Submitted:

29 April 2025

Posted:

29 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Chemicals

2.2. Cell Culture

2.3. MTT Assay for Cell Viability

2.4. Colony Formation Assay

2.5. Cell Cycle Analysis

2.6. Terminal Deoxynucleotidyl Transferase dUTP Nick end Labeling (TUNEL) Analysis

2.7. Western Blot

2.8. Determination of Intracellular ROS

2.9. Overexpression of Akt in Cancer Cells

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

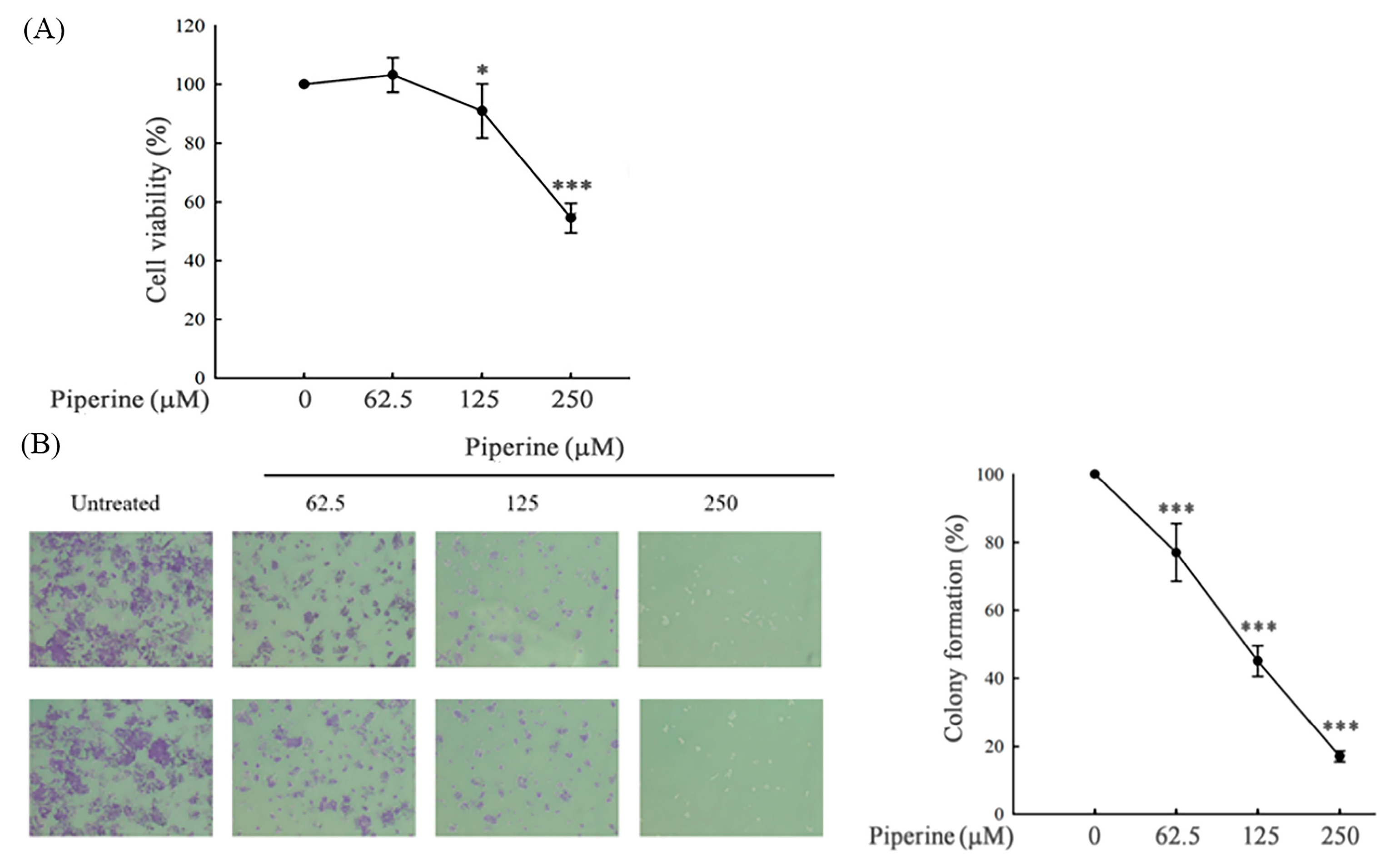

3.1. Piperine Inhibits Cell Viability and Colony Formation in DLD-1 Cells

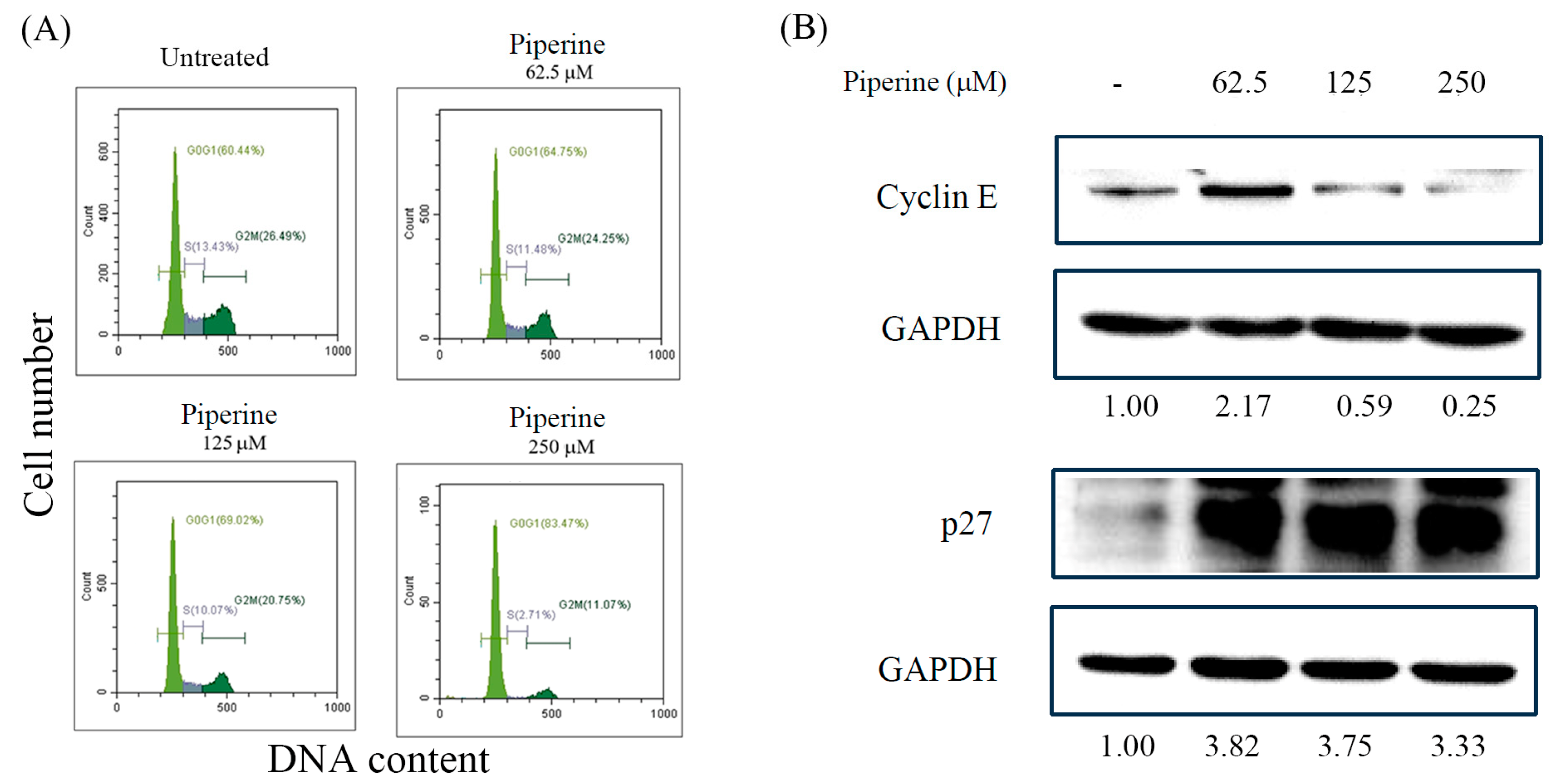

3.2. Piperine Induces Cell Cycle Arrest in DLD-1 Cells

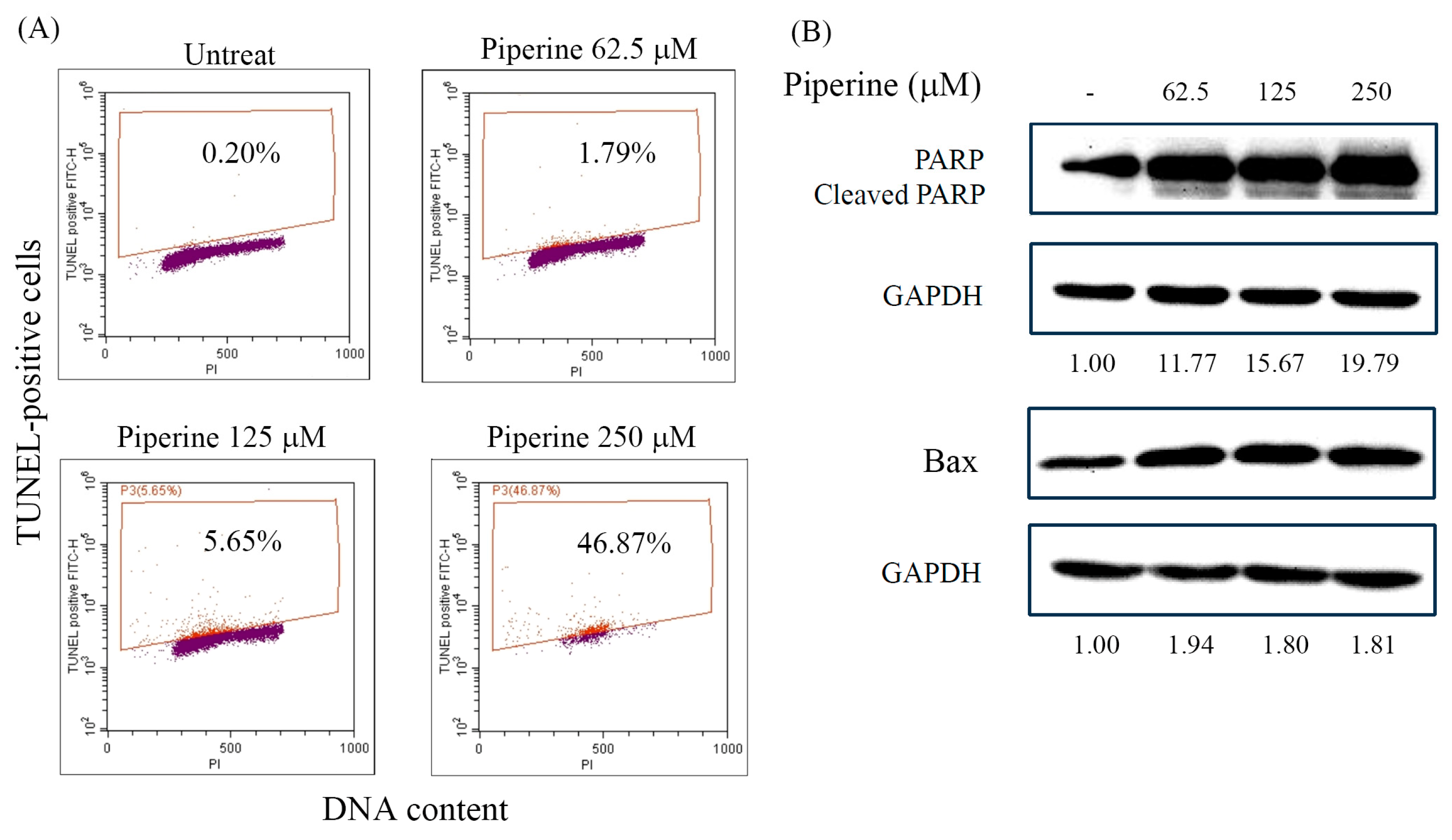

3.3. Piperine Induces Apoptosis in DLD-1 Cells

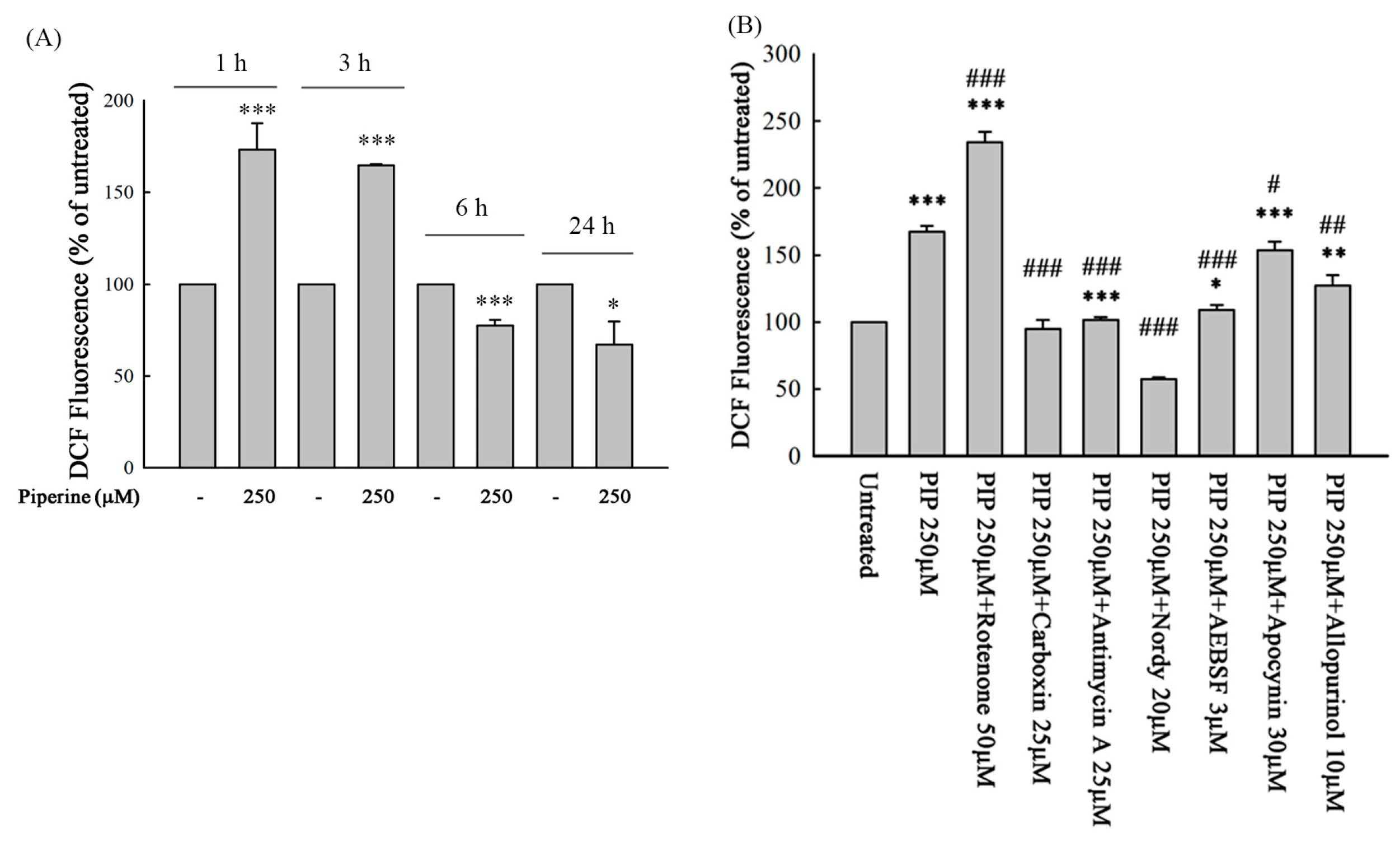

3.4. Piperine Induces ROS in DLD-1 Cells

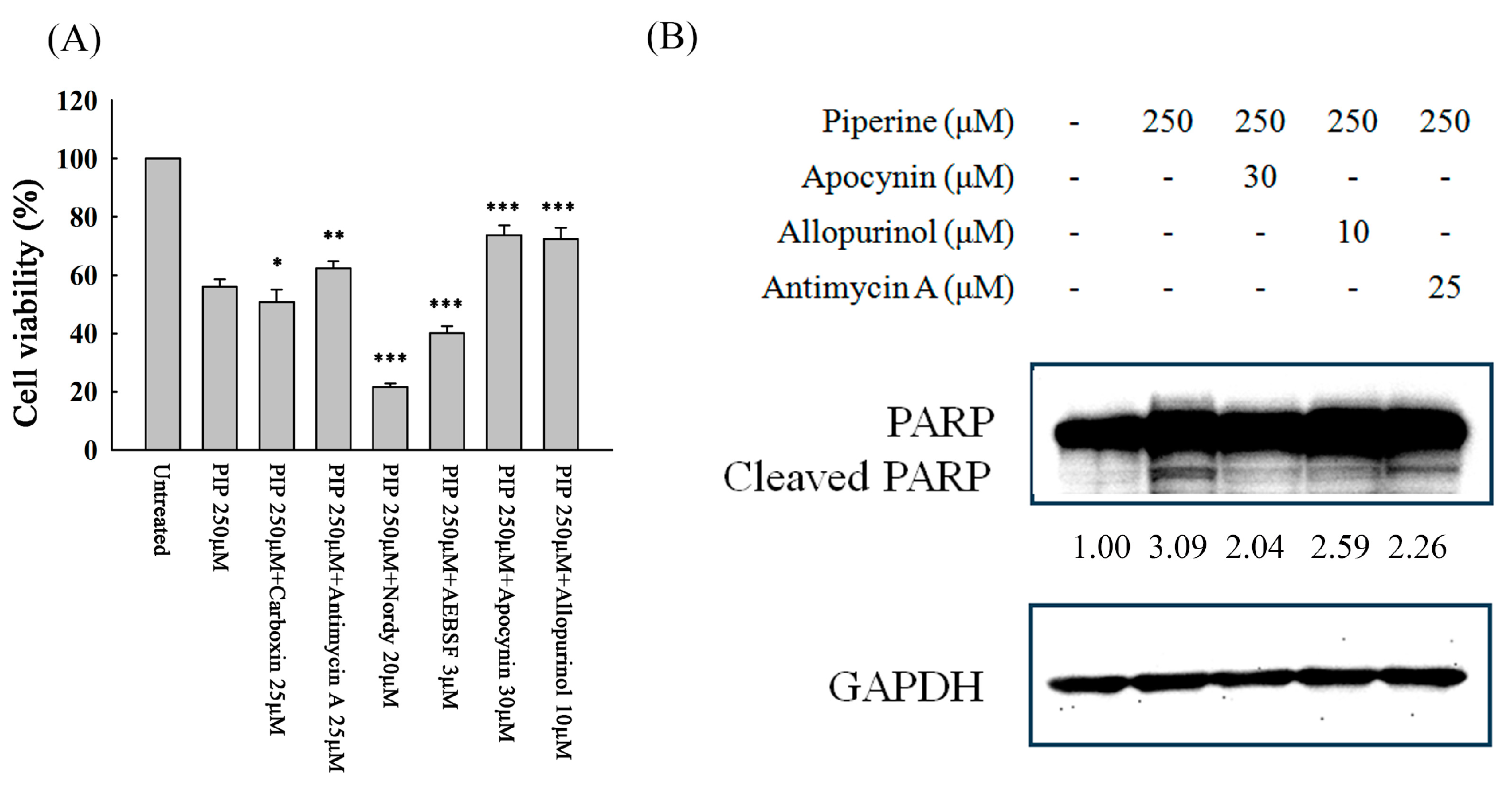

3.5. Piperine-Mediated ROS Induces Cell Death and Apoptosis in DLD-1 Cells

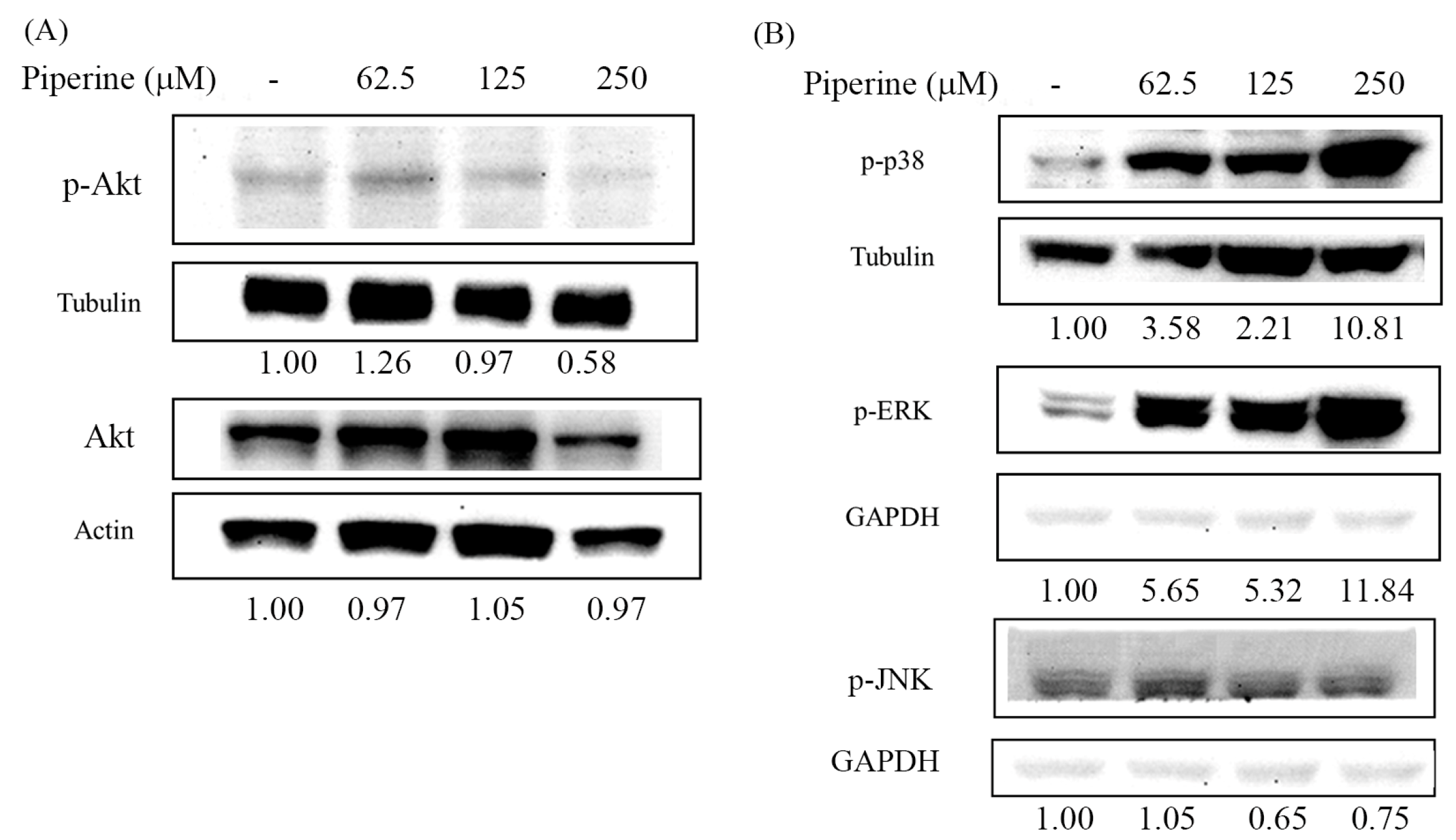

3.6. Piperine Inhibits p-Akt and Regulates MAPKs in DLD-1 Cells

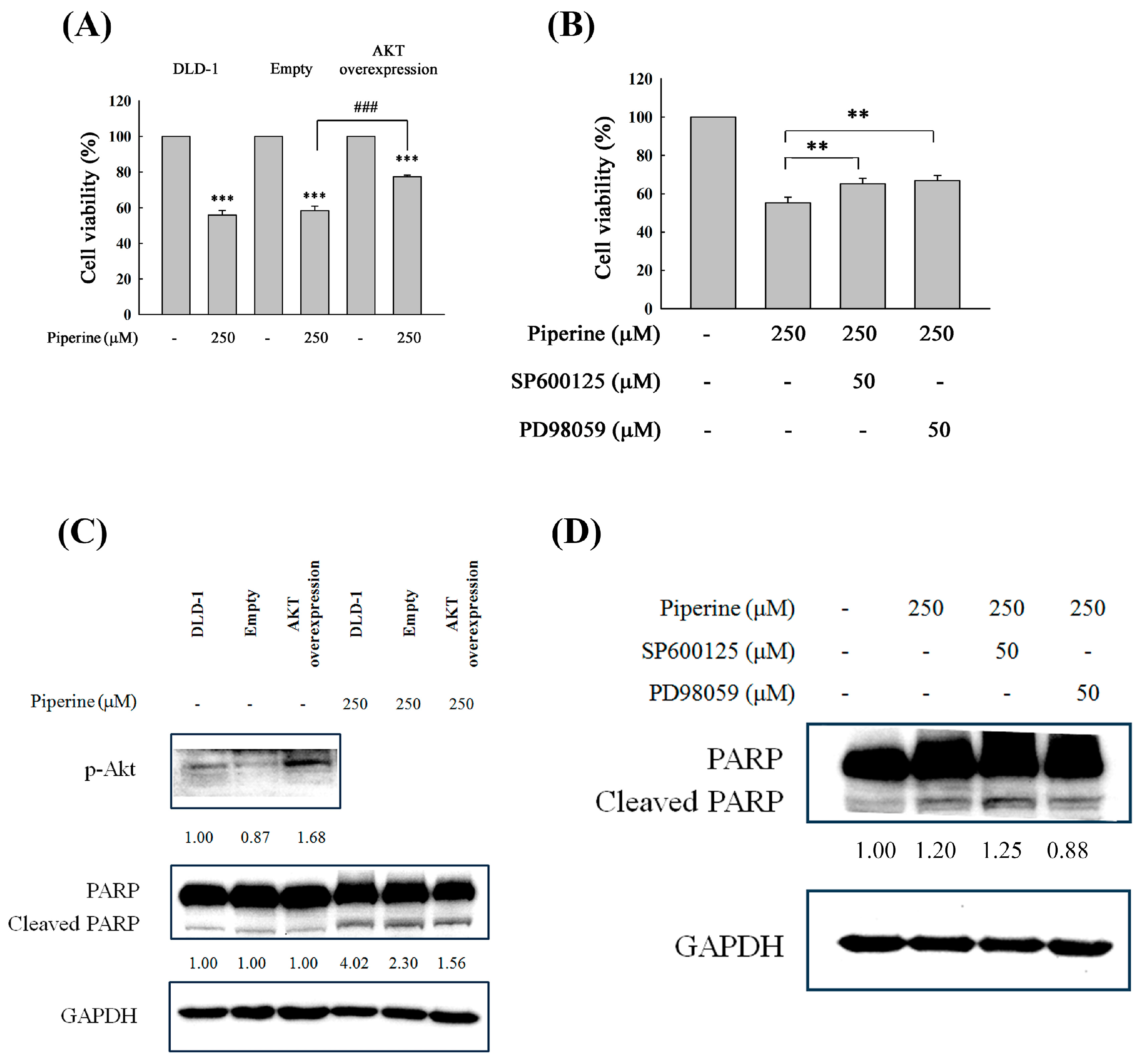

3.7. Piperine Induces Apoptosis through Akt and ERK Signaling Regulation

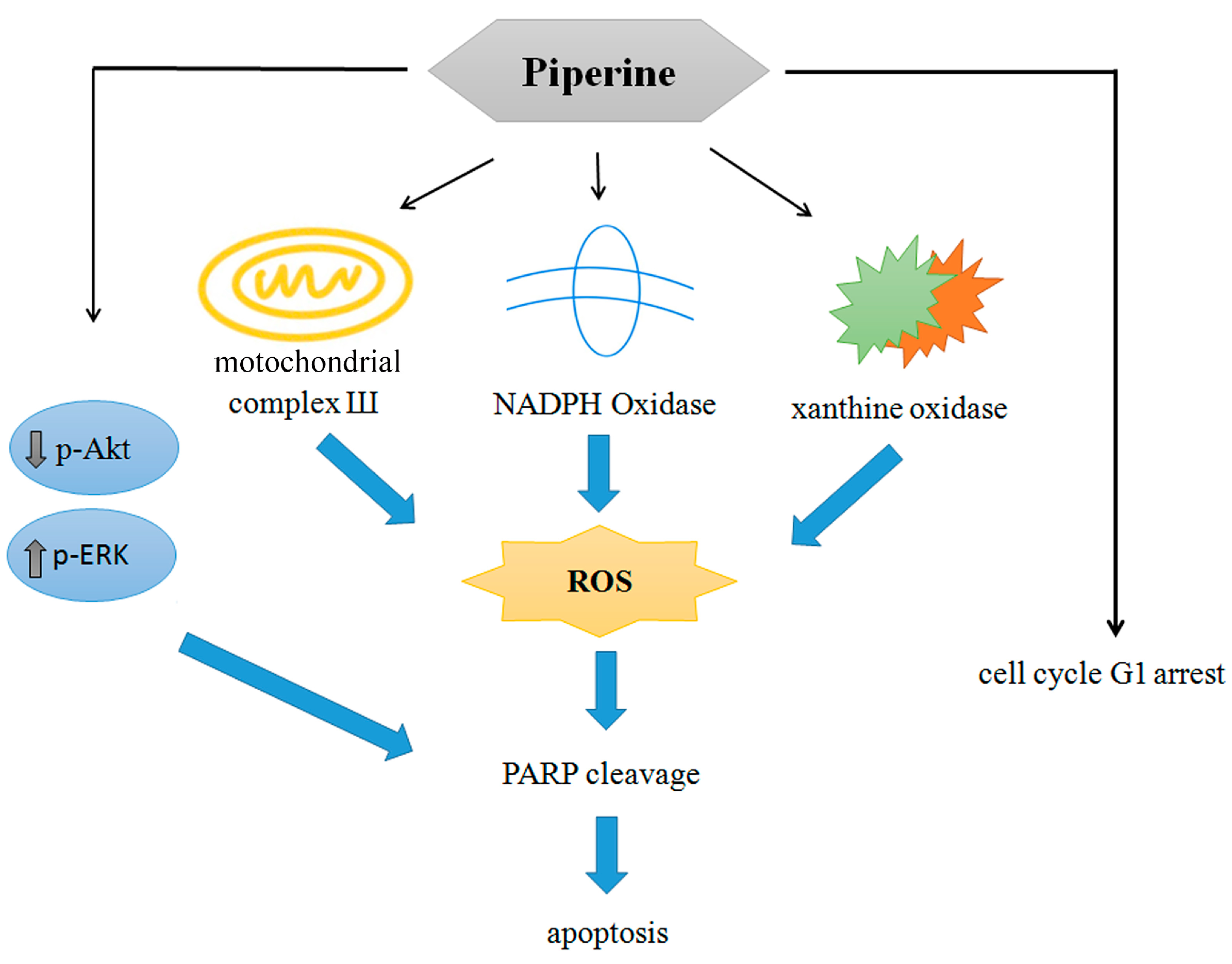

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yaffe, P.B.; Doucette, C.D.; Walsh, M.; Hoskin, D.W. Piperine impairs cell cycle progression and causes reactive oxygen species-dependent apoptosis in rectal cancer cells. Exp Mol Pathol. 2013, 94, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, J.; Guo, P.; Yang, J.; Zhang, T.; Pan, K.; Wei, H. Piperine induces autophagy of colon cancer cells: Dual modulation of AKT/mTOR signaling pathway and ROS production. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2024, 728, 150340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Qian, Y.; Jiang, J.; Li, D.; Feng, L. Piperine inhibits the proliferation of colorectal adenocarcinoma by regulating ARL3- mediated endoplasmic reticulum stress. Biomol Biomed. 2024, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida, G.C.; Oliveira, L.F.S.; Predes, D.; Fokoue, H.H.; Kuster, R.M.; Oliveira, F.L.; Mendes, F.A.; Jose, G.; Abreu, J.G. Piperine suppresses the Wnt/β-catenin pathway and has anti-cancer effects on colorectal cancer cells. Sci Rep. 2020, 10, 11681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaheer, K.; Somashekarappa, H.M.; Lakshmanan, M.D. Piperine sensitizes radiation-resistant cancer cells towards radiation and promotes intrinsic pathway of apoptosis. J Food Sci. 2020, 85, 4070–4079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharjya, D.; Sivalingam, N. Mechanism of 5-fluorouracil induced resistance and role of piperine and curcumin as chemo-sensitizers in colon cancer. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Dewangan, J.; Mishra, S.; Divakar, A.; Chaturvedi, S.; Wahajuddin, M.; Kumar, S.; Rath, S.K. Piperine and Celecoxib synergistically inhibit colon cancer cell proliferation via modulating Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Phytomedicine. 2021, 84, 153484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, B.M.; Banik, B.K.; Borah, P.; Jain, A. Reactive oxygen species (ROS): Key components in cancer therapies. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2022, 22, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirichen, H.; Yaigoub, H.; Xu, W.; Wu, C.; Li, R.; Li, Y. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and their contribution in chronic kidney disease progression through oxidative stress. Front Physiol. 2021, 12, 627837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peshavariya, H. NADPH oxidase-derived ROS signaling and therapeutic opportunities. Curr Pharm Des. 2015, 21, 21,5931–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Li, C.; Mozziconacci, O.; Zhu, R.; Xu, Y.; Tang, Y.; Chen, R.; Huang, Y.; Holzbeierlein, J.M.; Schöneich, C.; Huang, J.; Li, B. Xanthine oxidase-mediated oxidative stress promotes cancer cell-specific apoptosis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2019, 139, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, C.; Laws, K.; Eskandari, A.; Suntharalingam, K. A reactive oxygen species-generating, cyclooxygenase-2 inhibiting, cancer stem cell-potent tetranuclear copper (ii) cluster. Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 12785–12789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Hu, J.; Lv, Y.; Bai, B.; Shan, L.; Chen, K.; Dai, S.; Zhu, H. Pyrvinium pamoate inhibits cell proliferation through ROS-mediated AKT-dependent signaling pathway in colorectal cancer. Med Oncol. 2021, 838, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, Y.T.; Lee, K.C.; Cheng, K.C.; Lee, K.F.; Yang, Y.L.; Chu, H.T.; Lin, T.W.; Chen, C.C.; Hsieh, M.C.; Huang, C.Y.; Kuo, H.C.; Teng, C.C. Antrodin C isolated from Antrodia Cinnamomea induced apoptosis through ROS/AKT/ERK/p38 signaling pathway and epigenetic histone acetylation of TNFα in colorectal cancer cells. Antioxidants (Basel). 2023, 12, 764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zhao, S.; Lu, X.; Shi, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhu, B. Metformin enhances the sensitivity of colorectal cancer cells to cisplatin through ROS-mediated PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Gene. 2020, 745, 144623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Yuan, X.; Yu, T.; Huang, H.; Yang, C.; Zhang, L.; Yang, S.; Luo, X.; Luo, J. Lycorine inhibits cell proliferation, migration and invasion, and primarily exerts in vitro cytostatic effects in human colorectal cancer via activating the ROS/p38 and AKT signaling pathways. Oncol Rep. 2021, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.; Lin, Z.; Shi, P.; Chen, B. Wang, G.; Huang, J.; Sui, Y.; Liu, Q.; Li, S.; Lin, X.; Liu, Q.; Yao, H. Delicaflavone induces ROS-mediated apoptosis and inhibits PI3K/AKT/mTOR and Ras/MEK/Erk signaling pathways in colorectal cancer cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2020, 171, 113680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, J.; Jin, L.; Lei, K.; Liu, H.; Yang, Y. Fibulin-5 contributes to colorectal cancer cell apoptosis via the ROS/MAPK and Akt signal pathways by downregulating transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1. J Cell Biochem. 2019, 120, 17838–17846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Jia, L.; Huang, C.; Qi, Q.; Jahangir, A.; Xia, Y.; Liu, W.; Shi, R.; Tang, L.; Chen, Z. Polyphyllin I Promotes Autophagic Cell Death and Apoptosis of Colon Cancer Cells via the ROS-Inhibited AKT/mTOR Pathway. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 9368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.Q.; Wang, Y.; Luo, Y.H.; Piao, X.J.; Liu, C,; Wang, Y. ; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.R.; Wang, H.; Xu, W.T.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Y.Q.; Sun, H.N.; Han, Y.H.; Jin, M.H.; Shen, G.N.; Fang, N.Z.; Jin, C.H. Quinalizarin induces apoptosis through reactive oxygen species (ROS)-mediated mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) signaling pathways in colorectal cancer cells. Med Sci Monit. 2018, 24, 3710–3719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Li, X.; Ho, C.T.; Lin, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, B.; Chen, Z. Cocoa tea (Camellia ptilophylla) induces mitochondria-dependent apoptosis in HCT116 cells via ROS generation and PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Food Res Int. 2020, 129, 108854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Jiang, H.; Xie, L.; Hu, J.; Li, L.; Yang, M.; Cheng, L.; Liu, B.; Qian, X. Antitumor effect of manumycin on colorectal cancer cells by increasing the reactive oxygen species production and blocking PI3K-AKT pathway. Onco Targets Ther. 2016, 9, 2885–2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D'Autréaux, B.; Toledano, M.B. ROS as signalling molecules: mechanisms that generate specificity in ROS homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 813–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmström, K.M.; Finkel, T. Cellular mechanisms and physiological consequences of redox-dependent signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014, 15, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, J.; Galano, J.M.; Durand, T.; Le Guennec, J.Y.; Lee, J.C. Physiological role of reactive oxygen species as promoters of natural defenses. FASEB J. 2017, 31, 3729–3745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reuter, S.; Gupta, S.C.; Chaturvedi, M.M.; Aggarwa,l B. B. Oxidative stress, inflammation, and cancer: how are they linked? Free Radic Biol Med. 2010, 49, 1603–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tafani, M.; Sansone, L.; Limana, F.; Arcangeli, T.; De Santis, E.; Polese, M.; Fini, M.; Russo, M.A. The Interplay of Reactive Oxygen Species, Hypoxia, Inflammation, and Sirtuins in Cancer Initiation and Progression. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016, 2016, 3907147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Galadari, S.; Rahman, A.; Pallichankandy, S.; Thayyullathil, F. Reactive oxygen species and cancer paradox: To promote or to suppress? Free Radic Biol Med. 2017, 104, 144–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weng, M.S.; Chang, J.H.; Hung, W.Y.; Yang, Y.C.; Chien, M.H. The interplay of reactive oxygen species and the epidermal growth factor receptor in tumor progression and drug resistance. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2018, 37, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jiang, Y.; Wang, X.; Hu, D. Furanodienone induces G0/G1 arrest and causes apoptosis via the ROS/MAPKs-mediated caspase-dependent pathway in human colorectal cancer cells: a study in vitro and in vivo. Cell Death Dis. 2017, 8, e2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gao, L.; Laude, K.; Cai, H. Mitochondrial pathophysiology, reactive oxygen species, and cardiovascular diseases. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2008, 38, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhao, R.Z.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, L.; Yu, Z.B. Mitochondrial electron transport chain, ROS generation and uncoupling (Review). Int J Mol Med. 2019, 44, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen, H.; Li, L.; Lu, Y.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, M.; Ge, L.; Wang, M.; Yang, J.; Tian, Z.; Tang, X. Azoxystrobin Reduces Oral Carcinogenesis by Suppressing Mitochondrial Complex III Activity and Inducing Apoptosis. Cancer Manag Res. 2020, 12, 11573–11583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liu, Y.; Yu, S.; Xing, X.; Qiao, J.; Yin, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, M.; Zhang, W. Ginsenoside Rh2 stimulates the production of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and induces apoptosis of cervical cancer cells by inhibiting mitochondrial electron transfer chain complex. Mol Med Rep. 2021, 24, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Uchihara, Y.; Tago, K.; Taguchi, H.; Narukawa, Y.; Kiuchi, F.; Tamura, H.; Funakoshi-Tago, M. Taxodione induces apoptosis in BCR-ABL-positive cells through ROS generation. Biochem Pharmacol. 2018, 154, 357–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Jiang, L.; Xu, M.; Liu, Q.; Gao, N.; Li, P.; Liu, E.H. Miltirone exhibits antileukemic activity by ROS-mediated endoplasmic reticulum stress and mitochondrial dysfunction pathways. Sci Rep. 2016, 6, 20585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kari, S.; Kandhavelu, J.; Murugesan, A.; Thiyagarajan, R.; Kidambi, S.; Kandhavelu, M. Mitochondrial complex III bypass complex I to induce ROS in GPR17 signaling activation in GBM. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023, 162, 114678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.S. The signaling mechanism of ROS in tumor progression. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2006, 25, 695–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juhasz, A.; Markel, S.; Gaur, S.; Liu, H.; Lu, J.; Jiang, G.; Wu, X.; Antony, S.; Wu, Y.; Melillo, G.; Meitzler, J.L.; Haines, D.C.; Butcher, D.; Roy, K.; Doroshow, J.H. NADPH oxidase 1 supports proliferation of colon cancer cells by modulating reactive oxygen species-dependent signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 2017, 292, 7866–7887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bánfi, B.; Clark, R.A.; Steger, K.; Krause, K.H. Two novel proteins activate superoxide generation by the NADPH oxidase NOX1. J Biol Chem. 2003, 278, 3510–3513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eom, J.W.; Lim, J.W.; Kim, H. Lutein Induces Reactive Oxygen Species-Mediated Apoptosis in Gastric Cancer AGS Cells via NADPH Oxidase Activation. Molecules. 2023, 28, 1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bhavya, K.; Mantipally, M.; Roy, S.; Arora, L.; Badavath, V.N.; Gangireddy, M.; Dasgupta, S.; Gundla, R.; Pal, D. Novel imidazo [1,2-a]pyridine derivatives induce apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in non-small cell lung cancer by activating NADPH oxidase mediated oxidative stress. Life Sci. 2022, 294, 120334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, X. Furanodienone induces apoptosis via regulating the PRDX1/MAPKs/p53/caspases signaling axis through NOX4-derived mitochondrial ROS in colorectal cancer cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2024, 227, 116456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhang, L.; Wu, M.; Zhang, F.; Yang, D.; Shen, J.; Chen, J. Glycyrrhetinic acid induces oxidative/nitrative stress and drives ferroptosis through activating NADPH oxidases and iNOS, and depriving glutathione in triple-negative breast cancer cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2021, 173, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winston, G.W.; Moore, M.N.; Kirchin, M.A.; Soverchia, C. Production of reactive oxygen species by hemocytes from the marine mussel, Mytilus edulis: lysosomal localization and effect of xenobiotics. Comp Biochem Physiol C Pharmacol Toxicol Endocrinol. 1996, 113, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.S.; Lu, L.Q.; Jiang, Y.Q.; Li, N.S.; Luo, X.J.; Peng, J. W, Peng, J. Allopurinol attenuates oxidative injury in rat hearts suffered ischemia/reperfusion via suppressing the xanthine oxidase/vascular peroxidase 1 pathway. Eur J Pharmacol. 2021, 908, 174368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meeran, S.M.; Katiyar, S.; Katiyar, S.K. Berberine-induced apoptosis in human prostate cancer cells is initiated by reactive oxygen species generation. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2008, 229, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.; Cheng, H.; Roberts, T.M.; Zhao, J.J. Targeting the phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway in cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009, 8, 627–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lee, M.H.; Hong, S.H.; Park, C.; Kim, G.Y.; Leem, S.H.; Choi, S.H.; Keum, Y.S.; Hyun, J.W.; Kwon, T.K.; Hong, S.H.; Choi, Y.H. Hwang-Heuk-San induces apoptosis in HCT116 human colorectal cancer cells through the ROS-mediated activation of caspases and the inactivation of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Oncol Rep. 2016, 36, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Fan, D. Ginsenoside Rg5 induces G2/M phase arrest, apoptosis and autophagy via regulating ROS-mediated MAPK pathways against human gastric cancer. Biochem Pharmacol. 2019, 168, 285–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; He, J.; Ye, X.; Zhu, J.; Hu, X.; Shen, M.; Ma, Y.; Mao, Z.; Song, H.; Chen, F. β-Thujaplicin induces autophagic cell death, apoptosis, and cell cycle arrest through ROS-mediated Akt and p38/ERK MAPK signaling in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, L.J.; Lee, Y.C.; Huang, C.H.; Shi, Y.J.; Chen, Y.J.; Pei, S.N.; Chou, Y.W.; Chang, L.S. Non-mitotic effect of albendazole triggers apoptosis of human leukemia cells via SIRT3/ROS/p38 MAPK/TTP axis-mediated TNF-α upregulation. Biochem Pharmacol. 2019, 162, 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, J.; Ren, D.; Wang, J.; Liu, X.; Zhang, H.; Wu, M.; Yang, G. Bruceine D induces lung cancer cell apoptosis and autophagy via the ROS/MAPK signaling pathway in vitro and in vivo. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Osone, S.; Hosoi, H.; Kuwahara, Y.; Matsumoto, Y.; Iehara, T.; Sugimoto, T. Fenretinide induces sustained-activation of JNK/p38 MAPK and apoptosis in a reactive oxygen species-dependent manner in neuroblastoma cells. Int J Cancer. 2004, 112, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Jiang, D.; Liu, J.; Ye, S.; Xiao, S.; Wang, W.; Sun, Z.; Xie, Y.; Wang, J. Compound K induces apoptosis of bladder cancer T24 cells via reactive oxygen species-mediated p38 MAPK pathway. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2013, 28, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cargnello, M.; Roux, P.P. Activation and function of the MAPKs and their substrates, the MAPK-activated protein kinases. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2011, 75, 50–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Darling, N.J.; Cook, S.J. The role of MAPK signalling pathways in the response to endoplasmic reticulum stress. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014, 1843, 2150–2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wada, T.; Penninger, J.M. Mitogen-activated protein kinases in apoptosis regulation. Oncogene. 23, 2838–2849. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, Y.H.; Kim, S.K.; Kwon, S.H.; Seo, J.Y.; Lee, B.R.; Kim, Y.J.; Hur, K.H.; Kim, S.Y.; Lee, S.Y.; Jang, C.G. 7,8,4'-Trihydroxyisoflavone, a Metabolized Product of Daidzein, Attenuates 6-Hydroxydopamine-Induced Neurotoxicity in SH-SY5Y Cells. Biomol Ther (Seoul). 2019, 27, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kulisz, A.; Chen, N.; Chandel, N.S.; Shao, Z.; Schumacker, P.T. Mitochondrial ROS initiate phosphorylation of p38 MAP kinase during hypoxia in cardiomyocytes. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002, 282, L1324–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, P.J.; Der, C.J. Targeting the Raf-MEK-ERK mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade for the treatment of cancer. Oncogene. 2007, 26, 3291–3310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastola, T.; An, R.B.; Kim, Y.C.; Kim, J.; Seo, J. Cearoin Induces Autophagy, ERK Activation and Apoptosis via ROS Generation in SH-SY5Y Neuroblastoma Cells. Molecules. 2017, 22, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cagnol, S.; Chambard, J.C. ERK and cell death: mechanisms of ERK-induced cell death--apoptosis, autophagy and senescence. FEBS J. 2010, 277, 2–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).