Submitted:

29 April 2025

Posted:

30 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

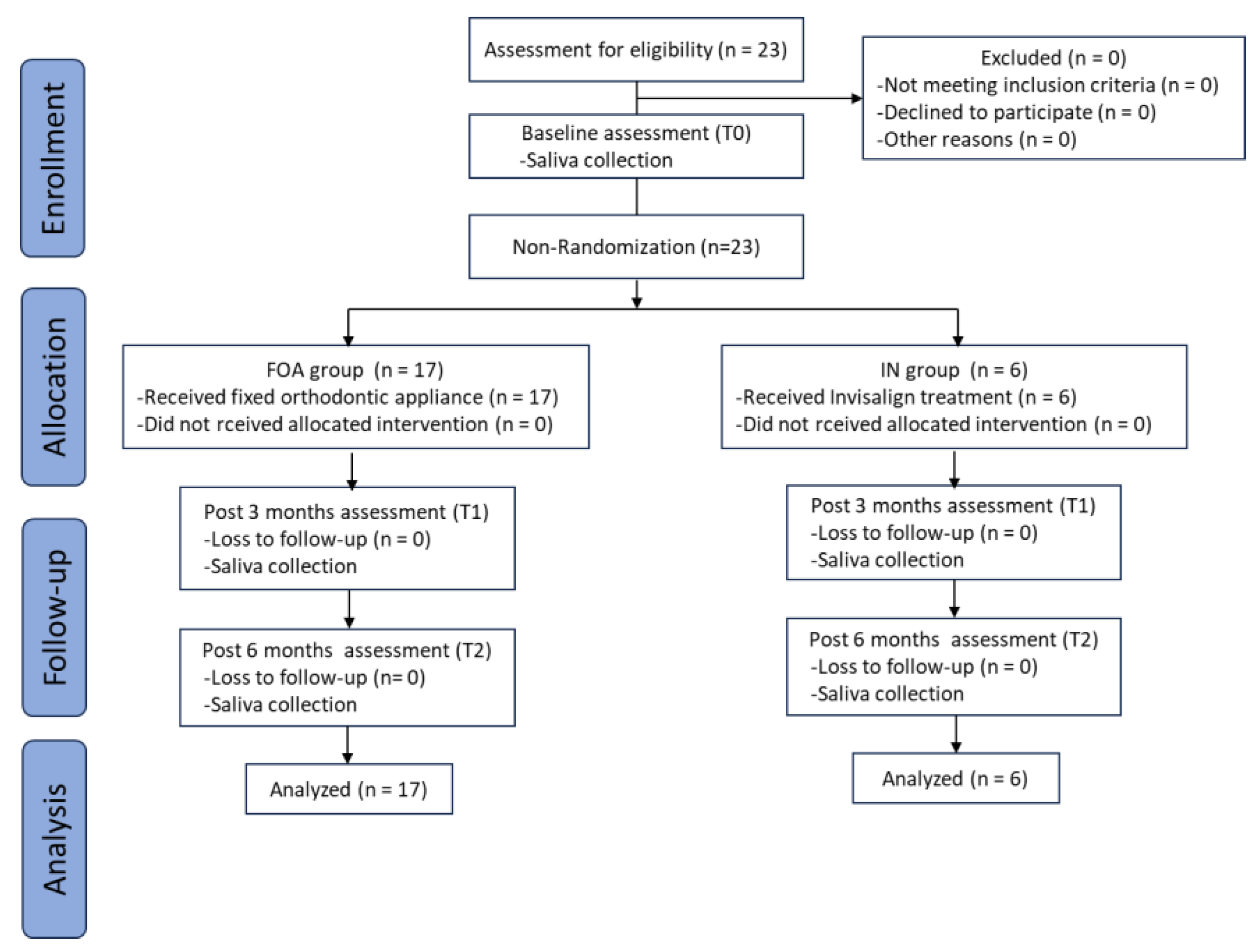

2.2. Study Design and Subjects

2.3. Collection and Processing of Saliva

2.4. Salivary Sample Processing for Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) Analysis

2.5. LC-MS/MS Analysis and Protein Identification

2.6. Data Visualization and Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Participants

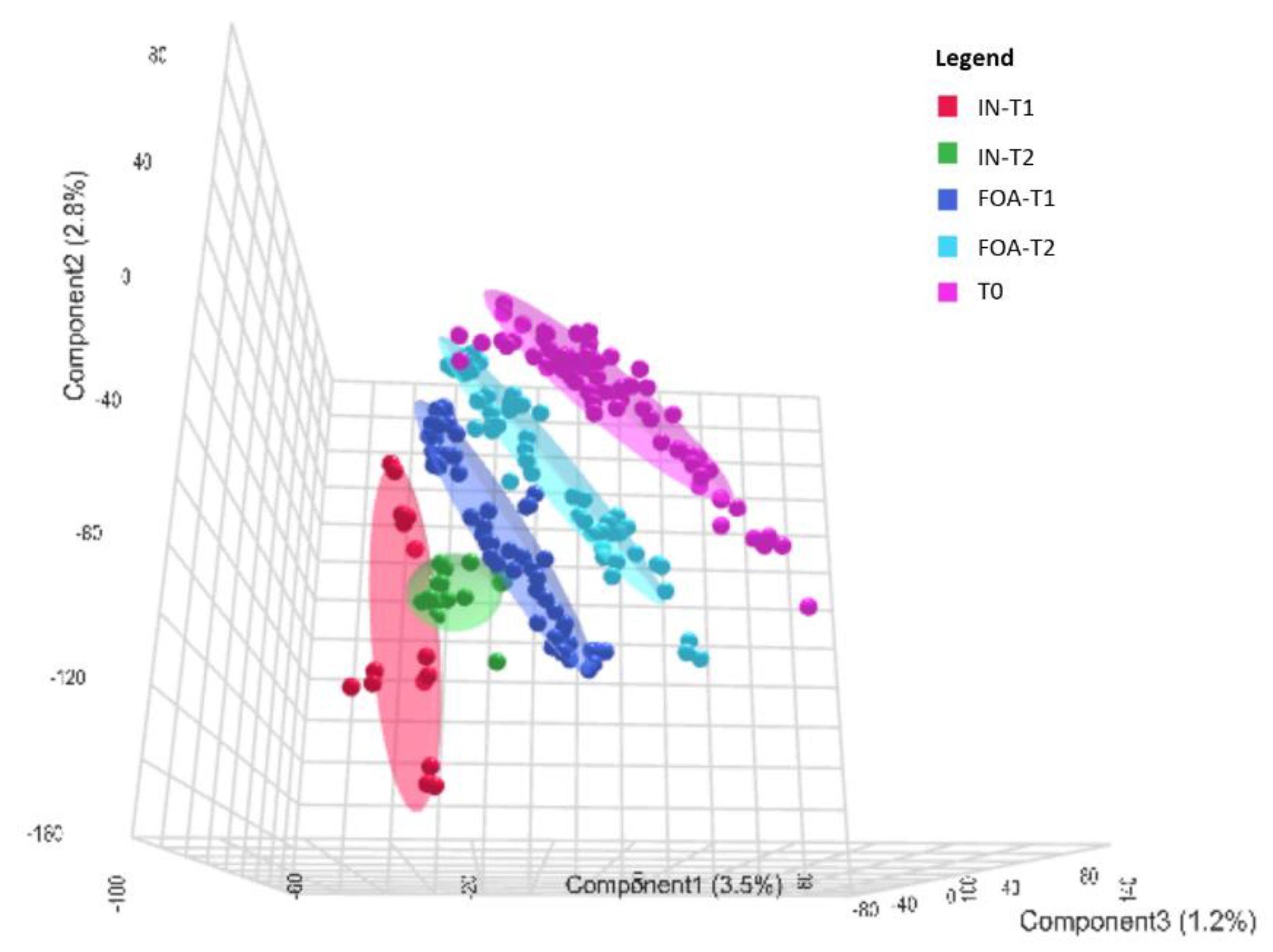

3.2. Salivary Protein Profiles in Response to FOA and IN at T0, T1, and T2

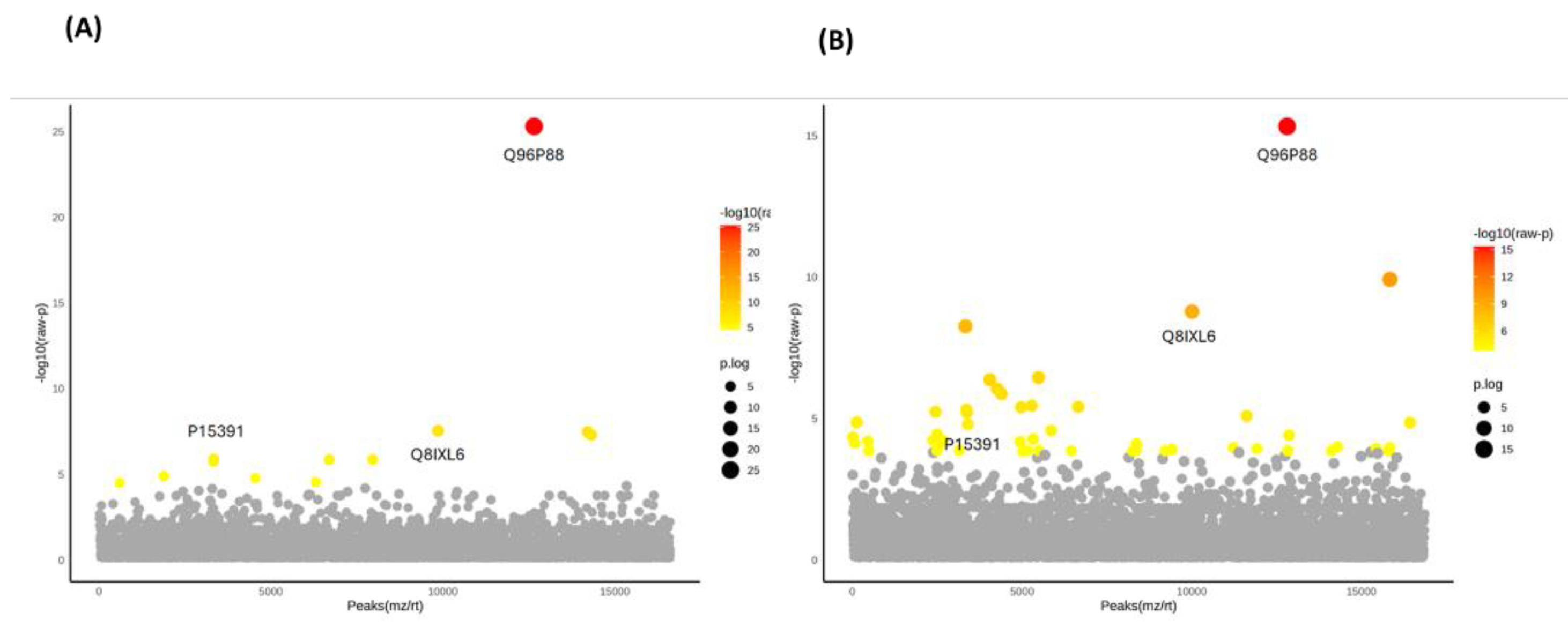

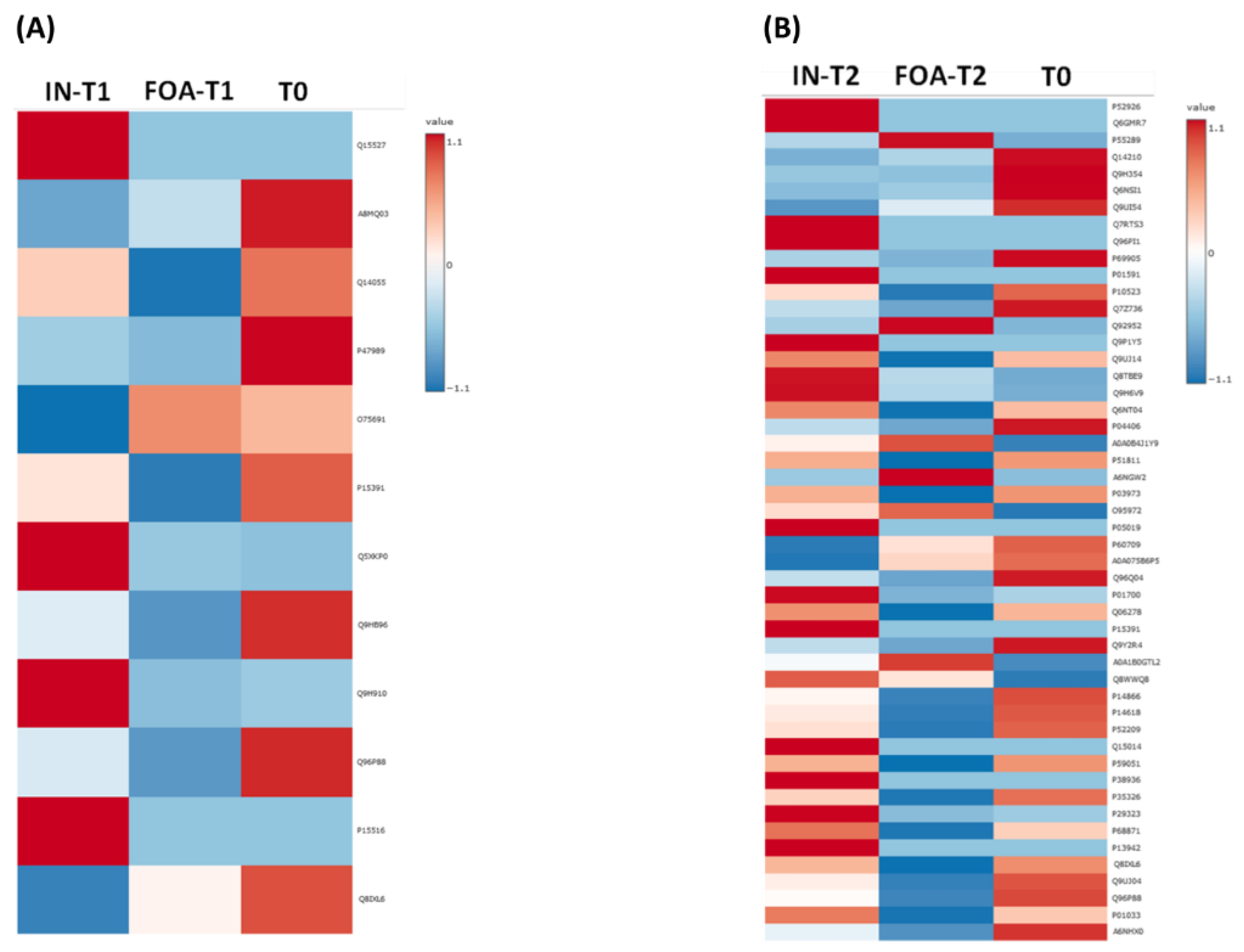

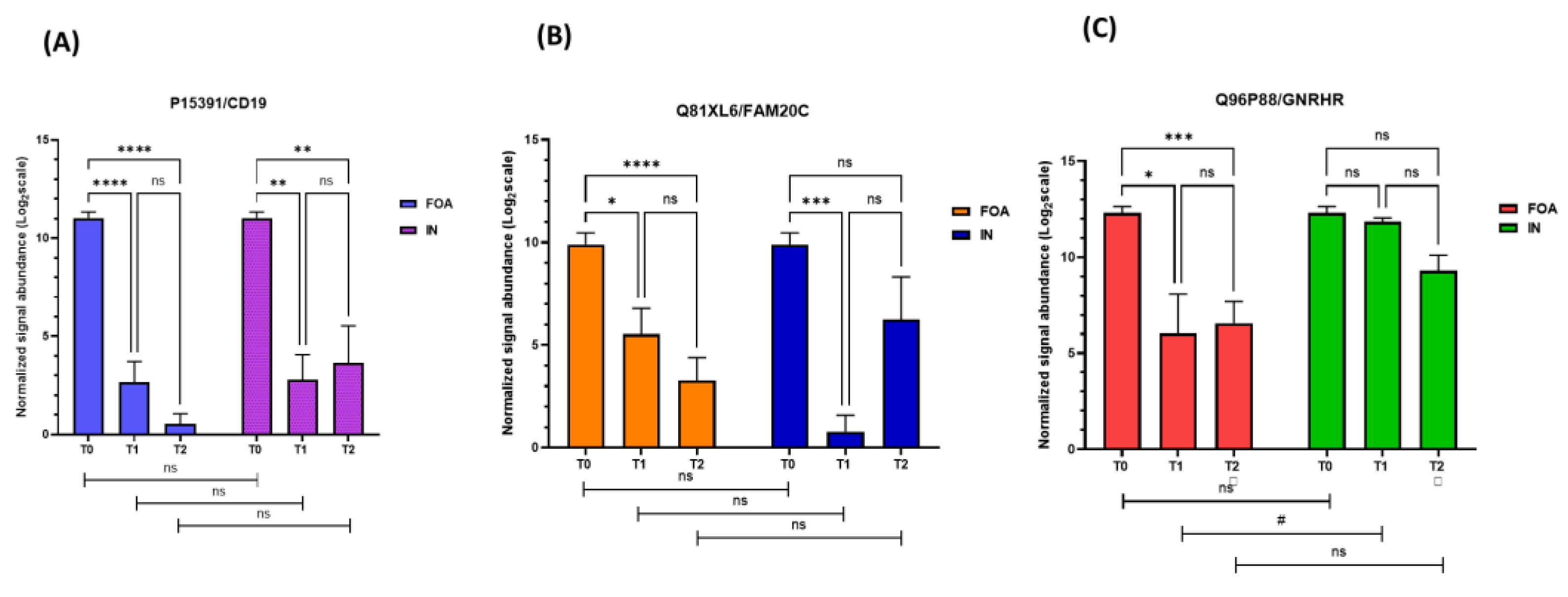

3.3. Identification of DEPs in FOA and IN at T0, T1, and T2

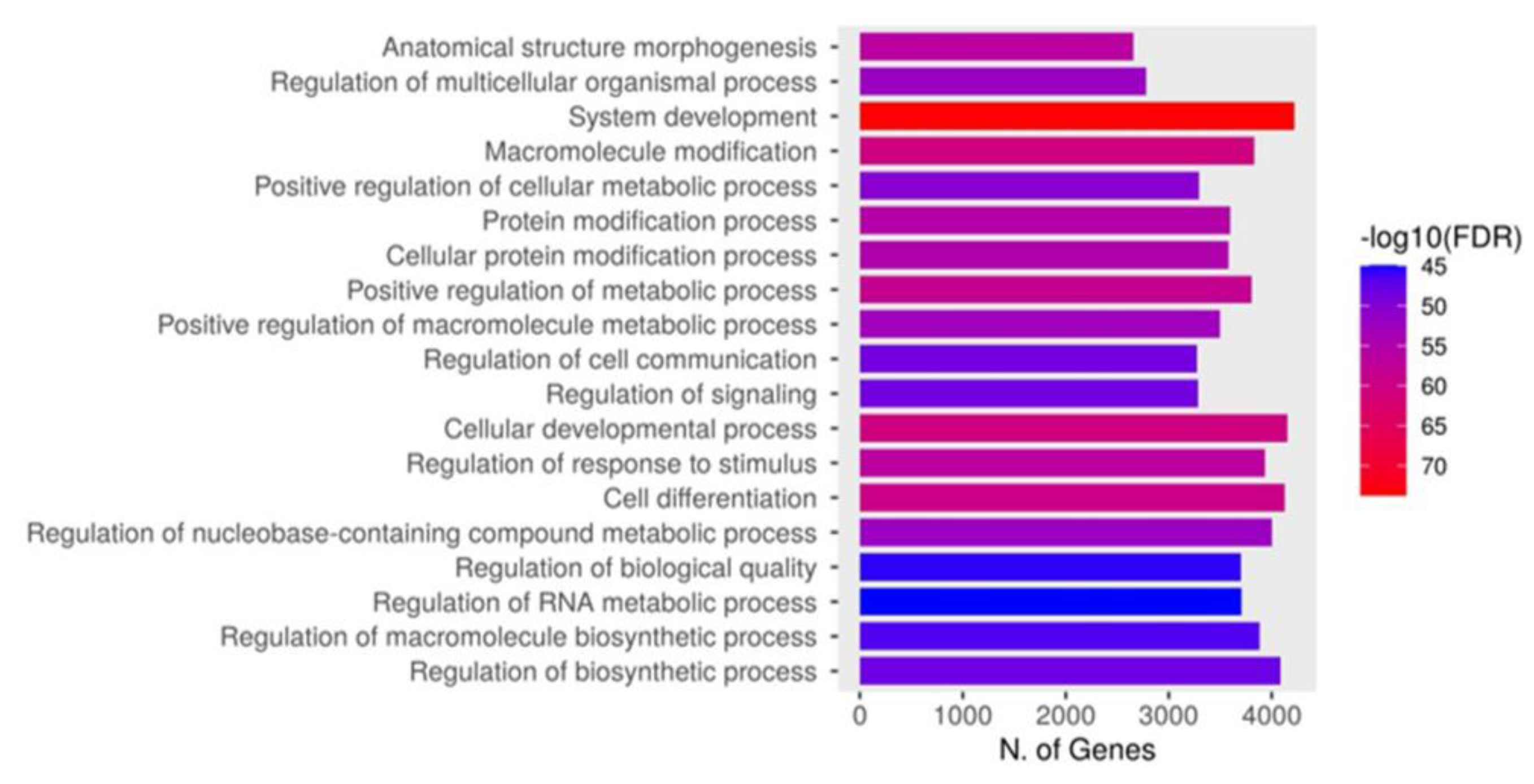

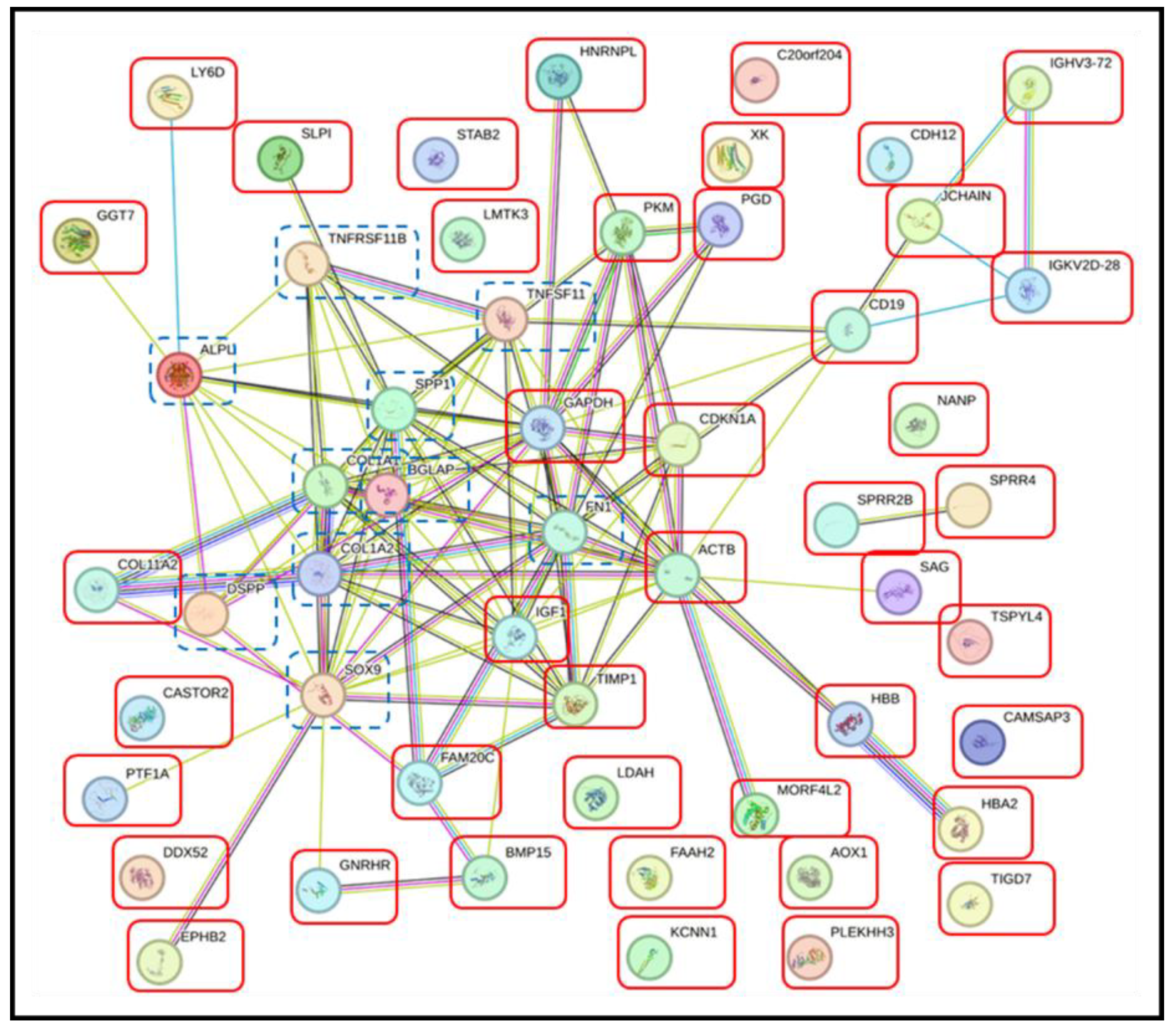

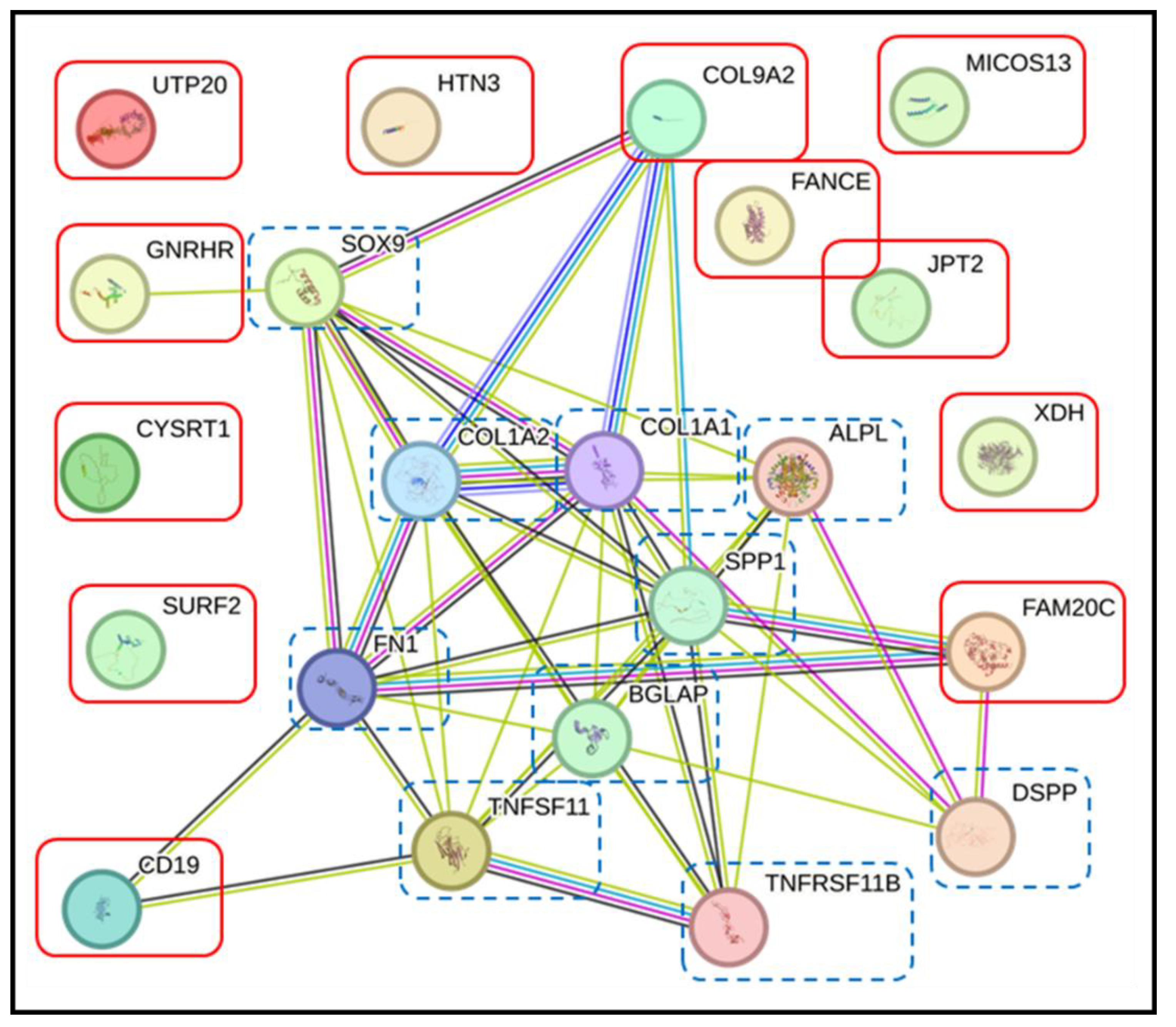

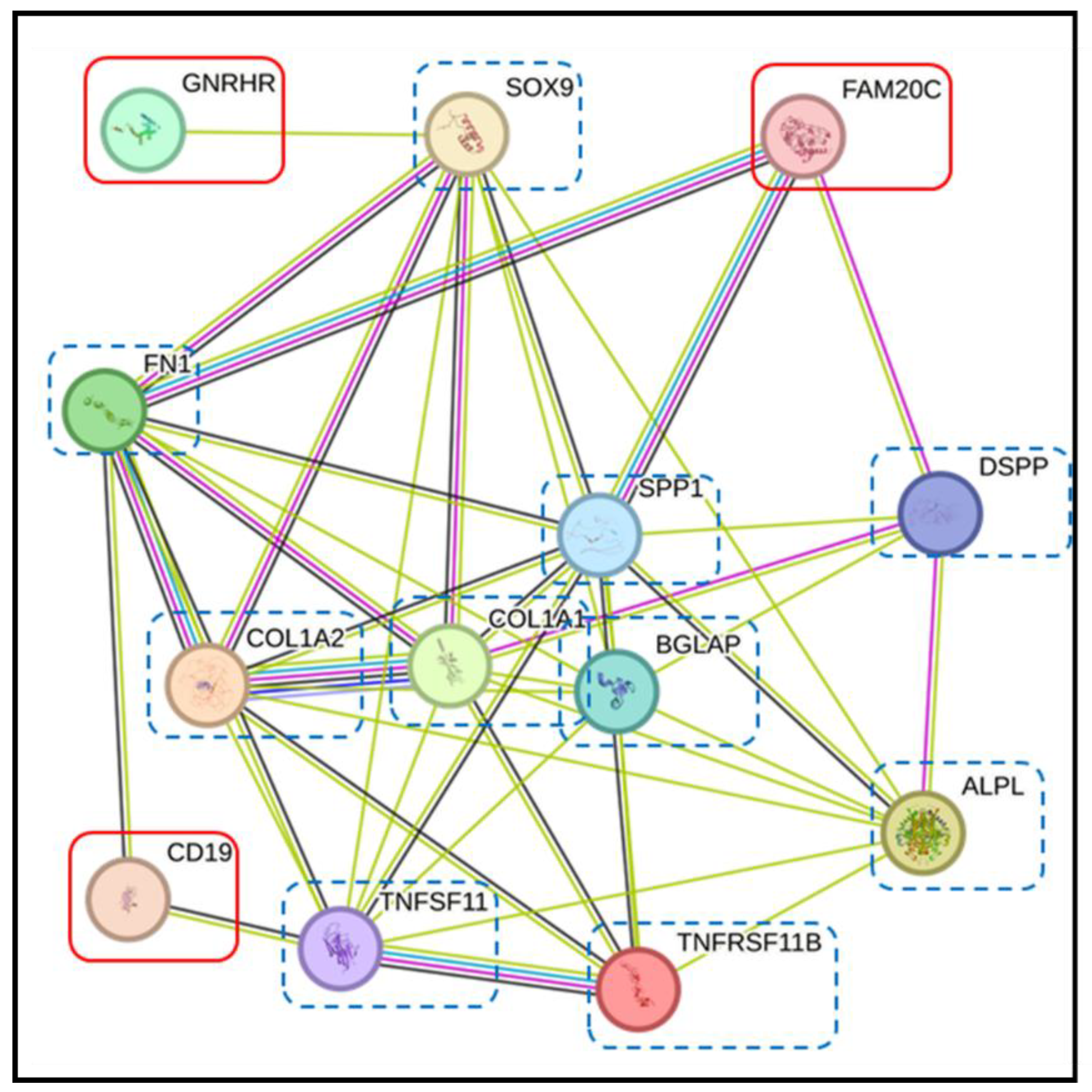

3.4. Pathway Analysis with the STRING Database

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALPL | Alkaline phosphatase |

| AmBic | Ammonium bicarbonate |

| ApoE | Apolipoprotein E |

| BGLAP | Osteocalcin |

| BSP | Bone sialoprotein |

| CD | Cluster of differentiation |

| COL1A1 | Collagen alpha-1 |

| COL1A2 | Collagen alpha-2 |

| DEPs | Differentially expressed proteins |

| DMP1 | Dentin matrix protein 1 |

| DSPP | Dentin sialophosphoprotein |

| DTT | Dithiothreitol |

| ERK | Extracellular signal-regulated kinase |

| FAM20C (Q8IXL6) | Family with sequence similarity 20C |

| FDR | False discovery rate |

| FN1 | Fibronectin |

| FOA | Fixed orthodontic appliance |

| GNRHR(Q96P88) | Gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor |

| GO | Gene ontology |

| IAA | Iodoacetamide |

| IHH | Indian hedgehog |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1β |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IN | Invisalign |

| LC-MS/MS | Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MEPE | Matrix extracellular phosphoglycoprotein |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa B |

| OPG | Osteoprotegerin |

| OTM | Orthodontic tooth movement |

| PLS-DA | Partial least squares discriminant analysis |

| PPI | Protein-protein interaction |

| PTHrp | Parathyroid hormone-related protein |

| RANK | Receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa B |

| RANKL | Receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa B ligand |

| SIBLING | Small integrin-binding ligand N-linked glycoprotein |

| SOX9 | Sex-determining region Y-box 9 |

| SPP1/OPN | Osteopontin |

| STRING | Search tool for the retrieval of interacting genes |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| TNFSF11/RANK | Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 11 |

| TNFRSF11B | Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 11B |

| TREND | Transparent reporting of evaluations with nonrandomized designs |

References

- Li, Y.; Zhan, Q.; Bao, M.; Yi, J.; Li, Y. Biomechanical and biological responses of periodontium in orthodontic tooth movement: up-date in a new decade. Int J Oral Sci 2021, 13, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, R.K.; Edelmann, A.R.; Abdulmajeed, A.; Bencharit, S. Salivary protein biomarkers associated with orthodontic tooth movement: A systematic review. Orthod Craniofac Res 2019, 22 (Suppl 1), 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popovic, V.Z.; Grgurevic, L.; Trkulja, V.; Novak, R.; Negovetic-Vranic, D. The role of new technologies in defining salivary protein composition following placement of fixed orthodontic appliances - breakthrough in the development of novel diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. Acta Clin Croat 2020, 59, 480–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellias, M.F.; Ariffin, S.H.Z.; Karsani, S.A.; Rahman, M.A.; Senafi, S.; Wahab, R.M.A. Proteomic analysis of saliva identifies potential biomarkers for orthodontic tooth movement. Sci World J 2012, 2012, 647240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grgurevic, L.; Novak, R.; Salai, G.; Trkulja, V.; Hamzic, L.F.; Popovic, V.Z.; Bozic, D. Identification of bone morphogenetic protein 4 in the saliva after the placement of fixed orthodontic appliance. Prog Orthod 2021, 22, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Sun, B.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, T.; He, D.; Lin, J.; Chen, F. Apolipoprotein E is an effective biomarker for orthodontic tooth movement in patients treated with transmission straight wire appliances. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2022, 161, 255–262 e251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, B.; Dunn, L. The declaration of Helsinki on medical research involving human subjects: A review of seventh revision. J Nepal Health Res Counc 2020, 17, 548–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brysbaert, M. How many participants do we have to include in properly powered experiments? A tutorial of power analysis with reference tables. J Cogn 2019, 2, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portillo, F.R.L.; Valenzuela, J.G.; Alcaraz, V.R.; Urias, A.E.V.; Pérez, D.D.R.M.; Guerrero, F.M.M.; Celaya, G.E.G.; Arredondo, T.G.; Beltrán, M.A.Q.; Antonio, M.; et al. Dental crowding: a review. Int J Res Med Sci 2024, 12, 1344–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falagas, M.E.; Pitsouni, E.I. Guidelines and consensus statements regarding the conduction and reporting of clinical research studies. Arch Intern Med 2007, 167, 877–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowry, O.H.; Rosebrough, N.J.; Farr, A.L.; Randall, R.J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem 1951, 193, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyanova, S.; Temu, T.; Cox, J. The MaxQuant computational platform for mass spectrometry-based shotgun proteomics. Nat Protoc 2016, 11, 2301–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, S.X.; Jung, D.; Yao, R. ShinyGO: a graphical gene-set enrichment tool for animals and plants. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 2628–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Z.; Zhou, G.; Ewald, J.; Chang, L.; Hacariz, O.; Basu, N.; Xia, J. Using MetaboAnalyst 5.0 for LC-HRMS spectra processing, multi-omics integration and covariate adjustment of global metabolomics data. Nat Protoc 2022, 17, 1735–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Kirsch, R.; Koutrouli, M.; Nastou, K.; Mehryary, F.; Hachilif, R.; Gable, A.L.; Fang, T.; Doncheva, N.T.; Pyysalo, S.; et al. The STRING database in 2023: protein-protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res 2023, 51, D638–D646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bud, A.; Lazar, L.; Martu, M.A.; Dako, T.; Suciu, M.; Vlasiu, A.; Lazar, A.P. Challenges and perspectives regarding the determination of gingival crevicular fluid biomarkers during orthodontic treatment: A narrative review. Medicina (Kaunas) 2024, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, F.; Al-Kheraif, A.A.; Romanos, E.B.; Romanos, G.E. Influence of orthodontic forces on human dental pulp: a systematic review. Arch Oral Biol 2015, 60, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maltha, J.C.; Kuijpers-Jagtman, A.M. Mechanobiology of orthodontic tooth movement: An update. J World Fed Orthod 2023, 12, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thalanany, R.; Uma, H.I.; Ahmed, N. Estimation of dentin sialophosphoprotein in gingival crevicular fluid during orthodontic intrusion using Ricketts’ simultaneous intrusion and retraction utility arch. Int J Curr Res 2017, 9, 50483–50486. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.A.; Saravanan, K.; Kohila, K.; Kumar, S.S. Biomarkers in orthodontic tooth movement. J Pharm Bioallied Sci 2015, 7, S325–S330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugraha, A.P.; Narmada, I.B.; Ernawati, D.S.; Dinaryanti, A.; Hendrianto, E.; Ihsan, I.S.; Riawan, W.; Rantam, F.A. Osteogenic potential of gingival stromal progenitor cells cultured in platelet rich fibrin is predicted by core-binding factor subunit-alpha1/Sox9 expression ratio ( in vitro). F1000Res 2018, 7, 1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wesott, D.C.; Pinkerton, M.N.; Gaffey, B.J.; Beggs, K.T.; Milne, T.J.; Meikle, M.C. Osteogenic gene expression by human periodontal ligament cells under cyclic tension. J Dent Res 2007, 86, 1212–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Gill, G.; Kaur, H.; Amhmed, M.; Jakhu, H. Role of osteopontin in bone remodeling and orthodontic tooth movement: a review. Prog Orthod 2018, 19, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, I.G.; Raghunath, N.; Jyothikiran, H. RANK-RANKL-OPG: A current trends in orthodontic tooth movement and its role in accelerated orthodontics. Int J Appl Dent Sci 2022, 8, 630–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, M. RANK⁄RANKL ⁄OPG during orthodontic tooth movement. Orthod Craniofac Res 2009, 12, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermiglio, G.; Centofanti, A.; Matarese, G.; Militi, A.; Matarese, M.; Arco, A.; Nicita, F.; Cutroneo, G. Human dental pulp tissue during orthodontic tooth movement: An immunofluorescence study. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Wei, G.; Liu, D. CD19: a biomarker for B cell development, lymphoma diagnosis and therapy. Exp Hematol Oncol 2012, 1, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueredo, C.M.; Lira-Junior, R.; Love, R.M. T and B cells in periodontal disease: New functions in a complex scenario. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20, 3949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Min, Q.; Li, X.; Liu, L.; Lv, Y.; Xu, W.; Liu, X.; Wang, H. Immune system acts on orthodontic tooth movement: Cellular and molecular mechanisms. Biomed Res Int 2022, 2022, 9668610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, Y.; Fleissig, O.; Polak, D.; Barenholz, Y.; Mandelboim, O.; Chaushu, S. Immunorthodontics: in vivo gene expression of orthodontic tooth movement. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 8172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasi, G.; Cordasco, G.; Matarese, G.; Rizzo, G.; Nucera, R.; Mazza, M.; Militi, A.; Portelli, M.; Cutroneo, G.; Favaloro, A. An immunohistochemical, histological, and electron-microscopic study of the human periodontal ligament during orthodontic treatment. int J Mol Med 2008, 21, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goda, S.; Hayashi, H.; Ujii, Y.; Takeuchi, O.; Komasa, R.; Domae, E.; Yamamoto, K.; Matsumoto, N.; Ikeo, T. Fibronectin inhibited RANKL-induced differentiation into osteoclast. J Oral Tissue Engin 2014, 11, 227–233. [Google Scholar]

- Manabe, N.; Kawaguchi, H.; Chikuda, H.; Miyaura, C.; Inada, M.; Nagai, R.; Nabeshima, Y.-i.; Nakamura, K.; Sinclair, A.M.; Scheuermann, R.H.; et al. Connection between B lymphocyte and osteoclast differentiation pathways. J Immunol 2001, 167, 2625–2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.H.; Lin, I.P.; Ohyama, Y.; Mochida, H.; Kudo, A.; Kaku, M.; Mochida, Y. FAM20C directly binds to and phosphorylates periostin. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 17155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palma-Lara, I.; Perez-Ramirez, M.; Alonso-Themann, P.G.; Espinosa-Garcia, A.M.; Godinez-Aguilar, R.; Bonilla-Delgado, J.; Lopez-Ornelas, A.; Victoria-Acosta, G.; Olguin-Garcia, M.G.; Moreno, J.; et al. FAM20C overview: classic and novel targets, pathogenic variants and Raine syndrome phenotypes. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, K.; Kawasaki, M.; Wanatabe, M.; Idrus, E.; Nagai, T.; Oommen, S.; Maeda, T.; Haiwara, N.; Que, J.; Sharpe, P.; et al. Expression of Sox genes in tooth development. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2015, 59, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddharth, S.; Shweta, R.K.; Sunil, K.; Shrinivas, R.; Gayetri, K. Orthodontic forces commanding genes to cue teeth in lines: A meta analysis. Genom & Gene Ther Int J 2018, 2, 000106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-W.; Wang, K.-L.; Ho, K.-H.; Hsieh, S.-C.; Chang, H.-M. Dental pulp response to orthodontic tooth movement. Taiwanese J Orthod 2017, 29, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inchingolo, F.; Inchingolo, A.M.; Malcangi, G.; Ferrante, L.; Trilli, I.; Di Noia, A.; Piras, F.; Mancini, A.; Palermo, A.; Inchingolo, A.D.; et al. The Interaction of cytokines in orthodontics: A systematic review. Appl Sci 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Chenglin, W.; Liu, M.; Yin, B.; Huang, D.; Ye, L. ;. Inhibition of SOX9 promotes inflammatory and immune responses of dental Pulp. J Endod 2018, 44, 792–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameer, S.A.A.; Alhuwaizi, A.F. The effect of orthodontic force on salivary levels of alkaline phosphatase enzyme. J Bagh Coll Dent 2015, 27, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khatieeb, M.M.; Rafeeg, R.A.; Saleem, A. The relationship between orthodontic force applied by monoblock and salivary levels of alkaline phosphatase and lactate dehydrogenase enzymes. J Contemp Dent Pract 2018, 19, 1346–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Florez-Moreno, G.A.; Marin-Restrepo, L.M.; Isaza-Guzman, D.M.; Tobon-Arroyave, S.I. Screening for salivary levels of deoxypyridinoline and bone-specific alkaline phosphatase during orthodontic tooth movement: a pilot study. Eur J Orthod 2013, 35, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amanda, J.; RWidayati, R.; Soedarsono, N.; Purwanegara, M.K. RANKL concentrations in early orthodontic treatment using passive self-ligating and preadjusted edgewise appliance bracket systems. J Phys Conf. Ser 2018, 1073, 042002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, J.J. Principles and applications of liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry in clinical biochemistry. Clin Biochem Rev 2009, 30, 19–34. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).