Submitted:

27 April 2025

Posted:

28 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Culture and Growth Conditions

2.2. Essential Oil of P. longiflora

2.2.1. Preparation of Oil Working Solutions

2.3. Antimicrobial Activity: Minimum Bactericidal Concentration and Sublethal Concentrations.

2.4. Thermal Inactivation Treatments

2.4.1. Estimation of the L. monocytogenes Inactivation Parameters

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

| TLA | Three letter acronym |

| LD | Linear dichroism |

| °C | Degree Celsius |

| µL | microliter |

| Af | Accuracy factor |

| AIC | Akaike Information Criterion |

| Bf | Bias factor |

| BHI | Brain Heart Infusion |

| CFU/mL | Colony Forming Units per milliliter |

| EO | Essential Oils |

| FIV | Fractionated Oregano Essential Oil |

| g/L | grams per liter |

| GRAS | Generally Recognized As Safe |

| h | hours |

| HPP | High Pressure Processing |

| MBC | Minimum Bactericidal Concentration |

| min | minutes |

| mL | milliliter |

| OD | Optical Density |

| OEO | Oregano Essential Oil |

| PEO | Pure Oregano Essential Oil |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| sec | seconds |

| SER | Standard Error of Regression |

| v/v | volume/volume |

References

- Food and Drug Administration. Hazard Analysis and Risk-Based Preventive Controls for Human Food: Draft Guidance for Industry 2024. Available online: https://www.regulations.gov/document/FDA-2016-D-2343-0092 (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Food and Drug Administration. Bad Bug Book-Foodborne Pathogenic Microorganisms and Natural Toxins-Second Edition 2 Bad Bug Book Handbook of Foodborne Pathogenic Microorganisms and Natural Toxins, Washington DC 2022; pp. 99-102.

- Ricci, A., Allende, A., Bolton, D., Chemaly, M., Davies, R., Fernández Escámez, P. S., Girones, R., Herman, L., Koutsoumanis, K., Nørrung, B., Robertson, L., Ru, G., Sanaa, M., Simmons, M., Skandamis, P., Snary, E., Speybroeck, N., Ter Kuile, B., Threlfall, J., … Lindqvist, R. Listeria monocytogenes contamination of ready-to-eat foods and the risk for human health in the EU 2018. EFSA Journal, 16(1):5134. [CrossRef]

- Koutsoumanis, K., Allende, A., Bolton, D., Bover-Cid, S., Chemaly, M., De Cesare, A., Herman, L., Hilbert, F., Lindqvist, R., Nauta, M., Nonno, R., Peixe, L., Ru, G., Simmons, M., Skandamis, P., Suffredini, E., Fox, E., Gosling, R., Gil, B. M., Alvarez-Ordóñez, A. Persistence of microbiological hazards in food and feed production and processing environments 2024. EFSA Journal, 22(1):e8521. [CrossRef]

- CDC. Listeria Outbreak Linked to Leafy Greens – February 2023. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/listeria/outbreaks/monocytogenes-02-23/index.html (accessed on 09 march 2025).

- CDC. Listeria Outbreak Linked to Ice Cream – August 2023. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/listeria/outbreaks/ice-cream-08-23/index.html (accessed on 09 march 2025).

- CDC. Listeria Outbreak Linked to Queso Fresco and Cotija Cheese – February 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/listeria/outbreaks/cheese-02-24/index.html (accessed on 09 march 2025).

- CDC. Listeria Outbreak Linked to Ready-To-Eat Meat and Poultry Products. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/listeria/outbreaks/meat-and-poultry-products-11-24/index.html (accessed on 09 march 2025).

- CDC. More Illnesses and Deaths in Listeria Outbreak Linked to Deli Meats is Reminder to Avoid Recalled Products 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2024/s0828-listeria-outbreak-deli-meats.html (accessed on 09 march 2025).

- CDC. Outbreak Investigation of Listeria monocytogenes: Frozen Supplemental Shakes (February 2025). Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/outbreaks-foodborne-illness/outbreak-investigation-listeria-monocytogenes-frozen-supplemental-shakes-february-2025 (accessed on 09 march 2025).

- Guel-García, P., García De León, F. J., Aguilera-Arreola, G., Mandujano, A., Mireles-Martínez, M., Oliva-Hernández, A., Cruz-Hernández, M. A., Vásquez-Villanueva, J., Rivera, G., Bocanegra-García, V., & Martínez-Vázquez, A. V. Prevalence and Antimicrobial Resistance of Listeria monocytogenes in Different Raw Food from Reynosa, Tamaulipas, Mexico, Foods 2024, 13(11). [CrossRef]

- Matle, I., Mbatha, K. R., & Madoroba, E.. A review of listeria monocytogenes from meat and meat products: Epidemiology, virulence factors, antimicrobial resistance, and diagnosis. Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Research 2020, 87(1), 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Hong, H., Yang, S. M., Kim, E., Kim, H. J., & Park, S. H. Comprehensive metagenomic analysis of stress-resistant and -sensitive Listeria monocytogenes. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2023, 107(19), 6047–6056. [CrossRef]

- Labidi, S., Jánosity, A., Yakdhane, A., Yakdhane, E., Surányi, B., Mohácsi-Farkas, C., & Kiskó, G. Effects of pH, sodium chloride, and temperature on the growth of Listeria monocytogenes biofilms. Acta Alimentaria 2023, 52(2), 270–280. [CrossRef]

- Mahgoub, S. A., El-Mekkawy, R. M., Abd El-Hack, M. E., El-Ghareeb, W. R., Suliman, G. M., Alowaimer, A. N., & Swelum, A. A. Inactivation of Listeria monocytogenes in ready-to-eat smoked turkey meat by combination with packaging atmosphere, oregano essential oil and cold temperature. AMB Express 2019, 9(1). [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, R., Ferreira, V., Brandão, T. R. S., Palencia, R. C., Almeida, G., & Teixeira, P. Persistent and non-persistent strains of Listeria monocytogenes: A focus on growth kinetics under different temperature, salt, and pH conditions and their sensitivity to sanitizers. Food Microbiology 2016, 57, 103–108. [CrossRef]

- Yue, S., Liu, Y., Wang, X., Xu, D., Qiu, J., Liu, Q., & Dong, Q. Modeling the effects of the preculture temperature on the lag phase of Listeria monocytogenes at 25°c. Journal of Food Protection 2019, 82(12), 2100–2107. [CrossRef]

- Wei, J., Ismael, M., Huang, M., Han, T., & Zhong, Q. The bactericidal effects of combined sterilization methods on Listeria monocytogenes and the application in prepared salads, Elsevier 2025 preprint article: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5102418.

- Ghabraie, M., Vu, K. D., Huq, T., Khan, A., & Lacroix, M.. Antilisterial effects of antibacterial formulations containing essential oils, nisin, nitrite and organic acid salts in a sausage model. Journal of Food Science and Technology 2016. 53, 2625–2633. [CrossRef]

- Mani-López, E., García, H. S., & López-Malo, A. Organic acids as antimicrobials to control Salmonella in meat and poultry products. Food Research International 2012, 45(2), 713–721. [CrossRef]

- Puvača, N., Milenković, J., Galonja Coghill, T., Bursić, V., Petrović, A., Tanasković, S., Pelić, M., Ljubojević Pelić, D., & Miljković, T. Antimicrobial activity of selected essential oils against selected pathogenic bacteria: In vitro study. Antibiotics 2021. 10(5). [CrossRef]

- Targino de Souza Pedrosa, G., Pimentel, T. C., Gavahian, M., Lucena de Medeiros, L., Pagán, R., & Magnani, M. The combined effect of essential oils and emerging technologies on food safety and quality. LWT 2021. 147. [CrossRef]

- Vidaković Knežević S., Knežević S., Vranešević J., Kravić S., Lakićević B., Kocić-Tanackov S., Karabasil N. Effects of Selected Essential Oils on Listeria monocytogenes in Biofilms and in a Model Food System. Foods 2023. May 1;12(10). [CrossRef]

- Tejada-Muñoz, S., Cortez, D., Rascón, J., Chavez, S. G., Caetano, A. C., Díaz-Manchay, R. J., Sandoval-Bances, J., Huyhua-Gutierrez, S., Gonzales, L., Chenet, S. M., & Tapia-Limonchi, R. Antimicrobial Activity of Origanum vulgare Essential Oil against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17(11). [CrossRef]

- Pinto, L., Cervellieri, S., Netti, T., Lippolis, V., & Baruzzi, F. Antibacterial Activity of Oregano (Origanum vulgare L.) Essential Oil Vapors against Microbial Contaminants of Food-Contact Surfaces. Antibiotics 2024, 13(4). [CrossRef]

- Maggio, F., Rossi, C., Chaves-Lópe, C., Valbonetti, L., Desideri, G., Paparella, A., & Serio, A. A single exposure to a sublethal concentration of Origanum vulgare essential oil initiates response against food stressors and restoration of antibiotic susceptibility in Listeria monocytogenes. Food Control 2022, 132. [CrossRef]

- Cortés Sánchez, A. D. J., Guzmán Robles, M. L., Garza Torres, R., Espinosa Chaurand, L. D., & Diaz Ramírez, M. Food Safety, Fish and Listeriosis. Turkish Journal of Agriculture - Food Science and Technology 2019, 7(11), 1908–1916. [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Díaz, E., Martínez-Chávez, L., Gutiérrez-González, P., Pérez-Montaño, J. A., Rodríguez-García, M. O., & Martínez-Gonzáles, N. E. Effect of storage temperature and time on the behavior of Salmonella, Listeria monocytogenes, and background microbiota on whole fresh avocados (Persea americana var Hass). International Journal of Food Microbiology 2022, 369. [CrossRef]

- Márquez-González, M., Osorio, L. F., Velásquez-Moreno, C. G., & García-Lira, A. G. Thermal Inactivation of Salmonella enterica and Listeria monocytogenes in Quesillo Manufactured from Raw Milk. International Journal of Food Science 2022. [CrossRef]

- Rubio Lozano, S. M., Martínez Bruno, F. J., Hernández Castro, R., Bonilla Contreras, C., Danilo Méndez Medina, R., Núñez Espinosa, F. J., Echeverry, A. Detection of Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella and Yersinia enterocolitica in beef at points of sale in Mexico. In RES Rev Mex Cienc Pecu 2013. 4(1). pp. 107-115.

- Rubio Ortega A, Guinoiseau E, Poli JP, Quilichini Y, de Rocca Serra D, del Carmen Travieso Novelles M, Espinosa Castaño I., Pino Pérez O., Berti L. The Primary Mode of Action of Lippia graveolens Essential Oil on Salmonella enterica subsp. Enterica Serovar Typhimurium. Microorganisms. 2023 Dec 1;11(12). [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Nieblas M., Robles-Burgueño M., Acedo-Félix E., González-León A., Morales-Trejo A., Vázquez-Moreno L. Chemical Composition and Antimicrobial Activity of Oregano (Lippia palmeri S. Wats) Essential Oil. Rev Fitotec Nex. 2011; 34 (1); 11-17.

- Mora-Zúñiga, A. E., Treviño-Garza, M. Z., Amaya Guerra, C. A., Galindo Rodríguez, S. A., Castillo, S., Martínez-Rojas, E., Rodríguez-Rodríguez, J., & Báez-González, J. G. Comparison of Chemical Composition, Physicochemical Parameters, and Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activity of the Essential Oil of Cultivated and Wild Mexican Oregano Poliomintha longiflora Gray. Plants 2022, 11(14). [CrossRef]

- de Rostro-Alanis, M. J., Báez-González, J., Torres-Alvarez, C., Parra-Saldívar, R., Rodriguez-Rodriguez, J., & Castillo, S. Chemical composition and biological activities of oregano essential oil and its fractions obtained by vacuum distillation. Molecules 2019. 24(10). [CrossRef]

- Levario-Gómez A, Ávila-Sosa R, Gutiérrez-Méndez N, López-Malo A, Nevárez-Moorillón GV. Modeling the Combined Effect of pH, Protein Content, and Mexican Oregano Essential Oil Against Food Spoilage Molds. Front Sustain Food Syst. 2020 4:34. [CrossRef]

- Zapién-Chavarría, K. A., Plascencia-Terrazas, A., Venegas-Ortega, M. G., Varillas-Torres, M., Rivera-Chavira, B. E., Adame-Gallegos, J. R., González-Rangel, M. O., & Nevárez-Moorillón, G. V. Susceptibility of multidrug-resistant and biofilm-forming uropathogens to Mexican oregano essential oil. Antibiotics 2019, 8(4). [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Hernández, K., Sosa-Morales, M. E., Cerón-García, A., & Gómez-Salazar, J. A. Physical, Chemical and Sensory Changes in Meat and Meat Products Induced by the Addition of Essential Oils: A Concise Review. In Food Reviews International 2021. 39(4), 2027–2056. Taylor and Francis Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Agregán, R., Munekata, P. E. S., Zhang, W., Zhang, J., Pérez-Santaescolástica, C., & Lorenzo, J. M. High-pressure processing in inactivation of Salmonella spp. in food products. In Trends in Food Science and Technology 2021. 107, 31–37. [CrossRef]

- Soni, A., Bremer, P., & Brightwell, G. A Comprehensive Review of Variability in the Thermal Resistance (D-Values) of Food-Borne Pathogens—A Challenge for Thermal Validation Trials. Foods 2022. 11(24). MDPI. [CrossRef]

- Dogruyol, H., Mol, S., & Cosansu, S.. Increased thermal sensitivity of Listeria monocytogenes in sous-vide salmon by oregano essential oil and citric acid. Food Microbiology 2020. 90. [CrossRef]

- Juneja, V. K., Huang, L., & Yan, X. Thermal inactivation of foodborne pathogens and the USDA pathogen modeling program. Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry 2011, 106(1), 191–198. [CrossRef]

- Siroli, L., Patrignani, F., Gardini, F., & Lanciotti, R. Effects of sub-lethal concentrations of thyme and oregano essential oils, carvacrol, thymol, citral and trans-2-hexenal on membrane fatty acid composition and volatile molecule profile of Listeria monocytogenes, Escherichia coli and Salmonella enteritidis. Food Chemistry 2015, 182, 185–192. [CrossRef]

- Stavropoulou, E., & Bezirtzoglou, E. Predictive modeling of microbial behavior in food. Foods 2019. 8(12). MDPI. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Rodríguez, F. & Valero, A. Application of Predictive Models in Quantitative Risk Assessment and Risk Management. In: Harter RW, ed. Predictive Microbiology in Foods. Springer New York, Heidelberg, Dordrecht, London 2013. p.87-97.

- Sánchez García, E.; Torres-Alvarez, C.; Morales Sosa, E.G.; Pimentel-González, M.; Villarreal Treviño, L.; Amaya Guerra, C.A.; Castillo, S. & Rodríguez Rodríguez, J. Essential Oil of Fractionated Oregano as Motility Inhibitor of Bacteria Associated with Urinary Tract Infections. Antibiotics 2024, 13(7), 665. [CrossRef]

- Possas A, Posada-Izquierdo GD, Pérez-Rodríguez F, Valero A, García-Gimeno RM, Duarte MCT. Application of predictive models to assess the influence of thyme essential oil on Salmonella Enteritidis behaviour during shelf life of ready-to-eat turkey products. Int J Food Microbiol. 2017 Jan 2;240:40–6. [CrossRef]

- Lazou, T.P. & Chaintoutis, S.C. Comparison of disk diffusion and broth microdilution methods for antimicrobial susceptibility testing of Campylobacter isolates of meat origin. J. Microbiol. Methods 2023, 204, 106649. [CrossRef]

- Castillo, S., Dávila-Aviña, J., Heredia, N., & Garcia, S. Antioxidant activity and influence of Citrus byproduct extracts on adherence and invasion of Campylobacter jejuni and on the relative expression of cadF and ciaB. Food Science and Biotechnology 2017. 26(2), 453–459. [CrossRef]

- Miller, F. A., Gil, M. M., Brandão, T. R. S., Teixeira, P., & Silva, C. L. M. Sigmoidal thermal inactivation kinetics of Listeria innocua in broth: Influence of strain and growth phase. Food Control 2009, 20(12), 1151–1157. [CrossRef]

- Garre, A., González-Tejedor, G. A., Aznar, A., Fernández, P. S., & Egea, J. A. Mathematical modelling of the stress resistance induced in Listeria monocytogenes during dynamic, mild heat treatments. Food Microbiology 2019. 84. [CrossRef]

- Possas, A., Pérez-Rodríguez, F., Valero, A., Rincón, F., & García-Gimeno, R. M. Mathematical approach for the Listeria monocytogenes inactivation during high hydrostatic pressure processing of a simulated meat medium. Innovative Food Science and Emerging Technologies 2018. 47, 271–278. [CrossRef]

- Garre, A. biogrowth & bioinactivation-making predictive microbiology a bit easier IAFP Software Fair Series 2022.

- Albert, I., Mafart, P. A modified Weibull model for bacterial inactivation. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2005. 100, 197-211. [CrossRef]

- Bigelow, W. D. The Logarithmic Nature of Thermal Death Time Curves. In Jour. Infec. Dis. 1921, 29, 528-536.

- Huertas, J.-P., Ros-Chumillas, M., Garre, A., Fernández, P. S., Aznar, A., Iguaz, A., Esnoz, A., & Palop, A. Impact of Heating Rates on Alicyclobacillus acidoterrestris Heat Resistance under Non-Isothermal Treatments and Use of Mathematical Modelling to Optimize Orange Juice Processing. Foods 2021.10, 1496. [CrossRef]

- Buzrul S. The Weibull Model for Microbial Inactivation. Vol. 14, Food Engineering Reviews. Springer; 2022. p. 45–61.

- Valenzuela-Melendres M, Peña-Ramos EA, Juneja VK, Camou JP, Cumplido-Barbeitia G. Effect of grapefruit seed extract on thermal inactivation of Listeria monocytogenes during sous-vide processing of two marinated Mexican meat entrées. J Food Prot. 2016 Jul 1;79(7):1174–80.

- Zakrzewski A, Gajewska J, Chajęcka-Wierzchowska W, Zadernowska A. Effect of sous-vide processing of fish on the virulence and antibiotic resistance of Listeria monocytogenes. NFS Journal. 2023 Jun 1;31:155–61.

- Salazar JK, Fay ML, Fleischman G, Khouja BA, Stewart DS, Ingram DT. Inactivation kinetics of Listeria monocytogenes and Salmonella enterica on specialty mushroom garnishes based on ramen soup broth temperature. Front Microbiol. 2024;15.

- Kutner, M. H. ., Nachtsheim, Chris., Neter, John., & Li, William. Applied linear statistical models; 5th edition; McGraw-Hill Irwin, New York, 2005. pp. 15-23.

- Portet, S. A primer on model selection using the Akaike Information Criterion. Infectious Disease Modelling 2020, 5, 111–128. [CrossRef]

- Tarlak, F. The Use of Predictive Microbiology for the Prediction of the Shelf Life of Food Products. Foods 2023, Vol. 12, Issue 24. [CrossRef]

- Pouillot, R., Kiermeier, A., Guillier, L., Cadavez, V., & Sanaa, M. Updated Parameters for Listeria monocytogenes Dose–Response Model Considering Pathogen Virulence and Age and Sex of Consumer. Foods 2024, 13(5). [CrossRef]

- Milkievicz, T., Badia, V., Souza, V. B., Longhi, D. A., Galvão, A. C., & da Silva Robazza, W. Development of a general model to describe Salmonella spp. growth in chicken meat subjected to different temperature profiles. Food Control 2020, 112. [CrossRef]

- Dudek-Wicher, R., Paleczny, J., Kowalska-Krochmal, B., Szymczyk-Ziółkowska, P., Pachura, N., Szumny, A., & Brożyna, M. Activity of liquid and volatile fractions of essential oils against biofilm formed by selected reference strains on polystyrene and hydroxyapatite surfaces. Pathogens 2021, 10(5). [CrossRef]

- Guo, P., Li, Z., Cai, T., Guo, D., Yang, B., Zhang, C., Shan, Z., Wang, X., Peng, X., Liu, G., Shi, C., Alharbi, M., & Alasmari, A. F. Inhibitory effect and mechanism of oregano essential oil on Listeria monocytogenes cells, toxins, and biofilms. Microbial Pathogenesis 2024, 194. [CrossRef]

- Bakkali M., Arakrak A., Laglaoui A., D. Evaluation of the Antibacterial Activity of Essential Oils Against E. coli Isolated From Rabbits. In Iraqi Journal of Agricultural Sciences 2022. 2022:53 (4), 802-809.

- Fang, T., Wu, Y., Xie, Y., Sun, L., Qin, X., Liu, Y., Li, H., Dong, Q., & Wang, X. Inactivation and Subsequent Growth Kinetics of Listeria monocytogenes After Various Mild Bactericidal Treatments. Frontiers in Microbiology 2021. 12. [CrossRef]

- Shi Y, Tang J, Yue T, Rasco B, Wang S. Pasteurizing Cold Smoked Salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka): Thermal Inactivation Kinetics of Listeria monocytogenes and Listeria innocua. Journal of Aquatic Food Product Technology. 2015 Oct 3;24(7):712–22.

- Li C, Huang L, Hwang CA. Effect of temperature and salt on thermal inactivation of Listeria monocytogenes in salmon roe. Food Control. 2017 Mar 1;73:406–10.

- Moura-Alves M, Gouveia AR, de Almeida JMMM, Monteiro-Silva F, Silva JA, Saraiva C. Behavior of Listeria monocytogenes in beef Sous vide cooking with Salvia officinalis L. essential oil, during storage at different temperatures. LWT. 2020 Oct 1;132.

- Wang Y, Li X, Lu Y, Wang J, Suo B. Synergistic effect of cinnamaldehyde on the thermal inactivation of Listeria monocytogenes in ground pork. Food Science and Technology International. 2020 Jan 1;26(1):28–37.

- Kamdem SS, Belletti N, Magnani R, Lanciotti R, Gardini F. Effects of carvacrol, (E)-2-hexenal, and citral on the thermal death kinetics of Listeria monocytogenes. J Food Prot. 2011 Dec;74(12):2070–8.

- Guevara L, Antolinos V, Palop A, Periago PM. Impact of Moderate Heat, Carvacrol, and Thymol Treatments on the Viability, Injury, and Stress Response of Listeria monocytogenes. Biomed Res Int. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Arioli S, Montanari C, Magnani M, Tabanelli G, Patrignani F, Lanciotti R, Mora D., Gardini F. Modelling of Listeria monocytogenes Scott A after a mild heat treatment in the presence of thymol and carvacrol: Effects on culturability and viability; Journal of Food Engineering. Elsevier Ltd; 2019. Vol. 240. p. 73–82.

- Essia Ngang JJ, Nyegue MA, Ndoye FC, Tchuenchieu Kamgain AD, Sado Kamdem SL, Lanciotti R, Gardini F., Etoa F-X. Characterization of Mexican coriander (Eryngium foetidum) essential oil and its inactivation of Listeria monocytogenes in vitro and during mild thermal pasteurization of pineapple juice. J Food Prot. 2014 Mar;77(3):435–43.

- Juneja VK, Garcia-Dávila J, Lopez-Romero JC, Pena-Ramos EA, Camou JP, Valenzuela-Melendres M. Modeling the effects of temperature, sodium chloride, and green tea and their interactions on the thermal inactivation of Listeria monocytogenes in Turkey. J Food Prot. 2014 Oct 1;77(10):1696–702.

- Butler, F., Hunt, K., Redmond, G., dOnofrio, F., Barron, U. G., Fernandes, S., Cadavez, V., Iannetti, L., Centorotola, G., Pomilio, F., Diaz, A. V., Rodríguez, F. P., & Luque, O. M. B. Application of novel predictive microbiology techniques to shelf-life studies on Listeria monocytogenes in ready-to-eat foods (ListeriaPredict). EFSA Supporting Publications 2023. 20(12). [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Soto, M., Medrano-Félix, J., Ibarra-Rodríguez, J., Martínez-Urtaza, J., Chaidez, Q., & Castro-del Campo, N. The last 50 years of Salmonella in Mexico: Sources of isolation and factors that influence its prevalence and diversity. Bio Ciencias 2019. 6(SPE). [CrossRef]

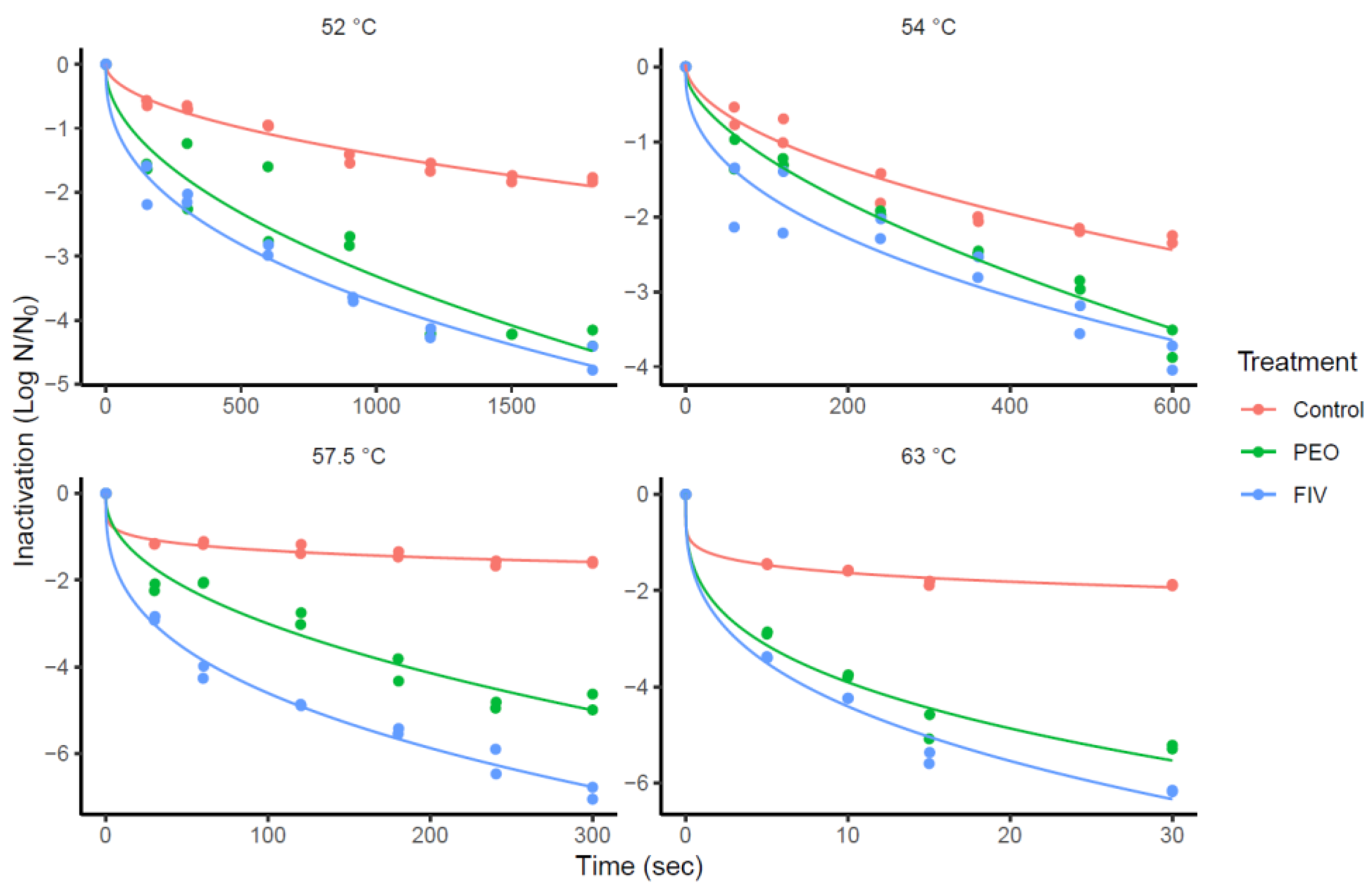

| Weibull-Mafart | Bigelow | ||||||||

| Group | T (°C) | RMSE | Loglik | AIC | Af /Bf | RMSE | Loglik | AIC | Af/Bf |

| Control | 52 | 0.10 | 42.70 | -81.40 | 1.01/0.99 | 0.20 | 22.36 | -42.72 | 1.02/1.00 |

| 54 | 0.16 | 24.40 | -44.80 | 1.02/1.00 | 0.29 | 13.30 | -24.60 | 1.04/1.00 | |

| 57.5 | 0.08 | 47.44 | -90.88 | 1.01/1.00 | 0.37 | 11.92 | -21.84 | 1.04/1.00 | |

| 63 | 0.06 | 46.21 | -88.42 | 1.01/0.99 | 0.48 | 5.35 | -8.70 | 1.07/1.00 | |

| PEO | 52 | 0.42 | 10.36 | -16.72 | 1.07/1.00 | 0.55 | 7.57 | -13.14 | 1.09/1.00 |

| 54 | 0.18 | 22.73 | -41.46 | 1.02/1.00 | 0.30 | 14.33 | -26.66 | 1.05/1.01 | |

| 57.5 | 0.33 | 10.96 | -17.92 | 1.07/1.00 | 0.62 | 6.47 | -10.94 | 1.45/1.42 | |

| FIV | 63 | 0.34 | 11.06 | -18.12 | 1.06/1.00 | 1.00 | 2.52 | -3.04 | 1.26/0.99 |

| 52 | 0.20 | 19.14 | -34.28 | 1.06/1.03 | 0.61 | 6.22 | -10.44 | 1.12/1.02 | |

| 54 | 0.33 | 11.55 | -19.10 | 1.05/1.01 | 0.51 | 8.35 | -14.70 | 1.06/1.00 | |

| 57.5 | 0.20 | 19.50 | -35.00 | 1.10/0.98 | 1.04 | 4.14 | -6.28 | 1.30/0.94 | |

| 63 | 0.24 | 11.94 | -19.88 | 0.99/1.07 | 1.11 | 2.28 | -2.56 | 1.39/0.95 | |

| Control | PEO | FIV | ||||

| Temp (°C) | δ(min) | p | δ(min) | p | δ(min) | p |

| 52 | 8.470 ± 1.510 | 0.51 | 1.750 ± 1.050 | 0.52 | 0.640 ± 0.240 | 0.40 |

| 54 | 1.800 ± 0.500 | 0.53 | 1.350 ± 0.350 | 0.61 | 0.540 ± 0.350 | 0.44 |

| 57.5 | 0.330 ± 0.170 | 0.17 | 0.170 ± 0.090 | 0.47 | 0.020 ± 0.010 | 0.35 |

| 63 | 0.007 ± 0.004 | 0.15 | 0.002 ± 0.001 | 0.32 | 0.002 ± 0.002 | 0.33 |

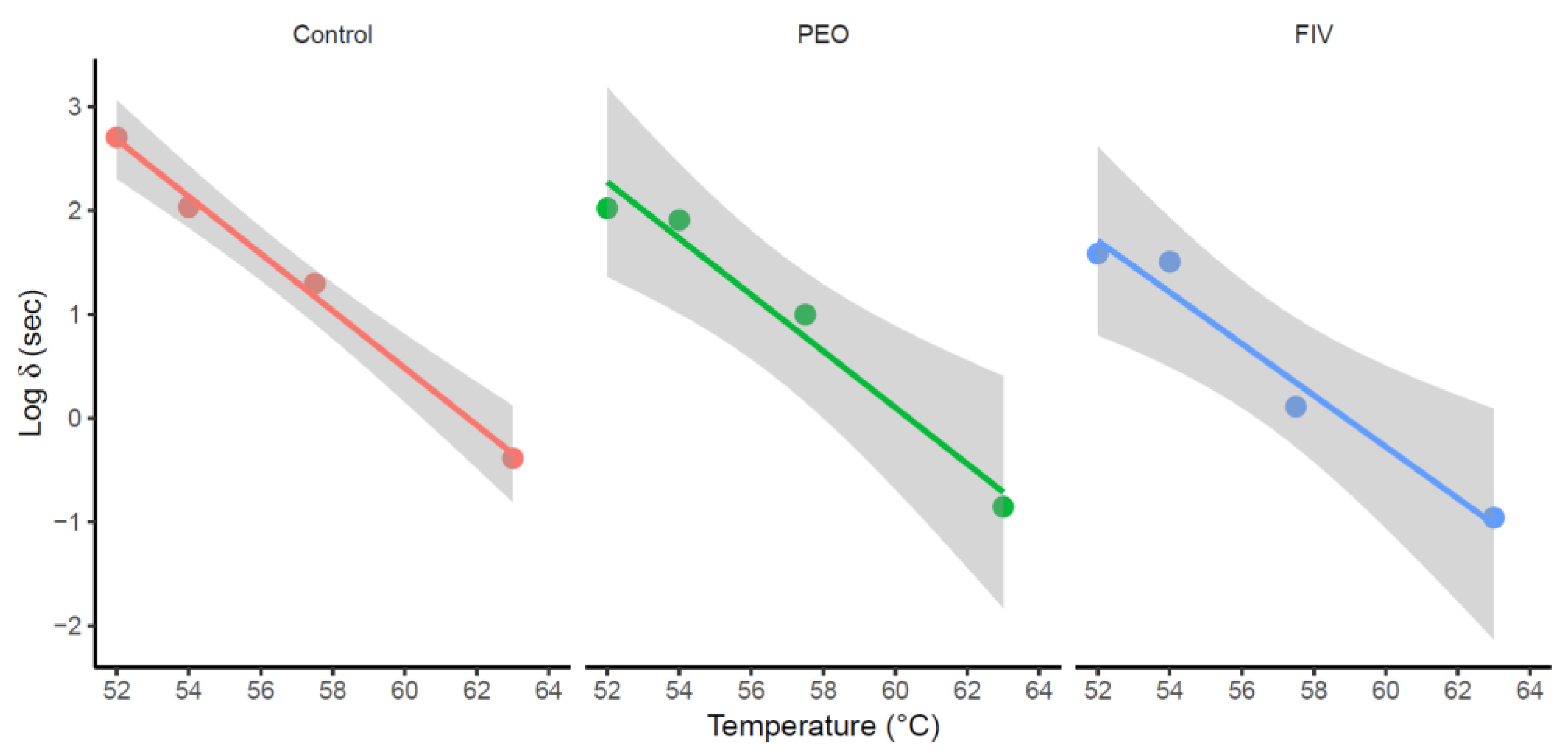

| One-Step | Two-Step | ||||||

| Group | RMSE | RMSEstd | z-value | z-value | RSE | t value | Pr (>|t|) |

| Control | 0.31 | 0.06 | 5.75 ± 0.28 | 3.63 ± 0.19 | 0.12 | 19.29 | 0.003 |

| PEO | 0.43 | 0.08 | 5.20 ± 0.14 | 3.69 ± 0.46 | 0.28 | 8.00 | 0.02 |

| FIV | 0.46 | 0.09 | 5.00 ± 0.13 | 4.03 ± 0.55 | 0.28 | 7.27 | 0.02 |

| Matrix | Treatment | D- or δ-values (min) |

Z Values (°C) |

Reference | ||||||

| D52 | D54 | D55 | D57.5 | D60 | D63 | D65 | ||||

| BHI broth supplemented with glucose and yeast extract | P. longiflora PEO 0.06%: | 1.75 | 1.35 | - | 0.17 | - | 2.00x10-3 | - | 5.20 | Present study |

| P. longiflora FIV 0.06%: | 0.64 | 0.54 | - | 0.02 | - | 2.00x10-3 | - | 5.00 | ||

| Sous-vide salmon | Origanum vulgare EO 1% | - | - | 10.03 | 4.88 | 1.81 | - | - | 5.62 | [40] |

| Sous-vide beef | Salvia officinalis EO 0.6% | - | - | 21.17 | - | - | - | - | - | [71] |

| Ground pork | Cinnamaldehyde 0.5% | - | - | 3.61 | - | 0.63 | - | 0.52 | - | [72] |

| BHI broth | Carvacrol 30 µg/mL | - | - | 8.17 | - | 0.67 | 0.17 | 0.07 | - | [73] |

| 2-Hexenal 65 µg/mL | - | - | 8.03 | - | 0.60 | 0.12 | 0.08 | - | ||

| Citral 50 µg/mL | - | - | 8.42 | - | 0.66 | 0.16 | 0.08 | - | ||

| TSBYE | Thymol | - | - | 0.25 | - | - | - | - | - | [74] |

| Carvacrol | - | - | 0.25 | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Thymol + Carvacrol | - | - | 0.18 | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| PBS | Thymol | - | - | 1.47 | - | - | - | - | - | [75] |

| Carvacrol | - | - | 1.48 | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Thymol + Carvacrol | - | - | 0.38 | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Pineapple juice | Mexican coriander 15 µg/mL | 5.61 | 0.53 | 0.28 | [76] | |||||

| Mexican coriander 60 µg/mL | 5.47 | 0.44 | 0.16 | |||||||

| Beef marinated | Grapefruit seed extract 200 ppm | - | - | 22.17 | 6.11 | 3.69 | - | - | 7.98 | [59] |

| Ground Turkey | Sodiumchloride (1%) and green tea polyphenol extract (1.5%) | - | - | 30.40 | - | 5.50 | - | 0.90 | - | [77] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).