1. Introduction

Wars have historically been linked to shifts in drug consumption patterns among both combatants and civilians. Armed conflicts create conditions that encourage drug production, trafficking, and abuse, often intensifying public health crises (Shaw, 20216). Throughout history, wars have shaped drug markets by disrupting supply chains, forging new trafficking routes, and increasing demand driven by psychological distress and economic instability. Drug trafficking has long served as a significant source of income not only for organized crime but also for various state and non-state actors (Shaw, 2016). This connection can be traced back to the opium wars in China during the 1840s, through the Iran-Contra affair of the 1980s, and into more recent conflicts such as the insurgencies in Colombia and Afghanistan (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2009; Castaño et als, 2018). The illicit trade provides substantial amounts of hard currency that can be difficult to trace and may be utilized to further political agendas. However, the chronic implications of drug trafficking and organized crime often receive less attention (Shaw, 2016). These activities can exacerbate existing conflicts and undermine the rule of law, complicating the dynamics of warfare. It is overly simplistic to assert that all conflicts are beneficial for organized crime, or that most terrorist groups are involved in drug trafficking; such statements lack the necessary nuance and do not accurately reflect reality (Shaw, 2016). Organized crime thrives in environments with weak and corruptible systems of governance rather than in those with no rule of law at all. Indeed, instability can elevate risks and disrupt the business models of certain drug trafficking organizations, presenting significant challenges for policymakers and development actors working in post-conflict nations that have struggled with drug-related issues for years (Shaw, 2016).

Throughout history, the connection between warfare and drug use has been deeply intertwined. From ancient civilizations to modern-day conflicts, both soldiers and civilians have sought refuge in various substances to manage the stress, trauma, and hardships that accompany war. For instance, during World War I, morphine and cocaine were widely used to numb pain and enhance soldiers' endurance (Molina-Fernández, 2024). In the Vietnam War, heroin became a prevalent substance among American troops. More recently, the conflicts in the Middle East and Eastern Europe have transformed drug production and consumption patterns, affecting not only the nations directly involved in the fighting but also those indirectly impacted (Centre for the study of Democracy, 2007). Wars profoundly influence drug consumption, primarily through the psychological burden they impose on affected populations. Combatants facing extreme stress and trauma often resort to drugs for relief. Civilians, especially those displaced by conflict, frequently experience heightened levels of anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), leading to increased rates of substance abuse. As a result, drug availability and affordability tend to rise in war-torn regions, further complicating the issue. Beyond altering demand, wars significantly reshape the supply side of the drug trade. Armed conflicts create environments conducive to the growth of illicit drug markets. Law enforcement efforts often falter or become preoccupied with military operations, allowing drug cartels and traffickers to operate with relative freedom (Shaw, 2016). Additionally, drug cultivation and production tend to escalate in areas where agricultural and economic infrastructures have collapsed due to conflict. Afghanistan, for instance, has seen a dramatic rise in opium production during its prolonged periods of war, leading to its status as the world’s largest supplier of heroin.

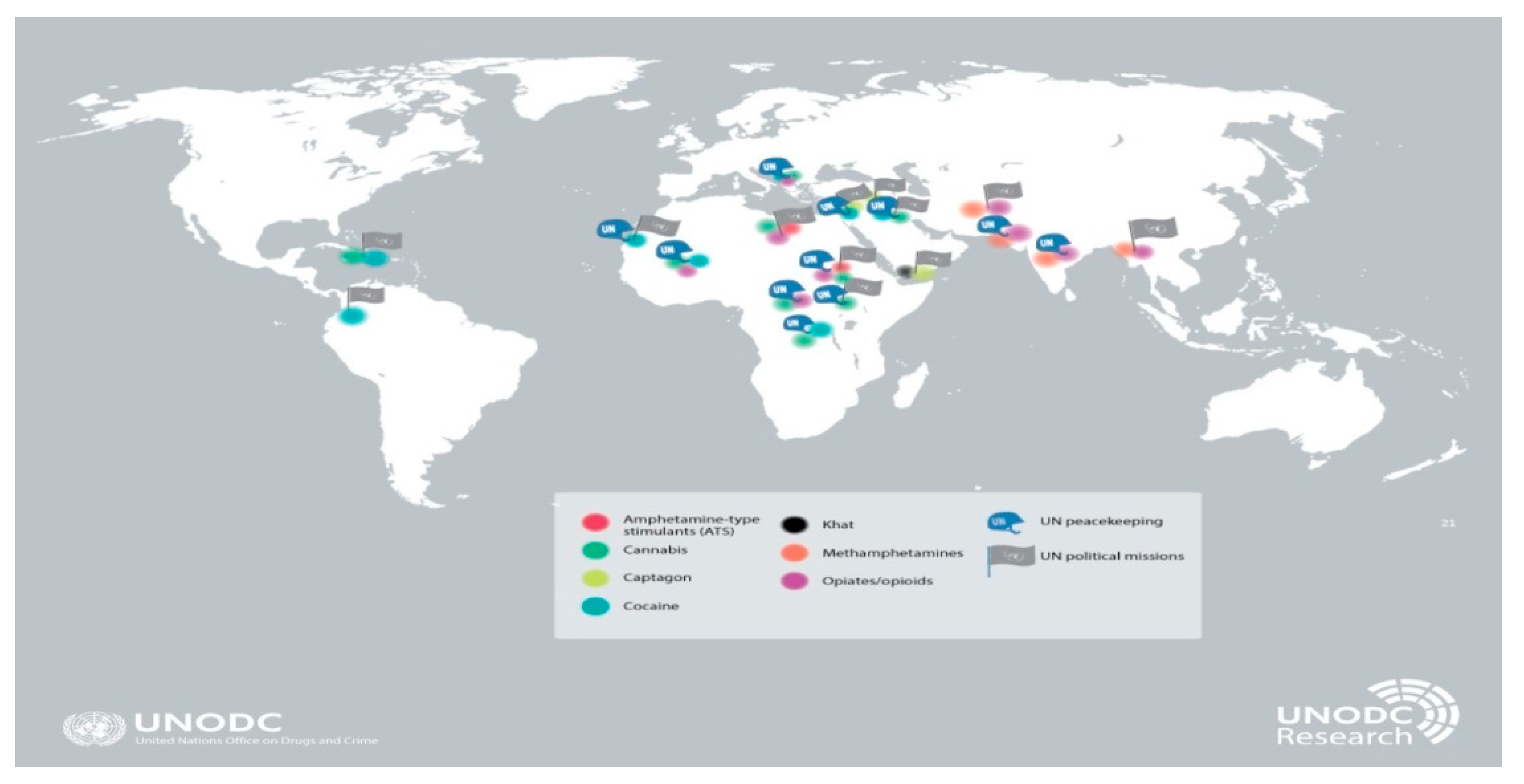

Figure 1.

Drug threats in fragile and conflict-related areas (UNODC, 2024).

Figure 1.

Drug threats in fragile and conflict-related areas (UNODC, 2024).

Wars significantly alter drug trafficking routes (Shaw, 2016). When traditional trade networks are disrupted, traffickers are compelled to find alternative pathways, often leading to the expansion of drug markets into previously unaffected regions. The Syrian civil war, for example, has been a catalyst for the increased production and smuggling of captagon, resulting in serious consequences throughout the Middle East and North Africa. Similarly, the ongoing conflict in Ukraine has opened new avenues for drug traffickers, who exploit weakened law enforcement and the economic hardships faced by impacted communities. Given these dynamics, it is clear that war plays a pivotal role in shaping global drug consumption patterns.

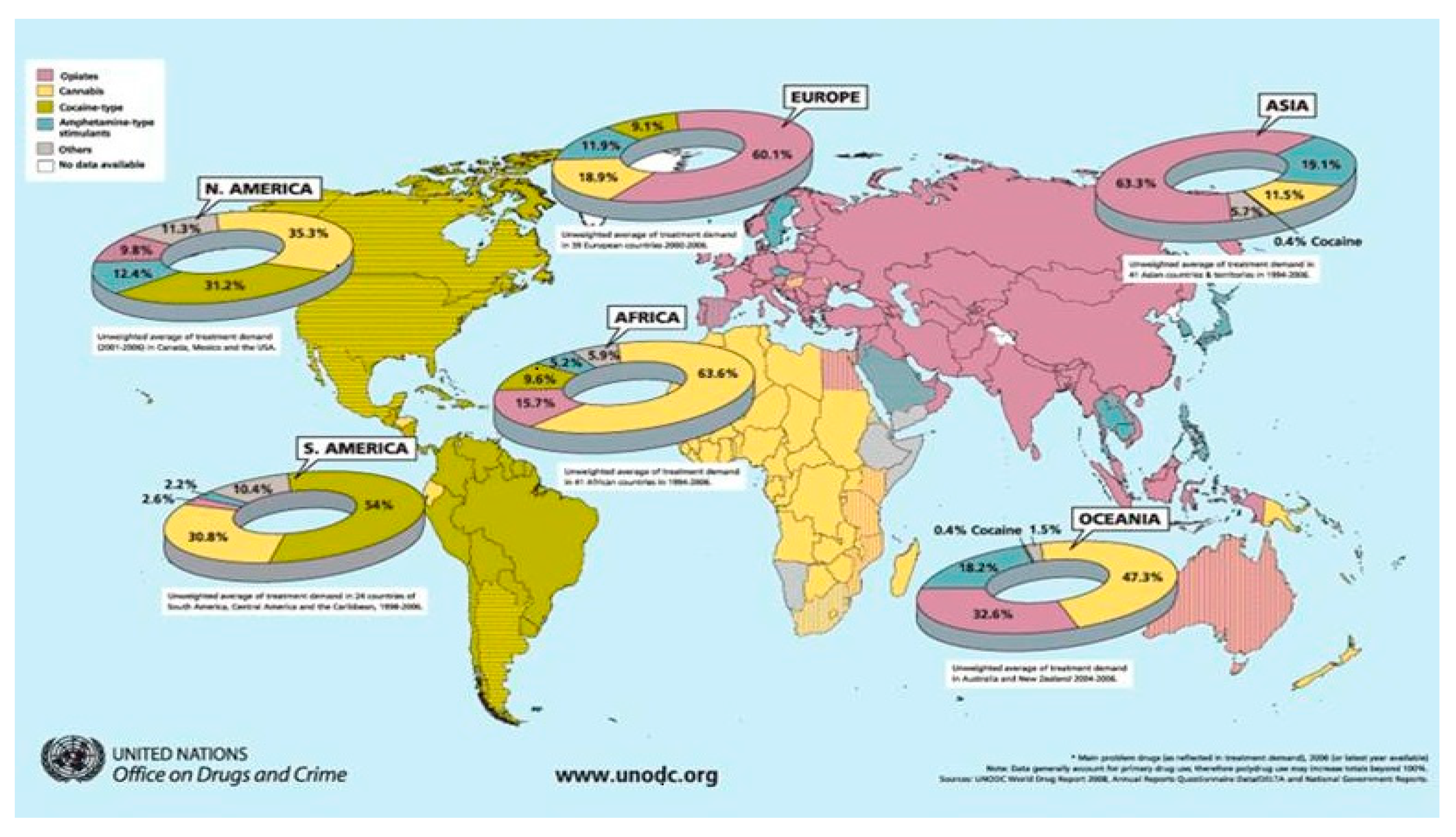

Figure 2.

Main drug problems (UNODC, 2024).

Figure 2.

Main drug problems (UNODC, 2024).

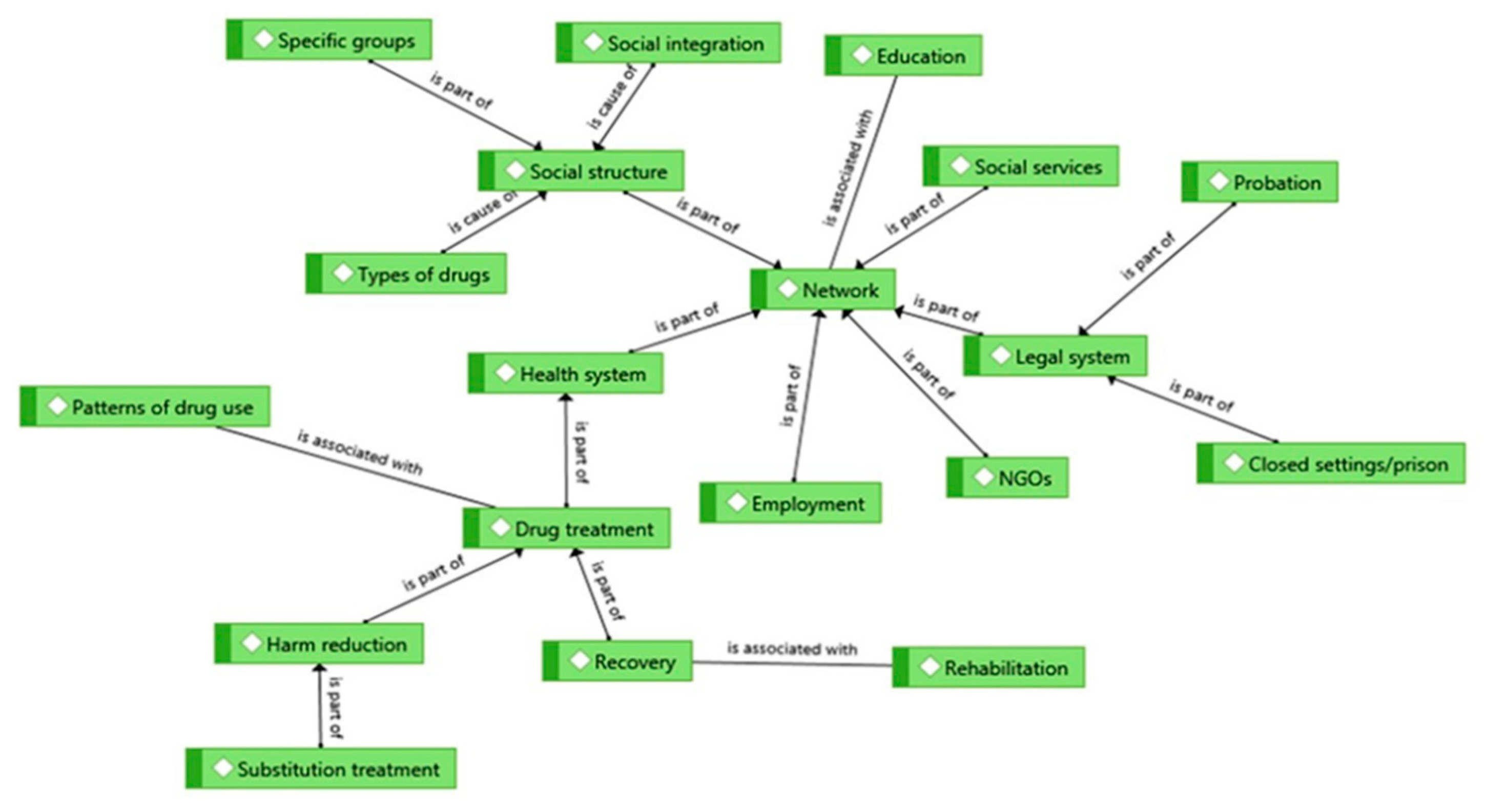

The effects of wars on the treatment of addictive behaviors and the heightened vulnerability to drug use disorders have been thoroughly documented in various contexts. The addiction treatment programs are essentially separated into recovery-based programs and harm reduction programs (Molina et al., 2022). While "Recovery" is a concept used to contextualize a process of treatment, addiction rehabilitation, and subsequent social reintegration, harm reduction programs seek to minimize the primary negative consequences of drug addiction, particularly the aftermath of associated infections and criminal behaviors related to substance use (Molina et al., 2022).

Figure 3.

European Standard Treatment Network (Molina et al., 2022).

Figure 3.

European Standard Treatment Network (Molina et al., 2022).

Key risk factors contributing to increased drug use among internally displaced persons and refugees include exposure to trauma and limited access to economic opportunities (UNODC, 2024). For instance, a drug use survey conducted in Afghanistan revealed that most individuals who injected drugs began this practice while they were refugees (UNODC, 2009). Similarly, studies in Colombia have highlighted a high lifetime prevalence of drug use and injecting drug use among displaced individuals (Castaño et al., 2018). Furthermore, evidence suggests that in the context of armed conflict, drug use can significantly undermine healthcare systems, contributing to their deterioration. Also, it´s usual to find more difficulties in accessing treatment and higher levels of HIV transmission, resulting from increases in needle sharing (UNODC, 2024). Providing access to drug treatment services to internally displaced persons and refugees are also major challenges, while precarious economic circumstances may push users to resort to more harmful drug use behaviours (UNODC, 2024).

The aim of this paper delves into the implications of warfare on drug use worldwide, with a particular focus on the conflict in Ukraine and its effects on drug consumption, as well as the situation in Gaza and the rise of captagon abuse. By examining these instances from a public health perspective, this study aims to underscore the urgent need for international collaboration and targeted interventions to address the detrimental effects of war on drug abuse and overall societal well-being.As a secondary aim, the prospective perspective will be used to determinate the risks and processes for next future in the use of these substances.

2. Materials and Methods

This study adopts a qualitative approach, drawing on existing literature, reports from international organizations such as the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), the World Health Organization (WHO), and academic research. It also examines case studies to explore how armed conflicts influence drug consumption patterns. Where available, statistical data are included to provide a clearer picture of drug use during and after periods of conflict.

Methodology

The research methodology is grounded in the method of historical logic, which serves as the foundation for analysis and reflection (Moradiellos, 2009). A qualitative content analysis approach was used, supplemented by secondary data, focusing on historical trends related to opioid use and abuse. Additionally, the study employs critical discourse analysis (CDA) as a key analytical method, incorporating feedback from researchers involved in the process. This section highlights the importance of both discourse analysis (DA) and its critical variant (CDA). According to Gee (2014), DA investigates how language is used to convey messages, carry out actions, and define social identities and relationships. DA methods range from descriptive to critical, the latter aiming to go beyond understanding language by examining its role in power dynamics and social structures. Gee notes that while some criticize critical approaches for lacking scientific objectivity, proponents argue that CDA is essential for addressing societal injustices. Critical approaches advocate for active engagement, ethical reflection, and a commitment to challenging simplistic or dogmatic views. The goal is to promote social inclusion based on widely accepted ethical standards. Van Dijk, a key figure in CDA, outlines eight defining principles of the critical discourse approach (see Table 1 below).

It can be argued that every academic discipline inherently reflects a particular "paradigm," whether its practitioners are aware of it or not. Consequently, to be more precise, the analytical framework of this article might be better described as *Critical Discipline Discourse Analysis* (CDDA), as this term more accurately conveys the focus of the study (Wodak, 2001). CDDA is used here to examine three community-centered disciplines by analyzing key texts and comparing them across the following dimensions:

- Definition of conceptual levels

- Philosophical foundations

- Strategic/methodological approaches

- Mechanisms for performance measurement and monitoring

One potential critique of this method concerns the possibility of bias in the selection of source materials. This concern is addressed in two ways: First, the study deliberately selects influential and representative texts from each of the three disciplines in order to construct a well-grounded argument. Second, an earlier draft of the article was reviewed by seven scholars, each representing one of the disciplines under study (with some having interdisciplinary expertise). Their feedback was used to assess the validity and clarity of the arguments and to further refine the article.

Nonetheless, it is acknowledged that within each of these disciplines, diverse viewpoints exist, many of which may be shaped by underlying ideological positions (Fairclough & Wodak, 1997).

3. Results

3.1. The War in Ukraine and Drug Consumption

The Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 has profoundly impacted drug use trends within the country and across neighboring regions. The ongoing conflict has heightened psychological distress among civilians and military personnel, prompting a surge in substance use as a coping mechanism. Reports indicate growing demand for opioids, stimulants, and synthetic drugs, especially among displaced populations and soldiers on the front lines. At the same time, the war has disrupted law enforcement operations, weakening drug control mechanisms and facilitating increased trafficking throughout Eastern Europe. Organized crime groups have taken advantage of the instability to expand their influence, leading to broader availability of illicit substances. This conflict not only endangers individuals who use drugs but also undermines regional efforts to regulate drug markets.Additionally, the war has severely affected access to essential medicines and medical supplies, putting drug treatment services at risk for both Ukrainians and refugees. While shifting geopolitical dynamics may alter established trafficking routes, the conflict is expected to further destabilize the region, reinforcing the conditions that enable drug production and distribution. These developments will likely shape future patterns of drug use and trafficking. Prior to the current war, Ukraine was already contending with some of the highest rates of intravenous drug use and HIV prevalence in the world. Between 2018 and 2020, it was estimated that roughly 350,000 adults—or 1.7% of the adult population—were injecting drugs, primarily opioids such as heroin and methadone, most of which are sourced from the black market.

Among this population, approximately 22.6% are living with HIV, and over half (55%) are infected with hepatitis C. These figures have remained relatively stable since 2011. In recent years, however, there has been a marked increase in the use of stimulants such as methamphetamine and novel psychoactive substances (NPS). Since 2015, synthetic cathinones like mephedrone and MPVP have gained popularity, largely due to a decline in opioid availability, the rise of homemade methamphetamine, and easier access to synthetic drugs. In Ukraine, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) have played a central role in reducing drug-related harm. By May 2021, approximately 15,700 individuals were enrolled in opioid agonist treatment (OAT), with women representing 16% of this group. By February 2022, that figure had risen to 17,210, making it the highest number of OAT recipients in Eastern Europe and Central Asia. Most participants were men, many of whom remained in the country despite the outbreak of war. Notably, Ukraine stood out as the only country in the region where naloxone—a life-saving medication used to reverse opioid overdoses—was available without a prescription.

Figure 4.

Cocaine trafficking in Ukraine (Source: The New World Order, 2024).

Figure 4.

Cocaine trafficking in Ukraine (Source: The New World Order, 2024).

3.2. The War in Middle East and Captagon Consumption

Syria has a long history of hashish production, but the drug that has come to define the ongoing crisis is the amphetamine-type stimulant Captagon. While relatively unknown outside the Middle East, Captagon has gained notoriety during the Syrian conflict. Originally developed in the 1960s for conditions like ADHD, narcolepsy, and depression, Captagon was once widely used but fell out of favor by the 1980s. The drug enhances alertness, boosts energy, suppresses appetite, and alleviates anxiety, effects similar to other stimulants commonly used in conflict zones. For soldiers, Captagon serves as a "force multiplier," helping them cope with fatigue and monotony during long missions. Often dubbed "chemical courage," Captagon is depicted in media as a substance that turns users into "superhuman soldiers" or "zombie-like" figures.

Since the onset of the Syrian conflict, the country has been mired in a complex crisis, involving foreign military interventions, large-scale displacement, violent extremism, and a breakdown of traditional conflict-resolution mechanisms. Alongside these challenges, Syria has also emerged as a significant narco-state, with drug production and trafficking playing a major role in the war's dynamics. Since 2018, narcotics trafficking has expanded, particularly as the government regained control over much of the country. The destruction of traditional economic systems has driven many to profit from the drug trade, with networks linked to the Assad regime and its allies capitalizing on the situation. While the extent of these trafficking networks remains under-studied, this report aims to initiate a conversation on the growing role of narcotics in the Syrian conflict and its impact on a post-conflict society. Since the war began, drug use in Syria has significantly increased. A study found that 8% of respondents reported drug use after 2011, compared to just 3% before the conflict. Prescription drug misuse has also risen, from 3% to 6%. Drug use is most prevalent in asylum countries (20%), followed by government-controlled areas (11%) and opposition-controlled regions (5%). The highest increases in drug use and prescription medication misuse were seen in government-controlled areas.

Drug users in Syria are primarily male (11% post-2011) compared to female users (4% post-2011). The highest rise in drug use has been reported among younger adults (18-29 years), with a 300% increase in this age group. The most commonly used substances include cannabis, opioids (such as tramadol), and amphetamines like Captagon. Prescription drugs, including Tramadol, Xanax, and Valium, are widely misused, often due to easy access and a lack of regulation. These drugs are cheap and widely available, even in impoverished areas, with dealers utilizing social media to distribute them.

Poverty, unemployment, and a search for financial security drive many individuals toward drug use, with vulnerable groups such as widows and teenagers being particularly targeted by drug dealers. Psychological distress, displacement, and a need to escape reality also contribute to rising drug use, particularly among fighters who use stimulants to stay alert during combat. Although drug use is still largely seen as socially unacceptable, with 74% of respondents rejecting it, younger generations are less likely to do so. The increase in drug use has led to heightened crime, social instability, and health problems. In opposition-controlled areas, half of the murder cases were linked to drug abuse. The civil war has caused widespread displacement, destruction, and economic collapse, creating conditions that foster substance abuse. Forced displacement campaigns have exacerbated psychological stress, increasing the risk of drug use among refugees and internally displaced persons.

The conflict has also strained Syria's medical sector, leading to shortages of supplies and personnel, as well as lax oversight of prescription medications. Some healthcare providers and patients have developed dependencies due to improper dispensing practices. These issues highlight the growing drug abuse epidemic in Syria, worsened by the ongoing war, economic collapse, and the lack of adequate regulation and rehabilitation services. The destruction of healthcare infrastructure has led to a dramatic shortage of medical personnel, with up to 70% of healthcare providers fleeing the country. The healthcare crisis has contributed to the spread of communicable diseases and increased mortality rates. The conflict has also led to widespread mental health issues, including depression, anxiety, and PTSD, with many Syrians lacking access to mental health care. Refugees and internally displaced persons face significant psychological distress as well. Substance use has surged, particularly prescription medication dependence, while the drug market has expanded, further exacerbating the epidemic. There are ongoing efforts to curb drug use, such as awareness campaigns, rehabilitation centers, and legal actions targeting drug dealers and trafficking networks. Awareness campaigns aim to educate the public about the dangers of substance abuse, while rehabilitation centers offer treatment, though many face operational challenges. Legal actions include security operations to combat drug trafficking. The growing interest in drugs among young Syrians has been fueled by the harsh realities of having to abandon education and enter the workforce at a young age, leading to a pervasive sense of hopelessness. Previously, Syrian youth might have rebelled through smoking or alcohol consumption, but opioids like dextropopoxyphene became more popular, with young people escalating from taking small doses to consuming entire packages in search of a euphoric high. This has led many to experiment with other substances, including codeine-containing cough syrup.

In response to this crisis, the Syrian Ministry of Health implemented restrictions on certain medications, making them available only with a prescription. However, these drugs continued to circulate through informal channels. Healthcare professionals are now more attuned to the signs of addiction, and early intervention is crucial, especially for young people. Monitoring children and intervening at the first signs of drug abuse is essential to prevent further escalation. As the addiction crisis deepens, the Ministry of Health established an addiction treatment department within a public hospital, though the facility can only accommodate a limited number of individuals. The demand for treatment far exceeds the available resources, and those admitted are often discharged too quickly to receive adequate care for complex dependencies like heroin addiction.

4. Discussion

Wars create environments conducive to increased drug consumption due to multiple factors, including psychological trauma, economic hardship, and the breakdown of law enforcement. In the case of Ukraine, the war has led to heightened drug abuse as a coping mechanism among affected populations, while also facilitating the expansion of drug markets. Similarly, in Gaza and Syria, the war has fueled captagon use among fighters and civilians, worsening an already dire public health crisis. Addressing these issues requires a comprehensive approach involving international cooperation, mental health support, and strengthened drug control policies (Abazid et al., 2023).

The impact of the war in Ukraine on access to addiction treatment is an increasingly pressing issue. The conflict has sparked a humanitarian crisis, displacing millions and severely undermining the country's healthcare system. A report from the World Health Organization (WHO) highlights that the war has led to significant disruptions in health services, including those for addiction treatment. The destruction of hospitals and health centers, coupled with a shortage of medical personnel and supplies, has crippled the healthcare infrastructure. Moreover, the war has driven a surge in the use of addictive substances such as alcohol and opioids, as many individuals turn to these as coping mechanisms for the stress and anxiety caused by the ongoing conflict. This rising demand has contributed to an increasing prevalence of substance use disorders, intensifying the need for effective treatments. Unfortunately, access to these crucial services remains severely limited due to the war. A study published in the Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment indicated that even before the onset of the conflict, addiction treatment availability in Ukraine was low. The situation has only deteriorated since then, with many treatment centers either closed or operating at significantly reduced capacity. The lack of access to addiction treatment has particularly affected vulnerable populations, including women and children. A UNICEF report underscores that the war has heightened their risk of exploitation and abuse, including in relation to substance use (UNICEF, 2025).

Addressing the alarming rise of drug use in Syria is an urgent moral and humanitarian priority (Bouzo, 2023). The first crucial step is for the Syrian government to acknowledge the extent of the issue by gathering accurate data on drug usage across the nation. This includes understanding the scale of the problem, the types of drugs being used, and identifying the regions most impacted. With this information in hand, healthcare professionals and concerned parties can develop a comprehensive strategy to tackle the crisis effectively. Additionally, Syria must seek support from international organizations that possess the resources and expertise to navigate the complex challenges of drug use and abuse within the country. While the implementation of such initiatives may seem daunting, concrete action cannot begin until there is a clear understanding of the situation. If this is not addressed, the issue of addiction in Syria will only continue to escalate, especially as the state attempts to generate revenue through the export of these substances abroad (Abazid et al., 2023). Strengthening awareness campaigns, expanding access to rehabilitation centers, and implementing stricter regulations on drug trafficking would be options to decrease the impact of war. . International cooperation, maritime security, intelligence sharing, and promoting alternative livelihoods are fundamental strategies to combat the drug trade.

Limitations and Biases

One potential critique that arises is the possibility of bias in the selection of sources for the arguments presented. In response to this concern, two key points can be made. First, we have intentionally chosen important references that span the three disciplines under discussion in order to strengthen our argument. Second, we sought feedback on an earlier draft of this article from seven academics, each representing the three disciplines mentioned, many of whom possess cross-disciplinary expertise. Their insights were invaluable in refining and enhancing the ideas presented here. Nonetheless, it is important to acknowledge that each of these disciplines encompasses a variety of perspectives, which may also be shaped by ideological views (Fairclough and Wodak, 1997).

5. Conclusions

The availability component is crucial in explaining the enormous consumption of some addictive behaviors in our societies, but we believe that the mere fact that things are widely distributed commercially does not adequately explain how they are abused by particular people or social groups. We must steer clear of the one cause-one effect sequence and search for multifactorial and non-linear answers. Research, risk group identification, and intervention adaption to their needs and issues are currently crucial for the proper design and execution of programs. The wars in Ukraine and Syria are having a devastating effect on access to addiction treatment. It is crucial for the international community to support initiatives aimed at restoring health services, including addiction care, while addressing the specific needs of the most vulnerable groups. Although technology may appear to be an advance in human relationships and In conclusion, war remains a significant driver of drug consumption and trafficking. Policymakers must prioritize public health interventions to mitigate the adverse effects of conflicts on drug abuse. Enhanced support for mental health services, improved border control measures, and global cooperation in combating drug trafficking are essential steps in addressing this growing concern.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, AJMF.; methodology, AJMF.; investigation, EAA and BMG.; writing—original draft preparation, AJMF.; writing—review and editing, EAA and BMG.; visualizationEAA and BMG; supervision, AJMF. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the UCM for their support and help; Madri+d for the chance of making this activity into “La Semana de la Ciencia” in comunidad de Madrid; finally, Antonio Jesús Molina would like to give special thanks to Editorial Terra Ignota.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abazid, H., Abu-Farha, R., Alsayed, A. R., Barakat, M., & Al-Qudah, R. (2023). A comprehensive overview of substance abuse amongst Syrian individuals in an addiction rehabilitation center. Heliyon, 9(4), e14731. [CrossRef]

- Andreas, P. & Greenhill, K. (2011). Sex, Drugs, and Body Counts: The Politics of Numbers in Global Crime and Conflict. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. [CrossRef]

- Barrett, D., & Lines, R. (Eds.). (2023). Towards Drug Policy Justice: Harm Reduction, Human Rights and Changing Drug Policy Contexts (1st ed.). Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Baumer, E. P., & Wolff, K. T. (2012). Evaluating Contemporary Crime Drop(s) in America, New York City, and Many Other Places. Justice Quarterly, 31(1), 5–38. [CrossRef]

- Bouzo, E. (2023). The Wagner Group in Syria: Profiting Off Failed States. In Fıkra Forum (Vol. 21).

- Brombacher, D., Maihold, G., Müller, M., & Vorrath, J. (Eds.). (2022). Geopolitics of the Illicit: Linking the Global South and Europe (Weltwirtschaft und internationale Zusammenarbeit, 25). Baden-Baden: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KG. [CrossRef]

- Castaño, Guillermo, Sierra, Gloria, Sánchez, Daniela, Torres, Yolanda, Salas, Carolina, & Buitrago, Carolina. (2018). Trastornos mentales y consumo de drogas en la población víctima del conflicto armado en tres ciudades de Colombia. Biomédica, 38(Suppl. 1), 70-85. [CrossRef]

- Center for Operational Analysis and Research (2021). The Syrian Economy at War: Captagon, Hashish, and the Syrian Narco-State. COAR.

- Centre for the study of Democracy (2007). Organized Crime in Bulgaria: Trends and Markets. CSD.

- Fairclough, N., & Wodak, R. (1997). Critical Discourse Analysis. In T. van Dijk (Ed.), Discourse Studies: A Multidisciplinary Introduction (Vol. 2, pp. 258-284). London: Sage.

- Felbab-Brown, V. (2014). Shooting Up: Counterinsurgency and the War on Drugs.. (n.d.) >The Free Library. Retrieved Mar 17 2025 from https://www.thefreelibrary.com/Shooting+Up%3a+Counterinsurgency+and+the+War+on+Drugs.-a02529441446. Goodhand, J. (2005). “Frontiers and Wars: The Opium Economy in Afghanistan.”.

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation/IHME. (2024). Global Burden of Disease 2021: Findings from the GBD 2021 Study. Seattle, WA: IHME.

- International Narcotics Control Board/INCB (2024). Drugs Report 2023. International Narcotics Control Board, United Nations, Vienna.

- Khalaf, R. (2020). “Captagon and the War Economy in Syria.” *Middle East Policy, 27*(3), 55-67.

- MacCoun, R., & Reuter, P. (2001). *Drug War Heresies: Learning from Other Vices, Times, and Places.* Cambridge University Press.

- Mansfield, D. (2016). *A State Built on Sand: How Opium Undermined Afghanistan.* Oxford University Press.

- Maté, G. (2008). *In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters with Addiction.* Knopf Canada.

- McCoy, A. W. (2003). *The Politics of Heroin: CIA Complicity in the Global Drug Trade.* Lawrence Hill Books.

- Molina-Fernández, A. (2024). El futuro de las drogas. Editorial Terra Ignota. ISBN 978-84-127558-7-9.

- Molina-Fernández, A., Medrano Chapinal, P. y Comellas Sanz, P. (2022a). Consecuencias psicosociales de la regulación del cannabis: un estudio cualitativo. Health and Addictions / Salud y Drogas, 22(2), 10-21. [CrossRef]

- Molina-Fernández, A.J., Feo-Serrato. M.L. y Serradilla-Sánchez, P. (2022b). Impact evaluation of European strategy on Spanish National Plan on Drugs and the role of civil society. Adicciones. [CrossRef]

- Molina, A., Saiz, J., Gil, F. & Cuenca, M. L. (2021). Models of Recovery: Influence of Psychosocial Factors on Substance Use Recovery. Journal of Substance Use. [CrossRef]

- Molina, A., Saiz, J., Gil, F., Cuenca, M. L. y Goldsby, T. (2020). Psychosocial Intervention in European Addictive Behaviour Recovery Programmes: A Qualitative Study. Healthcare, 8(3), 268. [CrossRef]

- Molina Fernández, A.J., Saiz Galdós, J., Cuenca Montesino, M. L., Gil Rodríguez, F., Mena García, B., & Rodríguez Hansen, G. (2022). Recovery programmes for intervention about substances abuse disorders: european good practices. Revista Española de Drogodependencias, 47(1), 47-60. [CrossRef]

- Molina, A., Saiz, J., Gil, F. & Cuenca, M. L. (2021). Models of Recovery: Influence of Psychosocial Factors on Substance Use Recovery. Journal of Substance Use. [CrossRef]

- Moradiellos, E. (2009). Las caras de Clío: una introducción a la Historia. Madrid: Ed. Siglo XXI. ISBN 9788432314025.

- Reuter, P., & Pollack, H. A. (2012). How Much Can Treatment Reduce National Drug Problems? Addiction, 107(6), 978-985.

- Sahloul, M. Z., Albaba, D., Bizri, M., Rayes, D., Rose, C., Taktak, H., Draper, I., Shalaby, O., Al-Edou, M., Shabib, Q., Saadoon, N., Al Ghawi, H., Al Karrat, Z., Al Jundi, M., Hatahet, B., Alsaad, H., Al-Mhamied, A., & Al-Saoor, A. (2022). UNDER THE SURFACE: A DECADE OF CONFLICT AND THE DRUG USE EPIDEMIC INSIDE SYRIA.. MedGlobal.

- Shaw, M. (2016). “Drug Trafficking and Political Orders in Conflict Zones.” *Journal of Illicit Economies and Development, 1*(1), 19-34.

- UNICEF (2025). Three years of full-scale war in Ukraine. UNICEF.

- UNODC. (2024). World Drug Report 2023. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

- UNODC (2009). Drug Use in Afghanistan: 2009 Survey Executive summary. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

- Zdanowicz, C. (2022). “Ukraine War Increases Risk of Drug Trafficking in Eastern Europe.” *Global Drug Policy Observatory Reports, 34*(2), 67-80.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).