Submitted:

30 April 2025

Posted:

30 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

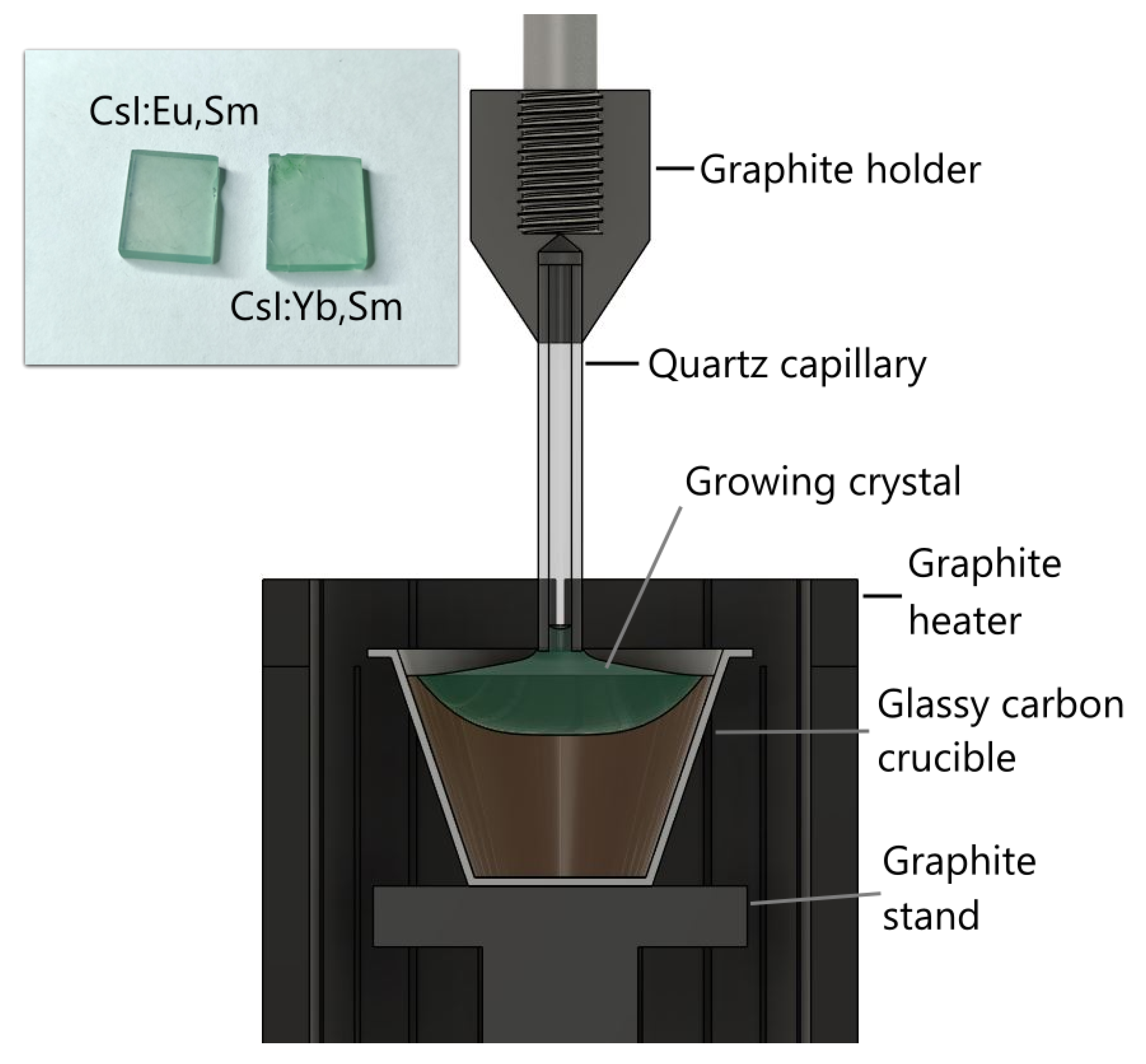

2. Materials and Methods

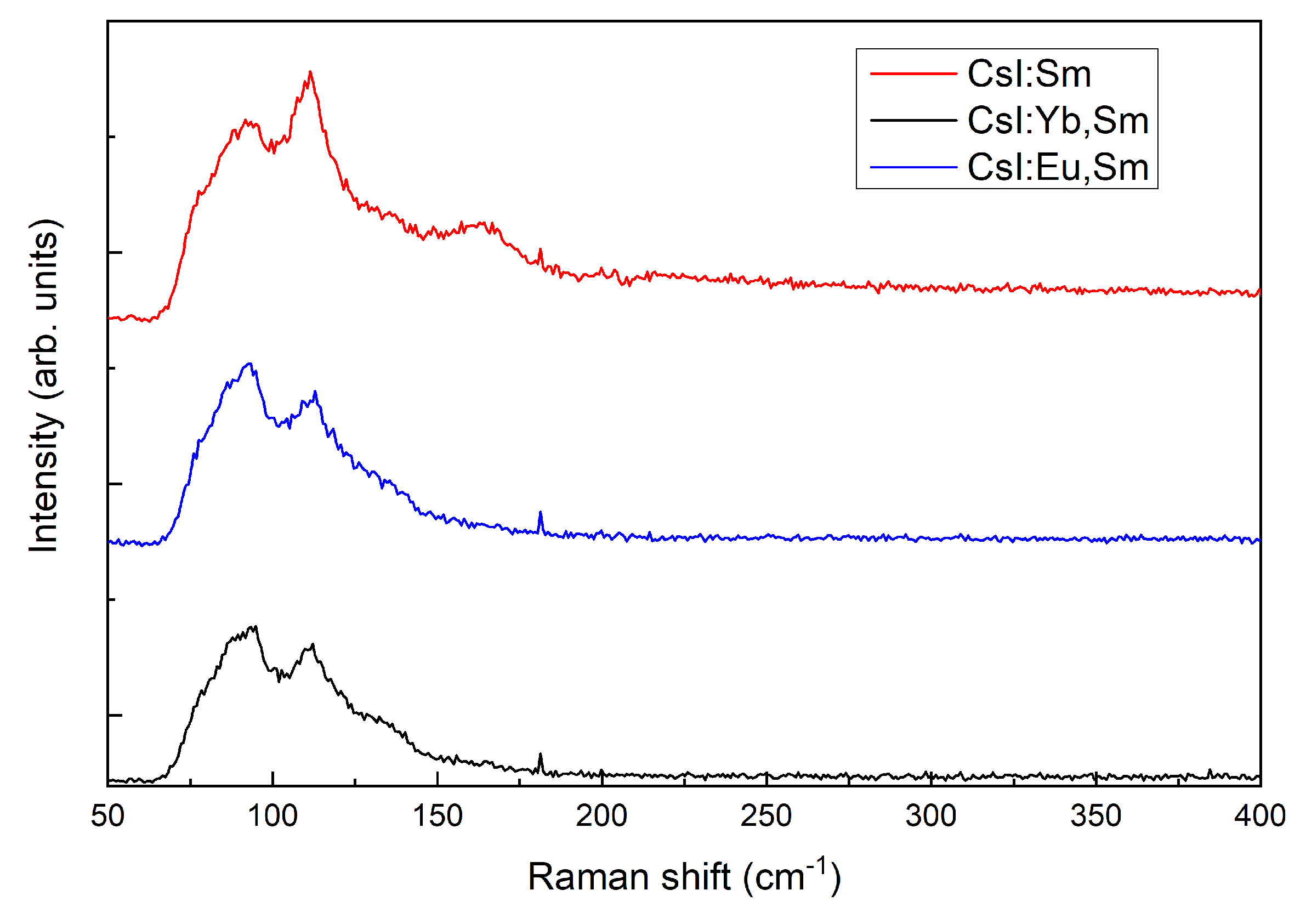

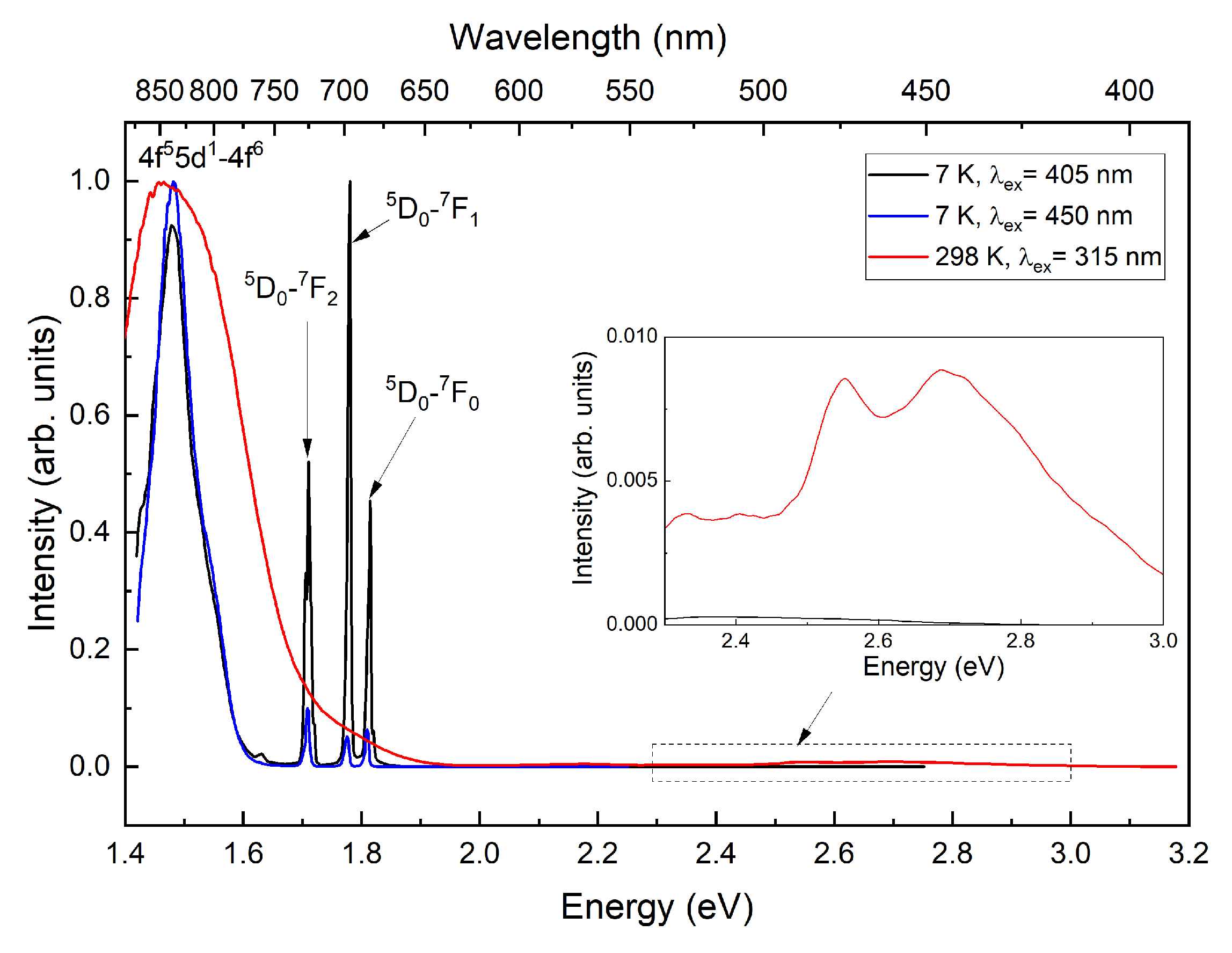

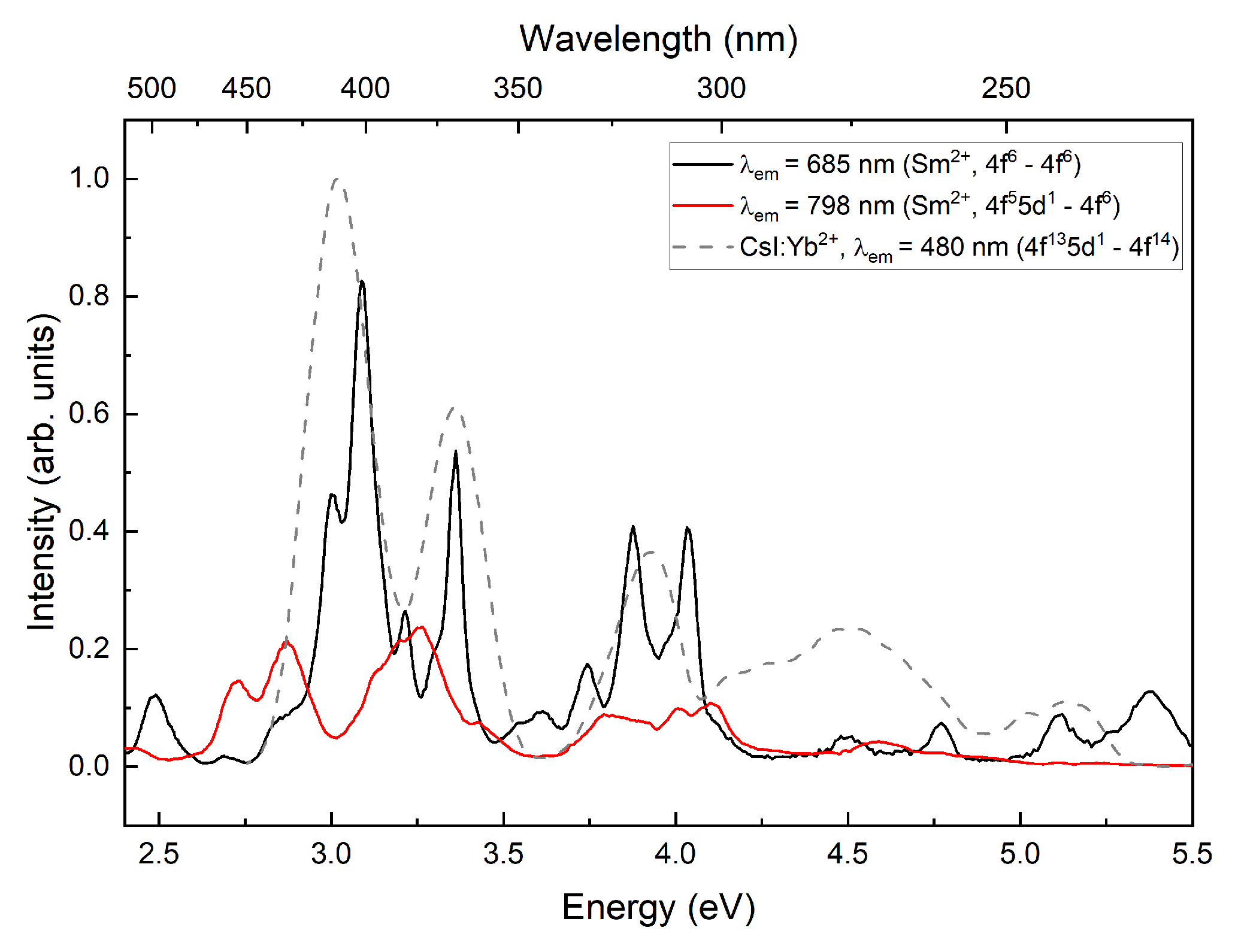

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NIR | Near-Infrared Light |

| VUV | Vacuum ultraviolet |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| STE | Self-trapped exciton |

References

- Kim, J.; Park, J.; Park, B.; Kim, Y.; Park, B.; Park, S.H. Compact and Real-Time Radiation Dosimeter Using Silicon Photomultipliers for In Vivo Dosimetry in Radiation Therapy. Sensors 2025, 25, 857. [CrossRef]

- Strigari, L.; Marconi, R.; Solfaroli-Camillocci, E. Evolution of Portable Sensors for In-Vivo Dose and Time-Activity Curve Monitoring as Tools for Personalized Dosimetry in Molecular Radiotherapy. Sensors 2023, 23, 2599. [CrossRef]

- Kodama, S.; Kurosawa, S.; Morishita, Y.; Usami, H.; Torii, T.; Hayashi, M.; Sasano, M.; Azuma, T.; Tanaka, H.; Kochurikhin, V.; et al. Growth and Scintillation Properties of a New Red-Emitting Scintillator Rb2HfI6 for the Fiber-Reading Radiation Monitor. IEEE Transactions on Nuclear Science 2020, 67, 1055–1062. [CrossRef]

- Bartram, R.H.; Kappers, L.A.; Hamilton, D.S.; Brecher, C.; Ovechkina, E.E.; Miller, S.R.; Nagarkar, V.V. Multiple Thermoluminescence Glow Peaks and Afterglow Suppression in CsI:Tl Co-Doped with Eu2+ or Yb2+. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 2015, 80, 012003. [CrossRef]

- van Aarle, C.; Krämer, K.W.; Dorenbos, P. Lengthening of the Sm2+ 4f55d → 4f6 Decay Time through Interplay with the 4f6[5D0] Level and Its Analogy to Eu2+ and Pr3+. Journal of Luminescence 2024, 266, 120329. [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Kucerkova, R.; Babin, V.; Prusa, P.; Kotykova, M.; Nikl, M.; Li, W.; Wang, Q.; Kurosawa, S.; Wu, Y. Scintillator-Oriented near-Infrared Emitting Cs4SrI6:Yb2+, Sm2+ Single Crystals via Sensitization Strategy. Journal of the American Ceramic Society 2023, 106, 6762–6768. [CrossRef]

- Alekhin, M.S.; Awater, R.H.P.; Biner, D.A.; Krämer, K.W.; de Haas, J.T.M.; Dorenbos, P. Luminescence and Spectroscopic Properties of Sm2+ and Er3+ Doped SrI2. Journal of Luminescence 2015, 167, 347–351. [CrossRef]

- Dixie, L.C.; Edgar, A.; Bartle, M.C. Spectroscopic and Radioluminescence Properties of Two Bright X-ray Phosphors: Strontium Barium Chloride Doped with Eu2+ or Sm2+ Ions. Journal of Luminescence 2014, 149, 91–98. [CrossRef]

- Wolszczak, W.; Krämer, K.W.; Dorenbos, P. CsBa2I5:Eu2+,Sm2+—The First High-Energy Resolution Black Scintillator for γ-Ray Spectroscopy. physica status solidi (RRL) – Rapid Research Letters 2019, 13, 1900158. [CrossRef]

- Wolszczak, W.; Krämer, K.W.; Dorenbos, P. Engineering Near-Infrared Emitting Scintillators with Efficient Eu2+ → Sm2+ Energy Transfer. Journal of Luminescence 2020, 222, 117101. [CrossRef]

- van Aarle, C.; Krämer, K.W.; Dorenbos, P. The Role of Yb2+ as a Scintillation Sensitiser in the Near-Infrared Scintillator CsBa2I5:Sm2+. Journal of Luminescence 2021, 238, 118257. [CrossRef]

- Awater, R.H.P.; Alekhin, M.S.; Biner, D.A.; Krämer, K.W.; Dorenbos, P. Converting SrI2:Eu2+ into a near Infrared Scintillator by Sm2+ Co-Doping. Journal of Luminescence 2019, 212, 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Sofich, D.; Myasnikova, A.; Bogdanov, A.; Pankratova, V.; Pankratov, V.; Kaneva, E.; Shendrik, R. Crystal Growth and Spectroscopy of Yb2+-Doped CsI Single Crystal. Crystals 2024, 14, 500. [CrossRef]

- Sofich, D.O.; Bogdanov, A.I.; Shendrik, R.Y. Spectroscopic and Vibrational Properties of CsI Single Crystals Doped with Divalent Samarium. Optical Materials 2025, 162, 116958. [CrossRef]

- Gektin, A.; Shiran, N.; Belsky, A.; Vasyukov, S. Luminescence Properties of CsI:Eu Crystals. Optical Materials 2012, 34, 2017–2020. [CrossRef]

- Pankratova, V.; Kozlova, A.P.; Buzanov, O.A.; Chernenko, K.; Shendrik, R.; Šarakovskis, A.; Pankratov, V. Time-Resolved Luminescence and Excitation Spectroscopy of Co-Doped Gd3Ga3Al2O12 Scintillating Crystals. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 20388. [CrossRef]

- Pankratov, V.; Kotlov, A. Luminescence Spectroscopy under Synchrotron Radiation: From SUPERLUMI to FINESTLUMI. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section B: Beam Interactions with Materials and Atoms 2020, 474, 35–40. [CrossRef]

- Chernenko, K.; Kivimäki, A.; Pärna, R.; Wang, W.; Sankari, R.; Leandersson, M.; Tarawneh, H.; Pankratov, V.; Kook, M.; Kukk, E.; et al. Performance and Characterization of the FinEstBeAMS Beamline at the MAX IV Laboratory. Journal of Synchrotron Radiation 2021, 28, 1620–1630. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Betancourtt, V.M.; Nattland, D. Raman Spectroscopic Study of Mixed Valence Neodymium and Cerium Chloride Solutions in Eutectic LiCl–KCl Melts. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2005, 7, 173–179. [CrossRef]

- Radzhabov, E.A. Spectroscopy of Divalent Samarium in Alkaline-Earth Fluorides. Optical Materials 2018, 85, 127–132. [CrossRef]

- Suta, M.; Urland, W.; Daul, C.; Wickleder, C. Photoluminescence Properties of Yb2+ Ions Doped in the Perovskites CsCaX3 and CsSrX3 (X = Cl, Br, and I) – a Comparative Study. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2016, 18, 13196–13208. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, P.; Cao, Z.; Chen, Y.; Yin, M. Investigation of the Temperature Characteristic in SrB4O7:Sm2+ Phosphor-in-Glass by Analyzing the Lifetime of 684 Nm. Journal of Rare Earths 2017, 35, 783–786. [CrossRef]

- Guzzi, M.; Baldini, G. Luminescence and Energy Levels of Sm2+ in Alkali Halides. Journal of Luminescence 1973, 6, 270–284. [CrossRef]

- Shiran, N.; Gektin, A.; Boyarintseva, Y.; Vasyukov, S.; Boyarintsev, A.; Pedash, V.; Tkachenko, S.; Zelenskaya, O.; Zosim, D. Modification of NaI Crystal Scintillation Properties by Eu-doping. Optical Materials 2010, 32, 1345–1348. [CrossRef]

- Shendrik, R.; Radzhabov, E. Absolute Light Yield Measurements on SrF2 and BaF2 Doped With Rare Earth Ions. IEEE Transactions on Nuclear Science 2014, 61, 406–410. [CrossRef]

- Ucer, K.B.; Bizarri, G.; Burger, A.; Gektin, A.; Trefilova, L.; Williams, R.T. Electron Thermalization and Trapping Rates in Pure and Doped Alkali and Alkaline-Earth Iodide Crystals Studied by Picosecond Optical Absorption. Physical Review B 2014, 89, 165112. [CrossRef]

- Shendrik, R.; Radzhabov, E. Energy Transfer Mechanism in Pr-Doped SrF2 Crystals. IEEE Transactions on Nuclear Science 2012, 59, 2089–2094. [CrossRef]

- Khanin, V.; Venevtsev, I.; Chernenko, K.; Pankratov, V.; Klementiev, K.; van Swieten, T.; van Bunningen, A.J.; Vrubel, I.; Shendrik, R.; Ronda, C.; et al. Exciton Interaction with Ce3+ and Ce4+ Ions in (LuGd)3(Ga,Al)5O12 Ceramics. Journal of Luminescence 2021, 237, 118150. [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Gridin, S.; Ucer, K.B.; Williams, R.T.; Del Ben, M.; Canning, A.; Moretti, F.; Bourret, E. Picosecond Absorption Spectroscopy of Excited States in BaBrCl with and without Eu Dopant and Au Codopant. Physical Review Applied 2019, 12, 014035. [CrossRef]

- Gektin, A.; Shiran, N.; Vasyukov, S.; Belsky, A.; Sofronov, D. Europium Emission Centers in CsI:Eu Crystal. Optical Materials 2013, 35, 2613–2617. [CrossRef]

- Yakovlev, V.; Trefilova, L.; Karnaukhova, A.; Ovcharenko, N. Energy Transfer Mechanism in CsI:Eu Crystal. Journal of Luminescence 2014, 148, 274–276. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, O.L.; Bates, C.W. Excitonic Emission from CsI(Na). Physical Review B 1977, 15, 5821–5833. [CrossRef]

- Yakovlev, V.; Trefilova, L.; Meleshko, A.; Ovcharenko, N. Luminescence of Eu2+–Vc- Dipoles and Their Associates in CsI:Eu Crystals. Journal of Luminescence 2012, 132, 2476–2478. [CrossRef]

- Lushchik, Ch.; Lushchik, A. Evolution of Anion and Cation Excitons in Alkali Halide Crystals. Physics of the Solid State 2018, 60, 1487–1505. [CrossRef]

- Shalaev, A.A.; Shendrik, R.; Myasnikova, A.S.; Bogdanov, A.; Rusakov, A.; Vasilkovskyi, A. Luminescence of BaBrI and SrBrI Single Crystals Doped with Eu2+. Optical Materials 2018, 79, 84–89. [CrossRef]

- Lushchik, A.; Feldbach, E.; Kink, R.; Lushchik, Ch.; Kirm, M.; Martinson, I. Secondary Excitons in Alkali Halide Crystals. Physical Review B 1996, 53, 5379–5387. [CrossRef]

- Sisodiya, D.S.; Singh, S.G.; Chandrakumar, K.R.S.; Patra, G.D.; Ghosh, M.; Pitale, S.; Sen, S. Optimizing the Scintillation Kinetics of CsI Scintillator Single Crystals by Divalent Cation Doping: Insights from Electronic Structure Analysis and Luminescence Studies. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2024, 128, 197–209. [CrossRef]

- Brecher, C.; Lempicki, A.; Miller, S.R.; Glodo, J.; Ovechkina, E.E.; Gaysinskiy, V.; Nagarkar, V.V.; Bartram, R.H. Suppression of Afterglow in CsI:Tl by Codoping with Eu2+—I: Experimental. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 2006, 558, 450–457. [CrossRef]

- Bartram, R.H.; Kappers, L.A.; Hamilton, D.S.; Lempicki, A.; Brecher, C.; Glodo, J.; Gaysinskiy, V.; Ovechkina, E.E. Suppression of Afterglow in CsI:Tl by Codoping with Eu2+—II: Theoretical Model. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 2006, 558, 458–467. [CrossRef]

- Shahmaleki, S.; Rahmani, F. Scintillation Properties of CsI(Tl) Co-Doped with Tm2+. Radiation Physics and Engineering 2021, 2, 13–19. [CrossRef]

- Takase, S.; Miyazaki, K.; Nakauchi, D.; Kato, T.; Kawaguchi, N.; Yanagida, T. Development of Nd-doped CsI Single Crystal Scintillators Emitting near-Infrared Light. Journal of Luminescence 2024, 267, 120400. [CrossRef]

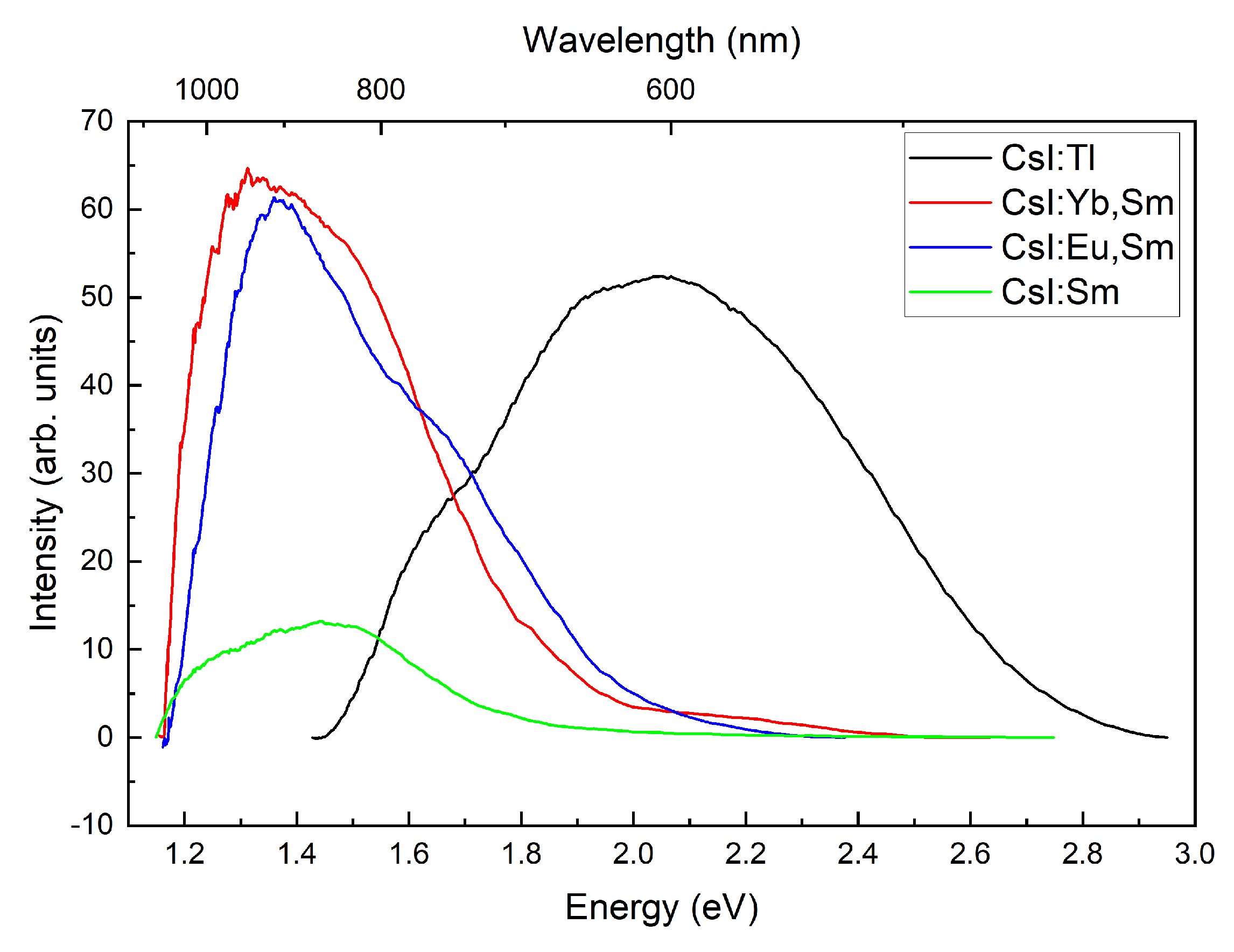

| Sample | Light yield relative to standard (%) | Light yield (photons/MeV) |

|---|---|---|

| CsI:Tl | 100 | 54000[25] |

| CsI:Yb,Sm | 68 | 36720 |

| CsI:Eu,Sm | 74 | 39960 |

| CsI:Sm | 14 | 7560 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).