1. Introduction

Canine distempers are one of the most significant diseases in veterinary neurology due to their high morbidity, mortality, and neurological sequelae in domestic dogs [

2,

3,

4,

5]. The virus is transmitted primarily through aerosolized viral particles from infected secretions [

6,

7]. Traditionally, Canine Distemper Virus (CDV) was thought to affect dogs regardless of age, sex, or breed [

8].

The frequency of infected dogs associated with risk factors, and the most common clinical manifestations remain poorly characterized. Clinical signs of CDV infection can include respiratory, gastrointestinal, ophthalmologic, dermatologic, and neurological signs [

9,

10]. While neurological involvement is common, it is not exclusive to CDV infection [

11,

12]. Diagnosis is based on clinical history, physical examination, and complementary tests, including blood and urine analysis, cerebrospinal fluid evaluation, and PCR antigen testing [

13].

No specific therapeutic protocol is available for CDV, and approximately 89% of dogs that develop severe clinical signs either die or are euthanized, particularly in cases involving the nervous system [

10]. Epidemiological studies can improve disease control and treatment strategies [

14]. This study aimed to identify epidemiological trends and risk factors associated with CDV-related neurological manifestations.

2. Materials and Methods

A retrospective analysis of medical records from the Neurology and Neurosurgery Service of the Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital at the Federal University of Goiás was conducted. Cases were selected from January 2018 to December 2022 and categorized into distemper group (DG) or control group (CG). The DG comprised dogs with neurological signs confirmed via immunochromatographic antigen testing, RT-PCR, and/or the identification of Lentz corpuscles. The CG includes dogs with central nervous system (CNS) conditions but testing negative for CDV or not considered a differential diagnosis, such as in patients with peripheral nervous system disorders. Dogs with incomplete medical records or exhibiting clinical and/or laboratory indications of distemper that were not subjected to molecular testing were excluded from the study.

Data collected of signalment (age, breed, weight, sex, and neutering status) were extracted from the medical records of both groups. Neurological signs in DG cases were categorized based on neurolocalization (forebrain, brainstem, cerebellum, spinal cord, or multifocal). Extra-neural signs were also recorded. Seasonal trends were analyzed based on the onset of clinical signs. Finally, vaccination protocols for core vaccines recommended by WSAVA [

15] were reviewed. The protocol was classified as either updated (prime vaccination and annual booster) or outdated (absence of prime vaccination or annual booster) as usually practiced in Latin America [

16].

The prevalence of CDV was determined by calculating the ratio of the number of dogs with a confirmed diagnosis to the total population of interest that visited the veterinary service during the study period, restricted to individuals who met the predefined inclusion criteria. Mortality was calculated by dividing the number of animals that died by the total number of animals included in the study. Lethality was calculated by dividing the number of dogs that died by the total number of infected animals (DG). Kaplan-Meier survival was calculated.

The results were subjected to logistic regression analysis using the R software, with a significance level set at 0.05. The log-likelihood method was employed to estimate the parameters, and odds ratios were utilized to identify the influence of each predictor variable that best explained the occurrence of CD. Additionally, death, age, neuter status, breed, and sex were tested to see if they had a normal distribution and then organized in a binomial model to text if the death was influenced by the other factors.

3. Results

Of 412 dogs with CNS disorders, 12.38% (51/412) were excluded due to suspected CDV infection without confirmatory testing, and one case (0.24%) was excluded due to incomplete records. A total of 360 cases met the inclusion criteria, with 5.20% (17 dogs) assigned to the DG and 94.80% (343 dogs) to the CG. Diagnoses in the DG were confirmed by immunochromatography (3 cases), RT-PCR (13 cases), and Lentz corpuscle identification (1 case). The estimated prevalence of CDV at the Neurology and Neurosurgery Service was 4.72%. Epidemiological data for both groups are summarized in

Table 1 and

Table 2.

Neurological signs were observed in all 17 DG cases (

Table 3), with 76.47% (n=13) presenting paresis or plegia. Other common signs included altered mental state (47.06%), seizures (41.18%), and myoclonus (35.29%). Lesions were most frequently multifocal (59%), followed by forebrain (29%) and spinal cord (12%) involvement. Extra-neural signs were documented in 94.12% of the cases, predominantly gastrointestinal (41.11%), dermatological (23.52%), and respiratory (11.76%). Systemic signs occurred before the onset of neurological signs in 29.41% of cases, after in 35.29%, and simultaneously in 11.76%. The remaining 23.52% lacked timeline data.

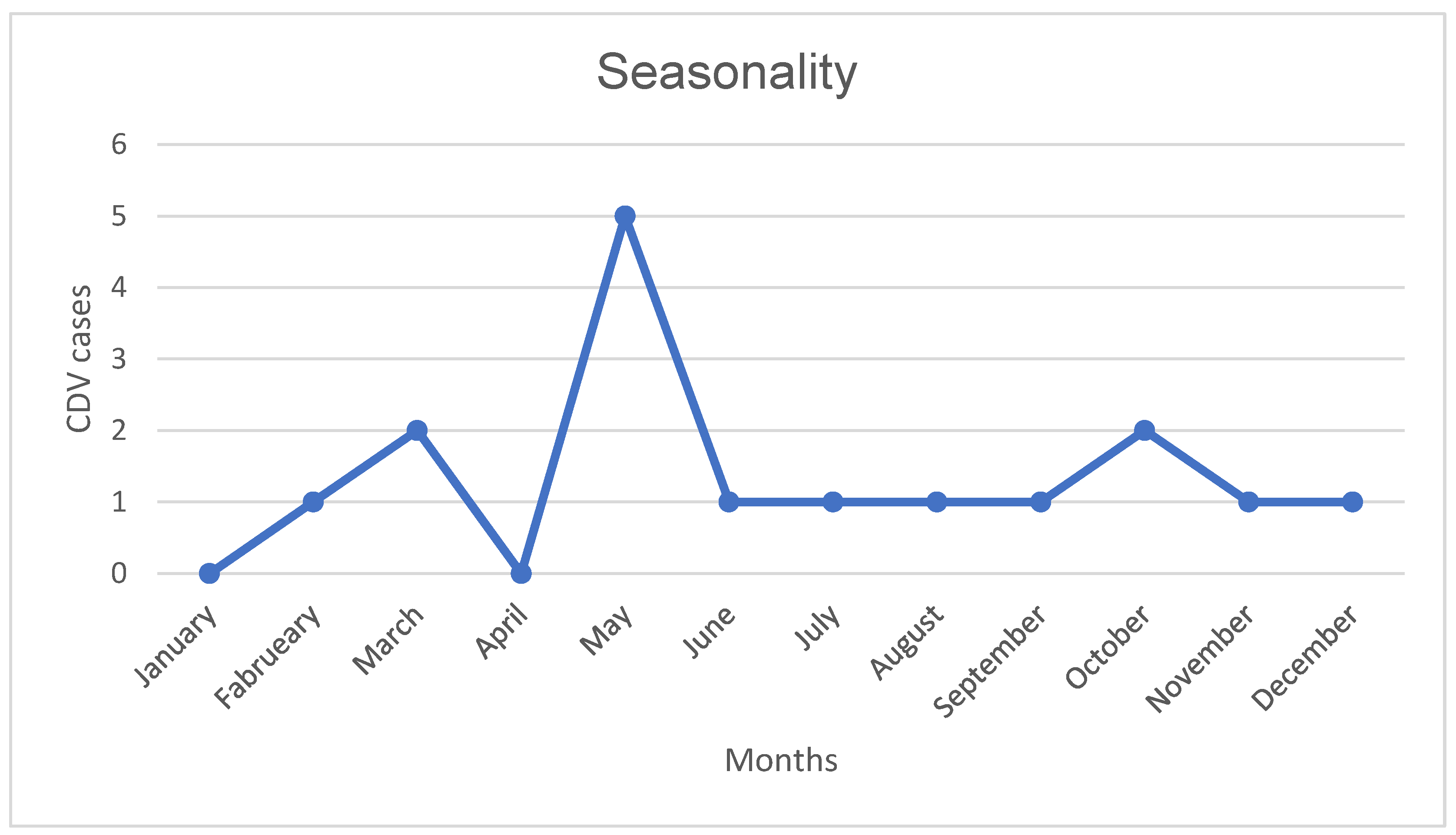

Neurological signs onset peaked in May, with autumn as the most common season (41.18%) (

Figure 1). Vaccination protocols were up-to-date in 35.29% (n=6) of DG cases, outdated in another 35.29%, and unavailable in 29.41%.

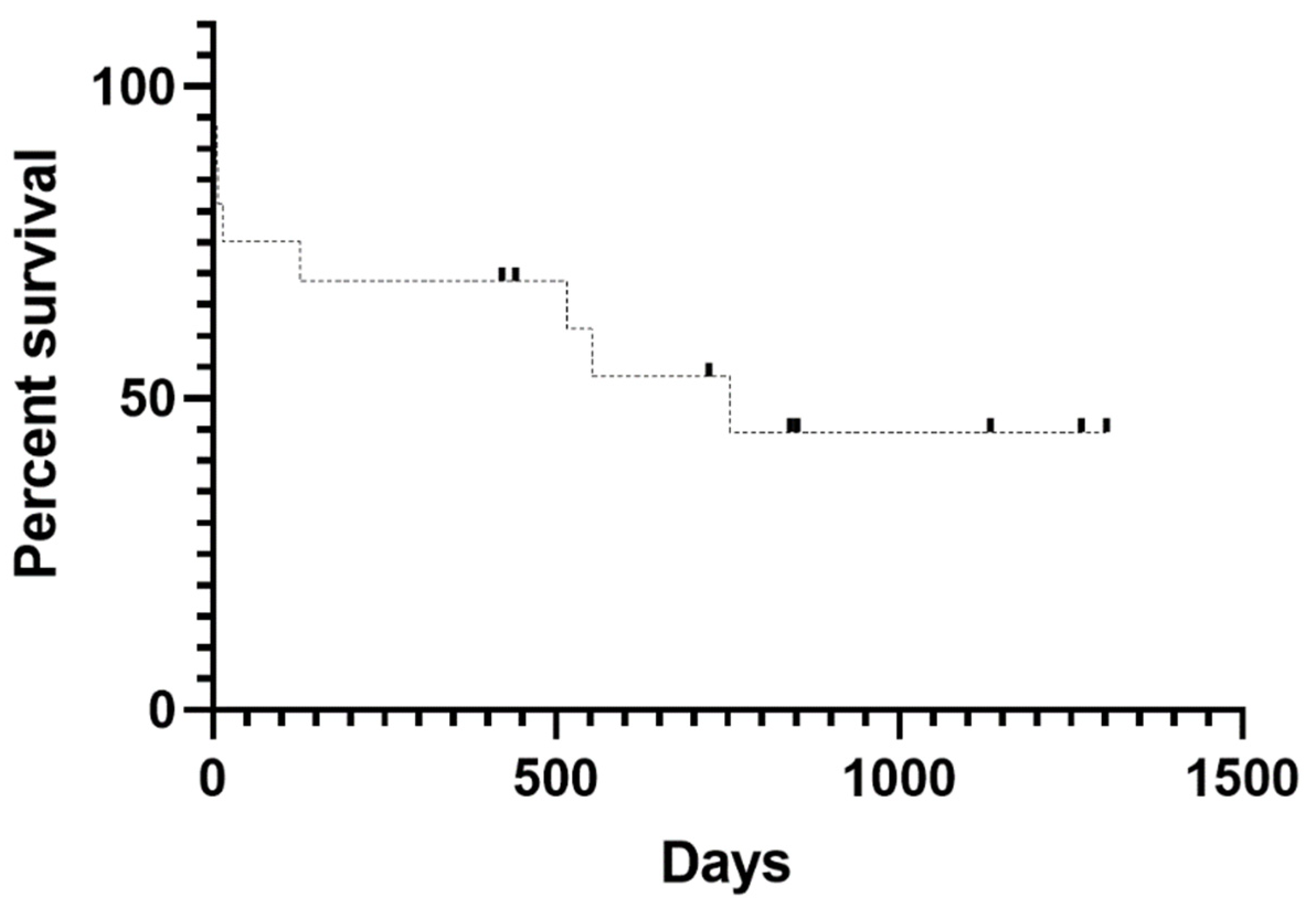

Mortality was 1.94% (8/412), and lethality within the DG was 47.06% (8/17). Median survival time was 754 days (

Figure 2). Of the eight deaths, four occurred during the acute phase, three during the chronic phase due to neurological sequelae, and one had an undocumented cause. Mortality was not significantly associated with sex, age, breed, or neutering status.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrated that young adult dogs and specific breeds, namely Shih-Tzu and Lhasa Apso, are at higher risk of developing neurological manifestations of CDV. Seasonal clustering was also evident, with a higher incidence of cases in autumn.

Although CDV is endemic in canine populations worldwide [

7,

17,

18,

19], few studies have focused on neurological manifestations and associated epidemiological risk factors. Our findings show a prevalence of neurological CDV of 4.72%, similar to previously reported CDV prevalence in general canine populations [

8,

14,

19,

20].

Despite a lethality rate of 47.06%, our study's overall mortality (1.94%) was lower than prior reports in the same region [

21], potentially due to the specialized neurological care available at our center. This underscores the benefit of targeted care in managing CDV-related complications.

Significantly, this study is the first to identify statistical associations between specific breeds and the likelihood of developing neurological CDV. Prior literature has often cited a high prevalence of CDV in mixed-breed dogs, likely reflecting broader environmental and socioeconomic factors rather than genetic susceptibility [

9,

20,

21]. Our controlled comparison supports a genuine predisposition in Shih-Tzu and Lhasa Apso.

Age also played a role, with younger dogs more likely to develop CDV. However, one case involved a 10-year-old, reinforcing that age alone is insufficient to rule out CDV infection.

No significant associations were observed between neurological CDV and sex, weight, or neuter status, aligning with previous findings. An earlier study noted a possible link between obesity and seropositivity for CDV [

8], but this may reflect confounding factors such as immunologic memory or non-specific ELISA results.

Regarding clinical presentation, motor deficits were the most common neurological manifestation. Interestingly, myoclonus was less prevalent than in previous studies [

21,

22]. This is supported by previous findings where myoclonus was more frequently observed in dogs negative for distemper than in those positive for the disease [

14], suggesting it should not be considered pathognomonic for CDV. Multifocal CNS involvement was common, with relatively rare cerebellar signs. The possibility of subclinical cerebellar involvement should not be excluded in positive cases [

9,

21].

The timing of systemic vs. neurological signs varied, with no consistent progression identified. This variation complicates early diagnosis and highlights the importance of a thorough clinical work-up. The seasonal clustering observed in autumn aligns with literature suggesting increased CDV stability in colder temperatures and reduced host immunity during this period [

23].

It is notable that over one-third of neurologically affected dogs had up-to-date vaccinations. This raises critical concerns regarding vaccine efficacy. Potential causes include antigenic mismatch, host-related factors, or waning immunity, potentially linked to antigenic drift among circulating wild-type CDV strains, or outdated vaccine formulations [

3,

24]. Previous studies have documented polymorphisms in circulating CDV strains that may impact vaccine efficacy [

10].

Limitations of this study include its retrospective design, reliance on available medical records, and the exclusion of suspected cases without molecular confirmation. Nonetheless, our findings provide novel insights into the epidemiology of neurological CDV.

5. Conclusions

The findings of this study underscore that distemper remains a significant concern for canine health, with high prevalence and mortality rates in affected animals. This highlights the importance of conducting epidemiological research and investigating the causes of vaccine failures. Furthermore, it emphasizes the need for discussions among professionals to establish standard operational protocols and with dog owners to stress the importance of mass prevention. Our findings underscore the importance of breed- and season-specific preventive strategies and advocate for further studies on vaccine performance and strain variability in CDV.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Bruno, methodology, Bruno, Heloisa and Luana; validation, Bruno and Luana; formal analysis, Bruno, Heloisa, Luana and Paulo; investigation, Bruno, Heloisa and Luana; resources, Bruno; data curation, Heloisa and Luana; writing—original draft preparation, Ítalo, Heloisa, and Luana; writing—review and editing, Bruno and Luana; supervision, Bruno and David; project administration, Bruno. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the reported results of this study are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions. The data were collected from medical records of patients treated at a hospital and are owned by the respective animal owners and the institution. Access to the data can be granted upon request, subject to approval from the relevant ethical and legal authorities, in accordance with confidentiality agreements and privacy policies. For further information, please contact the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CDV |

Canine distemper virus |

| CG |

Control group |

| CNS |

Central nervous system |

| DG |

Distemper group |

| PCR |

Polymerase chain reaction |

| RT-PCR |

Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction |

References

- Torres, B.B.G.; Iara, Í.H.N.; Freire, H.I.; Ribeiro, L.S.; Menezes, K.M.; Gonçalves, P.A.; Matta, D.H. Epidemiological Characteristics and Risk Factors Associated with Neurological Manifestation of Canine Distemper Virus. In Proceedings of the ACVIM 2024 Forum; Minneapolis, Minessota, EUA, June 6 2024.

- Elia, G.; Camero, M.; Losurdo, M.; Lucente, M.S.; Larocca, V.; Martella, V.; Decaro, N.; Buonavoglia, C. Virological and Serological Findings in Dogs with Naturally Occurring Distemper. J Virol Methods 2015, 213, 127–130, doi:10.1016/j.jviromet.2014.12.004. [CrossRef]

- Costa, V.G.D.; Saivish, M.V.; Rodrigues, R.L.; Lima Silva, R.F.D.; Moreli, M.L.; Krüger, R.H. Molecular and Serological Surveys of Canine Distemper Virus: A Meta-Analysis of Cross-Sectional Studies. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217594, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0217594. [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, T.; Rajeev, R.; Jha, A.; Kumar, S. Canine Distemper: A Fatal Disease Seeking Special Intervention. J Entomol Zool Stud 2021, 9, 1411–1418.

- Santos, C.; Teles, J.; Es, G.; Gil, L.; Vieira, A.; Junior, J.; Silva, C.; Maia, R. Epitope Mapping and a Candidate Vaccine Design from Canine Distemper Virus. Open Vet J 2024, 14, 1019, doi:10.5455/OVJ.2024.v14.i4.9. [CrossRef]

- Beineke, A.; Puff, C.; Seehusen, F.; Baumgärtner, W. Pathogenesis and Immunopathology of Systemic and Nervous Canine Distemper. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 2009, 127, 1–18, doi:10.1016/j.vetimm.2008.09.023. [CrossRef]

- Kapil, S.; Yeary, T.J. Canine Distemper Spillover in Domestic Dogs from Urban Wildlife. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2011, 41, 1069–1086, doi:10.1016/j.cvsm.2011.08.005. [CrossRef]

- Dorji, T.; Tenzin, T.; Tenzin, K.; Tshering, D.; Rinzin, K.; Phimpraphai, W.; De Garine-Wichatitsky, M. Seroprevalence and Risk Factors of Canine Distemper Virus in the Pet and Stray Dogs in Haa, Western Bhutan. BMC Vet Res 2020, 16, 135, doi:10.1186/s12917-020-02355-x. [CrossRef]

- Martins, B.C.; Torres, B.B.J.; Heinemann, M.B.; Carneiro, R.A.; Melo, E.G. Características epizootiológicas da infecção natural pelo vírus da cinomose canina em Belo Horizonte. Arq. Bras. Med. Vet. Zootec. 2020, 72, 778–786, doi:10.1590/1678-4162-11321. [CrossRef]

- Menezes, K.M.F.; Dábilla, N.; Souza, M.; Damasceno, A.D.; Torres, B.B.J. Identification of a New Polymorphism on the Wild-Type Canine Distemper Virus Genome: Could This Contribute to Vaccine Failures? Braz J Microbiol 2023, 54, 665–678, doi:10.1007/s42770-023-00971-x. [CrossRef]

- Martella, V.; Elia, G.; Buonavoglia, C. Canine Distemper Virus. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2008, 38, 787–797, doi:10.1016/j.cvsm.2008.02.007. [CrossRef]

- Barber, R.M.; Li, Q.; Levine, J.M.; Ruone, S.J.; Levine, G.J.; Kenny, P.; Tong, S.; Schatzberg, S.J. Screening for Viral Nucleic Acids in the Cerebrospinal Fluid of Dogs With Central Nervous System Inflammation. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 850510, doi:10.3389/fvets.2022.850510. [CrossRef]

- Sarchahi, A.A.; Arbabi, M.; Mohebalian, H. Detection of Canine Distemper Virus in Cerebrospinal Fluid, Whole Blood and Mucosal Specimens of Dogs with Distemper Using RT-PCR and Immunochromatographic Assays. Vet Med Sci 2022, 8, 1390–1399, doi:10.1002/vms3.790. [CrossRef]

- Mousafarkhani, F.; Sarchahi, A.A.; Mohebalian, H.; Khoshnegah, J.; Arbabi, M. Prevalence of Canine Distemper in Dogs Referred to Veterinary Hospital of Ferdowsi University of Mashhad Mashhad Iran. Vet Res Forum 2023, doi:10.30466/vrf.2022.541661.3269. [CrossRef]

- Squires, R.A.; Crawford, C.; Marcondes, M.; Whitley, N. 2024 Guidelines for the Vaccination of Dogs and Cats – Compiled by the Vaccination Guidelines Group (VGG) of the World Small Animal Veterinary Association (WSAVA). J Small Anim Pract 2024, 65, 277–316, doi:10.1111/jsap.13718. [CrossRef]

- Day, M.J.; Crawford, C.; Marcondes, M.; Squires, R.A. Recommendations on Vaccination for Latin American Small Animal Practitioners: A Report of the WSAVA Vaccination Guidelines Group. J Small Anim Pract 2020, 61, doi:10.1111/jsap.13125. [CrossRef]

- Trebbien, R.; Chriel, M.; Struve, T.; Hjulsager, C.K.; Larsen, G.; Larsen, L.E. Wildlife Reservoirs of Canine Distemper Virus Resulted in a Major Outbreak in Danish Farmed Mink (Neovison Vison). PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e85598, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0085598. [CrossRef]

- Oleaga, Á.; Vázquez, C.B.; Royo, L.J.; Barral, T.D.; Bonnaire, D.; Armenteros, J.Á.; Rabanal, B.; Gortázar, C.; Balseiro, A. Canine Distemper Virus in Wildlife in South-Western Europe. Transbound Emerg Dis 2022, 69, e473–e485, doi:10.1111/tbed.14323. [CrossRef]

- Van, T.M.; Le, T.Q.; Tran, B.N. Phylogenetic Characterization of the Canine Distemper Virus Isolated from Veterinary Clinics in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam. Vet World 2023, 1092–1097, doi:10.14202/vetworld.2023.1092-1097. [CrossRef]

- Headley, S.A.; Graça, D.L. Canine Distemper: Epidemiological Findings of 250 Cases. Braz. J. Vet. Res. Anim. Sci. 2000, 37, 00–00, doi:10.1590/S1413-95962000000200009. [CrossRef]

- Menezes, K.M.F.; Filho, G.D.D.S.; Damasceno, A.D.; Souza, M.; Torres, B.B.J. Epizootiology of Canine Distemper in Naturally Infected Dogs in Goiânia, Brazil. Cienc. Rural 2023, 53, e20220166, doi:10.1590/0103-8478cr20220166. [CrossRef]

- Koutinas, A.F.; Polizopoulou, Z.S.; Baumgaertner, W.; Lekkas, S.; Kontos, V. Relation of Clinical Signs to Pathological Changes in 19 Cases of Canine Distemper Encephalomyelitis. Journal of Comparative Pathology 2002, 126, 47–56, doi:10.1053/jcpa.2001.0521. [CrossRef]

- Headley, S.A.; Amude, A.M.; Alfieri, A.F.; Bracarense, A.P.F.R.L.; Alfieri, A.A. Epidemiological Features and the Neuropathological Manifestations of Canine Distemper Virus-Induced Infections in Brazil: A Review. Sem. Ci. Agr. 2012, 33, 1945–1978, doi:10.5433/1679-0359.2012v33n5p1945. [CrossRef]

- Da Fontoura Budaszewski, R.; Streck, A.F.; Nunes Weber, M.; Maboni Siqueira, F.; Muniz Guedes, R.L.; Wageck Canal, C. Influence of Vaccine Strains on the Evolution of Canine Distemper Virus. Infect Genet Evol 2016, 41, 262–269, doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2016.04.014. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).