1. A Brief Concerning ψ10

First of all, the idea of the

symbol set, first treated well in a paper on the general theory of number cardinality [

1], is again re-introduced and given further treatment in another paper by the same author, on manipulating numbers in Base-36 [

2] — esp. for information mining purposes.

In particular, as explained in [

2], any number

N, when expressed in some base

—also denoted as base-

, shall essentially consist of a basic string concatenation of its elements picked from the symbol set of that base,

.

For the case of base-10, we know that the symbol set for that base, expressed as

[

1,

2], is the set

defined as such:

Definition 1 (Defining ). For any number base-10,

.

2. Clearing Up the Symbol Set Nomenclature

Note that, unlike in the original GTNC paper that first introduced the useful terminology and mechanics of the specific and implicit symbol sets [

1] among other useful and related concepts, in this paper — and definitely moving forward, we shall further differentiate between these fundamental concepts as such:

Definition 2 (Defining : the Ordered Symbol Set of Base-: the Base Symbol Set). For any base , its Ordered Symbol Set, denoted as , is the ordered set of distinct symbols — also conventionally referred to as ‘digits’ in that base, that has the following properties:

-

can be expressed as , where or as

— which means, the numerical value or magnitude of any symbol, digit or element in is related to and derived from its relative position, i, within the ordered symbol set of the base [2] Consequently, and that generally, and that, for any two elements and from ; .

Because the elements in any Base Symbol Set or rather, Ordered Symbol Set of base-β are already in their natural order by relative quantity and position, we might correctly, and conveniently so, refer to as the Natural Symbol Set of Base-.

Thus, we expect to be expressed as the ordered set and not as or any other such dis-orderly collection of the cardinal digits of base-10.

Similarly, for Base-2, we should expect to be or , and not say , even though both set expressions contain the same exact elements and fully enumerate all the valid digits allowed for a number in that base.

Concerning Notation:

Note that, the choice to express and other ordered sets within this paper using the notation and not is especially in keeping with the modern conventions and notations in most fields across the mathematical society. Otherwise, it might still be forgivable, and acceptable to stick with the traditional notation where the semantics are obvious or the intentions clear enough to prevent ambiguity or confusion. In this paper, sometimes we might prefer to write such ordered sets using the traditional notation so as to avoid confusion or unnecessary complexity, or might use the two notations for ordered sets interchangeably where it doesn’t create any confusion or where the ordering is of secondary importance when compared to the set’s membership.

Talking of which, we also need to clarify concerning symbol sets for particular and generic numbers in any base.

Definition 3 (Defining : Specific Symbol Set of P in Any Base-). For any number P in any base-β — also written as , the Specific Symbol Set of that number in base-β, written as shall be understood to mean the ordered set of all, and only those digits/elements from , that are present in the number P and which are necessary in fully expressing that number in its standard and/or [expanded] sigma form, in their particular order of [first] occurrence within the number or numeric expression of .

By Definition 3, we then can safely trust that when we speak of the specific symbol set of a number, we mean the set representing and preserving the order in which the individual distinct digits within that number occur within the number, and not just any other or potential symbol set for the number — which for example might still contain the same exact elements, such as for the number “2025" instead of the correct .

However, note that, because of Definition 3, if we had a NE such as “2025", and tried to compute its specific symbol set in base-3, i.e. , the correct value we would obtain is instead of that spans all the distinct digits in the number. This is because, is sensitive to both the base, as well as the number being processed.

That said, there might be legitimate scenarios in which one needs to compute an ordered symbol set true to the particular order of occurrence of the distinct digits in a numeric expression [

3] or number sequence [

4], irrespective of the base to which the number might belong. For such a special case then, we shall need

Unspecific Symbol Set, which we then define as as such:

Definition 4 (Defining : Unspecific Symbol Set of in Any Base). For any number ρ in any base, the Unspecific Symbol Set of that number irrespective of the base, written as shall be understood to mean the ordered set of all, and only those digits that are present in the number ρ and which are necessary in fully expressing that number in its standard and/or [expanded] sigma form, in their particular order of [first] occurrence within the number or numeric expression of ρ.

With this definition then, revisiting our earlier examples, we shall find that:

Given , then .

Given , then .

But, given , then , , while .

So, it is important to beware of when we wish to restrict the symbol set of a number by the base it belongs to or a base of interest, and when we only care about the elements in the number irrespective of the base or their relative quantities. Also, as a consequence of Definition 4 and Definition 3, we have the following interesting general fact:

Theorem 1 (Equivalence of and for Base-∞). For any number in any base-β s.t. , it is always true that .

Proof. Since cannot contain any digit such that , it follows that no matter what is equivalent to, . □

Talking of which, when we need to compute an ordered symbol set for a particular number relative to the base to which it belongs (and not relative to the order of occurrence of the digits within the number), then we shall likewise need the following definition:

Definition 5 (Defining : Natural Symbol Set of P in Base-). For any number , the Natural Symbol Set of that number in base-β, written as or even shall be understood to mean the ordered set of all, and only those digits/elements from , that are present in the number P and which are necessary in fully expressing that number in its standard and/or [expanded] sigma form, in their natural order of [first] occurrence within .

By Definition 5, we then know that when we speak of the natural symbol set of a number, we mean the set representing and preserving the order in which the individual distinct digits within that number occur within the ordered symbol set of the base from which the number occurs, and not just any other or potential symbol set for the number. Thus for example, for the number “2025", would qualify as the correct value of , but not or and neither would qualify, since it isn’t a proper set to begin with — it contains duplicated elements.

Definition 6 (Defining : Implicit Symbol Set of [in any base]). For any number ρ — in any base, the Implicit Symbol Set for the number, denoted as , is understood to be any valid symbol set [1] for the number ρ — in which case, the order of the elements in that set doesn’t matter, as long as the set contains all the distinct elements or digits that occur within the number ρ.

It makes sense, because, in the case of , as well as , we know the base, and so can likewise sort the unique elements of relative to their ranks, sizes or numeric-quantities as well as that of .

Lastly, when we talk of a symbol set, and especially when there is mention of the base, such as in , or , we shall naturally expect that there is some ordering to be done — or rather, that we are most likely dealing with an ordered set, and yet, when there is no mention of a base, such as in the case of the implicit symbol set of a number, , it shall be understood that even though the set might be written or presented with some particular ordering of the elements, the ordering doesn’t matter or isn’t of importance and all that matters is the composition of the set.

3. Using ψβ to Test Any Number for Membership in Base-β

Using the concept of the symbol set then, it should become very straightforward and simple to quickly check if any arbitrary number expression belongs to a particular base or not. For example, in case we had some three arbitrary numbers

,

and

, which, for simplicity’s sake, we might assume to be

pure numbers [

1], and which two numbers we might express as such

1:

while

First, we can note that, given any one of these numbers, , or , we can map it to the unique set of its constituent digits or elements, merely by computing its symbol set, especially one of the implicit, specific or natural symbol set.

For example, for

, we have that:

And like for the case of

in

Equation 4, since we know that

[

2], then we can likewise conclude that:

Which is a more succinct, more rigorous, GTNC-way of saying that

belongs to base-2 or rather, is a binary number [

1].

Finally, for the

queer , which we might consider to fall into the category of

random alphabetical expressions (RAE) given it is a NE in base-36 but without inclusion of any usual decimal digits (0-9), which is why we might also merely refer to it as an

alphabetical expression (AE) [

3]; we might likewise map this number to its symbol sets as such:

And further, by the

Specific Symbol Set of that number in base-36,

— refer to

Section 2, that:

So, if one were to pose the question: Which of the three numbers, , or belongs to base-10?, how might we proceed to systematically resolve that problem?

Well, given we have the basic analysis out of the way in the evaluations we’ve conducted from

Equation 4 to Equation 8, we can argue that:

Concerning

, it is clearly obvious from

Equation 4 that it is a decimal NE.

-

Concerning

, the result in

Equation 6 might convince us that

is a binary number, however, upon further analysis, one would also note that despite not containing all the elements of

, and yet it is true that by standard notations:

Which, together with other analyses we’ve seen in

Equation 5 would undoubtedly make it qualify as a true member of the base-10 family of NEs or rather decimal numbers to be more precise.

-

For , based on what we know of , we can safely argue that:

Since (by

Equation 7 and

Equation 8)

But also, even without assuming that

is a base-36 number, and merely going by the standard convention that any literal numbers expressed using letters in their standard-form (and even where such letters might be mere variables or placeholders for decimal values) are typically for digits greater than the decimal value “10" (see examples in [

2]), we might also plausibly argue that:

Which is proof enough that isn’t a base-10 number.

More generally though, we can conclude that for any arbitrary number, RNE or just NE, the following is true:

Theorem 2 (Membership in base-). For any number in some particular base-α, can be considered a number in base-β iff

A simpler way to interpret this theorem is that, despite being a base- number, it likewise qualifies to be considered a number in base-, simply if all elements present in that number also are present in . Moreover and/or additionally for as long as , irrespective of what or is, as long as we known that , then all digits present in the number shall likewise qualify to be members in and the specific symbol set of the number in base-, , and thus the number can be correctly considered to belong to base-.

Consequently, we also have that...

Lemma 1 (Disqualification from base-). For any number in any

And thus cannot be a number in base-β, irrespective of what α is.

It is interesting to note that, because of Lemma 1, even numbers such as our special case of that involved non-numeric digits (which could occur for numbers in bases greater than 10 in most standard notations), when we can quantify any such digits , by comparing them to the target base, , via their numerical magnitude , we then can leverage either of these two general results to determine if any arbitrary numbers (in any base) might belong to some particular base.

4. The Symbol Set Identity for Any Number P in Base-β

Before we dive into the meat of this paper, it shall be important to also formally introduce (actually, define for the first time), the useful concept of a Symbol Set Identity.

First, let us recall that for a number

— which is the way we write the number

P in base-

, we know that if

Moreover, and perhaps more generally, we can define the Symbol Set Identity for any base- as such:

Definition 7 (Symbol Set Identity). A number is called a Symbol Set Identity for the base-β iff .

It basically means, all the digits from the natural symbol set of the base are present in the number whether or not they occur multiple times or in arbitrary order within the number doesn’t matter. The most interestingly implications of Definition 7 is that for a base-, there is no guarantee that only 1 such number exists. In fact, any number P or for which , qualifies to be called a symbol set identity for base-.

However, and especially for the case of computer science [sub-]fields such as cryptography, data-mining, data-processing, information encoding, etc. where one might come across NE, RAE, RNE or RANE [

3] that might not readily qualify as

normal numbers in the sense they might be expressed in a manner that defies standard number notation in mathematics; for example, the binary NE ‘001’ or a hexadecimal ‘000001F180CC00’ might be deemed legitimate and with all expressed digits in either expressions being considered significant for some special protocol or number system, yet, under normal mathematical conventions, such as when we express numbers in their standard form, the trailing 0s would get stripped away, and thus these expressions would be treated as ‘1’ and ‘1F180CC00’ respectively — which might not be what was intended.

Thus, we need to further define the more restrictive Natural Symbol Set Identity (n-SSI) and Orthogonal Symbol Set Identity (o-SSI) for any Base- as such:

Definition 8 (Natural Symbol Set Identity). An expression Θ is called a Natural Symbol Set Identity for the base-β iff

,

where is the Cardinality of Θ.

It basically means, for any such expression

, when its natural and unspecific symbol set are computed (and/or if the expression itself is merely hewed and treated as the symbol set), we find that

An example of expressions that qualify to be n-SSI would be ‘01’ for base-2 and ‘0123456789’ for base-10, but not ‘001’ and neither ‘1234567890’ nor ‘012345678999’ — even though they are indeed symbol set identities for their respective bases mentioned!

And then, when we might only care that each element in exists in the number exactly once — the order not mattering, then we might consider such a number to be an Orthogonal Symbol Set Identity for the base. More precisely:

Definition 9 (Orthogonal Symbol Set Identity). An expression Θ is called an Orthogonal Symbol Set Identity for the base-β iff

.

Basically, that the expression contains the same exact elements as those in , both in quantity and quality, and nothing more — their ordering not of concern here. In this case, for base-2, the expressions ‘10’ and ‘01’ are both o-SSIs for that base, while the expressions ‘101’ and ‘1100’ wouldn’t qualify — despite being symbol set identities for base-2.

Further, note that sometimes, a number can both be an o-SSI as well as a n-SSI for a particular base. In fact, it is true that:

Theorem 3 (n-SSI is also o-SSI for any ). For any NE that is a n-SSI for base-β, it also is an o-SSI.

Proof. It follows from Definition 9 and Definition 8. □

Moreover...

Theorem 4 (n-SSI Are Unique for any Base-). For any given base, β, there is only one possible n-SSI.

Proof. From Definition 9 and Theorem 3, we know that for base- there could exist one or more distinct o-SSI, and that at least one of them is a n-SSI for the base. Assume is an o-SSI of base- that is also a n-SSI. Then, in case we assume that there exists some other distinct o-SSI, , such that it is also a n-SSI for base-, and yet , it would contradict Definition 8. □

Before we conclude this section, note that we can revisit the three numbers we analyzed in

Section 3 and say some new things about them based on what we now know, as such:

The number which was presented as ‘1234567890’ qualifies as a symbol set identity for base-10 (by Definition 7). It also qualifies as an o-SSI for the base.

The number which was presented as ‘10101010101010101010101010’ only qualifies to be considered a symbol set identity for base-2. It neither is a base-2 o-SSI nor n-SSI though — especially because of its size.

The number or expression defined as equivalent to ‘taz’ is not a symbol set identity for any base we’ve looked at or that we know (not even for base-36 for which it qualifies as a legit number).

5. The Strange Sum Made of 3 Orthogonal Symbol Set Identities of Base-10

First, note that the numbers we are going to look at were discovered rather accidentally while working on some empirical research problems in number theory and cryptography in relation to an original theory of random number generation that the author is currently working on. Without prematurely divulging the details of what that theory is about, it is worth noting that it concerns the use of certain permutations of NEs to obtain RNEs.

5.1. Two Distinct Addends That Are Almost Base-10 o-SSIs

“Although our pocket calculators express numbers in terms of only a finite number of digits, we readily accept that this is an approximation forced upon us by the fact that the calculator is a finite object.”

—

Prof. Roger Penrose, 2020 Physics Nobel Laureate in

The Road to Reality [

6]

That said, the numbers we are going to deal with start with two orthogonal symbol set identities for base-10 that can readily be obtained when all the digits of a typical standard arithmetic calculator’s number pad are selected, one at a time, in a certain special order, without repetition, as we are about to see.

First, with the exception of the digit ‘0’, consider the typical numeric pad of a standard calculator as shown in

Figure 1.

Next, notice that, for a standard (or perhaps traditional) calculator or numeric pad on a computer, with each key on the keyboard that we press, the corresponding digit as is associated with the key that was pressed gets to be printed on the screen somewhere.

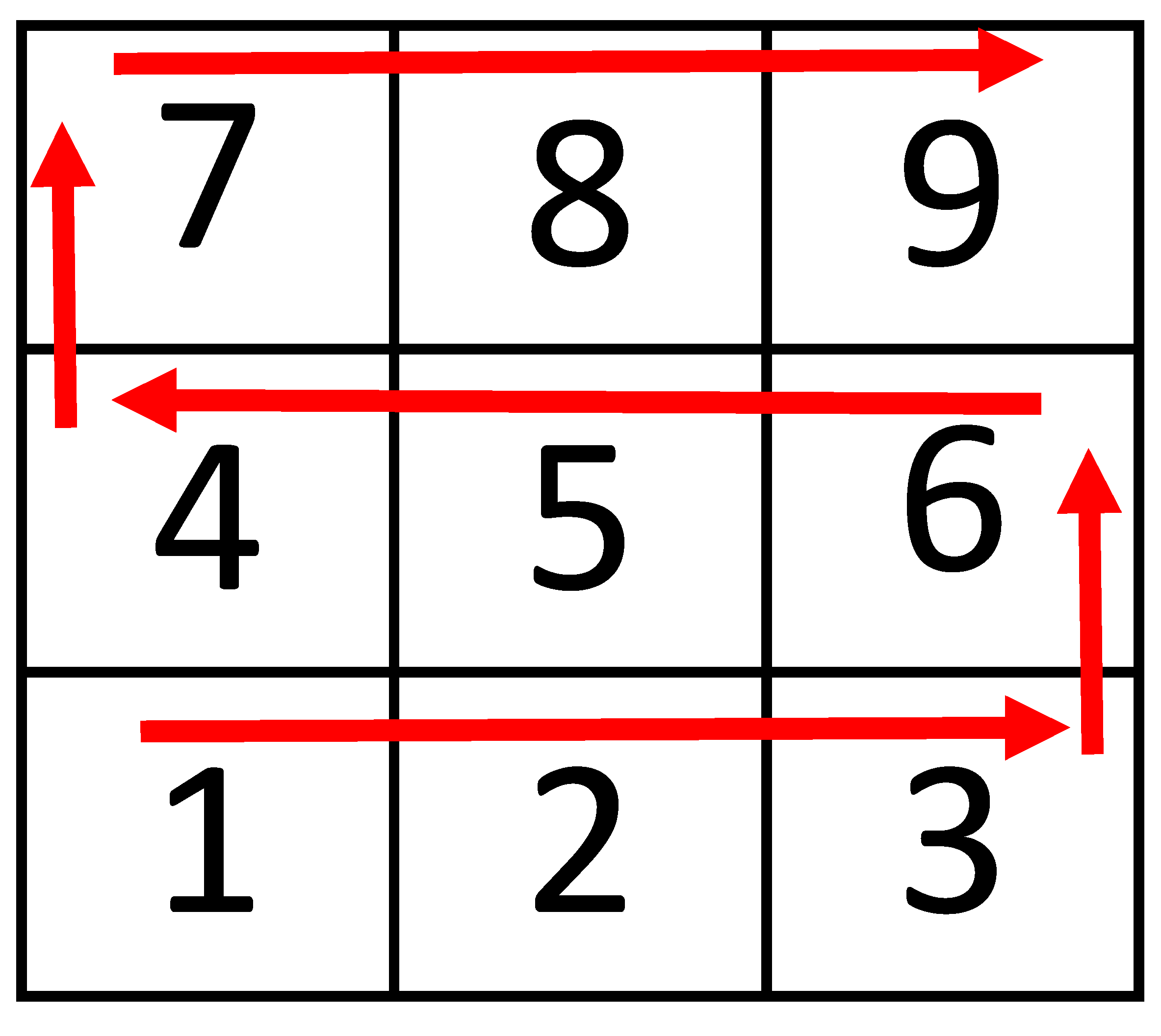

So, assuming we iterate through the digits on such a keypad, in a manner as shown in

Figure 2 — basically, we start at the bottom row; moving left-to-right, from digit ‘1’, then follow the red arrows from there through digits ‘2’, ‘3’, then up to next row without returning left, and then instead reverse the direction; through ‘6’, ‘5’, and then ‘4’; and then onto the last row at the top, moving left-to-right again, through ‘7’, ‘8’ and finally stopping at ‘9’. After that process, we shall then have obtained the NE with the value

‘123654789’. We shall refer to this number as

Addend-1.

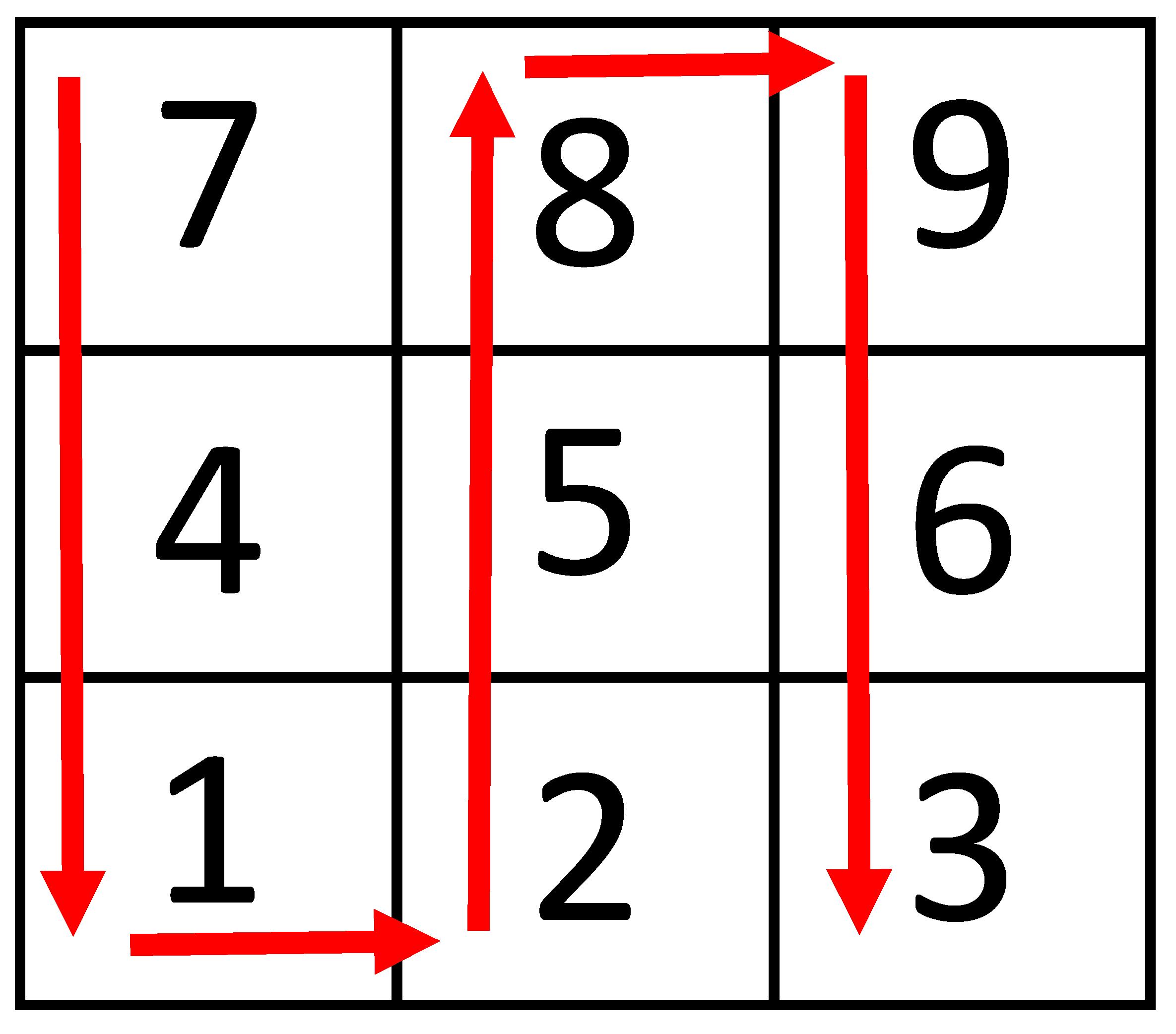

And then next, if we generate another number in a similar fashion, but instead following the number selection route shown in

Figure 3, we shall then arrive at the NE

‘741258963’. Let us refer to this other number as

Addend-2.

At this point, it might not yet seem that these two numbers we selected possess any ‘special’ or perhaps even magical properties, however, just to whet your appetite a bit, notice, first of all, that both numbers, when we add to them the extra missing base-10 digit — particularly, ‘0’, suddenly become valid base-10 orthogonal symbol set identities!

Extend Addend-1: 123654789 + suffix ‘0’ → 1236547890

Extend Addend-2: 741258963 + suffix ‘0’ → 7412589630

And then, notice what happens when we attempt to sum up our original, unmodified two special addends (as in normal addition of pure numbers):

So, in

Equation 18 we have essentially taken

Addend-1 and added to it the other special number,

Addend-2. As you can see, their sum is the number ‘864913752’, and in the next section we get to see how interesting this result is.

5.2. How Is This Possible: That Adding Two o-SSIs of Base-10 Produces an o-SSI of Base-10?

So, in

Section 5.1 we have seen that via a special [and undoubtedly accidental] process, we did arrive at some two near-o-SSIs; Addend-1 and Addend-2, which, after we adjusted them by also allowing for the extra/final missing digit from the complete base-10 digit keypad (or rather,

symbol set), turns our two addition operands into proper base-10 o-SSIs (refer to

Section 4).

Now, notice that with the two extended operands — or rather, addends (since this is an addition operation under investigation), we then arrive at the following really exciting result:

Truly spectacular!

This result is indeed interesting, because of the following interesting observations:

We summed two, distinct, particular or rather special base-10 o-SSIs (‘special’ because of the queer manner in which we arrived at their generation), and produced a new distinct base-10 o-SSI!

Interestingly, or perhaps, totally bonkers and hard-to-explain, no matter how much you try, following

alternative but similar base-10 o-SSI generation processes as we have introduced and illustrated in

Section 5.1, you might arrive at innumerable other, different, alternative base-10 o-SSIs that you might try to plug into

Equation 18 or

Equation 19, but

you shall not manage to reproduce that interesting resultany other way; two distinct base-10 o-SSI addends producing another base-10 o-SSI!

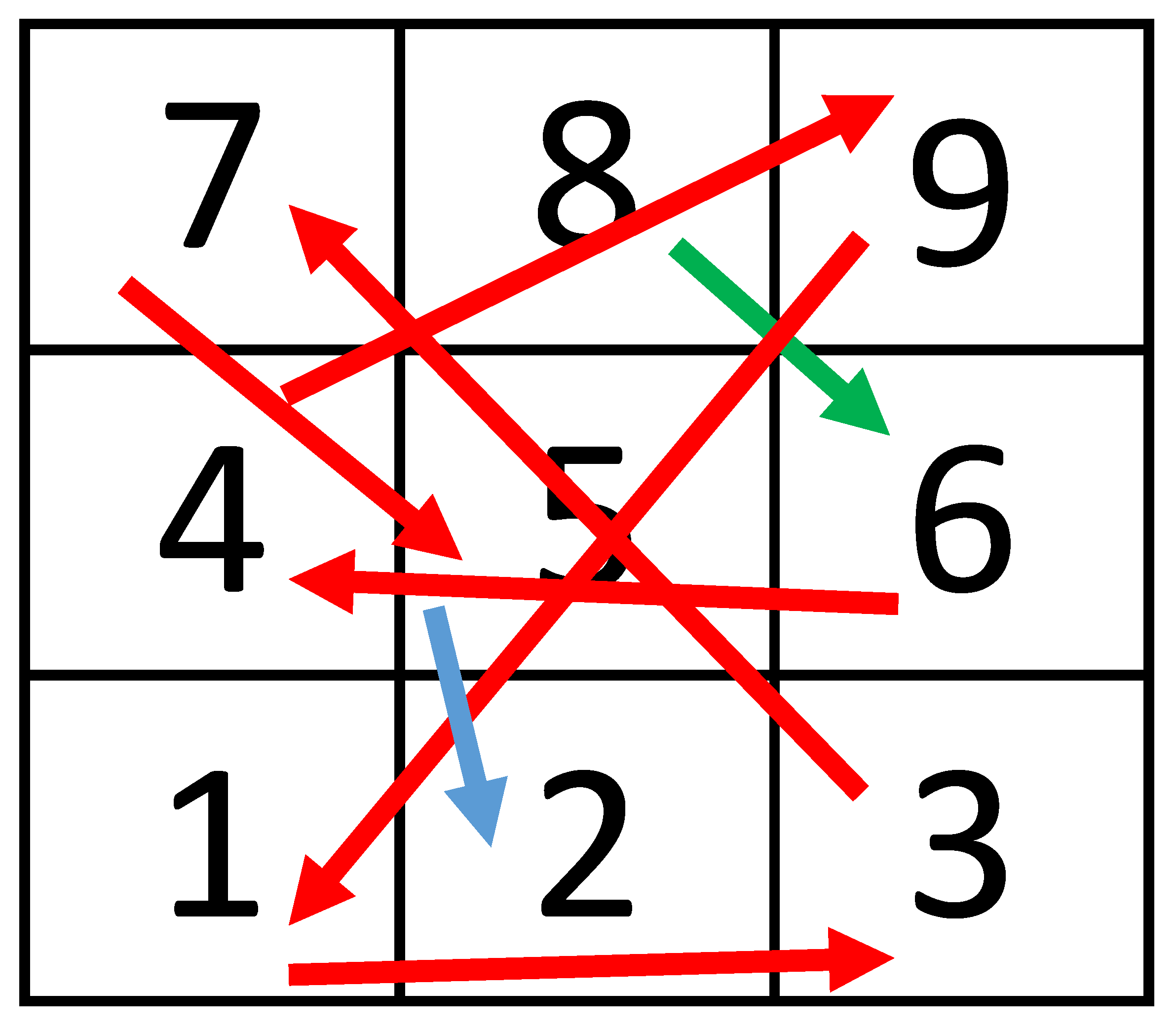

The rather stranger thing about this result is that, the new base-10 o-SSI that we generate via the sum, is not anything like the two addends we started with; in particular, when compared to the rather

clean and

systematic manner in which we arrived at the interesting two addends —

especially with their neat, meaningful ordering of the successive digits in the o-SSI, attempts to generate that summation result via the same method looks anything but total chaos (see

Figure 4), and thus, it must be really appreciated that there is or must be something special about the two input numbers or the process that led to them, so as to obtain the final base-10 o-SSI.

As expected, all three numbers (all of them base-10 o-SSI) we’ve produced (two, via the strange keypad iteration method, one via the summation of the other two thus generated numbers) are merely permutations of the unique, distinct, base-10 natural symbol set identity (the base-10 n-SSI) numeric expression ‘0123456789’.

Perhaps, and for completeness’s sake, it might be interesting to note that given this paper touched on and somewhat was inspired by a queer process of generating ‘special’ numbers (not just random as the author’s original and still ongoing enterprise is about), but also those possessing some useful or important properties; such as when particular prime numbers are used to generate other prime numbers — as well as other, such interesting manipulations of just numbers; which are undoubtedly important problems and operations in modern cryptography and several other fields of pure and applied mathematics to say the least, there’s another — different kind of — work by the author that might somewhat relate to what we’ve encountered here!

Talking of which, it is worth noting that about less than a month before this paper was written and before the present method of obtaining interesting numbers was discovered, the author happens to have completed writing and publicly releasing his second novel [

7], titled “ROCK ‘N’ DRAW", in which book of literally fiction — particularly in chapter 10, we interestingly come across the case of a modern medical doctor discussing with a certain young boy apprentice of his, concerning another

strange method of generating random numbers (and from these, non-numeric messages) using a 3×3 matrix of simple digits or numbers — somewhat similar to what we’ve just encountered here, as part of their ad-hoc, purely analog, ancient-computing method meant to “solve some mathematics problems" [

7] via number generation, decoding and analysis. Despite that novel not being about mathematics in particular — it might best be appreciated as a wartime science-fiction, anyone enjoying this present work by Joseph Willrich Lutalo, its author, might as well enjoy looking at that, as well as several other earlier works

2, but especially that particular small book (∼222 pages) from early 2025.

6. Conclusion

In this paper, we have re-iterated on and further developed as well as empirically applied the idea of the symbol set of an arbitrary base, as well as that of any arbitrary number. We have seen how useful the concepts of the specific, unspecific, natural and other kinds of symbol sets can be when analyzing arbitrary numbers for things like equivalence under some particular base, relevance as identifiers of any other number from the same base, as well as for their potential membership within one or more bases. Special treatment has been given to base-10, also the domain of decimal pure numbers, and we have seen how the concept of the symbol set can be extended to the concept of a symbol set identity for any base. We have arrived at some useful general results (4 theorems, 9 definitions and 1 lemma) concerning these concepts, and these could lend themselves readily to analyzing, interpreting and/or explaining old and new problems in number theory, cryptography, general computer science as well as several other fields as time and further exploration shall make clear. Most interestingly, in this paper we highlight a rather strange procedure by which two special base-10 orthogonal symbol set identities might be generated following a particular process based on a simple 3 x 3 matrix containing the distinct elements of

in a particular order — we’ve considered the natural ordering as found in traditional calculator keypads. We then see how, by adding these special base-10 o-SSIs thus generated, we strangely arrive at yet another base-10 o-SSI. Apart from inspiring others to take earlier work on the GTNC (General Theory of Number Cardinality) seriously, as well as exploit and leverage many of the interesting results that have issued from that original paper over the years (such as this paper), this particular paper likewise invites more research and experimentation concerning the concept of symbol sets, and in this particular case, that of symbol set identities such as the queer base-10 near-o-SSI and o-SSI we’ve generated in

Section 5.1 and

Section 5.2 respectively. Also, any problems we’ve thus raised warrant good answers as well as further exploration; like, if there might be any other summation operations other than the particular two we’ve seen in this paper, that could similarly operate on either an entirely different pair of base-10 o-SSI (and/or near-o-SSI) addends to produce [especially] other o-SSI, or which involve more than two such o-SSI addends and yet still produce a base-10 o-SSI. But also, other, similar problems via other [arithmetic] operations such as division or multiplication (since the particular case we’ve covered in this paper somewhat already caters for such a production via subtraction as well).

References

- Lutalo, J.W. A general theory of number cardinality. Academia.edu 2024. Accessible via https://www.academia.edu/43197243/A_General_Theory_of_Number_Cardinality.

- Lutalo, J.W. Numbers from Arbitrary Text: Mapping Human Readable Text to Numbers in Base-36. Academia.edu 2024. Accessible via https://www.academia.edu/123296302/Numbers_from_Arbitrary_Text_Mapping_Human_Readable_Text_to_Numbers_in_Base_36.

- Lutalo, J. Concerning A Transformative Power in Certain Symbols, Letters and Words. Preprints 2025. Accessible via. [CrossRef]

- Bikos, A.; Nastou, P.E.; Petroudis, G.; Stamatiou, Y.C. Random number generators: Principles and applications. Cryptography 2023, 7, 54. Accessible via https://www.mdpi.com/2410-387X/7/4/54. [CrossRef]

- Lutalo, J.W. TEA TAZ - Transforming Executable Alphabet A: to Z: COMMAND SPACE SPECIFICATION 2024. Accessible via. [CrossRef]

- Penrose, R. The Road to Reality: A Complete Guide to the Laws of the Universe; Jonathan Cape, 2004.

- Lutalo, J.W. Rock ‘N’ Draw; I*POW, 2025. ISBN 978-9913-624-71-8. A physical copy might be accessed via the National Library of Uganda (NLU), but also, an education-purposes-only edition is accessible freely via Academia at https://www.academia.edu/128601975/ROCK_N_DRAW_2025_. [CrossRef]

| 1 |

Not merely for creativity’s sake have the three numbers been chosen as such, but because these three chosen [somewhat random and/or arbitrary] numbers or rather numeric expressions(NE) [ 3] have relevance in the work that has inspired this paper. But also, they shall be useful to reference in the future. is just the elements of concatenated to each other (ref. Definition 1), with the exception that we move ‘0’ to the end so as to make that digit significant in the standard form of the NE [ 1]. The number has been sourced from a paper on RNGs [ 4], where it is used to illustrate important ideas concerning RNEs [ 3] or rather ‘random sequence of numbers’ or ‘random sequence of bits’ given that particular RNE is meant to depict a random binary number [ 4]. Then, the special number is sourced from a reader’s exercise in the author’s base-36 paper [ 2], and is an interesting exemplary number for those already familiar with that work as well as the author’s work on the TEA computer programming language [ 5]. |

| 2 |

JWL’s creative fiction works are mainly found on his Telegram Portfolio:

But as for esp. Scientific and Mathematical literature, visit the portfolio on Academia:

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).