Introduction

The human body’s musculoskeletal and visual systems share biomechanical, vascular, and neural pathways historically underexplored in clinical practice. Studies have already demonstrated significant correlations between visual disorders, particularly in the musculature of the neck and shoulder regions [1,2]. For instance, individuals with age-related macular degeneration (ARMD) tend to experience more musculoskeletal discomfort, likely due to compensatory postural adjustments and increased strain during visual tasks [1]. One study found strong correlations between visual complaints and musculoskeletal discomfort seen in both ARMD and age-matched control patients (Spearman’s coefficient, =0.60 and 0.59, respectively, P<0.005) [1].

Sánchez-González et al., 2019, conducted a meta-analysis of 21 studies to support the relationship between visual systems and musculoskeletal complaints, showing consistent visual system disorders in accommodation and non-strabismic binocular dysfunctions and chronic neck pain and shoulder discomfort [2]. The visual disturbances are thought to alter head posture and visual motor behavior, exacerbating present neck issues and strain. However, while the analysis evaluated bias risk using the modified Cochrane Collaboration Tool and Study Quality Assessment Tool, and the GRADEpro Guideline Development tool to evaluate the studies, they found that many lacked standardized assessment techniques. Thus, the statistical analytic power was significantly affected in unifying clinical protocols [2].

Recent advancements in AI, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), uncover latent connections between ocular biomarkers and systemic musculoskeletal pathologies. For instance, retinal microvascular changes detected via optical coherence tomography (OCT) may signal early-stage osteoporosis [3], while spinal misalignment correlates with optic nerve compression and glaucoma progression [2].

These insights revolutionize diagnostic workflows, enabling clinicians to predict musculoskeletal degeneration through noninvasive ocular imaging. The convergence of AI and high-resolution imaging modalities—such as OCT, fundus photography, and MRI— drives the development of predictive models that integrate biomechanical, genetic, and proteomic data. These models enhance diagnostic accuracy and guide personalized surgical planning and postoperative rehabilitation. This review evaluates the transformative potential of AI in musculoskeletal and ocular medicine, focusing on validated applications in diagnostics, surgical robotics, and long-term prognostication [1,2,3].

Materials and Methods

This narrative review was conducted through a comprehensive literature survey focusing on the intersection of artificial intelligence, musculoskeletal imaging, and ocular diagnostics. Peer-reviewed articles, clinical trial data, and emerging research published between 2000 and 2025 were retrieved from databases including PubMed, IEEE Xplore, Scopus, and ClinicalTrials.gov. Keywords used in the search included combinations of “machine learning,” “deep learning,” “ocular biomarkers,” “musculoskeletal disorders,” “convolutional neural networks,” “OCT,” “MRI,” “digital twins,” and “surgical robotics.” Preference was given to studies demonstrating clinical validation, real-world application, or translational potential of AI-driven platforms. Studies involving AI methodologies applied independently or synergistically across orthopedic and ophthalmologic contexts were included. Additionally, regulatory white papers, systematic reviews, and consensus guidelines were reviewed to address ethical considerations, model interpretability, and clinical implementation. Data extraction was performed manually, and duplicate or non-English publications were excluded. The review adheres to the SANRA (Scale for the Assessment of Narrative Review Articles) guidelines to ensure methodological rigor and transparency.

AI Integration Methodology in Musculoskeletal and Ocular Diagnostics as Independent Fields

The methodological framework for integrating AI into musculoskeletal and ocular diagnostics hinges on data acquisition, algorithmic training, and clinical validation.

Data Acquisition

AI-driven diagnostic workflows integrate high-resolution imaging modalities, including spectral-domain OCT (SD-OCT), 3-tesla MRI, and musculoskeletal ultrasound (MSK-US) (

Figure 1). These technologies generate complex datasets that can be used to train CNNs to recognize patterns indicative of systemic pathologies [4,5,6,7]. Bellemo et al. trained AI models on SD-OCT images, achieving high accuracy in detecting subtle deviations in choroidal thickness with submicron precision, which has been associated with musculoskeletal issues such as lumbar disc degeneration [7,8]. Similarly, Clarius MSK AI used real-time tendon segmentation via U-Net architectures, achieving a Dice coefficient of 0.89 in real-time tendon segmentation for structures like the patellar tendon, Achilles tendon, and plantar fascia. This capability reduces inter-observer variability in synovitis grading and soft tissue abnormalities [9,10,11].

However, despite the widespread use of SD-OCT in clinical ophthalmology, its limited penetration depth hampers detailed visualization of the choroid, a vascular layer critical for diagnosing chorioretinal diseases. Swept-source OCT (SS-OCT) overcomes this limitation with enhanced depth imaging but remains costly and less accessible. Bellemo et al. also developed a generative deep-learning model that synthetically enhances SD-OCT images to mimic the choroidal clarity of SS-OCT scans. This model was trained on 150,784 paired SD-OCT and SS-OCT images from 735 eyes diagnosed with glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy, or deemed healthy. The AI learned to replicate deep anatomical features, thereby enabling improved visualization of the choroid using standard SD-OCT devices [7,8,10,14].

Performance evaluation using an external test dataset of 37,376 images revealed clinicians could not distinguish real SS-OCT images from AI-enhanced SD-OCT scans, achieving only 47.5% accuracy—suggesting high realism in the synthetic outputs. Quantitative comparisons further validated the approach: choroidal thickness, area, volume, and vascularity index measurements derived from the AI-enhanced SD-OCT scans showed strong concordance with those from SS-OCT, with Pearson correlation coefficients up to 0.97 and intra-class correlation values as high as 0.99. These findings suggest that deep learning can democratize access to high-quality choroidal imaging, particularly in low-resource settings where SS-OCT is not readily available [7,8,10]. These advancements collectively demonstrate how AI can enhance the quality and accessibility of diagnostic imaging across ophthalmology and orthopedics. By augmenting existing imaging modalities and improving measurement reliability, AI systems have the potential to significantly impact patient outcomes through earlier detection, greater consistency, and broader access to advanced diagnostics [14].

Algorithm Training

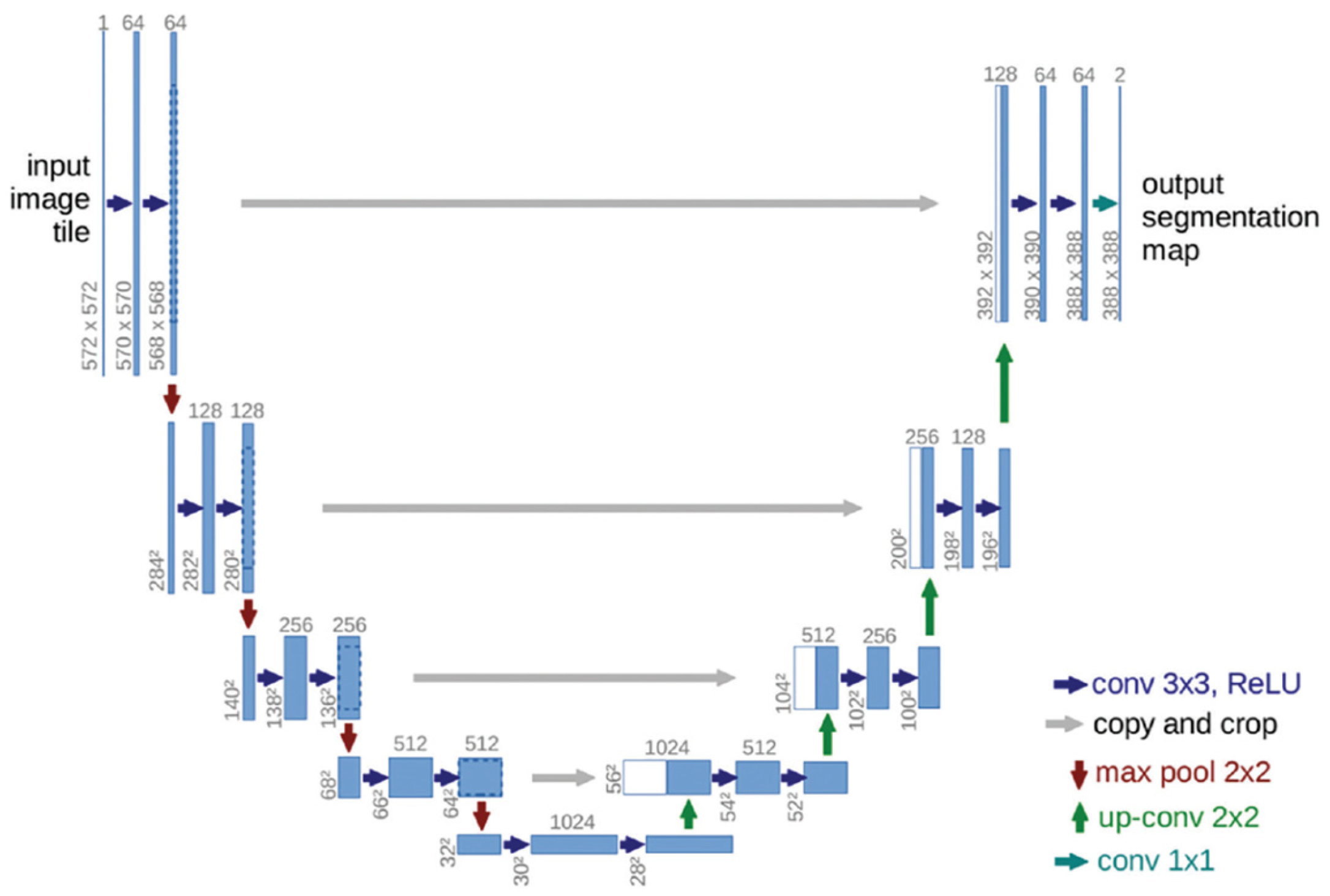

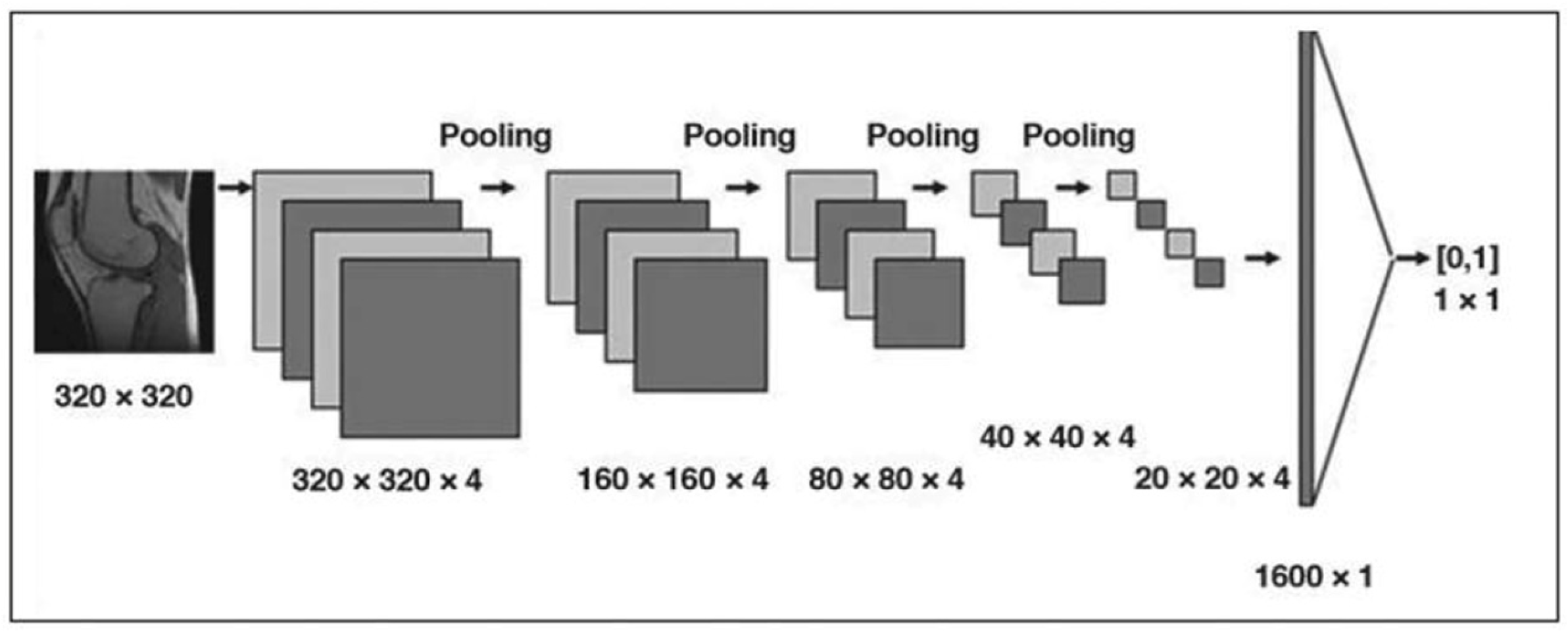

AI systems in ophthalmic and musculoskeletal imaging increasingly rely on more complicated machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) algorithms for tasks such as classification, regression, clustering, and feature extraction [3,12]. Conventional ML methods, including logistic regression, decision trees, and nearest-neighbor searches, operate under supervised or unsupervised paradigms to learn mappings from input data, as seen in fracture classification from X-rays or unsupervised pattern discovery [3,13,14]. More advanced DL architectures, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), are becoming more prevalent since they can extract spatial hierarchies and achieve translational invariance (

Figure 2) [3,13,14]. A breakthrough in medical image segmentation came with architectures like 2D U-Net, which have allowed for accurate segmentation even with limited training data (

Figure 3) [13,14].

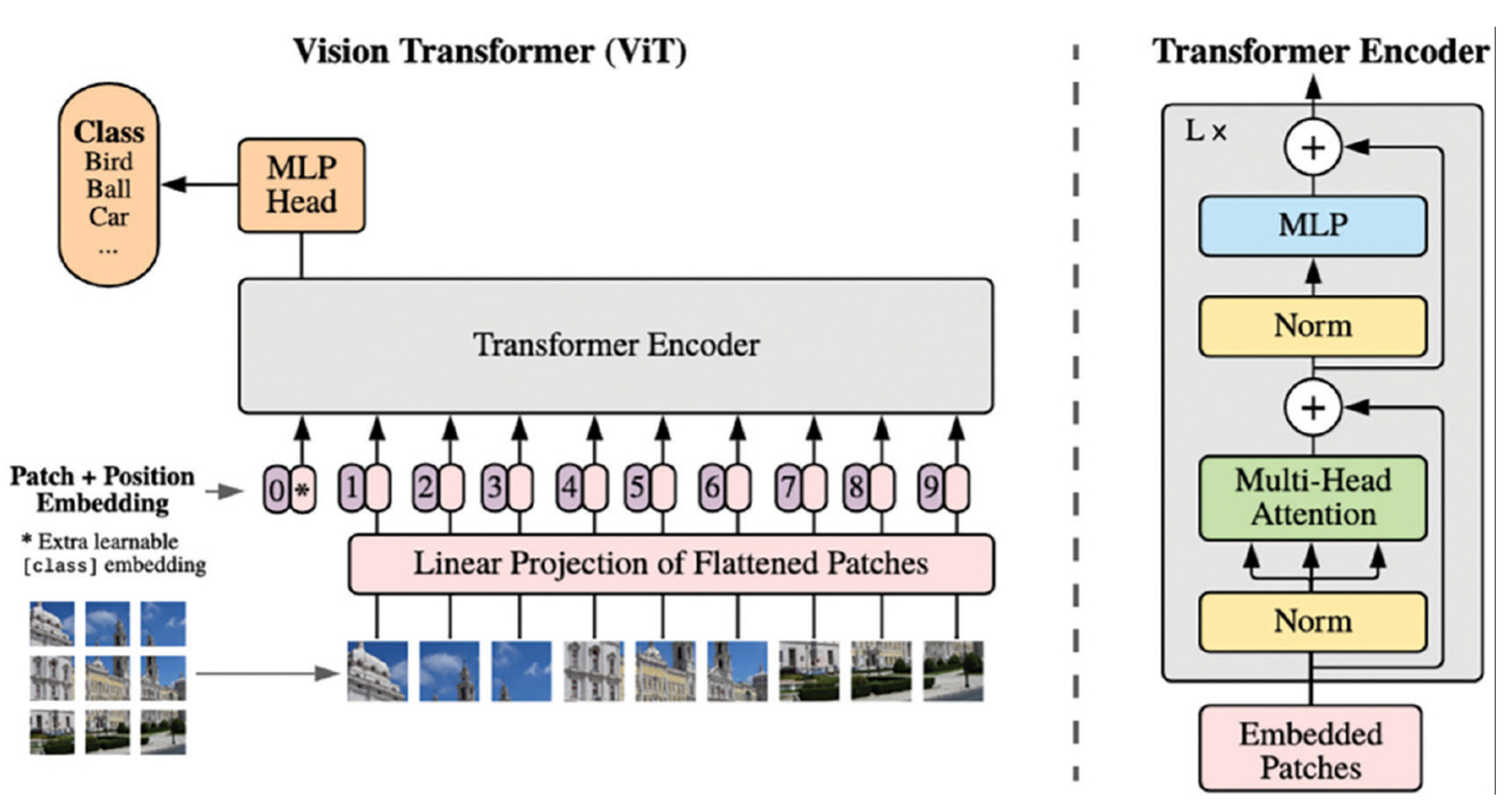

Despite their effectiveness, CNNs often require large datasets, are prone to overfitting samples, and present challenges in interpretability [13,14]. To address these limitations, newer approaches such as generative adversarial networks (GANs) have been applied to medical image synthesis and translation, employing adversarial training between the generator and discriminator networks. However, stability and mode collapse issues persist. Meanwhile, vision transformers (ViTs) and other transformer-based models are gaining traction by leveraging global context through token-based processing of multimodal inputs, including image and text (

Figure 4) [13,14].

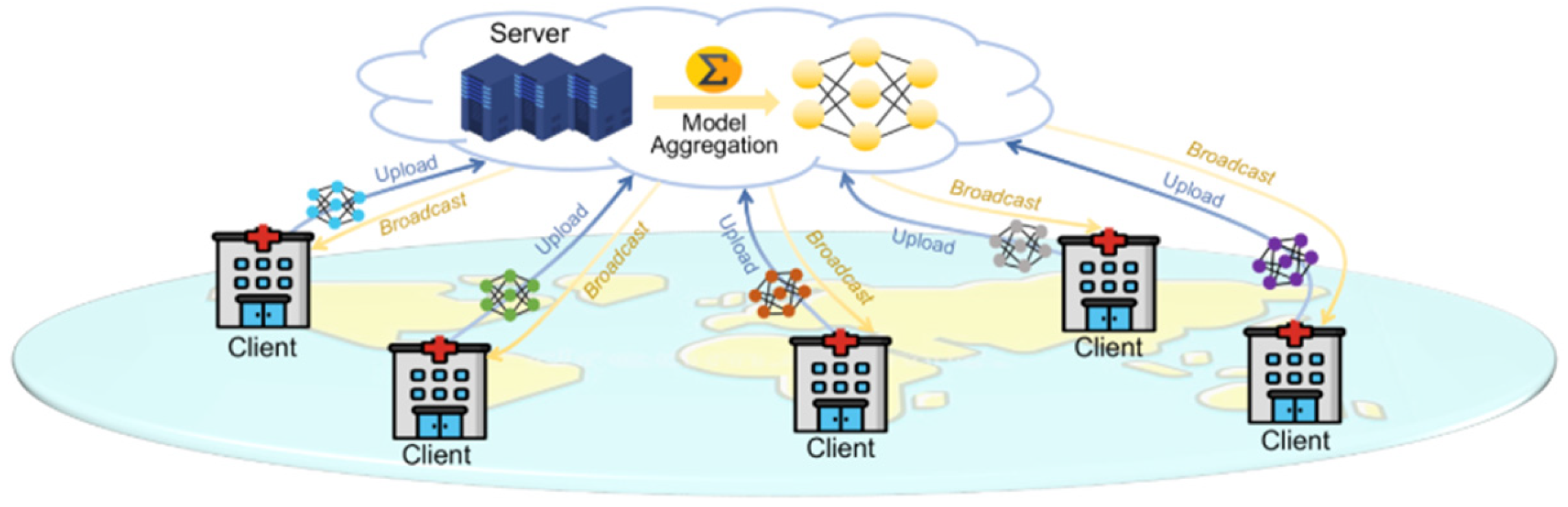

To overcome the challenges of data scarcity and privacy concerns, federated learning frameworks have emerged as key enablers, allowing decentralized training across heterogeneous datasets while preserving patient confidentiality (

Figure 5) [13,14,17,18]. Quantum machine learning (QML) has evolved with these trends, accelerating model training using quantum processors. One QML prototype reduced training time for musculoskeletal radiomics models by 72% with 54-qubit processors, enabling rapid analysis of T2-weighted MRI scans to predict lumbar disc herniation recurrence [14,19].

Clinical Validation

Validation studies underscore the clinical potential of these AI tools. In musculoskeletal health, a meta-analysis by Droppelmann et al. reported that 13 AI models achieved 92.6% sensitivity and 90.8% specificity for upper extremity pathologies, outperforming radiologist assessments in multicenter trials [3,14,19]. Similarly, AI models have matched expert-level accuracy in fracture detection [3,13,14,20]. In ocular diagnostics, AI models successfully identify diabetic macular edema from fundus photography and OCT [21]. Other innovations include DL–based ultrasound computer-aided detection and diagnosis (CADe/CADx) systems, which benefit from large, digitized datasets to deliver robust, generalizable outputs [21]. Across imaging modalities—CT, MRI, US, and nuclear medicine—AI-powered radiomics enhances diagnostic accuracy, risk stratification, and treatment planning, signaling a transformative shift in clinical imaging workflows [3,13,14,20].

AI-Driven Diagnostic Synergies Between Ocular and Musculoskeletal Systems

Convolutional Neural Networks in Multimodal Imaging

CNNs have become pivotal tools for analyzing spatially structured imaging data across ocular and musculoskeletal modalities (

Figure 6). For example, a CNN trained on 8,260 knee radiographs achieved 92.3% accuracy in classifying osteoarthritis [22,23,24]. These networks leverage hierarchical feature extraction to identify subtle patterns, such as microaneurysms in diabetic retinopathy. These are hypothesized to correlate with accelerated cartilage degradation in osteoarthritis due to shared collagen dysregulation pathways [3,14,25]. Similar AI approaches have been applied to inflammatory conditions, where optical coherence tomography angiography (OCT-A) shows promise in identifying vascular changes associated with musculoskeletal decline [24,25,26].

Generative adversarial networks (GANs) further enhance diagnostic precision by synthesizing cross-modality images. Spine-GAN segments vertebrae, intervertebral discs, and neural foramina with 94% spatial consistency, validated against ground truth masks [3,13,27]. Similarly, AI-driven OCT analysis quantifies choroidal thickness with submicron resolution, revealing associations between choroidal thinning and lumbar disc degeneration mediated by impaired glymphatic drainage [6]. Advanced techniques like StarGAN enable synthetic MRI reconstruction from single scans, improving quantitative assessments of musculoskeletal disorders [26,28]. Transfer learning techniques, such as fine-tuning pre-trained ResNet-50 models on retinal fundus images, improve fracture detection sensitivity in upper extremity radiographs [19].

Non-Invasive Ocular Biomarkers for Musculoskeletal Pathologies

Ocular imaging provides a window into systemic health, with AI identifying subtle patterns tied to musculoskeletal conditions. RNFL thinning, quantified via SD-OCT, predicts cervical spine instability post-whiplash with 91.3% sensitivity and 87.6% specificity [24,26]. Similarly, choroidal thickness variance, measured using enhanced-depth imaging OCT, correlates with lumbar disc degeneration (AUC = 0.82), likely due to shared disruptions in cerebrospinal fluid dynamics [22,26]. In rheumatology, retinal vein tortuosity has is lower in ankylosing spondylitis patients than in controls (=0.1 vs =0.5) [14,29]. At the same time, Türkcü et al. used OCTA to reveal reduced vessel density in both the superficial and deep capillary plexuses compared to controls, illustrating the presence of microvascular alterations in psoriasis patients, demonstrating microvascular alterations in inflammatory musculoskeletal diseases [30]. All these studies demonstrate the distinct retinal vessel tortuosity and density patterns across inflammatory musculoskeletal pathologies.

Further supporting the link between ocular imaging and systemic health, Jiang et al. found a significant correlation between reduced bone mineral density (BMD) and thinner choroidal thickness, as assessed by swept-source optical coherence tomography (SS-OCT). The study, involving 355 patients with low BMD and 355 healthy controls, found that the average choroidal thickness was notably lower in the low BMD group compared to the controls (215.50 μm vs. 229.73 μm, p = 0.003). These findings suggest a positive association between choroidal thickness and BMD, possibly due to vitamin D deficiency and vascular stiffening [31,32]. In Parkinson’s Disease (PD), Eraslan et al. reported reduced choroidal thickness, particularly in patients with more severe symptoms [33], while Brown et al. found that thinner choroidal thickness was linked to greater motor severity, higher dopaminergic therapy usage, and increased MRI pathology in the substantia nigra compacta (SNc) [34].

In another rheumatological application, fluorescence optical imaging (FOI) paired with CNNs identifies synovitis patterns in rheumatoid arthritis with 95% agreement with radiologists. In comparison, concurrent OCT scans reveal choroidal thickening in 68% of patients, implicating shared inflammatory pathways [25,32]. Additionally, a study published in Rheumatology (2022) introduced the FOIE-GRAS (Fluorescence Optical Imaging Enhancement-Generated RA Score) system, which demonstrated high reliability in detecting synovitis in RA patients, with intra-class correlation coefficients ranging from 0.76 to 0.98 [35]. A systematic review by Fekrazad et al. (2024) further confirmed that RA patients exhibited significantly lower choroidal thickness at certain sites compared to healthy controls, suggesting that choroidal thickness measurements may be related to visual acuity and the potential for rheumatic-ophthalmic problems [36].

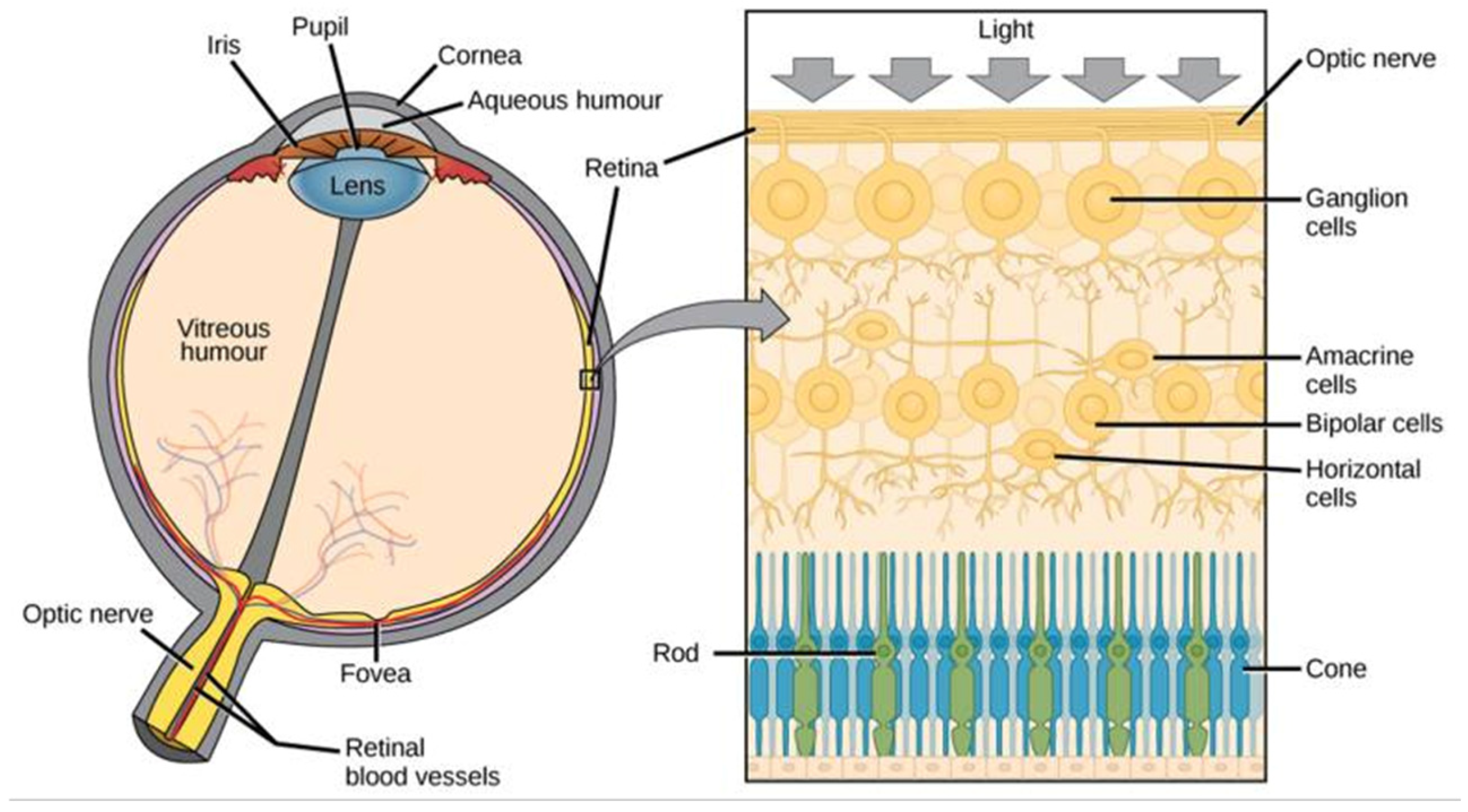

The retina’s structural and vascular integrity has long been considered a surrogate marker for central nervous system (CNS) health (

Figure 7). With the advent of high-resolution ocular imaging and artificial intelligence, researchers are now uncovering significant correlations between neurodegenerative conditions and musculoskeletal decline, offering new avenues for systemic diagnostics [37,38]. Retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) thinning, ganglion cell complex (GCC) loss, and microvascular anomalies in the optic nerve head have been linked to cognitive impairment and Parkinsonian motor dysfunction, which often coexist with musculoskeletal frailty and increased fall risk [38,39,40]. AI models trained on OCT data have shown sensitivity exceeding 87% for distinguishing Alzheimer’s patients from healthy controls based on RNFL and macular thickness maps [40,41]

In aging populations, musculoskeletal degeneration is frequently paralleled by declining cognitive and visual function—a phenomenon AI is helping to quantify [42,43]. For instance, conjunctive analysis of OCT-derived GCIPL thickness and MRI-based cortical atrophy can improve risk stratification for falls and vertebral fractures in elderly adults [39,40].

Moreover, ocular motor dysfunctions such as altered saccadic eye movements, measurable via AI-enhanced infrared tracking systems, have emerged as early indicators of cerebellar degeneration, which affects gait and postural control [39,43]. These biomarkers could play a key role in preemptively identifying patients at risk of musculoskeletal complications secondary to neurodegeneration [37,38,42].

As artificial intelligence tools evolve, they are increasingly trained on imaging data and multi-omics profiles, unlocking deeper insights into disease pathogenesis and treatment stratification [40,41]. Integrating genomic and proteomic data with imaging biomarkers has the potential to identify molecular mechanisms underlying the ocular-musculoskeletal axis [40,42].

For instance, AI algorithms analyzing retinal collagen expression profiles alongside OCT images have identified subtype-specific structural vulnerabilities in patients with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS)—a connective tissue disorder with musculoskeletal and ocular manifestations. Gharbiya et al. reported that ~16% of hypermobile EDS exhibited significant retinal atrophy and choroidal thickening. High myopia in hEDS patients was associated with changes in the vitreous extracellular matrix and scleral composition [42,44,45,46]. Another study found that patients with musculocontractural EDS (mcEDS), caused by dermatan sulfate epimerase deficiency, presented with ocular complications such as high refractive errors and retinal detachment [47]. These findings help explain patterns like early-onset joint hypermobility co-occurring with myopic degeneration or retinal detachment [42,43].

AI is also being applied to RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) datasets from synovial fluid and retinal biopsies, revealing overlapping inflammatory signatures in autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and uveitis [42,44]. This evidence supports the concept of shared proteomic fingerprints across organ systems, enabling cross-disciplinary diagnosis and treatment optimization [40,44]. In RA, AI-driven transcriptomic profiling of synovial tissue has uncovered distinct gene expression profiles linked to treatment responses, with studies demonstrating the potential to accurately predict patient outcomes to standard biological therapies [49]. Similarly, single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has been used in ocular disease to characterize intraocular leukocytes in anterior uveitis, identifying unique immune cell populations and expression patterns associated with disease activity [50].

Quantum-enhanced models, now in early development, show promise for integrating hundreds of thousands of gene-expression markers and proteomic sequences with structural imaging data in near real-time. For example, the Structural Analysis of Gene and protein Expression Signatures (SAGES) method combines sequence-based predictions and 3D structural models to analyze expression data, enhancing the understanding of protein evolution and function [48]. While the application of quantum-enhanced models in this context is still in early development, integrating multi-omics data with imaging holds promise for identifying patients at risk for drug-induced musculoskeletal toxicity or predicting the progression of ocular findings to systemic diseases.

AI-Enhanced Surgical Interventions

Robotic-Assisted Orthopedic and Ophthalmic Systems

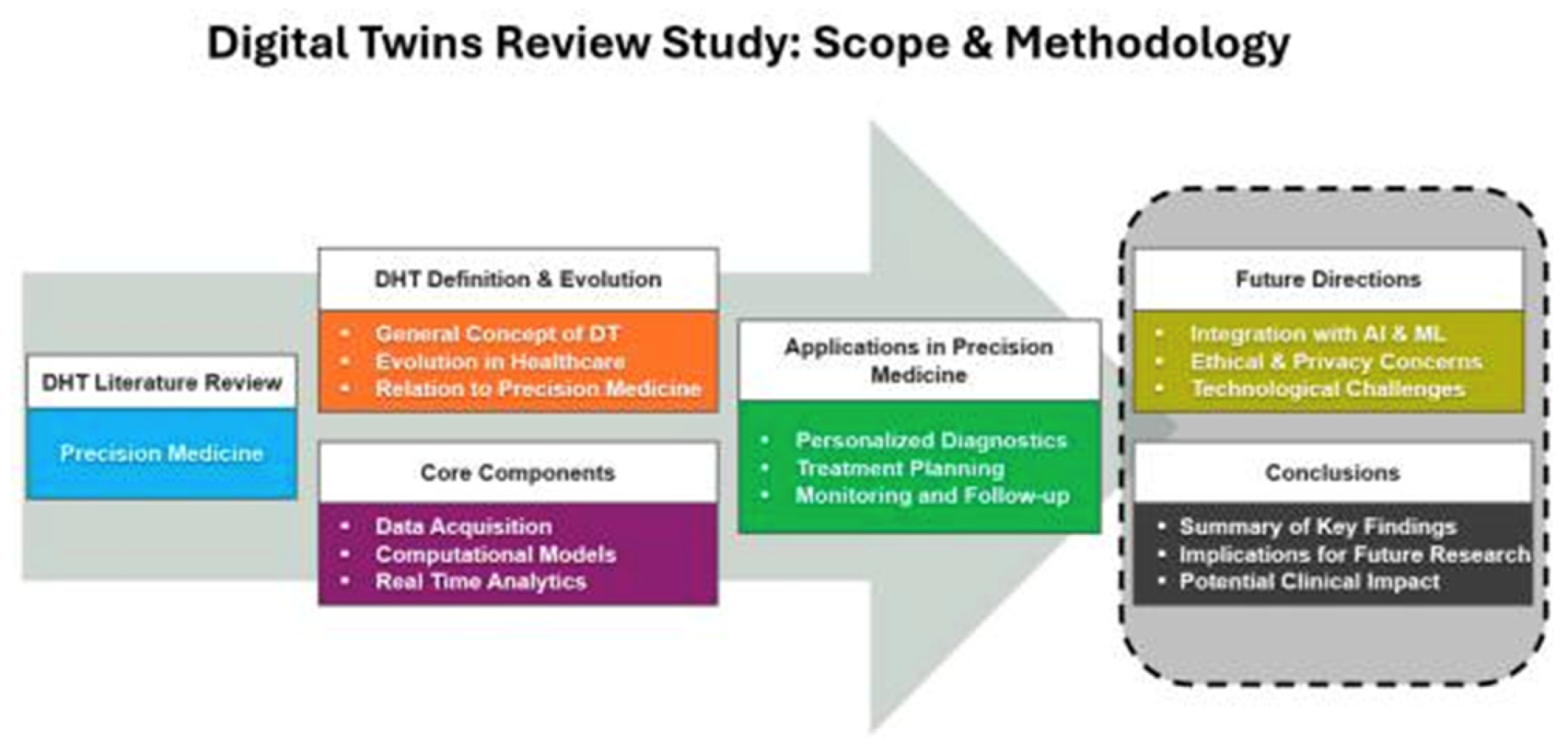

Digital twin technology—virtual, AI-enhanced replicas of individual patients—is emerging as a transformative tool in precision medicine (

Figure 8). By modeling patient-specific anatomical and biomechanical data, digital twins can simulate disease progression and surgical outcomes in real-time [51,52]. In musculoskeletal care, digital twins have been used to replicate lumbar spine dynamics, predicting outcomes of spinal decompression surgery with 92.1% accuracy [51,52,53,54,55]. These twins integrate MRI, CT, and intraoperative OCT data to refine implant sizing, trajectory planning, and postoperative rehabilitation strategies [55].

Ophthalmology applications are also evolving. Corneal and retinal digital twins are being developed using OCT and adaptive optics data to simulate disease progression in glaucoma and age-related macular degeneration. These platforms allow testing of virtual interventions—such as IOP-lowering surgery or anti-VEGF injection timing—before real-world deployment [55]. The Siemens Healthineers Cardiac Digital Twin program is now being extended into orthopedic and ophthalmic use cases, offering predictive analytics incorporating genetic, proteomic, and radiologic profiles [51,55]. Such simulations enable clinicians to test multiple interventions in silico before entering the operating room [51,52,53,54,55].

AI-driven robotic platforms like Stryker’s Mako system enhance surgical precision by integrating real-time imaging feedback. The Mako system utilizes preoperative CT scans to create patient-specific 3D anatomical models, enabling surgeons to plan and execute procedures accurately. While the Mako system is primarily designed for orthopedic procedures, advancements in intraoperative imaging, such as optical coherence tomography (OCT), have shown promise in improving surgical outcomes in various specialties. For instance, intraoperative 3D imaging has been demonstrated to reduce pedicle screw-related complications and reoperations in spinal fusion surgeries [56,57]. Additionally, OCT angiography (OCTA) has emerged as a valuable tool in visualizing choroidal neovascularization in diabetic patients, aiding in the assessment and management of diabetic retinopathy [58]. These technologies, when integrated with AI algorithms, have the potential to dynamically adjust surgical trajectories based on live imaging metrics, further enhancing the precision and safety of surgical interventions.

In joint arthroplasty, AI-enhanced navigation systems achieve submillimeter implant alignment accuracy, with femoral cuts measured within and tibial cuts within of CT measurements [52,59,60]. Autonomous surgical robots have shown high accuracy in pedicle screw placement in spine surgeries, with studies reporting accuracy rates up to 99%, resulting in smaller incisions, reduced blood loss, and shorter hospital stays [61,62]. Real-time feedback loops, incorporating intraoperative OCT and inertial measurement units (IMUs), enable adaptive control of robotic end-effectors, minimizing iatrogenic nerve damage during complex spinal revisions [55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63].

Postoperative Outcome Prediction

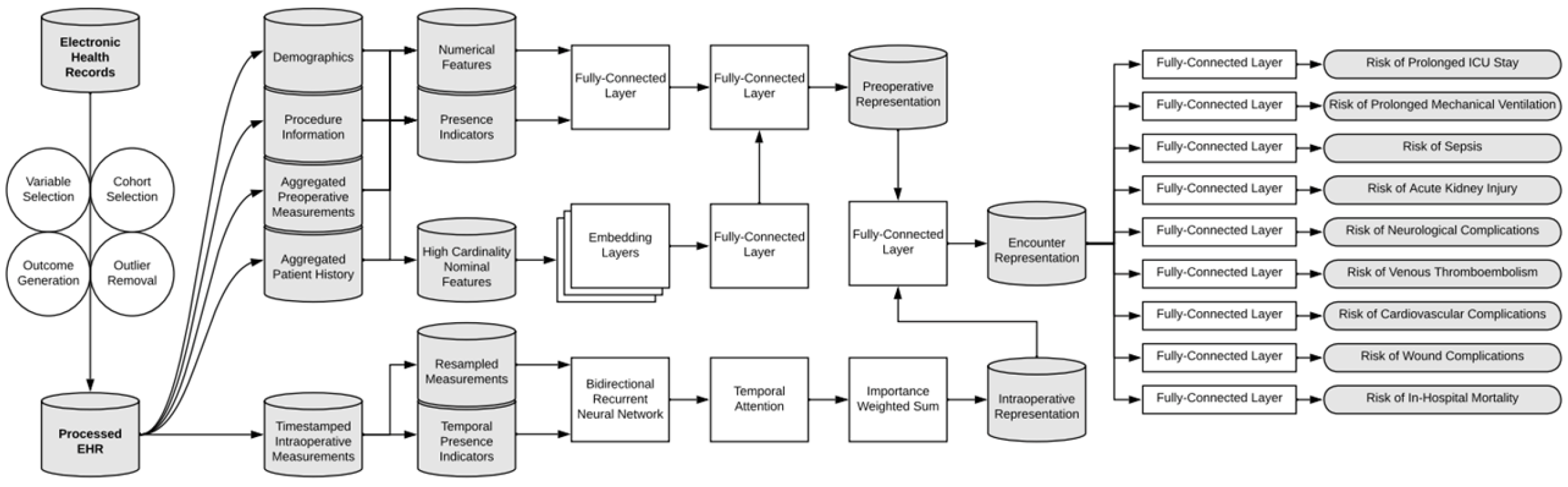

CNNs trained on electronic health records (EHR) and postoperative imaging accurately predict complications. Studies have shown that deep learning models outperform traditional machine learning methods in predicting postoperative outcomes, utilizing intraoperative physiological data for enhanced prognostication (

Figure 9) [64,65]. OCT-A has been used to visualize retinal vasculature in conditions like diabetic retinopathy and retinal vascular occlusions, offering quantitative metrics that could potentially correlate with systemic health indicators [66,67].

Predictive models analyzing saccadic eye movements and tear composition accurately forecast delirium risk post-orthopedic surgery, outperforming traditional clinical scores [68,69,70,71].

Translational Research and Clinical Trials

While artificial intelligence continues to redefine diagnostics and surgical precision in musculoskeletal and ocular medicine, its transition from laboratory innovation to clinical routine remains dependent on robust translational frameworks. Multiple prospective clinical trials and real-world implementation studies aim to validate AI-driven diagnostics, predictive modeling, and surgical assistance platforms.

One prominent example is the Bridge2AI Initiative, launched by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH). This initiative funds the development of ethically sourced, multimodal datasets designed for training clinical-grade AI algoriths and actively supports cross-disciplinary projects linking ocular imaging biomarkers (e.g., OCT metrics) to systemic pathologies such as osteoporosis and rheumatoid arthritis [67,72].

Similarly, ClinicalTrials.gov lists over 70 ongoing trials involving AI-assisted orthopedic or ophthalmic diagnostics. For example, a prospective study (NCT05369423) evaluates an AI-powered retinal imaging platform for predicting bone density loss and fracture risk in postmenopausal women, which could replace DEXA scans in resource-limited settings [73]. Notably, a prospective study (NCT05369423) evaluates an AI-powered retinal imaging platform for predicting bone density loss and fracture risk in postmenopausal women, potentially replacing DEXA scans in resource-limited settings [73].

Another study (NCT05921345) investigates the use of AI-enhanced portable OCT devices in mobile musculoskeletal clinics, measuring the effectiveness of RNFL-based biomarkers in predicting spinal degeneration across ethnically diverse populations [74].

In orthopedic surgery, AI-powered navigation tools and robotic arms—such as those used in Stryker’s Mako platform—are clinically evaluated for postoperative complication reduction and precision enhancement [75]. The AI-ROBOT trial, a multi-center initiative in the European Union, compares standard spinal fusion outcomes with those assisted by AI-guided robotic systems (ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT05844498) [67,71].

These translational studies are essential for regulatory approvals, clinician adoption, patient trust, and evidence-based reimbursement policies. Embedding explainable AI (XAI) and incorporating human factors analysis into these trials will further ensure that these systems are accurate but also usable, interpretable, and scalable [64].

Emerging Imaging Technologies and AI Integration

High-Field MRI and Photon-Counting CT

Recent advancements in imaging technology have significantly enhanced musculoskeletal diagnostics. The advent of 3-tesla MRI scanners— such as those from Englewood Health— enhances spatial resolution by 40% over conventional 1.5 T systems, enabling visualization of small joint structures like the wrist and ankle with unprecedented detail [64,76,77,78]. Complementing this, photon-counting detector CT (PCCT) reduces radiation doses while improving tissue contrast, facilitating early detection of osteolytic lesions in multiple myeloma [78,79,80]. These advancements synergize with AI algorithms for automated bone age estimation, reducing inter-observer variability from 14.3% to 2.1% in pediatric cohorts [24,67,81].

Next-Generation OCT Systems

Zeiss’s Cirrus 6000 OCT system, with its expanded reference database of 870 healthy eyes, supports data-driven workflows for diagnosing glaucoma and macular degeneration. This comprehensive database enhances individualized diagnostic approaches by accounting for diverse optic disc sizes and age variations [82]. Portable OCT devices, such as the Gen 3 low-cost system, employ balanced detection and quantum-optimized spectrometers to achieve dynamic ranges of 120 dB, rivaling commercial systems [12]. These devices integrate AI for real-time choroidal thickness mapping, detecting osteoporosis risk with 89% accuracy in rural clinics [73,84].

Challenges and Ethical Considerations

Data Interoperability and Algorithmic Bias

Heterogeneous datasets spanning DICOM, JPEG, and proprietary formats necessitate standardized frameworks like DICOM-ophthalmology extensions (WG-09) to enable seamless AI training [24,85]. Ethnic variations in choroidal thickness, observed in multi-ethnic cohorts, risk biasing osteoporosis prediction models unless training datasets are sufficiently diversified [6,86]. A 2025 ISAKOS survey revealed that 47.9% of orthopedic surgeons distrust AI due to limited real-world validation, underscoring the need for robust external testing [87].

Despite the promise of artificial intelligence in diagnostics and surgical planning, one of the key hurdles to widespread clinical adoption remains trust among clinicians and patients. Integrating explainable AI (XAI) into medical platforms enables clinicians to interpret algorithmic decisions transparently. Methods such as Grad-CAM heatmaps—which weight feature maps using class gradients—and saliency maps have been applied to CNNs analyzing OCT and MRI images, allowing verification of influential diagnostic features. For example, Grad-CAM visualizations in fracture classification models highlight periosteal contours and trabecular disruptions rather than image noise [88,89]. XAI tools also enhance shared decision-making by helping patients visualize disease processes. In ophthalmology, differential privacy (DP) techniques, such as pixel-level noise in retinal images, maintain diagnostic accuracy within 3% of non-anonymized models while preserving anonymity [90,91].

Privacy and Computational Resource Constraints

Federated learning frameworks decentralize data storage, enabling collaborative model training without sharing raw data (e.g., hospital networks training disease detection models locally). However, computational demands for 3D CNNs analyzing OCT volumes remain prohibitive in resource-limited settings [17,68].

Research Gaps and Translational Challenges

Etiological Mechanisms: While complement system dysregulation (e.g., elevated C1qb, C5, and CFH in Modic changes) is linked to disc degeneration, pathways connecting choroidal thinning to spinal pathologies remain unclear [6,92]

Non-Invasive ICP Monitoring: Current OCT-based ICP estimation lacks validation against invasive measurements, limiting its utility in managing SANS [68,93].

Long-Term AI Efficacy: Prospective trials are needed to validate AI’s role in preventing implant loosening, as current studies rely on retrospective cohorts [87].

Future Directions

Quantum Computing and Portable Diagnostics

Quantum machine learning, a novel integration of quantum computing and artificial intelligence, substantially enhances multi-omics data processing efficiency. This combination is particularly impactful in identifying subtle associations in complex biological systems [94]. For instance, recent research has demonstrated the capability of quantum computing to detect correlations between ocular collagen ratios and tendon elasticity in genetic disorders such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome [45,46,47]. By uncovering these associations, quantum-enabled analytics can significantly advance early diagnosis, offering novel biomarkers that facilitate targeted and preventive clinical strategies [95,96]. Such precision in diagnostics will be critical in personalized medicine, tailoring interventions based on individual patient profiles.

Portable diagnostic devices represent another frontier of healthcare innovation, significantly extending clinical capabilities into underserved regions. Handheld OCT-CNN platforms like the Optovue iWellness device exemplify this advancement, offering clinicians reliable tools for early detection of systemic diseases such as osteoporosis. These compact devices achieve high diagnostic accuracy [96]. By providing accessible and immediate screening capabilities, portable diagnostic devices improve healthcare delivery in rural and resource-limited environments, ultimately promising improved patient outcomes and greater healthcare equity.

Autonomous Surgical Systems

Next-generation autonomous robots represent a quantum leap in terms of surgical precision and patient healing outcomes. These advanced robotic devices, having learned from over 45 million procedure histories in their databases, can perform intricate surgery with awe-inspiring accuracy—to an unprecedented level of accuracy of 0.2mm. These technologies amplify surgical procedures such as AC reconstruction, and recovery times have been reduced by an average of 4.3 weeks. The precision is due to the reduced tissue trauma, recovery times, and enhanced patient satisfaction with improved outcomes. Furthermore, AI-human hybrid surgical platforms are emerging that blend autonomous robotics with real-time intraoperative OCT imaging guidance and traditional surgical intuition. This new technology greatly enhances surgical efficacy and safety, with a major reduction in complications related to spinal fusion surgery by some 29% over traditional methods. By integrating robotics capability and human judgment, these hybrid systems optimize surgery procedures for maximum effectiveness, enhance the precision of decision-making during critical moments of surgery, and establish new standards of minimally invasive surgery practices. The combination is set to transform the landscape of surgical procedures with enhanced and safer clinical results [96].

Global Collaborative Initiatives

International cooperation is required to address the challenges of dataset variability and to facilitate global access to advanced AI-driven medical technologies. The World Health Organization (WHO), in its 2021 report Ethics and Governance of Artificial Intelligence for Health, emphasizes inclusive, transparent, and equitable AI deployment, particularly in low-resource settings [98,99]. These principles are increasingly reflected in practical applications. For example, AI-powered portable imaging devices are deployed in underserved regions to improve healthcare access. In Rwanda, AI-enabled handheld fundus cameras have successfully screened for diabetic retinopathy, improving remote clinics’ referral uptake and diagnostic efficiency [100,101].

Similarly, while data on OCT-A-powered osteoporosis screening in rural South Asia remains limited, AI-based screening tools have demonstrated high accuracy in identifying bone loss in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, suggesting broader applicability in similar settings [100,101].

To support these advances, platforms like OpenMRS—a scalable, open-source electronic medical record system—enable the integration of AI tools tailored to local clinical needs without significant financial burden [100,101]. Complementing this, MONAI (Medical Open Network for AI), an open-source framework for healthcare imaging, provides domain-optimized tools for AI model training and deployment. Its flexibility fosters innovation and customization, making it particularly valuable in regions where proprietary solutions are unaffordable or impractical. Together, these tools and initiatives exemplify how ethical, collaborative, and open-source approaches can bridge global healthcare disparities through AI [100,101].

Conclusions

AI’s transformative impact on musculoskeletal and ocular medicine lies in its ability to decode complex interdependencies between seemingly disparate systems. In ophthalmology, AI algorithms enhance surgical planning by analyzing preoperative data and images, improving precision in cataract and retinal surgeries [102]. AI streamlines documentation and screening for ocular surface diseases, as demonstrated by tools integrating machine learning to optimize diagnostic workflows. Similarly, AI-powered image generation technology is reshaping clinical ophthalmic practice, though its adoption requires careful validation to mitigate misuse risks [103].

In musculoskeletal medicine, AI personalizes treatment plans for conditions like osteoarthritis by leveraging machine learning to recommend tailored interventions [104]. Musculoskeletal imaging benefits from AI tools that triage exams, detect fractures (including pediatric cases), and segment pathologies like vertebral fractures or meniscal tears with high sensitivity [3]. Advanced applications include radiomics for tumor differentiation and prognostication, though clinical translation remains challenging for multi-tissue assessments (e.g., joint MRI) [3].

From non-invasive biomarkers to autonomous surgical robots, AI bridges clinical specialties. Robotics in diagnostics, such as Robotic Ultrasound Systems (RUSS), standardize imaging and adapt to patient anatomy using AI, reducing dependency on operator skill [105]. In surgery, systems like the Smart Tissue Autonomous Robot (STAR) outperform human surgeons in tasks like bowel anastomosis, highlighting AI’s potential for precision and safety [106]. Integration with AR and 3D modeling further refines tumor resection margins in robotic breast surgery, as seen in studies combining MRI-derived models with real-time navigation [107].

While challenges in data standardization and ethical governance persist, the fusion of AI with emerging technologies like quantum computing positions it as the cornerstone of next-generation precision medicine. Rigorous validation through prospective trials—such as those evaluating AI’s role in osteoporosis detection via CT or diabetic retinopathy screening via OCT—is critical [3]. Interdisciplinary collaboration, exemplified by partnerships between radiologists and AI researchers, will be pivotal in translating these advancements into clinical practice, ensuring equitable access and improved global health outcomes [3].

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

No authors report any conflicts of interest nor any competing interests.

References

- Zetterlund C, Lundqvist LO, Richter HO. The Relationship Between Low Vision and Musculoskeletal Complaints. A Case Control Study Between Age-related Macular Degeneration Patients and Age-matched Controls with Normal Vision. J Optom. 2009;2(3):127-133. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-González, M.C., Gutiérrez-Sánchez, E., Sánchez-González, J.-M., Rebollo-Salas, M., Ruiz-Molinero, C., Jiménez-Rejano, J.J. and Pérez-Cabezas, V. (2019), Visual system disorders and musculoskeletal neck complaints: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci., 1457: 26-40. [CrossRef]

- Guermazi A, Omoumi P, Tordjman M, et al. How AI May Transform Musculoskeletal Imaging [published correction appears in Radiology. 2024 Jan;310(1):e249002. doi: 10.1148/radiol.249002.]. Radiology. 2024;310(1):e230764. [CrossRef]

- Bousson V, Benoist N, Guetat P, Attané G, Salvat C, Perronne L. Application of artificial intelligence to imaging interpretations in the musculoskeletal area: Where are we? Where are we going? Joint Bone Spine. 2023;90(1):105493. [CrossRef]

- Zhan H, Teng F, Liu Z, et al. Artificial Intelligence Aids Detection of Rotator Cuff Pathology: A Systematic Review. Arthrosc J Arthrosc Relat Surg Off Publ Arthrosc Assoc N Am Int Arthrosc Assoc. 2024;40(2):567-578. [CrossRef]

- Kim BR, Yoo TK, Kim HK, et al. Oculomics for sarcopenia prediction: a machine learning approach toward predictive, preventive, and personalized medicine. EPMA J. 2022;13(3):367-382. [CrossRef]

- Bellemo, V., Kumar Das, A., Sreng, S. et al. Optical coherence tomography choroidal enhancement using generative deep learning. npj Digit. Med. 7, 115 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Lau JK, Cheung SW, Collins MJ, et al. Repeatability of choroidal thickness measurements with Spectralis OCT images. BMJ Open Ophthalmology 2019;4:e000237. [CrossRef]

- clariushd. MSK AI - Unlock the power of AI for enhanced MSK ultrasound workflow | Clarius. March 17, 2023. Accessed April 10, 2025. https://clarius.com/technology/msk-ai/.

- Droppelmann G, Rodríguez C, Jorquera C, Feijoo F. Artificial intelligence in diagnosing upper limb musculoskeletal disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic tests. EFORT Open Rev. 2024;9(4):241-251. [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, R., Sounderajah, V., Martin, G. et al. Diagnostic accuracy of deep learning in medical imaging: a systematic review and meta-analysis. npj Digit. Med. 4, 65 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Gyftopoulos S, Lin D, Knoll F, Doshi AM, Rodrigues TC, Recht MP. Artificial Intelligence in Musculoskeletal Imaging: Current Status and Future Directions. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2019;213(3):506-513. [CrossRef]

- Gyftopoulos S, Lin D, Knoll F, Doshi AM, Rodrigues TC, Recht MP. Artificial Intelligence in Musculoskeletal Imaging: Current Status and Future Directions. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2019;213(3):506-513. [CrossRef]

- Tong MW, Zhou J, Akkaya Z et al. Artificial intelligence in musculoskeletal applications: a primer for radiologists. Diagn Interv Radiol . 2025 Mar;31(2):89-101. [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger O, Fischer P, Brox T. U-net: convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. 2015;234-241.

- Dosovitskiy A, Beyer L, Kolesnikov A, et al. an image is worth 16x16 words: transformers for image recognition at scale. 2021.

- Rehman MHU, Hugo Lopez Pinaya W, Nachev P, Teo JT, Ourselin S, Cardoso MJ. Federated learning for medical imaging radiology. Br J Radiol. 2023;96(1150):20220890. [CrossRef]

- Adnan, M., Kalra, S., Cresswell, J.C. et al. Federated learning and differential privacy for medical image analysis. Sci Rep 12, 1953 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Droppelmann G, Rodríguez C, Jorquera C, Feijoo F. Artificial intelligence in diagnosing upper limb musculoskeletal disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic tests. EFORT Open Rev. 2024;9(4):241-251. Published 2024 Apr 4. [CrossRef]

- Guan H, Yap PT, Bozoki A, Liu M. Federated Learning for Medical Image Analysis: A Survey. Arxiv.org. Published July 7, 2024. Accessed April 14, 2025. https://arxiv.org/html/2306.05980v4.

- Stefan Cristian Dinescu, Stoica D, Cristina Elena Bita, et al. Applications of artificial intelligence in musculoskeletal ultrasound: narrative review. Frontiers in medicine. 2023;10. [CrossRef]

- Rani S, Memoria M, Almogren A, et al. Deep learning to combat knee osteoarthritis and severity assessment by using CNN-based classification. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2024;25(1):817. Published 2024 Oct 16. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed AS, Hasanaath AA, Latif G, Bashar A. Knee Osteoarthritis Detection and Severity Classification Using Residual Neural Networks on Preprocessed X-ray Images. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13(8):1380. Published 2023 Apr 10. [CrossRef]

- Gitto S, Serpi F, Albano D, et al. AI applications in musculoskeletal imaging: a narrative review. Eur Radiol Exp. 2024;8:22. [CrossRef]

- Gilvaz VJ, Reginato AM. Artificial intelligence in rheumatoid arthritis: potential applications and future implications. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10:1280312. Published 2023 Nov 16. [CrossRef]

- Baek SD, Lee J, Kim S, Song HT, Lee YH. Artificial Intelligence and Deep Learning in Musculoskeletal Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Investig Magn Reson Imaging. 2023 Jun;27(2):67-74. [CrossRef]

- Wolterink JM, Mukhopadhyay A, Leiner T, Vogl TJ, Bucher AM, Išgum I. Generative Adversarial Networks: A Primer for Radiolo-gists. RadioGraphics. 2021;41(3):840-857. [CrossRef]

- Debs P, Fayad LM. The promise and limitations of artificial intelligence in musculoskeletal imaging. Front Radiol. 2023;3:1242902. Published 2023 Aug 7. [CrossRef]

- van Bentum, R. E., Baniaamam, M., Kinaci-Tas, B., van de Kreeke, J. A., Kocyigit, M., Tomassen, J., den Braber, A., Visser, P. J., ter Wee, M. M., Serné, E. H., Verbraak, F. D., Nurmohamed, M. T., & van der HorstBruinsma, I. E. (2020). Microvascular changes of the retina in ankylosing spondylitis, and the association with cardiovascular disease – the eye for a heart study. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism, 50(6), 1535-1541. [CrossRef]

- Castellino N, Longo A, Fallico M, et al. Retinal Vascular Assessment in Psoriasis: A Multicenter Study. Front Neurosci. 2021;15:629401. Published 2021 Jan 25. [CrossRef]

- Jiang L, Qian Y, Li Q, et al. Choroidal Thickness in Relation to Bone Mineral Density with Swept-Source Optical Coherence Tomography. J Ophthalmol. 2021;2021:9995546. Published 2021 Sep 25. [CrossRef]

- Sarah Ohrndorf, Anne-Marie Glimm, Mads Ammitzbøll-Danielsen, Mikkel Ostergaard, Gerd R Burmester - Fluorescence optical imaging: ready for prime time?: RMD Open 2021;7:e001497.

- Eraslan M, Cerman E, Yildiz Balci S, Celiker H, Sahin O, Temel A, Suer D, Tuncer Elmaci N (2016) The choroid and lamina cribrosa is affected in patients with Parkinson’s disease: enhanced depth imaging optical coherence tomography study. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 94, e68–e75.

- Brown GL, Camacci ML, Kim SD, et al. Choroidal Thickness Correlates with Clinical and Imaging Metrics of Parkinson’s Disease: A Pilot Study. J Parkinsons Dis. 2021;11(4):1857-1868. [CrossRef]

- Mads Ammitzbøll-Danielsen, Daniel Glinatsi, Lene Terslev, Mikkel Østergaard, A novel fluorescence optical imaging scoring system for hand synovitis in rheumatoid arthritis—validity and agreement with ultrasound, Rheumatology, Volume 61, Issue 2, February 2022, Pages 636–647. [CrossRef]

- Fekrazad S, Shahrabi Farahani M, Salehi MA, Hassanzadeh G, Arevalo JF. Choroidal thickness in eyes of rheumatoid arthritis patients measured using optical coherence tomography: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Surv Ophthalmol. 2024;69(3):435-440. [CrossRef]

- Marchesi N, Fahmideh F, Boschi F, Pascale A, Barbieri A. Ocular Neurodegenerative Diseases: Interconnection between Retina and Cortical Areas. Cells. 2021;10(9):2394. Published 2021 Sep 12. [CrossRef]

- Zhao B, Yan Y, Wu X, et al. The correlation of retinal neurodegeneration and brain degeneration in patients with Alzheimer’s disease using optical coherence tomography angiography and MRI. Front Aging Neurosci. 2023;15:1089188. Published 2023 Apr 12. [CrossRef]

- Murueta-Goyena, A., Romero-Bascones, D., Teijeira-Portas, S. et al. Association of retinal neurodegeneration with the progression of cognitive decline in Parkinson’s disease. npj Parkinsons Dis. 10, 26 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Hao, J., Kwapong, W.R., Shen, T. et al. Early detection of dementia through retinal imaging and trustworthy AI. npj Digit. Med. 7, 294 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Vitar RL. The role of retinal biomarkers in neurodegenerative disease detection. Retinai.com. Published June 27, 2024. Accessed April 14, 2025. https://www.retinai.com/articles/the-role-of-retinal-biomarkers-in-neurodegenerative-disease-detection.

- Wang J, Yang M, Tian Y, et al. Causal associations between common musculoskeletal disorders and dementia: a Mendelian randomization study. Frontiers in aging neuroscience. 2023;15. [CrossRef]

- Xu S, Wen S, Yang Y, et al. Association Between Body Composition Patterns, Cardiovascular Disease, and Risk of Neurodegenerative Disease in the UK Biobank. Neurology. 2024;103(4). [CrossRef]

- Rahmati, M., Shariatzadeh Joneydi, M., Koyanagi, A. et al. Resistance training restores skeletal muscle atrophy and satellite cell content in an animal model of Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Rep 13, 2535 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Asanad S, Bayomi M, Brown D, et al. Ehlers-Danlos syndromes and their manifestations in the visual system. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:996458. Published 2022 Sep 27. [CrossRef]

- Comberiati AM, Iannetti L, Migliorini R, Armentano M, Graziani M, Celli L, Zambrano A, Celli M, Gharbiya M, Lambiase A. Ocular Motility Abnormalities in Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome: An Observational Study. Applied Sciences. 2023; 13(9):5240. [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa Y, Koto T, Ishida T, et al. Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment in Musculocontractural Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome Caused by Biallelic Loss-of-Function Variants of Gene for Dermatan Sulfate Epimerase. J Clin Med. 2023;12(5):1728. Published 2023 Feb 21. [CrossRef]

- Zatorski N, Sun Y, Elmas A, et al. Structural Analysis of Genomic and Proteomic Signatures Reveal Dynamic Expression of Intrinsically Disordered Regions in Breast Cancer and Tissue. Preprint. bioRxiv. 2023;2023.02.23.529755. Published 2023 Feb 24. [CrossRef]

- CASABURI G, Holscher T, Lee M. Artificial Intelligence Applied to Transcriptomics Profiling of Synovial Tissue Biopsies Accurately Predicts Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients Who Will Respond or Be Refractory to Standard Biological Treatments [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2022; 74 (suppl 9). https://acrabstracts.org/abstract/artificial-intelligence-applied-to-transcriptomics-profiling-of-synovial-tissue-biopsies-accurately-predicts-rheumatoid-arthritis-patients-who-will-respond-or-be-refractory-to-standard-biological-trea/. Accessed April 14, 2025.

- Maren Kasper, Michael Heming, David Schafflick, Xiaolin Li, Tobias Lautwein, Melissa Meyer zu Horste, Dirk Bauer, Karoline Walscheid, Heinz Wiendl, Karin Loser, Arnd Heiligenhaus, Gerd Meyer zu Hörste (2021) Intraocular dendritic cells characterize HLA-B27-associated acute anterior uveitis eLife 10:e67396. [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, K.P., Raza, M.M. & Kvedar, J.C. Health digital twins as tools for precision medicine: Considerations for computation, implementation, and regulation. npj Digit. Med. 5, 150 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Papachristou K, Katsakiori PF, Papadimitroulas P, Strigari L, Kagadis GC. Digital Twins’ Advancements and Applications in Healthcare, Towards Precision Medicine. J Pers Med. 2024;14(11):1101. Published 2024 Nov 11. [CrossRef]

- Bcharah G, Gupta N, Panico N, et al. Innovations in Spine Surgery: A Narrative Review of Current Integrative Technologies. World Neurosurg. 2024;184:127-136. [CrossRef]

- Sun T, Wang J, Suo M, Liu X, Huang H, Zhang J, Zhang W, Li Z. The Digital Twin: A Potential Solution for the Personalized Diagnosis and Treatment of Musculoskeletal System Diseases. Bioengineering. 2023; 10(6):627. [CrossRef]

- Sun T, He X, Song X, Shu L, Li Z. The Digital Twin in Medicine: A Key to the Future of Healthcare?. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:907066. Published 2022 Jul 14. [CrossRef]

- Saarinen AJ, Suominen EN, Helenius L, Syvänen J, Raitio A, Helenius I. Intraoperative 3D Imaging Reduces Pedicle Screw Related Complications and Reoperations in Adolescents Undergoing Posterior Spinal Fusion for Idiopathic Scoliosis: A Retrospective Study. Children. 2022; 9(8):1129. [CrossRef]

- Kanno H, Handa K, Murotani M, Ozawa H. A Novel Intraoperative CT Navigation System for Spinal Fusion Surgery in Lumbar Degenerative Disease: Accuracy and Safety of Pedicle Screw Placement. J Clin Med. 2024;13(7):2105. Published 2024 Apr 4. [CrossRef]

- Waheed NK, Rosen RB, Jia Y, et al. Optical coherence tomography angiography in diabetic retinopathy. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2023;97:101206. [CrossRef]

- Albelooshi A, Muhieddine Hamie, Bollars P, et al. Image-free handheld robotic-assisted technology improved the accuracy of implant positioning compared to conventional instrumentation in patients undergoing simultaneous bilateral total knee arthroplasty, without additional benefits in improvement of clinical outcomes. Knee surgery, sports traumatology, arthroscopy. 2023;31(11):4833-4841. [CrossRef]

- Foley, K. A., Schwarzkopf, R., Culp, B. M., Bradley, M. P., Muir, J. M., & McIntosh, E. I. (2023). Improving alignment in total knee arthroplasty: a cadaveric assessment of a surgical navigation tool with computed tomography imaging. Computer Assisted Surgery, 28(1). [CrossRef]

- Khojastehnezhad MA, Youseflee P, Moradi A, Ebrahimzadeh MH, Jirofti N. Artificial Intelligence and the State of the Art of Or-thopedic Surgery. Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2025;13(1):17-22. [CrossRef]

- Reddy K, Gharde P, Tayade H, Patil M, Reddy LS, Surya D. Advancements in Robotic Surgery: A Comprehensive Overview of Current Utilizations and Upcoming Frontiers. Cureus. 2023;15(12):e50415. Published 2023 Dec 12. [CrossRef]

- Fisher C, Harty J, Yee A, et al. Perspective on the integration of optical sensing into orthopedic surgical devices. J Biomed Opt. 2022;27(1):010601. [CrossRef]

- Shickel, B., Loftus, T.J., Ruppert, M. et al. Dynamic predictions of postoperative complications from explainable, uncertainty-aware, and multi-task deep neural networks. Sci Rep 13, 1224 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Balch JA, Ruppert MM, Shickel B, et al. Building an automated, machine learning-enabled platform for predicting post-operative complications. Physiol Meas. 2023;44(2):024001. Published 2023 Feb 9. [CrossRef]

- Ong CJT, Wong MYZ, Cheong KX, Zhao J, Teo KYC, Tan T-E. Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography in Retinal Vascular Disorders. Diagnostics. 2023; 13(9):1620. [CrossRef]

- McLean, K.A., Sgrò, A., Brown, L.R. et al. Multimodal machine learning to predict surgical site infection with healthcare workload impact assessment. npj Digit. Med. 8, 121 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Price HB, Song G, Wang W, et al. Development of next generation low-cost OCT towards improved point-of-care retinal imaging. Biomed Opt Express. 2025;16(2):748-759. [CrossRef]

- van der Kooi AW, Rots ML, Huiskamp G, et al. Delirium detection based on monitoring of blinks and eye movements. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22(12):1575-1582. [CrossRef]

- Noah AM, Spendlove J, Tu Z, et al. Retinal imaging with hand-held optical coherence tomography in older people with or without postoperative delirium after hip fracture surgery: A feasibility study. PLoS One. 2024;19(7):e0305964. Published 2024 Jul 16. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi I, Rajai Firouzabadi S, Hosseinpour M, et al. Using artificial intelligence to predict post-operative outcomes in congenital heart surgeries: a systematic review [published correction appears in BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2025 Jan 10;25(1):14. doi: 10.1186/s12872-025-04479-0.]. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2024;24(1):718. Published 2024 Dec 20. [CrossRef]

- Green E, Gilchrist D, Sen S, Di Francesco V, Kaufman D, Morris S. Bridge to Artificial Intelligence (Bridge2AI). Genome.gov. Published March 11, 2025. Accessed April 14, 2025. https://www.genome.gov/Funded-Programs-Projects/Bridge-to-Artificial-Intelligence.

- Shapey IM, Sultan M. Machine learning for prediction of postoperative complications after hepato-biliary and pancreatic surgery. Artificial Intelligence Surgery. 2023;3(1):1-13. [CrossRef]

- Feng X, Gu J, Zhou Y. Primary total hip arthroplasty failure: aseptic loosening remains the most common cause of revision. Am J Transl Res. 2022;14(10):7080-7089. Published 2022 Oct 15.

- Rasouli JJ, Shao J, Neifert S, et al. Artificial Intelligence and Robotics in Spine Surgery. Global Spine J. 2021;11(4):556-564. [CrossRef]

- Latest MRI Technology Enables Faster, More Accurate Results. Englewood Health. Accessed April 11, 2025. https://www.englewoodhealth.org/news-and-stories/latest-mri-technology-enables-faster-more-accurate-results.

- Barr C, Bauer JS, Malfair D, et al. MR imaging of the ankle at 3 Tesla and 1.5 Tesla: protocol optimization and application to cartilage, ligament and tendon pathology in cadaver specimens. European Radiology. 2006;17(6):1518-1528. [CrossRef]

- Amrami KK, Felmlee JP. 3-Tesla imaging of the wrist and hand: techniques and applications. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol. 2008;12(3):223-237. [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar A, Kekatpure AL, Velagala VR, Kekatpure A. A Review on the Use of Artificial Intelligence in Fracture Detection. Cu-reus. 16(4):e58364. [CrossRef]

- Photon-counting Detector CT with Deep Learning Noise Reduction to Detect Multiple Myeloma Francis I. Baffour, Nathan R. Huber, Andrea Ferrero, Kishore Rajendran, Katrina N. Glazebrook, Nicholas B. Larson, Shaji Kumar, Joselle M. Cook, Shuai Leng, Elisabeth R. Shanblatt, Cynthia H. McCollough, and Joel G. Fletcher Radiology 2023 306:1, 229-236.

- Zhao K, Ma S, Sun Z, et al. Effect of AI-assisted software on inter- and intra-observer variability for the X-ray bone age assessment of preschool children. BMC Pediatr. 2022;22(1):644. Published 2022 Nov 8. [CrossRef]

- Zeiss. ZEISS Announces OCT Technology Enhancements to Better Support Growing Era of Data-Driven Patient Care. Ophthalmologyweb.com. Published June 4, 2024. Accessed April 14, 2025. https://www.ophthalmologyweb.com/Specialty/Retina/1315-News/613374-ZEISS-Announces-OCT-Technology-Enhancements-to-Better-Support-Growing-Era-of-Data-Driven-Patient-Care/?

- Hutton D. Zeiss announces OCT technology enhancements to better support growing era of data-driven patient care. Modern Retina. June 5, 2024. Accessed April 10, 2025. https://www.modernretina.com/view/zeiss-announces-oct-technology-enhancements-to-better-support-growing-era-of-data-driven-patient-care.

- Mjöberg B. Hip prosthetic loosening: A very personal review. World J Orthop. 2021;12(9):629-639. Published 2021 Sep 18. [CrossRef]

- Lum F, Lee AY. WG-09 Ophthalmology. DICOM. Published October 23, 2023. Accessed April 14, 2025. https://www.dicomstandard.org/activity/wgs/wg-09.

- Bafiq R, Mathew R, Pearce E, et al. Age, Sex, and Ethnic Variations in Inner and Outer Retinal and Choroidal Thickness on Spectral-Domain Optical Coherence Tomography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;160(5):1034-1043.e1. [CrossRef]

- Familiari F, Saithna A, Martinez-Cano JP, et al. Exploring artificial intelligence in orthopaedics: A collaborative survey from the ISAKOS Young Professional Task Force. J Exp Orthop. 2025;12(1):e70181. Published 2025 Feb 24. [CrossRef]

- Conor O’Sullivan. Grad-CAM for Explaining Computer Vision Models. A Data Odyssey. Published January 31, 2025. Accessed April 14, 2025. https://adataodyssey.com/grad-cam/.

- Papastratis I. Explainable AI (XAI): A survey of recents methods, applications and frameworks. AI Summer. Published March 4, 2021. Accessed April 14, 2025. https://theaisummer.com/xai/.

- Luis Filipe Nakayama, Jiheon Choi, Hanwen Cui, Emil Ghitman Gilkes, Chenwei Wu, Xiyu Yang, Weiwei Pan, Leo Anthony Celi; Pixel Snow and Differential Privacy in Retinal fundus photos de-identification. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2023;64(8):2399.

- Tayebi Arasteh, S., Ziller, A., Kuhl, C. et al. Preserving fairness and diagnostic accuracy in private large-scale AI models for medical imaging. Commun Med 4, 46 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Heggli I, Teixeira GQ, Iatridis JC, Neidlinger-Wilke C, Dudli S. The role of the complement system in disc degeneration and Modic changes. JOR Spine. 2024;7(1):e1312. Published 2024 Feb 2. [CrossRef]

- Dong J, Li Q, Wang X, Fan Y. A Review of the Methods of Non-Invasive Assessment of Intracranial Pressure through Ocular Measurement. Bioengineering (Basel). 2022;9(7):304. Published 2022 Jul 11. [CrossRef]

- Kaur SM, Bhatia AS, Isaiah M, Gowher H, Kais S. Multi-Omic and Quantum Machine Learning Integration for Lung Subtypes Classification. arXiv.org. Published October 2, 2024. Accessed April 14, 2025. https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.02085.

- Athreya AP, Lazaridis KN. Discovery and Opportunities With Integrative Analytics Using Multiple-Omics Data. Hepatology. 2021;74(2):1081-1087. [CrossRef]

- Khalid M. LinkedIn. Linkedin.com. Published April 12, 2025. Accessed April 14, 2025. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/quantum-machine-learning-revolutionizing-precision-khalid-rph--gx2af/.

- Theodorakis N, Feretzakis G, Tzelves L, Paxinou E, Hitas C, Vamvakou G, Verykios VS, Nikolaou M. Integrating Machine Learning with Multi-Omics Technologies in Geroscience: Towards Personalized Medicine. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2024; 14(9):931. [CrossRef]

- Jasarevic T, ed. WHO issues first global report on Artificial Intelligence (AI) in health and six guiding principles for its design and use. www.who.int. Published June 28, 2021. Accessed April 14, 2025. https://www.who.int/news/item/28-06-2021-who-issues-first-global-report-on-ai-in-health-and-six-guiding-principles-for-its-design-and-use.

- Writer G. WHO Guidance: Ethics and Governance of Artificial Intelligence for Health. ICTworks. Published October 27, 2021. Accessed April 14, 2025. https://www.ictworks.org/who-guidance-artificial-intelligence-health/.

- Frija G, Salama DH, Kawooya MG, Allen B. A paradigm shift in point-of-care imaging in low-income and middle-income countries. EClinicalMedicine. 2023;62:102114. Published 2023 Jul 26. [CrossRef]

- Shaw J, Ali J, Atuire CA, et al. Research ethics and artificial intelligence for global health: perspectives from the global forum on bioethics in research. BMC Med Ethics. 2024;25(1):46. Published 2024 Apr 18. [CrossRef]

- Honavar SG. Eye of the AI storm: Exploring the impact of AI tools in ophthalmology. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2023;71(6):2328-2340. [CrossRef]

- Stevenson S, McDonnell PJ, Periman LM. Innovation Series: AI’s impact on managing ocular surface disease with Peter J. McDonnell, MD, and Laura M. Periman, MD. Ophthalmology Times. Published October 11, 2024. Accessed April 14, 2025. https://www.ophthalmologytimes.com/view/innovation-series-ai-s-impact-on-managing-ocular-surface-disease-with-peter-j-mcdonnell-md-and-laura-m-periman-md.

- Cooray S, Deng A, Dong T, et al. Artificial Intelligence in Musculoskeletal Medicine: A Scoping Review. touchREVIEWS in RMD. 2024;4(1). [CrossRef]

- Asamaka Industries Ltd. Investigating the Role of Robotics in Non-Invasive Medical Diagnostics and Screening. Automate. Published 2024. Accessed April 14, 2025. https://www.automate.org/robotics/news/-67.

- Rivero-Moreno Y, Rodriguez M, Losada-Muñoz P, et al. Autonomous Robotic Surgery: Has the Future Arrived?. Cureus. 2024;16(1):e52243. Published 2024 Jan 14. [CrossRef]

- Li T, Li C. Emerging trends in robotic breast surgery in the era of artificial intelligence. Plastic and Aesthetic Research. Published online March 10, 2025. [CrossRef]

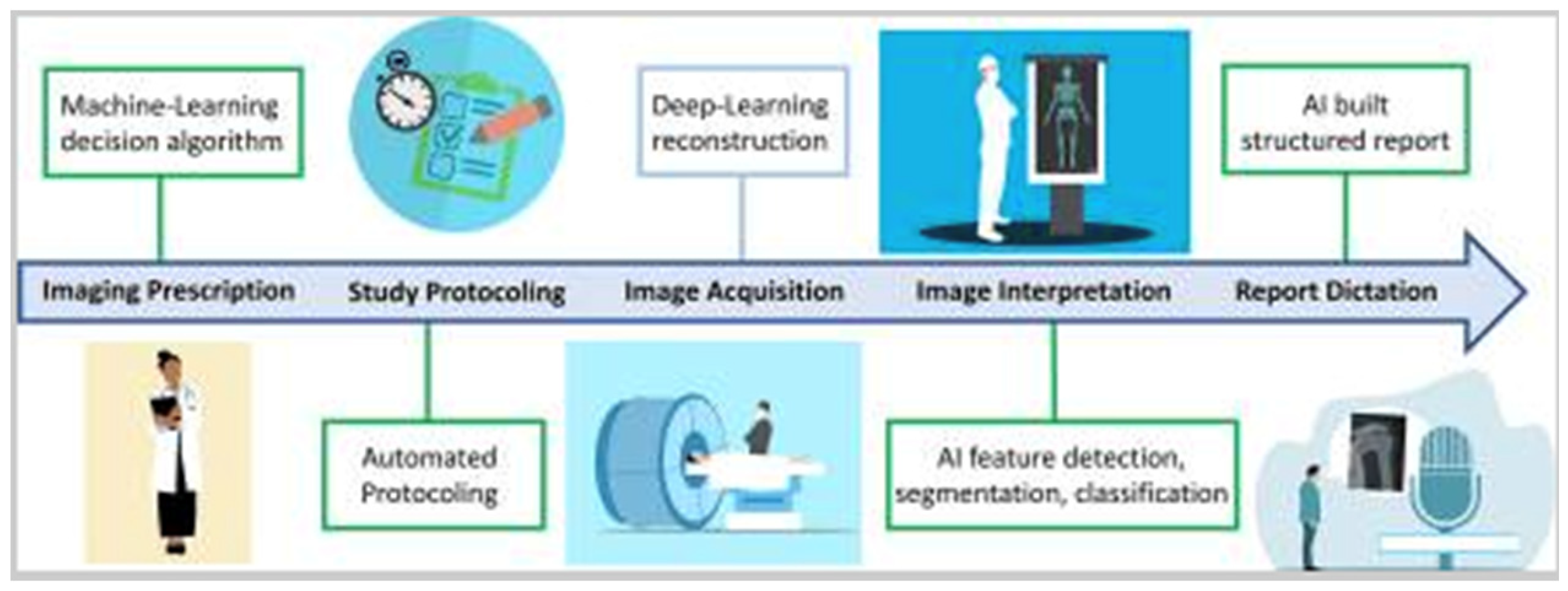

Figure 1.

The diagram illustrates the impact of AI on the radiologist’s workflow, highlighting areas of reduced workload (green boxes) and increased workload (blue box). Deep learning-based image reconstruction is expected to raise workload by shortening image acquisition times, enabling more examinations to be conducted within the same time frame [3].

Figure 1.

The diagram illustrates the impact of AI on the radiologist’s workflow, highlighting areas of reduced workload (green boxes) and increased workload (blue box). Deep learning-based image reconstruction is expected to raise workload by shortening image acquisition times, enabling more examinations to be conducted within the same time frame [3].

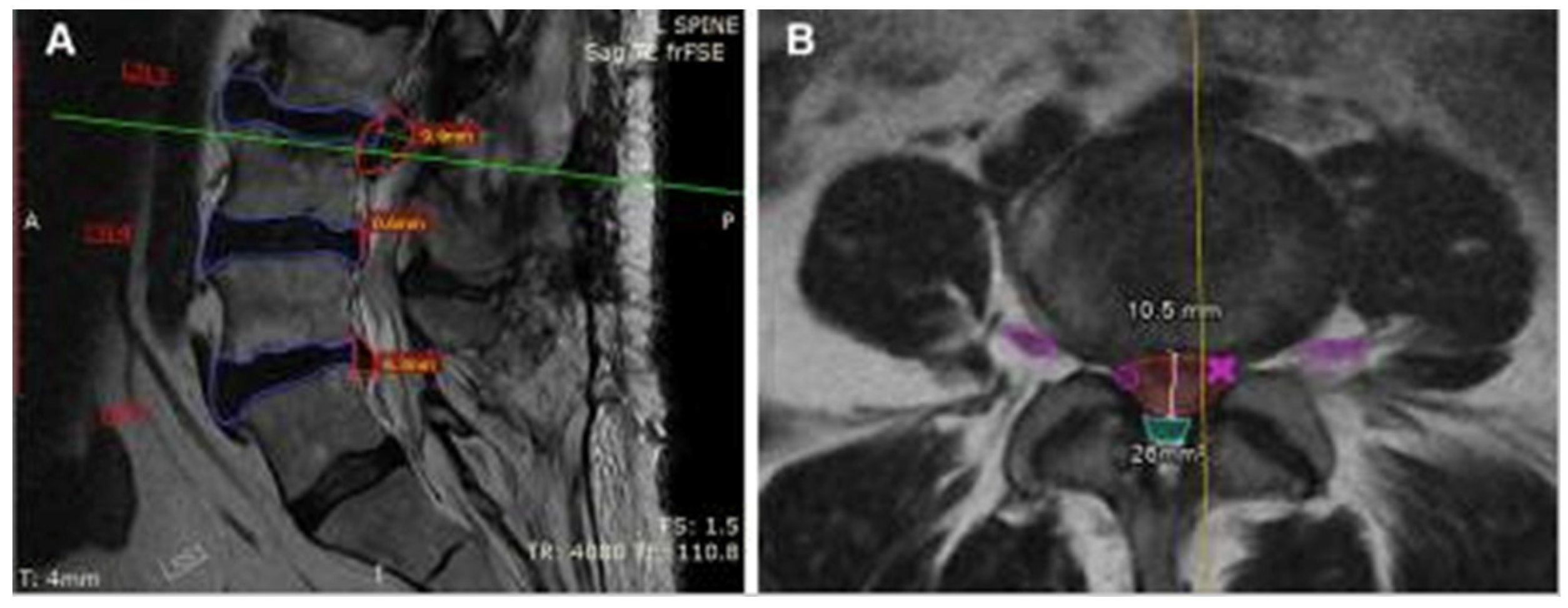

Figure 2.

MRI of the lumbar spine in a 68-year-old woman using sagittal (A) and axial (B) T2-weighted fast spin-echo sequences. CoLumbo software (Smart Soft Healthcare) automatically segments key spinal structures—vertebral discs (blue), herniated discs (red), dural sac (cyan), and foraminal nerve roots (pink)—and quantifies herniation size and dural sac area. Green and yellow lines indicate the levels corresponding to the axial and sagittal views, respectively. Imaging parameters include repetition time (TR) and echo time (TE) in milliseconds; scale bar = 5 mm [3].

Figure 2.

MRI of the lumbar spine in a 68-year-old woman using sagittal (A) and axial (B) T2-weighted fast spin-echo sequences. CoLumbo software (Smart Soft Healthcare) automatically segments key spinal structures—vertebral discs (blue), herniated discs (red), dural sac (cyan), and foraminal nerve roots (pink)—and quantifies herniation size and dural sac area. Green and yellow lines indicate the levels corresponding to the axial and sagittal views, respectively. Imaging parameters include repetition time (TR) and echo time (TE) in milliseconds; scale bar = 5 mm [3].

Figure 3.

Format of the novel U-net architecture. Reproduced via Creative Commons License from [14,15].

Figure 3.

Format of the novel U-net architecture. Reproduced via Creative Commons License from [14,15].

Figure 4.

Schematic for vision transformers (ViT). Reproduced via Creative Commons License from [14,16].

Figure 4.

Schematic for vision transformers (ViT). Reproduced via Creative Commons License from [14,16].

Figure 5.

Federated learning (FL) process for medical image analysis, including server and clients. The client trains a model on its local dataset, and the server collects all the models and calculates a global model to train the GANs [20].

Figure 5.

Federated learning (FL) process for medical image analysis, including server and clients. The client trains a model on its local dataset, and the server collects all the models and calculates a global model to train the GANs [20].

Figure 6.

Diagram of a sample convolutional neural network (CNN) architecture designed for binary image classification. The input image passes through five convolutional layers, each followed by a pooling layer that reduces spatial dimensions by a factor of four (from 320 × 320 down to 20 × 20). Each convolution layer uses four filters, chosen arbitrarily for this illustrative example. The convolutional layers extract features at increasing levels of abstraction, while the final fully connected layer handles classification. Output values indicate whether the image contains artifacts (1) or is artifact-free (0) [13].

Figure 6.

Diagram of a sample convolutional neural network (CNN) architecture designed for binary image classification. The input image passes through five convolutional layers, each followed by a pooling layer that reduces spatial dimensions by a factor of four (from 320 × 320 down to 20 × 20). Each convolution layer uses four filters, chosen arbitrarily for this illustrative example. The convolutional layers extract features at increasing levels of abstraction, while the final fully connected layer handles classification. Output values indicate whether the image contains artifacts (1) or is artifact-free (0) [13].

Figure 7.

Anatomy of eye and retina [37].

Figure 7.

Anatomy of eye and retina [37].

Figure 8.

Overview of the applications of Digital Twins in healthcare [52].

Figure 8.

Overview of the applications of Digital Twins in healthcare [52].

Figure 9.

Overview of the data processing pipeline and deep learning model architecture. Patient data were divided into static preoperative and dynamic intraoperative variables. Preoperative features were further categorized (continuous, binary, high-cardinality) and processed accordingly. The model used a data fusion approach, combining representations from a bidirectional recurrent neural network (for intraoperative data) and fully connected layers (for preoperative data) to simultaneously predict nine postoperative complications [64].

Figure 9.

Overview of the data processing pipeline and deep learning model architecture. Patient data were divided into static preoperative and dynamic intraoperative variables. Preoperative features were further categorized (continuous, binary, high-cardinality) and processed accordingly. The model used a data fusion approach, combining representations from a bidirectional recurrent neural network (for intraoperative data) and fully connected layers (for preoperative data) to simultaneously predict nine postoperative complications [64].

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).