1. Introduction

The introduction should briefly place the study in a broad context and highlight why it is important. It should define the purpose of the work and its significance. The current state of the research field should

Pulmonary embolism (PE) is a life-threatening cardiovascular emergency frequently encountered in the Emergency Department (ED), which is the third leading cause of cardiovascular mortality [

1]

. PE typically arises when a part of a thrombus from a deep vein in the lower extremities enters the pulmonary circulation and obstructs the pulmonary arteries. Rare PE occurs from embolizing other materials such as air, fat, or tumor cells [

2]

. Risk factors for PE are numerous but most commonly include prior venous thromboembolism, recent prolonged immobilization such as hospitalization, obesity, oral contraception, postpartum period, lower extremity surgery, malignancy, and thrombophilias [

3]

. The clinical presentation of PE can be highly variable and nonspecific, resulting from a complex interplay of different organ systems, which range from mild dyspnea to catastrophic hemodynamic collapse [

4]

. This wide variation in presentation makes early diagnosis particularly challenging. The diagnostic ambiguity often leads to both underdiagnosis, with potentially fatal outcomes, and over-testing, contributing to increased healthcare costs and resource strain, particularly in overcrowded EDs [

5]

.

Despite its high clinical burden, therapeutic advances have previously lagged compared to other cardiovascular emergencies, such as the first and second leading causes of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction and stroke, respectively. Historically, treatment has been limited to anticoagulation alone or systemic thrombolytic therapy for life-threatening PE. However, a renewed interest in reducing the mortality and morbidity of PE is evidenced by novel therapies such as ultrasound-assisted catheter-directed thrombolysis (USCDT) and mechanical thrombectomy [

6].

This review seeks to discuss the different treatment modalities utilized in the ED to reduce mortality and morbidity in patients who present with PE and to further highlight the outcomes associated with such treatment modalities. Additionally, it will provide an overview of the integration of emerging interventional options into contemporary cardiovascular emergency care. Finally, we offer considerations for the future of PE management

2. Clinical Decision Rules in Pulmonary Embolism Diagnosis

The annual incidence rate of PE in the U.S. is approximately 1.15 cases per 1,000 persons, with PE accounting for about 0.16% of all emergency department visits, with the incidence rising every year [

7,

8]. With PE having an increased burden of morbidity and mortality worldwide, early identification of the severity of PE on initial presentation is vital to therapy-directed treatment options.

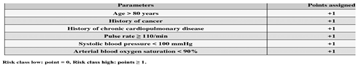

There have been several evidence-based clinical decision support systems (CDSS) that have been developed to assist in the determination of PE, including the Wells Criteria, Revised Geneva Score, and the Pulmonary Embolism Rule-Out Criteria (PERC) [

9]. The Wells score remains one of the most widely used tools, stratifying patients into low, intermediate, or high probability categories based on clinical criteria (

Table 1). When combined with D-dimer testing, the Wells score can safely rule out PE in many patients without requiring imaging [

10].

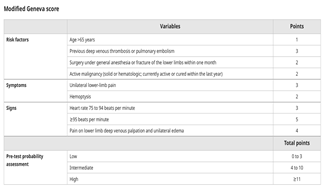

Similarly, the revised Geneva score is another scoring system in assisting with the pretest probability of PE, similar to the Wells score, however, relying purely on objective clinical variables (

Table 2) [

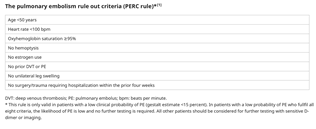

12]. In low-risk patients, pre-test probability (≤15%), the Pulmonary Embolism Rule-Out Criteria (PERC) can be employed to safely discharge patients without further testing if all criteria are negative (

Table 3) [

13,

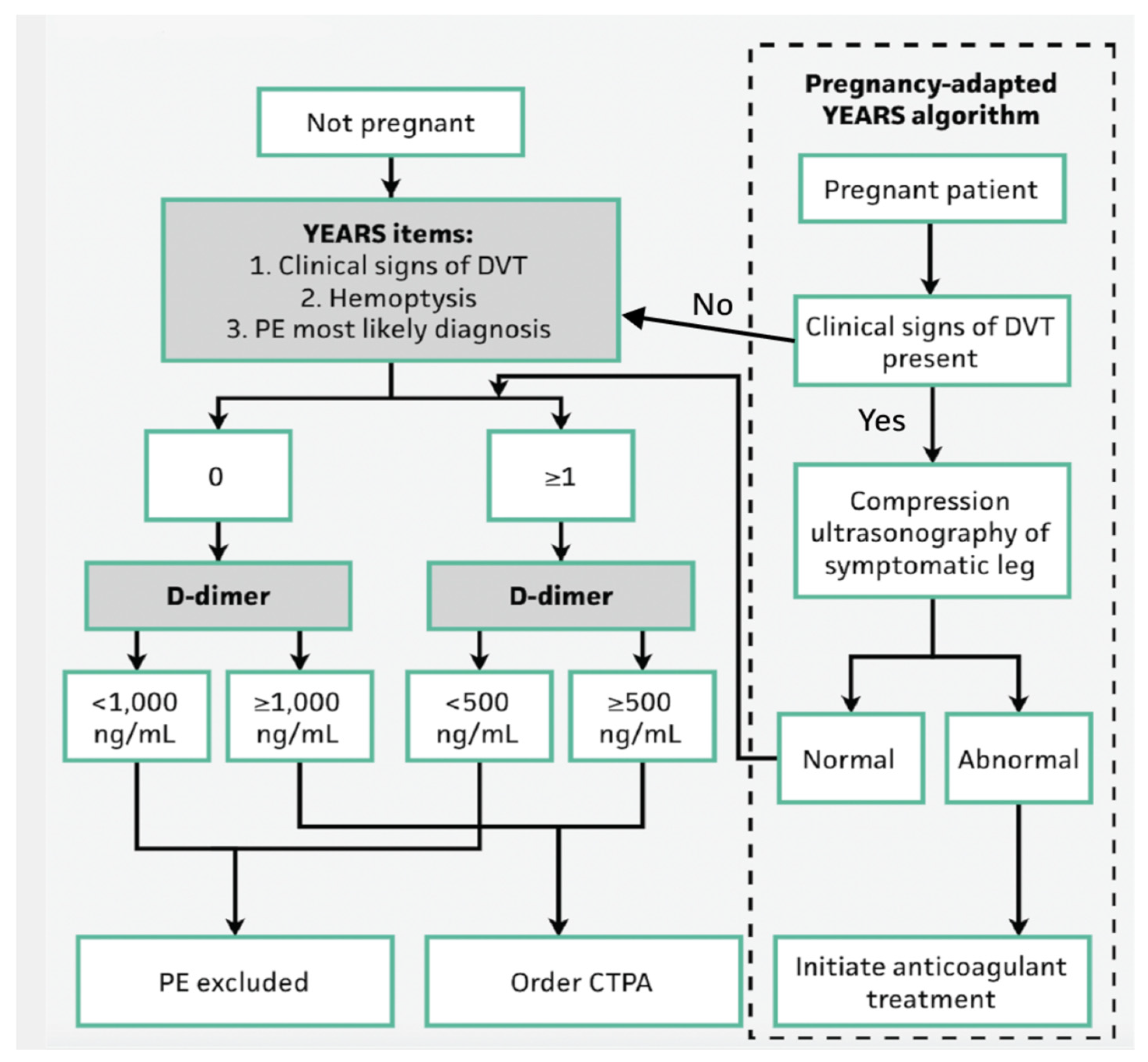

14]. More recently, the YEARS algorithm has been introduced, which reduces unnecessary imaging by adjusting D-dimer thresholds based on clinical suspicion and has been used in pregnant patients (

Figure 1). There have been studies to show that the YEARs criteria have shown superior efficacy compared to the previous Wells criteria [

15].

A D-dimer is traditionally ordered on low-risk patients, with a negative D-dimer can reasonably rule out a PE in low-risk patients. Patients in a high-risk category or who have a high clinical suspicion for PE should receive imaging instead of the D-dimer screening test. In moderate-risk patients, one can either obtain a D-dimer (a negative D-dimer would rule out PE) or go straight to imaging if clinical suspicion remains high [

19]. The CDSS, as described above, can also provide additional insight into when D-dimer screening tests should be implemented.

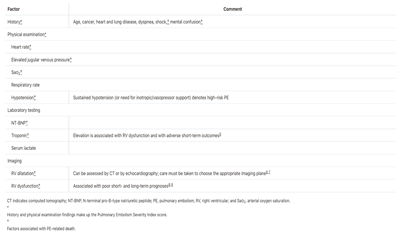

3. Risk Stratification

Once PE is suspected or identified, immediate risk stratification to guide treatment by identifying patients most likely to experience adverse outcomes. The most widely adopted classification systems for determining the severity of pulmonary embolism (PE) are those established by the American Heart Association (AHA) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) [

20,

21]. These two systems, which share many similarities, categorize PE severity into three primary levels: massive (high-risk), submassive (intermediate risk), and nonmassive (low risk) PE, and are based on hemodynamic effects and short-term prognosis (

Table 4). Management strategies are then decided upon, tailored to the severity of PE based on risk and benefits to best decrease mortality and morbidity in patients.

Massive PE traditionally has been defined by the basis of angiographic burden of the emboli by use of the Miller index however, most registry data now support the presence of circulatory arrest or hypotension are associated with increased mortality in acute PE [

21,

22]. Further definition of hypotension can be described as

a systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg, a drop of >40 mm Hg for at least 15 minutes (this latter criterion may be difficult to ascertain in some clinical circumstances), or need for vasopressor support, which identifies these patients [

22]

. These patients have approximately 65% 30-day mortality [

23]

.

The AHA and ESC do differ on their definition of submassive PE with the AHA stating that submassive PE typically is normotensive with evidence of right ventricular (RV) strain or myocardial ischemia (MI). The ECS has a broader definition that also incorporates the use of the simplified Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index (sPESI) for PE-related 30-day mortality (

Table 5). Patients with a score of 1 or greater are then subdivided into two subgroups according to whether the patients have both RV dysfunction and RV injury (intermediate risk-high) or only one of neither of these findings (intermediate risk-low) [

21]. RV strain does encompass RV dysfunction as evidenced on transthoracic echocardiography (TTE), RV dilation (RV/LV ratio .0.9) via contrast topography (CT) or TTE, and RV pressure overload and injury secondary to elevated biomarkers such as biomarkers such as troponin and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) [

21,

22,

23]. Clot burden viewed on CT scan does not predict overall mortality in patients with submassive PE. MI is often assessed by an electrocardiogram (ECG). This group of patients accounts for approximately 35-55% of hospitalized patients [

21].

Nonmassive PE is defined as patients with PE who do not meet the criteria for massive or submassive PE. This group of patients accounts for approximately 40-60% of hospitalized patients with PE and has an average mortality of approximately 1% in one month [

26].

Though there are limitations to risk stratification, such as PE severity varying over time with unique patient presentations and histories, it is a useful tool that has been validated by multiple studies [

20,

21]. Additionally, risk stratification allows providers to decrease overall mortality and morbidity of PE in patients while also reducing the risk associated with different therapy modalities.

4. Clinical Treatments and Outcomes

Historically, PE has mainly been treated with anticoagulation (AC), mainly Heparin, however, there have been several novel treatment modalities created in recent years that have aimed at reducing the duration of anticoagulation needed and improving outcomes from sequelae of high-risk and intermediate risk PE. Current guidelines still recommend therapeutic anticoagulation with subcutaneous low molecular weight heparin (LMWH), intravenous or subcutaneous unfractionated heparin (UFH), weight-based subcutaneous UFG or subcutaneous fondaparinux should be administered to patients with confirmed PE and no contraindications to AC [

1]. Additionally, therapeutic anticoagulation should be given to patients during the diagnostic work-up with intermediate or high clinical probability of PE with no contraindications to AC [

1].

Management strategies have evolved to include a range of advanced interventional therapies such as systemic thrombolysis, catheter-directed thrombolysis (CDT), mechanical thrombectomy, and ultrasound-assisted thrombolysis (e.g., EKOS)[

27]. Patients with massive or submassive PE who have hemodynamic compromise and/or have cardiogenic shock may also benefit from additional techniques such as invasive hemodynamic support devices, such as extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) or isolated percutaneous RV support in conjunction with treatment modalities [

28,

29,

30].

CDT technique involves delivering thrombolytic agents directly to the clot through a multi-side hole infusion catheter, typically reserved for cases of massive or submassive PE where systemic thrombolysis may lead to increased risk of major and intracranial bleeding. By localizing the thrombolytic action, CDT offers an advantage in terms of reducing the systemic bleeding risk. CDL has reported a significantly lower total dose of approximately 25% of what is usually given systemically [

31].

Ultrasound-Assisted Thrombolysis (USAT) with the EKOsonic endovascular system (EKOS Corp, Bothell, WA) combines the use of low-frequency ultrasound waves with thrombolytic agents, which enhances the ability of the clot-dissolving drugs to penetrate the thrombus [

32]. The EKOS catheter has two lumens, with one lumen holding a filament with multiple ultrasound transducers that emit high-frequency, low-energy ultrasound. The second lumen releases local thrombolytic delivery through multiple ports along the length. The low-energy ultrasound breaks down fibrin strands, leading to a more effective thrombolysis at lower doses. The biggest difference and proposed benefit of EKOS vs CDT is more effective penetration of thrombolytic agent over a shorter duration of time [

33]. Though there has not been a randomized control study to support this benefit [

34]. Ultrasound-assisted thrombolysis is often used for patients with intermediate-risk PE, offering a less invasive alternative to mechanical thrombectomy or systemic thrombolysis.

Mechanical thrombectomy or embolectomy is becoming increasingly recognized as a viable option for patients with massive PE. There are several different types of catheters and techniques used; however, the general idea is that mechanical thrombectomy physically removes the embolus using specialized devices, improving both right ventricular function and overall hemodynamic stability [

35]. Usually, a pre-procedural CT scan is ordered, which assists in guiding the catheter. This treatment is often used in combination with other therapies, such as CDT, in severe cases [

21].

Systemic Thrombolysis therapy remains a cornerstone for high-risk PE management, particularly in cases of massive PE with hemodynamic compromise. These medications actively promote clot degradation and reduce right heart strain [

36]. While this approach has a proven benefit in reducing mortality and improving clinical outcomes, it carries a significant risk of bleeding, particularly in patients with contraindications, such as active bleeding or recent surgery [

37].

Ultimately, treatment decisions should involve a multidisciplinary approach, with patient history and objective information contributing to the overall decision for treatment of PE. By focusing on individualized care, physicians can minimize complications while improving the chances of recovery and reducing mortality in patients with pulmonary embolism.

5. Patient Outcomes

Pulmonary embolism management has evolved significantly, with a strong emphasis on early diagnosis, risk stratification, and individualized treatment approaches. The variety of treatment modalities, including systemic thrombolysis, CDT, mechanical thrombectomy, and USAT, has allowed for more tailored care aimed at improving outcomes, minimizing complications, and preventing long-term sequelae like chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) or recurrent PE from deep venous thromboembolism (DVT).

High-risk patients may benefit from prompt, aggressive interventions such as systemic thrombolysis or mechanical thrombectomy, which can dramatically reduce mortality by rapidly reversing hemodynamic compromise compared to just AC if implemented early [

37]. However, the bleeding risks associated with systemic thrombolysis, especially intracranial hemorrhage, necessitate careful patient selection.

Intermediate-risk patients, the goal is often to avert hemodynamic collapse and death resulting from progressive right-sided heart failure. This group can benefit from catheter-directed therapies, including USAT, which deliver lower doses of thrombolytics directly to the clot. This approach improves right ventricular function and reduces clot burden with fewer bleeding complications compared to systemic thrombolysis.

Low-risk PE patients typically achieve excellent outcomes with anticoagulation alone, and many can even be safely managed as outpatients [

38]. This patient-centered approach minimizes hospitalization, reduces costs, and maintains high safety profiles.

Another goal of modern PE management is the prevention of CTEPH, a debilitating long-term complication of unresolved PE characterized by persistent pulmonary artery obstruction and pulmonary hypertension, prevention of recurrent PE, and reintroduction of exercise. Early and effective clot resolution is key to minimizing these risks. Permanent or temporary Inferior Vena Cava (IVC) filters are also a treatment modality utilized in recent years for the prevention of recurrent PE in patients with known DVT where systemic AC is contraindicated [

39,

40,

41].

Furthermore, the CDSS such as the PERC rule, Wells score, and the YEARS algorithm assist in identifying patients who can avoid unnecessary imaging or treatment, thus sparing them from potential procedural risks and radiation exposure.

The precision in risk stratification, ensuring the right therapy is used for the right patient at the right time, enhances survival and significantly reduces the occurrence of treatment-related complications.

6. Future of PE Risk Stratification and Therapeutic Modalities

One major future direction is the continued refinement of risk stratification models. Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning algorithms are beginning to play a role in predicting PE risk, which could include a more accurate risk stratification system, determining severity, and guiding diagnostic and therapeutic decisions. Future studies are needed to identify where risk stratification can be improved upon and how to better categorize treatment plans for patients to reduce mortality and morbidity [

42].

As data continue to support the safety and effectiveness of catheter-directed thrombolysis and mechanical thrombectomy, these modalities are expected to become the standard of care for intermediate-risk PE. Future devices may offer even more precise clot targeting, improved ease of use, and further reduced doses of thrombolytic agents. Combination strategies, such as low-dose systemic thrombolysis followed by catheter-based clot disruption, are being explored to optimize outcomes while preserving safety.

Additional studies are also needed to determine the benefit of USAT and CDT in patients with high-risk or intermediate-risk PE to create a unified guideline and reduce the risk of sequelae or side effects of therapeutic modalities.

7. Conclusion

PE is a cardiovascular emergency that remains a significant mortality in patients who present to the ED. To reduce the risk of mortality and optimize patient outcomes, PE requires prompt diagnosis, accurate risk stratification, and tailored therapeutic strategies. PE has a wide variety of presentations, ranging from sudden cardiac death to asymptomatic, making it a difficult diagnosis to determine with just clinical gestalt. Clinical decision tools such as the Wells score, revised Geneva score, PERC, and the YEARS algorithm have become regular practice in improving diagnostic efficiency while minimizing unnecessary testing. Risk stratification not only guides immediate management but also determines long-term prognosis. This allows physicians to select appropriate therapies, from AC to advanced interventions like CDT, mechanical thrombectomy, and USAT.

Advancements in treatment modalities have significantly improved survival and reduced morbidity, especially through individualized care approaches that balance efficacy with the minimization of bleeding risks. Modern management strategies have also placed a new emphasis on the prevention of CTEPH, recurrent PE, and earlier initiation of exercise therapy.

Looking forward, the future of PE management lies in further studies exploring more accurate risk stratification and in the expanding role of CDT, USAT, and developing safer pharmacologic agents. By continuing to evolve in response to emerging technologies and research, emergency medicine physicians and interventional cardiologists will be increasingly equipped to provide the right care for the right patient at the right time, ultimately reducing mortality and improving quality of life for patients with pulmonary embolism.

Funding

This research received no external funding

References

- Giri, J., Sista, A. K., Weinberg, I., Kearon, C., Kumbhani, D. J., Desai, N. D., Piazza, G., Gladwin, M. T., Chatterjee, S., Kobayashi, T., Kabrhel, C., & Barnes, G. D. (2019). Interventional Therapies for Acute Pulmonary Embolism: Current Status and Principles for the Development of Novel Evidence: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation, 140(20), e774–e801. [CrossRef]

- Vyas V, Sankari A, Goyal A. Acute Pulmonary Embolism. [Updated 2024 Dec 11]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560551/.

- Westafer, L. M., Long, B., & Gottlieb, M. (2023). Managing Pulmonary Embolism. Annals of emergency medicine, 82(3), 394–402. [CrossRef]

- Morrone, D., & Morrone, V. (2018). Acute Pulmonary Embolism: Focus on the Clinical Picture. Korean circulation journal, 48(5), 365–381. [CrossRef]

- Monteleone, P., Lou, Y., Klein, A. J., Maholic, R. L., Hollenbeck, S. T., & Lilly, S. M. (2024). Modern treatment of pulmonary embolism (USCDT vs MT): Results from a real-world, big data analysis (REAL-PE). Journal of the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions, 3(1), 101192. [CrossRef]

- Kline, J.A. ∙ Garrett, J.S. ∙ Sarmiento, E.J. ∙ et al. Over-testing for suspected pulmonary embolism in American emergency departments: the continuing epidemic. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2020; 13, e005753.

- Gottlieb, M., Moyer, E., & Bernard, K. (2024). Epidemiology of pulmonary embolism diagnosis and management among United States emergency departments over an eight-year period. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 85, 158–162. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, S. H., Ko, C. H., Chou, E. H., Herrala, J., Lu, T. C., Wang, C. H., Chang, W. T., Huang, C. H., & Tsai, C. L. (2023). Pulmonary embolism in United States emergency departments, 2010-2018. Scientific reports, 13(1), 9070. [CrossRef]

- Medson, K., Yu, J., Liwenborg, L., Lindholm, P., & Westerlund, E. (2022). Comparing ‘clinical hunch’ against clinical decision support systems (PERC rule, wells score, revised Geneva score and YEARS criteria) in the diagnosis of acute pulmonary embolism. BMC pulmonary medicine, 22(1), 432. [CrossRef]

- UpToDate. (n.d.). Pulmonary embolism: Clinical presentation and diagnosis. Retrieved April 26, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/pulmonary-embolism-clinical-presentation-and-diagnosis.

- Elsevier. (n.d.). Wells score. ScienceDirect. Retrieved April 26, 2025, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/wells-score.

- Elsevier. (n.d.). Geneva score. ScienceDirect Topics. Retrieved April 26, 2025, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/geneva-score.

- Evidence review for the use of the pulmonary embolism rule-out criteria for diagnosis of pulmonary embolism: Venous thromboembolic diseases: diagnosis, management and thrombophilia testing: Evidence review B. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2020 Mar. (NICE Guideline, No. 158.) Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK556663/.

- Jones, N. R., & Round, T. (2021). Venous thromboembolism management and the new NICE guidance: what the busy GP needs to know. The British journal of general practice : the journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 71(709), 379–380. [CrossRef]

- Stals MAM, Takada T, Kraaijpoel N, et al. Safety and efficiency of diagnostic strategies for ruling out pulmonary embolism in clinically relevant patient subgroups: a systematic review and individual-patient data meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2022;175:244–55. 10.7326/M21-2625.

- UpToDate. (n.d.). Pulmonary embolism: Clinical presentation and diagnosis. Retrieved April 26, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/image?imageKey=PULM/94941.

- UpToDate. (n.d.). Pulmonary embolism: Clinical presentation and diagnosis. Retrieved April 26, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/image?imageKey=PULM/120704.

- Kearon, C., de Wit, K., Parpia, S., Schulman, S., Afilalo, M., Hirsch, A., Spencer, F. A., Sharma, S., D’Aragon, F., Deshaies, J.-F., Le Gal, G., & Rodger, M. A. (2019). Diagnosis of pulmonary embolism with D-dimer adjusted to clinical probability. New England Journal of Medicine, 381(22), 2125–2134. [CrossRef]

- Bounds EJ, Kok SJ. D Dimer. [Updated 2023 Aug 31]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK431064/.

- Konstantinides SV. 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:3145–3146. [CrossRef]

- Jaff MR, McMurtry MS, Archer SL, Cushman M, Goldenberg N, Goldhaber SZ, Jenkins JS, Kline JA, Michaels AD, Thistlethwaite P, Vedantham S, White RJ, Zierler BK; on behalf of the American Heart Association Council on Cardiopulmonary, Critical Care, Perioperative and Resuscitation; American Heart Association Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease; American Heart Association Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology. Management of massive and submassive pulmonary embolism, iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis, and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association [published corrections appear in Circulation. 2012;125:e496 and Circulation. 2012;126:e495]. Circulation. 2011;123:1788–1830. [CrossRef]

- Miller, G. A., Sutton, G. C., Kerr, I. H., Gibson, R. V., & Honey, M. (1971). Comparison of streptokinase and heparin in treatment of isolated acute massive pulmonary embolism. British medical journal, 2(5763), 681–684. [CrossRef]

- Russell, C., Keshavamurthy, S., & Saha, S. (2022). Classification and Stratification of Pulmonary Embolisms. The International journal of angiology : official publication of the International College of Angiology, Inc, 31(3), 162–165. [CrossRef]

- Frémont B, Pacouret G, Jacobi D, Puglisi R, Charbonnier B, de Labriolle A. Prognostic value of echocardiographic right/left ventricular end-diastolic diameter ratio in patients with acute pulmonary embolism: results from a monocenter registry of 1,416 patients. Chest. 2008;133:358–362. [CrossRef]

- Meinel FG, Nance JW, Schoepf UJ, Hoffmann VS, Thierfelder KM, Costello P, Goldhaber SZ, Bamberg F. Predictive value of computed tomography in acute pulmonary embolism: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2015;128:747–59.e2. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez D, Kopecna D, Tapson V, Briese B, Schreiber D, Lobo JL, Monreal M, Aujesky D, Sanchez O, Meyer G, Konstantinides S, Yusen RD; PROTECT Investigators. Derivation and validation of multimarker prognostication for normotensive patients with acute symptomatic pulmonary embolism. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:718–726. [CrossRef]

- Bock, J. S. (2023). Treating pulmonary embolism with the EKOS™ endovascular system: A clinician’s perspective. Endovascular Today. Retrieved from https://evtoday.com/articles/2023-sept/treating-pulmonary-embolism-with-the-ekos-endovascular-system-a-clinicians-perspective.

- Elder, M., Blank, N., Shemesh, A., Pahuja, M., Kaki, A., Mohamad, T., Schreiber, T., & Giri, J. (2018). Mechanical Circulatory Support for High-Risk Pulmonary Embolism. Interventional cardiology clinics, 7(1), 119–128. [CrossRef]

- Ain, D. L., Albaghdadi, M., Giri, J., Abtahian, F., Jaff, M. R., Rosenfield, K., Roy, N., Villavicencio-Theoduloz, M., Sundt, T., & Weinberg, I. (2018). Extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation and outcomes in massive pulmonary embolism: Two eras at an urban tertiary care hospital. Vascular medicine (London, England), 23(1), 60–64. [CrossRef]

- DeFilippis, E. M., Topkara, V. K., Kirtane, A. J., Takeda, K., Naka, Y., & Garan, A. R. (2022). Mechanical Circulatory Support for Right Ventricular Failure. Cardiac failure review, 8, e14. [CrossRef]

- Kucher N, Boekstegers P, Müller OJ, Kupatt C, Beyer-Westendorf J, Heitzer T, Tebbe U, Horstkotte J, Müller R, Blessing E, Greif M, Lange P, Hoffmann RT, Werth S, Barmeyer A, Härtel D, Grünwald H, Empen K, Baumgartner I. Randomized, controlled trial of ultrasound-assisted catheter-directed thrombolysis for acute intermediate-risk pulmonary embolism. Circulation. 2014;129:479–486. [CrossRef]

- Boston Scientific. (n.d.). EKOS™ Endovascular System. Retrieved April 26, 2025, from https://www.bostonscientific.com/en-US/medical-specialties/vascular-surgery/ekos-endovascular-system.html.

- Piazza, G., Hohlfelder, B., Jaff, M. R., Ouriel, K., Engelhardt, T. C., Sterling, K. M., Jones, N. J., Gurley, J. C., Bhatheja, R., Kennedy, R. J., Goswami, N., Natarajan, K., Rundback, J., Sadiq, I. R., Liu, S. K., Bhalla, N., Raja, M. L., Weinstock, B. S., Cynamon, J., Elmasri, F. F., … SEATTLE II Investigators (2015). A Prospective, Single-Arm, Multicenter Trial of Ultrasound-Facilitated, Catheter-Directed, Low-Dose Fibrinolysis for Acute Massive and Submassive Pulmonary Embolism: The SEATTLE II Study. JACC. Cardiovascular interventions, 8(10), 1382–1392. [CrossRef]

- Lin, P. H., Annambhotla, S., Bechara, C. F., Athamneh, H., Weakley, S. M., Kobayashi, K., & Kougias, P. (2009). Comparison of percutaneous ultrasound-accelerated thrombolysis versus catheter-directed thrombolysis in patients with acute massive pulmonary embolism. Vascular, 17 Suppl 3, S137–S147. [CrossRef]

- Lauder, L., Pérez Navarro, P., Götzinger, F., Ewen, S., Al Ghorani, H., Haring, B., Lepper, P. M., Kulenthiran, S., Böhm, M., Link, A., Scheller, B., & Mahfoud, F. (2023). Mechanical thrombectomy in intermediate- and high-risk acute pulmonary embolism: hemodynamic outcomes at three months. Respiratory research, 24(1), 257. [CrossRef]

- Goldhaber SZ, Come PC, Lee RT, Braunwald E, Parker JA, Haire WD, Feldstein ML, Miller M, Toltzis R, Smith JL, Taveira da Silva AM, Mogtader A, McDonough TJ. Alteplase versus heparin in acute pulmonary embolism: randomised trial assessing right-ventricular function and pulmonary perfusion. Lancet. 1993; 341: 507–511.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2015, February 13). Activase (alteplase) prescribing information. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/103172s5203lbl.pdf.

- Aujesky, D., Roy, P. M., Verschuren, F., Righini, M., Osterwalder, J., Egloff, M., Renaud, B., Verhamme, P., Stone, R. A., Legall, C., Sanchez, O., Pugh, N. A., N’gako, A., Cornuz, J., Hugli, O., Beer, H. J., Perrier, A., Fine, M. J., & Yealy, D. M. (2011). Outpatient versus inpatient treatment for patients with acute pulmonary embolism: an international, open-label, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet (London, England), 378(9785), 41–48. [CrossRef]

- Stein PD, Kayali F, Olson RE. Twenty-one-year trends in the use of inferior vena cava filters. Arch Intern Med. 2004; 164: 1541–1545.

- Jaff MR, Goldhaber SZ, Tapson VF. High utilization rate of vena cava filters in deep vein thrombosis. Thromb Haemost. 2005; 93: 1117–1119.

- Muneeb A, Dhamoon AS. Inferior Vena Cava Filter. [Updated 2023 Aug 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549900/.

- Franchin, L., & Iannaccone, M. (2025). Limitations and Future Perspectives on Pulmonary Embolism: So Far, So Good. Interventional cardiology (London, England), 20, e11. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).