Introduction

Globally, as of 2020, approximately 49.1 million people were blind, with an estimated 255 million experiencing moderate to severe vision impairment [

1]. Of those with severe visual impairment, around 89% reside in low and middle-income countries, exposing a substantial disparity in worldwide access to adequate eye care. A primary contributor to this gap is the insufficient supply of trained ophthalmologists and resources in impoverished and underserved communities [

2]. In countries such as India, where an estimated 63.64% of the entire population lives in rural areas as of 2023 [

3], the national shortage of qualified optometrists and ophthalmologists only exacerbates eye care accessibility issues. For a population the size of India’s, it is recommended to have at least 115,000 optometrists with four years of formal training. However, as of 2012, the India Optometry Federation reported only 49,000 practicing optometrists, of whom merely 9,000 had completed four-year degrees [

4]. This shortfall in adequately trained professionals contributes significantly to the fact that 88.2% of blindness cases in India are avoidable [

5]. As such, a large portion of the eye care workforce was undertrained, while the qualified professionals faced overwhelming caseloads, hindering timely and accurate diagnosis.

To address these challenges, this study proposes a standardized program for the examination of six of the most common ocular diseases worldwide, aiming to improve access to consistent and efficient diagnoses [

6]. Simple machine learning techniques such as KNN and Random Forest have demonstrated promising accuracy with tabular datasets as opposed to image-based datasets, suitable for resource-limited settings, but they often lack the complexity needed for high diagnostic precision [

7]. In contrast, deep learning (DL) models offer enhanced capabilities for rapid and accurate detection, surpassing conventional methods in handling complex ocular image analysis [

8].

Beyond improving global healthcare accessibility, deep learning classification models may serve as a valuable supplementary tool for both novice and experienced ophthalmologists. New practitioners with limited experience could benefit from DL models as secondary evaluators to ensure diagnostic accuracy. Similarly, even skilled ophthalmologists were found to be susceptible to diagnostic errors caused by fatigue, delays, or human error [

9]. For instance, the average diagnostic agreement between trainee ophthalmologists and gold-standard classifications is moderate at best, with a kappa score (measure of inter-rater reliability) of 0.541 [

10]. Incorporating deep learning models, as explored in this research, could help reduce misclassification rates and improve overall patient outcomes by providing a reliable diagnostic safety net.

This study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of a ResNet-based deep learning model for the classification of prevalent ocular diseases using retinal fundus images, with the objective of creating a scalable tool for early diagnosis in underserved settings. The research is limited to image-based diagnosis and does not include clinical variables or patient histories and assumes that technological interventions can reduce disparities in medical access and diagnostic quality.

Methodology

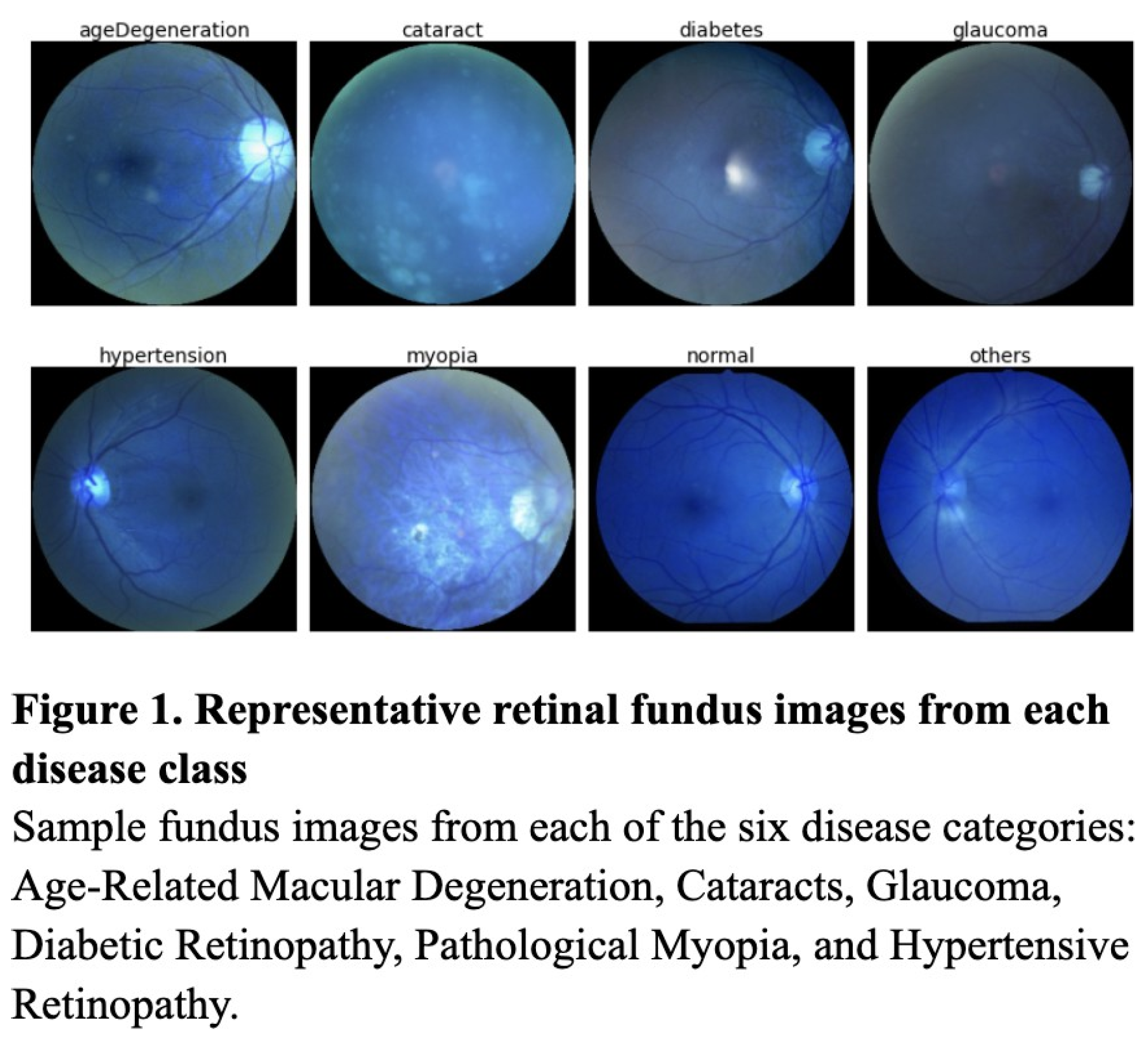

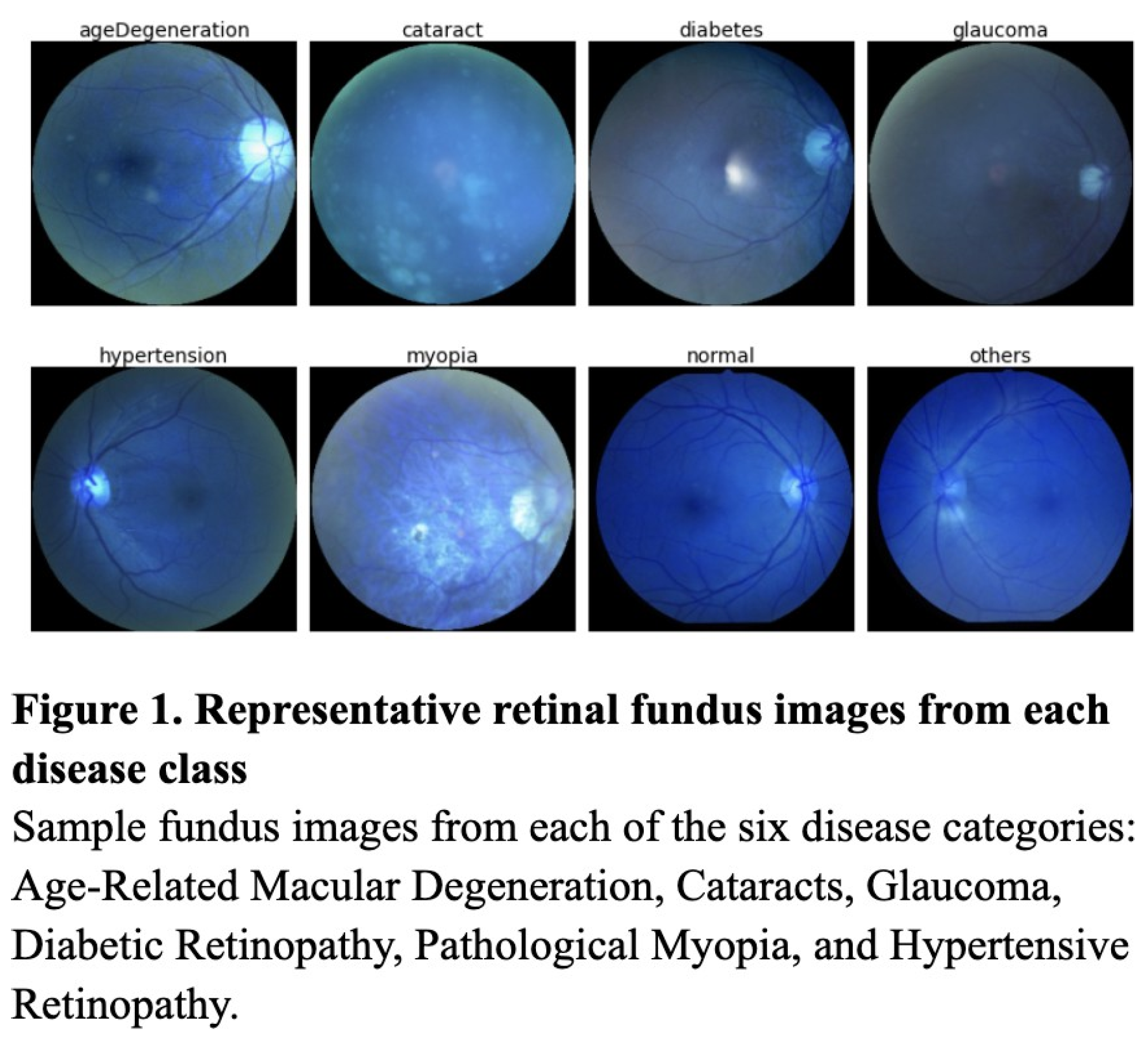

This study follows an experimental comparative design aimed at evaluating the classification performance of three supervised learning models—the KNN, Random Forest, and ResNet50—on a labeled medical image dataset. Image classification models were tested on a Kaggle dataset containing 6,392 retinal fundus images, images of the interior eye, from over 5,000 patients (Figure 1). These retinal fundus images were labeled for seven classes—Hypertensive Retinopathy, Age-Related Macular Degeneration, Cataracts, Glaucoma, Diabetic Retinopathy, and Pathological Myopia (Figure 1). To evaluate the efficacy of deep learning models such as the ResNet against simpler machine learning models, each model was trained on a dataset preprocessed through SMOTE, data augmentation, and up-sampling.

Data Preprocessing

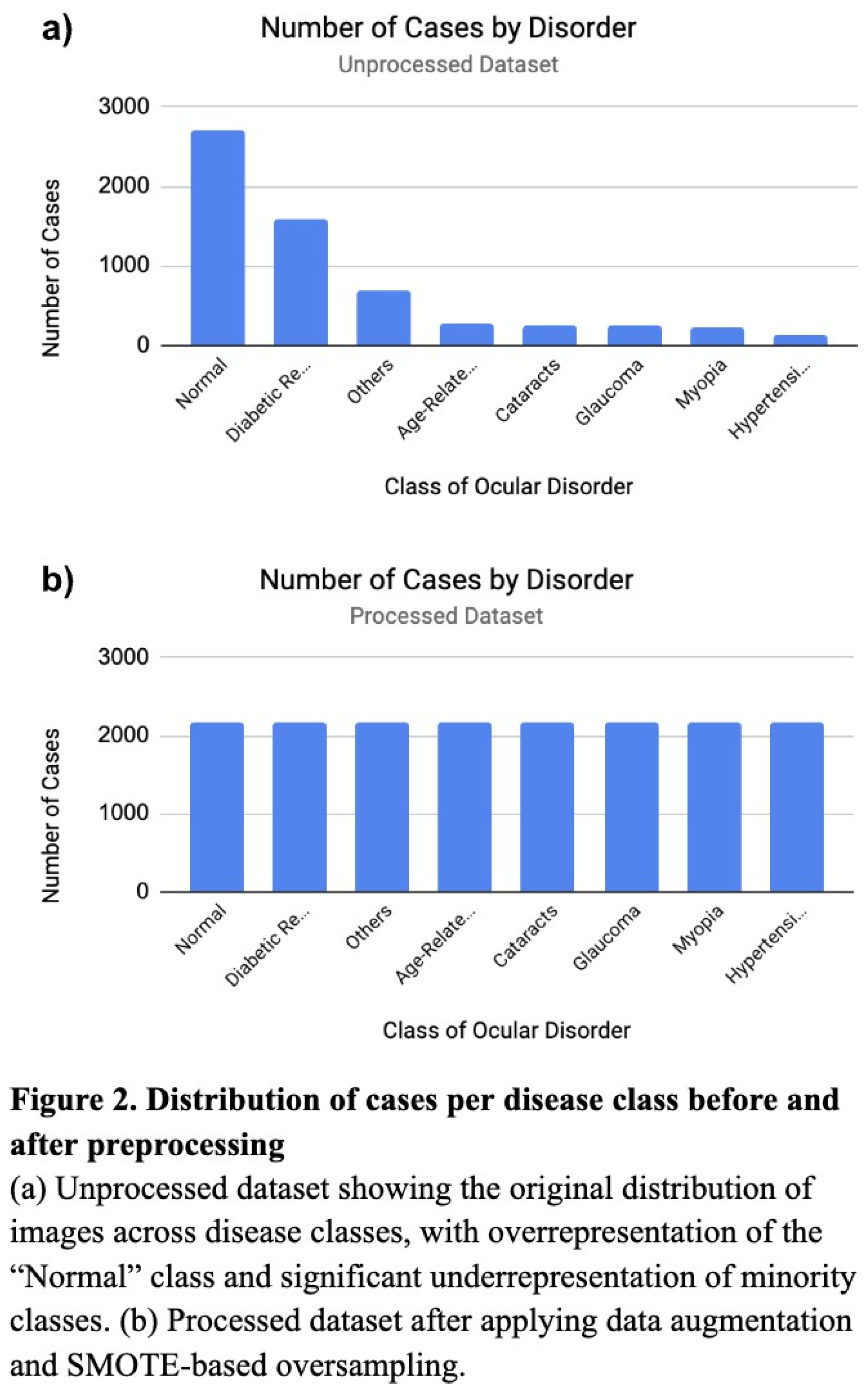

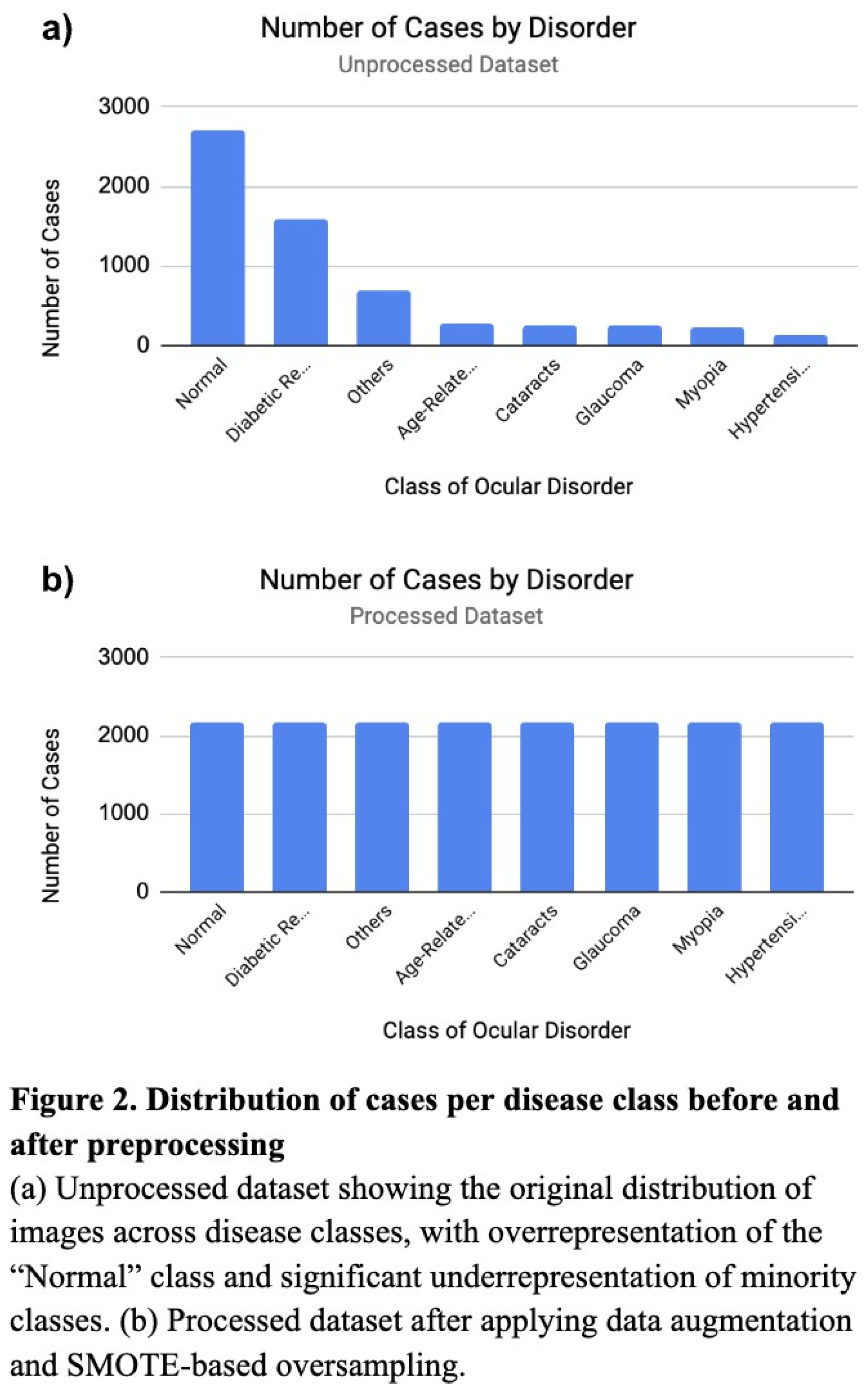

Before training and testing, the datasets were preprocessed to address significant class imbalances and enhance model generalization. The original datasets held significant class imbalances, with some minority classes containing only ~4.6% of the samples in the predominant class, “Normal” (Figure 2a). To manage such imbalances, the training dataset was expanded using Keras’ ImageDataGenerator with image transformations such as rotations (20°), shifts (0.2), shear (0.2), zoom (0.2), and horizontal flipping (Figure 2b). Following augmentation, the dataset was further balanced using SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique), which generated synthetic samples for underrepresented classesbased on feature-space interpolation. To ensure compatibility of the dataset with the ResNet model, sklearn’s LabelEncoder converted string class labels to numeric formats, then subsequently one-hot encoded to enable multiclass classification. The retinal fundus images were all maintained at a shape of (224, 224, 3) for neural network implementation, as (224, 224, 3) was the original size and offered best resolution.

Classification of Simple Machine Learning Models

The first model implemented was a K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) classifier, using the cuML GPU-accelerated NearestNeighbors module to supplement performance speed and algorithmic capacities. Instead of the conventional KNN classifier with majority voting, we applied a distance-weighted voting strategy for boosted precision. For each test instance, the algorithm identified the seven nearest neighbors (k = 7) based on Euclidean distance in the flattened image feature space [

1]. The choice of k = 7 proved best through empirical means, as too few neighbors made predictions volatile, while too many diluted the influence of relevant local patterns. Furthermore, we used inverse-distance weighting, assigning more influence to closer neighbors. A custom classification threshold of 0.4 was applied to the weighted label average to generate binary predictions. This threshold was tuned to reflect the multilabel nature of the task, where an image may exhibit features of more than one ocular disease, and helped to reduce overprediction.

The second model was a Random Forest classifier, an ensemble learning method that constructs multiple decision trees and classifies through voting and averaging the outputs for regression. By creating smaller, differently trained trees branching randomly from the main trees, the model is less overfitted, and more adaptive. We configured the model with 100 decision trees (n_estimators = 100) and a maximum depth of 20. The choice of 100 trees, experimentally, provided sufficient nodes without requiring excessive training time or overfitting. The maximum tree depth was limited to 20 to control the complexity of individual trees and prevent overfitting on training noise or irrelevant features. Additionally, we used sklearn’s MultiOutputClassifier for multilabel classification across the classes, allowing the model to independently predict the diagnosis for any individual image.

Classification of Deep Learning Models

The deep learning model whose performance was tested against the simple machine learning models was a convolutional neural network (CNN) based on the ResNet architecture, a deep learning model known for its ability to extract hierarchical features from complex images. Specifically, we used ResNet50, a 50-layer deep residual network pre-trained on ImageNet and modified it to be capable of multiclass classification. Residual networks, in general, can best extract intricate features from medical images, due to its ability to link across layers and prevent disappearance of the gradient [

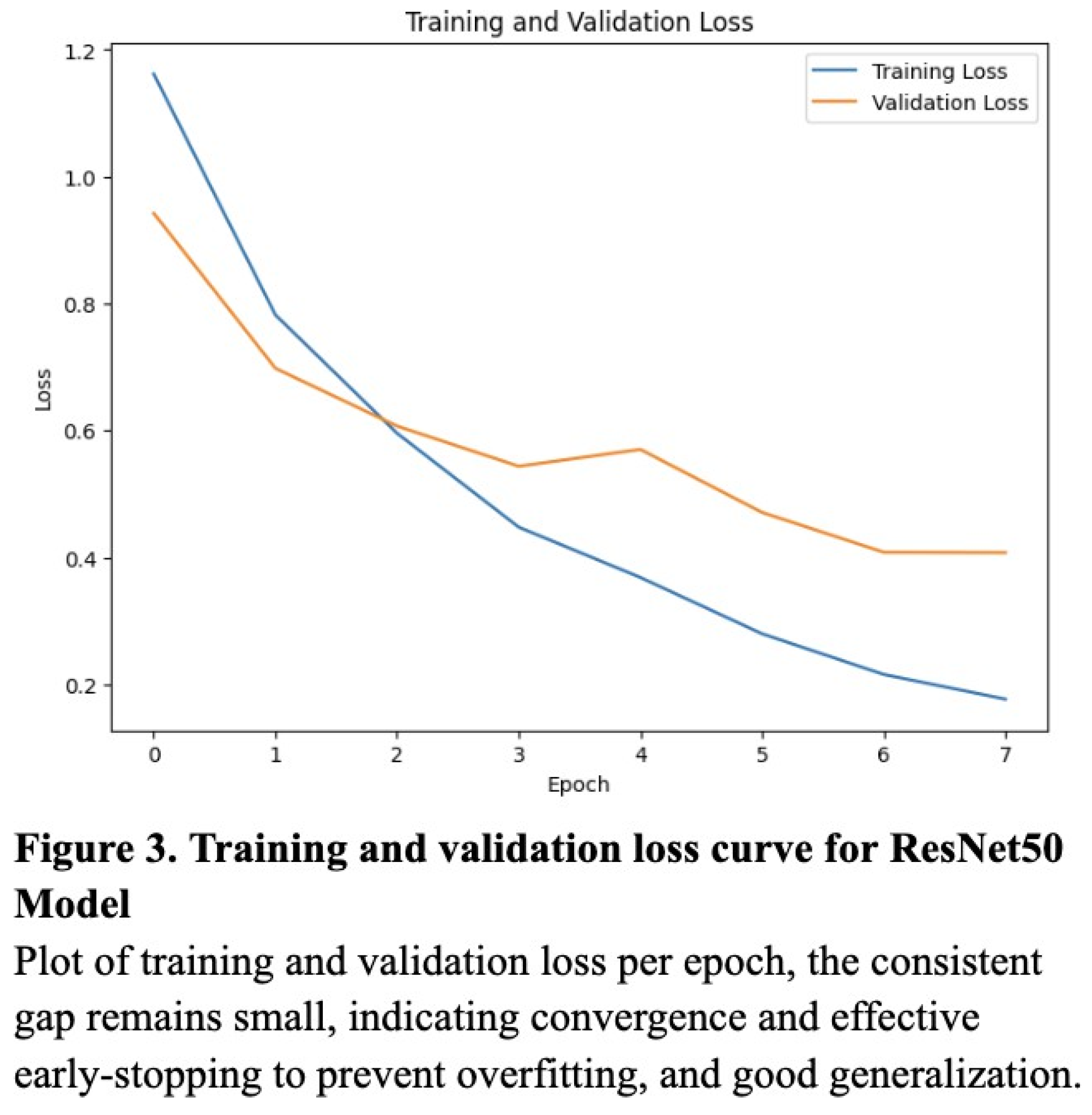

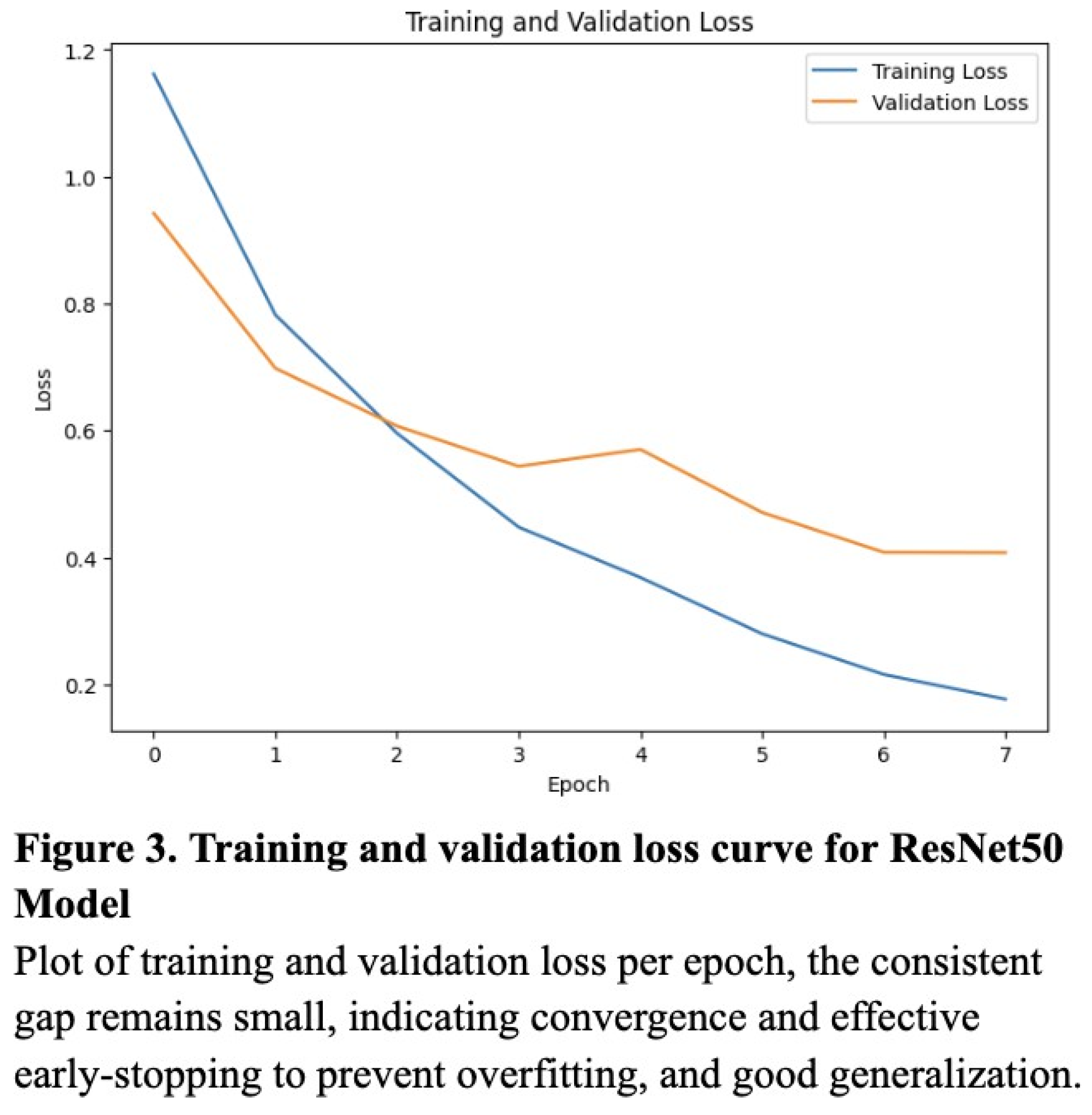

11]. The model was compiled using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.0001, whose lower learning rate allowed the model to adjust weights without overwriting useful learned features from ImageNet. Training was performed for 8 epochs, which was experimentally determined to strike the optimal balance between accuracy and overfitting (according to the validation loss curve) (

Figure 3). A categorical cross entropy loss function was used due to the multiclass nature of the problem, and during training, the dataset was shuffled, batched, and fed into the model using TensorFlow’s tf.data API for efficient GPU utilization.

Ethical Considerations

This study utilized a public dataset from Kaggle, and since no patient-level metadata was included, ethical review was not required. The study complies with data usage policies set by the dataset’s original publishers.

Results

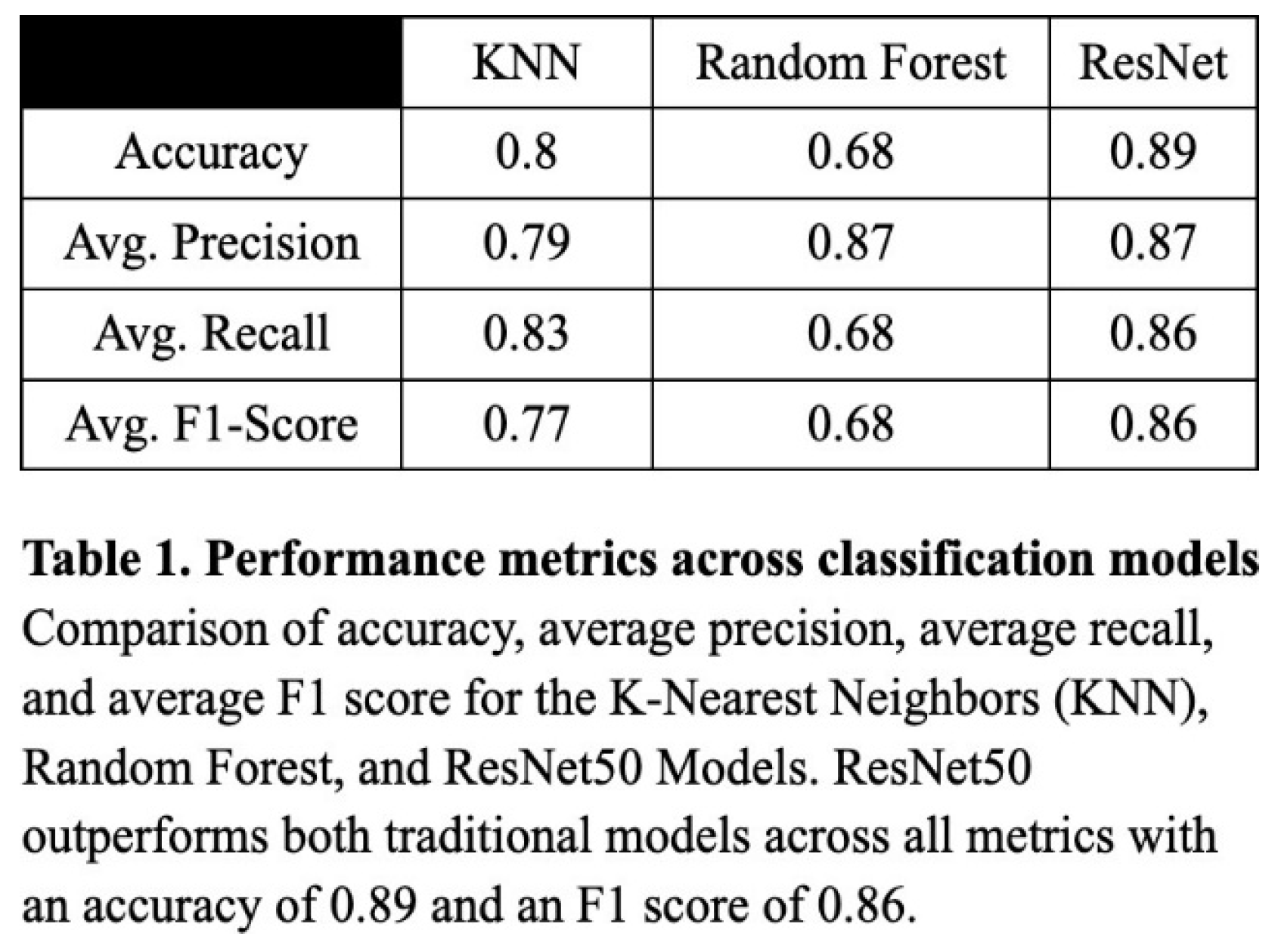

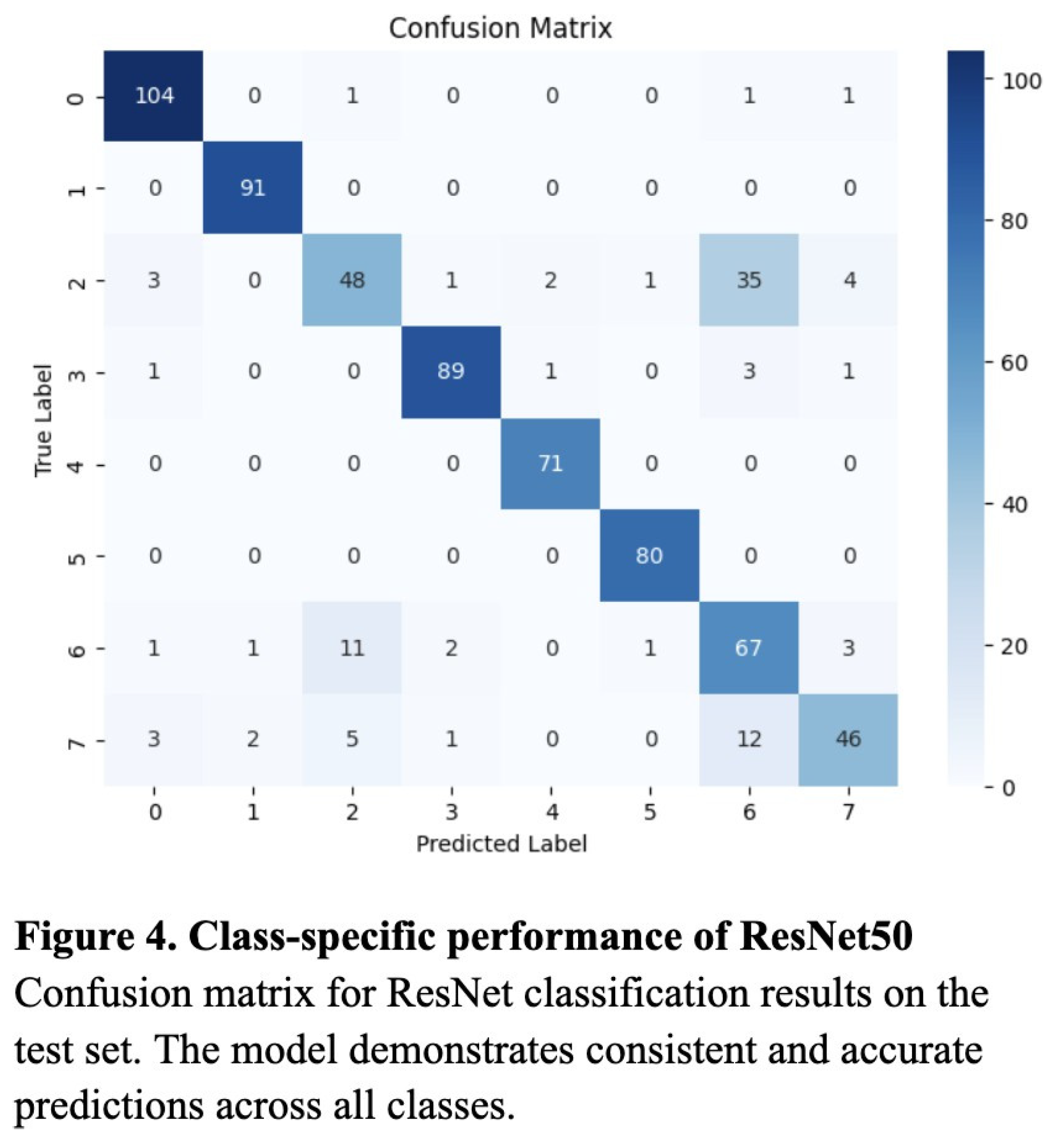

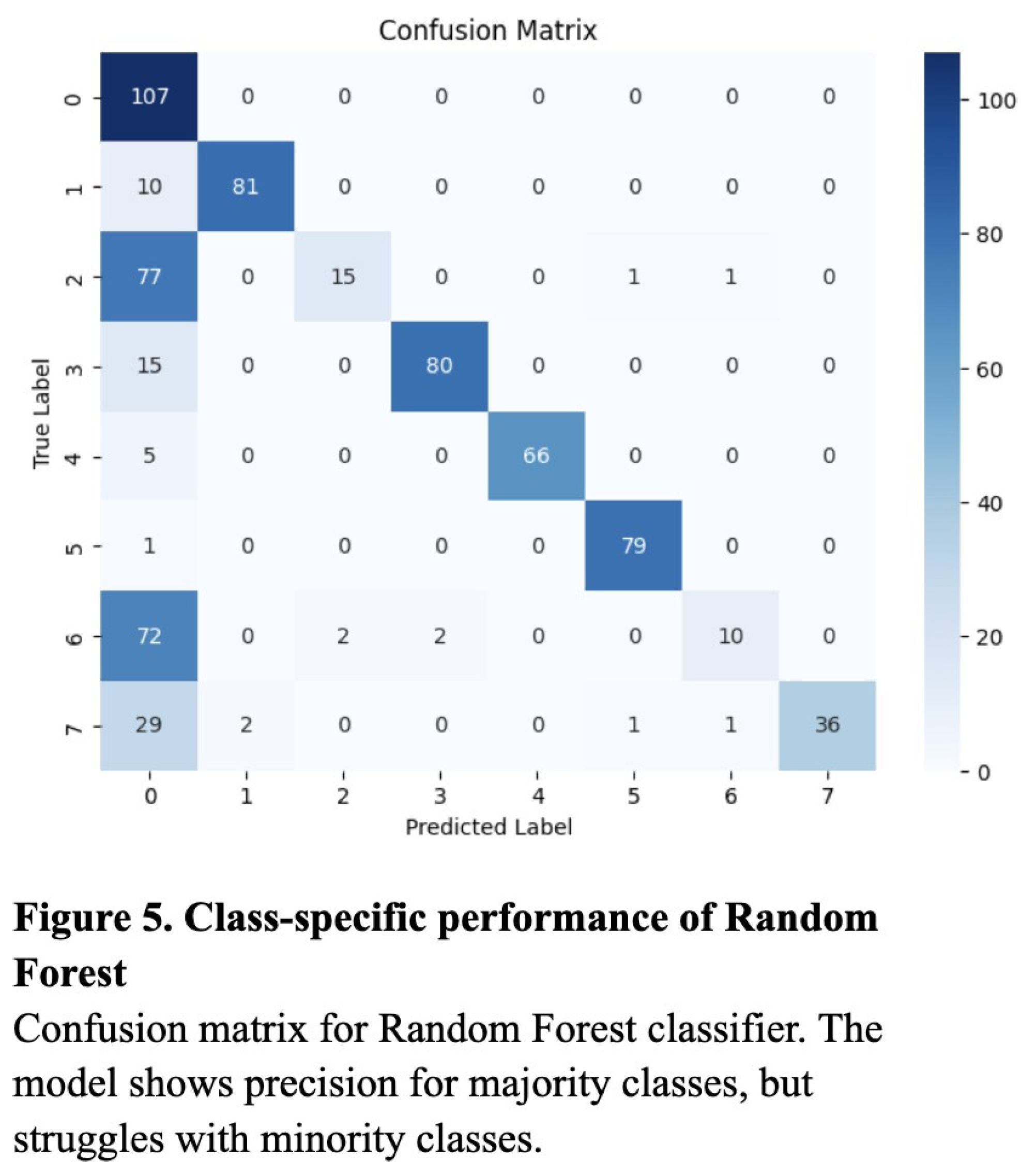

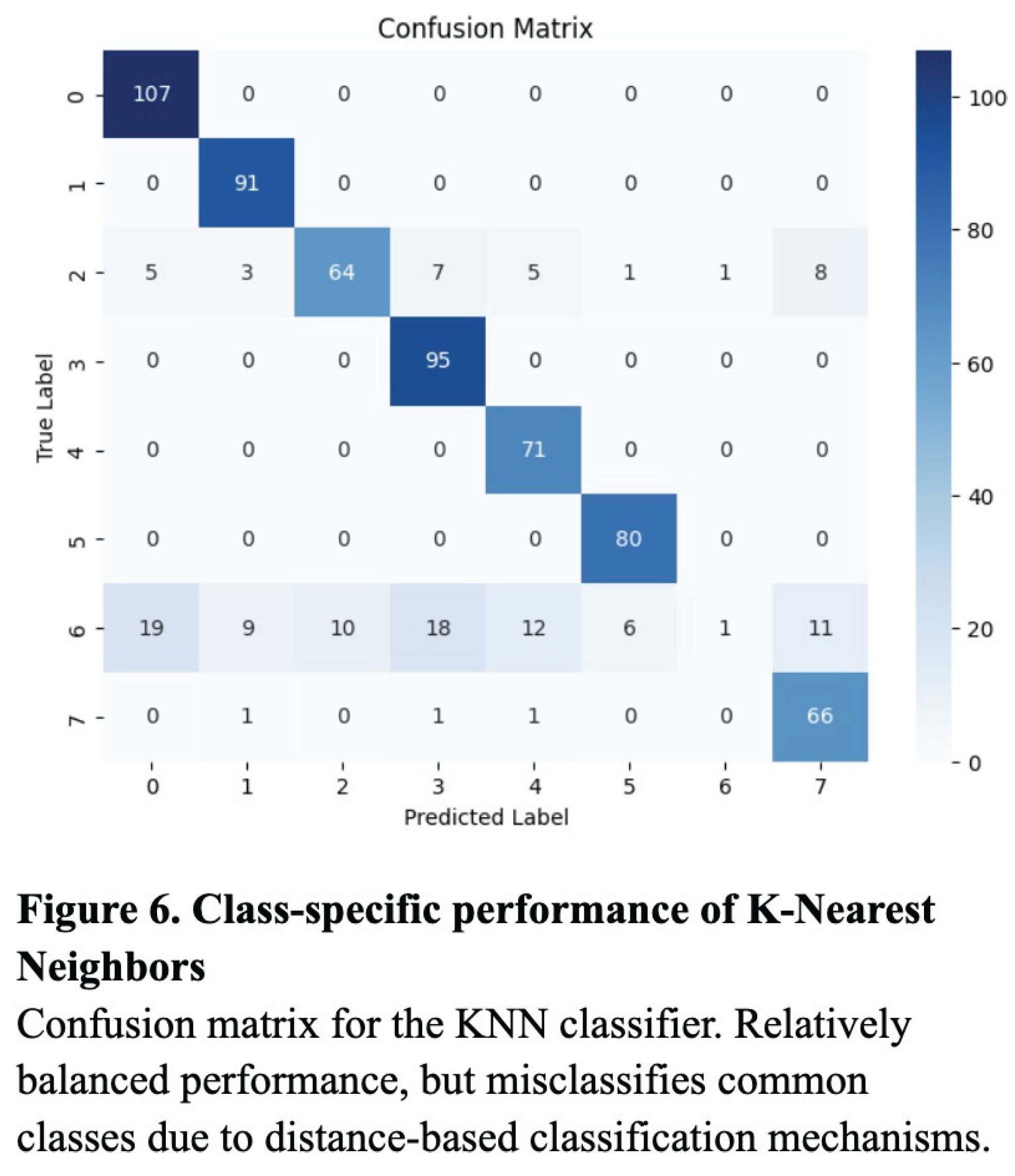

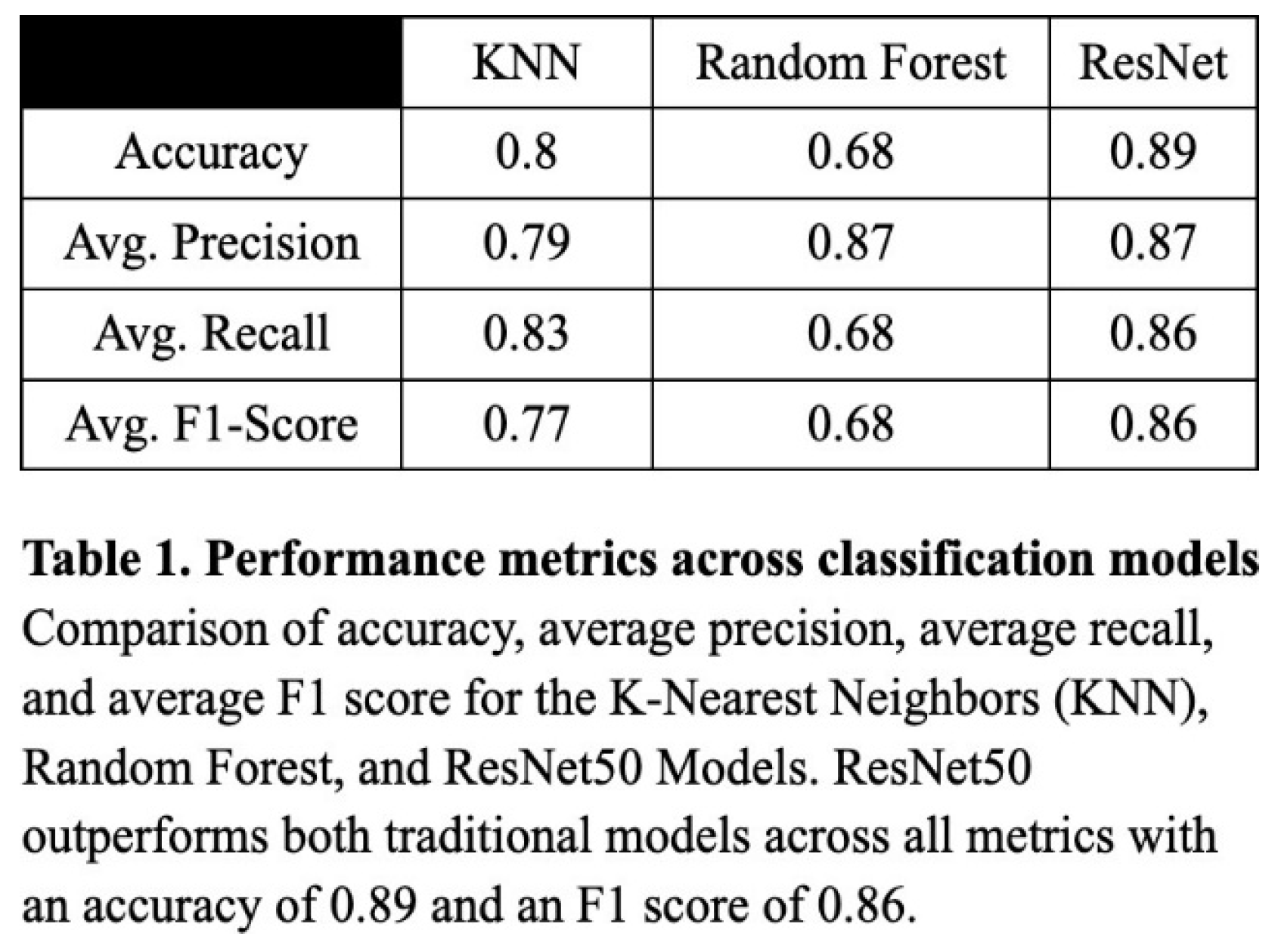

To evaluate the classification performance of the KNN, Random Forest, and ResNet50 models, we computed the accuracy, precision, recall, and the resulting F1 score for each model. Overall, the ResNet50 model performed most consistently across all metrics, with an accuracy of 0.89, a precision of 0.87, a recall of 0.86, and an F1 score of 0.86 (Table 1). The validation loss curve confirmed that the model was not overfitting on the data, and these were experimentally determined to be the optimized values (Figure 3). Though notably lower, the KNN model also performed well, attaining an accuracy of 0.80, a precision of 0.79, a recall of 0.83, and an F1 score of 0.77 (Table 1). The Random Forest model produced worse results, with 0.68 for recall, accuracy, and F1 score, and a relatively high precision of 0.87 (Table 1).

Additionally, while the confusion matrices of the KNN and Random Forest models demonstrated relatively successful classification across most categories, they tended to overpredict high-frequency classes such as “Normal” and “Diabetes,” likely due to bias toward majority classes (Figure 5 and Figure 6). In contrast, the ResNet’s confusion matrix revealed the most balanced classification across all six disease categories (Figure 4).

Discussion

The results support the conclusion that deep learning, particularly the ResNet50 architecture, is more effective than traditional machine learning approaches in the context of multiclass ocular disease classification. While both the KNN and Random Forest models benefited from preprocessing techniques such as SMOTE and image augmentation, they ultimately lacked the representational capacity required to capture the complexity of high-resolution medical images. The KNN model’s high recall indicated its strength in detecting true positive cases, due to its inverse-distance voting and thresholding strategy, but its lower F1 score reflected inherent limitations in precision and susceptibility to overclassification for too-similar categories. The Random Forest model, despite a high precision, had reduced sensitivity to minority classes, resulting in low recall, and more unbalanced predictions.

The superior performance of ResNet50 can be attributed to its residual connections, which help preserve gradient flow for more effective learning. By implementing pre-trained ImageNet weights and adapting the classification head for this specific multiclass task, the model was able to transfer generalized visual features to a specific ocular disease. The model’s balanced F1 score and confusion matrix results indicate its ability to minimize both false negatives and false positives, which is an especially important feature in clinical diagnostic systems where both situations can have life-changing outcomes on patients.

Despite the strengths of the ResNet50, certain disease categories, such as “Diabetes” and “Others,” remained challenging to distinguish, likely due to subtle visual similarities. These misclassifications indicate the need for region-specific attention mechanisms to better highlight the features of certain conditions. Moreover, although data augmentation and SMOTE reduced class imbalance, extremely rare categories may still have been underrepresented during training, potentially limiting model sensitivity.

Future improvements could include the use of images with inconsistent lighting and resolution, to validate the model’s performance in a real-world setting with less controlled variables. Overall, however, these findings reinforce the potential of deep learning as a solution for automated ocular disease screening, particularly in settings where early detection is critical but specialist access remains limited.

Acknowledgements

The author of this paper would like to acknowledge the support from Anand Shankar and those who formed the datasets used in this experiment.

References

- Bourne, R. R. A., et al. “Global Prevalence of Blindness and Distance and Near Vision Impairment in 2020: Progress towards the Vision 2020 Targets and What the Future Holds.” *Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science*, vol. 61, no. 7, June 2020, iovs.arvojournals.org/article.aspx?articleid=2767477.

- Sommer, Alfred, et al. “Challenges of Ophthalmic Care in the Developing World.” *JAMA Ophthalmology*, vol. 132, no. 5, 1 May 2014, p. 640. [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, Aaron. “India - Urbanization 2023.” *Statista*, 13 Feb. 2025, www.statista.com/statistics/271312/urbanization-in-india/.

- De Souza, N., et al. “The Role of Optometrists in India: An Integral Part of an Eye Health Team.” *Indian Journal of Ophthalmology*, vol. 60, no. 5, Sept.–Oct. 2012, pp. 401–405, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3491265/. [CrossRef]

- Neena, J., et al. “Rapid Assessment of Avoidable Blindness in India.” *PLoS One*, vol. 3, no. 8, 6 Aug. 2008, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2478719/. [CrossRef]

- “About Common Eye Disorders and Diseases.” *Centers for Disease Control and Prevention*, www.cdc.gov/vision-health/about-eye-disorders/.

- Iqbal, Javed, et al. “Reimagining Healthcare: Unleashing the Power of Artificial Intelligence in Medicine.” *Cureus*, 4 Sept. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Con, D., van Langenberg, D., and Vasudevan, A. “Deep Learning vs Conventional Learning Algorithms for Clinical Prediction in Crohn’s Disease: A Proof-of-Concept Study.” *World Journal of Gastroenterology*, vol. 27, no. 38, 14 Oct. 2021, pp. 6476–6488, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8517788/. [CrossRef]

- Bhavsar, K., et al. “A Comprehensive Review on Medical Diagnosis Using Machine Learning.” *Computers, Materials and Continua*, vol. 67, no. 2, 1 Jan. 2021, pp. 1997–2014, zuscholars.zu.ac.ae/works/4101/. [CrossRef]

- Azuara-Blanco, A., et al. “The Accuracy of Accredited Glaucoma Optometrists in the Diagnosis and Treatment Recommendation for Glaucoma.” *British Journal of Ophthalmology*, vol. 91, no. 12, Dec. 2007, pp. 1639–1643, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2095552/.

- Xu, Wanni, et al. “ResNet and Its Application to Medical Image Processing: Research Progress and Challenges.” *Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine*, vol. 240, Oct. 2023, p. 107660. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).