Submitted:

28 April 2025

Posted:

28 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Single-Cell Transcriptomics: Technologies and Methodologies

2.1. Principles and Evolution of Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Technologies

2.2. Comparison of Major scRNA-seq Platforms and Their Features

2.3. Technology Selection Strategies and Application Cases in Spinal Cord Research

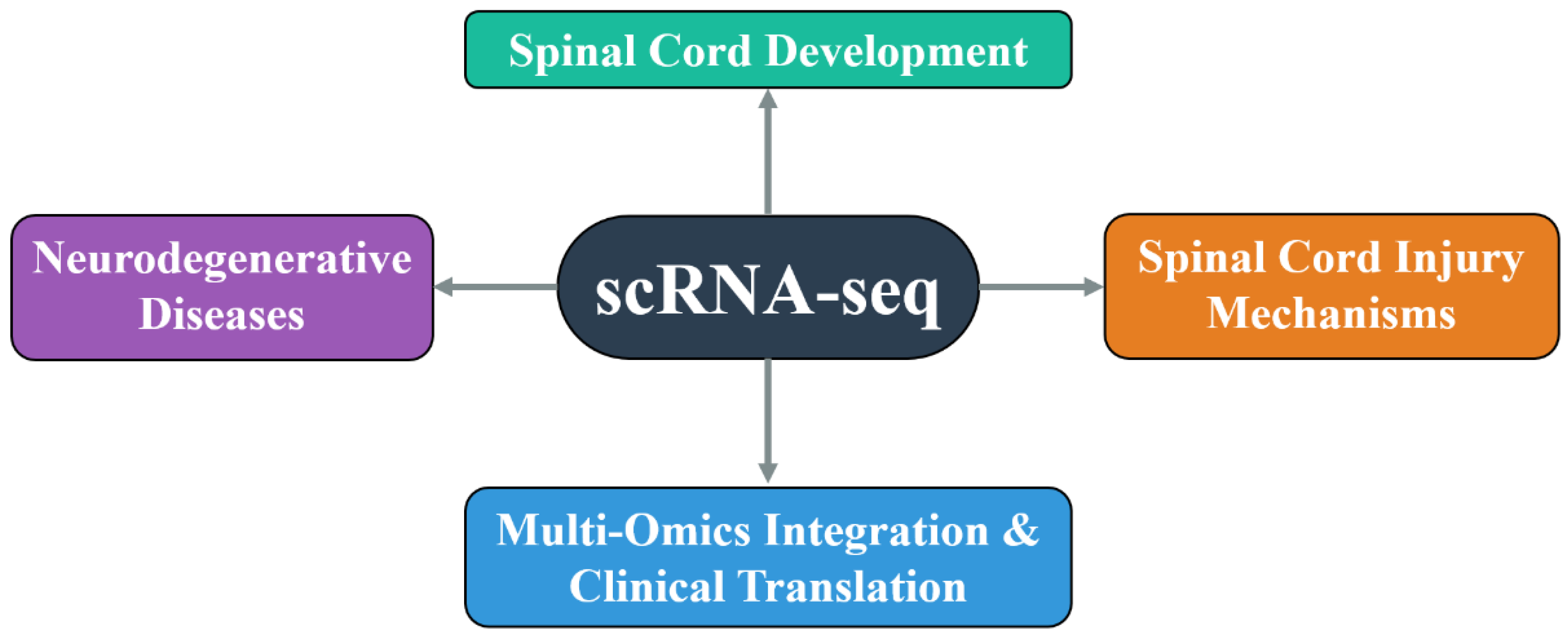

3. Applications of Single-Cell Transcriptomics in Spinal Cord Research

3.1. Decoding Spinal Cord Developmental Biology

3.2. Investigating Spinal Cord Injury and Neurodegeneration

3.3. Spatial Transcriptomics and Multi-Omics Integration

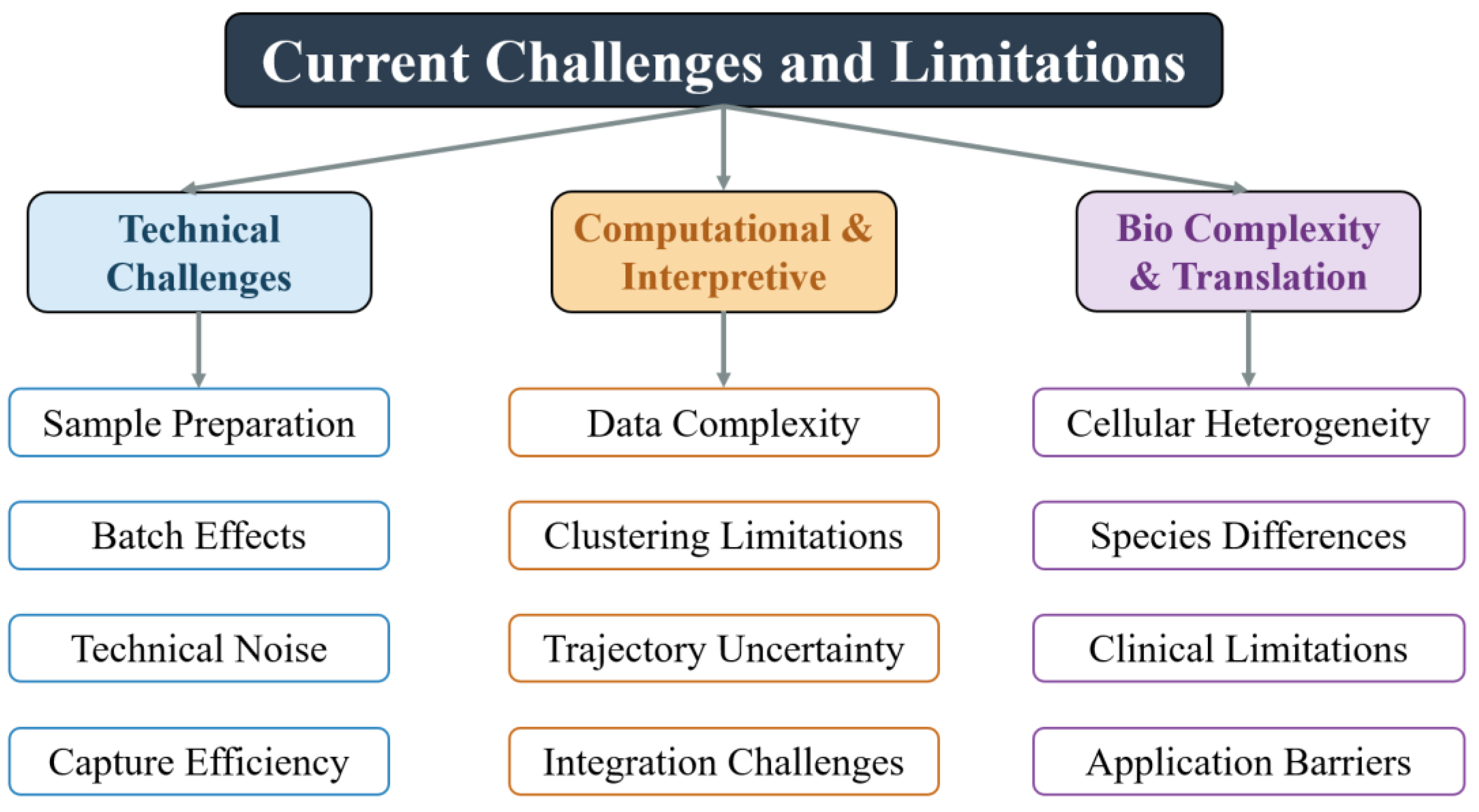

4. Current Challenges and Limitations

4.1. Technical Challenges

4.2. Computational and Interpretive Bottlenecks

4.3. Biological Complexity and Clinical Translation

5. Future Directions and Perspectives

5.1. Toward a Comprehensive Spinal Cord Cell Atlas

5.2. AI and Machine Learning in Single-Cell Analysis

5.3. Personalized Medicine and Regenerative Therapies

6. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| scRNA-seq | Single-cell RNA sequencing |

| CNS | Central Nervous System |

| SCI | Spinal Cord Injury |

| SMA | Spinal Muscular Atrophy |

| QC | Quality Control |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| PBMCs | Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells |

| SMN | Survival Motor Neuron |

| ALS | Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis |

| GNNs | Graph Neural Networks |

References

- Harrow-Mortelliti M, Reddy V, Jimsheleishvili G. Physiology, Spinal Cord. [Updated 2023 Mar 17]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK544267/.

- Bahney, J., & von Bartheld, C. S. (2018). The Cellular Composition and Glia-Neuron Ratio in the Spinal Cord of a Human and a Nonhuman Primate: Comparison With Other Species and Brain Regions. Anatomical record (Hoboken, N.J. : 2007), 301(4), 697–710. [CrossRef]

- Liau, E. S., Jin, S., Chen, Y. C., Liu, W. S., Calon, M., Nedelec, S., Nie, Q., & Chen, J. A. (2023). Single-cell transcriptomic analysis reveals diversity within mammalian spinal motor neurons. Nature communications, 14(1), 46. [CrossRef]

- Blum, J. A., Klemm, S., Shadrach, J. L., Guttenplan, K. A., Nakayama, L., Kathiria, A., Hoang, P. T., Gautier, O., Kaltschmidt, J. A., Greenleaf, W. J., & Gitler, A. D. (2021). Single-cell transcriptomic analysis of the adult mouse spinal cord reveals molecular diversity of autonomic and skeletal motor neurons. Nature neuroscience, 24(4), 572–583. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R., Zhou, R., Chen, Z., Gao, S., & Zhou, F. (2022). The Glial Cells Respond to Spinal Cord Injury. Frontiers in neurology, 13, 844497. [CrossRef]

- Jäkel, S., & Dimou, L. (2017). Glial Cells and Their Function in the Adult Brain: A Journey through the History of Their Ablation. Frontiers in cellular neuroscience, 11, 24. [CrossRef]

- Gaudet, A. D., & Fonken, L. K. (2018). Glial Cells Shape Pathology and Repair After Spinal Cord Injury. Neurotherapeutics : the journal of the American Society for Experimental NeuroTherapeutics, 15(3), 554–577. [CrossRef]

- Tang, F., Barbacioru, C., Wang, Y., Nordman, E., Lee, C., Xu, N., Wang, X., Bodeau, J., Tuch, B. B., Siddiqui, A., Lao, K., & Surani, M. A. (2009). mRNA-Seq whole-transcriptome analysis of a single cell. Nature methods, 6(5), 377–382. [CrossRef]

- Shen, X., Zhao, Y., Wang, Z., & Shi, Q. (2022). Recent advances in high-throughput single-cell transcriptomics and spatial transcriptomics. Lab on a chip, 22(24), 4774–4791. [CrossRef]

- Wirz, J., Fessler, L. I., & Gehring, W. J. (1986). Localization of the Antennapedia protein in Drosophila embryos and imaginal discs. The EMBO journal, 5(12), 3327–3334. [CrossRef]

- Ståhl, P. L., Salmén, F., Vickovic, S., Lundmark, A., Navarro, J. F., Magnusson, J., Giacomello, S., Asp, M., Westholm, J. O., Huss, M., Mollbrink, A., Linnarsson, S., Codeluppi, S., Borg, Å., Pontén, F., Costea, P. I., Sahlén, P., Mulder, J., Bergmann, O., Lundeberg, J., … Frisén, J. (2016). Visualization and analysis of gene expression in tissue sections by spatial transcriptomics. Science (New York, N.Y.), 353(6294), 78–82. [CrossRef]

- Molla Desta, G., & Birhanu, A. G. (2025). Advancements in single-cell RNA sequencing and spatial transcriptomics: transforming biomedical research. Acta biochimica Polonica, 72, 13922. [CrossRef]

- Aldridge, S., & Teichmann, S. A. (2020). Single cell transcriptomics comes of age. Nature communications, 11(1), 4307. [CrossRef]

- Delile, J., Rayon, T., Melchionda, M., Edwards, A., Briscoe, J., & Sagner, A. (2019). Single cell transcriptomics reveals spatial and temporal dynamics of gene expression in the developing mouse spinal cord. Development (Cambridge, England), 146(12), dev173807. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D., Chen, Y., Wei, Y., Chen, H., Wu, Y., Wu, L., Li, J., Ren, Q., Miao, C., Zhu, T., Liu, J., Ke, B., & Zhou, C. (2024). Spatial transcriptomics and single-nucleus RNA sequencing reveal a transcriptomic atlas of adult human spinal cord. eLife, 12, RP92046. [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, A. B., Roco, C. M., Muscat, R. A., Kuchina, A., Sample, P., Yao, Z., Graybuck, L. T., Peeler, D. J., Mukherjee, S., Chen, W., Pun, S. H., Sellers, D. L., Tasic, B., & Seelig, G. (2018). Single-cell profiling of the developing mouse brain and spinal cord with split-pool barcoding. Science (New York, N.Y.), 360(6385), 176–182. [CrossRef]

- Sathyamurthy, A., Johnson, K. R., Matson, K. J. E., Dobrott, C. I., Li, L., Ryba, A. R., Bergman, T. B., Kelly, M. C., Kelley, M. W., & Levine, A. J. (2018). Massively Parallel Single Nucleus Transcriptional Profiling Defines Spinal Cord Neurons and Their Activity during Behavior. Cell reports, 22(8), 2216–2225. [CrossRef]

- Jovic, D., Liang, X., Zeng, H., Lin, L., Xu, F., & Luo, Y. (2022). Single-cell RNA sequencing technologies and applications: A brief overview. Clinical and translational medicine, 12(3), e694. [CrossRef]

- Ramsköld, D., Luo, S., Wang, Y. C., Li, R., Deng, Q., Faridani, O. R., Daniels, G. A., Khrebtukova, I., Loring, J. F., Laurent, L. C., Schroth, G. P., & Sandberg, R. (2012). Full-length mRNA-Seq from single-cell levels of RNA and individual circulating tumor cells. Nature biotechnology, 30(8), 777–782. [CrossRef]

- Wu, X., Yang, B., Udo-Inyang, I., Ji, S., Ozog, D., Zhou, L., & Mi, Q. S. (2018). Research Techniques Made Simple: Single-Cell RNA Sequencing and its Applications in Dermatology. The Journal of investigative dermatology, 138(5), 1004–1009. [CrossRef]

- Macosko, E. Z., Basu, A., Satija, R., Nemesh, J., Shekhar, K., Goldman, M., Tirosh, I., Bialas, A. R., Kamitaki, N., Martersteck, E. M., Trombetta, J. J., Weitz, D. A., Sanes, J. R., Shalek, A. K., Regev, A., & McCarroll, S. A. (2015). Highly Parallel Genome-wide Expression Profiling of Individual Cells Using Nanoliter Droplets. Cell, 161(5), 1202–1214. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G. X., Terry, J. M., Belgrader, P., Ryvkin, P., Bent, Z. W., Wilson, R., Ziraldo, S. B., Wheeler, T. D., McDermott, G. P., Zhu, J., Gregory, M. T., Shuga, J., Montesclaros, L., Underwood, J. G., Masquelier, D. A., Nishimura, S. Y., Schnall-Levin, M., Wyatt, P. W., Hindson, C. M., Bharadwaj, R., … Bielas, J. H. (2017). Massively parallel digital transcriptional profiling of single cells. Nature communications, 8, 14049. [CrossRef]

- Anaparthy, N., Ho, Y. J., Martelotto, L., Hammell, M., & Hicks, J. (2019). Single-Cell Applications of Next-Generation Sequencing. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine, 9(10), a026898. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., He, Y., Zhang, Q., Ren, X., & Zhang, Z. (2021). Direct Comparative Analyses of 10X Genomics Chromium and Smart-seq2. Genomics, proteomics & bioinformatics, 19(2), 253–266. [CrossRef]

- Picelli, S., Björklund, Å. K., Faridani, O. R., Sagasser, S., Winberg, G., & Sandberg, R. (2013). Smart-seq2 for sensitive full-length transcriptome profiling in single cells. Nature methods, 10(11), 1096–1098. [CrossRef]

- Hagemann-Jensen, M., Ziegenhain, C., Chen, P., Ramsköld, D., Hendriks, G. J., Larsson, A. J. M., Faridani, O. R., & Sandberg, R. (2020). Single-cell RNA counting at allele and isoform resolution using Smart-seq3. Nature biotechnology, 38(6), 708–714. [CrossRef]

- Klein, A. M., Mazutis, L., Akartuna, I., Tallapragada, N., Veres, A., Li, V., Peshkin, L., Weitz, D. A., & Kirschner, M. W. (2015). Droplet barcoding for single-cell transcriptomics applied to embryonic stem cells. Cell, 161(5), 1187–1201. [CrossRef]

- Ziegenhain, C., Vieth, B., Parekh, S., Reinius, B., Guillaumet-Adkins, A., Smets, M., Leonhardt, H., Heyn, H., Hellmann, I., & Enard, W. (2017). Comparative Analysis of Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Methods. Molecular cell, 65(4), 631–643.e4. [CrossRef]

- Chen, A., Liao, S., Cheng, M., Ma, K., Wu, L., Lai, Y., Qiu, X., Yang, J., Xu, J., Hao, S., Wang, X., Lu, H., Chen, X., Liu, X., Huang, X., Li, Z., Hong, Y., Jiang, Y., Peng, J., Liu, S., … Wang, J. (2022). Spatiotemporal transcriptomic atlas of mouse organogenesis using DNA nanoball-patterned arrays. Cell, 185(10), 1777–1792.e21. [CrossRef]

- Andersen, J., Thom, N., Shadrach, J. L., Chen, X., Onesto, M. M., Amin, N. D., Yoon, S. J., Li, L., Greenleaf, W. J., Müller, F., Pașca, A. M., Kaltschmidt, J. A., & Pașca, S. P. (2023). Single-cell transcriptomic landscape of the developing human spinal cord. Nature neuroscience, 26(5), 902–914. [CrossRef]

- Matson, K. J. E., Russ, D. E., Kathe, C., Hua, I., Maric, D., Ding, Y., Krynitsky, J., Pursley, R., Sathyamurthy, A., Squair, J. W., Levi, B. P., Courtine, G., & Levine, A. J. (2022). Single cell atlas of spinal cord injury in mice reveals a pro-regenerative signature in spinocerebellar neurons. Nature communications, 13(1), 5628. [CrossRef]

- Cao, J., Spielmann, M., Qiu, X., Huang, X., Ibrahim, D. M., Hill, A. J., Zhang, F., Mundlos, S., Christiansen, L., Steemers, F. J., Trapnell, C., & Shendure, J. (2019). The single-cell transcriptional landscape of mammalian organogenesis. Nature, 566(7745), 496–502. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X., Mao, Q., Tang, Y., Wang, L., Chawla, R., Pliner, H. A., & Trapnell, C. (2017). Reversed graph embedding resolves complex single-cell trajectories. Nature methods, 14(10), 979–982. [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, C. S., Wilson, J. R., Nori, S., Kotter, M. R. N., Druschel, C., Curt, A., & Fehlings, M. G. (2017). Traumatic spinal cord injury. Nature reviews. Disease primers, 3, 17018. [CrossRef]

- Wahane, S., Zhou, X., Zhou, X., Guo, L., Friedl, M. S., Kluge, M., Ramakrishnan, A., Shen, L., Friedel, C. C., Zhang, B., Friedel, R. H., & Zou, H. (2021). Diversified transcriptional responses of myeloid and glial cells in spinal cord injury shaped by HDAC3 activity. Science advances, 7(9), eabd8811. [CrossRef]

- Li, C., Wu, Z., Zhou, L., Shao, J., Hu, X., Xu, W., Ren, Y., Zhu, X., Ge, W., Zhang, K., Liu, J., Huang, R., Yu, J., Luo, D., Yang, X., Zhu, W., Zhu, R., Zheng, C., Sun, Y. E., & Cheng, L. (2022). Temporal and spatial cellular and molecular pathological alterations with single-cell resolution in the adult spinal cord after injury. Signal transduction and targeted therapy, 7(1), 65. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q., Wu, X., Fan, Y., Zhang, H., Yin, M., Xue, X., Yin, Y., Jin, C., Quan, R., Jiang, P., Liu, Y., Yu, C., Kuang, W., Chen, B., Li, J., Chen, Z., Hu, Y., Xiao, Z., Zhao, Y., & Dai, J. (2025). Characterizing progenitor cells in developing and injured spinal cord: Insights from single-nucleus transcriptomics and lineage tracing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 122(2), e2413140122. [CrossRef]

- Hildebrand, C., Remahl, S., Persson, H., & Bjartmar, C. (1993). Myelinated nerve fibres in the CNS. Progress in neurobiology, 40(3), 319–384. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z., Li, G., Wang, S., Zhang, N., Li, X., Zhang, F., Niu, J., Wang, N., Zu, J., & Wang, Y. (2023). Single-cell analysis of spinal cord injury reveals functional heterogeneity of oligodendrocyte lineage cells. Gene, 886, 147713. [CrossRef]

- Saraswathy, V. M., Zhou, L., & Mokalled, M. H. (2024). Single-cell analysis of innate spinal cord regeneration identifies intersecting modes of neuronal repair. Nature communications, 15(1), 6808. [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, E. R., Grice, L. F., Courtney, I. G., Lao, H. W., Jung, W., Ramkomuth, S., Xie, J., Brown, D. A., Walsham, J., Radford, K. J., Nguyen, Q. H., & Ruitenberg, M. J. (2024). Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals peripheral blood leukocyte responses to spinal cord injury in mice with humanised immune systems. Journal of neuroinflammation, 21(1), 63. [CrossRef]

- Yao, C., Cao, Y., Wang, D., Lv, Y., Liu, Y., Gu, X., Wang, Y., Wang, X., & Yu, B. (2022). Single-cell sequencing reveals microglia induced angiogenesis by specific subsets of endothelial cells following spinal cord injury. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, 36(7), e22393. [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, S., Bürglen, L., Reboullet, S., Clermont, O., Burlet, P., Viollet, L., Benichou, B., Cruaud, C., Millasseau, P., & Zeviani, M. (1995). Identification and characterization of a spinal muscular atrophy-determining gene. Cell, 80(1), 155–165. [CrossRef]

- Lobsiger, C. S., & Cleveland, D. W. (2007). Glial cells as intrinsic components of non-cell-autonomous neurodegenerative disease. Nature neuroscience, 10(11), 1355–1360. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J., Qiu, J., Yang, Q., Ju, Q., Qu, R., Wang, X., Wu, L., & Xing, L. (2022). Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals dysregulation of spinal cord cell types in a severe spinal muscular atrophy mouse model. PLoS genetics, 18(9), e1010392. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y., Peng, Y., Jie, J., Yang, Y., & Yang, P. (2022). The immune microenvironment and tissue engineering strategies for spinal cord regeneration. Frontiers in cellular neuroscience, 16, 969002. [CrossRef]

- Fu, S. P., Chen, S. Y., Pang, Q. M., Zhang, M., Wu, X. C., Wan, X., Wan, W. H., Ao, J., & Zhang, T. (2022). Advances in the research of the role of macrophage/microglia polarization-mediated inflammatory response in spinal cord injury. Frontiers in immunology, 13, 1014013. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q., Yu, B., Zhang, Y., Tian, Y., Yang, S., Chen, Y., & Wu, H. (2023). Combination of single-cell and bulk RNA seq reveals the immune infiltration landscape and targeted therapeutic drugs in spinal cord injury. Frontiers in immunology, 14, 1068359. [CrossRef]

- Mimi, M. A., Hasan, M. M., Takanashi, Y., Waliullah, A. S. M., Mamun, M. A., Chi, Z., Kahyo, T., Aramaki, S., Takatsuka, D., Koizumi, K., & Setou, M. (2024). UBL3 overexpression enhances EV-mediated Achilles protein secretion in conditioned media of MDA-MB-231 cells. Biochemical and biophysical research communications, 738, 150559. [CrossRef]

- Russ, D. E., Cross, R. B. P., Li, L., Koch, S. C., Matson, K. J. E., Yadav, A., Alkaslasi, M. R., Lee, D. I., Le Pichon, C. E., Menon, V., & Levine, A. J. (2021). A harmonized atlas of mouse spinal cord cell types and their spatial organization. Nature communications, 12(1), 5722. [CrossRef]

- Han, B., Zhou, S., Zhang, Y., Chen, S., Xi, W., Liu, C., Zhou, X., Yuan, M., Yu, X., Li, L., Wang, Y., Ren, H., Xie, J., Li, B., Ju, M., Zhou, Y., Liu, Z., Xiong, Z., Shen, L., Zhang, Y., … Yao, H. (2024). Integrating spatial and single-cell transcriptomics to characterize the molecular and cellular architecture of the ischemic mouse brain. Science translational medicine, 16(733), eadg1323. [CrossRef]

- Peng, R., Zhang, L., Xie, Y., Guo, S., Cao, X., & Yang, M. (2024). Spatial multi-omics analysis of the microenvironment in traumatic spinal cord injury: a narrative review. Frontiers in immunology, 15, 1432841. [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y., Huang, L., Dong, H., Yang, M., Ding, W., Zhou, X., Lu, T., Liu, Z., Zhou, X., Wang, M., Zeng, B., Sun, Y., Zhong, S., Wang, B., Wang, W., Yin, C., Wang, X., & Wu, Q. (2024). Decoding the spatiotemporal regulation of transcription factors during human spinal cord development. Cell research, 34(3), 193–213. [CrossRef]

- Miao, Z., Humphreys, B. D., McMahon, A. P., & Kim, J. (2021). Multi-omics integration in the age of million single-cell data. Nature reviews. Nephrology, 17(11), 710–724. [CrossRef]

- Gao, H., Zhang, B., Liu, L., Li, S., Gao, X., & Yu, B. (2023). A universal framework for single-cell multi-omics data integration with graph convolutional networks. Briefings in bioinformatics, 24(3), bbad081. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Hu, Z., Yu, T., Wang, Y., Wang, R., Wei, Y., Shu, J., Ma, J., & Li, Y. (2023). Con-AAE: contrastive cycle adversarial autoencoders for single-cell multi-omics alignment and integration. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England), 39(4), btad162. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z. J., & Gao, G. (2022). Multi-omics single-cell data integration and regulatory inference with graph-linked embedding. Nature biotechnology, 40(10), 1458–1466. [CrossRef]

- Yang, P., Jin, K., Yao, Y., Jin, L., Shao, X., Li, C., Lu, X., & Fan, X. (2025). Spatial integration of multi-omics single-cell data with SIMO. Nature communications, 16(1), 1265. [CrossRef]

- Luo, J., Fu, J., Lu, Z., & Tu, J. (2024). Deep learning in integrating spatial transcriptomics with other modalities. Briefings in bioinformatics, 26(1), bbae719. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A., Matson, K. J. E., Li, L., Hua, I., Petrescu, J., Kang, K., Alkaslasi, M. R., Lee, D. I., Hasan, S., Galuta, A., Dedek, A., Ameri, S., Parnell, J., Alshardan, M. M., Qumqumji, F. A., Alhamad, S. M., Wang, A. P., Poulen, G., Lonjon, N., Vachiery-Lahaye, F., … Levine, A. J. (2023). A cellular taxonomy of the adult human spinal cord. Neuron, 111(3), 328–344.e7. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R., & Nikolaou, N. (2024). RNA in axons, dendrites, synapses and beyond. Frontiers in molecular neuroscience, 17, 1397378. [CrossRef]

- Ament, S. A., & Poulopoulos, A. (2023). The brain's dark transcriptome: Sequencing RNA in distal compartments of neurons and glia. Current opinion in neurobiology, 81, 102725. [CrossRef]

- Skinnider, M. A., Gautier, M., Teo, A. Y. Y., Kathe, C., Hutson, T. H., Laskaratos, A., de Coucy, A., Regazzi, N., Aureli, V., James, N. D., Schneider, B., Sofroniew, M. V., Barraud, Q., Bloch, J., Anderson, M. A., Squair, J. W., & Courtine, G. (2024). Single-cell and spatial atlases of spinal cord injury in the Tabulae Paralytica. Nature, 631(8019), 150–163. [CrossRef]

- Milich, L. M., Ryan, C. B., & Lee, J. K. (2019). The origin, fate, and contribution of macrophages to spinal cord injury pathology. Acta neuropathologica, 137(5), 785–797. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R., Sun, T., Song, D., & Li, J. J. (2022). Statistics or biology: the zero-inflation controversy about scRNA-seq data. Genome biology, 23(1), 31. [CrossRef]

- Kharchenko, P. V., Silberstein, L., & Scadden, D. T. (2014). Bayesian approach to single-cell differential expression analysis. Nature methods, 11(7), 740–742. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z., Hu, S. K., Campbell, V., Tatters, A. O., Heidelberg, K. B., & Caron, D. A. (2017). Single-cell transcriptomics of small microbial eukaryotes: limitations and potential. The ISME journal, 11(5), 1282–1285. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J., Qiu, J., Yang, Q., Ju, Q., Qu, R., Wang, X., Wu, L., & Xing, L. (2022). Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals dysregulation of spinal cord cell types in a severe spinal muscular atrophy mouse model. PLoS genetics, 18(9), e1010392. [CrossRef]

- Korsunsky, I., Millard, N., Fan, J., Slowikowski, K., Zhang, F., Wei, K., Baglaenko, Y., Brenner, M., Loh, P. R., & Raychaudhuri, S. (2019). Fast, sensitive and accurate integration of single-cell data with Harmony. Nature methods, 16(12), 1289–1296. [CrossRef]

- Nichterwitz, S., Chen, G., Aguila Benitez, J., Yilmaz, M., Storvall, H., Cao, M., Sandberg, R., Deng, Q., & Hedlund, E. (2016). Laser capture microscopy coupled with Smart-seq2 for precise spatial transcriptomic profiling. Nature communications, 7, 12139. [CrossRef]

- Chen, K. H., Boettiger, A. N., Moffitt, J. R., Wang, S., & Zhuang, X. (2015). RNA imaging. Spatially resolved, highly multiplexed RNA profiling in single cells. Science (New York, N.Y.), 348(6233), aaa6090. [CrossRef]

- Rodriques, S. G., Stickels, R. R., Goeva, A., Martin, C. A., Murray, E., Vanderburg, C. R., Welch, J., Chen, L. M., Chen, F., & Macosko, E. Z. (2019). Slide-seq: A scalable technology for measuring genome-wide expression at high spatial resolution. Science (New York, N.Y.), 363(6434), 1463–1467. [CrossRef]

- Marx V. (2021). Method of the Year: spatially resolved transcriptomics. Nature methods, 18(1), 9–14. [CrossRef]

- Tran, H. T. N., Ang, K. S., Chevrier, M., Zhang, X., Lee, N. Y. S., Goh, M., & Chen, J. (2020). A benchmark of batch-effect correction methods for single-cell RNA sequencing data. Genome biology, 21(1), 12. [CrossRef]

- Luecken, M. D., & Theis, F. J. (2019). Current best practices in single-cell RNA-seq analysis: a tutorial. Molecular systems biology, 15(6), e8746. [CrossRef]

- Chen, G., Ning, B., & Shi, T. (2019). Single-Cell RNA-Seq Technologies and Related Computational Data Analysis. Frontiers in genetics, 10, 317. [CrossRef]

- Adil, A., Kumar, V., Jan, A. T., & Asger, M. (2021). Single-Cell Transcriptomics: Current Methods and Challenges in Data Acquisition and Analysis. Frontiers in neuroscience, 15, 591122. [CrossRef]

- Haque, A., Engel, J., Teichmann, S. A., & Lönnberg, T. (2017). A practical guide to single-cell RNA-sequencing for biomedical research and clinical applications. Genome medicine, 9(1), 75. [CrossRef]

- Haghverdi, L., Lun, A. T. L., Morgan, M. D., & Marioni, J. C. (2018). Batch effects in single-cell RNA-sequencing data are corrected by matching mutual nearest neighbors. Nature biotechnology, 36(5), 421–427. [CrossRef]

- Li, W. V., & Li, J. J. (2018). An accurate and robust imputation method scImpute for single-cell RNA-seq data. Nature communications, 9(1), 997. [CrossRef]

- Huang, M., Wang, J., Torre, E., Dueck, H., Shaffer, S., Bonasio, R., Murray, J. I., Raj, A., Li, M., & Zhang, N. R. (2018). SAVER: gene expression recovery for single-cell RNA sequencing. Nature methods, 15(7), 539–542. [CrossRef]

- van Dijk, D., Sharma, R., Nainys, J., Yim, K., Kathail, P., Carr, A. J., Burdziak, C., Moon, K. R., Chaffer, C. L., Pattabiraman, D., Bierie, B., Mazutis, L., Wolf, G., Krishnaswamy, S., & Pe'er, D. (2018). Recovering Gene Interactions from Single-Cell Data Using Data Diffusion. Cell, 174(3), 716–729.e27. [CrossRef]

- Qiu P. (2020). Embracing the dropouts in single-cell RNA-seq analysis. Nature communications, 11(1), 1169. [CrossRef]

- Rayon, T., Maizels, R. J., Barrington, C., & Briscoe, J. (2021). Single-cell transcriptome profiling of the human developing spinal cord reveals a conserved genetic programme with human-specific features. Development (Cambridge, England), 148(15), dev199711. [CrossRef]

- Argelaguet R, Velten B, Arnol D, Dietrich S, Zenz T, Marioni JC, Buettner F, Huber W, Stegle O. Multi-Omics Factor Analysis-a framework for unsupervised integration of multi-omics data sets. Mol Syst Biol. 2018 Jun 20;14(6):e8124. doi: 10.15252/msb.20178124. PMID: 29925568; PMCID: PMC6010767.

- Stuart, T., Butler, A., Hoffman, P., Hafemeister, C., Papalexi, E., Mauck, W. M., 3rd, Hao, Y., Stoeckius, M., Smibert, P., & Satija, R. (2019). Comprehensive Integration of Single-Cell Data. Cell, 177(7), 1888–1902.e21. [CrossRef]

- Sofroniew, M. V., & Vinters, H. V. (2010). Astrocytes: biology and pathology. Acta neuropathologica, 119(1), 7–35. [CrossRef]

- Peirs, C., & Seal, R. P. (2016). Neural circuits for pain: Recent advances and current views. Science (New York, N.Y.), 354(6312), 578–584. [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y., Wu, X., Han, S., Zhang, Q., Sun, Z., Chen, B., Xue, X., Zhang, H., Chen, Z., Yin, M., Xiao, Z., Zhao, Y., & Dai, J. (2023). Single-cell analysis reveals region-heterogeneous responses in rhesus monkey spinal cord with complete injury. Nature communications, 14(1), 4796. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q., Wu, X., Fan, Y., Jiang, P., Zhao, Y., Yang, Y., Han, S., Xu, B., Chen, B., Han, J., Sun, M., Zhao, G., Xiao, Z., Hu, Y., & Dai, J. (2021). Single-cell analysis reveals dynamic changes of neural cells in developing human spinal cord. EMBO reports, 22(11), e52728. [CrossRef]

- Kushnarev, M., Pirvulescu, I. P., Candido, K. D., & Knezevic, N. N. (2020). Neuropathic pain: preclinical and early clinical progress with voltage-gated sodium channel blockers. Expert opinion on investigational drugs, 29(3), 259–271. [CrossRef]

- Awuah, W. A., Ahluwalia, A., Ghosh, S., Roy, S., Tan, J. K., Adebusoye, F. T., Ferreira, T., Bharadwaj, H. R., Shet, V., Kundu, M., Yee, A. L. W., Abdul-Rahman, T., & Atallah, O. (2023). The molecular landscape of neurological disorders: insights from single-cell RNA sequencing in neurology and neurosurgery. European journal of medical research, 28(1), 529. [CrossRef]

- Lähnemann, D., Köster, J., Szczurek, E., McCarthy, D. J., Hicks, S. C., Robinson, M. D., Vallejos, C. A., Campbell, K. R., Beerenwinkel, N., Mahfouz, A., Pinello, L., Skums, P., Stamatakis, A., Attolini, C. S., Aparicio, S., Baaijens, J., Balvert, M., Barbanson, B., Cappuccio, A., Corleone, G., … Schönhuth, A. (2020). Eleven grand challenges in single-cell data science. Genome biology, 21(1), 31. [CrossRef]

- BRAIN Initiative Cell Census Network (BICCN) (2021). A multimodal cell census and atlas of the mammalian primary motor cortex. Nature, 598(7879), 86–102. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q., & Xu, D. (2022). Deep learning shapes single-cell data analysis. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology, 23(5), 303–304. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Ma, A., Chang, Y., Gong, J., Jiang, Y., Qi, R., Wang, C., Fu, H., Ma, Q., & Xu, D. (2022). Author Correction: scGNN is a novel graph neural network framework for single-cell RNA-Seq analyses. Nature communications, 13(1), 2554. [CrossRef]

- Xi, N. M., & Li, J. J. (2023). Exploring the optimization of autoencoder design for imputing single-cell RNA sequencing data. Computational and structural biotechnology journal, 21, 4079–4095. [CrossRef]

- Cao, X., Xing, L., Majd, E., He, H., Gu, J., & Zhang, X. (2022). A Systematic Evaluation of Supervised Machine Learning Algorithms for Cell Phenotype Classification Using Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Data. Frontiers in genetics, 13, 836798. [CrossRef]

- Shao, X., Yang, H., Zhuang, X., Liao, J., Yang, P., Cheng, J., Lu, X., Chen, H., & Fan, X. (2021). scDeepSort: a pre-trained cell-type annotation method for single-cell transcriptomics using deep learning with a weighted graph neural network. Nucleic acids research, 49(21), e122. [CrossRef]

- Ma, F., & Pellegrini, M. (2020). ACTINN: automated identification of cell types in single cell RNA sequencing. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England), 36(2), 533–538. [CrossRef]

- Yang, F., Wang, W., Wang, F. et al. scBERT as a large-scale pretrained deep language model for cell type annotation of single-cell RNA-seq data. Nat Mach Intell 4, 852–866 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. R., & Du, P. F. (2025). WCSGNet: a graph neural network approach using weighted cell-specific networks for cell-type annotation in scRNA-seq. Frontiers in genetics, 16, 1553352. [CrossRef]

- Dobrott, C. I., Sathyamurthy, A., & Levine, A. J. (2019). Decoding Cell Type Diversity Within the Spinal Cord. Current opinion in physiology, 8, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L., Huang, Y., Zheng, Y., Liao, Y., Ma, S., & Wang, Q. (2024). ScnML models single-cell transcriptome to predict spinal cord neuronal cell status. Frontiers in genetics, 15, 1413484. [CrossRef]

- Fang, M., Gorin, G., & Pachter, L. (2025). Trajectory inference from single-cell genomics data with a process time model. PLoS computational biology, 21(1), e1012752. [CrossRef]

- Biancalani, T., Scalia, G., Buffoni, L., Avasthi, R., Lu, Z., Sanger, A., Tokcan, N., Vanderburg, C. R., Segerstolpe, Å., Zhang, M., Avraham-Davidi, I., Vickovic, S., Nitzan, M., Ma, S., Subramanian, A., Lipinski, M., Buenrostro, J., Brown, N. B., Fanelli, D., Zhuang, X., … Regev, A. (2021). Deep learning and alignment of spatially resolved single-cell transcriptomes with Tangram. Nature methods, 18(11), 1352–1362. [CrossRef]

- A graph neural network that combines scRNA-seq and protein-protein interaction data. (2025). Nature methods, 22(4), 660–661. [CrossRef]

- Jaja, B. N. R., Badhiwala, J., Guest, J., Harrop, J., Shaffrey, C., Boakye, M., Kurpad, S., Grossman, R., Toups, E., Geisler, F., Kwon, B., Aarabi, B., Kotter, M., Fehlings, M. G., & Wilson, J. R. (2021). Trajectory-Based Classification of Recovery in Sensorimotor Complete Traumatic Cervical Spinal Cord Injury. Neurology, 96(22), e2736–e2748. [CrossRef]

- Patel, M., Magre, N., Motwani, H., & Brown, N. B. (2024). Advances in machine learning, statistical methods, and AI for single-cell RNA annotation using raw count matrices in scRNA-seq data (No. arXiv:2406.05258; 版 1). arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Shen, X., & Li, X. (2024). Deep-learning methods for unveiling large-scale single-cell transcriptomes. Cancer biology & medicine, 20(12), 972–980. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y., Zhu, S., Yu, B., & Yao, C. (2022). Single-cell RNA sequencing for traumatic spinal cord injury. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, 36(12), e22656. [CrossRef]

- Shu, M., Xue, X., Nie, H., Wu, X., Sun, M., Qiao, L., Li, X., Xu, B., Xiao, Z., Zhao, Y., Fan, Y., Chen, B., Zhang, J., Shi, Y., Yang, Y., Lu, F., & Dai, J. (2022). Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals Nestin+ active neural stem cells outside the central canal after spinal cord injury. Science China. Life sciences, 65(2), 295–308. [CrossRef]

- Li, D., Ma, Y., Huang, W., Li, X., Liu, H., Xiong, C., Zhao, Q., Wang, B., Lai, X., Huang, S., Wei, Y., Chen, J., Zhang, X., Wei, L., Ye, W., Chen, Q., Rong, L., Xiang, A. P., & Li, W. (2023). Modeling human spine-spinal cord organogenesis by hPSC-derived neuromesodermal progenitors (页 2023.07.20.549829). bioRxiv. [CrossRef]

- Chelyshev, Y. A., & Ermolin, I. L. (2023). RNA Sequencing and Spatial Transcriptomics in Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury (Review). Sovremennye tekhnologii v meditsine, 15(6), 75–86. [CrossRef]

| Study | Species | Developmental Stage | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Delile et al. | Mouse | E9.5–E13.5 | Spatial/temporal dynamics of neural progenitors; novel markers in dorsoventral domains |

| Andersen et al. | Human | ~22 weeks gestation | Glial heterogeneity, astrocyte regionalization, disease gene mapping to specific cell types |

| Sathyamurthy et al. | Mouse | Adult | 43 neuronal subtypes, region-specific distribution, spinal neuron molecular map |

| Blum et al. | Mouse | Adult | Motor neuron heterogeneity, transcriptional profiles linked to axonal targeting and function |

| Cao et al. | Mouse | Organogenesis (multi-stage) | Spinal progenitor transcriptional transitions, Hox genes, Shh pathway in developmental regulation |

| Zhang et al. | Human | Adult | 21 neuronal subtypes, spatial distribution, human-mouse comparison, sex-specific transcription |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).