1. Introduction

Across diverse countries, cities, towns and villages in Africa, toilet access and provision are not adequately prioritized in spatial and development planning. The result of this is that some 779 million people experience toilet suffering–i.e., deficient access to adequate, safe and clean toilets–forcing about 208 million of them to resort to open defecation (WHO, 2022a).

One of the key sectors in Africa where the marginalization of toilet provision plays out more clearly is the urban transport sector. Most urban dwellers walk a great deal to access work and services in Africa. For longer distances, however, they rely on minibuses, shared taxis, motorcycles and private cars (Klopp and Cavoli, 2019; du Preez et al., 2019). These mobility modes and their routes are often not equipped with toilets. Some bus terminals or stations in the cities have toilets; but concerns exist about their safety and cleanliness (Yeboah-Afari, 2023).

Thus, overall, urban mobility systems in Africa are poorly aligned to reasonable and reliable access to adequate, safe and clean toilets. In 2020, matters came to a head in the continent when a public interest lawyer, Adrian Kamotho Njenga, successfully sued Kenyan authorities, compelling them to provide toilets to address the “immense biological, metabolical and physiological torture” commuters suffer “when faced with a call of nature while travelling on Kenyan roads” (BBC News, 2020).

Sanitation and development scholars and practitioners have extensively documented the impacts of toilet suffering and inadequate access to sanitation generally in Africa on social and economic development. These include their adverse effects on public health (e.g., causes diseases and deaths–Spears, 2013; Momberg et al, 2021); women’s safety (e.g., toilet access-linked sexual violence against women–Gibbs et al., 2021; Abrahams et al., 2006) and girl-child education (e.g. school absenteeism and outright abandonment among girls during menstruation–Grant et al., 2013; UNESCO, 2014) and the economy generally (e.g., increases health spending and productivity losses–World Bank, 2012).

The sustainable urban transport impacts, however, remain very much under researched, with the accumulating body of research on toilet access and everyday urban mobilities built on the experiences on non-African countries, primarily focused on the situations of the so-called advanced countries (Greed, 2005; 2012; Slater and Jones, 2018; Molotch, 2010; 2011; Norén, 2010; White, 2023). For instance, Boateng (2023) recently explored toilet suffering among public transport operators in US cities. Laura Norén (2010) and Mass et al (2014) reviews of occupations that contribute to voiding dysfunction focused on New York’s taxi sector. Lauren White’s recent review of mundane urban mobilities and everyday public toilet access focused on the experiences of people living with irritable bowel syndrome in the UK (White, 2023). Similarly, Slater and Jones’ and Help the Aged’s reviews of the influence of toilet access on transport mode choices explored the experiences of UK urban commuters (Slater and Jones, 2018; Help the Aged, 2007).

As a first step to gaining a deeper understanding, and to providing directions for future research, this paper draws on the international literature to contribute to the limited research on the spatial dimensions of toilet access as a tale of mobilities in African cities, outlining some critical sustainable transport implications of Africa’s toilet access crisis that could benefit from knowledge building and further learning. The paper was guided by the following questions: In what ways does the marginalization of toilet provision in urban development and spatial planning affect equitable access to safe, and pleasant transport in Africa? What guidance and ideas can yield from considering the international literature on the topic to inform directions for future research in the continent?

After this overview,

Section 2 presents the methods the study employed to identify the literature gap it explored.

Section 3 reviews and critiques the current focus of toilet access and sustainable development research and policy in Africa.

Section 4 makes a case for mobility/transportation grounding for toilet suffering.

Section 5 concludes with directions for future research.

2. Methods

The study sought to gauge whether the available published studies cover a specific dimension of the topic, instead of drawing together, appraising and synthesizing all known knowledge on the topic as often done in systematic reviews. This made the systematized review methodology appropriate for the study. The methodology allows researchers to employ elements and, hence, benefit from the rigor of the systematic review approach without following all the underlying procedures (Grant & Booth, 2009). For instance, in this study, while the literature search followed the Boolean keyword search approach widely used to assemble materials for systematic reviews, the study did not use the PRISMA framework often employed to present systematic reviews results.

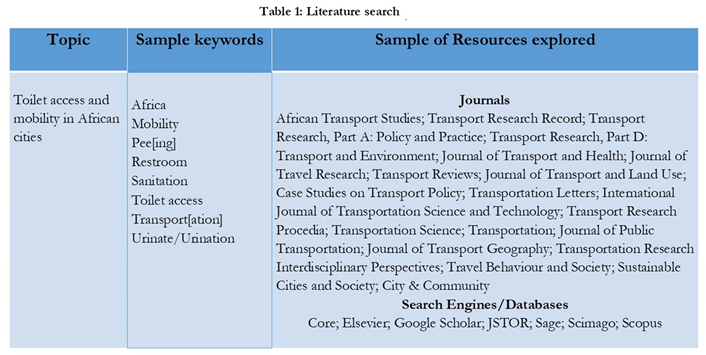

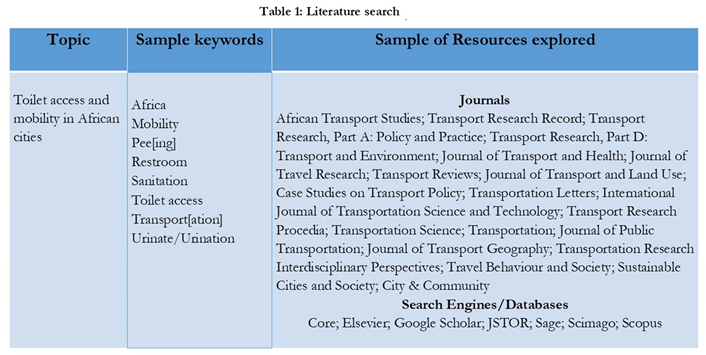

Since systematized reviews do not comply fully with the requirements of systematic review, Grant & Booth (2009, p. 102) describe them as “‘systematic’ review” (in parenthesis). While the incorporation of key methodological elements of systematic review in systematized reviews raises the quality of such studies to an appreciable level of systematicity, their replicability potential tends to be lower than those that adhere more strictly and fully to systematic review guidelines. To address these shortcomings in this study where the PRISMA reporting approach was not followed, a transparent account of the literature search process has been provided. Table 1 provides the list of databases, search engines and journals in which the literature searches were performed and the keywords used. This is to facilitate peer review or replication of the literature search process to ascertain the paper’s conclusion about the lack of published studies on toilet access or suffering in urban transport context in Africa.

In operationalizing the systematized review methodology, the hundreds of papers published in Elsevier’s 54 transportation journals and Sage’s 34 urban studies and planning journals were queried with keywords such as “transport/transportation and toilet access in African cities”, “mobility and toilet access in African cities” “peeing while traveling in African cities” “restroom/rest stop and urban mobility/transport”, “sanitation and urban mobility/transport in Africa”. These searches did not yield any title or abstract hits of published papers on toilet access and urban mobility or transport in Africa.

Similar keyword queries into the top 50 transportation journals indexed in SCImago and the 34 top 10% transportation journals indexed in Scopus as well as the volumes of papers indexed in CORE and JSTOR too returned no title or abstract hits of published research on the topic. More general searches on Google Scholar, however, returned some important studies published on rest stops or roadside stations in Africa (Beck, 2013; Danso et al., 2023; Ezezue et al., 2019; Mohamed & Abdel-Gawad, 2011; Sam & Abane, 2017; UNECA, 2022). Among other things, these transport infrastructures, often located along highways, provide layover spaces for commuters to rest; this potentially reduces driver fatigue-related crash incidents and other road transport problems (Sam & Abane, 2017; Ezezue et al., 2019).

While the studies show that some rest stops in Africa have toilets, the facilities are often not at the center of their analyses. Instead, they focus on the general significance of such social road transport infrastructure including serving as places for commuters to relax, access goods and services and socialize during their journey break (Beck, 2013; Mohamed & Abdel-Gawad, 2011; UNECA, 2022). Second, considering that rest stops are often located at city outskirts, providing toilet facilities in such social transport settings does not exactly aid access in the cities. Thus, the research on rest stops offers little insight into the highly under researched issue of toilet access and urban mobility in Africa.

3. Policy and Research Concerns About Toilet Suffering in Africa: A Brief Overview & Critique

Toilet suffering and inadequate access to sanitation generally in Africa has received sustained attention including from researchers (Grant et al., 2013; Gibbs et al., 2021; Abrahams et al., 2006; Charles, 2015; Spears, 2013; Momberg et al, 2021) and international development actors (World Bank, 2012; WHO, 2018a; UNESCO, 2014). A key focus of the policy and research conversation on the topic is its adverse effects on public health. Here emphasis is placed on the diseases and deaths linked to the marginalization of toilet provision or inadequate access to adequate sanitation generally (Charles, 2015; Spears, 2013; Momberg et al, 2021). For instance, the literature suggests that children are highly impacted by the health risks associated with inadequate access to sanitation in Africa, with research showing risks of malnutrition (Momberg et al, 2021; van Cooteen et al., 2019), particularly stunting (Merchant et al., 2003; Spears, 2013).

A body of studies also exists on toilet or sanitation suffering generally and gender and development (Grant et al., 2013; UNESCO, 2014; Gibbs et al., 2021; Abrahams et al., 2006). Thus, research has shown that marginalization of toilet provision in schools to support sanitation and menstrual needs forces girls to skip and, in some cases, entirely drop out of school (Grant et al., 2013; UNESCO, 2014), deepening the gender disparities in education and the related socio-cultural-political economic benefits. Some studies have shown also that inadequate access to (indoor) toilet facilities exposes women and girls to sexual coercion or violence (Gibbs et al., 2021; Abrahams et al., 2006). Other studies have focused on the economic losses of inadequate sanitation. For instance, a 2012 World Bank study revealed that some 18 African countries lose around US$5.5 billion every year due to poor sanitation, with annual economic losses between 1 and 2.5% of GDP (World Bank, 2012).

Overall, the current research and policy approaches shed light on many of the sustainable development challenges linked to persisting marginalization of toilet provision and inadequate access to sanitation generally in Africa. These include its adverse impacts on public health, economic growth and vulnerable populations such as children, girls, and women. A very important development issue that seldom features in toilet or sanitation suffering policy and research in Africa is its impact on sustainable urban transport. Thus, as shown earlier, a systematized review of the volumes of sustainable mobility/transport and cities papers published in the hundreds of journals indexed in Core, Elsevier, Google Scholar, JSTOR, Sage, SCImago, Scopus and other similar scholarly databases shows a dearth of published studies on toilet access in urban transport context in Africa.

4. Why a Mobility/Transport Grounding for Toilet Access in Africa Is Warranted

The lack of research focus on toilet access and mobility in Africa is striking considering that people literally carry their toilet needs with them when traveling, regardless of the mobility mode–whether via walking, bicycle, private car or public transport. Thus, as recently observed by University of Sheffield’s Laura White, “toilets work as connective devices within the everyday journeys of publics” (White, 2023: 855). The point here is that life-making is primarily founded on banal or mundane mobility regularities including commuting to access work, healthcare, education, food, leisure, and other necessities of life (Binnie et al., 2007; Greed, 2012; Sheller & Urry, 2006 in White, 2023).

Such mobilities offer certainty, security and an ability to pursue everyday life with peace of mind. However, as White (2023) correctly observed, “When considering toilets as constitutive of mobilities, such assurances cannot be established in light of uncertain provision” (pp. 855–856). Thus, lack of reasonable and reliable access to adequate, safe and clean toilets outside the home can undermine the quality of people’s mobility experience. Consider the cases of public transport operators and users for instance. Using or operating public transport means giving up a certain amount of control over one’s schedule and surrendering oneself to the transport system. Unlike private car users, if the public transport or the route is not equipped with a toilet, the commuter or operator cannot simply speed back home or to the nearest available toilet and use it. Disembarking to find a toilet means abandoning the commuters onboard in the middle of the journey (in the case of operators) or, in the case of commuters, waiting several minutes for the next public transport–with implications for long delays and appointment misses.

All these suggest that anxiety around toilet access is likely to have some critical influences on people’s spatial practices and social participation as well as play into the general quality of mobility experience. These issues and the related potential spatial exclusion and inequality implications are likely to become more salient in Africa as the ageing populations increase. Thus, while Africa’s population is currently exceptionally young compared to other world regions, projections show that, 30 years from now, the older population will reach 235 million, surpassing that of Latin America and Northern America and approximating that of Europe (He, 2022; He et al., 2020). African countries with more than a million older adults will increase to 36 and 7 of them will each have at least 10 million older adults. Also, Africa will be the only region to experience a consistent increase in older population every successive decade between 2020 and 2050 (He, 2022; He et al., 2020).

The international literature on toilet access and everyday mobilities shows that toilet inaccessibility (including lack of provision, poor design, and inappropriate use) leads to traveling avoidance among the aged who tend to need frequent access to toilets, limiting their spatial practices and social participation beyond the home (Greed, 2006; 2012; White, 2023; Slater & Jones, 2018). Yet, access to societal participation beyond the home is critical to quality of life in old age (Holland et al., 2005; Bichard and Knight, 2012; Schwanen, & Páez, 2010). Thus, the marginalization of toilet provision in mobility and spatial planning can contribute to an increased sense of social isolation and withdrawal from wider social activities, and, to that end, increased feelings of loneliness and depression among Africa’s aged populations.

Increased incidents of such psycho-sociological mental health concerns among such vulnerable populations, emerging from self-enforced isolation linked to deficient access to adequate, safe and clean toilet outside the home, can only draw further on health and social service budgets in the continent. All these raise the need for directing more scholarly resources into generating data and systematized analyses on toilet access and mobility to inform policies for building sustainable, accessible and inclusive cities that can better guarantee equitable everyday access, public participation and citizenship for the aged and other similarly situated classes of people in Africa.

Another issue that raises the need for a deeper scholarly focus on toilet access and mobility in Africa regards its likelihood of playing into public health-undermining practices such as open defecation and urination. These practices contribute to the spread of antimicrobial resistance; the transmission of diseases such as cholera and dysentery, as well as typhoid, intestinal worm infections and polio (Charles, 2015; WHO, 2022b), and exacerbate malnutrition among children (Spears, 2013; Momberg et al, 2021). The marginalization of toilet provision in transportation and spatial planning likely contributes to commuter involvement in such practices in the continent. Thus, commuters who suffer impeded access to toilet while out and about are likely to release themselves in bushes, gutters and other similar open spaces as occurring in other parts of the world (Boateng, 2023; Norén, 2010), raising the need to push more research into making toilet access more valued and embedded in transportation planning and policy in the continent.

Finally, the influence of toilet suffering on driver behavior also raises a need for knowledge building on toilet access and mobility in Africa. The accumulating body of international research on toilet access and everyday mobilities shows that across otherwise diverse contexts, commuters and drivers alike commonly resort to the practice of ‘holding it in’, they actively inhibit their need to void, as a strategy for coping with deficient access to toilet while traveling (Boateng, 2023; Norén, 2010; Greed, 2006; Molotch, 2008). Concerns about this voiding inhibition practice tend to focus on the adverse genitourinary health implications including its potential to cause kidney, urinary tract and bladder infections and weakening (Attoh, 2019; Brown, 2012; Mass et al., 2014; Norén, 2010). Nevertheless, the practice poses road safety concerns, warranting attention in safe mobility research in Africa.

In their review of the effect of acute increase in urge to void on cognitive function in healthy adults, Matthew Lewis of University of Melbourne and his colleagues showed that people who cannot urinate when their bladder is full experience cognitive or attention impairments equivalent to staying awake for 24 hours or having a blood alcohol concentration (BAC) level of 0.05% (Lewis et al, 2011). This exceeds or is equivalent to the BAC limits placed on drivers in many African countries. For instance, according to WHO data, the legal BAC limit is 0.05% for all categories of drivers in Tunisia; 0% (total ban) in Sudan; 0.02% for commercial/professional drivers in South Africa; 0.02% for all drivers in Morocco; 0% (total ban) in Mauritania; 0.03% for all drivers in Mali and 0.04% for all drivers in Madagascar (WHO, 2018b).

These suggest that driving with a full bladder seems just as much–if not more–dangerous as drunk or fatigue driving, raising a need for expanding the frontiers of safe mobility research in Africa (Assailly and Cestac, 2018; Asiamah et al., 2002; Becker, 1994; Boateng, 2020; 2021; Damsere Derry et al., 2014; Matzopoulos et al., 2018; Mock et al., 2001) to consider how the marginalization of toilet provision in transportation and spatial planning plays into unsafe road transport outcomes in the continent.

5. Conclusions: Directions for Future Research

The paper has made a case for a deeper scholarly focus on the sustainable transport impacts of the marginalization of toilet provision in urban transport and spatial planning in Africa. Some of the key areas that could benefit from knowledge building and further learning include how toilet access considerations influence mobility decisions and transport mode choices in the cities, and their implications. Another critical area worth exploring is commuters’ encounters with “accidents”, near misses, lateness, humiliation or abrupt changes to itineraries linked to personal hygiene needs while traveling. It will also be worthwhile for future research to explore and quantify the amount of time commuters spend searching for toilets or the alternative arrangements they make to manage their deficient access to toilet while away from home and their impacts on productivity, their personal safety and that of their belongings.

It is highly likely that when in need of toilet while out and about, some urban commuters, as occurring elsewhere (Boateng, 2023; Molotch, 2008; 2010), patronize toilet facilities available in fuel stations, hotels, restaurants, banks, coffee shops, hair salons and many other establishments in the cities. However, we do not yet understand the issues surrounding access to such toilet facilities. For instance, what are the access protocols? What avenues exist for improving and scaling access to such facilities and which actors are better placed to lead such a change? Future research should explore these questions and their corollaries.

The political economy of toilet provision or consideration in urban transport and spatial planning also deserves research attention. Here, researchers can engage the public and policy leaders, transport unions and companies and agencies and other relevant stakeholders on the range of factors, interests, and actors (or their lack thereof) that have significance for understanding the inadequate prioritization of toilet access in transportation and development planning generally. The data and systematized analyses that will emerge from such studies can help center toilet access in spatial and development planning in Africa’s cities; some scholars argue that toilet access is a ‘missing link’ in the sustainable cities’ agenda (Greed, 2012; White 2023; Washington, 2014).

Finally, the international literature shows that toilet suffering is a major occupational health and safety concern in many advanced countries, exposing public transport operators to diseases such as urinary tract and bladder infections and weakening (Boateng, 2023; Brown, 2012; Attoh, 2019). As a result, the phenomenon is becoming one of the key catalysts for strikes and other industrial actions in their public transport sectors (Moore, 2011; TransitCenter, 2019). Generating comparable occupational health and labor-related data and systematized evidence in the African context will be worthwhile for moving policy, action, and investment toward prioritizing access to adequate, safe and clean toilet as a valuable component of urban mobility planning and policy in the continent.

References

- Abrahams, N.; Mathews, S.; Ramela, P. Intersections of ‘sanitation, sexual coercion and girls’ safety in schools’. Tropical medicine & international health 2006, 11(5), 751–756. [Google Scholar]

- Asiamah, G.; Mock, C.; Blantari, J. Understanding the knowledge and attitudes of commercial drivers in Ghana regarding alcohol impaired driving. Injury prevention 2002, 8(1), 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assailly, J. P.; Cestac, J. Drunk driving prevention and cultural influences: the SAFE ROADS 4 YOUTH (SR4Y) project. Transactions on Transport Sciences 2018, 9(2), 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attoh, K. A. Rights in Transit: Public Transportation and the Right to the City in California’s East Bay; University of Georgia Press, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- BBC News. Kenya-where toilets have become a constitutional right. 2020. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-51413145 (accessed on 26 March 2024).

- Beck, K. Roadside Comforts: Truck Stops on the Forty Days Road in Western Sudan. Africa 2013, 83(3), 426–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, K. The consequences of drunken driving in South Africa. Med. & L. 1994, 13, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Bichard, J. A.; Knight, G. Improving public services through open data: public toilets. In Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers-Municipal Engineer; 2012; Vol. 165, No. 3, pp. 157–165. [Google Scholar]

- Boateng, F. G. “Indiscipline” in context: a political-economic grounding for dangerous driving behaviors among Tro-Tro drivers in Ghana. Nature: Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 2020, 7(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boateng, F. G. Why Africa cannot prosecute (or even educate) its way out of road accidents: insights from Ghana. Nature: Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 2021, 8(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boateng, F. G. When You Gotta Go, You Gotta Go: Public Transport Operators’ Deficient Access to Toilet in the United States (No. TRBAM-23-00193), 2023.

- Brown, T. Bus operator restroom use: Case study and practitioner resources from Minneapolis; Transportation Learning Center; SilverSpring, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Charles, K. African cities aren’t keeping up with the demand for basic toilets. 2015. Available online: https://theconversation.com/african-cities-arent-keeping-up-with-the-demand-for-basic-toilets-50917 (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Damsere Derry, J.; Afukaar, F.; Palk, G.; King, M. Determinants of drink-driving and association between drink-driving and road traffic fatalities in Ghana. The International Journal of Alcohol and Drug Research 2014, 3(2), 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danso, A. K.; Tudzi, E. P.; Ayarkwa, J.; Asiedu-Ampem, G.; Donkor-Hyiaman, K. A. Accessibility of pedestrian infrastructure along arterial roads to persons with disabilities in Kumasi. Ghana Journal of Development Studies 2023, 20(2), 25–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Preez, D.; Zuidgeest, M.; Behrens, R. A quantitative clustering analysis of paratransit route typology and operating attributes in Cape Town. Journal of Transport Geography 2019, 80(C). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezezue, A. M.; Ibem, E. O.; Kikanme, E. I. Safety Rest Areas and Fatigue Related Road Accidents in Enugu, Nigeria. International Journal of Innovative Technology and Exploring Engineering 8(8), 1137–1144.

- Gibbs, A.; Reddy, T.; Khanyile, D.; Cawood, C. Non-partner sexual violence experience and toilet type amongst young (18–24) women in South Africa: A population-based cross-sectional analysis. Global public health 2021, 16(4), 590–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, M. J.; Booth, A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health information & libraries journal 2009, 26(2), 91–108. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, M.; Lloyd, C.; Mensch, B. Menstruation and school absenteeism: evidence from rural Malawi. Comparative education review 2013, 57(2), 260–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greed, C. Discussion: Public toilets—the need for compulsory provision. In Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers-Municipal Engineer; Thomas Telford Ltd., 2005; Vol. 158, No. 2, pp. 153–154. [Google Scholar]

- Greed, C. The role of the public toilet: pathogen transmitter or health facilitator? Building Services Engineering Research and Technology 2006, 27(2), 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greed, C. H. A relação generificada entre o zoneamento urbano do transporte público e as implicações para a provisão de banheiros públicos. Revista Latino-Americana de Geografia e Gênero 2012, 3(2), 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W. Increases in Africa’s Older Population Will Outstrip Growth in Any Other World Region; 2022. Available online: https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2022/04/why-study-aging-in-africa-region-with-worlds-youngestpopulation.html#:~:text=Africa's%20population%20is%20exceptionally%20young,in%20every%20other%20world%20region (accessed on 28 October 2023).

- He, W.; Aboderin, I.; Adjaye-Gbewonyo, D. Africa Aging: 2020; United States Census Bureau; USCB: Suitland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Help the Aged. Nowhere to Go; Public Toilet Provision in the UK; Help the Aged: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, C; Kellaher, L; Peace, S; et al. Walker, A, Ed.; “Getting out and about”. In Understanding Quality of Life in Old Age; Open University Press; Maidenhead, UK, 2005; pp. 49–63. [Google Scholar]

- Klopp, J. M.; Cavoli, C. Mapping minibuses in Maputo and Nairobi: engaging paratransit in transportation planning in African cities. Transport Reviews 2019, 39(5), 657–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M. S.; Snyder, P. J.; Pietrzak, R. H.; Darby, D.; Feldman, R. A.; Maruff, P. The effect of acute increase in urge to void on cognitive function in healthy adults. Neurourology and urodynamics 2011, 30(1), 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mass, A. Y.; Goldfarb, D. S.; Shah, O. Taxi cab syndrome: a review of the extensive genitourinary pathology experienced by taxi cab drivers and what we can do to help. Reviews inurology 2014, 16(3), 99. [Google Scholar]

- Matzopoulos, R.; Lasarow, A.; Bowman, B. A field test of substance use screening devices as part of routine drunk-driving spot detection operating procedures in South Africa. Accident Analysis & Prevention 2013, 59, 118–124. [Google Scholar]

- Merchant, A. T.; Jones, C.; Kiure, A.; Kupka, R.; Fitzmaurice, G.; Herrera, M. G.; Fawzi, W. W. Water and sanitation associated with improved child growth. European journal of clinical nutrition 2003, 57(12), 1562–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mock, C.; Asiamah, G.; Amegashie, J. A random, roadside breathalyzer survey of alcohol impaired driving in Ghana. Traffic injury prevention 2001, 2(3), 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, N. M.; Abdel-Gawad, A. K. Improvement of highways rest area design case study: Cairo-Alexandria Desert Road, Egypt. World Applied Sciences 2011, (14), 21. [Google Scholar]

- Molotch, H. Peeing in public. Contexts 2008, 7(2), 60–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molotch, H. Molotch, H., Norén, L., Eds.; Introduction: Learning from the loo. In Public restrooms and the politics of sharing; New York University Press, 2010; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Molotch, H. Bridge, G., Watson, S., Eds.; Objects in the city. In The new blackwell companion to the city; Wiley-Blackwell, 2011; pp. 66–78. [Google Scholar]

- Momberg, D. J.; Ngandu, B. C.; Voth-Gaeddert, L. E.; Ribeiro, K. C.; May, J.; Norris, S. A.; Said-Mohamed, R. Water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) in sub-Saharan Africa and associations with undernutrition, and governance in children under five years of age: a systematic review. Journal of Developmental Origins of Health and Disease 2021, 12(1), 6–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, T. Bus(ting) drivers strike over toilet breaks. 2011. Available online: https://www.brisbanetimes.com.au/national/queensland/bus-ting-drivers-strike-over-toilet-breaks-20110719-1hmyi.html (accessed on 15 October 2023).

- Norén, L. “Only Dogs Are Free to Pee”. In Toilet: Public restrooms and the politics of sharing; (PDF) “When you Gotta Go, You Gotta Go”: Public Transport Operators’ Deficient Access to Toilet in the United States; Molotch, H., Norén, L., Eds.; NYU Press, 2010; Vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Sam, E. F.; Abane, A. M. Enhancing passenger safety and security in Ghana: Appraising public transport operators’ recent interventions. Journal of Science and Technology (Ghana) 2017, 37(1), 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwanen, T.; Páez, A. The mobility of older people: an introduction. Journal of Transport Geography 2010, 18(5). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spears, D. How much international variation in child height can sanitation explain? World Bank policy research working paper 2013, (6351). [Google Scholar]

- TransitCenter. The Right to Pee. 2019. Available online: https://transitcenter.org/the-right-to-pee/ (accessed on 15 October 2023).

- UN Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA). Development of roadside stations: ECA Policy Brief; UNECA: Addis Ababa, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Puberty education & menstrual hygiene management; Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- van Cooten, M. H.; Bilal, S. M.; Gebremedhin, S.; Spigt, M. The association between acute malnutrition and water, sanitation, and hygiene among children aged 6–59 months in rural E thiopia. Maternal & child nutrition 2019, 15(1), e12631. [Google Scholar]

- Washington, K. M. Go before you go: how public toilets impact public transit usage. PSU McNair Scholars Online Journal 2014, 8(1), 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, L. ‘I have to know where I can go’: mundane mobilities and everyday public toilet access for people living with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Social & Cultural Geography 2023, 24(5), 851–869. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Inadequate Sanitation Costs 18 African Countries Around US$5.5 Billion Each Year. 2012. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2012/04/16/inadequate-sanitation-costs-18-african-countries-around-us55-billion-each-year (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Delivering climate-resilient water and sanitation in Africa and Asia. 2018a. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/01-01-2018-delivering-climate-resilient-water-and-sanitation-in-africa-and-asia (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- World Health Organization (WHO). World Toilet Day 2022. 2022a. Available online: https://www.afro.who.int/regional-director/speeches-messages/world-toilet-day-2022#:~:text=Two%20out%20of%20three%20people,a%20safe%20toilet%20by%202030 (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Sanitation. 2022b. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/sanitation#:~:text=Over%201.7%20billion%20people%20still,into%20open%20bodies%20of%20water (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- World Health Organization (WHOb). Legal BAC limits by country. 2018. Available online: https://apps.who.int/gho/data/view.main.54600 (accessed on 30 July 2023).

- Yeboah-Afari, A. STC Sunyani Needs To Do Better For Passengers! 2023. Available online: https://www.modernghana.com/news/1211936/stc-sunyani-needs-to-do-better-for-passengers.html (accessed on 30 July 2023).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).