Submitted:

28 April 2025

Posted:

29 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

1.1.1. Emerging Trends in Sales Force Training

1.1.2. The Impact of Virtual Reality on B2B Customer Experience and Sales Training

1.1.3. The Impact of Virtual Reality on B2B Customer Experience and Sales Training

1.2. Aim of the Research and Research Questions

2. Materials and Methods

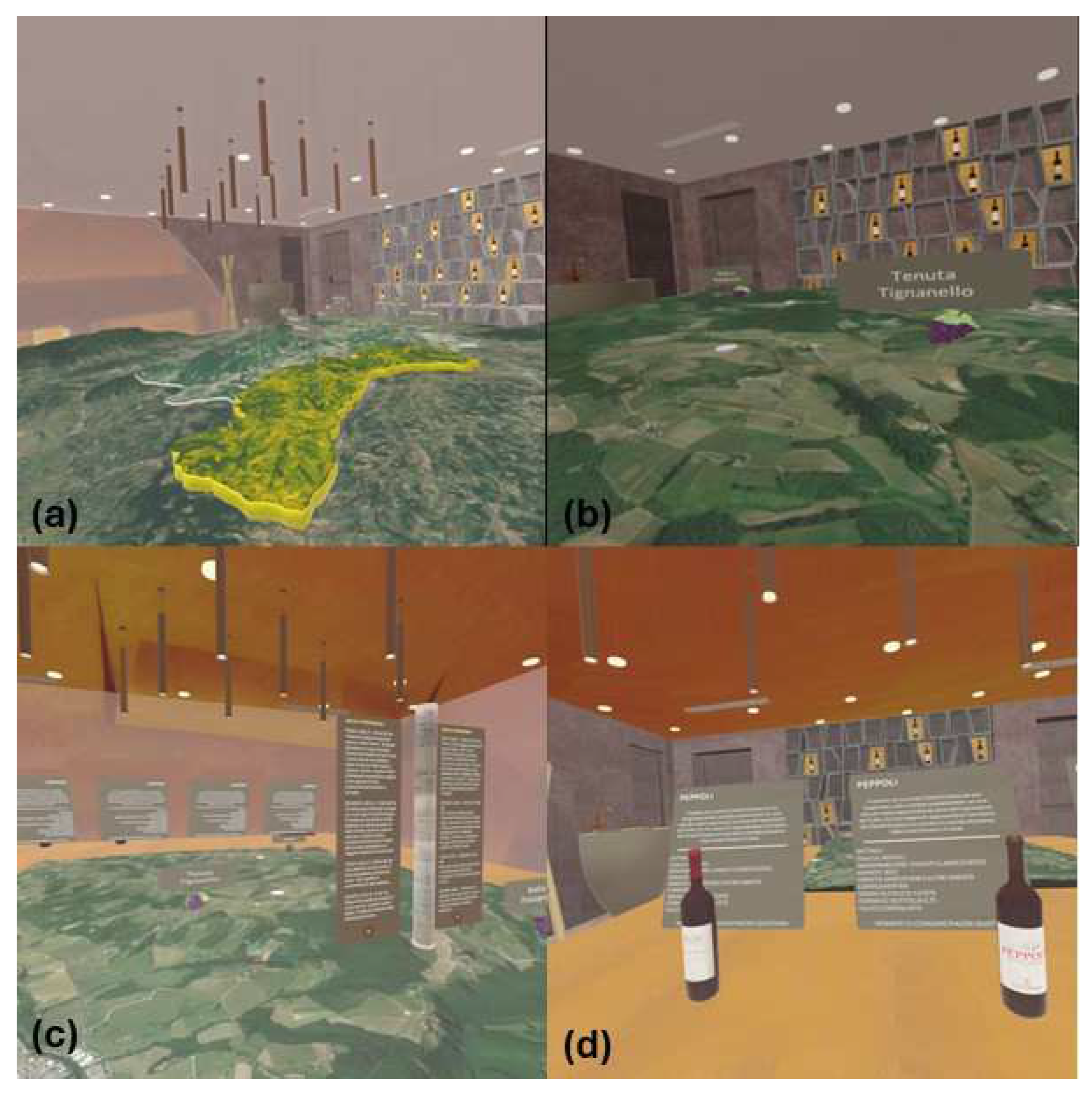

2.1. Case Study Overview

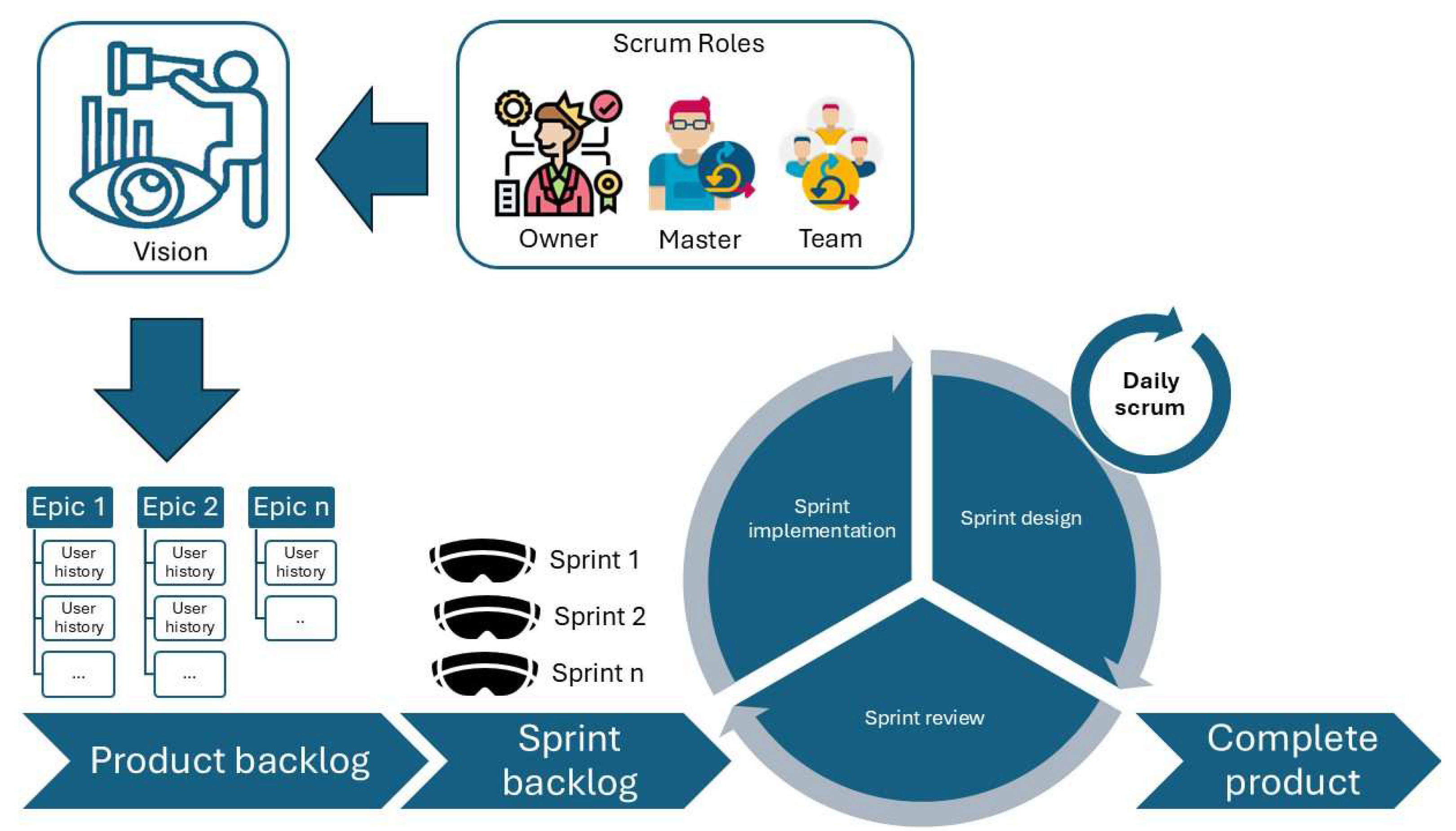

2.2. The Scrum Framework

2.3. App Evaluation

2.3.1. Focus Group Methodology

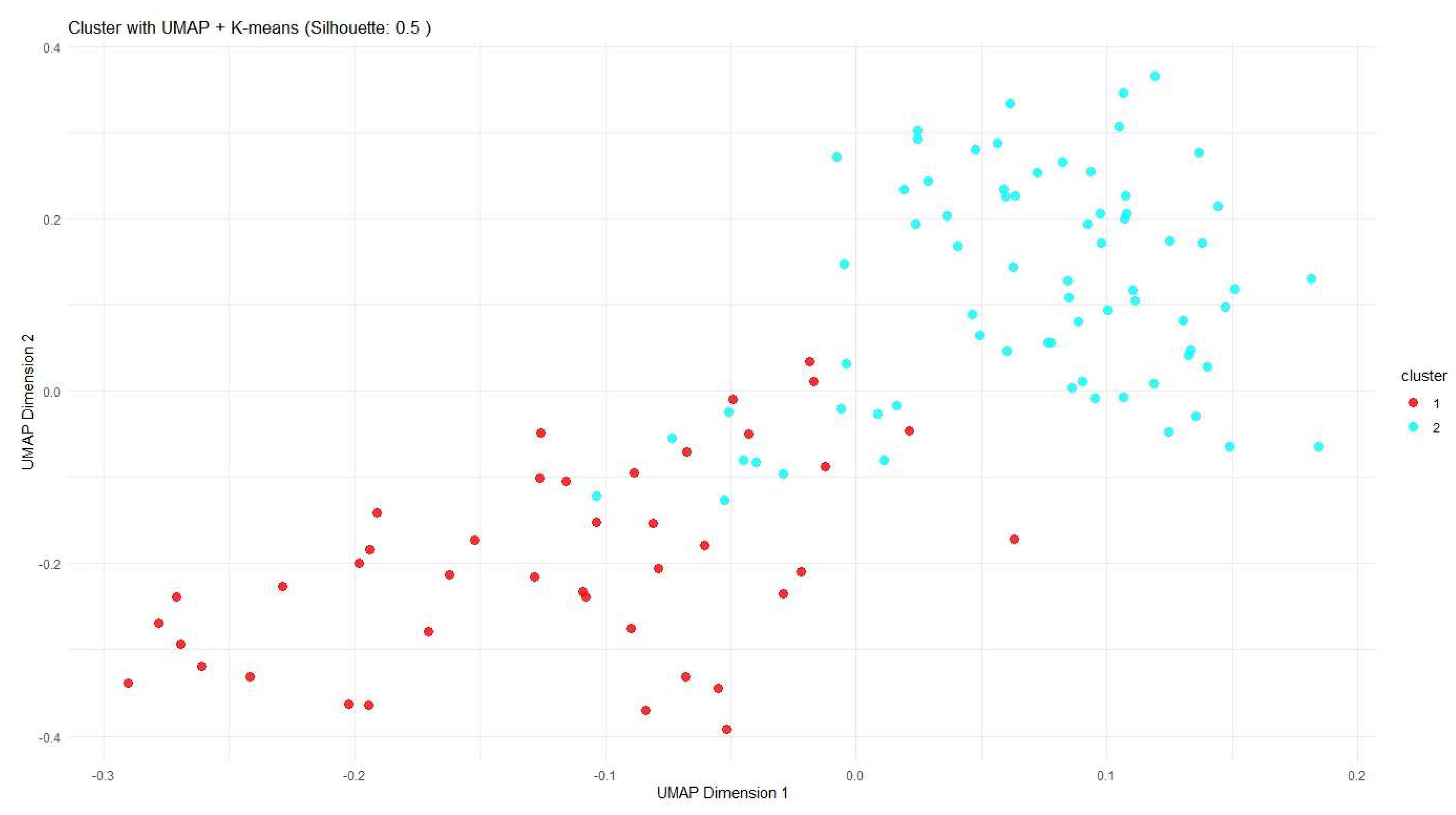

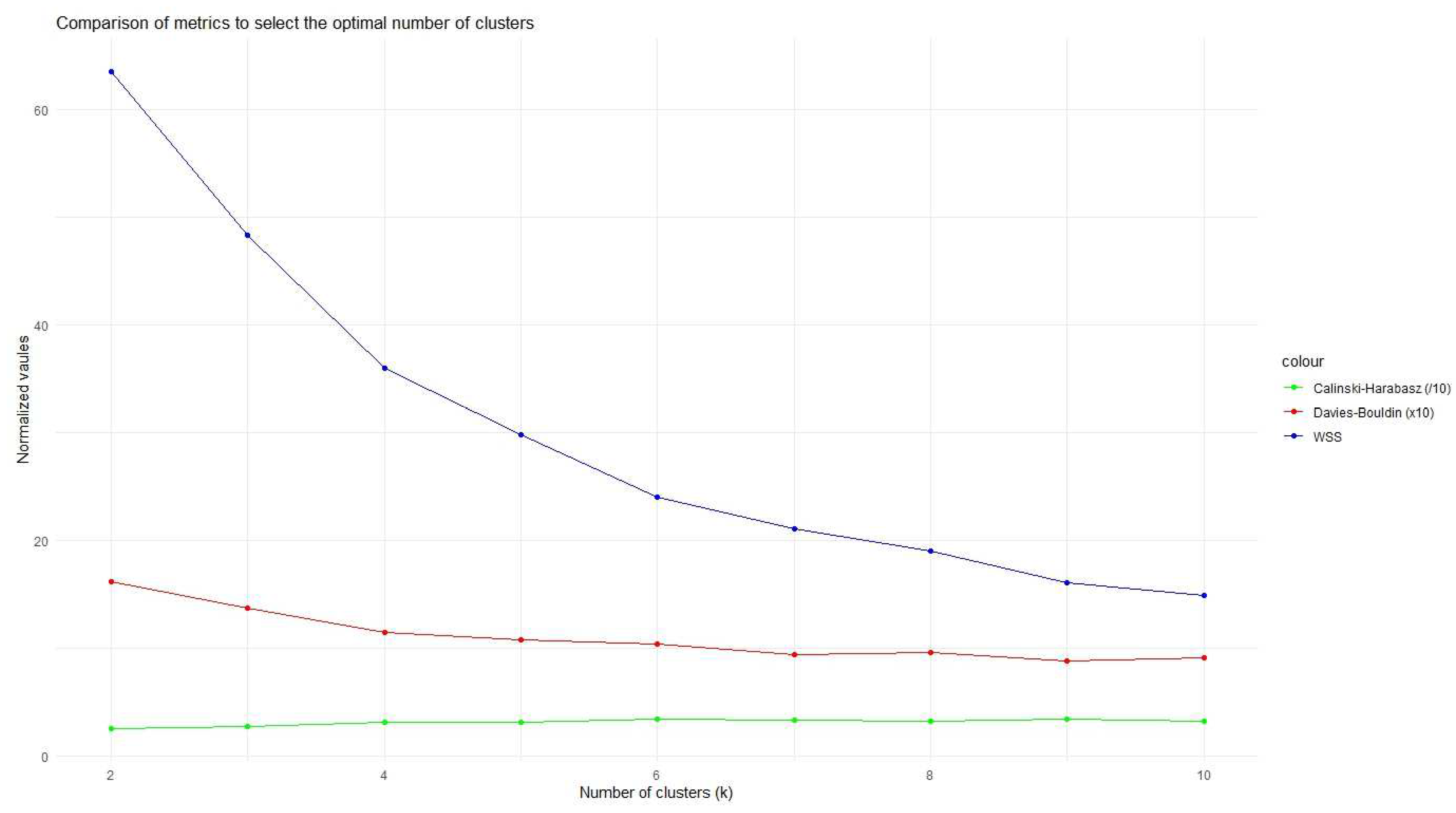

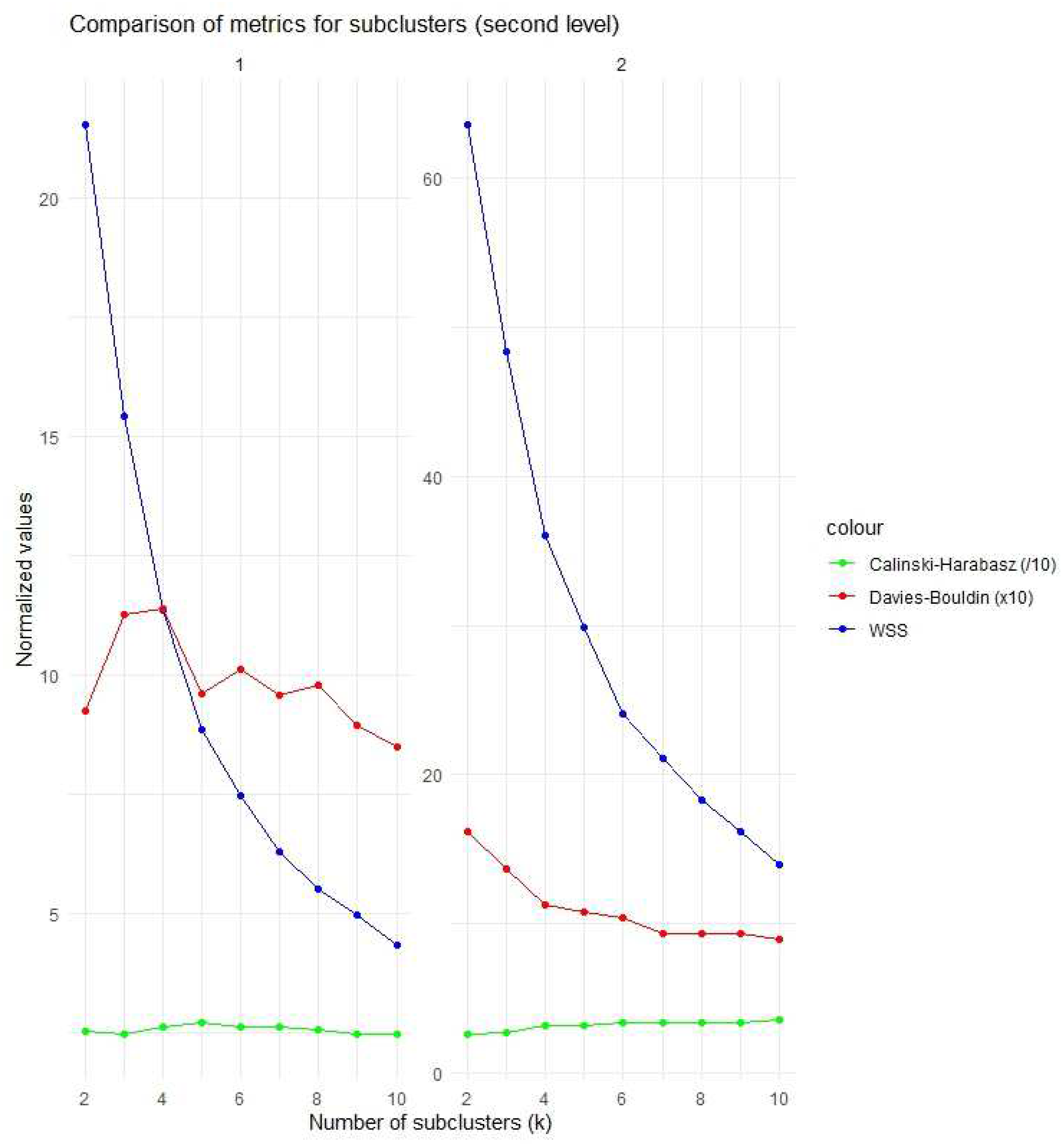

2.3.2. Identifying Focus Group Themes Using NLP Embeddings and UMAP Clustering

2.3.3. Software and Hardware

3. Results

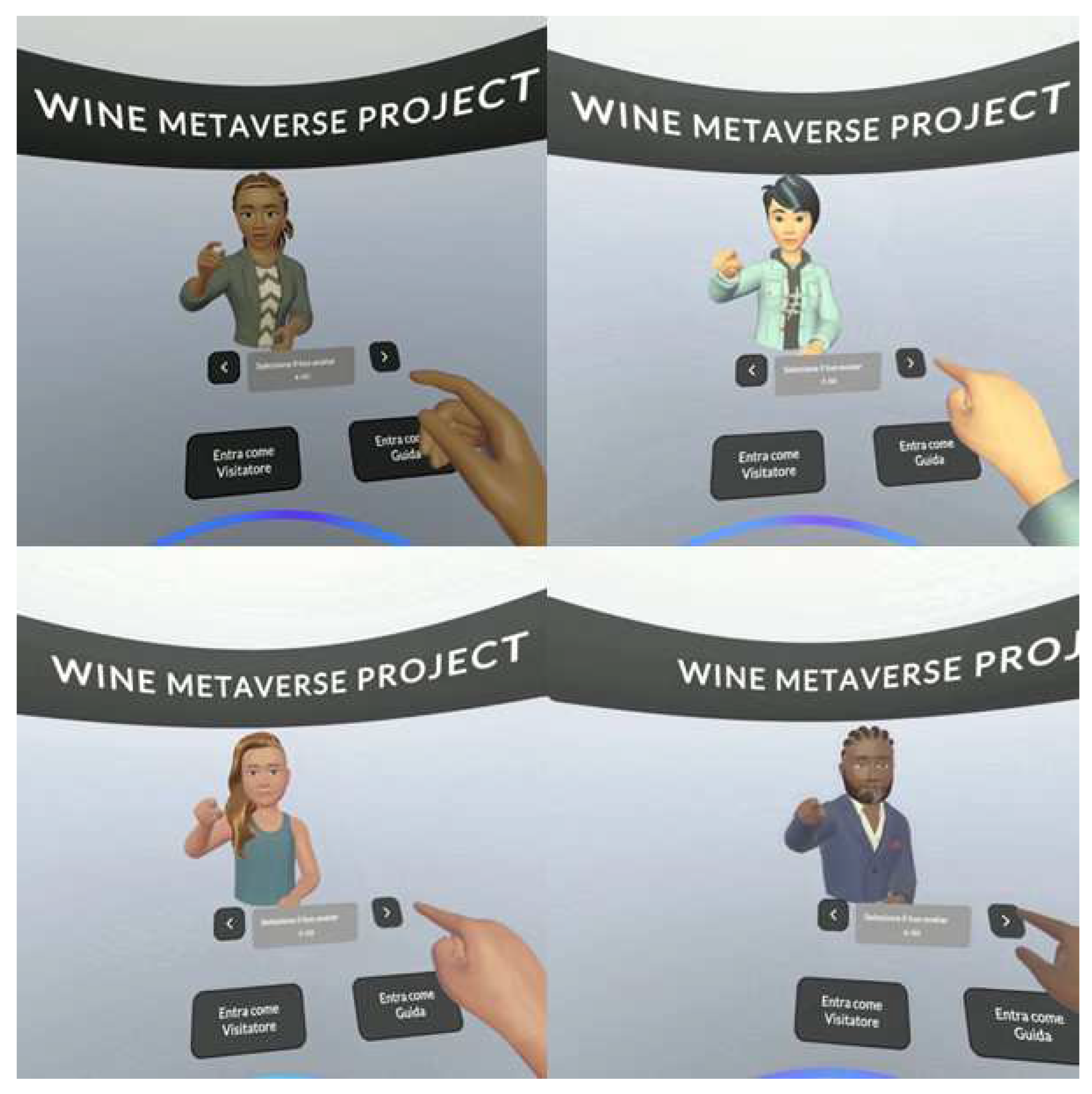

3.1. Scrum Results

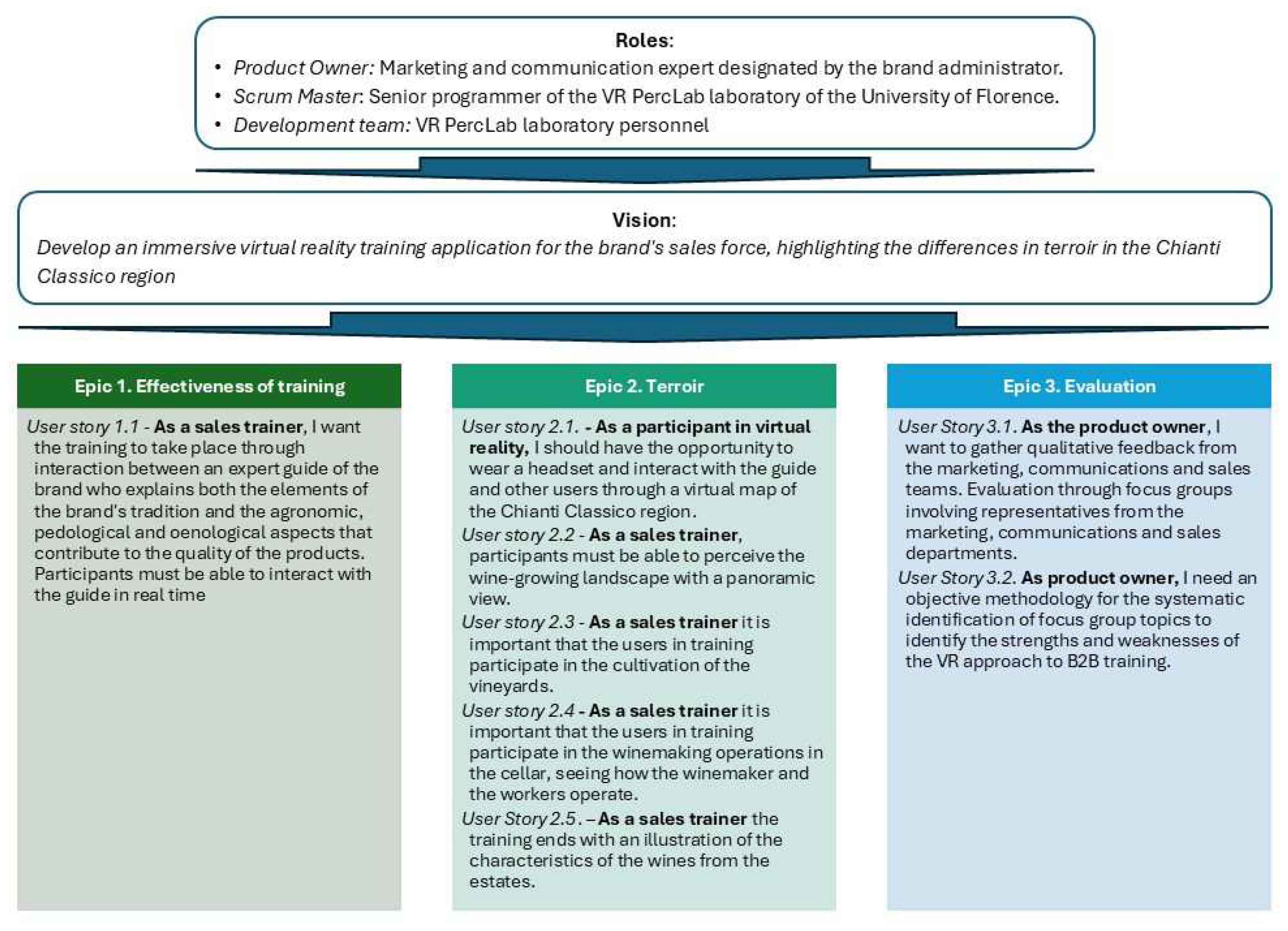

3.1.1. Roles

3.1.2. Vision and Product Backlog

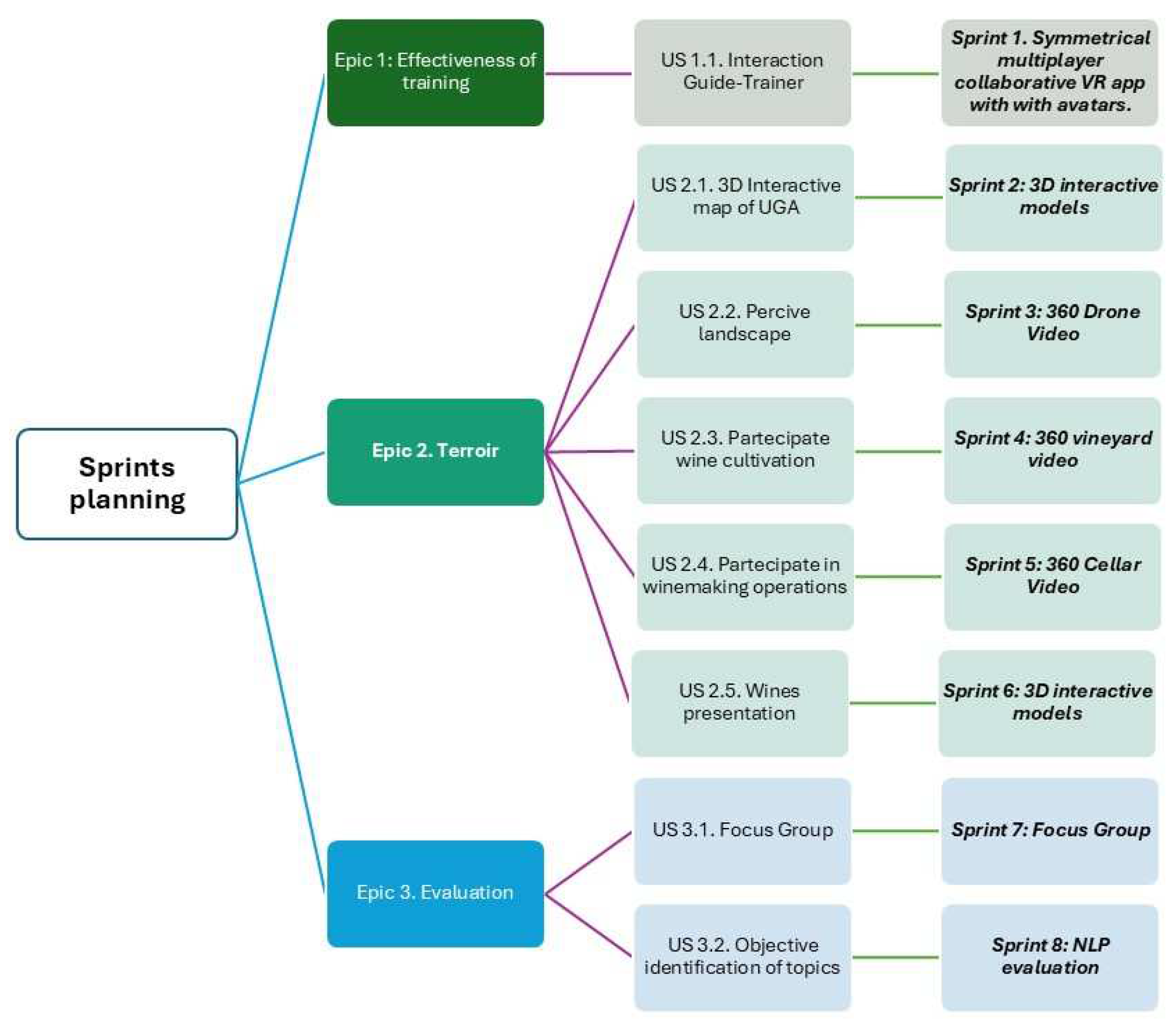

3.1.3. Sprint Planning

3.2. Focus Group Results

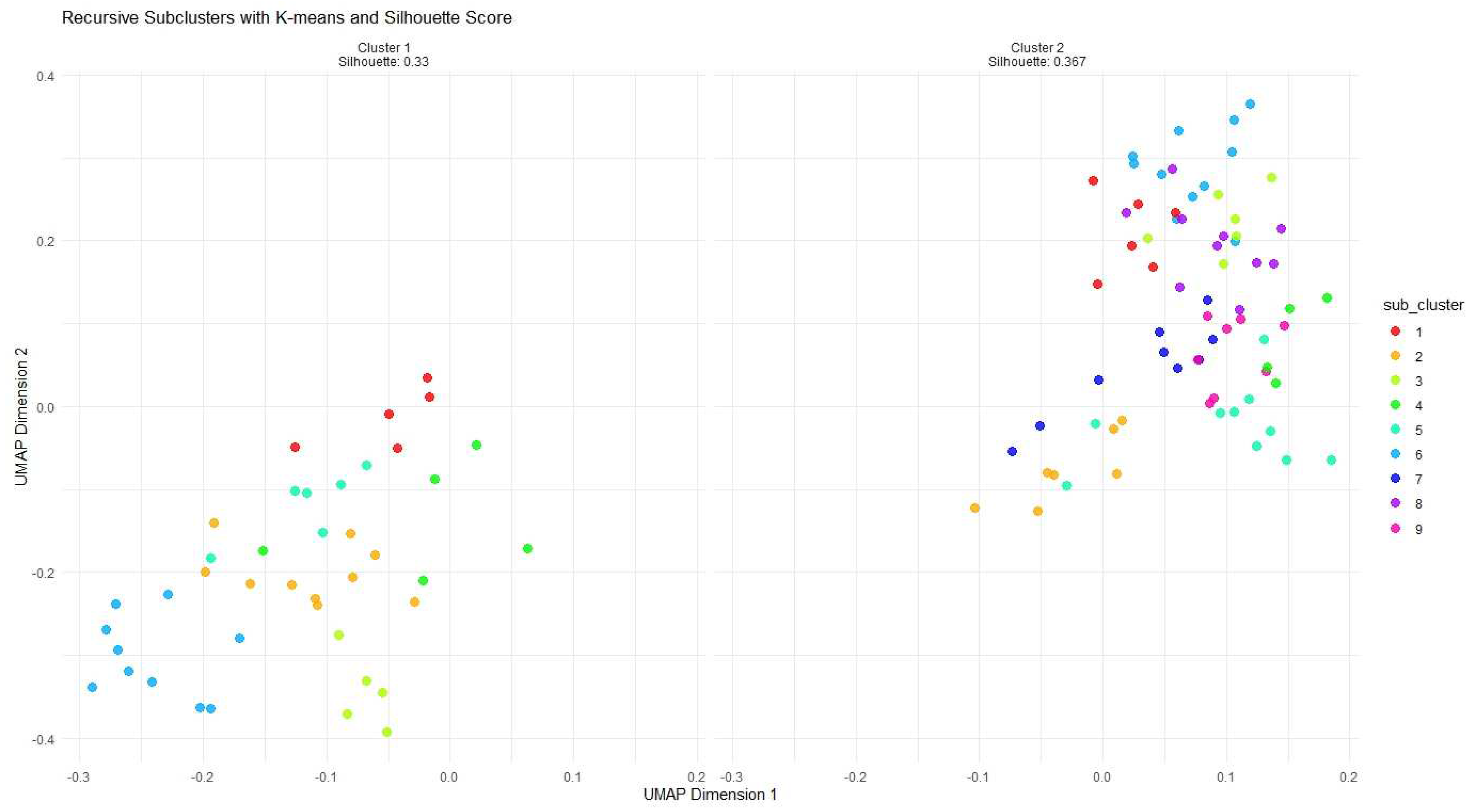

3.2.1. First-Level Recursive Clustering Results

3.2.3. Conclusions from Second-Level Clustering

4. Discussion

4.1. Research Questions Answers

4.2. Limits of the Work and Future Researches

4.3. Pratical Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| B2B | Business to Business |

| VR | Virtula Reality |

| LDA | Latent Dirichlet Allocation |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| UMAP | Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection |

References

- Beverland, M. Are Salespeople Relationship Oriented? (And Do They Need To Be?) A Study Based on the New Zealand Wine Industry. Int. J. Wine Mark. 1999, 11, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, D.E.; & Koles, B.; Koles, B. Virtual reality and its impact on B2B marketing: A value-in-use per-spective. Journal of Business Research 2019, 100, 590–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilinsky Jr, A.; Newton, S.; & Eyler, R.; Eyler, R. Are strategic orientations and managerial characteristics drivers of performance in the US wine industry? International Journal of Wine Business Research 2018, 30, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattiacci, A.; Bruni, A.; Magno, F.; Cassia, F. Sales capabilities in the wine industry: an analysis of the current scenario and emerging trends. Br. Food J. 2019, 121, 3380–3395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gultek, M.M.; Dodd, T.H.; Guydosh, R.M. Attitudes towards wine-service training and its influence on restaurant wine sales. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2006, 25, 432–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson-Rea, M.; Woodfield, P.; Brodie, R.J.; Lewis, N. Sustainability in strategy: main-taining a premium position for New Zealand wine. In Proceedings of the 6th AWBR international conference, Bordeaux; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Baceviciute, S.; Cordoba, A.L.; Wismer, P.; Jensen, T.V.; Klausen, M.; Makransky, G. Investigating the value of immersive virtual reality tools for organizational training: An applied international study in the biotech industry. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2021, 38, 470–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieland, D.A.; Ivens, B.S.; Kutschma, E.; Rauschnabel, P.A. Augmented and virtual reality in managing B2B customer experiences. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2024, 119, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klico, A. How using virtual reality can improve B2B marketing. BH Èkon. Forum 2022, 17, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberger, B.; Reinartz, W.; Ulaga, W. Navigating the future of B2B marketing: The trans-formative impact of the industrial metaverse. Journal of Business Research 2025, 188, 115057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freina, L.; Ott, M. A literature review on immersive virtual reality in education: State of the art and perspectives. In Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference eLearning and Software for Education (eLSE), Bucharest, Romania, 23–24 April 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, A. Utilizing Advanced Technology in Salesforce to Enhance CRM and Problem Solving. MANAGEMENT (IJCRM) 2024, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Torrico, D.D.; Han, Y.; Sharma, C.; Fuentes, S.; Viejo, C.G.; Dunshea, F.R. Effects of Context and Virtual Reality Environments on the Wine Tasting Experience, Acceptability, and Emotional Responses of Consumers. Foods 2020, 9, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, N.; Alén, E.; Losada, N.; Melo, M. Virtual reality in wine tourism: Immersive experiences for promoting travel destinations. J. Vacat. Mark. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moonen, N.; Heller, J.; Hilken, T.; Han, D.-I.D.; Mahr, D. Immersion or social presence? Investigating the effect of virtual reality immersive environments on sommelier learning experiences. J. Wine Res. 2024, 35, 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, D.S.; Seo, S.; Harrington, R.J.; Martin, D. When virtual others are with me: exploring the influence of social presence in virtual reality wine tourism experiences. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2024, 36, 548–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Leung, X.Y. Virtual wine tours and wine tasting: The influence of offline and online embodiment integration on wine purchase decisions. Tour. Manag. 2021, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwaber, K.; Beedle, M. Agile Software Development with Scrum. Prentice Hall, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Schwaber, K.; Sutherland, J. (2020). The Scrum Guide: The Definitive Guide to Scrum: The Rules of the Game. Scrum.org.

- Royce, W.W. Managing the Development of Large Software Systems. Proceedings of IEEE WESCON 1970, 26, 328–338. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, K.; Wohlin, C.; Baca, D. The waterfall model in large-scale development. In Prod-uct-Focused Software Process Improvement; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2009; pp. 386–400. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, K.S. (2012). Essential Scrum: A Practical Guide to the Most Popular Agile Process. Addi-son-Wesley.

- Moe, N.B.; Dingsøyr, T.; Dybå, T. A teamwork model for understanding an agile team: A case study of a Scrum project. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2010, 52, 480–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.; Ganjeizadeh, F.; Jayachandran, P.K.; Ozcan, P. A statistical analysis of the effects of Scrum and Kanban on software development projects. Robot. Comput. Manuf. 2017, 43, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.O.; Markkula, J.; Oivo, M. Kanban in software development: A systematic literature review. 2013 39th Euromicro Conference on Software Engineering and Advanced Applications 2013, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Highsmith, J. (2009). Agile Project Management: Creating Innovative Products. Addison-Wesley Pro-fessional.

- Pichler, R. (2010). Agile Product Management with Scrum: Creating Products that Customers Love. Addison-Wesley.

- Schwaber, K. Agile Project Management with Scrum. Microsoft Press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland, J.; & Schwaber, K. (2013). The Scrum Guide: The Definitive Guide to Scrum: The Rules of the Game. Scrum.org.

- Cohn, M. (2004). User Stories Applied: For Agile Software Development. Addison-Wesley.

- Brooke, J. SUS: A quick and dirty usability scale. In Usability evaluation in industry; Jordan, P.W., Thomas, B., Weerdmeester, B.A., McClelland, I.L., Eds.; Taylor & Francis, 1996; pp. 189–194. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, J.R. IBM computer usability satisfaction questionnaires: Psychometric evaluation and instructions for use. Int. J. Human–Computer Interact. 1995, 7, 57–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerald, J. The VR Book: Human-Centered Design for Virtual Reality. Morgan & Claypool Pub-lishers, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, D.L. Focus Groups as Qualitative Research, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger, R.A.; Casey, M.A. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research, 5th ed.; Sage Publications, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, D.W.; Shamdasani, P.N. Focus Groups: Theory and Practice, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Blei, D.M.; Ng, A.Y.; & Jordan, M.I. Latent Dirichlet Allocation. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2003, 3, 993–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Trans-formers for Language Understanding. 2019, arXiv:1810.04805. [Google Scholar]

- Silge, J.; Robinson, D. Text Mining with R: A Tidy Approach; O’Reilly Media, Inc., 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mikolov, T.; Chen, K.; Corrado, G.; & Dean, J. Efficient estimation of word representations in vector space. 2013, arXiv:1301.3781. [Google Scholar]

- Pennington, J.; Socher, R.; & Manning, C.D. GloVe: Global Vectors for Word Representation. Pro-ceedings of the 2014 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP); 2014; pp. 1532–1543. [Google Scholar]

- Joulin, A.; Grave, E.; Bojanowski, P.; Mikolov, T. Bag of tricks for efficient text classification. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1607.01759. [Google Scholar]

- Jolliffe, I.T.; Cadima, J. Principal component analysis: a review and recent developments. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 2016, 374, 20150202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McInnes, L.; Healy, J.; Melville, J. UMAP: Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection for Dimension Reduction. arXiv arXiv:1802.03426, 2018.

- Davies, D.L.; Bouldin, D.W. A cluster separation measure. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 1979, 1, 224–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calinski, T.; Harabasz, J. A dendrite method for cluster analysis. Communications in Statistics 1974, 3, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseeuw, P.J. Silhouettes: A graphical aid to the interpretation and validation of cluster analysis. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 1987, 20, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petukhova, A.; Matos-Carvalho, J.P.; Fachada, N. Text clustering with large language model embeddings. International Journal of Cognitive Computing in Engineering 2025, 6, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).