1. Introduction

The global demand for renewable energy sources with high energy density, low intermittency, and reduced environmental impact has intensified the search for new approaches to energy conversion. Among the available natural sources, ocean currents represent a vast, yet largely untapped potential [

1], characterized by physical properties that fundamentally distinguish them from other energy-generating flows, such as wind and channeled river streams.

Technologies currently applied to energy generation from marine currents are largely derived from wind turbines, whose principles were originally conceived for low-density, compressible fluids. However, the ocean—being a nearly incompressible and highly dense medium—responds differently to the presence of energy conversion devices. This fundamental difference necessitates the development of new theoretical models that consider the continuous, dense, and dynamically restored nature of marine flows.

International reports highlight the growing global interest in the sustainable exploitation of ocean currents as a renewable energy source [

2].

In this context, the Energy Restoration by Planetary Fields (ERPF) theory is proposed, conceiving ocean currents as open energy systems, generated and sustained by planetary field forces such as gravity, Earth's rotation, thermal and salinity gradients, and atmospheric pressure. These forces act continuously, not only maintaining the motion of large water masses but also serving as the fundamental cause of their formation and dynamics [

3], ensuring the constant replenishment of global kinetic energy even after local energy capture. This characteristic sets marine currents apart from other natural systems, enabling a new understanding of the nature of energy available in such flows.

Based on this theory, the Current Energy Collecting Unit (UCEC, from the Portuguese "Unidade Coletora de Energia de Corrente") is introduced: an innovative submerged turbine specifically designed to operate in resonance with marine flows. The UCEC converts the fluid's linear momentum into mechanical torque by imposing a 90-degree vectorial deflection on the velocity vector along the turbine blades. This unique geometry enables efficient dynamic coupling between structure and flow, preserving the integrity of the ocean's global movement and paving the way for a new class of sustainable, effective, and regenerative technologies.

2. Physical Foundations

The Energy Restoration by Planetary Fields (ERPF) theory proposes a new understanding of oceanic flows, treating them as open energy systems whose moving masses are generated and sustained by natural mechanisms operating at a planetary scale. In contrast to classical models that focus on the kinetic energy incident at a point within the flow, the ERPF framework considers the integrated dynamics of large volumes of incompressible water, whose high density and volumetric stability confer a collective and persistent behavior to the ocean.

Although planetary field forces are individually small at the scale of a single particle, their cumulative effect over vast oceanic masses generates a significant and continuous restoration of linear momentum. This phenomenon can be compared to the alignment of countless magnetic dipoles under the influence of a weak magnetic field: while the force acting on each individual element is minimal, the sum of these forces across an enormous number of elements produces a substantial macroscopic effect. In the context of ocean currents, the combined action of gravity, Earth's rotation, and thermal and salinity gradients ensures that any localized extraction of energy represents only a minute fraction of the total linear momentum of the flow, which is almost immediately restored by the persistent action of these fields.

To understand how the kinetic energy of currents can be continuously restored, it is essential to consider the physical properties of the oceanic medium. The incompressible nature of water plays a fundamental role in this process, allowing local perturbations without compromising the global dynamics of the flow.

Unlike air—a compressible fluid subject to fluctuations in pressure and density—seawater maintains its volumetric integrity even under variations in depth, velocity, or pressure [

4]. This incompressibility ensures the continuity of oceanic flow even after local perturbations, enabling energy extraction without significantly affecting its global behavior. In contrast, wind energy conversion relies on the deceleration of air as it passes through a turbine—a reduction in velocity made possible by the compressibility of air to conserve mass. However, this principle is incompatible with seawater: since seawater does not admit significant compression, mass conservation prevents its local velocity from being reduced without causing accumulation, a physically unfeasible condition. This fundamental difference invalidates the direct application of models based on flow deceleration and demands new approaches that respect the properties of an incompressible medium.

It is assumed that any energy locally extracted is promptly replenished by the continuous action of planetary field forces, ensuring the ongoing presence of kinetic energy within the flow. This characteristic enables efficient energy conversion, provided that the technology employed respects the physical coupling with the medium, minimizing disturbances and irreversible dissipations.

This behavior justifies the introduction of a new paradigm for energy conversion in fluid dynamic systems: instead of focusing exclusively on the cross-sectional area of the flow and the locally incident kinetic energy, it is proposed to consider the volumetric continuity and the natural, constant replenishment of energy. The ERPF theory thus breaks with the conceptual limits established by classical models—such as the Betz limit [

5]—and opens the way for new interpretations of the performance of hydrokinetic systems in natural environments.

3. Theoretical Model of the ERPF

The theoretical formulation of the Energy Restoration by Planetary Fields (ERPF) theory begins with the recognition that the ocean, as an incompressible fluid system operating in a steady-state regime, presents an energy availability that transcends the limitations of local approaches. The global movement of oceanic masses is both originated and continuously sustained by planetary field forces, including gravity, Earth's rotation, and thermal and salinity gradients.

Rather than treating the available energy as confined solely to the impact front of a turbine or a specific section of the flow, the ERPF framework proposes considering the entire moving mass volume as a reservoir of kinetic energy that is continuously restored by these natural mechanisms.

The theoretically available power for conversion can be expressed by:

where represents the kinetic energy contained within a water volume , and is the time interval considered for the conversion. In the theoretical limit where energy replenishment occurs immediately after extraction—as predicted by the continuous action of planetary forces—time tends toward zero, and the resulting power would theoretically tend toward infinity. However, in reality, the energy replenishment rate is finite, constrained by the intensity and spatial distribution of the restoring forces, thus making the available power high but physically limited. Nevertheless, this scenario highlights the virtually inexhaustible nature of oceanic energy when the system is considered as a whole.

Conversely, the fraction of energy effectively converted will depend on the efficiency of the interaction between the conversion device and the flow. The extracted shaft power of the turbine, for instance, can be described by:

where τ is the torque applied to the shaft, ω is the angular velocity of rotation, and is the total geometric efficiency factor of the system, which accounts for friction losses, structural dissipations, and limitations in coupling with the flow.

To evaluate the performance of a system based on the ERPF paradigm, a dimensionless index κ is proposed, defined as:

Where represents an idealized power level sustained by the natural system. Since it involves a system restored by external forces, it is expected that κ < 1, reflecting inherent conversion losses but complementing the traditional power coefficient commonly used in wind turbines. The index κ thus serves as an intrinsic efficiency metric for mechanical conversion, independent of the locally incident kinetic energy.

This theoretical approach establishes the foundations for understanding marine energy systems as dynamically balanced restored flows, proposing a new conceptual framework for analyzing available power and efficiency in devices designed to operate in resonance with the environment.

4. Geometry of the UCEC as a Technological Solution

The Current Energy Collecting Unit (UCEC) was developed as a response to the limitations of models inherited from wind engineering, by adopting an original geometric approach to energy conversion in incompressible fluids.

Its design is based on direct vectorial interaction with oceanic flow: rather than exploiting attack angles or pressure gradients, the UCEC converts the linear momentum of the current through controlled angular deflection along the blades.

The following sections present the main elements of this innovative geometry, highlighting its three-dimensional representation, construction criteria, operational principles in resonance with the flow, and environmental features, including compatibility with marine fauna and the regenerative potential of the ecosystem.

4.1. Geometric Representation of the UCEC

The geometry of the UCEC is designed to ensure the integral vectorial conversion of oceanic flow into torque, while maintaining the integrity of the flow and maximizing the interaction between fluid and structure.

Two complementary approaches are presented below to illustrate the characteristics of this innovative geometry:

4.1.1. Vectorial Curvature and Fluid Trajectory

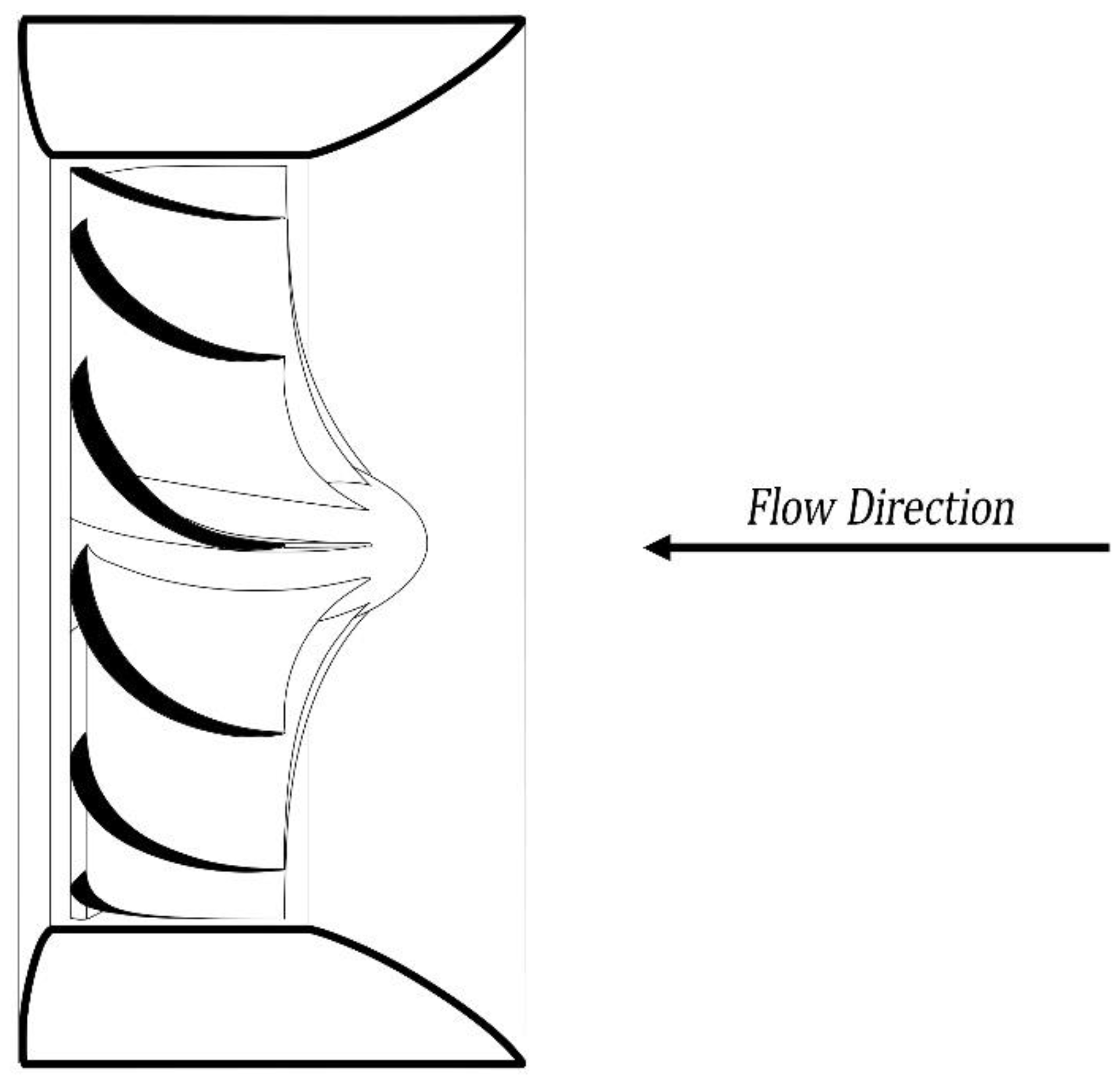

The following figures, extracted from the U.S. patent US 12,168,969 B2 [

6], demonstrate:

The vectorial curvature imposed on the flow by each blade;

The 90° angular deflection along the blade profiles;

The adaptation of the flow into the turbine's internal format.

As described in the patent, the choice of rotation direction is a design decision without impact on energy conversion efficiency. Once defined, the UCEC rotor operates unidirectionally and is not reversible. In the event of a flow reversal, the turbine structure is designed to passively realign itself, maintaining the correct orientation facing the incoming current.

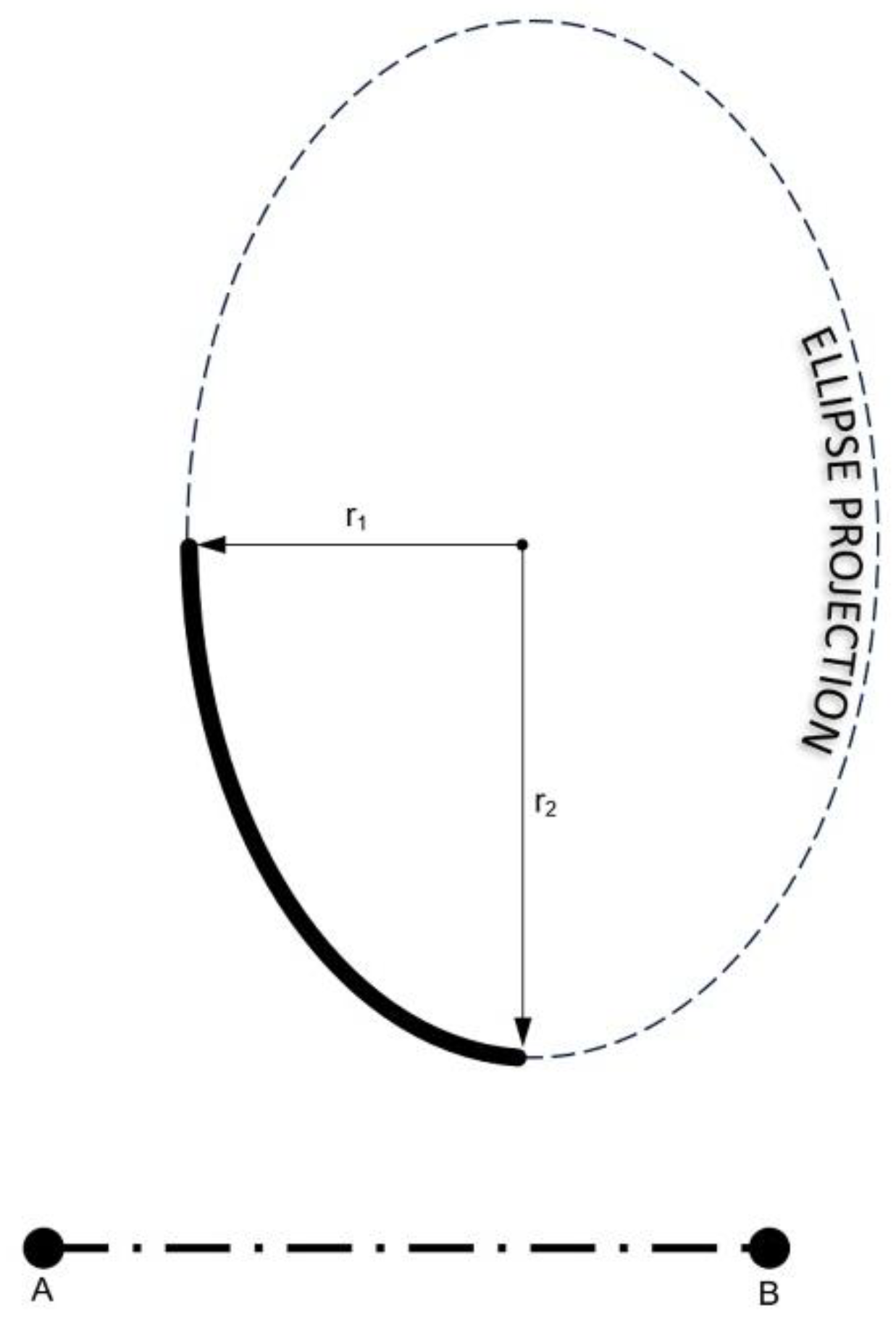

Figure 4.

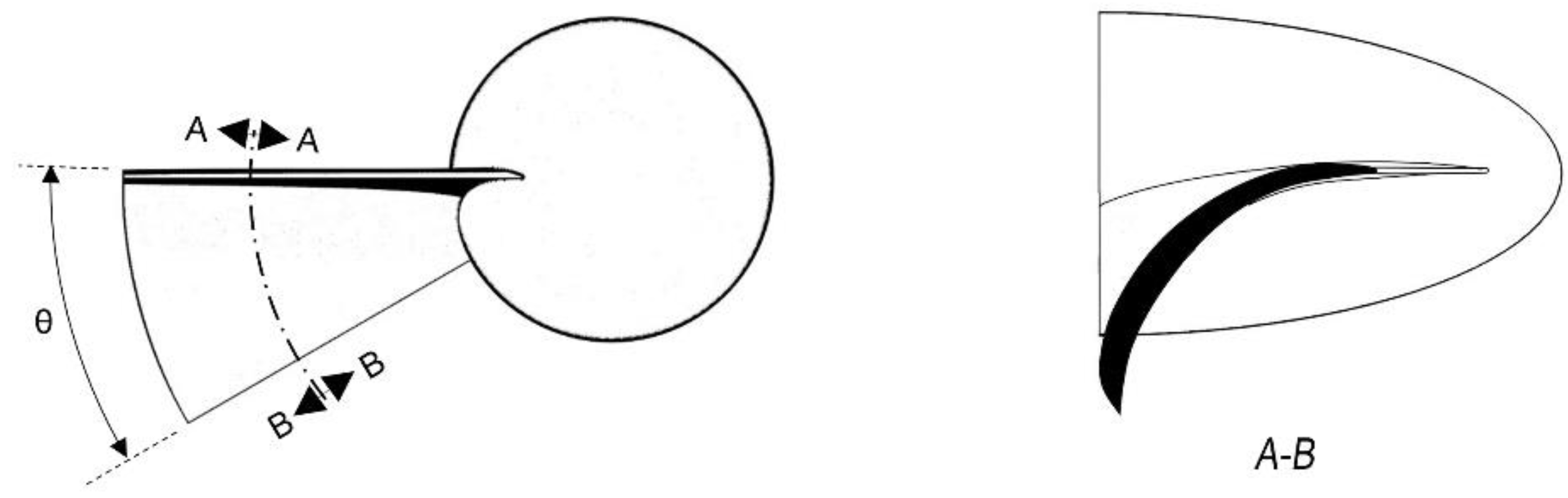

Elliptical projection highlighting the 90° deflection as an idealized fluid trajectory under resonant rotation.

Figure 4.

Elliptical projection highlighting the 90° deflection as an idealized fluid trajectory under resonant rotation.

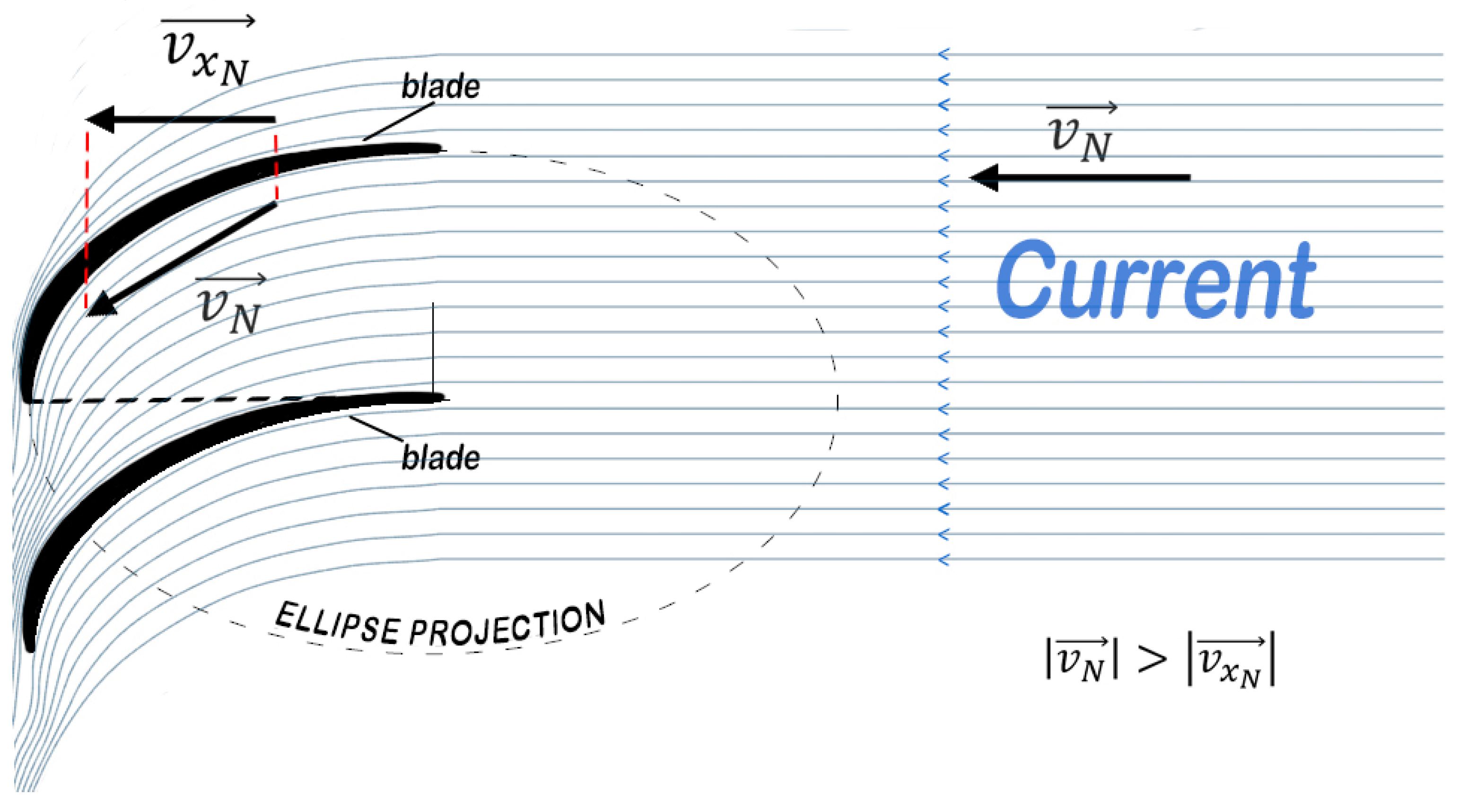

In addition to three-dimensional visualizations, the following figure illustrates, in a plan view, the vectorial behavior of the flow along the UCEC blades.

The curvature imposed on the velocity vector and its decomposition into an orthogonal component are observed, highlighting the moment transfer mechanism characteristic of the turbine geometry.

This graphic representation facilitates the understanding of the flow trajectory within the rotor, emphasizing the continuous adaptation of the flow to the blade configuration.

Figure 5.

Plan view scheme showing the vectorial deflection imposed by the UCEC blades. The 90° curvature of the flow is evidenced by the decomposition of the velocity vector , emphasizing the principle of vectorial energy conversion.

Figure 5.

Plan view scheme showing the vectorial deflection imposed by the UCEC blades. The 90° curvature of the flow is evidenced by the decomposition of the velocity vector , emphasizing the principle of vectorial energy conversion.

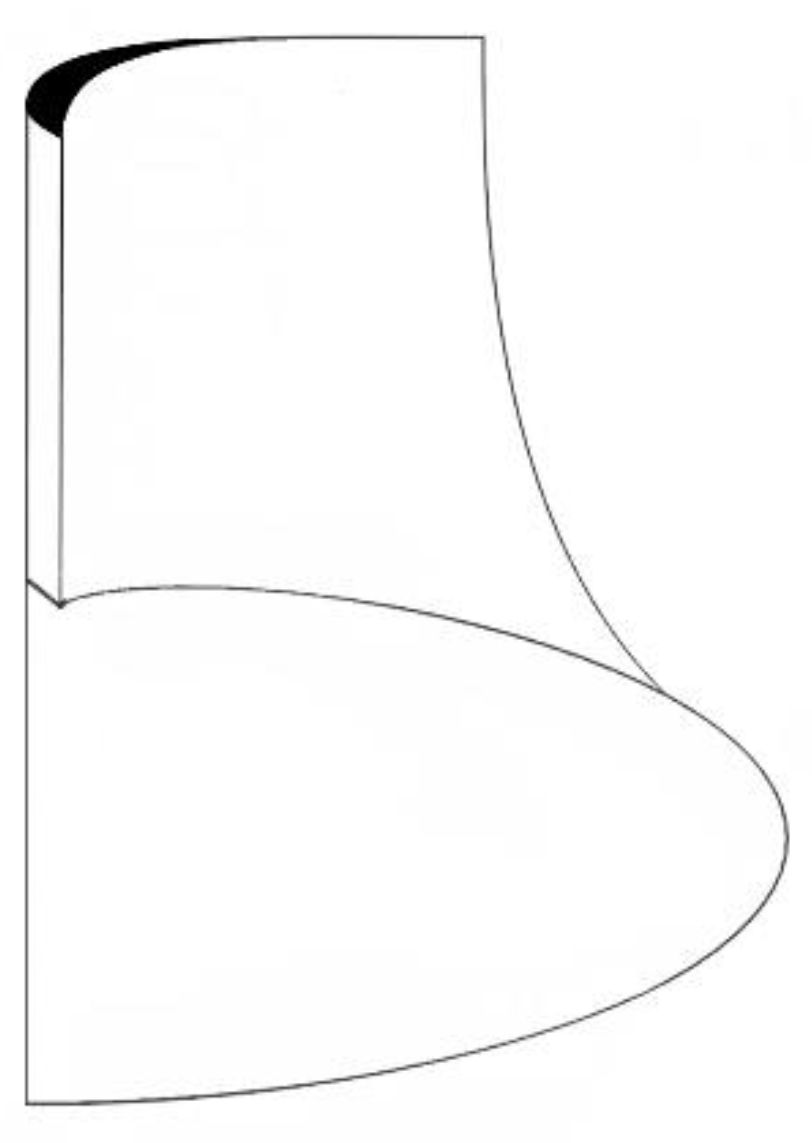

4.1.2. Full Occupation and Venturi Effect

The geometry of the UCEC is designed to maximize the vectorial conversion of oceanic currents into torque, ensuring the complete utilization of the incident flow.

To achieve this goal, the blades are evenly distributed around the central hub, fully occupying the useful cross-sectional area of the turbine [

7]. The number of blades may vary according to the design, but each blade occupies an equal angular arc, so that the sum of all blade openings corresponds to 360 degrees—forming a closed mesh of vectorial deflection.

This configuration ensures that any volume of water crossing the turbine section must necessarily interact with the blades, promoting the efficient transfer of the flow’s linear momentum to the rotational axis.

Additionally, the external duct presents a gradual convergence toward the active region of the turbine, promoting a Venturi effect [

8] that accelerates the flow as it approaches the blades. This directed acceleration enhances the fluid-structure interaction and improves hydraulic coupling, concentrating the energy conversion work within the active area.

The following figures illustrate these geometric characteristics:

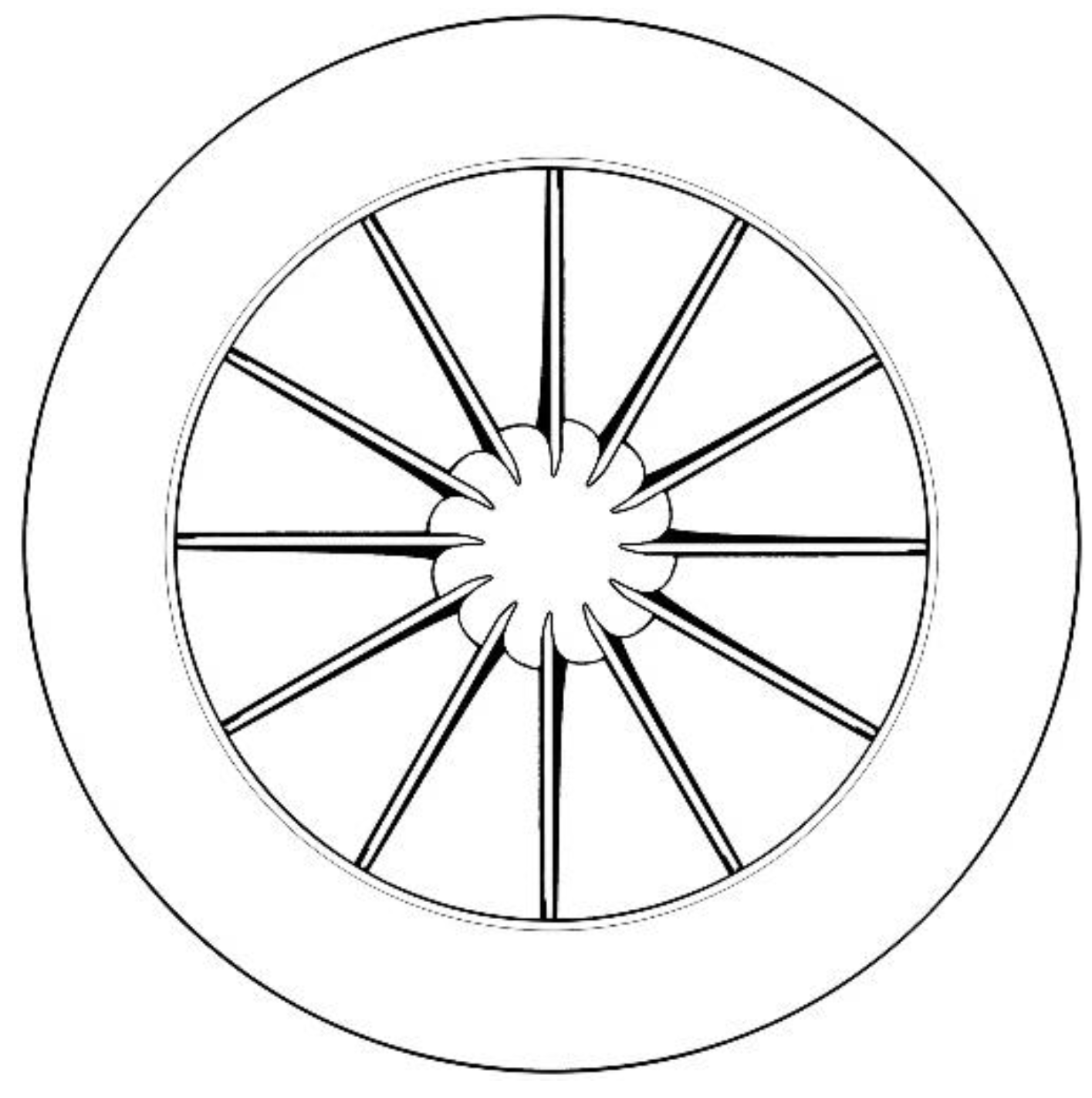

Figure 6.

Frontal view of the UCEC, showing the total occupation of the cross-sectional area by blades in a continuous angular distribution.

Figure 6.

Frontal view of the UCEC, showing the total occupation of the cross-sectional area by blades in a continuous angular distribution.

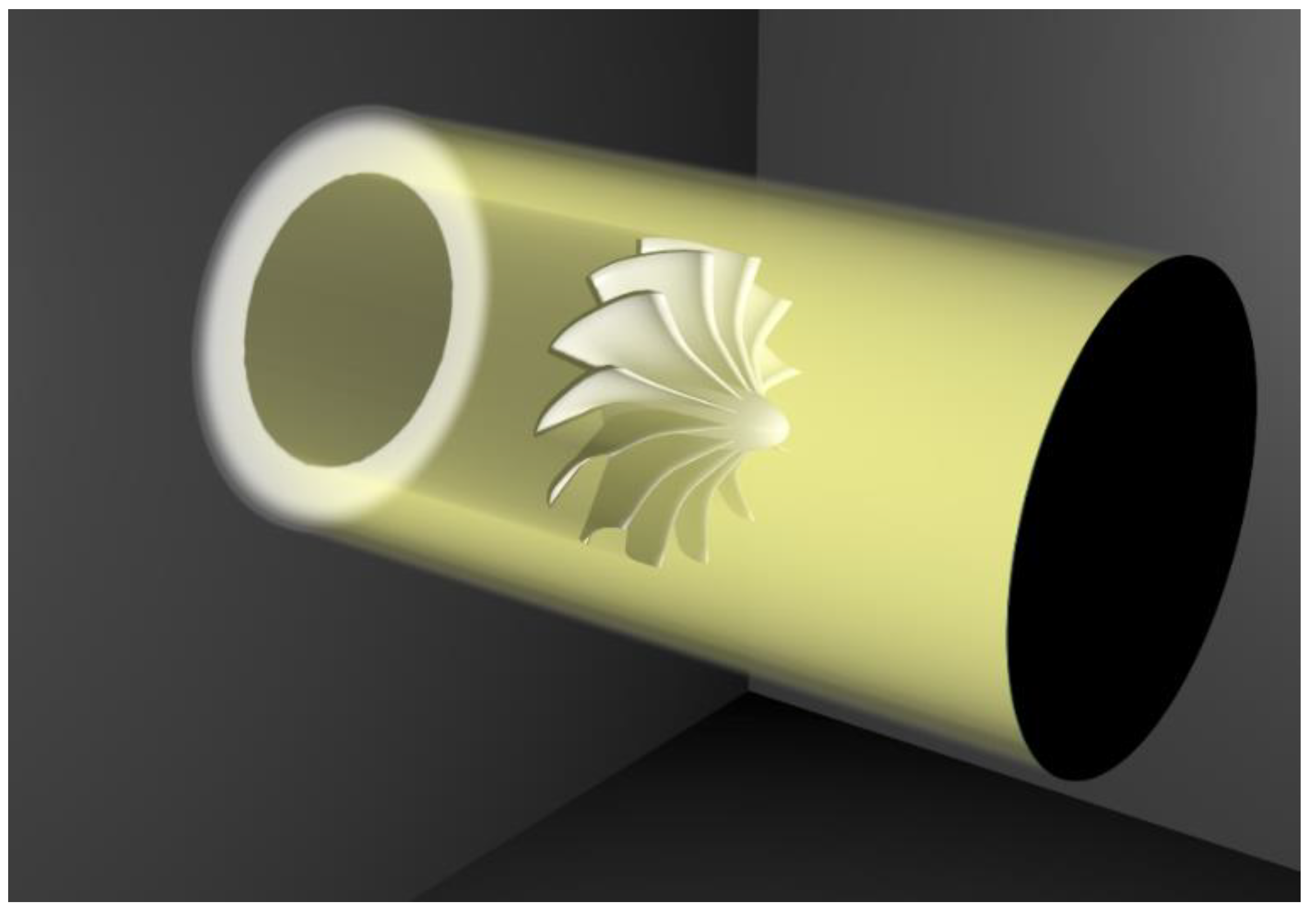

Figure 7.

Three-dimensional rendering simulating a parallel light beam projected over the rotor, with the shadow evidencing the absence of bypass zones.

Figure 7.

Three-dimensional rendering simulating a parallel light beam projected over the rotor, with the shadow evidencing the absence of bypass zones.

4.2. Structural Characteristics

The Current Energy Collecting Unit (UCEC) was designed with a focus on structural robustness, durability in marine environments, and modularity for simplified maintenance. Although the final selection of materials and components is still under optimization, the proposed design involves the use of corrosion-resistant metal alloys, high-performance composite materials, and construction solutions that allow scalable manufacturing.

The structural development of the UCEC was also guided by the recommended practices for maritime operations modeling and analysis established by DNV-GL [

9].

The turbine body and its convergent duct are designed to withstand significant hydrodynamic loads, ensuring stability during continuous operation in ocean currents.

The rotor, composed of blades with three-dimensional vectorial curvature, will be mounted on a main shaft coupled to low-friction bearings, with sealing systems adapted for submerged operation.

The modularity of the assembly aims to facilitate field disassembly for inspections and component replacement, reducing operational costs and increasing the feasibility of the technology on a large scale.

The system will be designed to allow integration with various types of electric generation platforms, whether floating or fixed, adapting to the installation requirements of different coastal and oceanic environments.

4.3. Resonant Operation and Generated Torque

The UCEC operates based on a dynamic coupling principle between the vectorial curvature imposed on the flow and the rotation of the turbine’s hub.

This coupling is made possible because the blades induce a significant deflection in the flow’s velocity vector, generating reactive forces distributed tangentially along the circular paths described by the blades around the shaft.

The composition of these forces results in a net torque that drives the hub’s rotation and transmits power to the shaft.

The rotation, in turn, modifies the interaction between the flow and the blade surfaces. In an ideal scenario without resistance to motion, the fluid would adjust perfectly to the geometry of the blades, following their curved trajectory in the blades’ own reference frame. However, in the fixed reference frame, the flow would maintain its rectilinear trajectory, undergoing no effective deflection and therefore generating no significant reactive force.

When connected to an electrical generator or other load system, however, the UCEC encounters resistance to rotation.

This resistance prevents the rotor from fully following the natural trajectory of the flow, and it is precisely this difference between ideal and actual motion that generates effective deflection of the flow, promoting energy transfer in the form of torque.

This behavior establishes a condition of operational resonance: the turbine rotates in synchrony with the flow dynamics but in a regime where the angular deflection of the flow is partially dissipated as shaft torque.

The more efficient this coupling between the turbine geometry and the current regime, the greater the generated torque and the higher the extracted power.

This continuous vectorial conversion—with minimal disturbance to the flow and maximum transfer of linear momentum to the shaft—distinguishes the UCEC from all other hydrokinetic or wind turbines.

By operating in resonance with the medium, the turbine minimizes losses from turbulence, stagnation, or vortex formation, achieving an ideal energy extraction regime fully compatible with the principles of the ERPF theory.

4.4. Environmental Compatibility and Marine Fauna Interaction

Studies on the environmental effects of marine energy highlight that low-intrusion devices, such as the UCEC, can minimize impacts on marine fauna [

10].

The geometry of the UCEC also offers remarkable environmental advantages, both in the way it interacts with the flow and through the positive effects it can induce within marine ecosystems.

Unlike traditional turbines with thin blades and aggressive attack angles—which slice through the fluid during rotation and pose collision risks to marine organisms—the UCEC features a continuous distribution of blades with harmonic vectorial curvature.

This configuration creates a coherent movement effect between the water and the structure: inside the turbine, the fluid rotates along with the rotor, as if the volume of water were being carried by a rotating field.

Thus, for organisms located within the turbine’s active section—such as fish—the movement of the blades becomes imperceptible, drastically reducing the risk of impact.

This characteristic is particularly relevant for the preservation of marine fauna, as it allows energy conversion to occur without imposing abrupt physical barriers or creating zones of intense shear within the flow.

Moreover, the UCEC’s support and anchoring structures—whether fixed or floating—offer potential for acting as artificial reefs [

11].

As observed with shipwrecks or purposefully submerged structures, these bases can become substrates for the colonization of benthic organisms and fish, contributing to the regeneration of local biodiversity [

12].

These properties make the UCEC not only an energy-efficient turbine but also a regenerative technology, capable of uniquely integrating energy production with environmental conservation within the hydrokinetic sector.

5. Experimental Validation and Technological Projections

The Energy Restoration by Planetary Fields (ERPF) theory will be tested through laboratory experiments using the Current Energy Collecting Unit (UCEC) in a controlled environment that simulates the dynamics of ocean currents.

These experiments aim to verify whether the UCEC’s geometry, combined with the hypothesis of continuous energy replenishment by planetary field forces, enables efficient conversion of the mechanical energy of the flow into shaft torque.

The tests will be conducted in an elongated tank filled with still water. The UCEC will be mounted on a mobile structure (dynamometric carriage) traveling over side rails, propelled by electric motors operating at controlled speeds. This movement generates a relative flow between the water and the turbine, simulating realistic conditions of a steady ocean current.

During the experiments, constant carriage speeds will be maintained, and different rotational speeds of the turbine will be tested.

The power delivered by the motors to the moving system will be recorded and compared with the mechanical power extracted at the turbine shaft, measured by torque and angular velocity sensors.

Within this experimental framework, the motor effectively acts as the external force restoring the flow, analogous to the planetary forces in the real ocean environment. It is expected that, with high efficiency, the power extracted by the turbine will closely match the power applied to the system, demonstrating the feasibility of conversion based on a continuously restored flow.

It is acknowledged, however, that the laboratory environment presents inherent limitations, such as tank boundary effects, scale variations, and characteristics of the relative flow, which may introduce small distortions compared to open-field behavior. These factors will be considered in the critical analysis of the results.

The following evaluation parameters will be used:

Where:

is the shaft torque;

is the angular velocity;

is the water density;

U is the upstream flow velocity;

A is the projected area at the turbine inlet (considering the duct);

R is the rotor radius.

Measurements will follow the protocols of the International Towing Tank Conference (ITTC – 7.5-02-07-03.9 – Model Tests for Current Turbines) [

13].

A CFD model (Computational Fluid Dynamics) [

9] will also be developed and calibrated with experimental data to predict turbine performance under different scales and conditions.

In addition to ITTC guidelines, measurements will also comply with the recommended practices of the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) for marine current turbine evaluation [

14].

The integration between CFD models and empirical data is a common practice in offshore engineering, recognized by institutions such as IEA-OES and DNV-GL as a strategic tool for validating and scaling new ocean technologies.

If the results confirm CP > 1, this would imply that the measured shaft power of the UCEC exceeds the kinetic energy available in the flow section, thus validating the ERPF hypothesis: that energy is restored by external forces and not limited to the incident kinetic energy.

Such a result would challenge the classical paradigm of flow energy conversion and establish a new class of sustainable, high-efficiency ocean turbines.

Although the power coefficient CP continues to be calculated based on the locally incident kinetic energy, its meaning within the ERPF context is fundamentally altered

A CP > 1 does not imply a violation of energy conservation but instead indicates the continuous action of restoring forces within the system.

Similarly, the index κ, proposed to assess efficiency in restored systems, remains conceptually valid but is impractical to measure precisely, since the globally restored power associated with the vast moving oceanic masses—whose motion is continuously generated and sustained by planetary field forces—is physically immeasurable.

Thus, the experiments will use CP primarily as a traditional comparative reference, while the concept of κ will serve as a theoretical guide for the new interpretation of energy efficiency in restored flows.

6. Discussion

If validated by the proposed experimental tests, the Energy Restoration by Planetary Fields (ERPF) theory represents a rupture with traditional paradigms of energy conversion in flow systems.

By considering the continuous replenishment of kinetic energy by planetary field forces, ERPF challenges established limits—such as the Betz limit—and proposes that appropriately designed devices may achieve power coefficients greater than unity, provided they operate within a restored flow regime.

The UCEC emerges as the only currently known technological solution capable of translating ERPF principles into a functional system.

Unlike conventional turbines [

15], which extract energy by decelerating the flow and leave large bypass areas, the UCEC ensures that the entire mass of incident water interacts with the rotor, fully occupying the effective cross-sectional area of the flow.

This full occupation, combined with the Venturi effect induced by the convergent duct and the angular deflection imposed by the blades, enables maximum exploitation of the available energy without compromising the global flow dynamics.

By operating in resonance with the medium, the UCEC not only interacts harmoniously with the flow but also maximizes energy transfer with minimal losses, thereby enhancing the system's overall efficiency.

The proposed laboratory tests, using a dynamometric carriage to simulate steady currents, will allow direct comparison between the mechanical power extracted by the turbine and the electrical power consumed by the motors—considering the latter as an external restoring force analogous to planetary field forces.

This methodology will allow testing the hypothesis that externally restored energy can be almost entirely captured under near-ideal conditions.

Beyond its energy advantages, the UCEC also differentiates itself through its positive ecological impact.

Its geometry avoids cutting zones and allows the fluid to rotate coherently with the rotor, significantly reducing the risk of collisions with marine organisms. Additionally, the turbine structure can serve as a base for artificial reefs, promoting the regeneration of local biodiversity.

To facilitate the visualization of the conceptual and operational differences between traditional models and the ERPF paradigm implemented with the UCEC, the following comparative table summarizes the main parameters:

| Characteristic |

Conventional Models (Wind/Submerged) |

ERPF Model with UCEC |

| Operating Medium |

Air (compressible) / Water (partially incompressible) |

Ocean water (incompressible) |

| Energy Extraction |

Local flow speed reduction |

Vectorial redirection of the flow |

| Theoretical Efficiency Limit |

≤ 59.3% (Betz Limit) |

Potentially > 100% (κ < 1, CP>1C_P > 1CP>1) |

| Energy Replenishment |

Not considered (finite incident energy) |

Sustained by global environmental forces |

| Flow Disturbance |

High deceleration and turbulence |

Minimal vectorial disturbance |

| Cross-Section Occupation |

Partial (bypass zones) |

Full (vectorial deflection mesh) |

| Ecological Impact |

Disruptive (collision risk with fauna) |

Regenerative and safe for fauna |

The experimental validation will allow precise assessment of the vectorial conversion efficiency and the hydrodynamic parameters associated with the UCEC.

The results obtained will provide not only evidence of the system's energy performance but also fundamental inputs for computational modeling and the design of energy farms based on this technology.

The success of these tests would mark a major milestone in consolidating the UCEC as a technically viable proposal aligned with the ERPF model.

The convergence of geometric innovation, energy efficiency, and environmental compatibility proposed by the UCEC aligns with the latest guidelines for the advancement of sustainable ocean technologies, as highlighted in IEA-OES reports [

2].

7. Conclusion

The foundations developed throughout this article propose a substantial revision of classical conceptions regarding energy conversion in fluid systems.

The Energy Restoration by Planetary Fields (ERPF) theory introduces a new paradigm by recognizing that, although the movement of ocean currents is naturally generated by planetary field forces, these same forces continuously act to restore the energy that is eventually captured, thus maintaining the dynamic activity of the system.

This perspective breaks with traditional limits—such as the Betz limit—which assume that the available energy for converter systems is finite and locally bounded.

The Current Energy Collecting Unit (UCEC), designed based on this theory, offers an unprecedented geometric architecture for vectorial energy conversion.

Its design ensures complete interaction with the flow, without bypass zones, promoting the direct and continuous conversion of linear momentum into shaft torque in a harmonious and environmentally compatible manner.

The expectation of achieving power coefficients greater than 1, if experimentally confirmed, would position the UCEC as a unique technology in the global energy landscape.

The completion of laboratory tests will be decisive in empirically confirming the validity of the ERPF theory proposed in this work and in consolidating the UCEC as a next-generation technological solution.

By experimentally validating the hypothesis of restored systems, a new scientific and technological field may be opened, with the potential to profoundly impact applied physics, ocean engineering, and global energy transition strategies.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the continuous support received throughout the development of the ERPF theory and the UCEC prototype project. Special thanks are extended to all those who believed in the innovative potential of the work, providing encouragement, resources, and trust, which were essential for the scientific and technological advancements achieved so far.

References

- Pelc R, Fujita RM. Renewable energy from the ocean. Marine Policy 26 (2002): 471–479.

- IEA-OES. Annual Report 2020 – Ocean Energy Systems. International Energy Agency – Ocean Energy Systems (2020).

- Garrett C, Cummins P. The efficiency of a turbine in a tidal channel. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 588 (2007): 243–251. [CrossRef]

- Gill AE. Atmosphere-Ocean Dynamics. Academic Press (1982).

- Betz A. Das Maximum der theoretisch möglichen Ausnutzung des Windes durch Windmotoren. Zeitschrift für das gesamte Turbinenwesen 26 (1920): 307–309.

- Queiroz MO. Current Energy Collecting Unit. US Patent 12,168,969 B2 (2024).

- Bahaj AS, Myers L. Fundamentals applicable to the utilisation of marine current turbines for energy production. Renewable Energy 28 (2004): 2205–2211. [CrossRef]

- Lamb H. Hydrodynamics, 6th ed. Cambridge University Press (1932).

- DNV-GL. Recommended Practice DNVGL-RP-E103: Modelling and analysis of marine operations. DNV-GL (2020).

- Copping A, Hanna L, Whiting J, Geerlofs S, Grear M, Blake K, Sather N. Environmental Effects of Marine Renewable Energy Development around the World: Annex IV Final Report. Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (2014).

- Baine M. Artificial reefs: A review of their design, application, management and performance. Ocean & Coastal Management 44 (2001): 241–259. [CrossRef]

- Johnsack JA, Sutherland DL. Artificial reef research: a review with recommendations for future priorities. Bulletin of Marine Science 37 (1985): 11–39.

- International Towing Tank Conference (ITTC). Model Tests for Current Turbines – Recommended Procedures and Guidelines 7.5-02-07-03.9. ITTC (2021).

- International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC). IEC TS 62600-200: Marine energy – Wave, tidal and other water current converters – Part 200: Electricity producing tidal energy converters – Power performance assessment. IEC (2018).

- O’Rourke F, Boyle F, Reynolds A. Tidal energy update 2009. Applied Energy 87 (2010): 398–409. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).