1. Introduction

Digital image-processing encompasses techniques and algorithms designed to enhance, analyze, and extract semantic information from digital images. This field has become a fundamental tool in various scientific disciplines, particularly medicine. An emerging branch within digital image-processing is the application of machine learning (ML) a sub-field of artificial intelligence that enables systems to recognize complex patterns and make predictions based on image data. These techniques hold vast potential for analysis of medical images, such as those obtained using optical coherence tomography (OCT).

OCT is a noninvasive imaging technique that provides high-resolution visualization of ocular structures, delivering detailed cross-sectional views of the retina and choroid. The integration of spectral-domain OCT and swept-source OCT (SS-OCT) technologies has significantly enhanced the capability to evaluate deep tissues like the choroid, which play a critical role in various ocular and systemic pathologies.

The combination of advanced image-processing techniques and ML algorithms opens up new avenues for in-depth image analysis, enabling identification of potential markers that signal structural alterations, particularly in vascular physiopathology, as characterized by macroangiopathy and microangiopathy resulting from alterations caused by pericyte loss and capillary drop-out. For instance, diabetes mellitus (DM) can lead to microvascular changes that affect both the retinal and choroidal blood vessels, often well before the onset of diabetic retinopathy (DR). [

1]

Recent studies have demonstrated changes in choroidal vascular density and structure in patients with DM who do not yet exhibit DR, underscoring the importance of this layer in evaluating early complications. [

2,

3,

4] Similarly, other systemic diseases, such as neurodegenerative conditions, show vascular wall damage that can be detected using OCT. [

5]

The analysis of OCT B-scans through digital processing enables segmentation of retinal layers, including the choroid, and facilitates the examination of information within regions that share similar image characteristics. This approach allows for the quantification of parameters, such as tissue thickness and the optical density of vascular structures. Considering these advances, our study endeavors to harness the capabilities of AI as applied to ophthalmic imaging. Specifically, we aim to implement an algorithm in a cross-sectional study that seeks to interpret image information derived from OCT B-scans obtained from subjects.

This study focuses on identifying patterns of signal absorption as reflected in semantic differences within the image by detecting changes not visible to clinicians in standard visual inspection of eyes with and without systemic vascular physiopathology. Additionally, it aims to demonstrate that the proposed method exhibits robust intra- and inter-observer repeatability, thus ensuring its reliability and consistency across evaluators and repeated measurements.

2. Materials and Methods

Data Collection

To perform this study, it was necessary to obtain ocular OCT images, specifically B-scans centered on the fovea. The OCT images were obtained from volunteers who had participated in the “Retinal Alterations Diagnosis and OCT” Study approved by the Aragon Research Ethics Committee in previous years; all participants were informed about the study’s details and provided informed consent. Specifically, subjects were obtained from patients referred from the Department of Endocrinology and had been diagnosed with type II DM and healthy subjects were recruited from members of the Department of Ophthalmology and companions of the patients. All volunteers were recruited between 2016 and 2020 and underwent comprehensive ophthalmological examination, including retinal examination using OCT technology, to confirm the absence of ocular pathology. A trained technician captured the retinal OCT images, first utilizing SS-OCT technology and the high-definition-line examination protocol with the Tru-Track eye-tracking technology available on the Triton® (Topcon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) Deep Range Imaging (DRI) SS-OCT device. Secondly, the technician used Spectralis® OCT and the macular line protocol, which employs spectral domain technology and the enhanced deep-imaging system (Heidelberg Engineering, Germany). OCT examination was always performed at the same time of day due to the schedules defined in the study agenda, which made it possible to avoid choroidal changes not attributable to the study subject but to the physiological changes that occur during the day. [

6] An ophthalmologist (examiner 1), involved in the present study, extracted and recompiled OCT B-scan images considered high quality under the OSCAR-IB criteria from the database of previously cohorts of ocular OCT B-scan images taken from DM patients and healthy subjects. To ensure that the examiners in charge of processing the images were blind to the features of the eyes (pathological or healthy), the photos were randomly numbered and exported in TIFF format at a resolution of 1024 × 992 pixels (px). Images from Spectralis® OCT were used to analyze the capability of SpS to detect and define choroidal area limits. For subsequent image-processing to extract optical density information, Triton® OCT B-scan images were used to reduce bias.

Image-Processing Protocol

The Triton® OCT B-scan images extracted were processed using the main kernel of Superpixel Segmentation imaging. The Superpixel method joins pixels with comparable structural qualities to produce clusters with similar meaningful properties, called superpixels. The number of superpixels, the number of iterations, and the regularity of the shape of the detected superpixels are predefined by the specialist and set prior to the following steps. Five supervised semiautomatic phases were performed by a custom Matlab® script (Math Works®). Detailed explanations of superpixel selection and the choroidal region smoothing code are provided below.

Step 1) Image Loading and Enhancement. The image is loaded and sharpened using MATLAB’s imsharpen function, which increases contrast along the boundaries.

Step 2) Superpixel Segmentation. The Superpixel Segmentation function groups pixels into clusters of similar color and texture. The label matrix, L, represents the segmented image, where each pixel is assigned a superpixel identifier. Segmentation minimizes a cost function, E, as follows:

E = Σ Σ ||I(p) - μ_i||² + λ · dist(p, c_i)

where:

- Sᵢ is the set of pixels in superpixel i,

- I(p) represents the intensity or color vector of pixel p,

- μᵢ is the mean intensity or color vector of superpixel i,

- dist(p, cᵢ) is the spatial distance between pixel p and the center cᵢ of superpixel i,

- λ is the compactness parameter controlling color similarity and spatial proximity.

Step 3) Interactive Superpixel Selection. The user interactively selects or deselects superpixels by clicking on the image. A callback function, seleccionar_region, records the selected region IDs. Step 4) Finalizing the Selection. Step 4_1) Generating the Mask of the Selected Area. A binary mask of the selected superpixels is created, where 1 represents selected pixels and 0 represents others. Step 4_2) Morphological Smoothing of the Selected Area. Morphological operations (opening and closing) are applied to smooth the boundaries of the selected area, removing small irregular structures. In mathematical terms:

Erosion: (A ⊖ B)(x, y) = min (x', y')∈B A(x + x', y + y')

Dilation: (A ⊕ B)(x, y) = max (x', y')∈B A(x - x', y - y')

Step 4_3) Calculating the Total Area of the Smoothed Region. The area of the smoothed region is calculated by summing all nonzero pixels in the mask.

Step 5) Visualizations. Three visualizations are created: A) The smoothed region alone. B) The smoothed mask overlaid on the original image with semi-transparency. C) The fluorescent green overlay of the smoothed area.

Precision and Accuracy.

Three separate examiners (E) from different universities each independently processed the entire set of OCT B-scan images. In addition, one of the examiners (E2) repeated processing on different days. Two of the examiners, E1 and E2, were specialists in vision and the ocular system; E3, however, was unaware of the purpose of the work. This latter examiner was only asked to select the areas they considered to be identical. Moreover, E3 had no prior knowledge of vision, the ocular system, or general pathology. Although SpS automatically processes the OCT B-scans, once the areas containing similar information are identified they must be selected manually. A person knowledgeable in this area could therefore falsify selection of identical points if they were aware that it was the choroidal area that needed to be analyzed (superpixel selection Step 4).

Outcomes

To measure the detected structural alterations to the choroid, two metrics were established: choroidal area (CA), which is the total area corresponding to the segmented choroidal region of interest; within this area, choroidal optical image density (COID) was calculated, which is the mean pixel value of the segmented area.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS V.22 software (IBM SPSS Statistics). The normality of the variables in the study was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test (p > 0.05). Since the variables were considered to meet the criteria for normality, subsequent comparative analysis used parametric tests. To explore the correlation between the CA measurements obtained using image-processing with SpS and the Spectralis® OCT device, the Pearson Correlation Coefficient was used. To assess the accuracy of the CA and COID value calculations under the semiautomatic method, inter-observer and intra-observer variability were analyzed using the coefficient of variation (CoV) and the intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC). To evaluate the potential to detect differences between healthy and pathological eyes, CA and COID values obtained from image-processing were subjected to Student's t-test.

3. Results

A total of 110 ocular OCT B-scans obtained from DM patients and 92 images obtained from healthy subjects were recompiled and randomly numbered by E1 before being sent for digital processing. All images were processed using SpS, and CA and COID parameters were obtained from the segment selection performed by the 3 examiners.

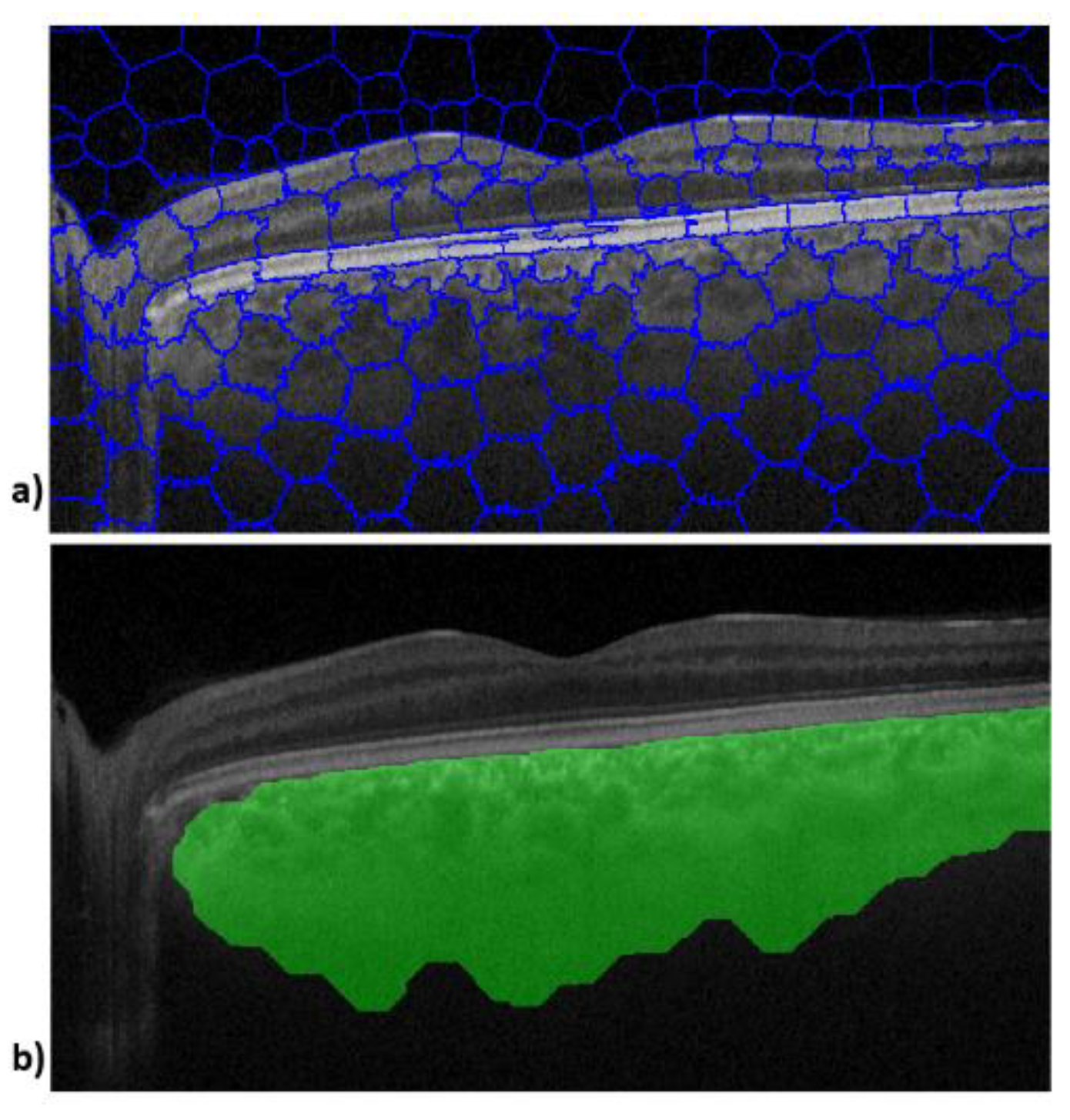

Figure 1 shows the image outputs obtained during processing of an OCT B-scan. The upper image (

Figure 1a) shows SpS and the lower image shows the choroid tissue boundaries defined by the SpS algorithm (

Figure 1b).

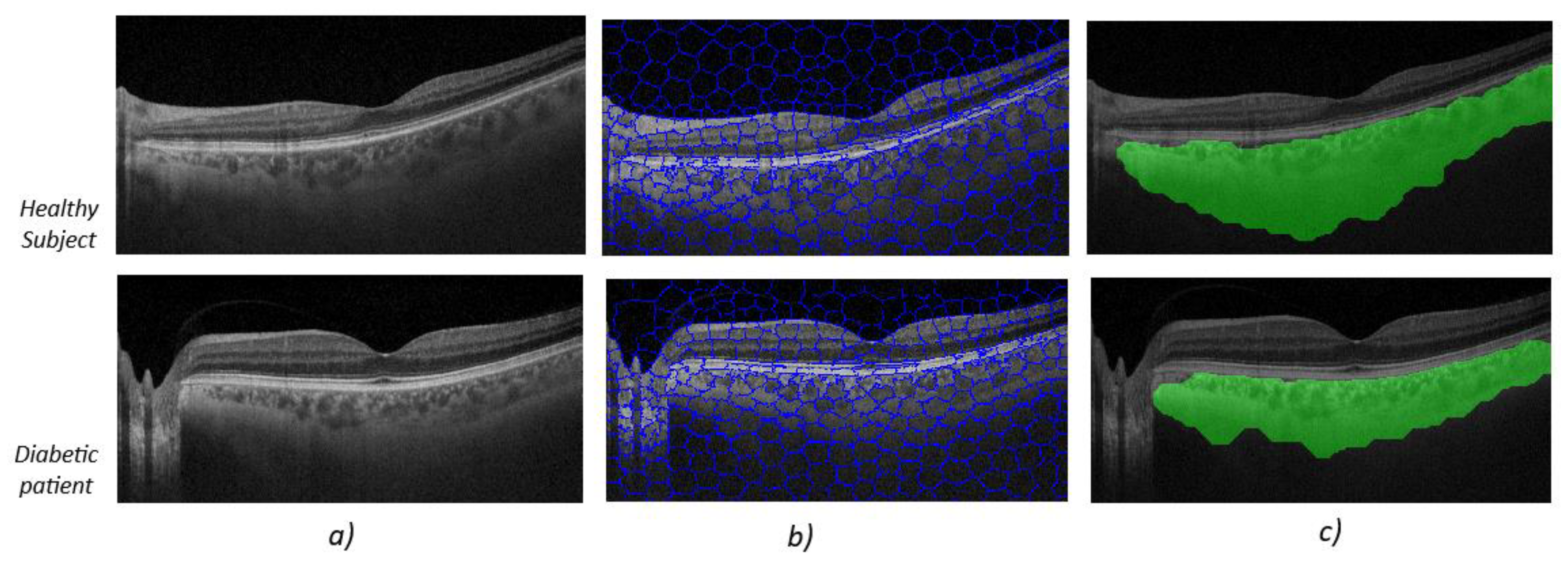

Figure 2 shows the image-processing output for 2 subjects chosen at random in each group. The upper image (

Figure 2) shows the algorithm’s output for a healthy subject, while the lower image shows the algorithm’s output for a diabetes patient (

Figure 2).

At first glance, the OCT B-scans (first column,

Figure 2a) do not show any differences in the area corresponding to the choroidal tissue. It is important to remember that the image properties do not align with what the human eye might perceive as better image quality, such as greater contrast or sharpness. In the second column, the output after applying the SpS which groups together areas of the image with the same semantic information is noticeable. The third column (

Figure 2c) contains the areas defined by SpS that correspond to zones with choroidal tissue.

Image outputs obtained from Superpixel Algorithm processing for one OCT B-scan image. The upper pictures are from healthy subjects and the lower pictures are from diabetic patients. The left column (a) shows OCT B-scan images for both types of subject, the center column (b) shows segments with the same semantic information as defined by the Superpixel Algorithm, and the right column (c) shows choroid delimited tissue.

The analysis using the algorithm-processing method revealed that the parameters were significantly different in eyes from healthy subjects than in those from diabetes patients (p < 0.001). Optical image information, measured as COID, was much lower in diabetic than in healthy eyes (p < 0.001). These results are consistent with those obtained in the study previously conducted in subjects with neurodegenerative disease. [

7]

4. Discussion

Various studies have consistently identified a reduction in choroidal thickness among individuals with DM, regardless of whether they manifest diabetic retinopathy or not. [

2,

4,

8] In this regard, the availability of noninvasive tools with the potential to predict disease progression or facilitate early diagnosis is a crucial development. Such tools could not only aid early detection but could also play a pivotal role in population-wide screening and ongoing monitoring of the disease. Our research group is therefore endeavoring to apply the power of the Superpixel algorithm to choroidal analysis as a noninvasive biomarker for early detection of systemic vascular changes in individuals with DM. Our efforts are founded on compelling scientific evidence that meticulous examination of the choroid allows in-depth understanding of the microvasculature.

This study employed an innovative automated image-segmentation method to delineate the choroidal area and scrutinize choroidal properties represented in OCT images as COID. Notably, this novel parameter has shown potential in vascular tissue evaluation of neurodegenerative patients’ conditions. [

7]

The density observed in optical images is related to the intensity of the light absorbed by the media on which the light is incident. Based on these values, the type of material that passes through light at a given point can be categorized. In a similar vein, our study of OCT images is concerned with the optical density of various structures. This understanding of optical density plays a pivotal role in image analysis and interpretation, allowing us to discern different features and materials. In the field of ophthalmology, the concept of optical image density has found applications in various domains, including anterior segment research. One notable instance is in corneal analysis using topography or OCT, where it has been shown that corneal optical image density exhibits an upward trend with natural aging, corneal degeneration, refractive surgery, and corneal transplants. [

9,

10] Importantly, this increase in optical image density is intrinsically linked to the preservation of corneal transparency, shedding light on the underlying mechanisms at play. Furthermore, the variations in corneal optical density have been associated with spectrum conditions, including keratinocyte inflammatory reactions and stromal fibrosis, emphasizing the role of optical image density as a valuable parameter in understanding the health and dynamics of the cornea. [

9,

10] Emerging studies are initiating exploration of choroidal tissue analysis using OCT images, ushering in a highly promising avenue of research for the early detection of retinal abnormalities. [

11,

12,

13] Nakano et al. found differences in the image density of diabetic subjects, with and without retinopathy, compared to healthy subjects, using a method similar to ours. [

14] In DM patients, vessel walls are altered by chronic hyperglycemia, which leads to loss of pericytes and ischemia of the vascular walls. Ischemia can also trigger fibrosis of the vascular walls in addition to vascular obstruction, neovascularization, or aneurysms. [

15,

16] The vascular change process associated with chronic hyperglycemia could be the reason for the increased optical density observed in OCT images. Significant differences were identified in all the choroidal parameters extracted from B-scans of the DM patients and healthy controls participating in this study: COID and choroidal area.

This method could provide a useful new means of studying choroidal layer alterations applicable to the field of ophthalmology and beyond, to which end we highlight some of the advantages and the potential impact of the evaluated parameters. The ability to identify alterations before retinal signs manifest could be crucial for early intervention and prevention of severe ocular complications. Although this study solely included eyes without diabetic retinopathy, it opens the possibility that the analyzed parameters may become future biomarkers for diabetic retinopathy. Long-term research may help determine if these parameters can predict the development of diabetic retinopathy. Choroidal layer parameters, such as COID, could be used as indicators of systemic vascular damage in DM patients.

The limitations of this study are as follows: 1) The sample size is relatively small given the breadth of diabetic pathophysiology. Only subjects without progression to diabetic retinopathy were included; including a group in which this progression has occurred would allow us to determine whether the tool is useful for predicting the appearance of this complication. 2) It would be useful to analyze subgroups according to treatment received, glycosylated hemoglobin levels, and age ranges. This could be done by increasing the sample size to make these groups acceptable for subgroup analysis and would thus allow us to understand the behavior of choroidal vascular tissue in these scenarios. 3) It would be useful to validate the method in a population different to the one assessed in the study to examine its cost-effectiveness when applied to eyes of different genetic, racial, and environmental origin.

5. Conclusions

A key advantage of this method is its noninvasive technique, making it ideal for use in clinical settings. Additionally, OCT imaging is relatively cost-effective when compared with other diagnostic procedures. In summary, application of this choroidal analysis method shows potential in detection of vascular ocular damage in DM patients and could extend to assessment of vascular damage in other ocular pathologies.

It is also a simple technique that can be implemented in the software of commercially available OCT devices and can be used in daily medical practice or even in population-screening programs or in primary care or endocrinology consultations due to its simplicity and ease of acquisition.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, S.O., F.A., and E.G-M.; methodology, S.O. and E.G-M.; software, F.A.; validation, S.O., V.M. and F.A.; formal analysis, S.O.; investigation, S.O., Ll.P-M. and V.M.; resources, F.A., S.O..; data curation, V.M. and Ll.P-M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.O.; writing—review and editing, E.G-M..; visualization, F.A. and E.G-M.; supervision, F.A. and S.O.; project administration, E.G-M.; funding acquisition, E.G-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.

Funding

This study was supported by Carlos III Health Institute grant PI20/00437, by the Inflammatory Disease Network (RICORS) (RD24/0007/0022) (Carlos III Health Institute), and by the Government of Aragon (PROY B50_24 and groups B23_23R and E44_23R).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee), the Ethics Committee of Aragón for the project “Retinal Alterations Diagnosis and OCT”.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are not publicly available due to confidentiality restrictions; however, they are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would first like to acknowledge the use of the infrastructure at the Department of Ophthalmology at Miguel Servet University Hospital and, second, the funding received: Carlos III Health Institute grants PI17/01726 and PI20/00437, and funding from the Inflammatory Disease Network (RICORS) (RD21/0002/0050) (Carlos III Health Institute). Finally, we would like to thank our external examiner, who is not familiar with ocular structure and pathology, for his collaboration.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CA |

Choroidal Area |

| COID |

Choroid optical image density |

| DM |

Diabetes Mallitus |

| OCT |

Optical Coherence Tomography |

| SpS |

Superpixel Segmentation |

References

- de Asís Bartol-Puyal, F.; Isanta, C.; Calvo, P.; Abadía, B.; Ruiz-Moreno, Ó.; Pablo, L. Macro and microangiopathy related to retinopathy and choroidopathy in type 2 diabetes. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2022, 32, 2412–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satue, M.; Cipres, M.; Melchor, I.; Gil-Arribas, L.; Vilades, E.; Garcia-Martin, E. Ability of Swept source OCT technology to detect neurodegeneration in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus without diabetic retinopathy. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2020, 64, 367–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Martin, E.; Cipres, M.; Melchor, I.; et al. Neurodegeneration in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus without Diabetic Retinopathy. J Ophthalmol. 2019;2019:1825819.

- Wang, W.; Liu, S.; Qiu, Z.; et al. Choroidal Thickness in Diabetes and Diabetic Retinopathy: A Swept Source OCT Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2020, 61, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duering, M.; Biessels, G.J.; Brodtmann, A.; et al. Neuroimaging standards for research into small vessel disease-advances since 2013. Lancet Neurol. 2023, 22, 602–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Cano, A.; Orduna, E.; et al. Choroidal thickness and volume in healthy young white adults and the relationships between them and axial length, ammetropy and sex. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014, 158, 574–83.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otin, S.; Ávila, F.J.; Mallen, V.; Garcia-Martin, E. Detecting Structural Changes in the Choroidal Layer of the Eye in Neurodegenerative Disease Patients through Optical Coherence Tomography Image Processing. Biomedicines. 2023;11(11).

- Xu, J.; Xu, L.; Du, K.F.; et al. Subfoveal choroidal thickness in diabetes and diabetic retinopathy. Ophthalmology. 2013, 120, 2023–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Consejo, A.; Glawdecka, K.; Karnowski, K.; et al. Corneal Properties of Keratoconus Based on Scheimpflug Light Intensity Distribution. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2019, 60, 3197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Consejo, A.; Jiménez-García, M.; Rozema, J.J. Age-Related Corneal Transparency Changes Evaluated With an Alternative Method to Corneal Densitometry. Cornea. 2021, 40, 215–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obadă, O.; Pantalon, A.D.; Rusu-Zota, G.; Hăisan, A.; Lupuşoru, S.I.; Chiseliţă, D. Choroidal Assessment in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Non-Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy by Swept-Source Ocular Coherence Tomography and Image Binarization. Medicina (Kaunas). 2022;58(7).

- Da Silva, M.O.; Chaves, A.E.C.D.; Gobbato, G.C.; Lavinsky, F.; Schaan, B.D.; Lavinsky, D. Early choroidal changes detected by swept-source OCT in type 2 diabetes and their association with diabetic kidney disease. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2022;10(6).

- Orduna-Hospital, E.; Arcas-Carbonell, M.; Sanchez-Cano, A.; Pinilla, I.; Consejo, A. Speckle Contrast as Retinal Tissue Integrity Biomarker in Patients with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus with No Retinopathy. J Pers Med. 2022;12(11).

- Nakano, H.; Hasebe, H.; Murakami, K.; Nakamura, Y.; Fukuchi, T. Choroidal vascular density in diabetic retinopathy assessed with swept-source optical coherence tomography. Retina. 2023, 43, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, P.; Thakku, S.G.; Sabanayagam, C.; et al. Characterization of choroidal morphological and vascular features in diabetes and diabetic retinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2017, 101, 1038–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.B.; Perepelkina, T.; Testi, I.; et al. Imaging-based Assessment of Choriocapillaris: A Comprehensive Review. Semin Ophthalmol. 2023, 38, 405–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).