 | [195] | 2014 | x | x | - | - | - | - | - | x | x | - | - | - | - |

| 19 | [205] | 2021 | - | x | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 20 | [206] | 2013 | - | x | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | x | - | - |

| 21 | [176] | 2013 | x | x | - | - | - | x | x | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 22 | [15] | 2019 | x | - | - | - | x | x | - | - | x | - | - | - | - |

| 23 | [164] | 2021 | - | - | - | x | - | - | x | x | x | - | - | - | - |

| 24 | [14] | 2020 | x | - | - | - | x | x | - | - | x | - | - | - | - |

| 25 | [163] | 2024 | - | - | - | x | - | - | - | x | - | - | - | x | - |

| 26 | [182] | 2024 | - | x | - | - | x | - | x | x | - | - | x | x | - |

| 27 | [130] | 2022 | x | - | - | - | - | - | x | x | x | - | - | - | - |

| 28 | [114] | 2020 | x | - | - | - | x | - | x | - | x | - | - | - | - |

| 29 | [56] | 2024 | - | x | - | - | x | - | - | - | x | x | - | - | - |

| 30 | [207] | 2018 | x | x | - | - | - | x | - | x | - | - | - | x | - |

| 31 | [202] | 2013 | x | - | - | - | - | x | - | - | - | - | - | - | x |

| 32 | [208] | 2019 | x | - | - | - | - | x | - | - | - | - | x | - | - |

| 33 | [209] | 2006 | x | - | - | - | - | x | - | - | - | - | - | x | - |

| 34 | [200] | 2019 | x | - | - | - | - | x | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 35 | [148] | 2024 | - | - | x | - | - | - | x | x | x | - | x | - | - |

| 36 | [173] | 2021 | x | - | - | - | - | x | - | - | x | - | x | - | - |

| 37 | [4] | 2021 | x | - | x | - | - | x | - | x | x | - | x | x | - |

| 38 | [210] | 2012 | x | - | - | - | - | x | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 39 | [211] | 2002 | - | x | - | - | - | - | - | x | - | - | x | - | - |

| 40 | [212] | 2023 | x | - | - | - | x | - | x | x | x | - | - | - | - |

| 41 | [213] | 2012 | - | - | - | - | - | x | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 42 | [214] | 2017 | x | - | - | - | - | x | - | - | x | - | - | - | - |

| 43 | [215] | 2020 | - | - | - | x | - | - | x | x | - | - | - | - | - |

| 44 | [162] | 2020 | x | - | - | - | - | x | x | x | - | - | - | - | - |

| 45 | [194] | 2016 | - | x | - | - | x | x | - | x | x | x | - | - | - |

| 46 | [144] | 2020 | - | x | - | - | x | - | - | x | - | x | - | - | - |

| 47 | [216] | 2008 | - | x | - | - | - | x | - | - | - | - | - | - | x |

| 48 | [161] | 2015 | - | - | - | x | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | x | - |

| 49 | [197] | 2023 | - | x | - | - | - | - | - | x | - | x | - | - | - |

| 50 | [142] | 2012 | x | x | - | - | x | x | x | x | x | x | - | - | - |

| 51 | [217] | 2023 | - | x | - | - | x | - | - | x | - | x | - | - | - |

| 52 | [199] | 2021 | x | x | - | - | - | x | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 53 | [218] | 2023 | x | - | - | - | - | - | x | - | x | - | - | - | - |

| 54 | [219] | 2023 | - | - | - | - | - | x | - | x | x | - | - | - | - |

| 55 | [220] | 2022 | - | - | - | - | - | - | x | x | - | - | - | x | - |

| 56 | [221] | 2008 | x | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | x |

| 57 | [46] | 2020 | x | - | - | - | x | x | - | - | x | x | - | - | - |

| 58 | [201] | 2021 | - | x | - | - | x | x | - | x | x | x | - | - | - |

| 59 | [141] | 2013 | - | x | - | - | x | - | - | - | x | - | - | - | - |

| 60 | [183] | 2020 | x | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | x | - | - | - | - |

| 61 | [184] | 2013 | - | x | - | - | x | - | - | x | x | x | - | x | - |

| 62 | [150] | 2019 | x | - | x | - | - | - | - | x | x | - | x | - | - |

| 63 | [167] | 2022 | - | x | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | x | x | - | - |

| 64 | [115] | 2024 | - | x | - | - | - | - | x | - | x | x | - | - | - |

| 65 | [222] | 2013 | - | - | - | - | x | - | - | x | x | x | - | - | - |

| 66 | [160] | 2023 | - | - | - | x | - | - | - | x | x | - | x | - | - |

| 67 | [151] | 2024 | x | - | x | - | - | x | - | x | x | - | x | x | - |

| 68 | [149] | 2021 | - | x | x | - | - | - | - | x | x | - | x | x | - |

| 69 | [120] | 2008 | x | - | - | - | - | x | - | x | - | - | x | x | - |

| Species | Order | Family | Studies | Azores | Madeira | Canary Islands | Cabo Verde | Atlantic Mid-Ridge |

| Phyllum Cnidaria | ||||||||

| Subphyllum Anthozoa | ||||||||

| Anthozoa | 1 | x | - | - | - | - | ||

| Class Hexacorallia | ||||||||

| Elatopathes aff. abietina (Pourtalès, 1874) | Antipatharia | Aphanipathidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Actiniaria | Actiniaria | 4 | x | - | - | x | x | |

| Anemonia viridis (Forsskål, 1775) | Actiniaria | Actiniidae | 1 | - | x | - | - | - |

| Actinoscyphia aurelia (Stephenson, 1918) | Actiniaria | Actinoscyphiidae | 1 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Parasicyonis ingolfi Carlgren, 1942 | Actiniaria | Actinostolidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Parasicyonis Carlgren, 1921 | Actiniaria | Actinostolidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Telmatactis cricoides (Duchassaing, 1850) | Actiniaria | Andvakiidae | 1 | - | x | - | - | - |

| Antipatharia | Antipatharia | 3 | x | - | - | - | x | |

| Antipathes furcata Gray, 1857 | Antipatharia | Antipathidae | 1 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Antipathes grayi (Roule, 1902) | Antipatharia | Antipathidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Antipathes virgata Esper, 1798 | Antipatharia | Antipathidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Antipathes Pallas, 1766 | Antipatharia | Antipathidae | 2 | x | x | - | - | - |

| Stichopathes flagellum Roule, 1902 | Antipatharia | Antipathidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Stichopathes gracilis (Gray, 1857) | Antipatharia | Antipathidae | 1 | x | - | x | - | x |

| Stichopathes gravieri Molodtsova, 2006 | Antipatharia | Antipathidae | 2 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Stichopathes richardi Roule, 1902 | Antipatharia | Antipathidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Stichopathes Brook, 1889 | Antipatharia | Antipathidae | 4 | x | x | x | - | x |

| Elatopathes Opresko, 2004 | Antipatharia | Aphanipathidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Aphanostichopathes dissimilis (Roule, 1902) | Antipatharia | Aphanipathidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Distichopathes Opresko, 2004 | Antipatharia | Aphanipathidae | 2 | x | x | - | - | - |

| Phanopathes erinaceus (Roule, 1905) | Antipatharia | Aphanipathidae | 2 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Heteropathes Opresko, 2011 | Antipatharia | Cladopathidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Leiopathes expansa Johnson, 1899 | Antipatharia | Leiopathidae | 2 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Leiopathes glaberrima (Esper, 1792) | Antipatharia | Leiopathidae | 3 | x | - | x | - | - |

| Leiopathes grimaldii Roule, 1902 | Antipatharia | Leiopathidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Leiopathes Haime, 1849 | Antipatharia | Leiopathidae | 1 | x | - | x | - | x |

| Leiopathes Haime, 1849 | Antipatharia | Leiopathidae | 4 | x | - | x | - | x |

| Antipathella subpinnata (Ellis & Solander, 1786) | Antipatharia | Myriopathidae | 4 | x | - | x | - | x |

| Antipathella wollastoni (Gray, 1857) | Antipatharia | Myriopathidae | 8 | x | - | x | - | x |

| Antipathella Brook, 1889 | Antipatharia | Myriopathidae | 3 | x | - | x | - | x |

| Tanacetipathes squamosa (Koch, 1886) | Antipatharia | Myriopathidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Tanacetipathes Opresko, 2001 | Antipatharia | Myriopathidae | 4 | x | x | - | - | x |

| Bathypathes patula Brook, 1889 | Antipatharia | Schizopathidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Bathypathes Brook, 1889 | Antipatharia | Schizopathidae | 3 | x | - | x | - | x |

| Stauropathes punctata (Roule, 1905) | Antipatharia | Schizopathidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Stauropathes arctica (Lütken, 1871) | Antipatharia | Schizopathidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Parantipathes hirondelle Molodtsova, 2006 | Antipatharia | Schizopathidae | 2 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Parantipathes Brook, 1889 | Antipatharia | Schizopathidae | 2 | x | x | - | - | x |

| Ceriantharia | Ceriantharia | 1 | x | - | - | - | - | |

| Pachycerianthus Roule, 1904 | Ceriantharia | Cerianthidae | 1 | - | x | - | - | - |

| Scleractinia | Scleractinia | 2 | x | - | - | - | x | |

| Coenocyathus cylindricus Milne Edwards y Haime, 1848 | Scleractinia | Caryophylliidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Concentrotheca laevigata (Pourtalès, 1871) | Scleractinia | Caryophylliidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Dasmosmilia lymani (Pourtalès, 1871) | Scleractinia | Caryophylliidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Dasmosmilia variegata (Pourtalès, 1871) | Scleractinia | Caryophylliidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Desmophyllum dianthus (Esper, 1794) | Scleractinia | Caryophylliidae | 5 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Desmophyllum pertusum (Linnaeus, 1758) | Scleractinia | Caryophylliidae | 8 | x | - | x | - | x |

| Desmophyllum Ehrenberg, 1834 | Scleractinia | Caryophylliidae | 2 | x | - | x | - | x |

| Pourtalosmilia anthophyllites (Ellis & Solander, 1786) | Scleractinia | Caryophylliidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Premocyathus cornuformis (Pourtalès, 1868) | Scleractinia | Caryophylliidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Anomocora fecunda (Pourtalès, 1871) | Scleractinia | Caryophylliidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Paracyathus pulchellus (Philippi, 1842) | Scleractinia | Caryophylliidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Phyllangia americana Milne Edwards & Haime, 1849 | Scleractinia | Caryophylliidae | 1 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Polycyathus muellerae (Abel, 1959) | Scleractinia | Caryophylliidae | 1 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Polycyathus senegalensis Chevalier, 1966 | Scleractinia | Caryophylliidae | 1 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Aulocyathus atlanticus Zibrowius, 1980 | Scleractinia | Caryophylliidae | 2 | x | x | - | - | x |

| Caryophyllia (Caryophyllia) abyssorum Duncan, 1873 | Scleractinia | Caryophylliidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Caryophyllia (Caryophyllia) alberti Zibrowius, 1980 | Scleractinia | Caryophylliidae | 3 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Caryophyllia (Caryophyllia) atlantica (Duncan, 1873) | Scleractinia | Caryophylliidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Caryophyllia (Caryophyllia) calveri Duncan, 1873 | Scleractinia | Caryophylliidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Caryophyllia (Caryophyllia) cyathus (Ellis & Solander, 1786) | Scleractinia | Caryophylliidae | 2 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Caryophyllia (Caryophyllia) foresti Zibrowius, 1980 | Scleractinia | Caryophylliidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Caryophyllia (Caryophyllia) inornata (Duncan, 1878) | Scleractinia | Caryophylliidae | 2 | x | - | x | - | - |

| Caryophyllia (Caryophyllia) sarsiae Zibrowius, 1974 | Scleractinia | Caryophylliidae | 2 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Caryophyllia (Caryophyllia) smithii Stokes & Broderip, 1828 | Scleractinia | Caryophylliidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Caryophyllia (Caryophyllia) Lamarck, 1801 | Scleractinia | Caryophylliidae | 5 | x | - | x | - | x |

| Caryophylliidae Dana, 1846 | Scleractinia | Caryophylliidae | 2 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Solenosmilia variabilis Duncan, 1873 | Scleractinia | Caryophylliidae | 5 | x | - | x | - | x |

| Solenosmilia Duncan, 1873 | Scleractinia | Caryophylliidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Tethocyathus variabilis Cairns, 1979 | Scleractinia | Caryophylliidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Trochocyathus (Trochocyathus) spinosocostatus Zibrowius, 1980 | Scleractinia | Caryophylliidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Deltocyathus eccentricus Cairns, 1979 | Scleractinia | Deltocyathidae | 2 | x | x | - | - | x |

| Deltocyathus italicus (Michelotti, 1838) | Scleractinia | Deltocyathidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Deltocyathus moseleyi Cairns, 1979 | Scleractinia | Deltocyathidae | 2 | x | x | - | - | x |

| Dendrophyllia alternata Pourtalès, 1880 | Scleractinia | Dendrophylliidae | 2 | x | - | x | - | x |

| Dendrophyllia cornigera (Lamarck, 1816) | Scleractinia | Dendrophylliidae | 4 | x | x | x | - | x |

| Dendrophyllia ramea (Linnaeus, 1758) | Scleractinia | Dendrophylliidae | 4 | x | x | x | - | x |

| Dendrophyllia de Blainville, 1830 | Scleractinia | Dendrophylliidae | 2 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Enallopsammia pusilla (Alcock, 1902) | Scleractinia | Dendrophylliidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Enallopsammia rostrata (Pourtalès, 1878) | Scleractinia | Dendrophylliidae | 4 | x | - | - | x | x |

| Enallopsammia Michelloti, 1871 | Scleractinia | Dendrophylliidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Leptopsammia formosa (Gravier, 1915) | Scleractinia | Dendrophylliidae | 2 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Balanophyllia (Balanophyllia) cellulosa Duncan, 1873 | Scleractinia | Dendrophylliidae | 2 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Tubastraea coccinea Lesson, 1830 | Scleractinia | Dendrophylliidae | 1 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Tubastraea tagusensis Wells, 1982 | Scleractinia | Dendrophylliidae | 1 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Tubastraea Lesson, 1830 | Scleractinia | Dendrophylliidae | 1 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Javania cailleti (Duchassaing & Michelotti, 1864) | Scleractinia | Flabellidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Javania pseudoalabastra Zibrowius, 1974 | Scleractinia | Flabellidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Flabellum (Flabellum) chunii Marenzeller, 1904 | Scleractinia | Flabellidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Flabellum (Ulocyathus) alabastrum Moseley, 1876 | Scleractinia | Flabellidae | 2 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Flabellum (Ulocyathus) angulare Moseley, 1876 | Scleractinia | Flabellidae | 2 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Flabellum (Ulocyathus) macandrewi Gray, 1849 | Scleractinia | Flabellidae | 2 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Flabellum Lesson, 1831 | Scleractinia | Flabellidae | 3 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Fungiacyathus (Bathyactis) crispus (Pourtalès, 1871) | Scleractinia | Fungiacyathidae | 2 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Fungiacyathus (Bathyactis) marenzelleri (Vaughan, 1906) | Scleractinia | Fungiacyathidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Fungiacyathus (Bathyactis) symmetricus (Pourtalès, 1871) | Scleractinia | Fungiacyathidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Fungiacyathus (Fungiacyathus) fragilis Sars, 1872 | Scleractinia | Fungiacyathidae | 3 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Guynia annulata Duncan, 1872 | Scleractinia | Guyniidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Madrepora oculata Linnaeus, 1758 | Scleractinia | Madreporidae | 8 | x | x | x | - | x |

| Oculina patagonica de Angelis D’Ossat, 1908 | Scleractinia | Oculinidae | 1 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Oculina Lamarck, 1816 | Scleractinia | Oculinidae | 1 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Madracis pharensis (Heller, 1868) | Scleractinia | Pocilloporidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Madracis profunda Zibrowius, 1980 | Scleractinia | Pocilloporidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Madracis Milne Edwards & Haime, 1849 | Scleractinia | Pocilloporidae | 1 | - | x | - | - | - |

| Culicia tenella Dana, 1846 | Scleractinia | Rhizangiidae | 1 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Culicia Dana, 1846 | Scleractinia | Rhizangiidae | 1 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Schizocyathidae Stolarski, 2000 | Scleractinia | Schizocyathidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Schizocyathus fissilis Pourtalès, 1874 | Scleractinia | Schizocyathidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Stenocyathus vermiformis (Pourtalès, 1868) | Scleractinia | Stenocyathidae | 3 | x | x | - | - | x |

| Stephanocyathus (Odontocyathus) nobilis (Moseley, 1876) | Scleractinia | Stephanocyathidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Stephanocyathus (Stephanocyathus) crassus (Jourdan, 1895) | Scleractinia | Stephanocyathidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Stephanocyathus (Stephanocyathus) diadema (Moseley, 1876) | Scleractinia | Stephanocyathidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Stephanocyathus (Stephanocyathus) moseleyanus (Sclater, 1886) | Scleractinia | Stephanocyathidae | 2 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Vaughanella concinna Gravier, 1915 | Scleractinia | Stephanocyathidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Peponocyathus stimpsonii (Pourtalès, 1871) | Scleractinia | Turbinoliidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Sphenotrochus (Sphenotrochus) andrewianus Milne Edwards & Haime, 1848 | Scleractinia | Turbinoliidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Thrypticotrochus Cairns, 1989 | Scleractinia | Turbinoliidae | 1 | - | - | - | - | x |

| Peponocyathus folliculus (Pourtalès, 1868) | Scleractinia | Turbinoliidae | 2 | x | x | - | - | x |

| Zoantharia | Zoantharia | 1 | x | - | - | - | x | |

| Epizoanthus martinsae Carreiro-Silva, Ocaña, Stanković, Sampaio, Porteiro, Fabri & Stefanni, 2017 | Zoantharia | Epizoanthidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Parazoanthus Haddon & Shackleton, 1891 | Zoantharia | Parazoanthidae | 1 | x | - | x | - | x |

| Savalia savaglia (Bertoloni, 1819) | Zoantharia | Parazoanthidae | 1 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Palythoa canariensis Haddon & Duerden, 1896 | Zoantharia | Sphenopidae | 1 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Zoanthidae Rafinesque, 1815 | Zoantharia | Zoanthidae | 2 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Class Octocorallia | ||||||||

| Octocorallia | 5 | x | - | x | x | x | ||

| Rolandia coralloides de Lacaze Duthiers, 1900 | Alcyonacea | Clavulariidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Malacalcyonacea | Malacalcyonacea | 1 | x | - | - | - | - | |

| Acanthogorgia armata Verrill, 1878 | Malacalcyonacea | Acanthogorgiidae | 3 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Acanthogorgia aspera Pourtalès, 1867 | Malacalcyonacea | Acanthogorgiidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Acanthogorgia hirsuta Gray, 1857 | Malacalcyonacea | Acanthogorgiidae | 3 | x | - | x | - | x |

| Acanthogorgia muricata Verrill, 1883 | Malacalcyonacea | Acanthogorgiidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Acanthogorgia pico Grasshoff, 1973 | Malacalcyonacea | Acanthogorgiidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Acanthogorgia sp. Gray, 1857 | Malacalcyonacea | Acanthogorgiidae | 4 | x | - | x | - | x |

| Bebryce mollis Philippi, 1842 | Malacalcyonacea | Acanthogorgiidae | 3 | x | x | - | - | x |

| Dentomuricea meteor Grasshoff, 1977 | Malacalcyonacea | Acanthogorgiidae | 7 | x | x | x | - | x |

| Dentomuricea Grasshoff, 1977 | Malacalcyonacea | Acanthogorgiidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Muriceides lepida Carpine & Grasshoff, 1975 | Malacalcyonacea | Acanthogorgiidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Muriceides sceptrum (Studer, 1891) | Malacalcyonacea | Acanthogorgiidae | 2 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Placogorgia becena Grasshoff, 1977 | Malacalcyonacea | Acanthogorgiidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Placogorgia coronata Carpine & Grasshoff, 1975 | Malacalcyonacea | Acanthogorgiidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Placogorgia intermedia (Thomson, 1927) | Malacalcyonacea | Acanthogorgiidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Villogorgia bebrycoides (von Koch, 1887) | Malacalcyonacea | Acanthogorgiidae | 2 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Gersemia clavata (Danielssen, 1887) | Malacalcyonacea | Alcyoniidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Azoriella bayeri (López-González & Gili, 2001) | Malacalcyonacea | Cerveridae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Clavularia arctica (Sars, 1860) | Malacalcyonacea | Clavulariidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Clavularia armata Thomson, 1927 | Malacalcyonacea | Clavulariidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Clavularia charcoti (Tixier-Durivault & d’Hondt, 1974) | Malacalcyonacea | Clavulariidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Clavularia elongata Wright & Studer, 1889 | Malacalcyonacea | Clavulariidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Clavularia marioni von Koch, 1890 | Malacalcyonacea | Clavulariidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Clavularia tenuis Tixier-Durivault & d’Hondt, 1974 | Malacalcyonacea | Clavulariidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Clavularia Blainville, 1830 | Malacalcyonacea | Clavulariidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Schizophytum echinatum Studer, 1891 | Malacalcyonacea | Clavulariidae | 2 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Eunicella verrucosa (Pallas, 1766) | Malacalcyonacea | Eunicellidae | 1 | - | x | - | - | - |

| Eunicella Verrill, 1869 | Malacalcyonacea | Eunicellidae | 1 | - | x | - | - | - |

| Pseudotelestula humilis (Thomson, 1927) | Malacalcyonacea | Incrustatidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Thesea rigida (Thomson, 1927) | Malacalcyonacea | Malacalcyonacea incertae sedis | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Nephtheidae Gray, 1862 | Malacalcyonacea | Nephtheidae | 1 | - | x | - | - | - |

| Scleronephthya macrospina Thomson, 1927 | Malacalcyonacea | Nephtheidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Plexauridae Gray, 1859 | Malacalcyonacea | Plexauridae | 3 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Dacrygorgia modesta (Verrill, 1883) | Malacalcyonacea | Pterogorgiidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Sarcophyton Lesson, 1834 | Malacalcyonacea | Sarcophytidae | 1 | - | x | - | - | - |

| Bathytelesto rigida (Wright & Studer, 1889) | Malacalcyonacea | Tubiporidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Scyphopodium ingolfi (Madsen, 1944) | Malacalcyonacea | Tubiporidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Scleranthelia rugosa (Pourtalès, 1867) | Octocorallia incertae sedis | Octocorallia incertae sedis | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Scleralcyonacea | Scleralcyonacea | 2 | x | - | - | x | x | |

| Chelidonisis aurantiaca Studer, 1890 | Scleralcyonacea | Chelidonisididae | 2 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Chrysogorgia agassizii (Verrill, 1883) | Scleralcyonacea | Chrysogorgiidae | 3 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Chrysogorgia fewkesii Verrill, 1883 | Scleralcyonacea | Chrysogorgiidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Chrysogorgia quadruplex Thomson, 1927 | Scleralcyonacea | Chrysogorgiidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Chrysogorgia Duchassaing & Michelotti, 1864 | Scleralcyonacea | Chrysogorgiidae | 3 | x | - | x | - | x |

| Parachrysogorgia squamata (Verrill, 1883) | Scleralcyonacea | Chrysogorgiidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Radicipes gracilis (Verrill, 1884) | Scleralcyonacea | Chrysogorgiidae | 2 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Chrysogorgia elegans (Verrill, 1883) | Scleralcyonacea | Chrysogorgiidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Pleurocorallium johnsoni (Gray, 1860) | Scleralcyonacea | Coralliidae | 3 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Coralliidae Lamouroux, 1812 | Scleralcyonacea | Coralliidae | 4 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Cornularia cornucopiae (Pallas, 1766) | Scleralcyonacea | Cornulariidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Viminella flagellum (Johnson, 1863) | Scleralcyonacea | Ellisellidae | 8 | x | x | x | - | x |

| Acanella arbuscula (Johnson, 1862) | Scleralcyonacea | Keratoisididae | 5 | x | - | x | x | x |

| Calyptrophora trilepis (Pourtalès, 1868) | Scleralcyonacea | Primnoidae | 1 | x | - | x | - | x |

| Candidella imbricata (Johnson, 1862) | Scleralcyonacea | Primnoidae | 5 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Narella bellissima (Kükenthal, 1915) | Scleralcyonacea | Primnoidae | 4 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Narella versluysi (Hickson, 1909) | Scleralcyonacea | Primnoidae | 3 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Paracalyptrophora josephinae (Lindström, 1877) | Scleralcyonacea | Primnoidae | 4 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Primnoidae Milne Edwards, 1857 | Scleralcyonacea | Primnoidae | 3 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Thouarella (Euthouarella) grasshoffi Cairns, 2006 | Scleralcyonacea | Primnoidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Thouarella (Euthouarella) hilgendorfi (Studer, 1879) | Scleralcyonacea | Primnoidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Thouarella (Thouarella) variabilis Wright & Studer, 1889 | Scleralcyonacea | Primnoidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Thouarella Gray, 1870 | Scleralcyonacea | Primnoidae | 2 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Sarcodictyon catenatum Forbes in Johnston, 1847 | Scleralcyonacea | Sarcodictyonidae | 2 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Telestula batoni Weinberg, 1990 | Scleralcyonacea | Sarcodictyonidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Telestula kuekenthali Weinberg, 1990 | Scleralcyonacea | Sarcodictyonidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Telestula tubaria Wright & Studer, 1889 | Scleralcyonacea | Sarcodictyonidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Scleroptilum grandiflorum Kölliker, 1880 | Scleralcyonacea | Scleroptilidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Titanideum obscurum Thomson, 1927 | Scleralcyonacea | Spongiodermidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Paramuricea candida Grasshoff, 1977 | Malacalcyonacea | Acanthogorgiidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Paramuricea grayi (Johnson, 1861) | Malacalcyonacea | Acanthogorgiidae | 1 | - | x | - | - | - |

| Paramuricea Kölliker, 1865 | Malacalcyonacea | Acanthogorgiidae | 5 | x | - | x | x | x |

| Alcyoniidae Lamouroux, 1812 | Malacalcyonacea | Alcyoniidae | 3 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Alcyonium bocagei (Saville Kent, 1870) | Malacalcyonacea | Alcyoniidae | 2 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Alcyonium burmedju Sampaio, Stokvis & van Ofwegen, 2016 | Malacalcyonacea | Alcyoniidae | 2 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Alcyonium maristenebrosi (Stiasny, 1937) | Malacalcyonacea | Alcyoniidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Alcyonium palmatum Pallas, 1766 | Malacalcyonacea | Alcyoniidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Alcyonium profundum Stokvis & van Ofwegen, 2006 | Malacalcyonacea | Alcyoniidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Alcyonium Linnaeus, 1758 | Malacalcyonacea | Alcyoniidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Anthothela grandiflora (Sars, 1856) | Malacalcyonacea | Alcyoniidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Bellonella tenuis Tixier-Durivault & d’Hondt, 1974 | Malacalcyonacea | Alcyoniidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Bellonella variabilis (Studer, 1891) | Malacalcyonacea | Alcyoniidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Lateothela grandiflora (Tixier-Durivault & d’Hondt, 1974) | Malacalcyonacea | Alcyoniidae | 2 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Isididae Lamouroux, 1812 | Malacalcyonacea | Isididae | 2 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Paralcyonium spinulosum (Delle Chiaje, 1822) | Malacalcyonacea | Paralcyoniidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Swiftia dubia (Thomson, 1929) | Malacalcyonacea | Plexauridae | 2 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Swiftia Duchassaing & Michelotti, 1864 | Malacalcyonacea | Plexauridae | 2 | x | - | x | - | - |

| Pennatuloidea Ehrenberg, 1834 | Scleralcyonacea | 2 | x | - | - | - | x | |

| Anthoptilum Kölliker, 1880 | Scleralcyonacea | Anthoptilidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Iridogorgia fontinalis Watling, 2007 | Scleralcyonacea | Chrysogorgiidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Iridogorgia pourtalesii Verrill, 1883 | Scleralcyonacea | Chrysogorgiidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Iridogorgia Verrill, 1883 | Scleralcyonacea | Chrysogorgiidae | 2 | x | - | - | x | x |

| Metallogorgia melanotrichos (Wright & Studer, 1889) | Scleralcyonacea | Chrysogorgiidae | 2 | x | - | x | - | - |

| Metallogorgia Versluys, 1902 | Scleralcyonacea | Chrysogorgiidae | 1 | - | - | - | x | - |

| Corallium Cuvier, 1798 | Scleralcyonacea | Coralliidae | 2 | x | - | x | - | x |

| Hemicorallium niobe (Bayer, 1964) | Scleralcyonacea | Coralliidae | 3 | x | - | x | - | - |

| Hemicorallium tricolor (Johnson, 1899) | Scleralcyonacea | Coralliidae | 2 | x | - | x | - | - |

| Paragorgia arborea (Linnaeus, 1758) | Scleralcyonacea | Coralliidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Paragorgia johnsoni Gray, 1862 | Scleralcyonacea | Coralliidae | 4 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Anthomastus canariensis Wright & Studer, 1889 | Scleralcyonacea | Coralliidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Anthomastus grandiflorus Verrill, 1878 | Scleralcyonacea | Coralliidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Anthomastus Verrill, 1878 | Scleralcyonacea | Coralliidae | 4 | x | - | x | - | x |

| Pseudoanthomastus agaricus (Studer, 1890) | Scleralcyonacea | Coralliidae | 2 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Pseudoanthomastus Tixier-Durivault & d’Hondt, 1974 | Scleralcyonacea | Coralliidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Nicella granifera (Kölliker, 1865) | Scleralcyonacea | Ellisellidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Gyrophyllum hirondellei Studer, 1891 | Scleralcyonacea | Gyrophyllidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Isidella longiflora (Verrill, 1883) | Scleralcyonacea | Keratoisididae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Lepidisis cyanae Grasshoff, 1986 | Scleralcyonacea | Keratoisididae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Lepidisis Verrill, 1883 | Scleralcyonacea | Keratoisididae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Keratoisididae Gray, 1870 | Scleralcyonacea | Keratoisididae | 1 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Keratoisis grayi Wright, 1869 | Scleralcyonacea | Keratoisididae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Keratoisis Wright, 1869 | Scleralcyonacea | Keratoisididae | 3 | x | - | x | - | x |

| Pennatula Linnaeus, 1758 | Scleralcyonacea | Pennatulidae | 1 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Callogorgia verticillata (Pallas, 1766) | Scleralcyonacea | Primnoidae | 4 | x | - | x | - | x |

| Paracalyptrophora Kinoshita, 1908 | Scleralcyonacea | Primnoidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Umbellula Cuvier, [1797] | Scleralcyonacea | Umbellulidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Veretillum cynomorium (Pallas, 1766) | Scleralcyonacea | Veretillidae | 1 | - | x | - | - | - |

| Subphyllum Medusozoa | ||||||||

| Class Hydrozoa | ||||||||

| Hydrozoa | 1 | x | - | - | - | x | ||

| Candelabrum phrygium (Fabricius, 1780) | Anthoathecata | Candelabridae | 1 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Candelabrum serpentarii Segonzac & Vervoort, 1995 | Anthoathecata | Candelabridae | 1 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Eudendrium Ehrenberg, 1834 | Anthoathecata | Eudendriidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Pennaria disticha Goldfuss, 1820 | Anthoathecata | Pennariidae | 1 | - | x | - | - | - |

| Errina atlantica Hickson, 1912 | Anthoathecata | Stylasteridae | 2 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Errina dabneyi (Pourtalès, 1871) | Anthoathecata | Stylasteridae | 5 | x | - | x | - | x |

| Errina Gray, 1835 | Anthoathecata | Stylasteridae | 2 | x | x | - | - | x |

| Stenohelia Kent, 1870 | Anthoathecata | Stylasteridae | 2 | x | x | - | - | x |

| Stylaster Gray, 1831 | Anthoathecata | Stylasteridae | 1 | - | x | - | - | x |

| Stylasteridae Gray, 1847 | Anthoathecata | Stylasteridae | 5 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Pliobothrus symmetricus Pourtalès, 1868 | Anthoathecata | Stylasteridae | 2 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Crypthelia affinis Moseley, 1879 | Anthoathecata | Stylasteridae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Crypthelia medioatlantica Zibrowius & Cairns, 1992 | Anthoathecata | Stylasteridae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Crypthelia tenuiseptata Cairns, 1986 | Anthoathecata | Stylasteridae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Crypthelia vascomarquesi Zibrowius & Cairns, 1992 | Anthoathecata | Stylasteridae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Crypthelia Milne Edwards & Haime, 1849 | Anthoathecata | Stylasteridae | 2 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Lepidopora eburnea (Calvet, 1903) | Anthoathecata | Stylasteridae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Lepidopora Pourtalès, 1871 | Anthoathecata | Stylasteridae | 1 | - | x | - | - | x |

| Ectopleura crocea (Agassiz, 1862) | Anthoathecata | Tubulariidae | 1 | - | x | - | - | - |

| Macrorhynchia philippina Kirchenpauer, 1872 | Leptothecata | Aglaopheniidae | 2 | - | x | - | - | - |

| Macrorhynchia Kirchenpauer, 1872 | Leptothecata | Aglaopheniidae | 1 | - | x | - | - | - |

| Aglaophenia lophocarpa Allman, 1877 | Leptothecata | Aglaopheniidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Aglaophenia pluma (Linnaeus, 1758) | Leptothecata | Aglaopheniidae | 1 | - | x | - | - | - |

| Aglaophenia Lamouroux, 1812 | Leptothecata | Aglaopheniidae | 3 | x | x | x | - | x |

| Lytocarpia myriophyllum (Linnaeus, 1758) | Leptothecata | Aglaopheniidae | 5 | x | - | x | - | x |

| Obelia geniculata (Linnaeus, 1758) | Leptothecata | Campanulariidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Halecium Oken, 1815 | Leptothecata | Haleciidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Polyplumaria flabellata Sars, 1874 | Leptothecata | Halopterididae | 5 | x | - | x | - | x |

| Polyplumaria Sars, 1874 | Leptothecata | Halopterididae | 1 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Antennella secundaria (Gmelin, 1791) | Leptothecata | Halopterididae | 1 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Antennella Allman, 1877 | Leptothecata | Halopterididae | 1 | - | x | - | - | - |

| Kirchenpaueria halecioides (Alder, 1859) | Leptothecata | Kirchenpaueriidae | 1 | - | x | - | - | - |

| Filellum serratum (Clarke, 1879) | Leptothecata | Lafoeidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Grammaria abietina (Sars, 1851) | Leptothecata | Lafoeidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Acryptolaria conferta (Allman, 1877) | Leptothecata | Lafoeidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Acryptolaria crassicaulis (Allman, 1888) | Leptothecata | Lafoeidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Acryptolaria Norman, 1875 | Leptothecata | Lafoeidae | 1 | x | - | x | - | x |

| Nemertesia antennina (Linnaeus, 1758) | Leptothecata | Plumulariidae | 3 | x | - | x | - | x |

| Nemertesia ramosa (Lamarck, 1816) | Leptothecata | Plumulariidae | 1 | - | x | - | - | - |

| Nemertesia Lamouroux, 1812 | Leptothecata | Plumulariidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Plumulariidae McCrady, 1859 | Leptothecata | Plumulariidae | 1 | x | - | x | - | x |

| Sertularella gayi (Lamouroux, 1821) | Leptothecata | Sertularellidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Sertularella Gray, 1848 | Leptothecata | Sertularellidae | 1 | - | x | - | - | x |

| Diphasia alata (Hincks, 1855) | Leptothecata | Sertulariidae | 1 | x | - | x | - | x |

| Diphasia margareta (Hassall, 1841) | Leptothecata | Sertulariidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Diphasia Agassiz, 1862 | Leptothecata | Sertulariidae | 2 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Dynamena Lamouroux, 1812 | Leptothecata | Sertulariidae | 1 | - | x | - | - | - |

| Cryptolaria pectinata (Allman, 1888) | Leptothecata | Zygophylacidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Cryptolaria Busk, 1857 | Leptothecata | Zygophylacidae | 1 | x | - | x | - | x |

| Zygophylax biarmata Billard, 1905 | Leptothecata | Zygophylacidae | 1 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Phyllum Chlorophyta | ||||||||

| Subphyllum Chlorophytina | ||||||||

| Class Ulvophyceae | ||||||||

| Bryopsis J.V.Lamouroux, 1809 | Bryopsidales | Bryopsidaceae | 1 | - | x | - | - | - |

| Caulerpa cylindracea Sonder, 1845 | Bryopsidales | Caulerpaceae | 1 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Caulerpa mexicana Sonder ex Kützing, 1849 | Bryopsidales | Caulerpaceae | 1 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Caulerpa prolifera (Forsskål) J.V.Lamouroux, 1809 | Bryopsidales | Caulerpaceae | 7 | - | x | x | - | - |

| Caulerpa racemosa (Forsskål) J.Agardh, 1873 | Bryopsidales | Caulerpaceae | 1 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Caulerpa webbiana f. disticha Vickers, 1896 | Bryopsidales | Caulerpaceae | 1 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Caulerpa webbiana Montagne, 1837 | Bryopsidales | Caulerpaceae | 1 | - | x | - | - | - |

| Caulerpa J.V.Lamouroux, 1809 | Bryopsidales | Caulerpaceae | 4 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Codium adhaerens C.Agardh, 1822 | Bryopsidales | Codiaceae | 4 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Codium elisabethiae O.C.Schmidt, 1929 | Bryopsidales | Codiaceae | 2 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Codium fragile subsp. fragile (Suringar) Hariot, 1889 | Bryopsidales | Codiaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Codium fragile (Suringar) Hariot, 1889 | Bryopsidales | Codiaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Avrainvillea canariensis A.Gepp & E.S.Gepp, 1911 | Bryopsidales | Dichotomosiphonaceae | 1 | - | x | - | - | - |

| Halimeda incrassata (J.Ellis) J.V.Lamouroux, 1816 | Bryopsidales | Halimedaceae | 1 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Anadyomene stellata (Wulfen) C.Agardh, 1823 | Cladophorales | Anadyomenaceae | 1 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Microdictyon calodictyon (Montagne) Kützing, 1849 | Cladophorales | Anadyomenaceae | 1 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Microdictyon Decaisne, 1841 | Cladophorales | Anadyomenaceae | 1 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Cladophoropsis membranacea Bang ex C.Agardh) Børgesen, 1905 | Cladophorales | Boodleaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Chaetomorpha aerea (Dillwyn) Kützing, 1849 | Cladophorales | Cladophoraceae | 2 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Chaetomorpha pachynema (Montagne) Kützing, 1847 | Cladophorales | Cladophoraceae | 2 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Chaetomorpha Kützing, 1845 | Cladophorales | Cladophoraceae | 2 | x | - | x | - | - |

| Pseudorhizoclonium africanum (Kützing) Boedeker, 2016 | Cladophorales | Cladophoraceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Cladophora albida (Nees) Kutzing, 1843 | Cladophorales | Cladophoraceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Cladophora coelothrix Kützing, 1843 | Cladophorales | Cladophoraceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Cladophora prolifera (Roth) Kützing, 1843 | Cladophorales | Cladophoraceae | 3 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Cladophora Kützing, 1843 | Cladophorales | Cladophoraceae | 3 | x | - | x | - | - |

| Valonia utricularis (Roth) C.Agardh, 1823 | Cladophorales | Valoniaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Valonia C.Agardh, 1823 | Cladophorales | Valoniaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Cymopolia barbata (Linnaeus) J.V.Lamouroux, 1816 | Dasycladales | Dasycladaceae | 1 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Dasycladus vermicularis (Scopoli) Krasser, 1898 | Dasycladales | Dasycladaceae | 1 | - | x | - | - | - |

| Dasycladus C.Agardh, 1828 | Dasycladales | Dasycladaceae | 1 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Parvocaulis parvulus (Solms-Laubach) S.Berger, Fettweiss, Gleissberg, Liddle, U.Richter, Sawitzky & Zuccarello, 2003 | Dasycladales | Polyphysaceae | 2 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Blidingia minima (Nägeli ex Kützing) Kylin, 1947 | Ulvales | Kornmanniaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Blidingia Kylin, 1947 | Ulvales | Kornmanniaceae | 2 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Ulva clathrata (Roth) C.Agardh, 1811 | Ulvales | Ulvaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Ulva compressa Linnaeus, 1753 | Ulvales | Ulvaceae | 2 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Ulva intestinalis Linnaeus, 1753 | Ulvales | Ulvaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Ulva linza Linnaeus, 1753 | Ulvales | Ulvaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Ulva rigida C.Agardh, 1823 | Ulvales | Ulvaceae | 3 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Ulva torta (Mertens) Trevisan, 1842 | Ulvales | Ulvaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Ulva Linnaeus, 1753 | Ulvales | Ulvaceae | 3 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Ulvaceae J.V. Lamouroux ex Dumortier, 1822 | Ulvales | Ulvaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Class Chlorophyceae | ||||||||

| Pseudotetraspora marina Wille, 1906 | Chlamydomonadales | Palmellopsidaceae | 1 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Phyllum Rhodophyta | ||||||||

| Subphyllum Eurhodophytina | ||||||||

| Class Bangiophyceae | ||||||||

| Porphyra umbilicalis Kützing, 1843 | Bangiales | Bangiaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Porphyra C.Agardh, 1824 | Bangiales | Bangiaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Bangia atropurpurea (Mertens ex Roth) C.Agardh, 1824 | Bangiales | Bangiaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Class Florideophyceae | ||||||||

| Asparagopsis armata f. rufolanosa Harvey, 1856 | Bonnemaisoniales | Bonnemaisoniaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Asparagopsis armata Harvey, 1855 | Bonnemaisoniales | Bonnemaisoniaceae | 4 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Asparagopsis taxiformis (Delile) Trevisan de Saint-Léon, 1845 | Bonnemaisoniales | Bonnemaisoniaceae | 7 | x | x | x | - | - |

| Asparagopsis Montagne, 1840 | Bonnemaisoniales | Bonnemaisoniaceae | 4 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Ceramieales | Ceramiales | 1 | - | - | x | - | - | |

| Chondracanthus teedei (Mertens ex Roth) Kützing, 1843 | Ceramiales | Rhodomelaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Aglaothamnion Feldmann-Mazoyer, 1941 | Ceramiales | Callithamniaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Callithamnion corymbosum (Smith) Lyngbye, 1819 | Ceramiales | Callithamniaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Gaillona hookeri (Dillwyn) Athanasiadis, 2016 | Ceramiales | Callithamniaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Spyridia filamentosa (Wulfen) Harvey, 1833 | Ceramiales | Callithamniaceae | 2 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Spyridia hypnoides (Bory de Saint-Vincent) Papenfuss, 1968 | Ceramiales | Callithamniaceae | 1 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Antithamnion Nägeli, 1847 | Ceramiales | Ceramiaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Centroceras clavulatum (C.Agardh) Montagne, 1846 | Ceramiales | Ceramiaceae | 2 | x | - | x | - | - |

| Ceramieae (Dumortier) Schmitz, 1889 | Ceramiales | Ceramiaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Ceramium ciliatum (J.Ellis) Ducluzeau, 1806 | Ceramiales | Ceramiaceae | 2 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Ceramium diaphanum (Lightfoot) Roth, 1806 | Ceramiales | Ceramiaceae | 2 | x | - | x | - | - |

| Ceramium echionotum J.Agardh, 1844 | Ceramiales | Ceramiaceae | 2 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Ceramium gaditanum (Clemente) Cremades, 1990 | Ceramiales | Ceramiaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Ceramium virgatum Roth, 1797 | Ceramiales | Ceramiaceae | 2 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Ceramium Roth, 1797 | Ceramiales | Ceramiaceae | 2 | - | x | - | - | - |

| Gayliella mazoyerae T.O.Cho, Fredericq & Hommersand, 2008 | Ceramiales | Ceramiaceae | 1 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Stirkia codii (H.Richards) Barros-Barreto & Maggs, 2023 | Ceramiales | Ceramiaceae | 1 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Acrosorium venulosum (Zanardini) Kylin, 1924 | Ceramiales | Delesseriaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Acrosorium Zanardini ex Kützing, 1869 | Ceramiales | Delesseriaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Cottoniella filamentosa (M.A.Howe) Børgesen, 1920 | Ceramiales | Delesseriaceae | 3 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Dasya pedicellata (C.Agardh) C.Agardh, 1824 | Ceramiales | Delesseriaceae | 1 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Dasya C.Agardh, 1824 | Ceramiales | Delesseriaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Delesseriaceae Bory, 1828 | Ceramiales | Delesseriaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Hypoglossum hypoglossoides (Stackhouse) Collins & Hervey, 1917 | Ceramiales | Delesseriaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Chondria capillaris (Hudson) M.J.Wynne, 1991 | Ceramiales | Rhodomelaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Chondria coerulescens (J.Agardh) Sauvageau, 1897 | Ceramiales | Rhodomelaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Chondria dasyphylla (Woodward) C.Agardh, 1817 | Ceramiales | Rhodomelaceae | 2 | x | - | x | - | - |

| Chondria C.Agardh, 1817 | Ceramiales | Rhodomelaceae | 1 | - | x | - | - | - |

| Laurencia viridis Gil-Rodríguez & Haroun, 1992 | Ceramiales | Rhodomelaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Laurencia J.V.Lamouroux, 1813 | Ceramiales | Rhodomelaceae | 5 | x | - | x | - | - |

| Lophocladia trichoclados (C.Agardh) F.Schmitz, 1893 | Ceramiales | Rhodomelaceae | 2 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Lophosiphonia Falkenberg, 1897 | Ceramiales | Rhodomelaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Polysiphonia atlantica Kapraun & J.N.Norris, 1982 | Ceramiales | Rhodomelaceae | 2 | x | - | x | - | - |

| Polysiphonia flexella (C.Agardh) J.Agardh, 1842 | Ceramiales | Rhodomelaceae | 1 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Polysiphonia havanensis Montagne, 1837 | Ceramiales | Rhodomelaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Polysiphonia opaca (C.Agardh) Moris & De Notaris, 1839 | Ceramiales | Rhodomelaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Polysiphonia stricta (Mertens ex Dillwyn) Greville, 1824 | Ceramiales | Rhodomelaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Polysiphonia Greville, 1823 | Ceramiales | Rhodomelaceae | 4 | x | - | x | - | - |

| Symphyocladia marchantioides (Harvey) Falkenberg, 1897 | Ceramiales | Rhodomelaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Carradoriella denudata (Dillwyn) Savoie & G.W.Saunders, 2019 | Ceramiales | Rhodomelaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Halopithys incurva (Hudson) Batters, 1902 | Ceramiales | Rhodomelaceae | 1 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Herposiphonia secunda (C.Agardh) Ambronn, 1880 | Ceramiales | Rhodomelaceae | 1 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Herposiphonia Nägeli, 1846 | Ceramiales | Rhodomelaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Osmundea pinnatifida (Hudson) Stackhouse, 1809 | Ceramiales | Rhodomelaceae | 3 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Osmundea Stackhouse, 1809 | Ceramiales | Rhodomelaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Pterosiphonia Falkenberg, 1897 | Ceramiales | Rhodomelaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Vertebrata fucoides (Hudson) Kuntze, 1891 | Ceramiales | Rhodomelaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Vertebrata subulifera (C.Agardh) Kuntze, 1891 | Ceramiales | Rhodomelaceae | 1 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Vertebrata tripinnata (Harvey) Kuntze, 1891 | Ceramiales | Rhodomelaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Plumaria F.Schmitz, 1896 | Ceramiales | Wrangeliaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | x |

| Wrangelia penicillata (C.Agardh) C.Agardh, 1828 | Ceramiales | Wrangeliaceae | 1 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Bornetia Thuret, 1855 | Ceramiales | Wrangeliaceae | 1 | - | x | - | - | - |

| Articulated Corallinaceae | Corallinales | 3 | x | - | x | - | - | |

| Rhodolith | Corallinales | 4 | x | - | x | - | - | |

| Corallina officinalis Linnaeus, 1758 | Corallinales | Corallinaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Corallina Linnaeus, 1758 | Corallinales | Corallinaceae | 3 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Ellisolandia elongata (J.Ellis & Solander) K.R.Hind & G.W.Saunders, 2013 | Corallinales | Corallinaceae | 2 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Jania adhaerens J.V.Lamouroux, 1816 | Corallinales | Corallinaceae | 2 | x | - | x | - | - |

| Jania capillacea Harvey, 1853 | Corallinales | Corallinaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Jania longifurca Zanardini, 1844 | Corallinales | Corallinaceae | 2 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Jania rubens (Linnaeus) J.V.Lamouroux, 1816 | Corallinales | Corallinaceae | 3 | x | - | x | - | - |

| Jania virgata (Zanardini) Montagne, 1846 | Corallinales | Corallinaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Jania J.V.Lamouroux, 1812 | Corallinales | Corallinaceae | 5 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Lithophyllum crouaniorum Foslie, 1899 | Corallinales | Lithophyllaceae | 1 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Lithophyllum hibernicum Foslie, 1906 | Corallinales | Lithophyllaceae | 1 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Lithophyllum incrustans Philippi, 1837 | Corallinales | Lithophyllaceae | 4 | - | x | x | - | - |

| Lithophyllum Philippi, 1837 | Corallinales | Lithophyllaceae | 1 | - | x | - | - | - |

| Tenarea tortuosa (Esper) Me.Lemoine, 1910 | Corallinales | Lithophyllaceae | 2 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Amphiroa J.V.Lamouroux, 1812 | Corallinales | Lithophyllaceae | 1 | - | x | - | - | - |

| Neogoniolithon brassica-florida (Harvey) Setchell & L.R.Mason, 1943 | Corallinales | Spongitidaceae | 1 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Gelidiella Feldmann & G.Hamel, 1934 | Gelidiales | Gelidiellaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Gelidium microdon Kützing, 1849 | Gelidiales | Gelidiellaceae | 3 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Gelidium pusillum (Stackhouse) Le Jolis, 1863 | Gelidiales | Gelidiellaceae | 2 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Gelidium spinosum (S.G.Gmelin) P.C.Silva, 1996 | Gelidiales | Gelidiellaceae | 3 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Millerella pannosa (Feldmann) G.H.Boo & L.Le Gall, 2016 | Gelidiales | Gelidiellaceae | 1 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Pterocladiella capillacea (S.G.Gmelin) Santelices & Hommersand, 1997 | Gelidiales | Pterocladiaceae | 5 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Catenella caespitosa (Withering) L.M.Irvine, 1976 | Gigartinales | Caulacanthaceae | 2 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Caulacanthus ustulatus (Turner) Kützing, 1843 | Gigartinales | Caulacanthaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Calliblepharis Kützing, 1843 | Gigartinales | Cystocloniaceae | 1 | - | x | - | - | - |

| Hypnea musciformis (Wulfen) J.V.Lamouroux, 1813 | Gigartinales | Cystocloniaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Hypnea spinella (C.Agardh) Kützing, 1847 | Gigartinales | Cystocloniaceae | 1 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Hypnea J.V.Lamouroux, 1813 | Gigartinales | Cystocloniaceae | 1 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Dudresnaya P.L.Crouan & H.M.Crouan, 1835 | Gigartinales | Dumontiaceae | 1 | - | x | - | - | - |

| Halarachnion ligulatum (Woodward) Kützing, 1843 | Gigartinales | Furcellariaceae | 1 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Chondracanthus acicularis (Roth) Fredericq, 1993 | Gigartinales | Gigartinaceae | 3 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Gigartina pistillata (S.G.Gmelin) Stackhouse, 1809 | Gigartinales | Gigartinaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Callophyllis Kützing, 1843 | Gigartinales | Kallymeniaceae | 1 | - | x | - | - | - |

| Kallymenia reniformis (Turner) J.Agardh, 1842 | Gigartinales | Kallymeniaceae | 1 | - | x | - | - | - |

| Erythrodermis traillii (Holmes ex Batters) Guiry & Garbary, 1990 | Gigartinales | Phyllophoraceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Gymnogongrus griffithsiae (Turner) C.Martius, 1833 | Gigartinales | Phyllophoraceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Phyllophora gelidioides P.L.Crouan & H.M.Crouan ex Karsakoff, 1896 | Gigartinales | Phyllophoraceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Sphaerococcus coronopifolius Stackhouse, 1797 | Gigartinales | Sphaerococcaceae | 2 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Gracilaria Greville, 1830 | Gracilariales | Gracilariaceae | 2 | - | x | x | - | - |

| Dermocorynus dichotomus (J.Agardh) Gargiulo, M.Morabito & Manghisi, 2013 | Halymeniales | Grateloupiaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Lithothamnion corallioides (P.Crouan & H.Crouan) P.Crouan & H.Crouan, 1867 | Hapalidiales | Hapalidiaceae | 3 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Lithothamnion Heydrich, 1897 | Hapalidiales | Hapalidiaceae | 1 | - | x | - | - | - |

| Phymatolithon calcareum (Pallas) W.H.Adey & D.L.McKibbin ex Woelkering & L.M.Irvine, 1986 | Hapalidiales | Hapalidiaceae | 3 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Phymatolithon lusitanicum V.Peña, 2015 | Hapalidiales | Hapalidiaceae | 1 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Phymatolithon Foslie, 1898 | Hapalidiales | Hapalidiaceae | 1 | - | x | - | - | - |

| Mesophyllum lichenoides (J.Ellis) Me.Lemoine, 1928 | Hapalidiales | Mesophyllumaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Mesophyllum sphaericum V.Pena, Bárbara, W.H.Adey, Riosmena-Rodrigues & H.G.Choi, 2011 | Hapalidiales | Mesophyllumaceae | 1 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Mesophyllum Me.Lemoine, 1928 | Hapalidiales | Mesophyllumaceae | 1 | - | x | - | - | - |

| Hildenbrandia rubra (Sommerfelt) Meneghini, 1841 | Hildenbrandiales | Hildenbrandiaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Hildenbrandia Nardo, 1834 | Hildenbrandiales | Hildenbrandiaceae | 4 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Liagora J.V.Lamouroux, 1812 | Nemaliales | Liagoraceae | 1 | - | x | - | - | - |

| Nemalion elminthoides (Velley) Batters, 1902 | Nemaliales | Nemaliaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Scinaia Bivona-Bernardi, 1822 | Nemaliales | Scinaiaceae | 1 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Platoma Schousboe ex F.Schmitz, 1894 | Nemastomatales | Schizymeniaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Schizymenia dubyi (Chauvin ex Duby) J.Agardh, 1851 | Nemastomatales | Schizymeniaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Palmaria palmata (Linnaeus) F.Weber & D.Mohr, 1805 | Palmariales | Palmariaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Peyssonnelia rubra (Greville) J.Agardh, 1851 | Peyssonneliales | Peyssonneliaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Peyssonnelia Decaisne, 1841 | Peyssonneliales | Peyssonneliaceae | 4 | x | - | x | - | - |

| Plocamium cartilagineum (Linnaeus) P.S.Dixon, 1967 | Plocamiales | Plocamiaceae | 2 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Champia parvula (C.Agardh) Harvey, 1853 | Rhodymeniales | Champiaceae | 1 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Champia Desvaux, 1809 | Rhodymeniales | Champiaceae | 1 | - | x | - | - | - |

| Gastroclonium ovatum (Hudson) Papenfuss, 1944 | Rhodymeniales | Champiaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Gastroclonium reflexum (Chauvin) Kützing, 1849 | Rhodymeniales | Champiaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Lomentaria articulata (Hudson) Lyngbye, 1819 | Rhodymeniales | Lomentariaceae | 2 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Rhodymenia holmesii Ardissone, 1893 | Rhodymeniales | Rhodymeniaceae | 2 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Rhodymenia pseudopalmata (J.V.Lamouroux) P.C.Silva, 1952 | Rhodymeniales | Rhodymeniaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Phyllum Ochrophyta | ||||||||

| Class Dictyochophyceae | ||||||||

| Padina pavonica (Linnaeus) Thivy, 1960 | Dictyochales | Dictyochaceae | 10 | x | - | x | - | - |

| Padina Adanson, 1763 | Dictyochales | Dictyochaceae | 1 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Class Phaeophyceae | ||||||||

| Lobophora variegata (J.V.Lamouroux) Womersley ex E.C.Oliveira, 1977 | Dictyotales | Dictyotaceae | 4 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Lobophora J.Agardh, 1894 | Dictyotales | Dictyotaceae | 4 | - | x | x | - | - |

| Stypopodium zonale (J.V.Lamouroux) Papenfuss, 1940 | Dictyotales | Dictyotaceae | 1 | - | x | - | - | - |

| Canistrocarpus cervicornis (Kützing) De Paula & De Clerck, 2006 | Dictyotales | Dictyotaceae | 1 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Dictyopteris polypodioides (A.P.De Candolle) J.V.Lamouroux, 1809 | Dictyotales | Dictyotaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Dictyota bartayresiana J.V.Lamouroux, 1809 | Dictyotales | Dictyotaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Dictyota dichotoma (Hudson) J.V.Lamouroux, 1809 | Dictyotales | Dictyotaceae | 5 | x | - | x | - | - |

| Dictyota fasciola (Roth) J.V.Lamouroux, 1809 | Dictyotales | Dictyotaceae | 1 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Dictyota J.V.Lamouroux, 1809 | Dictyotales | Dictyotaceae | 12 | x | - | x | - | - |

| Zonaria tournefortii (J.V.Lamouroux) Montagne, 1846 | Dictyotales | Dictyotaceae | 6 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Leathesia marina (Lyngbye) Decaisne, 1842 | Ectocarpales | Chordariaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Hydroclathrus clathratus (C.Agardh) M.Howe, 1920 | Ectocarpales | Scytosiphonaceae | 3 | x | - | x | - | - |

| Colpomenia sinuosa (Mertens ex Roth) Derbès & Solier, 1851 | Ectocarpales | Scytosiphonaceae | 5 | x | - | x | - | - |

| Petalonia binghamiae (J.Agardh) K.L.Vinogradova, 1973 | Ectocarpales | Scytosiphonaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Fucus spiralis Linnaeus, 1753 | Fucales | Fucaceae | 3 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Gongolaria abies-marina (S.G.Gmelin) Kuntze 1891 | Fucales | Sargassaceae | 2 | x | - | x | - | - |

| Sargassum furcatum Kützing, 1843 | Fucales | Sargassaceae | 1 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Sargassum C.Agardh, 1820 | Fucales | Sargassaceae | 4 | x | - | x | - | - |

| Cystoseira C.Agardh, 1820 | Fucales | Sargassaceae | 2 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Ericaria selaginoides (Linnaeus) Molinari & Guiry, 2020 | Fucales | Sargassaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Treptacantha abies-marina (S.G.Gmelin) Kützing, 1843 | Fucales | Sargassaceae | 4 | x | - | x | - | - |

| Laminaria ochroleuca Bachelot de la Pylaie, 1824 | Laminariales | Laminariaceae | 4 | x | - | x | - | x |

| Nemoderma tingitanum Schousboe ex Bornet, 1892 | Nemodermatales | Nemodermataceae | 2 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Nemoderma Schousboe ex Bornet, 1892 | Nemodermatales | Nemodermataceae | 1 | - | x | - | - | - |

| Ralfsia Berkeley, 1843 | Ralfsiales | Ralfsiaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Cladostephus spongiosus (Hudson) C.Agardh, 1817 | Sphacelariales | Cladostephaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Sphacelaria Lyngbye, 1818 | Sphacelariales | Sphacelariaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Halopteris filicina (Grateloup) Kützing, 1843 | Sphacelariales | Stypocaulaceae | 9 | x | - | x | - | - |

| Halopteris scoparia (Linnaeus) Sauvageau, 1904 | Sphacelariales | Stypocaulaceae | 5 | x | - | x | - | - |

| Halopteris Kützing, 1843 | Sphacelariales | Stypocaulaceae | 3 | x | x | - | - | - |

| Sporochnus pedunculatus (Hudson) C.Agardh, 1817 | Sporochnales | Sporochnaceae | 2 | - | x | - | - | - |

| Carpomitra costata (Stackhouse) Batters, 1902 | Sporochnales | Sporochnaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Cutleria multifida (Turner) Greville, 1830 | Tilopteridales | Cutleriaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Phyllariopsis brevipes (C.Agardh) E.C.Henry & G.R.South, 1987 | Tilopteridales | Phyllariaceae | 1 | x | - | - | - | - |

| Phyllum Tracheophyta | ||||||||

| Subphyllum Spermatophytina | ||||||||

| Class Magnoliopsida | ||||||||

| Alismatales | Alismatales | 1 | - | - | x | - | - | |

| Cymodocea nodosa (Ucria) Ascherson, 1870 | Alismatales | Cymodoceaceae | 14 | - | x | x | - | - |

| Halodule wrightii Ascherson, 1868 | Alismatales | Cymodoceaceae | 1 | - | - | - | x | - |

| Halophila decipiens Ostenfeld, 1902 | Alismatales | Hydrocharitaceae | 1 | - | - | x | - | - |

| Ruppia maritima Linnaeus, 1753 | Alismatales | Ruppiaceae | 1 | - | - | - | x | - |

References

- Otero-Ferrer, F.; Tuya, F.; Bosch Guerra, N.E.; Herrero-Barrencua, A.; Abreu, A.D.; Haroun, R. Composition, Structure and Diversity of Fish Assemblages across Seascape Types at Príncipe, an Understudied Tropical Island in the Gulf of Guinea (Eastern Atlantic Ocean). Afr J Mar Sci 2020, 42, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuya, F.; Vanderklift, M.A.; Hyndes, G.A.; Wernberg, T.; Thomsen, M.S.; Hanson, C. Proximity to Rocky Reefs Alters the Balance between Positive and Negative Effects on Seagrass Fauna. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 2010, 405, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosme De Esteban, M.; Haroun, R.; Tuya, F.; Abreu, A.D.; Otero-Ferrer, F. Mapping Marine Habitats in the Gulf of Guinea: A Contribution to the Future Establishment of Marine Protected Areas in Principe Island. Reg Stud Mar Sci 2023, 57, 102742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, E.; Fernandez, M.; Gil, A.; Yesson, C.; Prestes, A.; Moreu-Badia, I.; Neto, A.; Arbelo, M. Macroalgae Niche Modelling: A Two-Step Approach Using Remote Sensing and in Situ Observations of a Native and an Invasive Asparagopsis. Biol Invasions 2021, 23, 3215–3230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filbee-Dexter, K.; Wernberg, T.; Barreiro, R.; Coleman, M.A.; Bettignies, T.; Feehan, C.J.; Franco, J.N.; Hasler, B.; Louro, I.; Norderhaug, K.M.; et al. Leveraging the Blue Economy to Transform Marine Forest Restoration. J Phycol 2022, 58, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, N.; Peña, V.; Salazar, V.W.; Horta, P.A.; Neves, P.; Ribeiro, C.; Otero-Ferrer, F.; Tuya, F.; Espino, F.; Schoenrock, K.; et al. Rhodolith Physiology Across the Atlantic: Towards a Better Mechanistic Understanding of Intra- and Interspecific Differences. Front Mar Sci 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhl-Mortensen, P.; Buhl-Mortensen, L.; Purser, A. Trophic Ecology and Habitat Provision in Cold-Water Coral Ecosystems. In Marine Animal Forests; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2016; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Govenar, B.; Fisher, C.R. Experimental Evidence of Habitat Provision by Aggregations of Riftia Pachyptila at Hydrothermal Vents on the East Pacific Rise. The Authors. Journal compilation a 2007, 28, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, L.; Gaulton, R.; Gerard, F.; Staley, J.T. The Influence of Hedgerow Structural Condition on Wildlife Habitat Provision in Farmed Landscapes. Biol Conserv 2018, 220, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, P.; Nielsen, M.M.; McLaverty, C.; Kristensen, K.; Geitner, K.; Olsen, J.; Saurel, C.; Petersen, J.K. Management of Bivalve Fisheries in Marine Protected Areas. Mar Policy 2021, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, N.; Bennett, N.J.; Le Billon, P.; Green, S.J.; Cisneros-Montemayor, A.M.; Amongin, S.; Gray, N.J.; Sumaila, U.R. Oil, Fisheries and Coastal Communities: A Review of Impacts on the Environment, Livelihoods, Space and Governance. Energy Res Soc Sci 2021, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breen, C.; El Safadi, C.; Huigens, H.; Tews, S.; Westley, K.; Anderou, G.; Vazquez, R.O.; Nikolaus, J.; Blue, L. Integrating Cultural and Natural Heritage Approaches to Marine Protected Areas in the MENA Region. Mar Policy 2021, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattam, C.; Broszeit, S.; Langmead, O.; Praptiwi, R.A.; Lim, V.C.; Creencia, L.A.; Tran, D.H.; Maharja, C.; Mitra Setia, T.; Wulandari, P.; et al. A Matrix Approach to Tropical Marine Ecosystem Service Assessments in South East Asia. Ecosyst Serv 2021, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero-Ferrer, F.; Cosme, M.; Tuya, F.; Espino, F.; Haroun, R. Effect of Depth and Seasonality on the Functioning of Rhodolith Seabeds. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 2020, 235, 106579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero-Ferrer, F.; Mannarà, E.; Cosme De Esteban, M.; Falace, A.; Montiel-Nelson, J.A.; Espino, F.; Haroun, R.; Tuya, F. Early-Faunal Colonization Patterns of Discrete Habitat Units: A Case Study with Rhodolith-Associated Vagile Macrofauna. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 2019, 218, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Peris, I.; Navarro-Mayoral, S.; de Esteban, M.C.; Tuya, F.; Pena, V.; Barbara, I.; Neves, P.; Ribeiro, C.; Abreu, A.; Grall, J.; et al. Effect of Depth across a Latitudinal Gradient in the Structure of Rhodolith Seabeds and Associated Biota across the Eastern Atlantic Ocean. DIVERSITY-BASEL 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.G.; Lawton, J.H.; Shachak, M. Organisms as Ecosystem Engineers. Oikos 1994, 69, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreiro, N.; Feijoó, C.; Giorgi, A.; Rosso, J. Macroinvertebrates Select Complex Macrophytes Independently of Their Body Size and Fish Predation Risk in a Pampean Stream. Hydrobiologia 2014, 740, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cúrdia, J.; Carvalho, S.; Pereira, F.; Guerra-García, J.M.; Santos, M.N.; Cunha, M.R. Diversity and Abundance of Invertebrate Epifaunal Assemblages Associated with Gorgonians Are Driven by Colony Attributes. Coral Reefs 2015, 34, 611–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacabelos, E.; Martins, G.M.; Thompson, R.; Prestes, A.C.L.; Azevedo, J.M.N.; Neto, A.I. Material Type and Roughness Influence Structure of Inter-tidal Communities on Coastal Defenses. Marine Ecology 2016, 37, 801–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, L.R.S.; Loiola, M.; Barros, F. Manipulating Habitat Complexity to Understand Its Influence on Benthic Macrofauna. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 2017, 489, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matias, M.G.; Underwood, A.J.; Hochuli, D.F.; Coleman, R.A. Independent Effects of Patch Size and Structural Complexity on Diversity of Benthic Macroinvertebrates. Ecology 2010, 91, 1908–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pianka, E.R. Evolutionary Ecology, 6th ed.; Benjamin Cummings: San Francisco, California, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Yanovski, R.; Nelson, P.A.; Abelson, A. Structural Complexity in Coral Reefs: Examination of a Novel Evaluation Tool on Different Spatial Scales. Front Ecol Evol 2017, 5, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trégarot, E.; D’Olivo, J.P.; Botelho, A.Z.; Cabrito, A.; Cardoso, G.O.; Casal, G.; Cornet, C.C.; Cragg, S.M.; Degia, A.K.; Fredriksen, S.; et al. Effects of Climate Change on Marine Coastal Ecosystems – A Review to Guide Research and Management. Biol Conserv 2024, 289, 110394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundersen, H. (NIVA); Bryan, T. (GRID-A.; Chen, W. (NIVA); Moy, F.E. (IMR); Sandman, A.N. (AquaBiota); Sundblad, G. (AquaBiota); Schneider, S. (NIVA); Andersen, J.H. (NIVA); Langaas, S. (NIVA); Walday, M.G. (NIVA) Ecosystem Services; Nordic Council of Ministers, 2017; ISBN 978-9-28934-7-488.

- Hemminga, M.A.; Duarte, C.M. Seagrass Ecology; Cambridge University Press, 2000; ISBN 9780521661843.

- Boström, C.; Baden, S.; Bockelmann, A.; Dromph, K.; Fredriksen, S.; Gustafsson, C.; Krause-Jensen, D.; Möller, T.; Nielsen, S.L.; Olesen, B.; et al. Distribution, Structure and Function of Nordic Eelgrass (Zostera Marina) Ecosystems: Implications for Coastal Management and Conservation. Aquat Conserv 2014, 24, 410–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahnke, M.; Christensen, A.; Micu, D.; Milchakova, N.; Sezgin, M.; Todorova, V.; Strungaru, S.; Procaccini, G. Patterns and Mechanisms of Dispersal in a Keystone Seagrass Species. Mar Environ Res 2016, 117, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekkby, T.; Papadopoulou, N.; Fiorentino, D.; McOwen, C.J.; Rinde, E.; Boström, C.; Carreiro-Silva, M.; Linares, C.; Andersen, G.S.; Bengil, E.G.T.; et al. Habitat Features and Their Influence on the Restoration Potential of Marine Habitats in Europe. Front Mar Sci 2020, 7, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smale, D.A.; Burrows, M.T.; Moore, P.; O’Connor, N.; Hawkins, S.J. Threats and Knowledge Gaps for Ecosystem Services Provided by Kelp Forests: A Northeast Atlantic Perspective. Ecol Evol 2013, 3, 4016–4038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filbee-Dexter, K.; Wernberg, T. Rise of Turfs: A New Battlefront for Globally Declining Kelp Forests. Bioscience 2018, 68, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steller, D.L.; Riosmena-Rodríguez, R.; Foster, M.S.; Roberts, C.A. Rhodolith Bed Diversity in the Gulf of California: The Importance of Rhodolith Structure and Consequences of Disturbance. Aquat Conserv 2003, 13, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, M.S.; Wernberg, T.; Altieri, A.; Tuya, F.; Gulbransen, D.; Mcglathery, K.J.; Holmer, M.; Silliman, B.R. Habitat Cascades: The Conceptual Context and Global Relevance of Facilitation Cascades via Habitat Formation and Modification. Integr Comp Biol 2010, 50, 158–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Figueiredo, M.A.O.; Santos de Menezes, K.; Costa-Paiva, E.M.; Paiva, P.C.; Ventura, C.R.R. Evaluacion Experimental de Rodolitos Como Sustratos Vivos Para La Infauna En El Banco de Abrolhos, Brasil. Cienc Mar 2007, 33, 427–440. [Google Scholar]

- Nordlund, L.M.; Unsworth, R.K.F.; Wallner-Hahn, S.; Ratnarajah, L.; Beca-Carretero, P.; Boikova, E.; Bull, J.C.; Chefaoui, R.M.; de los Santos, C.B.; Gagnon, K.; et al. One Hundred Priority Questions for Advancing Seagrass Conservation in Europe. PLANTS, PEOPLE, PLANET 2024, 6, 587–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mtwana Nordlund, L.; Koch, E.W.; Barbier, E.B.; Creed, J.C. Seagrass Ecosystem Services and Their Variability across Genera and Geographical Regions. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0163091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagne, C.S.; Salles, J.-M.; Boissery, P.; Deter, J. The Seagrass Posidonia Oceanica : Ecosystem Services Identification and Economic Evaluation of Goods and Benefits. Mar Pollut Bull 2015, 97, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, C.; Ormond, R. Habitat Complexity and Coral Reef Fish Diversity and Abundance on Red Sea Fringing Reefs. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 1987, 41, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.M.; Wheeler, A.; Freiwald, A.; Cairns, S. Cold-Water Corals: The Biology and Geology of Deep-Sea Coral Habitats; Cambridge University Press, 2009; ISBN 9780521884853.

- Berke, S.K. Functional Groups of Ecosystem Engineers: A Proposed Classification with Comments on Current Issues. Integr Comp Biol 2010, 50, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tissot, B.N.; Yoklavich, M.M.; Love, M.S.; York, K.; Amend, M. Benthic Invertebrates That Form Habitat on Deep Banks off Southern California, with Special Reference to Deep Sea Coral. Fishery Bulletin 2006, 104, 167–181. [Google Scholar]

- Herler, J. Microhabitats and Ecomorphology of Coral- and Coral Rock-Associated Gobiid Fish (Teleostei: Gobiidae) in the Northern Red Sea. Marine Ecology 2007, 28, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosme De Esteban, M.; Otero Ferrer, F.; Haroun, R. Los Fondos de Rodolitos: El Valor Oculto de Los Ecosistemas Marinos. Okeanos 2020, 10, 26–35. [Google Scholar]

- Buhl-Mortensen, L.; Buhl-Mortensen, P.; Dolan, M.J.F.; Gonzalez-Mirelis, G. Habitat Mapping as a Tool for Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Resources: Some Perspectives from the MAREANO Programme, Norway. J Sea Res 2015, 100, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czechowska, K.; Feldens, P.; Tuya, F.; Cosme de Esteban, M.; Espino, F.; Haroun, R.; Schönke, M.; Otero-Ferrer, F. Testing Side-Scan Sonar and Multibeam Echosounder to Study Black Coral Gardens: A Case Study from Macaronesia. Remote Sens (Basel) 2020, 12, 3244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, M.J.; Hilborn, R.; Jennings, S.; Amaroso, R.; Andersen, M.; Balliet, K.; Barratt, E.; Bergstad, O.A.; Bishop, S.; Bostrom, J.L.; et al. Prioritization of Knowledge-Needs to Achieve Best Practices for Bottom Trawling in Relation to Seabed Habitats. Fish and Fisheries 2016, 17, 637–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Reijden, K.J.; Govers, L.L.; Koop, L.; Damveld, J.H.; Herman, P.M.J.; Mestdagh, S.; Piet, G.; Rijnsdorp, A.D.; Dinesen, G.E.; Snellen, M.; et al. Beyond Connecting the Dots: A Multi-Scale, Multi-Resolution Approach to Marine Habitat Mapping. Ecol Indic 2021, 128, 107849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, H.M.; McLeod, K.L. Confronting the Challenges of Implementing Marine Ecosystem-Based Management. Front Ecol Environ 2007, 5, 540–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, K.; Oxenford, H.A. A Participatory Approach to Marine Habitat Mapping in the Grenadine Islands. Coastal Management 2014, 42, 36–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cogan, C.B.; Todd, B.J.; Lawton, P.; Noji, T.T. The Role of Marine Habitat Mapping in Ecosystem-Based Management. ICES Journal of Marine Science 2009, 66, 2033–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Young, C.; Charles, A.; Hjort, A. Human Dimensions of the Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries: An Overview of Context, Concepts, Tools and Methods. FAO Fisheries Technical Paper 2008, 489, 152. [Google Scholar]