1. Introduction

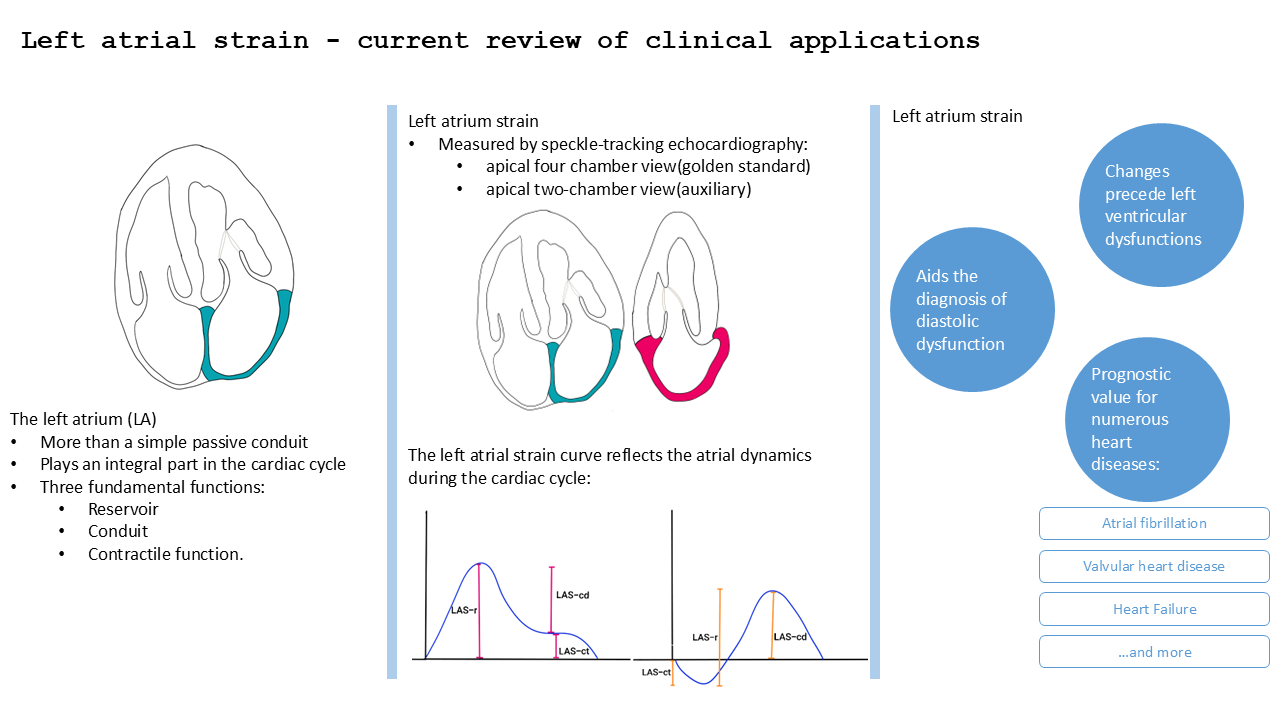

The left atrium (LA) is more than a simple passive conduit, playing an integral part in the cardiac cycle. The LA has three fundamental functions: reservoir, conduit and contractile function.

Reservoir function: during the left ventricle (LV) systole the LA acts as a reservoir receiving blood from the pulmonary veins. This phase takes place during LV contraction and isovolumetric relaxation and depends on the compliance of the LA [

1].

Conduit function: it’s a passive faze in which the blood flows from LA to LV. This phase takes place during LV relaxation and diastasis and depends on the pressure gradient between LA and LV and on the compliance of the LV [

2].

Contractile function: this phase takes place during LV telediastole. The LA has an active contraction and acts as a pump pushing approximately 20% of the blood flow to the LV. This pump function depends on preload, atrial myocardial contractility and telediastolic LV pressure and thus becomes truly important when LV filling pressure is increased[

3].

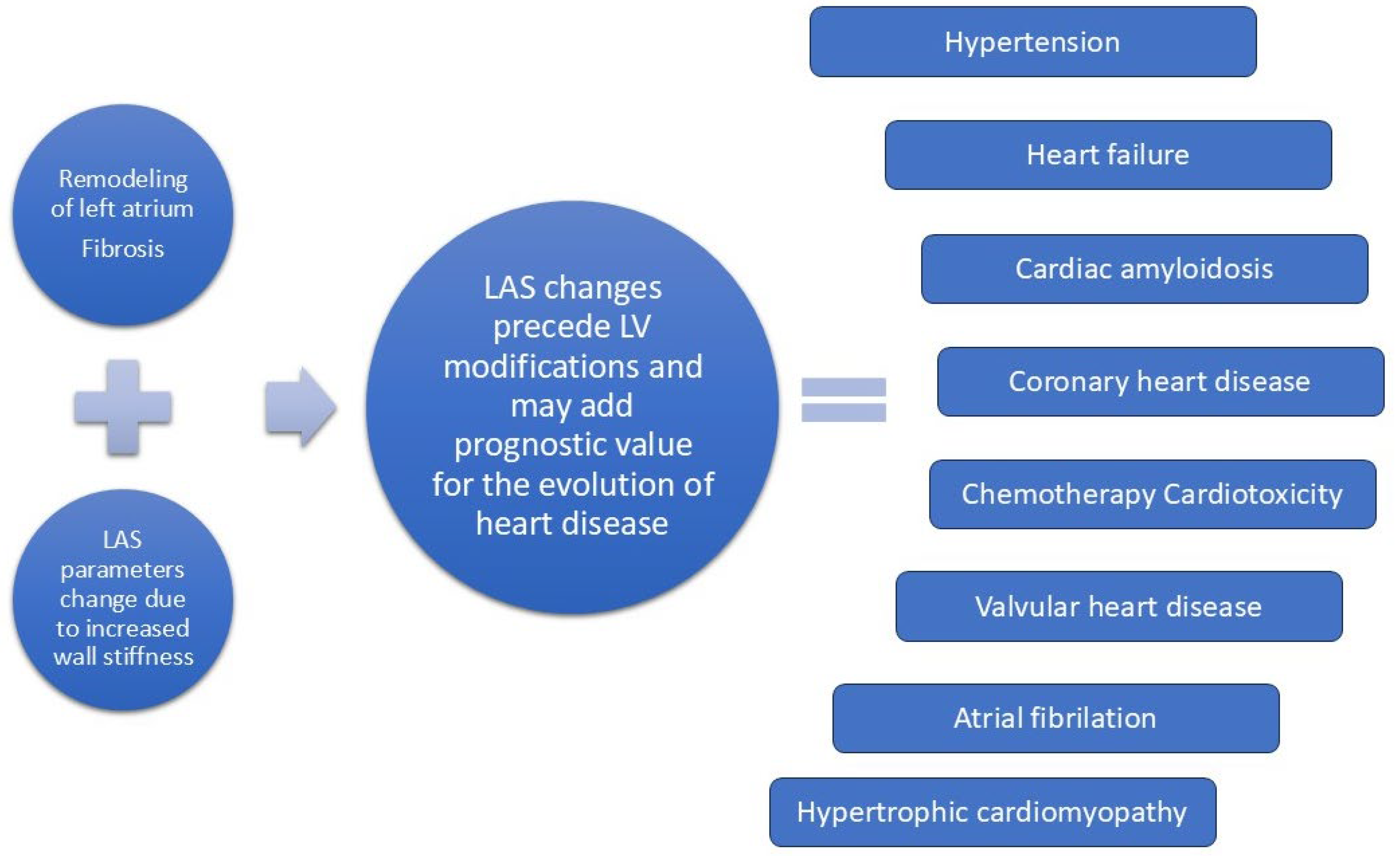

Analyzing left atrium function can improve diagnosis of subclinical left ventricle dysfunction and provide prognostic value for the evolution of various heart diseases (

Figure 1).

2. Assessment of LA Strain (LAS) by Echocardiography

The LAS can be analysed either through speckle tracking echocardiography (STE) or by using other imaging techniques such as cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) or cardiac computed tomography (CCT). Several recent studies have compared the assessment of LAS by STE with that obtained by CMR and CCT [

4,

5,

6,

7] showing that STE remains the superior method due to its higher accessibility and reliability.

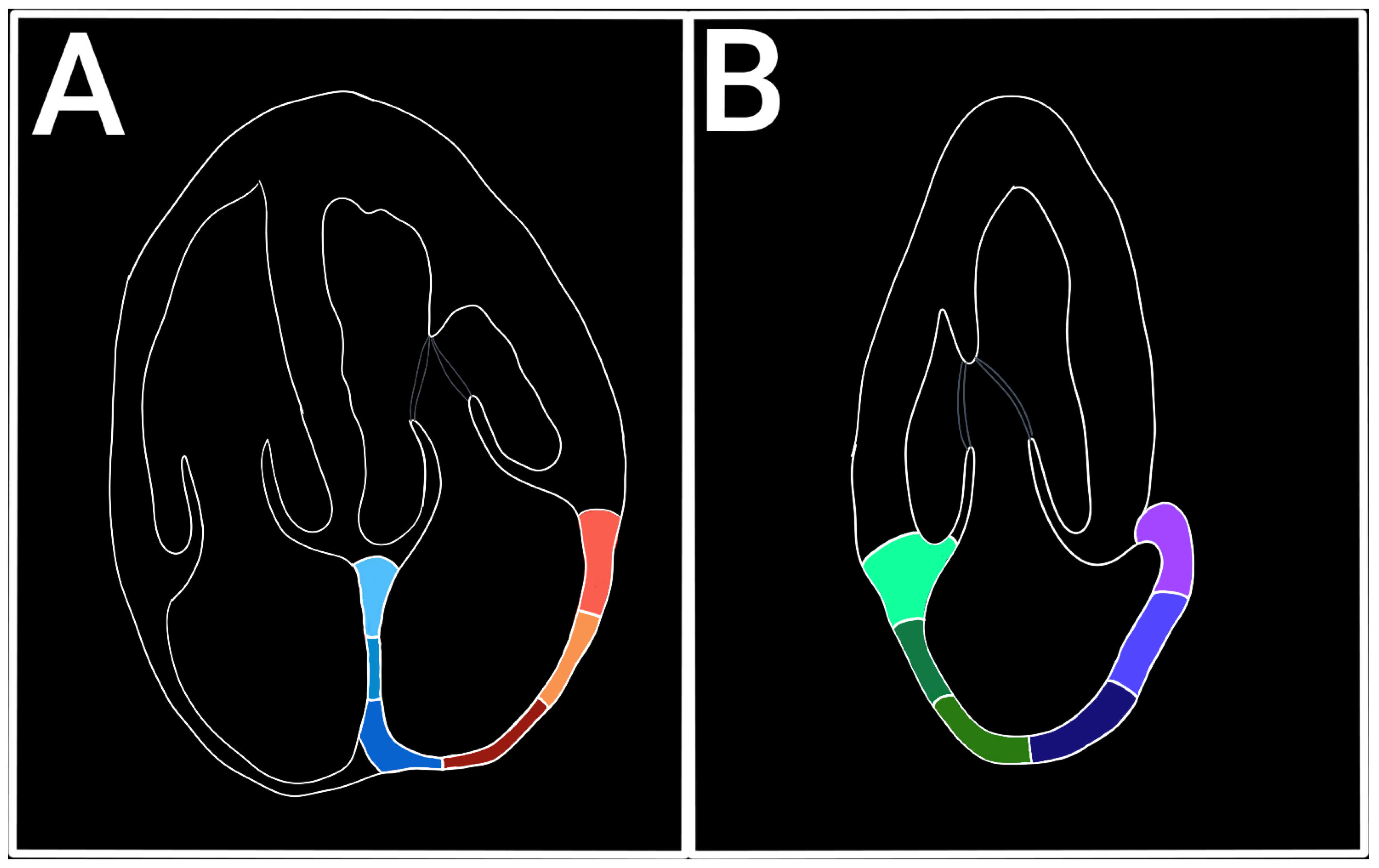

LAS represents the longitudinal deformation of the LA myocardium and evaluates the atrial function independent of its volume, being an early marker of atrial disfunction [

8,

9]. The LAS has a positive value during the filling phase (reservoir) when the LA dilates and the distance between two atrial points (or speckles) increases, and a negative value during the contraction phase when the distance between two atrial points shortens. The views used for LAS measuring are apical four chamber view (A4C) and apical two-chamber view (A2C). A4C view is the golden standard for LAS evaluation, while the A2C view can be used to complete the assessment. For speckle tracking analysis, the A4C view must be zoomed in on the LA without losing the valvular landmarks, excluding the pulmonary veins and the LA appendix[

10]. The optimal frame rate should be between 60-80 fps. A lower frame rate reduces the sensibility to the rapid movement of the LA myocardium.[

11] (

Figure 2).

In order to precisely determine LAS through STE, it is crucial to synchronize the image with the ECG tracing. It is also recommended to correlate with pulsed Doppler recording in order to better establish the beginning/ending of certain phases in the cardiac cycle. There are two possibilities for starting points in LAS measuring – the R wave and the P wave on ECG. Setting the starting point at the upslope of the R wave coincides with the telediastole, marking the closure of the mitral valve. This approach is more feasible and offers a higher reproducibility rate compared with the P wave [

12] and also permits a better analysis in patients with atrial fibrillation[

13]. The downsides of this method are the possible overestimation of the reservoir and conduit phases and also the possible omission of the negative curve associated with atrial contraction[

13] . By choosing the P wave as a reference point, we mark the beginning of the atrial systole. The limitations of this method are: 1) it needs a high-quality ECG, which can be difficult in tachycardic rhythms, artefacts or obese patients; 2) could omit the beginning of the reservoir phase. The benefits are: 1) it permits a detailed analysis of all three phases of the atrial cycle.[

14]; 2) the possibility to evaluate the atrial contraction after conversion of atrial fibrillation or after a paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. The ASE/EACVI guidelines recommend the upslope of the R wave as a golden standard for the reference point.

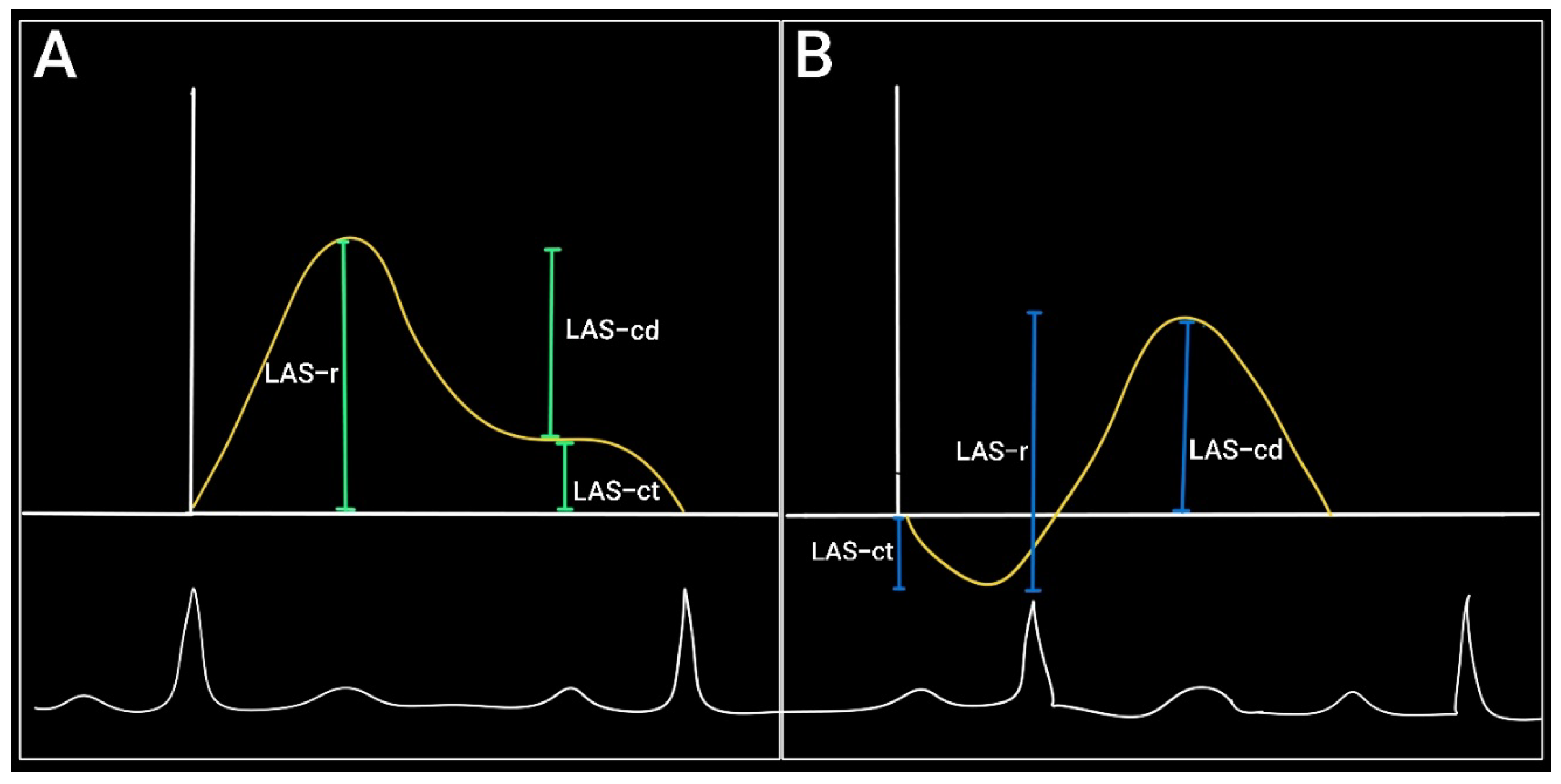

The evolution of the left atrial strain curve reflects the atrial dynamics during the cardiac cycle and consists of three phases:

Reservoir phase: between the closure and the opening of the mitral valve (concurs with ventricular contraction and isovolumetric relaxation). The LA acts as a passive reservoir and distends as it fills with blood from the pulmonary veins. During this phase the atrial longitudinal strain increases to a positive peak at the end of the atrial filling (peak atrial longitudinal strain – PALS).

Conduit phase: starts with the opening of the mitral valve and continues during the early ventricular diastole (E-wave). The atrial strain decreases with the rapid emptying of the LA until it reaches a plateau corresponding to the atrial diastasis.

Contraction phase (booster pump): starts in ventricular telediastole and consists of atrial contraction – it corresponds to the A-wave on pulsed Doppler. During this phase the longitudinal strain continues to drop reaching a minimum during atrial contraction – peak atrial contraction strain (PACS)[

15] .

If we base the analysis on the ventricular function then the reference point will be the QRS complex

. In this situation the first positive wave corresponds to the reservoir function (LAS-r) and the descending curve — rapid filling and atrial contraction — correspond to the conduit (LAS-cd) and pump function (LAS-ct) respectively[

16].

If we choose the P wave as a reference point then the first negative peak will reflect the pump function, the positive peak will correspond to the conduit function and the sum of the two will signify the reservoir function[

17] (

Figure 3).

The most recent EACVI consensus [

18,

19] establishes the end-diastole (R wave or the nadir of the atrial strain curve) as the primary reference point. This is because of its usefulness independent of the heart rate and also due to the ease in calculating LAS-r, which is the parameter with the most studied prognostic value [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]

.

STE also enables the determination of left atrial strain rate (LASR). It calculates the deformation rate of the atrial myocardium

. If we choose the R wave as reference point the LASR curve will have a positive peak corresponding to the reservoir phase during the ventricular systole (SRs) and two negative peaks – first reflecting the early rapid ventricular filling – the conduit phase (SRe) and the second representing the atrial contraction (SRa)[

26].

An important disadvantage for LASR is the difficult determination in irregular rhythms such as atrial fibrillation due to large variations in cardiac cycle [

27]

.

Also, determining LASR in tachycardic rhythms requires an increased frame rate [

28,

29].

Normal Values of Left Atrial Strain

Parameters of left atrial function measured by two-dimensional speckle tracking echocardiography include reservoir, conduit, and contractile LAS. Reference values have been proposed in several studies and international consensuses. In general, reservoir LAS has the highest clinical value, reflecting the maximum extension of the atrium in ventricular systole, while conduit and contractile LAS assess passive and active atrial function. Normal LAS parameters are presented in

Table 1 [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34].

3. Left Atrial Strain in Hypertension

In the last years LAS is rising as a potent marker that can detect early subclinical changes in the left atrium, that can precede structural modifications. Mondillio et al. analysed atrial function in patients with hypertension and diabetes, with normal dimensions of the LA [

36]. Peak atrial longitudinal strain was lower in patients with hypertension (29.0 ± 6.5%) and those with diabetes (24.7 ± 6.4%) than in controls (39.6 ± 7.8%) and further reduced in patients with diabetes and hypertension (18.3 ± 5.0%) (P < .0001). This suggest that atrial disfunction precedes structural modifications [

36].

Another study from 2022, published by Taamallah et al. showed that left atrial longitudinal strain during the reservoir and conduit periods is impaired in patients with hypertension despite normal cavity size and before the detection of other echocardiographic changes [

37]

.

Ting-Yan Xu et al. investigated 248 patients (124 with hypertension) demonstrating that hypertension is associated with impaired LA function, as assessed by STE strain imaging techniques, even before LA enlargement develops and after LV structural and functional remodeling is accounted for [

38]

. Furthermore, in the presence of impaired LA function, even white-coat or masked hypertension might be treated with hypertensive drugs.

In 2024 Stefani et al. published a study on 208 hypertensive patients showing that non-LVH hypertension patients had lower left atrial reservoir strain (LAS-r) (34.78 ± 29.78 vs. 29.78 ± 6.08;

P = 0.022) and conduit strain (LAS-cd) (19.66 ± 7.29 vs. 14.23 ± 4.59;

P = 0.014) vs. controls despite similar left atrial volumes (LAV) [

39]

. Left atrial contractile strain (LAS-ct) was not significantly different between non-LVH hypertension patients and controls (15.12 ± 3.77 vs. 15.56 ± 3.79;

P = 0.601).

A study from 2022 conducted on 290 hypertensive patients showed that left atrial stiffness index was significantly higher in non-dippers [0.29 (0.21, 0.41)] than in dippers [0.26 (0.21, 0.33)] (

P < 0.05). Brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity/GLS was significantly higher in non-dippers [-80.9 (-69.3, -101.5)] than in dippers [-74.2 (-60.2, -90.6)] (

P < 0.05). LA

S-S, LA

S-E, LA

S-A, and LV GLS were significantly lower in non-dippers than in dippers (

P < 0.05)[

40].

A metanalysis published in 2021 based on 17 studies with a pooled sample size of 1723 participants, which included 951 women with gestational hypertension, of which 680 were preeclamptic, and 772 controls showed that gestational hypertension is associated with greater cardiac maladaptation, evidenced by a significantly reduced GLS compared with normal pregnancy [

41].

A study published in 2024 by Mousa et al., which included patients recently diagnosed with systemic arterial hypertension, showed that PALS, PACS, E/e’, and LA stiffness index improved in hypertensive patients with controlled blood pressure values [

42].

A small study by Girard et al., conducted on 36 patients with resistant hypertension, who received spironolactone for 6 months, demonstrated a substantial increase in reservoir strain (29.1 ± 8.5 % vs 30.9 ± 5.5 %, p = 0.068) whereas active strain was significantly increased from baseline (16.3 ± 4.1 % vs 17.8 ± 4.2 %, p < 0.05), regardless of whether aldosterone levels were normal or high [

43]

.

4. Left Atrial Strain and Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) is defined in the 2021 ESC guidelines as: (1) Symptoms and signs of HF; (2) An LVEF ≥50% and (3) objective evidence of cardiac structural and/or functional abnormalities consistent with the presence of LV diastolic dysfunction/raised LV filling pressures, including raised natriuretic peptides (NPs)

. HFpEF emerges as a clinical entity with increasing prevalence, affecting especially the elderly population, hypertensive patients and those with multiple comorbidities. In HFpEF the diastolic dysfunction of LV determines an increase in LV filling pressure, which in turn triggers the LA functional and structural remodeling [

44].

In HFpEF the LA reservoir strain is mild to moderately reduced, the LA conduit strain is reduced (due to increased stiffness) and the LA pump strain is preserved in the initial phases and reduced in later stages [

45].

Table 2 provides a selection of recent studies regarding LAS in HFpEF [

46,

47,

48,

49,

50]:

5. Left Atrial Strain in Heart Failure with Mildly Reduced Ejection Fraction

Heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF) (LVEF=40-49%) was introduced as a separate clinical entity in the 2016 ESC guidelines

. This particular type of HF has intermediary characteristics between those of HFrEF and HFpEF. The prognosis for HFmrEF is better than HFrEF, being almost similar to that of HFpEF [

51]

.

An integrant part of the pathogenic processes in chronic heart failure, irrespective of ejection fraction, is the increase of diastolic pressures of the LA. This determines the stretching of atrial myocardium and the activation of fibrotic processes

. In time the LA suffers a remodeling process, represented by dilation, fibrosis, with a progressive decrease of the atrial compliance which in turn determines the increase of ventricular filling pressures creating a vicious cycle

. This pathogenic process is generically named atrial cardiomyopathy and includes all the complex changes in the morphology, mechanics and electrophysiology of the atria [

52]

.

As a marker of atrial deformation, LAS strongly correlated with all these modifications.

An important concept is that LA disfunction is a direct contributor to HF symptomatology. Normally, during physical effort, LV filling is improved by an increase in the reservoir and contractile functions of the LA. In patients with HFpEF, HFmrEF and HFrEF this functional reserve is compromised; thus, the effort tolerance decreases [

53,

54,

55].

In

Table 3 we included all the recent studies regarding the role of LAS determination in HFmrEF [

22,

25,

56,

57,

58].

6. Left Atrial Strain in Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction

In patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), high left atrial pressure (LAP) is a frequent finding, and can signify disease progression or decompensation of heart failure [

59].

LAS, particularly LASR, has become an important echocardiographic parameter in the evaluation of patients with HFrEF. LASR significantly correlates with left atrial pressure and LV filling pressure, and is a useful alternative to current ASA/EACVI algorithms for estimating LV diastolic dysfunction [

60].

E/A ratio, for example is often unavailable or significantly affected by atrial arrhythmias (eg. atrial fibrillation) and/or mitral valvopathies. E/A ratio is influenced by moderate/severe mitral regurgitation or stenosis, with an elevation of E wave velocity and LA dilation, making the evaluation of LAP by this algorithm unreliable. In atrial fibrillation the A wave (corresponding to atrial contraction) is missing and the LA is enlarged independent of LAP [

61,

62].

Although atrial disfunction was considered to be more prevalent in HFpEF, recent studies show that patients with HFrEF have a more severe atrial myopathy, with lower values for LASR. These findings suggest an intrinsic atrial myopathy, influenced by systolic ventricular disfunction and functional mitral regurgitation [

63].

7. Left Atrial Strain in Cardiac Amyloidosis

Cardiac amyloidosis (CA) is a particular form of restrictive infiltrative cardiomyopathy, characterized by extracellular deposits of abnormally folded amyloid fibrils in the myocardium. This deposition results in increased stiffness of ventricular myocardium with a progressive thickening which determines diastolic disfunction, elevated filling pressure of the LV and finally LA enlargement and disfunction [

67].

In 2023 Monte et al. show a significant reduction in all three LAS phases in patients with CA compared with those with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and the control group. These modifications were present even in patients with CA and preserved ejection fraction, highlighting the early atrial disfunction in CA [

68].

LAS proved to be a useful tool in the differential diagnosis between CA and other forms of ventricular hypertrophy, such as Fabry disease. In a study from 2024, Matting et al. have demonstrated that LAS can provide an accurate differential diagnosis between CA and Fabry disease, with a sensitivity of 90% and specificity of 64 % for a reservoir LAS of 20%[

69].

Table 5 contains recent studies into the use of LAS in cardiac amyloidosis [

70,

71,

72,

73,

74].

8. Left Atrial Strain and Coronary Heart Disease

It is a well-known fact that coronary artery disease is responsible for one third of global deaths and thus identifying new prognostic parameters for short- and long-term evolution after a coronary syndrome is a continuous task [

75].

Although risk assessment tools can be useful aids for physicians in establishing a patient therapeutic plan, there is a continuous need of finding new parameters for a better prevention and timely initiation of therapy in patients at risk or with coronary artery disease [

76].

In 2024, Pedersson et al. investigated the long-term prognostic value of left atrial strain indices – PALS and PACS as prognostic factors for all-cause mortality in patients with acute coronary syndromes [

77]. PALS and PACS proved to be independent predictors for mortality. A decrease by 1% of PALS was associated with a high risk of death (HR 1.04, p=0.002). This association was observed even in patient with a normal LA volume index (LAVI)[

77].

In ST elevation myocardial infarction patients LAS was an independent predictor for heart failure. A study by Ricken et al. published in 2024, with a mean follow up period of 8.8 years, showed that LASR has incremental value in the prediction of cardiovascular death, hospitalization for heart failure and new onset heart failure, when added in the prediction model comprised of age, sex, diastolic blood pressure and left ventricular ejection fraction [

78].

LASR also proved to be an independent prognostic factor for cardiovascular death and heart failure in 501patients with acute myocardial infarction with or without atrial fibrillation in a study by Tangen et al. from 2024 and Sikora et al. from 2025[

79,

80].

In a 2024 study that included patients with coronary artery disease, Tu et al. demonstrated that LASR combined with E/e’ ratio was an excellent predictor of elevated left ventricular filling pressures in patients with CAD. This combination had a stronger correlation with filling pressures compared to each individual parameter [

81].

9. Left Atrial Strain in Atrial Fibrillation

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most prevalent sustained cardiac arrhythmia globally, associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Early detection and risk stratification are paramount for effective management. AF disrupts reservoir, conduit, and contractile phases of LA function, leading to structural and electrical remodelling [

82]. Reduced LASR has been associated with elevated LA pressures and fibrosis, serving as a potential marker for AF onset, progression and recurrence [

82].

Over the past decade, numerous studies have explored the predictive value of LAS for elevated atrial pressure, new-onset atrial fibrillation (in various clinical settings, including the general population, post-stroke, post-myocardial infarction, and post-cardiac surgery), arrhythmia recurrence after cardioversion or ablation, and risk of thrombus formation (particularly in the LA appendage).

Table 6 summarizes the most recent studies, highlighting key findings on this topic:

While LAS provides valuable insights into LA function with significant implications in the detection, management, and prognostic of AF, standardization of measurement techniques and reference values is needed. Further large-scale, prospective studies are warranted to validate LAS as a routine clinical tool in AF management with applicability in risk stratification and therapeutic decisions.

10. Left Atrial Strain in the Assessment of Chemotherapy-Induced Cardiotoxicity

Early diagnosis and improved cancer management have increased cancer survival [

97], and thus cardiotoxicity associated with antineoplastic treatments has become more prevalent, inducing both short- and long-term complications [

98]. In this context, early detection of cardiac dysfunction is crucial to prevent irreversible damage.

Early detection of cardiotoxicity focuses on LV systolic function, with LV ejection fraction assessed by transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) being the most widely used method [

99]. However, reduction in LV ejection fraction is a late manifestation of cardiotoxicity [

100]. More recently, subclinical LV systolic dysfunction is identified by LV global longitudinal strain (LV GLS) by 2D-STE [

101]. Neither LV ejection fraction nor LV GLS can identify diastolic dysfunction which is an early marker of chemotherapy-related cardiotoxicity that often precedes the onset of systolic impairment [

102]. LAS has emerged as a sensitive and early marker of diastolic disfunction [

103] and thus its usefulness in early detection of cardiotoxicity is compelling. Reduced LAS, particularly in the reservoir phase, may indicate early diastolic dysfunction and elevated filling pressures, serving as an early marker of cardiotoxicity. Already, several prospective studies have shown a decline in LAS-r and LAS-cd shortly after initiation of cardiotoxic chemotherapy (e.g., anthracyclines, trastuzumab), often preceding changes in LV GLS and LVEF [

104,

105,

106,

107,

108,

109]. Regular assessment of LAS during chemotherapy can help track evolving myocardial changes and guide timely intervention.

Also, LAS may help identify patients with subclinical cardiac dysfunction before starting cardiotoxic chemotherapy, thus identifying patients at higher risk for cardiotoxicity. Persistent LAS abnormalities post-therapy may indicate ongoing subclinical dysfunction and necessity to continue monitoring. Integrating LAS into existing monitoring strategies, could improve risk stratification and individualize cardio-oncology care, potentially leading to earlier interventions and improved patient outcomes.

Several studies have demonstrated the clinical utility of LAS in monitoring patients undergoing chemotherapy.

Table 7 summarizing the most relevant publications from the past decade:

While short-term studies show promise, longer follow-up data are needed to correlate LAS changes with clinical outcomes. Also, there is still no universally accepted threshold for abnormal LAS in the context of cardiotoxicity and further research is needed to standardize measurement techniques and validate its prognostic utility across diverse patient populations.

11. LAS in Valvular Heart Disease

Valvular heart diseases (VHD), such as mitral regurgitation, mitral stenosis, and aortic stenosis, impose significant hemodynamic burdens on the LA. Chronic pressure and volume overload lead to structural remodelling and functional impairment of the LA, which are pivotal in the progression of VHD and its complications.

LAS in Mitral Regurgitation (MR)

In MR, the LA is subjected to volume overload, leading to dilation and functional deterioration. In a study of 121 patients with severe MR, Philippe Debonnaire et al. demonstrated that LAS-r was an independent predictor (odds ratio, 0.88; 95% confidence interval, 0.82-0.94; P < .001) which had the highest accuracy to identify patients with indications for mitral surgery. Patients with LAS-r ≤24% showed worse survival at a median of 6.4 after mitral surgery (P = .02), regardless the symptomatic status before surgery. LASR-r, on top of mitral surgery indications, provided incremental predictive value for postoperative survival [

111]. In another study, Leen van Garsse et al. found that left atrial strain (LAS) can help identify patients with chronic ischaemic MR who are undergoing undersized mitral ring annuloplasty but are unlikely to benefit from it. Specifically, lower values of left atrial peak global strain, peak systolic strain rate, and peak early diastolic strain rate were associated with recurrent MR after surgery [

112]. Another possible applicability of LAS in patients with MR is the prediction of cardiovascular outcomes in patients with moderate asymptomatic MR in order to identify higher-risk groups and, therefore, optimal time of surgery. Matteo Cameli et al. studied 395 patients with primary degenerative moderate asymptomatic MR and demonstrated that patients who developed cardiovascular events presented reduced PALS, reduced LA emptying fraction, larger LAVI and lower LV strain at baseline. From those, global PALS < 35% showed the greatest predictive performance to optimize timing of surgery before the development of irreversible myocardial dysfunction [

113].

LAS in Mitral Stenosis (MS)

MS results in increased LA pressure and subsequent remodeling. STE-derived LAS parameters, including reservoir, conduit, and contractile strains, are markedly diminished in patients with severe MS. These reductions correlate with the severity of stenosis and pulmonary hypertension, underscoring the role of LAS in assessing disease burden and guiding therapeutic decisions [

114].

LAS in Aortic Stenosis (AS)

AS primarily affects the LV; however, the resultant diastolic dysfunction leads to elevated LA pressures and remodeling. Recent studies have highlighted that decreased PALS is an independent predictor of adverse cardiovascular events in AS patients, even before the onset of symptoms. This suggests that LAS assessment can aid in early risk stratification and potentially influence the timing of aortic valve replacement [

115].

Author Contributions

writing—original draft preparation C.A.R., L.C. and L.M.R.; writing—review and editing, I.C.L. C.A.R. and L.C. contributed equally to this work and should be considered joint first authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| A2C |

Apical two chamber view |

| A4C |

Apical four chamber view |

| AF |

Atrial fibrillation |

| CA |

Cardiac amyloidosis |

| CCT |

Cardiac computed tomography |

| CMR |

Cardiac magnetic resonance |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

| GPALS |

Global peak atrial longitudinal strain |

| HFmrEF |

Heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction |

| HFpEF |

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction |

| HFrEF |

Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction |

| LA |

Left atrium |

| LAP |

Left atrial pressure |

| LAS |

Left atrium strain |

| LAS-cd |

Conduit function of LA |

| LAS-ct |

Pump function of LA |

| LASR |

Left atrial strain rate |

| LAS-r |

Reservoir function of LA |

| LAV |

Left atrial volume |

| LAVI |

Left atrial volume index |

| LV |

Left ventricle |

| LVEF |

Left ventricle ejection fraction |

| LVGLS |

Left ventricle global longitudinal strain |

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| NP |

Natriuretic peptides |

| PACS |

Peak atrial contraction strain |

| PALS |

Peak atrial longitudinal strain |

| STE |

Speckle tracking echocardiography |

| STEMI |

ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction |

| TTE |

Transthoracic echocardiography |

| VHD |

Valvular heart disease |

References

- K. Y. Kebed, K. Addetia, and R. M. Lang, “Importance of the Left Atrium: More Than a Bystander?,” Apr. 01, 2019, Elsevier Inc. [CrossRef]

- B. D. Hoit, “Left atrial size and function: Role in prognosis,” Feb. 18, 2014. [CrossRef]

- L. Thomas et al., “Compensatory Changes in Atrial Volumes With Normal Aging: Is Atrial Enlargement Inevitable?,” 2002.

- F. Pathan et al., “Left atrial strain: A multi-modality, multi-vendor comparison study,” Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 102–110, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Benjamin et al., “Comparison of left atrial strain by feature-tracking cardiac magnetic resonance with speckle-tracking transthoracic echocardiography,” Int J Cardiovasc Imaging, vol. 38, no. 6, pp. 1383–1389, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- T. Hosokawa et al., “Feasibility of left atrial strain assessment using cardiac computed tomography in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation,” Int J Cardiovasc Imaging, vol. 40, no. 8, pp. 1725–1734, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. Hosokawa et al., “Left atrial strain assessment using cardiac computed tomography in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy,” Jpn J Radiol, vol. 41, no. 8, pp. 843–853, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Thomas, T. H. Marwick, B. A. Popescu, E. Donal, and L. P. Badano, “Left Atrial Structure and Function, and Left Ventricular Diastolic Dysfunction: JACC State-of-the-Art Review,” Apr. 23, 2019, Elsevier USA. [CrossRef]

- G. Marincheva, Z. Iakobishvili, A. Valdman, and A. Laish-Farkash, “Left Atrial Strain: Clinical Use and Future Applications-A Focused Review Article,” 2022, IMR Press Limited. [CrossRef]

- V. Mor-Avi et al., “Current and Evolving Echocardiographic Techniques for the Quantitative Evaluation of Cardiac Mechanics: ASE/EAE Consensus Statement on Methodology and Indications,” Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography, vol. 24, no. 3, pp. 277–313, Mar. 2011. [CrossRef]

- M. Cameli et al., “Left Atrial Deformation Analysis by Speckle Tracking Echocardiography for Prediction of Cardiovascular Outcomes,” Am J Cardiol, vol. 110, no. 2, pp. 264–269, Jul. 2012. [CrossRef]

- M. Cameli et al., “Multicentric Atrial Strain COmparison between Two Different Modalities: MASCOT HIT Study,” Diagnostics, vol. 10, no. 11, p. 946, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Lu et al., “Evaluation of left atrial and ventricular remodeling in atrial fibrillation subtype by using speckle tracking echocardiography,” Front Cardiovasc Med, vol. 2023; 10. [CrossRef]

- S. Hayashi et al., “Optimal Analysis of Left Atrial Strain by Speckle Tracking Echocardiography: P-wave versus R-wave Trigger,” Echocardiography, vol. 32, no. 8, pp. 1241–1249, Aug. 2015. [CrossRef]

- F. de A. Figueiredo et al., “Left Atrial Strain: Clinical Applications and Prognostic Implications,” ABC Imagem Cardiovascular, vol. 37, no. 1, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Cameli et al., “Usefulness of Atrial Deformation Analysis to Predict Left Atrial Fibrosis and Endocardial Thickness in Patients Undergoing Mitral Valve Operations for Severe Mitral Regurgitation Secondary to Mitral Valve Prolapse,” Am J Cardiol, vol. 111, no. 4, pp. 595–601, Feb. 2013. [CrossRef]

- R. M. Saraiva et al., “Left Atrial Strain Measured by Two-Dimensional Speckle Tracking Represents a New Tool to Evaluate Left Atrial Function,” Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography, vol. 23, no. 2, pp. 172–180, Feb. 2010. [CrossRef]

- J.-U. Voigt, G.-G. J.-U. Voigt, G.-G. Mălăescu, K. Haugaa, and L. Badano, “How to do LA strain,” Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging, vol. 21, no. 7, pp. 715–717, Jul. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. P. Badano et al., “Standardization of left atrial, right ventricular, and right atrial deformation imaging using two-dimensional speckle tracking echocardiography: a consensus document of the EACVI/ASE/Industry Task Force to standardize deformation imaging,” Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging, vol. 19, no. 6, pp. 591–600, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

- A.-S. W. Svartstein et al., “Predictive value of left atrial strain in relation to atrial fibrillation following acute myocardial infarction,” Int J Cardiol, vol. 364, pp. 52–59, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Bo et al., “Incremental prognostic value of left atrial strain in patients with heart failure,” ESC Heart Fail, vol. 9, no. 6, pp. 3942–3953, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. Jia, A. Chen, D. Zhang, L. Fang, and W. Chen, “Prognostic Value of Left Atrial Strain in Heart Failure: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.,” Front Cardiovasc Med, vol. 9, p. 935103. 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. Modin, S. R. Biering-Sørensen, R. Møgelvang, A. S. Alhakak, J. S. Jensen, and T. Biering-Sørensen, “Prognostic value of left atrial strain in predicting cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the general population,” Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging, vol. 20, no. 7, pp. 804–815, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- P.-C. Hsu et al., “Prognostic role of left atrial strain and its combination index with transmitral E-wave velocity in patients with atrial fibrillation,” Sci Rep, vol. 6, no. 1, p. 17318, Feb. 2016. [CrossRef]

- F. Jia, A. Chen, D. Zhang, L. Fang, and W. Chen, “Prognostic Value of Left Atrial Strain in Heart Failure: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” Jul. 01, 2022, Frontiers Media S.A. [CrossRef]

- J. T. Kowallick et al., “Quantification of left atrial strain and strain rate using Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance myocardial feature tracking: A feasibility study,” Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, vol. 16, no. 1, Aug. 2014. [CrossRef]

- A. Sonaglioni, M. Lombardo, G. L. Nicolosi, E. Rigamonti, and C. Anzà, “Incremental diagnostic role of left atrial strain analysis in thrombotic risk assessment of nonvalvular atrial fibrillation patients planned for electrical cardioversion,” Int J Cardiovasc Imaging, vol. 37, no. 5, pp. 1539–1550. May 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Popescu, S. Bézy, and J.-U. Voigt, “Translating High-Frame-Rate Imaging into Clinical Practice: Where Do We Stand?,” Romanian Journal of Cardiology, vol. 33, no. 2, pp. 35–46, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J.-U. Voigt et al., “Definitions for a common standard for 2D speckle tracking echocardiography: consensus document of the EACVI/ASE/Industry Task Force to standardize deformation imaging,” Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 1–11, Jan. 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. Sun et al., “Normal Reference Values for Left Atrial Strain and Its Determinants from a Large Korean Multicenter Registry,” J Cardiovasc Imaging, vol. 28, no. 3, p. 186. 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. Pathan, N. D’Elia, M. T. Nolan, T. H. Marwick, and K. Negishi, “Normal Ranges of Left Atrial Strain by Speckle-Tracking Echocardiography: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography, vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 59-70.e8, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Yafasov et al., “Normal values for left atrial strain, volume, and function derived from 3D echocardiography: the Copenhagen City Heart Study,” Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging, vol. 25, no. 5, pp. 602–612, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. Sugimoto et al., “Echocardiographic reference ranges for normal left atrial function parameters: results from the EACVI NORRE study,” Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging, vol. 19, no. 6, pp. 630–638, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

- F. Pathan, N. D’Elia, M. T. Nolan, T. H. Marwick, and K. Negishi, “Normal Ranges of Left Atrial Strain by Speckle-Tracking Echocardiography: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography, vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 59-70.e8, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Yafasov et al., “Normal values for left atrial strain, volume, and function derived from 3D echocardiography: the Copenhagen City Heart Study,” Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging, vol. 25, no. 5, pp. 602–612, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Mondillo et al., “Early Detection of Left Atrial Strain Abnormalities by Speckle-Tracking in Hypertensive and Diabetic Patients with Normal Left Atrial Size,” Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography, vol. 24, no. 8, pp. 898–908, Aug. 2011. [CrossRef]

- K. Taamallah, W. Yaakoubi, A. Haggui, N. Hajlaoui, and W. Fehri, “Early detection of left atrial dysfunction in hypertensive patients: Role of Speckle Tracking imaging.,” Tunis Med, vol. 100, no. 11, pp. 788–799.

- T.-Y. Xu et al., “Left Atrial Function as Assessed by Speckle-Tracking Echocardiography in Hypertension,” Medicine, vol. 94, no. 6, p. e526, Feb. 2015. [CrossRef]

- L. D. Stefani et al., “Left atrial mechanics evaluated by two-dimensional strain analysis: alterations in essential hypertension,” J Hypertens, vol. 42, no. 2, pp. 274–282, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Q. Sun, Y. Pan, Y. Zhao, Y. Liu, and Y. Jiang, “Association of Nighttime Systolic Blood Pressure With Left Atrial-Left Ventricular–Arterial Coupling in Hypertension,” Front Cardiovasc Med, vol. 9, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. M. O’Driscoll et al., “Left Atrial Mechanics Following Preeclamptic Pregnancy,” Hypertension, vol. 81, no. 7, pp. 1644–1654, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Mousa, Z. Abdel Salam, M. ElSawye, A. Omran, and K. Aly, “Effect of Blood Pressure Control on Left Atrial Function Assessed by 2D Echocardiography in Newly Diagnosed Patients with Systemic Hypertension,” International Journal of the Cardiovascular Academy, Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. A. Girard, T. S. Denney, O. F. Sharifov, and S. G. Lloyd, “Spironolactone Improves Left Atrial Function and Atrioventricular Coupling in Resistant Hypertension,” Circulation, vol. 148, no. Suppl_1, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. Javadi et al., “Left Atrial Strain: State of the Art and Clinical Implications,” J Pers Med, vol. 14, no. 11, p. 1093, Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Kim et al., “Prognostic Implications of Left Atrial Stiffness Index in Heart Failure Patients With Preserved Ejection Fraction,” JACC Cardiovasc Imaging, vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 435–445, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. Kagami et al., “Impaired Left Atrial Reserve Function in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction,” Circ Cardiovasc Imaging, vol. 17, no. 8, p. e016549, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Kim et al., “Prognostic Implications of Left Atrial Stiffness Index in Heart Failure Patients With Preserved Ejection Fraction,” JACC Cardiovasc Imaging, vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 435–445, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. Maffeis et al., “Left atrial strain predicts exercise capacity in heart failure independently of left ventricular ejection fraction,” ESC Heart Fail, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 842–852, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Shin et al., “Prognostic Value of Minimal Left Atrial Volume in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction,” J Am Heart Assoc, vol. 10, no. 15, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Z. Ye, W. R. Miranda, D. F. Yeung, G. C. Kane, and J. K. Oh, “Left Atrial Strain in Evaluation of Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction,” Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography, vol. 33, no. 12, pp. 1490–1499, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Guțu and V. Rotari, “Particularitățile insuficienței cardiace cu fracție de ejecție ușor redusă,” Revista de Științe ale Sănătății din Moldova, vol. 3, no. 29, pp. 46–53, 2022.

- Goette et al., “EHRA/HRS/APHRS/SOLAECE expert consensus on atrial cardiomyopathies: Definition, characterization, and clinical implication,” Heart Rhythm, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. e3–e40, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Carpenito et al., “The Central Role of Left Atrium in Heart Failure,” Front Cardiovasc Med, vol. 8, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. Caminiti et al., “The Improvement of Left Atrial Function after Twelve Weeks of Supervised Concurrent Training in Patients with Heart Failure with Mid-Range Ejection Fraction: A Pilot Study,” J Cardiovasc Dev Dis, vol. 10, no. 7, p. 276, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. Bisbal, A. Baranchuk, E. Braunwald, A. Bayés de Luna, and A. Bayés-Genís, “Atrial Failure as a Clinical Entity,” J Am Coll Cardiol, vol. 75, no. 2, pp. 222–232, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. Al Saikhan, A. D. Hughes, W.-S. Chung, M. Alsharqi, and P. Nihoyannopoulos, “Left atrial function in heart failure with mid-range ejection fraction differs from that of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a 2D speckle-tracking echocardiographic study,” Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging, vol. 20, no. 3, pp. 279–290, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- C. Maffeis et al., “Left atrial function and maximal exercise capacity in heart failure with preserved and mid-range ejection fraction,” ESC Heart Fail, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 116–128, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. B. El-Saied, W. S. El-Sherbeny, and S. I. El-sharkawy, “Impact of sodium glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors on left atrial functions in patients with type-2 diabetes and heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction,” IJC Heart & Vasculature, vol. 50, p. 101329, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- X. Jin et al., “Left atrial structure and function in heart failure with reduced (HFrEF) versus preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF): systematic review and meta-analysis,” Heart Fail Rev, vol. 27, no. 5, pp. 1933–1955, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Lundberg et al., “Left atrial strain improves estimation of filling pressures in heart failure: a simultaneous echocardiographic and invasive haemodynamic study,” Clinical Research in Cardiology, vol. 108, no. 6, pp. 703–715, Jun. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Y. S. Aga et al., “Potential role of left atrial strain in estimation of left atrial pressure in patients with chronic heart failure,” ESC Heart Fail, vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 2345–2353, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Cameli, G. E. Mandoli, F. Loiacono, S. Sparla, E. Iardino, and S. Mondillo, “Left atrial strain: A useful index in atrial fibrillation,” Int J Cardiol, vol. 220, pp. 208–213, Oct. 2016. [CrossRef]

- X. Jin et al., “Patients with chronic heart failure and predominant left atrial versus left ventricular myopathy,” Cardiovasc Ultrasound, vol. 23, no. 1, p. 1, Feb. 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. Bouwmeester et al., “Left atrial reservoir strain as a predictor of cardiac outcome in patients with heart failure: the HaFaC cohort study,” BMC Cardiovasc Disord, vol. 22, no. 1, p. 104, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J.-H. Park, I.-C. Hwang, J. J. Park, J.-B. Park, and G.-Y. Cho, “Prognostic power of left atrial strain in patients with acute heart failure,” Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging, vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 210–219, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- E. Carluccio et al., “Left Atrial Strain in the Assessment of Diastolic Function in Heart Failure: A Machine Learning Approach,” Circ Cardiovasc Imaging, vol. 16, no. 2, p. e014605, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. Garcia-Pavia et al., “Diagnosis and treatment of cardiac amyloidosis: a position statement of the ESC Working Group on Myocardial and Pericardial Diseases,” Eur Heart J, vol. 42, no. 16, pp. 1554–1568, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- I. P. Monte et al., “Left Atrial Strain Imaging by Speckle Tracking Echocardiography: The Supportive Diagnostic Value in Cardiac Amyloidosis and Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy,” J Cardiovasc Dev Dis, vol. 10, no. 6, p. 261, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Mattig et al., “Right heart and left atrial strain to differentiate cardiac amyloidosis and Fabry disease,” Sci Rep, vol. 14, no. 1, p. 2445, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Puwanant, T. Suksiriworaboot, P. Kochaiyapatana, P. Puwatnuttasit, and S. B. Songmuang, “LEFT ATRIAL AND LEFT VENTRICULAR DEFORMATION IN IDENTIFYING ADVANCED STAGE OF CARDIAC AMYLOIDOSIS,” J Am Coll Cardiol, vol. 81, no. 8, p. 741, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. Oike et al., “Prognostic value of left atrial strain in patients with wild-type transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy,” ESC Heart Fail, vol. 8, no. 6, pp. 5316–5326, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- F. Edbom et al., “Assessing left atrial dysfunction in cardiac amyloidosis using LA–LV strain slope,” European Heart Journal - Imaging Methods and Practice, vol. 2, no. 3, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- F. Bandera et al., “Clinical Importance of Left Atrial Infiltration in Cardiac Transthyretin Amyloidosis,” JACC Cardiovasc Imaging, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 17–29, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Carvalheiro et al., “Left atrial mechanics and left ventricular function in cardiac amyloidosis patients treated with tafamidis,” Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging, vol. 26, no. Supplement_1, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Lindstrom et al., “Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risks Collaboration, 1990-2021,” J Am Coll Cardiol, vol. 80, no. 25, pp. 2372–2425, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Ionescu et al., “Cardiovascular risk estimation in young patients with ankylosing spondylitis: A new model based on a prospective study in Constanta County, Romania,” Exp Ther Med, vol. 21, no. 5, p. 529, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. R. Pedersson et al., “Left atrial strain is associated with long-term mortality in acute coronary syndrome patients,” Int J Cardiovasc Imaging, vol. 40, no. 4, pp. 841–851, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. W. L. M. Ricken et al., “Left atrial strain predicts long-term heart failure outcomes after ST-elevation myocardial infarction,” Int J Cardiol, vol. 422, p. 132931, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- J. Tangen et al., “The Prognostic Value of Left Atrial Function in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction,” Diagnostics, vol. 14, no. 18, p. 2027, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Sikora-Frac et al., “Usefulness of left atrial strain in detection of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in patients with first acute myocardial infarction.,” Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging, vol. 26, no. Supplement_1, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Y. Tu, X. Liu, X. Li, and N. Xue, “Left atrial stiffness index – an early marker of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in patients with coronary heart disease,” BMC Cardiovasc Disord, vol. 24, no. 1, p. 371, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Serenelli et al., “Atrial Longitudinal Strain Predicts New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation,” JACC Cardiovasc Imaging, vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 392–395, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Xu et al., “Left atrial strain parameters to predicting elevated left atrial pressure in patients with atrial fibrillation,” Echocardiography, vol. 41, no. 7, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- B. Uziębło-Życzkowska, P. Krzesiński, A. Jurek, K. Krzyżanowski, and M. Kiliszek, “Correlations between left atrial strain and left atrial pressures values in patients undergoing atrial fibrillation ablation,” Kardiol Pol, vol. 79, no. 11, pp. 1223–1230, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. G. Granchietti et al., “Left atrial strain and risk of atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass-grafting,” Int J Cardiol, vol. 422, p. 132981, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- C. Beyls et al., “Left atrial strain analysis and new-onset atrial fibrillation in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: A prospective echocardiography study,” Arch Cardiovasc Dis, vol. 117, no. 4, pp. 266–274, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Hauser et al., “Left atrial strain predicts incident atrial fibrillation in the general population: the Copenhagen City Heart Study,” Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 52–60, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. M. A. Rasmussen et al., “Utility of left atrial strain for predicting atrial fibrillation following ischemic stroke,” Int J Cardiovasc Imaging, vol. 35, no. 9, pp. 1605–1613, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- D. Zeng et al., “The Utility of Speckle Tracking Echocardiographic Parameters in Predicting Atrial Fibrillation Recurrence After Catheter Ablation in Patients with Non-Valvular Atrial Fibrillation,” Ther Clin Risk Manag, vol. Volume 20, pp. 719–729, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- N. Sabanovic-Bajramovic et al., “Left atrial strain significance in prediction of early atrial fibrillation recurrence after cardioversion and ablation,” Europace, vol. 25, no. Supplement_1. May 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Li et al., “Left atrial strain for predicting recurrence in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation after catheter ablation: a single-center two-dimensional speckle tracking retrospective study,” BMC Cardiovasc Disord, vol. 22, no. 1, p. 468, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. A. Moreno-Ruiz et al., “Left atrial longitudinal strain by speckle tracking as independent predictor of recurrence after electrical cardioversion in persistent and long standing persistent non-valvular atrial fibrillation,” Int J Cardiovasc Imaging, vol. 35, no. 9, pp. 1587–1596, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Abdelhamid, R. Biomy, H. Kabil, M. Raslan, and S. Mostafa, “Association of Left Atrial Deformation Analysis by Speckle Tracking Echocardiography With Left Atrial Appendage Thrombus in Patients With Primary Valvular Heart Disease,” Cureus, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Cameli et al., “Left Atrial Strain Predicts Pro-Thrombotic State in Patients with Non-Valvular Atrial Fibrillation,” J Atr Fibrillation, vol. 10, no. 4, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- K. Kupczynska et al., “Association between left atrial function assessed by speckle-tracking echocardiography and the presence of left atrial appendage thrombus in patients with atrial fibrillation,” The Anatolian Journal of Cardiology, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 15–22. 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Sasaki et al., “Left atrial strain as evaluated by two-dimensional speckle tracking predicts left atrial appendage dysfunction in patients with acute ischemic stroke,” BBA Clin, vol. 2, pp. 40–47, Dec. 2014. [CrossRef]

- K. D. Miller et al., “Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2019,” CA Cancer J Clin, vol. 69, no. 5, pp. 363–385, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- N. Bansal et al., “Strategies to prevent anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity in cancer survivors,” Cardio-Oncology, vol. 5, no. 1, p. 18, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Nicol, M. Baudet, and A. Cohen-Solal, “Subclinical Left Ventricular Dysfunction During Chemotherapy,” Card Fail Rev, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 31–36, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Awadalla, M. Z. O. Hassan, R. M. Alvi, and T. G. Neilan, “Advanced imaging modalities to detect cardiotoxicity,” Curr Probl Cancer, vol. 42, no. 4, pp. 386–396, Jul. 2018. [CrossRef]

- K. Negishi, T. Negishi, J. L. Hare, B. A. Haluska, J. C. Plana, and T. H. Marwick, “Independent and Incremental Value of Deformation Indices for Prediction of Trastuzumab-Induced Cardiotoxicity,” Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography, vol. 26, no. 5, pp. 493–498. May 2013. [CrossRef]

- S. F. Nagueh et al., “Recommendations for the Evaluation of Left Ventricular Diastolic Function by Echocardiography: An Update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging,” Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography, vol. 29, no. 4, pp. 277–314, Apr. 2016. [CrossRef]

- H. Park et al., “Left atrial longitudinal strain as a predictor of Cancer therapeutics-related cardiac dysfunction in patients with breast Cancer,” Cardiovasc Ultrasound, vol. 18, no. 1, p. 28, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. Emerson et al., “Alterations in Left Atrial Strain in Breast Cancer Patients Immediately Post Anthracycline Exposure,” Heart Lung Circ, vol. 33, no. 5, pp. 684–692, May. 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. Inoue et al., “Early Detection and Prediction of Anthracycline-Induced Cardiotoxicity ― A Prospective Cohort Study ―,” Circulation Journal, vol. 88, no. 5, p. CJ-24-0065, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- D. Di Lisi et al., “Atrial Strain Assessment for the Early Detection of Cancer Therapy-Related Cardiac Dysfunction in Breast Cancer Women (The STRANO STUDY: Atrial Strain in Cardio-Oncology),” J Clin Med, vol. 12, no. 22, p. 7127, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Chen et al., “Assessment of left heart dysfunction to predict doxorubicin cardiotoxicity in children with lymphoma,” Front Pediatr, vol. 11, May. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Laufer-Perl et al., “Left Atrial Strain changes in patients with breast cancer during anthracycline therapy,” Int J Cardiol, vol. 330, pp. 238–244, May. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Meloche et al., “TEMPORAL CHANGES IN LEFT ATRIAL FUNCTION IN WOMEN WITH HER2+ BREAST CANCER RECEIVING SEQUENTIAL ANTHRACYCLINES AND TRASTUZUMAB THERAPY,” J Am Coll Cardiol, vol. 71, no. 11, p. A1524, Mar. 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. Goyal et al., “Left Atrial Strain as a Predictor of Early Anthracycline-Induced Chemotherapy-Related Cardiac Dysfunction: A Pilot Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” J Clin Med, vol. 13, no. 13, p. 3904, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- P. Debonnaire et al., “Left Atrial Function by Two-Dimensional Speckle-Tracking Echocardiography in Patients with Severe Organic Mitral Regurgitation: Association with Guidelines-Based Surgical Indication and Postoperative (Long-Term) Survival,” Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography, vol. 26, no. 9, pp. 1053–1062, Sep. 2013. [CrossRef]

- L. van Garsse et al., “Left atrial strain and strain rate before and following restrictive annuloplasty for ischaemic mitral regurgitation evaluated by two-dimensional speckle tracking echocardiography,” Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging, vol. 14, no. 6, pp. 534–543, Jun. 2013. [CrossRef]

- M. Cameli et al., “Prognostic value of left atrial strain in patients with moderate asymptomatic mitral regurgitation,” Int J Cardiovasc Imaging, vol. 35, no. 9, pp. 1597–1604, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- V. Mehta et al., “Left atrial function by two-dimensional speckle tracking echocardiography in patients with severe rheumatic mitral stenosis and pulmonary hypertension,” Indian Heart J, vol. 74, no. 1, pp. 63–65, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. C. Lacy, J. D. Thomas, M. A. Syed, and M. Kinno, “Prognostic value of left atrial strain in aortic stenosis: A systematic review,” Echocardiography, vol. 41, no. 5. May 2024. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).