4.2. Comparative Analysis of RoBERTa and BERT Models for Predicting Big Five Personality Trait Scores

Table 5 presents the performance of four transformer-based models: RoBERTa base, RoBERTa large, BERT base, and BERT large. The table includes a comparison of evaluation metrics covered in

Section 4.1, to assess how well each model predicts the Big Five personality traits. The results provide insight into the impact of model size and architecture on performance, helping to determine the most effective model for this task.

The average RMSE values across all models in this paper were similar, approximately 0.26, indicating comparable levels of prediction error. However, the RoBERTa models outperformed the BERT models in terms of , with the RoBERTa large model achieving the highest average value of 0.2404. Furthermore, the large model of the RoBERTa demonstrated slightly better performance than its base counterpart, suggesting that the dataset size is sufficient to effectively leverage the increased capacity of larger models. However, both the base and large BERT models exhibited nearly identical performance, showing no improvement despite the increased model capacity.

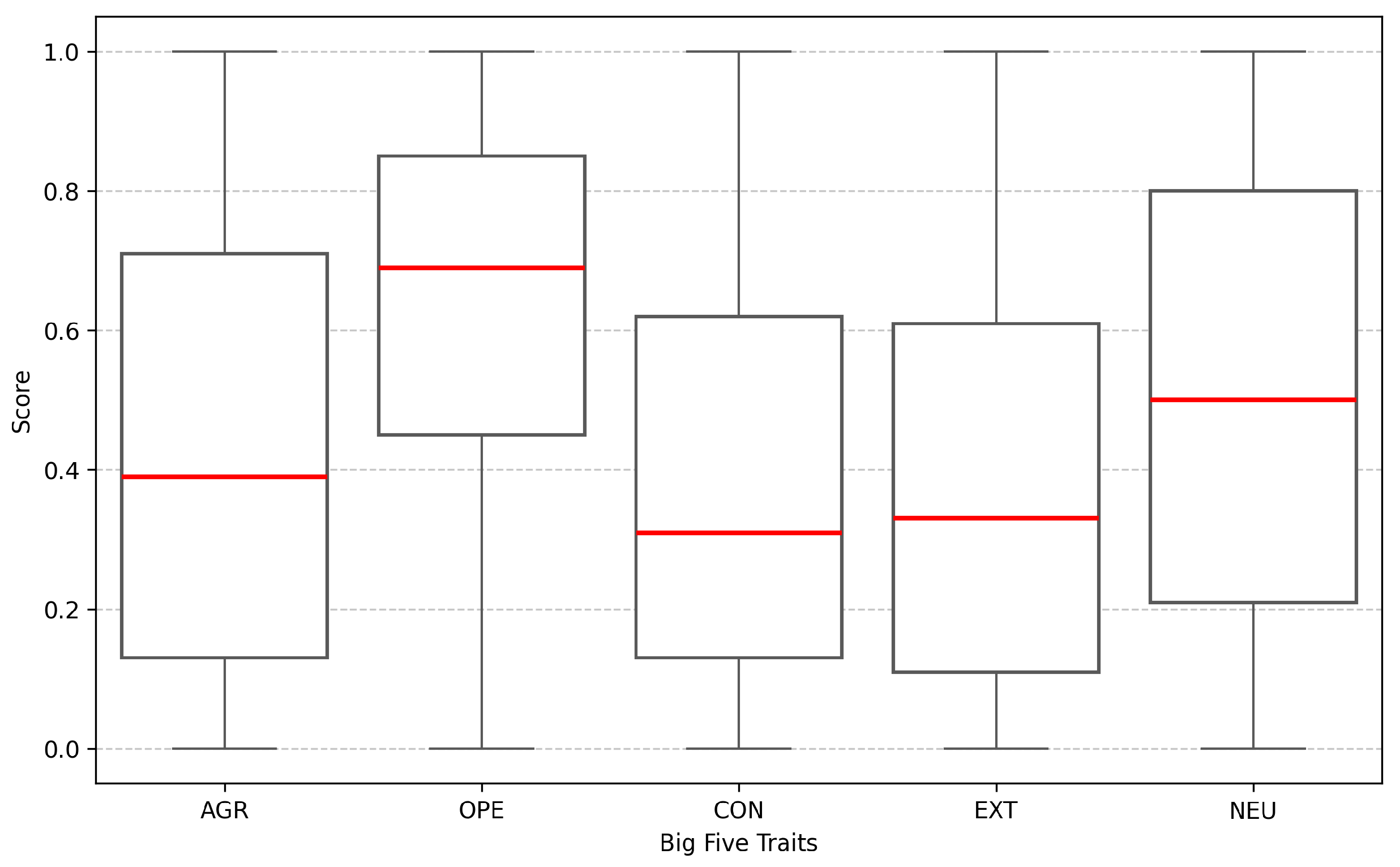

When examining the prediction of individual traits, Openness consistently exhibited the lowest RMSE values across all models, indicating that it is the easiest trait to predict. Similarly, Extraversion achieved the highest values across all models, highlighting its relative ease of predictability. In contrast, the models struggled with the prediction of Conscientiousness, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism. Conscientiousness posed significant challenges, as three models (RoBERTa base, BERT base, and BERT large) recorded the lowest values for this trait. Agreeableness was also difficult to predict, with two models yielding the highest RMSE values for this trait. Neuroticism proved particularly challenging for the RoBERTa large model, which recorded both the highest RMSE and the lowest values for this trait.

These findings highlight that while a larger model such as RoBERTa large, generally outperforms smaller models with this dataset, the prediction difficulty varies significantly across traits. Traits like Openness and Extraversion are more predictable, while others, such as Conscientiousness and Neuroticism, present persistent challenges even for advanced architectures.

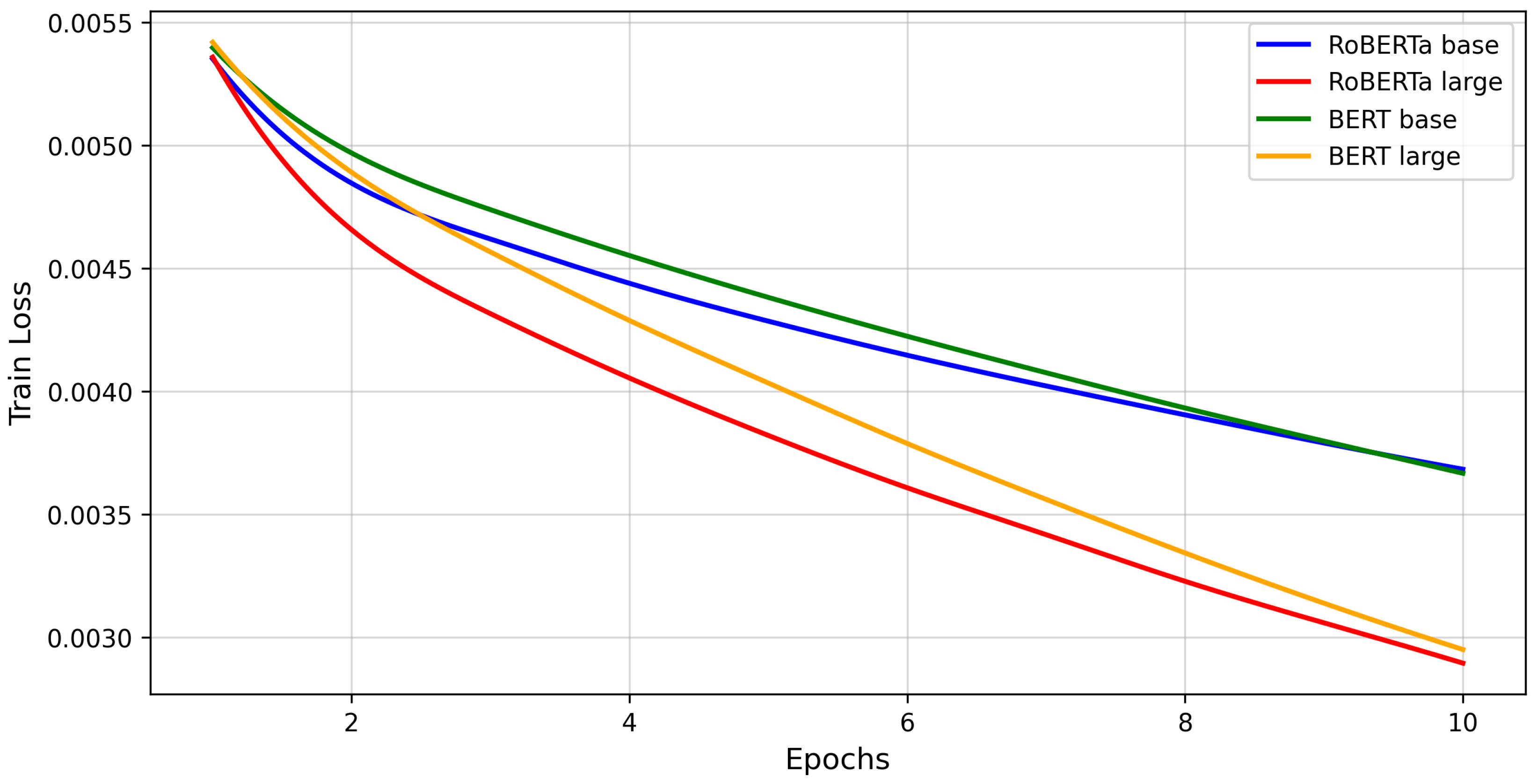

Figure 1 presents the training loss progression for the models, while

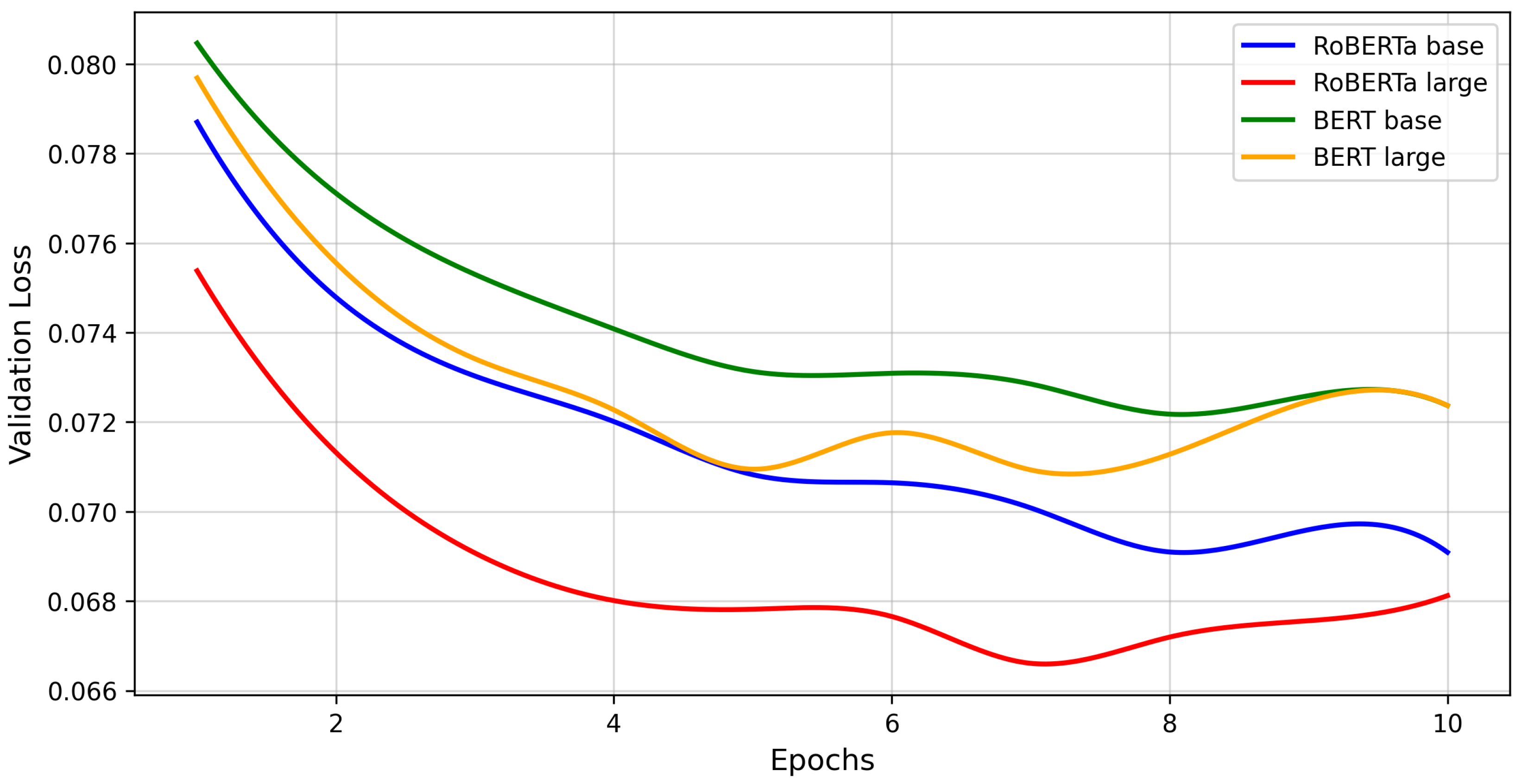

Figure 2 depicts the validation loss trends.

Based on the validation loss graphs, RoBERTa large consistently outperforms the others, achieving the lowest validation loss across all epochs, which indicates superior generalisation capabilities. Similarly, its training loss is the lowest, reflecting its efficiency in learning from the training data while minimizing overfitting. RoBERTa base follows closely, maintaining lower validation and training losses than both BERT base and BERT large, though it falls short of matching RoBERTa large’s performance.

In contrast, the BERT models demonstrate relatively higher training and validation losses. While BERT large performs slightly better than BERT base, both are outperformed by the RoBERTa models.

These results further highlight the advantages of the RoBERTa large architecture in effectively capturing linguistic nuances and context for this task.

Table 6 compares the results of a previous study [

21], models fine-tuned on a subset of the dataset used in this study, and the best-performing model in this paper—RoBERTa large—fine-tuned on a larger dataset. The columns labelled "Mean Baseline" and "RoBERTa" present the results from the reference study [

21], with "Mean Baseline" serving as a simplistic benchmark and "RoBERTa" showing the performance of the RoBERTa base model. In contrast, the column labelled "RoBERTa (large)" represents the best performing model in this paper, the RoBERTa large model.

The RoBERTa large model, which was fine-tuned on a larger dataset, outperformed the Mean Baseline in all five Big Five personality traits, demonstrating superior predictive accuracy across the board. In comparison to the Mean Baseline, the RoBERTa large model consistently achieved lower RMSE values and higher scores, indicating improved model performance, especially in the evaluation metric.

However, when comparing RoBERTa large to the RoBERTa model used in the previous work, we observe that the larger dataset used to fine-tune RoBERTa large did not translate into better performance in the evaluation metrics used. Despite its larger training data, RoBERTa large underperformed relative to the RoBERTa model from the previous work in terms of both RMSE and across all traits. Specifically, the RoBERTa model from the previous work achieved an average RMSE of 0.2241 and an average of 0.4148, both of which are generally better than those of RoBERTa large, which achieved an average RMSE of 0.2606 and an average of 0.2404. This suggests that even though a larger dataset was used for fine-tuning RoBERTa large, it did not necessarily improve its predictive capabilities compared to the RoBERTa fine-tuned on a smaller dataset in the previous work.

Despite these differences, the two models exhibited similar trends in terms of trait prediction. Both RoBERTa models showed the lowest RMSE in predicting Openness, suggesting that the models were more accurate in this trait. Additionally, both models showed the highest for Extraversion, indicating relatively stronger performance in predicting this trait. However, both models struggled with Neuroticism, as it was associated with the highest RMSE and the lowest in both cases. This suggests that predicting Neuroticism is particularly challenging for these models, regardless of the dataset size.

4.3. Investigating the Impact of Intercorrelations Among Big Five Personality Traits

Table 7 summarises the results of Big Five personality trait score predictions in

Section 3.3.2 in comparison to the previous work [

21]. The columns labelled "Mean Baseline" and "RoBERTa" present the results from the reference study [

21]. In contrast, the columns labelled "RoBERTa (Single)" and "RoBERTa (Multiple)" reflect the results of this study. "RoBERTa (Single)" represents the results of the single-model approach, fine-tuning a single model to predict all five traits simultaneously, while "RoBERTa (Multiple)" refers to the average performance of the separate models in the multiple-models approach, fine-tuned individually for each trait.

When the overall performance of the single-model RoBERTa approach in this study is compared with the results of RoBERTa in the previous work, it is observed that the model fine-tuned in this study underperformed despite being fine-tuned on a larger dataset. However, the trends in the results are mostly consistent between the two models.

For both models, Openness achieved the lowest RMSE (0.1742 for the model from the previous work and 0.2345 for the single-model approach), while Neuroticism had the highest RMSE (0.2527 for the model from the previous study and 0.2737 for the single-model approach). This indicates that Openness is relatively easier to predict, whereas Neuroticism is more challenging. In terms of , both models also agree that Extraversion is the easiest trait to predict with the model from the previous work scoring 0.5229 and the single model approach scoring 0.2604. However, the model fine-tuned in this study recorded the lowest for Conscientiousness (0.2161), whereas the previous work reported Neuroticism as having the lowest (0.3248). This suggests differences in trait-specific performance, despite some alignment in trait predictability trends.

In contrast, the results for the multiple-models approach, where separate models were fine-tuned for each trait, were closer to the mean baseline results. These models exhibited higher RMSE values overall and values close to zero, indicating poor predictive performance. This suggests that fine-tuning separate models for each trait is less effective and produces inconclusive results than the single-model approach. It highlights the significance of the intercorrelations among the Big Five personality traits in enhancing predictive performance.