Introduction

The learning of the Kyrgyz language is not an easy task for foreigners or locals, and that is mainly because there are no useful and engaging digital resources. Very popular languages such as English, Russian are usually well-covered by most digital resources, but not the situation with Kyrgyz. This is particularly noticeable in urban areas such as Bishkek, where the general prevalence of Russian most frequently leads even native speakers of Kyrgyz to forget words (Sputnik Кыргызстан, 2023).

The latest innovations in mobile technology, Artificial Intelligence (AI), and Augmented Reality (AR) have presented new opportunities for creating innovative learning solutions. One can integrate these technologies and convert everyday interactions with the physical environment into language learning experiences. This project will create a mobile application using real-time AI-based object detection and AR to present everyday objects with Kyrgyz words overlaid onto them. By connecting words to real objects, the application hopes to achieve an interactive learning environment in accordance with natural language-acquisition processes.

Hypothesis: The intersection of real-time object detection and AR-word marking will improve vocabulary memorization and learner engagement better than current language-learning applications.

Literature Review

This Literature Review discusses a number of AR-based learning and AI-assisted education studies to suggest how these technologies can meet for more engaging and interactive language learning.

One of the earliest lines of work identifies the potential of marker-based AR for acquiring new words and alphabets, as exemplified by the ARabic-Kafa app (Wan Daud et al., 2021). The authors detail the technical procedure—animation using Blender, marker recognition using Vuforia—and establish that effective rendering of 3D objects depends on maintaining some angles (30°–90°) and short distances (10 cm). This early work attests to the potential of well-calibrated AR content to enhance student engagement.

There is also other research that has attempted to provide a more comprehensive approach to language learning through the integration of voicebots, AR, and big language models like ChatGPT (Topsakal, O., & Topsakal, E. (2022)). Their approach suggests offering an interactive platform for kids to learn a second language utilizing interactive dialogue on Google DialogFlow and ChatGPT as dynamic content providers. This convergence of voice interaction and AR reflects the trend to merge various AI elements into language-learning systems.

Son et al. (2023) offer a review of the application of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies to second and foreign language learning and teaching based on research studies conducted between 2010 and 2022. The seven most commonly known AI applications are Natural Language Processing (NLP), Data-Driven Learning (DDL), Automated Writing Evaluation (AWE), Computerized Dynamic Assessment (CDA), Intelligent Tutoring Systems (ITSs), Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR), and chatbots. These technologies are convenient to use in engaging learners, giving instant feedback, and enabling self-learning.

HTR can support learning the Kyrgyz language by using augmented reality to recognize and translate handwritten Kyrgyz text in real time (Zhumaev, I., et al., 2024), making language learning more interactive and immersive.

The majority of AR language applications in fact use object detection to recognize objects in real time. Detection of small objects is still a problem for one-stage object detectors. In an effort to remedy the problem, researchers suggest "MobileDenseNet" with lightweight "FCPNLite" neck (Hajizadeh et al., 2023). The solution is very precise—24.8 (COCO) and 76.8 (Pascal VOC)—improved over other competing state-of-the-art solutions without compromising on real-time operation on mobile devices.

Haristiani (2019) refers to the possible revolutionary edge of language acquisition and learning through AI, referencing individualization and an enhanced learning experience. AI intervenes by improving communicative competence through simulation in real-time and experiential training. Out of all the findings, 99% of students polled report AI to be useful and say it eases life and enhances learning processes. AI provides instant feedback on language acquisition with reported high efficiency in identifying errors and providing corrections. The same research documents fears about potential negative effects of AI implementation, including privacy issues (vulnerability to cyber-attacks) and the loss of the human element to language learning—calling for finding a balance between social contact and technology use.

Apart from AR itself, a broader discussion of AI application in language acquisition finds four overall themes for machine learning to support teaching and learning activities (Ali, 2020). Grading, feedback, and lesson planning specific to the individual learner emerge as the primary benefits, providing much context for AR + AI systems to evolve further and provide more individualized language learning.

Apps about detection or AR are not necessarily what language apps entail, however. A subtler taxonomy groups them by technology, pedagogy, user experience, and focus on learning (Ivić & Jakopec, 2016). Commercial apps predominantly are still built around independent drills and lack communicative or context-based components, supporting arguments in favor of more engaging or AI-boosted tools that model true language use.

Mobile device near-real-time recognition can also be achieved with effective CNN architectures such as MobileNetV2 combined with SSDLite (Sandler et al., 2018). This approach supports scalability to different model sizes without compromising high accuracy, which is very appealing for language learning AR applications requiring performance on resource-limited devices.

At last but not at least, an AI-based object detection translation (AI-based ODT) application shows the potential of such educational advantages to present the objects in word, image and pronunciation form (Liu et al., 2023). By demonstrating that participants with lower baseline competence showed significantly greater learning gains than those with higher competence, the study suggests that tailoring AR, and detection-based apps to accommodate users with varying degrees of skill will likely yield optimal learning outcomes.

Methods

This section describes the system architecture, implementation steps, and evaluation methods employed in developing the mobile application.

The project began with a detailed search for a proper object detection model. YOLOv8 models were tried first due to their popularity in speed and accuracy in object detection ("YOLOV8: State-of-the-Art Computer Vision Model," n.d.). Unfortunately, due to compatibility issues in our augmented reality (AR) platform, these models were finally found incompatible with our project. TensorFlow models were also investigated, but the initial tests were challenging in retraining and deploying these models in real-time on mobile devices.

It was found by working through the ARCore ML Kit sample ("Machine Learning with ARCore," n.d.). The sample illustrated how a camera stream from ARCore could be incorporated into a machine learning pipeline using ML Kit and the Google Cloud Vision API to identify real-world objects. It was composed in Kotlin and showed how the CPU image stream of ARCore could be supplied as input to a machine learning model to recognize objects and add virtual labels above them. Step-by-step analyses of image stream initialization, CPU image resolution management, and image coordinate transformation for hit-testing allowed us to marry machine learning and AR.

Based on experiences in the ARCore ML Kit sample, a mobile-friendly model named the "Google Mobile Object labeler" (n.d.) was selected. The model has a MobileNet V2 backbone with a 0.5 width multiplier, making it suitable for on-device image classification. The model was initially developed for dominant object classification in an image and met the real-time performance needs necessary for our AR app.

- 2.

User Interface

Interface design started with a study of papers on the design of user-friendly interfaces. This literature review provided general information on user-centered design principles, focusing on usability and intuitive interaction (Ismailova & Ermakov, 2024). These insights guided the initial design strategy.

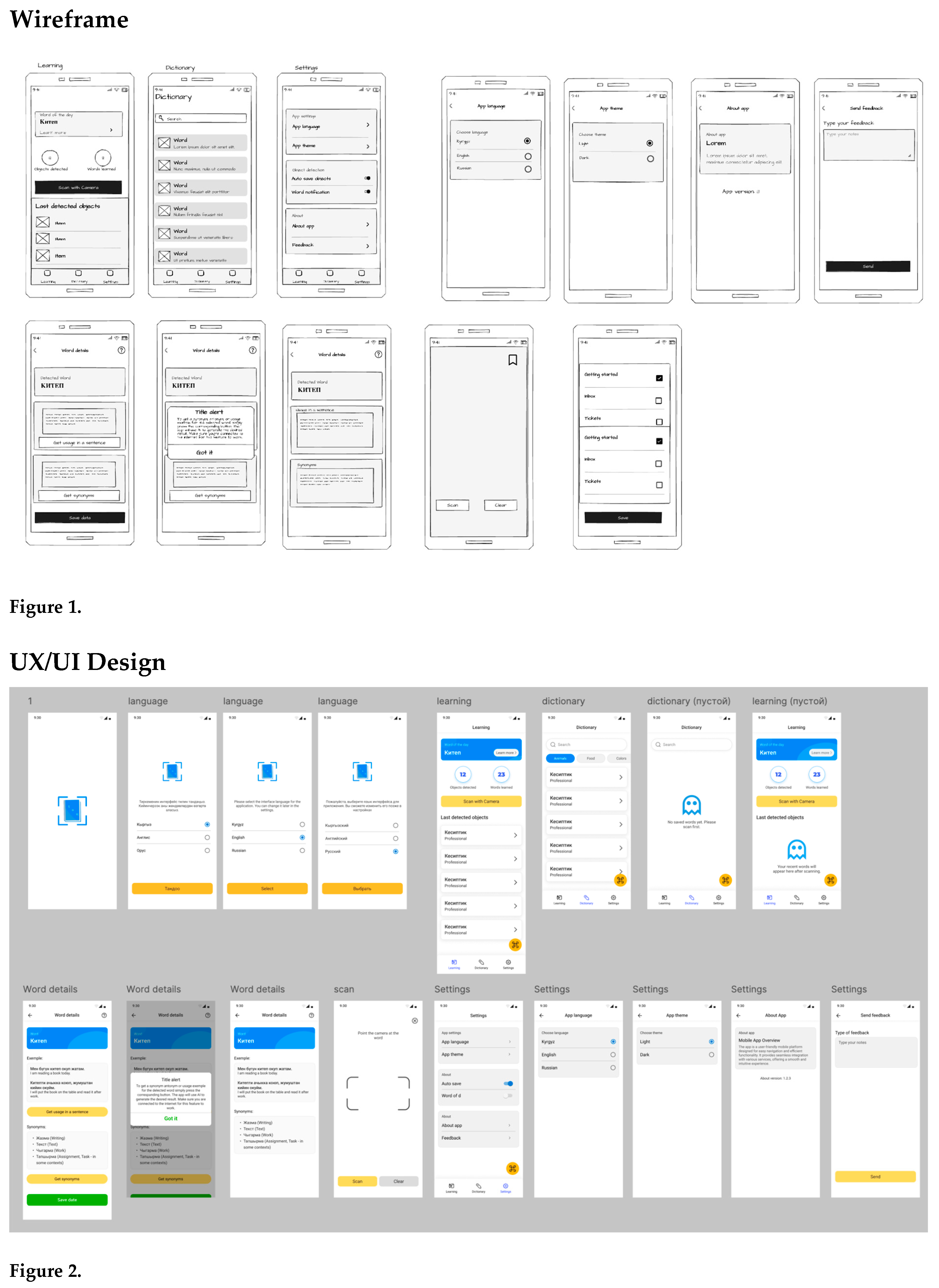

Early wireframes were then developed to serve as a skeletal framework of the app's structure and user flow (Figure 1). These wireframes acted as a visual map, enabling the identification of potential usability issues at the early stages of design.

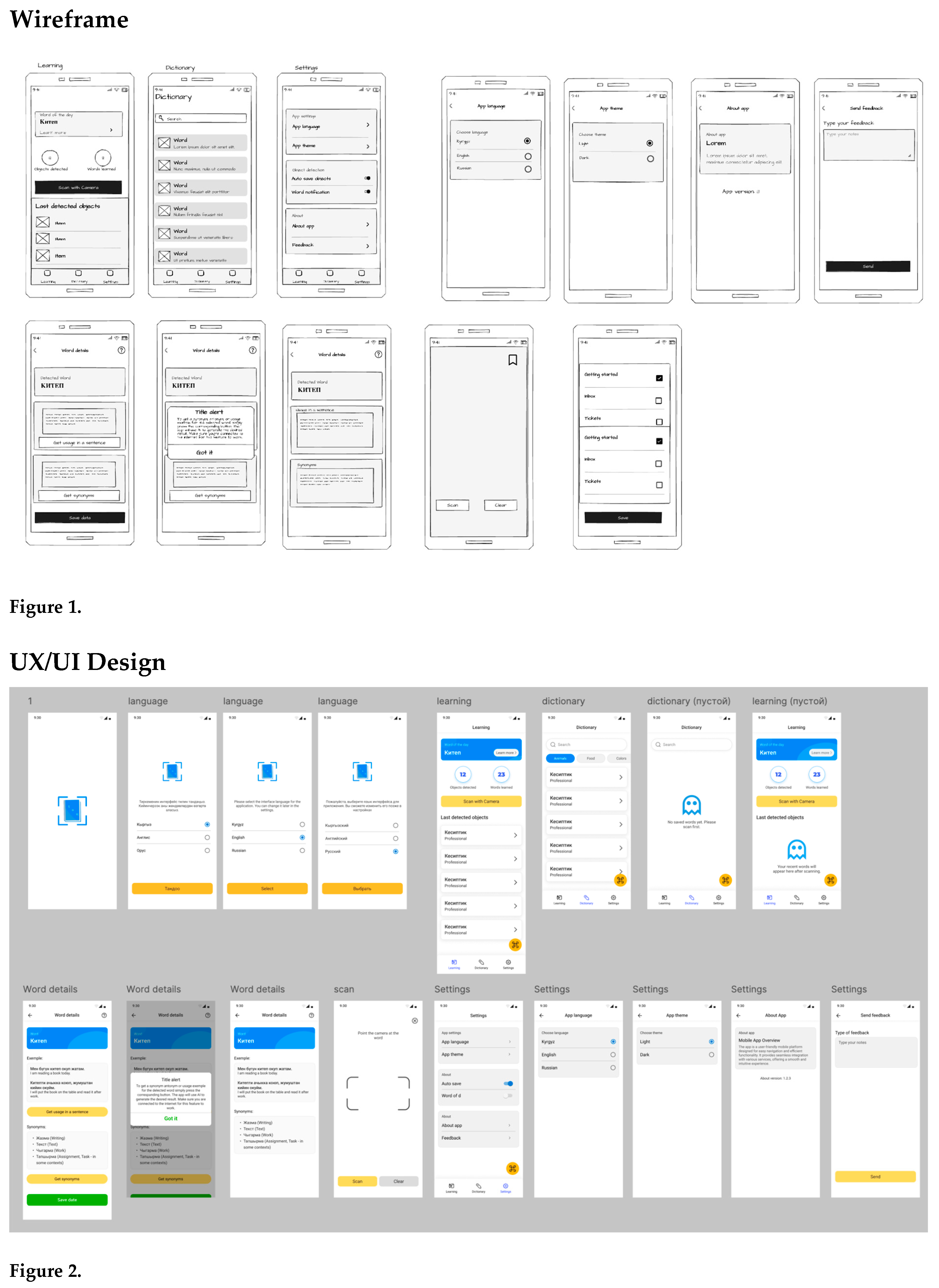

Following the establishment of the wireframe, attention shifted to the visual aspects of the interface. A color scheme was selected with an emphasis on maximizing readability and harmonizing with the cultural heritage of the target audience.Screen designs were minimalist and intuitive so that they would be easy to use.

Finally, the design was converted into an interactive prototype using design tools like Figma (Figure 2). Subsequently, the prototype was subjected to usability testing with a few users to find out if it is good to look at and usable. The data from those tests were then used to iteratively refine it until it resulted in a fully interactive and very usable interface.

Results

By using real-time object tagging in the everyday environment, the mobile application facilitates memorization of vocabulary and natural learning over traditional methods of study. Following user-centered design principles, the interface is made intuitive and salient to users. Formal usability testing has not yet been conducted, but best practices of current research indicate that robust visual cues and augmented reality (AR) functionality can greatly enhance user engagement and enhance overall language acquisition.

The interface screens below are enforced and real-time object-detection functions, and they show how labeled objects appear in the app (Figure 3).

Conclusions

The project showcases how technology can enhance vocabulary learning through the development of a mobile application based on augmented reality (AR) for real-time labeling of objects. The system constructs an environment for more engaged and interactive learning, overlaying labels on everyday objects within the user's immediate environment, as compared with more traditional forms. Usability testing can help indicate, judging from the preliminary design of the application itself, that by being user-centered, it could motivate learning, increase retention, and favor overall language proficiency. This will further demonstrate the way AR can seamlessly connect physical and virtual clues into a natural bridge for learners to acquire vocabulary and polish their language skills.

References

- Ali, Z. (2020, February). Artificial intelligence (AI): A review of its uses in language teaching and learning. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering (Vol. 769, No. 1, p. 012043). IOP Publishing.

- Google. (n.d.). Google | mobile_object_labeler_v1 | Kaggle. https://www.kaggle.com/models/google/mobile-object-labeler-v1.

- Hajizadeh, M., Sabokrou, M., & Rahmani, A. (2023). MobileDenseNet: A new approach to object detection on mobile devices. Expert Systems with Applications, 215, 119348.

- Haristiani, N. (2019, November). Artificial Intelligence (AI) chatbot as language learning medium: An inquiry. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series (Vol. 1387, No. 1, p. 012020). IOP Publishing.

- Heil, C. R., Wu, J. S., Lee, J. J., & Schmidt, T. (2016). A review of mobile language learning applications: Trends, challenges, and opportunities. The EuroCALL Review, 24(2), 32–50.

- Ivić, V., & Jakopec, T. (2016). Using mobile application in foreign language learning: A case study. Libellarium, 9(2).

- Liu, P. L., & Chen, C. J. (2023). Using an AI-based object detection translation application for English vocabulary learning. Educational Technology & Society, 26(3), 5–20.

- Machine learning with ARCore. (n.d.). Google for Developers. https://developers.google.com/ar/develop/machine-learning.

- Sandler, M., Howard, A., Zhu, M., Zhmoginov, A., & Chen, L. C. (2018). Mobilenetv2: Inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (pp. 4510–4520).

- Son, J. B., Ružić, N. K., & Philpott, A. (2023). Artificial intelligence technologies and applications for language learning and teaching. Journal of China Computer-Assisted Language Learning. Advance online publication.

- Topsakal, O., & Topsakal, E. (2022). Framework for a foreign language teaching software for children utilizing AR, voicebots and ChatGPT (large language models). The Journal of Cognitive Systems, 7(2), 33–38.

- Урoвень знания кыргызскoгo и русскoгo языка в региoнах КР — результаты переписи. (2023, September 29). Sputnik Кыргызстан. https://ru.sputnik.kg/20230929/uroven-znaniya-kyrgyzskogo-russkogo-yazykov-regionah-kr-1079010702.html.

- Wan Daud, W. A. A., Ghani, M. T. A., Rahman, A. A., Yusof, M. A. B. M., & Amiruddin, A. Z. (2021). ARabic-Kafa: Design and development of educational material for arabic vocabulary with augmented reality technology. Journal of Language and Linguistic Studies, 17(4), 1760–1772.

- YOLOV8: State-of-the-Art Computer Vision Model. (n.d.). https://yolov8.com/.

- Zhumaev, I., Shambetova, B., & Isaev, R. (2024, June). Handwritten Text Recognition of Letters in Kyrgyz Language. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer Systems and Technologies 2024 (pp. 57-62).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).