Submitted:

28 April 2025

Posted:

29 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- What are the factors that impact the adoption of CS and PSAVs?

- Do machine learning models predict whether a traveler is likely to adopt CS or PSAVs based on safety perceptions?

- How do travelers inside cities perceive the safety of CS and PSAVs?

- Do people's selection of PSAVs and CS vary by demographic variables?

2. Literature Review

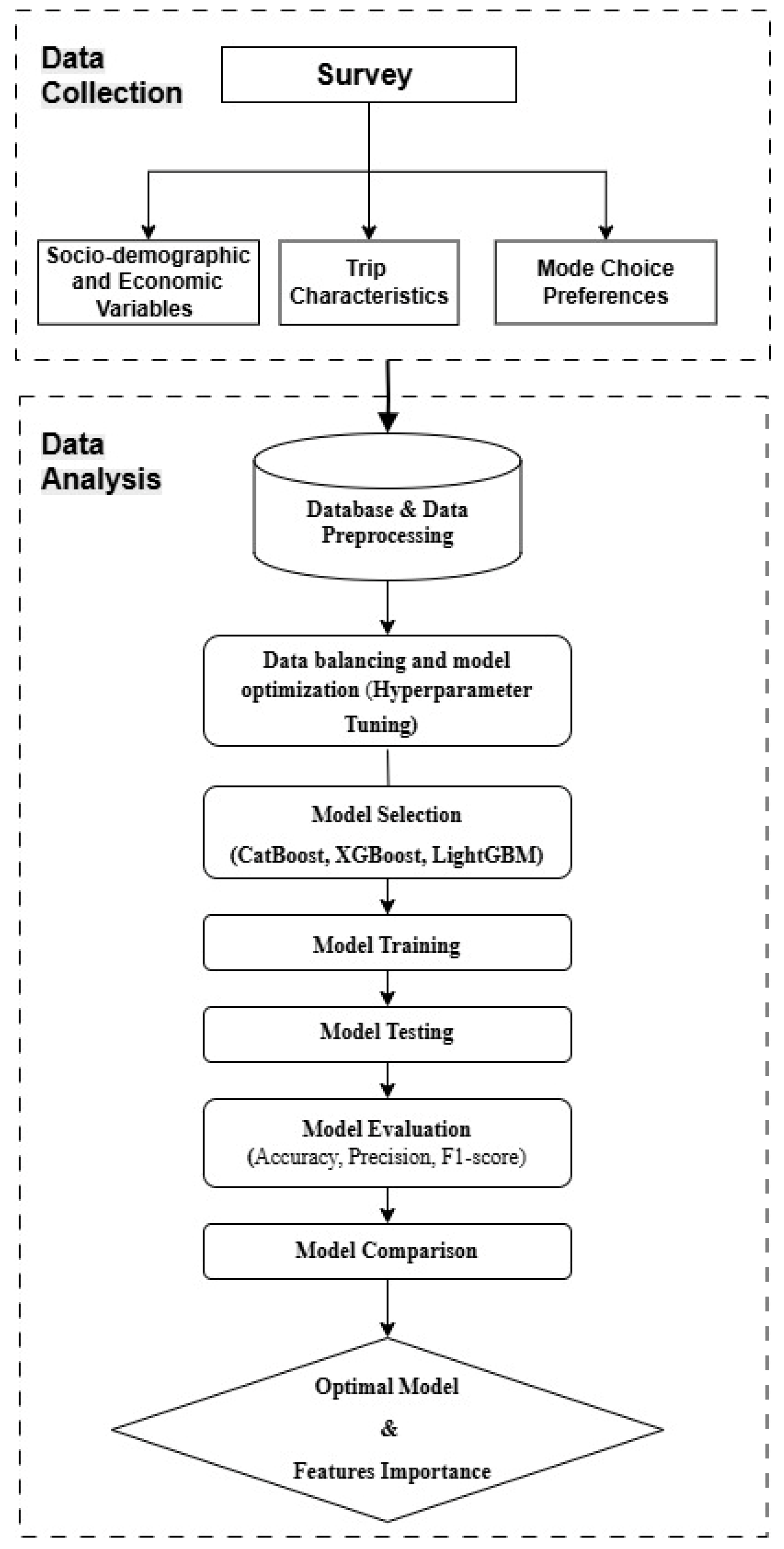

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

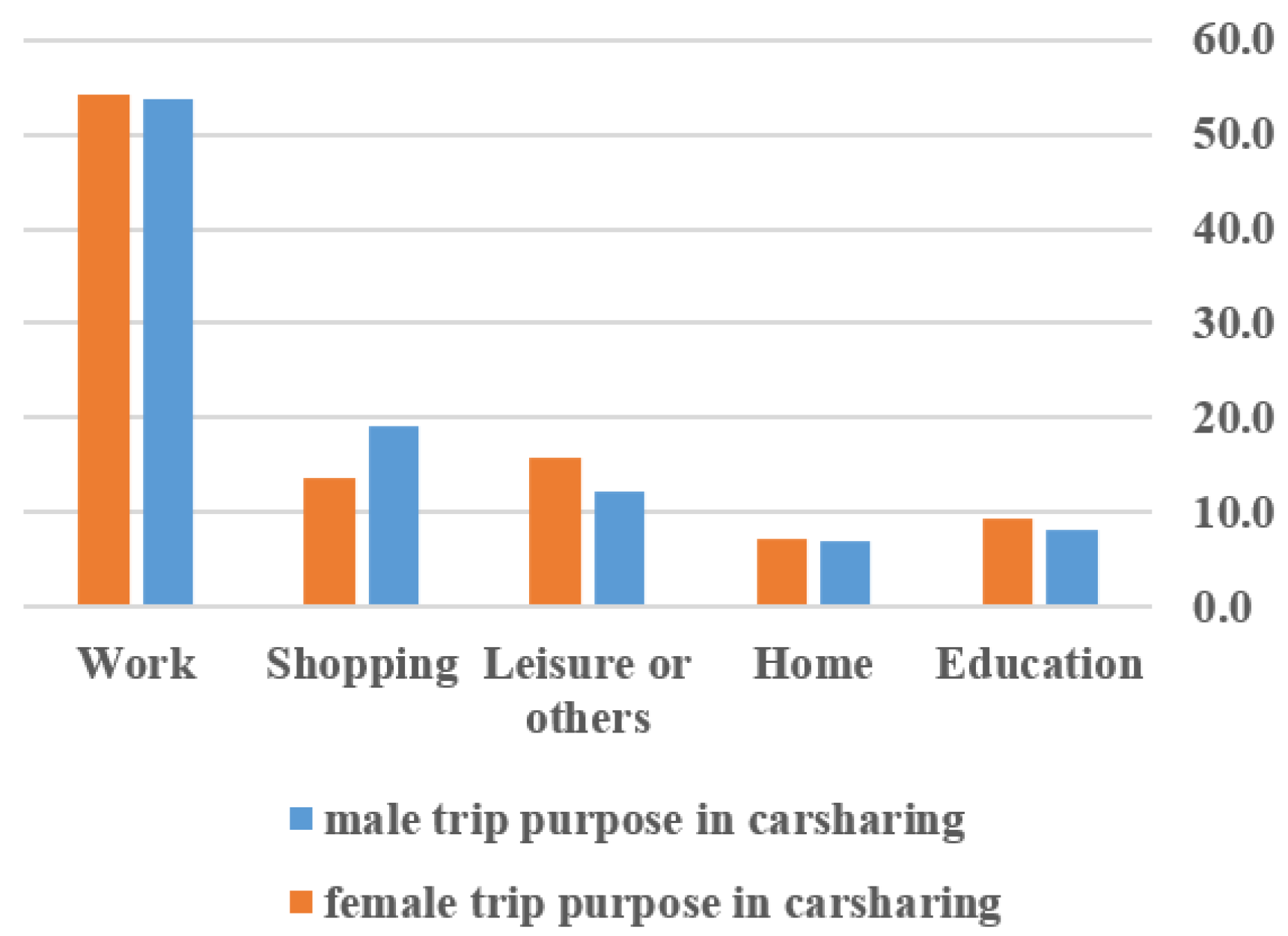

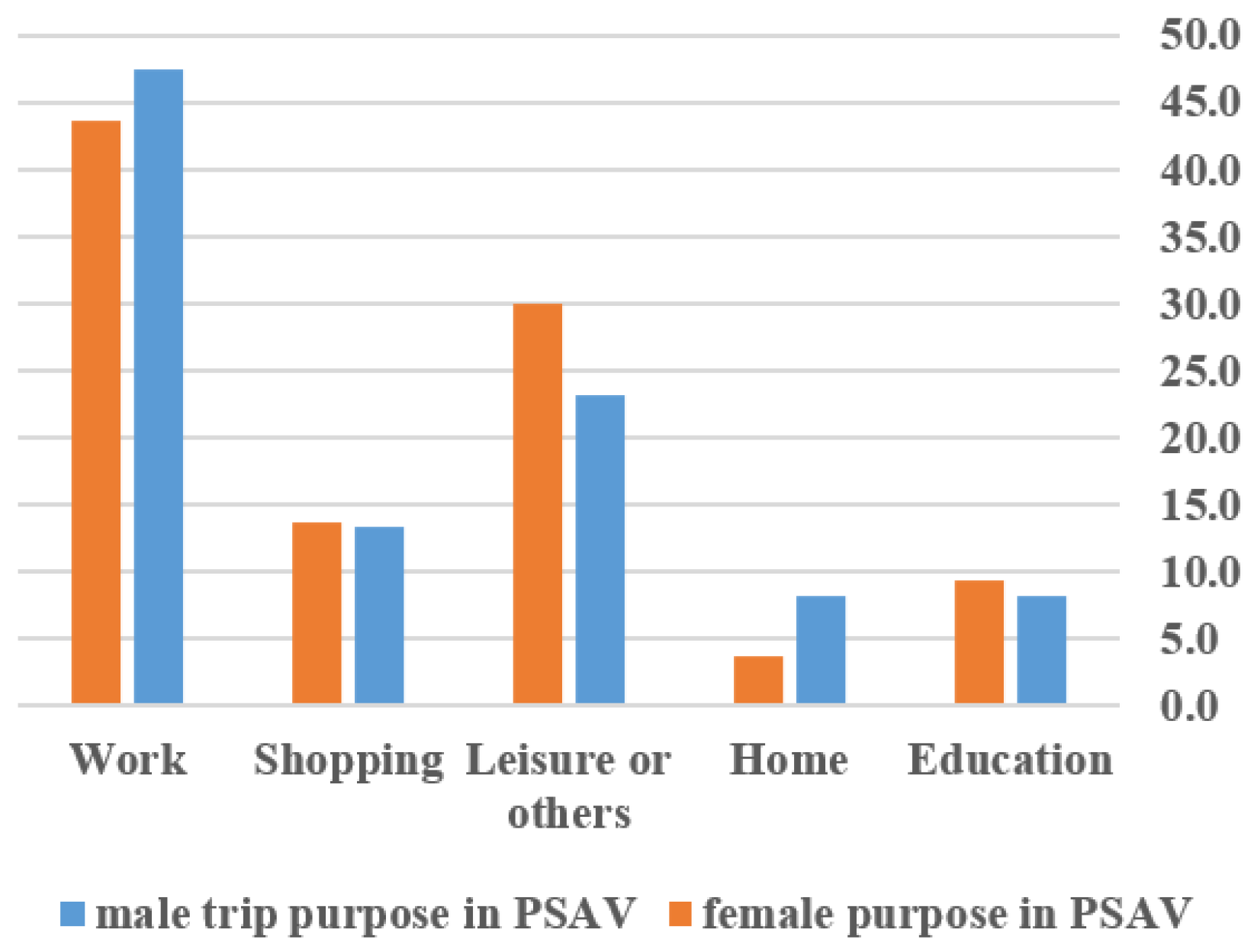

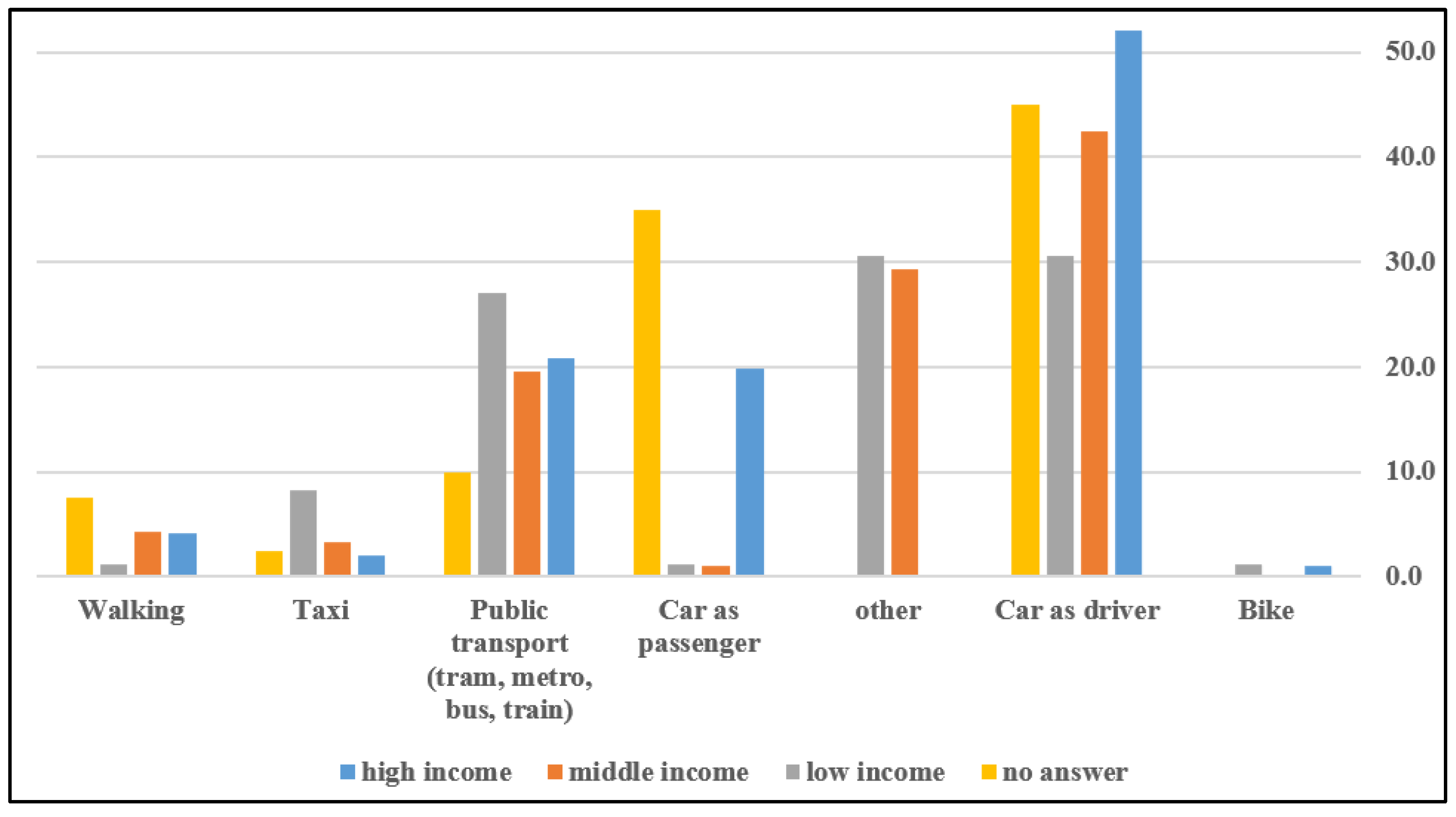

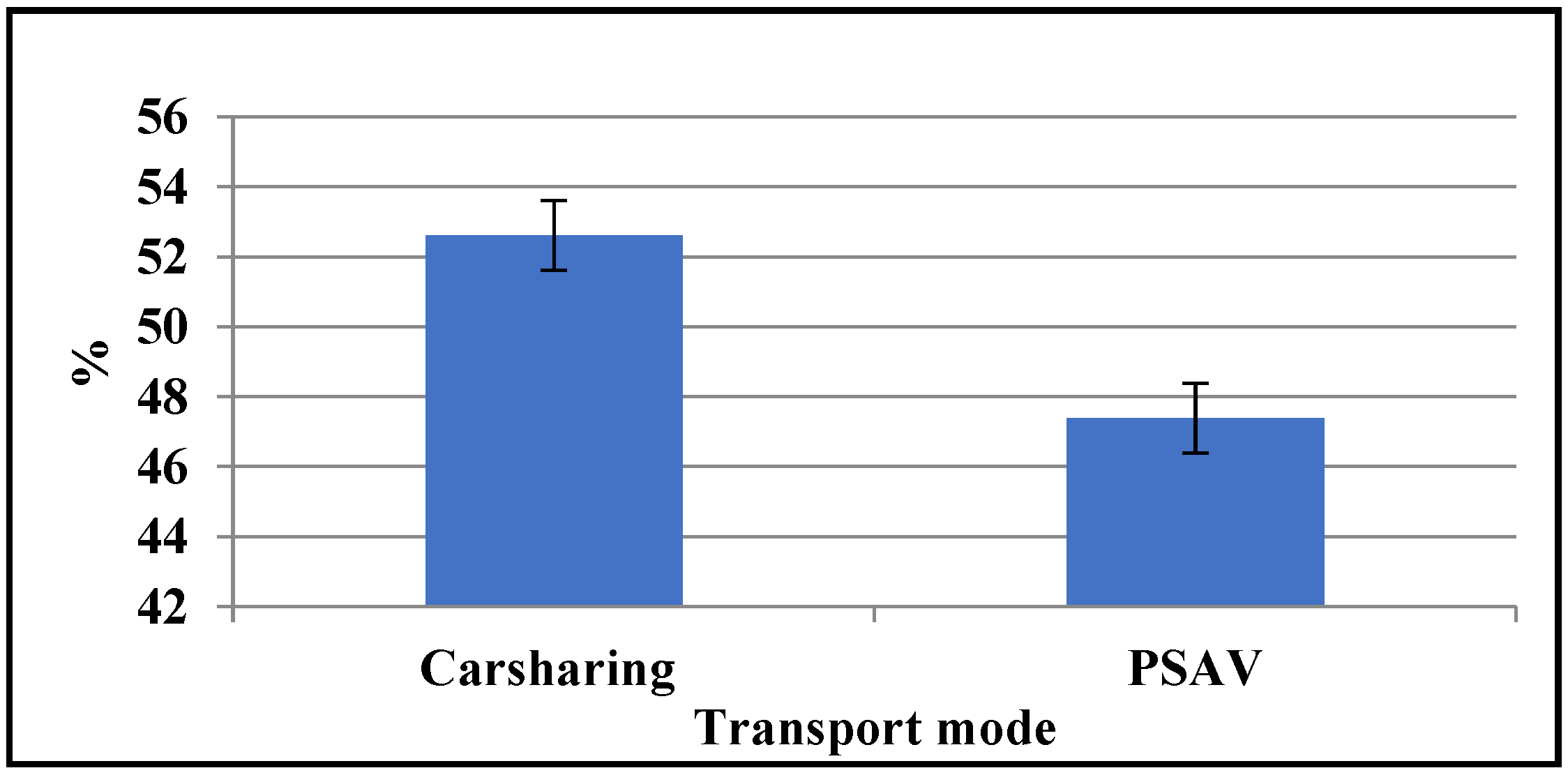

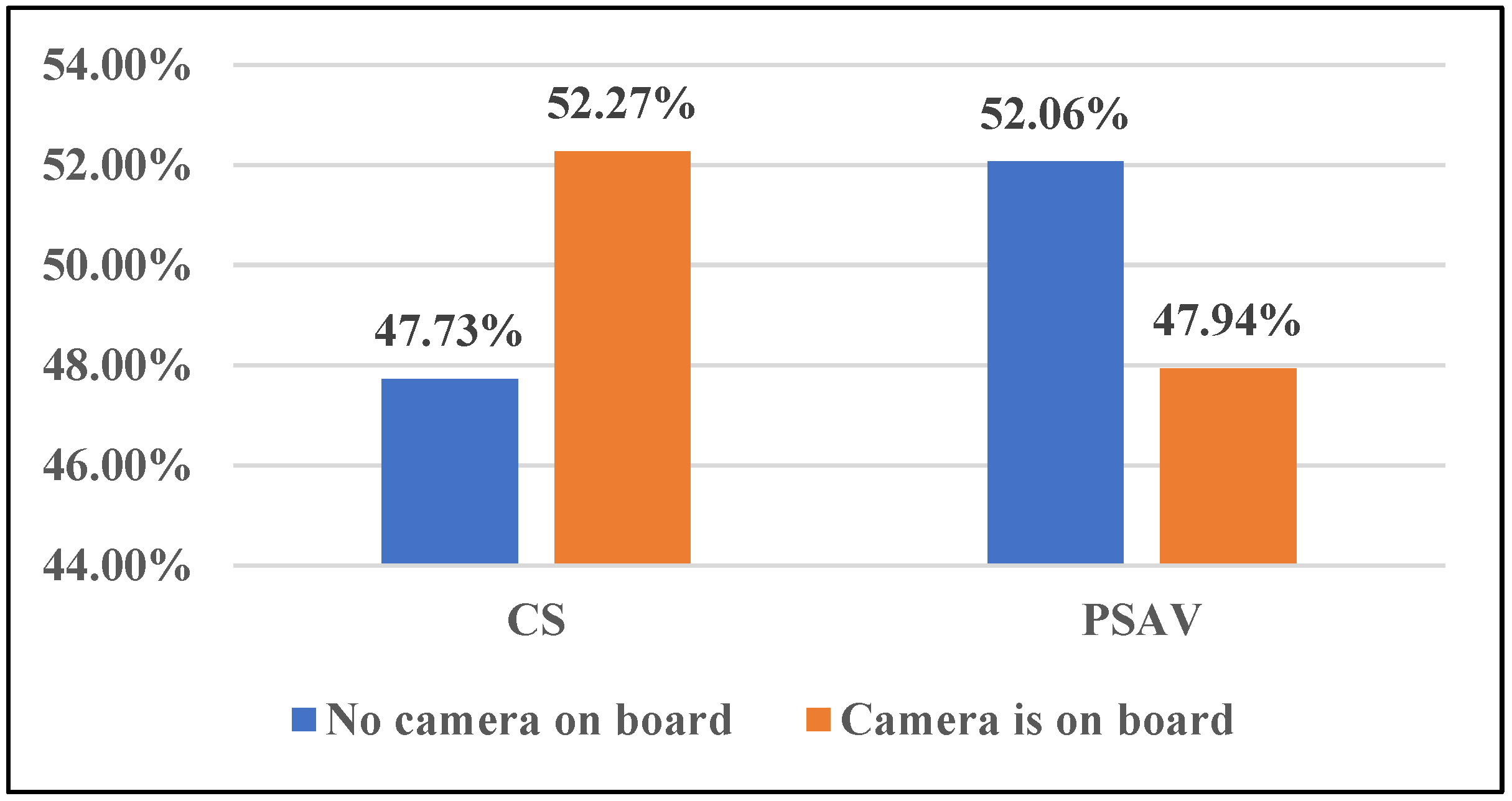

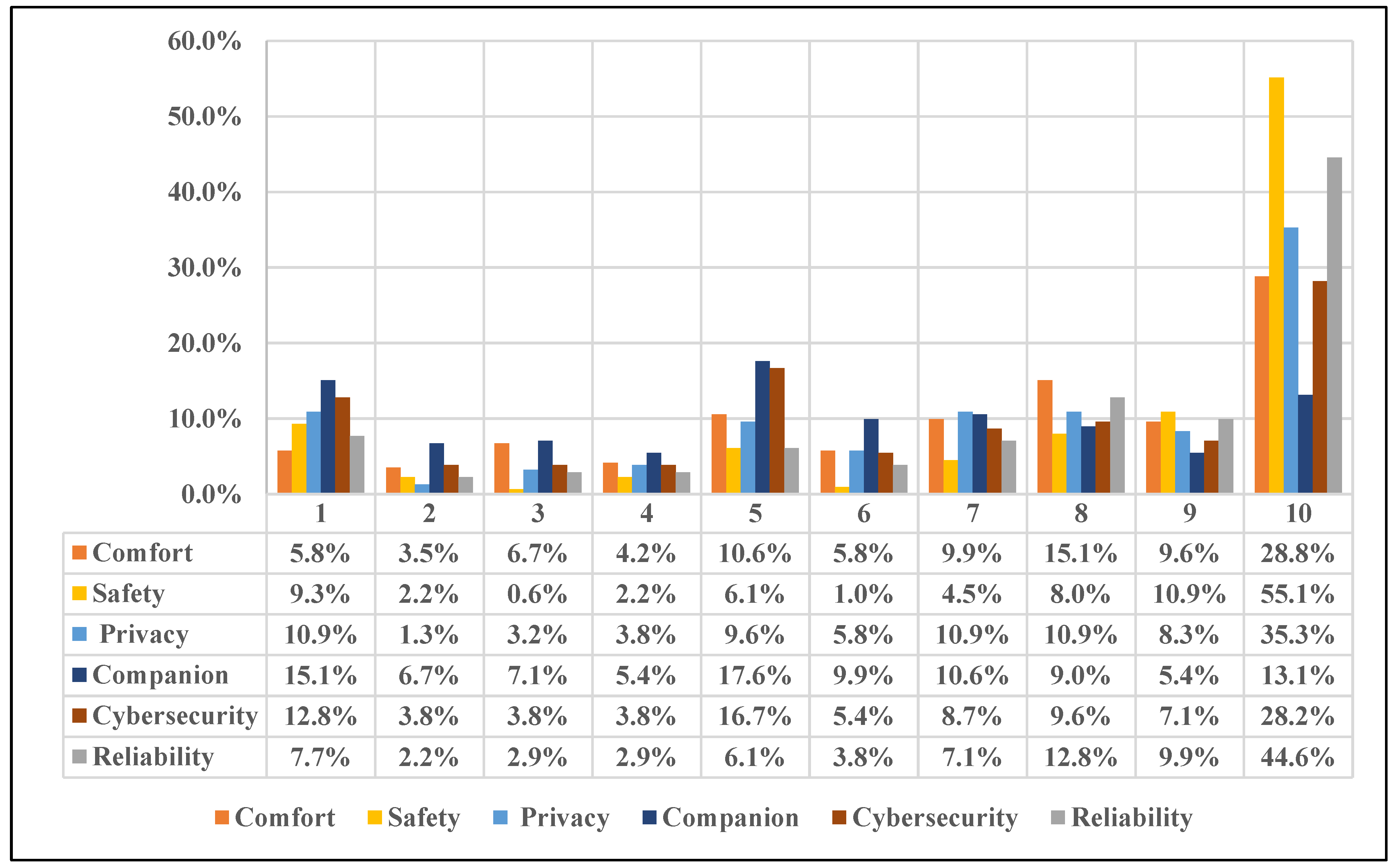

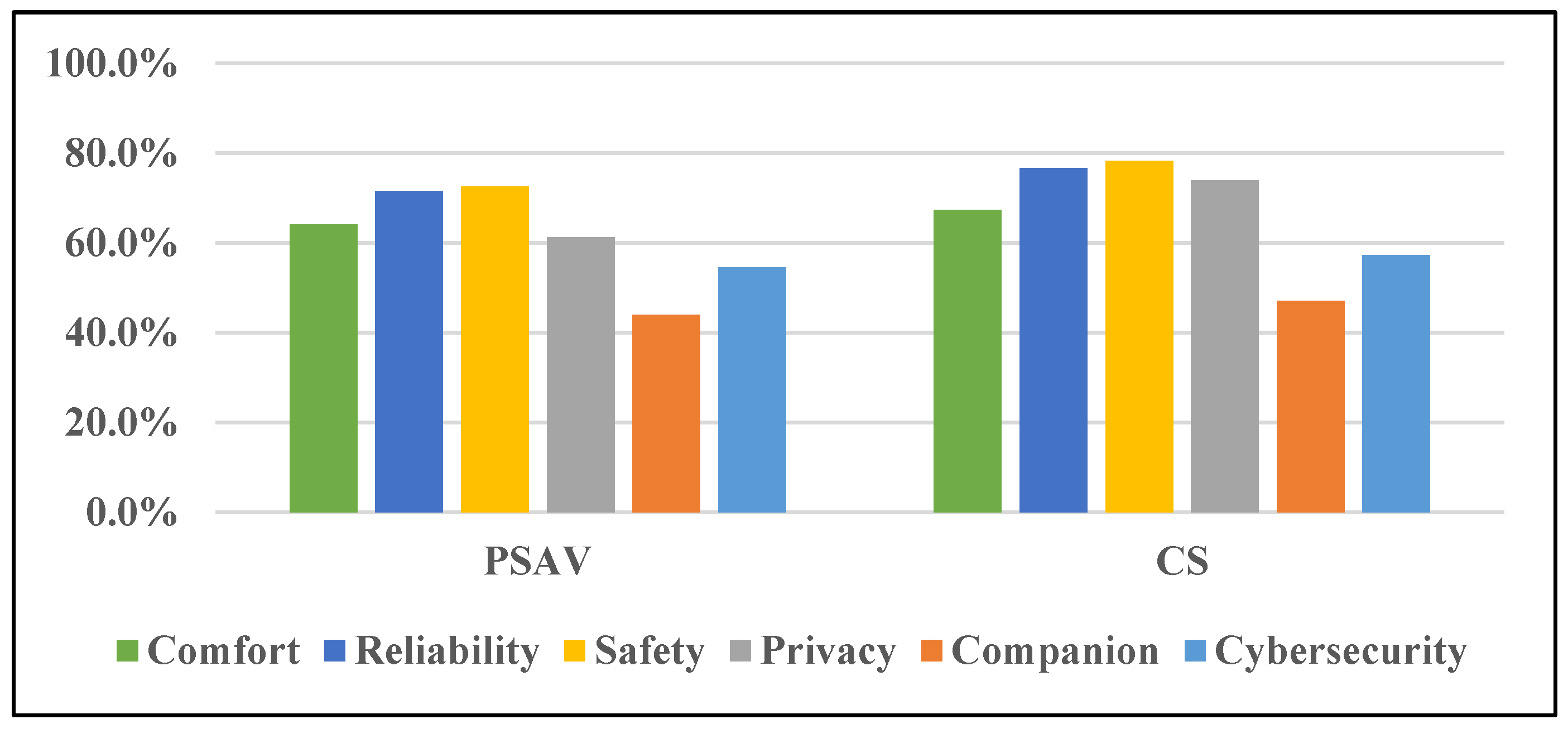

3.1.1. Descriptive Statistics

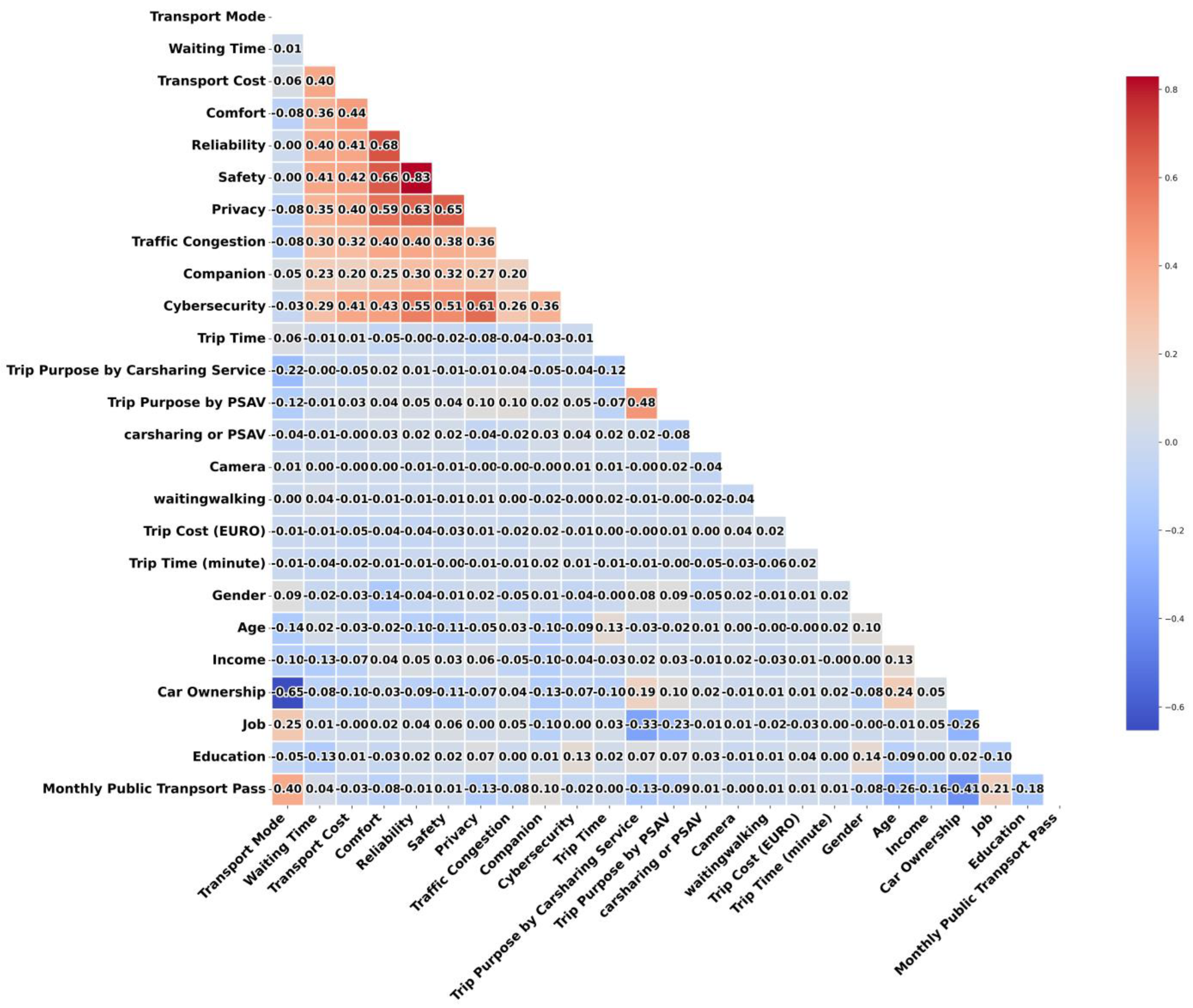

3.1.2. Data Processing

3.1.3. Data Balancing and Model Optimization

3.2. Data Analysis: Model Selection and Training

3.2.1. CatBoost

3.2.2. XGBoost

- signifies the estimated crash severity after the iterations,

- k represents the number of additive trees,

- t denotes the number of iterations,

- corresponds to the kth tree function for variables ,

- represents the predicted response value for the final iteration,

- characterizes the tree function for the ith iteration.

3.2.3. LightGBM

3.2.4. Performance Evaluation Metrics

4. Results and Discussion

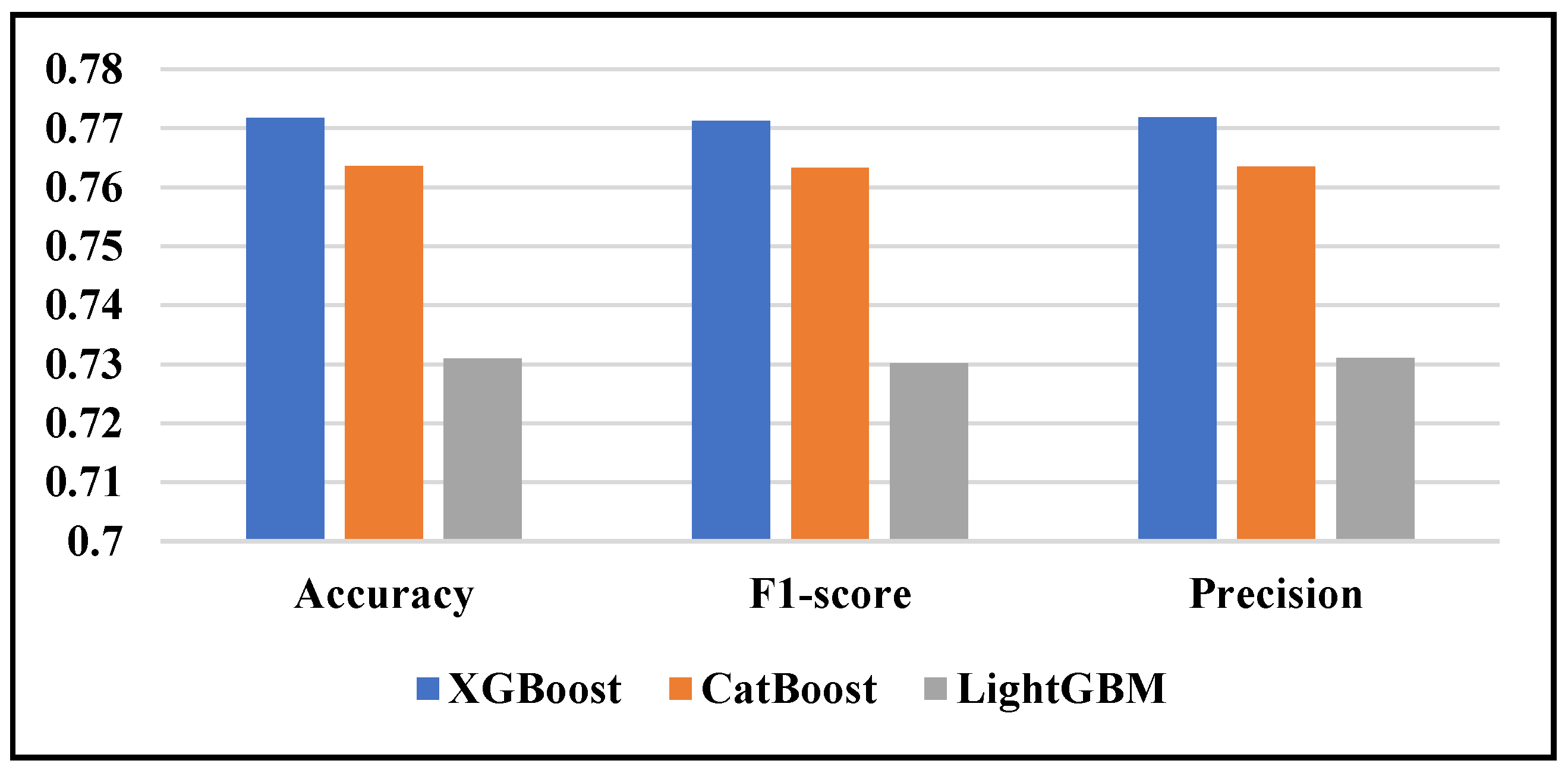

4.1. Model Performance and Comparative Analysis

| XGBoost | CatBoost | LightGBM | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 0.77173913 | 0.763586957 | 0.730978261 |

| F1-Score | 0.771230089 | 0.763255229 | 0.730119138 |

| Precision | 0.771869087 | 0.763478721 | 0.731100159 |

4.2. Classification Metrics

| XGBoost | LightGBM | CatBoost | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS | PSAV | CS | PSAV | CS | PSAV | |

| Precision | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.77 | 0.76 |

| Recall | 0.81 | 0.73 | 0.78 | 0.68 | 0.79 | 0.73 |

| F1-score | 0.79 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.70 | 0.78 | 0.74 |

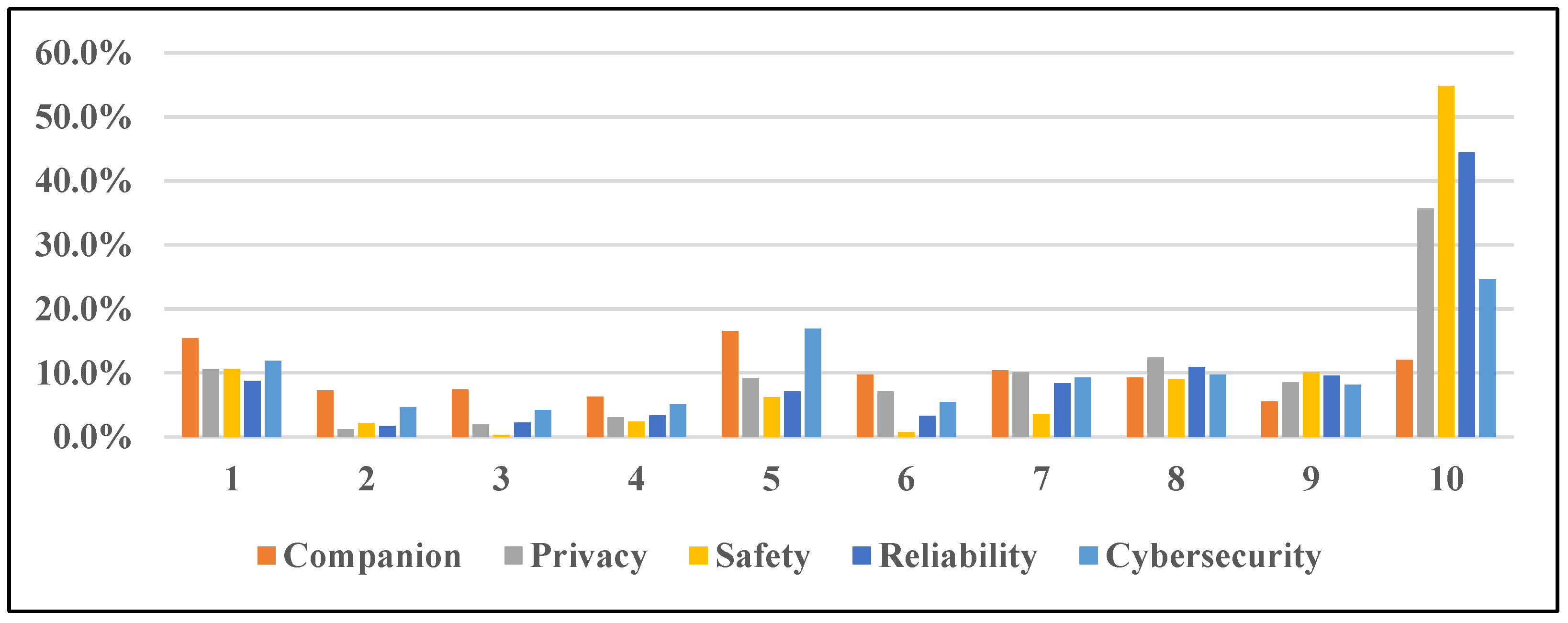

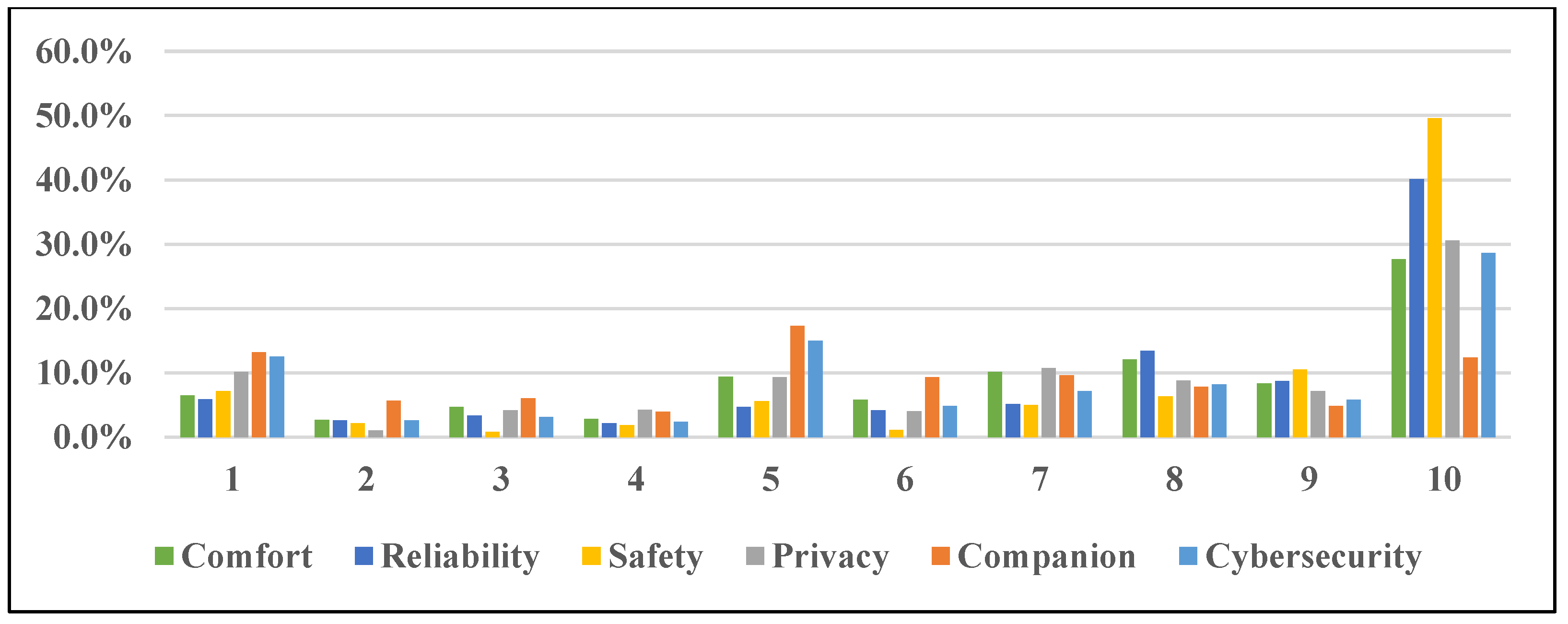

4.3. Feature Importance Analysis

4.4. Limitations and Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sperling, D. Three revolutions: Steering automated, shared, and electric vehicles to a better future; Island Press: 2018.

- Hancock, P.A.; Nourbakhsh, I.; Stewart, J.J.P.o.t.N.A.o.S. On the future of transportation in an era of automated and autonomous vehicles. 2019, 116, 7684–7691.

- Campisi, T.; Severino, A.; Al-Rashid, M.A.; Pau, G.J.I. The development of the smart cities in the connected and autonomous vehicles (CAVs) era: From mobility patterns to scaling in cities. 2021, 6, 100.

- Axsen, J.; Sovacool, B.K.J.T.R.P.D.T.; Environment. The roles of users in electric, shared and automated mobility transitions. 2019, 71, 1–21.

- Hamadneh, J.; Esztergár-Kiss, D. The preferences of transport mode of certain travelers in the age of autonomous vehicle. Journal of Urban Mobility 2023, 3, 100054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbie, M.J.I. Innovation; Infrastructure. Rethinking technology sharing for sustainable growth and development in developing countries. 2021, 936–945. [Google Scholar]

- Luca, O.; Andrei, L.; Iacoboaea, C.; Gaman, F.J.S. Unveiling the hidden effects of automated vehicles on “do no significant harm” components. 2023, 15, 11265.

- Chen, Y.; Li, C.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.M.; Gao, Z.J.n.S.M. ; Transport. The landscape, trends, challenges, and opportunities of sustainable mobility and transport. 2025, 2, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Garus, A.; Mourtzouchou, A.; Suarez, J.; Fontaras, G.; Ciuffo, B.J.S.C. Exploring Sustainable Urban Transportation: Insights from Shared Mobility Services and Their Environmental Impact. 2024, 7, 1199–1220.

- Hou, N.; Shollock, B.; Petzoldt, T.; M’Hallah, R.J.I.J.o.S.T. Qualitative insights into travel behavior change from using private cars to shared cars. 2025, 1-15.

- Roblek, V.; Meško, M.; Podbregar, I.J.S. Impact of car sharing on urban sustainability. 2021, 13, 905.

- Liyanage, S.; Dia, H.; Abduljabbar, R.; Bagloee, S.A.J.S. Flexible mobility on-demand: An environmental scan. 2019, 11, 1262.

- Hasan, U.; Whyte, A.; Al Jassmi, H.J.A.S.I. A review of the transformation of road transport systems: are we ready for the next step in artificially intelligent sustainable transport? 2019, 3, 1.

- Sharma, A.; Zheng, Z.J.A.C.D., Construction, Operation; Impact, F. Connected and automated vehicles: Opportunities and challenges for transportation systems, smart cities, and societies. 2021, 273-296.

- Bathla, G.; Bhadane, K.; Singh, R.K.; Kumar, R.; Aluvalu, R.; Krishnamurthi, R.; Kumar, A.; Thakur, R.; Basheer, S.J.M.I.S. Autonomous vehicles and intelligent automation: Applications, challenges, and opportunities. 2022, 2022, 7632892.

- Chougule, A.; Chamola, V.; Sam, A.; Yu, F.R.; Sikdar, B.J.I.O.J.o.V.T. A comprehensive review on limitations of autonomous driving and its impact on accidents and collisions. 2023, 5, 142–161. [CrossRef]

- Al Mansoori, S.; Al-Emran, M.; Shaalan, K.J.I.J.o.H.C.I. Factors affecting autonomous vehicles adoption: A systematic review, proposed framework, and future roadmap. 2024, 40, 8397–8418.

- Matin, A.; Dia, H.J.J.o.I.; Vehicles, C. Public perception of connected and automated vehicles: Benefits, concerns, and barriers from an Australian perspective. 2024.

- Khan, S.K.; Shiwakoti, N.; Stasinopoulos, P.; Warren, M.J.T.R.P. Cybersecurity Regulations for Automated Vehicles: A Conceptual Model Demonstrating the" Tragedy of the Commons". 2025, 82, 3729–3751.

- Chen, Y.; Khan, S.K.; Shiwakoti, N.; Stasinopoulos, P.; Aghabayk, K.J.R.i.T.B. ; Management. Integrating perceived safety and socio-demographic factors in UTAUT model to explore Australians' intention to use fully automated vehicles. 2024, 56, 101147. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Shiwakoti, N.; Stasinopoulos, P.; Khan, S.K.J.S. State-of-the-art of factors affecting the adoption of automated vehicles. 2022, 14, 6697.

- Bala, H.; Anowar, S.; Chng, S.; Cheah, L.J.T.R. Review of studies on public acceptability and acceptance of shared autonomous mobility services: Past, present and future. 2023, 43, 970–996.

- Patel, R.K.; Etminani-Ghasrodashti, R.; Kermanshachi, S.; Rosenberger, J.M.; Foss, A.J.I.J.o.T.S. ; Technology. Exploring willingness to use shared autonomous vehicles. 2023, 12, 765–778. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X.; Yu, W.; Li, W.; Guo, J.; Chen, X.; Guo, H.; Wang, W.; Chen, T.J.S. Factors affecting the acceptance and willingness-to-pay of end-users: A survey analysis on automated vehicles. 2021, 13, 13272.

- Ullah, I.; Zheng, J.; Ullah, S.; Bhattarai, K.; Almujibah, H.; Alawad, H.J.S. Unraveling the Complex Barriers to and Policies for Shared Autonomous Vehicles: A Strategic Analysis for Sustainable Urban Mobility. 2024, 12, 558.

- Hamiditehrani, S.; Scott, D.M.; Sweet, M.N.J.T.B. ; Society. Shared versus pooled automated vehicles: Understanding behavioral intentions towards adopting on-demand automated vehicles. 2024, 36, 100774. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Wang, L.J.T.o.T.S. Consumer Preferences and Determinants of Transportation Mode Choice Behaviors in the Era of Autonomous Vehicles. 2024, 15, 37–47.

- Sadeghpour, M.; Beyazıt, E.J.T.P. ; Technology. The new frontier of urban mobility: a scenario-based analysis of autonomous vehicles adoption in urban transportation. 2025, 48, 43–66. [Google Scholar]

- Sumitkumar, R.; Al-Sumaiti, A.S.J.R.; Reviews, S.E. Shared autonomous electric vehicle: Towards social economy of energy and mobility from power-transportation nexus perspective. 2024, 197, 114381.

- Püschel, J.; Barthelmes, L.; Kagerbauer, M.; Vortisch, P.J.T.R.R. Comparison of discrete choice and machine learning models for simultaneous modeling of mobility tool ownership in agent-based travel demand models. 2024, 2678, 376–390.

- Hu, B.; Tang, J.; Tong, D.; Zhao, H.J.T.B. ; Society. Revealing spatiotemporal characteristics of EV car-sharing systems: A case study in Shanghai, China. 2024, 36, 100808. [Google Scholar]

- Ghorbani, A.; Nassir, N.; Lavieri, P.S.; Beeramoole, P.B.; Paz, A.J.T. Enhanced utility estimation algorithm for discrete choice models in travel demand forecasting. 2025, 1-28.

- Yu, D.; Li, Z.; Zhong, Q.; Ai, Y.; Chen, W.J.J.o.A.T. Demand Management of Station-Based Car Sharing System Based on Deep Learning Forecasting. 2020, 2020, 8935857.

- Rahman, M.M.; Paul, K.C.; Hossain, M.A.; Ali, G.M.N.; Rahman, M.S.; Thill, J.-C.J.I.A. Machine learning on the COVID-19 pandemic, human mobility and air quality: A review. 2021, 9, 72420–72450.

- Wu, S.; Falk, K.; Myklebust, T.J.W.E.V.J. Beyond Safety: Barriers to Shared Autonomous Vehicle Utilization in the Post-Adoption Phase—Evidence from Norway. 2025, 16, 133.

- Greenblatt, J.B.; Shaheen, S. Automated vehicles, on-demand mobility, and environmental impacts. Current Sustainable/Renewable Energy Reports volume 2015, 2, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, M.; Yamamoto, T. Shared autonomous vehicles: A review considering car sharing and autonomous vehicles. Asian Transport Studies 2018, 5, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamadneh, J.; Hamdan, N.; Mahdi, A. Users’ Transport Mode Choices in the Autonomous Vehicle Age in Urban Areas. Journal of Transportation Engineering, Part A: Systems. 2024, 150, 04023128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, N.J.T.R.I.P. Exploring the future: A meta-analysis of autonomous vehicle adoption and its impact on urban life and the healthcare sector. 2024, 26, 101110.

- Lee, D.; Hess, D.J.J.H.; communications, s.s. Public concerns and connected and automated vehicles: safety, privacy, and data security. 2022, 9, 1–13.

- Naiseh, M.; Clark, J.; Akarsu, T.; Hanoch, Y.; Brito, M.; Wald, M.; Webster, T.; Shukla, P.J.A. ; SOCIETY. Trust, risk perception, and intention to use autonomous vehicles: an interdisciplinary bibliometric review. 2024, 1-21.

- Kyriakidis, M.; Sodnik, J.; Stojmenova, K.; Elvarsson, A.B.; Pronello, C.; Thomopoulos, N.J.S. The role of human operators in safety perception of av deployment—insights from a large european survey. 2020, 12, 9166.

- Stoiber, T.; Schubert, I.; Hoerler, R.; Burger, P.J.T.R.P.D.T. ; Environment. Will consumers prefer shared and pooled-use autonomous vehicles? A stated choice experiment with Swiss households. 2019, 71, 265–282. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, F.; Zheng, Z.; Whitehead, J.; Washington, S.; Perrons, R.K.; Page, L.J.T.R.P.A.P. ; Practice. Preference heterogeneity in mode choice for car-sharing and shared automated vehicles. 2020, 132, 633–650. [Google Scholar]

- Kolarova, V.; Steck, F.; Bahamonde-Birke, F.J. Assessing the effect of autonomous driving on value of travel time savings: A comparison between current and future preferences. Transportation Research Part A: Policy Practice 2019, 129, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamadneh, J.; Esztergár-Kiss, D. The Effects of Multitasking and Tools Carried by Travelers Onboard on the Perceived Trip Time. Journal of Advanced Transportation 2021, 2021, 5597694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.M. Comparing technology acceptance for autonomous vehicles, battery electric vehicles, and car sharing—A study across Europe, China, and North America. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoettle, B.; Sivak, M. A survey of public opinion about connected vehicles in the US, the UK, and Australia. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Connected Vehicles and Expo (ICCVE); 2014; pp. 687–692. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, D.; Dai, D. Public perceptions of self-driving cars: The case of Berkeley, California. In Proceedings of the Transportation research board 93rd annual meeting; 2014; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Megens, I.I.; Schaefer, W.W.; van der Waerden, P.P.; Masselink, P.P. Vehicle Users' Preferences Concerning Automated Driving Implications for transportation and market planning. Eindhoven University of Technology, 2015.

- Payre, W.; Cestac, J.; Delhomme, P. Intention to use a fully automated car: Attitudes and a priori acceptability. Transportation research part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour 2014, 27, 252–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Levine, J.; Zhao, X. Integrating ridesourcing services with public transit: An evaluation of traveler responses combining revealed and stated preference data. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies 2019, 105, 683–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Sekar, A.; Chen, R.; Kim, H.C.; Wallington, T.J.; Williams, E. Impacts of Autonomous Vehicles on Consumers Time-Use Patterns. Challenges 2017, 8, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litman, T. Autonomous vehicle implementation predictions: Implications for transport planning. Transportation Research Board 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lempert, R.; Zhao, J.; Dowlatabadi, H. Convenience, savings, or lifestyle? Distinct motivations and travel patterns of one-way and two-way carsharing members in Vancouver, Canada. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 2019, 71, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornahl, D.; Hülsmann, M. Markets and Policy Measures in the Evolution of Electric Mobility; Springer: 2016.

- Efthymiou, D.; Chaniotakis, E.; Antoniou, C. Factors affecting the adoption of vehicle sharing systems. In Demand for Emerging Transportation Systems; Elsevier: 2020; pp. 189–209.

- Shaheen, S.A.; Schwartz, A.; Wipyewski, K. Policy considerations for carsharing and station cars: Monitoring growth, trends, and overall impacts. Tansportation Research Record 2004, 1887, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciari, F.; Balac, M.; Balmer, M. Modelling the effect of different pricing schemes on free-floating carsharing travel demand: a test case for Zurich, Switzerland. Transportation 2015, 42, 413–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perboli, G.; Caroleo, B.; Musso, S. Car-sharing: Current and potential members behavior analysis after the introduction of the service. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 41st annual computer software and applications conference (COMPSAC); 2017; pp. 771–776. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S. Transportation Mode Choice Behavior in the Era of Autonomous Vehicles: The Application of Discrete Choice Modeling and Machine Learning. Portland State University, 2022.

- Pineda-Jaramillo, J.; Arbeláez-Arenas, Ó.J.J.o.U.P. ; Development. Assessing the performance of gradient-boosting models for predicting the travel mode choice using household survey data. 2022, 148, 04022007. [Google Scholar]

- Shaheen, S.; Bouzaghrane, M.A. Mobility and Energy Impacts of Shared Automated Vehicles: a Review of Recent Literature. Current Sustainable/Renewable Energy Reports 2019, 6, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagnant, D.J.; Kockelman, K.M. The travel and environmental implications of shared autonomous vehicles, using agent-based model scenarios. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies 2014, 40, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenblatt, J.B.; Shaheen, S. Automated vehicles, on-demand mobility, and environmental impacts. Current sustainable/renewable energy reports 2015, 2, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elreedy, D.; Atiya, A.F.J.I.S. A comprehensive analysis of synthetic minority oversampling technique (SMOTE) for handling class imbalance. 2019, 505, 32–64.

- Chen, H.; Cheng, Y.J.I.T.o.I.T.S. Travel mode choice prediction using imbalanced machine learning. 2023, 24, 3795–3808.

- Yang, L.; Shami, A.J.N. On hyperparameter optimization of machine learning algorithms: Theory and practice. 2020, 415, 295–316.

- Alibrahim, H.; Ludwig, S.A. Hyperparameter optimization: Comparing genetic algorithm against grid search and bayesian optimization. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE congress on evolutionary computation (CEC); 2021; pp. 1551–1559. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 22nd acm sigkdd international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining, 2016; pp. 785–794.

- Prokhorenkova, L.; Gusev, G.; Vorobev, A.; Dorogush, A.V.; Gulin, A.J.A.i.n.i.p.s. CatBoost: unbiased boosting with categorical features. 2018, 31.

- Chang, X.; Wu, J.; Liu, H.; Yan, X.; Sun, H.; Qu, Y.J.T.A.T.S. Travel mode choice: a data fusion model using machine learning methods and evidence from travel diary survey data. 2019, 15, 1587–1612.

- Ke, G.; Meng, Q.; Finley, T.; Wang, T.; Chen, W.; Ma, W.; Ye, Q.; Liu, T.-Y. Lightgbm: A highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Yacouby, R.; Axman, D. Probabilistic extension of precision, recall, and f1 score for more thorough evaluation of classification models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the first workshop on evaluation and comparison of NLP systems, 2020; pp. 79–91.

| Section | Features |

| Sociodemographic variables | Gender, age, income, car ownership, job, education |

| Main trip characteristics | Most frequent transport mode, trip length, trip purpose assuming using CS and PSAV |

| Preferred factors during travel | Waiting time, transport cost, comfort, reliability, safety, privacy, traffic congestion, companion onboard, cybersecurity |

| Transport mode choices (i.e., CS and PSAV) | Trip time, trip cost, time to start the trip, availability of onboard camera (i.e., surveillance control) |

| 15-24 | 25-34 | 35-44 | 45-54 | 55-64 | 65+ | |

| CS | 9.5% | 55.9% | 21.9% | 6.0% | 4.6% | 2.1% |

| PSAV | 8.9% | 53.8% | 22.4% | 9.6% | 4.2% | 1.0% |

| Transport Mode | Trip Purpose | ||||

| Education | Home | Shopping | Leisure or others | Work | |

| CS | 8.64% | 7.12% | 13.59% | 16.20% | 54.45% |

| PSAV | 8.42% | 5.82% | 26.25% | 13.48% | 46.03% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).